Introduction

Presently, advancements in the treatment of neurological conditions have significantly progressed, particularly in the realm of neurointerventional radiology (INR). INR represents a form of minimal invasive surgery for neurological conditions, predominantly conducted under general anesthesia to ensure precise and high-quality imaging. Additionally, it allows for the control of intracranial pressure.[

1] One crucial consideration in the general anesthesia for neurointerventional radiology is the ability for the patients to rapidly awaken, comprehend, and cooperate, which facilitates the immediate assessment of neurological symptoms post-surgery.[

1]

Postoperative emergence agitation is a condition that can occur in a range of 5-30% [

2] of cases and is immediately evident after recovery from general anesthesia. [

3] This phenomenon can pose challenges in the assessment of neurological status following surgery, leading to difficulties in precision and accuracy. Such challenges can impact the evaluation of surgical outcomes, complications, and treatment planning, as well as may pose risks to the patient if the emergence agitation is severe.

The medications commonly used for muscle relaxation and general anesthesia in neurointerventional radiology procedures for the nervous system are the widely utilized muscle relaxant, sevoflurane, and the anesthetic, propofol, which is administered intravenously.[

4,

5] Despite extensive studies over the years, further research is required to advance our understanding of the risk factors associated with both patient-related factors and surgical factors, including those that are related to general anesthesia and emergence agitation post-recovery.[

6,

7]

Studies comparing emergence agitation during post-recovery from general anesthesia between these two types of medications have been conducted, but clear conclusions in various surgical procedures have not yet been reached. The majority of the research findings have indicated a higher risk of emergence agitation when using the muscle relaxant, sevoflurane, compared to other anesthetic agents. However, some studies have found no significant difference in emergence agitation between sevoflurane and propofol administered intravenously.[

8] Importantly, there is a lack of comparative studies on the outcomes of these two medications in neuro-interventional radiology procedures, which are considered minimally invasive surgeries involving needle punctures in the groin area. It is anticipated that these procedures may induce less stimulation and pain, both during and after surgery, compared to more invasive surgeries with larger incisions. Pain is a significant risk factor that contributes to the occurrence of emergence agitation post-recovery from general anesthesia.[

9]

Objectives

Primary objectives: In order to compare the incidence of emergence agitation post-recovery from general anesthesia between the muscle relaxant, sevoflurane, and the intravenously administered anesthetic, propofol, in neurointerventional radiology procedures, further studies are needed.

Secondary objectives: In order to compare the severity of emergence agitation post-recovery from general anesthesia, as well as the time-related parameters, such as the time to recovery, time to extubation, time to eye opening, time to orientation, incidences of postoperative nausea and vomiting, occurrences of hypotension, bradycardia, and the intensity of postoperative pain between the muscle relaxant, sevoflurane, and the intravenously administered anesthetic, propofol, in neuro-interventional radiology procedures, a detailed comparative study is necessary.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Khon Kaen University, in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines (Project ID: HE631514). Informed consent was obtained from all participating patients. This was a prospective randomized double-blind controlled trial. Patients, who underwent neurointerventional radiology procedures from 2021–2022 under general anesthesia at Srinagarind Hospital, but who did not urgently require general anesthesia, were enrolled. The inclusion criteria encompassed patients aged 18 to 65, with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status classification of 1 to 3, and a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. The exclusion criteria consisted of those patients, who had refused to participate and those who were unable to communicate. In addition, those individuals with known allergies or contraindications to the study drugs, those with a history of psychiatric disorders, and patients with chronic alcohol abuse or substance dependence were also excluded.

Patients, who met the inclusion criteria for undergoing neurointerventional radiology procedures, received an assessment and informational briefing from the research team at the patient ward on the day before the surgery. The details of the informational briefing consisted of the study objectives, study methods, the benefits for the patients, potential complications, and the care that they would receive in the event of any unforeseen complications. Additionally, the briefing outlined the method for assessing pain levels using a verbal numerical rating scale, in which a score of 0 indicated no pain and 10 represented the worst pain imaginable.

The 80 patients were randomly assigned to one of the two study groups, namely the sevoflurane group or the propofol group. The randomization was conducted using a computer program, employing a stratified randomization approach to ensure an equal distribution of male and female participants within each group. The assignment of patients to the study groups followed a predetermined sequence, and the randomization order was concealed within sealed envelopes. The personnel administering anesthesia opened the sealed envelopes, then implemented the assigned anesthesia protocol (sevoflurane or propofol) and managed the patient accordingly. Both the patients and the outcome assessors were blinded to the type of anesthesia that had been used. After the surgery was completed and before the assessors were allowed to enter the room, the anesthesia team ceased the administration of sevoflurane and discontinued propofol, removed the anesthesia apparatus, and collected the Target-Controlled Infusion (TCI) device. After that, the assessors, who were not present in the operating room during the procedure, entered the room and evaluated the outcomes.

Anesthetic Protocol

After explaining the research study procedures and obtaining the patients' signed consent on the night before the surgery, patients underwent the standard preoperative fasting protocols on the day of the surgery. The protocols consisted of abstaining from solid food for at least 6 hours and refraining from clear fluids or non-particulate liquids for at least 2 hours before the surgery. In the operating room, prior to the administration of anesthesia, patients received preoperative monitoring in accordance with standard anesthesia practices. This monitoring involved providing vigilant care by the anesthesia team, measuring and recording the vital signs (i.e., electrocardiogram (ECG), heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and blood oxygen saturation levels), and assessing the depth of anesthesia using the Bispectral Index (BIS). These measures aim to ensure the patients' safety and well-being during the induction of anesthesia.

Patients in the Sevoflurane group received a combination of medications for induction of anesthesia. This combination was composed of the opioid analgesic, fentanyl, at a dosage of 1-2 micrograms per kilogram, the induction agent, propofol, at a dosage of 1.5-2.5 milligrams per kilogram, the neuromuscular blocking agent, cisatracurium, at a dosage of 0.1-0.2 milligrams per kilogram, and dexamethasone at a dosage of 4 milligrams intravenously to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesia was maintained by using a combination of inhaled sevoflurane, air, and oxygen (Sevoflurane:Air:Oxygen) with a maximum oxygen concentration of 50 percent.

Patients in the Propofol group received a combination of medications for the induction of anesthesia. This consisted of the opioid analgesic, fentanyl, at a dosage of 1-2 micrograms per kilogram, the neuromuscular blocking agent, cis-atracurium, at a dosage of 0.1-0.2 milligrams per kilogram, and dexamethasone at a dosage of 4 milligrams intravenously to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Anesthesia maintenance in the Propofol group was achieved by using propofol administered through TCI. The Target effect-site concentration was set at 4 micrograms per milliliter. Additionally, the continuous intravenous administration of propofol was utilized for ongoing anesthesia control.

Summary of Anesthetic Protocols: This study compared two different general anesthesia techniques: one using inhaled sevoflurane and the other using intravenous propofol.

Control Group (Group S): Sevoflurane Anesthesia

Induction: Patients in this group were put to sleep with a single intravenous (IV) injection of propofol at a dose of 1.5-2.5 mg/kg.

Maintenance: Anesthesia was then maintained with inhaled sevoflurane gas, which was mixed with air and oxygen. The concentration of oxygen (FiO₂) was kept at a maximum of 50%.

Intervention Group (Group P): Propofol Anesthesia

Induction: Anesthesia was induced using propofol administered through a TCI pump. This device is programmed to achieve a target drug concentration of 4 mcg/mL in the brain (effect-site concentration, or Ce).

Maintenance: Anesthesia was maintained with a continuous IV infusion of propofol using the same TCI system. The anesthesiologist adjusted the target concentration as needed to keep the patient adequately anesthetized throughout the surgery.

The concentration of both sevoflurane and propofol were adjusted to maintain the Bispectral Index (BIS) within a range from 40-60. The neuromuscular blocking agent cis-atracurium was continuously administered intravenously at a rate of 1-2 micrograms per kilogram per minute in both groups. The end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) concentration during expiration was maintained at a level of 30-35 millimeters of mercury in both groups.

The vasoconstrictor, ephedrine, was used to maintain the mean arterial blood pressure at not lower than 20% of the patient's baseline mean arterial blood pressure or in cases in which the systolic blood pressure fell below 90 millimeters of mercury. Ephedrine was administered at a dose of 3 milligrams per infusion.

The heart rate stimulant atropine was given when the patient's heart rate fell below 50 beats per minute. Atropine was administered at a dose of 0.3 milligrams per infusion.

The neuro-interventional radiologist applied pressure to stop bleeding in the patient's leg for a minimum of 15 minutes. When compression on the leg started, the administration of muscle relaxants was halted. Once the radiation oncologist stopped or released the pressure to prevent bleeding, the administration of sevoflurane and propofol through the intravenous route was discontinued. The muscle relaxant effect was reversed by administering neostigmine at a dose of 0.05 milligrams per kilogram. Atropine was also given to prevent bradycardia. Additionally, both groups received 4 milligrams of ondansetron intravenously to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting. The patients were allowed time to wake up, and then the endotracheal tube was removed.

After the intervention, both groups of patients received 100% oxygen at the rate of 6 liters per minute. The endotracheal tube was removed after the patients had met the criteria, which consisted of having a sufficient response from the airways, having the ability to breathe adequately on their own, exhibiting sufficient muscle function (measured by handgrip strength, the ability to lift the head/legs, and holding up the head on command), and regaining consciousness.

The assessment of the postoperative emergence from general anesthesia was conducted immediately within five minutes after extubation. The Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) was used for this evaluation. The assessors, who were two members of the research team, were unaware of the type of anesthesia that had been used for sensory blockade. The research team ensured that the assessors had acquired a shared understanding of the defined terms and the severity of emergence agitation after sensory blockade suppression and that they had undergone a joint training for assessment. To ensure reliable data, inter-rater reliability was tested with Cohen’s Kappa coefficient (K) and exceeded 0.8 before actual data collection.

Outcomes and Measurements

The collected data was comprised of the duration until the moment that the patient had opened his/her eyes, the time to extubation, the time until the patient could correctly state his/her name, any incidents of hypotension and bradycardia, and the amounts of ephedrine and atropine that had been administered.

Afterwards, the patient was transferred to the observation room for monitoring at least one hour before being discharged to the patient ward. In the observation room, patients underwent pain assessment using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) immediately upon arrival and 30 minutes after having arrived. Pain management was initiated if the pain score was greater than 5, using 25 micrograms of fentanyl intravenously. If there were no improvement, additional doses were administered every 5 minutes (up to two doses).

During the observation period, occurrences of nausea and vomiting were recorded. Patients received 4 milligrams of ondansetron intravenously or 10 milligrams of metoclopramide intravenously in order to treat their nausea and vomiting.

This study collected basic patient information: age, gender, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), ASA physical status, duration of sensory blockade, and surgical duration.

The secondary study data consisted of RASS scores, duration of extubation, duration of ptosis (time until patients open their eyes), time until patients can correctly respond with their name, postoperative nausea and vomiting, blood pressure, and heart rate during sensory blockade, as well as the severity of postoperative pain.

Statistical Analysis

An a priori power analysis was conducted to determine the optimal sample size required to detect a statistically significant difference in the incidence of emergence agitation between the two groups. The calculation was based on the assumption of a two-sided test for the difference between two independent proportions.

Based on a previous study [

10], we hypothesized the incidence of emergence agitation to be p₁ = 0.025 for the propofol group (Group P) and p₂ = 0.25 for the sevoflurane group (Group S). With a specified Type I error rate (α = 0.05) and a desired power of 80% (β = 0.2), the analysis determined a minimum required sample of 34 subjects per arm.

To compensate for potential subject attrition, this number was adjusted for an anticipated dropout rate of 15%.

Therefore, to ensure adequate statistical power, the final target enrollment was rounded up to 40 participants per group, yielding a total study size of 80 patients.

This study analyzed its data using STATA version 10. For the categorical group data, frequencies and percentages were reported, and statistical tests, such as Pearson Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, were employed. For the continuous data, if normally distributed, the means and standard deviations were presented, along with statistical tests like the Independent t-test. In case of non-normally distributed data, the median and interquartile range were provided, and the statistical test used was the Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

Participant Characteristics

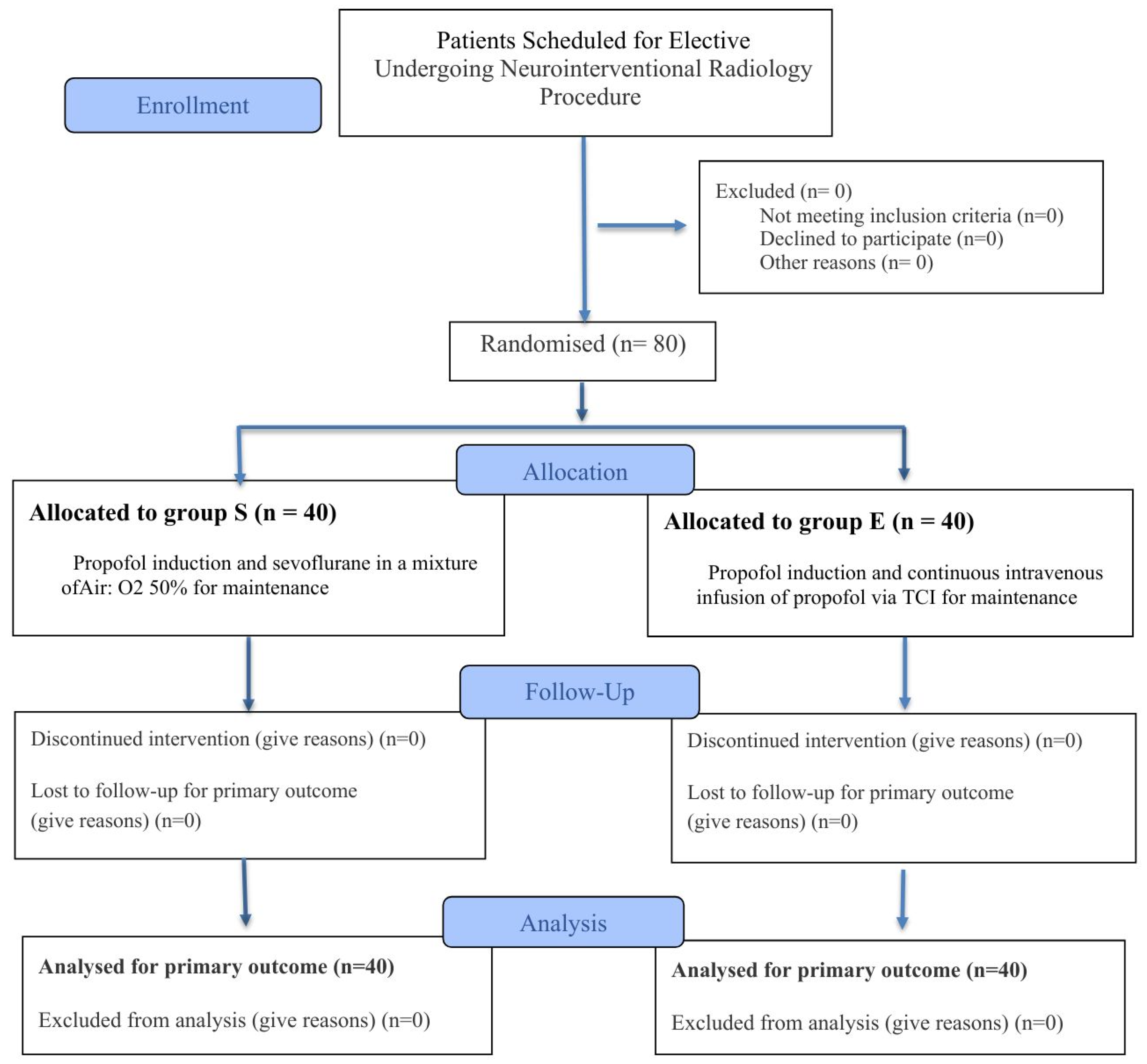

All 80 volunteers remained throughout the entire study, and no patient withdrew before completing the study period. The data for each patient was analyzed in the respective groups assigned from the beginning (

Figure 1). Basic demographic information for the patients in both groups showed similarities (

Table 1).

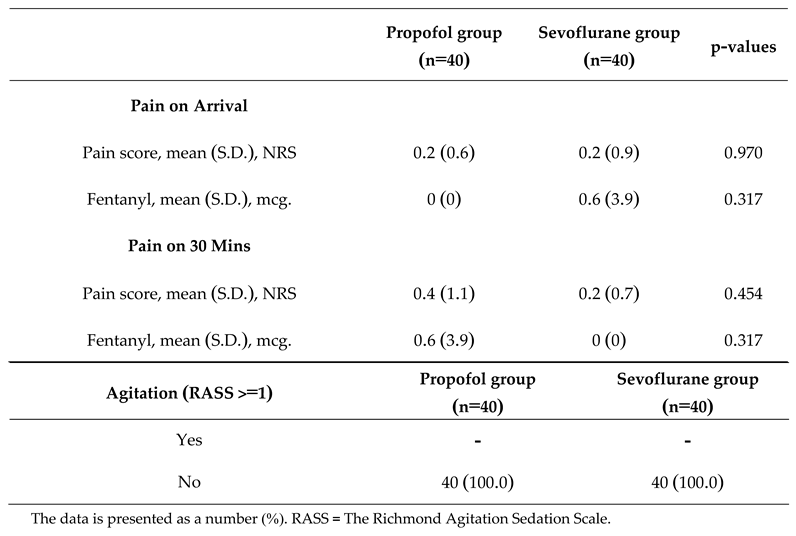

Quantitative data, including age, weight, height, duration of surgery, and duration of anesthesia, is presented in the mean (SD) format. Qualitative data, such as gender and ASA classification, is presented as counts and percentages. Regarding the main study outcomes, the incidence of emergence agitation, measured by RASS values greater than or equal to 1, was not observed in both groups (

Table 2).

Primary Outcomes

In the comparison of the severity of emergence agitation after regaining consciousness from anesthesia suppression, presented in the form of counts and percentages in both groups, it was found that in the propofol group, patients had a higher sedation score than the sevoflurane group. However, no statistically significant difference was observed (

Table 3).

Table 3.

The Severity of the Agitation/Sedation Scale.

Table 3.

The Severity of the Agitation/Sedation Scale.

| Scores |

Propofol group

(n=40) |

Sevoflurane group

(n=40) |

p-values

|

| -3 |

4 (10.0) |

2 (5.0) |

0.675 |

| -2 |

7 (17.5) |

6 (15.0) |

0.762 |

| -1 |

13 (32.5) |

19 (47.5) |

0.171 |

| 0 |

16 (40.0) |

13 (32.5) |

0.485 |

Table 4.

Recovery times.

| |

Propofol group

(n=40) |

Sevoflurane group

(n=40) |

p-values

|

Secondary Outcomes

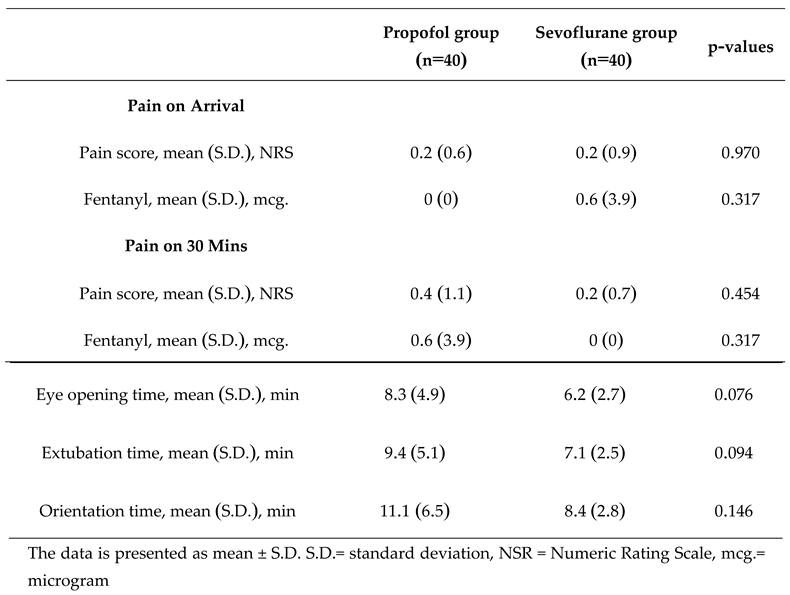

Regarding the duration of self-awareness, including the time it takes for patients to open their eyes, the duration of extubation, and the time it takes for patients to respond to their names, it was found that the sevoflurane group had shown a faster duration of self-awareness compared to the propofol group. This applies to the time it takes for patients to open their eyes, the duration of extubation, and the time it takes for patients to respond to their names. However, no statistically significant differences were observed (p=0.076, 0.094, and 0.146, respectively). Regarding postoperative pain, there was no difference between the two groups (

Table 5).

Adverse Events

Regarding the side effects related to hypotension, when comparing the dosage of ephedrine, it was found to be significantly higher in the sevoflurane group (p=0.031). In terms of bradycardia, comparing the use of atropine, it was found that the propofol group had used more medication, but the difference was not found to be statistically significant (p=0.317) (

Table 6).

Discussion

This randomized controlled study was designed to compare the effects of propofol-based total intravenous anesthesia and sevoflurane-based inhalation anesthesia on recovery profiles and hemodynamic stability in patients, who had undergone minimally invasive neurointerventional procedures. The primary finding was the complete absence of emergence agitation, defined as a Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale score ≥ +1, in both arms of the study. While the sevoflurane group had demonstrated a trend towards faster recovery, this did not reach statistical significance. Notably, significant hemodynamic differences were observed, with the sevoflurane group requiring more frequent intervention for hypotension.

Mechanisms of Agitation

The most striking result of this study is the zero incidence of EA in the cohort of 80 patients. Emergence agitation is a multifactorial phenomenon characterized by disorientation, restlessness, and hyperactivity during recovery from anesthesia, with reported incidences ranging from 5% to 30% in the general adult population [

11]. The complete absence of EA in our trial strongly supports the hypothesis, as suggested by Yu et al. [

12], that postoperative pain is a primary and potent trigger for this condition. The neurointerventional procedures performed in this study were characterized by minimal tissue trauma, low inflammatory response, and consequently, low levels of nociceptive input. This interpretation was corroborated by our finding of uniformly low postoperative pain scores (NRS), which did not differ between the groups.

Beyond pain, other contributing factors to EA include preoperative anxiety, residual effects of certain anesthetic agents, and physiological disturbances like bladder distension or hypoxia [

13]. Our study protocol, which utilized standardized, short-acting agents and BIS-guided anesthetic depth, likely minimized the pharmacological contribution to agitation. The controlled, minimally invasive nature of the procedure also obviates many of the physiological stressors that are associated with major open surgery. Therefore, our findings suggested that in the context of modern, low-pain surgical procedures, the choice between propofol and sevoflurane may have a negligible impact on the incidence of EA, as the principal trigger is effectively absent. This challenges results from earlier studies that found a higher incidence of EA with volatile anesthetics, which may have been conducted in more painful surgical settings where the intrinsic properties of the agents become more influential.

Comparative Effectiveness and Clinical Significance

A key secondary objective was to compare the recovery profiles. Our data revealed a consistent trend towards a more rapid recovery in the sevoflurane group across all the measured parameters: time to eye-opening (p=0.076), time to extubation (p=0.094), and time to correct name response (p=0.146). While these differences did not achieve statistical significance, the proximity of the p-values to the 0.05 threshold suggested that a clinically meaningful difference may exist, which our study was underpowered to definitively detect. A delay of even a few minutes can have significant implications for operating room turnover and patient flow in a high-volume interventional suite.

The lack of statistical significance likely stemmed from our rigorous, BIS-guided anesthetic maintenance. Unlike studies that titrate anesthesia based on hemodynamic parameters, which can lead to variable anesthetic depths, BIS monitoring ensures a comparable level of central nervous system depression among groups [

14]. This precise titration minimizes deep anesthesia, thereby standardizing the starting point for emergence and potentially masking the inherent pharmacokinetic differences between the drugs. This contrasts with findings from Castagnin et al., who reported statistically significant, albeit small, differences in recovery times [

15]. Our results suggested that when anesthetic depth is meticulously controlled with objective monitoring, the clinical differences in recovery speed between modern intravenous and inhaled agents may be attenuated to the point of being statistically indistinguishable in smaller cohorts.

Integration with Contemporary Interventional Radiology Practice

The findings of this study have direct implications for anesthetic practice in the interventional neuroradiology (INR) suite, particularly for neurovascular procedures. The goals in this setting are to provide immobility, ensure hemodynamic stability for optimal cerebral perfusion, and facilitate a rapid, smooth recovery for prompt neurological assessment [

16].

The sevoflurane group's profile presented a trade-off. The trend towards faster emergence is advantageous for high-throughput environments and enables more rapid neurological evaluation post-procedure. However, the significantly higher incidence of hypotension requiring vasopressor support is a critical concern. In neuro-interventional cases, maintaining stable mean arterial pressure is of paramount importance when seeking to prevent cerebral ischemia or to manage intracranial pressures [

16]. The vasodilation associated with sevoflurane, while manageable, introduces a level of hemodynamic instability that may be undesirable during the delicate phases of a procedure.

Conversely, propofol offered superior hemodynamic stability with significantly less need for ephedrine. This predictable blood pressure profile is highly advantageous for neurovascular patients for whom iatrogenic hypotension can have severe consequences. While recovery was marginally slower, it remained rapid and predictable, without any instances of agitation that could complicate immediate post-procedural care. Therefore, for contemporary INR practice, the choice of agent should be tailored to the specific procedural requirements and patient comorbidities. Propofol may be the preferred agent when hemodynamic stability is the highest priority, whereas sevoflurane could be considered for shorter cases in hemodynamically robust patients for whom rapid turnover is the primary operational goal.

Safety Profile and Clinical Implementation

Both anesthetic techniques demonstrated a high degree of safety in this cohort of predominantly healthy (ASA I-II) patients. The principal difference in the safety profile was hemodynamic. The significantly greater requirement for ephedrine in the sevoflurane group (p=0.031) confirmed the well-documented vasodilatory effects of volatile anesthetics [

17]. While this was effectively managed, it necessitates increased vigilance and pharmacological intervention from the anesthesiologist.

In the propofol group, there was a non-significant trend towards a greater use of atropine for bradycardia (p=0.317). This is consistent with propofol's known propensity to blunt the baroreceptor reflex, which can lead to unopposed vagal tone [

18]. Although it was not statistically significant here, it remains a known clinical consideration, particularly in patients with pre-existing low heart rates and those on beta-blockers.

Importantly, there were no differences in postoperative pain or the incidences of postoperative nausea and vomiting. The low rates of both complications were likely attributable to the minimally invasive nature of the procedures rather than to a specific property of the anesthetic agents. From the standpoint of clinical implementation, both agents are viable options, but the clinician must be prepared to manage their distinct and predictable side-effect profiles: hypotension with sevoflurane and the potential for bradycardia with propofol.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study had several limitations that warrant consideration. Firstly, the sample size of 80 patients, while sufficient to detect large differences, may have been underpowered to identify smaller, yet clinically relevant, differences in recovery times, which could have potentially led to a Type II error. The non-significant trends observed in the recovery metrics suggest this possibility. Secondly, the study was conducted at a single center with a specific patient population (ASA I-II), who underwent a narrow range of low-pain procedures. These results may not be generalizable to sicker patients or to those undergoing more extensive, painful surgeries in which EA is more common. Thirdly, our definition of EA (RASS ≥ +1) was specific and may not have captured the more subtle forms of emergence delirium.

Future research should be directed towards several key areas. A large-scale, multicenter randomized controlled trial is needed to definitively determine if there are statistically significant differences in recovery times between BIS-guided propofol and sevoflurane anesthesia. Such a study would have the statistical power to clarify the clinical significance of the trends observed here. Furthermore, comparative studies conducted among different surgical populations, particularly those undergoing moderately to severely painful procedures, are essential to elucidate whether the choice of primary anesthetic agent can influence the incidence of EA when a powerful trigger like pain is present. Finally, future investigations could incorporate patient-centered outcomes, such as the quality of recovery scores (e.g., QoR-40) and patient satisfaction, to provide a more holistic comparison of these two common anesthetic techniques.

Conclusions

In patients undergoing neurointerventional radiology, no incidence of post-anesthetic emergence agitation was observed in either the group that had received the inhaled sevoflurane or the group that had received intravenous propofol. However, a notable difference in hemodynamic stability was identified. Compared to the propofol group, the sevoflurane group had experienced a significantly higher incidence of hypotension that required treatment with vasopressor agents.

Trial registration: This study was reviewed and approved by the TCTR (Thai Clinical Trials Registry) Committee (TCTR20210104002) since 2021-04-01

Ethical consideration

This study was conducted as a randomized controlled trial. The study population was comprised of patients scheduled for elective INR procedures between 2022 and 2024. Prior to the initiation of the study, ethical approval was obtained from the Center for Ethics in Human Research.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board (Centre for Ethics in Human Research of Khon Kaen University, Thailand) approved this study (registration number: HE631514). All participants provided informed consent in order to participate and were informed about the study’s objectives before completing the questionnaire. We, as authors, do hereby confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Availability of data and material

The data and materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors had no competing interests.

Prior Presentation

Part of this study was previously presented as E-poster presentation at the Asian Australasian Congress of Anaesthesiologists (AACA) 2022 in conjunction with the 99th Annual Meeting of The Korean Society of Anesthesiologists (KSA) and the 74th Annual Meeting for The Korean Pain Society (KPS). The oral presentation was presented under the title, Effects of Sevoflurane versus Total Intravenous Anesthesia on Emergence Agitation after Interventional Neuroradiology: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: All authors Formal Analysis: P.K.,C.K.,N.P. Funding Acquisition: -Methodology: All authors; Visualization: All authors;Writing – Original Draft Preparation: C.K., P.K., N.P. Writing – Review & Editing: All authors

Funding

The study received funding support from a Faculty of Medicine Research Grant from Khon Kaen University (Invitation Research). (Number HE631514).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the nursing and surgical staff members, who assisted with patient care and data collection.

References

- Joung, K.W.; Yang, K.H.; Shin, W.J.; Song, M.H.; Ham, K.; Jung, S.C.; Lee, D.H.; Suh, D.C. Anesthetic Consideration for Neurointerventional Procedures. Neurointervention 2014, 9, 72–77. [CrossRef]

- Jo JY, Kim YH, Lee YS, Choi YS, Kim MS, Park SW, et al. Effect of total intravenous anesthesia vs volatile induction with maintenance anesthesia on emergence agitation after nasal surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(2):117-23. [CrossRef]

- Munk, L.; Andersen, G.; Møller, A.M. Post-anaesthetic emergence delirium in adults: incidence, predictors and consequences. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2016, 60, 1059–1066. [CrossRef]

- Choi ES, Shin JY, Oh AY, Kim YH, Park YC, Jung YS, et al. Sevoflurane versus propofol for interventional neuroradiology: a comparison of the maintenance and recovery profiles at comparable depths of anesthesia. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2014;66(4):290-4. [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.; Lee, K.H.; Park, J.-H. Comparison of Two Methods of Anesthesia Using Patient State Index: Propofol Versus Sevoflurane During Interventional Neuroradiology Procedure. Anesthesiol. Pain Med. 2019, In Press, e87518. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Song, B.; Koo, B. Efficacy of intraoperative dexmedetomidine infusion on emergence agitation and quality of recovery after nasal surgery. Br. J. Anaesth. 2013, 111, 222–228. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Chai, W.; Sun, X.; Yao, L. Emergence agitation in adults: risk factors in 2,000 patients. Can. J. Anaesth. 2010, 57, 843–848. [CrossRef]

- Lepousé, C.; Lautner, C.A.; Liu, L.; Gomis, P.; Leon, A. Emergence delirium in adults in the post-anaesthesia care unit. Br. J. Anaesth. 2006, 96, 747–753. [CrossRef]

- Miller D, Lewis SR, Pritchard MW, Guay J, Schofield-Robinson OJ, Alderson P, et al. Intravenous versus inhalational maintenance of anaesthesia for postoperative cognitive outcomes in elderly people undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;(8):CD012317.

- Jo JY, Kim YH, Lee YS, Choi YS, Kim MS, Park SW, et al. Effect of total intravenous anesthesia vs volatile induction with maintenance anesthesia on emergence agitation after nasal surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(2):117-23.

- Card E, Pandharipande P. Emergence delirium and emergence agitation in adults. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017;30(5):565-70.

- Yu, D.; Chai, W.; Sun, X.; Yao, L. Emergence agitation in adults: risk factors in 2,000 patients. Can. J. Anaesth. 2010, 57, 843–848. [CrossRef]

- Vlajkovic GP, Sindjelic RP. Emergence agitation in adults: a review of the literature. J Anesth Clin Res. 2015;6(11):579.

- Punjasawadwong, Y.; Phongchiewboon, A.; Bunchungmongkol, N. Bispectral index for improving anaesthetic delivery and postoperative recovery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD003843. [CrossRef]

- Castagnin A, Carli F, Fiasconaro M. Propofol versus sevoflurane: a comparison of recovery profiles and patient satisfaction in minimally invasive surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2018;47:56-61.

- Talke PO, Sharma D. Anesthesia for interventional neuroradiology. Anesthesiol Clin. 2020;38(2):297-311.

- De Hert S, Moerman A. Sevoflurane. In: Hemmings HC, Egan TD, editors. Pharmacology and physiology for anesthesia. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2015. p. 203-16.

- Ebert TJ. Propofol: hemodynamic effects. In: Coté CJ, Lerman J, Anderson BJ, editors. A practice of anesthesia for infants and children. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016. p. 225-30.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).