Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Study Aims

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Ethical Approval and Consent

2.3. Study Design

2.3.1. Questionnaires

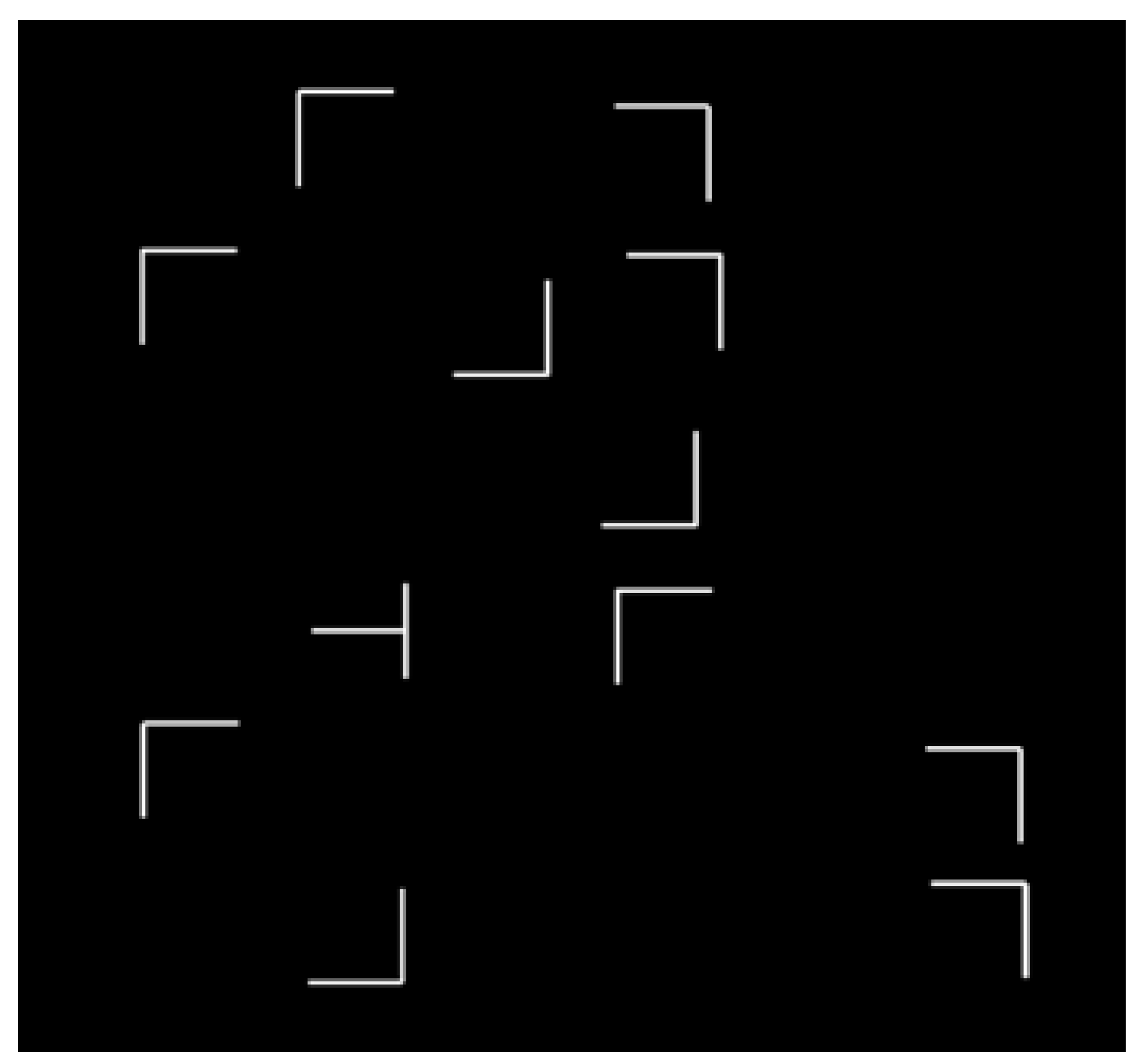

2.3.2. Visual Search Learning Task

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.1.1. Age

3.1.2. BMI and VO2max

3.1.3. Activity Ratings: Perceived Functional Ability (PFA), Physical Activity Rating (PA-R), and International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) Scores

3.1.4. Sleep-Related Scores: Stanford Sleepiness Scale and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

3.1.5. Competitiveness Scores

3.2. Task Performance

3.2.1. Baseline and Learning-Related Response Times

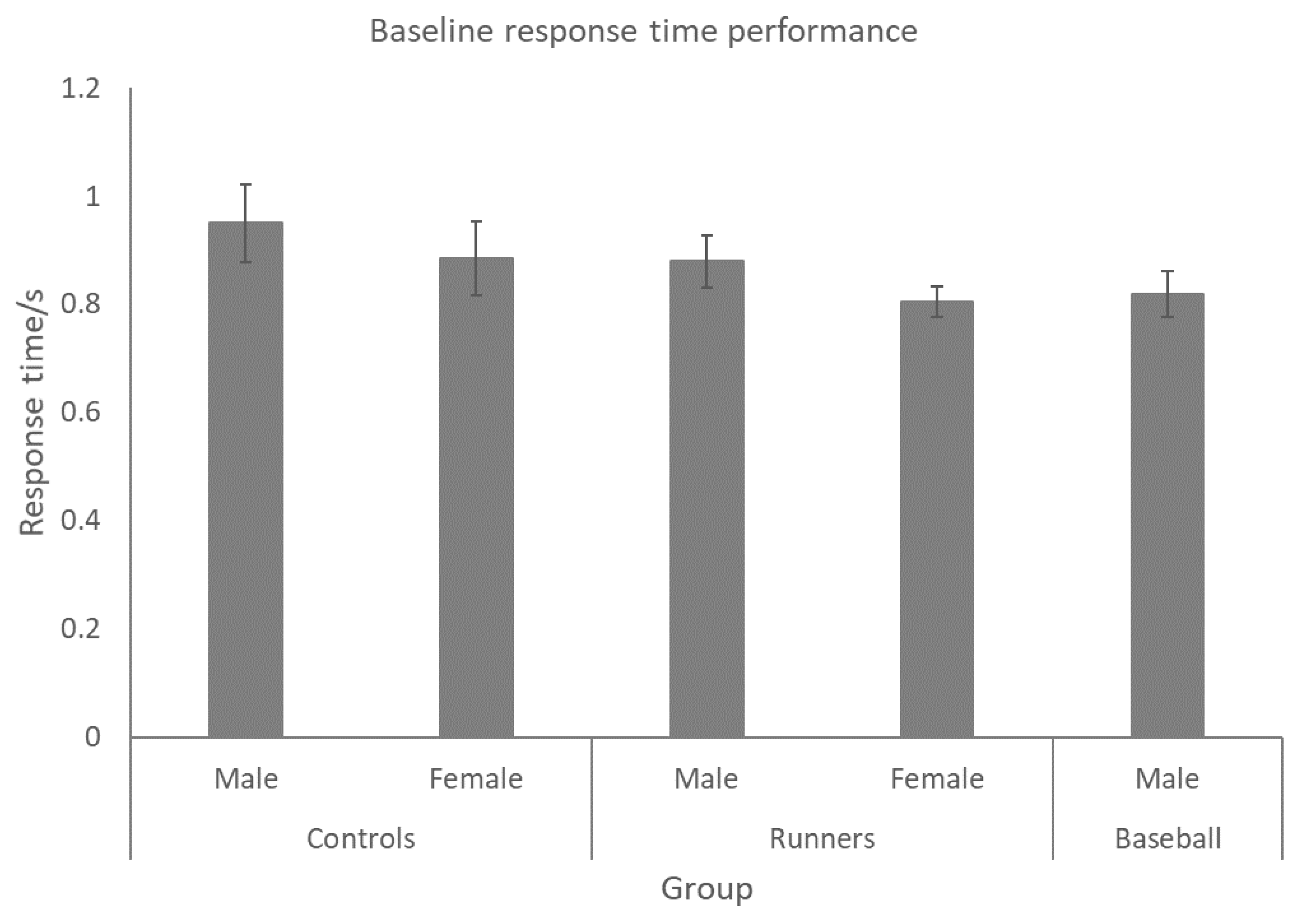

3.2.1.1. Overall Baseline Performance (Correct Response Times)

3.2.1.2. Baseline Performance with Factors of Sport and Gender

3.2.1.3. Baseline Performance with a Factor of Sport for Males

3.2.2. Task Learning

3.2.2.1. Performance Before and After Learning: Sport and Gender Effects

3.2.2.2. Performance Before and After Learning: Effects of Sport in Males

3.2.2.3. Summary of Baseline and Learning Response Time Analyses

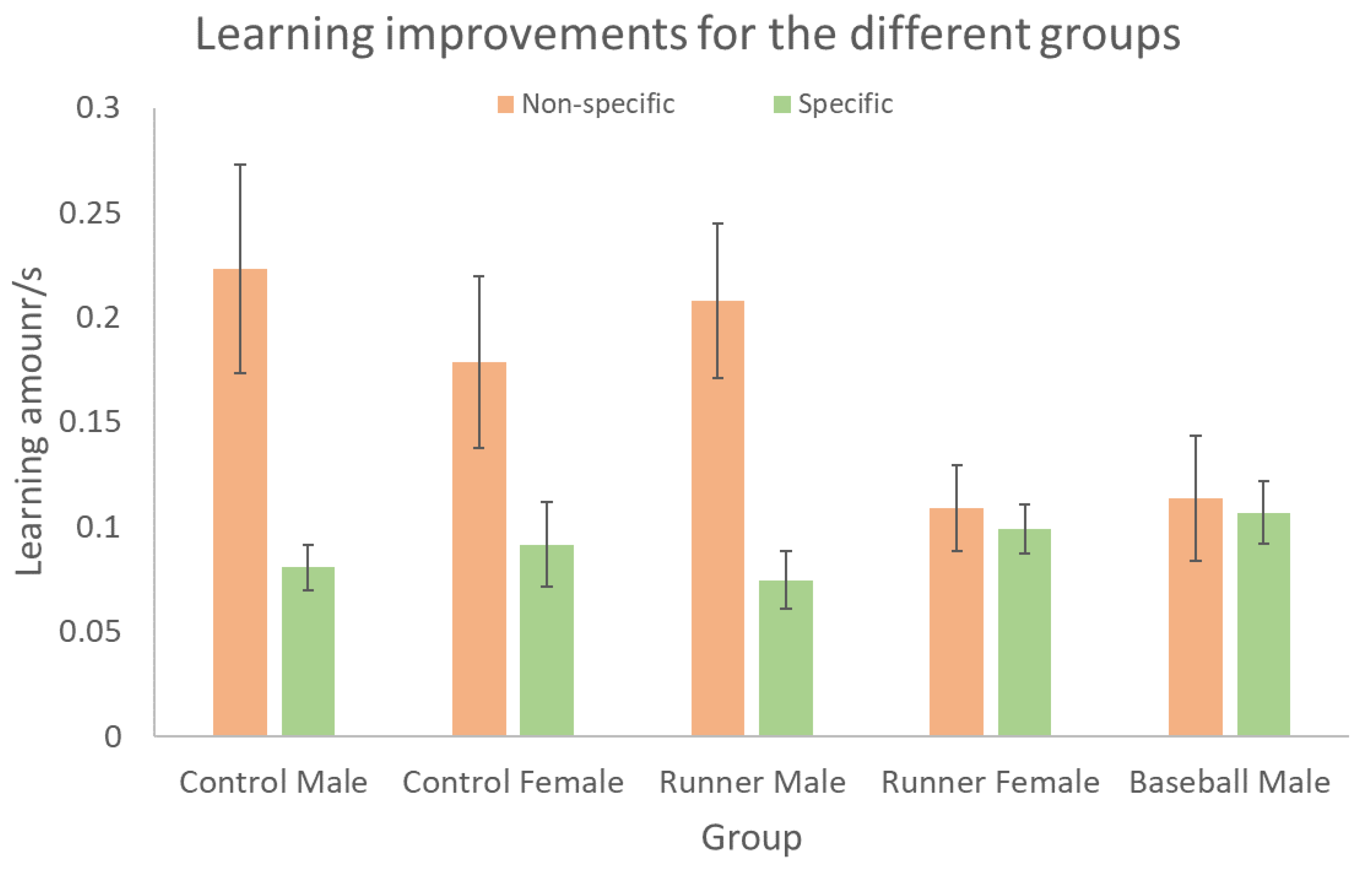

3.2.3. Analysis of Learning Types: Non-Specific and Specific Learning

3.2.3.1. Specific and Non-Specific Learning for Sport and Gender

3.2.3.2. Effects Associated with Sport on Specific and Non-Specific Learning in Males

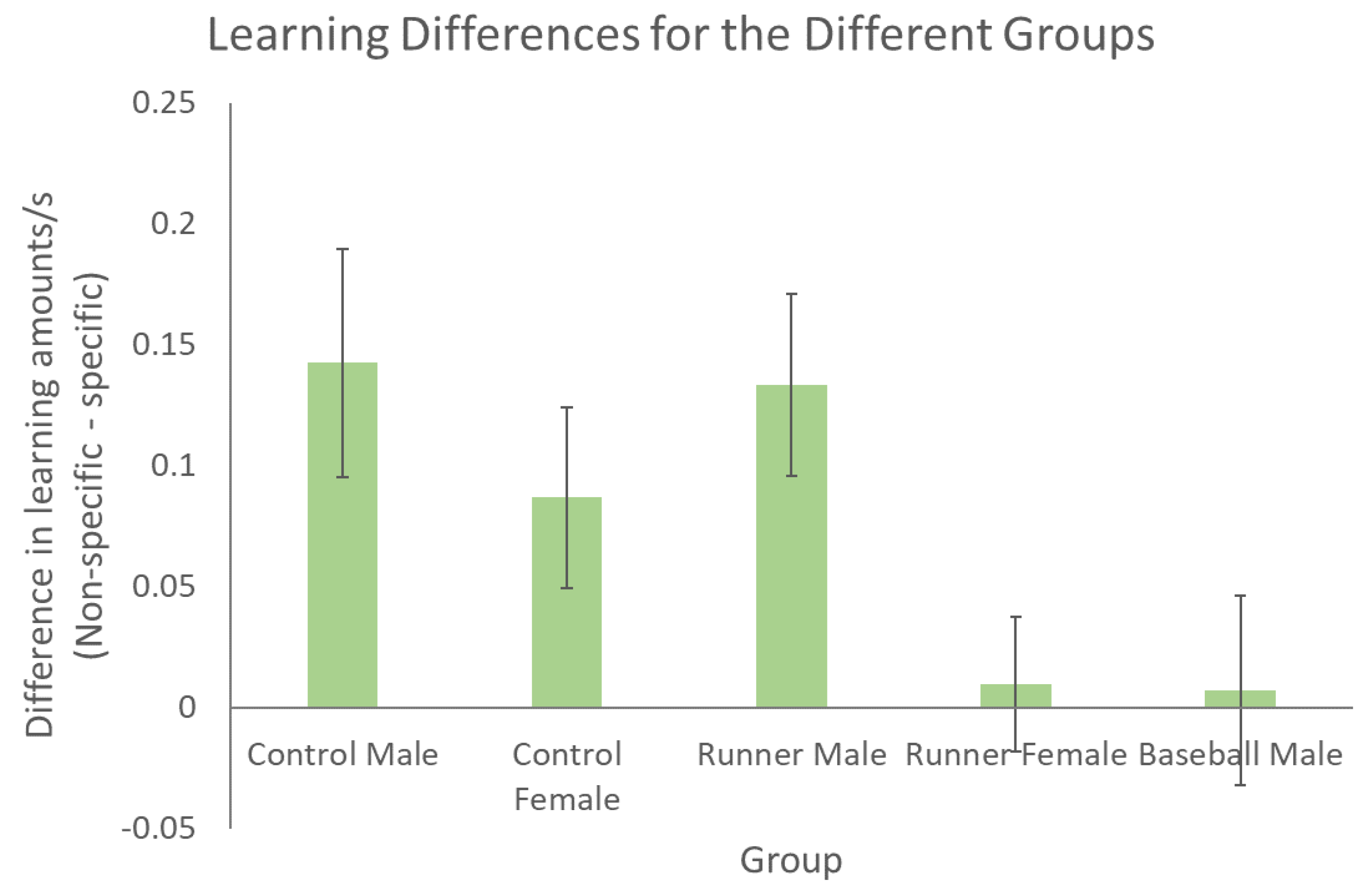

3.2.4. Analysis of Patterns of Learning: Differences Between Non-Specific and Specific Learning

3.2.4.1. Effects of Sport and Gender on Specific and Non-Specific Learning Differences

3.2.4.2. Effects of Sport on the Difference Between Learning Amounts for Male Participants

3.2.4.3. Patterns of Differences Summary

4. Discussion

- Sport/fitness training is not associate with improvement of learning of tasks (either motor or cognitive) in a non-specific manner.

- Sport/fitness training does seem to be associated with better levels of some aspects of task performance and these seem to be less specific, maybe having resulted either directly from sport training or as a consequence of better learning of these due to sport training.

- These effects were not seen here for all sporting individuals. This may mean the environment, context, nature, and social environment of training is important for any additional benefits, such as on cognition, to be seen.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Galloza J.; Castillo B.; Micheo W. Benefits of Exercise in the Older Population. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2017 Nov;28(4):659-669. [CrossRef]

- Spirduso, W.W.; Clifford, P. Replication of age and physical activity effects on reaction and movement time. J Gerontol. 1978, 33(1), 26-30. [CrossRef]

- Colcombe, S.; Kramer, A.F.. Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Sci. 2003, 14(2), 125-30. [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.M.; Mellow, M.L.; Smith, A.E.; Wan, L.; Gothe, N.P.; Fanning, J.; Jakicic, J.M.; Kang, C.; Grove, G.; Huang, H.; Oberlin, L.E.; Migueles, J.H.; Kamboh, M.I.; Kramer, A.F.; Hillman, C.H.; Vidoni, E.D.; Burns, J.M.; McAuley, E.; Erickson, K.I. 24-Hour time use and cognitive performance in late adulthood: results from the Investigating Gains in Neurocognition in an Intervention Trial of Exercise (IGNITE) study. Age Ageing. 2025, 54(4), afaf072. [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Hillman, C.H.; Castelli, D.; Etnier, J.L.; Lee, S.; Tomporowski, P.; Lambourne, K.; Szabo-Reed, A.N. Physical Activity, Fitness, Cognitive Function, and Academic Achievement in Children: A Systematic Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016, 48(6), 1197-222. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Chang, C.C.; Liang, Y.M.; Shih, C.M.; Muggleton, N.G.; Juan, C.H. Temporal preparation in athletes: a comparison of tennis players and swimmers with sedentary controls. J Mot Behav. 2013, 45(1), 55-63. [CrossRef]

- Stimpson, N.J.; Davison, G.; Javadi, A.-H. Joggin’ the noggin: towards a physiological understanding of exercise-induced cognitive benefits. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. [CrossRef]

- Kleim, J.A.; Cooper, N.R.; VandenBerg, P.M. Exercise induces angiogenesis but does not alter movement representations within rat motor cortex. Brain Res. 2003, 934, 1–6.

- Swain, R.A.; Harris, A.B.; Wiener, E.C.; Dutka, M.V.; Morris, H.D.; Theien, B.E. et al. Prolonged exercise induces angiogenesis and increases cerebral blood volume in primary motor cortex of the rat. Neuroscience 2003, 117, 1037–1046.

- Pereira, A.C.; Huddleston, D.E.; Brickman, A.M.; Sosunov, A.A.; Hen, R.; et al. An in vivo correlate of exercise-induced neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 5638–5643. [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, O.; Gauthier ,C.J.; Fraser, S.A.; Desjardins-Crèpeau, L.; Desjardins, M.; et al. Higher levels of cardiovascular fitness are associated with better executive function and prefrontal oxygenation in younger and older women. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 66. [CrossRef]

- Guchait, A.; Muggleton, N.G. Investigating mechanisms of sport-related cognitive improvement using measures of motor learning. Prog Brain Res. 2024, 283, 305-325. [CrossRef]

- Kunar, M.A.; John, R.; Sweetman, H. A configural dominant account of contextual cueing: Configural cues are stronger than colour cues. Q J Exp Psychol. 2014, 67(7), 1366-82. [CrossRef]

- Chun, M.M. Contextual cueing of visual attention. Trends in Cognitive Science, 2000, 4, 170–178.

- Jiang, Y.; Leung, A.W. Implicit learning of ignored visual context. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 2005, 12(1), 100–106.

- Kunar, M.A.; Flusberg, S.J.; Horowitz, T.S.; Wolfe, J.M. Does contextual cueing guide the deployment of attention? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 2007, 33,816–828.

- Peterson, M.S.; Beck, M.R.; Wong, J.H. Effects of executive functioning on visual search. Journal of Vision, 2006, 6(6),1106, 1106a. [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. Recommendations Guiding Medical Doctors in Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. Med. J. Aust. 1976, 1, 206–20.

- George, J.D.; Stone, W.J.; Burkett, L.N. Non-exercise VO2max estimation for physically active college students. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1997, 29(3), 415–423.

- Smither, R.D.; Houston, J.M., The nature of competitiveness: the development and validation of the competitiveness index. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1992, 52(2), 407–418. [CrossRef]

- MacLean, A.W.; Fekken, G.C.; Saskin, P.; Knowles, J.B., Psychometric evaluation of the Stanford Sleepiness Scale. J. Sleep Res. 1992, 1(1), 35–39. [CrossRef]

- Shahid, A.; Wilkinson, K.; Marcu, S.; Shapiro, C.M. Stanford sleepiness scale (SSS). In STOP, THAT and One Hundred Other Sleep Scales; Shahid, A.; Wilkinson, K.; Marcu, S.; Shapiro, C., Eds.; Springer, New York, NY. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; Oja, P. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35(8), 1381–1395. [CrossRef]

- Peirce, J.W.; Gray, J.R.; Simpson, S.; MacAskill, M.R.; Höchenberger, R.; Sogo, H.; Kastman, E.; Lindeløv, J. PsychoPy2: experiments in behavior made easy. Behavior Research Methods 2019, 10.3758/s13428-018-01193-y.

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159.

- McSween, M.P.; Coombes, J.S.; MacKay, C.P.; Rodriguez, A.D.; Erickson, K.I.; Copland, D.A.; McMahon, K.L. The Immediate Effects of Acute Aerobic Exercise on Cognition in Healthy Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2019, 49(1), 67-82. [CrossRef]

- Ellison, A.; Walsh, V. Perceptual learning in visual search: some evidence of specificities. Vision Res. 1998, 38(3), 333-45. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, C.T.; Muggleton, N.G. The effects of visual training on sports skill in volleyball players. Prog Brain Res. 2020, 253, 201-227. [CrossRef]

| Group Gender Number |

Control Male 12 |

Control Female 13 |

Runner Male 13 |

Runner Female 12 |

Baseball Male 13 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20.92 | 21.92 | 21.31 | 21.25 | 20.31 | |

| Weight(kg) | 69.15 | 52.11 | 68.38 | 52.42 | 65.82 | |

| Height(m) | 1.73 | 1.60 | 1.77 | 1.59 | 1.71 | |

| BMI | 23.11 | 20.26 | 21.80 | 20.78 | 22.50 | |

| VO2max (mL·kg-¹·min-¹) | 45.32 | 39.88 | 55.33 | 44.22 | 52.48 | |

| Perceived Functional Ability | PFA | 12.50 | 11.17 | 21.23 | 14.50 | 18.08 |

| Physical Activity Rating | PA-R | 2.42 | 2.67 | 7.00 | 5.83 | 6.38 |

| Revised Competitiveness Index | Enjoyment of Competition Scale | 30.08 | 26.92 | 35.92 | 32.67 | 30.54 |

| (CI-R) | Contentiousness Scale | 12.50 | 12.33 | 12.85 | 13.17 | 12.77 |

| Competitiveness | 42.58 | 39.25 | 48.77 | 45.83 | 43.31 | |

| Stanford Sleepiness Scale | Before Experiment | 2.17 | 2.08 | 1.77 | 1.92 | 2.15 |

| After Experiment | 2.08 | 2.75 | 1.92 | 1.75 | 2.77 | |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | Subjective sleep quality | 1.33 | 0.75 | 0.92 | 0.75 | 1.38 |

| Sleep latency | 1.17 | 1.25 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 1.31 | |

| Sleep duration | 0.92 | 0.67 | 0.92 | 0.50 | 0.92 | |

| Sleep efficiency | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.38 | |

| Sleep disturbance | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 1.08 | |

| Use of sleep medication | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 | |

| Daytime dysfunction | 1.00 | 1.33 | 0.77 | 0.92 | 1.15 | |

| Global PSQI Score | 5.75 | 5.08 | 4.69 | 4.33 | 6.23 | |

| IPAQ: Walking | Walking MET-min/week | 936.42 | 882.75 | 849.15 | 1077.75 | 845.38 |

| IPAQ: Moderate | Moderate MET-min/week | 653.33 | 516.67 | 1113.85 | 670.00 | 1347.69 |

| IPAQ: Vigorous | Vigorous MET-min/week | 386.67 | 486.67 | 2067.69 | 1806.67 | 2030.77 |

| Total | MET-min/week | 1976.42 | 1886.08 | 4030.69 | 3554.42 | 4223.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).