Submitted:

19 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Creating a Dataset of the Analyzed Ig-Like Proteins

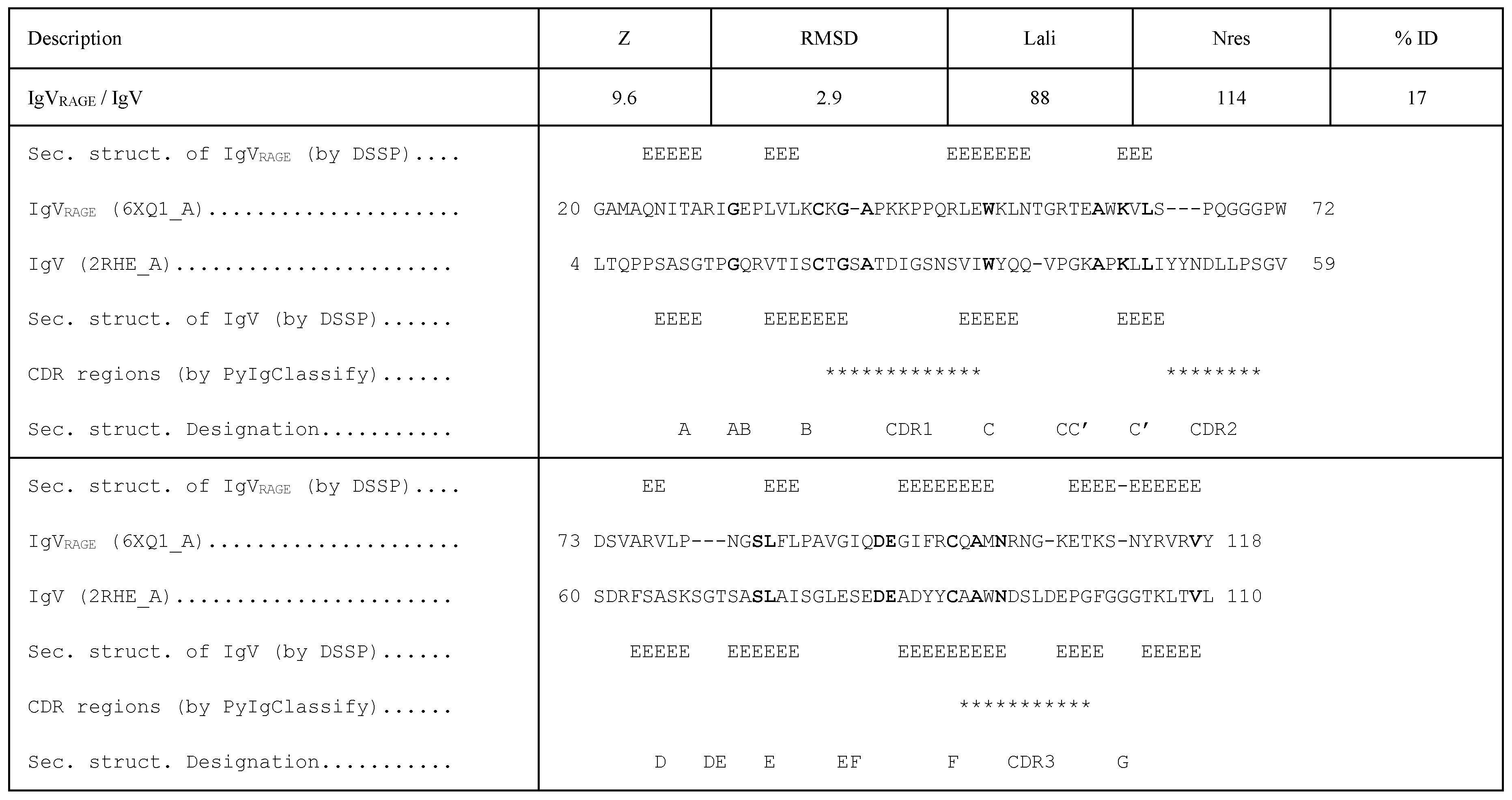

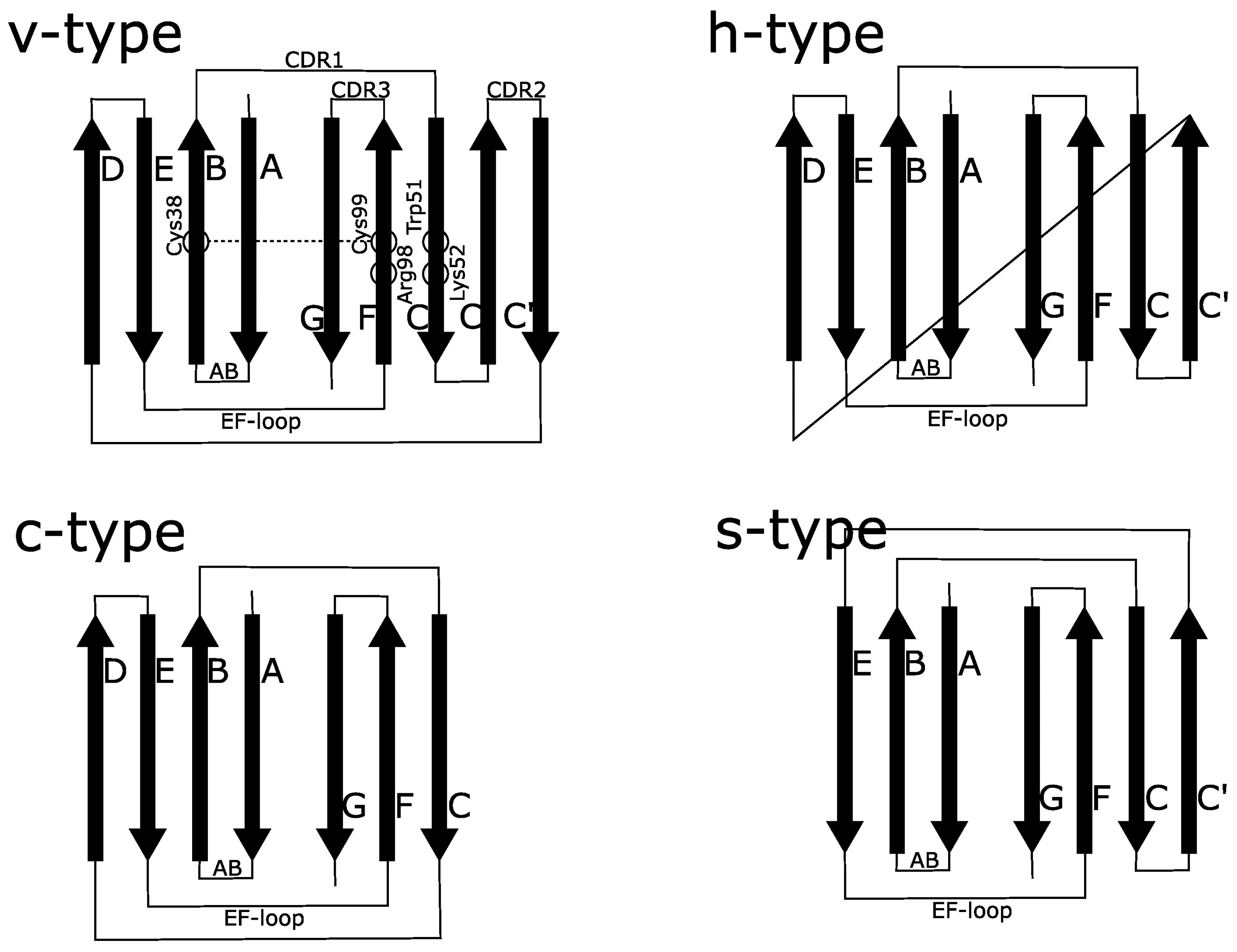

3.2. Structural Homology between IgVRAGE and IgV, and the Overall Topology of Ig-Like Domains

3.3. The Cross-β Zone of the IgVRAGE Domain

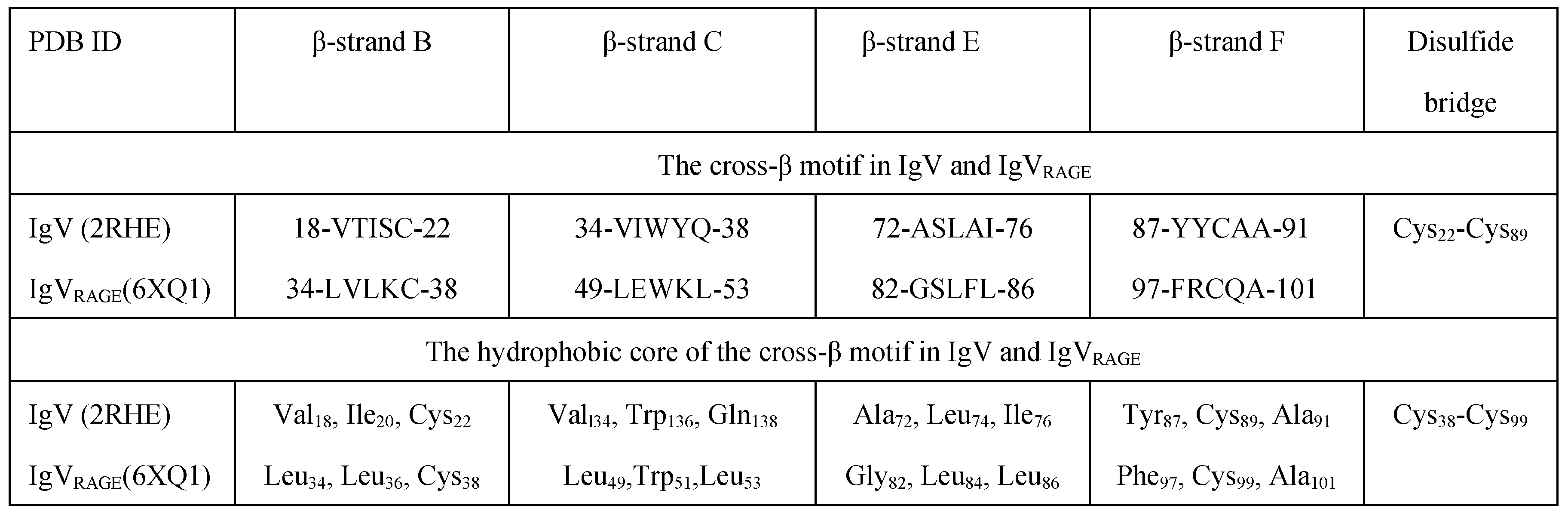

3.4. Hydrophobic Core of Ig-Like Structures

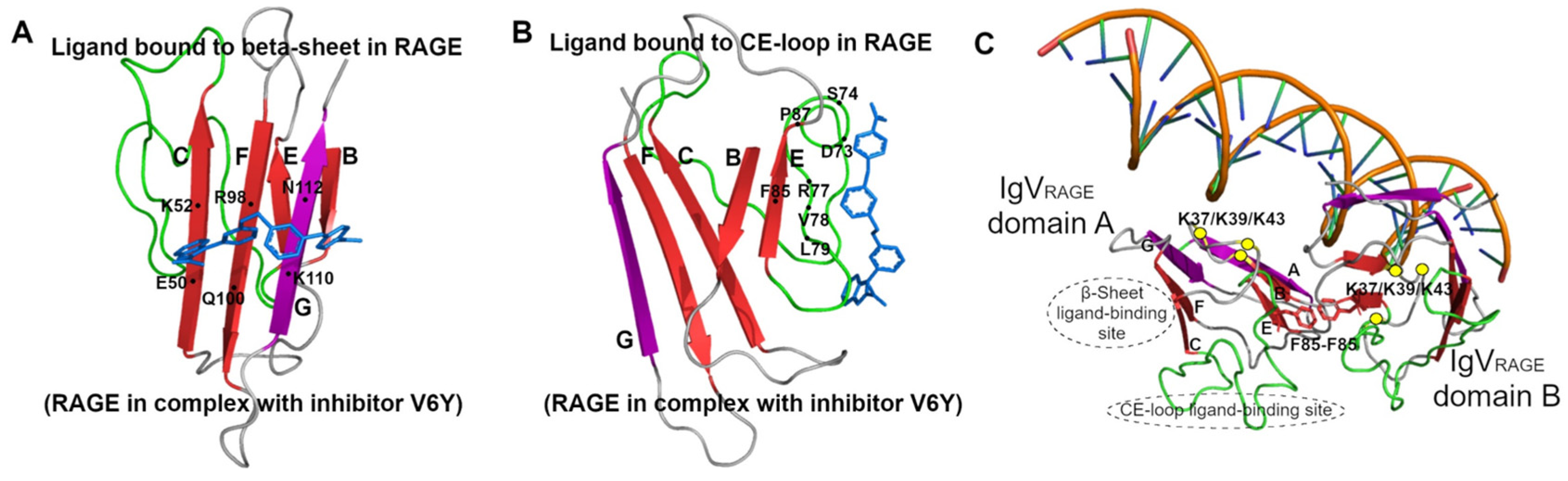

3.5. Two Types of Ligand Binding in RAGE

3.6. RAGE Dimerization and Binding of DNA

3.7. Antiparallel Homodimerization of Two β-Loop-β Fragments to Create Functional Core of RAGE

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dobrucki, I.T.,; Miskalis, A.,; Nelappana, M.,; Applegate, C.,; Wozniak, M.,; Czerwinski, A.,; Kalinowski, L.,; Dobrucki, L.W. Receptor for advanced glycation end-products: Biological significance and imaging applications. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 16, e1935. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.,; Adem, A. The dynamic roles of advanced glycation end products. Vitam. Horm. 2024, 125, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S. Pathological role of RAGE underlying progression of various diseases: its potential as biomarker and therapeutic target. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 3467–3487. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.,; Zhou, H.,; Zhang, W.,; Wang, T.,; Swamiappan, S.,; Peng, X.,; Zhou, Y. Effects of advanced glycation end products on stem cell. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1532614. [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.,; Vogl, T.,; Sorg, C.,; Sunderkötter, C. Phagocyte-specific S100 proteins: a novel group of proinflammatory molecules. Trends Immunol. 2003, 24, 155–158. [CrossRef]

- Delrue, C.,; Speeckaert, R.,; Delanghe, J.R.,; Speeckaert, M.M. Breath of fresh air: Investigating the link between AGEs, sRAGE, and lung diseases. Vitam. Horm. 2024, 125, 311–365. [CrossRef]

- Radziszewski, M.,; Galus, R.,; Łuszczyński, K.,; Winiarski, S.,; Wąsowski, D.,; Malejczyk, J.,; Włodarski, P.,; Ścieżyńska, A. The RAGE Pathway in Skin Pathology Development: A Comprehensive Review of Its Role and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13570. [CrossRef]

- Zglejc-Waszak, K.,; Jozwik, M.,; Thoene, M.,; Wojtkiewicz, J. Role of Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-Products in Endometrial Cancer: A Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 3192. [CrossRef]

- Coser, M.,; Neamtu, B. M.,; Pop, B.,; Cipaian, C. R.,; Crisan, M. RAGE and its ligands in breast cancer progression and metastasis. Oncol. Rev. 2025, 18, 1507942. [CrossRef]

- Sparvero, L.J.,; Asafu-Adjei, D.,; Kang, R.,; Tang, D.,; Amin, N.,; Im, J.,; Rutledge, R.,; Lin, B.,; Amoscato, A.A.,; Zeh, H.J.,; et al. RAGE (Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts), RAGE ligands, and their role in cancer and inflammation. J. Transl. Med. 2009, 7, 17. [CrossRef]

- Palanissami, G.,; Paul, S.F.D. RAGE and Its Ligands: Molecular Interplay Between Glycation, Inflammation, and Hallmarks of Cancer-a Review. Horm. Cancer. 2018, 9, 295–325. [CrossRef]

- Deepu, V.,; Rai, V.,; Agrawal, D.K. Quantitative Assessment of Intracellular Effectors and Cellular Response in RAGE Activation. Arch. Intern. Med. Res. 2024, 7, 80–103. [CrossRef]

- Paudel, Y.N.,; Angelopoulou, E.,; Piperi, C.,; Othman, I.,; Aamir, K.,; Shaikh, M.F. Impact of HMGB1, RAGE, and TLR4 in Alzheimer's Disease (AD): From Risk Factors to Therapeutic Targeting. Cells 2020, 9, 383. [CrossRef]

- Cross, K.,; Vetter, S.W.,; Alam, Y.,; Hasan, M.Z.,; Nath, A.D.,; Leclerc, E. Role of the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products (RAGE) and Its Ligands in Inflammatory Responses. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1550. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, C.T. Advanced Glycation End Products in Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2024, 74, 114. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.,; Chen, Q.,; Peng, C.,; Yang, D.,; Liu, S.,; Lv, Y.,; Jiang, L.,; Xu, S.,; Huang, L. Roles of the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products and Its Ligands in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer's Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 403. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.,; Wang, X.,; Lin, S.,; King, L.,; Liu, L. The Potential Role of Advanced Glycation End Products in the Development of Kidney Disease. Nutrients 2025, 17, 758. [CrossRef]

- Gąsiorowski, K.,; Brokos, B.,; Echeverria, V.,; Barreto, G.E.,; Leszek, J. RAGE-TLR Crosstalk Sustains Chronic Inflammation in Neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 1463–1476. [CrossRef]

- Jangde, N.,; Ray, R.,; Rai, V. RAGE and its ligands: from pathogenesis to therapeutics. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 55, 555–575. [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, K.,; Fukami, K. RAGE signaling regulates the progression of diabetic complications. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1128872. [CrossRef]

- Pedreañez, A.,; Mosquera-Sulbaran, J.A.,; Tene, D. Role of the receptor for advanced glycation end products in the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection in diabetic patients. Diabetol. Int. 2024, 15, 732–744. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.,; Jiang, T.,; Qi, Y.,; Luo, S.,; Xia, Y.,; Lang, B.,; Zhang, B.,; Zheng, S. AGE-RAGE Axis and Cardiovascular Diseases: Pathophysiologic Mechanisms and Prospects for Clinical Applications. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2024, 10.1007/s10557-024-07639-0. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Neeper, M.,; Schmidt, A.M.,; Brett, J.,; Yan, S.D.,; Wang, F.,; Pan, Y.C.,; Elliston, K.,; Stern, D.,; Shaw, A. Cloning and expression of a cell surface receptor for advanced glycosylation end products of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 14998–15004. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1378843/.

- Bork, P.,; Holm, L.,; Sander, C. The immunoglobulin fold. Structural classification, sequence patterns and common core. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 242, 309–320. [CrossRef]

- Harpaz, Y.,; Chothia, C. Many of the immunoglobulin superfamily domains in cell adhesion molecules and surface receptors belong to a new structural set which is close to that containing variable domains. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 238, 528–539. [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.,; Chitayat, S.,; Dattilo, B.M.,; Schiefner, A.,; Diez, J.,; Chazin, W. J.,; Fritz, G. Structural basis for ligand recognition and activation of RAGE. Structure 2010, 18, 1342–1352. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.,; Rai, V.,; Singer, D.,; Chabierski, S.,; Xie, J.,; Reverdatto, S.,; Burz, D.S.,; Schmidt, A.M.,; Hoffmann, R.,; Shekhtman, A. Advanced glycation end product recognition by the receptor for AGEs. Structure 2011, 19, 722–732. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, B.I.,; Lippman, M.E. Targeting RAGE Signaling in Inflammatory Disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 2018, 69, 349–364. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.,; Jeong, M.S.,; Jang, S.B. Molecular Characteristics of RAGE and Advances in Small-Molecule Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6904. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, B.I.,; Carter, A.M.,; Harja, E.,; Kalea, A.Z.,; Arriero, M.,; Yang, H.,; Grant, P.J.,; Schmidt, A.M. Identification, classification, and expression of RAGE gene splice variants. FASEB J. 2008, 22 1572–1580. [CrossRef]

- Bongarzone, S.,; Savickas, V.,; Luzi, F.,; Gee, A.D. Targeting the Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts (RAGE): A Medicinal Chemistry Perspective. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 7213–7232. [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.K.,; Leem, J.,; Deane, C.M. Comparative Analysis of the CDR Loops of Antigen Receptors. Front Immunol. 2019, 10, 2454. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.,; Reverdatto, S.,; Frolov, A.,; Hoffmann, R.,; Burz, D.S.,; Shekhtman, A. Structural basis for pattern recognition by the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 27255–27269. [CrossRef]

- Yatime, L.,; Andersen, G.R. Structural insights into the oligomerization mode of the human receptor for advanced glycation end-products. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 6556–6568. [CrossRef]

- Zong, H.,; Madden, A.,; Ward, M.,; Mooney, M.H.,; Elliott, C.T.,; Stitt, A.W. Homodimerization is essential for the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE)-mediated signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 23137–23146. [CrossRef]

- Sárkány, Z.,; Ikonen, T.P.,; Ferreira-da-Silva, F.,; Saraiva, M.J.,; Svergun, D.,; Damas, A.M. Solution structure of the soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE). J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 37525–37534. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.,; Burz, D.S.,; He, W.,; Bronstein, I.B.,; Lednev, I.,; Shekhtman, A. Hexameric calgranulin C (S100A12) binds to the receptor for advanced glycated end products (RAGE) using symmetric hydrophobic target-binding patches. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 4218–4231. [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.,; Lampe, L.,; Park, S.,; Vangara, B.S.,; Waldo, G.S.,; Cabantous, S.,; Subaran, S.S.,; Yang, D.,; Lakatta, E.G.,; Lin, L. Disulfide bonds within the C2 domain of RAGE play key roles in its dimerization and biogenesis. PLoS One 2012, 7, e50736. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, G. RAGE: a single receptor fits multiple ligands. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011, 36, 625–632. [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.T.T.,; Huynh, V.Q.,; Vo, N.T.,; Nguyen, H.D. Studying the characteristics of nanobody CDR regions based on sequence analysis in combination with 3D structures. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022, 20, 157. [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.,; Westbrook, J.,; Feng, Z.,; Gilliland, G.,; Bhat, T.N.,; Weissig, H.,; Shindyalov, I.N.,; Bourne, P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, R.A.,; Hutchinson, E.G.,; Michie, A.D.,; Wallace, A.C.,; Jones, M.L.,; Thornton, J.M. PDBsum: a Web-based database of summaries and analyses of all PDB structures. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1997, 22, 488–490. [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, A.,; Kulesha, E.,; Gough, J.,; Murzin, A.G. The SCOP database in 2020: expanded classification of representative family and superfamily domains of known protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D376–D382. [CrossRef]

- Blum, M.,; Andreeva, A.,; Florentino, L.C.,; Chuguransky, S.R.,; Grego, T.,; Hobbs, E.,; Pinto, B.L.,; Orr, A.,; Paysan-Lafosse, T.,; Ponamareva, I.,; et al. InterPro: the protein sequence classification resource in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D444–D456. [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, V.,; Sorokine, A.,; Prilusky, J.,; Abola, E.E.,; Edelman, M. Automated analysis of interatomic contacts in proteins. Bioinformatics 1999, 15, 327–332. [CrossRef]

- Holm, L.,; Sander, C. Dali: a network tool for protein structure comparison. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995, 20, 478–480. [CrossRef]

- Kelow, S.,; Faezov, B.,; Xu, Q.,; Parker, M.,; Adolf-Bryfogle, J.,; Dunbrack R.L. A penultimate classification of canonical antibody CDR conformations. bioRxiv 2022. [CrossRef]

- Derewenda, Z.S.,; Derewenda, U.,; Kobos, P.M. (His)C epsilon-H...O=C < hydrogen bond in the active sites of serine hydrolases. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 241, 83–93. [CrossRef]

- Kozlyuk, N.,; Gilston, B.A.,; Salay, L.E.,; Gogliotti, R.D.,; Christov, P.P.,; Kim, K.,; Ovee, M.,; Waterson, A.G.,; Chazin, W.J. A fragment-based approach to discovery of Receptor for Advanced Glycation End products inhibitors. Proteins 2021, 89, 1399–1412. [CrossRef]

- Yatime, L.,; Betzer, C.,; Jensen, R.K.,; Mortensen, S.,; Jensen, P.H.,; Andersen, G.R. The Structure of the RAGE:S100A6 Complex Reveals a Unique Mode of Homodimerization for S100 Proteins. Structure 2016, 24, 2043–2052. [CrossRef]

- Furey, W.,; Jr, Wang, B.C.,; Yoo, C.S.,; Sax, M. Structure of a novel Bence-Jones protein (Rhe) fragment at 1.6 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1983, 167, 661–692. [CrossRef]

- Herron, J.N.,; He, X.M.,; Mason, M.L.,; Voss, E.W. Jr.,; Edmundson, A.B. Three-dimensional structure of a fluorescein-Fab complex crystallized in 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol. Proteins 1989, 5, 271–280. [CrossRef]

- Leahy, D.J.,; Hendrickson, W.A.,; Aukhil, I.,; Erickson, H.P. Structure of a fibronectin type III domain from tenascin phased by MAD analysis of the selenomethionyl protein. Science 1992, 258, 987–991. [CrossRef]

- Ito, N.,; Phillips, S.E.,; Stevens, C.,; Ogel, Z.B.,; McPherson, M.J.,; Keen, J.N.,; Yadav, K.D.,; Knowles, P.F. Novel thioether bond revealed by a 1.7 Å crystal structure of galactose oxidase. Nature 1991, 350, 87–90. [CrossRef]

- Holden, H.M.,; Ito, M.,; Hartshorne, D.J.,; Rayment, I. X-ray structure determination of telokin, the C-terminal domain of myosin light chain kinase, at 2.8 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1992, 227, 840–851. [CrossRef]

- Pinkner, J.S.,; Remaut, H.,; Buelens, F.,; Miller, E.,; Aberg, V.,; Pemberton, N.,; Hedenström, M.,; Larsson, A.,; Seed, P.,; Waksman, G.,; et al. Rationally designed small compounds inhibit pilus biogenesis in uropathogenic bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2006, 103, 17897–17902. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.E.,; Huang, D.,; Szczepaniak, A.,; Cramer, W.A.,; Smith, J.L. Crystal structure of chloroplast cytochrome f reveals a novel cytochrome fold and unexpected heme ligation. Structure 1994, 2, 95–105. [CrossRef]

- Volbeda, A.,; Hol, W.G. Crystal structure of hexameric haemocyanin from Panulirus interruptus refined at 3.2 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1989, 209, 249–279. [CrossRef]

- Hough, M.A.,; Hasnain, S.S. Structure of fully reduced bovine copper zinc superoxide dismutase at 1.15 Å. Structure 2003, 11, 937–946. [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.B.,; Davletov, B.A.,; Berghuis, A.M.,; Südhof, T.C.,; Sprang, S.R. Structure of the first C2 domain of synaptotagmin I: a novel Ca2+/phospholipid-binding fold. Cell 1995, 80, 929–938. [CrossRef]

- Tawfeeq, C.,; Song, J.,; Khaniya, U.,; Madej, T.,; Wang, J.,; Youkharibache, P.,; Abrol, R. Towards a structural and functional analysis of the immunoglobulin-fold proteome. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2024, 138, 135–178. [CrossRef]

- Chidyausiku, T.M.,; Mendes, S.R.,; Klima, J.C.,; Nadal, M.,; Eckhard, U.,; Roel-Touris, J.,; Houliston, S.,; Guevara, T.,; Haddox, H.K.,; Moyer, A.,; et al. De novo design of immunoglobulin-like domains. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5661. [CrossRef]

- Sirois, C.M.,; Jin, T.,; Miller, A.L.,; Bertheloot, D.,; Nakamura, H.,; Horvath, G.L.,; Mian, A.,; Jiang, J.,; Schrum, J.,; Bossaller, L.,; et al. RAGE is a nucleic acid receptor that promotes inflammatory responses to DNA. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 2447–2463. [CrossRef]

- Kabsch, W.,; Sander, C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 1983, 22, 2577–2637. [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, E.G.,; Sessions, R.B.,; Thornton, J.M.,; Woolfson, D.N. Determinants of strand register in antiparallel beta-sheets of proteins. Protein Sci. 1998, 7, 2287–2300. [CrossRef]

- Halaby, D.M.,; Poupon, A.,; Mornon, J. The immunoglobulin fold family: sequence analysis and 3D structure comparisons. Protein Eng. 1999, 12, 563–571. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.,; Ray, R.,; Singer, D.,; Böhme, D.,; Burz, D.S.,; Rai, V.,; Hoffmann, R.,; Shekhtman, A. The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) specifically recognizes methylglyoxal-derived AGEs. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 3327–3335. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.,; Han, C.W.,; Jeong, M.S.,; Kwon, T.J.,; Choi, J.Y.,; Jang, S.B. Cryo-EM structure of HMGB1-RAGE complex and its inhibitory effect on lung cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 187, 118088. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.K.,; Gupta, A.A.,; Yu, C. Interaction of the S100A6 mutant (C3S) with the V domain of the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 434, 328–333. [CrossRef]

- Penumutchu, S.R.,; Chou, R.H.,; Yu, C. Structural insights into calcium-bound S100P and the V domain of the RAGE complex. PLoS One 2014, 9(8), e103947. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.L.,; Colbert, C.L. X-ray structure of Ca(2+)-S100B with human RAGE-derived W72 peptide. To be published. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.L.,; Indurthi, V.S.,; Neau, D.B.,; Vetter, S.W.,; Colbert, C.L. Structural insights into the binding of the human receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) by S100B, as revealed by an S100B-RAGE-derived peptide complex. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2015, 71, 1176–1183. [CrossRef]

- Denessiouk, K.,; Permyakov, S.,; Denesyuk, A.,; Permyakov, E.,; Johnson, M.S. Two structural motifs within canonical EF-hand calcium-binding domains identify five different classes of calcium buffers and sensors. PLoS One 2014, 9, e109287. [CrossRef]

- Denesyuk, A.I.,; Denessiouk, K.,; Johnson, M.S.,; Uversky, V.N. Structural Catalytic Core of the Members of the Superfamily of Acid Proteases. Molecules 2024, 29, 3451. [CrossRef]

| PDB ID | β-strand B | β-strand C | β-strand E | β-strand F |

Disulfide bridge / polar interactions |

Ref. # |

| IgVRAGE (6XQ1_A) | Leu34, Leu36, Cys38 | Leu49, Trp51, Leu53 | Gly82, Leu84, Leu86 | Phe97, Cys99, Ala101 |

Cys38-Cys99 NE1/Trp51-O/Gly82 |

49 |

| IgC1RAGE (6XQ1_A) | Asn139, Val141, Cys144 | Leu155, Trp157, Leu159 | Ser190, Leu192, Val194 | Phe206, Cys208, Phe210 |

Cys144-Cys208 OD1/Asn139-N/Thr134 ND2/Asn139-O/Thr134 OG/Ser190-NE1/Trp157 |

49 |

| IgC2RAGE (4P2Y_A) | Val255, Leu257, Cys259 | Ile269, Trp271, Lys273 | Pro284, Leu286, Leu288 | Tyr299, Cys301, Ala303 |

Cys259-Cys301 NE1/Trp271-O/Ser283 NZ/Lys273-O/Gln294 OH/Tyr299-O/Asp295 |

50 |

| IgV (2RHE_A) | Val18, Ile20, Cys22 | Val34, Trp36, Gln38 | Ala72, Leu74, Ile76 | Tyr87, Cys89, Ala91 |

Cys22-Cys89 NE2/Gln38-OH/Tyr87 |

51 |

| IgC (4FAB_H) | Leu143, Cys145, Val147 | Val155, Leu157, Trp159 | Leu182, Ser184, Val186 | Cys200,Val202, His204 |

Cys145-Cys200 NE1/Trp159-OG/Ser184 ND1/His204-OG/Ser208 NE2/His204-O/Phe151 |

52 |

| IgS (1TEN_A) | Ala819, Ile821, Trp823 | Ile833, Leu835, Tyr837 | Asn856, Tyr858, Ile860 | Val871, Leu873, Ser875 | O/Trp823-ND2/Asn856 OG/Ser875-O/Asp804 |

53 |

| IgH (1GOF_A) | Gly558, Ile560, Ile562 | Ala571, Leu573, Arg575 | Tyr602, Phe604, Val606 | Trp618, Leu620, Val622 | NH1/Arg575-OD1/Asp586 NH2/Arg575-O/Met233 NH2/Arg575-O/Pro615 OH/Tyr602-N/Ile568 NE1/Trp618-O/Leu614 |

54 |

| IgI (1FHG_A) | Ala59, Phe61, Cys63 | Val73, Trp75, Lys77 | Cys98, Leu100, Ile102 | Tyr113, Cys115, Ala117 |

Cys63-Cys115 NZ/Lys77-O/Asp108 OH/Tyr113-O/Asp109 |

55 |

| 2J7L_A | Met18, Leu20, Ile22 | Ala33, Ala35, Ile37 | Ser65, Val67, Leu69 | Phe88, Leu90, Glu92 | OG/Ser65-OE1/Gln57 OE1/Glu92-N/Ala1 OE2/Glu92-N/Ala1 |

56 |

| 1CTM_A | Phe45, Ala47, Val49 | Ala73, Leu75, Leu77 | Ile126, Phe128, Ile130 | Ile148, Val150, Gly152 | N/A | 57 |

| 1HC1_A | Phe460, Tyr462, Ile464 | Phe478, Ile480, Leu482 | Ile519, Arg521, Ser523 | Leu582, Val584, Val586 | NH2/Arg521-O/Asp525 NH2/Arg521-OD2/Asp506 |

58 |

| 1Q0E_A | Val29, Gly31, Ile33 | His41, Phe43, Val45 | Ala93, Val95, Ile97 | Met115, Val117, Glu119 | ND1/His41-O/His118 NE2/His41-O/Thr37 OE1/Glu119-N/Ser140 |

59 |

| 1RSY_A | Leu158, Val160, Ile162 | Val181, Val183, Leu185 | Glu208, Phe210, Phe212 | Leu224, Met226, Val228 | OE2/Glu208-N/Lys196 | 60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).