Introduction: Immunoglobulins are conjugated protein molecules that are created by plasma cells in response to an immunogen and that perform as antibodies. They are discharged from lymph nodes and spleen into the blood wherever they function the effector of body substance immunity. They act as a crucial a part of the immune response by specifically recognizing and binding to explicit antigens, look out for bacterium or viruses, and aiding in their destruction. The protein immune response is extremely complicated and extremely specific. Immunoglobulins specifically bind to one or several closely related antigens. Every immune globulin only binds to a selected antigenic determinant. Antigen binding by an antibody is a major function of the antibody and can protect the host. The valence of an antibody refers to the number of antigenic determinants that a single antibody molecule can bind to. All antibodies have a valence of at least two, and in some cases even more. Immunoglobulins mediate many of these effector functions. Normally, the ability to perform a particular effector function requires the antibody to bind to that antigen. Not all immunoglobulins mediate all effector functions. (Schroeder, H. W., Jr, & Cavacini, L. (2010))

Research Objectives

Research methodology refers to the systematic framework that researchers use to plan and conduct their studies. It encompasses a range of processes, including research design, data collection methods, sampling techniques, and data analysis procedures. Research design outlines the overall strategy, which can be qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods, depending on the nature of the research question. Data collection methods, such as surveys, experiments, interviews, or observational studies, are chosen based on the objectives of the research. Additionally, sampling techniques determine how participants or data sources are selected, whether through random, stratified, or purposive methods. Finally, data analysis methods provide the tools needed to interpret the collected data, ensuring that conclusions drawn are accurate and meaningful. The primary purpose of conducting research methodology is to provide a structured and coherent approach to inquiry, guiding researchers through the complexities of their studies. A well-defined methodology ensures that the research process is systematic and logical, which is essential for addressing specific research questions or hypotheses. By employing rigorous methodologies, researchers can enhance the validity and reliability of their findings, ensuring that the results are both accurate and consistent. This robustness is crucial not only for building credibility in the research community but also for informing future studies. Furthermore, clear methodologies facilitate reproducibility, allowing other researchers to replicate the study and validate its findings, thereby contributing to the overall body of knowledge in the field. The impact of research methodology extends beyond the individual study, significantly influencing the quality of research outcomes and their implications for policy and practice. A sound methodology leads to high-quality results that can provide valuable insights into the topic being studied. In the context of immunoglobulins, rigorously conducted research can shed light on their structural characteristics, functional roles, and therapeutic applications, ultimately informing clinical practices and health policies. Furthermore, well-conducted studies can identify gaps in existing research, guiding future investigations and innovations in the field. Overall, a robust research methodology not only enhances the credibility of findings but also contributes to the advancement of science and its application in real-world contexts. In the context of the article “Immunoglobulins: Structure, Function, and Therapeutic Applications in Immune Response,” research methodology plays a vital role in enhancing the overall quality and impact of the work. By employing a systematic review of the existing literature using rigorous methodologies, the article can uncover critical insights into the structure and function of immunoglobulins, advancing the understanding of their biological significance. Moreover, appropriate research methodologies are essential for evaluating the efficacy of immunoglobulin therapies in treating various immune-related conditions, such as autoimmune diseases and infections. These findings can lead to improved clinical guidelines and treatment protocols, optimizing the use of immunoglobulins in therapeutic settings. Ultimately, a well-defined research methodology will not only bolster the credibility of the article’s findings but also inform future research directions and clinical practices in immunology.

Examine the Structure of Immunoglobulins

Objective: To provide a detailed analysis of the molecular structure of immunoglobulins, including their distinct isotypes and structural domains.

Methodology: Utilize structural biology techniques, such as X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy, to illustrate the three-dimensional structure of immunoglobulins. Review existing literature to discuss the implications of structural variations on function.

Investigate the Functions of Immunoglobulins

Objective: To explore the various roles of immunoglobulins in the immune response.

Methodology: Analyze studies that describe the mechanisms by which immunoglobulins interact with antigens, activate complement pathways, and facilitate immune cell recruitment. Discuss their roles in both innate and adaptive immunity based on experimental and clinical data.

Evaluate Therapeutic Applications

Objective: To assess current and potential therapeutic applications of immunoglobulins in clinical settings.

Methodology: Review clinical trial data and case studies on the use of immunoglobulins in treating autoimmune diseases, infectious diseases, and for immunotherapy. Evaluate the effectiveness, safety, and regulatory considerations of various immunoglobulin products.

Analyze Challenges and Future Directions

Objective: To identify the challenges in the development and application of immunoglobulin-based therapies and propose future research directions.

Methodology: Synthesize findings from the literature and expert opinions to discuss limitations in current therapies, such as cost, availability, and patient response variability. Propose areas for future research, including novel therapeutic formulations and delivery methods.

Research Methodology

Research methodology refers to the systematic plan and approach employed to conduct research. It encompasses the techniques, procedures, and processes used to gather and analyze data, guiding researchers in their inquiry to answer specific questions or test hypotheses. Research methodology is a systematic framework that outlines the processes and techniques used to conduct research. It serves as a blueprint that guides researchers in planning and executing their studies, ensuring that the research objectives are met in a coherent and organized manner. Research methodology encompasses various components, including the selection of research design, data collection methods, and analysis techniques. By providing a structured approach to inquiry, methodology helps researchers formulate their questions, identify relevant variables, and choose appropriate tools for data collection, such as surveys, experiments, or observational studies. This systematic approach not only enhances the validity and reliability of research findings but also enables other scholars to replicate studies and build upon existing knowledge. The importance of research methodology lies in its ability to ensure rigor and transparency in the research process. A well-defined methodology provides clarity about how research is conducted, which is crucial for evaluating the credibility and significance of the findings. Moreover, it helps researchers avoid biases, making it easier to draw meaningful conclusions and recommendations. Ultimately, research methodology serves as the foundation upon which robust and reliable research is built, facilitating the advancement of knowledge across various fields.

Purpose: Research methodology is vital for several reasons. First, it provides a structured framework for researchers, ensuring that the research is conducted systematically and coherently. It helps in defining the research objectives, selecting appropriate methods for data collection and analysis, and ensuring that the findings are credible and valid. Additionally, a well-defined methodology allows other researchers to replicate the study or build upon its findings.

Literature Review

A literature review is a comprehensive survey of existing research and scholarly work related to a particular topic or research question. It involves the critical analysis and synthesis of previous studies, theories, and methodologies to provide context and background for new research. A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing research related to a specific topic or research question. It serves multiple purposes, including situating new research within the broader context of existing literature, identifying gaps in knowledge, and highlighting relevant theories and methodologies. A literature review provides an opportunity for researchers to engage with previous studies, critically evaluate their findings, and synthesize information to inform their own research. It helps in establishing the theoretical framework for the study and can guide researchers in refining their research questions or hypotheses. Conducting a literature review involves several systematic steps. First, researchers identify relevant sources of information, such as academic journals, books, and reputable online databases. Next, they search for literature using specific keywords and phrases related to their research topic. Once relevant studies are identified, researchers assess the quality and relevance of each source, focusing on the most impactful findings and contributions to the field. After gathering the necessary information, researchers synthesize their insights, organizing the literature thematically or chronologically to provide a clear narrative that establishes the context for their own research.

Importance: Literature reviews serve multiple purposes. They help identify gaps in the current knowledge base, allowing researchers to position their work within the existing body of literature. They also provide insights into methodologies that have been previously used, guiding researchers in selecting appropriate methods for their own studies. Moreover, a literature review can help in understanding theoretical frameworks and contextualizing findings.

Conducting a Literature Review

Identifying Sources: Begin by identifying relevant databases and sources where research articles, books, and other academic materials can be found. Common databases include Google Scholar, PubMed, JSTOR, and university libraries.

Searching for Literature: Use keywords and phrases related to your research topic to conduct searches in the identified databases. This process may involve using Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) to refine search results.

Selecting Relevant Studies: Review the abstracts and conclusions of the retrieved articles to determine their relevance to your research question. Include studies that contribute significantly to the understanding of your topic.

Analyzing and Synthesizing Information: Critically assess the quality and findings of the selected studies. Identify themes, trends, and gaps in the literature, and synthesize this information to highlight the significance of your research.

Organizing the Review: Structure your literature review logically, often grouping studies by themes, methodologies, or chronological order. Ensure that your review clearly demonstrates how your research fits into the existing literature.

Online Research

Online research involves using the internet to gather information and data from various digital sources. This can include academic articles, databases, reputable websites, and online surveys. Online research refers to the process of gathering information and data from digital sources via the internet. This method has become increasingly popular due to the accessibility and abundance of information available online. Online research encompasses a variety of techniques, including searching academic databases, accessing digital libraries, and utilizing search engines to find relevant articles and studies. It can also involve collecting primary data through online surveys or interviews.

To conduct online research effectively, researchers start by defining their research questions and identifying keywords related to their topic. They then utilize search engines and academic databases, such as Google Scholar or JSTOR, to locate relevant literature. Evaluating the credibility of sources is crucial; researchers assess the author’s qualifications, publication date, and the reputation of the publication to ensure the reliability of the information. After gathering data, researchers document.

Conducting an Online Research Process

Defining Research Questions: Clearly articulate the questions or topics you wish to explore.

Utilizing Search Engines and Databases: Use search engines like Google Scholar or academic databases to locate relevant articles and studies. Employ specific keywords to narrow down search results.

Evaluating Sources: Assess the credibility of the information by considering the author’s qualifications, the publication source, and the date of publication. Prioritize peer-reviewed articles and reputable publications.

Collecting Data: Gather relevant data, whether qualitative or quantitative, from various sources. This may include conducting surveys or interviews via online platforms.

Documenting Findings: Keep thorough notes of your sources and findings to facilitate citations and references in your research.

Applications and Research Conduction:

In the research article, I employed a combination of literature review and online research methodologies to explore the topic effectively. Initially, I have identified key themes and gaps in the existing literature related to my research question. This involved gathering relevant studies, analyzing their findings, and synthesizing this information to frame my argument. I have conducted the literature review to identify existing studies and theories related to my research question, assessing their relevance and contribution to the field. By synthesizing insights from these studies, i positioned my work within the broader academic discourse, highlighting gaps that my research aimed to address.

Additionally, I have utilized online resources to access academic articles, databases, and possibly conduct surveys or interviews. By meticulously documenting my sources and integrating both methodologies, I ensured that my research was well-founded, credible, and positioned within the existing body of knowledge. This systematic approach not only strengthened the validity of my findings but also contributed to a richer understanding of the topic I was investigating.

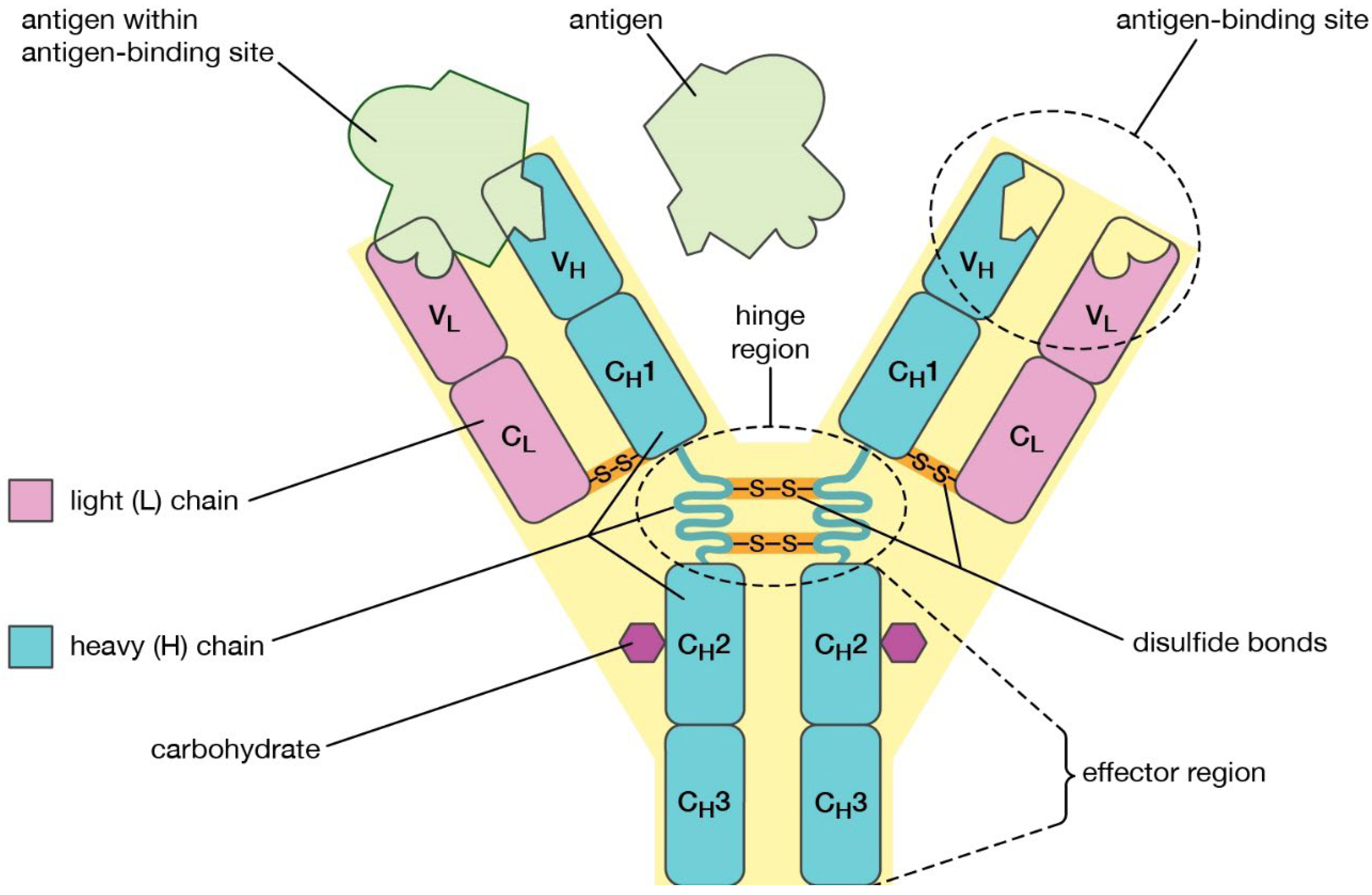

Structure of Immunoglobulins: Immunoglobulin atoms are glycoproteins composed of 1 or more units, each containing four polypeptide chains: two indistinguishable overwhelming chains (H) and two indistinguishable light chains (L). The amino terminal closes of the polypeptide chains appear significant variety in aminoalkanoic corrosive composition and are alluded to as the variable (V) locales to recognize them from the generally steady (C) locales. Each L chain comprises of 1 variable space, VL, and one steady space, CL. The H chains contains a variable space, VH, and three steady spaces CH1, CH2 and CH3. Each overwhelming chain has around twice the sum of amino acids and atomic weight (~50,000) as each light chain (~25,000), driving to a add up to immunoglobulin monomer atomic weight of around 150,000. Overwhelming and lightweight chains are held together by a combination of non-covalent intelligent and covalent interchain disulfide bonds, shaping a reciprocal structure. The V locales of H and L chains include the antigen-binding. (Schroeder, H. W., Jr, & Cavacini, L. (2010))

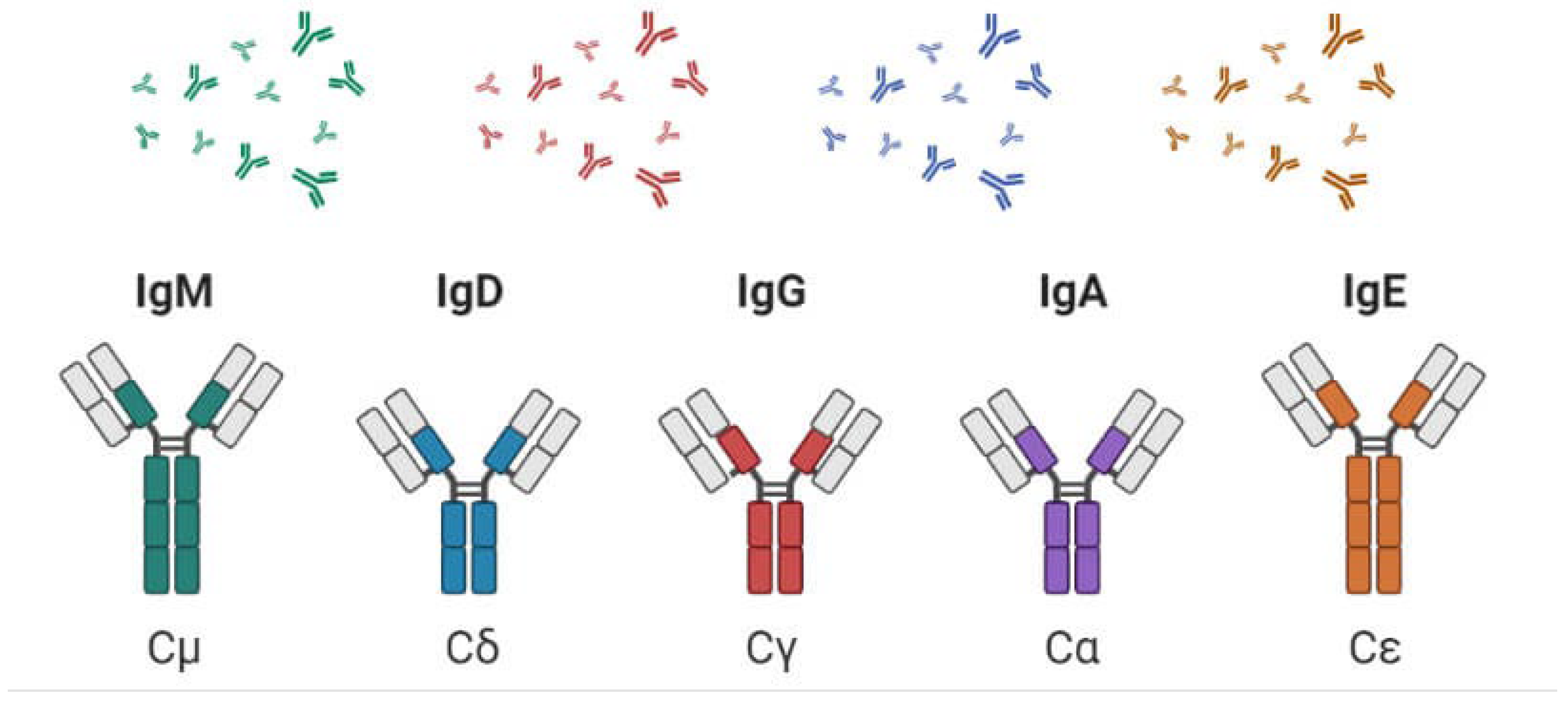

Types of immunoglobulin: Immunoglobulins (Ig), commonly known as antibodies, are glycoprotein molecules produced by plasma cells (activated B cells). They play a crucial role in the immune system by identifying and neutralizing pathogens such as bacteria and viruses. Each immunoglobulin has a specific structure and function, allowing the immune system to adapt and respond to a wide variety of antigens. Immunoglobulins (Ig), also known as antibodies, are specialized glycoproteins produced by plasma cells, which are activated B lymphocytes. They play a crucial role in the immune system by identifying and neutralizing pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and toxins. The unique structure of immunoglobulins, characterized by variable and constant regions, allows them to bind specifically to a wide array of antigens. There are five main classes of immunoglobulins, each with distinct structures, functions, and mechanisms of action that contribute to the body’s immune defense. Immunoglobulins are essential components of the immune system, each serving unique roles that enhance the body’s ability to combat infections and diseases. Their diverse structures and functions, from the mucosal defenses of IgA to the long-term protection offered by IgG, illustrate the complexity and adaptability of the immune response. Understanding the functions of different immunoglobulins is crucial for developing effective vaccines, therapies, and treatments for various diseases.

There are five essential classes of immunoglobulins. They are:

-

1.

immunoglobulin A (IgA) – a dimer with α (alpha) heavy chain:

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) is a dimeric antibody with two α (alpha) heavy chains. It is predominantly found in mucosal areas such as the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and urogenital tracts, as well as in secretions like saliva, tears, and breast milk. IgA serves as the first line of defense against pathogens entering through mucosal surfaces. Its primary function is to prevent pathogens from adhering to and penetrating epithelial cells. This is achieved through a mechanism known as immune exclusion, where IgA binds to antigens and prevents their attachment to mucosal surfaces. In addition to neutralizing pathogens, IgA can also facilitate their removal through the mucosal surfaces, thus preventing infection. The presence of IgA in breast milk is particularly vital, as it provides passive immunity to infants, protecting them during their early development when their immune systems are not fully mature.

Structure: Dimer (two subunits) with an alpha (α) heavy chain.

Function: IgA is primarily found in mucosal areas, such as the gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract, and urogenital tract, as well as in saliva, tears, and breast milk. It protects mucosal surfaces by preventing pathogens from adhering to epithelial cells, thus acting as the first line of defense.

Mechanism of Action: IgA binds to pathogens and toxins, neutralizing them and preventing their entry into the body. Its presence in secretions helps create a barrier against infections.

-

2.

immunoglobulin D (IgD) – a monomer with δ (delta) heavy chain:

Immunoglobulin D (IgD) is a monomeric antibody characterized by a single δ (delta) heavy chain. It is found primarily on the surface of B cells, where it functions as a receptor for antigens. IgD plays a crucial role in the activation and differentiation of B cells, which are essential for the adaptive immune response. When an antigen binds to IgD on the surface of a B cell, it triggers a series of intracellular signaling events that lead to the activation of the B cell. This process is crucial for the subsequent proliferation of B cells and the production of antibodies specific to the encountered antigen. Although IgD is less understood compared to other immunoglobulins, its presence is essential for initiating a robust immune response and ensuring that B cells are primed to respond effectively to infections.

Structure: Monomer with a delta (δ) heavy chain.

Function: IgD is primarily found on the surface of B cells as a receptor for antigens and plays a role in B cell activation and differentiation.

Mechanism of Action: Upon binding to an antigen, IgD helps initiate the signaling cascade that activates B cells, leading to antibody production and immune response.

-

3.

immunoglobulin E (IgE) – a monomer with ε (epsilon) heavy chain:

Immunoglobulin E (IgE) is a monomeric antibody with an ε (epsilon) heavy chain. It is primarily associated with allergic reactions and defense against parasitic infections. While IgE is present in relatively low concentrations in the bloodstream, its role is significant in mediating hypersensitivity reactions. Upon exposure to an allergen, IgE binds to the surface of mast cells and basophils, which are immune cells involved in allergic responses. This binding leads to the degranulation of these cells, resulting in the release of histamine and other inflammatory mediators. This response can cause symptoms ranging from mild allergic reactions to severe anaphylactic shock. Additionally, IgE plays a role in combating parasitic infections by promoting the activation of eosinophils, which are effective in eliminating parasites.

Structure: Monomer with an epsilon (ε) heavy chain.

Function: IgE is involved in allergic reactions and defense against parasitic infections. It is present in very low concentrations in the blood.

Mechanism of Action: IgE binds to allergens and triggers mast cells and basophils to release histamine and other chemicals, leading to inflammation and allergic symptoms. It also helps mediate the immune response against parasites by promoting the recruitment of eosinophils.

-

4.

immunoglobulin G (IgG) – a monomer with γ (gamma) heavy chain:

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) is the most abundant antibody in the bloodstream, represented as a monomer with a γ (gamma) heavy chain. It plays a pivotal role in the adaptive immune response, providing long-term protection against infections. IgG is highly versatile and is involved in various immune functions, including opsonization, neutralization, and complement activation. One of its key functions is to opsonize pathogens, marking them for destruction by phagocytic cells such as macrophages and neutrophils. IgG also neutralizes toxins and viruses by binding to them, preventing their interaction with host cells. Furthermore, IgG can activate the complement system, a group of proteins that enhances the ability of antibodies to clear pathogens. Importantly, IgG is capable of crossing the placenta, providing passive immunity to the fetus during pregnancy, which is critical for protecting newborns during their vulnerable early life.

Structure: Monomer with a gamma (γ) heavy chain.

Function: IgG is the most abundant antibody in the bloodstream and plays a key role in long-term immunity. It is essential for opsonization (marking pathogens for destruction), neutralizing toxins and viruses, and activating complement proteins.

Mechanism of Action: IgG binds to pathogens, enhancing their uptake by phagocytic cells (like macrophages) and triggering the complement system to eliminate pathogens. It can also cross the placenta, providing passive immunity to the fetus.

-

5.

immunoglobulin M (IgM) – a pentamer with μ (mu) heavy chain:

Immunoglobulin M (IgM) is a pentameric antibody composed of five subunits, each with a μ (mu) heavy chain. It is the first antibody produced in response to an infection and is primarily found in the bloodstream. IgM plays a crucial role in the early stages of the immune response, serving as a primary defense against pathogens. The pentameric structure of IgM allows it to effectively agglutinate pathogens, facilitating their clearance from the bloodstream. This clumping enhances the ability of phagocytes to recognize and eliminate the pathogens. Additionally, IgM is a potent activator of the complement system, leading to the lysis of pathogens. Its rapid production in response to an initial infection is vital for controlling the spread of pathogens while the adaptive immune system gears up to produce more specific antibodies.

Structure: Pentamer (five subunits) with a mu (μ) heavy chain.

Function: IgM is the first antibody produced in response to an infection and is mainly found in the bloodstream.

Mechanism of Action: IgM is highly effective at agglutinating (clumping together) pathogens, enhancing their clearance by phagocytes. It also activates the complement system efficiently, leading to lysis (destruction) of pathogens.

These are recognized by the sort of overwhelming chain found within the particle. IgG particles have overwhelming chains known as gamma-chains; IgMs have mu-chains; IgAs have alpha-chains; IgEs have epsilon-chains; and IgDs have delta-chains. Immunoglobulins are vital for immune defense, each tailored for specific functions and mechanisms that protect the body from infections and diseases. Their diverse structures and roles contribute to the adaptability and efficiency of the immune response.

The function of Immunoglobulin: The variable regions of the immunoglobulin heavy and lightweight chains from the antibody combining site. There are many functions of the variable region, primarily those are involved in antibody-antigen interactions, including precipitation, agglutination, and neutralization of antigen. Types of Immunoglobulins and Their Functions:

IgG: The most abundant antibody in serum, providing long-term protection and involved in opsonization and complement activation.

IgA: Found in mucosal areas and secretions (e.g., saliva, tears, breast milk), playing a key role in mucosal immunity.

IgM: The first antibody produced during an immune response, effective in agglutination and complement activation.

IgE: Associated with allergic reactions and defense against parasites.

IgD: Function is less understood, but it is involved in B cell activation and maturation. Immunoglobulins (Ig), also known as antibodies, are glycoproteins produced by plasma cells (activated B cells) in response to antigens (foreign substances). They play a crucial role in the immune system’s ability to identify and neutralize pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, and toxins. Here’s a brief overview and elaboration of the main functions of immunoglobulins:

1. Neutralization of Pathogens

One of the foremost functions of immunoglobulins is the neutralization of pathogens, including viruses and bacteria. When an antibody binds to a pathogen, it can block specific receptors on the pathogen’s surface that are essential for infection. For instance, antibodies can prevent viruses from attaching to and entering host cells, thereby inhibiting their ability to replicate and cause disease. This neutralization process not only renders the pathogens inactive but also facilitates their clearance from the body by phagocytes, which can easily engulf the bound pathogens. Neutralization is crucial in providing immediate protection during the early stages of infection and is a key mechanism by which vaccines confer immunity.

Function: Immunoglobulins can bind to pathogens such as viruses and bacteria, neutralizing them and preventing them from entering or infecting host cells.

Elaboration: This process often involves the blocking of pathogen receptors or binding sites, thus hindering their ability to infect host cells. Neutralized pathogens can be cleared by phagocytic cells.

2. Opsonization

Immunoglobulins enhance the process of opsonization, a mechanism by which pathogens are marked for destruction by immune cells. Opsonization occurs when antibodies coat the surface of pathogens, making them more recognizable to phagocytic cells such as macrophages and neutrophils. The Fc region of the bound antibodies interacts with specific receptors on these immune cells, facilitating the engulfment and subsequent destruction of the pathogens. This function significantly increases the efficiency of the immune response, particularly against encapsulated bacteria, which can be challenging for the immune system to target without the aid of antibodies.

Function: Antibodies coat pathogens, enhancing their recognition and ingestion by phagocytes (like macrophages and neutrophils).

Elaboration: The Fc region of antibodies binds to specific receptors on phagocytes, facilitating the engulfment of the antibody-coated pathogen. This process increases the efficiency of the immune response.

3. Activation of Complement System

Immunoglobulins, particularly IgM and IgG, are capable of activating the complement system, a series of proteins that play a pivotal role in immune defense. When antibodies bind to antigens on the surface of pathogens, they can trigger a cascade of complement activation. This activation leads to various outcomes, including opsonization of pathogens, inflammation, and the formation of the membrane attack complex, which can directly lyse bacteria. The complement system works synergistically with antibodies, amplifying the immune response and promoting the clearance of pathogens from the body.

Function: Immunoglobulins, particularly IgM and IgG, can activate the complement system, a group of proteins that assist in the destruction of pathogens.

Elaboration: When antibodies bind to pathogens, they can trigger a cascade of complement activation, leading to opsonization, inflammation, and the formation of the membrane attack complex, which can lyse the pathogen.

4. Agglutination and Precipitation

Antibodies can facilitate agglutination and precipitation, processes that enhance the clearance of pathogens from the bloodstream. Agglutination occurs when antibodies bind to multiple antigens on the surface of pathogens, causing them to clump together. This clumping makes it easier for phagocytes to identify and engulf the aggregated pathogens. Similarly, precipitation involves antibodies binding to soluble antigens, forming complexes that can be more readily eliminated by the immune system. These processes are essential for clearing infections and reducing the burden of pathogens within the body.

Function: Antibodies can cross-link multiple antigens, causing them to clump together (agglutination) or precipitate out of solution (precipitation).

Elaboration: This clumping makes it easier for phagocytes to recognize and eliminate pathogens. Agglutination is particularly important for bacterial pathogens, while precipitation is often relevant for soluble antigens.

5. Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC)

Antibodies also play a crucial role in antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), a mechanism by which immune cells can target and destroy infected or malignant cells. In this process, certain antibodies bind to antigens expressed on the surface of infected cells or cancer cells. Natural killer (NK) cells can then recognize the bound antibodies through their Fc receptors, leading to the release of cytotoxic molecules that induce apoptosis in the target cell. ADCC is particularly important in controlling viral infections and eliminating tumor cells, highlighting the versatility of antibodies in mediating immune responses.

Function: Certain antibodies can bind to infected or malignant cells, marking them for destruction by natural killer (NK) cells.

Elaboration: NK cells recognize the Fc region of the bound antibody and release cytotoxic molecules that induce apoptosis (programmed cell death) in the target cell.

6. Transport and Distribution of Antigens

Immunoglobulins serve a vital function in the transport and distribution of antigens throughout the body. For example, secretory IgA is found in mucosal secretions, such as saliva, tears, and breast milk, providing localized protection against pathogens that enter the body through mucosal surfaces. By binding to pathogens at these entry points, IgA can neutralize them and prevent their adherence to epithelial cells, reducing the risk of infection. This mucosal immunity is critical for protecting vulnerable sites and maintaining overall health.

Function: Immunoglobulins can transport and distribute antigens within the body, aiding in the immune response.

Elaboration: For instance, secretory IgA is found in mucosal areas (like the gut and respiratory tract) and protects against pathogens by neutralizing them and preventing their adherence to epithelial cells.

7. Memory and Long-Term Immunity:

Immunoglobulins are also instrumental in establishing immunological memory, a hallmark of adaptive immunity. Upon initial exposure to an antigen, specific B cells differentiate into memory B cells, which can persist for years or even decades. These memory cells can quickly produce specific antibodies upon subsequent exposures to the same antigen, leading to a faster and more robust immune response. This function is the basis for the effectiveness of vaccines, which aim to induce long-lasting immunity against specific pathogens.

Function: Certain immunoglobulins, particularly IgG, are involved in creating immunological memory.

Elaboration: Upon first exposure to an antigen, memory B cells are formed, which can quickly produce specific antibodies upon subsequent exposures, leading to a faster and more robust immune response.

8. Role in Allergic Reactions

Immunoglobulin E (IgE) plays a significant role in allergic reactions and the body’s defense against parasitic infections. When IgE binds to allergens, it triggers the degranulation of mast cells and basophils, leading to the release of histamines and other inflammatory mediators. This release can result in various allergic symptoms, such as itching, swelling, and difficulty breathing. While IgE’s role in allergy is often viewed negatively, it is also crucial for mediating immune responses against parasitic infections, highlighting the dual nature of immunoglobulins in the immune system.

Function: Immunoglobulin E (IgE) is specifically involved in allergic reactions and defense against parasitic infections.

Elaboration: When IgE binds to allergens, it triggers the release of histamine and other mediators from mast cells and basophils, leading to allergic symptoms.

Immunoglobulins (Ig), commonly known as antibodies, are essential components of the immune system, primarily produced by plasma cells in response to foreign antigens. They play several critical roles in protecting the body from infections, contributing to both innate and adaptive immunity. immunoglobulins are versatile molecules that perform essential functions in the immune system. From neutralizing pathogens and facilitating opsonization to activating the complement system and mediating allergic responses, their diverse roles underscore their importance in maintaining health and defending against disease.

Analytical Discussion

The analytical discussion of immunoglobulins and their interactions with antigens highlights the complexity and significance of these immune mechanisms. Understanding antibody-antigen interactions provides valuable insights into how the immune system operates, specifically through processes such as precipitation, agglutination, and neutralization. Each of these mechanisms plays a vital role in the immune response, facilitating the elimination of pathogens and contributing to overall health. By studying these interactions, researchers can develop effective diagnostic tools, vaccines, and therapeutic strategies, ultimately advancing our understanding of immunology and improving public health outcomes. Immunoglobulins, or antibodies, are glycoproteins produced by plasma cells that play a crucial role in the immune response. They function primarily by recognizing and binding to specific antigens, which are foreign molecules that elicit an immune response. The interaction between antibodies and antigens is central to various immune mechanisms, including agglutination, precipitation, and neutralization. Understanding these interactions provides valuable insights into how the immune system protects the body from infections and diseases.

Antibody-antigen interaction: The specificity of the antibody-antigen interaction is determined by the unique structure of the antibody’s binding site, which is shaped to fit specific antigenic determinants (epitopes). When an antibody binds to an antigen, it forms a complex that can trigger various immune responses. This interaction is highly specific; for example, a single antibody may only recognize a particular protein on the surface of a pathogen. The strength of this interaction, characterized by affinity and avidity, influences the effectiveness of the immune response. High-affinity antibodies can effectively neutralize pathogens, while lower-affinity antibodies may require multivalent interactions for optimal binding. The strength of a counter-acting agent antigen collaboration is usually portrayed as far as the proclivity of the immunizer for that antigen. For the reaction of antibody (Ab) with antigen (Ag), where Ab-Ag denotes the antibody-antigen complex, the association constant for the reaction (Ka) is given by the equation below, where terms within brackets denote the molarity of those substances. (E.Goldberg & Djavadi-Ohaniance, 1993, #)

Ka = [Ab-Ag] / ([Ab][Ag])

Precipitation: Precipitation is a process that occurs when soluble antigens interact with antibodies, leading to the formation of insoluble complexes. This reaction is particularly relevant in the context of immune responses to bacterial toxins and soluble proteins. When antibodies bind to soluble antigens in a body fluid (e.g., serum), they can create large aggregates that precipitate out of solution. This process is critical for clearing soluble antigens from the bloodstream, facilitating their removal by phagocytic cells. From an analytical perspective, precipitation involves several factors, including the concentration of both antibodies and antigens, as well as the ionic conditions of the environment. The formation of precipitin complexes is influenced by the law of mass action; as the concentrations of antibodies and antigens increase, the likelihood of forming complexes rises. However, there is an optimal ratio of antibody to antigen for effective precipitation. If there is too much antigen (prozone effect) or too much antibody, precipitation may not occur efficiently. Understanding these dynamics is essential for diagnosing diseases using immunoassays that rely on precipitation reactions. Edifices structure and accelerate when integral antibodies and antigens are blended in an appointment. The proportion of rushing is said to antigen and neutralizer valence, reactant centers, and checking specialist affection, which moreover may depend upon the pH and ionic strength of the plan. The valence of a neutralizer alludes to the number of restricting locales it has for antigen. Precipitation requires neutralizer and antigen valences of something like two; a Fab section (with a valence of one) can’t encourage antigen. Also, a monovalent antigen can’t cooperate with quite one counter-acting agent thus can’t encourage.

Agglutination: Agglutination refers to the clumping of particles, such as bacteria or red blood cells, due to the binding of antibodies to their respective antigens. This process is a critical mechanism in the immune response, allowing the immune system to effectively target and eliminate pathogens. Agglutination can be observed in various contexts, such as blood typing and bacterial infections. When antibodies bind to multiple antigens on the surface of pathogens, they create large aggregates that can be easily recognized and engulfed by phagocytes. From an analytical standpoint, the agglutination process is influenced by the valency of the antibody, the nature of the antigen, and the environmental conditions, such as temperature and ionic strength. IgM antibodies, with their pentameric structure, are particularly effective at agglutination due to their ability to bind multiple antigens simultaneously, resulting in significant cross-linking. In contrast, IgG antibodies, though typically higher in affinity, have a lower valency and may require a higher concentration to achieve agglutination. Studying agglutination reactions is crucial in clinical diagnostics, where they are used to identify specific pathogens or blood types.

Precipitation and agglutination are reasonably indistinguishable. Precipitation includes solvent antigens and antibodies; agglutination signifies the arrangement of buildings of antibodies with somewhat huge particles, like microscopic organisms or erythrocytes. Both precipitation and agglutination require immune reaction multivalence. Pentameric IgM may be a decent agglutinator and precipitator. Agglutination tests are regularly wont to recognize serum antibodies with specific explicitness. The explicitness could be one ordinarily introduced on the objective cell, or it’s going to not. within the event that not, the immune reaction might be misleadingly coupled to an objective cell, like an erythrocyte (hemagglutination). Sequential weakenings of serum are blended in with target cells, and counter-acting agent levels are measured because the most elevated weakening causing agglutination.

Neutralization: Neutralization is a key function of antibodies that involves blocking the biological activity of pathogens or their toxins. When an antibody binds to a pathogen, it can prevent the pathogen from interacting with host cells, thereby inhibiting infection. This mechanism is particularly significant in viral infections, where antibodies neutralize viruses by preventing them from attaching to and entering host cells. In the context of bacterial infections, neutralization can also occur by inhibiting the action of bacterial toxins. Analytically, neutralization is a complex process that depends on the structure of the antibody and the specific interactions with the pathogen. The effectiveness of neutralization can vary based on factors such as antibody concentration, binding affinity, and the presence of neutralizing epitopes. Studies on neutralization are essential for vaccine development, as they help identify which antibodies confer protective immunity. For instance, neutralizing antibodies against viral pathogens are often the focus of vaccine research, as their presence is crucial for long-lasting immunity. At the purpose when the limiting of neutralizer to an infection renders it unequipped for tainting a phone, the infection is meant to be killed and the immune response is called killing. Similar wording is employed when immunizer restricting inactivates a poison. This impact is dependable to a limited extent for the host resistance that outcomes after specific regular contaminations and after vaccination. Organization of exogenous Ig may likewise be utilized restoratively within the treatment or avoidance of contaminations, poisonous sickness, or to counter medicine gluts.

Applications of Immunoglobulin

Immunoglobulins (Ig), or antibodies, have numerous applications in both clinical and research settings. In medicine, they are essential for passive immunotherapy, where immunoglobulins are administered to patients to boost their immune response against specific infections or toxins. Immunoglobulin therapy is widely used for treating immune deficiencies, autoimmune diseases, and infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. For example, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy is used to treat conditions like chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and Kawasaki disease. Immunoglobulins also play a critical role in diagnostics, where their high specificity for antigens is utilized in techniques such as ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) and western blotting to detect the presence of pathogens or proteins in samples. Immunoglobulins have therapeutic uses during a variety of illnesses. (J. Hudson & Souriau, 2003, #)

Polyclonal antibodies: Polyclonal antibodies are a mixture of antibodies produced by different B cell lineages in response to an antigen. Each antibody in the mixture recognizes a different epitope on the same antigen, making polyclonal antibodies highly versatile and robust in their applications. In research and diagnostics, polyclonal antibodies are often used because of their ability to detect multiple epitopes, making them more sensitive in certain assays like immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunoprecipitation. Clinically, polyclonal antibody preparations, such as antivenoms or antitoxins, are used in emergencies to neutralize toxins or venom rapidly. Their broader reactivity allows for faster neutralization compared to monoclonal antibodies. Polyclonal human immunoglobulin cleaned from plasma has been utilized clinically since the 1940s, initially to forestall viral illnesses like hepatitis, measles, and polio and after 10 years, within the treatment of neutralizer inadequacies in patients with fundamental or assistant kinds of immunodeficiency, the association of immunoglobulins lessens the event and reality of defilement.

Monoclonal antibodies: Monoclonal antibodies are laboratory-produced molecules engineered to bind to a specific antigen. They are uniform in their specificity because they originate from a single clone of B cells. The ability to target a single antigen makes monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) highly effective in both therapeutic and diagnostic applications. In cancer treatment, monoclonal antibodies such as trastuzumab (for HER2-positive breast cancer) are used to target and destroy cancer cells. Monoclonal antibodies are also utilized in autoimmune disease treatments, organ transplant rejection prevention, and infectious disease therapies. Additionally, their precise targeting ability makes them ideal tools in immunodiagnostics, where they can be used to detect specific biomarkers of diseases. Monoclonal antibody (mAb) technology has revolutionized research in many biological disciplines, also as the diagnosis and treatment of disease. (FC, 2000, #)

Production techniques: The production of antibodies, both monoclonal and polyclonal, involves sophisticated biotechnology methods. Polyclonal antibodies are usually produced by immunizing animals, such as rabbits or goats, with an antigen, followed by harvesting and purifying the serum that contains the antibodies. Monoclonal antibodies, on the other hand, are produced using hybridoma technology. This technique involves fusing an antibody-producing B cell with a myeloma cell to create a hybridoma that can continuously produce a specific antibody. Recent advances have introduced recombinant DNA technology to produce monoclonal antibodies, allowing for the generation of humanized or fully human antibodies by manipulating the genetic code for antibody production. Monoclonal antibodies of a perfect particularity can be delivered in enormous amounts for restorative use. The creation development utilizes properties of myeloma cells (undermining B cells which will duplicate perpetually in culture) that are monoclonal and release Ig. the mixture of myeloma cells with typical B cells yields hybridomas. to urge a hybridoma that will deliver the Ig encoded by the typical B cell, a non-discharging myeloma line should be utilized as a mixture accomplice. a technique for choosing melded cells is required. Non-secreting myeloma cell lines are established that possess a defect in the enzyme hypoxanthine-guanine phosphor ribosyltransferase (HGPRT). (C. & G., 1975, #)

Humanized monoclonal antibodies: Humanized monoclonal antibodies are antibodies that have been modified to be more similar to human antibodies. This is done by replacing the animal-derived (typically mouse) regions of the antibody with human sequences, leaving only the antigen-binding regions intact. Humanization reduces the likelihood of an immune response against the therapeutic antibody in patients, making these antibodies more suitable for clinical use. Humanized monoclonal antibodies are widely used in the treatment of various diseases, including cancer, autoimmune disorders, and inflammatory conditions. For example, pembrolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody, is used in immunotherapy to block PD-1, allowing the immune system to attack cancer cells. One technique joins mouse variable locale qualities encoding specific explicitness to human C area qualities to form an illusory immune response. another technique utilizes articulation of human V qualities in microorganisms. Provinces are often evaluated for proteins (neutralizer parts) with wanted specificities. The qualities would then be ready to be connected to C qualities to make a flawless completely human neutralizer.

Bifunctional antibodies: Biofunctional antibodies are engineered to have additional biological activities beyond simply binding to an antigen. These antibodies are designed to trigger specific immune responses, such as engaging immune cells more effectively or delivering toxic payloads directly to cancer cells. For example, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) combine the specificity of an antibody with the potency of a cytotoxic drug, providing targeted cancer therapy with minimal damage to surrounding healthy tissues. Another application involves engineering antibodies to enhance their binding affinity to immune cells, such as natural killer (NK) cells, to boost antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). Hereditary designing has made extra sorts of antibodies that might have significant clinical applications later on. Bifunctional (or bispecific) antibodies are made by the association of two distinct specificities during a solitary immunizer particle. That is, the divalent four chain unit is involved two unmistakable significant light chain coordinates, each with its own unequivocal. Such antibodies are made by merging two hybridomas, making a mixture of hybridomas. This outcome is during a bifunctional neutralizer that improves cytotoxic movement against a particular objective. The viability of this system has been exhibited in creature models. as an example, replication of flu infection in mice are often restrained by a bifunctional neutralizer vaguely focusing on cytotoxic T cells to infection tainted cells. (Moran et al., 1991, #)

Antigenized antibodies: Antigenized antibodies are engineered to display antigenic peptides within their structure. By incorporating peptides from a pathogen or tumor, these antibodies serve a dual function: they not only bind to their target antigen but also present the antigen to immune cells, effectively stimulating a more robust immune response. This concept is especially useful in vaccine development, where antigenized antibodies can help elicit both a humoral (antibody-mediated) and cellular immune response. These antibodies are an innovative approach for creating more potent vaccines and therapies by enhancing the immune system’s ability to recognize and respond to specific antigens. One more kind of changed immunoglobulin is the “antigenized” counter-acting agent. These are made by supplanting a part of the immune response polypeptide with a piece of a microbial antigen. Any succession are often embedded into different segments of the immunizer atom. The fruitful show of microbial peptides contained in neutralizer atoms has been displayed in an assortment of creature frameworks (eg, for flu infection in mice). (ZAGHOUANI et al., 1993, #)

IgG1 fusion proteins: IgG1 fusion proteins are a type of bioengineered molecule that combines the effector functions of an IgG1 antibody with the biological activity of another protein. The IgG1 portion allows for stable binding to immune cells, while the fused protein can have therapeutic effects, such as inhibiting signaling pathways or delivering enzymes to specific tissues. These fusion proteins are particularly valuable in cancer immunotherapy, as they can be designed to deliver immune-modulating proteins to tumors, enhancing the body’s ability to fight the cancer. The IgG1 backbone also enables these proteins to have long half-lives in the bloodstream, making them effective for sustained therapeutic action. IgG1 combination proteins are another class of biologic therapeutics that exploits immunoglobulins’ properties. In these particles, the Fc piece of human IgG1 is joined with an effector protein, which builds the half-existence of the effector protein and delays its organic movement.

Conclusion: Antibodies and their various engineered forms—such as monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies, biofunctional antibodies, humanized monoclonal antibodies, antigenized antibodies, and IgG1 fusion proteins—have revolutionized both therapeutic and diagnostic fields. Their ability to precisely target specific antigens and manipulate immune responses has made them indispensable tools in treating a wide range of diseases, from cancer and autoimmune disorders to infectious diseases. Advances in production techniques and antibody engineering continue to enhance their effectiveness and broaden their applications, offering new possibilities for precision medicine and targeted therapies. Immunoglobulin (Ig) particles are multifunctional parts of the safe system that mediate in communications between antigen particles and an combination of cell and humoral effector frameworks. Critical components in which Ig molecules are essential consolidate the going with: Sanctioning and sign transduction in B cells (on account of surface Ig receptors) Communications with receptors for the steady range of IgG on an grouping of cells, with different down to earth comes about Sanctioning and adjust of the supplement system. Immunoglobulin (Ig) has been observed to be a successful treatment for a good range of immune system and provocative illnesses. As of now, Immunoglobulin is FDA-endorsed for a pair of immune systems and provocative illnesses, e.g., ITP and KS. Notwithstanding, even in ITP and KS, the instrument of activity of IgIV stays to be completely clarified. Albeit no single system can clarify the precious impacts of IgIV, all things considered, some instruments of activity cooperating are answerable for the impacts of IVIG in the numerous clinical problems for which it has been utilized. Perceive that IgIV contains not just an expansive range of IgG antibodies.

References

- Schroeder, H. W., Jr, & Cavacini, L. (2010). Structure and function of immunoglobulins. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology, 125(2 Suppl 2), S41–S52. [CrossRef]

- Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature, 256(5517), 495-497. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/256495a0.

- E.Goldberg, M., & Djavadi-Ohaniance, L. (1993). Methods for measurement of antibody/antigen affinity supported ELISA and RIA. Current Opinion in Immunology, 5(2), 278-281. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/095279159390018N#!

- FC, P. (2000). Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. The Lancet, 355(9205), 735-740. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140673600010345.

- J. Hudson, P., & Souriau, C. (2003). Engineered antibodies. Nature medicine, 9(1), 129-134. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/nm0103-129.

- Moran, T.M., Usuba, O., Kuzu, H., Kuzu, Y., Schulman, J., & Bona, C. A. (1991). Inhibition of multicycle influenza virus replication by hybrid antibody-directed cytotoxic T cell lysis. The journal of immunology, 146(1), 321-326. Available online: https://www.jimmunol.org/content/146/1/321.short.

- ZAGHOUANI, H., RALPH, S., NONACS, R., SHAH, H., WALTER, G., & CONSTANTIN, B. (1993). Presentation of a viral T cell epitope expressed in the CDR3 region of a self immunoglobulin molecule. Science, 259(5092), 224-227. Available online: https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.7678469.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).