1. Introduction

Amyloidosis is classified according to the type of amyloid precursor protein, the pattern of deposition (systemic or localized), and whether it is hereditary or acquired [

1]. Localized amyloid deposits occur not only in various organs associated with certain disorders but also in the same tissues as part of normal aging [

2]. Furthermore, localized amyloid deposition may function as a waste container ("wasteosome") [

3,

4]. Thus, distinct mechanisms may underlie the formation, degradation, and elimination of localized amyloid deposits under different conditions. Elucidating the pathogenesis of localized amyloidosis could contribute to advancements in amyloid removal therapy. However, compared with systemic amyloidosis, localized amyloidosis remains insufficiently explored.

Localized amyloid deposition occurs in cardiovascular organs. Age-related amyloid deposition, including lactadherin (medin)-derived and apolipoprotein A-I-derived amyloid (AApoAI), takes place in large arteries [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Additionally, amyloid deposition has been reportedly associated with atherosclerosis and thrombotic materials in cardiovascular organs [

9]. These amyloid deposits are resistant to permanganate treatment, with their deposition pattern suggesting to be originating from components within the thrombus [

9]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the precursor proteins of thrombus-associated amyloid deposition have not yet been analyzed using immunohistochemistry (IHC) based on proteomic analysis using laser microdissection with liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LMD with LC-MS/MS).

Hence, in this study, we first examined the frequency and extent of amyloid deposition associated with thrombus formation, followed by conducting proteomic analysis on two patients with high amyloid deposition and sufficient sample volume. Finally, on the basis of these results, we conducted IHC analysis on patients with some degree of amyloid deposition and evaluated the findings.

2. Results

2.1. General Appearance of Thrombus-Associated Amyloid Deposition

We selected 6 aortic aneurysms with thrombi; 7 and 11 cases of internal carotid and coronary artery stenosis, respectively, with fibroatheroma showing hemorrhage and thrombus formation; 2 true brain aneurysms with thrombi; pulmonary and leg venous thrombi from 6 cases of pulmonary thromboembolism; and 4 other large artery aneurysm cases with thrombi from the archives of patients with medicolegal autopsy in our department.

Table 1 summarizes the clinical information and the frequency of amyloid deposition in these cases.

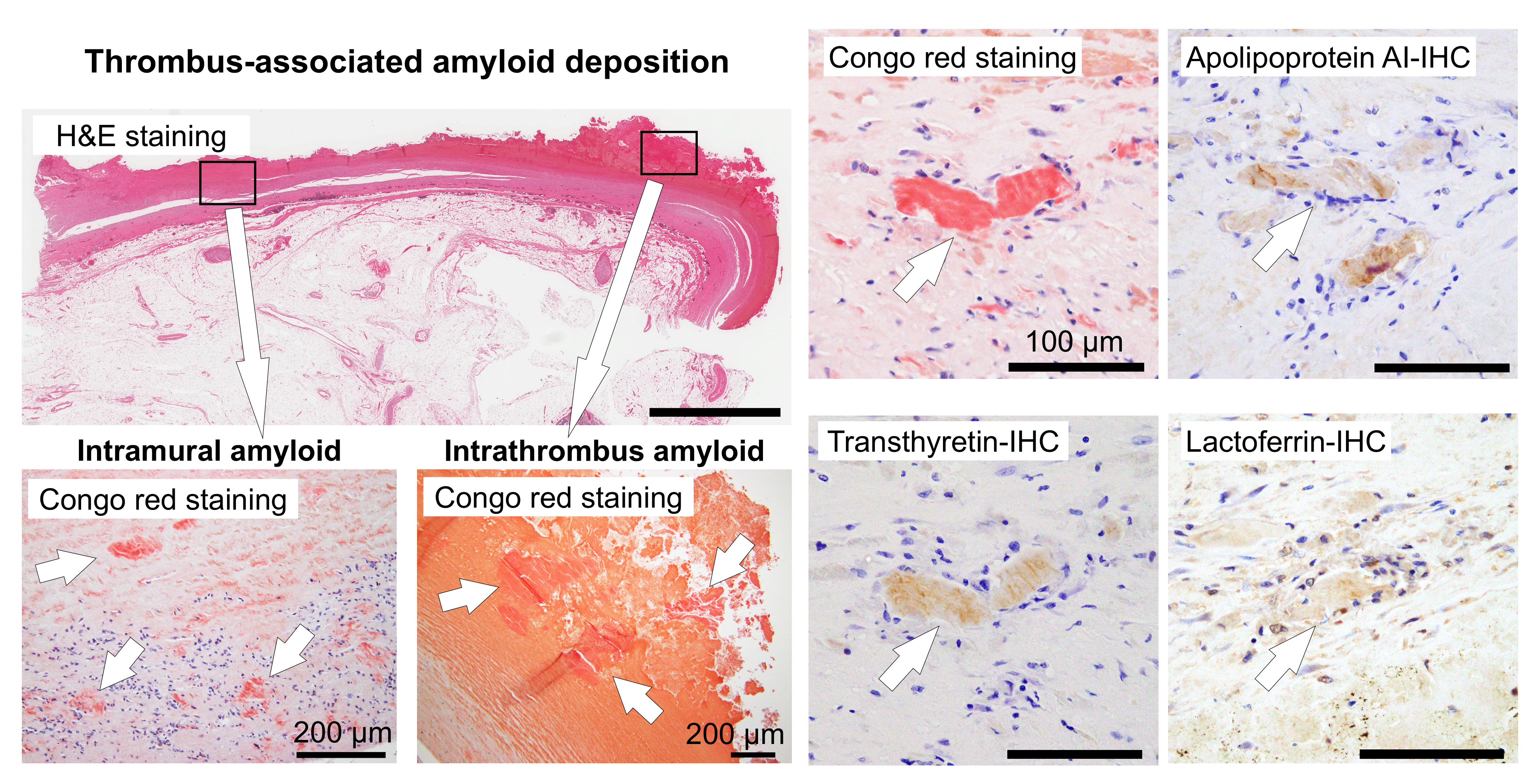

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show the representative micrographs of thrombus-associated amyloid deposition in the aorta and other large arteries, respectively.

As previously reported [

9], amyloid deposition occurred in both less organized and hyalinized thrombi, as well as in the area between the sclerotic replacement of the thrombus and the vessel wall (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). However, it was not observed in the intracranial, pulmonary, and lower extremity vessels, where atherosclerosis was not prominent. Apart from thrombus-associated amyloid deposition, four patients had systemic sporadic transthyretin-derived amyloid (ATTR) deposition, and none had a medical history of familial amyloidosis.

2.2. Characteristic Pathological Findings by the Amyloid Deposition Area

To further understand the histopathological characteristics of amyloid deposition associated with thrombi, we evaluated the histological findings at each deposition site.

Table 2 summarizes the results.

Nineteen specimens from 18 cases had amyloid deposition, which was located solely in the intrathrombus region in 4 cases, in the border to the intravascular wall region in 3 cases, and in both regions in 12 cases. Generally, amyloid deposition was more severe in the border area to the vessel wall than within the thrombus, but the difference was not significant (

p = 0.39). Six cases demonstrated phagocytosis of the deposits by histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells.

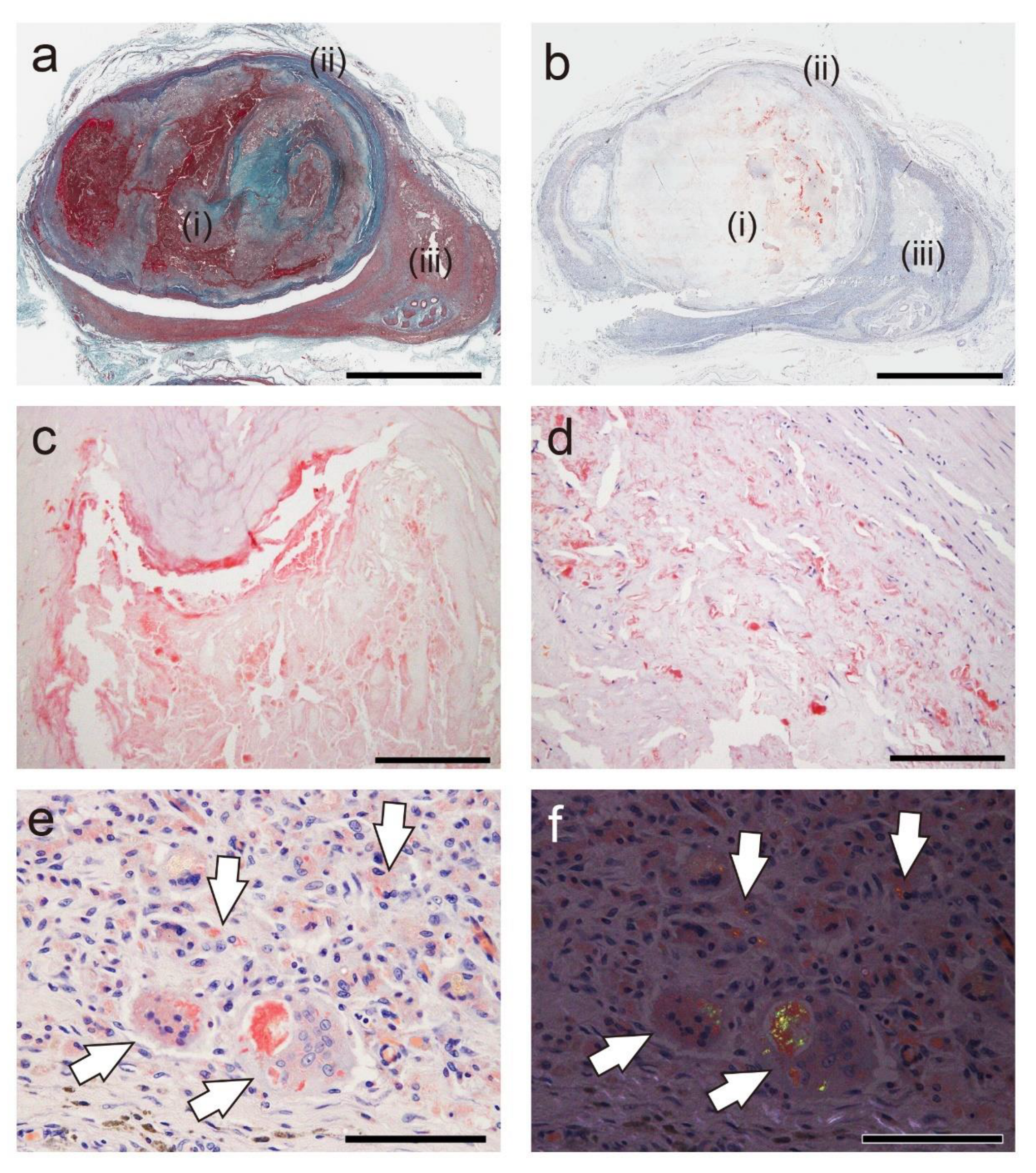

Figure 3 presents representative photographs showing the association between thrombus-associated amyloid deposits and phagocytes.

Interestingly, little or no phagocyte infiltration was observed around the amyloid deposits in the thrombus (

Figure 3a–c), but it was evident around the amyloid deposits within the vessel wall (

Figure 3d). Furthermore, granulomas formed in the perivascular area, and macrophages and multinucleated giant cells phagocytosed fragmented amyloid deposits in the area (

Figure 3f and f).

Figure 4 shows a case with findings showing an interesting association between amyloid deposits and phagocytes.

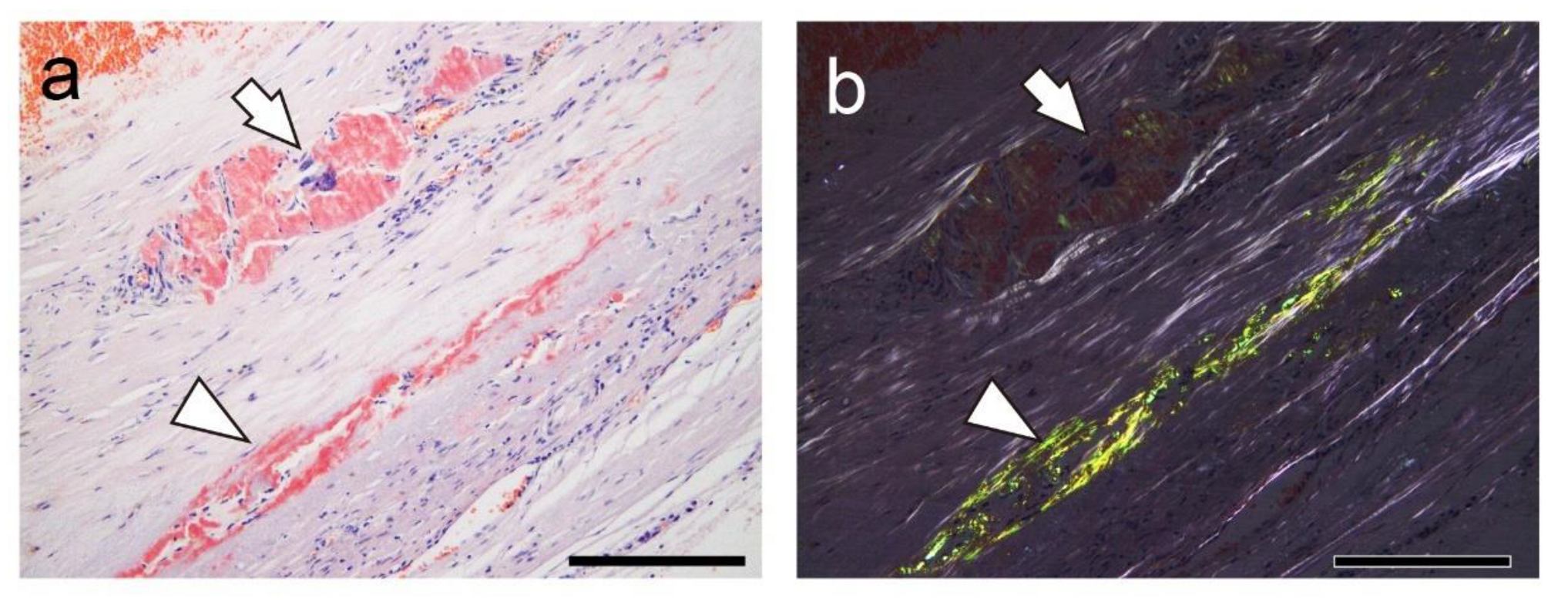

In this case, amyloids deposited in the vessel wall, both with and without surrounding histiocyte or multinucleated giant cell infiltration (

Figure 4a). Interestingly, under polarized light, the intensity of apple-green birefringence was lower in the deposits associated with phagocytic cells than in those without, suggesting the inflammation-induced degradation of amyloid fibrils (

Figure 4b).

2.3. Proteomic and Immunohistochemical Features of Thrombus-Associated Amyloid Deposition

First, in a representative case (Case 18), we attempted IHC using antibodies employed in the Japanese amyloidosis consultation system [

10], but no clear immunoreactivity was observed. Therefore, we conducted proteomic analysis using LMD with LC-MS/MS, as previously described [

11].

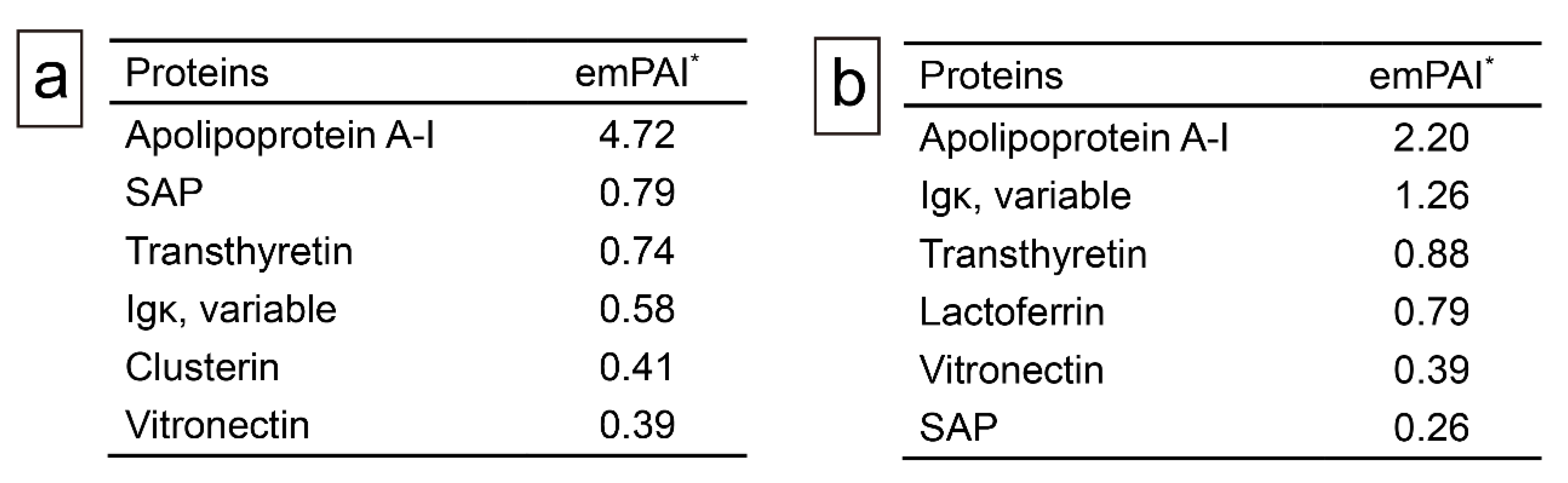

Figure 5 summarizes the analyses for Cases 18 and 19.

In addition to several amyloid-associated proteins, four proteins with potential amyloidogenic properties were detected (

Figure 5a,b). Both cases showed no lactadherin (medin). The presence of these deposits in pathological specimens was confirmed by IHC performed on cases with some degree of amyloid deposition (Grade ≥ 2+) using commercially available monoclonal antibodies previously reported to show positivity in amyloid deposits [

4,

12,

13,

14,

15].

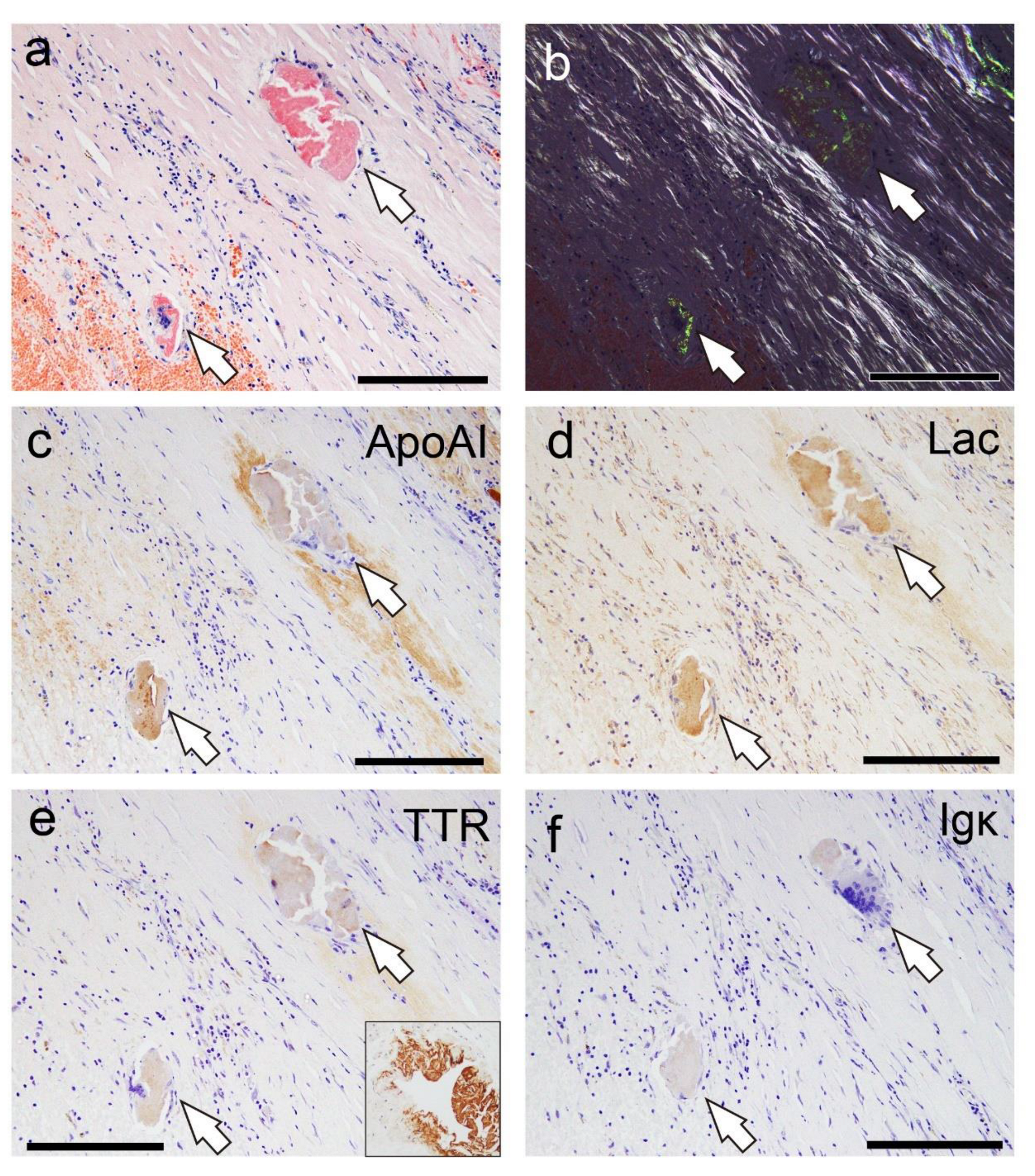

Figure 6 shows the representative IHC findings, while

Table 3 summarizes the analysis results.

All cases were mainly positive of ApoAI, followed by lactoferrin (75%/88%) and transthyretin (50%/50%), in both intrathrombus and border-to-intramural amyloids. No case showed immunoreactivity for Igκ. However, in all cases, the immunoreactivity in the thrombus-associated amyloid deposits was weak to moderate and lacked uniformity (

Figure 6a–f), with no areas exhibiting strong immunoreactivity throughout the deposits, as observed in the systemic ATTR deposition foci (

Figure 6e, Case 1). Furthermore, all examined organs, including the kidneys, of all cases showed no finding suggestive of hereditary AApoAI amyloidosis complications [

16]. These results suggest that these localized amyloid deposits are primarily composed of AApoAI, with a mixture of amyloid fibrils derived from amyloidogenic proteins circulating in the blood.

3. Discussion

This study demonstrated that thrombus-associated amyloid deposits are primarily composed of AApoAI, with a mixture of amyloid fibrils derived from circulating amyloidogenic proteins. These findings align with previous reports of AApoAI deposition in atherosclerotic foci of the aorta and internal carotid artery, suggesting that these lesions also originate from ApoAI in the blood [

5,

6,

17]. The dissociation of native TTR tetramers into monomers leads to amyloid fibril formation [

18]. Thus, during thrombus formation and its subsequent degeneration, structural changes in amyloidogenic proteins in the blood may have contributed to amyloid formation. This supports the hypothesis proposed by Goffin et al., that is, certain thrombus components undergo transformation into amyloid fibrils during the aging process of the thrombi [

9]. Notably, in the present study, amyloid formation within the thrombus was observed only in vessels with atherosclerosis, strongly suggesting that atherosclerosis plays a role in its development. Considering this pathology, amyloid deposition might be intensified by recurrent thrombus formation caused by atherosclerosis [

19], making it detectable histopathologically. The impact of amyloid formation within the thrombus remains unclear, but it may contribute to thrombus instability. Hence, further investigation is needed.

Of note, although Goffin et al. provided a detailed histopathological distribution of amyloids, the precursor proteins were not identified, and to the best of our knowledge, this amyloid deposition has not yet been analyzed in detail in nearly 40 years [

9]. As we have previously reported, amyloid precursor proteins that are difficult to determine using histopathological methods alone can be identified by combining IHC and proteomics using LMD with LC-MS/MS [

20,

21].

Interestingly, ATTR and AApoAI have been reported to be codeposited in musculoskeletal diseases such as spinal canal stenosis and knee osteoarthritis [

8,

12,

22]. Our findings suggest that amyloid deposition at these sites may result from precursor proteins leaking from the blood vessels and undergoing structural changes resulting from mechanical stress and inflammation. Notably, phagocytic infiltration around the amyloid deposits is not evident in the micrographs in these previous reports, consistent with our observations. This finding is particularly interesting because it differs from localized immunoglobulin light chain–derived amyloidosis, in which multinucleated giant cells may play a crucial role [

23]. These findings support previous reports suggesting a cross-seeding mechanism between AApoAI and ATTR, where each promotes the deposition of the other [

12]. The effects of these amyloid deposits on musculoskeletal tissues and thrombi, particularly regarding tissue damage and thrombus resolution, remain unclear, thereby warranting further investigation.

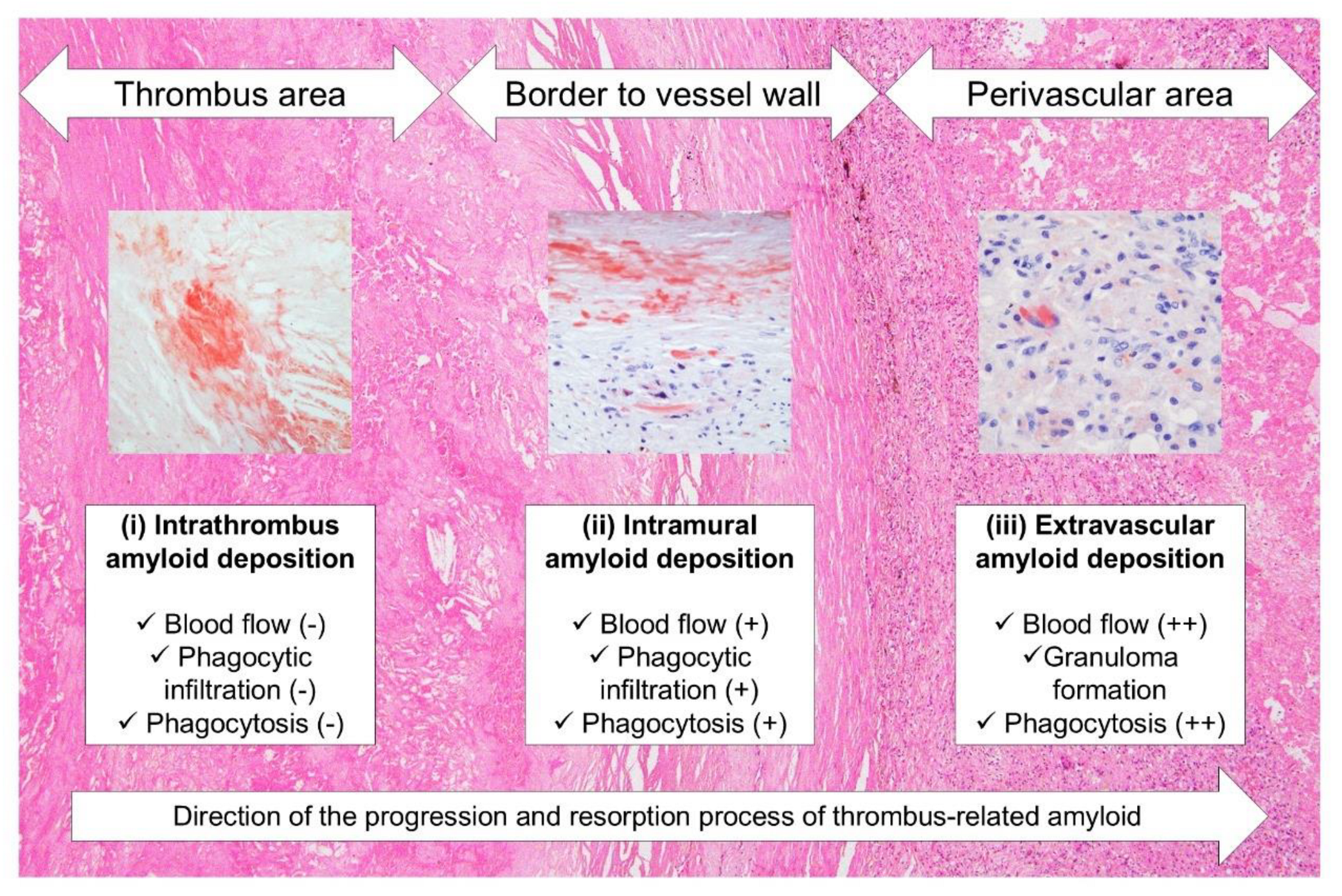

Unlike intrathrombus amyloid deposition foci, phagocytes were observed surrounding the amyloid in the vessel wall. Additionally, granulomas were noted forming in the perivascular area of a very old thrombus-occluded aneurysm, as well as amyloid fragments phagocytosing in the foci. In recent years, several reports have implicated inflammatory cell infiltration with multinucleated giant cells in removing amyloid deposits [

24,

25,

26,

27]. On the basis of our findings and the results of previous reports [

9], amyloids generated within the thrombus might undergo the following processes. First, amyloids generated within the thrombus resist digestive enzymes during thrombus organization and become trapped in dense sclerotic appositional tissue. At this stage, the blood flow to the amyloid deposits is nearly blocked, preventing them from accessing the deposits; hence, slight inflammation or phagocytosis occurs. The amyloids are then gradually degraded and absorbed by phagocytes from the vasa vasorum and/or recanalized vessels resulting from the organization of the surrounding thrombotic tissue. The unabsorbed portion is transported to the perivascular area, where blood flow is more abundant, and is processed by more phagocytes.

Figure 7 illustrates this hypothesis.

Of note, progressive degradation and resorption associated with inflammation may obscure amyloid deposition in pathological specimens [

26]. Under polarized light, we noticed reduced birefringence in amyloid deposits with surrounding phagocytic infiltration, and some lesions could not be histologically confirmed as amyloid. In thrombus-associated amyloid deposition, the immunoreactivity was not uniform and varied between the deposition areas. Similarly, previous histopathological studies of spinal canal stenosis and knee osteoarthritis have reported cases wherein amyloid could not be typed [

12], possibly because of degeneration. Future research is needed to enhance the sensitivity of histopathological detection in such cases.

This study has some limitations. In addition to potential biases in our study population, it has a small number of cases with moderate or greater amyloid deposition. Furthermore, we lacked a reliable antibody against the variable region of Igκ, which likely prevented amyloid detection by IHC. Additionally, we could not analyze the ApoAI and TTR genes; hence, we could not rule out the possibility of hereditary amyloid deposition cases associated with these mutations.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated the immunohistochemical characteristics of thrombus-associated localized amyloid deposition according to proteomic analysis using LMD with LC-MS/MS. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to reveal that thrombus-associated amyloids are composed of multiple amyloidogenic proteins. This combined approach is highly effective for identifying precursor proteins in previously uncharacterized amyloid deposits in histopathological specimens. Further research on localized amyloidosis is warranted, considering that precursor protein typing may enhance our understanding of amyloidogenesis. Additionally, phagocytic cells may play a key role in removing localized amyloid deposits. Clarifying their function is necessary to improve the efficacy of amyloid removal therapies, particularly for localized amyloids such as amyloid-β in which phagocytes are associated with amyloid removal [

27].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subjects

We retrospectively examined the autopsy records in our laboratory documented between 2009 and 2023. Data on patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics (including the cause of death) were retrieved from the medical records of police examinations and contributions from family members or from the primary physician if a record indicated clinic visits.

4.2. Tissue Samples

We fixed the specimens in 20% buffered formalin and routinely embedded them in paraffin. Then, they were sectioned at 4 μm thick, followed by hematoxylin–eosin staining, elastica–Masson staining, or IHC. We also prepared 6 μm-thick sections for phenol Congo red (pCR) staining [

28].

4.3. Semiquantitative Grading System for Thrombus- and Atheromatous-Plaque–Associated Amyloid Deposition

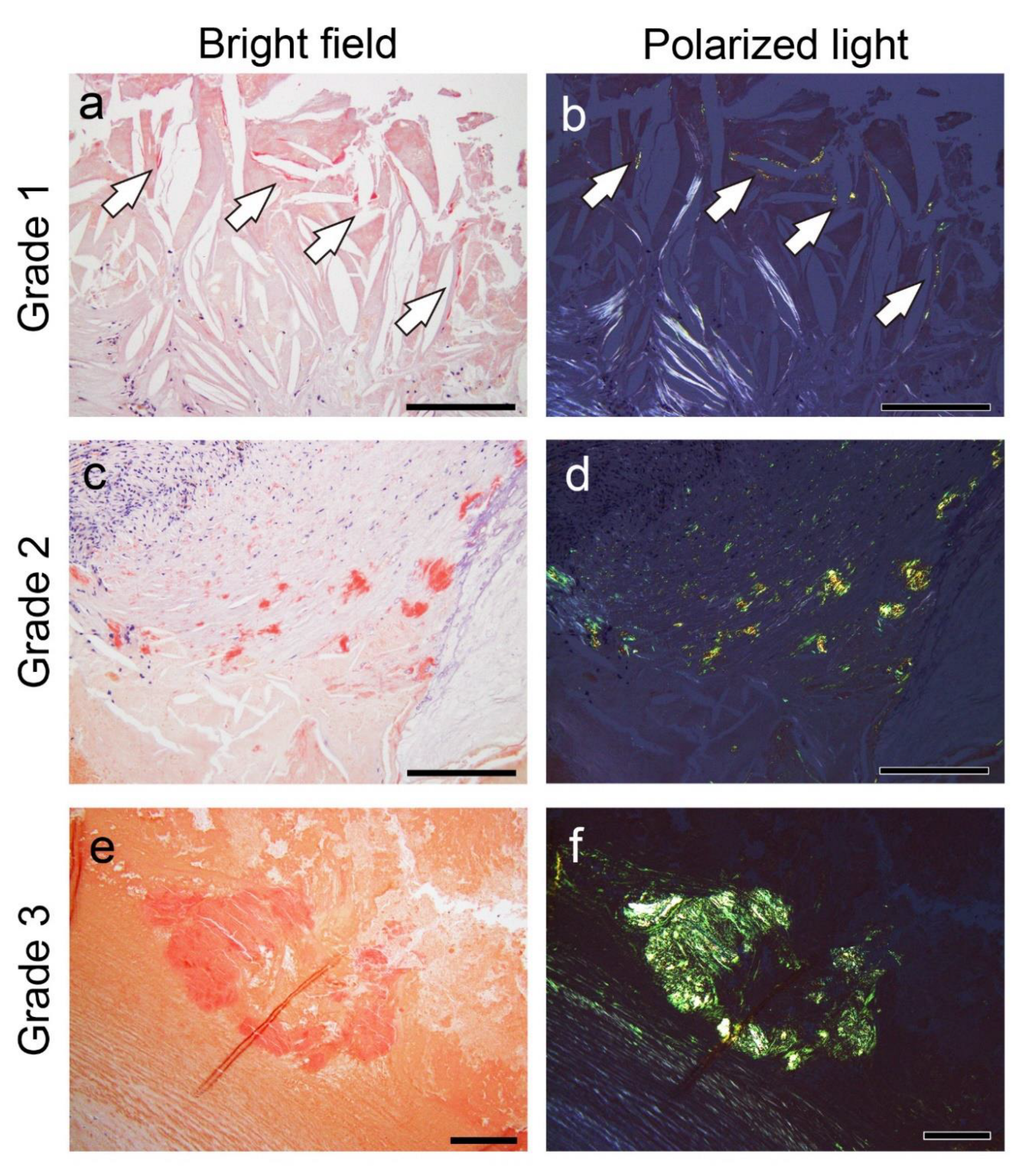

Following amyloid deposition confirmation by pCR staining, we assessed semiquantitatively the severity of the amyloid deposition in the thrombus or fibroatheroma with hemorrhage and the area between the sclerotic replacement of the thrombus to the adventitia of the vessel. For this evaluation, we used a 4-point scoring system as follows:

Grade 0, none;

Grade 1+, focal and tiny amyloid deposition;

Grade 2+, multifocal deposition with nodular deposits; and

Grade 3+, multifocal deposition with some massive deposits.

Figure 8 shows representative microphotographs illustrating the deposition patterns of this grading system.

Furthermore, the intensity of immunoreactivity in the amyloid deposits was assessed using a 4-point scoring system as follows: Grade 0, negative; Grade 1+, weak; Grade 2+, moderate; and Grade 3+, strong. In this evaluation system, the intensity of immunoreactivity in the small vessels of patients with systemic ATTR was defined as grade 3+ and compared with that shown in

Figure 5e inset.

4.4. IHC

For IHC, we used primary antibodies against ApoAI (rabbit, clone EP1368Y, 1:4000[ Abcam, Cambridge, UK), Igκ (rabbit, clone H16-E, 1:500; DB Biotech, Kosice, Slovak Republic), lactoferrin (mouse, clone B97, 1:150; Santa Cruz, TX, US), and prealbumin (TTR) (rabbit, clone EPR3219, 1:2000; Abcam).

Table 4 summarizes the details of the IHC methods.

4.5. Proteomics Analysis Using Mass Spectrometry

Amyloid deposition in the thrombus and in the border area to the vessel wall was analyzed using LMD followed by LC-MS/MS. The methods used for LMD with LC-MS/MS were described previously [

11].

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics version 29 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). A two-tailed p-value below 0.05 was considered significant. Ordinal variables (pathological scores) were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Shojiro Ichimata; Data curation, Shojiro Ichimata; Formal analysis, Shojiro Ichimata; Funding acquisition, Shojiro Ichimata; Investigation, Shojiro Ichimata, Tsuneaki Yoshinaga, Mitsuto sato, Nagaaki Katoh, Fuyuki Kametani, Masahide Yazaki, and Yoshiki Sekijima; Methodology, Fuyuki Kametani; Project administration, Shojiro Ichimata; Resources, Yukiko Hata, and Naoki Nishida; Supervision, Naoki Nishida; Validation, Naoki Nishida; Visualization, Shojiro Ichimata; Writing–original draft, Shojiro Ichimata; Writing–review & editing, Tsuneaki Yoshinaga, Nagaaki Katoh, Fuyuki Kametani, Masahide Yazaki, Yoshiki Sekijima, Yukiko Hata and Naoki Nishida. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by a JSPS KAKENHI grant awarded to Shojiro Ichimata (grant number JP20K18979).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Toyama University (I2020006) and followed the ethical standards established in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and updated in 2008.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the nature of the forensic autopsy. However, to address ethical considerations as thoroughly as possible, we obtained approval from the University of Toyama Ethics Committee (I2020006) and posted an opt-out statement regarding the research on our department’s website (

http://www.med.u-toyama.ac.jp/legal/for_family.html).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Miyuki Maekawa and Yuki Komatsu for their technical assistance. The authors would also like to thank enago (

www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A |

Amyloid |

| ApoAI |

Apolipoprotein A-I |

| CaA |

Carotid artery |

| CoA |

Coronary artery |

| CrA |

Cranial artery |

| F |

Female |

| FHT |

Fibroatheroma with hemorrhage and thrombus |

| Igκ |

immunoglobulin κ light chain |

| IHC |

Immunohistochemistry |

| Lac |

Lactoferrin |

| LC-MS/MS |

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry |

| LMD |

Laser microdissection |

| M |

Male |

| PA |

Pulmonary artery |

| pCR |

Phenol Congo red |

| SAP |

Serum amyloid P-component |

| TTR |

Transthyretin |

| VLE |

Veins of the lower extremities |

References

- Buxbaum, J. N.; Eisenberg, D. S.; Fandrich, M.; McPhail, E. D.; Merlini, G.; Saraiva, M. J. M.; Sekijima, Y.; Westermark, P. Amyloid nomenclature 2024: Update, novel proteins, and recommendations by the International Society of Amyloidosis (ISA) Nomenclature Committee. Amyloid 2024, 31, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westermark, G. T.; Westermark, P. Localized amyloids important in diseases outside the brain--lessons from the islets of Langerhans and the thoracic aorta. FEBS J. 2011, 278, 3918–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riba, M.; Del Valle, J.; Auge, E.; Vilaplana, J.; Pelegri, C. From corpora amylacea to wasteosomes: History and perspectives. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 72, 101484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimata, S.; Hata, Y.; Yoshinaga, T.; Katoh, N.; Kametani, F.; Yazaki, M.; Sekijima, Y.; Nishida, N. Amyloid-forming corpora amylacea and spheroid-type amyloid deposition: Comprehensive analysis using immunohistochemistry, proteomics, and a literature review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermark, P.; Mucchiano, G.; Marthin, T.; Johnson, K. H.; Sletten, K. Apolipoprotein A1-derived amyloid in human aortic atherosclerotic plaques. Am. J. Pathol. 1995, 147, 1186–1192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mucchiano, G. I.; Häggqvist, B.; Sletten, K.; Westermark, P. Apolipoprotein A-1-derived amyloid in atherosclerotic plaques of the human aorta. J. Pathol. 2001, 193, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häggqvist, B.; Näslund, J.; Sletten, K.; Westermark, G. T.; Mucchiano, G.; Tjernberg, L. O.; Nordstedt, C.; Engström, U.; Westermark, P. Medin: An integral fragment of aortic smooth muscle cell-produced lactadherin forms the most common human amyloid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96, 8669–8674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, M.; Lavatelli, F.; Obici, L.; Obayashi, K.; Miyamoto, T.; Merlini, G.; Palladini, G.; Ando, Y.; Ueda, M. Age-related amyloidosis outside the brain: A state-of-the-art review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 70, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffin, Y. A.; Rickaert, F. Histotopographic evidence that amyloid deposits in sclerocalcific heart valves and other chronic lesions of the cardiovascular system are related to old thrombotic material. Virchows Arch. A Pathol. Anat. Histopathol. 1986, 409, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, R.; Katoh, N.; Takahashi, Y.; Takasone, K.; Yoshinaga, T.; Yazaki, M.; Kametani, F.; Sekijima, Y. Distribution of amyloidosis subtypes based on tissue biopsy site - Consecutive analysis of 729 patients at a single amyloidosis center in Japan. Pathol. Int. 2021, 71, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kametani, F.; Haga, S. Accumulation of carboxy-terminal fragments of APP increases phosphodiesterase 8B. Neurobiol. Aging 2015, 36, 634–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasaki, M.; Okada, M.; Yanagisawa, A.; Nomura, T.; Matsushita, H.; Ueda, A.; Inoue, Y.; Masuda, T.; Misumi, Y.; Yamashita, T.; Nakamura, T.; Miyamoto, T.; Obayashi, K.; Ando, Y.; Ueda, M. Apolipoprotein AI amyloid deposits in the ligamentum flavum in patients with lumbar spinal canal stenosis. Amyloid 2021, 28, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshii, Y.; Nanbara, H.; Cui, D.; Takahashi, M.; Ikeda, E. Immunohistochemical examination of Akappa amyloidosis with antibody against adjacent portion of the carboxy terminus of immunoglobulin kappa light chain. Med. Mol. Morphol. 2012, 45, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimata, S.; Aoyagi, D.; Yoshinaga, T.; Katoh, N.; Kametani, F.; Yazaki, M.; Uehara, T.; Shiozawa, S. A case of spheroid-type localized lactoferrin amyloidosis in the bronchus. Pathol. Int. 2019, 69, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimata, S.; Hata, Y.; Hirono, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Nishida, N. Clinicopathological features of clinically undiagnosed sporadic transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: A forensic autopsy-based series. Amyloid 2021, 28, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, O. C.; Blakeney, I. J.; Law, S.; Ravichandran, S.; Gilbertson, J.; Rowczenio, D.; Mahmood, S.; Sachchithanantham, S.; Wisniowski, B.; Lachmann, H. J.; Whelan, C. J.; Martinez-Naharro, A.; Fontana, M.; Hawkins, P. N.; Gillmore, J. D.; Wechalekar, A. D. The experience of hereditary apolipoprotein A-I amyloidosis at the UK National Amyloidosis Centre. Amyloid 2022, 29, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocken, C.; Tautenhahn, J.; Buhling, F.; Sachwitz, D.; Vockler, S.; Goette, A.; Burger, T. Prevalence and pathology of amyloid in atherosclerotic arteries. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 676–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekijima, Y. Transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis: Clinical spectrum, molecular pathogenesis and disease-modifying treatments. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2015, 86, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, A. P.; Kolodgie, F. D.; Farb, A.; Weber, D. K.; Malcom, G. T.; Smialek, J.; Virmani, R. Healed plaque ruptures and sudden coronary death: Evidence that subclinical rupture has a role in plaque progression. Circulation 2001, 103, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimata, S.; Katoh, N.; Abe, R.; Yoshinaga, T.; Kametani, F.; Yazaki, M.; Uehara, T.; Sekijima, Y. A case of novel amyloidosis: Glucagon-derived amyloid deposition associated with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour. Amyloid 2021, 28, 72–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimata, S.; Katoh, N.; Abe, R.; Yoshinaga, T.; Kametani, F.; Yazaki, M.; Kusama, Y.; Sano, K.; Uehara, T.; Sekijima, Y. Somatostatin-derived amyloid deposition associated with duodenal neuroendocrine tumour (NET): A report of novel localised amyloidosis associated with NET. Amyloid 2022, 29, 64–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, A.; Ueda, M.; Sueyoshi, T.; Nakamura, E.; Tasaki, M.; Suenaga, G.; Motokawa, H.; Toyoshima, R.; Kinoshita, Y.; Misumi, Y.; Yamashita, T.; Sakaguchi, M.; Westermark, P.; Mizuta, H.; Ando, Y. Knee osteoarthritis associated with different kinds of amyloid deposits and the impact of aging on type of amyloid. Amyloid 2016, 23, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermark, P. Localized AL amyloidosis: A suicidal neoplasm? Ups. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 117, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimata, S.; Hata, Y.; Nomoto, K.; Nishida, N. Transthyretin-derived amyloid (ATTR) and sarcoidosis: Does ATTR deposition cause a granulomatous inflammatory response in older adults with sarcoidosis? Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2024, 70, 107624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, M.; Gilbertson, J.; Verona, G.; Riefolo, M.; Slamova, I.; Leone, O.; Rowczenio, D.; Botcher, N.; Ioannou, A.; Patel, R. K.; Razvi, Y.; Martinez-Naharro, A.; Whelan, C. J.; Venneri, L.; Duhlin, A.; Canetti, D.; Ellmerich, S.; Moon, J. C.; Kellman, P.; Al-Shawi, R.; McCoy, L.; Simons, J. P.; Hawkins, P. N.; Gillmore, J. D. Antibody-associated reversal of ATTR amyloidosis-related cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2199–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimata, S.; Aikawa, A.; Sugishita, N.; Katoh, N.; Kametani, F.; Tagawa, H.; Handa, Y.; Yazaki, M.; Sekijima, Y.; Ehara, T.; Nishida, N.; Ishizawa, S. Enterocolic granulomatous phlebitis associated with epidermal growth factor-containing fibulin-like extracellular matrix protein 1 deposition and focal amyloid properties: A case report. Pathol. Int. 2024, 74, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, R. J.; Shanes, E. D.; McCord, M.; Reish, N. J.; Flanagan, M. E.; Mesulam, M. M.; Jamshidi, P. Neuropathology of anti-amyloid-beta immunotherapy: A case report. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2023, 93, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, W.; Matsuda, M.; Nakamura, N.; Katsumata, S.; Toriumi, H.; Suzuki, A.; Ikeda, S. Phenol congo red staining enhances the diagnostic value of abdominal fat aspiration biopsy in reactive aa amyloidosis secondary to rheumatoid arthritis. Intern. Med. 2003, 42, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

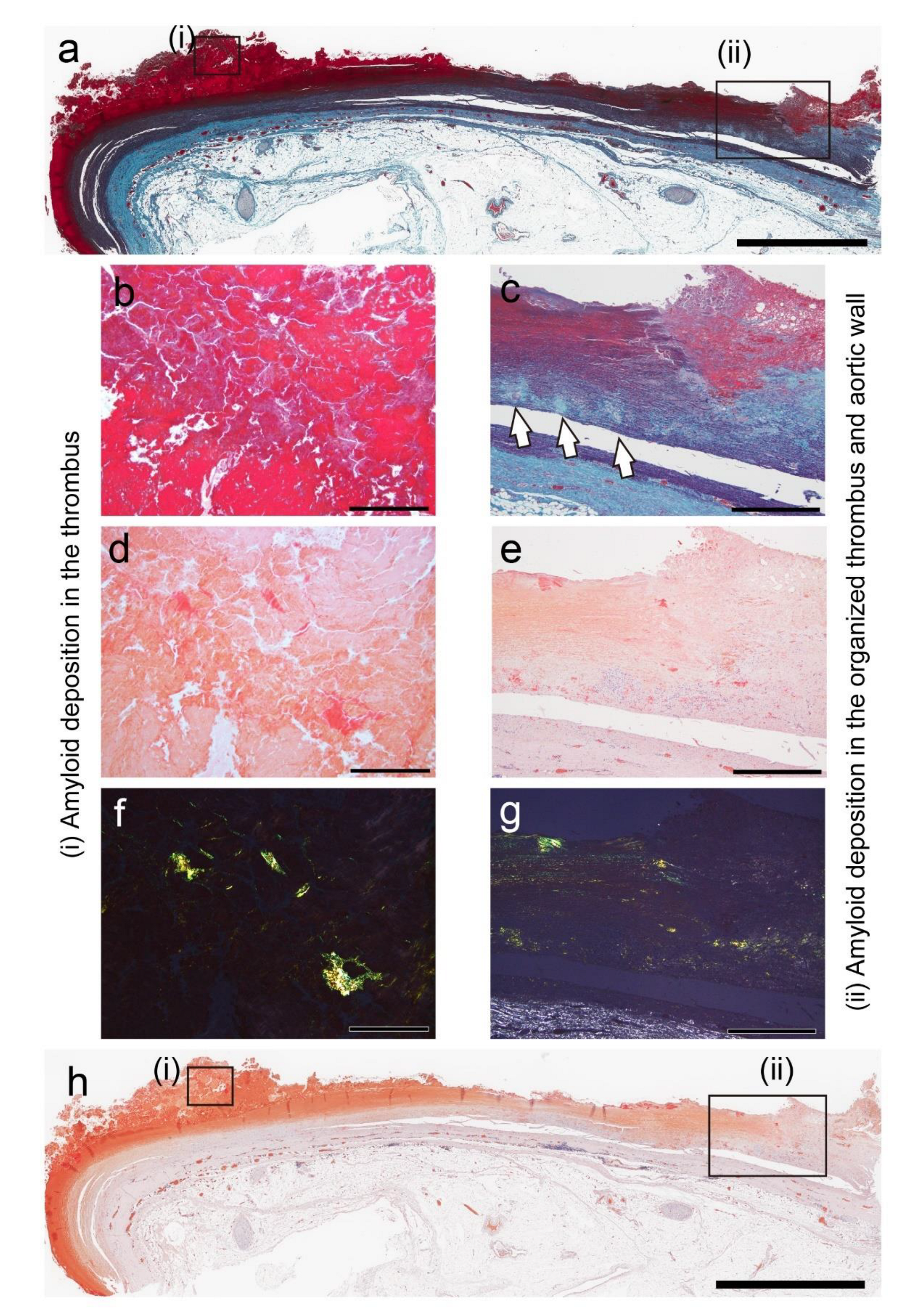

Figure 1.

Representative pathological findings in the aortic aneurysm (Case 2 in

Table 2). (

a–c) Elastica–Masson staining; (

d–h) phenol Congo red (pCR) staining under bright-field (

d, e, h) and polarized light (

f, g) observation. Medial elastic fibers are disrupted at the amyloid deposition site within the wall (

c, arrow). Scale bar = 5 mm (

a, h); 2 mm (

c, e, g); 200 μm (b, d, f).

Figure 1.

Representative pathological findings in the aortic aneurysm (Case 2 in

Table 2). (

a–c) Elastica–Masson staining; (

d–h) phenol Congo red (pCR) staining under bright-field (

d, e, h) and polarized light (

f, g) observation. Medial elastic fibers are disrupted at the amyloid deposition site within the wall (

c, arrow). Scale bar = 5 mm (

a, h); 2 mm (

c, e, g); 200 μm (b, d, f).

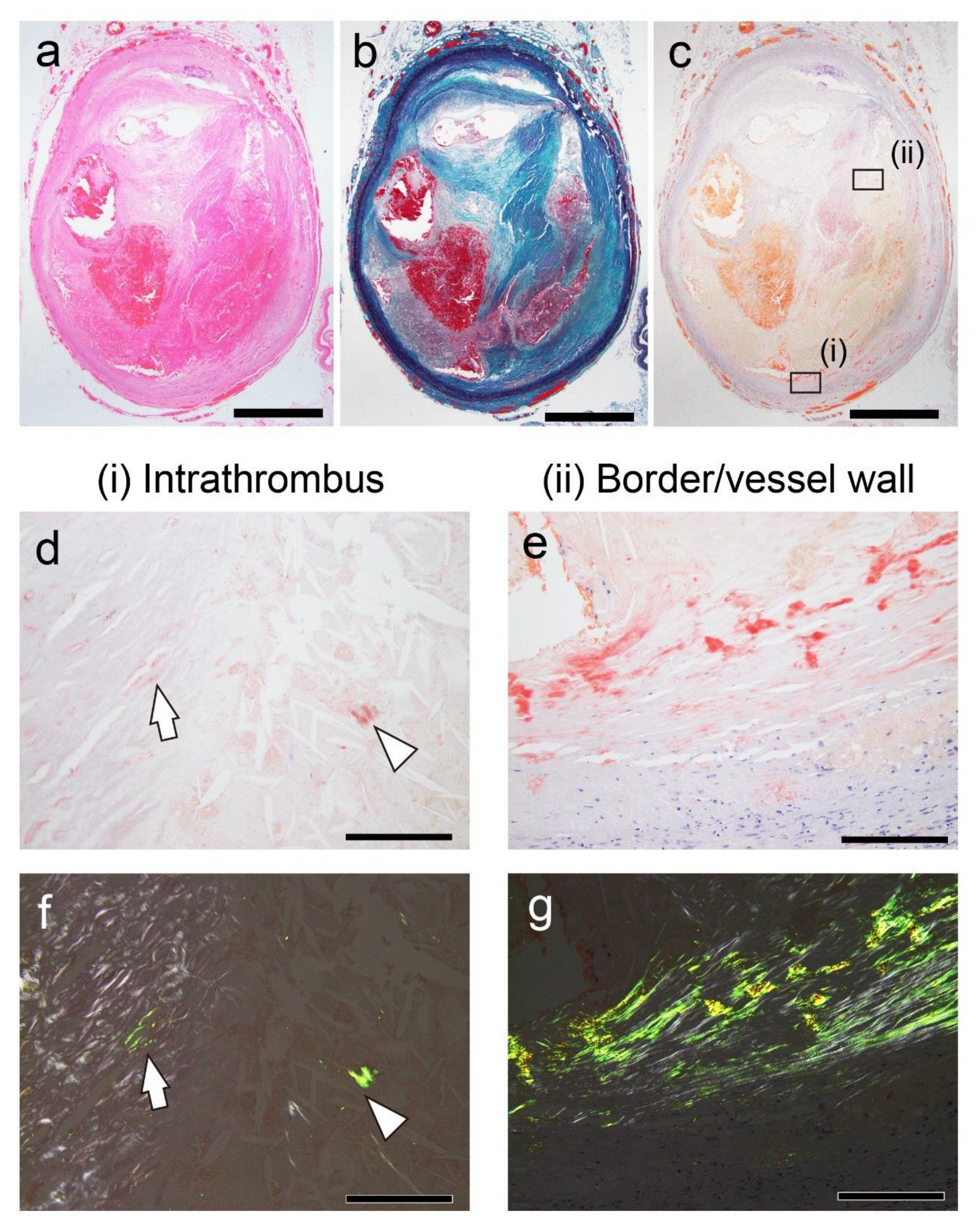

Figure 2.

Representative pathological findings in the internal carotid artery (Case 8 in

Table 2). (

a) Hematoxylin–eosin staining; (

b) Elastica–Masson staining; (

c–g) pCR staining under bright-field (

c–e) and polarized light (

f, g) observation. (

a–c) FHT formation is observed. (

d–g) The intrathrombus area and border/vessel wall area contain amyloid deposition. Scale bar = 2 mm (

a–c); 200 μm (

d–g).

Figure 2.

Representative pathological findings in the internal carotid artery (Case 8 in

Table 2). (

a) Hematoxylin–eosin staining; (

b) Elastica–Masson staining; (

c–g) pCR staining under bright-field (

c–e) and polarized light (

f, g) observation. (

a–c) FHT formation is observed. (

d–g) The intrathrombus area and border/vessel wall area contain amyloid deposition. Scale bar = 2 mm (

a–c); 200 μm (

d–g).

Figure 3.

Representative pathological findings of an arteriovenous fistula–related aneurysm in the forearm approximately 20 years after thrombus occlusion (Case 18). (a) Elastica–Masson staining; (b–e) pCR staining under bright-field (b–e) and polarized light (f) observation. (a, b) Amyloid deposition is observed in the thrombus (i), the border area to the vessel wall (ii), and the granuloma area (iii). Panels c, d, and e are higher-magnification views of the amyloid deposition foci in (i), (ii), and (iii), respectively. Notably, phagocyte infiltration is inevident around the amyloid deposits in the thrombus (c), but it is observed within the vessel wall (d). (e, f) Amyloid deposition is identified within the cytoplasm of macrophages and multinucleated giant cells in the granuloma area (arrows). Scale bar = 5 mm (a, b); 200 μm (c, d); 100 μm (e, f).

Figure 3.

Representative pathological findings of an arteriovenous fistula–related aneurysm in the forearm approximately 20 years after thrombus occlusion (Case 18). (a) Elastica–Masson staining; (b–e) pCR staining under bright-field (b–e) and polarized light (f) observation. (a, b) Amyloid deposition is observed in the thrombus (i), the border area to the vessel wall (ii), and the granuloma area (iii). Panels c, d, and e are higher-magnification views of the amyloid deposition foci in (i), (ii), and (iii), respectively. Notably, phagocyte infiltration is inevident around the amyloid deposits in the thrombus (c), but it is observed within the vessel wall (d). (e, f) Amyloid deposition is identified within the cytoplasm of macrophages and multinucleated giant cells in the granuloma area (arrows). Scale bar = 5 mm (a, b); 200 μm (c, d); 100 μm (e, f).

Figure 4.

Representative pathological findings showing a congophilic state at varying degrees among amyloid deposits (Case 4). (a, b) pCR staining under bright-field (a) and polarized light (b) observation. (a) Within the arterial wall, amyloid deposits are present, one area showing a prominent inflammatory cell infiltrate, including multinucleated giant cells (arrow), and another area exhibiting less phagocyte infiltration (arrowhead). Under bright-field observation, the congophilic state did not clearly differ between the two lesions. (b) Under polarized light, apple-green birefringence was weak in the former deposition area but was clear in the latter. Scale bar = 200 μm (a, b).

Figure 4.

Representative pathological findings showing a congophilic state at varying degrees among amyloid deposits (Case 4). (a, b) pCR staining under bright-field (a) and polarized light (b) observation. (a) Within the arterial wall, amyloid deposits are present, one area showing a prominent inflammatory cell infiltrate, including multinucleated giant cells (arrow), and another area exhibiting less phagocyte infiltration (arrowhead). Under bright-field observation, the congophilic state did not clearly differ between the two lesions. (b) Under polarized light, apple-green birefringence was weak in the former deposition area but was clear in the latter. Scale bar = 200 μm (a, b).

Figure 5.

Representative proteomics results. (a) Proteins identified in the intrathrombus amyloid deposition in Case 19; (b) proteins identified in amyloid deposition found in the border to vessel wall in Case 18. *emPAI stands for exponentially modified protein abundance index used to estimate relative protein quantification in mass spectrometry–based proteomics analysis. Igκ, immunoglobulin kappa light chain; SAP, serum amyloid P-component.

Figure 5.

Representative proteomics results. (a) Proteins identified in the intrathrombus amyloid deposition in Case 19; (b) proteins identified in amyloid deposition found in the border to vessel wall in Case 18. *emPAI stands for exponentially modified protein abundance index used to estimate relative protein quantification in mass spectrometry–based proteomics analysis. Igκ, immunoglobulin kappa light chain; SAP, serum amyloid P-component.

Figure 6.

Representative IHC findings in amyloid deposits (Case 4). (a, b) pCR staining under bright-field (a) and polarized light (b) observation. IHC for apolipoprotein A-I (ApoAI, c); lactoferrin (Lac, d); transthyretin (TTR, e); and immunoglobulin κ light chain (Igκ, f). Amyloid deposits in this case (a, b) are moderately positive for ApoAI (c) and Lac (d), weakly positive for TTR (e), and negative for Igκ (f). (e) TTR immunoreactivity in thrombus-associated amyloid deposits is significantly weaker than that observed in patients with systemic ATTR amyloidosis (Case 1) that underwent IHC at the same time as the control with IHC-grade 3+ (inset). Scale bar = 200 μm (a–f).

Figure 6.

Representative IHC findings in amyloid deposits (Case 4). (a, b) pCR staining under bright-field (a) and polarized light (b) observation. IHC for apolipoprotein A-I (ApoAI, c); lactoferrin (Lac, d); transthyretin (TTR, e); and immunoglobulin κ light chain (Igκ, f). Amyloid deposits in this case (a, b) are moderately positive for ApoAI (c) and Lac (d), weakly positive for TTR (e), and negative for Igκ (f). (e) TTR immunoreactivity in thrombus-associated amyloid deposits is significantly weaker than that observed in patients with systemic ATTR amyloidosis (Case 1) that underwent IHC at the same time as the control with IHC-grade 3+ (inset). Scale bar = 200 μm (a–f).

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the hypothesized progression and resorption process of thrombus-associated amyloids.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the hypothesized progression and resorption process of thrombus-associated amyloids.

Figure 8.

Representative microphotographs of thrombus-associated amyloid deposition evaluated using the grading system employed in this study. (a–f) pCR staining under bright-field (a, c, e) and polarized light (b, d, f) observation. (a, b) Grade 1+, focal and tiny amyloid deposition; (c, d) Grade 2+, multifocal deposition with nodular deposits; (e, f) Grade 3+, multifocal deposition with some massive deposits. Scale bar = 200 μm (a–f).

Figure 8.

Representative microphotographs of thrombus-associated amyloid deposition evaluated using the grading system employed in this study. (a–f) pCR staining under bright-field (a, c, e) and polarized light (b, d, f) observation. (a, b) Grade 1+, focal and tiny amyloid deposition; (c, d) Grade 2+, multifocal deposition with nodular deposits; (e, f) Grade 3+, multifocal deposition with some massive deposits. Scale bar = 200 μm (a–f).

Table 1.

Summary of the evaluated cases.

Table 1.

Summary of the evaluated cases.

| |

Aorta*

|

CaA |

CoA**

|

CrA**

|

PA/VLE |

Other***

|

| Age (range) |

80.2 ± 8.8 (71–97) |

79.0 ± 4.9 (72–88) |

72.2 ± 12.8 (47–93) |

39.0 ± 8.0 (31–47) |

49.3 ± 20.4 (22–81) |

76.5 ± 17.8 (47–92) |

| Sex (F/M) |

3/3 |

1/6 |

1/10 |

0/2 |

4/2 |

0/4 |

| ATTR-CA-positive (%) |

2 (33) |

1 (14) |

1 (9) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Number of positive cases for amyloid deposition (%) |

| Thrombus/FHT |

3 (50) |

3 (43) |

6 (55) |

0 |

0 |

3 (75) |

| Border/vessel wall****

|

3 (50) |

4 (57) |

5 (45) |

0 |

0 |

3 (75) |

Table 2.

Summary of pathological severity in amyloid deposition–positive cases.

Table 2.

Summary of pathological severity in amyloid deposition–positive cases.

| Case# |

Age |

Sex |

Anatomical site |

Location and severity of amyloid deposition*

|

| Thrombus/FHT |

Border/vessel wall |

Phagocytosis |

| 1 |

97 |

F |

Abdominal aorta |

1+ |

1+ |

Positive |

| 2 |

83 |

M |

Thoracic aorta |

3+ |

3+ |

Positive |

| 3 |

81 |

M |

Abdominal aorta |

1+ |

1+ |

Negative |

| 4 |

78 |

M |

Abdominal aorta |

1+ |

3+ |

Positive |

| 5 |

78 |

F |

Internal carotid artery |

0 |

1+ |

Negative |

| 6 |

75 |

M |

Internal carotid artery |

1+ |

1+ |

Negative |

| 7 |

77 |

M |

Internal carotid artery |

1+ |

1+ |

Negative |

| 8 |

83 |

M |

Internal carotid artery |

2+ |

3+ |

Positive |

| 9 |

80 |

M |

Right coronary artery |

1+ |

2+ |

Negative |

| 10 |

79 |

F |

Left coronary artery |

1+ |

0 |

Negative |

| 11 |

66 |

M |

Left coronary artery |

1+ |

0 |

Negative |

| 12 |

73 |

M |

Left coronary artery |

1+ |

2+ |

Negative |

| 13 |

72 |

M |

Right coronary artery |

1+ |

0 |

Negative |

| 14 |

93 |

M |

Left coronary artery |

1+ |

0 |

Negative |

| 15**

|

47 |

M |

Right coronary artery |

0 |

1+ |

Negative |

| 16 |

65 |

M |

Right coronary artery |

0 |

1+ |

Negative |

| 17 |

89 |

M |

Internal iliac artery |

1+ |

2+ |

Negative |

| 18**

|

47 |

M |

Arteriovenous fistula |

2+ |

3+ |

Positive |

| 19 |

92 |

M |

Common iliac artery |

2+ |

3+ |

Positive |

Table 3.

Summary of immunohistochemical analysis results.

Table 3.

Summary of immunohistochemical analysis results.

| Case# |

Severity*

|

Intrathrombus/FHT amyloid**

|

Boder/vessel wall amyloid**

|

| ApoAI |

Lac |

TTR***

|

Igκ |

ApoA1 |

Lac |

TTR***

|

Igκ |

| 2 |

3+/3+ |

2+ |

1+ |

1+ |

0 |

2+ |

1+ |

1+ |

0 |

| 4 |

1+/3+ |

NE |

NE |

NE |

NE |

2+ |

2+ |

1+ |

0 |

| 8 |

2+/3+ |

2+ |

1+ |

0 |

0 |

2+ |

1+ |

0 |

0 |

| 9 |

1+/2+ |

NE |

NE |

NE |

NE |

2+ |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 12 |

1+/2+ |

NE |

NE |

NE |

NE |

1+ |

1+ |

0 |

0 |

| 17 |

1+/2+ |

NE |

NE |

NE |

NE |

1+ |

1+ |

0 |

0 |

| 18 |

2+/3+ |

2+ |

1+ |

0 |

0 |

2+ |

1+ |

1+ |

0 |

| 19 |

2+/3+ |

1+ |

0 |

1+ |

0 |

2+ |

1+ |

1+ |

0 |

Table 4.

Summary of the antibodies and IHC methods used in this study.

Table 4.

Summary of the antibodies and IHC methods used in this study.

| Antibody |

Source |

Clone |

Dilution |

Antigen retrieval |

References |

| Apolipoprotein A-I |

Abcam |

EP1368Y |

1:4000 |

98% FA (1 min) |

[12] |

| Immunoglobulin κ light chain |

DB Biotech |

H16-E |

1:500 |

98% FA (1 min) |

[13] |

| Lactoferrin |

Santa Cruz |

B97 |

1:150 |

98% FA (1 min) |

[4,14] |

| Prealbumin |

Abcam |

EPR3219 |

1:2000 |

98% FA (1 min) |

[15] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).