Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Anesthetics and Surgery

3.1. Statical Analyses

4. Results

| ID | Species | Weight (kg) | Gender | Age (years) | Procedure | TIVA/PIVA | Anesthesia’s duration (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal 1 | Macaca mulatta | 9 | F | 6 | spinal cord injury | propofol – fentanyl | 350 |

| tracer injection and bilateral craniotomy | propofol – fentanyl-0.4MACsevo | 195 | |||||

| Animal 2 | Macaca mulatta | 7.5 | F | 8 | ECoG implantation | propofol - remifentanil | 220 |

| Animal 3 | Macaca mulatta | 7 | M | 8 | headpost implantation | propofol - fentanyl | 295 |

| chamber implantation | propofol - remifentanil | 260 | |||||

| Animal 4 | Macaca mulatta | 8.2 | M | 8 | headpost implantation | propofol – fentanyl-0.4MACsevo | 390 |

| chamber implantation | propofol - remifentanil | 295 | |||||

| Animal 5 | Macaca fascicularis | 7 | F | 6 | stroke | propofol - fentanyl | 220 |

| RB-induced stroke | propofol - remifentanil | 130 | |||||

| Stroke + ANCE biopsy + Mapping and Imaging | propofol - remifentanil | 220 | |||||

| Animal 6 | Macaca fascicularis | 3.5 | F | 6 | headpost implantation | propofol - remifentanil | 145 |

| Animal 7 | Macaca fascicularis | 4.2 | F | 5 | headpost implantation | propofol - fentanyl | 95 |

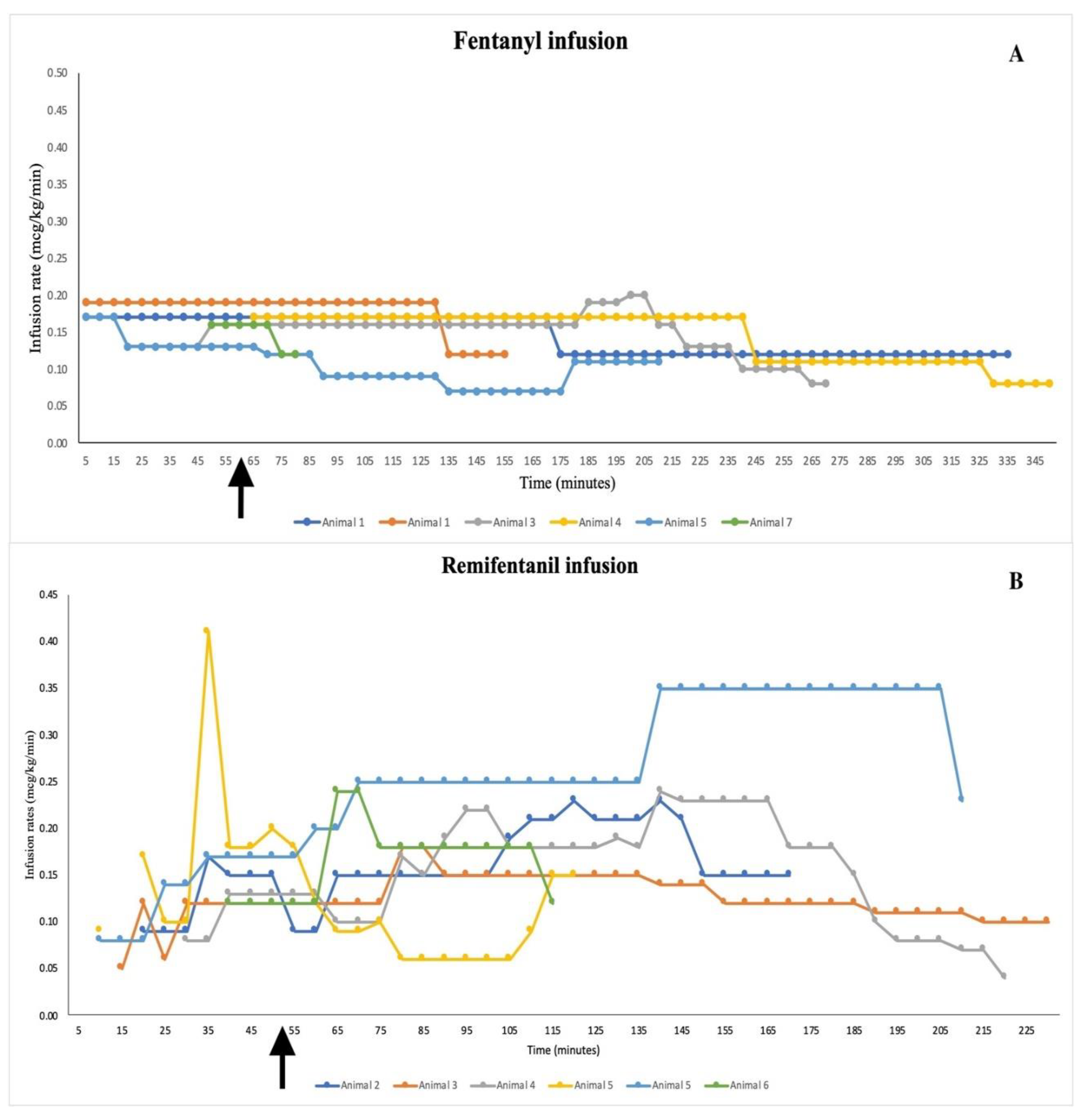

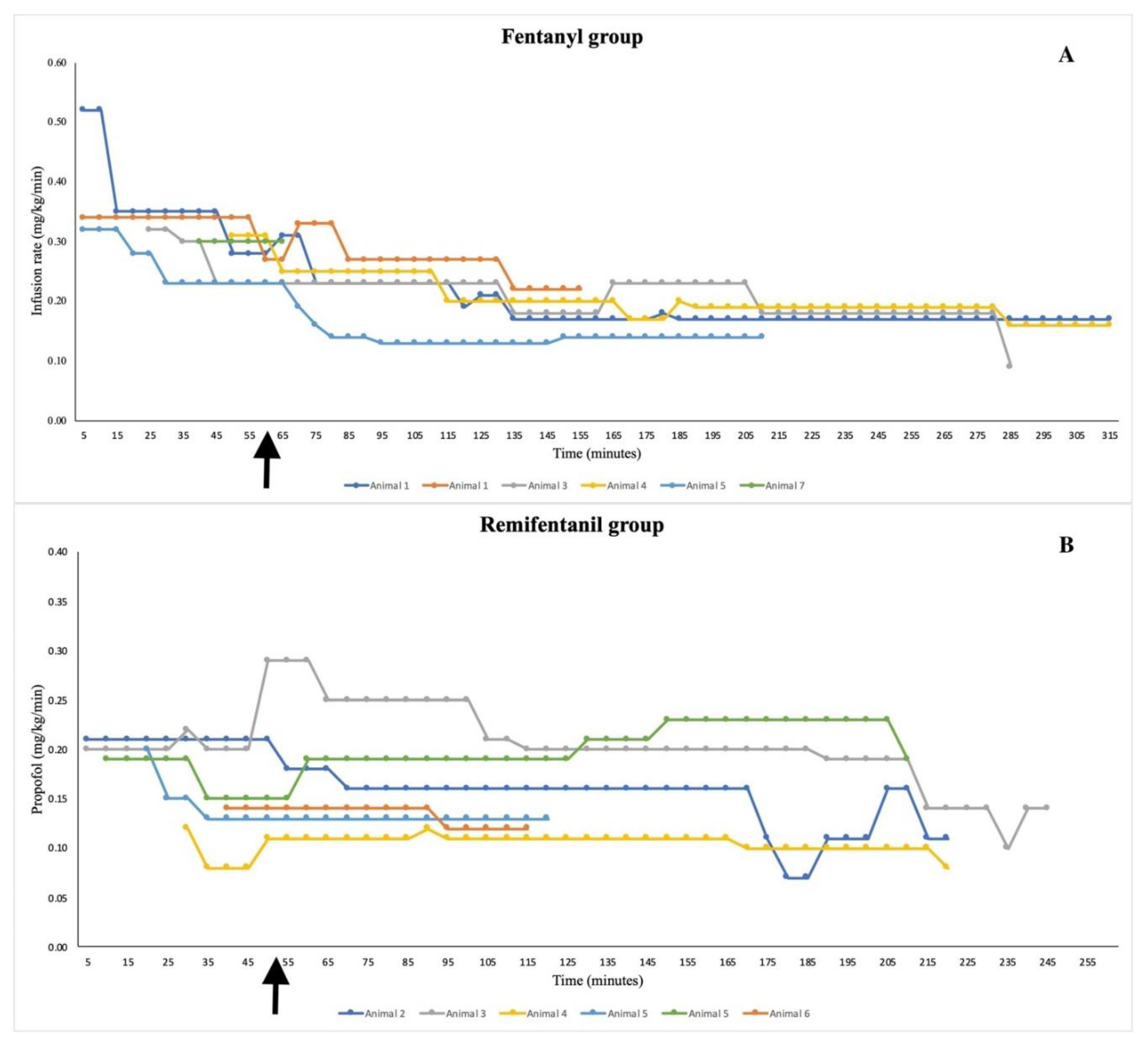

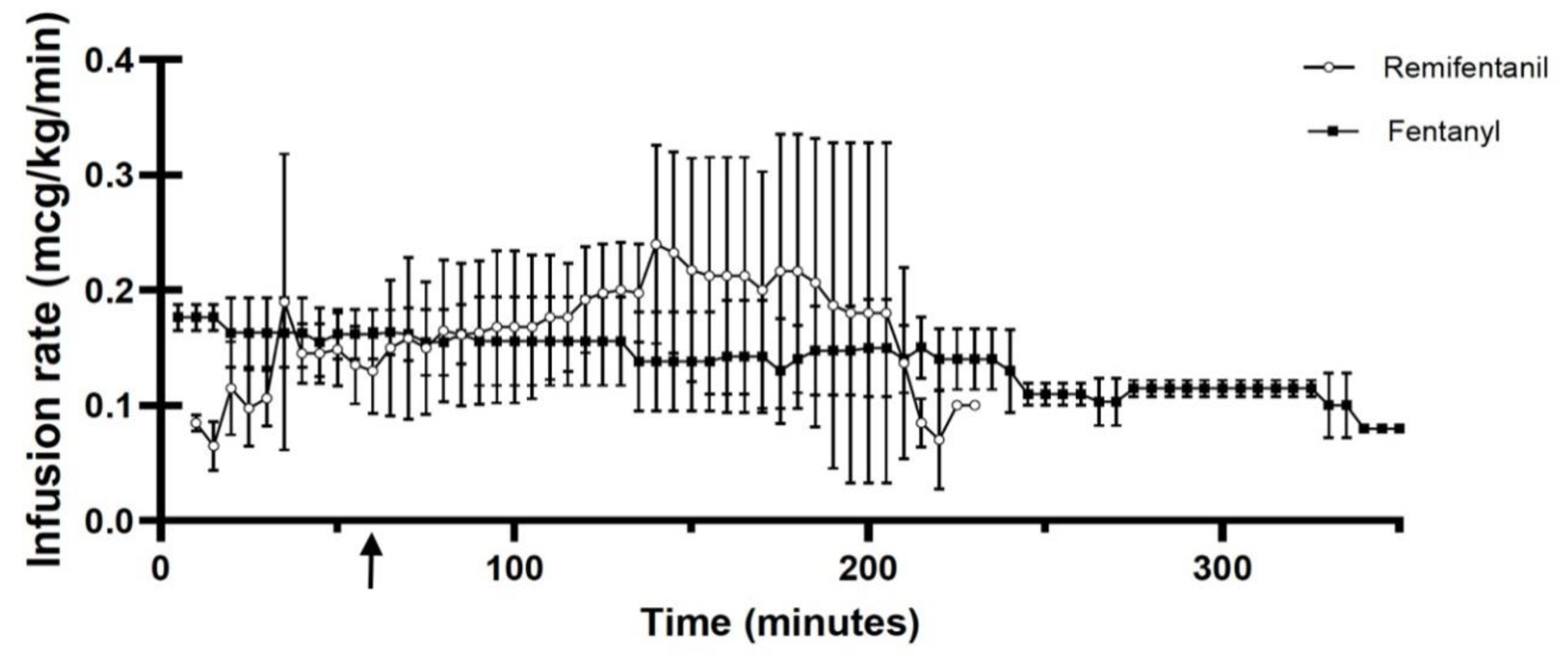

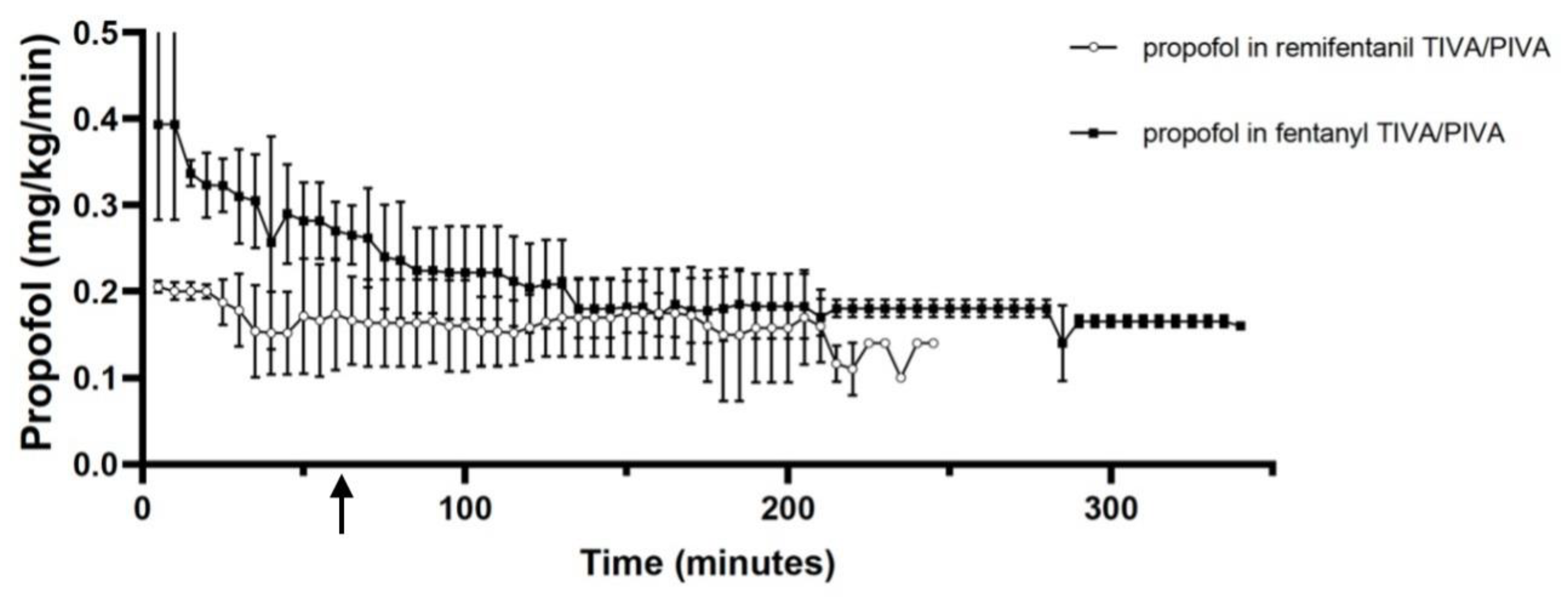

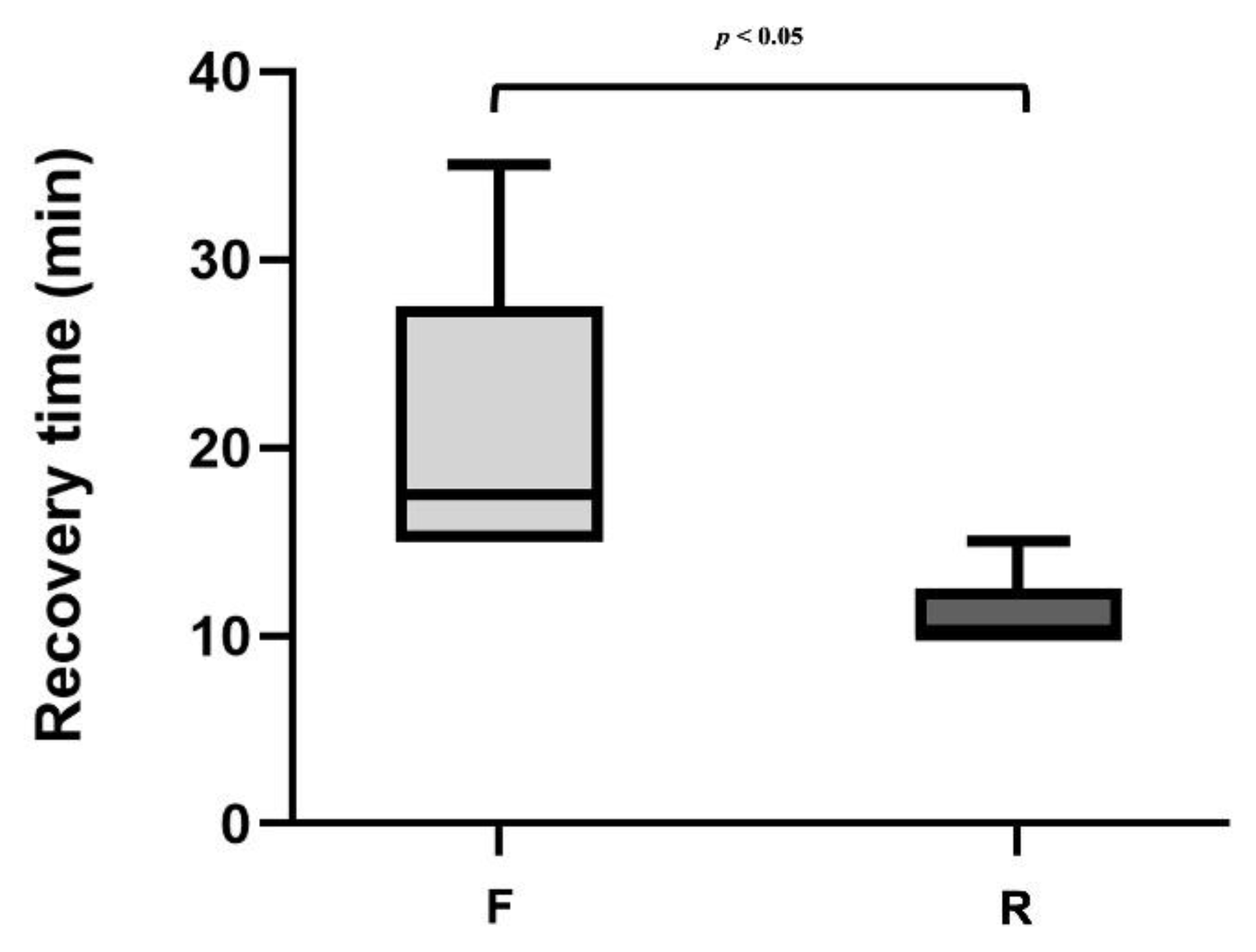

4.1. Group F:

4.2. Group R:

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Kaisti, K.K.; Metsähonkala, L.; Teräs, M.; Oikonen, V.; Aalto, S.; Jääskeläinen, S.; Hinkka, S.; Scheinin, H. Effects of Surgical Levels of Propofol and Sevoflurane Anesthesia on Cerebral Blood Flow in Healthy Subjects Studied with Positron Emission Tomography. Anesthesiology 2002, 96, 1358–1370. [CrossRef]

- Matta, B.F.; Heath, K.J.; Tipping, K.; Summors, A.C. Direct Cerebral Vasodilatory Effects of Sevoflurane and Isoflurane. Anesthesiology 1999, 91, 677–677. [CrossRef]

- Enlund, M.; Andersson, J.; Hartvig, P.; Valtysson, J.; Wiklund, L. Cerebral Normoxia in the Rhesus Monkey during Isoflurane- or Propofol- Induced Hypotension and Hypocapnia, despite Disparate Blood-Flow Patterns. A Positron Emission Tomography Study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1997, 41, 1002–1010. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.C.; Bai, S.J.; Lee, K.Y.; Shin, S.; Choi, E.K.; Lee, J.W. Total Intravenous Anesthesia with Propofol Reduces Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting in Patients Undergoing Robot-Assisted Laparoscopic Radical Prostatectomy: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Yonsei Med J 2012, 53, 1197–1202. [CrossRef]

- Varughese, S.; Ahmed, R. Environmental and Occupational Considerations of Anesthesia: A Narrative Review and Update. Anesth Analg 2021, 133, 826–835. [CrossRef]

- Nussmeier, N.A.; Benthuysen, J.L.; Steffey, E.P.; Anderson, J.H.; Carstens, E.E.; Eisele, J.H.; Stanley, T.H. Cardiovascular, Respiratory, and Analgesic Effects of Fentanyl in Unanesthetized Rhesus Monkeys. Anesth Analg 1991, 72, 221–226. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. V.; Hirano, Y.; Nascimento, G.C.; Stefanovic, B.; Leopold, D.A.; Silva, A.C. FMRI in the Awake Marmoset: Somatosensory-Evoked Responses, Functional Connectivity, and Comparison with Propofol Anesthesia. Neuroimage 2013, 78, 186–195. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, H.; Eydi, M.; Ghaffarlou, M.; Ghabili, K.; Golzari, S.E.; Bazzazi, A.M. Administration of Remifentanil in Establishing a More Stable Post-Anesthesia Cardiovascular Status in Neurosurgical Procedures. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res 2012, 4, 21–24. [CrossRef]

- Maurtua, M.A.; Deogaonkar, A.; Bakri, M.H.; Mascha, E.; Na, J.; Foss, J.; Sessler, D.I.; Lotto, M.; Ebrahim, Z.; Schubert, A. Dosing of Remifentanil to Prevent Movement During Craniotomy in the Absence of Neuromuscular Blockade. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2008, 20, 221–225. [CrossRef]

- Sakles, J.C.; Chiu, S.; Mosier, J.; Walker, C.; Stolz, U. The Importance of First Pass Success When Performing Orotracheal Intubation in the Emergency Department. Academic Emergency Medicine 2013, 20, 71–78. [CrossRef]

- Soma, L.R.; Tierney, W.J.; Hogan, G.K.; Satoh, N. The Effects of Multiple Administrations of Sevoflurane to Cynomolgus Monkeys: Clinical Pathologic, Hematologic, and Pathologic Study; 1995.

- Scott, L.J.; Perry, C.M. Remifentanil: A Review of Its Use during the Induction and Maintenance of General Anaesthesia. Drugs 2005, 65, 1793–1823. [CrossRef]

- Lauzuers, H.; Camu, F.; Vanlersberghe, C. Opioid What Advantages Does It Offer in Analgesia and Anaesthesia?

- Burkle, H.; Dunbar, S.; Van Aken, H. Remifentanil. Anesth Analg 1996, 83, 646–651. [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.P.; Thompson, J.P.; Leslie, N.A.; Fox, A.J.; Kumar, N.; Rowbotham, D.J. Comparison of Different Doses of Remifentanil on the Cardiovascular Response to Laryngoscopy and Tracheal Intubation. Br J Anaesth 2000, 84, 100–102. [CrossRef]

- Sneyd, J.R.; Camu, F.; Doenicke, A.; Mann, C.; Holgersen, O.; Helmers, J.H.J.H.; Appelgren, L.; Noronha, D.; Upadhyaya, B.K. Remifentanil and Fentanyl during Anaesthesia for Major Abdominal and Gynaecological Surgery. An Open, Comparative Study of Safety and Efficacy. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2001, 18, 605–614. [CrossRef]

- Heard, C.M.B.; Fletcher, J.E. Sedation and Analgesia. In Pediatric Critical Care; Elsevier, 2011; pp. 1654–1681.

- Machado, M.L.; Soares, J.H.N.; Kuster de Albuquerque Gress, M.A.; dos Santos e Castro, D.; Teodoro Rosa, K.; Bauer de Araujo Doria, P.; Otero Ascoli, F. Dose-Finding Study Comparing Three Treatments of Remifentanil in Cats Anesthetized with Isoflurane Undergoing Ovariohysterectomy. J Feline Med Surg 2018, 20, 164–171. [CrossRef]

- Gimenes, A.M.; De Araujo Aguiar, A.J.; Perri, S.H.V.; De Paula Nogueira, G. Effect of Intravenous Propofol and Remifentanil on Heart Rate, Blood Pressure and Nociceptive Response in Acepromazine Premedicated Dogs. Vet Anaesth Analg 2011, 38, 54–62. [CrossRef]

- Nunamaker, E.; Malinowski, C.; Godrooe, A.; Guerriero, K.; Burns, M. Anesthesia and Analgesia in Non Human Primates - Chapter 18. In Anesthesia and Analgesia in Laboratory Animals; Dyson, M.C., Jirkof, P., Lofgren, J., Nunamaker, E.A., Pang, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, 2023; pp. 441–479 ISBN 9780128222157.

- Kops, M.S.; Pesic, M.; Petersen, K.U.; Schmalix, W.A.; Stöhr, T. Impact of Concurrent Remifentanil on the Sedative Effects of Remimazolam, Midazolam and Propofol in Cynomolgus Monkeys. Eur J Pharmacol 2021, 890. [CrossRef]

- Young, S.S.; Schilling, A.M.; Skeans, S.; Ritacco, G. Short Duration Anaesthesia with Medetomidine and Ketamine in Cynomolgus Monkeys. Lab Anim 1999, 33, 162–168. [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, R.D.; Kass, P.H.; Sammak, R.L. Blood Pressure Reference Intervals for Ketamine-Sedated Rhesus Macaques (Macaca Mulatta). J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 2020, 59, 24–29. [CrossRef]

- Ko, B.J.; Oh, J.N.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, S.R.; Lee, S.C.; Chung, C.J. Comparison of Effects of Fentanyl and Remifentanil on Hemodynamic Response to Endotracheal Intubation and Myoclonus in Elderly Patients with Etomidate Induction. Korean J Anesthesiol 2013, 64, 12–18. [CrossRef]

- Ebert, T.J.; Muzi, M.; Lopatka, C.W. Neurocirculatory Responses to Sevoflurane in Humans. Anesthesiology 1995, 88–95. [CrossRef]

- Del Gaudio, A.; Ciritella, P.; Perrotta, F.; Puopolo, M.; Lauta, E.; Mastronardi, P.; De Vivo, P. Remifentanil vs Fentanyl with a Target Controlled Propofol Infusion in Patients Undergoing Craniotomy for Supratentorial Lesions. Minerva Anestesiol 2006, 72, 309–319.

- Fowler, K.A.; Huerkamp, M.J.; Pullium, J.K.; Subramanian, T. Anesthetic Protocol: Propofol Use in Rhesus Macaques (Macaca Mulatta) during Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Stereotactic Head Frame Application. Brain Research Protocols 2001, 7, 87–93. [CrossRef]

- Benveniste, H.; Fowler, J.S.; Rooney, W.D.; Moller, D.H.; Walter Backus, W.; Warner, D.A.; Carter, P.; King, P.; Scharf, B.; Alexoff, D.A.; et al. Maternal-Fetal In Vivo Imaging: A Combined PET and MRI Study; 2003; Vol. 44;

- Gao, W. wei; He, Y. hong; Liu, L.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, Y. feng; Zhao, B. BIS Monitoring on Intraoperative Awareness: A Meta-Analysis. Curr Med Sci 2018, 38, 349–353. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, L.; Ma, Y.Q.; Sun, Y.X.; Li, Y.H.; Zhang, L.; Feng, C.S.; Luo, B.; Zhao, Z.L.; Guo, J.R.; et al. Bispectral Index Monitoring Prevent Awareness during Total Intravenous Anesthesia: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blinded, Multi-Center Controlled Trial. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011, 124, 3664–3669. [CrossRef]

- Myles, P.S.; Leslie, K.; McNeil, J.; Forbes, A.; Chan, M.T.V. Bispectral Index Monitoring to Prevent Awareness during Anaesthesia: The B-Aware Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2004, 363, 1757–1763. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.R.D.; Bernardo, W.M.; Nunes, V.M. Benefit of General Anesthesia Monitored by Bispectral Index Compared with Monitoring Guided Only by Clinical Parameters. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology (English Edition) 2017, 67, 72–84. [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, M.; Spadavecchia, C.; Wanderer, S.; Boillat, G.; Marbacher, S.; García Casalta, L.G.; Casoni, D. Usefulness and Reliability of the Bispectral Index during Balanced Anesthesia for Neurovascular Surgery in New Zealand White Rabbits. Brain Sci 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Shribman, A.J.; Smith, G.; Achola, K.J. Cardiovascular and Catecholamine Responses to Laryngoscopy with and without Tracheal Intubation. Br J Anaesth 1987, 59, 295–299. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, J.; Anand, T.; Kamra, S.K. Hemodynamic Response to Endotracheal Intubation Using C-Trach Assembly and Direct Laryngoscopy. Saudi J Anaesth 2015, 9, 343–347. [CrossRef]

- Albertin, A.; Casati, A.; Deni, F.; Danelli, G.; Comotti, L.; Grifoni, F.; Fanelli, G.; San Raffaele, I.H. Clinical Comparison of Either Small Doses of Fentanyl or Remifentanil for Blunting Cardiovascular Changes Induced by Tracheal Intubation. Minerva Anestesiol 2000, 66, 691–696.

- Leone, M.; Rousseau, S.; Avidan, M.; Delmas, A.; Viviand, X.; Guyot, L.; Martin, C. Target Concentrations of Remifentanil with Propofol to Blunt Coughing during Intubation, Cuff Inflation, and Tracheal Suctioning. Br J Anaesth 2004, 93, 660–663. [CrossRef]

- Muellejans, B.; López, A.; Cross, M.H.; Bonome, C.; Morrison, L.; Kirkham, A.J.T. Remifentanil versus Fentanyl for Analgesia Based Sedation to Provide Patient Comfort in the Intensive Care Unit: A Randomized, Double-Blind Controlled Trial. Crit Care 2004, 8, R1–R11. [CrossRef]

- Poliquin, P.G.; Biondi, M.; Ranadheera, C.; Hagan, M.; Bello, A.; Racine, T.; Allan, M.; Funk, D.; Hansen, G.; Hancock, B.; et al. Delivering Prolonged Intensive Care to a Non-Human Primate: A High Fidelity Animal Model of Critical Illness. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [CrossRef]

- Wimalasena, Y.; Burns, B.; Reid, C.; Ware, S.; Habig, K. Apneic Oxygenation Was Associated with Decreased Desaturation Rates during Rapid Sequence Intubation by an Australian Helicopter Emergency Medicine Service. Ann Emerg Med 2015, 65, 371–376. [CrossRef]

- Riyapan, S.; Lubin, J. Apneic Oxygenation May Not Prevent Severe Hypoxemia During Rapid Sequence Intubation: A Retrospective Helicopter Emergency Medical Service Study. Air Med J 2016, 35, 365–368. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Huang, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Xie, Y. Comparison of Intubation Conditions and Apnea Time after Anesthesia Induction with Propofol/Remifentanil Combined with or without Small Dose of Succinylcholine. Int J Clin Exp Med 2014, 7, 393–399.

- Breen, D.; Karabinis, A.; Malbrain, M.; Morais, R.; Albrecht, S.; Jarnvig, I.-L.; Parkinson, P.; Kirkham, A.J. Open Access Decreased Duration of Mechanical Ventilation When Comparing Analgesia-Based Sedation Using Remifentanil with Standard Hypnotic-Based Sedation for up to 10 Days in Intensive Care Unit Patients: A Randomised Trial. Crit Care 2005, 9, R200–R210. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Du, B.; Xi, X. Could Remifentanil Reduce Duration of Mechanical Ventilation in Comparison with Other Opioids for Mechanically Ventilated Patients? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care 2017, 21, 206. [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, J.R.; MacGuire, J.; Chang, S.; Dierks, E.; Roble, G.S. Assessment of Pre-Operative Maropitant Citrate Use in Macaque (Macaca Fasicularis & Macaca Mulatta) Neurosurgical Procedures. J Med Primatol 2018, 47, 178–184. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Fentanyl TIVA/PIVA | Remifentanil TIVA |

|---|---|---|

| HR (beats/min) | 118 ± 26 | 102 ± 11 |

| RR (breaths/min) | 22 ± 5 | 21 ± 4 |

| SAP (mmHg) | 104 ± 14 | 93 ± 8 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 67 ± 2 | 70 ± 8 |

| DAP (mmHg) | 51 ± 20 | 54 ± 10 |

| ETCO2 (mmHg) | 46 ± 5 | 38 ± 8 |

| SpO2 (%) | 96 ± 2 | 96 ± 1 |

| TV (ml/kg) | 7 ± 2 | 9 ± 1 |

| PIP (cm H2O) | 13 ± 2 | 15 ± 2 |

| T (°C) | 37 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 |

| Complication | Group F | Group R |

|---|---|---|

| Hypotension | 5/6 | 1/6 |

| Bradycardia | 0/6 | 1/6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).