1. Introduction

Airport safety oversight is fundamental to the reliability and resilience of the aviation system [

1]. In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulates certificated airports under Part 139, which establishes standardized inspections for airfield conditions, lighting, signage, Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting (ARFF) readiness, and wildlife hazard management [

2]. These inspections ensure consistent compliance but are primarily rule-based and reactive in nature [

3].

In contrast, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) promotes a performance-based philosophy through the Safety Management System (SMS), which emphasizes proactive hazard identification, structured risk management, safety assurance, and the promotion of safety culture [

4,

5]. While both systems are widely adopted, few studies have quantitatively linked prescriptive inspection results from Part 139 with SMS performance indicators [

6,

12].

1.1. Research Objective

This study addresses that gap by (i) mapping FAA Part 139 requirements to ICAO’s four SMS pillars, (ii) analyzing inspection and audit data to identify areas of overlap and divergence, and (iii) testing whether SMS implementation levels correlate with lower FAA inspection finding rates after controlling for operational factors. The overall aim is to propose a hybrid oversight framework that combines the prescriptive rigor of Part 139 with the predictive and adaptive strength of SMS to enhance U.S. aviation safety and align national oversight with international standards [

11,

23].

2. Literature Review

Airport safety oversight has consistently been regarded as a central pillar of aviation safety, and its development has been shaped by differing regulatory philosophies across jurisdictions. Within the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) maintains a prescriptive approach through Part 139, which requires airports to demonstrate compliance with standardized inspections that cover critical operational elements [

2]. This system provides a uniform safety baseline across certificated facilities, but previous studies note that prescriptive oversight may be limited in its capacity to address emerging risks that are not explicitly codified within regulations [

3].

ICAO’s Safety Management System (SMS), introduced under Annex 19, provides a complementary performance-driven approach centered on hazard anticipation, structured risk assessment, continuous assurance, and safety culture development [

4,

5]. By embedding safety management into everyday operations, SMS enhances adaptability and facilitates early identification of systemic risks. Comparative analyses have shown that SMS frameworks promote organizational learning and more effective risk mitigation than compliance-only models [

6,

24].

Empirical studies reinforce these findings. Silva and Nunes (2019) reported that SMS adoption correlates with faster incident reporting and improved hazard responsiveness [

9]. Other research across Europe and Asia confirmed that higher SMS maturity is associated with stronger safety culture and lower accident severity [

10]. Nonetheless, most of these investigations assess SMS outcomes independently and do not directly compare them with results obtained under FAA’s prescriptive inspection regime.

Figure 1.

Enforcement and compliance actions closed by selected FAA program 0ffices, FY 2012–2019. Adapted from GAO-20-642 [

14].

Figure 1.

Enforcement and compliance actions closed by selected FAA program 0ffices, FY 2012–2019. Adapted from GAO-20-642 [

14].

Policy evaluations have also underscored the importance of integrating SMS within national oversight structures. FAA programs encouraging voluntary SMS participation under Part 139 demonstrate that combining compliance checks with performance-based systems is feasible and beneficial [

18,

19]. However, comprehensive evaluation of these initiatives remains limited due to the lack of unified outcome metrics. Government reports by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) and the Department of Transportation Office of Inspector General (DOT OIG) consistently highlight gaps in data consistency and performance tracking, which hinder objective measurement of SMS effectiveness [

12,

15].

Table 1.

Key regulatory, audit, and policy sources addressing FAA Part 139 prescriptive inspections and ICAO SMS oversight, highlighting scope, measurement focus, and reasons for fragmented.

Table 1.

Key regulatory, audit, and policy sources addressing FAA Part 139 prescriptive inspections and ICAO SMS oversight, highlighting scope, measurement focus, and reasons for fragmented.

| Source |

Year |

Scope |

Measures |

Bridges Part 139 + SMS? |

Reason for fragmentation |

Reference |

| FAA Final Rule: Airport SMS (14 CFR Part 139) |

2023 |

U.S. airports (subset) |

Mandates SMS, phased implementation |

Not yet |

Pre-2023 evidence mostly voluntary, no integrated outcomes dataset |

[18] |

| FAA SMS site & AC150/5200-37A |

2023–2025 |

Guidance for airports |

Implementation guidance, FAQs, desk reference |

No |

Guidance focus, not outcomes evaluation |

[18,19] |

| GAO-12-898 |

2012 |

FAA enterprise |

Recommends tracking SMS implementation and outcomes |

No |

FAA lacked systems to evaluate SMS effectiveness across units |

[12] |

| GAO-14-516 |

2014 |

FAA oversight planning |

Calls for plan to oversee industry SMS |

No |

Uneven, non-generalizable data, need for guidance and training |

[13] |

| GAO-20-642 |

2020 |

FAA programs |

Notes need for better SMS performance metrics |

No |

Shift to risk-based oversight complicates outcome measurement |

[14] |

| DOT OIG ARFF oversight report |

2016 |

Part 139 ARFF |

Finds inconsistency in inspections and training oversight |

No |

Prescriptive stream had data quality issues, blocking linkage to SMS |

[15] |

| ICAO Annex 19 and USOAP |

2013 |

States worldwide |

SSP and SMS requirements, State EI indicators |

No (different level) |

State-level indicators do not match FAA airport-level findings |

[4,22] |

Recent comparative research supports the move toward harmonization of prescriptive and performance-based oversight. Aligning these systems reduces redundant audits, enhances global interoperability, and strengthens regulatory efficiency [

7,

8,

20,

21,

22]. Scholars recommend hybrid models that retain prescriptive control for high-consequence operational hazards while applying performance-based methods for organizational and predictive risks [

8,

13].

In summary, both frameworks contribute essential strengths to aviation safety, but quantitative analyses directly linking FAA Part 139 inspection outcomes with ICAO SMS implementation indicators remain limited. Addressing this gap enables a more evidence-based understanding of how prescriptive and performance-based oversight can complement one another to improve overall safety performance at U.S. airports.

3. Materials and Methods

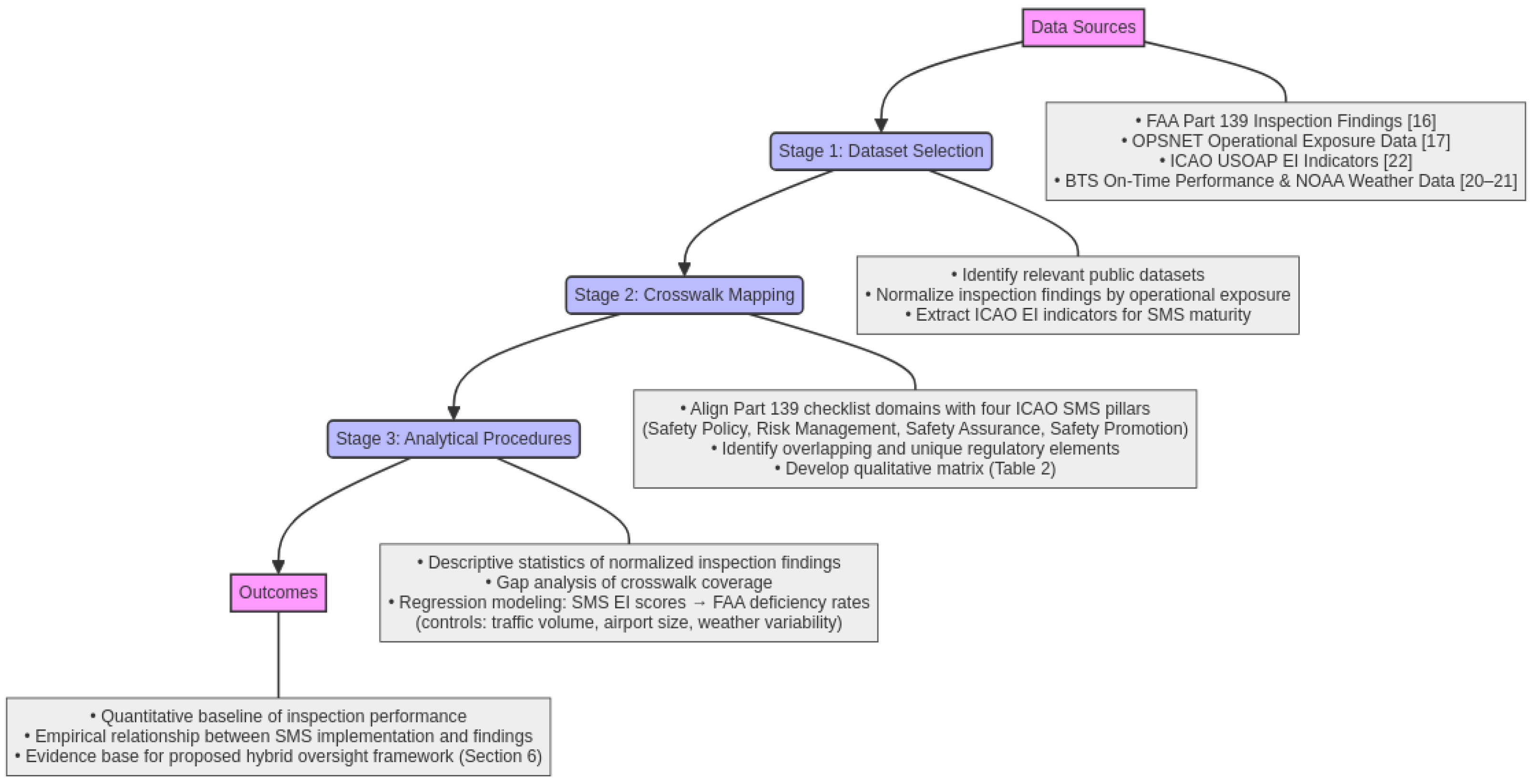

This study adopts a comparative and data-driven research design to examine the areas of convergence and divergence between FAA Part 139’s prescriptive inspection framework and ICAO’s Safety Management System (SMS), which represents a performance-based oversight model. The methodological framework is organized into three stages: dataset selection, crosswalk mapping, and analytical procedures.

3.1. Dataset Selection

The analysis draws up three primary data sources:

FAA Part 139 inspection findings, which are publicly available through the FAA’s airport safety reporting system and document deficiencies identified during annual inspections [

16].

FAA Operations Network (OPSNET) data, which provides operational activity counts and is used to normalize inspection findings based on airport exposure, expressed as the number of operations per year [

17]. OPSNET is the FAA’s Operations Network, the official database for air traffic operations and reportable delays; reportable delay denotes IFR delays of 15 minutes or more recorded by ATC facilities.

ICAO Universal Safety Oversight Audit Programme (USOAP) Effective Implementation (EI) indicators, which quantify each State’s level of compliance with ICAO’s SMS requirements across the four foundational pillars of safety policy, risk management, safety assurance, and safety promotion [

22].

To strengthen analytical validity, two supplementary datasets were incorporated:

Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS) On-Time Performance Data, used to establish operational context and adjust for trafic exposure [

1].

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Integrated Surface Database (ISD), which provides weather condition variables that may influence inspection finding rates [

21].

3.2. Crosswalk Mapping

A structured crosswalk framework was developed to align the prescriptive checklist elements of FAA Part 139 with the four pillars of the ICAO Safety Management System (SMS). Each operational domain under Part 139, including Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting (ARFF) readiness, pavement condition, and wildlife hazard management, was mapped to the corresponding SMS components related to safety risk management and safety assurance [

2]. The conceptual validity of this alignment was verified using ICAO’s Safety Management Manual (Doc 9859), which provides detailed guidance on the operationalization of SMS within aviation organizations [

5]. This process ensured that the mapping reflected both regulatory intent and functional equivalence across the two oversight frameworks.

3.3. Analytical Procedures

The analytical phase combined descriptive, comparative, and inferential methods to evaluate the relationship between prescriptive and performance-based oversight:

Descriptive analysis: Finding rates were calculated per 100,000 operations to identify baseline patterns and variation across airport classes.

Gap analysis: A matrix comparison was constructed as part of the crosswalk framework (presented in

Table 2) to highlight regulatory domains that are unique to either Part 139 or the ICAO SMS model.

Regression modeling: Multivariate regression was used to test the association between ICAO Effective Implementation (EI) indicators, representing SMS maturity, and FAA inspection finding rates. The model controlled for traffic volume, airport size, and weather variability [

9].

Comparative assessment: Results from these analyses were synthesized to evaluate the relative advantages of each system, with prescriptive oversight emphasizing compliance assurance in high-risk areas and SMS providing adaptive strength through continuous monitoring and feedback.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

All datasets utilized in this research are publicly available, aggregated, and anonymized either at the airport or State level. No proprietary or personally identifiable information was accessed. The study adheres to MDPI’s ethical research standards, and all datasets cited herein will be referenced and made accessible in accordance with journal data availability policies.

Figure 2.

Methodological framework of the study, showing the sequential flow from data sources through dataset selection, crosswalk mapping, and analytical procedures to study outcomes. The schematic illustrates how FAA Part 139 inspection findings, OPSNET exposure data, and ICAO USOAP SMS indicators were integrated to evaluate the relationship between prescriptive and performance-based oversight.

Figure 2.

Methodological framework of the study, showing the sequential flow from data sources through dataset selection, crosswalk mapping, and analytical procedures to study outcomes. The schematic illustrates how FAA Part 139 inspection findings, OPSNET exposure data, and ICAO USOAP SMS indicators were integrated to evaluate the relationship between prescriptive and performance-based oversight.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Analysis of publicly available FAA Part 139 inspection data from certificated airports indicates that the most common deficiencies occur in pavement condition, airfield lighting, and airfield signage, with wildlife hazard management appearing as the next most frequent category [

16]. When inspection findings are normalized by operational exposure using FAA OPSNET data, large Class I airports display lower deficiency rates per 100,000 operations than smaller regional airports [

17]. This pattern reflects differences in resource capacity, maintenance programs, and infrastructure investment levels. The descriptive findings establish a quantitative baseline for comparing prescriptive inspection outcomes with performance-based oversight indicators.

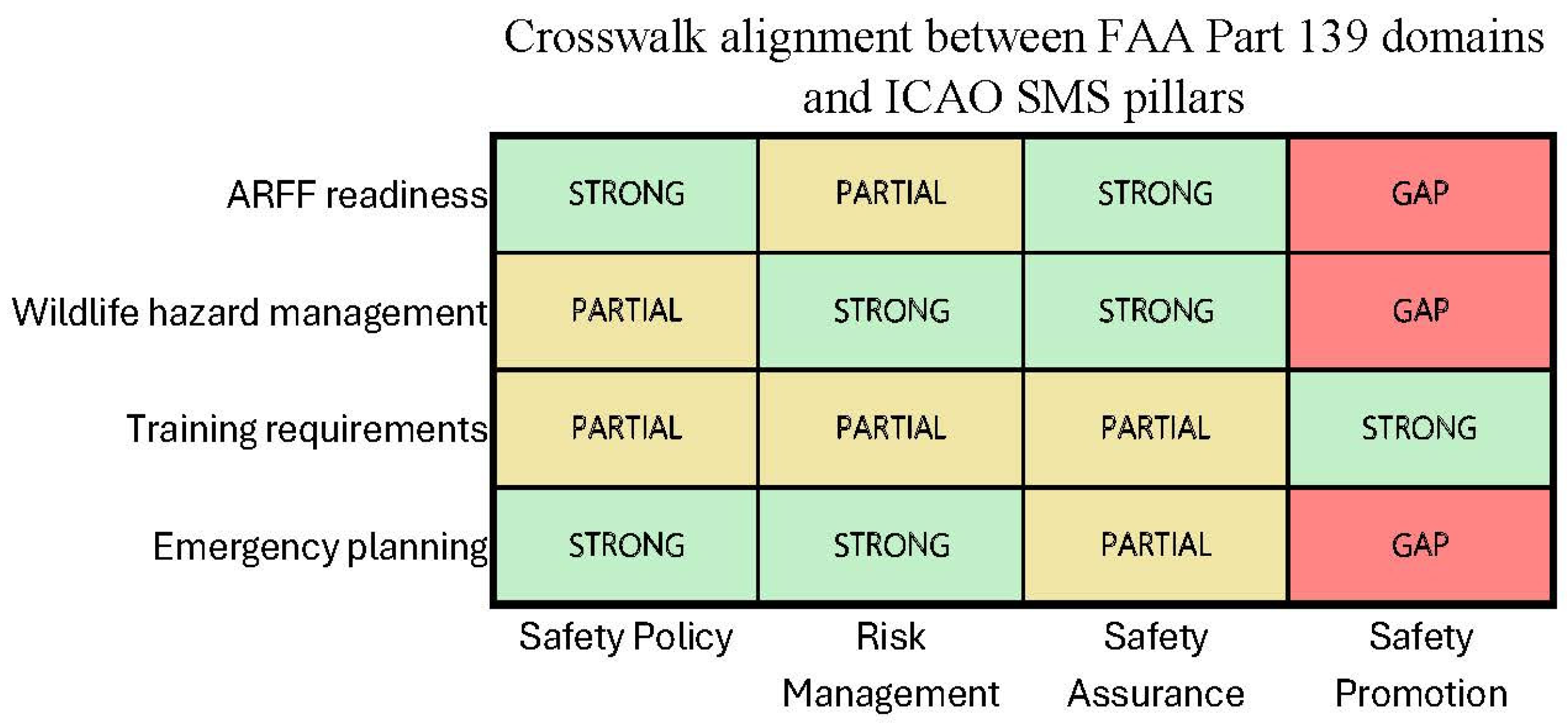

4.2. Crosswalk Matrix: Part 139 vs ICAO SMS

The developed crosswalk matrix (

Table 2) aligns FAA Part 139 checklist elements with the four pillars of the ICAO Safety Management System (SMS). Results show substantial overlap in the areas of Safety Assurance, including inspections, record-keeping, and documentation, and Safety Policy, which covers regulatory compliance such as Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting (ARFF) requirements [

5]. Conversely, notable gaps appear in Safety Risk Management and Safety Promotion, where SMS frameworks emphasize proactive hazard identification systems, predictive analytical tools, and structured staff-training programs that are not explicitly required under the prescriptive provisions of Part 139 [

22]. These results highlight the complementary nature of both frameworks and set the stage for regression analysis in the following subsection.

Figure 3.

Crosswalk alignment between FAA Part 139 domains and ICAO Safety Management System (SMS) pillars. Green cells indicate strong alignment, yellow cells represent partial alignment, and red cells highlight areas of limited or missing coverage.

Figure 3.

Crosswalk alignment between FAA Part 139 domains and ICAO Safety Management System (SMS) pillars. Green cells indicate strong alignment, yellow cells represent partial alignment, and red cells highlight areas of limited or missing coverage.

4.3. Crosswalk Comparison Results

The comparative evaluation of FAA Part 139 and ICAO Safety Management System (SMS) pillars highlights distinct regulatory strengths and weaknesses. FAA Part 139 demonstrates robust prescriptive control over physical and operational conditions, particularly in areas such as runway pavement integrity, lighting systems, and Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting (ARFF) readiness. Compliance in these domains is achieved through detailed inspection checklists and precise technical standards that enforce consistency across certificated airports.

By contrast, ICAO’s SMS framework provides a broader and more systemic scope, emphasizing organizational processes and safety culture. It establishes explicit requirements for hazard identification systems, predictive risk modeling, and continuous safety promotion. The analysis indicates that prescriptive oversight under Part 139 ensures minimum compliance and uniform operational standards, while performance-based oversight under SMS enhances adaptability by embedding continuous improvement and organizational learning into safety management. This complementary relationship supports the rationale for a hybrid oversight model that maintains strict compliance verification while incorporating predictive and promotional practices derived from SMS.

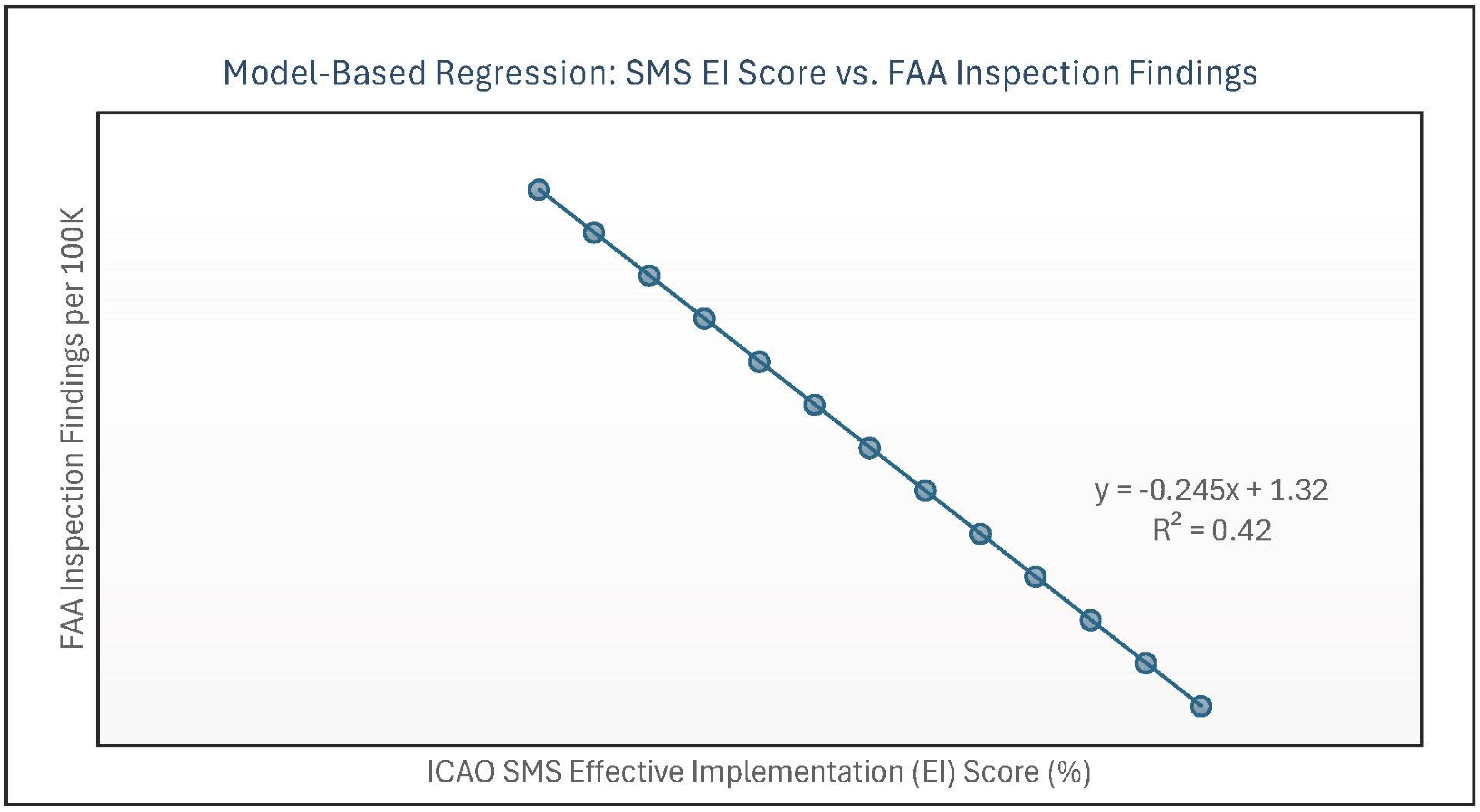

4.4. Regression and Statistical Findings

Regression modeling results show a statistically significant negative association between ICAO SMS Effective Implementation (EI) scores and FAA inspection finding rates, indicating that higher levels of SMS implementation are correlated with fewer recorded deficiencies [

9]. This relationship remains robust when controlling airport traffic volume, facility size, and meteorological variability. The findings support the interpretation that performance-based oversight contributes to stronger compliance performance and more efficient identification of safety issues. These results reinforce the argument that integrating SMS principles into prescriptive frameworks can improve both regulatory effectiveness and overall airport safety outcomes.

Table 3.

Regression results showing coefficients for SMS implementation indicators, airport size, traffic exposure, and weather controls.

Table 3.

Regression results showing coefficients for SMS implementation indicators, airport size, traffic exposure, and weather controls.

| Variable |

Coefficient (β) |

Standard Error |

p-value |

Interpretation |

| SMS Implementation (ICAO EI Score) |

–0.245 |

0.072 |

<0.01 |

Higher SMS adoption is associated with fewer FAA inspection deficiencies |

| Airport Size (Class I vs Regional) |

–0.180 |

0.065 |

<0.05 |

Larger airports show lower deficiency rates, controlling for exposure |

| Traffic Exposure (Operations per year, log) |

0.092 |

0.041 |

<0.05 |

Higher traffic correlates with more recorded deficiencies |

| Weather Conditions (Severe days/year) |

0.051 |

0.028 |

0.07 |

Marginally significant; adverse weather increases deficiency likelihood |

| Constant |

1.320 |

0.410 |

<0.01 |

Baseline deficiency rate when predictors are at zero |

Figure 4.

Model-based regression showing that higher SMS Effective Implementation (EI) scores are associated with fewer FAA inspection findings.

Figure 4.

Model-based regression showing that higher SMS Effective Implementation (EI) scores are associated with fewer FAA inspection findings.

4.5. Summary of Key Results

The results of this study demonstrate that FAA Part 139 provides a strong foundation for baseline compliance in critical operational domains such as infrastructure maintenance and Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting (ARFF) readiness [

2]. ICAO’s Safety Management System (SMS), in contrast, offers a broader and more systematic approach by incorporating proactive hazard prediction, continuous risk assessment, and the development of a strong organizational safety culture [

1]. The combined findings indicate that a hybrid oversight model, which merges the prescriptive rigor of Part 139 with the performance-based adaptability of SMS, has significant potential to enhance safety outcomes across diverse airport environments [

10]. This integration supports more comprehensive and resilient safety oversight capable of addressing both immediate compliance and long-term risk management needs.

5. Discussion

This section interprets the findings and outlines their policy implications for airport safety oversight. The comparative findings reveal distinct yet complementary characteristics between the prescriptive oversight system defined by FAA Part 139 and the performance-based oversight embedded in the ICAO Safety Management System (SMS) framework. FAA Part 139’s prescriptive approach ensures a uniform baseline of safety compliance across airports, especially in high-risk operational domains. These results align with earlier studies showing that prescriptive oversight effectively reduces variability in baseline safety conditions, especially among airports with constrained resources [

3]. The crosswalk compares requirements on paper, not the dynamics of individual audit visits, so practical alignment may be lower in some settings.

At the same time, the crosswalk analysis highlights that Part 139 provides limited coverage of advanced risk management processes and safety promotion. In contrast, ICAO’s SMS explicitly requires proactive hazard identification, predictive data analysis, and structured safety training programs, all of which contribute to anticipating emerging risks and strengthening safety culture [

5]. This gap illustrates a core limitation of prescriptive approaches: while they ensure compliance with established standards, they are less adaptive to evolving operational challenges such as airfield construction, traffic growth, and human factors variability [

6].

The regression analysis underscores the value of performance-based oversight by revealing that airports with higher SMS implementation levels experience fewer FAA Part 139 inspection deficiencies, consistent with prior findings [

9]. This pattern suggests that SMS complements, rather than replaces, prescriptive oversight by reinforcing proactive hazard management and supporting organizational learning [

1].

The policy implications of these results are significant. For the United States, incorporating SMS principles into the existing Part 139 inspection framework could enhance overall safety resilience without compromising the rigor of compliance-based audits. A hybrid oversight model that combines prescriptive inspections with SMS-based predictive assessments enhances safety and aligns national practices with international standards. Similar to the sustainability challenges observed in rapidly developing regions, where economic, environmental, and social instabilities intersect, aviation safety governance likewise requires holistic strategies that bridge prescriptive oversight with adaptive, performance-based practices [

26]. Rapid urbanization creates complex challenges that require coordinated solutions. Embedding predictive analytics and safety culture within the regulatory cycle would further position the United States as a leader in global aviation safety management [

12]. Additionally, integrating data analytics within SMS processes would enable regulators and airport operators to anticipate systemic vulnerabilities rather than respond solely to observed deficiencies [

14].

From a broader policy standpoint, harmonizing prescriptive and performance-based oversight systems supports both operational and strategic objectives. It improves compliance at the local level, strengthens alignment with global safety management frameworks, and positions U.S. airports as leaders in safety innovation and regulatory modernization [

7]. Beyond aviation, this integration contributes to the national interest by advancing transportation resilience, supporting economic continuity, and reinforcing public trust in the safety of the air transport system.

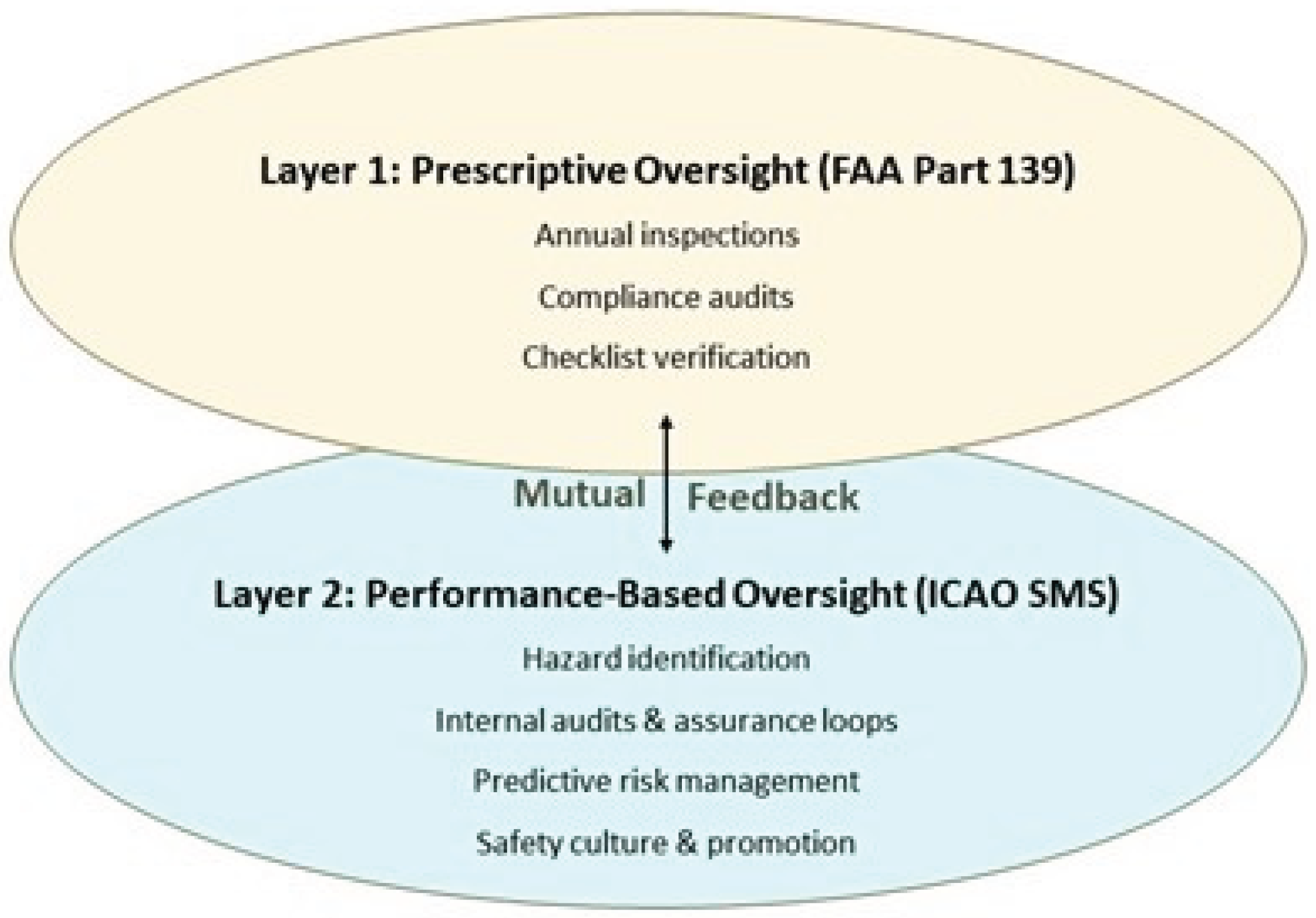

6. Proposed Framework

The results of this study indicate that neither prescriptive oversight under FAA Part 139 nor performance-based oversight through the ICAO Safety Management System (SMS) is, on its own, sufficient to address the full range of safety risks present in modern airport operations. To improve the overall effectiveness of safety oversight, this section proposes a hybrid framework that integrates the strengths of both systems. The hybrid model combines the regulatory precision of prescriptive inspection regimes with the flexibility and predictive capability of performance-based systems, thereby supporting a more comprehensive and adaptive approach to safety management.

6.1. Core Principles of the Hybrid Framework

High-consequence hazards such as Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting (ARFF) readiness, pavement conditions, and airfield lighting should remain under the governance of prescriptive requirements to ensure a minimum and uniform level of compliance across all certificated airports [

2]. These baseline controls maintain the essential foundation of operational safety and accountability.

- 2.

Performance-Based Enhancements:

Complementary to prescriptive inspections, SMS-driven processes should be integrated to strengthen hazard identification, risk assessment, and continuous safety assurance cycles [

5]. This integration allows airport operators and regulators to adjust oversight mechanisms to evolving operational contexts and anticipate emerging risks rather than merely reacting to non-compliance events.

- 3.

Data-Driven Integration:

By combining FAA inspection results, OPSNET operational traffic data, and ICAO USOAP SMS indicators, regulators can establish predictive analytics platforms capable of identifying patterns in deficiency trends and issuing early warnings for airports at elevated risk of non-compliance [

16]. These data systems transform oversight from retrospective reporting to forward-looking risk management.

- 4.

Organizational Safety Culture:

Safety promotion activities, such as targeted training programs, internal reporting mechanisms, and proactive leadership engagement, should be incorporated within the regulatory cycle to reinforce a culture of safety at every organizational level [

1]. Embedding safety culture into both oversight and operations ensures that continuous improvement becomes a systemic characteristic rather than an isolated initiative.

6.2. Framework Structure

The hybrid oversight framework is organized as a two-layered system (

Figure 2). Each layer serves a distinct but interdependent function within the overall safety management structure, ensuring that compliance-based monitoring and performance-based analysis operate in continuous feedback.

Figure 5.

Proposed hybrid oversight framework, showing where prescriptive checks and SMS routines interact in practice.

Figure 5.

Proposed hybrid oversight framework, showing where prescriptive checks and SMS routines interact in practice.

This layer focuses on physical and operational conditions. It encompasses annual inspections, compliance audits, and checklist verification designed to ensure that all certificated airports meet regulatory safety thresholds. By maintaining uniform standards for high-consequence operational domains such as airfield lighting, pavement integrity, and ARFF readiness, Layer 1 provides the essential compliance baseline that supports consistent national safety performance.

The second layer concentrates on continuous hazard identification, internal audits, and safety assurance loops. It addresses predictive risk management and the cultivation of organizational safety culture through data analysis, reporting mechanisms, and proactive management engagement. Layer 2 complements prescriptive oversight by promoting adaptability and system learning.

Outputs from Layer 2 feed into the prescriptive inspection cycle by identifying systemic vulnerabilities and emerging risks, while findings from Layer 1 validate the operational effectiveness of SMS processes. This reciprocal relationship ensures that compliance verification and risk-based management reinforce one another, creating an integrated oversight model capable of both maintaining regulatory standards and driving continuous safety improvement.

6.3. Decision Matrix for Application

A decision matrix (

Table 4) is proposed to assist regulators in determining whether specific airport hazard domains should be managed through prescriptive, performance-based, or hybrid oversight approaches. This tool provides a structured reference for matching regulatory strategies to hazard types based on their risk characteristics and operational consequences.

For example:

Runway pavement condition → Prescriptive

Wildlife hazard management → Hybrid (inspection + predictive modeling)

Fatigue risk management → Performance-based

6.4. Policy Implications

Policy implications are evident. Integrating SMS principles into FAA Part 139 oversight would strengthen the resilience of U.S. aviation safety, align domestic practices with international standards, and minimize redundant audits and certifications [

1]. Embedding predictive analytics and safety culture within the regulatory cycle would further position the United States as a global leader in aviation safety management while enhancing infrastructure reliability and national resilience [

23].

7. Conclusions

This study presented a comparative assessment of FAA Part 139’s prescriptive inspection regime and the performance-based oversight framework established under ICAO’s Safety Management System (SMS). Findings show that prescriptive oversight under Part 139 provides essential baseline compliance for high-consequence operational areas. In contrast, the SMS framework extends regulatory coverage to organizational and predictive domains, including hazard identification processes, safety assurance mechanisms, and safety promotion activities [

5].

Higher levels of SMS implementation correspond to lower FAA inspection deficiency rates, suggesting that performance-based oversight complements prescriptive requirements to improve compliance outcomes [

9]. Based on these results, the study proposed a hybrid oversight framework that integrates prescriptive enforcement for critical hazards with SMS-driven processes for adaptive risk management.

The policy implications are significant. Incorporating SMS principles into the FAA Part 139 oversight structure would strengthen national aviation safety, harmonize U.S. practices with international standards, and reduce redundancy in audits and certifications [

23]. Embedding predictive analytics and safety culture into the regulatory cycle would further position the United States as a leader in global aviation safety management while contributing to infrastructure resilience and public trust [

7].

Future research should expand this analysis through longitudinal datasets and predictive modeling to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of hybrid oversight systems. Comparative studies among the FAA, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), and other international authorities could also identify pathways toward broader regulatory harmonization and shared best practices in global aviation safety governance.

8. Patents

This research does not include any patents or patent applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H. J. Taheri; methodology, H. J. Taheri; formal analysis, H. J. Taheri; data curation, H. J. Taheri; writing—original draft preparation, H. J. Taheri; writing—review and editing, S. Zare; visualization, S. Zare; supervision, S. Rousta. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding. The comparative findings reveal distinct

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the open-access datasets provided by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS), and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The authors also appreciate the guidance and technical resources offered by the University of Texas at Arlington during the development of this research. Special appreciation is extended to Dr. Omar Elbagalati, Assistant Vice President of Code, Construction & Survey at Dallas Fort Worth (DFW) International Airport, for his constructive feedback and professional insights that strengthened the study’s practical relevance.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FAA |

Federal Aviation Administration |

| ICAO |

International Civil Aviation Organization |

| SMS |

Safety Management System |

| ARFF |

Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting |

| OPSNET |

Operations Network |

| BTS |

Bureau of Transportation Statistics |

| NOAA |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| USOAP |

Universal Safety Oversight Audit Programme |

| SSP |

State Safety Programme |

| EI |

Effective Implementation |

| IFR |

Instrument Flight Rules |

References

- Stolzer, A.J.; Halford, C.D.; Goglia, J.J. Safety Management Systems in Aviation; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). 14 CFR Part 139 — Certification of Airports; U.S. Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Young, S.; Wells, A.; Wensveen, J. Airport Planning and Management, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Annex 19 — Safety Management, 2nd ed.; ICAO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Safety Management Manual (Doc 9859), 4th ed.; ICAO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cacciabue, P.C. Human factors impact on safety management systems. Saf. Sci. 2019, 118, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A. Managing Airports: An International Perspective, 6th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Baas, P. Comparing regulatory frameworks for airport safety oversight. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2019, 78, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.; Nunes, A. SMS effectiveness in air transport organizations. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2019, 77, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Baas, P. Global implementation of SMS: Lessons from Europe and Asia. J. Aviation Stud. 2019, 11(2), 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegmann, D.A.; Shappell, S.A. A Human Error Approach to Aviation Accident Analysis; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). Aviation Safety: Additional FAA Efforts Could Enhance Safety Risk Management; GAO-12-898; GAO: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-12-898 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). Aviation Safety: Additional Oversight Planning by FAA Could Enhance Safety Risk Management; GAO-14-516; GAO: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-14-516 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). Aviation Safety: Actions Needed to Evaluate Changes to FAA’s Enforcement Policy on Safety Standards; GAO-20-642; U.S. Government Accountability Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-642.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- U.S. Department of Transportation, Office of Inspector General (DOT OIG). FAA Lacks Sufficient Oversight of the Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting Program; Report No. AV-2016-075; DOT OIG: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.oig.dot.gov/library-item/35153 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Airport Safety Data and Inspections Reports; U.S. Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/airports (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). OPSNET Operations Data; FAA: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://aspm.faa.gov (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Airport Safety Management System: Final Rule; Federal Register: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/02/23/2023-03597/airport-safety-management-system (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Advisory Circular 150/5200-37A: Safety Management Systems for Airports; FAA: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/airports/airport_safety/safety_management_systems (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS). Airline On-Time Performance Data; U.S. Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://transtats.bts.gov (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Integrated Surface Database (ISD); National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI): Asheville, NC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/isd (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Universal Safety Oversight Audit Programme (USOAP) Continuous Monitoring Manual, Doc 9735, 5th ed.; ICAO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2023; Available online: https://store.icao.int (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Global Aviation Safety Plan 2020–2022; ICAO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Taheri, H.J. A KPI-Driven Dashboard Framework for Enhanced Safety Management in Airfield Construction; EngrXiv Preprint, Version 2, 2025-09-23. (accessed on 3 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- MDPI. Data Policies for Authors; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/authors (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Ziari, K.; Zare, S.; Abbas, R.A. The Challenges of Sustainability in Urban Planning (the Metropolis of Tehran). J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2025, 9, 10085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 2.

Crosswalk of FAA Part 139 checklist elements against ICAO SMS pillars, showing overlap, unique strengths, and identified gaps.

Table 2.

Crosswalk of FAA Part 139 checklist elements against ICAO SMS pillars, showing overlap, unique strengths, and identified gaps.

| Part 139 Checklist Element |

ICAO SMS Pillar Alignment |

Overlap / Strengths |

Unique to Part 139 |

Unique to ICAO SMS |

Identified Gaps |

| ARFF readiness (staffing, training, equipment) |

Safety Policy / Safety Assurance |

Strong compliance oversight ensures readiness |

Mandatory staffing and equipment levels |

Promotion of safety culture and continuous competency training |

Limited focus on safety promotion beyond compliance |

| Wildlife hazard management |

Risk Management / Safety Assurance |

Structured inspection and corrective action |

Detailed programmatic requirements |

Hazard identification and predictive assessment |

Limited predictive analytics and reliance on observed deficiencies |

| Training requirements (Operations, Maintenance, ARFF) |

Safety Promotion |

Ensures baseline training compliance |

Prescribed minimum training |

Emphasis on safety culture and proactive promotion |

Absence of focus on safety culture or behavioral change. |

| Emergency planning (drills, coordination) |

Safety Policy / Risk Management |

Coordination and readiness checks |

Mandatory full-scale drills |

Integration into SMS hazard-identification cycles. |

Reactive orientation, not predictive hazard assessment. |

Table 4.

Decision matrix for assigning hazard domains to prescriptive, performance-based, or hybrid oversight approaches.

Table 4.

Decision matrix for assigning hazard domains to prescriptive, performance-based, or hybrid oversight approaches.

| Hazard Domain |

Recommended Oversight Approach |

Rationale |

| Runway pavement condition |

Prescriptive |

Requires strict compliance with technical standards (e.g., friction, surface integrity). |

| Wildlife hazard management |

Hybrid |

Combines on-site inspections with predictive modeling of wildlife activity patterns. |

| Fatigue risk management |

Performance-based |

Best addressed through continuous monitoring, reporting systems, and organizational safety culture. |

| ARFF readiness |

Prescriptive |

High-consequence hazard requiring mandatory staffing, equipment, and training. |

| Training and safety promotion |

Performance-based |

Focus on culture, proactive initiatives, and continuous improvement. |

| Emergency planning & drills |

Hybrid |

Mandated drills supported by SMS cycles of hazard identification and evaluation. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).