Meselson Center

RAND Global and Emerging Risks is a division of RAND that delivers rigorous and objective public policy research on the most consequential challenges to civilization and global security. This work was undertaken by the division’s Meselson Center, which is dedicated to reducing risks from biological threats and emerging technologies. The center combines policy research with technical research to provide policymakers with the information needed to prevent, prepare for, and mitigate large-scale catastrophes. For more information, contact meselson@rand.org.

Summary

The Meselson Center (MC) at RAND has developed a working paper to address the growing risks posed by biosecurity information hazards—research findings that, while scientifically valuable, could be misused to cause significant harm. These hazards are especially concerning in fields like synthetic biology, artificial intelligence in biotechnology, and other emerging fields in the life sciences where access to sensitive knowledge can potentially aid malicious actors in creating a biothreat. Despite these risks, many institutions lack a systematic and operational approach to decide whether such information should be disclosed publicly. This working paper describes a living framework to evaluate and manage the risks associated with biosecurity information disclosures.

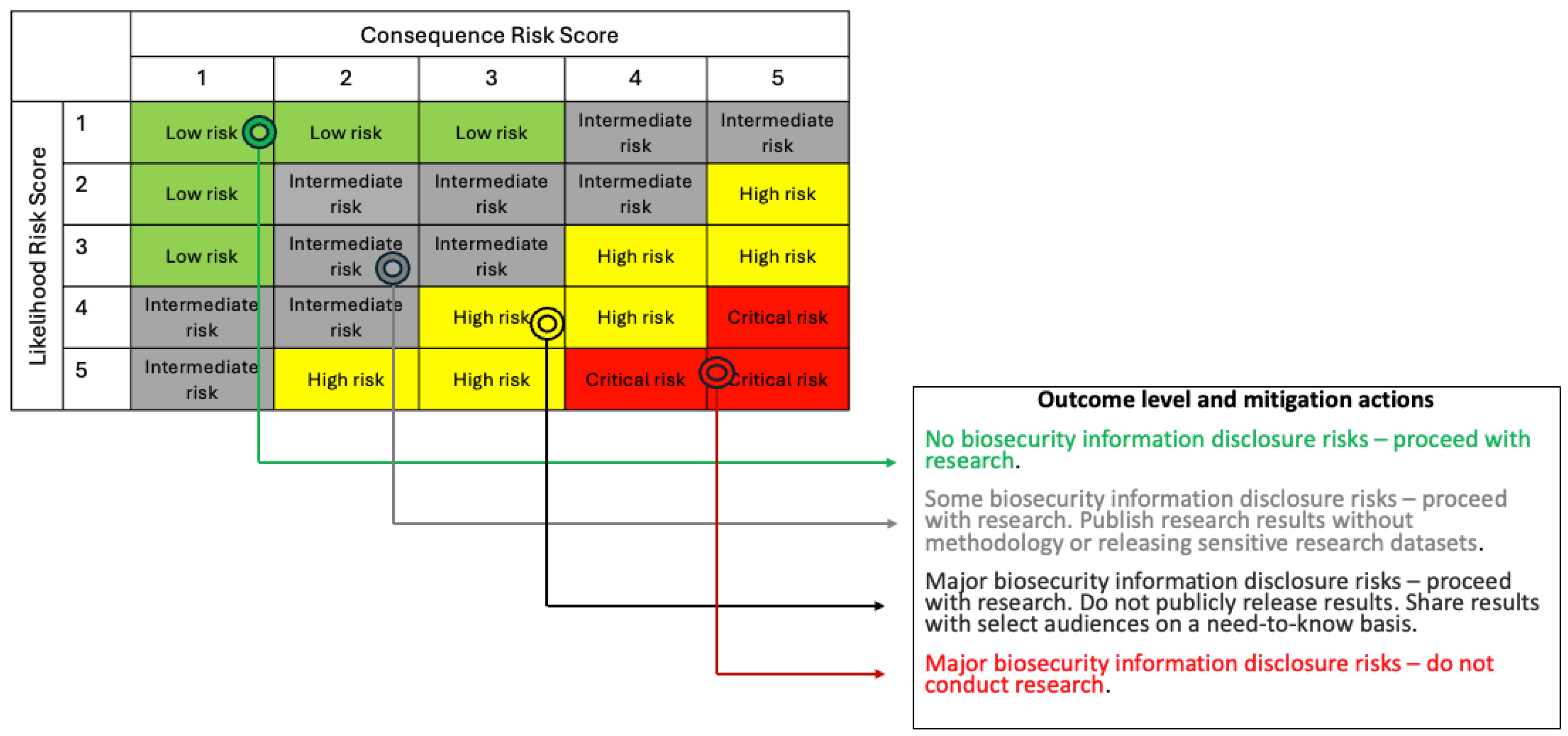

At the core of the framework is a two-part, tiered assessment system that helps scientists, funders, and research managers identify and evaluate potential information hazards before, during, and after a research project. The cyclical and staged review structure ensures that biosecurity risks are not only identified early but monitored throughout the research lifecycle. To make this process actionable, the framework uses a five-point scale based on probability and impact, adapted from U.S. intelligence community standards. This scoring system feeds into a five-by-five risk matrix that places research into one of four categories: no risk, some risk, major risk, or critical risk. Each category corresponds to a specific set of recommendations. For example, low-risk projects may proceed without restriction, whereas high-risk projects may be allowed to continue but with limitations on publishing sensitive details such as methods or data. In rare cases, projects that pose extreme risks may be halted entirely.

Governance is central to the success of this approach. Consequently, the working paper establishes clear roles for principal investigators (PIs) and organizational leadership, with an independent review entity to ensure oversight and accountability at each step, and consistency in how judgments are made. This approach relies heavily on self-regulation but recognizes how this type of self-governance can fall short in preserving biosecurity. Drawing on lessons from past biosecurity incidents, ethical debates, and regulatory gaps, the framework aims to fill a critical void in how the scientific community handles research that is both valuable and dangerous.

The working paper also addresses the broader challenge of balancing scientific openness with security concerns. It points to historical examples as evidence that unrestricted publication can be dangerous. Yet it also recognizes that open science is vital to innovation and public trust. Striking this balance requires mitigation actions that are context-sensitive, not one-size-fits-all.

Chapter 1: Background

An information hazard (IH) is a risk that arises from the dissemination or the potential dissemination of true information that may cause harm or enable some agent to cause harm.[1] Because most information could conceivably be used for benevolent or harmful purposes, it is useful to focus on those that are most worrying. As such, we define an information hazard of concern (IHC) as an IH which could be misapplied to do harm with no, or only minor, modification to pose a significant threat with broad potential consequences to public health and safety, agricultural crops and other plants, animals, the environment, materiel, or national security”. Since IHCs are a subset of IHs, only some IHs are IHCs. Note that the IHC definition is synonymous with the definition of dual use research of concern (DURC) as stated in the “United States Government Policy for Oversight of Dual Use Research of Concern and Pathogens with Enhanced Pandemic Potential”.[2]

This definition acknowledges the relationship with dual-use research (DUR) and DURC. For example, an information hazard could be a product of DURC, defined as “life sciences research that, based on current understanding, can be reasonably anticipated to provide knowledge, information [emphasis added], products or technologies that could be misapplied to do harm with no, or only minor, modification to pose a significant threat with potential consequences to public health and safety, agricultural crops and other plants, animals, the environment, materiel or national security”.[3]

These assessments focus primarily on research outcomes or actions that may result in knowledge or information products that could pose a hazard, i.e. IH and IHC, a category of hazards that are more subtle than direct physical threats and hence unduly neglected.[4] Harm can arise from the discovery and dissemination of true biosecurity research results because of the dual use nature of this type of research. RAND research tackles problems typically beyond the more prescribed scope of existing National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB) and U.S. government frameworks and policies.[5] Therefore, this project is scoped only for information hazards, as opposed to the full spectrum of work that extends to technologies, products, and equipment as in the DURC definition. Those wishing to develop approaches to identify and mitigate information hazards arising from laboratory research, for example, are therefore unlikely to find the protocol outlined here sufficient but might instead use it as a starting point that can be adapted to their situation.

Collectively, those frameworks are also more tailored to federal Select Agents and work that contributes relatively directly to misuse of such agents or toxins. At RAND, we need to make decisions on a broader set of information hazards beyond Select Agents, requiring a more generalist framework that is suitable for emerging areas of work like AI in biology, mirror life, biotechnology/bioeconomy, and the life sciences. This narrow scope also acknowledges the intrinsic value of information or results generated from biosecurity research as strategic assets. Such asset-centric and value-based perspective allows us to be proactive in securely managing biosecurity research results that could be maliciously misapplied to do harm, leading to greater protections.[6]

Safe, Secure, and Responsible Research

Responsible science, debates about the risks of biological research and disagreements over the natural, accidental, or intentional origins of pandemics mandate scientists address the biosafety and biosecurity concerns of their work directly, so we do not accidentally seed a human-made pandemic or give people ideas of how to do so.[7] Heightened concerns and the evolution of biosafety and biosecurity policy have been informed by a range of historical events, from bio-crimes to controversial experiments and natural biological events.

Following the replication of the first recombinant DNA molecules in Escherichia coli, scientists in 1974 called for a voluntary moratorium on certain experiments, holding a conference (Asilomar) to evaluate the risks (if any) of this new technology.[8] The conference attendees concluded that recombinant DNA research should proceed but under strict guidelines.[9] Controversy arose again in 2011, when scientists in the U.S. and the Netherlands independently genetically engineered mutant H5N1 (avian flu) viruses.[10] More recently, debate was stimulated by the publication in 2024 of research detailing the mutations necessary to switch host receptor recognition for bovine H5N1 from avian to human specificity.[11]

Science and scientists must contend with balancing the question of freedom of inquiry or dissemination of scientific research (open science) when their work is beneficial and worthwhile, with the social responsibility of ensuring risks are responsibly communicated to the public when their work is risky or can be used maliciously.

However, implementing existing guidance such as the 2023 NSABB Biosecurity Oversight Framework has been difficult due to the slow pace and opacity of review processes resulting in few biosecurity research undergoing this process. The NSABB itself acknowledged that the patchwork of prior DURC; U.S. government Potential Pandemic Pathogen Care and Oversight (P3CO); and Pathogens with Pandemic Potential (PPP) policies captured only a small fraction of relevant work, lacks timely investigator-level engagement, and offers limited transparency.[12] The NSABB urged the U.S. government to remedy this by widening the scope of review, harmonizing definitions, and publishing clearer, faster guidance.[13]

Snyder et al. argue that these shortcomings stem partly from the NSABB’s unrealized original remit: the board was intended to act as an on-call technical-assistance body for complex dual-use experiments, yet it has been consulted only rarely and, since the 2012 H5N1 controversy, no longer offers such support.[14] They propose a “just-culture” model in which an independent authority would pair a graduated enforcement continuum with non-punitive incident reporting, routine technical assistance, and proactive outreach—mechanisms designed to speed decisions while maintaining accountability and public trust [15]

Furthermore, this review process only applies to federally funded research. Legislation put forward by the U.S. Senate, the Risky Research Act tries to balance innovation and safety, addresses non-federally funded research, and proposes an expedited review process for high-risk life sciences research during an emergency.[16] Researchers continue to advocate for comprehensive risk-benefit analyses that acknowledge the importance of responsible conduct of high-risk biosecurity research and highlight how identifying factors that drive the review can make the process more efficient and less cumbersome.[17]

Open Publication Practices

Information hazards lie at the intersection of the openness-secrecy axis, where the balance between transparency and the protection of information is crucial. The openness/secrecy axis, discussed by Lewis et al. (2021), underscores the need to consider the risks of unfiltered knowledge dissemination, particularly in fields like biosecurity, where the intentional or accidental misuse of research can lead to severe consequences.[18] Open publication practices, including the widespread dissemination of research findings, facilitate the rapid spread of knowledge, enabling innovation and fostering scientific collaboration. However, when dealing with sensitive information—such as in high-consequence life sciences and national security—the open sharing of data can inadvertently amplify risks, making it accessible to unintended or malicious actors. This tension between openness and secrecy is a central concern when evaluating the potential hazards of public access to sensitive information.

Smith and Sandbrink (2020) also highlight how the increased availability of scientific data, including genetic sequences and research methodologies, could be weaponized, emphasizing the ethical dilemma of sharing information that can aid both constructive and harmful activities.[19]

For example, in 2001, al-Qaeda’s deputy, Ayman al-Zawahiri, initiated an anthrax-weapon program after “studying different Western biomedical books and publications”.[20] Specifically, he replicated methods from peer-reviewed articles from Science, The Journal of Immunology and The New England Journal of Medicine. Guided entirely by this open literature, al-Qaeda assembled a rudimentary biosafety level-3 laboratory and began culturing Bacillus anthracis for large-scale dissemination (which never came to fruition). This illustrates how unrestricted publication of e.g., detailed pathogen-handling protocols can provide malicious actors with a blueprint or motivation for action.

In navigating the openness/secrecy axis, the primary challenge is to strike a balance between promoting the free exchange of ideas and safeguarding against misuse. As noted in Nieuwenweg et al, this balance requires nuanced policy frameworks that address not only the benefits of openness but also the potential risks, especially in fields where the implications of information dissemination extend beyond the academic community.[21] Policymakers, researchers, and research managers must weigh the societal and security risks of unrestricted access to sensitive research against the need to promote transparency and collaboration in scientific advancement.

Opportunities and Gaps in Current Dialogue

Although existing literature acknowledges the challenges posed by information hazards, it stops short of prescribing a solution that researchers, funders, and policymakers can adopt to determine when and how to appropriately and safely disclose potentially hazardous biosecurity information. Here, we present a tiered, stepwise approach for reviewing biosecurity information disclosure risks from research, a simple, transparent, actionable, improvable, and repeatable (STAIR) process in a two-part framework. The tiered screening system uses a standard set of risk-benefit questions that enables most research proposals to pass quickly while directing a small subset of high-concern ones to more intensive review. This is followed by an assessment outcome determination process that leverages nominal risk scores that feed into a 5x5 risk matrix, allowing projects to be classified by risk groups. This clear workflow dovetails with the NSABB requirement for a review mechanism without undue delays, giving users (e.g. researchers, funders, and policymakers) a consistent disclosure process that protects both public safety and scientific progress.

Project Goal and Objectives

The project goal was to provide a structured way to balance the benefits and risks from the release of biosecurity research results that pose an information hazard. The objective was to develop an actionable set of guidelines that biosecurity researchers and people who fund their work could use to manage benefits of the release of information and the biosecurity information hazard risks that could result from that release.

The remainder of this working paper is organized as follows. Chapter 2 describes the question development process and conceptual models for this framework, administrative process for the proposed approach for balancing the benefits and risks from the release of biosecurity research results, as well as the technical approach, the key basic concepts that we relied on. Chapter 3 presents a high-level summary of the new framework and living guide, including a description of the Part I and Part II forms that make up the framework. Chapter 4 introduces the nominal risk scoring approach and describes the risk group approach as one component of the comprehensive risk-benefit analysis that determines assessment outcomes. Chapter 5 is a discussion of roles and responsibilities of key players in this process and a “Code of Practice”. The rest of the working paper are appendices,

Appendix A-D that include blank assessment and risk scoring forms, and instructions for completing them.

Chapter 2: Guidance for Responsible Communication of Research (RCR)

Under “Administrative Process”, we provide visual flowcharts with an overview of the proposed workflow. In “Technical Approach”, we describe a 2-tier initial and a final information hazard assessment framework.

Deploying our technical approach using the described administrative process requires true team effort and correctly done, should result in one of several recommendations, including whether to pause, proceed, or proceed cautiously with biosecurity research or disclosing resulting information products. The biosecurity research of interest is assigned one of three information disclosure risk categories: no biosecurity information disclosure risks, some biosecurity information disclosure risks, and major biosecurity information disclosure risks. Alongside review of the research proposal and completed risk assessments submitted by PIs and study teams, organizational leadership and an independent review entity (IRE)–discussed in Chapter 5–can conduct a comprehensive risk-benefit analysis and provide useful recommendations to PIs and study teams to guide the conduct of their biosecurity research and release of their results.

Questionnaire Development Process

Our questionnaire development process relied on desk research and consultations with RAND experts. Working with a knowledge services librarian, we identified keywords and phrases using exemplar articles and sentinel citations that must be retrieved and developed inclusion and exclusion criteria for a literature review that addressed our research questions (

Table 1). The parameters were publication language in English, and publication types that included peer-reviewed literature, grey literature, and government, NGO, non-profit and thinktank publications. Databases searched were PubMed and Web of Science, resulting in 438 peer-reviewed publications and 104 grey literature results. This was followed by a title/abstract screen by the study team to retain only relevant publications, and extensive consultations with senior RAND experts that helped with our question development process. We also developed scenarios to test and refine the questions in a tabletop exercise and conducted dry runs with existing and ongoing RAND projects.

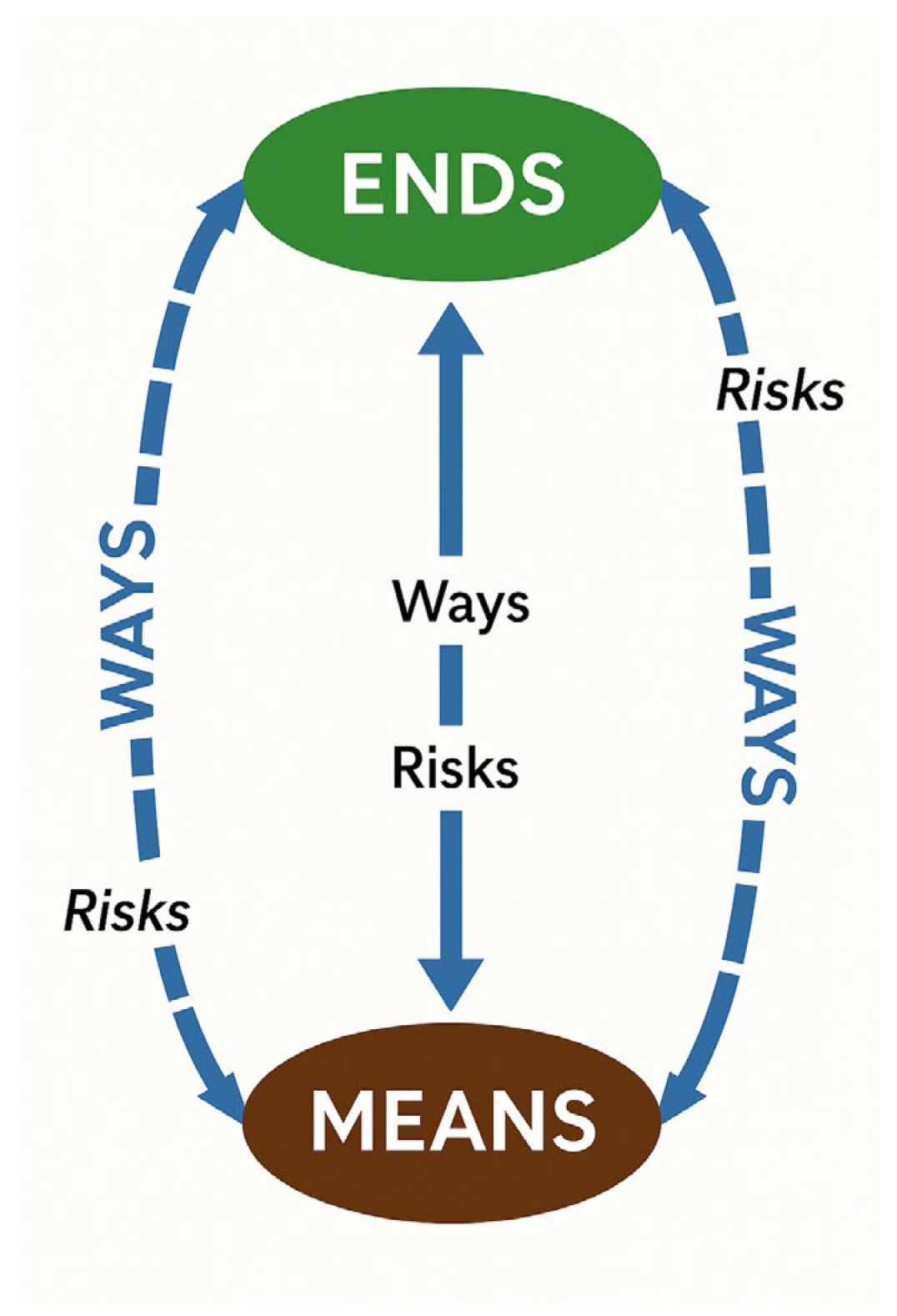

Conceptual Model for this Project

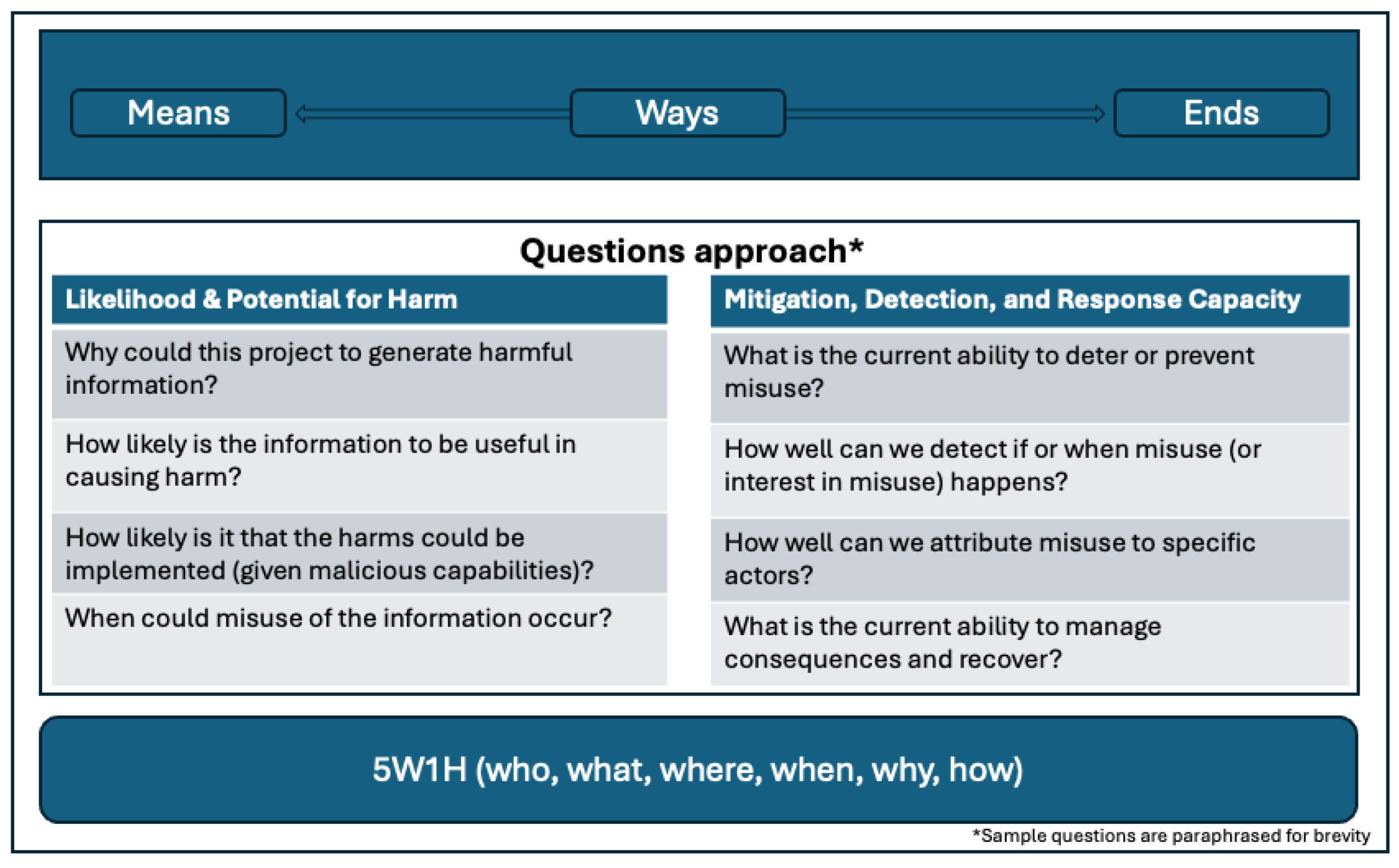

Two frameworks were used as conceptual models to guide the development of the key questions that make up this Biosecurity Research Oversight Framework. The first is the 5W1H (who, what, where, when, why, how) or Kipling method, a questioning and problem-solving approach used to comprehend details and analyze inferences to get to fundamental facts about an issue that could contribute to the resolution of a problem.[22] Here we used the Kipling method to ensure that we thought comprehensively about all aspects of both the IHC and the risks posed by its disclosure.

The second conceptual model is Lykke’s Strategic Framework, that focuses on strategic decision-making, scenario planning, and risk assessment. Lykke’s framework is built around three key pillars that we adapt for our purposes: Ends, Ways, and Means. “Ends” refer to an outcome, which, in this case, is an IHC (see

Figure 1). “Ways” represents the courses of action that can result in that outcome, while “Means” refers to the resources required to implement those actions.

This conceptual framing provided a structured approach for exploring the trade-offs involved in managing biosecurity information disclosure decisions, affording us the opportunity to think concisely and completely about the questions we should be asking.

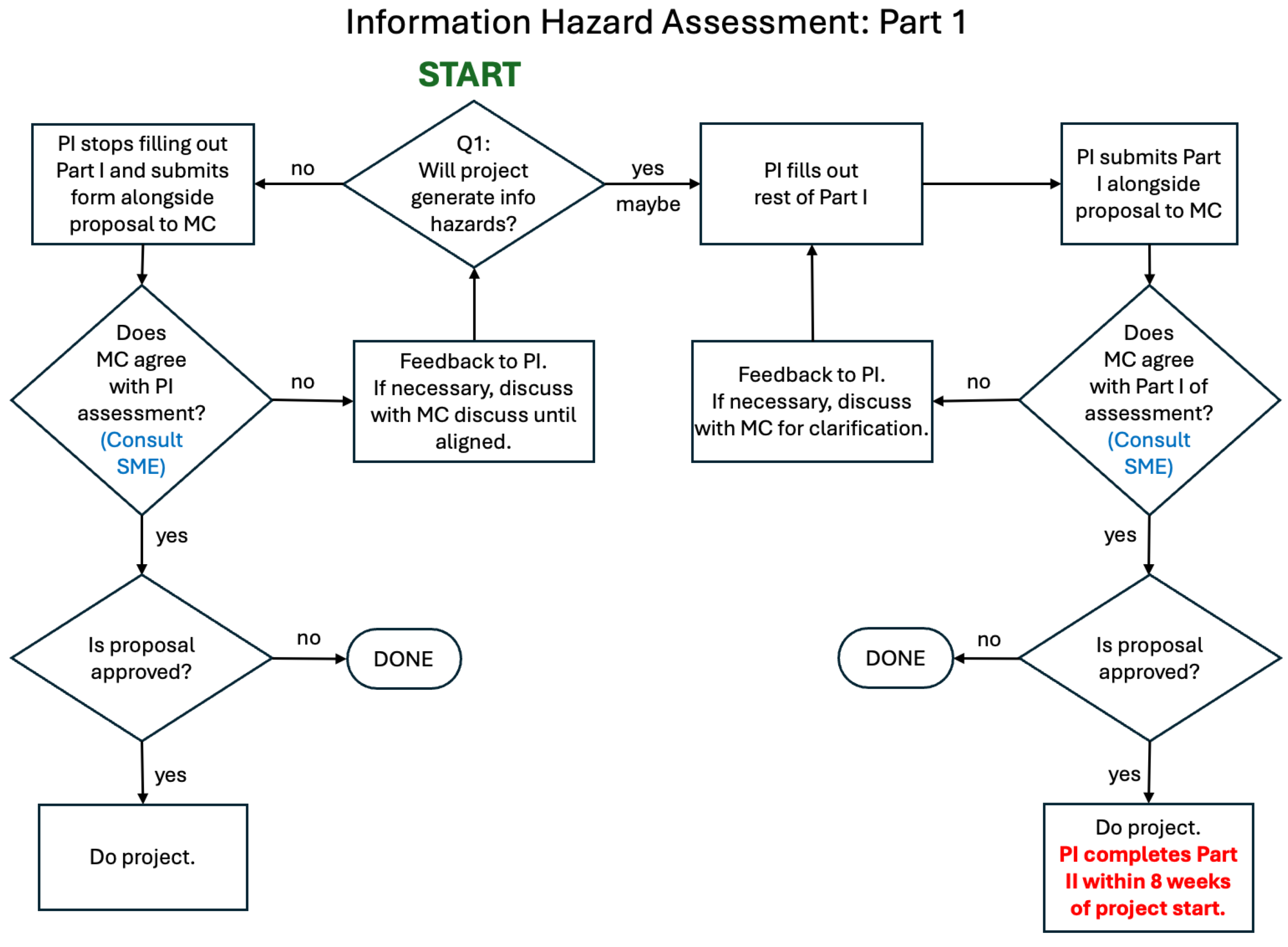

Administrative Process

In the proposed framework, organizational leadership should require all biosecurity research projects to undergo risk analysis and evaluation focused on risks related to the disclosure of information hazards using the administrative process depicted in the flowcharts below. Details of the technical approach are described in the sub-section after this.

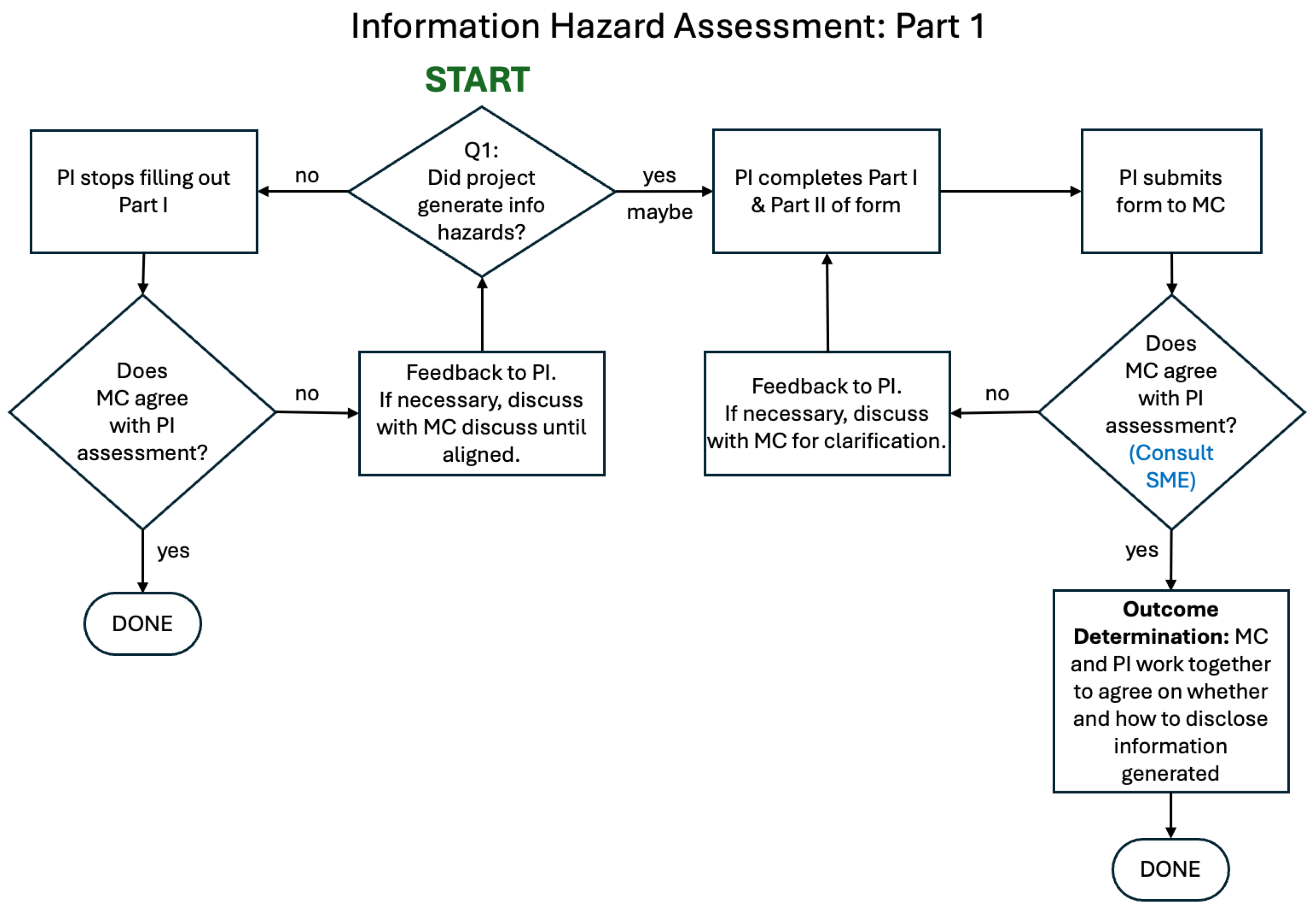

To summarize, PIs and study teams complete an

initial information hazard assessment (

Figure 2) in two parts. Part I is

pre-submission and

pre-approval while the proposal is being developed. Part II is completed while the project is in progress – within 8 weeks of the project’s start, but no later than the project midpoint. As a

final information hazard assessment (

Figure 3), PIs and study teams are asked to repeat the assessment (Parts I and II) at the end of the project, with responses reviewed for concordance with the initial assessment.

We propose a process wherein, prior to submitting a proposal, PIs and study teams determine whether information hazards are likely to be generated, providing narrative descriptions that kick off the initial information hazard assessment. The PI submits responses to the Part I form alongside the draft proposal to organizational leadership for review. If the PI responds “no” to Question 1.1 in the Part I form, responses to Questions 1.2 to 1.4 are not required. The Part I form is designed to move projects without an information hazard risk very quickly through the process without the need to collect extraneous information. Organizational leadership, alongside the IRE if deemed necessary to assemble at this stage reviews the narrative responses and, if necessary, works with the PI to agree on the nature of the information hazards, if they are of concern, and mitigation actions to minimize their risk.

If the proposal is not approved, the Part II form should NOT be completed. If the proposal is approved and funded, the project proceeds, as does completing the Part II form under specified conditions – within 8 weeks of the project’s start but no later than the project’s midpoint. If an IHC is identified in the Part I form, PIs and study teams may STOP work on the project on the recommendation of organizational leadership and the IRE even if the project would be otherwise approved and funded.

For ALL approved projects, PIs and study teams will complete the Part II of the information hazard assessment, providing narrative responses for Questions 2.1 to 2.16 to organizational leadership, within 8 weeks of the projects start but no later than the project midpoint. This time lag accounts for cases where the nature of the information hazard is difficult to determine until the project is well underway but also recognizes that some projects are quick-turn and of short duration. For the Part II form, detailed responses are required for Questions 2.1 to 2.10. Less detailed responses are acceptable for Questions 2.11 to 2.16.

At the end of ALL projects, PIs and study teams should submit a final information hazard assessment, repeating the Part I and Part II forms. (Note that if the project did not generate IHs, the PI simply checks “no” to Question 1.1 in the Part I form and Question 2.1 in the Part II form, and organizational leadership signs off, assuming agreement). This final assessment is looking for concordance with responses to the initial assessment, and the capture of unexpected information hazards generated during the project. The PI, organizational leadership and IRE (if assembled) work together on outcome determination and agree on recommendations, whether and how to disclose the information generated.

Timing and Time Commitment

Part I of the form is typically completed in under 30 minutes and is submitted alongside the proposal. If the proposal receives organizational leadership approval, study teams move on to complete Part II, which is typically filled out in an hour and submitted within 8 weeks of the projects start but no later than the project midpoint. Most teams will find that the final information hazard assessment requires considerably less time than the initial information hazard assessment since responses can be copied over.

Technical Approach

The proposed approach comprises an initial information hazard assessment and a final information hazard assessment. The initial information hazard assessment requires completion of Parts I and II of the assessment form. The final information hazard assessment repeats the initial assessment at the end of the project. In developing these assessments, we considered the following as ground truths:

1) A risk assessment is expressed as (risk) analysis plus (risk) evaluation, i.e. Analysis + Evaluation, and

2) Risk includes consideration of both likelihood and consequences, where likelihood further encompasses threats and vulnerabilities.

All responses collected in these assessments are taken into consideration to make an evidence-informed assignment of biosecurity research information into one of four outcome categories, balancing a comprehensive risk-benefit analysis, in turn linking this to a pool of mitigation actions. The analysis collects risk and benefits information, with PIs and study teams telling us about their research by answering probabilistic questions on “likelihood of risk” and narrative-based questions on consequence management. The proposed evaluation approach to link dimensions from the Part II form (likelihood related questions, 2.7 to 2.10; and consequence management related questions, 2.13 to 2.16) to outcomes and recommendations is a 5-step process (see section on “outcome determination using risk groups” in Chapter 4) in some type of objective or quantitative way using likelihood and consequence scores. The evaluation (risk-benefit analysis) takes the scores and narratives provided by the study teams into consideration to determine an outcome and proffer recommendations.

While the assessments primarily focus on research outcomes or actions that could result in knowledge or information products that could pose a hazard i.e. IH and IHC, there are secondary considerations. Other research outcomes and actions may result in knowledge, information, technologies, products, equipment or materials that also warrant careful assessment for DUR or as potential DURC, because of the overlap that exists with IH and IHC. The secondary considerations include research outcomes that we also used as a guide for development of the assessment questions. These outcomes are defined by NSABB[23] and U.S. government policies on DURC, P3CO, and PPP[24] that expands current and erstwhile narrow definitions of research categories as follows:

From NSABB, the seven (7) categories of experiments:

a. Enhance the harmful consequences of the agent or toxin;

b. Disrupt immunity or the effectiveness of an immunization against the agent or toxin without clinical or agricultural justification;

c. Confer to the agent or toxin resistance to clinically or agriculturally useful prophylactic or therapeutic interventions against that agent or toxin or facilitates their ability to evade detection methodologies;

d. Increase the stability, transmissibility, or the ability to disseminate the agent or toxin;

e. Alter the host range or tropism of the agent or toxin;

f. Enhance the susceptibility of a host population to the agent or toxin; or

g. Generate or reconstitute an eradicated or extinct agent or toxin listed in the policy.

From U.S. government DURC, P3CO and PPP policies, Categories 1 and 2 research:

h. Category 1 research meets three criteria: (1) It involves one or more of the biological agents and toxins specified by the Federal Select Agents and Program; (2) It is reasonably anticipated to result, or does result, in one of the experimental outcomes listed in the NSABB seven categories of experiments above; and (3) Based on current understanding, the research constitutes DURC;

i. Category II research meets three criteria: (1) It involves, or is reasonably anticipated to result in a PPP[25]; (2) It is reasonably anticipated to result in, or does result in, one or more of the experimental outcomes listed below[26]; and (3) Based on current understanding, the research is reasonably anticipated to result in the development, use, or transfer of a PEPP[27] or an eradicated or extinct PPP that may pose a significant threat to public health, the capacity of health systems to function, or national security.

Chapter 3: A New Framework and Living Guide for RCR

The primary objective of the risk assessment is to evaluate whether a proposed project will generate information hazards of sufficient concern and to identify strategies for mitigating the risks associated with these hazards. The Biosecurity Research Oversight Framework is made up of a Part I and II form with 10 and 16 questions respectively, for a total of 26 questions, in addition to a risk scoring matrix to aid outcome determination. A representative cross-section of the assessment questions (edited for brevity) linked to the conceptual models used for question development is illustrated below:.

Figure 4.

Representative Cross-section of Assessment Questions.

Figure 4.

Representative Cross-section of Assessment Questions.

To ensure comprehensive oversight, two assessments, that entail completion of the Parts I and II forms twice, are conducted during the project life cycle:

The initial information hazard assessment: PIs and study teams complete the Parts I and II (if necessary) forms. The Part I form is completed during proposal development and conceptualization i.e. pre-submission and pre-approval, to facilitate responsible handling of projects that could generate an IHC from the outset. The Part II form is completed after the project is approved and kicks off, occurring within 8 weeks of the project’s start but no later than the project midpoint, while project work is actively conducted, allowing for real-time evaluation of emerging risks.

The final information hazard assessment: This is a repeat assessment. PIs and study teams complete the Parts I and II forms, updating their answers to their prior responses in the initial information hazard assessment. This should occur on the project's completion, before QA and prior to the publication of its findings, ensuring that any residual risks are addressed before dissemination.

Chapter 4: Assessment Outcome Determination

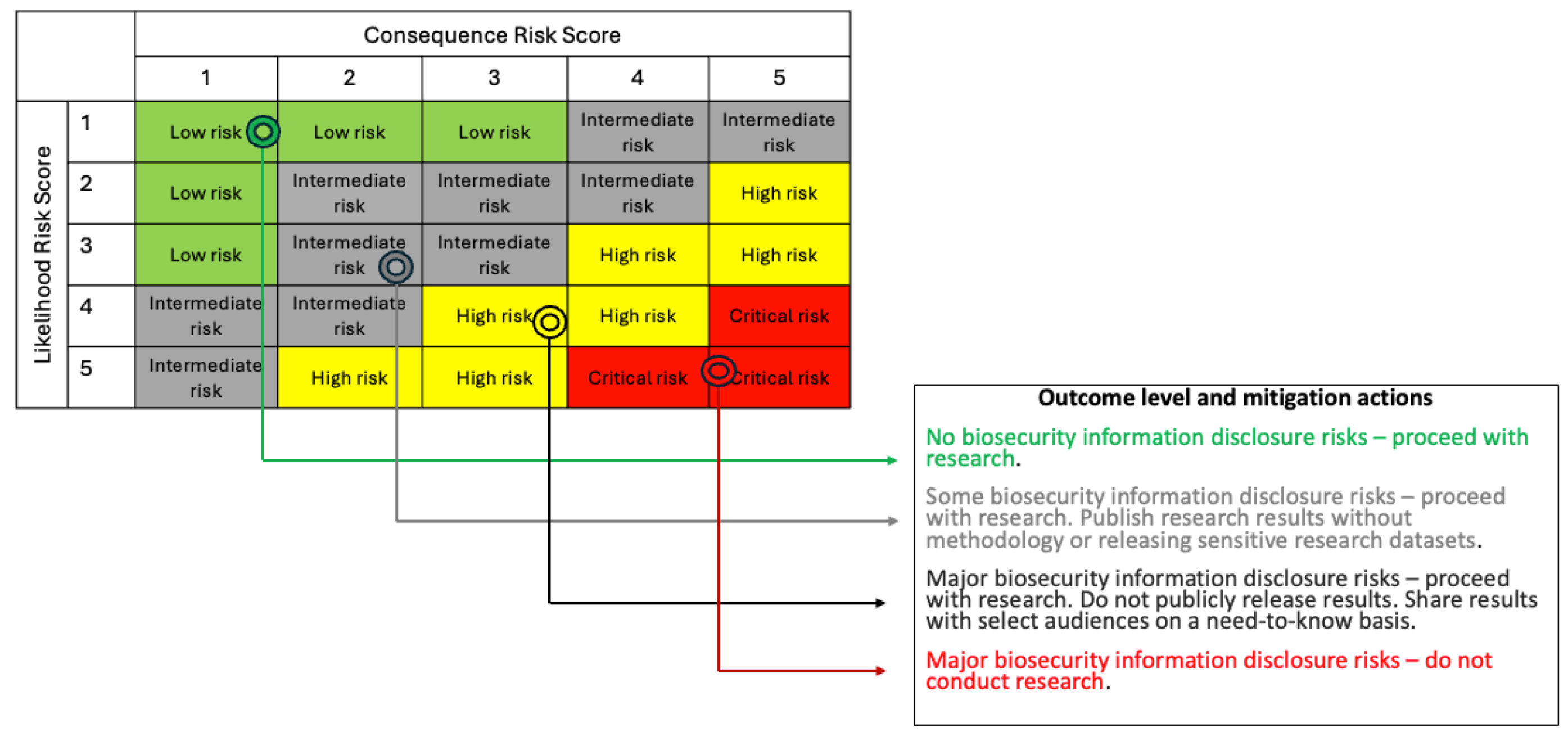

This assessment uses answers from the Part II form to balance the beneficial attributes of the proposed project and the information generated against their potential to cause harm. Organizational leadership reviews the project proposal and all assessments completed by PIs to conduct a comprehensive risk-benefit analysis using the data points (narratives and risk scores) provided by PIs, convening the IRE if necessary. This is followed by an outcome determination, tied to recommendations on how to proceed with the research and/or publication. This phase is concerned with using PI-provided data points to inform assignment into one of four escalating outcome levels (decisions) for disclosing biosecurity research information as shown in

Figure 5.

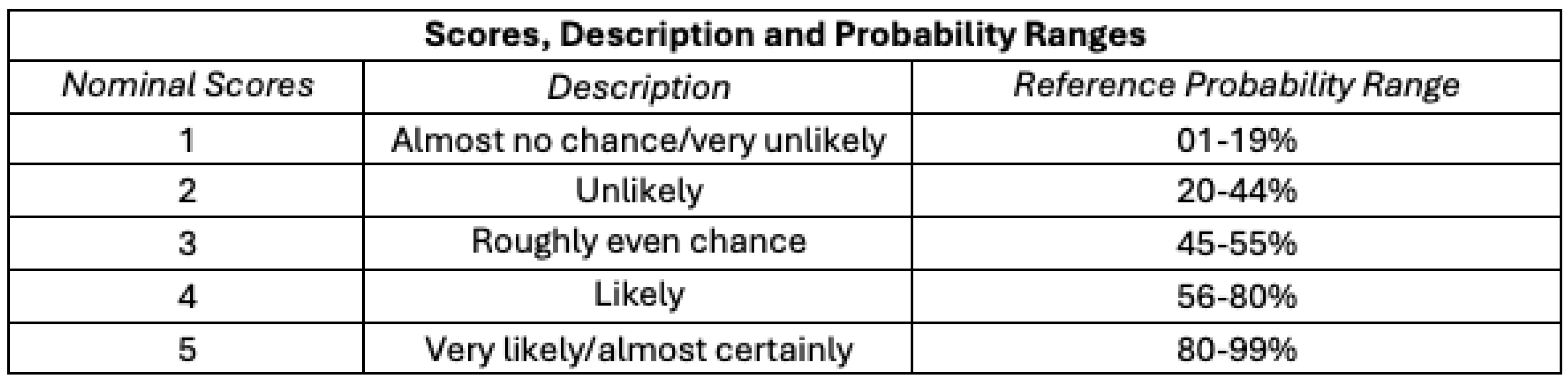

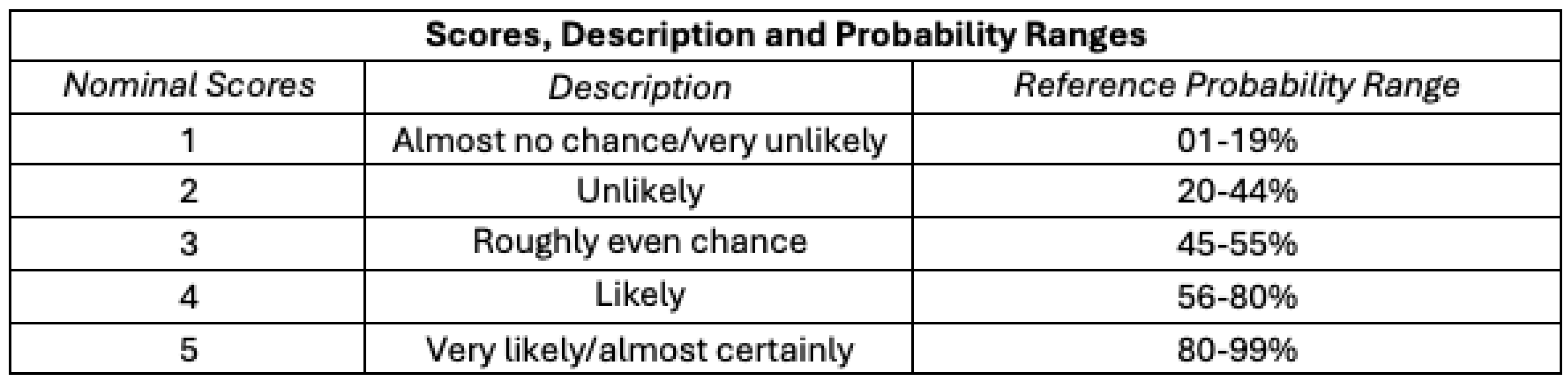

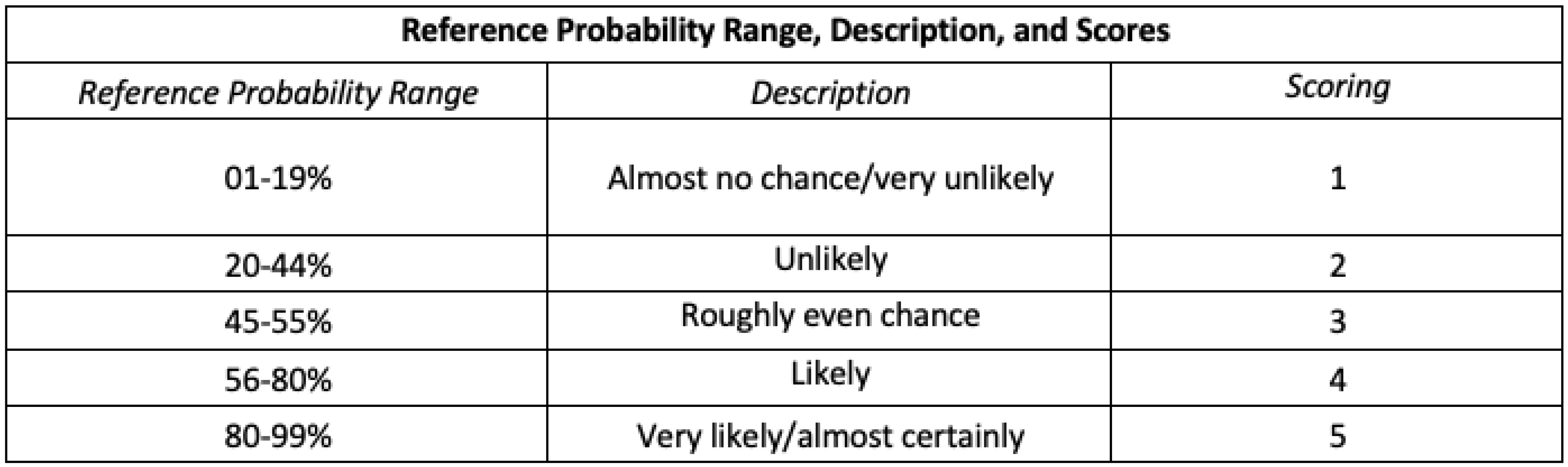

Likelihood Scores

Nominal likelihood scores from 1 to 5 (“almost no chance” to “almost certainly”), descriptions, and reference probability ranges are shown in

Table 2, drawing on the Analytics Standards in Intelligence Community Directive 203 (ICD 203).[28] ICD 203 is an Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) directive that establishes standards for the Intelligence Community (IC) that govern the production and evaluation of analytics products, providing a set of terms for the IC to express likelihood or probability for analytic products. We concatenate the ICD 203’s seven reference ranges into five by collapsing the first two and last two ranges.

Table 3.

Likelihood Scores Derivation from Concatenated ICD 203 Reference Ranges.

Table 3.

Likelihood Scores Derivation from Concatenated ICD 203 Reference Ranges.

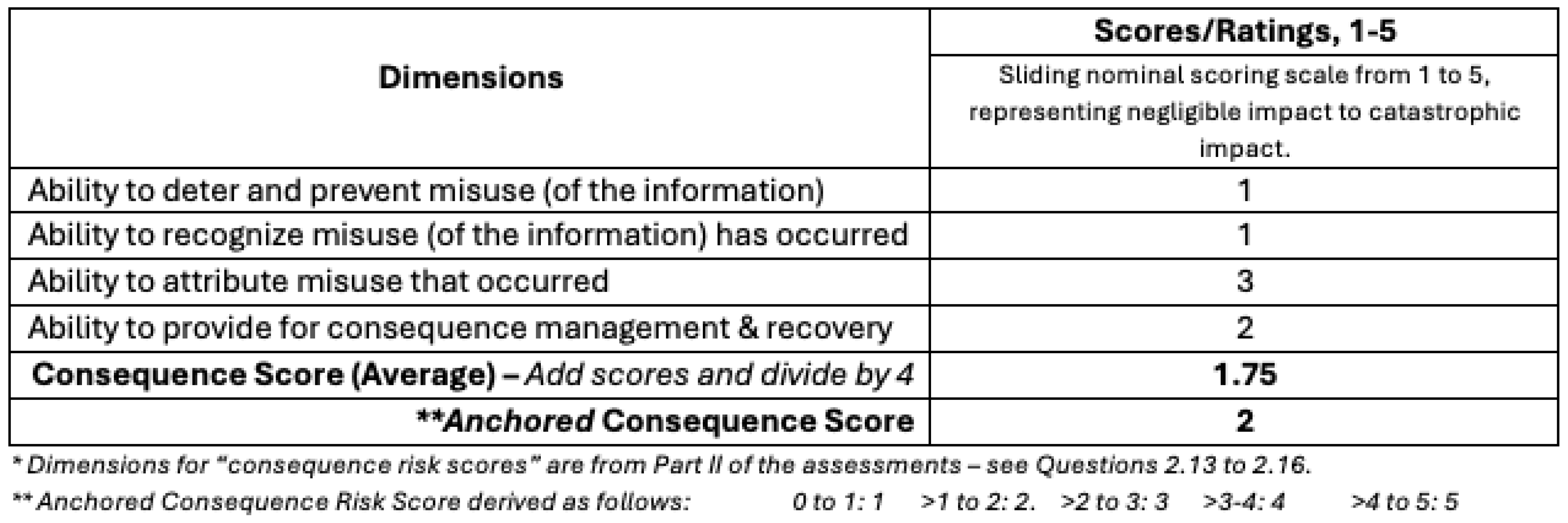

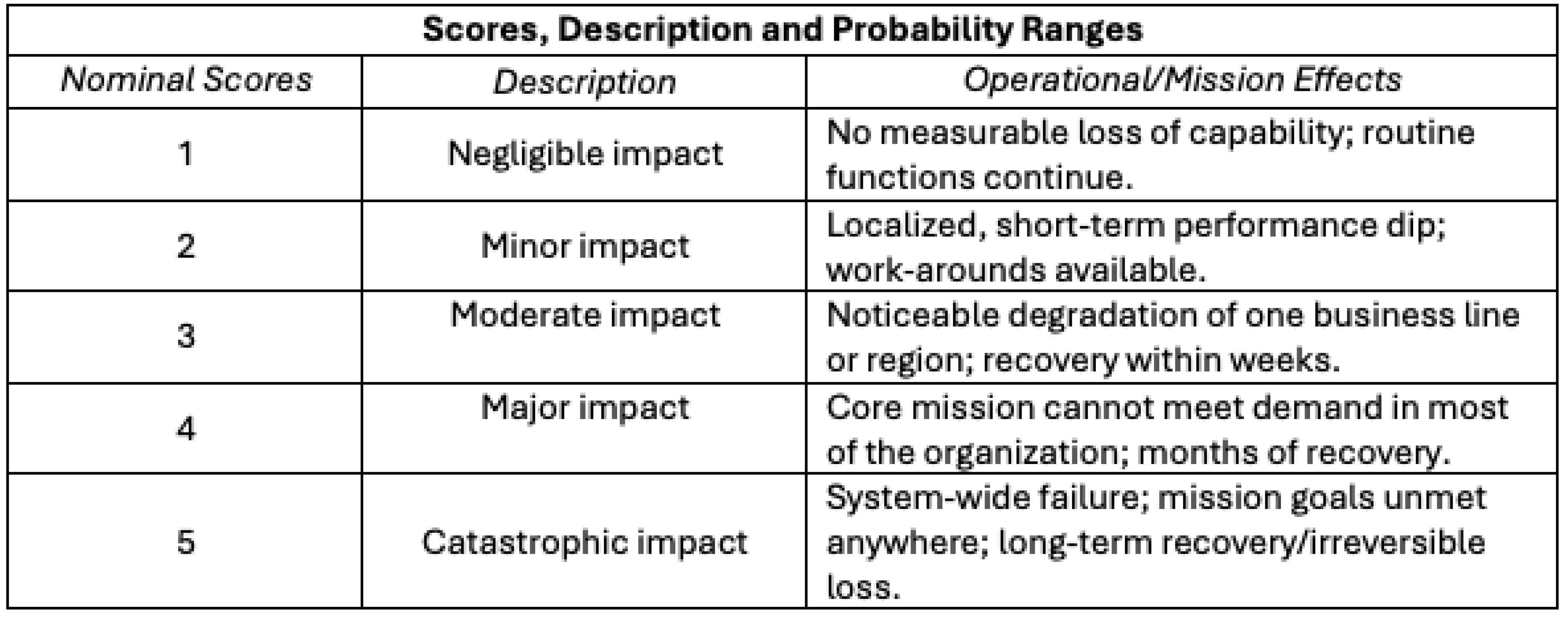

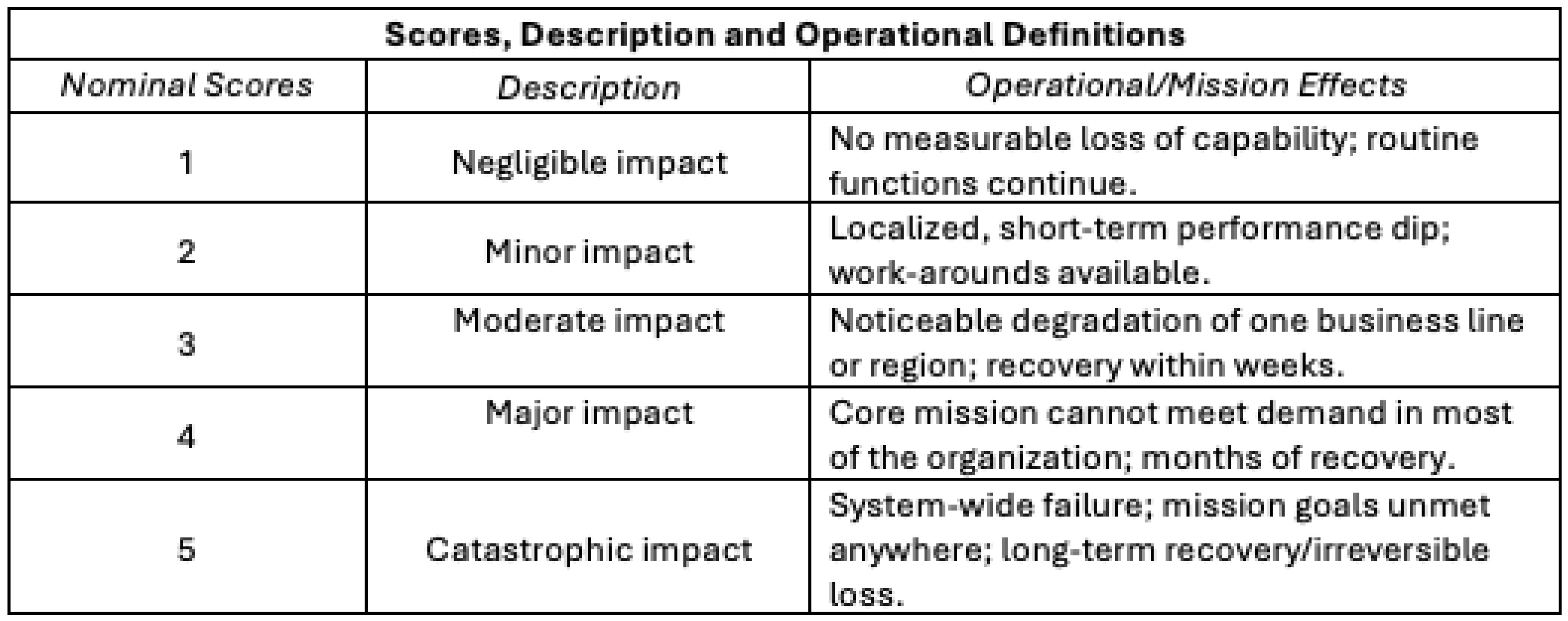

Consequence (Impact) Scores

Nominal consequence (impact) scores from 1 to 5 (“negligible impact” to “catastrophic impact”), descriptions, and operational effects are shown in

Table 4.

Outcome Determination using Risk Groups

Our approach to link dimensions from the Part II form (likelihood related questions, 2.7 to 2.10; and consequence management related questions, 2.13 to 2.16) to outcomes and recommendations relies on risk groups.[29] Risk groups are classifications that describe the relative hazard posed by misuse or release of hazardous information and are based on likelihood and consequence risk scores. Risk groups are identified using the 5-step process below, giving an outcome level and recommendation for consideration by organizational leadership.

Step 1: Nominal risk scoring from 1 to 5 (“almost no chance” to “almost certainly” for likelihood scores, and “negligible impact” to “catastrophic impact” for consequence scores) using blank forms provided in

Appendix B and following the instructions in

Appendix D.

Step 2: Calculate likelihood and consequence scores (average) using blank forms provided in

Appendix B and following the instructions in

Appendix D.

Step 3: Derive “anchored” likelihood and consequence scores using blank forms provided in

Appendix B and following the instructions in

Appendix D.

Step 4: Match anchored scores to appropriate risk group using the 5x5 risk matrix,

Figure 5.

Step 5: Match risk group to outcome level and mitigation action,

Figure 5.

The risk group to which an IH is assigned is the primary, but not only, consideration used in a comprehensive risk-benefit analysis to determine the appropriate outcome level and mitigation actions. Organizational leadership, alongside members of the IRE as necessary review the project proposal and narratives provided by PIs and study teams (initial and final assessment results). Based on the assessment outcome determination in the following 5x5 matrix, and in conjunction with the PI, a suite of risk-mitigation actions (

Figure 5 and

Table 6) is developed and approved by organizational leadership.

For example, a hypothetical biosecurity research study with an anchored likelihood score of 3 (

Table 5) and an anchored consequence score of 2 (

Table 6), will be in the “intermediate risk” group (

Figure 5). The outcome level here corresponds to “some biosecurity information disclosure risks” with a recommendation to proceed with the research, but to publish research results without the methodology or releasing sensitive research datasets.

Risk matrices like this one have inherent limitations as discrete approximations of expected value of consequences, as discussed by Cox (2008), which itself is an approximation for subjective risk aversion.[30] Accordingly, the risk matrix should be treated as just one view of a study's risk. These limitations are strongest for small probabilities, where differences between small likelihoods binned together (0.01% vs 1%) can easily make orders-of-magnitude differences in expected consequences. This means that the upper right corner of

Figure 5, representing quite unlikely but severe events, threats of little concern can be lumped into the intermediate risk group. Accordingly, we recommend applying especially careful judgment to this upper right corner, which may involve more direct expected value calculations and comparing with other unlikely but grave events.

Table 5.

Likelihood Scores Example.

Table 5.

Likelihood Scores Example.

Table 6.

Consequence Scores Example.

Table 6.

Consequence Scores Example.

Assessment Outcomes

The assessment outcomes are shown in

Table 7, by risk group.

Mitigation Actions

The mitigation actions here, linked to assessment outcomes, are only a starting guide to a suite of actions that can be more extensive than what we have listed. Organizational leadership and the IRE should lean on a pool of policy options that extends beyond what we have listed in

Table 8. This recognizes the uniqueness of each research proposal, the ever-evolving nature of biosecurity threats (driven by technological innovation and convergence), and the significant variation in the sources of information hazards. Mitigation actions can range from “no action necessary” to a moratorium on biosecurity research. Further consideration may include the need for (and feasibility of) further controls on the information once it is shared on a "need-to-know" basis. It is very difficult to further control information dissemination after it is given to the government for example, even on a “need-to-know” basis, as articulated by one member of our expert panel.

Chapter 5: A Word on Roles and Responsibilities

The successful implementation of this framework depends on clearly defined responsibilities and coordination between PIs and organizational leadership. PIs are responsible for identifying and assessing potential information hazards generated by their research, while organizational leadership oversees and adjudicates those assessments, guiding decisions on whether and how research can proceed or be shared. In complex or high-risk cases, organizational leadership may convene an IRE of relevant experts to provide additional input, but all decisions remain internal to the Center. This collaborative structure supports consistent, transparent, and adaptive management of biosecurity risks.

PI and Study Teams

PIs lead the information hazard assessment process. Before submitting a proposal, the PI completes Part I of the Information Hazard Assessment to evaluate whether the proposed project might create or disseminate potentially hazardous information. If the PI determines there is no risk (via Question 1.1), the process ends early.

Otherwise, the PI provides narrative responses outlining the potential nature, severity, and misuse scenarios of any identified information hazard. These responses are submitted with the proposal to organizational leadership for review.

If the project is approved, the PI must then complete Part II of the assessment within eight weeks of project kickoff, expanding on initial concerns with further detail on novelty, accessibility, potential actors, and risk likelihood and consequences. At project closeout, the PI revisits and completes a final assessment, repeating Parts I and II to identify any new or evolved risks and ensure consistency with the initial evaluation. The PI works closely with organizational leadership throughout, including making final decisions on whether and how to disseminate results.

Organizational Leadership

Organizational leadership plays a review and decision-making role throughout the assessment lifecycle. It evaluates the initial Part I submission to determine whether the proposal can move forward and flags projects that require additional review or changes. They can pause or halt projects at any stage if the risks identified are deemed too severe, even if the project is otherwise approved and funded.

During project execution, organizational leadership receives and reviews the PI’s Part II submission and conducts final reviews at project completion. This includes checking for alignment between initial and final assessments, identifying new hazards, convening the IRE (if needed) and jointly determining appropriate publication or dissemination pathways. Organizational leadership ensures that all risk-benefit tradeoffs are transparently considered and that assessments remain actionable and improvable over time.

Independent Review Entity (IRE)

The IRE (designated a Biosecurity Review Board) is a body of experts (internal to the organization in addition to external subject matter experts) convened by organizational leadership to aid their decision making when an IH appears particularly novel, severe, or difficult to adjudicate. Drawing on the completed assessments and organizational leadership input, the IRE helps interpret risk-benefit tradeoffs using structured criteria, including risk scoring matrices. While organizational leadership retains decision-making authority, the IREs role is to provide a cross-functional, expert-informed second opinion that strengthens consistency, transparency, and quality of outcomes.

The IRE may recommend one of several outcomes: full publication, restricted dissemination, modified publication (e.g., redacted methods), or, in rare cases, a recommendation not to proceed with the research or its dissemination. The IRE functions as a governance safeguard — ensuring decisions about high-risk information hazards are deliberate and robust by providing technical advice and value judgments. This type of third-party involvement in decision-making helps maintain transparency and ensure the integrity of the review process.

Opportunities for Oversight

Establishing effective oversight mechanisms is essential to ensuring that the information hazard assessment process remains credible, consistent, and adaptable over time. This framework embeds oversight opportunities at key decision points and encourages institutions to adopt internal governance practices that reinforce responsible communication of biosecurity risks.

Embedded Governance

Oversight is integrated throughout this process, starting with mandatory assessments at proposal, midpoint, and closeout stages. These assessments are reviewed by Organizational leadership and, when necessary, escalated to a designated IRE for additional scrutiny. This structure ensures that projects with higher potential risks receive proportionally greater oversight and that decisions are based on well-documented, repeatable criteria.

Internal Compliance Mechanisms

To promote accountability, the framework recommends that institutions designate a responsible official or committee to monitor compliance with the assessment process and ensure timely submission and review of required forms. Institutions may also wish to maintain internal logs of projects assessed, decisions made, and justifications, which can inform future policy revisions and training.

Transparency and Feedback

While not all disclosure decisions can be made public, the process should be as transparent as possible within security and privacy constraints. Institutions should regularly review and update their internal policies, provide feedback channels for researchers, and consider publishing de-identified case summaries or aggregated statistics on information hazard reviews.

Continuous Improvement

The “living” nature of this framework means that oversight is not static. Lessons from past assessments, new developments in science or policy, and emerging threat vectors should feed back into periodic updates to the forms, guidance, and scoring rubrics. Institutions are encouraged to regularly audit the effectiveness of their oversight practices and to participate in cross-institutional discussions to align standards and share best practices.

Notes

-

-

-

3Ibid

-

-

5There are six previous and one present U.S. government dual-use policies. They are as follows: 1) U.S. Government, USG Policy for Oversight of Life Sciences DURC (Federal DURC Policy), March 29, 2012. As of June 23, 2025: https://aspr.hhs.gov/S3/Documents/us-policy-durc-032812.pdf; 2) U.S. Government, USG Policy for Institutional Oversight of Life Sciences DURC (Institutional DURC Policy), September 24, 2014. As of June 23, 2025: https://osp.od.nih.gov/wp-content/uploads/United_States_Government_Policy_for_Institutional_Oversight_of_Life_Sciences_DURC.pdf; 3) Office of Science and Technology Policy, Recommended Policy Guidance for Departmental Development of Review Mechanisms for Potential Pandemic Pathogen Care and Oversight (P3CO), January 9, 2017. As of June 23, 2025: https://aspr.hhs.gov/S3/Documents/P3CO-FinalGuidanceStatement.pdf; 4) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Framework for Guiding Funding Decisions about Proposed Research Involving Enhanced Potential Pandemic Pathogens (HHS P3CO Framework), December 2017. As of June 23, 2025: https://aspr.hhs.gov/S3/Documents/P3CO.pdf; 5) U.S. Government, USG Policy for Oversight of DURC and Pathogens with Enhanced Pandemic Potential (DURC-PEPP Policy), May 6, 2024. As of June 23, 2025: https://aspr.hhs.gov/S3/Documents/USG-Policy-for-Oversight-of-DURC-and-PEPP-May2024-508.pdf; 6) U.S. Government, Implementation Guidance / Implementation Plan for the DURC-PEPP Policy, May 6, 2025. As of June 23, 2024: https://aspr.hhs.gov/S3/Documents/USG-DURC-PEPP-Implementation-Guidance-May2024-508.pdf. 7) White House, Executive Order on Improving the Safety of Biological Research, May 5, 2025. As of June 23, 2025: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/05/improving-the-safety-and-security-of-biological-research/

-

6International Society for Biocuration, "Biocuration: Distilling Data into Knowledge," PLOS Biology, published April 16, 2018. As of June 23, 2025: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2002846 ; Higson, Chris, and Dave Waltho, Valuing Information as an Asset, SAS, January 2011. As of June 23, 2025: https://lenand.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/infoasasset.pdf

-

7Perkins, Dana, Kathleen Danskin, and A. Elise Rowe, "Fostering an International Culture of Biosafety, Biosecurity, and Responsible Conduct in the Life Sciences," Science & Diplomacy, September 29, 2017. As of June 23, 2025: https://www.sciencediplomacy.org/article/2017/fostering-international-culture-biosafety-biosecurity-and-responsible-conduct-in-life ; Perkins, Dana, Kathleen Danskin, A. Elise Rowe, and Alicia A. Livinski, "The Culture of Biosafety, Biosecurity, and Responsible Conduct in the Life Sciences: A Comprehensive Literature Review," Science Communication, published online March 1, 2019. As of June 23, 2025: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1535676018778538 ; Watson, Matthew C., Kunal J. Rambhia, Meghan J. Seltzer, Sarah R. Carter, Rebecca L. Moritz, Aurelia Attal-Juncqua, James Diggans, and John Dileo, "Toward a Safer and More Secure US Bioeconomy," Nature Biotechnology, Vol. 43, December 16, 2024, pp. 23–25. As of June 23, 2025: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-024-02519-2

-

8Meselson, M., and F. W. Stahl, "The Replication of DNA in Escherichia coli," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 44, No. 7, July 15, 1958, pp. 671–682. As of June 23, 2025: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC528642/ ; Berg, P., D. Baltimore, H. W. Boyer, S. N. Cohen, R. W. Davis, D. S. Hogness, and N. D. Zinder, "Potential Biohazards of Recombinant DNA Molecules," Science, Vol. 185, No. 4148, July 26, 1974, p. 303. As of June 23, 2025: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4600381/ ; Barinaga, M., "Asilomar Revisited: Lessons for Today?" Science, Vol. 287, No. 5458, March 3, 2000, pp. 1584–1585. As of June 23, 2025: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10766605/ ; Hurlbut, J. B., "Taking Responsibility: Asilomar and Its Legacy," Science, Vol. 387, No. 6733, January 30, 2025, pp. 468–472. As of June 23, 2025: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adv3132

-

9Barinaga et al, 2000 ; Hurlbut et al, 2025 ; Palmer, M. J., Francis Fukuyama, and D. A. Relman, "A More Systematic Approach to Biological Risk," Science, Vol. 350, No. 6267, December 18, 2015, pp. 1471–1473. As of June 23, 2025: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26680180/

-

10Butler, D., and H. Ledford, "US Biosecurity Board Revises Stance on Mutant-Flu Studies," Nature, March 30, 2012. As of June 23, 2025: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2012.10369 ; Keim, Paul S., "The NSABB Recommendations: Rationale, Impact, and Implications," mBio, Vol. 3, No. 1, January 31, 2012. As of June 23, 2025: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22294677/ ; Palmer et al, 2015.

-

11Lin, Ting-Hui, Xueyong Zhu, Shengyang Wang, Ding Zhang, Ryan McBride, Wenli Yu, Simeon Babarinde, James C. Paulson, and Ian A. Wilson, "A Single Mutation in Bovine Influenza H5N1 Hemagglutinin Switches Specificity to Human Receptors," Science, Vol. 386, No. 6726, December 6, 2024, pp. 1128–1134. As of June 23, 2025: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adt0180

-

12U.S. Government, 2012; U.S. Government, 2014; Office of Science and Technology Policy, 2017; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017; U.S. Government, 2024a; U.S. Government, 2024b; Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, 2024; White House, 2025.

-

13National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity, 2023.

-

14Snyder, Ben C., Joshua M. Wentzel, Gerald L. Epstein, Robert P. Kadlec, and Gerald W. Parker, "Trust, but Verify: A 'Just Culture' Model for Oversight of Potentially High-Risk Life Sciences Research," Applied Biosafety, published online June 5, 2025. As of June 23, 2025: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/apb.2024.0053

-

15Snyder et al, 2025.

-

16Gillum, David, Rebecca Moritz, and Gregory D. Koblentz, "The ‘Risky Research Review Act’ Would Do More Harm Than Good," STAT, July 19, 2024. As of June 23, 2025: https://www.statnews.com/2024/07/19/risky-research-review-act-more-harm-than-good/ ; Koblentz, Gregory D., David Gillum, and Rebecca Moritz, "A Risky Review of Research," Pandora Report, October 21, 2024. As of June 23, 2025: https://pandorareport.org/2024/10/21/a-risky-review-of-research/ ; U.S. Senate. Risky Research Review Act, S. 4667, Amendment ALL24856, 118th Congress, 2nd Session, June 12, 2024. As of June 23, 2025: https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/wp-content/uploads/ALL24856.pdf

-

17Ligtermoet, E., C. Munera-Roldan, C. Robinson, Z. Sushil, and P. Leith, "Preparing for Knowledge Co-Production: A Diagnostic Approach to Foster Reflexivity for Interdisciplinary Research Teams," Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, Vol. 12, Article No. 257, February 25, 2025. As of June 23, 2025: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-024-04196-7 ; Witinok-Huber, Rebecca, Corrine N. Knapp, Jewell Lund, Weston Eaton, Brent E. Ewers, Anderson R. de Figueiredo, Bart Geerts, Clare I. Gunshenan, Martha C. Inouye, Mary L. Keller, Nichole M. Lumadue, Caitlin M. Ryan, Bryan N. Shuman, Tarissa Spoonhunter, and David G. Williams, "Does Knowledge Co-Production Influence Adaptive Capacity?: A Framework for Evaluation," Environmental Science & Policy, Vol. 164, February 2025, 104008. As of June 23, 2025: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1462901125000243

-

18Lewis, Gregory, Piers Millett, Anders Sandberg, Andrew Snyder-Beattie, and Gigi Gronvall, "Information Hazards in Biotechnology," Risk Analysis, first published November 12, 2018. As of June 23, 2025: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/risa.13235

-

-

20Cullison, Alan, "Inside Al-Qaeda’s Hard Drive: Budget Squabbles, Baby Pictures, Office Rivalries—and the Path to 9/11," The Atlantic, September 2004 issue. As of June 23, 2025: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2004/09/inside-al-qaeda-s-hard-drive/303428/; Pita, René, and Rohan Gunaratna, "Revisiting Al-Qa`ida’s Anthrax Program," CTC Sentinel, Volume 2, Issue 5, May 2009. As of June 23, 2025: https://ctc.westpoint.edu/revisiting-al-qaidas-anthrax-program/

-

21Nieuwenweg, Anna Cornelia, Benjamin D. Trump, Katarzyna Klasa, Diederik A. Bleijs, and Kenneth A. Oye, “Emerging Biotechnology and Information Hazards,” conference paper, first online September 8, 2021. As of June 23, 2025: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-024-2086-9_9

-

-

-

24U.S. Government, 2012; U.S. Government, 2014; Office of Science and Technology Policy, 2017; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017; U.S. Government, 2024a; U.S. Government, 2024b; Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, 2024; White House, 2025.

-

25A “pathogen with pandemic potential (PPP)” is a pathogen that is likely capable of wide and uncontrollable spread in a human population and would likely cause moderate to severe disease and/or mortality in humans.

-

26Category 2 experimental research outcomes or actions includes those reasonably anticipated to: I. Enhance transmissibility of the pathogen in humans; II. Enhance the virulence of the pathogen in humans; III. Enhance the immune evasion of the pathogen in humans such as by modifying the pathogen to disrupt the effectiveness of pre-existing immunity via immunization or natural infection; or IV. Generate, use, reconstitute, or transfer an eradicated or extinct PPP, or a previously identified PEPP.

-

27A “Pathogen with enhanced pandemic potential (PEPP)” is a type of PPP resulting from experiments that enhance a pathogen’s transmissibility or virulence, or disrupt the effectiveness of pre-existing immunity, regardless of its progenitor agent, such that it may pose a significant threat to public health, the capacity of health systems to function, or national security.

-

-

-

Funding

Our work was independently initiated and conducted within the Meselson Center using gifts for research at RAND's discretion from philanthropic supporter Open Philanthropy, as well as gifts from other RAND supporters and income from operations. RAND donors and grantors have no influence over research findings or recommendations.

Acknowledgments

We thank workshop participants Bianca Espinosa, Daniel Gerstein, John Parachini, Gerald Epstein, and Rebecca Moritz for their expert insight, and their constructive comments and feedback during working paper preparation, Steph Guerra during peer review, as well as RAND research librarians Emily Lawson and Kiera Addair for their support with the literature review.

Abbreviations

| DUR |

Dual-Use Research |

| DURC |

Dual-Use Research of Concern |

| IC |

Intelligence Community |

| ICD |

Intelligence Community Directive |

| IH |

Information Hazard |

| IHC |

Information Hazard of Concern |

| IRE |

Independent Review Entity |

| ISO |

International Organization for Standardization |

| MC |

Meselson Center |

| NSABB |

National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity |

| OSTP |

Office of Science Technology Policy |

| P3CO |

Potential Pandemic Pathogen Care and Oversight |

| PEPP |

Pathogen with Enhanced Pandemic Potential |

| PI |

Principal Investigator |

| PPP |

Pathogen with Pandemic Potential |

| QA |

Quality Assurance |

| RCR |

Responsible Communication of Research |

Appendix A. Part I and II Forms (Blank Assessment Forms)

See ancillary files for blank assessment forms or contact the authors.

Appendix B. Outcome Determination (Blank Risk Scoring Forms)

See ancillary files for blank assessment forms — risk scoring on pages 20-22. See ancillary files for toolkit (Spreadsheet) or contact the authors.

Appendix C. Instructions for Completing Part I and II Forms

Detailed instructions are provided in Chapter 2 under “Administrative Process”. To summarize, PIs and study teams complete an initial information hazard assessment in two parts. Part I is pre-submission and pre-approval while the proposal is being developed. Part II is completed while the project is in progress – within 8 weeks of the project’s start, but no later than the project midpoint. As a final information hazard assessment, PIs and study teams are asked to repeat the assessment (Parts I and II) at the end of the project, with responses reviewed for concordance with the initial assessment.

The Part I form must be completed and submitted to organizational leadership alongside your proposal, pre-approval i.e. before your project starts. Your answers in Part I should be short and succinct – you will potentially be expanding on them later in Part II.

If the proposal is not approved, the Part II form should NOT be completed. If the proposal is approved and funded, the project proceeds, as does completing the Part II form under specified conditions – within 8 weeks of the project’s start but no later than the project’s midpoint. If an IHC is identified in the Part I form, PIs and study teams may STOP work on the project on the recommendation of organizational leadership and the IRE even if the project would be otherwise approved and funded.

For ALL approved projects, PIs and study teams will complete the Part II of the information hazard assessment, providing narrative responses for Questions 2.1 to 2.16 to organizational leadership, within 8 weeks of the projects start but no later than the project midpoint. This time lag accounts for cases where the nature of the information hazard is difficult to determine until the project is well underway but also recognizes that some projects are quick-turn and of short duration. For the Part II form, detailed responses are required for Questions 2.1 to 2.10. Less detailed responses are acceptable for Questions 2.11 to 2.16.

The Part II form must be completed and submitted to organizational leadership within 8 weeks of the project’s start but no later than the project midpoint.

At the end of ALL projects, PIs and study teams should submit a final information hazard assessment, repeating the Part I and Part II forms. (Note that if the project did not generate IHs, the PI simply checks “no” to Question 1.1 in the Part I form and Question 2.1 in the Part II form, and organizational leadership signs off, assuming agreement). This final assessment is looking for concordance with responses to the initial assessment, and the capture of unexpected information hazards generated during the project. The PI, organizational leadership and IRE (if assembled) work together on outcome determination and agree on recommendations, whether and how to disclose the information generated.

Appendix D. Instructions for Deriving Risk Scores and Using Matrix

Details of the derivation and descriptions of likelihood and consequence (impact) scores are provided in Chapter 4. The approach for deriving risk scores is under “Outcome Determination using Risk groups” in the same chapter. To summarize, PIs and study teams follow a 5-step process to derive nominal scores for the likelihood and consequence axes of the matrix.

Step 1: Nominal risk scoring from 1 to 5 likelihood and consequence scores using blank forms that can be downloaded in

Appendix B

Step 2: Calculate likelihood and consequence scores (average) using blank forms that can be downloaded in

Appendix B

Step 3: Derive “anchored” likelihood and consequence scores using blank forms that can be downloaded in

Appendix B

Step 4: Match anchored scores to appropriate risk group using the 5x5 risk matrix below

Step 5: Match risk group to outcome level and mitigation action using the 5x5 risk matrix

Likelihood scores range from 1 to 5 (“almost no chance” to “almost certainly”), while consequence (impact) scores range from 1 to 5 (“negligible impact” to “catastrophic impact”).

Nominal likelihood scores, descriptions, and reference probability ranges are shown below:

Likelihood Scores

Nominal consequence (impact) scores, descriptions, and operational definitions are shown below:

Consequence (Impact) Scores

Step 5 of the 5-step process matches likelihood and consequence scores for outcome determination using the following 5x5 matrix:

5x5 Risk Matrix for Assessment Outcome Determination and Mitigation Actions

To simplify the risk scoring and outcome determination process, we have created a spreadsheet toolkit that can be downloaded from

Appendix B. The 5x5 risk matrix in worksheet 4 (Outcome Matrix and Summary) auto-populates when scores are inputted into worksheets 2 (Likelihood Risk Scores) and 3 (Consequence Risk Scores) respectively.

About The Authors

Adejare (Jay) Atanda is a senior policy researcher at RAND. He conducts research at the intersection of traditional biological threats and critical emerging technologies policy. Atanda holds a DMD and a DrPH in public health analysis and epidemiology.

Matthew L. Nicotra is a senior physical scientist at RAND. His research focuses on biosecurity, emerging biotechnology risks, and the intersection of life sciences with national security. Nicotra holds a Ph.D. in ecology and evolutionary biology.

Benjamin Sperisen is a senior economist at RAND. He works on research relating to biosecurity and AI policy, including evaluation of potentially dangerous AI capabilities. He holds a Ph.D. in economics.

Elika Somani is a Research Project Specialist II and an M.A. candidate in National Security Policy at RAND. She conducts technical and policy research on the governance of AI and biological threats. She holds a B.A. in global health and development.

Henry H. Willis is a senior policy researcher at RAND and a professor of policy analysis at the Frederick S. Pardee RAND Graduate School. His work is on analysis of emerging and existential risks. He earned his Ph.D. in engineering and public policy.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).