Submitted:

16 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Obtaining H. Contortus L3

2.2. Sucrose Washing and Recovery of H. Contortus L3

2.3. Exsheathment and Migration of H. Contortus L3

2.4. Preservation of H. Contortus L3

2.5. Collection of H. Contortus Adult Males and Females

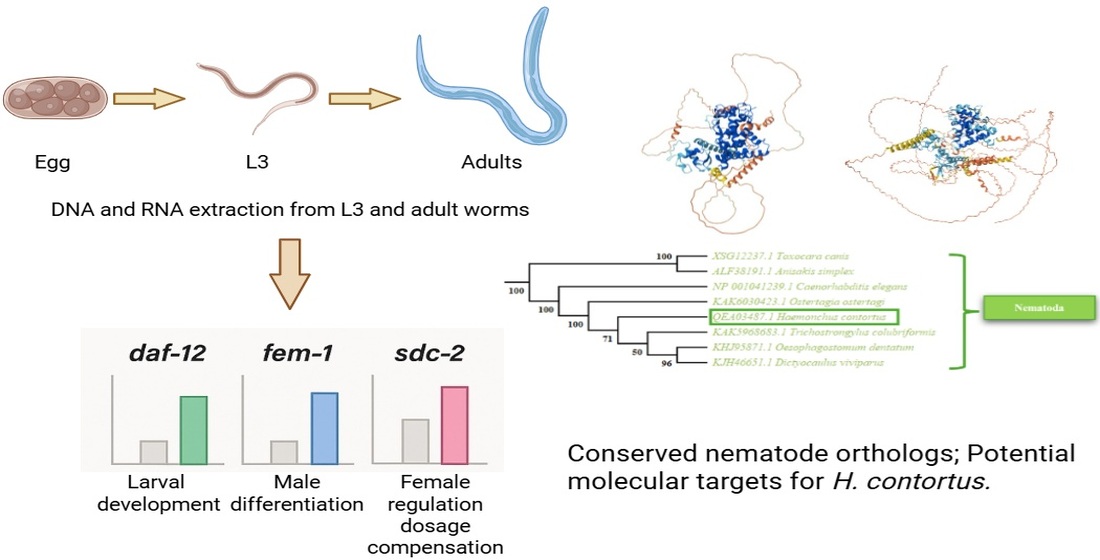

2.6. Identification of Genes Associated with Sexual Differentiation in C. elegans

2.7. Identification of Gene Sequences Related to Sexual Differentiation in the H. contortus Genome

2.8. Primer Design for Selected Gene Sequences

2.9. Genomic DNA Extraction

2.10. RNA Extraction

2.11. PCR

2.12. RT-PCR

2.13. Statycal Analysis

2.14. Modeling of the daf-12, fem-1, and sdc-2 Gene Structures

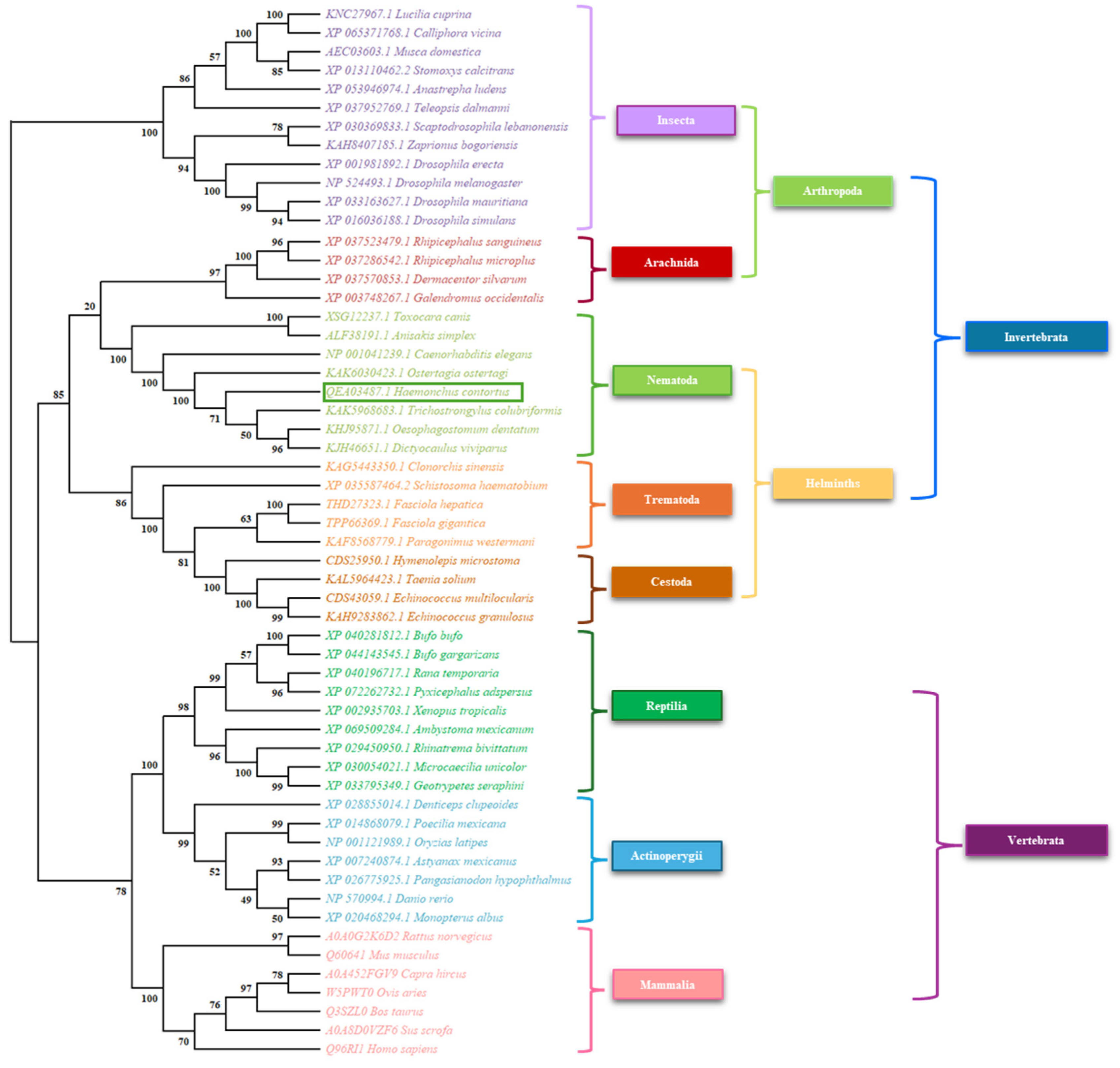

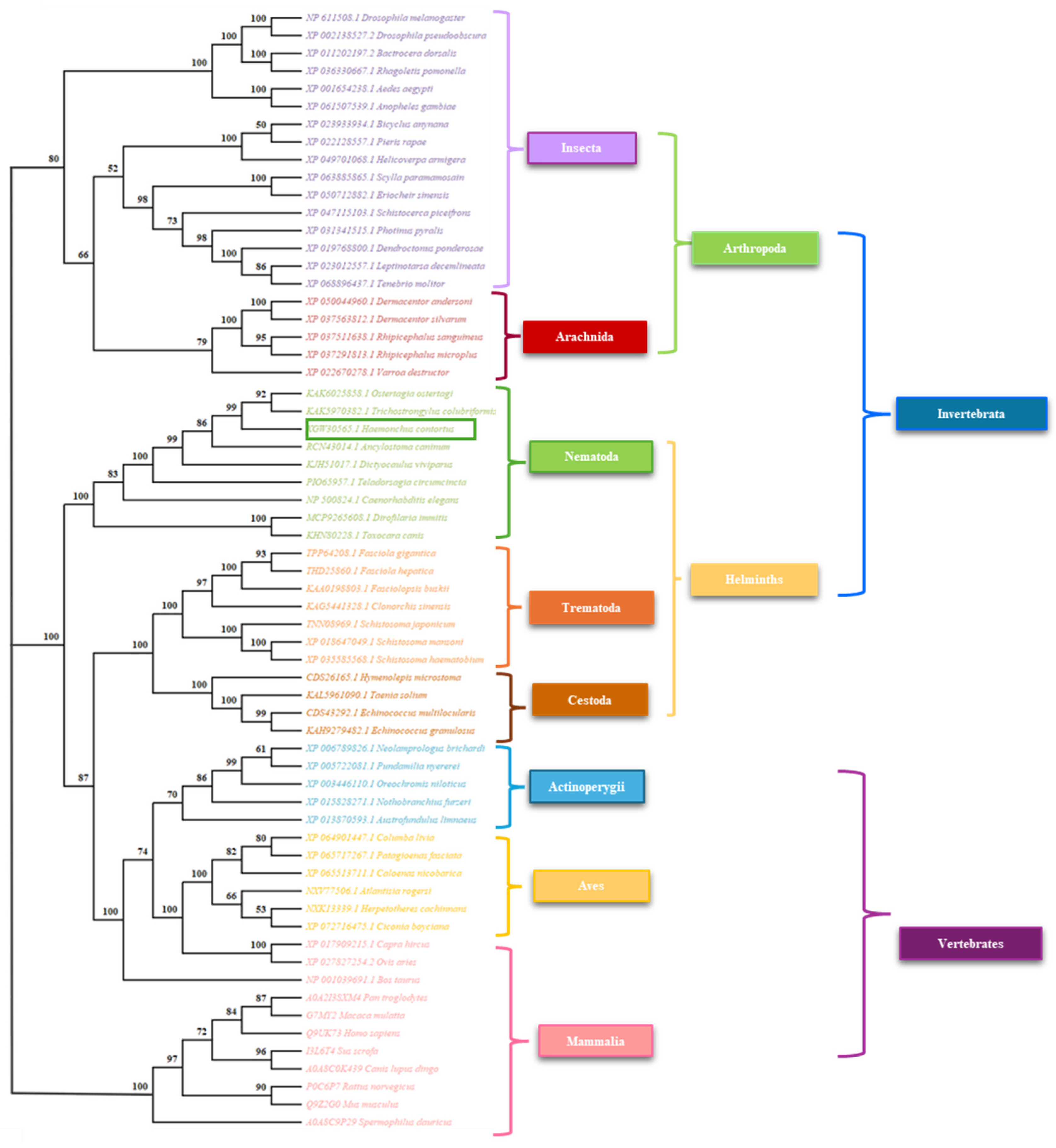

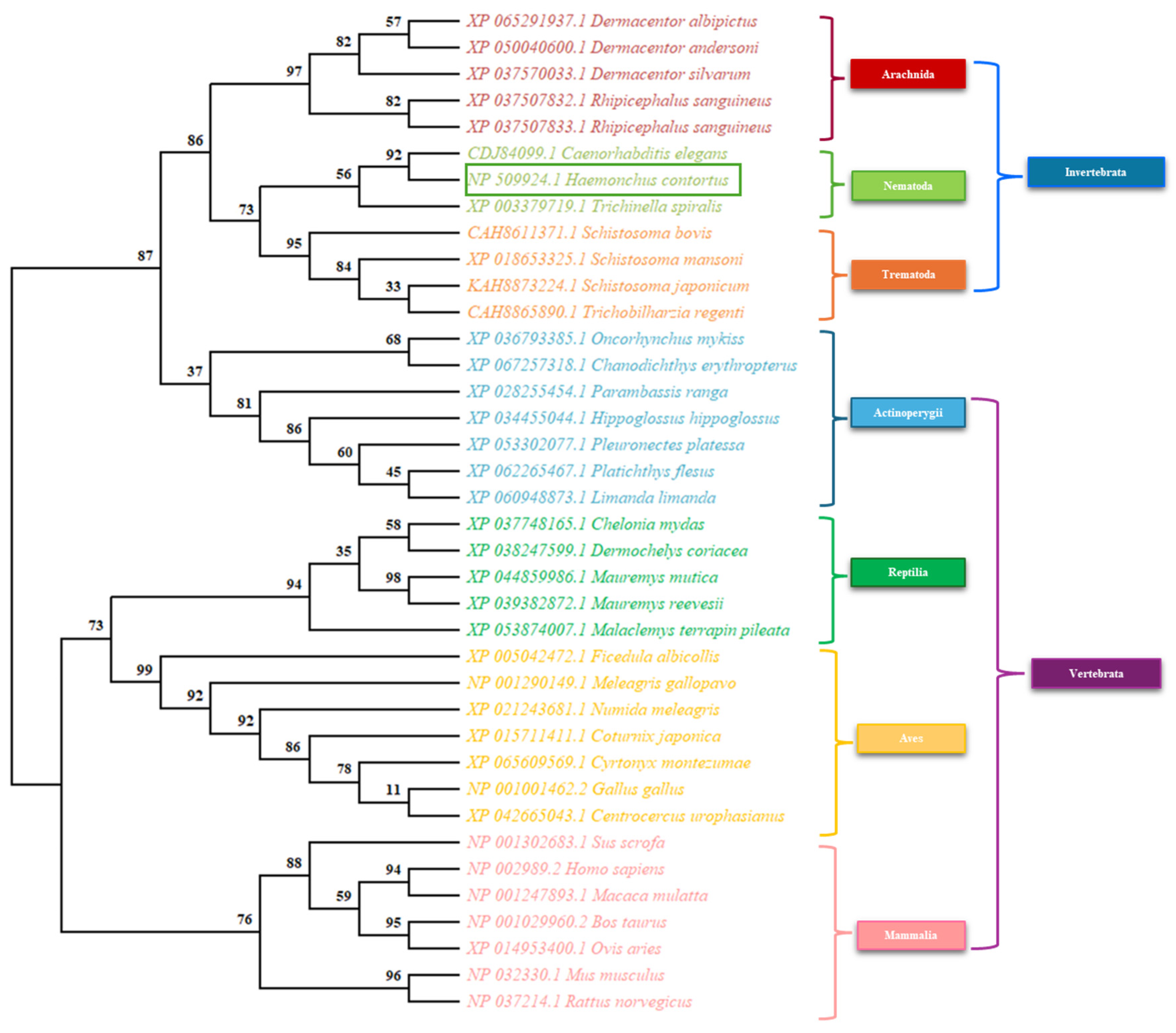

2.15. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

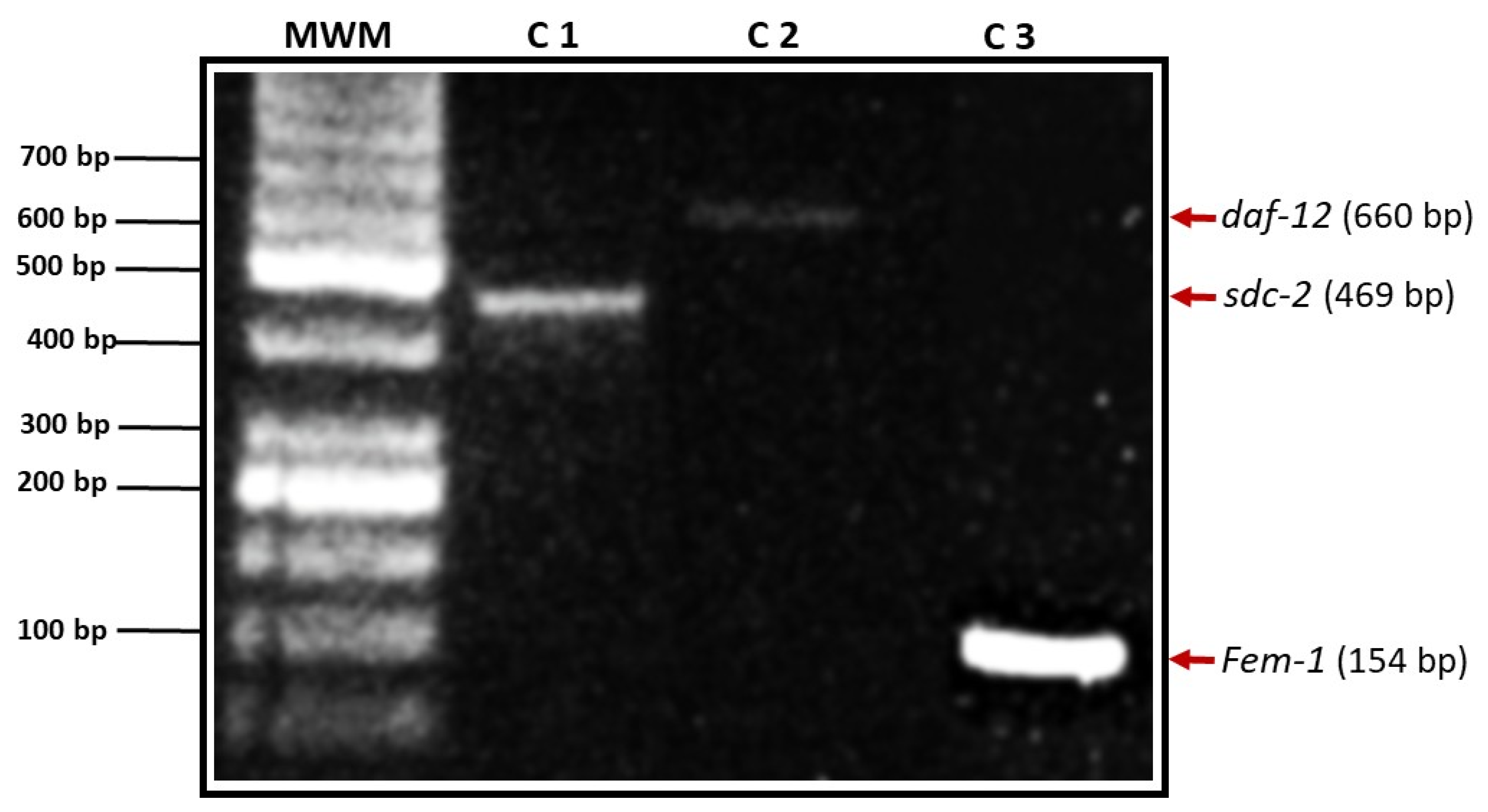

3.1. Determination of the Presence of Genes Related to Sexual Differentiation in the H. contortus Genome

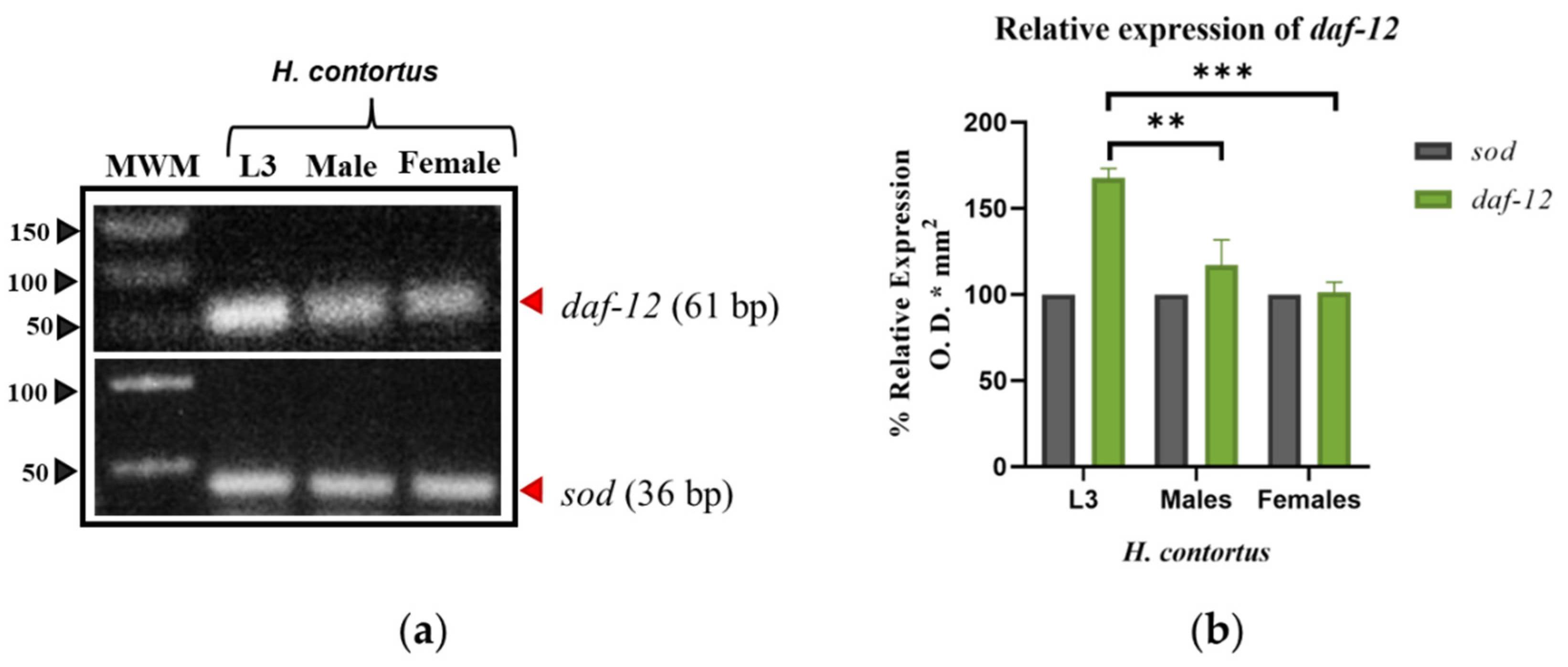

3.1.1. daf-12

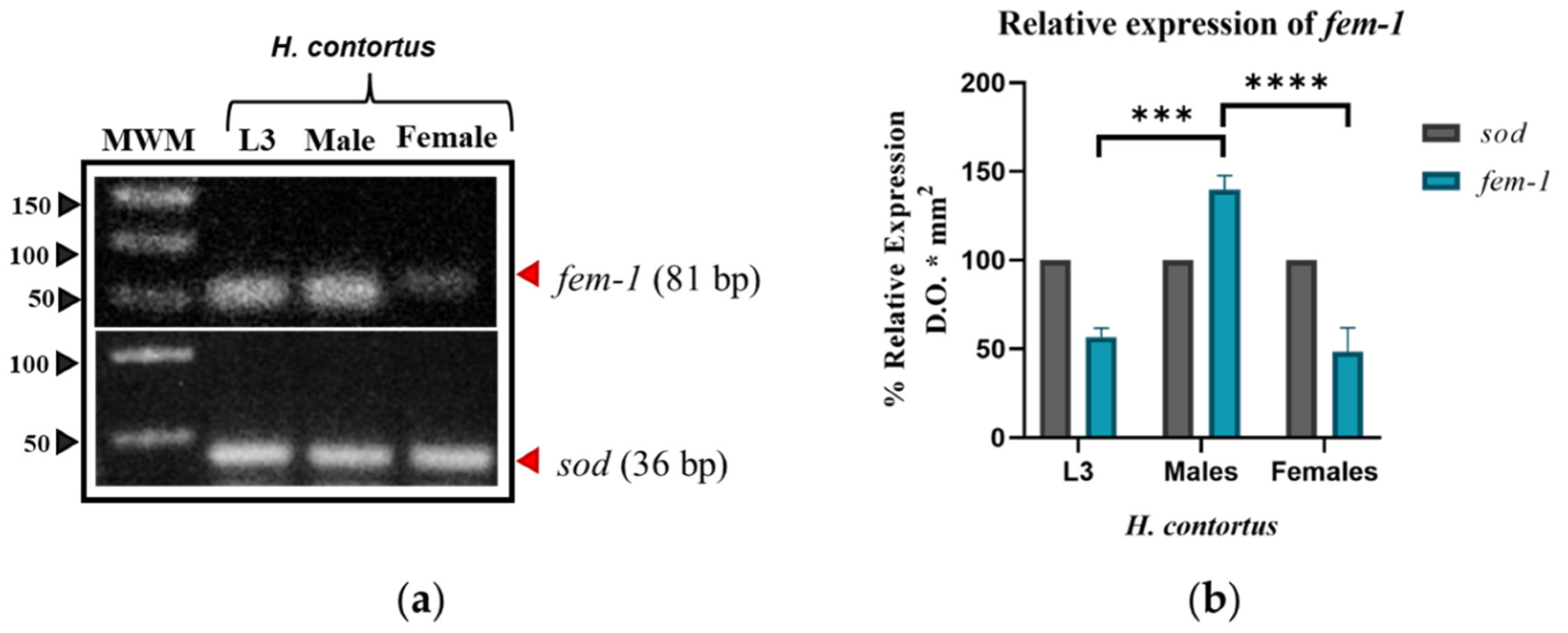

3.1.2. fem-1

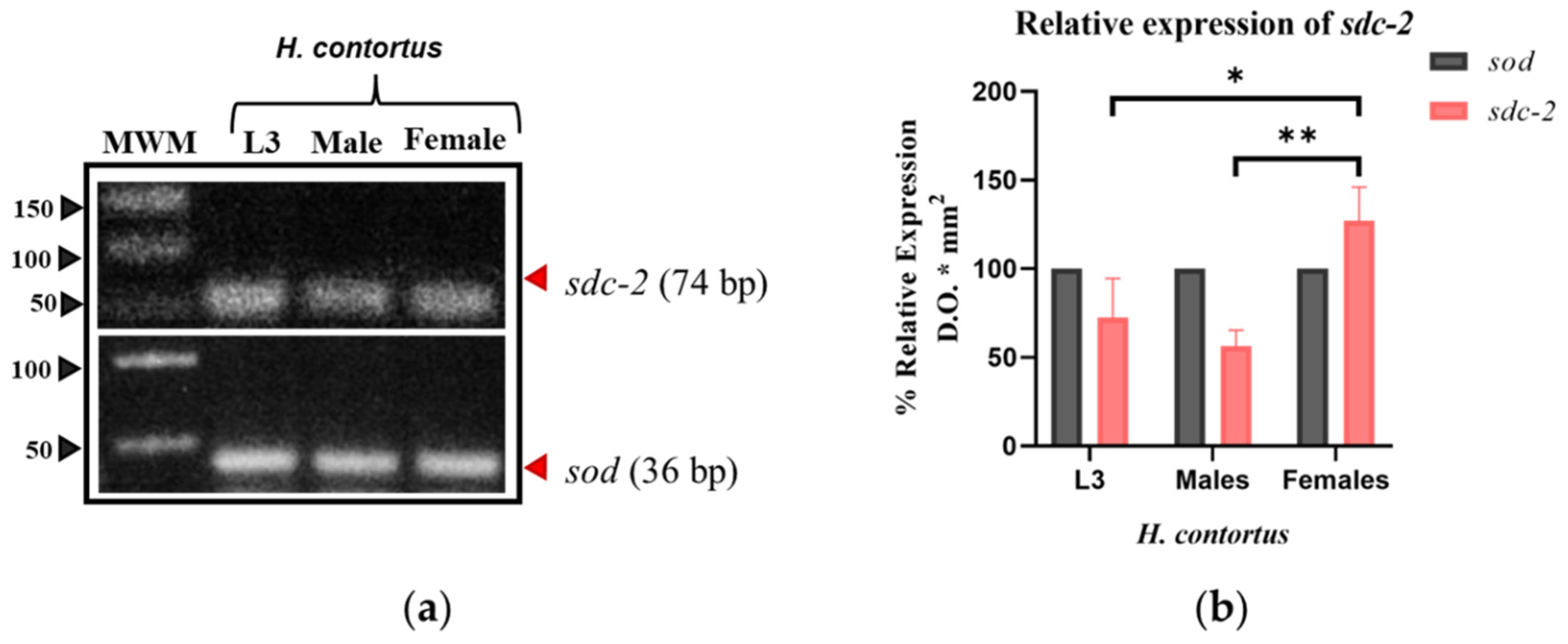

3.1.3. sdc-2

3.2. Bioinformatic Analysis

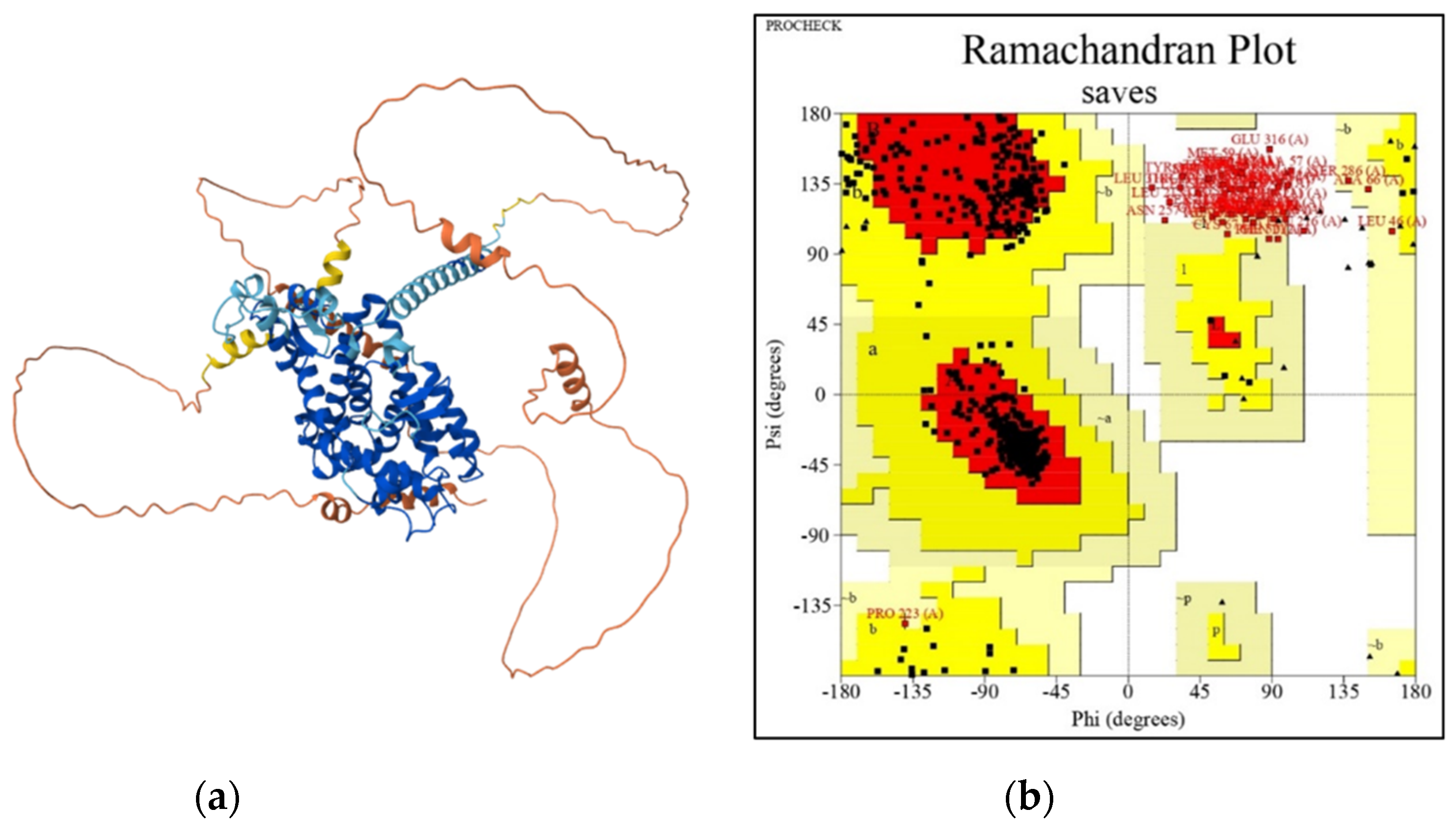

3.2.1. 3D Modeling of daf-12

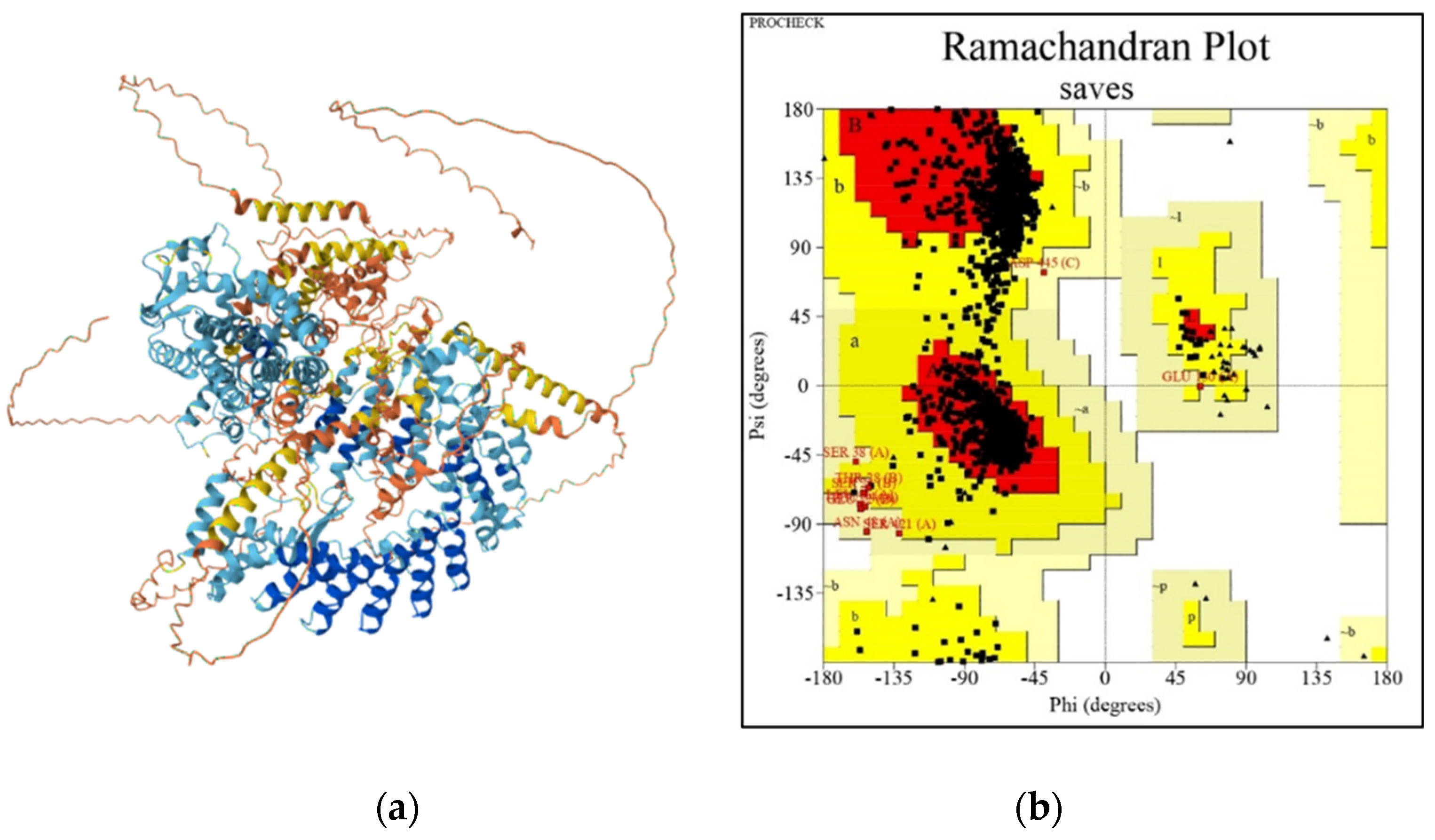

3.2.2. 3D Modeling of fem-1

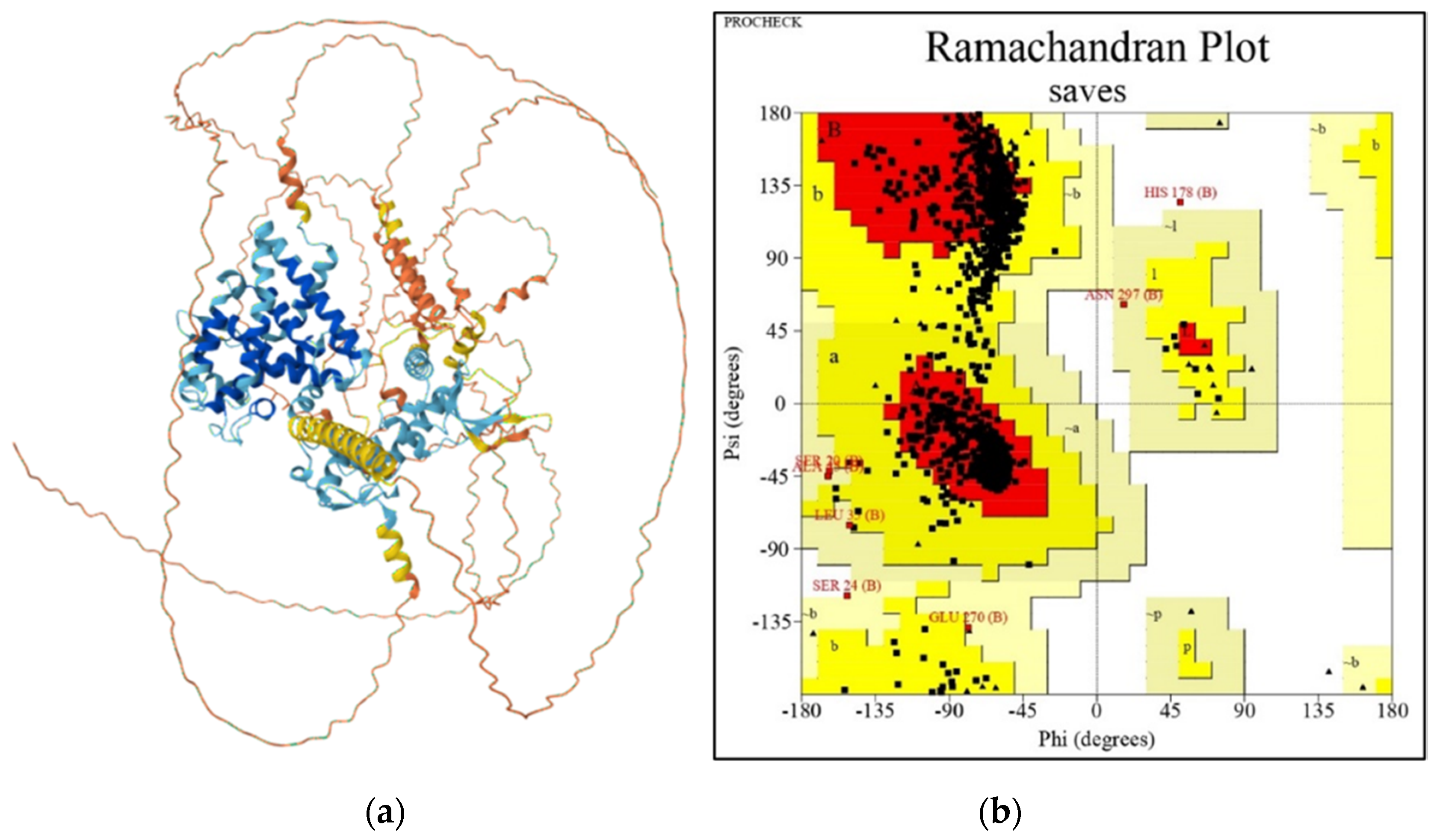

3.2.3. 3D Modeling of sdc-2

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| gDNA | Genomic DNA |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| BLASTn | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool nucleotide |

| BLASTp | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool protein |

| BS | Bootstrap |

| DCC | Dosage Compensation Complex |

| daf-12 | Dauer formation 12 |

| DBD | DNA-Binding Domain |

| fem-1 | Feminization-1 |

| GSD | Genetic Sex Determination |

| L3 | Larval stage 3 |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| sdc-1 | Sex Determination and Dosage Compensation-1 |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| Tm | Melting Temperature |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Accession Data of the Sequences Used for the Phylogenetic Analysis of DAF-12

| Accession number | Species | Protein | Data base |

| XP 0539946974.1 | Anastrepha ludens | Nuclear hormone receptor HR96 | NCBI |

| NP 524493.1 | Drosophila melanogaster | Hormone receptor-like in 96 | NCBI |

| XP 037952769.1 | Teleopsis dalmanni | Nuclear hormone receptor HR96-like | NCBI |

| XP 030369834.1 | Scaptodrosophila lebanonensis | Nuclear hormone receptor HR96 isoform X1 | NCBI |

| KAH8407185.1 | Zaprionus bogoriensis | Nuclear hormone receptor HR96 isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 013110462.2 | Stomoxys calcitrans | Nuclear hormone receptor HR96 | NCBI |

| AEC03603.1 | Musca domestica | Nuclear receptor HR96 | NCBI |

| XP 065371768.1 | Calliphora vicina | Nuclear hormone receptor HR96 | NCBI |

| KNC27967.1 | Lucilia cuprina | Nuclear hormone receptor HR96 | NCBI |

| XP 001981892.1 | Drosophila erecta | Nuclear hormone receptor HR96 | NCBI |

| XP 016036188.1 | Drosophila simulans | Nuclear hormone receptor HR96 | NCBI |

| XP 033163627.1 | Drosophila mauritiana | Nuclear hormone receptor HR96 | NCBI |

| XP 037570853.1 | Dermacentor silvarum | Vitamin D3 receptor | NCBI |

| XP 037523479.1 | Rhipicephalus sanguineus | Vitamin D3 receptor isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 037286542.1 | Rhipicephalus microplus | Vitamin D3 receptor-like | NCBI |

| XP 003748267.1 | Galendromus occidentalis | Vitamin D3 receptor | NCBI |

| KAK5968683.1 | Trichostrongylus colubriformis | Nuclear receptor subfamily 6 group A member 1 | NCBI |

| XSG12237.1 | Toxocara canis | Nuclear hormone receptor DAF-12, partial | NCBI |

| ALF38191.1 | Anisakis simplex | Nuclear hormone receptor, partial | NCBI |

| KHJ95871.1 | Oesophagostomum dentatum | Ligand-binding domain of nuclear hormone receptor, partial | NCBI |

| NP 001041239.1 | Caenorhabditis elegans | Nuclear hormone receptor family member daf-12 | NCBI |

| KJH46651.1 | Dictyocaulus viviparus | Zinc finger, C4 type | NCBI |

| KAK6030423.1 | Ostertagia ostertagi | Zinc finger, C4 type | NCBI |

| QEA03487.1 | Haemonchus contortus | Nuclear hormone receptor DAF-12 | NCBI |

| KAG5443350.1 | Clonorchis sinensis | Nuclear hormone receptor member daf-12 | NCBI |

| XP 035587464.2 | Schistosoma haematobium | Nuclear hormone receptor, partial | NCBI |

| TPP66369.1 | Fasciola gigantica | Nuclear hormone receptor HR96 | NCBI |

| THD27323.1 | Fasciola hepatica | Nuclear hormone receptor HR96 | NCBI |

| KAF8568779.1 | Paragonimus westermani | Nuclear hormone receptor, partial | NCBI |

| KAH9283862.1 | Echinococcus granulosus | Nuclear hormone receptor family member daf-12 | NCBI |

| KAL5964423.1 | Taenia solium | Nuclear hormone receptor family member daf-12 | NCBI |

| CDS25950.1 | Hymenolepis microstoma | Nuclear hormone receptor HR96 | NCBI |

| CDS43059.1 | Echinococcus multilocularis | Nuclear hormone receptor HR96 | NCBI |

| XP 040281812.1 | Bufo bufo | Vitamin D3 receptor isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 040196717.1 | Rana temporaria | Vitamin D3 receptor isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 002935703.1 | Xenopus tropicalis | Vitamin D3 receptor | NCBI |

| XP 044143545.1 | Bufo gargarizans | Vitamin D3 receptor | NCBI |

| XP 033795349.1 | Geotrypetes seraphini | Vitamin D3 receptor | NCBI |

| XP 069509284.1 | Ambystoma mexicanum | Vitamin D3 receptor isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 072262732.1 | Pyxicephalus adspersus | Vitamin D3 receptor | NCBI |

| XP 030054021.1 | Microcaecilia unicolor | Vitamin D3 receptor | NCBI |

| XP 029450950.1 | Rhinatrema bivittatum | Vitamin D3 receptor isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 007240874.1 | Astyanax mexicanus | Vitamin D3 receptor A | NCBI |

| XP 026775925.1 | Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | Vitamin D3 receptor A | NCBI |

| NP 570994.1 | Danio rerio | Vitamin D3 receptor A | NCBI |

| XP 028855014.1 | Denticeps clupeoides | Vitamin D3 receptor | NCBI |

| XP 014868079.1 | Poecilia mexicana | Vitamin D3 receptor | NCBI |

| XP 020468294.1 | Monopterus albus | Vitamin D3 receptor | NCBI |

| NP 001121989.1 | Oryzias latipes | Vitamin D3 receptor | NCBI |

| W5PWT0 | Ovis aries | Bile acid receptor | Swiss-Prot |

| Q96RI1 | Homo sapiens | Bile acid receptor | Swiss-Prot |

| Q60641 | Mus musculus | Bile acid receptor | Swiss-Prot |

| Q3SZL0 | Bos taurus | Bile acid receptor | Swiss-Prot |

| A0A8D0VZF6 | Sus scrofa | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group H member 4 | Swiss-Prot |

| A0A452FGV9 | Capra hircus | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group H member 4 | Swiss-Prot |

| A0A0G2K6D2 | Rattus norvegicus | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group H, member 4 | Swiss-Prot |

Appendix A.2. Accession Data of the Sequences Used for the Phylogenetic Analysis of FEM-1

| Accession number | Species | Protein | Data base |

| NP 611508.1 | Drosophila melanogaster | Fem-1, isoform A | NCBI |

| XP 047115103.1 | Schistocerca piceifrons | Protein fem-1 homolog B | NCBI |

| XP 063885865.1 | Scylla paramamosain | Protein fem-1 homolog B-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 001654238.1 | Aedes aegypti | Protein fem-1 homolog B-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 023933934.1 | Bicyclus anynana | Protein fem-1 homolog B-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 011202197.2 | Bactrocera dorsalis | Protein fem-1 homolog B-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 002138527.2 | Drosophila pseudoobscura | Protein fem-1 homolog B-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 050712882.1 | Eriocheir sinensis | Protein fem-1 homolog B-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 036330667.1 | Rhagoletis pomonella | Protein fem-1 homolog B-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 031341515.1 | Photinus pyralis | Protein fem-1 homolog B | NCBI |

| XP 061507539.1 | Anopheles gambiae | Protein fem-1 homolog B | NCBI |

| XP 022128557.1 | Pieris rapae | Protein fem-1 homolog B-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 019768800.1 | Dendroctonus ponderosae | Protein fem-1 homolog B-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 023012557.1 | Leptinotarsa decemlineata | Protein fem-1 homolog B-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 049701068.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | Protein fem-1 homolog B-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 068896437.1 | Tenebrio molitor | Protein fem-1 homolog B-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 050044960.1 | Dermacentor andersoni | Protein fem-1 homolog B | NCBI |

| XP 037563812.1 | Dermacentor silvarum | Protein fem-1 homolog B | NCBI |

| XP 037511638.1 | Rhipicephalus sanguineus | Protein fem-1 homolog B | NCBI |

| XP 037291813.1 | Rhipicephalus microplus | Protein fem-1 homolog B-like | NCBI |

| XP 022670278.1 | Varroa destructor | Protein fem-1 homolog B-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XGW30566.1 | Haemonchus contortus | Protein fem-1 homolog B | NCBI |

| KAK5970382.1 | Trichostrongylus colubriformis | Sex-determining protein fem-1 | NCBI |

| RCN43014.1 | Ancylostoma caninum | Ankyrin repeat protein | NCBI |

| KJH51017.1 | Dictyocaulus viviparus | Ankyrin repeat protein | NCBI |

| KAK6025858.1 | Ostertagia ostertagi | Ankyrin repeat protein | NCBI |

| KHN80228.1 | Toxocara canis | Sex-determining protein fem-1 | NCBI |

| PIO65957.1 | Teladorsagia circumcincta | Ankyrin repeat protein | NCBI |

| MCP9265608.1 | Dirofilaria immitis | Protein fem-1 | NCBI |

| NP 500824.1 | Caenorhabditis elegans | Sex-determining protein fem-1 | NCBI |

| THD25860.1 | Fasciola hepatica | Protein fem-1 | NCBI |

| KAA0198803.1 | Fasciolopsis buskii | Fem-1 A | NCBI |

| TPP64208.1 | Fasciola gigantica | Protein fem-1 | NCBI |

| KAG5441328.1 | Clonorchis sinensis | Protein fem-1 C | NCBI |

| TNN08969.1 | Schistosoma japonicum | Protein fem-1 | NCBI |

| XP 035585568.1 | Schistosoma haematobium | Protein fem-1 C | NCBI |

| XP 018647049.1 | Schistosoma mansoni | Sex-determining protein fem-1 | NCBI |

| KAH9279482.1 | Echinococcus granulosus | Protein fem-1 -like protein C | NCBI |

| CDS43292.1 | Echinococcus multilocularis | Sex-determining protein fem-1 | NCBI |

| KAL5961090.1 | Taenia solium | Sex-determining protein fem-1 | NCBI |

| CDS26165.1 | Hymenolepis microstoma | Sex-determining protein fem-1 | NCBI |

| XP 005722081.1 | Pundamilia nyererei | Protein fem-1 homolog C | NCBI |

| XP 003446110.1 | Oreochromis niloticus | Protein fem-1 homolog C | NCBI |

| XP 006789826.1 | Neolamprologus brichardi | Protein fem-1 homolog C | NCBI |

| XP 015828271.1 | Nothobranchius furzeri | Protein fem-1 homolog C | NCBI |

| XP 013870593.1 | Austrofundulus limnaeus | Protein fem-1 homolog C-like | NCBI |

| XP 064901447.1 | Columba livia | Protein fem-1 homolog C isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 065717267.1 | Patagioenas fasciata | Protein fem-1 homolog C | NCBI |

| XP 065513711.1 | Caloenas nicobarica | Protein fem-1 homolog C | NCBI |

| NXK13339.1 | Herpetotheres cachinnans | FEM1C protein | Swiss-Prot |

| XP 072716475.1 | Ciconia boyciana | Protein fem-1 homolog C | NCBI |

| NXV77506.1 | Atlantisia rogersi | FEM1C protein, partial | NCBI |

| XP 027827254.2 | Ovis aries | Protein fem-1 homolog C | NCBI |

| XP 017909215.1 | Capra hircus | Protein fem-1 homolog C isoform X1 | NCBI |

| P0C6P7 | Rattus norvegicus | Protein fem-1 homolog B | Swiss-Prot |

| A0A2I3SXM4 | Pan troglodytes | Fem-1 homolog B | Swiss-Prot |

| G7MY25_MACMU | Macaca mulatta | FEM1B | Swiss-Prot |

| I3L6T4 | Sus scrofa | Fem-1 homolog B | Swiss-Prot |

| A0A8C0K439 | Canis lupus dingo | Fem-1 homolog B | NCBI |

| A0A8C9P293_SPEDA | Spermophilus dauricus | Fem-1 homolog B | Swiss-Prot |

| NP 001039691.1 | Bos taurus | Protein fem-1 homolog A | NCBI |

| Q9Z2G0 | Mus musculus | Protein fem-1 homolog B | Swiss-Prot |

| Q9UK73 | Homo sapiens | Protein fem-1 homolog B | Swiss-Prot |

Appendix A.3. Accession Data of the Sequences Used for the Phylogenetic Analysis of SDC-2

| Accession number | Species | Protein | Data base |

| XP 050040600.1 | Dermacentor andersoni | Syndecan 3 | NCBI |

| XP 037507833.1 | Rhipicephalus sanguineus | Syndecan-like | NCBI |

| XP 037507832.1 | Rhipicephalus sanguineus | Syndecan | NCBI |

| XP 037570033.1 | Dermacentor silvarum | Syndecan-like | NCBI |

| XP 065291937.1 | Dermacentor albipictus | Syndecan-like | NCBI |

| CDJ84099.1 | Haemonchus contortus | CBN-SDC-2 protein | NCBI |

| NP 509924.1 | Caenorhabditis elegans | Sex determination and dosage compensation protein sdc-2 | NCBI |

| XP 003379719.1 | Trichinella spiralis | Syndecan-2 | NCBI |

| CAH8611371.1 | Schistosoma bovis | Syndecan | NCBI |

| KAH8873224.1 | Schistosoma japonicum | Syntenin-2 (Syndecan-binding protein 2) | NCBI |

| XP 018653325.1 | Schistosoma mansoni | Putative syntenin-2 (Syndecan-binding protein 2) | NCBI |

| CAH8865890.1 | Trichobilharzia regenti | Syndecan | NCBI |

| XP 062265467.1 | Platichthys flesus | Syndecan-2 | NCBI |

| XP 036793385.1 | Oncorhynchus mykiss | Syndecan-2 isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 067257318.1 | Chanodichthys erythropterus | Syndecan-2-A-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 053302077.1 | Pleuronectes platessa | Syndecan-2 | NCBI |

| XP 060948873.1 | Limanda limanda | Syndecan-2 | NCBI |

| XP 034455044.1 | Hippoglossus hippoglossus | Syndecan-2 | NCBI |

| XP 028255454.1 | Parambassis ranga | Syndecan-2-A-like | NCBI |

| XP 037748165.1 | Chelonia mydas | Syndecan-2-A-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| XP 038247599.1 | Dermochelys coriacea | Syndecan-2-A-like isoform X2 | NCBI |

| XP 044859986.1 | Mauremys mutica | Syndecan-2 | NCBI |

| XP 053874007.1 | Malaclemys terrapin pileata | Syndecan-2 | NCBI |

| XP 039382872.1 | Mauremys reevessi | Syndecan-2 | NCBI |

| NP 001001462.2 | Gallus gallus | Syndecan-2 precursor | NCBI |

| XP 015711411.1 | Coturnix japonica | Syndecan-2 | NCBI |

| XP 021243681.1 | Numida meleagris | Syndecan-2 | NCBI |

| NP 001290149.1 | Meleagris gallopavo | Syndecan-2 precursor | NCBI |

| XP 005042472.1 | Ficedula albicollis | Syndecan-2 | NCBI |

| XP 042665043.1 | Centrocercus urophasianus | Syndecan-2 | NCBI |

| XP 065609569.1 | Cyrtonyx montezumae | Syndecan-2 | NCBI |

| XP 014953400.1 | Ovis aries | Syndecan-2-A-like isoform X1 | NCBI |

| NP 001029960.2 | Bos taurus | Syndecan-2 precursor | NCBI |

| NP 032330.1 | Mus musculus | Syndecan-2 precursor | NCBI |

| NP 037214.1 | Rattus norvegicus | Syndecan-2 precursor | NCBI |

| NP 001247893.1 | Macaca mulatta | Syndecan-2 precursor | NCBI |

| NP 001302683.1 | Sus scrofa | Syndecan-2 precursor | NCBI |

| NP 002989.2 | Homo sapiens | Syndecan-2 precursor | NCBI |

References

- Arsenopoulos, K. V.; Fthenakis, G.C.; Katsarou, E.I.; Papadopoulos, E. Haemonchosis: A Challenging Parasitic Infection of Sheep and Goats. Anim. 2021, Vol. 11, Page 363 2021, 11, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Iqbal, Z.; Roohi, N. Ovine Haemonchosis: A Review. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 53, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, E.B.; Ellis, R.E. Turning Clustering Loops: Sex Determination in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, R111–R120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, D. Sex Determination, Insects. Encycl. Reprod. Vol. 1-6, Second Ed. 2018, 6, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forger, N.G.; de Vries, G.J. Cell Death and Sexual Differentiation of Behavior: Worms, Flies, and Mammals. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010, 20, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, J.M.; Grote, A.; Mattick, J.; Tracey, A.; Tsai, Y.C.; Chung, M.; Cotton, J.A.; Clark, T.A.; Geber, A.; Holroyd, N.; et al. Sex Chromosome Evolution in Parasitic Nematodes of Humans. Nat. Commun. 2020 111 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires-daSilva, A. Evolution of the Control of Sexual Identity in Nematodes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007, 18, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.; Pilgrim, D. Sex and the Single Worm: Sex Determination in the Nematode C. Elegans. Mech. Dev. 1999, 83, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinya, R.; Sun, S.; Dayi, M.; Tsai, I.J.; Miyama, A.; Chen, A.F.; Hasegawa, K.; Antoshechkin, I.; Kikuchi, T.; Sternberg, P.W. Possible Stochastic Sex Determination in Bursaphelenchus Nematodes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J.R.; Zarkower, D. Somatic Sexual Differentiation in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2008, 83, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, K.; Shi, Y.C.; Li, W.X.; Wang, J.; Cheng, B.J.; Li, T.L.; Li, H.; Jiang, N.; Liu, R. Testosterone Mediates Reproductive Toxicity in Caenorhabditis Elegans by Affecting Sex Determination in Germ Cells through Nhr-69/ Mpk-1/ Fog-1/ 3. Toxics 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.E. Sex Determination in Nematode Germ Cells. Sex Dev. 2022, 16, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redman, E.; Grillo, V.; Saunders, G.; Packard, E.; Jackson, F.; Berriman, M.; Gilleard, J.S. Genetics of Mating and Sex Determination in the Parasitic Nematode Haemonchus Contortus. Genetics 2008, 180, 1877–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallé, G.; Doyle, S.R.; Cortet, J.; Cabaret, J.; Berriman, M.; Holroyd, N.; Cotton, J.A. The Global Diversity of Haemonchus Contortus Is Shaped by Human Intervention and Climate. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, S.R.; Tracey, A.; Laing, R.; Holroyd, N.; Bartley, D.; Bazant, W.; Beasley, H.; Beech, R.; Britton, C.; Brooks, K.; et al. Genomic and Transcriptomic Variation Defines the Chromosome-Scale Assembly of Haemonchus Contortus, a Model Gastrointestinal Worm. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Young, N.D.; Wang, T.; Chang, B.C.H.; Song, J.; Gasser, R.B. Systems Biology of Haemonchus Contortus – Advancing Biotechnology for Parasitic Nematode Control. Biotechnol. Adv. 2025, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.; McKean, E.L.; Hawdon, J.M. Mini-Baermann Funnel, a Simple Device for Cleaning Nematode Infective Larvae. J. Parasitol. 2022, 108, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinzer, R.A.; McIntyre, J.R.; Britton, C.; Laing, R. The Parasitic Nematode Haemonchus Contortus Lacks Molybdenum Cofactor Synthesis, Leading to Sulphite Sensitivity and Lethality in Vitro. Int. J. Parasitol. 2025, 55, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerhong, R.; Tuersong, W.; Maimaiti, A.; Maimaitiyiming, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xuekelaiti, D.; Tuoheti, A.; Xin, L.; Abula, S. Genetic Diversity Analysis of Benzimidazole Resistance-Associated Genes in Haemonchus Contortus from Four Regions in Southern Xinjiang. Vet. Parasitol. 2025, 336, 110426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okino, C.H.; Bello, H.J.S.; Niciura, S.C.M.; Melito, G.R.; Cunha, A.F. da; Costa, E.C. da; de Campos, E.M.; Kapritchkoff, R.T.I.; Minho, A.P.; Esteves, S.N.; et al. Haemonchus Contortus Parasitic Stages Development and Host Immune Responses in Lambs of Different Sheep Breeds. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2025, 284, 110936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkower, D. Somatic Sex Determination. WormBook 2006, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antebi, A.; Yeh, W.H.; Tait, D.; Hedgecock, E.M.; Riddle, D.L. Daf-12 Encodes a Nuclear Receptor That Regulates the Dauer Diapause and Developmental Age in C. Elegans. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antebi, A. Nuclear Receptor Signal Transduction in C. Elegans. Wormbook 2015, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, M.; Chang, H.Y.; Chuguransky, S.; Grego, T.; Kandasaamy, S.; Mitchell, A.; Nuka, G.; Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Qureshi, M.; Raj, S.; et al. The InterPro Protein Families and Domains Database: 20 Years On. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D344–D354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.; Wang, T.; Korhonen, P.K.; Young, N.D.; Nie, S.; Ang, C.S.; Williamson, N.A.; Reid, G.E.; Gasser, R.B. Dafachronic Acid Promotes Larval Development in Haemonchus Contortus by Modulating Dauer Signalling and Lipid Metabolism. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcdonnell, D.P.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Pike, J.W.; Haussler, M.R.; O’Malley, B.W. Molecular Cloning of Complementary DNA Encoding the Avian Receptor for Vitamin D. Science (80-. ). 1987, 235, 1214–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makishima, M.; Okamoto, A.Y.; Repa, J.J.; Tu, H.; Learned, R.M.; Luk, A.; Hull, M. V.; Lustig, K.D.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Shan, B. Identification of a Nuclear Receptor for Bile Acids. Science (80-. ). 1999, 284, 1362–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doniach, T.; Hodgkin, J. A Sex-Determining Gene, Fem-1, Required for Both Male and Hermaphrodite Development in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Dev. Biol. 1984, 106, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.M.; Coulson, A.; Hodgkin, J. The Product of Fem-1, a Nematode Sex-Determining Gene, Contains a Motif Found in Cell Cycle Control Proteins and Receptors for Cell-Cell Interactions. Cell 1990, 60, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, A.; Gaudet, J.; Heck, L.; Kuwabara, P.E.; Spence, A.M. Negative Regulation of Male Development in Caenorhabditis Elegans by a Protein-Protein Interaction between TRA-2A and FEM-3. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Holman, T.; Lu, D.; Si, X.; Izevbigie, E.B.; Maher, J.F. The Fem1c Genes: Conserved Members of the Fem1 Gene Family in Vertebrates. Gene 2003, 314, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, H.E.; Berlin, D.S.; Lapidus, D.M.; Nusbaum, C.; Davis, T.L.; Meyer, B.J. Dosage Compensation Proteins Targeted to X Chromosomes by a Determinant of Hermaphrodite Fate. Science (80-. ). 1999, 284, 1800–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.J. Targeting X Chromosomes for Repression. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2010, 20, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Hermanson, S.; Ekker, S.C. Syndecan-2 Is Essential for Angiogenic Sprouting during Zebrafish Development. Blood 2004, 103, 1710–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoyi, K.; Osorio, J.C.; Chu, S.G.; Fernandez, I.E.; De Frias, S.P.; Sholl, L.; Cui, Y.; Tellez, C.S.; Siegfried, J.M.; Belinsky, S.A.; et al. Lung Adenocarcinoma Syndecan-2 Potentiates Cell Invasiveness. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019, 60, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genes | Sequence Forward | Sequence reverse | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| sod | GCTGGCACTGATGATTTGGG | CGCCAGCATTTCCTGTCTTC | 62 |

| daf-12 | ATGCAAGGCGTTTTTCCGTC | CGACCATCGGCGAAATTGAC | 60 |

| fem-1 | GATGCGTTGAAGCTGTTGG | CACGAAGGTTACGGTTTGC | 60 |

| sdc-2 | CGAGTCCAGCGATTCATCCA | AGCTGTCGTTTGCGTCACTA | 60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).