Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Glycosaminoglyans

Creating a Prothrombotic Surface

Damaged Cell Membranes Can Interact with Various Circulating Inflammatory Molecules

Cellular Senescence

Decaying Cells Can Break Down into Smaller and Smaller Fragments and Micropartices/Microvesicles That Become Prothrombotic Seeding Areas

Microclots Are Not ‘Just’ Microparticles

- Number. Microparticles of the above size range can be present in plasma in very large numbers, values quoted ranging from 8.106 to 4.109 /mL 120; ~3.106 /mL has been stated just for platelet-derived microparticles [131]. Orozco and coworkers found ~108 microparticles /mL [132], Albert and co-workers over 106 /mL [133] and Chandler and coworkers, numbers from 3.106 to 108 /mL [120]. By contrast, microclots greater than 1 μm in equivalent diameter are commonly present in numbers with a median below 1000 /mL [129] and a maximum value around 6.105 /mL, even in pathological conditions.

- Composition. The composition of microparticles simply reflects the composition of the cells from which they originate, and these cellular origins typically include platelets [117,134,135]. erythrocytes [136], leukocytes [137,138], and endothelial cells [138,139,140,141]. Unsurprisingly, their origin affects their thrombotic potential [117,142,143,144] as well as reflecting the diseases with which they are associated [145,146]. We note too the possibility that nanoplastics may also contribute to a pathological microparticle burden [147,148] as they themselves are amyloidogenic [149]. The same issues pertain for similarly sized particulate matter ingested via air pollution (e.g., [150,151]). Importantly, because these items are essentially insoluble they too can contribute to the blockage of the microcirculation that underpins so much of the pathology of fibrinaloid microclots. However, microparticles themselves are not specifically enriched in fibrin(ogen) albeit that they can bind it. We note that by contrast the fibrinaloid microclots are dominated by fibrin(ogen) subunits [152,153,154] and are significantly enriched in amyloidogenic proteins [155,156].

- Causality. It would seem that lipid microvesicles will bind fibrin(ogen) in microparticles but that actual clotting in the microclots traps other things, including microparticles. Consequently the order of adding fibrin in the two structures is opposite.

Biochemical Characteristics of Molecules That Can Associate with Decaying Membranes or Act as Prothrombotic Seeding Areas

A Healthy Circulation Avoids Uncontrolled SAA– or Fibrinogen–Receptor Binding

The Heterogeneity of Complex Hydrophobic, Amyloid-Containing Biological Structures, Including Lipofuscin, Atherosclerotic Plaques, and Fibrinaloid Microclot Complexes and Macroclots

Characterizing (Heterogenous) Prothrombotic Complexes

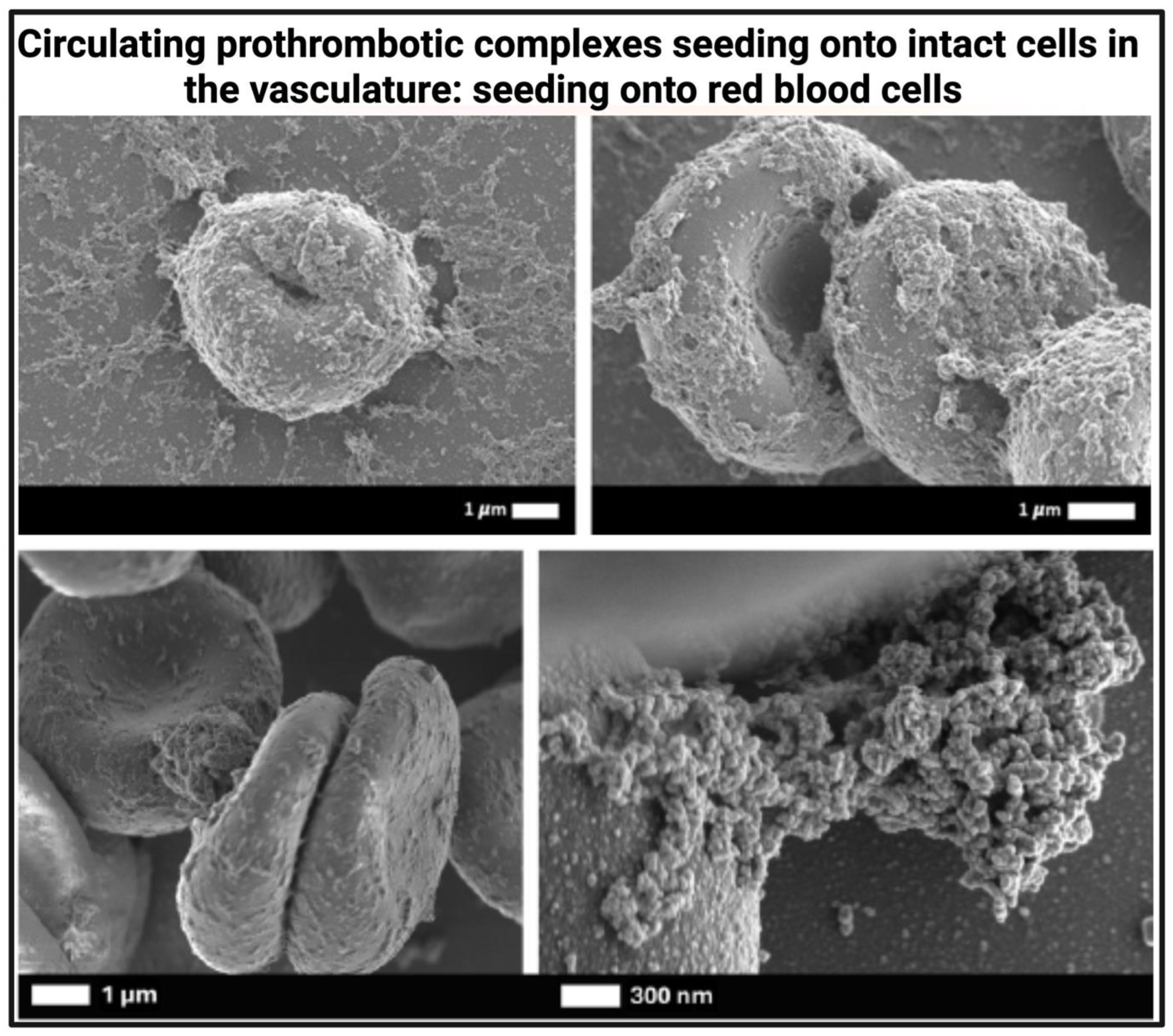

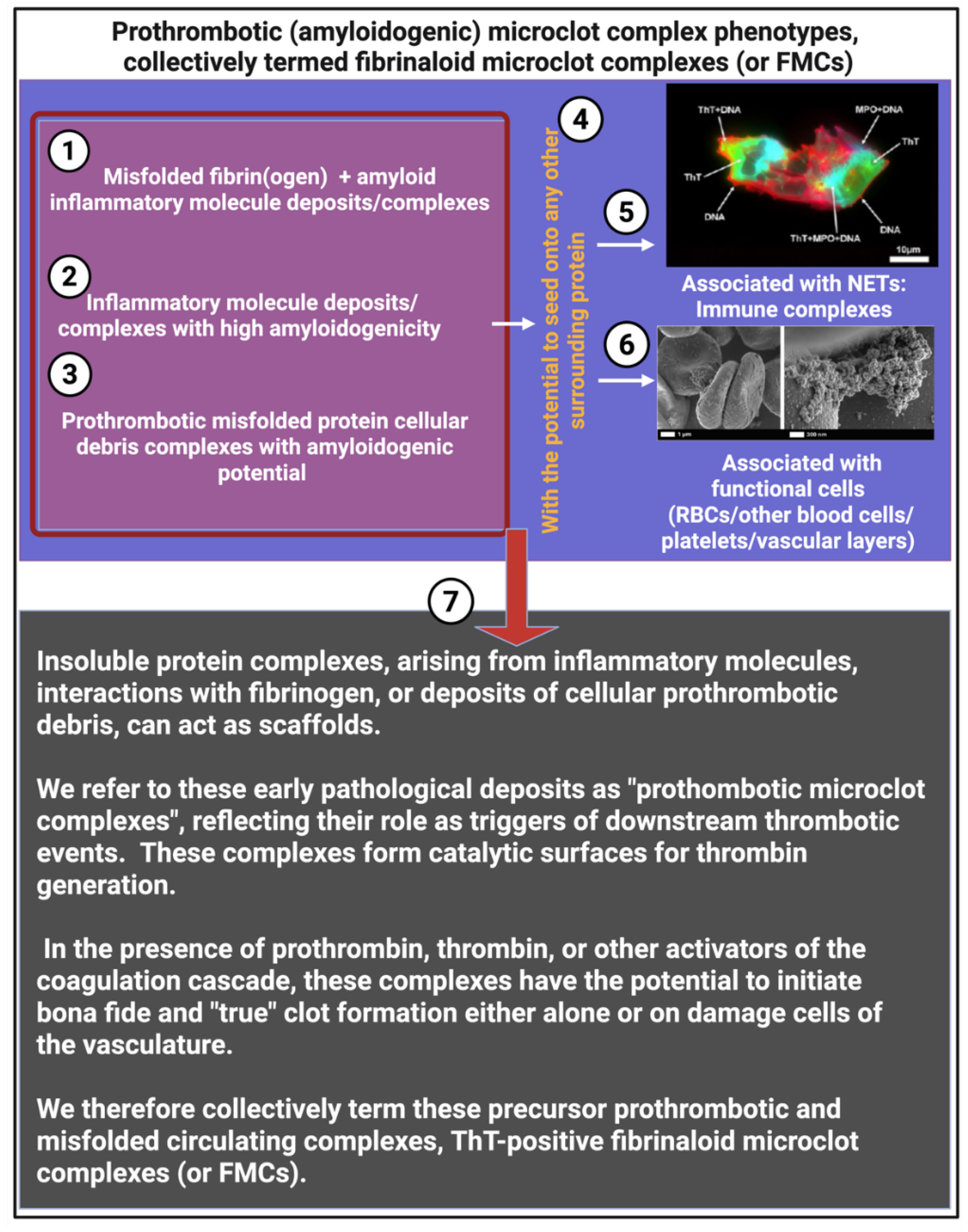

Summarising Our Thoughts on the Various Phenotypes of Circulating Prothrombotic Complexes (We Termed Fibrinaloid Microclot Complexes (FMCs)) May Drive Thrombo-Inflammation on β-Sheet Rich and Amyloidogenic Surfaces

- o Cell-derived debris

- o Subcellular vesicles and microparticles

- o Nucleoprotein immune complexes

- o Plasma protein aggregates associated with amyloidogenic inflammatory molecules

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaiser, R. , Gold, C., and Stark, K. (2025). Recent Advances in Immunothrombosis and Thromboinflammation. Thromb Haemost. [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, B. , and Massberg, S. (2013). Thrombosis as an intravascular effector of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 13, 34-45. [CrossRef]

- Almskog, L.M. , and Ågren, A. (2025). Thromboinflammation vs. immunothrombosis: strategies for overcoming anticoagulant resistance in COVID-19 and other hyperinflammatory diseases. Is ROTEM helpful or not? Front Immunol 16, 1599639. [CrossRef]

- Che, X. , Ranjan, A., Guo, C., Zhang, K., Goldsmith, R., Levine, S., Moneghetti, K.J., Zhai, Y., Ge, L., Mishra, N., et al. (2025). Heightened innate immunity may trigger chronic inflammation, fatigue and post-exertional malaise in ME/CFS. npj Metabolic Health and Disease 3, 34. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.A. , Travers, R.J., and Morrissey, J.H. (2015). How it all starts: Initiation of the clotting cascade. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 50, 326-336. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. , Chen, X., Gueydan, C., and Han, J. (2018). Plasma membrane changes during programmed cell deaths. Cell Research 28, 9-21. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. , Yu, C., Zhuang, J., Qi, W., Jiang, J., Liu, X., Zhao, W., Cao, Y., Wu, H., Qi, J., and Zhao, R.C. (2022). The role of phosphatidylserine on the membrane in immunity and blood coagulation. Biomarker Research 10, 4. [CrossRef]

- Zha, D. , Wang, S., Monaghan-Nichols, P., Qian, Y., Sampath, V., and Fu, M. (2023). Mechanisms of Endothelial Cell Membrane Repair: Progress and Perspectives. Cells 12. [CrossRef]

- Dejana, E. , Tournier-Lasserve, E., and Weinstein, B.M. (2009). The Control of Vascular Integrity by Endothelial Cell Junctions: Molecular Basis and Pathological Implications. Developmental Cell 16, 209-221. [CrossRef]

- Zwaal, R.F., and Schroit, A.J. (1997). Pathophysiologic implications of membrane phospholipid asymmetry in blood cells. Blood 89, 1121–1132. [CrossRef]

- Kell, D.B. (2021). The Transporter-Mediated Cellular Uptake and Efflux of Pharmaceutical Drugs and Biotechnology Products: How and Why Phospholipid Bilayer Transport Is Negligible in Real Biomembranes. Molecules 26. [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, A.D., and Engelman, D.M. (2008). Protein area occupancy at the center of the red blood cell membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, 2848–2852. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.-H. , Javanainen, M., Martinez-Seara, H., Metzler, R., and Vattulainen, I. (2016). Protein Crowding in Lipid Bilayers Gives Rise to Non-Gaussian Anomalous Lateral Diffusion of Phospholipids and Proteins. Physical Review X 6, 021006. [CrossRef]

- Alberts, B. , Heald, R., Johnson, A., Morgan, D., Raff, M., Roberts, K., & Walter, P. (2022). Molecular Biology of the Cell. 7th Edition (Garland Science). https://wwnorton.com/books/9780393884821.

- Aman, J. , and Margadant, C. (2023). Integrin-Dependent Cell-Matrix Adhesion in Endothelial Health and Disease. Circ Res 132, 355-378. [CrossRef]

- Čopič, A. , Dieudonné, T., and Lenoir, G. (2023). Phosphatidylserine transport in cell life and death. Curr Opin Cell Biol 83, 102192. [CrossRef]

- Nagata, S. , Suzuki, J., Segawa, K., and Fujii, T. (2016). Exposure of phosphatidylserine on the cell surface. Cell Death & Differentiation 23, 952-961. [CrossRef]

- Dal Col, J. , Lamberti, M.J., Nigro, A., Casolaro, V., Fratta, E., Steffan, A., and Montico, B. (2022). Phospholipid scramblase 1: a protein with multiple functions via multiple molecular interactors. Cell Communication and Signaling 20, 78. [CrossRef]

- Millington-Burgess, S.L. , and Harper, M.T. (2022). Maintaining flippase activity in procoagulant platelets is a novel approach to reducing thrombin generation. J Thromb Haemost 20, 989-995. [CrossRef]

- Filep, J.G. (2023). Two to tango: endothelial cell TMEM16 scramblases drive coagulation and thrombosis. J Clin Invest 133. [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, A. , Alfhili, M.A., Alsughayyir, J., Attanzio, A., Al Mamun Bhuyan, A., Bukowska, B., Cilla, A., Quintanar-Escorza, M.A., Föller, M., Havranek, O., et al. (2025). Current understanding of eryptosis: mechanisms, physiological functions, role in disease, pharmacological applications, and nomenclature recommendations. Cell Death & Disease 16, 467. [CrossRef]

- Lentz, B.R. (2003). Exposure of platelet membrane phosphatidylserine regulates blood coagulation. Progress in Lipid Research 42, 423-438. [CrossRef]

- Mizuguchi, C. , Nakamura, M., Kurimitsu, N., Ohgita, T., Nishitsuji, K., Baba, T., Shigenaga, A., Shimanouchi, T., Okuhira, K., Otaka, A., and Saito, H. (2018). Effect of Phosphatidylserine and Cholesterol on Membrane-mediated Fibril Formation by the N-terminal Amyloidogenic Fragment of Apolipoprotein A-I. Scientific Reports 8, 5497. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.J. (2023). Electrostatic switch mechanisms of membrane protein trafficking and regulation. Biophys Rev 15, 1967-1985. [CrossRef]

- Calianese, D.C. , and Birge, R.B. (2020). Biology of phosphatidylserine (PS): basic physiology and implications in immunology, infectious disease, and cancer. Cell Communication and Signaling 18, 41. [CrossRef]

- Hipp, M.S. , Kasturi, P., and Hartl, F.U. (2019). The proteostasis network and its decline in ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20, 421-435. [CrossRef]

- Koklic, T. , Majumder, R., Weinreb, G.E., and Lentz, B.R. (2009). Factor XA binding to phosphatidylserine-containing membranes produces an inactive membrane-bound dimer. Biophys J 97, 2232-2241. [CrossRef]

- Carman, C.V. , Nikova, D.N., Sakurai, Y., Shi, J., Novakovic, V.A., Rasmussen, J.T., Lam, W.A., and Gilbert, G.E. (2023). Membrane curvature and PS localize coagulation proteins to filopodia and retraction fibers of endothelial cells. Blood Adv 7, 60-72. [CrossRef]

- Banjade, S. , and Rosen, M.K. (2014). Phase transitions of multivalent proteins can promote clustering of membrane receptors. Elife 3. [CrossRef]

- Li, L. , Hu, J., Różycki, B., Ji, J., and Song, F. (2022). Interplay of receptor-ligand binding and lipid domain formation during cell adhesion. Front Mol Biosci 9, 1019477. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H. , Meng, X.W., Flatten, K.S., Loegering, D.A., and Kaufmann, S.H. (2013). Phosphatidylserine exposure during apoptosis reflects bidirectional trafficking between plasma membrane and cytoplasm. Cell Death & Differentiation 20, 64-76. [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.W. , and Takatsu, H. (2020). Phosphatidylserine exposure in living cells. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 55, 166-178. [CrossRef]

- Birge, R.B. , Boeltz, S., Kumar, S., Carlson, J., Wanderley, J., Calianese, D., Barcinski, M., Brekken, R.A., Huang, X., Hutchins, J.T., et al. (2016). Phosphatidylserine is a global immunosuppressive signal in efferocytosis, infectious disease, and cancer. Cell Death Differ 23, 962-978. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, E.C. , and Rand, M.L. (2020). Procoagulant Phosphatidylserine-Exposing Platelets in vitro and in vivo. Front Cardiovasc Med 7, 15. [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y. , Guo, H., Zhang, Y., and Qiao, R. (2021). Procoagulant platelets: Generation, characteristics, and therapeutic target. J Clin Lab Anal 35, e23750. [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, A. , Tasneem, S., and Hayward, C.P.M. (2022). Update on platelet procoagulant mechanisms in health and in bleeding disorders. Int J Lab Hematol 44 Suppl 1, 89-100. [CrossRef]

- Park, S. , and Park, J.K. (2024). Back to basics: the coagulation pathway. Blood Res 59, 35. [CrossRef]

- Segawa, K. , and Nagata, S. (2015). An Apoptotic ‘Eat Me’ Signal: Phosphatidylserine Exposure. Trends in Cell Biology 25, 639-650. [CrossRef]

- Tschirhart, B.J. , Lu, X., Gomes, J., Chandrabalan, A., Bell, G., Hess, D.A., Xing, G., Ling, H., Burger, D., and Feng, Q. (2023). Annexin A5 Inhibits Endothelial Inflammation Induced by Lipopolysaccharide-Activated Platelets and Microvesicles via Phosphatidylserine Binding. Pharmaceuticals 16, 837.

- Muller, M.P. , Wang, Y., Morrissey, J.H., and Tajkhorshid, E. (2017). Lipid specificity of the membrane binding domain of coagulation factor X. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 15, 2005-2016. [CrossRef]

- Wan, P. , Choksi, S., Park, Y.J., Chen, X., Yan, J., Foroutannejad, S., Liu, Z., Chen, J., Lake, R., Liu, C., and Liu, Z.G. (2025). Soluble tissue factor generated by necroptosis-triggered shedding is responsible for thrombosis. Cell Res. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.A. , Pendurthi, U.R., Sen, P., and Rao, L.V. (2016). The Role of Putative Phosphatidylserine-Interactive Residues of Tissue Factor on Its Coagulant Activity at the Cell Surface. PLoS One 11, e0158377. [CrossRef]

- Spronk, H.M. , ten Cate, H., and van der Meijden, P.E. (2014). Differential roles of tissue factor and phosphatidylserine in activation of coagulation. Thromb Res 133 Suppl 1, S54-56. [CrossRef]

- El Masri, R. , Crétinon, Y., Gout, E., and Vivès, R.R. (2020). HS and Inflammation: A Potential Playground for the Sulfs? Front Immunol 11, 570. [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, B.L. , Lord, M.S., Melrose, J., and Whitelock, J.M. (2018). The Role of Heparan Sulfate in Inflammation, and the Development of Biomimetics as Anti-Inflammatory Strategies. J Histochem Cytochem 66, 321-336. [CrossRef]

- Cripps, J.G. , Crespo, F.A., Romanovskis, P., Spatola, A.F., and Fernández-Botrán, R. (2005). Modulation of acute inflammation by targeting glycosaminoglycan–cytokine interactions. International Immunopharmacology 5, 1622-1632. [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, A.I.S., Pitt, S.J., and Stewart, A.J. (2018). Glycosaminoglycan Neutralization in Coagulation Control. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 38, 1258–1270. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milusev, A. , Despont, A., Shaw, J., Rieben, R., and Sorvillo, N. (2023). Inflammatory stimuli induce shedding of heparan sulfate from arterial but not venous porcine endothelial cells leading to differential proinflammatory and procoagulant responses. Scientific Reports 13, 4483. [CrossRef]

- Lever, R. , Smailbegovic, A., and Page, C. (2001). Role of glycosaminoglycans in inflammation. InflammoPharmacology 9, 165-169. [CrossRef]

- Lietha, D. , and Izard, T. (2020). Roles of Membrane Domains in Integrin-Mediated Cell Adhesion. Int J Mol Sci 21. [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, J.H. , Davis-Harrison, R.L., Tavoosi, N., Ke, K., Pureza, V., Boettcher, J.M., Clay, M.C., Rienstra, C.M., Ohkubo, Y.Z., Pogorelov, T.V., and Tajkhorshid, E. (2010). Protein-phospholipid interactions in blood clotting. Thromb Res 125 Suppl 1, S23-25. [CrossRef]

- Medfisch, S.M. , Muehl, E.M., Morrissey, J.H., and Bailey, R.C. (2020). Phosphatidylethanolamine-phosphatidylserine binding synergy of seven coagulation factors revealed using Nanodisc arrays on silicon photonic sensors. Sci Rep 10, 17407. [CrossRef]

- Schreuder, M. , Reitsma, P.H., and Bos, M.H.A. (2019). Blood coagulation factor Va’s key interactive residues and regions for prothrombinase assembly and prothrombin binding. J Thromb Haemost 17, 1229-1239. [CrossRef]

- Bradford, H.N. , Orcutt, S.J., and Krishnaswamy, S. (2013). Membrane binding by prothrombin mediates its constrained presentation to prothrombinase for cleavage. J Biol Chem 288, 27789-27800. [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.Y. , Lee, C.J., Wu, S., and Pedersen, L.G. (2015). A model for the unique role of factor Va A2 domain extension in the human ternary thrombin-generating complex. Biophys Chem 199, 46-50. [CrossRef]

- Weisel, J.W. , and Litvinov, R.I. (2013). Mechanisms of fibrin polymerization and clinical implications. Blood 121, 1712-1719. [CrossRef]

- Kattula, S. , Byrnes, J.R., and Wolberg, A.S. (2017). Fibrinogen and Fibrin in Hemostasis and Thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 37, e13-e21. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , Carrim, N., and Ni, H. (2015). Fibronectin orchestrates thrombosis and hemostasis. Oncotarget 6, 19350-19351. [CrossRef]

- Cho, J. , and Mosher, D.F. (2006). Enhancement of thrombogenesis by plasma fibronectin cross-linked to fibrin and assembled in platelet thrombi. Blood 107, 3555-3563. [CrossRef]

- Ni, H. , Yuen, P.S., Papalia, J.M., Trevithick, J.E., Sakai, T., Fässler, R., Hynes, R.O., and Wagner, D.D. (2003). Plasma fibronectin promotes thrombus growth and stability in injured arterioles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 2415-2419. [CrossRef]

- Wirth, F. , Lubosch, A., Hamelmann, S., and Nakchbandi, I.A. (2020). Fibronectin and Its Receptors in Hematopoiesis. Cells 9. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J. , Thomson, G.J.A., Nunes, J.M., Engelbrecht, A.M., Nell, T.A., de Villiers, W.J.S., de Beer, M.C., Engelbrecht, L., Kell, D.B., and Pretorius, E. (2019). Serum amyloid A binds to fibrin(ogen), promoting fibrin amyloid formation. Sci Rep 9, 3102. [CrossRef]

- Papareddy, P. , and Herwald, H. (2025). From immune activation to disease progression: Unraveling the complex role of Serum Amyloid A proteins. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 83, 77-84. [CrossRef]

- Abouelasrar Salama, S. , Gouwy, M., Van Damme, J., and Struyf, S. (2021). The turning away of serum amyloid A biological activities and receptor usage. Immunology 163, 115-127. [CrossRef]

- Kam, P.C. , and Egan, M.K. (2002). Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists: pharmacology and clinical developments. Anesthesiology 96, 1237-1249. [CrossRef]

- Urieli-Shoval, S. , Shubinsky, G., Linke, R.P., Fridkin, M., Tabi, I., and Matzner, Y. (2002). Adhesion of human platelets to serum amyloid A. Blood 99, 1224-1229. [CrossRef]

- Kahner, B.N. , Kato, H., Banno, A., Ginsberg, M.H., Shattil, S.J., and Ye, F. (2012). Kindlins, integrin activation and the regulation of talin recruitment to αIIbβ3. PLoS One 7, e34056. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.Q., Qin, J., and Plow, E.F. (2007). Platelet integrin αIIbβ3: activation mechanisms. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 5, 1345-1352. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C. , Ward, N.L., Rice, M., Ball, N.J., Walle, P., Najdek, C., Kilinc, D., Lambert, J.C., Chapuis, J., and Goult, B.T. (2024). The structure of an amyloid precursor protein/talin complex indicates a mechanical basis of Alzheimer’s disease. Open Biol 14, 240185. [CrossRef]

- Gouwy, M. , De Buck, M., Abouelasrar Salama, S., Vandooren, J., Knoops, S., Pörtner, N., Vanbrabant, L., Berghmans, N., Opdenakker, G., Proost, P., et al. (2018). Matrix Metalloproteinase-9-Generated COOH-, but Not NH(2)-Terminal Fragments of Serum Amyloid A1 Retain Potentiating Activity in Neutrophil Migration to CXCL8, With Loss of Direct Chemotactic and Cytokine-Inducing Capacity. Front Immunol 9, 1081. [CrossRef]

- De Buck, M. , Berghmans, N., Pörtner, N., Vanbrabant, L., Cockx, M., Struyf, S., Opdenakker, G., Proost, P., Van Damme, J., and Gouwy, M. (2015). Serum amyloid A1α induces paracrine IL-8/CXCL8 via TLR2 and directly synergizes with this chemokine via CXCR2 and formyl peptide receptor 2 to recruit neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol 98, 1049-1060. [CrossRef]

- Lind, S. , Sundqvist, M., Holmdahl, R., Dahlgren, C., Forsman, H., and Olofsson, P. (2019). Functional and signaling characterization of the neutrophil FPR2 selective agonist Act-389949. Biochem Pharmacol 166, 163-173. [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, S. , Urdaneta, A., Bullitt, E., Fändrich, M., and Gursky, O. (2023). Lipid clearance and amyloid formation by serum amyloid A: exploring the links between beneficial and pathologic actions of an enigmatic protein. J Lipid Res 64, 100429. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. , Li, X., Shi, X., Zhu, M., Wang, J., Huang, S., Huang, X., Wang, H., Li, L., Deng, H., et al. (2019). Platelet integrin αIIbβ3: signal transduction, regulation, and its therapeutic targeting. J Hematol Oncol 12, 26. [CrossRef]

- Zou, J. , Swieringa, F., de Laat, B., de Groot, P.G., Roest, M., and Heemskerk, J.W.M. (2022). Reversible Platelet Integrin αIIbβ3 Activation and Thrombus Instability. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, 12512.

- Al-Yafeai, Z., Pearson, B.H., Peretik, J.M., Cockerham, E.D., Reeves, K.A., Bhattarai, U., Wang, D., Petrich, B.G., and Orr, A.W. (2021). Integrin affinity modulation critically regulates atherogenic endothelial activation in vitro and in vivo. Matrix Biology 96, 87-103. [CrossRef]

- van Buul, J.D. , van Rijssel, J., van Alphen, F.P., van Stalborch, A.M., Mul, E.P., and Hordijk, P.L. (2010). ICAM-1 clustering on endothelial cells recruits VCAM-1. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010, 120328. [CrossRef]

- Suehiro, K. , Gailit, J., and Plow, E.F. (1997). Fibrinogen Is a Ligand for Integrin α5β1 on Endothelial Cells*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 272, 5360-5366. [CrossRef]

- Mosesson, M.W. (2005). Fibrinogen and fibrin structure and functions. J Thromb Haemost 3, 1894-1904. [CrossRef]

- Semenov, A.N. , Lugovtsov, A.E., Shirshin, E.A., Yakimov, B.P., Ermolinskiy, P.B., Bikmulina, P.Y., Kudryavtsev, D.S., Timashev, P.S., Muravyov, A.V., Wagner, C., et al. (2020). Assessment of Fibrinogen Macromolecules Interaction with Red Blood Cells Membrane by Means of Laser Aggregometry, Flow Cytometry, and Optical Tweezers Combined with Microfluidics. Biomolecules 10. [CrossRef]

- Moon, B. , Yang, S., Moon, H., Lee, J., and Park, D. (2023). After cell death: the molecular machinery of efferocytosis. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 55, 1644-1651. [CrossRef]

- Arandjelovic, S. , and Ravichandran, K.S. (2015). Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in homeostasis. Nature Immunology 16, 907-917. [CrossRef]

- Fadeel, B. , Xue, D., and Kagan, V. (2010). Programmed cell clearance: molecular regulation of the elimination of apoptotic cell corpses and its role in the resolution of inflammation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 396, 7-10. [CrossRef]

- Hari-Dass, R. , Shah, C., Meyer, D.J., and Raynes, J.G. (2005). Serum amyloid A protein binds to outer membrane protein A of gram-negative bacteria. J Biol Chem 280, 18562-18567. [CrossRef]

- Bryckaert, M. , Rosa, J.P., Denis, C.V., and Lenting, P.J. (2015). Of von Willebrand factor and platelets. Cell Mol Life Sci 72, 307-326. [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, S. , Gantz, D.L., Haupt, C., and Gursky, O. (2017). Serum amyloid A forms stable oligomers that disrupt vesicles at lysosomal pH and contribute to the pathogenesis of reactive amyloidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, E6507-e6515. [CrossRef]

- Nady, A. , Reichheld, S.E., and Sharpe, S. (2024). Structural studies of a serum amyloid A octamer that is primed to scaffold lipid nanodiscs. Protein Sci 33, e4983. [CrossRef]

- Westermark, G.T. , Fändrich, M., Lundmark, K., and Westermark, P. (2018). Noncerebral Amyloidoses: Aspects on Seeding, Cross-Seeding, and Transmission. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 8. [CrossRef]

- van Genderen, H.O. , Kenis, H., Hofstra, L., Narula, J., and Reutelingsperger, C.P.M. (2008). Extracellular annexin A5: Functions of phosphatidylserine-binding and two-dimensional crystallization. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1783, 953-963. [CrossRef]

- Leventis, P.A. , and Grinstein, S. (2010). The distribution and function of phosphatidylserine in cellular membranes. Annu Rev Biophys 39, 407-427. [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, M. , Aguilar, M., Thorin, E., Ferbeyre, G., and Nattel, S. (2022). The role of cellular senescence in cardiac disease: basic biology and clinical relevance. Nature Reviews Cardiology 19, 250-264. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, V. , Paldino, G., Kunkl, M., Paroli, M., Sorrentino, R., Tuosto, L., and Fiorillo, M.T. (2022). CD8+ T Cell Senescence: Lights and Shadows in Viral Infections, Autoimmune Disorders and Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, 3374.

- Narasimhan, A., Flores, R.R., Robbins, P.D., and Niedernhofer, L.J. (2021). Role of cellular senescence in type II diabetes. Endocrinology 162, bqab136.

- Kell, L. , Simon, A.K., Alsaleh, G., and Cox, L.S. (2023). The central role of DNA damage in immunosenescence. Frontiers in Aging Volume 4 - 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gioia, U. , Tavella, S., Martínez-Orellana, P., Cicio, G., Colliva, A., Ceccon, M., Cabrini, M., Henriques, A.C., Fumagalli, V., and Paldino, A. (2023). SARS-CoV-2 infection induces DNA damage, through CHK1 degradation and impaired 53BP1 recruitment, and cellular senescence. Nature Cell Biology 25, 550-564.

- Yang, L. , Kim, T.W., Han, Y., Nair, M.S., Harschnitz, O., Zhu, J., Wang, P., Koo, S.Y., Lacko, L.A., and Chandar, V. (2024). SARS-CoV-2 infection causes dopaminergic neuron senescence. Cell Stem Cell 31, 196-211. e196.

- Nunes, M. , Kell, L., Slaghekke, A., Wüst, R., Fielding, B., Kell, D., and Pretorius, E. (2025). Virus-Induced Endothelial Senescence as a Cause and Driving Factor for ME/CFS and Long COVID: Mediated by a Dysfunctional Immune System.

- Lin, Y. , Postma, D., Steeneken, L., Melo dos Santos, L., Kirkland, J., Espindola-Netto, J., Tchkonia, T., Borghesan, M., Bouma, H., and Demaria, M. (2023). Circulating monocytes expressing senescence-associated features are enriched in COVID-19 patients with severe disease. Aging Cell 22, e14011.

- Berentschot, J.C. , Drexhage, H.A., Aynekulu Mersha, D.G., Wijkhuijs, A.J., GeurtsvanKessel, C.H., Koopmans, M.P., Voermans, J.J., Hendriks, R.W., Nagtzaam, N.M., and de Bie, M. (2023). Immunological profiling in long COVID: overall low grade inflammation and T-lymphocyte senescence and increased monocyte activation correlating with increasing fatigue severity. Frontiers in immunology 14, 1254899.

- Ohtani, N. (2022). The roles and mechanisms of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP): can it be controlled by senolysis? Inflammation and regeneration 42, 11.

- Suelves, N. , Saleki, S., Ibrahim, T., Palomares, D., Moonen, S., Koper, M.J., Vrancx, C., Vadukul, D.M., Papadopoulos, N., Viceconte, N., et al. (2023). Senescence-related impairment of autophagy induces toxic intraneuronal amyloid-β accumulation in a mouse model of amyloid pathology. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 11, 82. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. , Yi, C., Qi, J., Cui, X., Yuan, X., Deng, W., Chen, M., and Xu, H. (2025). Senescence Alters Antimicrobial Peptide Expression and Induces Amyloid-β Production in Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. Aging cell 24, e70161.

- Ungerleider, K. , Beck, J.A., Lissa, D., Joruiz, S., Horikawa, I., and Harris, C.C. (2022). Δ133p53α protects human astrocytes from amyloid-beta induced senescence and neurotoxicity. Neuroscience 498, 190-202.

- Flanary, B.E., Sammons, N.W., Nguyen, C., Walker, D., and Streit, W.J. (2007). Evidence that aging and amyloid promote microglial cell senescence. Rejuvenation research 10, 61-74.

- Sun, L. , Wang, L., Ye, K.X., Wang, S., Zhang, R., Juan, Z., Feng, L., and Min, S. (2023). Endothelial glycocalyx in aging and age-related diseases. Aging and disease 14, 1606.

- McConnell, M.J., Kostallari, E., Ibrahim, S.H., and Iwakiri, Y. (2023). The evolving role of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells in liver health and disease. Hepatology 78, 649-669.

- Seki, M., Arashiki, N., Takakuwa, Y., Nitta, K., and Nakamura, F. (2020). Reduction in flippase activity contributes to surface presentation of phosphatidylserine in human senescent erythrocytes. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 24, 13991-14000.

- Wi, J.H. , Heo, C.H., Gwak, H., Jung, C., and Kim, S.Y. (2021). Probing Physical Properties of the Cellular Membrane in Senescent Cells by Fluorescence Imaging. J Phys Chem B 125, 10182-10194. [CrossRef]

- Picos, A. , Seoane, N., Campos-Toimil, M., and Viña, D. (2025). Vascular senescence and aging: mechanisms, clinical implications, and therapeutic prospects. Biogerontology 26, 118. [CrossRef]

- Bochenek, M.L. , Schütz, E., and Schäfer, K. (2016). Endothelial cell senescence and thrombosis: Ageing clots. Thrombosis research 147, 36-45.

- Dasgupta, S.K., Argaiz, E.R., Mercado, J.E.C., Maul, H.O.E., Garza, J., Enriquez, A.B., Abdel-Monem, H., Prakasam, A., Andreeff, M., and Thiagarajan, P. (2010). Platelet senescence and phosphatidylserine exposure. Transfusion 50, 2167-2175.

- Curtis, A.M. , Edelberg, J., Jonas, R., Rogers, W.T., Moore, J.S., Syed, W., and Mohler, E.R. (2013). Endothelial microparticles: Sophisticated vesicles modulating vascular function. Vascular Medicine 18, 204-214. [CrossRef]

- Deng, F. , Wang, S., and Zhang, L. (2017). Endothelial microparticles act as novel diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers of circulatory hypoxia-related diseases: a literature review. J Cell Mol Med 21, 1698-1710. [CrossRef]

- Haghbin, M. , Sotoodeh Jahromi, A., Hashemi Tayer, A., and Ghasemi Nejad, Z. (2025). The Potential Clinical Relevance of Procoagulant Microparticles as Biomarkers of Blood Coagulation in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 26, 23-32. [CrossRef]

- Aung, H.H. , Tung, J.-P., Dean, M.M., Flower, R.L., and Pecheniuk, N.M. (2017). Procoagulant role of microparticles in routine storage of packed red blood cells: potential risk for prothrombotic post-transfusion complications. Pathology 49, 62-69. [CrossRef]

- Zubairova, L.D. , Nabiullina, R.M., Nagaswami, C., Zuev, Y.F., Mustafin, I.G., Litvinov, R.I., and Weisel, J.W. (2015). Circulating Microparticles Alter Formation, Structure and Properties of Fibrin Clots. Scientific Reports 5, 17611. [CrossRef]

- Aleman, M.M. , Gardiner, C., Harrison, P., and Wolberg, A.S. (2011). Differential contributions of monocyte- and platelet-derived microparticles towards thrombin generation and fibrin formation and stability. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 9, 2251-2261. [CrossRef]

- Owens, A.P. , 3rd, and Mackman, N. (2011). Microparticles in hemostasis and thrombosis. Circ Res 108, 1284-1297. [CrossRef]

- Merten, M. , Pakala, R., Thiagarajan, P., and Benedict, C.R. (1999). Platelet microparticles promote platelet interaction with subendothelial matrix in a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa-dependent mechanism. Circulation 99, 2577-2582. [CrossRef]

- Chandler, W.L. , Yeung, W., and Tait, J.F. (2011). A new microparticle size calibration standard for use in measuring smaller microparticles using a new flow cytometer. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 9, 1216-1224. [CrossRef]

- Zwicker, J.I. , Lacroix, R., Dignat-George, F., Furie, B.C., and Furie, B. (2012). Measurement of platelet microparticles. Methods Mol Biol 788, 127-139. [CrossRef]

- Bergaglio, T. , Synhaivska, O., and Nirmalraj, P.N. (2023). Digital holo-tomographic 3D maps of COVID-19 microclots in blood to assess disease severity. bioRxiv, 2023.2009.2012.557318. [CrossRef]

- Reid, V.L., and Webster, N.R. (2012). Role of microparticles in sepsis. British Journal of Anaesthesia 109, 503-513. [CrossRef]

- Burnouf, T. , Chou, M.-L., Goubran, H., Cognasse, F., Garraud, O., and Seghatchian, J. (2015). An overview of the role of microparticles/microvesicles in blood components: Are they clinically beneficial or harmful? Transfusion and Apheresis Science 53, 137-145. [CrossRef]

- Braga-Lagache, S. , Buchs, N., Iacovache, M.-I., Zuber, B., Jackson, C.B., and Heller, M. (2016). Robust Label-free, Quantitative Profiling of Circulating Plasma Microparticle (MP) Associated Proteins*. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 15, 3640-3652. [CrossRef]

- Zwicker, J.I. , Trenor, C.C., Furie, B.C., and Furie, B. (2011). Tissue Factor–Bearing Microparticles and Thrombus Formation. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 31, 728-733. [CrossRef]

- Nieri, D. , Neri, T., Petrini, S., Vagaggini, B., Paggiaro, P., and Celi, A. Cell-derived microparticles and the lung. European Respiratory Review 25, 266-277. [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R., and LeBleu, V.S. (2020). The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 367, eaau6977. [CrossRef]

- Turner, S. , Laubscher, G.J., Khan, M.A., Kell, D.B., and Pretorius, E. (2023). Accelerating discovery: A novel flow cytometric method for detecting fibrin(ogen) amyloid microclots using long COVID as a model. Heliyon 9. [CrossRef]

- Kell, D.B. , Laubscher, G.J., and Pretorius, E. (2022). A central role for amyloid fibrin microclots in long COVID/PASC: origins and therapeutic implications. Biochemical Journal 479, 537-559. [CrossRef]

- Cointe, S. , Judicone, C., Robert, S., Mooberry, M.J., Poncelet, P., Wauben, M., Nieuwland, R., Key, N.S., Dignat-George, F., and Lacroix, R. (2017). Standardization of microparticle enumeration across different flow cytometry platforms: results of a multicenter collaborative workshop. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 15, 187-193. [CrossRef]

- Orozco, A.F. , and Lewis, D.E. (2010). Flow cytometric analysis of circulating microparticles in plasma. Cytometry A 77, 502-514. [CrossRef]

- Albert, V. , Subramanian, A., and Pati, H.P. (2018). Correlation of Circulating Microparticles with Coagulation and Fibrinolysis Is Healthy Individuals. Blood 132, 4975-4975. [CrossRef]

- Burnier, L. , Fontana, P., Kwak, B.R., and Angelillo-Scherrer, A. (2009). Cell-derived microparticles in haemostasis and vascular medicine. Thromb Haemost 101, 439-451.

- Rank, A. , Nieuwland, R., Delker, R., Köhler, A., Toth, B., Pihusch, V., Wilkowski, R., and Pihusch, R. (2010). Cellular origin of platelet-derived microparticles in vivo. Thrombosis Research 126, e255-e259. [CrossRef]

- Westerman, M. , and Porter, J.B. (2016). Red blood cell-derived microparticles: An overview. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases 59, 134-139. [CrossRef]

- Angelillo-Scherrer, A. , Weber, C., and Mause, S. (2012). Leukocyte-Derived Microparticles in Vascular Homeostasis. Circulation Research 110, 356-369. [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, R. , Plawinski, L., Robert, S., Doeuvre, L., Sabatier, F., Martinez de Lizarrondo, S., Mezzapesa, A., Anfosso, F., Leroyer, A.S., Poullin, P., et al. (2012). Leukocyte- and endothelial-derived microparticles: a circulating source for fibrinolysis. Haematologica 97, 1864-1872. [CrossRef]

- Chironi, G.N. , Boulanger, C.M., Simon, A., Dignat-George, F., Freyssinet, J.-M., and Tedgui, A. (2009). Endothelial microparticles in diseases. Cell and Tissue Research 335, 143-151. [CrossRef]

- Dignat-George, F., and Boulanger, C.M. (2011). The Many Faces of Endothelial Microparticles. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 31, 27-33. [CrossRef]

- Horstman, L.L. , Jy, W., Jimenez, J.J., and Ahn, Y.S. (2004). Endothelial microparticles as markers of endothelial dysfunction. FBL 9, 1118-1135. [CrossRef]

- Mege, D. , Crescence, L., Ouaissi, M., Sielezneff, I., Guieu, R., Dignat-George, F., Dubois, C., and Panicot-Dubois, L. (2017). Fibrin-bearing microparticles: marker of thrombo-embolic events in pancreatic and colorectal cancers. Oncotarget 8.

- Chou, J. , Mackman, N., Merrill-Skoloff, G., Pedersen, B., Furie, B.C., and Furie, B. (2004). Hematopoietic cell-derived microparticle tissue factor contributes to fibrin formation during thrombus propagation. Blood 104, 3190-3197. [CrossRef]

- Agouti, I., Cointe, S., Robert, S., Judicone, C., Loundou, A., Driss, F., Brisson, A., Steschenko, D., Rose, C., Pondarré, C., et al. (2015). Platelet and not erythrocyte microparticles are procoagulant in transfused thalassaemia major patients. British Journal of Haematology 171, 615-624. [CrossRef]

- Nomura, S. , Ozaki, Y., and Ikeda, Y. (2008). Function and role of microparticles in various clinical settings. Thrombosis Research 123, 8-23. [CrossRef]

- Nomura, S. , Inami, N., Shouzu, A., Urase, F., and Maeda, Y. (2009). Correlation and association between plasma platelet-, monocyte- and endothelial cell-derived microparticles in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Platelets 20, 406-414. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, D. , and Chandrasekaran, N. (2023). Journey of micronanoplastics with blood components. RSC Advances 13, 31435-31459. [CrossRef]

- Kopatz, V. , Wen, K., Kovács, T., Keimowitz, A.S., Pichler, V., Widder, J., Vethaak, A.D., Hollóczki, O., and Kenner, L. (2023). Micro- and Nanoplastics Breach the Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB): Biomolecular Corona’s Role Revealed. Nanomaterials 13. [CrossRef]

- Bashirova, N. , Schölzel, F., Hornig, D., Scheidt, H.A., Krueger, M., Salvan, G., Huster, D., Matysik, J., and Alia, A. (2025). The Effect of Polyethylene Terephthalate Nanoplastics on Amyloid-β Peptide Fibrillation. Molecules 30, 1432.

- Zhang, Q. , Wang, Y., Xiao, Q., Geng, G., Davis, S.J., Liu, X., Yang, J., Liu, J., Huang, W., He, C., et al. (2025). Long-range PM2.5 pollution and health impacts from the 2023 Canadian wildfires. Nature 645, 672-678. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Liu, H., Wu, X., Jia, L., Gadhave, K., Wang, L., Zhang, K., Li, H., Chen, R., Kumbhar, R., et al. (2025). Lewy body dementia promotion by air pollutants. Science 389, eadu4132. [CrossRef]

- Kruger, A. , Vlok, M., Turner, S., Venter, C., Laubscher, G.J., Kell, D.B., and Pretorius, E. (2022). Proteomics of fibrin amyloid microclots in Long COVID/ Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) shows many entrapped pro-inflammatory molecules that may also contribute to a failed fibrinolytic system. Cardiovasc Diabetol 21, 190. [CrossRef]

- Schofield, J. , Abrams, S.T., Jenkins, R., Lane, S., Wang, G., and Toh, C.H. (2024). Amyloid-Fibrinogen Aggregates (“Microclots”) Predict Risks of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation and Mortality. Blood Adv. [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, E. , Vlok, M., Venter, C., Bezuidenhout, J.A., Laubscher, G.J., Steenkamp, J., and Kell, D.B. (2021). Persistent clotting protein pathology in Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin. Cardiovasc Diabetol 20, 172. [CrossRef]

- Kell, D.B. , and Pretorius, E. (2024). Proteomic Evidence for Amyloidogenic Cross-Seeding in Fibrinaloid Microclots. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, 10809.

- Kell, D.B. , and Pretorius, E. (2025). The Proteome Content of Blood Clots Observed Under Different Conditions: Successful Role in Predicting Clot Amyloid(ogenicity). Molecules 30, 668.

- Burdukiewicz, M. , Sobczyk, P., Rödiger, S., Duda-Madej, A., Mackiewicz, P., and Kotulska, M. (2017). Amyloidogenic motifs revealed by n-gram analysis. Sci Rep 7, 12961. [CrossRef]

- Bester, J. , Matshailwe, C., and Pretorius, E. (2018). Simultaneous presence of hypercoagulation and increased clot lysis time due to IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8. Cytokine 110, 237-242. [CrossRef]

- Bester, J. , and Pretorius, E. (2016). Effects of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 on erythrocytes, platelets and clot viscoelasticity. Sci Rep 6, 32188. [CrossRef]

- Sack, G.H. (2020). Serum Amyloid A (SAA) Proteins. Subcell Biochem 94, 421-436. [CrossRef]

- Bezuidenhout, J.A. , Venter, C., Roberts, T.J., Tarr, G., Kell, D.B., and Pretorius, E. (2020). Detection of Citrullinated Fibrin in Plasma Clots of Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients and Its Relation to Altered Structural Clot Properties, Disease-Related Inflammation and Prothrombotic Tendency. Front Immunol 11, 577523. [CrossRef]

- Turner, S. , Naidoo, C.A., Usher, T.J., Kruger, A., Venter, C., Laubscher, G.J., Khan, M.A., Kell, D.B., and Pretorius, E. (2023). Increased Levels of Inflammatory and Endothelial Biomarkers in Blood of Long COVID Patients Point to Thrombotic Endothelialitis. Semin Thromb Hemost. [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.J.E. , Venter, C., Roberts, T.J., Tarr, G., and Pretorius, E. (2021). Psoriatic disease is associated with systemic inflammation, endothelial activation, and altered haemostatic function. Sci Rep 11, 13043. [CrossRef]

- Randeria, S.N. , Thomson, G.J.A., Nell, T.A., Roberts, T., and Pretorius, E. (2019). Inflammatory cytokines in type 2 diabetes mellitus as facilitators of hypercoagulation and abnormal clot formation. Cardiovasc Diabetol 18, 72. [CrossRef]

- Westman, H. , Hammarström, P., and Nyström, S. (2025). SARS-CoV-2 spike protein amyloid fibrils impair fibrin formation and fibrinolysis. bioRxiv, 2025.2006.2030.661938. [CrossRef]

- Kell, D.B. , and Pretorius, E. (2017). Proteins behaving badly. Substoichiometric molecular control and amplification of the initiation and nature of amyloid fibril formation: lessons from and for blood clotting. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 123, 16-41. [CrossRef]

- Soria, J. , Mirshahi, S., Mirshahi, S.Q., Varin, R., Pritchard, L.L., Soria, C., and Mirshahi, M. (2019). Fibrinogen αC domain: Its importance in physiopathology. Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis 3, 173-183. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J. , and Dogan, A. (2019). Fibrinogen alpha amyloidosis: insights from proteomics. Expert Review of Proteomics 16, 783-793. [CrossRef]

- Yazaki, M. , Yoshinaga, T., Sekijima, Y., Kametani, F., and Okumura, N. (2018). Hereditary Fibrinogen Aα-Chain Amyloidosis in Asia: Clinical and Molecular Characteristics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19, 320.

- Jin, S. , Shen, Z., Li, J., Lin, P., Xu, X., Ding, X., and Liu, H. (2021). Fibrinogen A Alpha-Chain Amyloidosis Associated With a Novel Variant in a Chinese Family. Kidney Int Rep 6, 2726-2730. [CrossRef]

- Grixti, J.M. , Theron, C.W., Salcedo-Sora, J.E., Pretorius, E. and Kell, D.B. (2024). Automated microscopic measurement of fibrinaloid microclots and their degradation by nattokinase, the main natto protease. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Application of Chinese Medicine https://ojs.exploverpub.com/index.php/jecacm/article/view/201.

- Reitsma, S. , Slaaf, D.W., Vink, H., van Zandvoort, M.A., and oude Egbrink, M.G. (2007). The endothelial glycocalyx: composition, functions, and visualization. Pflugers Arch 454, 345-359. [CrossRef]

- Artl, A. , Marsche, G., Lestavel, S., Sattler, W., and Malle, E. (2000). Role of serum amyloid A during metabolism of acute-phase HDL by macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20, 763-772. [CrossRef]

- Kisilevsky, R. , and Manley, P.N. (2012). Acute-phase serum amyloid A: perspectives on its physiological and pathological roles. Amyloid 19, 5-14. [CrossRef]

- Shattil, S.J. , and Newman, P.J. (2004). Integrins: dynamic scaffolds for adhesion and signaling in platelets. Blood 104, 1606-1615. [CrossRef]

- Radomski, M.W. , Palmer, R.M., and Moncada, S. (1987). Endogenous nitric oxide inhibits human platelet adhesion to vascular endothelium. Lancet 2, 1057-1058. [CrossRef]

- Uhlar, C.M. , and Whitehead, A.S. (1999). Serum amyloid A, the major vertebrate acute-phase reactant. Eur J Biochem 265, 501-523. [CrossRef]

- Shattil, S.J. , Kim, C., and Ginsberg, M.H. (2010). The final steps of integrin activation: the end game. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11, 288-300. [CrossRef]

- Van Lenten, B.J. , Hama, S.Y., de Beer, F.C., Stafforini, D.M., McIntyre, T.M., Prescott, S.M., La Du, B.N., Fogelman, A.M., and Navab, M. (1995). Anti-inflammatory HDL becomes pro-inflammatory during the acute phase response. Loss of protective effect of HDL against LDL oxidation in aortic wall cell cocultures. J Clin Invest 96, 2758-2767. [CrossRef]

- de Beer, M.C., Yuan, T., Kindy, M.S., Asztalos, B.F., Roheim, P.S., and de Beer, F.C. (1995). Characterization of constitutive human serum amyloid A protein (SAA4) as an apolipoprotein. J Lipid Res 36. 526–534.

- Frame, N.M. , and Gursky, O. (2016). Structure of serum amyloid A suggests a mechanism for selective lipoprotein binding and functions: SAA as a hub in macromolecular interaction networks. FEBS Lett 590, 866-879. [CrossRef]

- Webb, N.R. (2021). High-Density Lipoproteins and Serum Amyloid A (SAA). Curr Atheroscler Rep 23, 7. [CrossRef]

- Gursky, O. (2020). Structural Basis for Vital Function and Malfunction of Serum Amyloid A: an Acute-Phase Protein that Wears Hydrophobicity on Its Sleeve. Curr Atheroscler Rep 22, 69. [CrossRef]

- Ashe, K.H. , and Aguzzi, A. (2013). Prions, prionoids and pathogenic proteins in Alzheimer disease. Prion 7, 55-59. [CrossRef]

- Frontzek, K. , Bardelli, M., Senatore, A., Henzi, A., Reimann, R.R., Bedir, S., Marino, M., Hussain, R., Jurt, S., Meisl, G., et al. (2022). A conformational switch controlling the toxicity of the prion protein. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 29, 831-840. [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.L. , and Looger, L.L. (2018). Extant fold-switching proteins are widespread. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, 5968-5973. [CrossRef]

- Retamal-Farfán, I. , González-Higueras, J., Galaz-Davison, P., Rivera, M., and Ramírez-Sarmiento, C.A. (2023). Exploring the structural acrobatics of fold-switching proteins using simplified structure-based models. Biophys Rev 15, 787-799. [CrossRef]

- Wechalekar, A.D. , Gillmore, J.D., and Hawkins, P.N. (2016). Systemic amyloidosis. Lancet 387, 2641-2654. [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, S.A.M. , and Falk, R.H. (2020). Amyloidosis as a Systemic Disease in Context. Can J Cardiol 36, 396-407. [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, J.M. (2022). The association of lipids with amyloid fibrils. Journal of Biological Chemistry 298, 102108. [CrossRef]

- Kurouski, D. (2023). Elucidating the Role of Lipids in the Aggregation of Amyloidogenic Proteins. Accounts of Chemical Research 56, 2898-2906. [CrossRef]

- Hellstrand, E. , Nowacka, A., Topgaard, D., Linse, S., and Sparr, E. (2013). Membrane lipid co-aggregation with α-synuclein fibrils. PLoS One 8, e77235. [CrossRef]

- Kell, D.B. (2009). Iron behaving badly: inappropriate iron chelation as a major contributor to the aetiology of vascular and other progressive inflammatory and degenerative diseases. BMC Medical Genomics 2, 2. [CrossRef]

- Kell, D.B. , and Pretorius, E. (2018). No effects without causes: the Iron Dysregulation and Dormant Microbes hypothesis for chronic, inflammatory diseases. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 93, 1518-1557. [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, A. , Guo, L., Sakamoto, A., Virmani, R., and Finn, A.V. (2019). New insights into the role of iron in inflammation and atherosclerosis. eBioMedicine 47, 598-606. [CrossRef]

- Sharkey-Toppen, T.P. , Tewari, A.K., and Raman, S.V. (2014). Iron and Atherosclerosis: Nailing Down a Novel Target with Magnetic Resonance. Journal of Cardiovascular Translational Research 7, 533-542. [CrossRef]

- Kopriva, D. , Kisheev, A., Meena, D., Pelle, S., Karnitsky, M., Lavoie, A., and Buttigieg, J. (2015). The Nature of Iron Deposits Differs between Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerotic Plaques. PLoS One 10, e0143138. [CrossRef]

- Kun, A. , González-Camacho, F., Hernández, S., Moreno-García, A., Calero, O., and Calero, M. (2018). Characterization of Amyloid-β Plaques and Autofluorescent Lipofuscin Aggregates in Alzheimer’s Disease Brain: A Confocal Microscopy Approach. Methods Mol Biol 1779, 497-512. [CrossRef]

- Lowman, R.L. , and Yampolsky, L.Y. (2023). Lipofuscin, amyloids, and lipid peroxidation as potential markers of aging in Daphnia. Biogerontology 24, 541-553. [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.-P. , Gugiu, B., Renganathan, K., Davies, M.W., Gu, X., Crabb, J.S., Kim, S.R., Różanowska, M.B., Bonilha, V.L., Rayborn, M.E., et al. (2008). Retinal Pigment Epithelium Lipofuscin Proteomics. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 7, 1397-1405. [CrossRef]

- Ottis, P. , Koppe, K., Onisko, B., Dynin, I., Arzberger, T., Kretzschmar, H., Requena, J.R., Silva, C.J., Huston, J.P., and Korth, C. (2012). Human and rat brain lipofuscin proteome. Proteomics 12, 2445-2454. [CrossRef]

- Babaniamansour, P. , Mohammadi, M., Babaniamansour, S., and Aliniagerdroudbari, E. (2020). The Relation between Atherosclerosis Plaque Composition and Plaque Rupture. Journal of Medical Signals & Sensors 10, 267-273. [CrossRef]

- He, Z. , Luo, J., Lv, M., Li, Q., Ke, W., Niu, X., and Zhang, Z. (2023). Characteristics and evaluation of atherosclerotic plaques: an overview of state-of-the-art techniques. Front Neurol 14, 1159288. [CrossRef]

- Tomey, M.I. , Narula, J., and Kovacic, J.C. (2014). Advances in the Understanding of Plaque Composition and Treatment Options: Year in Review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 63, 1604-1616. [CrossRef]

- Howlett, G.J. , and Moore, K.J. (2006). Untangling the role of amyloid in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol 17, 541-547. [CrossRef]

- Dichtl, W. , Moraga, F., Ares, M.P., Crisby, M., Nilsson, J., Lindgren, S., and Janciauskiene, S. (2000). The carboxyl-terminal fragment of alpha1-antitrypsin is present in atherosclerotic plaques and regulates inflammatory transcription factors in primary human monocytes. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun 4, 50-61. [CrossRef]

- von zur Muhlen, C. , Schiffer, E., Sackmann, C., Zurbig, P., Neudorfer, I., Zirlik, A., Htun, N., Iphofer, A., Jansch, L., Mischak, H., et al. (2012). Urine proteome analysis reflects atherosclerotic disease in an ApoE-/- mouse model and allows the discovery of new candidate biomarkers in mouse and human atherosclerosis. Mol Cell Proteomics 11, M111 013847. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z. , Wu, T., Qin, W., An, C., Wang, Z., Zhang, M., Zhang, Y., Zhang, C., and An, F. (2011). Serum amyloid A directly accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Mol Med 17, 1357-1364. [CrossRef]

- Getz, G.S. , Krishack, P.A., and Reardon, C.A. (2016). Serum amyloid A and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol 27, 531-535. [CrossRef]

- Shridas, P. , and Tannock, L.R. (2019). Role of serum amyloid A in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol 30, 320-325. [CrossRef]

- Westermark, P. , Mucchiano, G., Marthin, T., Johnson, K.H., and Sletten, K. (1995). Apolipoprotein A1-derived amyloid in human aortic atherosclerotic plaques. Am J Pathol 147, 1186-1192.

- Mucchiano, G.I. , Jonasson, L., Haggqvist, B., Einarsson, E., and Westermark, P. (2001). Apolipoprotein A-I-derived amyloid in atherosclerosis. Its association with plasma levels of apolipoprotein A-I and cholesterol. Am J Clin Pathol 115, 298-303. [CrossRef]

- Obici, L. , Franceschini, G., Calabresi, L., Giorgetti, S., Stoppini, M., Merlini, G., and Bellotti, V. (2006). Structure, function and amyloidogenic propensity of apolipoprotein A-I. Amyloid 13, 191-205. [CrossRef]

- Williams, B. (2015). Amyloid beta and cardiovascular disease: intriguing questions indeed. J Am Coll Cardiol 65, 917-919. [CrossRef]

- Gagno, G. , Ferro, F., Fluca, A.L., Janjusevic, M., Rossi, M., Sinagra, G., Beltrami, A.P., Moretti, R., and Aleksova, A. (2020). From Brain to Heart: Possible Role of Amyloid-beta in Ischemic Heart Disease and Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Int J Mol Sci 21, 9655. [CrossRef]

- Kell, D.B. , Salcedo-Sora, J.E., and Pretorius, E. (2025). Amyloidogenic potential of plaque and thrombus proteomes and of fold-switching metamorphic proteins. Preprints, 2025081049. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, L. , Honsho, M., Zahn, T.R., Keller, P., Geiger, K.D., Verkade, P., and Simons, K. (2006). Alzheimer’s disease β-amyloid peptides are released in association with exosomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, 11172-11177. [CrossRef]

- Grixti, J.M. , Chandran, A., Pretorius, J.H., Walker, M., Sekhar, A., Pretorius, E., and Kell, D.B. (2025). Amyloid Presence in Acute Ischemic Stroke Thrombi: Observational Evidence for Fibrinolytic Resistance. Stroke. [CrossRef]

- Grixti, J.M. , Chandran, A., Pretorius, J.-H., Walker, M., Sekhar, A., Pretorius, E., and Kell, D.B. (2024). The clots removed from ischaemic stroke patients by mechanical thrombectomy are amyloid in nature. medRxiv, 2024.2011.2001.24316555. [CrossRef]

- Biancalana, M. , and Koide, S. (2010). Molecular mechanism of Thioflavin-T binding to amyloid fibrils. Biochim Biophys Acta 1804, 1405-1412. [CrossRef]

- Gade Malmos, K. , Blancas-Mejia, L.M., Weber, B., Buchner, J., Ramirez-Alvarado, M., Naiki, H., and Otzen, D. (2017). ThT 101: a primer on the use of thioflavin T to investigate amyloid formation. Amyloid 24, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Xue, C. , Lin, T.Y., Chang, D., and Guo, Z. (2017). Thioflavin T as an amyloid dye: fibril quantification, optimal concentration and effect on aggregation. R Soc Open Sci 4, 160696. [CrossRef]

- Das, S. , Purkayastha, P. (2017). Selective Binding of Thioflavin T in Sequence-Exchanged Single Strand DNA Oligomers and Further Interaction with Phospholipid Membranes. Chemistry Select 2, 5000.

- Hanczyc, P. , Rajchel-Mieldzioć, P., Feng, B., and Fita, P. (2021). Identification of Thioflavin T Binding Modes to DNA: A Structure-Specific Molecular Probe for Lasing Applications. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 12, 5436-5442. [CrossRef]

- Schlein, M. (2017). Insulin Formulation Characterization—the Thioflavin T Assays. The AAPS Journal 19, 397-408. [CrossRef]

- Harada, A. , Azakami, H., and Kato, A. (2008). Amyloid Fibril Formation of Hen Lysozyme Depends on the Instability of the C-Helix (88-99). Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 72, 1523-1530. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-H. , Tseng, C.-P., How, S.-C., Lo, C.-H., Chou, W.-L., and Wang, S.S.S. (2016). Amyloid fibrillogenesis of lysozyme is suppressed by a food additive brilliant blue FCF. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 142, 351-359. [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, E. , Mbotwe, S., Bester, J., Robinson, C.J., and Kell, D.B. (2016). Acute induction of anomalous and amyloidogenic blood clotting by molecular amplification of highly substoichiometric levels of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J R Soc Interface 13. [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, E. , Page, M.J., Hendricks, L., Nkosi, N.B., Benson, S.R., and Kell, D.B. (2018). Both lipopolysaccharide and lipoteichoic acids potently induce anomalous fibrin amyloid formation: assessment with novel Amytracker™ stains. J R Soc Interface 15. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.M. , Fillis, T., Page, M.J., Venter, C., Lancry, O., Kell, D.B., Windberger, U., and Pretorius, E. (2020). Gingipain R1 and Lipopolysaccharide From Porphyromonas gingivalis Have Major Effects on Blood Clot Morphology and Mechanics. Front Immunol 11, 1551. [CrossRef]

- Grobbelaar, L.M. , Venter, C., Vlok, M., Ngoepe, M., Laubscher, G.J., Lourens, P.J., Steenkamp, J., Kell, D.B., and Pretorius, E. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1 induces fibrin(ogen) resistant to fibrinolysis: implications for microclot formation in COVID-19. Biosci Rep 41. [CrossRef]

- Grobbelaar, L.M. , Kruger, A., Venter, C., Burger, E.M., Laubscher, G.J., Maponga, T.G., Kotze, M.J., Kwaan, H.C., Miller, J.B., Fulkerson, D., et al. (2022). Relative Hypercoagulopathy of the SARS-CoV-2 Beta and Delta Variants when Compared to the Less Severe Omicron Variants Is Related to TEG Parameters, the Extent of Fibrin Amyloid Microclots, and the Severity of Clinical Illness. Semin Thromb Hemost 48, 858-868. [CrossRef]

- Frame, N.M. , and Gursky, O. (2017). Structure of serum amyloid A suggests a mechanism for selective lipoprotein binding and functions: SAA as a hub in macromolecular interaction networks. Amyloid 24, 13-14. [CrossRef]

- Bilog, M. , Vedad, J., Capadona, C., Profit, A.A., and Desamero, R.Z.B. (2024). Key charged residues influence the amyloidogenic propensity of the helix-1 region of serum amyloid A. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 1868, 130690. [CrossRef]

- Zinellu, A. , Paliogiannis, P., Carru, C., and Mangoni, A.A. (2021). Serum amyloid A concentrations, COVID-19 severity and mortality: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 105, 668-674. [CrossRef]

- Bilog, M. , Cersosimo, J., Vigil, I., Desamero, R.Z.B., and Profit, A.A. (2024). Effect of a SARS-CoV-2 Protein Fragment on the Amyloidogenic Propensity of Human Islet Amyloid Polypeptide. ACS Chem Neurosci 15, 4431-4440. [CrossRef]

- Petrlova, J. , Samsudin, F., Bond, P.J., and Schmidtchen, A. (2022). SARS-CoV-2 spike protein aggregation is triggered by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. FEBS Lett 596, 2566-2575. [CrossRef]

- Petruk, G. , Puthia, M., Petrlova, J., Samsudin, F., Strömdahl, A.C., Cerps, S., Uller, L., Kjellström, S., Bond, P.J., and Schmidtchen, A.A. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binds to bacterial lipopolysaccharide and boosts proinflammatory activity. J Mol Cell Biol 12, 916-932. [CrossRef]

- Nyström, S. , and Hammarström, P. (2022). Amyloidogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. J Am Chem Soc 144, 8945-8950. [CrossRef]

- Thierry, A.R., Usher, T., Sanchez, C., Turner, S., Venter, C., Ha, T., Pastor, B., Waters, M., Thompson, A., Mirandola, A., Pisareva, E., Prevostel, C., Laubscher, GJ., Kell, D.B., Pretorius, E. (2025). Circulating microclots are structurally associated with Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and their amounts are strongly elevated in long COVID patients. Journal of Medical Virology 97. e70613. [CrossRef]

- Pisareva, E. , Badiou, S., Mihalovičová, L., Mirandola, A., Pastor, B., Kudriavtsev, A., Berger, M., Roubille, C., Fesler, P., Klouche, K., et al. (2023). Persistence of neutrophil extracellular traps and anticardiolipin auto-antibodies in post-acute phase COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol 95, e28209. [CrossRef]

| Cell type | Main fibrinogen-binding receptors | Comments |

| Platelets | Integrin αIIbβ3 (GPIIb/IIIa) [74] FPR2 [64] |

The dominant fibrinogen receptor αIIbβ3 essential for platelet aggregation and thrombus formation. SAA also binds to this αIIbβ3 receptor [64]. Platelets also have FPR2 receptors. αIIbβ3 is preferentially and highly expressed on resting platelets with 60,000–80,000 copies per cell [75]. |

| Endothelial cells | Integrins αvβ3 and α5β1 [15,76] ICAM1 [77] FPR2 |

Mediate fibrinogen binding, endothelial adhesion, angiogenesis, and leukocyte interactions Fibrinogen receptors contribute to clot stability at vessel walls α5β1 on endothelial cells, atheroprone flow plus oxidized lipoproteins increases the high-affinity conformation of α5β1, making ECs more adhesive and proinflammatory [76] α5β1 binds fibrin and fibronectin [78] FPR2 binds SAA [64] |

| Leukocytes (esp. neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages) | Integrin αMβ2 [79] (Mac-1, CD11b/CD18) FPR2 |

Binds fibrinogen, supports leukocyte adhesion, migration, and immunothrombosis. FRP2 important in linking inflammation to coagulation [64] |

| Erythrocytes | Less well-defined but perhaps GPIIbIIIa [80] |

Red cells can bind fibrinogen under inflammatory/prothrombotic conditions, but possibly not via a dedicated high-affinity receptor like platelets Not finally confirmed but GPIIbIIIa can possibly serve as fibrinogen binding sites. The presence of the GPIIbIIIa inhibitors reduces the amount of adsorbed fibrinogen, leading to a decrease in the hydrodynamic stability of RBC aggregates. |

| Regulatory Layer | Mechanism | Effect on SAA / Fibrinogen / Receptors | Key References |

| Receptor conformation | Platelet integrin αIIbβ3 is kept in a low-affinity state until “inside-out” signaling (e.g., via thrombin, ADP) activates it | Prevents fibrinogen and SAA from binding under resting conditions | [175] |

| Endothelial anti-adhesive surface | Endothelial glycocalyx (heparan sulfates, proteoglycans) blocks receptor access; NO and PGI2 secretion suppress platelet activation | Prevents SAA and fibrinogen interaction with receptors on healthy endothelium and platelets | [172,176] |

| Plasma binding partners | SAA is mostly HDL-bound in health; fibrinogen requires thrombin cleavage to reveal αIIbβ3 binding sites | Circulating ligands are “shielded” from receptor engagement | [177] |

| Membrane lipid asymmetry | Phosphatidylserine (PS) is restricted to inner leaflet by flippases | Prevents formation of procoagulant binding sites for clotting factors and SAA | [17] |

| Protective mechanism (healthy circulation) | Change during inflammation/disease |

| Integrins (e.g., αIIbβ3) inactive → low-affinity state maintained until platelet inside-out signaling activates them [175,178] | Platelet activation by thrombin, ADP, thromboxane A2, or cytokines triggers conformational change of αIIbβ3 → high-affinity fibrinogen and SAA binding [178] |

| Endothelial glycocalyx + NO/PGI2 enforce anti-adhesion, maintain vascular quiescence [172] | Glycocalyx degraded by ROS, proteases, and inflammatory enzymes; reduced NO/PGI2 signaling → adhesion molecules and receptors exposed (Lipowsky, 2012; Schmidt et al., 2020) |

| SAA sequestered in HDL complexes under baseline conditions, minimal free circulating SAA [179] | Acute-phase response: SAA upregulated 1000-fold and dissociates from HDL [180] Large pool of free can then potentially SAA binds receptors and fibrinogen. |

| PS restricted to inner leaflet by flippases maintains lipid asymmetry, no catalytic surface for coagulation [17,22] | In apoptosis/activation: scramblase activation + flippase inhibition; PS externalization, generating negatively charged catalytic surfaces for factor binding [17] |

| Protective partner (health) | Mechanism of “safety” | Status in health (SAA levels <5 mg/L) | What changes in inflammation (SAA up to 1000 mg/L) | References |

| HDL (apoA-I containing particles) | Major carrier, prevents SAA functioning as an inflammatory molecule | SAA tightly bound to HDL; free SAA negligible | HDL composition altered; apoA displaced by SAA (“acute-phase HDL”) with reduced protective function; free SAA increases | [181,182] |

| Apolipoproteins | ApoA stabilize HDL, reducing SAA exposure | ApoA is abundant; maintain HDL’s anti-amyloid function | ApoA levels fall; displaced by SAA, exposure of hydrophobic domains; ApoE overwhelmed. | [177] |

| Lipid components (phospholipids, cholesterol esters) | SAA intercalates into HDL phospholipid monolayer, hydrophobic residues shielded | Normal lipid ratios keep SAA soluble within HDL | Acute-phase HDL lipid ratios altered; SAA less shielded and more aggregation-prone | [181,183] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).