Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

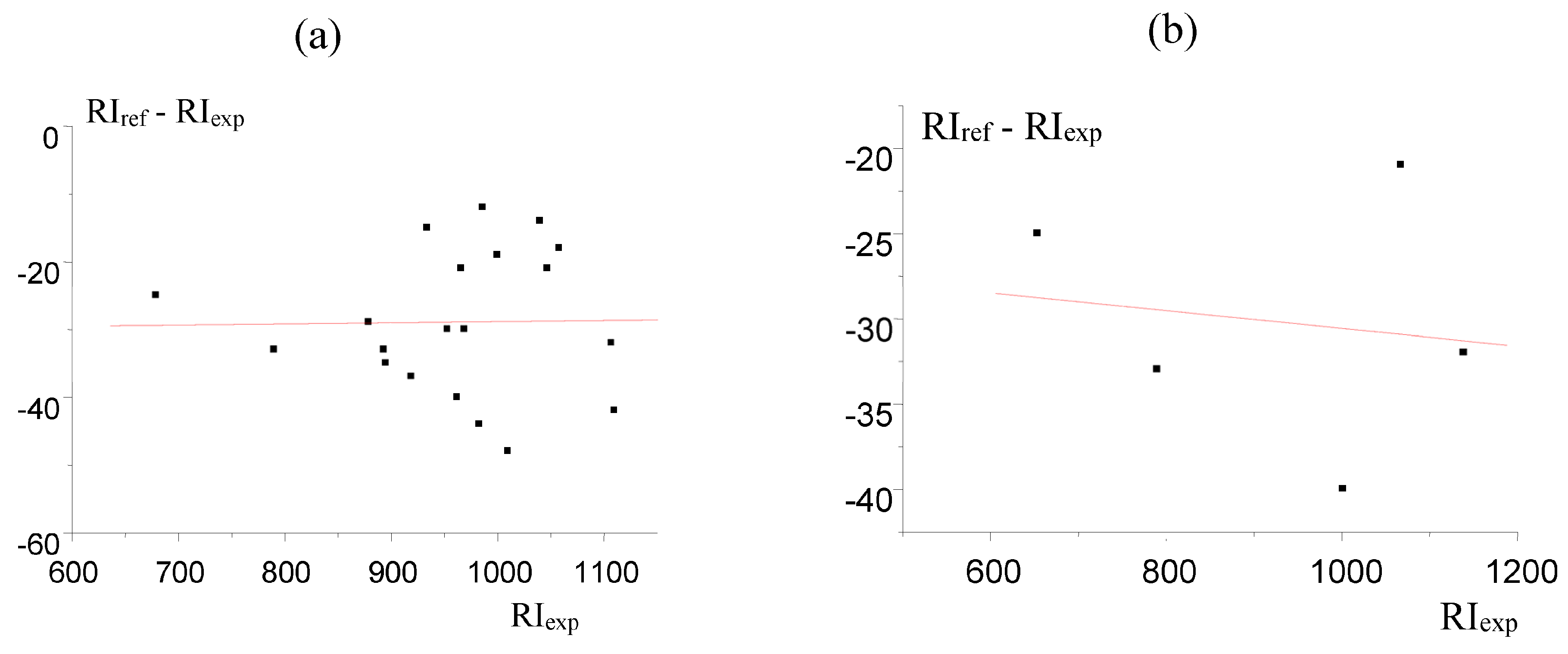

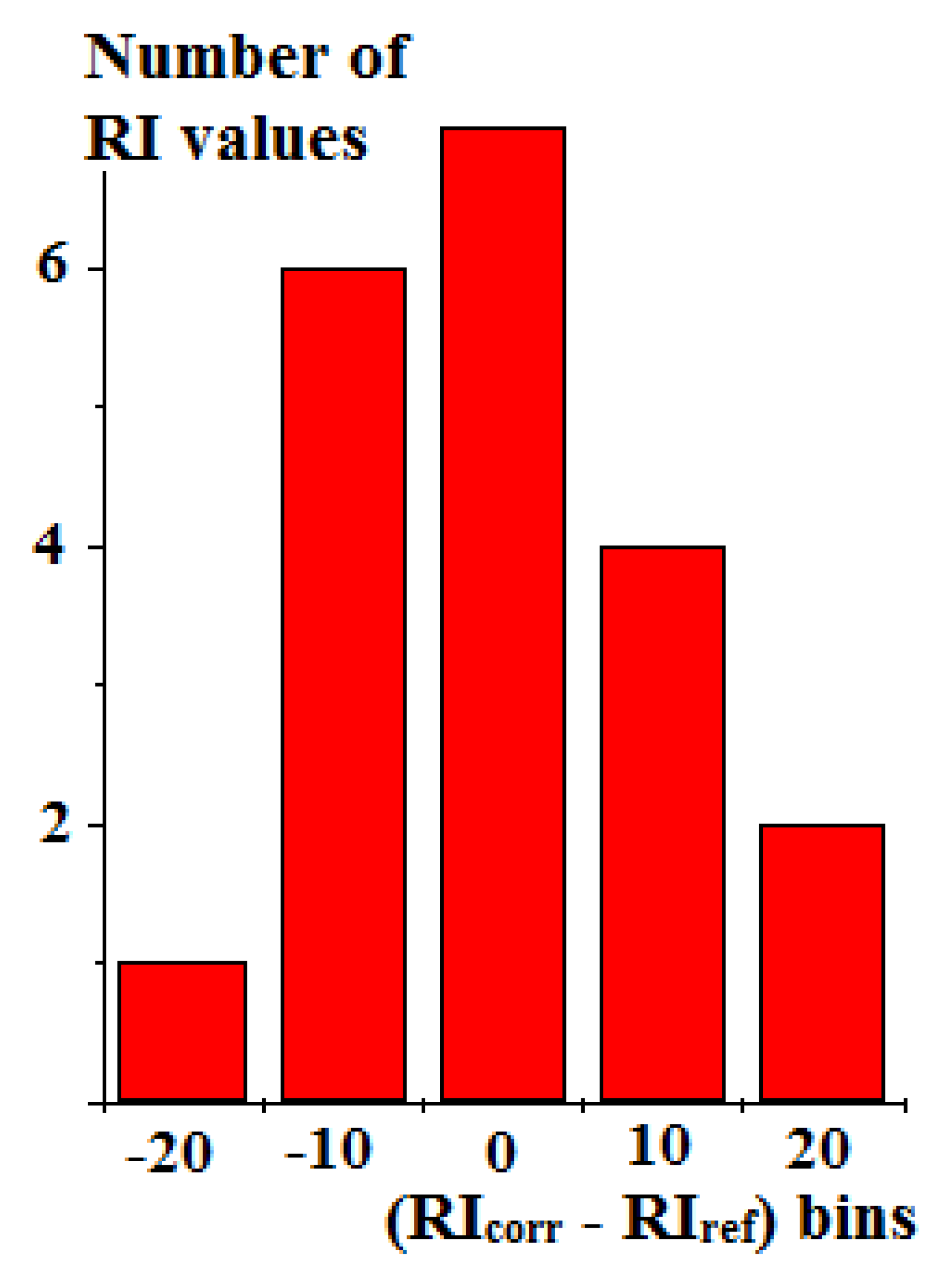

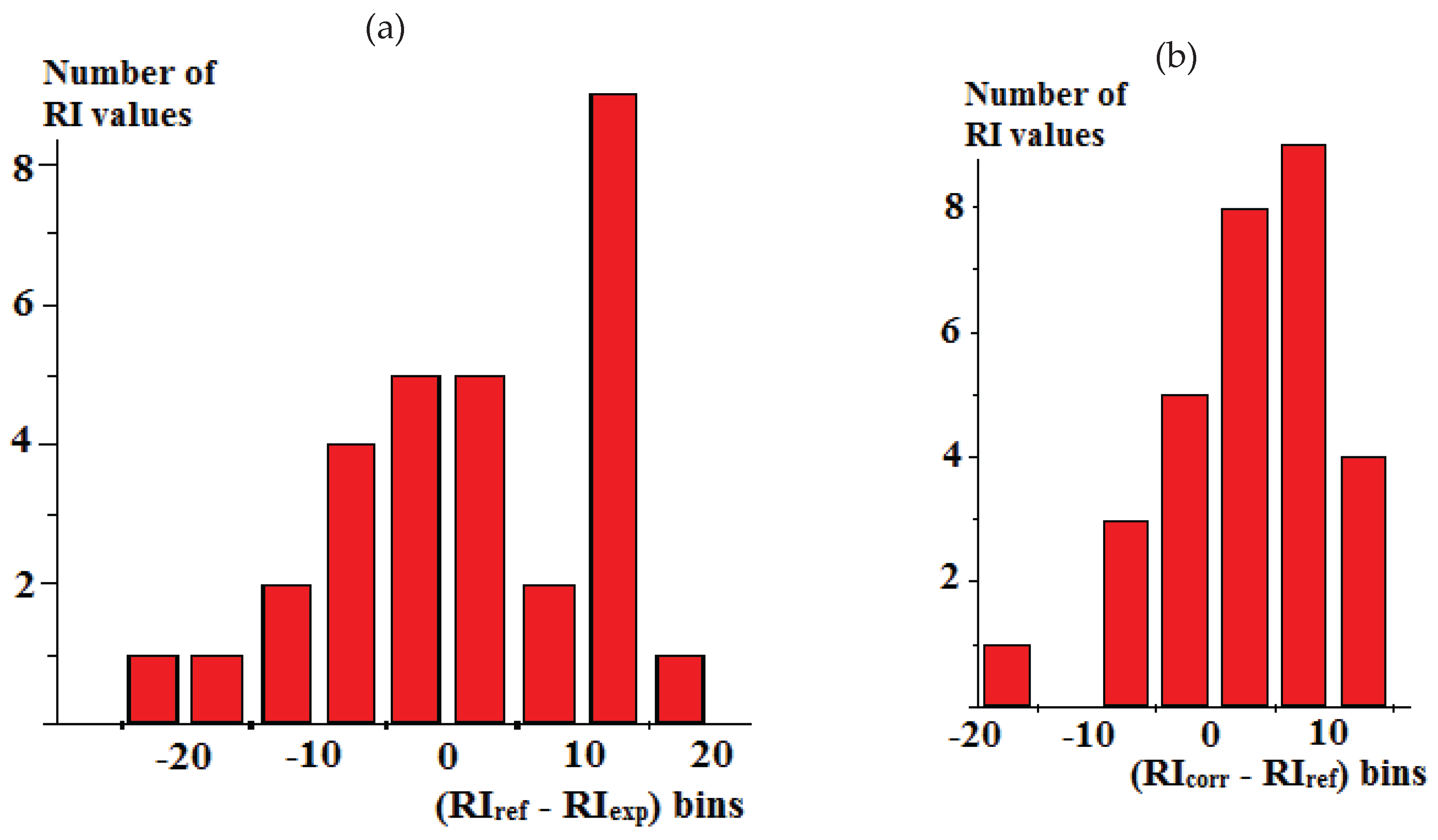

The potential of the new algorithm for comparing experimental and reference values of gas chromatographic retention indices (RI) is discussed. This algorithm is designed to eliminate significant elements of uncertainty typical of numerous contemporary recommendations, primarily the fixed limiting values of permissible deviations, DRI = (RIref – RIexp). The algorithm proposed implies the calculation of deviations DRI for selected most reliably identified constituents of multicomponent mixtures with known reference RI values, followed by calculation of coefficients of regression equations DRI = (RIref – RIexp) = aRIexp + b for total sets of analytes. These equations allow recalculating the experimentally determined RIs into the corrected values RIcorr = RIexp + DRI. Such algorithm makes it possible to use reference RI values for semi-standard nonpolar polydimethylsiloxane phases (with 5% phenyl groups and others) for the comparison with data determined with standard nonpolar polydimethylsiloxanes and vice versa. It is applicable both to statistically processed reference data and to results of single measurements.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The choice of fixed value ΔRIlim = 20 i.u. seems to be illogical because the differences between experimental and reference data can take both larger and smaller values depending on the chemical nature of analytes and types of stationary phases under comparison;

- Condition (2) implies the symmetrical distribution of ΔRI, in other words, the equally probable deviations of experimental and reference data both at ΔRI < 0 and ΔRI > 0, but in the general case it is not obvious.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Optimization of Comparing the Experimental and Reference Values of GC Reten tion Indices

2.2. Application of the Algorithm of Comparing the Experimental and Reference GC Retention Indices to Multicomponent Mixtures

| RI | Compound | Number of RI values for stan dard/semi-standard phases in [2] |

| 1376 [2] | α-Copaene | 377/698 |

| 1377 [21] | Silfiperfol-6-ene | None |

| 1379 [21] | β-Patchoulene | 10/23 |

| 1380 [21] | Daucene | 16/14 |

| 1381 [21] | β-Panansinene | 1/5 |

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusion

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kovats’ Retention Index System. In Encyclopedia of Chro ma tography. Ed. J. Ca zes. 3rd Edn. Taylor & Francis. New York. 2010, 2, 1304-1310.

- The NIST Mass Spectral Library (NIST/EPA/NIH EI MS Library, 2017 Release). Soft ware/Data Ver si on; NIST Standard Reference Database, Number 69, August 2017. Na ti onal Insti tute of Standards and Techno logy, Gaithersburg, MD 20899: http://webbook.nist.gov (Accessed: September 2025).

- Isidorov, V.A.; Zenkevich, I.G. Gas chromatographic – mass spectrometric deter mination of impurities of organic compounds in atmosphere. Khimia Publ. Lenin grad, 1982. (In Russian).

- Sokolov, S.; Karnofsky, J.; Gustafson, P. The Finnigan Library Search Program. Finn. Appl. Rep., 1978, № 2.

- Zenkevich, I.G.; Ukolova, E.S. Dependence of chromatographic retention indices on a ratio of amounts of target and reference compounds // J. Chromatogr. A. 2012, 1265, 133-143. doi: 10.1016/j. chroma.2012.09.076.

- Rospondek, M.J.; Narynowski, L.; Chachaj, A.; Gora, M. Novel aryl polycyclic aro matic hydrocarbons: phenylphenanthrene and phenylanthracene identification, oc currence and distribution in sedimentary rocks // Org. Geochem. 2009, 40, 986-1004. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2009.06.001.

- Costa, R.; Pizzimenti, F.; Marotta, F.; Dugo, P.; Santi, L.; Mondelo, L. Volatiles from steam-distilled leaves of some plant species from Madagascar and New Zealand and evaluation of their biological activity // Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5(11), 1803-1808.

- Wang, X.-L.; Yu, W.-J.; Zhou, Q.; Han, R.-F.; Huang, D.F; Metabolic response of pak choi leaves to amino acid nitrogen // J. Integrative Agricult. 2014, 13(4), 778-788.

- Bodner, M.; Vagalinski, B.; Makarov, S.E.; Antic, D.Z.; Vujisic, L.V.; Leis, H.-J.; Ras potnig, G. “Quinone millipedes” reconsidered: evidence for a mosaic-like taxono mic distribution of phenol-based secretion across the julidae // J. Chem. Ecol. 2016, 42, 249-258. doi: 10.1007/s10886-016-0680-4.

- Jung, E.P.; Alves, R.C.; Rocha, W.F. de C.; Monteiro, S. da S.; Ribeiro, L. de O.; Mo reira, R.F.A. Chemical profile of the volatile fraction of Bauhinia forficata leaves: an evaluation of commercial and in natura samples // Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, № e34122.

- Trovato, E.; Micalizzi, G.; Dugo, P.; Utczas, M.; Mondello, L. Use of linear reten tion indices in GC-MS. In: Baser K.H.C., Buchbauer G. Handbook of essential oils. Science, technology, and applications. 2015. Boca Raton (CA.). CRC Press, 2015.

- Weissburg, J.R.; Johanningsmeier, S.D.; Dean, L.L. Volatile compounds profiles of raw and roasted peanut seeds of the runner and Virginia market-types // J. Food Res. 2023, 12(3), 47-68. doi: 10.5539/jfr.v12n3p47.

- Wesolowska, A; Jadczak, D.; Zyburtowich, K. Influence of distillation time and dis tillation apparatus on the chemical composition and quality of Lavandula angu s tifolia Mill, essential oil // Polish J. Chem. Technol. 2023, 25(4), 36-43.

- Albarico, G.; Unbanova, K.; Houdkova, M.; Bande, M.; Tulin, E.; Kokoskova, T.; Ko ko ska, L. Evaluation of chemical composition and anti-staphylococcal activity of essential oils from leaves of two indigenous plant species, Litsea leytensis and Pi per philippinum // Plants. 2024, 13, № 3555. doi: 10.3390/plants13243555.

- Castillo, L.N.; Calva, J.; Ramirez, J.; Vidari, G.; Arnijos, C. Chemical analysis of the essential oils from three populations of Lippia dulcis Trevir. grown at different lo cations in southern Ecuador // Plants. 2024, 13, № 253. doi: 10.3390/plants13020253.

- Smith, D.H.; Achenbach, M.; Yeager, W.I.; Andersson, P.J.; Fitch, W.H.; Rind fleisch, T.C. // Quantitative comparison of combined gas chromatographic/mass spectro metric profiles of complex mixtures // Anal. Chem. 1977, 49(11), 1623-1632. doi: 10.1021/ac50019a041.

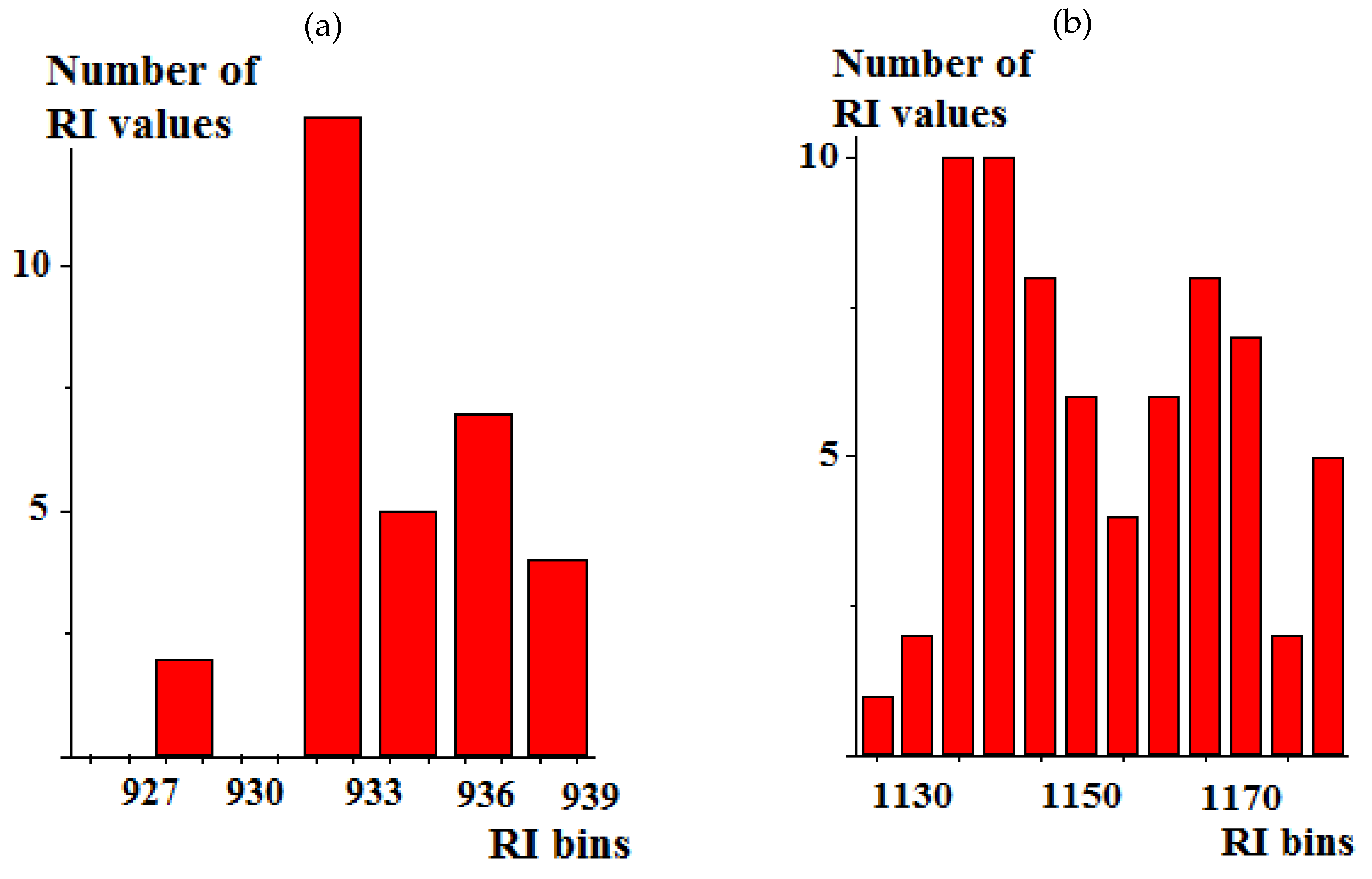

- Zenkevich, I.G.; Babushok, V.I.; Linstrom, P.J.; White, V E.; Stein, S.E. Applica tion of histograms in evaluation of large collections of gas chromatographic indi ces // J. Chromatogr. A. 2009, 1216, 6651-6661. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.07.065.

- Bizzo, H.R.; Brilhante, N.S.; Nolvachai, Y.; Marriott, P.J. Use and abuse of reten tion indices in gas chromatography // J. Chromatogr. A. 2023, 1708, № 464376. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2023.464376.

- Matheson, A. Identifying and rectifying the misuse of retention indices in GC // LC-GC International. 2024, 20(12), 2-8.

- Zenkevich, I.G. Information maintenance of gas chromatographic identification of organic compounds in ecoanalytical investigations // J. Anal. Chem. 1996, 51(11), 1140-1148. (In Russian).

- Adams, R. Identification of essential oils components by GC/MS. Version 4. Carol Stream, IL: Allured Publ. Corp., 2007. 804 p.

- Babushok, V.I.; Linstrom, P.J.; Zenkevich, I.G. Retention Indices for Frequently Re ported Compounds of Plant Essential Oils // J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 2011, 40(4), № 043101. doi: 10.1063/1.3653552.

- Brown, I. The composition of a Lurgi brown coal tar. III. The neutral oil fraction boi ling from 30 to 130°C and 130–172°C // Austr. J. Appl. Chem. 1960, 11(4), 403-433.

- Linnik, Yu.V. Least squares method and fundamentals of proces sing the obser va tions. Moscow, Physical-Mathematical Literature Press, 1958. 334 p. (In Russi an).

- Engewald, W.; Knobloch, T.; Haufe, G.; Muller, M.; Pohris, V. A novel method for terpene pattern determination of essential oils by selectivity tuning in GC // Frese nius’ J. Anal. Chem. 1991, 341(10), 641-643. doi: 10.1007/BF00322279.

- Benadi, T.; Lemhadri, A.; Harboul, K.; Chtibi, H.; Khabbach, A.; Jadouali, S.M.; Qu e sa da-Romero, L.; Louahliq, S.; Hammani, K.; Ghaleb, A.; Lee, L.-H.; Bouyahya, A.; Rusu, M.E.; Akhazzane, M. Chemical profiling and biological pro perties of es sential oils of Lavandula stolchas L., collected from three Moroccan sites: in vitro and in silico investigations // Plants. 2023, 12(6), № 1413. doi: 10.3390/plants120614-13.

- Obistioiu, D.; Cristina, R.T.; Schmerold, I.; Chizzola, R.; Stolze, K.; Nichita, I.; Chiu r ciu, V. Chemical characterization by GC-MS and in vitro activity against Candida albicans of volatile fractions prepared from Artemisia dracunculus, Artemisia ab ro tanum, Artemisia absinthium and Artemisia vulgaris // Chem. Cent. J., 2014, 8(6), ID 24475951. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-8-6.

- Zenkevich, I.G. Non-traditional cri teria for the identification of organic compo unds by chromatography and chroma to graphy – mass spectrometry // J. Anal. Chem. 1998, 53(8), 725-731. (In Russian).

| Compound |

RIexp [23] |

RIref [2] |

Δref-exp |

Complete set of reference data |

Reduced set of reference data |

||

| RIcorr | Δcorr-ref | RIcorr* | Δcorr-ref | ||||

| Benzene | 679 | 654± 7 | -25 | 650 | -4 | 650 | -4 |

| Toluene | 790 | 757± 6 | -33 | 761 | +4 | 760 | +3 |

| Ethylbenzene | 879 | 850 ± 6 | -29 | 850 | 0 | 849 | -1 |

| m-Xylene | 893 | 860 ± 6 | -35 | 866 | +6 | 865 | +5 |

| p-Xylene | 893 | 860 ± 6 | -33 | 864 | +4 | 863 | +3 |

| o-Xylene | 919 | 881 ± 6 | -37 | 890 | +9 | 889 | +8 |

| Isopropylbenzene | 934 | 919 ± 7 | -15 | 905 | -14 | 904 | -15 |

| Propylbenzene | 966 | 945 ± 5 | -21 | 937 | -8 | 936 | -9 |

| 1-Methyl-4-ethylbenzene | 983 | 953 ± 5 | -30 | 954 | +1 | 953 | 0 |

| tert-Butylbenzene | 998 | 986 ± 7 | -12 | 969 | -17 | 968 | -18 |

| 1-Methyl-2-ethylbenzene | 999 | 969 ± 5 | -30 | 970 | +1 | 969 | 0 |

| 1,3,5-Trimethylbenzene | 1002 | 962± 6 | -40 | 974 | +12 | 972 | +10 |

| sec-Butylbenzene | 1019 | 1000 ± 5 | -19 | 991 | -9 | 989 | -11 |

| 1,2,4-Trimethylbenzene | 1027 | 983 ± 5 | -44 | 999 | +16 | 997 | +14 |

| 1,3-Diethylbenzene | 1054 | 1040 ± 5 | -14 | 1026 | -14 | 1023 | -17 |

| 1,2,3-Trimethylbenzene | 1058 | 1010 ± 6 | -48 | 1030 | +20 | 1027 | +17 |

| Butylbenzene | 1068 | 1047± 6 | -21 | 1040 | -7 | 1037 | -10 |

| 1-Methyl-2-propylbenzene | 1076 | 1058 ± 5 | -18 | 1048 | -10 | 1045 | -13 |

| 1,2,4,5-Tetramethylbenzene | 1139 | 1107± 5 | -32 | 1111 | +4 | 1108 | +1 |

| 1,2,3,5-Tetramethylbenzene | 1152 | 1110 ± 6 | -42 | 1124 | +14 | 1121 | +11 |

| Average standard deviation of reference RI values, sRI | 5.8 | ||||||

| Average difference Δref-exp: | -29 ± 10 | ||||||

| Average difference Δcorr-ref: | 9 ± 6 (0 ± 11)** |

8 ± 6* (-1 ± 10)** |

|||||

| Compound | RIexp | RIref [2] | Δref-exp | Complete set of reference data | Reduced set of reference data | ||||

| RIcorr | Δcorr-ref | RIcorr* | Δcorr-ref* | ||||||

| α-Pinene** | 950 | 933± 4 | -17 | 936 | +3 | 930 | -3 | ||

| Camphene | 969 | 946 ± 5 | -23 | 956 | +10 | 950 | +4 | ||

| Myrcene | 985 | 983 ± 3 | -2 | 970 | -15 | 967 | -18 | ||

| 3-Carene | 1022 | 1006 ± 5 | -16 | 1010 | +4 | 1005 | -1 | ||

| Limonene | 1038 | 1017± 3 | -21 | 1026 | +9 | 1022 | +5 | ||

| Linalool | 1089 | 1086± 3 | -3 | 1077 | -9 | 1076 | -10 | ||

| Isofenchol | 1114 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Fenchone | 1120 | 1105 ± 6 | -15 | 1109 | +4 | 1108 | +3 | ||

| Citronellal | 1138 | 1134 ± 4 | -4 | 1127 | -7 | 1127 | -7 | ||

| (Z)-Verbenol | 1144 | 1133 ± 5 | -11 | 1133 | 0 | 1148 | +15 | ||

| Camphor | 1146 | 1123± 6 | -23 | 1135 | +12 | 1136 | +13* | ||

| (Z)-Pinocarveol*** | 1146 | 1135 ± 7 | -11 | 1135 | 0 | 1136 | +1 | ||

| 1126 ± 6 | -20 | 1135 | +9 | 1136 | +10 | ||||

| (E)-Verbenol | 1147 | 1133 ± 5 | -14 | 1136 | +3 | 1137 | +4 | ||

| Isopulegol | 1148 | 1144 ± 5 | -4 | 1137 | -7 | 1138 | -6 | ||

| (Z)-Pinocamphone | 1160 | 1140 ± 5 | -20 | 1149 | +9 | 1150 | +10 | ||

| Borneol | 1171 | 1151 ± 18 | -20 | 1161 | +10 | 1162 | +11 | ||

| Menthol*** | 1174 | 1157 ± 2 | -17 | 1164 | +7 | 1165 | +8 | ||

| 1165 ± 6 | -9 | 1164 | -1 | 1165 | 0 | ||||

| Terpinen-4-ol | 1178 | 1164 ± 5 | -14 | 1168 | +4 | 1169 | +5 | ||

| Carenol | 1188 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| α-Terpineol | 1189 | 1175 ± 5 | -14 | 1179 | +4 | 1181 | +6 | ||

| Neocarveol | 1189 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Myrtenol | 1195 | 1181 ± 5 | -14 | 1185 | +4 | 1187 | +6 | ||

| Verbenone | 1202 | 1184 ± 7 | -18 | 1092 | +8 | 1194 | +10 | ||

| Neral | 1223 | 1218± 5 | -5 | 1213 | -5 | 1216 | -2 | ||

| Carvone | 1230 | 1218 ± 6 | -12 | 1220 | +2 | 1227 | +9 | ||

| Geraniol | 1238 | 1237 ± 4 | -1 | 1229 | -8 | 1232 | -5 | ||

| Linalyl acetate | 1242 | 1241 ± 2 | -1 | 1233 | -8 | 1236 | -5 | ||

| Geranial | 1250 | 1249± 8 | -1 | 1241 | -8 | 1245 | -4 | ||

| Safrol | 1275 | 1269 ± 7 | -6 | 1266 | -3 | 1271 | +2 | ||

| Bornyl acetate | 1280 | 1270 ± 5 | -10 | 1271 | +1 | 1276 | +6 | ||

| (Z)-Pinocarvyl acetate | 1301 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Isosafrol | 1357 | 1327 ± 31 | -30 | 1349 | +224* | 1357 | +304* | ||

| 1358 ± 65* | +1 | 1349 | -9 | 1357 | -1 | ||||

| Average standard deviation of reference RI values, sRI | 6.3 | ||||||||

| Average difference Δref-exp: | 13.2 | ||||||||

| Average difference Δcorr-ref: | 7 ± 5 | 6 ± 4 | |||||||

| Compound | RIexp | RIref [21] | Δref-exp | Complete set of reference data | Reduced set of reference data | ||

| RIcorr | Δcorr-ref | RIcorr* | Δcorr-ref* | ||||

| α-Pinene** | 950 | 932 | -18 | 933 | +1 | 933 | +1 |

| Camphene | 969 | 946 | -23 | 953 | +7 | 954 | +8 |

| Myrcene | 985 | 988 | +3 | 970 | -18*** | 972 | -16*** |

| 3-Carene | 1022 | 1008 | -14 | 1010 | +2 | 1012 | +4 |

| Limonene | 1038 | 1024 | -14 | 1028 | +4 | 1029 | +5 |

| Linalool | 1089 | 1095 | +6 | 1083 | -12 | 1085 | -10 |

| Isofenchol | 1114 | 1114 | 0 | 1110 | -4 | 1112 | -2 |

| Fenchone | 1120 | 1118 | -2 | 1116 | -2 | 1119 | +1 |

| Citronellal | 1138 | 1148 | +10 | 1136 | -12 | 1139 | -9 |

| (Z)-Verbenol | 1144 | 1137 | -7 | 1142 | +5 | 1145 | +8 |

| Camphor | 1146 | 1141 | -5 | 1144 | +3 | 1147 | +6 |

| (Z)-Pinocarveol | 1146 | 1135 | -11 | 1144 | +9 | 1147 | +12 |

| (E)-Verbenol | 1147 | 1140 | -7 | 1145 | +5 | 1148 | +8 |

| Isopulegol | 1148 | 1145 | -3 | 1146 | +1 | 1149 | +4 |

| (Z)-Pinocamphone | 1160 | 1172 | +12 | 1159 | -13 | 1163 | -9 |

| Borneol | 1171 | 1165 | -6 | 1171 | +6 | 1175 | +10 |

| Menthol | 1174 | 1167 | -7 | 1174 | +7 | 1178 | +11 |

| Terpinen-4-ol | 1178 | 1174 | -4 | 1179 | +5 | 1182 | +8 |

| Carenol | 1188 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| α-Terpineol | 1189 | 1189 | 0 | 1191 | +2 | 1194 | +5 |

| Neocarveol | 1189 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Myrtenol | 1195 | 1194 | -1 | 1197 | +3 | 1201 | +6 |

| Verbenone | 1202 | 1204 | +2 | 1205 | +1 | 1208 | +4 |

| Neral | 1223 | 1235 | +12 | 1227 | -8 | 1231 | -4 |

| Carvone | 1230 | 1239 | +9 | 1235 | -4 | 1239 | 0 |

| Geraniol | 1238 | 1249 | +11 | 1244 | -5 | 1248 | -1 |

| Linalyl acetate | 1242 | 1254 | +12 | 1248 | -6 | 1252 | -2 |

| Geranial | 1250 | 1264 | +14 | 1257 | -7 | 1261 | -3 |

| Safrol | 1275 | 1285 | +10 | 1284 | -1 | 1288 | +3 |

| Bornyl acetate | 1280 | 1284 | +4 | 1289 | +5 | 1293 | +11 |

| (Z)-Pinocarvyl acetate | 1301 | 1311 | +10 | 1312 | +1 | 1316 | +5 |

| Isosafrol | 1357 | 1373 | +16 | 1372 | -1 | 1377 | +4 |

| Average difference Δref-exp: | 8.4 | ||||||

| Average difference Δcorr-ref: | 5 ± 4 | 6 ± 4 | |||||

| RIexp | RIref [21] | ΔRIref-exp | RIcorr | ΔRIcorr | |

| Camphene | 949 | 946 | -3 | 948 | +2 |

| Myrcene | 993 | 988 | -5 | 992 | -1 |

| (Е)-Ocimene | 1038 | 1044 | +6 | 1037 | -1 |

| γ-Terpinene | 1049 | 1054 | +5 | 1048 | -1 |

| Linalool | 1100 | 1095 | -5 | 1098 | +3 |

| Alloocimene | 1136 | 1128 | -8 | 1134 | -2 |

| Linalyl acetate | 1256 | 1254 | -2 | 1253 | -3 |

| С15Н24* | 1365 | - | - | 1361 | - |

| С15Н24* | 1384 | - | - | 1380 | - |

| Aromadendrene | 1443 | 1439 | -4 | 1439 | -4 |

| Average difference Δref-exp: | 4.8 | ||||

| Average difference Δcorr-ref: | 2 ± 1 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).