Introduction

BWC Article X

1. The States Parties to this Convention undertake to facilitate, and have the right to participate in, the fullest possible exchange of equipment, materials and scientific and technological information for the use of bacteriological (biological) agents and toxins for peaceful purposes. Parties to the Convention in a position to do so shall also co-operate in contributing individually or together with other States or international organisations to the further development and application of scientific discoveries in the field of bacteriology (biology) for the prevention of disease, or for other peaceful purposes.

2. This Convention shall be implemented in a manner designed to avoid hampering the economic or technological development of States Parties to the Convention or international co-operation in the field of peaceful bacteriological (biological) activities, including the international exchange of bacteriological (biological) agents and toxins and equipment for the processing. use or production of bacteriological (biological) agents and toxins for peaceful purposes in accordance with the provisions of the Convention.

For the past 50 years, the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BWC) has stood as a bastion against the deliberate misuse of biology. But beyond its prohibitions against the development, production, possession, and acquisition of biological weapons, the treaty also contains positive obligations, including under Article X, which (1) obligates states parties to participate in international cooperation and assistance (ICA)—and enshrines their right to participate in the broadest use of biology for peaceful purposes—and (2) ensures treaty obligations are not implemented in a way that unnecessarily hinders access to biology for legitimate purposes (Text Box; Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention, 1975). The BWC prohibits biological weapons to both provide security against these horrific weapons and ensure that biological capabilities can be leveraged for good, a foundational consideration since negotiations on the treaty text (Conference of the Committee on Disarmament, 1971). Without fear of biological weapons, humanity is free to challenge the boundaries of biology to improve health and wellbeing. Like other aspects of the treaty, however, the text is open to interpretation, which has driven long-standing disagreements regarding its implementation.

Article X History

While a major point of contention today, Article X was not necessarily a principal concern when the treaty was drafted, nor in its early years, as the focus was primarily on disarmament and nonproliferation (Introduction, 2022; Littlewood, 2005, pp. 24, 164). The first introduction of ICA language in draft treaty text appeared in 1971, two years into the original negotiations, in a submission by Soviet states (Bulgaria, et al., 1971)—although similar language was present in drafts of a combined biological and chemical weapons treaty before the BWC was negotiated independently (Poland, 1970). The language largely mirrored that of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which entered into force in 1970 (United Kingdom, 2021; Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, n.d.; Littlewood, 2005, pg. 164). The non-aligned states1 submitted several amendments, including states parties’ obligation to cooperate on the “development and application” of biological advancements (Brazil, et al., 1971). This manifestation of low-and middle-income countries’ (LMICs’) efforts to bridge the development gap to higher-income countries did not appear to garner significant opposition, including from BWC depository states (United Kingdom, 2021; Littlewood, 2005, pg. 165). Beyond national security, Article X provided an added benefit to entice states that never had or considered an offensive biological program to join the BWC.

Attention toward Article X intensified over the treaty’s first several decades and into the treaty protocol negotiations (Introduction 2022; Littlewood, 2005, pg. 24, 164-168). With the growing power of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM Group), consisting largely of LMICs, Article X interpretation began to focus on states parties’ obligation to actively support development through ICA activities (Littlewood, 2005, pg. 24). Starting with the Second Review Conference, the Final Documents included specific measures to strengthen Article X, including calls to increase information exchange and engagement between scientists; strengthen training and education programs; improve disease surveillance systems and capacities; ensure national BWC national legislation and regulatory systems align with Article X obligations; expand coordination and collaboration with international and intergovernmental organizations (IO/IGOs), such as the World Health Organization, World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH, formerly OIE), and the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO); and bolster development and production capacity for vaccines and other drugs (Second Review Conference, 1986; Third Review Conference, 1991; Fourth Review Conference, 1996; Sixth Review Conference, 2006; Seventh Review Conference, 2011; Eighth Review Conference, 2016).2

As evidence of Article X’s growing importance, states parties included it among the four topics for the Ad Hoc Group to consider during treaty protocol negotiations, and it was among the most fiercely contested issues (Special Conference, 1994; Littlewood, 2005, pp. 169-172). States parties clashed over Article X’s purpose and scope, specifically regarding security and treaty implementation versus development. As negotiations progressed, the draft protocol began to converge around several concepts that aligned with the measures highlighted by previous Review Conferences: information exchange, training, and education; disease surveillance and prevention; research capacity; vaccines; technology transfer; biodefense; and national treaty and protocol implementation. In recognition of the overlapping scope of the BWC and other international treaties and organizations—and their relative capacities to support ICA—states parties included provisions to collaborate with various IO/IGOs, including WHO, WOAH/OIE, FAO, and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) (Littlewood, 2005, pp. 173-174). One contentious priority for the NAM Group was the formation of a Cooperation Committee—precursor to the modern ICA mechanism concept—which was originally envisioned as a body to facilitate Article X implementation, including consulting, monitoring, and reviewing ICA activities (Ad Hoc Group, 2001; Iran, 2023a). Major sticking points challenging broader support included the committee’s proposed authority to prescribe new measures under Article X or to assess states parties’ implementation and compliance (Littlewood, 2005, 174-175).

Export controls were another major point of contention during the Ad Hoc Group. There was broad agreement that they provided value in mitigating biological weapons proliferation risks, but some states parties viewed their implementation as discriminatory, particularly under the Australia Group, disproportionately burdening select non-allied countries, LMICs, and the Global South (Littlewood, 2005, pg. 139). Following similar efforts under the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), BWC export controls debate focused on whether they were even needed or provided value for states parties under a future verification regime (Littlewood, 2005, pg. 147). In fact, some states parties called for the removal of all restrictions on transfers between states parties; however, this issue was ultimately moot after the failure to agree on a treaty protocol (China, et al., 1994). Other issues included calls for integrating export controls under the BWC itself and establishing an adjudication function for transfer denials, which arise from differing perspectives regarding whether Article III obligations are a multilateral or national responsibility. Export controls were fiercely divisive during the negotiations, which may have hindered progress on other issues (Littlewood, 2005, pp. 147-152).

The protocol negotiations laid the groundwork for future Article X debate, which continued throughout the subsequent Intersessional Programmes (ISPs), held in the periods between Review Conferences since 2003 (Fifth Review Conference, 2002). Article X and ICA (and ICA mechanism) were fixtures of the Meetings of Experts (2003-2021), and associated recommendations and proposals appeared in numerous working papers during that time. The ICA mechanism built momentum in recent decades, and substantive debate molded the idea into a concrete concept in a position to potentially be finalized during the ongoing BWC Working Group on the Strengthening of the Convention (Working Group).

Article X Implementation

As with other aspects of the BWC, the Article X text (Text Box) is insufficient to facilitate full or consistent implementation of its obligations (Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention, 1975). In the absence of a treaty protocol, the scope of Article X activities and the standard against which to assess compliance remain undefined (Kenya, et al., 2021). Because the responsibility for implementation falls on states parties themselves, they each operate on their own interpretation, resulting in varying perspectives on their compliance. Allegations of noncompliance include insufficient volume of ICA activities; failure to meet states parties’ needs or requests, particularly regarding access to emerging biotechnology capabilities; and formal barriers to international transfer of knowledge and materiel for legitimate purposes, such as export controls, sanctions, and embargoes. This debate is often led by the NAM Group—particularly Cuba, Iran, and Venezuela—which frequently decries “unilateral coercive measures” (UCMs; e.g., sanctions, embargoes), particularly those implemented by the United States. They argue that these mechanisms violate Article X by hindering importation of critical biological and health materiel, negatively impacting national health, scientific advancement, and economies (Uganda, 2024; Cuba, 2022; Iran, 2024; Venezuela, 2022). For their part, states parties facing these allegations argue that they conduct a considerable volume and variety of ICA activities and that they do not prohibit or limit transfers for legitimate activities (United Kingdom, 2023; United States, 2024).

Another concern related to Article X is the risk that the nature of ICA activities could be misrepresented to undermine legitimate collaborations (United Kingdom, 2023). Facing uncertainty and opposition stemming from mis- and disinformation efforts, governments could be hesitant to engage in future international partnerships, further hindering Article X implementation. In a recent example, Russia invoked BWC Articles V (only the second time history) and VI (the first time ever) in 2022, alleging that US-supported Ukrainian public health laboratories violated Article I of the treaty (Russian Federation, 2022; Security Council Rejects Text, 2022)—similar to previous allegations against Georgia (Vindman, 2022). Georgia, Ukraine, and the United States maintain that their bilateral partnership activities are legitimate, in support of critical public health functions, and crucially, have been publicly documented for many years. Ukraine and the United States argue that Russia’s allegations serve to further disinformation efforts related to its invasion of Ukraine earlier that year (Georgia & Germany, 2018; Ukraine, 2022; United States, 2022a). At the 2022 Formal Consultative Meeting, convened under Article V, several states parties argued that these kinds of activities are prime examples of Article X implementation and that such allegations risk undermining legitimate ICA activities and hindering future Article X implementation (Australia, 2022; Canada, 2022; Estonia, et al., 2022; Norway, 2022; Poland, 2022; Republic of Korea, 2022; Slovakia, 2022).

Article X Database & Reports

In 2011, states parties took concrete steps to increase transparency and awareness of ICA activities and to facilitate future partnerships. The Seventh Review Conference formally encouraged states parties to provide biennial3 reports on their Article X implementation, which serve as a contemporary analogue to Article X declarations discussed in the protocol negotiations (Seventh Review Conference, 2011, pg. 17; Littlewood, 2005, pp. 24, 176). While few Article X reports have been submitted to date—39 reports across 12 states parties and the European Union, plus the Global Partnership Against the Spread of Weapons and Materials of Mass Destruction (Article X Reports, 2024)—they provide a platform for states parties to publicize their international collaborations. The 2012-15 ISP also included Article X reports under the standing ICA agenda item and established the Article X database “to facilitate requests for and offers of exchange of assistance and cooperation among States Parties.” The database was designed to enable states parties to identify potential partners, and the decision directed states parties to document successful ICA activities coordinated via the database (Seventh Review Conference, 2011, pp. 22-23; Assistance and Cooperation Database, 2024). Offers posted in the database are publicly visible, but requests are restricted to states parties, in part to mitigate the impact of sharing gaps and vulnerabilities. The BWC Implementation Support Unit (ISU) regularly reports on Article X implementation reported by states parties, provides basic statistics regarding use of the Article X database, and facilitates some ICA partnerships using information posted in the database (Implementation Support Unit, 2022; Assistance and Cooperation Database, 2024).

ICA in the BWC Working Group

The Ninth Review Conference established the Working Group as the 2023-26 ISP format, mandating states parties to develop “specific and effective measures, including possible legally-binding measures” for consideration at the Tenth Review Conference (2027). Notably, ICA is the first of six specific topic areas in the Working Group mandate, even before verification and compliance, and states parties agreed to establish a mechanism “to facilitate and support the full implementation of [ICA] under Article X,” charging the Working Group with determining the relevant details (Ninth Review Conference, 2022).

The Working Group thus far has featured several concrete proposals and substantive debate on ICA issues. The original vision for the Cooperation Committee persists, including in proposals by Iran and the NAM Group (Iran, 2023a; Azerbaijan, 2022b), and other proposals take a variety of approaches to the mechanism’s composition, role, and funding, with varying degrees of agreement and divergence (ASEAN, 2023; Australia, et al., 2023; Iran, 2023a; Pakistan, 2023). Most of the convergence, however, is around a model with a narrower focus on facilitating Article X implementation, rather than assessing compliance or adjudicating transfer denials. The proposed models generally consist of a larger directive body open to all states parties and a smaller operational body with rotating membership. Exact details vary, however, particularly regarding membership, mandate, and funding. In an effort to facilitate progress toward consensus, the Working Group Friends of the Chair for ICA, Canada and the Philippines, presented a hybrid model, drawing from the existing proposals and convergence identified in the Working Group debate (Canada & Philippines, 2024a; Canada & Philippines, 2024b). Other proposals and working papers take a broader view of Article X, including issues related to addressing UCMs and export controls, establishing an ICA action plan to meet states parties’ needs, strengthening BWC national implementation, expanding Article X reports, updating the Article X database, and resuming treaty protocol negotiations (Azerbaijan, 2022b; Iran, 2023b; United Kingdom, 2023; United States, 2023).

The Friends of the Chair proposal includes a 20-member ICA Steering Group to manage the program and associated voluntary trust fund, as well as additional ISU staff to provide support. The Steering Committee would have its own dedicated annual meeting, and a Cooperation Advisory Group would meet in conjunction with the annual Meeting of States Parties, providing all states parties a forum to oversee Steering Group activities and address concerns regarding Article X implementation. Review Conferences would retain ultimate decision-making authority for the mechanism (Canada & Philippines, 2024b). H.E. Ambassador Frederico S. Duque Estrada Meyer of Brazil, Working Group Chair, presented his vision for finalizing details of the ICA mechanism, based on this model, alongside a science and technology review mechanism at a Special Conference, then shifting focus and resources to other Working Group topics (Brazil, 2024). This appeared to have broad support at the December 2024 Working Group meeting, but it was unable to attain consensus (Guthrie, 2024, December 10; Guthrie, 2024, December 16). At an April 2025 BWC 50th Anniversary event, Ambassador Meyer described his plan to hold more concrete negotiations in 2025 on language for a future decision, including on an ICA mechanism (U.N. Institute for Disarmament Research, 2025).

ICA Assurance Study

This study is part of an ongoing series of BWC assurance research, which addresses certainty in states parties’ compliance with their treaty obligations. Similar to previous assurance studies, our goal is to characterize the landscape of perspectives on these important and complex issues, based on direct input from BWC delegations and other stakeholders (Shearer, et al., 2023; Shearer, et al., 2024). Ultimately, we aim to identify priorities for further Working Group attention and concrete opportunities to strengthen treaty implementation as states parties look ahead to the Tenth Review Conference.

Methods

This study utilizes the same mixed-methods analytic methodology as our previous BWC assurance studies, with minor updates (Shearer, et al., 2023; Shearer, et al., 2024). The combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis of interviews with BWC delegations and other international stakeholders allowed us to systematically and rigorously document the landscape of perceptions associated with BWC Article X, ICA, and related concepts.

We developed a semi-structured interview guide (Supplement 1) based on a scoping literature review—including ICA mechanism proposals, other BWC meeting documents, and independent analyses of Article X and ICA debate—as well as personal experience related to BWC proceedings, statements, and deliberations. Interview topics focused on interviewees’ ICA experience; the purpose, scope, and value of Article X and ICA in the BWC; the role of Article III, export controls, and sanctions in the context of ICA; and opportunities to strengthen ICA and Article X implementation. The interview guide included specific topics and questions; however, the semi-structured format allowed interviewees to direct the conversation based on their individual experiences and priorities.

From June 2024 to January 2025, we conducted key informant4 interviews with BWC delegation members and other stakeholders, including individuals affiliated with academic institutions and other civil society organizations, the BWC ISU and other nonproliferation and health-focused IO/IGOs, and current and former BWC delegation members who participated in their individual capacity. We identified prospective interviewees based on relevant expertise and institutional affiliations—including participation in BWC and other nonproliferation meetings—utilizing purposive sampling to promote diverse geographic, political, economic, and demographic perspectives. We invited 170 individuals and offices across 85 countries. We conducted interviews via videoconference, in person, and via written response. All interviews were held on a not-for-attribution basis to promote candor and transparency. We recorded audio for virtual and in-person interviews, with participants’ consent, and supplemented with written interview notes. We generated automated transcripts, using Otter.ai (Version 3.67.0), and reviewed and corrected all transcripts, as needed, to improve accuracy prior to coding.

The initial thematic coding framework was based on topics identified from the interviews themselves, as well as sentiment and organizational codes used in previous BWC assurance studies. The coding team piloted the coding framework on a subset of interviews and revised, added, and reorganized codes, as necessary. The final coding framework includes 67 codes, organized hierarchically into five categories to facilitate coding: subjects, such as ICA mechanism and scope of activities; outcomes, including the purpose and intended and unintended effects of ICA activities and mechanisms; illustrative examples, describing proposals or other experiences or references; roles, identifying actors involved in various activities; feasibility, reflecting factors affecting the possibility or probability of specific actions or changes; and sentiment, representing interviewees’ perception of various subjects. Four team members performed qualitative coding on transcripts, written responses, and interview notes—using NVivo qualitative coding software (Release 14.23.3). As new themes emerged during the coding process, new codes were added to the framework, and the coders reviewed completed interviews using the new codes. Interviews were classified by various characteristics to facilitate stratified analyses. In addition to “delegation” and “independent expert” used in previous studies, we added “international/intergovernmental organization” (IO/IGO) due to expanded inclusion of these organizations to understand how they address ICA. Interviewees were also classified by their experience as donors or recipients of BWC ICA and, for delegations, BWC regional group and World Bank income group (Membership and Regional Groups, 2025; World Bank, 2025). At least one team member reviewed all coding for quality control, and the coders resolved coding discrepancies and questions by consensus.

Using NVivo and Microsoft Excel, we quantified the frequency of code usage and co-coding—i.e., multiple codes assigned to the same content—to determine the cumulative total instances and number of interviews for each code or pair. We also generated group-specific metrics, weighted to account for the size of each group, to identify themes discussed more frequently by one group than another, potentially signaling differences in how they prioritize certain topics. For the final thematic analysis, we prioritized individual codes utilized in more than half of the interviews and those with weighted differences of 50% or greater between delegations and non-delegation interviewees (i.e., IO/IGO and independent experts), LMICs and high-income countries, and other weighted metrics with at least 6 participants. High prevalence of co-coded pairs signaled key aspects of priority codes for further investigation. Due to unbalanced participation, we did not analyze weighted metrics for BWC regional groups. We also identified priority codes a priori based on relevant debate in BWC meetings, associated literature, specific statements that stood out during the interviews, and our own expertise and observations. This enabled us to include minority perspectives and other important or interesting content that was not addressed across numerous interviews. The data-driven thematic findings below document interviewees’ comments; they are not intended to be representative of BWC states parties or other stakeholders. We do not make any judgements regarding the validity or value of any particular position.

The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board determined that this study did not constitute human subjects research due to the use of a key informant methodology (IRB00029115; Not Human Subjects, 2022).

Results

Quantitative

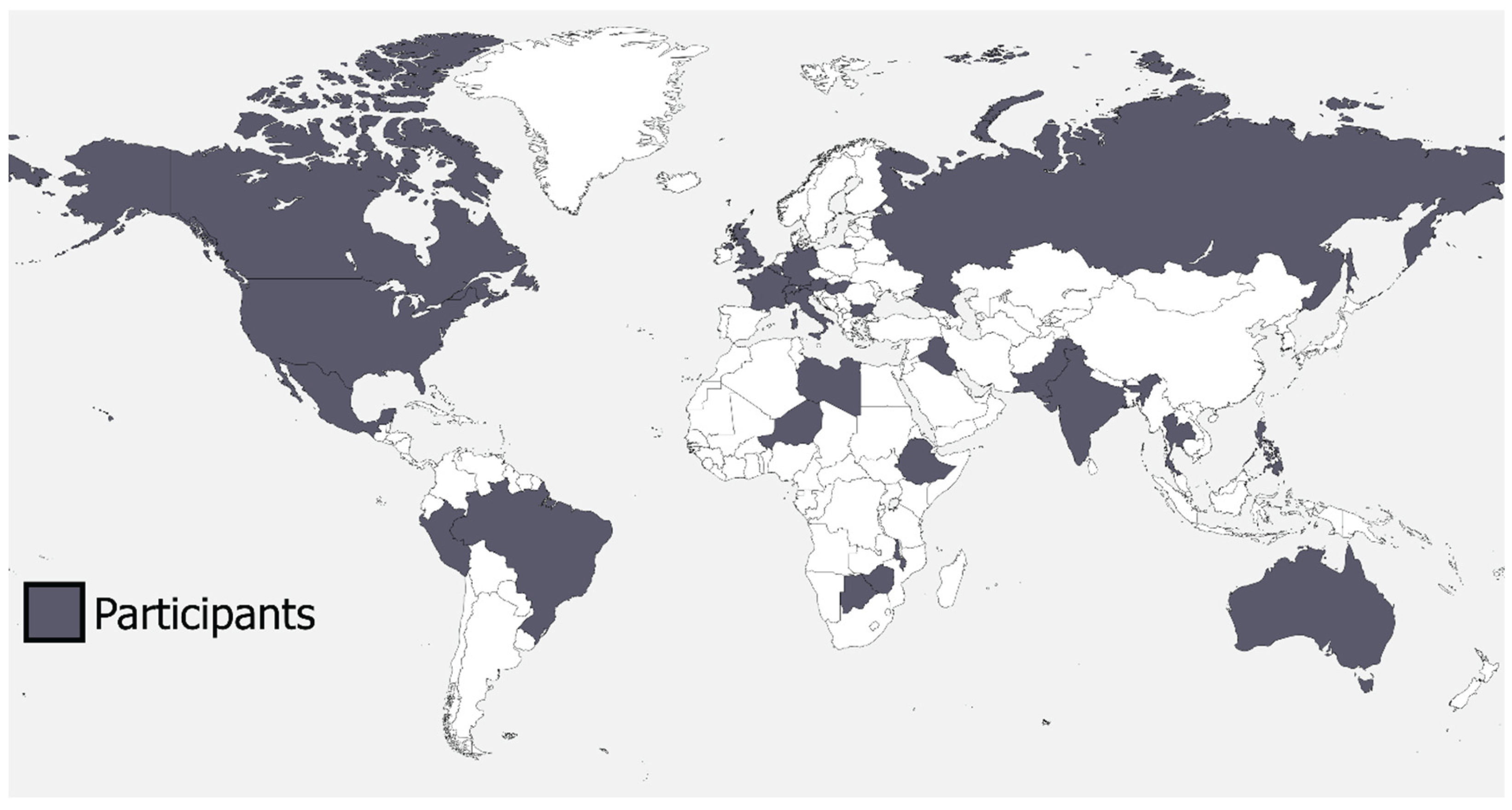

We conducted 35 interviews with 48 total international experts: 18 interviews with 29 individuals who work on or with BWC delegations, 7 interviews with 9 experts from IO/IGOs, and 10 interviews with 10 independent experts. Interviewees represented 26 countries across 6 continents, including all BWC regional groups (

Table 1;

Figure 1). Interviewees’ characteristics are shown in

Table 2. Participants included the outgoing Working Group Chair, both Friends of the Chair for ICA, and the BWC ISU, providing critical inside perspectives. Thirteen BWC delegations and two independent experts declined to participate.

Thematic coding generated 4,896 total coding references (Supplement 2) and 9,392 co-coded references (Supplement 3). Of the 67 total codes, 39 individual codes and 11 co-coded pairs were addressed in more than 50% of interviews. The use of descriptors below (e.g., “several”, “numerous”) represent the relative frequency that certain perspectives or topics were addressed by interviewees; however, these pertain only to the interviews themselves and cannot be extrapolated to BWC states parties or other stakeholders. States parties can be both ICA donors and recipients, depending on the scenario, and the descriptors “donor/offering” and “recipient/requesting” apply to their respective roles in specific partnerships or contexts.

Thematic

Article X Implementation

One of the most consistent themes across our interviews was uncertainty and disagreement regarding how Article X should be implemented, relating to the purpose of the article itself and the treaty as a whole. Article X’s dearth of detail and absence of an implementation standard or metric results in varying perspectives regarding the volume and scope of activities that constitute compliance. Interviewees’ perspectives on Article X obligations generally aligned with their views on the BWC’s security and development roles.

With respect to the volume of ICA activities, need will inevitably exceed available offers. One IO/IGO interviewee indicated that even with a large budget, a treaty or organization will never meet global demand. Within the BWC, the Article X database hosts more requests (76) than offers (30), illustrating this disparity (Assistance and Cooperation Database, 2024). Numerous interviewees, across all characteristic groups, concurred that states parties could always do more in terms of ICA, one of the few areas of agreement. Many also acknowledged, however, that there are practical limitations on those activities. There exist many outstanding needs and requests for assistance, but states parties, as a whole, already conduct a large volume and broad scope of ICA. Governments also have finite resources to support these activities, particularly considering the countless competing demands they face. Importantly, however, ICA does not always rely heavily on financial or material resources. Interviewees described a variety of other activities such as in-kind support—including technical exchange, laboratory twinning, and training programs—and regional workshops to share lessons and best practices (e.g., for national legislation or Confidence-Building Measures [CBMs]) as ICA opportunities, even for states parties and other stakeholders without excess resources or advanced capabilities to share. One independent expert asserted that BWC debate on this issue does not necessarily reflect the situation in some countries. Because Geneva-based diplomats may not be aware of technical activities taking place at home, some rely on political positions that Article X is not being implemented. The reality is likely somewhere in the middle.

Debate on Article X’s scope frequently pits security and nonproliferation against development and more traditional public health and healthcare. Multiple delegations—particularly NAM Group members and LMICs—asserted that capacity building and development are core BWC components, part of what one participant described as the “grand bargain,” in which states parties agree never to pursue biological weapons in exchange for access to biological tools and capacities for peaceful purposes. Others—commonly delegations and independent experts from Western Group and higher-income countries, although not exclusively—maintained that the BWC is principally a disarmament and nonproliferation treaty, so Article X obligations should focus on deliberate biological threats and associated treaty obligations, including national implementation. One independent expert argued that Article X was originally intended to ensure treaty implementation did not hinder legitimate activities, not to actively facilitate ICA. This discrepancy has resulted in varying perspectives on Article X’s role related to national implementation, treaty universalization, deliberate event preparedness and response, broader health security and capacity building, biology and biotechnology research and development, and economic benefits. Delegations indicated that differences in the content of Article X database offers and requests illustrate this divergence. Requests focus more on capacity building or international transfer of biological materiel and technologies, compared to nonproliferation or national-level treaty implementation contained in offers. Interviewees emphasized the overlap between preparedness and response capacities for natural, accidental, and deliberate biological events—strengthening one strengthens the others—but while Article X clearly establishes states parties’ right to pursue these activities—and states parties do support ICA across all biological threats—there is no consensus regarding the extent to which it obligates them to provide broader capacity building or technology transfer, as opposed to focusing on deliberate biological threats.

In the absence of formal guidance or standards, donor states parties support ICA activities as they deem appropriate. While they implement a considerable volume and variety of activities that benefit recipient states parties around the world, some interviewees indicated that these activities may align more closely with donors’ priorities than requesting states parties’. Disagreement remains regarding whether those activities, irrespective of volume, equate to Article X compliance if they do not meet states parties’ requests. Donor states parties frequently pointed to the volume and variety of ICA activities as evidence of their compliance, but some requesting states parties countered by citing outstanding needs as evidence of gaps in Article X implementation. One frequently cited outstanding request is the transfer of biology and biotechnology capabilities and equipment, which LMICs hope can help them close the development gap to higher-income countries and reduce reliance on North-South assistance.

The BWC is a treaty between states, but ICA activities are implemented by a variety of actors, including regional organizations, IO/IGOs, and civil society or private sector partners. It also overlaps with numerous other treaties and organizations—including those focusing on human, animal, plant, and environmental health (e.g., WHO, WOAH, FAO)—which have their own ICA programs. Functions such as implementing epidemic preparedness and response, setting laboratory biosafety and biosecurity standards, strengthening public health and healthcare capacities, and conducting biological research and development yield benefits across the full spectrum of biological threats, and interviewees did not identify a clear delineation between these various fora. Many activities implemented outside of the BWC address more traditional healthcare and public health capacities, and technology transfer may be facilitated by private sector businesses or industries. Numerous participants emphasized that these overlaps demand that the BWC make efficient use of its limited resources, to both mitigate duplicative efforts and leverage other organizations’ expertise and resources within their scope of responsibility to supplement BWC ICA.

Export Controls

Some states parties argue that export controls—and other formal restrictions, like sanctions—prevent them from accessing materiel and capabilities for legitimate purposes, while others contend that it is their sovereign right—and indeed, their obligation—to guard against the misuse of biology. Participants broadly supported the use of export controls, regardless of geography, BWC regional group, or income classification. One independent expert emphasized that they do not prohibit international transfers, but rather, ensure appropriate protections are in place. Numerous interviewees described them as an essential tool for protecting against the misuse of biology for that exact reason. Superficially, BWC Article III places restrictions on the transfer of biological materiel and capabilities, whereas Article X promotes the broadest access to biology. This could give the impression of a conflict, particularly in the context of debate around export controls; however, interviewees, particularly delegations, consistently emphasized that these articles serve complimentary roles by ensuring the appropriate use of biology, functioning as “two sides of the same coin.” One independent expert stressed that perceived tension between these articles has been stoked by certain states parties for political purposes. Interestingly, several interviewees—including from the NAM Group—described benefits beyond nonproliferation, specifically that export controls actually facilitate ICA by reassuring everyone that the importing partner has implemented effective risk mitigation measures. One interviewee commented that the Australia Group has essentially set the de facto global standard, which ensures that prospective importers know the expectations in advance, making it easier to secure international transfers.

In principle, export controls should apply equally across all countries, but there are concerns regarding consistent implementation. One NAM Group delegation argued that, if implemented properly, export controls should not unnecessarily hinder legitimate activities, but they can easily be manipulated to do so, if desired. Similarly, one independent expert noted that the same dual-use risks that necessitate the export controls’ existence can easily provide justification for transfer denials, making it difficult to determine if they are implemented consistently. One of the primary arguments against the Australia Group is a lack of transparency outside of its limited membership, particularly regarding justification for transfer denials. Not knowing the reason behind denials does not allow affected entities to contest those decisions nor inform them how to remediate their existing risk mitigation measures. One interviewee reiterated that this information is not currently shared publicly, which contributes to perceptions of inconsistent application, specifically that transfers are selectively denied under the guise of security concerns.

Some delegations called for bringing export controls under the BWC, in an effort to resolve these issues. Two long-standing proposals—establishing a BWC-specific export control regime and an adjudication body to resolve concerns about transfer denials—address the underlying complaint that these regimes, particularly the Australia Group, have limited membership that excludes some states parties from decision-making processes. One independent expert countered that, despite its limited membership, the Australia Group’s policies apply to anyone with whom they trade, theoretically placing everyone on equal footing. One NAM Group delegation that called for a dedicated BWC export control regime argued that expanded membership would increase transparency into associated practices and policies. A BWC adjudication function would notionally provide recourse for states parties that believe they have been wrongly denied transfers or licenses for legitimate activities. Opponents of these proposals again cited their national obligation and authority, under Articles III and IV, arguing that a consensus-based approach would risk weakening these protections and that an independent body controlling those decisions would risk infringing on national sovereignty.

Compared to export controls, most participants had little or no direct experience with sanctions, but several noted that they can have similar effects in some instances, although they are utilized for punitive purposes rather than risk mitigation. Several participants emphasized that sanctions typically include exceptions for health and humanitarian purposes, and multiple donor state party delegations and independent experts disputed allegations of substantial transfer denials for these purposes. Multiple interviewees referenced data showing very few sanction-related denials, and several, including donor state party delegations, described claims of transfer denials as exaggerated. In contrast, one independent expert described significant barriers to obtaining equipment and supplies for medical research and development purposes, hindering legitimate activities such as vaccine development. Past statements and presentations by Cuba, Iran, and Venezuela highlight similar impacts (Cuba, 2022; Iran, 2022; Iran & Cuba, 2024; Venezuela, 2022). Several interviewees—including from donor countries—acknowledged that while exemptions exist, sanctions may still pose practical barriers to some transfers, such as governments’ or private organizations’ willingness to navigate license or exemption processes. Others described negative impacts stemming from the mere existence of sanctions, as potential partners may not want to risk upsetting governments in countries where they do business by conducting transfers with entities facing sanctions. Multiple interviewees emphasized that their governments do not control private sector organizations and cannot compel them to conduct these kinds of transfers. Official transfer denial data would not reflect transfer or license requests that are never initiated, illustrating a gap in existing data that poses a barrier to understanding the full effect of these policies. It is difficult to fully characterize the impact of sanctions on international transfers for legitimate purposes without more targeted analysis, particularly including input from affected countries or organizations. One Western Group delegation suggested that most states parties are willing to address practical barriers, but it is unclear what process that would entail.

Article X Database & Reports

The Article X database provides a platform for states parties to post assistance requests and offers, but interviewees identified myriad philosophical and practical barriers to its effective implementation. Perceptions of the database’s purpose varied among delegations, with some viewing it as a matchmaking tool to actively pair requests and offers, frequently assisted by the ISU, and others viewing it more as a clearinghouse to distribute assistance offers and requests. Multiple interviewees, including delegations, questioned the database’s utility, in part due to limited data demonstrating its successes. Interestingly, no interviewees were able to cite successful partnerships established through the database. In fact, multiple interviewees with experience on donor state party delegations observed that they were unaware of any responses to their offers. States parties are encouraged to document ICA successes in the database, but limited examples make it difficult to assess the database’s ability to facilitate ICA activities. As noted above, delegations described a mismatch between the content of database offers and requests, but there are other functional barriers that result in states parties working around the database, rather than through it.

In lieu of using the database as intended, with offering states parties responding to requests and vice versa, interviewees described an alternative pathway that effectively circumnavigates the database. Requesting states parties will frequently approach the ISU for assistance in identifying prospective donors. The ISU then identifies appropriate offers and facilitates contact between the two states parties directly. While the ISU can function as an intermediary, and this process has reportedly produced successful partnerships, it is already under-resourced. Additionally, working outside the database poses another barrier to documenting successes in the database itself, further compounding challenges to demonstrating its value. Interviewees suggested that one potential reason for this approach is states parties’ reluctance to post requests, or the requests that do exist may lack the specificity required to identify partners. States parties may be hesitant to reveal vulnerabilities, or they may not have a clear understanding of their needs. For example, a state party may want help strengthening national implementation, but it may not know where to start, making it difficult for offerors to determine if they can meet their needs. The absence of clear requests—and potentially the same for offers—makes it difficult for states parties to understand what kinds of ICA activities are needed or available.

Article X reports provide a platform to increase transparency regarding states parties’ Article X implementation and raise awareness about the types of assistance available, but interviewees described limited value in those respects. While the reports that are submitted describe a considerable scope and volume of activities, one independent expert emphasized that even lengthy reports represent only a snapshot of the ICA activities conducted around the world. Additionally, one of the few delegation interviewees with experience reviewing Article X reports indicated that they largely exclude IO/IGO and civil society activities, which represent a substantial proportion of ICA. Considering the limited participation, those data are only available for a small handful of states parties, most of which do not participate consistently (Article X Reports, 2024). Numerous interviewees acknowledged that they do not review the reports regularly or at all, so they are not making use of the available data. One interviewee suggested that the reports are likely more beneficial for the submitting states parties, to publicize their activities, than to others. Multiple interviewees advocated for a more structured form or template to facilitate increased participation, but Article X reports seemed to be a low priority for most.

Article X Proposals

One of the principal opportunities to strengthen BWC Article X implementation is through establishing an ICA mechanism—one of the Working Group’s explicit mandates—which had broad support across our interviewees, including numerous delegations. Several delegations noted that there is interest among the Working Group—and pressure—to secure a “win” by finalizing an agreement sooner than later. States parties have debated this issue for years and made substantive progress toward convergence on key characteristics, and interviewees emphasized that establishing a mechanism could build momentum and enable states parties to shift focus to other priority issues, including verification and compliance.

Interviewees suggested a variety of characteristics for a prospective ICA mechanism, in both format and function, which align with various existing proposals. They discussed both limited and open-ended participation models for various functions of the mechanism. Open-ended options would allow participation by all states parties, but some interviewees cautioned that well-known challenges in achieving consensus could prevent the mechanism from taking timely action and implementing ICA activities. A smaller body could be more nimble and responsive, but it would not incorporate input from all states parties, a demand by some delegations. There are also questions regarding representation. Historically, representation in BWC bodies or official positions is based on BWC regional groups, but multiple interviewees argued that this would not be sufficient to include representative input, particularly from states parties in the most need of assistance. NAM Group and LMIC interviewees noted that the NAM Group varies widely in terms of geography, economic classification, political structure, and technical capabilities and highlighted the importance of ensuring their voices are represented. Several interviewees suggested that basing membership on geographic region would better represent states parties’ perspectives. Multiple hybrid models have been proposed, with both an open-ended component (e.g., to provide guidance and direction) and a smaller, limited body (e.g., for operational implementation). These aim to provide flexibility, but several interviewees acknowledged that multiple bodies would require additional meeting time, further straining the BWC’s limited resources.

Calls to funnel ICA activities through the BWC, potentially via an ICA mechanism, were met with skepticism regarding the practical impact on ICA activities. Establishing a BWC-specific mechanism to coordinate ICA activities could be more responsive to states parties’ needs, expanding the volume of international collaboration and aligning ICA with requests. This could take various forms, ranging from active review, selection, and implementation of ICA proposals to a more passive matchmaking or clearinghouse function. Some donor states parties counter that channeling ICA activities through a BWC-specific mechanism could serve as a chokepoint and hinder the broad scope of activities already taking place, especially if politics become a factor in ICA decision-making. Additionally, one independent expert emphasized that governments do not simply have excess, unused resources to suddenly allocate to the BWC. Establishing an ICA mechanism would not alleviate existing resource limitations, so it could supplement current processes, but not supplant them.

There are also differing perspectives regarding the scope of activities that fall under Article X, compared to those coordinated through a BWC-specific mechanism. For example, one donor state party delegation argued that Article X covers a broad scope of health-related capacity building and scientific cooperation—and that it should receive “credit” for supporting those activities—but when discussing the activities that should be coordinated through an ICA mechanism, it took a narrower approach, emphasizing the need to identify and remain within the “BWC’s niche” to avoid duplicating activities implemented through other fora. In contrast, competing models envision the mechanism as a tool for increasing ICA and responding to states parties’ requests across a broad scope of needs, including those currently addressed via other pathways. In the absence of an ICA mechanism, the vast majority of existing ICA activities are coordinated outside the scope of the BWC, including through bilateral agreements, regional organizations, IO/IGO programs, and civil society or private sector projects. Notably, one NAM Group delegation interviewee emphasized that success should be judged by the impact of ICA activities, rather than the mechanism by which they are implemented, so ensuring the appropriate volume and scope of activities is more important than funneling them through a BWC-specific mechanism.

In light of existing resource limitations on the BWC, funding was a contentious topic. Interviewees discussed both voluntary and assessed (i.e., mandatory) contributions to fund an ICA mechanism, as well as states parties’ ability to earmark or restrict funding for specific activities or recipients. Unrestricted funding provides flexibility to address states parties’ evolving needs, as opposed to donors’ priorities; however, those opposed to unrestricted funding cited concerns about dual-use risks and funding activities that fall outside the scope of Article X, as well as restrictions on the use of government funds for certain purposes or partners (e.g., established in national legislation). Assessed contributions would provide stability and consistency, enabling better long-term planning and implementation. Some interviewees discussed a hybrid funding model, utilizing both voluntary and assessed contributions, such as supporting the mechanism’s operations (e.g., meetings, administrative support) through assessed contributions, while voluntary funds could be used for ICA activities selected or implemented through the mechanism, with the option to earmark funds for specific activities.

In addition to the ICA mechanism, the Working Group is tasked with developing a science and technology review mechanism. Multiple delegations expressed support for both mechanisms, with several calling to finalize them in tandem, particularly in a so-called “early harvest” before the end of the Working Group mandate, potentially mutually beneficial for the development and implementation of both mechanisms. The Working Group could allocate more time to other priorities, accelerating progress on those issues. Reaching consensus on two mechanisms simultaneously could prove more difficult than negotiating one at a time, but it could also provide additional opportunity for compromise.

International/Intergovernmental Organizations, Civil Society & the Private Sector

Various other treaties and organizations overlap with the BWC (e.g., WHO, WOAH, CWC/OPCW), and their ICA efforts could offer lessons and models that could be adapted for the BWC, including demonstrated viability of multiple approaches to funding and implementing ICA mechanisms. One interviewee noted that these organizations “are sitting at the same table, but on different sides,” emphasizing the different avenues they take to strengthen global health security.

IO/IGO interviewees described a variety of funding models, including assessed contributions, voluntary contributions, and hybrid models to support ICA mechanisms themselves, activities they coordinate, and other ICA efforts. In describing her/his organization’s voluntary funding model, one interviewee noted that longstanding pressure to contribute effectively renders states parties’ participation obligatory. Several IO/IGO interviewees stressed the importance of unrestricted funding to better meet states parties’ evolving needs, rather than donors’ priorities, at least for a subset of priority activities, such as those aimed at core treaty functions. They also emphasized the importance of reliable, sustainable funding, particularly its value in facilitating long-term planning and implementation. This is not, however, something the BWC can expect to solve overnight. In some cases, this required many years of effort and/or a large up-front investment to establish a strong financial foundation that enables these mechanisms to focus on their core purpose, rather than “begging” delegations for funding. Some IO/IGOs also have cooperative agreements among themselves, creating a broader network of ICA capacities, resources, and opportunities that extend beyond those of a single institution.

IO/IGO interviewees emphasized that ICA mechanism discussions must look beyond simply establishing the body and address the political, legal, and administrative support needed to ensure its effectiveness. While several interviewees highlighted the political barriers that often hinder progress in international fora, others cited BWC states parties’ demand and purpose in developing a BWC-specific mechanism. States parties have signaled their support for an ICA mechanism in principle, but it will take true political will to negotiate the necessary compromises. Ongoing debate around the mechanism’s format and functions needs to address administrative considerations, including decision-making processes, direction and oversight from states parties, and organizational support. In addition to facilitating partnerships, an ICA mechanism must also address legal issues, such as the status of personnel operating in other countries and ownership of equipment and/or materials in order to establish an environment conducive to effective ICA.

IO/IGO interviewees also shared lessons on ICA more broadly, with a particular focus on efficiency. In addition to mitigating duplicative efforts across relevant treaties and fora, they also shared experiences to expand the impact of ICA activities using limited available resources. “Train-the-trainer” models, for example, allow for greater transfer of knowledge and skills by establishing a sustainable capacity that can persist and grow beyond the original partnership, compared to multiple independent, one-off activities. In a similar vein, one delegation interviewee described her/his government’s experience receiving assistance in completing its CBM, and subsequently, it was able to serve as a donor by sharing experiences and lessons with regional partners. Multiple IO/IGOs are also able to accept funding from civil society to support ICA activities (i.e., not just states parties), expanding the base of available support and reducing the burden on states parties to meet global demand. One interviewee also argued that in an increasingly contentious geopolitical climate, civil society organizations may have more flexibility in navigating barriers to implement ICA partnerships that state governments cannot. And beyond resources, IO/IGOs, civil society, and private sector business and industry possess knowledge, skills, and technical and operational capacity that can be leveraged to make increase the impact of BWC-specific resources for BWC-specific needs.

IO/IGO interviewees also discussed advantages of distributed models for coordinating ICA. A centralized model could draw from a consolidated pool of resources and streamline application, review, and implementation processes; however, IO/IGO regional offices or other multilateral organizations may have a better understanding of national-level needs, priorities, and systems, which would provide valuable insight when evaluating or implementing ICA proposals. Interviewees also discussed how activities coordinated and targeted at the regional or subregional levels could more broadly benefit countries with similar capacities, needs, and goals, making more efficient use of available resources and facilitating increased South-South collaboration. A combination of centralized and distributed approaches could also be an option to leverage the relative strengths of both models. A BWC-specific mechanism would provide a central hub for these activities, but regional input and coordination could bolster BWC-related ICA activities and resources.

Discussion

The Working Group’s mandate directs states parties to develop a mechanism to facilitate Article X implementation, providing clear direction on their ICA efforts during the current ISP. But while this is the priority, myriad opportunities exist to expand ICA activities under the BWC. To paraphrase several interviewees in our original BWC Assurance study, there are no new ideas in the BWC (Shearer, et al., 2023), but while some of these issues and proposals have been tabled in the past, including during the protocol negotiations (Littlewood, 2005, pp. 169-172; Ad Hoc Group, 2000), contemporary circumstances may shed new light on their value and viability. Some options necessitate consensus agreement, such as establishing an ICA mechanism or updating the Article X database or reports, but informal options can also be implemented voluntarily on a unilateral, bilateral, or regional basis to strengthen ICA.

Article X Purpose, Scope & Standards

Much like other BWC issues, ICA challenges stem from uncertainty regarding the purpose of the treaty itself and what states parties want to gain from implementation and compliance (Shearer, et al.; 2023; Shearer, et al., 2024). In particular, disputes between the relative importance of the treaty’s security and development aims directly impact debate regarding Article X’s purpose, scope of activities, and obligations (Littlewood, 2005, pp. 171-172; United Kingdom, 2021). Since the treaty opened for signature, states parties have joined for a variety of reasons, including security protections and the promise of access to biology for peaceful purposes, which color their perceptions of these obligations. This is not unique to the BWC; other arms control, disarmament, and nonproliferation treaties face similar challenges. Some ICA aligns more closely with the BWC’s nonproliferation and security focus (e.g., national implementation, deliberate biological event preparedness and response, laboratory biosecurity, treaty universalization). Others address development needs (e.g., broader public health and healthcare capacity building, disease surveillance, laboratory biosafety, bioeconomy). While these do not align directly with biological weapons nonproliferation needs, they certainly benefit the treaty and, therefore, cannot be disregarded.

The standard for implementing Article X likely remains one of the biggest questions facing the BWC, including the scope and volume of ICA activities states parties are obligated to support. The principal contention is whether they are obligated to provide some or any support or to meet states parties’ needs or requests. Similarly, conflict remains between an expansive Article X model, including broader capacity-building efforts or international transfers for economic benefit, and prioritizing limited resources for deliberate threats and nonproliferation. The scope of activities states parties are permitted to undertake is also at issue, particularly considering calls to channel ICA through a BWC-specific mechanism and concerns about associated barriers to existing ICA efforts. Importantly, decisions regarding the scope of Article X obligations should not limit ICA more broadly, including activities implemented outside the BWC. To develop an effective ICA mechanism—or make progress toward strengthening Article X—states parties must agree on the scope and standard for implementation.

A narrower focus could prioritize BWC-specific needs and capacities for mitigating deliberate biological threats, knowing that strengthening these capacities would subsequently benefit traditional public health and healthcare without explicitly including natural and accidental threats under the BWC. A narrower focus aims not to limit the scope of ICA activities, but rather to prevent Article X from becoming too difficult to implement and assess, as well as mitigate duplication of efforts with other fora (Littlewood, 2018). Conversely, an expansive approach—or linking the standard for Article X implementation to states parties’ needs or requests—could promote broader development benefit under the BWC, particularly to establish critical health and public health capacities in LMICs and the Global South (Mohammadi, 2023); however, implementation could be problematic in the BWC context. First, broadening BWC-supported ICA would necessitate increased resources, which are finite, both for the BWC and states parties. Many capacity-building or development activities also fall under the purview of other international treaties or organizations, particularly those dealing more directly with human and animal health, increasing the risk of duplicative efforts. By focusing on deliberate biological threats, states parties could more easily deconflict ICA activities and make efficient use of BWC resources. Binding Article X compliance to states parties’ requests could make compliance difficult or perhaps impossible. In the extreme case, for example, if any state party had outstanding needs or requests, then all states parties would be in noncompliance, an impractical standard. A focused and tangible scope and standard are critical not only to facilitate Article X implementation, but also to allow future progress toward meaningful verification or compliance assessment.

ICA Resources

There is broad agreement that states parties could always do more in terms of ICA, but resource limitations remain a major barrier, both at the national level and within the BWC. Other international treaties, such as the CWC and NPT, have dedicated ICA programs and bodies, with dedicated funding using both voluntary and assessed contributions. Importantly, they are also supported by treaty organizations (i.e., OPCW, IAEA) with dedicated funding mechanisms and implementation capacity. In contrast, the BWC does not have its own funding (or organization) to support ICA activities. If states parties desire to incorporate those components into a future ICA mechanism’s role, they will need to increase assessed and/or voluntary contributions. Governments face countless competing demands for finite resources, so they can only support a finite volume of ICA. These limitations necessitate that the BWC operate efficiently with its resources. The BWC cannot satisfy the global ICA demand on its own; therefore, states parties must both prioritize what falls under the BWC and identify alternative sources of support. Many ICA activities that address various aspects of biosecurity are supported through various IO/IGOs, civil society and private sector organizations, and state governments. Deconflicting those efforts could reserve BWC resources for BWC-specific needs that are not addressed elsewhere, such as those more directly related to biological weapons nonproliferation. IO/IGOs and civil society could also contribute directly to BWC ICA activities (e.g., working capital fund contributions), which has been successful in other fora (Mohammed, 2023; Moodie, 2023).

States parties should consider opportunities to participate in ICA activities that rely less on financial or material resources. Options include sharing information, lessons, and best practices or in-kind support, such as scientific exchange, training and education programs, or laboratory twinning. There are numerous recent examples, including regional workshops to strengthen CBMs or national implementation or to support treaty universalization, but this principle can apply broadly across other treaty obligations and capacities (National Workshop, 2025; Regional Workshop 1, 2024; Regional Workshop 2, 2024; Regional Workshop 2, n.d.). These kinds of activities require resources, but much less than developing, transferring, or implementing capacities, materials, or programs. By leveraging experience and expertise—including from civil society and IO/IGOs—states parties can support ICA activities using fewer resources. Expanding the donor pool to include states parties without surplus material or financial resources or proficiency in advanced biological capabilities also facilitates regional collaboration and South-South partnerships to strengthen BWC implementation.

Article X Database & Reports

The Article X database provides a platform to host ICA requests and offers, but improvements are necessary to realize its potential in facilitating ICA, including a broader agreement on its role. Issues such as mismatches between offer and request content (e.g., nonproliferation/security versus capacity building/technology transfer), states parties’ hesitancy to post requests, the degree of detail in offers and requests, and the absence of active matchmaking limit the database’s ability to serve its intended purpose. The inability to monitor database effectiveness also remains a gap. There is some indication, however, that it is more effective at facilitating partnerships than available data indicate, as partnerships are formed by going around, not through, the database. Making functional changes to the database necessitates states parties to agree on its underlying purpose—e.g., active matchmaking versus clearinghouse—and tailor its features and functions to meet that aim. Beyond formal efforts to update or operationalize the database, there are also informal opportunities for improvement, including expanding the number and scope of offers and requests to improve the likelihood of successful matches, providing sufficient detail to ensure state parties understand what is offered or needed, and documenting successful partnerships, whether made directly via the database or via informal pathways. States parties have an opportunity to make necessary upgrades to the Article X database, whether independently or as part of a future ICA mechanism, and the limitations described here offer numerous opportunities to strengthen the functionality and use of the only existing BWC platform designed to facilitate ICA.

Article X reports do not appear to meaningfully raise awareness of ICA activities or alleviate concerns regarding Article X compliance. Low participation severely limits available data, and they are referenced infrequently. Additionally, the information provided may be perceived as more self-serving for the submitting state party than informative for others. Importantly, however, transparency may provide some value in “pre-informing” or “pre-bunking” false narratives the modern era of disinformation, mitigating the risk or impact of efforts to misrepresent or manipulate legitimate ICA for deceitful purposes (Mitigating Disinformation, 2024; Sundelson, et al., 2025; United Kingdom, 2023; United States 2022b). Any effort to strengthen Article X reports would likely necessitate expanded participation and analysis, but while any increase would be a proportionately large change, only a major improvement would yield a meaningful volume of either. Article X reports provide value through sharing information regarding ICA activities, but there are likely better targets for strengthening Article X.

Export Controls & Sanctions

Broad support exists for export controls, to both mitigate proliferation risks and facilitate ICA. We know that some states parties actively oppose existing export control regimes, alongside sanctions, embargoes, and other mechanisms that have similar effects on international transfers. But while vocal, they do not necessarily represent the position of NAM Group states parties or LMICs—and may overshadow their peers’ primary concerns about Article X (Lennane, 2023). In contrast, if the Australia Group is the de facto global standard, that ensures everyone has the same expectations, enabling governments to implement appropriate protections and build confidence in their ability to mitigate proliferation risks to streamline international transfers. These tools may be negotiated multilaterally (although not always), but implementation occurs at the national level, placing national sovereignty at the core of the debate around these mechanisms. States parties argue, on one hand, their right to implement protective measures and, on the other, their right to access materials, products, and technologies, including to protect the health of their citizens.

We know there are examples of practical barriers and denied transfers, even with humanitarian and other exemptions (Lennane, 2023), a major point of contention for states parties arguing that such mechanisms hinder health, scientific, and economic pursuits (Cuba, 2022; Iran, 2022; Iran & Cuba, 2024; Venezuela, 2022). These instances appear to represent the exception, however, rather than the rule. Some donor states parties report low rates of transfer denials, as well as a low proportion of exports even subject to licensing (United Kingdom, 2023; United States, 2024). While these reports do not fully account for practical barriers, they suggest that transfer denials may represent a small proportion of total exports. Conversely, these examples may represent a substantial proportion of imports from LMICs or critical technologies or materiel for individual institutions. Additionally, barriers to transparency regarding transfer denials drive perceptions of inconsistent, selective implementation. Regardless, any barrier to international transfers for legitimate purposes can hinder efforts to strengthen healthcare and public health capacity or unnecessarily limit the use of biology. These barriers may not be a direct result of export controls or sanctions, but rather, their interpretation and implementation, including by state governments, civil society, and the private sector (Lennane, 2023).

Mitigating health and security risks from deliberate biological threats frees humanity to push back the boundaries of biology and leverage these capabilities for a variety of beneficial purposes, so states parties have a vested interest in determining and alleviating the underlying issues preventing legitimate transfers. Additional data and analysis are needed to more fully characterize these barriers’ impacts, and states parties should find ways to better understand these disruptions. Some states parties, including the NAM Group (Azerbaijan, 2022a), have called for establishing a BWC-specific adjudication process, but allowing an ICA mechanism or other BWC body to rule on transfer denials, or export controls and sanctions more broadly, could risk infringing on state sovereignty or weakening security protections. States parties argue their right and obligation to implement national measures to protect against the proliferation of biology for prohibited purposes, and taking associated decisions out of their hands would be a non-starter for many governments. Alternatively, Article V already provides a consultation mechanism for issues related to treaty implementation, and formal or informal consultations—bilateral or multilateral—could provide a forum to address these concerns (Revill & Garzón Maceda, 2023). States parties could also elect to study these barriers as part of regular BWC meetings or as a function of an ICA mechanism (Lennane, 2023). Focusing on identifying and remediating systemic barriers could provide a more comprehensive and sustainable solution to broadening access to biology for peaceful purposes, rather than adjudicating specific transfer denials.

IO/IGOs, Civil Society & Private Sector

While Article X obligations apply explicitly to states parties, IO/IGOs and civil society, including private sector business and industry, account for a considerable volume of ICA, including as implementers for state-sponsored activities. Considering limitations on resources, capacities, and capabilities facing states parties, looking beyond state governments can broaden the base of technical and material support for ICA activities. Entities outside the BWC offer an extensive scope of ICA opportunities, such as capacity building, scientific exchange, and training by IO/IGOs or academic institutions; equipment or technology transfer by private sector businesses; and direct support for national implementation (Canada & Philippines, 2023; Implementing the Biological Weapons Convention, n.d.). Other fora have demonstrated the ability to accept civil society contributions to support ICA activities. In a contentious geopolitical environment, state-state collaboration can be difficult, and civil society organizations may be better positioned to circumvent those barriers. IO/IGOs, civil society, and private sector business and industry do not have formal seats at the BWC table, but they offer critical capacities to promote long-term sustainability for ICA activities. And while Working Group and Review Conference decisions only apply directly to states parties, opportunities exist outside the formal umbrella of the treaty to strengthen ICA and Article X, including through a future mechanism.

Article X Mechanism

As an explicit priority in the Working Group mandate, establishing an ICA mechanism should remain a principal goal leading up to the Tenth Review Conference. States parties have already agreed, in principle, to establish such a mechanism, but they still need to achieve consensus on the mechanism’s format, roles and responsibilities, and resources. The Working Group Friends of the Chair have presented several iterations of a proposed model, based on input from existing proposals as well as ongoing deliberations, to illustrate areas of convergence, and the Working Group Chair has indicated that formal draft proposals will be introduced in 2025 to facilitate more concrete negotiations ahead of the Tenth Review Conference (Canada & Philippines, 2024a; Canada & Philippines, 2024b; U.N. Institute for Disarmament Research, 2025).

Benefiting from years of prior debate, the ICA and science and technology review mechanisms likely represent the most fully developed concepts under consideration and the best opportunities for concrete progress. States parties have an opportunity for a major victory, and there have already been formal efforts to move forward with these mechanisms, including the Working Group Chair’s proposal to hold a Special Conference to establish both. This garnered encouraging support across numerous states parties, but they have not yet negotiated a consensus (Brazil, 2024; Guthrie, 2024, December 16). Establishing these mechanisms together would be an important and, crucially, concrete step forward for the BWC—an achievement befitting the treaty’s 50th anniversary. Beyond the direct benefits to strengthening the treaty, such an agreement would build positive momentum and enable states parties to shift limited time, attention, and resources to other priority issues, including verification and compliance assessment. While demands persist for a comprehensive package to address all BWC obligations simultaneously, perhaps success in implementing these priority mechanisms—possibly in conjunction with commitment to hold formal negotiations on other topics—could garner the support needed to achieve consensus.

Proposed ICA Framework

In an effort to help states parties and other stakeholders conceptualize the complex relationships between the scope of ICA activities, resources to support those activities, and potential roles and responsibilities of an ICA mechanism, we developed an ICA pillar framework (

Table 3), drawing on existing proposals and fortified with analysis from this study. These critical components are inextricably interwoven, and they cannot be addressed independently. We organized the framework into 3 pillars, each with 3 categories: ICA activities, ICA mechanism functions, and ICA resources. This framework presents one option to help BWC states parties balance competing demands for action on Article X and ICA, address their needs across the full spectrum of biological capabilities and threats, and align ICA activities with appropriate sources of coordination and support. We intend this model to stimulate thinking among states parties and other stakeholders as they look ahead to the final years of the Working Group and to the Tenth Review Conference. It aims to answer calls for mandatory participation in Article X activities, while respecting states parties’ sovereignty and autonomy to identify and conduct appropriate voluntary activities and making efficient use of limited resources. Importantly, we intend this framework to align types of activities with appropriate resources and ICA mechanism functions. It does not deter or discourage states parties from continuing current activities nor limit the scope of states parties’ obligations under Article X.

Pillar 1

Pillar 1 represents ICA activities most closely aligned with the core purpose of the BWC, as a disarmament and nonproliferation treaty, such as resilience against deliberate biological threats, BWC national implementation, laboratory biosecurity, and treaty universalization. Obviously, there is considerable overlap between the capacities needed to combat natural, accidental, and deliberate threats, but rather than taking an expansive approach that brings natural and accidental threats under the BWC, this framework proposes the opposite. Primarily strengthening deliberate threat preparedness and response capacities makes efficient use of BWC resources for BWC-specific needs, while providing secondary benefits for natural and accidental threats. Pillar 1 would comprise activities that all states parties agree should be supported directly through the BWC, subject to regular review to meet evolving needs.

A future ICA mechanism could directly oversee implementation for Pillar 1 activities, including reviewing and authorizing proposals. The mechanism would allocate resources from a pool of dedicated funding to support activities within the scope designated by states parties. Working fund resources could come from a variety of sources, including voluntary contributions, but we see an opportunity to utilize assessed contributions to implement a select subset of ICA activities. In this model, assessed contributions would be necessary to support the ICA mechanism itself (e.g., meetings, administrative functions), but they could also support activities implemented by the ICA mechanism, providing critical stability and predictability and facilitating the mechanism’s longer-term planning. States parties, IO/IGOs, and civil society could also supplement the Pillar 1 working fund with voluntary contributions.

Because Pillar 1 includes only activities agreed by consensus, states parties should have no need to restrict the use of assessed contributions within that scope. This would meet demands for mandatory, contributions to ICA activities—unrestricted within the scope of core BWC needs—without requiring states parties to fund activities they deem inappropriate. It would also effectively establish a minimum standard for Article X participation. Relying solely on voluntary contributions—or those that could be restricted or earmarked for specific purposes—would not meaningfully differ from the existing model, unless states parties were sufficiently motivated to funnel ICA resources through the mechanism. Knowing that some states parties may have difficulty paying their assessed contributions, Pillar 1 could include exceptions for states parties receiving assistance to redirect those funds to support their ICA activities, enabling those in the greatest need to allocate their resources toward strengthening national implementation or relevant capacity-building efforts.

Pillar 2

Pillar 2 addresses natural and accidental health threats, for which deliberate event benefits would be secondary, including many current ICA activities. Potential targets include broader public health and healthcare capacity building, such as strengthening disease surveillance, laboratory capacity, and laboratory biosafety, as well as medical countermeasures (MCM) research, development, and production. There is no clear delineation between capacities for natural, accidental, and deliberate biological threats, but in this framework, we categorize those principally addressing deliberate threats under Pillar 1 and those more generally addressing natural and accidental threats under Pillar 2.