1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease encompasses a broad spectrum of conditions, including atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, hypertension, and stroke [

1]. A key contributor to cardiovascular disease pathophysiology is platelet hyperactivation, which facilitates atherosclerotic plaque development, plaque rupture, and thrombus formation [

2]. Under physiological conditions, platelets play a critical role in maintaining hemostasis [

3]; however, when excessively activated, they can form occlusive thrombi that impair blood flow, potentially resulting in myocardial infarction, stroke, or other ischemic complications [

4]. Accordingly, pharmacological inhibition of platelet function remains a well-established approach for both the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular disease [

5,

6,

7,

8]. While synthetic antiplatelet agents have been instrumental in managing cardiovascular diseases, their use is often accompanied by significant adverse effects. For instance, clopidogrel has been associated with rare but severe hematological disorders such as aplastic anemia and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura . Similarly, long-term aspirin therapy is linked to gastrointestinal complications, including ulcer formation and an increased risk of bleeding [

9]. Considering this, the ethnomedical approach could be a promising strategy for preventing cardiovascular disease and its complications [

6].

Platelets contain dense (δ) and alpha (α) granules. δ granules store adenosine diphosphate (ADP), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), Ca

2+, and serotonin, whereas α granules contain fibronectin, fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor (vWF), and P-selectin [

6,

10]. Multiple signaling pathways control granule secretion, including Src family kinases (early platelet activation), intracellular Ca

2+ mobilization, the cAMP-VASP-PKA pathway, protein kinase C (PKC) activation, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) cascades, and RhoA-regulated cytoskeletal reorganization [

10]. The increase in intracellular Ca

2+ is essential for platelet function, initiating downstream signaling that promotes aggregation and thrombus formation [

11]. Platelet activation also depends on integrin αIIbβ

3, which undergoes conformational changes during inside-out signaling and binds fibrinogen, a critical step in the formation of stable thrombi [

12]. Fibronectin enhances aggregation by interacting with integrins and recruiting signaling molecules to the cytoplasmic tails [

13]. Additionally, Rho GTPases and Rho kinases (ROCKs) regulate cytoskeletal remodeling through myosin light chain phosphorylation, influencing platelet morphology, motility, and clot retraction [

14]. Notably, treatment with natural products has been shown to reduce Ca

2+ mobilization, ATP and serotonin release, fibrinogen binding, fibronectin adhesion, and clot retraction, indicating that such compounds exert antiplatelet effects through the inhibition of granule secretion and integrin αIIbβ

3 signaling [

12,

15]. Despite the effectiveness of current antiplatelet agents such as aspirin and clopidogrel, these drugs are frequently associated with adverse effects and complications [

16,

17]. Aspirin, for instance, may cause severe gastric ulcers and prolonged bleeding, whereas clopidogrel has been linked to aplastic anemia and thrombocytopenic purpura [

6]. Moreover, a substantial proportion of patients exhibit resistance to these therapies [

18,

19]. Factors contributing to aspirin resistance include genetic polymorphisms in cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and other thromboxane-related genes, upregulated thromboxane biosynthesis from non-platelet sources, elevated platelet turnover, and interindividual variability in drug absorption [

5]. These limitations highlight the pressing need for safer and more efficacious antiplatelet agents.

Natural products have historically been a rich source of bioactive molecules [

20,

21,

22]. Numerous plant-derived and microbial metabolites demonstrate potent antiplatelet activity by targeting key enzymes or receptors involved in platelet aggregation [

20,

23,

24,

25]. These multitarget mechanisms reflect the broader therapeutic potential of natural compounds, which often exert bidirectional regulatory effects on physiological processes and tend to produce fewer side effects. Several marine fungi have previously been reported to possess bioactive natural products and significantly beneficial antiplatelet activities; for example,

Epicoccum sorghinum metabolites inhibit platelet aggregation and inflammation [

26], and

Aspergillus species have been reported to exhibit antiplatelet as well as anticancer properties [

27]. Moreover, marine fungal lipid bioactives display anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic effects, underscoring their promise as sources of novel antiplatelet agents [

28].

Among microbial sources,

Aspergillus species are well known for producing a wide variety of secondary metabolites with therapeutic potential, including antiviral xanthones, diphenyl ether and butenolide derivatives with α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, and benzophenones with antimicrobial properties [

29]. Chlorinated diphenyl ethers, in particular, serve as chemical markers of

Aspergillus spp. and are generally believed to originate from anthraquinone precursors such as emodin, via intermediates such as sulochrin and grisandienes (e.g., geodin) [

29]. The genus

Fennellia (family Trichocomaceae), which includes

F. flavipes and

F. nivea, has been identified as the teleomorph of

Aspergillus flavipes [

30]. Although

A. flavipes has been extensively studied for its production of cytochalasins, alkaloids, polyketides, butenolides, meroterpenoids, diphenyl ethers, benzophenones, and xanthones [

31], some of which exhibit cytotoxic, antibacterial, or glucosidase-inhibiting properties, relatively little is known about the bioactive compounds specifically produced by

F. flavipes [

31]. This study began to address this gap by identifying several notable metabolites from

F. flavipes, including a newly characterized dimeric 1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran and five previously known compounds, such as dihydrogeodin (DHG) [

31,

32]. In the present study, we isolated DHG from the culture broth of

F. flavipes and evaluated its

in vitro antiplatelet activity. Our findings demonstrate that DHG functions as a potent inhibitor of platelet aggregation, highlighting the potential of

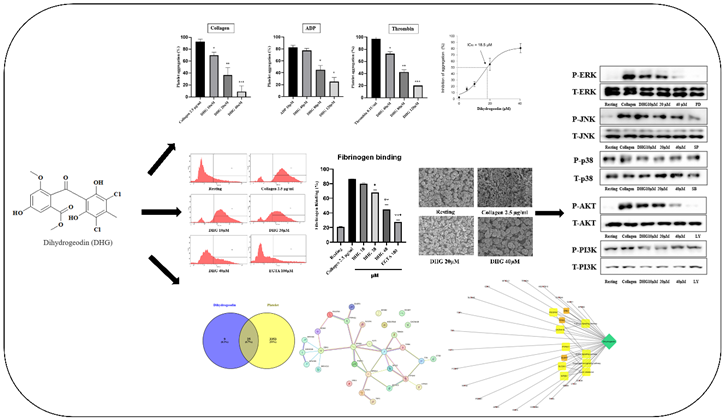

F. flavipes as a source of novel antiplatelet agents and pharmacologically active natural products (Graphical abstract).

3. Discussion

Natural products have attracted considerable interest due to their multitarget activities and relatively low incidence of adverse effects [

39]. Recent studies have identified marine-derived compounds as promising sources of antiplatelet agents [

40,

41,

42,

43]. Similarly, various herbal medicines and their purified constituents have demonstrated potent antiplatelet activity [

6,

44,

45]. For example, in our recently published study, ginsenoside Rg5 regulates GPVI signaling pathways by inhibiting collagen-induced platelet aggregation. The cryptotanshinone from

Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge exerts P2Y

12-independent antiplatelet effects by downregulating the PI3K/Akt, MAPK, and STAT3 pathways [

46]. Tryptanthrin from

Isatidis Radix interferes with both inside-out and outside-in αIIbβ

3 signaling, thus preventing stable thrombus formation [

45]. Additionally, dieckol from

Eisenia bicyclis inhibits platelet aggregation by suppressing granule secretion, integrin αIIbβ

3 function, and the RhoA/ROCK pathway [

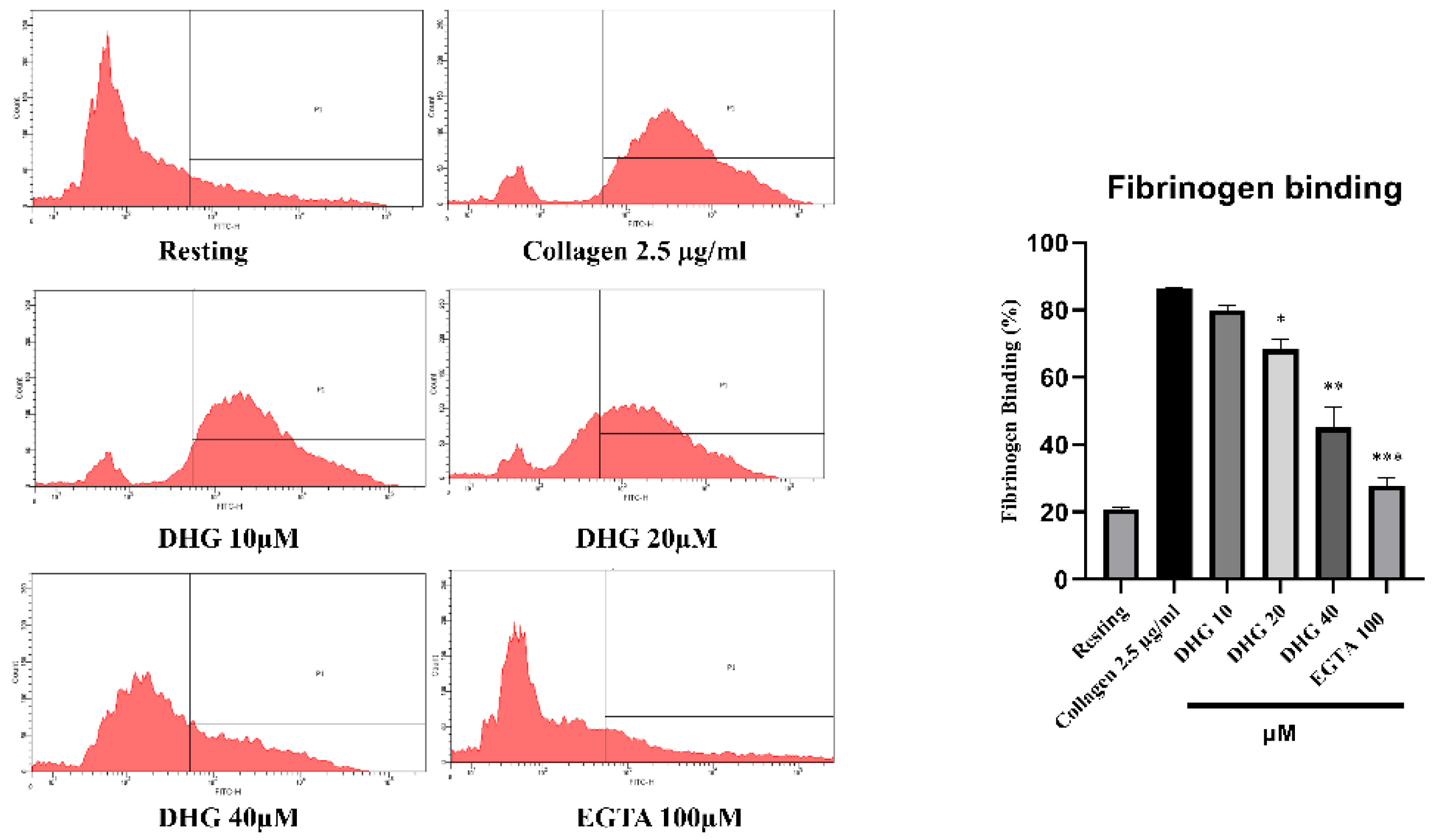

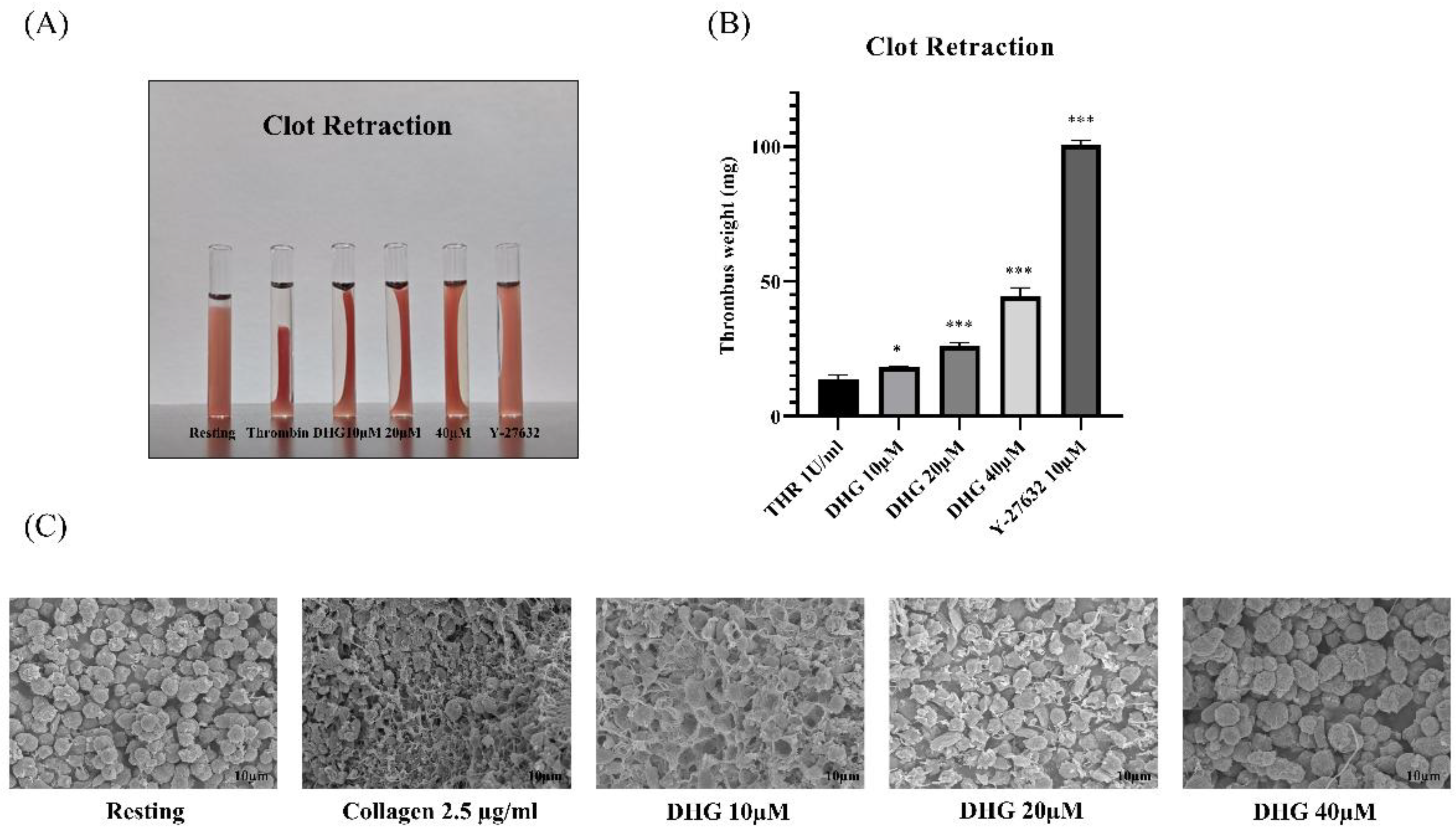

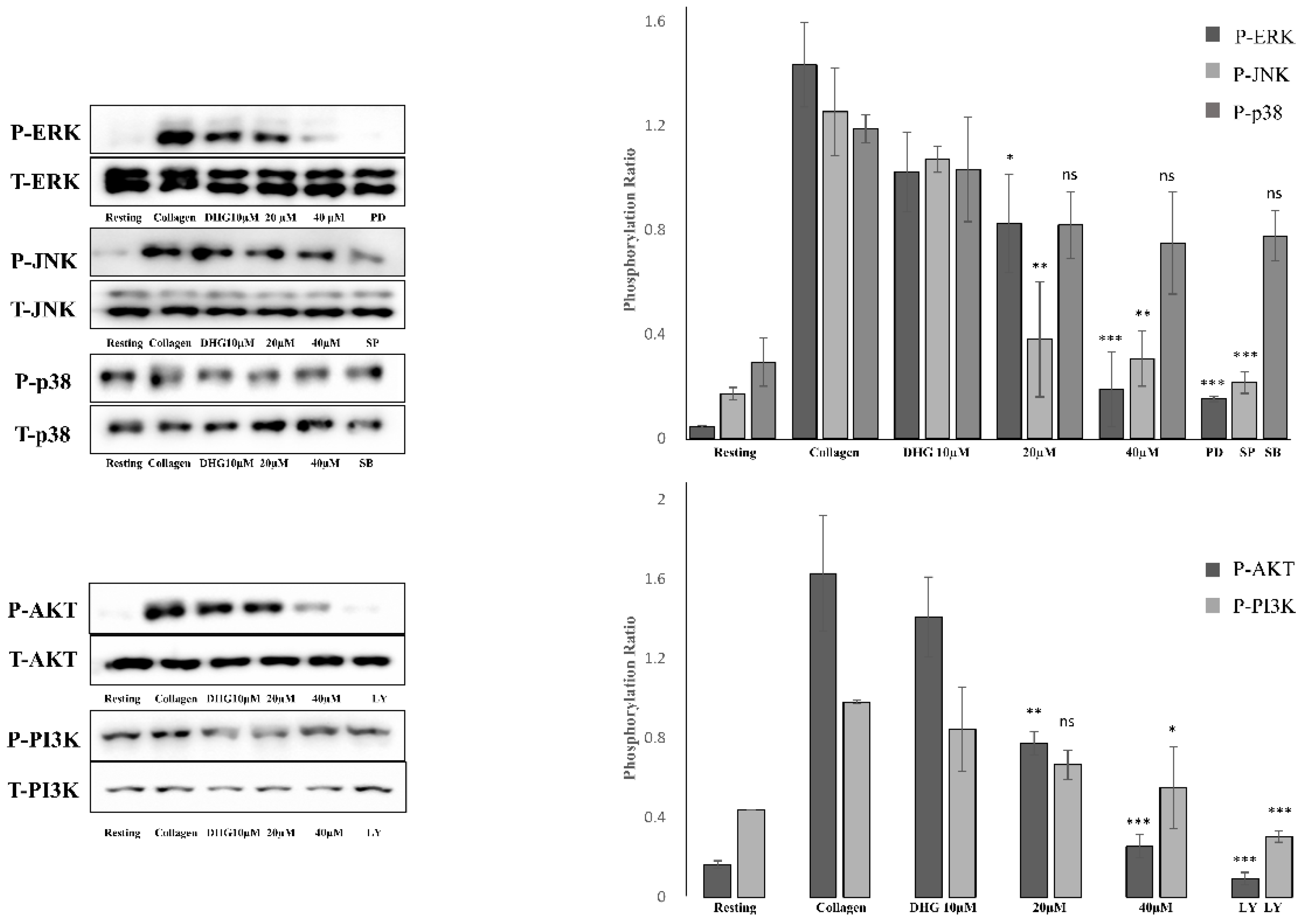

12]. Similarly, in our study, DHG attenuated integrin αIIbβ

3–mediated fibrinogen binding and clot retraction, as well as the phosphorylation of MAPK (ERK, JNK, p38) and PI3K/Akt, underscoring its multifaceted mode of action.

Platelet activation depends on a coordinated network of signaling events triggered by vascular injury [

47]. Collagen, ADP, and thrombin activate distinct platelet receptors, GPVI, P2Y

12, and protease-activated receptors, respectively, to initiate granule secretion, integrin αIIbβ

3 activation, and cytoskeletal reorganization [

48]. DHG significantly inhibited platelet aggregation induced by collagen, ADP, and thrombin in a dose-dependent manner, indicating broad inhibitory activity across multiple platelet activation pathways (

Figure 1). In addition to its inhibition of aggregation, DHG substantially reduced intracellular Ca

2+ mobilization and ATP release in response to collagen stimulation (

Figure 2). Given the critical role of Ca

2+ in platelet granule secretion, these results suggest that DHG disrupts upstream signaling events essential for platelet activation and may prevent thrombus formation at an early stage. DHG significantly reduced fibrinogen binding to platelets, indicating strong inhibition of αIIbβ

3 activation. By blocking this step, DHG prevents the formation of stable platelet plugs (

Figure 3). Furthermore, DHG attenuated human thrombin-induced clot retraction, mirroring the effects of established ROCK inhibitors and also prevented collagen-induced platelet shape change (

Figure 4). DHG also reduced the phosphorylation of key signaling proteins in a dose-dependent manner without significantly altering total protein levels (

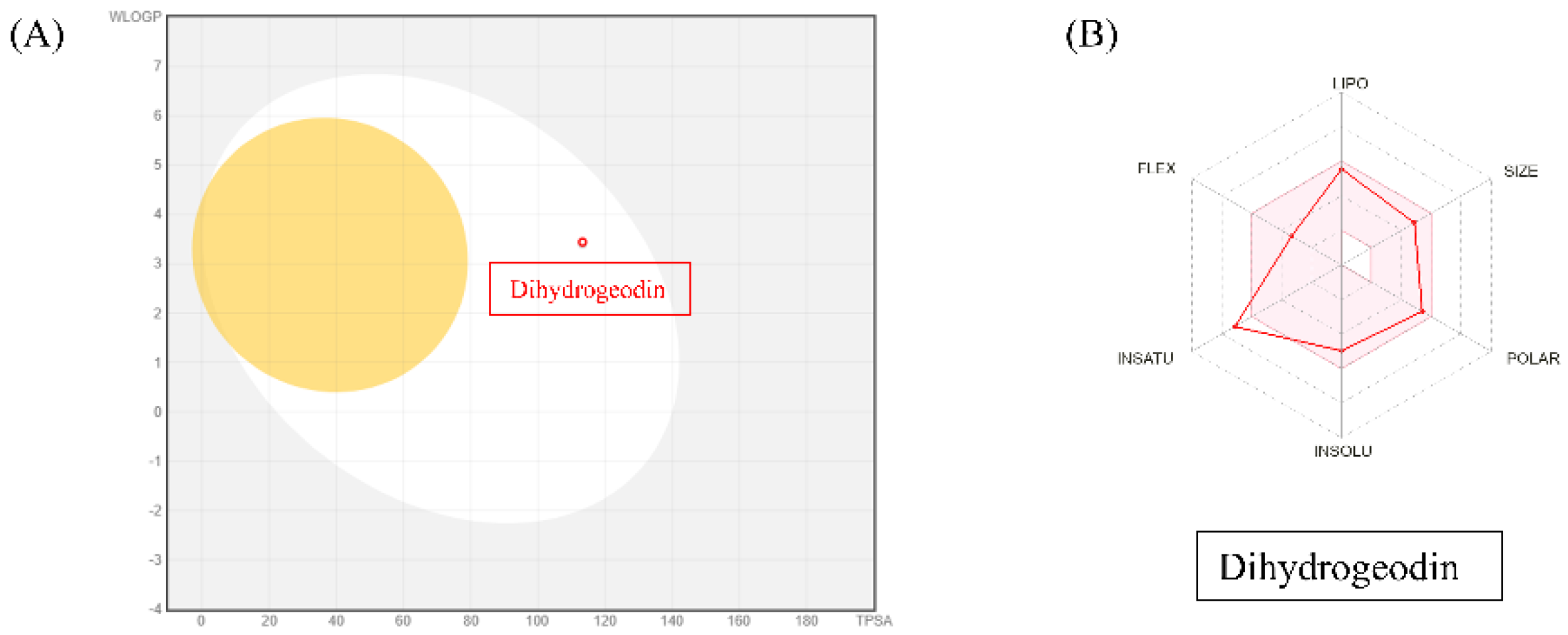

Figure 5). Additionally, DHG satisfies Lipinski’s rule of five, suggesting good oral bioavailability. It also demonstrated favorable lipophilicity, solubility, and gastrointestinal absorption, along with a low probability of blood-brain barrier permeability (

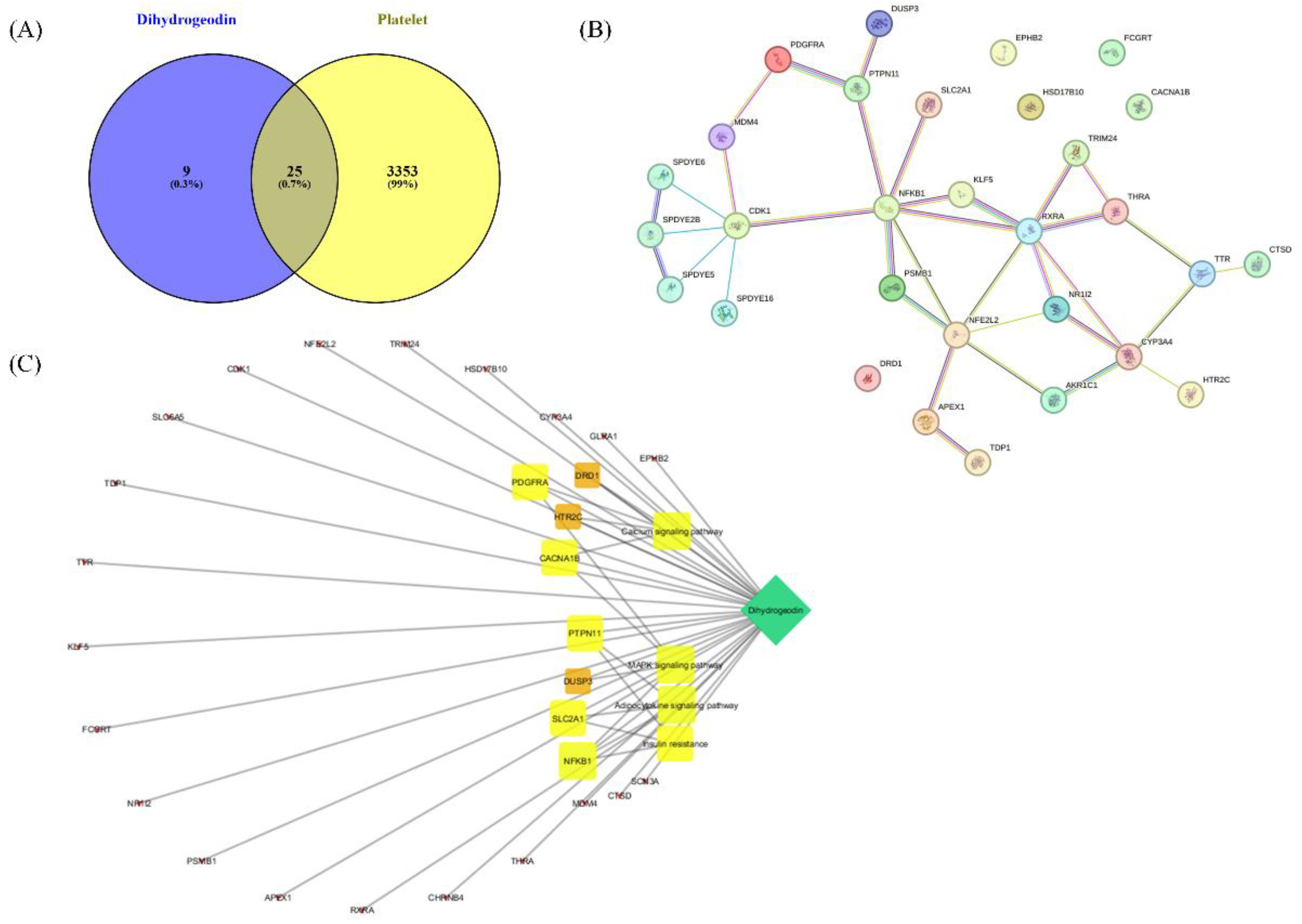

Figure 6A and B). Venn diagram showing the intersection between DHG-predicted targets and genes associated with platelet activation (

Figure 7A). Among the 34 DHG-related genes and 3,353 platelet activation-related genes, 25 common genes were identified, representing potential targets through which DHG may influence platelet function.

Figure 7B presents a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network constructed from the 25 overlapping genes using the STRING database. The network reveals a tightly connected hub centered around key nodes such as NFKB1, CDK1, RXRA, PDGFRA, and PTPN11, indicating their crucial roles in mediating the interaction between DHG and platelet-related signaling. These core targets are functionally linked through multiple biological processes, suggesting DHG may exert multi-targeted modulation. Further,

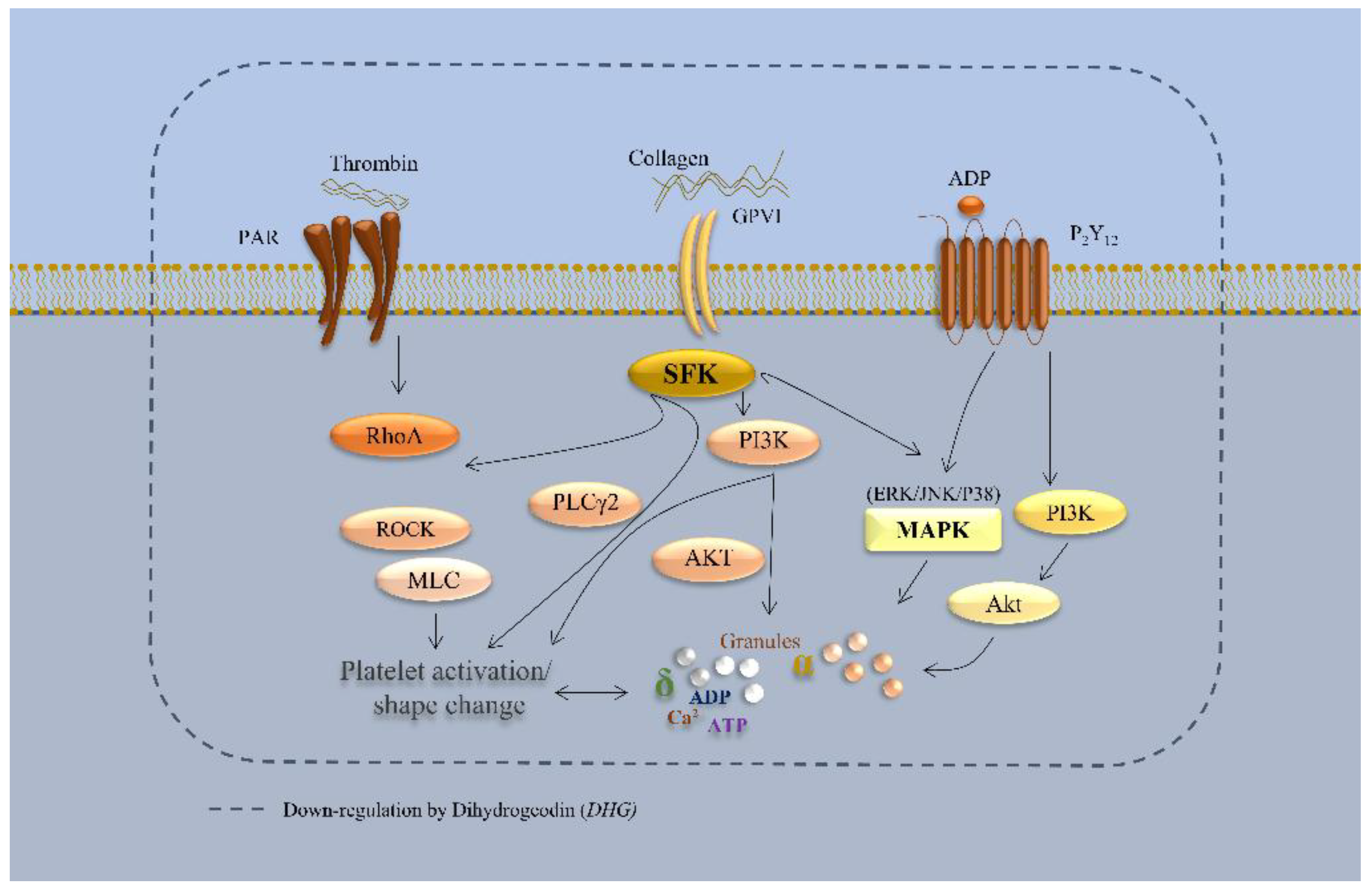

Figure 7C shows the compound–target–pathway network constructed using Cytoscape. DHG is connected to several targets, including NFKB1, PDGFRA, DRD1, PTPN11, and HTR2C, which are further linked to relevant pathways such as the MAPK signaling pathway, calcium signaling pathway, adipocytokine signaling pathway, and insulin resistance. These enriched pathways have established roles in platelet function, inflammation, and cardiovascular regulation, supporting the potential of DHG to modulate platelet activity through multiple signaling cascades. Taken together, these pharmacological properties support DHG as a promising candidate for antithrombotic drug development.

Unlike many conventional antiplatelet agents, which typically target a single receptor or enzyme (e.g., P2Y

12 for clopidogrel or COX-1 for aspirin), DHG appears to modulate multiple pathways integral to platelet function. Our results demonstrate that DHG inhibits platelet aggregation while reducing ATP release, intracellular Ca

2+ mobilization, αIIbβ

3 integrin activation, clot retraction, and activation of the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways (see schematic in

Figure 8). Collectively, these findings suggest a broad-spectrum antiplatelet mechanism, similar to that of other recently reported multitarget natural compounds such as ginsenoside Rg5 [

15] cryptotanshinone [

46], dieckol [

12], and tryptanthrin [

45], which also inhibit platelet activation by modulating multiple signaling cascades. However,

in vivo studies are necessary to further elucidate the pharmacological effects of DHG in animal models or human platelets. Although the

in vitro findings strongly support its antiplatelet efficacy, translation of these results to

in vivo systems requires additional investigation. Therefore, future studies using animal models of arterial thrombosis (e.g., FeCl

3-induced vascular injury) or venous thrombosis are essential to establish its therapeutic potential.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

Collagen, ADP, and thrombin were obtained from Chrono-Log Co. (Netherlands). Human plasma-derived thrombin and glutaraldehyde were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. ATP assay kits were acquired from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Paraformaldehyde, Fura 2-AM, and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated fibrinogen were obtained from Invitrogen (Eugene, OR, USA). Avertin was prepared as the anesthetic by dissolving 2,2,2-tribromoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. T48402-5G) in 2-methyl-2-butanol (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. 152463). All antibodies for western blotting were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (USA).

4.2. Fungal Material and Fermentation

A fungal strain of F. flavipes (FU00000759) was obtained from the National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK). This strain was isolated from a tidal flat in Incheon, located on the Western Coast of Korea. The strain was cultured in twenty 5-L flasks, each containing 1 L of potato dextrose broth, at 27°C for 4 weeks under stationary conditions.

4.3. Extraction, Isolation, and Structure Determination

The extraction, isolation, and structure determination of the active compounds from

F. flavipes were performed as described in our recent publication [

31] and supplementary material section 1.1. The

1H and

13C NMR spectra matched those known for dihydrogeodin [

31,

32], and complete data is provided in supplementary material Fig. S1-S5.

4.4. Experimental Animals

Seven-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 240–260 g were used for in vitro platelet experiments. The animals were acclimated in an environmentally controlled room maintained at approximately 23 ± 2°C and 50% ± 10% humidity, with a 12-h light/dark cycle. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines and approved by the Animal Care Committee of the College of Veterinary Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, South Korea (Permit no KNU 2022-0083).

4.5. Light Transmission Aggregometry and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Blood was collected from Sprague-Dawley rats via cardiac puncture using a syringe containing acid-citrate-dextrose to isolate purified platelets [

6]. The collected blood was transferred into round-bottom tubes containing Tyrode’s buffer and acid-citrate-dextrose at a 1:4 (v/v) ratio. Washed platelets were separated from whole blood by centrifugation at 170 × g for 7 min, followed by a second centrifugation at 350 × g for 10 min. The platelet suspension was adjusted to a concentration of 3 × 10

8 cells/mL for aggregometry analysis. Platelets were incubated for 1 min with DHG (10, 20, or 40 μM) or with DMSO as a control in the presence of 1 mM CaCl

2. Aggregation was then induced by the addition of agonists (collagen at 2.5 μg/mL, ADP at 10 μM, or thrombin at 0.1 U/mL) for 5 min. This method enabled precise quantification of the platelet response under defined experimental conditions, providing valuable insights into the effects of dihydrogeodin on platelet function. Platelets incubated with DHG and agonist (collagen) were fixed in 0.5% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated, and freeze-dried at –55 °C before being mounted for field-emission scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi SU8220) to assess ultrastructural shape changes.

4.6. ATP Release Assay, [Ca2+]i Mobilization Assay, and Fibrinogen Binding Assay

Platelets were preincubated with dihydrogeodin and then stimulated with collagen to induce activation. Subsequently, ATP release, intracellular calcium mobilization, and fibrinogen binding were assessed as previously described [

6]. ATP secretion was measured in the supernatant using an ATP assay kit to evaluate platelet function. Intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca

2+]

i) was determined in Fura-2/AM-loaded platelets using the following formula: 224 nM × (F – F

min) / (F

max – F). For the fibrinogen binding assay, platelets were stained with an anti-fibrinogen antibody, and activation levels were evaluated by flow cytometry after collagen stimulation in the presence or absence of dihydrogeodin.

4.7. Clot Retraction

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP, 250 μL) was incubated for 2 min with DHG or Y-27632 (a ROCK inhibitor). A final volume of 1 mL was achieved by adding red blood cells (5 μL) and Tyrode’s buffer. Thrombin (1 U/mL) was then added, and clot retraction was assessed at room temperature. Thrombin-induced clots were weighed to compare clot retraction among treatment groups.

4.8. Western Blotting

After preincubation with DHG and stimulation with collagen, lysis buffer was added to initiate lysis, and protein concentrations were quantified. Whole platelet proteins were isolated for subsequent analysis. Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes were blocked and incubated overnight with primary antibodies, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies for 3 h. The membranes were then washed three times and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence. This procedure enabled evaluation of changes in protein expression induced by dihydrogeodin treatment.

4.9. Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeliness Analysis, and Network Pharmacology

SwissADME, a freely accessible web-based tool, was used to evaluate the pharmacokinetic properties and drug-likeness of DHG, as previously reported [

49]. Briefly, the canonical SMILES notation for DHG was retrieved from PubChem (PC-ID 612831

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Dihydrogeodin) and entered into the SwissADME platform (

http://www.swissadme.ch/). The resulting output files and images were directly imported from the website. The BOILED-Egg (Brain Or Intestinal Estimated permeation predictive) model provides a rapid and straightforward method for assessing human intestinal absorption (HIA) and blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeation by calculating the lipophilicity and polarity of molecules, followed by generation of a water partition coefficient (WLOGP) versus topological polar surface area (tPSA) plot. For network pharmacology, the potential target proteins of DHG were predicted using the SuperPred webserver, and the results were downloaded as CSV files. Corresponding UniProt IDs for Homo sapiens were retrieved and used for protein mapping via the STRING database to identify protein names (preferred names) associated with DHG. To identify disease-related targets, the keyword “platelet activation” was searched in the GeneCards database, and relevant human gene targets were extracted. The predicted DHG target genes (compound-related genes) and platelet activation-related genes (disease target genes) were compared using Venny 2.1. This analysis identified overlapping targets (common genes) between DHG and platelet activation. These overlapping targets were input into the STRING database (organism: Homo sapiens) to generate a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network and assess potential biological connections. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was also performed through STRING to identify key signaling pathways associated with the overlapping genes. Finally, the network of DHG, overlapping target genes, and enriched pathways was constructed and visualized using Cytoscape software (version 3.7.2).

4.10. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc Dunnett’s test (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) to determine statistical significance. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). A P-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Abdul Wahab Akram, Dae-Cheol Choi, Bong-Sik Yun, Man Hee Rhee; methodology, Abdul Wahab Akram, Dae-Cheol Choi, Bong-Sik Yun, Man Hee Rhee; software, Abdul Wahab Akram, Bong-Sik Yun, Man Hee Rhee; validation, Bong-Sik Yun, Man Hee Rhee; formal analysis, Abdul Wahab Akram; investigation, Man Hee Rhee; resources, Dae-Cheol Choi, Bong-Sik Yun, Man Hee Rhee; data curation, Abdul Wahab Akram, Dae-Cheol Choi; writing—original draft preparation, Abdul Wahab Akram, Dae-Cheol Choi, Hyung-Kyu Chae , Sung Dae Kim, Dongmi Kwak; writing—review and editing, Abdul Wahab Akram, Dae-Cheol Choi, Hyung-Kyu Chae , Sung Dae Kim, Dongmi Kwak, Bong-Sik Yun, Man Hee Rhee; visualization, Bong-Sik Yun, Man Hee Rhee; supervision, Bong-Sik Yun, Man Hee Rhee; project administration, Bong-Sik Yun, Man Hee Rhee; funding acquisition, Bong-Sik Yun, Man Hee Rhee. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Dihydrogeodin (DHG) inhibits agonist-induced platelet aggregation. Washed platelets were incubated for 1 min with DHG in the presence of 1 mM CaCl2. Aggregation was initiated by the addition of agonists. (A) Chemical structure of DHG. (B) Effect of DHG on collagen-induced platelet aggregation. (C) Effect of DHG on ADP-induced platelet aggregation. (D) Effect of DHG on thrombin-induced platelet aggregation. (E) IC₅₀ of DHG for collagen-induced platelet aggregation. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Dunnett's test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus agonist.

Figure 1.

Dihydrogeodin (DHG) inhibits agonist-induced platelet aggregation. Washed platelets were incubated for 1 min with DHG in the presence of 1 mM CaCl2. Aggregation was initiated by the addition of agonists. (A) Chemical structure of DHG. (B) Effect of DHG on collagen-induced platelet aggregation. (C) Effect of DHG on ADP-induced platelet aggregation. (D) Effect of DHG on thrombin-induced platelet aggregation. (E) IC₅₀ of DHG for collagen-induced platelet aggregation. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Dunnett's test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus agonist.

Figure 2.

DHG inhibits platelet granule release. (A) Platelets were preincubated with DHG, stimulated with collagen, and the supernatant was analyzed for ATP using a standard ATP assay kit. (B) Intracellular Ca2+ levels were assessed using Fura-2/AM-loaded platelets. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus collagen alone.

Figure 2.

DHG inhibits platelet granule release. (A) Platelets were preincubated with DHG, stimulated with collagen, and the supernatant was analyzed for ATP using a standard ATP assay kit. (B) Intracellular Ca2+ levels were assessed using Fura-2/AM-loaded platelets. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus collagen alone.

Figure 3.

DHG inhibits integrin αIIbβ3–mediated inside-out signaling pathway. (Left) Flow cytometry histograms showing fibrinogen binding in resting and collagen-stimulated platelets (2.5 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of DHG (10, 20, 40 μM) or EGTA (100 μM). (Right) Quantification of fibrinogen binding. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus collagen alone.

Figure 3.

DHG inhibits integrin αIIbβ3–mediated inside-out signaling pathway. (Left) Flow cytometry histograms showing fibrinogen binding in resting and collagen-stimulated platelets (2.5 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of DHG (10, 20, 40 μM) or EGTA (100 μM). (Right) Quantification of fibrinogen binding. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus collagen alone.

Figure 4.

DHG inhibits clot retraction. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was incubated for 2 min with DHG or Y-27632. Human thrombin (1 U/mL) was then added, and (A) clot retraction and clot shape change were assessed at room temperature for 90 min. (B) The clot weight was assessed *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus thrombin alone. (C) Platelet shape change was visualized with scanning electron microscopy (SEM). SEM images of the platelet shape revealed a change in morphology from discoid to a rounded shape containing filopodia upon activation with collagen, which was prevented by treatment with DHG.

Figure 4.

DHG inhibits clot retraction. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was incubated for 2 min with DHG or Y-27632. Human thrombin (1 U/mL) was then added, and (A) clot retraction and clot shape change were assessed at room temperature for 90 min. (B) The clot weight was assessed *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus thrombin alone. (C) Platelet shape change was visualized with scanning electron microscopy (SEM). SEM images of the platelet shape revealed a change in morphology from discoid to a rounded shape containing filopodia upon activation with collagen, which was prevented by treatment with DHG.

Figure 5.

DHG inhibits protein phosphorylation. Platelets were preincubated with DHG and stimulated with collagen. Aggregation was halted by the addition of lysis buffer, after which protein concentrations were measured. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with specific antibodies after membrane blocking. Visualization was performed using enhanced chemiluminescence. Representative Western blots (left panels) and corresponding quantification (right panels) show the phosphorylation levels of MAPK (ERK, JNK, p38) and PI3K/Akt in platelets pretreated with DHG (10, 20, 40 μM) or a reference inhibitor. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Dunnett's test *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus collagen alone.

Figure 5.

DHG inhibits protein phosphorylation. Platelets were preincubated with DHG and stimulated with collagen. Aggregation was halted by the addition of lysis buffer, after which protein concentrations were measured. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with specific antibodies after membrane blocking. Visualization was performed using enhanced chemiluminescence. Representative Western blots (left panels) and corresponding quantification (right panels) show the phosphorylation levels of MAPK (ERK, JNK, p38) and PI3K/Akt in platelets pretreated with DHG (10, 20, 40 μM) or a reference inhibitor. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Dunnett's test *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus collagen alone.

Figure 6.

SwissADME analysis of DHG. The canonical SMILES for DHG were retrieved from PubChem and entered into SwissADME. Output files and visualizations were directly from the website. (A) The BOILED-Egg model evaluated human intestinal absorption (HIA) and blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability based on lipophilicity and polarity, generating a WLOGP versus tPSA plot. (B) SwissADME predictions showed that DHG complies with Lipinski’s rule of five, indicating good oral bioavailability.

Figure 6.

SwissADME analysis of DHG. The canonical SMILES for DHG were retrieved from PubChem and entered into SwissADME. Output files and visualizations were directly from the website. (A) The BOILED-Egg model evaluated human intestinal absorption (HIA) and blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability based on lipophilicity and polarity, generating a WLOGP versus tPSA plot. (B) SwissADME predictions showed that DHG complies with Lipinski’s rule of five, indicating good oral bioavailability.

Figure 7.

Network pharmacological assessment of DHG. (A) Venn diagram showing the intersection between predicted targets of DHG and platelet-related genes, where 25 overlapping genes were identified. (B) Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of the 25 common targets constructed using the STRING database. (C) Compound–target–pathway network illustrating the association between DHG, its core targets, and enriched KEGG pathways.

Figure 7.

Network pharmacological assessment of DHG. (A) Venn diagram showing the intersection between predicted targets of DHG and platelet-related genes, where 25 overlapping genes were identified. (B) Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of the 25 common targets constructed using the STRING database. (C) Compound–target–pathway network illustrating the association between DHG, its core targets, and enriched KEGG pathways.

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of DHG-mediated inhibition of platelet signaling pathways. DHG inhibits platelet aggregation while reducing ATP release, intracellular Ca2+ mobilization, αIIbβ3 integrin activation, clot retraction, and activation of the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways.

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of DHG-mediated inhibition of platelet signaling pathways. DHG inhibits platelet aggregation while reducing ATP release, intracellular Ca2+ mobilization, αIIbβ3 integrin activation, clot retraction, and activation of the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways.