1. Introduction

The idealisation of a way of life aligned with personal values, territorial identity and well-being goals has driven the search for new ways of living and working in rural areas, leading to the emergence of an increasingly representative phenomenon in low-density territories: Lifestyle Entrepreneurs [

1,

2]. LSE act as "economic engines" that contribute to the multiplier effect, stimulating the local economy, promoting prosperity [

3] and, consequently, reducing regional asymmetries.

Despite growing academic interest in LSE, there is still a long way to go in analysing those that develop in low-density territories, territories characterised by structural weaknesses such as depopulation, poor accessibility, demographic ageing, lack of infrastructure and little economic diversification [

4]. This study seeks to analyse simultaneously the motivations, business models, community involvement and challenges of entrepreneurs, investigating how EEVs contribute to territorial revitalisation through tourism, in the specific context of the Planalto Mirandês.

Despite the growing body of literature on lifestyle entrepreneurship, existing studies have primarily focused on motivations and personal fulfilment [

5,

6], often overlooking how these entrepreneurs are embedded in their communities and contribute to local resilience. The intersection between individual lifestyle choices, community attachment, and territorial development remains underexplored, particularly in the context of low-density rural areas where social and institutional infrastructures are fragile [

1,

7]. Moreover, while the role of rural tourism in promoting sustainable development has been widely recognised, little attention has been paid to how lifestyle entrepreneurs operationalise community engagement and transform local knowledge into innovative and regenerative practices.

Accordingly, this study aims to understand how lifestyle entrepreneurs in low-density rural territories integrate personal values, community attachment, and place identity into their entrepreneurial practices. Specifically, it seeks to explore the motivations that drive the creation of lifestyle-based ventures, the forms and intensities of community involvement that emerge, and the ways in which these entrepreneurs contribute to local sustainability and territorial regeneration. To address these aims, the following research questions are posed: (1) What motivates lifestyle entrepreneurs to establish tourism ventures in low-density territories? (2) How do they engage with and contribute to their local communities? (3) In what ways do their business models reflect the interaction between lifestyle aspirations, innovation, and territorial embeddedness?

A qualitative, multiple case study approach was adopted to capture the complexity and contextual nature of lifestyle entrepreneurship in rural tourism. This methodological choice allows for an in-depth exploration of entrepreneurs’ narratives, practices, and relationships with the community, providing rich insights into processes that are often overlooked in quantitative research [

8]. By analysing three distinct cases from the Planalto Mirandês, this study offers both theoretical and practical contributions. Theoretically, it extends the literature on lifestyle entrepreneurship and community-based tourism by articulating how personal purpose and place attachment evolve into socially embedded entrepreneurial models. Practically, it highlights the need for tailored policy frameworks and support mechanisms that recognise lifestyle entrepreneurs as key actors in the sustainable revitalisation of low-density territories.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Concept of Lifestyle Entrepreneur

Lifestyle entrepreneurs (LEE) have been gaining prominence in the entrepreneurship literature as they represent an alternative approach to traditional entrepreneurs. While conventional entrepreneurs prioritise profit maximisation and business expansion [

6,

9,

10], for LSE, starting a business is not an end in itself, but as a means to achieve personal fulfilment, a sense of purpose and community contribution. EEV value the integration of personal and professional life, individual well-being and connection to the territory they choose to live in [

5,

11].

As [

9] points out, EEV are those who incorporate their dreams and passions into a business and create businesses with meaning and authenticity. [

11] complement this view by describing tourism EEV as individuals, residents or migrants, who start a business in the tourism sector and focus on preserving the local lifestyle, culture and environment. This idea is further reinforced by studies that highlight the tendency of EEV to integrate community traditions into their practices, distinguishing themselves from models focused exclusively on economic growth [

5,

6].

[

6] propose a typology that differentiates EEV according to their dominant orientation: Expression-Oriented Lifestyle Entrepreneurs (EEVE), Activity-Oriented Lifestyle Entrepreneurs (EEVA) and Location-Oriented Lifestyle Entrepreneurs (EEVL). This classification summarises differences in terms of motivations, behaviours and outcomes, as shown in

Table 1. Analysis of the interviews conducted empirically confirms this typological diversity. This classification allows for a better understanding of the diversity of EEV, but also highlights the transversality of certain common traits, such as a collaborative attitude, a focus on the community and an aversion to financial risk [

1,

5].

Although understanding the types of EEV allows us to classify the diversity of existing profiles, it does not in itself explain what leads these individuals to create and maintain a business in low-density areas. To do so, it is important to analyse the motivations that guide their choices.

2.2. Motivations of Lifestyle Entrepreneurs

As mentioned by [

5,

6] and [

12] EEV in the tourism sector are often driven by a strong connection to the place where they live and work. They identify the places that attract them as an opportunity to achieve their social goals while wishing to contribute to the revitalisation of the community to which they are linked, either through the promotion of local traditions or, through the incorporation of regional products into their activities. Take the case of Beatriz from Casa da Montanha, who created an emotional connection with the territory: "...I was truly enchanted and fell in love with nature, the landscape, the people, everything." Or take the case of Júlia from Associação Planalto, who voluntarily moved to the countryside to work on a meaningful project: "... I always had a great desire to live in the countryside. So everything here was appealing to me, working with animals, working with people, living in a very rural area, in the countryside, close to animals in nature." And Henrique from Mergulho Serrano, who returned to his roots, motivated by a lifestyle and personal identity, "I'm from here and I know the area well, (...). Hunger met desire. I took action and suddenly I had a diving school...".

In addition to their connection to the place, another factor that motivates EEV is quality of life, autonomy and the possibility of living according to their convictions and passions [

5]. They seek to maintain a balance between work and personal [

6]. Family ties and cultural considerations play a significant role in deciding where to live, with factors such as family expectations, marriage, and children's well-being influencing the choice [

13]. These EEV seek intangible rewards such as pride, personal growth, a sense of achievement and empowerment [

5].

Several authors mention that many EEV are motivated by the opportunity to revitalise rural communities, enhance endogenous resources and preserve cultural and environmental heritage [

11,

14], sharing motivations such as a commitment to ecological principles and sustainability. [

5] and [

14] highlight the role of EEV in integrating responsible tourism practices that value both environmental preservation and local knowledge passed down through generations. As Beatriz from Casa da Montanha points out, "...this has a lot to do with the people here." There was a concern to maintain the original architecture, traditional construction and local materials in the houses they operate. In the programmes of the Planalto Association, local knowledge is given its due value. "The blacksmith used to say, 'Never book me 20-minute visits, but at least an hour, so that I can respond to people...' and they have adopted the slogan 'Since 2001, caring for the well-being of donkeys and people'."

[

15] Push and Pull model, developed to understand the motivations of tourists, can be applied to EEV to explain their motivations and the interactions between internal and external factors. We have push factors, related to the emotional aspects of individuals that "push" the entrepreneur in a search for the devilry to leave their current situation, linked to individual desires for change and fulfilment, and pull factors, which are external factors, consisting of characteristics of destinations that "pull" the entrepreneur, related to the appeal of certain territories and lifestyles. These trends are visible in the data collected in the interviews. Beatriz from Casa da Montanha refers to her "enchantment with nature, the landscape and the people" as the driving force behind her decision to settle in the Planalto Mirandês, revealing the strength of the pull factors. Júlia from Associação Planalto confirms an intrinsic motivation linked to the social and ecological purpose of the project: "I have always had a great desire to live in the countryside, close to animals and nature." Henrique from Mergulho Serrano highlights the return to his roots and his passion for diving as determining factors, a clear illustration of push factors associated with personal identity and specific activities.

Thus, we can say that lifestyle entrepreneurship in the tourism sector aims at a practice that goes beyond profit and involves a commitment to the territory, culture, and sustainability in its initiatives. And if motivation is the starting point for entrepreneurial action, business models translate how these motivations are operationalised in practice, i.e., they reveal how EEV transform their values and goals into concrete strategies.

2.3. Business Models of Lifestyle Entrepreneurs

The business model of EEVs in rural tourism is distinguished by articulating personal values with the use of local resources, creating authentic and sustainable proposals. However, the literature is not unanimous in how it interprets their relationship with innovation. For some authors, EEV show a low propensity for innovation, given their predominance of work-life balance orientation and reduced ambition for growth [

6]. In contrast, others argue that, especially in rural areas, innovation arises as a necessity for survival and differentiation, leading EEV to develop creative solutions to maintain the economic and social viability of their businesses [

5]. This suggests that the relationship between lifestyle entrepreneurship and innovation is not linear, but deeply dependent on the territorial context in which it occurs.

Local knowledge, community involvement and entrepreneurial passion are the main key factors in the EEV business model and the drivers of innovation and performance in their projects [

5,

6,

16]. The impact of this specific form of entrepreneurship goes far beyond economic figures, and although the total economic impact in terms of job and income generation may be modest, there are contributions to local economic and social dynamics that can help keep rural communities alive [

5]. The Planalto Association employs 14 people on fixed-term contracts and 4 volunteers, which is a large number for a village in the interior, and is active on multiple social, cultural and environmental fronts.

In this context, the literature has highlighted the importance of the relationship with the territory, which is understood as an identity and emotional bond with the space in which entrepreneurs decide to live and work [

5,

11]. This relationship translates into knowledge of the territory, which includes everything from natural resources to cultural practices and local opportunities.

[

12] identify that there is a sequence in sustainable business models, from EEV: they begin with the acquisition of local knowledge, move on to the assimilation of this knowledge into their practices and finally translate it into innovation. However, this capacity for innovation depends on the competence of these entrepreneurs in seizing opportunities and their ability to translate them into innovative and meaningful solutions for the market. According to [

1], the degree of integration into the community and the degree of local knowledge provide a basis for the creation of new products and new tourist experiences based on local uniqueness. Although familiarity with the location contributes to innovation, this element is leveraged if there is a high degree of relational capital. It is not enough to access local knowledge and develop a network of contacts in the community and with other stakeholders. By benefiting from this access, entrepreneurs need to deepen their knowledge of local histories, legends, traditions, physical and environmental characteristics, and need to be able to integrate this knowledge into their products and experiences in a meaningful and market-oriented way. They must be able to translate this knowledge into innovative solutions that strengthen the rural context in which they operate and promote a change in tourists' attitudes towards the community and the environment [

16]. By targeting social objectives, local tourism enterprises have the potential to generate economic and social benefits for the community and the destination, and for this reason, migration policies that foster entrepreneurship in rural areas should be encouraged [

5,

13]. The interviewees managed in different ways to combine community involvement with innovation and, in a way, contribute to the territory. Mergulho Serrano, demonstrates how individual passion can be the basis for an innovative model by bringing the first certified diving school to the region. Henrique Silva not only diversified the tourist offer but also opened up new possibilities for interaction between tourists and residents. Casa da Montanha, on the other hand, structures its model around the authenticity of rural accommodation, with a strong emphasis on architectural heritage and the use of local materials, which highlights the incorporation of local knowledge as a central resource. The Planalto Association combines animal protection and community development activities with sustainable tourism products (visits, sponsorship campaigns, cultural events), demonstrating the ability to transform social causes into innovative tourism offerings.

We can identify that the business models of EEV are characterised by three essential points: symbiosis between entrepreneur and community, which guarantees social legitimacy and access to local resources; the centrality of endogenous knowledge, which serves as the basis for differentiation and authenticity; and entrepreneurial passion, which translates into innovation and the creation of sustainable value. These three elements make EEV agents of territorial regeneration, even when operating on a small scale, in a specific context of rural tourism. It is therefore important to understand how tourism in low-density territories has been conceptualised and what the implications are for EEV.

2.4. Rural Tourism

From the tourists' point of view, rural tourism is expected to provide integration into an idealised environment, quite different from the urban one, i.e., it allows an escape from urban stress factors such as pollution, noise and congested living conditions, the so-called rural idyll [

5,

7]. It includes opportunities to enjoy the countryside and its nature, appreciation of culture and traditions, and close social interaction, characterised by genuine hospitality, also reflected in personalised service [

5,

17].

However, the literature also identifies some divergences: while some authors emphasise rural tourism as an authentic refuge, others warn of the risk of rural tourism being transformed into a stereotypical product, where authenticity can become a commercialised resource, losing part of its intrinsic value [

18,

19]. This contradiction suggests that rural tourism can simultaneously preserve and threaten local identity, depending on how it is designed and managed. In this context, [

18] identified that local ecological attributes cannot be defined solely by t s landscapes, human activities, cultural heritage and social interactions also shape landscapes. This comprehensive perspective facilitates a more multifaceted assessment of rural tourism and identifies the need for a more holistic approach in government initiatives and the need to integrate the local community into decision-making processes. Only in this way is it possible to have models that balance ecological conservation, cultural preservation and sustainable development goals [

18,

19].

Rural tourism cannot be seen as a product, but rather as an ecosystem of relationships, where the territory is a platform for creating economic, social and symbolic value [

20,

21]. The articulation between local knowledge, community involvement and tailored policies creates the necessary conditions to transform the rural idyll into sustainable development. This inevitably implies the participation of local communities, which emerges as a critical dimension to ensure the sustainability of EEV initiatives [

5].

2.5. Community Involvement

The demand for authenticity and local experiences has gained market share in the tourism sector. As a result of this change, destination operators have begun to adjust their tourism products to explore and develop more closed and private areas of life, where community involvement is essential. Only with community involvement in decision-making processes, ensuring that residents participate not only in the implementation but also in the enjoyment of the benefits [

22,

23], is it possible to promote sustainable development and social resilience through tourism [

19,

24]. Community involvement is both a condition and a result of sustainable rural tourism and, when well-managed, produces social, cultural and economic benefits while increasing resilience.

[

23] identify three distinct forms of community involvement, ranging from 'giving back' to 'building bridges' to 'changing society'. These approaches have been categorised as transactional, transitional and transformational, respectively. In transactional and transitional engagement, control of the engagement lies with the company and the benefits are distinct between the parties. It can provide communities with valuable information, training, capacity building and knowledge, while for companies the main benefit is increased social legitimacy through the demonstration of social responsibility and awareness within the community. In transformational engagement, control is shared and leads to joint benefits, involving joint learning between the company and the community. A successful community engagement strategy involves matching the context and the engagement process in order to achieve the best results for the company and the community. In the case studies, we were able to distinguish between the Planalto Association, which is the closest example of community engagement, a transformational engagement involving artisans, blacksmiths and breeders in programmes, Casa da Montanha, which is closer to a transitional model, dependent on the indirect collaboration of artisans and local suppliers, and Mergulho Serrano, which operates between the transactional and transitional, using the services of cafés and local festival committees, but with control concentrated in the hands of the entrepreneur.

2.5.1. Positive Aspects of Community Involvement

Collaboration and Cooperation

Collaboration and cooperation between different tourism stakeholders, together with active community participation, are fundamental to building more inclusive, resilient and sustainable tourism. For [

25], cooperation between local businesses increases visibility and diversity of supply, enabling forms of commercialisation promoted by joint marketing campaigns. This cooperation, as identified by [

7], is vital for minimising risks in crisis situations, reinforcing its relevance as a mechanism for resilience. [

26] demonstrate that this cooperation not only benefits rural tourism and the community, but also brings self-confidence and empowerment, enabling them to navigate political environments and secure funding for projects of social interest. [

27], in exploring participatory methodologies such as the design of geotourism maps, where local inhabitants suggest tourist sites, reinforce the importance of forums where residents express their concerns about tourism development and contribute to a sense of control over their environment.

Preservation of Local Culture and Traditions

Community involvement plays a crucial role in heritage preservation, as it ensures that living traditions and cultural practices are maintained and shared with visitors, in addition to promoting a sense of pride among residents [

7,

28]. [

17] emphasise that tourism can also play an important role in revitalising local traditions and customs, reviving customs and knowledge that were at risk of disappearing. [

29] points out that rural tourism can simultaneously keep existing cultural heritage alive and breathe new life into almost forgotten practices and traditions.

Creating Memorable Tourism Experiences

Community integration and the promotion of cultural events are essential aspects for the success of local tourism. By valuing and preserving the cultural identity of a region, these strategies contribute to more authentic and sustainable tourism, benefiting both visitors and the resident population. [

16], festivals and other local cultural events are effective mechanisms for promoting culture and attracting visitors, while encouraging entrepreneurship and the development of tourism infrastructure. [

7] add that when the community is involved in the process of promoting tourism, tourists can experience local traditions and lifestyles in a genuine way, and tourists who establish meaningful connections with the community demonstrate greater loyalty and tend to return to the locations, which strengthens the relationship between tourists and residents. [

30] and [

26] highlight that individuals who participate in local organisations and cultivate friendships within the community have higher levels of connection to the place where they live. This sense of belonging not only improves social cohesion but also contributes to the sustainable development of tourism.

Social Interaction

Community-based tourism contributes to strengthening local identity and revitalising the social fabric. Authors such as [

16,

26,

27,

30] and [

7] converge in emphasising that the active participation of residents stimulates collaboration, social cohesion and improved quality of life, in addition to providing entertainment and promoting cultural exchange between residents and tourists. This intercultural contact not only boosts the local economy but also allows for the exchange of experience and knowledge, promoting a more inclusive and diverse environment [

17].

Economic and Social Benefits

As identified by [

17], communities see tourism as a tool for regional economic development, creating job opportunities and increasing revenue, diversifying business activity, and investing in local services and infrastructure. This positive perception of the sector encourages collaboration and community involvement in tourism initiatives [

27]. And as highlighted by [

28,

31] and [

7], community involvement in promoting tourism activities contributes not only to economic development but also to improving the local quality of life. Another important aspect of collective mobilisation is access to resources that might otherwise be inaccessible, such as funding, expertise and support from local authorities [

26].

Knowledge Sharing and Risk Prevention

By establishing connections with the community, [

25] and [

7] concluded that businesses strengthen their competitiveness and resilience, especially in times of crisis, as local knowledge and resources are essential to mitigate these risks. Sharing business strategies helps other entrepreneurs avoid pitfalls and improve their business operations [

13]. Local networks also reduce financial risks and facilitate the promotion of a region at a more affordable cost. Joint initiatives allow for the sharing of investments in marketing and infrastructure, benefiting all involved and strengthening the image and attractiveness of the tourist destination [

25,

32]. Other centers for knowledge sharing are local associations, partnerships with universities and collaboration with public organisations. These networks play an essential role in business growth, and interactions with these institutions promote the sharing of knowledge and good practices, providing access to new technologies, financing and public policies that can contribute to sustainable business development [

32].

The analysis of the three cases confirms many positive aspects identified in the literature. The Planalto Association exemplifies the potential for collaboration and cooperation in local networks, involving blacksmiths, breeders, and artisans in educational and environmental tourism programmes. Casa da Montanha shows how the preservation of local culture and traditions can be transformed into a distinctive feature in rural accommodation, by restoring traditional architecture and valuing local materials. In the case of Mergulho Serrano, we see how the creation of memorable tourist experiences can be rooted in individual passions, converting activities such as diving into innovative tourist products. A common point in all cases is the strengthening of social interaction, either through the proximity between hosts and tourists or through the involvement of the community in joint events and activities. Finally, it can be seen that the three projects generate economic and social benefits, albeit on different scales, contributing to employment, income circulation and the strengthening of local networks. In short, the case studies confirm that community involvement is not only a resource but a pillar for the sustainability and authenticity of rural tourism.

2.5.2. Negative Aspects of Community Involvement

Economic Impact

The growth of tourism can have various economic and social impacts on local communities. One of the most significant negative effects is the increase in the cost of living, a phenomenon that occurs due to price inflation driven by high tourist demand [

7,

27,

33]. Other negative economic aspects of tourism, pointed out by [

31], are property speculation and the economic flight of profits generated by the sector by large operators, which undermines local redistribution. [

30] emphasise that integration with external markets tends to reduce the involvement of the local community, as individuals are more connected to a wider consumer society than their immediate community, which reduces community ties and the importance of local involvement [

30].

Lack of Institutional Support and Bureaucratic Challenges

Community efforts are fundamental to sustainable development and social cohesion, but they often face significant challenges due to political and bureaucratic constraints. Complex government regulations and excessive bureaucracy can make establishing and maintaining cooperative networks more complicated, discouraging collaboration between different social actors [

25]. Furthermore, a lack of financial resources and ineffective policies can hamper the implementation of local initiatives, compromising their impact and continuity [

7].

Excessive dependence on local networks can also represent a barrier to long-term growth. Companies and organisations that focus exclusively on local markets may find it difficult to expand their operations to foreign markets, limiting their growth potential and competitiveness [

32]. It is therefore essential that community strategies are balanced, promoting both local collaboration and connection with broader networks to maximise opportunities and strengthen the resilience of projects. On the other hand, companies that remain isolated from key knowledge-sharing groups may have limited access to valuable information and innovation opportunities [

32].

Coordination and Leadership

The absence of structured communication between community members and weak leadership can compromise the effectiveness of the tourism network, generate disorganisation, and reduce the ability to respond to emerging challenges, as pointed out by [

25]. [

7] demonstrate that when there is no structured emergency plan to deal with unexpected situations, the instinct for survival often leads to fragmented responses, in which local stakeholders resort to individual and specific solutions to the problems they face, rather than adopting coordinated and systematic approaches.

Even community-led tourism projects that rely on volunteer work require management and economic planning skills, which are often neglected. The lack of these skills can compromise the long-term viability of initiatives, hindering their sustainability and growth [

26]. For community-based tourism to thrive sustainably, it is essential to implement well-structured strategies, strengthen local leadership, promote dialogue among stakeholders, and provide training in management and economic planning. When the community feels powerless in making decisions about tourism development in their region, there is a tendency for negative perceptions of tourism to develop [

33], which can compromise community involvement and generate resistance to proposed initiatives.

Risk of Dependence on Tourism

Tourism plays a crucial role in the economy of many regions, but over-reliance on this activity can make communities vulnerable to external crises such as natural disasters, pandemics or economic instability. [

7] and [

27], highlight that events such as fires or other natural disasters can drive tourists away significantly impacting the local economy. This vulnerability is even more evident in destinations where tourism is seasonal, as it can result in periods of economic hardship for the population. The economic instability caused by the seasonality of tourism can lead to significant challenges, including a lack of employment opportunities and reduced income during periods of low demand. This reinforces the need for strategies that diversify the local economy, reducing exclusive dependence on tourism.

2.5.3. Asymmetries Between Stakeholders and Different Points of View

As mentioned by [

25], power imbalances and differences in resources can make cooperation between different social and economic agents a challenging task. The authors also highlight that in collective contexts, some parties may prioritise their own gains over shared benefits, which often results in breakdowns in cooperation and difficulties in maintaining a collaborative environment. Another point that leads to social divisions and resentment is the fact that some residents benefit economically from tourism and others do not, as pointed out by [

27]. This scenario accentuates tensions within the community and hinders the creation of a collective vision. Community participation can sometimes be seen as inefficient. [

31] discuss how this process leads to power struggles, excessive time commitments, and funding shortages, which hinder the implementation of practical and sustainable solutions involving the community.

Residential stability, which on the one hand promotes social ties, can paradoxically reduce people's connection to the community. [

30] identify that lack of mobility and prolonged stay in a given locality can cause individuals to focus more on their personal and immediate relationships than on broader collective issues. Longer-established entrepreneurs, on the other hand, take greater advantage of community ties and support networks, creating competitive disparities with new entrepreneurs and smaller businesses [

32].

2.5.4. Cultural Challenges

There are some concerns that cultural events may become more tourist-oriented than community-oriented, resulting in a loss of authenticity and a prioritisation of profits over cultural significance [

28]. This can lead to the decharacterisation of local traditions and the transformation of genuine cultural manifestations into mere spectacles for external consumption. The literature has documented risks associated with this process, such as the folklorisation of traditions [

34], their commodification as tourist products, and even the creation of staged authenticity, in which cultural manifestations are artificially adapted to satisfy external expectations [

17,

35].

In locations where there is strong social cohesion, business expansion can be hampered, as these entrepreneurs may be perceived as serving only the interests of their own group. This restrictive view can limit the growth and diversification of economic opportunities, preventing integration with broader and more sustainable markets [

36]. There is also difficulty in breaking traditional business mindsets in rural areas, which slows down the adoption of innovation [

13].

2.5.5. Social Challenges

The acceptance of new projects may encounter initial resistance within the community due to institutional and social barriers, requiring a continuous effort to convince residents of their benefits and ensure their active participation over time [

13,

26].

Tourism can also pose significant challenges for local communities. One of the most obvious problems is traffic congestion and overcrowding in public areas, which, together with increased crime rates, gambling and drug trafficking, create conflicts between tourists and residents, undermining social cohesion [

17,

26].

The three cases analysed also allow us to observe the challenges and weaknesses pointed out in the literature. Casa da Montanha, for example, faces unfair competition from informal accommodation, reflecting the problem of economic impact and lack of institutional and/ y support. The Planalto Association, despite its central role in the community, faces bureaucratic and institutional barriers that limit the implementation of projects, as well as internal tensions over who benefits most from tourism. In the case of Mergulho Serrano, dependence on seasonality is evident, reinforcing the risk of economic vulnerability associated with rural tourism. In all cases, there are still asymmetries between stakeholders, as more established entrepreneurs or those with larger networks tend to reap greater benefits. Finally, both the Planalto Association and Casa da Montanha face difficulties in overcoming cultural and social resistance, which sometimes limits innovation and hinders the full integration of new ideas. Thus, the case studies confirm that community involvement, despite its benefits, is also a process marked by tensions, inequalities and structural barriers that cannot be ignored in the debate on the sustainable development of rural tourism.

3. Methodology

In order to understand the barriers faced by EEV in low-density areas, with a special focus on the Planalto Mirandês, a qualitative approach was adopted to capture their experiences, values and narratives in depth, through the collection of descriptive and interpretative data.

The Planalto Mirandês is located in the district of Bragança and extends across the municipalities of Mirando do Douro, Mogadouro, Vimioso and part of Freixo de Espada à Cinta and Torre de Moncorvo, bordered by the Douro and Sabor rivers. It is a sparsely populated area, marked by progressive depopulation, an ageing population and weak economic diversification [

4,

37]. Despite these constraints, the region is known for its rich cultural heritage and natural landscapes, notably the Douro International Natural Park, which is part of the UNESCO-designated Meseta Ibérica Transfrontier Biosphere Reserve, giving it high ecological value and potential for nature tourism activities.

These characteristics, combined with cultural authenticity and landscape, make the Planalto Mirandês a destination with strong tourism potential in the rural, cultural and environmental tourism segments. The choice of this territory for the present study is thus justified by its relevance as a representative example of a low-density region, where EEV play a central role in economic, social and cultural revitalisation.

To achieve this objective, a comparative case study strategy was used. This methodological design allows for the systematic exploration of different realities that share common characteristics, making it possible to identify patterns, contrasts and singularities [

8]. Although the sample consists of only three cases, their diversity ensures interpretative richness: Casa da Montanha, a rural accommodation project that values traditional architecture; Mergulho Serrano, an adventure tourism company specialising in outdoor activities; and Associação Planalto, an association dedicated to the preservation of the Miranda Donkey, which integrates environmental and educational tourism programmes. This selection resulted from the relevance of each project to the territory of the Planalto Mirandês and its representativeness as examples of lifestyle entrepreneurship.

After selecting the cases, semi-structured interviews were conducted as a method of data collection, guided by a script previously prepared based on a review of the literature. The script covered topics such as motivations, relationship with the territory, community involvement, innovation, challenges, and institutional support. The interviews were conducted online with those responsible for the projects and lasted an average of 30 to 45 minutes. They were recorded, transcribed and subsequently analysed, based on thematic analysis, following the steps suggested by [

38]: familiarisation with the data through intensive reading of the transcripts; the creation of initial codes, with the identification of relevant characteristics in the data; the construction of themes, through the grouping of codes into thematic categories; the review of themes, where thematic coherence and relevance were verified; and finally the production of a narrative, writing the final analysis with illustrative excerpts and theoretical discussions. To operationalise this analysis, the responses were organised in an Excel file, structured by question and interviewee, which allowed for a comparative view of the three cases. Additionally, digital support tools such as ChatGPT were used, which enabled a preliminary exploration of patterns and codes. However, a final validation and interpretation of the results was carried out to ensure the consistency and scientific rigour of the study. The process culminated in the preparation of a summary table with themes, sub-themes and empirical examples, which will be presented in the Results and Discussion section.

In order to reinforce the credibility of the research, several validation strategies were considered. Triangulation between empirical data and literature allowed to verify the consistency of the results, while recognising the contextual particularities of the cases studied.

Ethical Considerations

Participants were informed in advance about the objectives of the interview and consented to participate voluntarily. For ethical and confidentiality reasons, the names of individuals and organisations have been replaced with pseudonyms.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Motivations of Lifestyle Entrepreneurs

Through quantitative analysis of the three EEV case studies, distinct profiles are identified, but at the same time common in terms of the impacts and challenges of rural tourism. Casa da Montanha, Associação Planalto and Mergulho Serrano demonstrate how personal passion, relationship and knowledge of the territory, and community involvement are the basis of initiatives that contribute to the economic, environmental and social sustainability of the region, as defined in the literature on EEV [

5,

6,

12]. Beatriz Campos, Júlia Pereira and Hélder do Carmo all draw on their knowledge and previous experience to create unique value propositions adapted to the rural context. The motivation of these entrepreneurs is not profit maximisation, but rather personal fulfilment and contributing to the community, as Beatriz states (Casa da Montanha): "I bought this (...) two or three years after coming to live and work here, in the Planalto, always with the idea of one day being able to transform it into a rural tourism house, a space, an integrated nature tourism project, which only happened many years later." These testimonies illustrate the coexistence of push factors, such as the search for greater autonomy and a sense of purpose, and pull factors, such as the attraction exerted by the landscape and local community, as described by [

15]. In the interviews conducted, it was clear that personal passion and a strong emotional connection to the territory are central drivers for these entrepreneurs, which translate into a dedication that goes beyond economic rationality. This dimension is close to the concept of labour of love, discussed by [

39], who describe lifestyle entrepreneurship as a form of occupational devotion, where work is experienced as an expression of values and identity. The diversity of motivations confirms the typology proposed by [

6], distinguishing profiles oriented by expression, activity, and location.

4.2. Community Involvement

With regard to community involvement and using the models of [

23], three distinct forms of community involvement are identified, with the Planalto Association as an example of transformational involvement, where the community went from being resistant to co-authoring the project, as identified by Júlia, "... in the beginning, it was really hard work to break ground, to gain people's trust, but today we have been in the territory for quite some time, and they consider our work essential." In the case of Casa da Montanha, we are talking about collaborative involvement, based on the transmission of local knowledge, as mentioned by Beatriz, the village where they settled. "...there is the history of the roof tiles, the tiles of this village and all the villages around here were made here..." and they made a point of keeping the original tiles, "we use materials from here, stone, wood, clay, and yes, with knowledge we acquired from people who lived here...":Mergulho Serrano, on the other hand, has a more tactical approach, through the coordination of activities, as identified by Helder, from Mergulho Serrano, "...I arrange at that café that we're going to stop at...", "...I made sure that lunches and snacks (...) were in villages, we never took meals with us. I talked to people in the villages we passed through and tried to work with the Festival Committees...". The literature emphasises that sustainable rural tourism depends on a close relationship between the community and entrepreneurs [

23,

24]. Empirical data reinforces this view but also reveal the difficulty in transforming this relationship into effective and balanced participation, suggesting the need for policies that encourage collaborative governance models [

7].

4.3. Innovation and Authenticity

One area that is evident in all three projects is innovation, although it manifests itself differently in each case. At Casa da Montanha, innovation is linked to the restoration and authenticity of local heritage, as Beatriz explains: “Even in terms of the history of the house, which we also recount and pass on to our guests. All this information about how it used to be, where the animals were kept, how daily life was organised. And then also (...) the question of the materials we used, (...) we made a point of keeping...". At Associação Planalto, it is about social innovation, through the promotion of the Miranda donkey and environmental education, which ultimately arose from a need to finance the association, according to Júlia, "...if we are only dependent on applications, it often goes wrong. That's why our work is so diverse, whether it's visiting the centers, hiking, workshops, working with schools, or working with the community. So we really have to try to diversify our work as much as possible, and it's very important to involve the civil community, particularly through the sponsorship campaign, which is proving very successful at the moment. We have been involving more and more people, which is making us very happy. At Mergulho Serrano, we talk about product innovation, with the creation of a diving school in a rural mountain setting, "...a diving school was legalised in Trás-os-Montes and we obtained the Padi Five Star Dive Centre badge". These forms of innovation are in line with the innovation models described by [

16] and [

12]. In all three cases, it was the high degree of integration with the community and local knowledge that enabled the creation of new tourism products and experiences based on local uniqueness, as already confirmed in the study by [

1].

4.4. Structural Challenges

The three cases highlight challenges common to low-density territories, such as seasonality, lack of institutional support, and informal competition. Henrique (Mergulho Serrano) highlights unfair competition from unauthorised vessels: "...I come across boats, illegal vessels engaged in sport fishing, almost every day, I come across local accommodation providers organising tours and excursions, I come across local accommodation providers taking their dormitory guests on boat trips in their private boats, in other words, they do not have a maritime or tourist licence." Júlia (Associação Planalto) points out the bureaucratic obstacles and the lack of funding, "in these applications, namely to the Environmental Fund, there are non-governmental environmental associations, municipalities, parish councils, universities. And sometimes it's not very fair, because the resources that an association has cannot be compared to those of a municipality or even a university. So sometimes it's a little unfair. In a depopulated area, we cannot have the same impact as in a large urban center. So sometimes there are some imbalances here that should be adjusted a little...". Beatriz Campos (Casa da Montanha) mentions the high vulnerability to seasonal fluctuations, "...we receive most of our visitors at Easter, during Holy Week, and then in the summer." These results confirm the concerns raised by [

31] and [

33] about the risks of dependence on tourism and the asymmetries between the different stakeholders. At the same time, they reveal gaps between the political discourse promoting the interior and the reality experienced by entrepreneurs, where the weight of informality and bureaucracy weakens competitiveness.

4.5. Contribution to the Territory

Finally, it is worth highlighting the contribution of the three projects to the revitalisation of the territory, whether through cultural promotion, the retention of young people, or even the diversification of tourism. These projects reinforce the idea that rural tourism, when aligned with local values and led by committed entrepreneurs, can be an important lever for low-density territories. We see this contribution in Casa da Montanha, where care is taken to restore and enhance the architectural and cultural heritage, with the development of rural, sustainable and diversified tourism, integrated with the local community. Through the Planalto Association, which protects and conserves the Miranda Donkey, with environmental education and cultural awareness programmes, activities with the local community, with various tourist activities and national and international volunteer programmes, which strengthen social cohesion and the economic sustainability of the Planalto Mirandês, acting as a driving force for the preservation of cultural and natural heritage and encouraging the local population to stay and participate. Finally, Mergulho Serrano promotes legalised and structured adventure tourism, integrating and economically valuing local communities, promoting environmental education and awareness of natural resources, and establishing a pioneering model of sustainable tourism, contributing to the revitalisation of the depopulated territory of the Planalto Mirandês. It is therefore important to create conditions for these entrepreneurs to be replicable examples, supported by effective institutional networks that promote training programmes and a legal framework that recognises the specificities of innovative rural tourism.

Table 2 shows that, although motivations and models of action vary between the three cases, there is a common basis of connection to the territory, personal purpose and community involvement. However, structural challenges, such as informal competition and the fragility of institutional support, are cross-cutting.

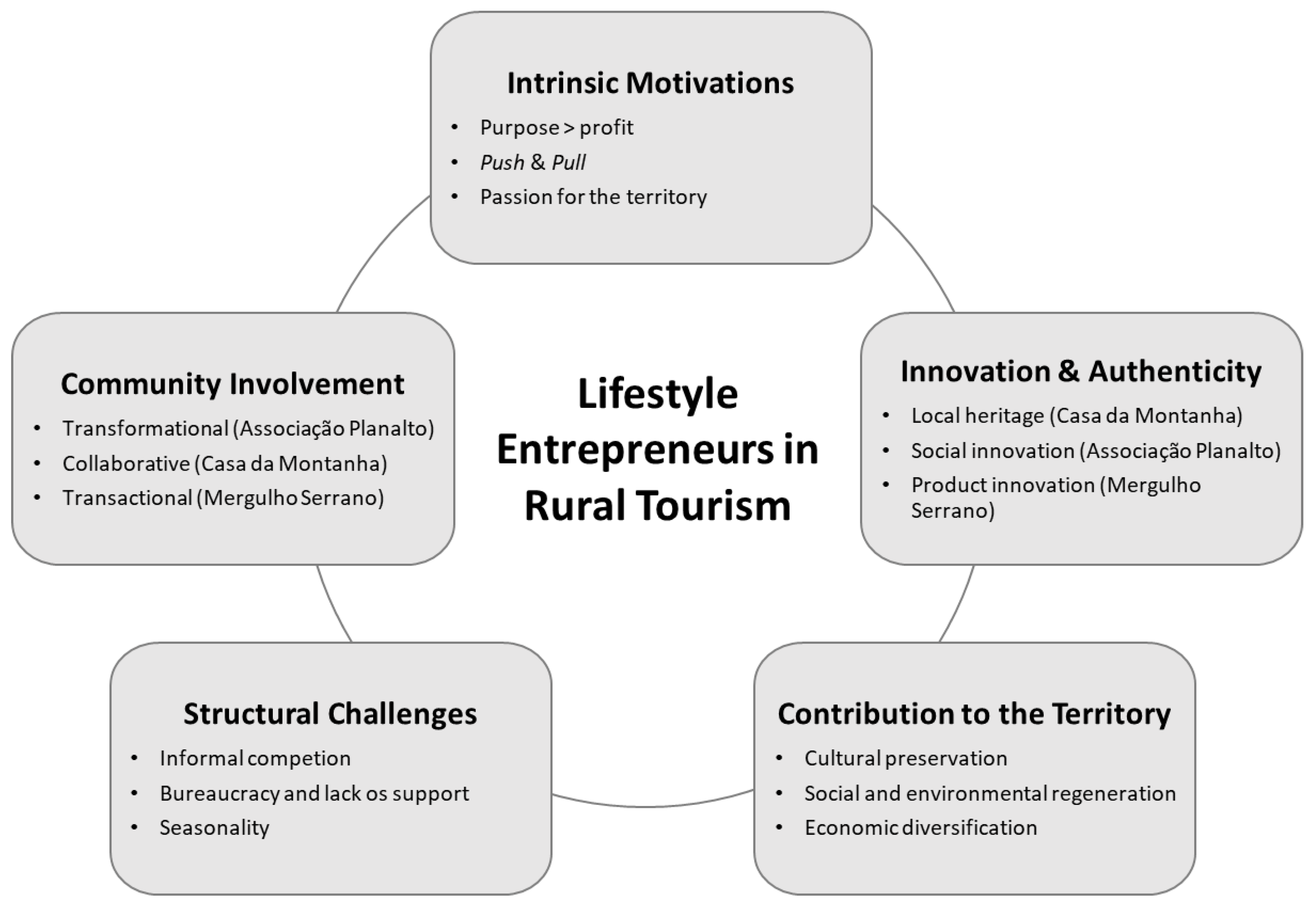

The results were synthesised into a conceptual model that seeks to illustrate the main findings of the study of lifestyle entrepreneurship in low-density territories (

Figure 1). The diagram highlights five interdependent axes: the intrinsic motivations of entrepreneurs, which focus on purpose, connection to the territory and the search for a balance between personal and professional life; community involvement, which manifests itself in different degrees, from transformational co-authoring practices (Associação Planalto) to collaborative approaches based on the transmission of local knowledge (Casa da Montanha), to more transactional and ad hoc models of coordination (Mergulho Serrano); innovation and authenticity, which takes different forms such as heritage enhancement, social innovation, or diversification of tourism products; structural challenges, namely informal competition, bureaucracy, and seasonality, which cut across all cases; and contributions to the territory, visible in cultural preservation, social and environmental regeneration, and economic diversification. This diagram provides an integrated view of how lifestyle entrepreneurs, motivated by personal and territorial factors, build rooted and innovative business models, but face structural barriers that limit their impact, even though they contribute significantly to the sustainability of low-density territories.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This dissertation contributes to the knowledge of EEVs in low-density territories, demonstrating their relevance in tourism and territorial regeneration. Through the analysis of the three case studies — Casa da Montanha, Associação Planalto and Mergulho Serrano — it is confirmed that EEV do not fit into traditional models of profit-oriented entrepreneurship, but rather are driven by the value placed on personal life, individual fulfilment and community contribution. In addition, different forms of motivation, innovation, community involvement and contributions to local development were identified. All the projects analysed share an intrinsic motivation based on their connection to the territory, the appreciation of natural and cultural heritage, and the desire for an alternative way of life. Their involvement with the community varies in intensity, but it is always present as a structuring element of the identity of each project. In turn, their initiatives have proven to be innovative, rooted in social and contextual innovation, guided by authenticity and endogenous knowledge, ranging from the application of traditional construction methods with the enhancement of local products to the creation of distinctive tourism products such as donkey tourism and a diving school in a rural mountainous area. This perspective broadens the understanding of the role of EEV in territorial sustainability, showing that, despite limitations in scale and resources, these entrepreneurs can be drivers of change in rural contexts. EEV demonstrate that it is possible to create innovative projects with a connection to their roots, to create value with purpose, and to regenerate territories through more ethical, sustainable, and identity-based tourism.

5.2. Practical Implications

From a practical point of view, the results offer relevant clues for both entrepreneurs and policy makers. For entrepreneurs, this dissertation shows the importance of cultivating local networks, involving the community, even if at different levels of collaboration, and valuing endogenous resources as a differentiating factor. Investing in authentic and sustainable projects proves to be a strategy for economic viability and a way to increase the resilience of projects.

For policy makers, some structural weaknesses are demonstrated that condition the sustainability of projects, such as the informality of competition, the ineffectiveness of institutional support, bureaucratic rigidity and the absence of integrated strategies on the part of local authorities and public entities. These weaknesses limit the potential for replication and scalability of projects of this type. There is a clear need for public policies tailored to the specificities of low-density territories, which reduce bureaucracy, promote the formalisation of tourism activities, combat unfair competition and support social and cultural innovation. Collaborative governance should also be promoted in order to strengthen the impact of this agent on local development. EEV should be recognised as a strategic partner in the design of sustainable tourism and territorial cohesion policies. It is important to recognise EEV as active agents of territorial transformation. It is necessary to develop more flexible public policies, training in tourism and entrepreneurship, and support mechanisms tailored to the reality of low-density territories.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Despite its contribution, this study has some limitations, such as the small number of cases and participants, which does not allow for statistical generalisations. The aim was to explore specific phenomena in depth, but it would be relevant to extend the study to other territories and sectors to verify the consistency of the results. Another limitation is the dependence on the interviewees' narratives, which leads to some subjectivity; it would be necessary to supplement this approach with other sources of data.

For future research, it is suggested to expand the sample to include different types of entrepreneurs in both the tourism sector and other areas of activity. Compare cases in different geographical contexts in order to identify dynamics according to local resources and policies. Include an approach by the local population on the impact of EEV in the territory. Investigate the long-term impact of EEV on population retention, cultural transformation and environmental sustainability.

References

- Dias, Á. , & Silva, G. M. Lifestyle entrepreneurship and innovation in rural areas: The case of tourism entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Strategy 2021, 31, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A. , & Atterton, J. Exploring the contribution of rural enterprises to local resilience. Journal of Rural Studies 2015, 40, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, R. , & Craig, L. Managing tourism enterprises : start-up, growth and resilience.

- National Statistics Institute (INE). (2017). Territorial Portrait of Portugal. Lisbon: INE.

- Cunha, C. , Kastenholz, E. , & Carneiro, M. J. Entrepreneurs in rural tourism: Do lifestyle motivations contribute to management practices that enhance sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2020, 44, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanycheva, D. , Schulze, W. S., Lundmark, E., & Chirico, F. (2024). Lifestyle Entrepreneurship: Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. In Journal of Management Studies (Vol. 61, Issue 5, pp. 2251–2286). John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E. , Brites Salgado, M. A., & Silva, R. Resilient and regenerative Rural Tourism: the case of Travancinha Village, Portugal. Cadernos de Geografia 2023, 48, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. , & Campbell, D. T. (2018). Case study research and applications: design and methods. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Dias, Á. (2024). Lifestyle Entrepreneurship - Combining Passion and Profit in Tourism. Actual Editora.

- Dias, Á. , & Patuleia, M. Commentary: Attitudes of local population of tourism development impacts: Evidence from Czechia. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 727287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, M. , Dias, Á. Measuring Sustainable Tourism Lifestyle Entrepreneurship Orientation to Improve Tourist Experience. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á. , Silva, G. M., Patuleia, M., & González-Rodríguez, M. R. Developing sustainable business models: local knowledge acquisition and tourism lifestyle entrepreneurship. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2023, 31, 931–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, W. W., Y. , & Eesley, Charles. E. (2023). Take Me Home, Country Roads: Return Migration and Platform-enabled Entrepreneurship, Organisation Science, Johns Hopkins Carey Business School Research Paper No. 24-09. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4657476.

- Gómez-Baggethun, E. (2022). Is there a future for indigenous and local knowledge? Journal of Peasant Studies, 49, 1139–1157. [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J. L. Motivations for Pleasure Vacations. Annals of Tourism Research 1979, 6, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á. , Hallak, R., & Patuleia, M. (2024). Entrepreneurial Passion: A Key Driver of Social Innovations for Tourism Firms. Entrepreneurship Research Journal. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. , Uysal, M., & Sirgy, M. J. (2013). How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tourism Management, 36, 527–540. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S. , Panzer-Krause, S., Zerbe, S., & Saurwein, M. (2024). Rural tourism in Europe from a landscape perspective: A systematic review. In European Journal of Tourism Research (Vol. 36). Varna University of Management. [CrossRef]

- Tong, J. , Li, Y., & Yang, Y. System Construction, Tourism Empowerment, and Community Participation: The Sustainable Way of Rural Tourism Development. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Castanho, R. A. , Couto, G. , Pimentel, P., Carvalho, C., Sousa, Á., & Batista, M. D. G. Analysing the public administration and decision-makers perceptions regarding the potential of rural tourism development in the Azores region. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning 2021, 16, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, C. , & Turner, L. W. Regional economic development and tourism: A literature review to highlight future directions for regional tourism research. Tourism Economics 2020, 26, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, T. , Driver, A., Frumento, P., Howard, T., Shuftal, B., & Whitmer, W. (2017). Community engagement for collective action: a handbook for practitioners.

- Bowen, F. , Newenham-Kahindi, A. , & Herremans, I. When suits meet roots: The antecedents and consequences of community engagement strategy. Journal of Business Ethics 2010, 95, 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khater, M. , & Faik, M. (2024). Tourism as a catalyst for resilience: Strategies for building sustainable and adaptive communities. Community Development. [CrossRef]

- Jesus, C. , & Franco, M. Cooperation networks in tourism: A study of hotels and rural tourism establishments in an inland region of Portugal. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2016, 29, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, M. T. , Hansen, A. V., Sørensen, F., Fuglsang, L., Sundbo, J., & Jensen, J. F. Collective tourism social entrepreneurship: A means for community mobilisation and social transformation. Annals of Tourism Research 2021, 88. [CrossRef]

- Boley, B. B. , McGehee, N. G., Perdue, R. R., & Long, P. Empowerment and resident attitudes toward tourism: Strengthening the theoretical foundation through a Weberian lens. Annals of Tourism Research 2014, 49, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A. L. , Costa Ventura Ramos, E. M., & Caldeira Heitor, J. Bread Festival as a promoter of the knowledge, traditions, culture and tourism of the municipality of Mafra. European Public and Social Innovation Review 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G. (2011) Preservation, Conservation and Heritage: Approaches to the Past in the Present through the Built Environment, Asian Anthropology, 10:1, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, J. , & Brown, R. B. A multilevel systemic model of community attachment: Assessing the relative importance of the community and individual levels. American Journal of Sociology 2010, 116, 503–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H. C. , & Murray, I. Resident attitudes toward sustainable community tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2010, 18, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, J. , Gómez, M. , & Brent Ross, R. Social Capital and Entrepreneurship in Emerging Wine Regions. Journal of Wine Economics 2018, 13, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D. , Ouyang, Z. , Nunkoo, R., & Wei, W. Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes towards tourism development: a meta-analysis. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management 2019, 28, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and commoditisation in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. (1999). The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. University of California Press. (1st edition 1976, reprinted 1999).

- Bakker, R. M. , & McMullen, J. S. Inclusive entrepreneurship: A call for a shared theoretical conversation about unconventional entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing 2023, 38. [CrossRef]

- Interministerial Coordination Commission (CIC), (2023), Resolution No. 2023.

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R. K. , Wiersma, C. , & Ajiee, R. O. “A labour of love”: Active lifestyle entrepreneurship (occupational devotion) during a time of COVID-19. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 2021, 3, 624457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).