Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Research Objectives

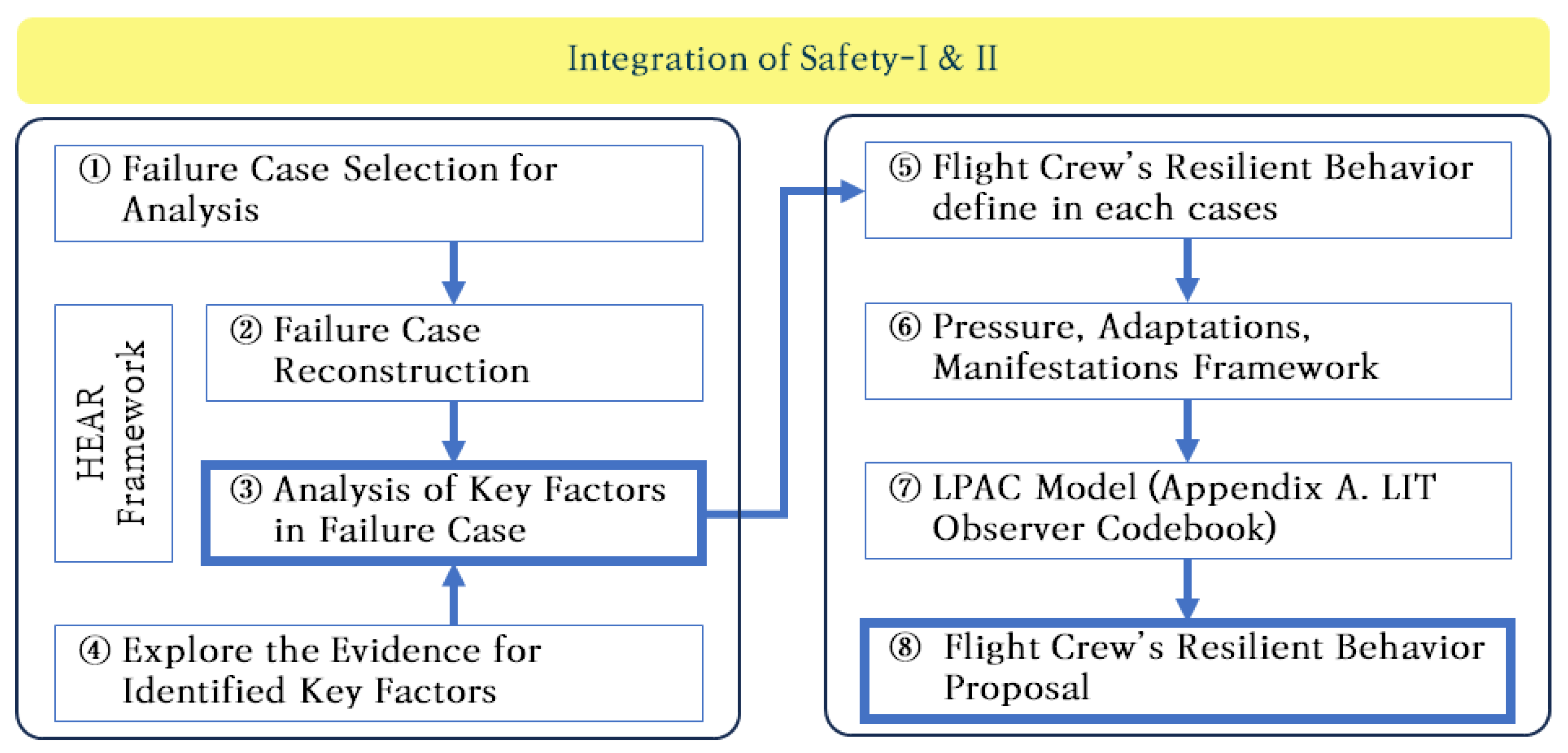

1.3. Research Methodology

2. Theoretical Background and Research Methodology

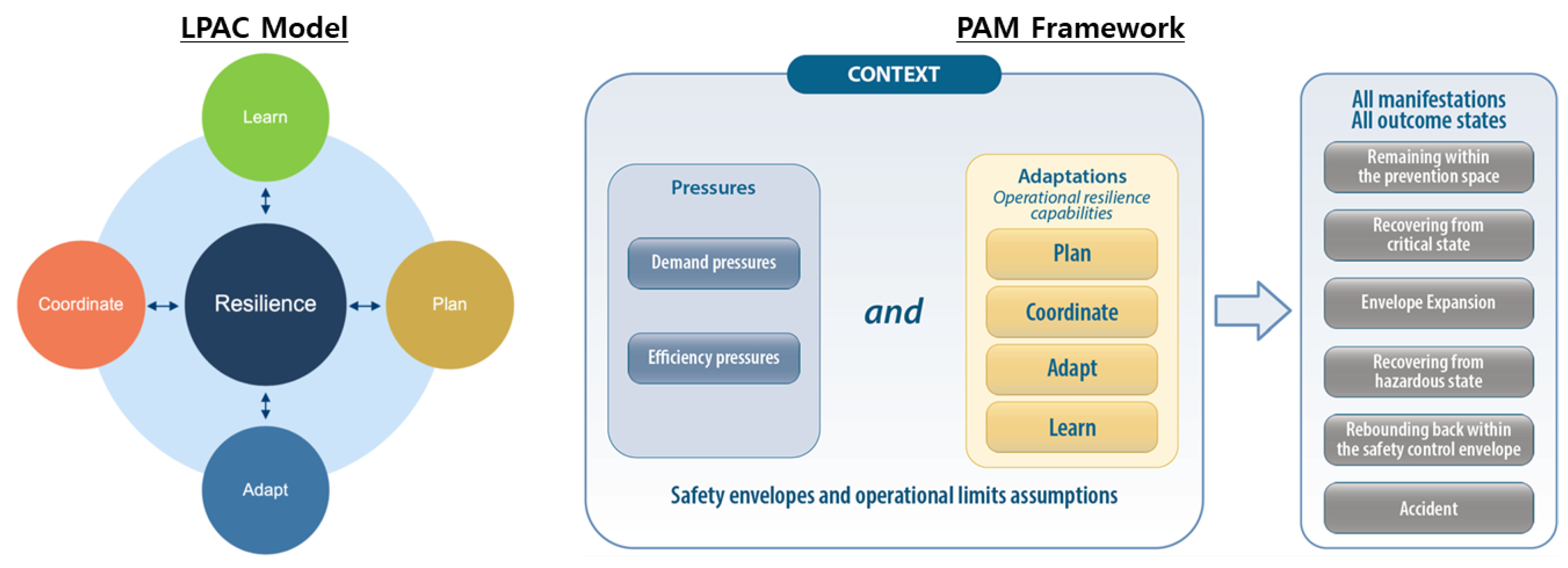

2.1. Comprehensive Understanding of Safety-I and Safety-II

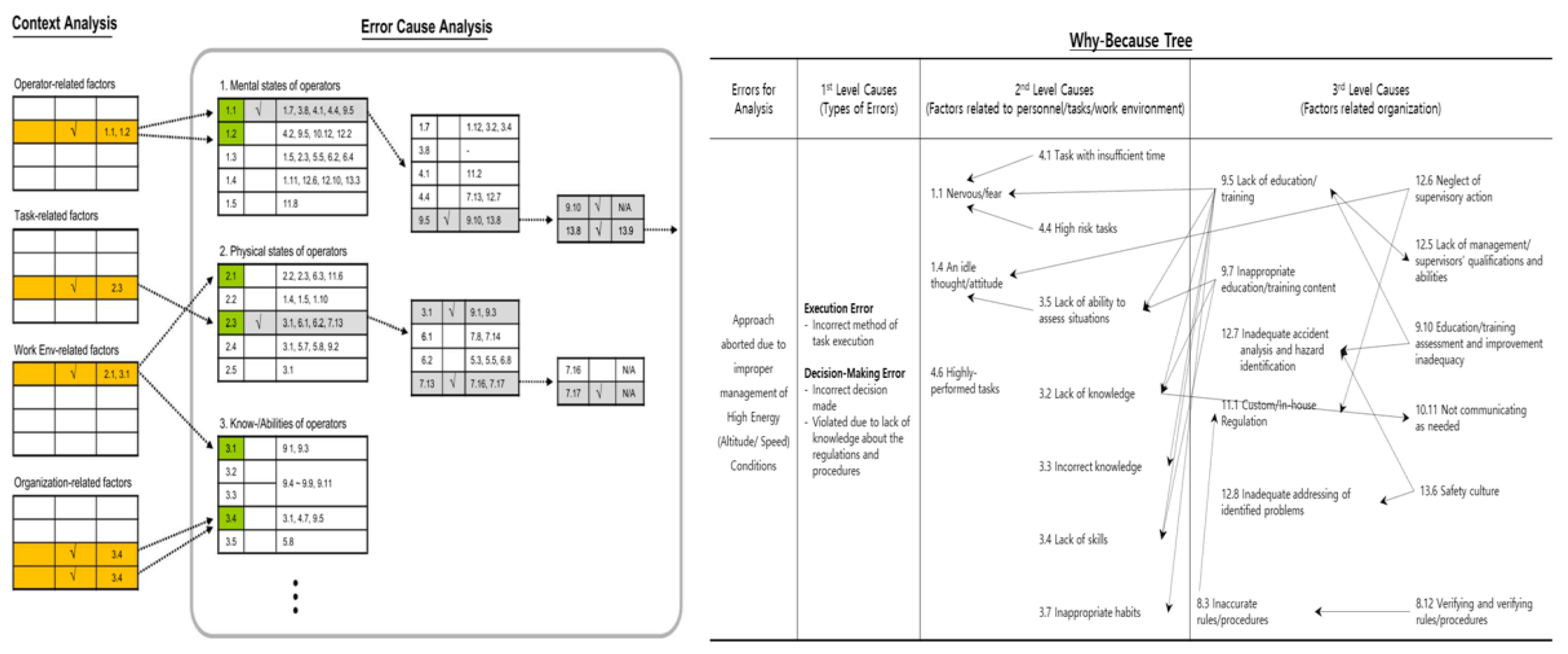

2.2. Research Methodology

2.3. Case Selection

3. Analysis and Results

3.1. Systematic Analysis Through Safety-I Methodology

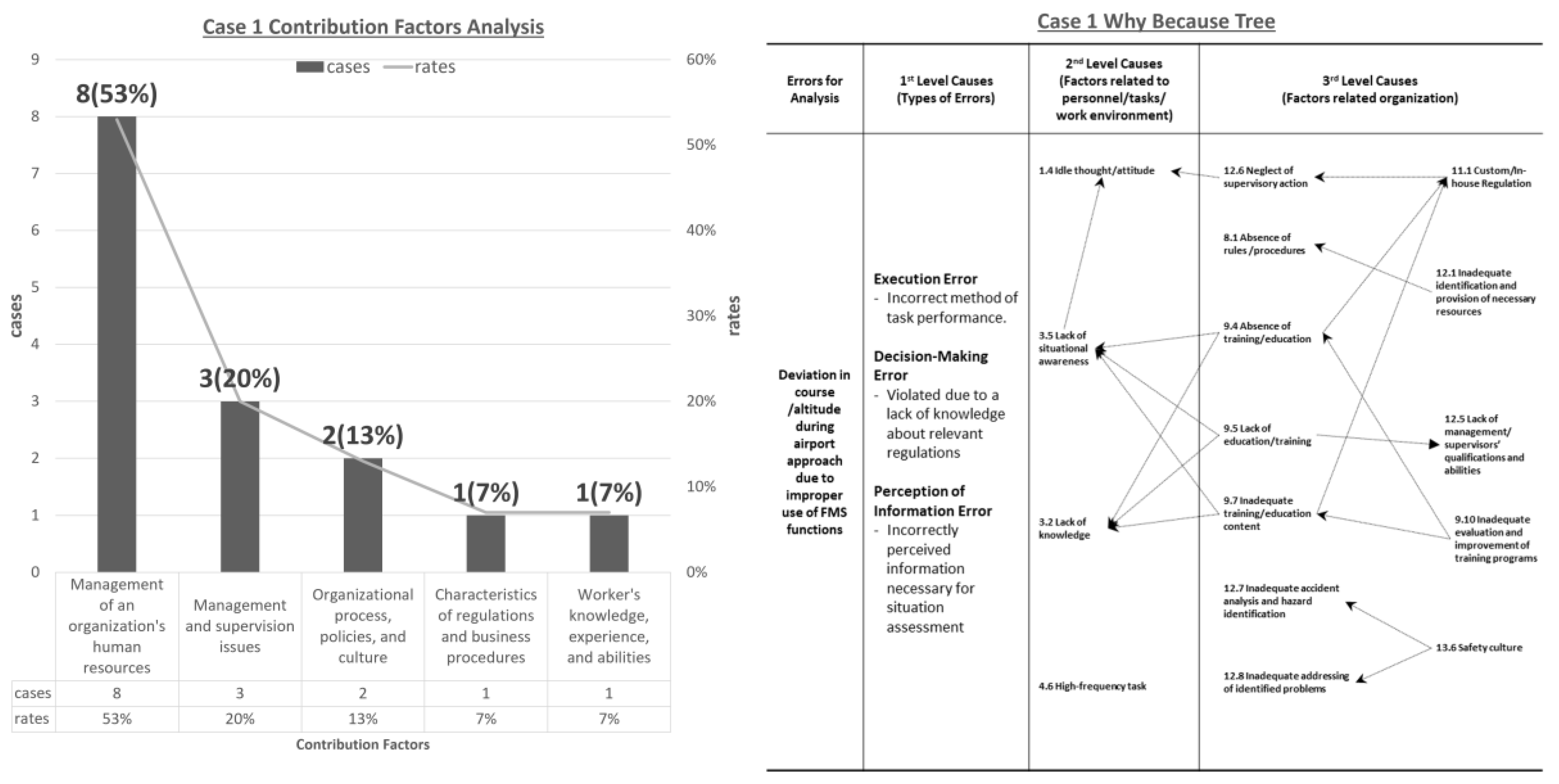

3.1.1. Case 1: Analysis of FMS (Flight Management System) Function-Related Failure Cases

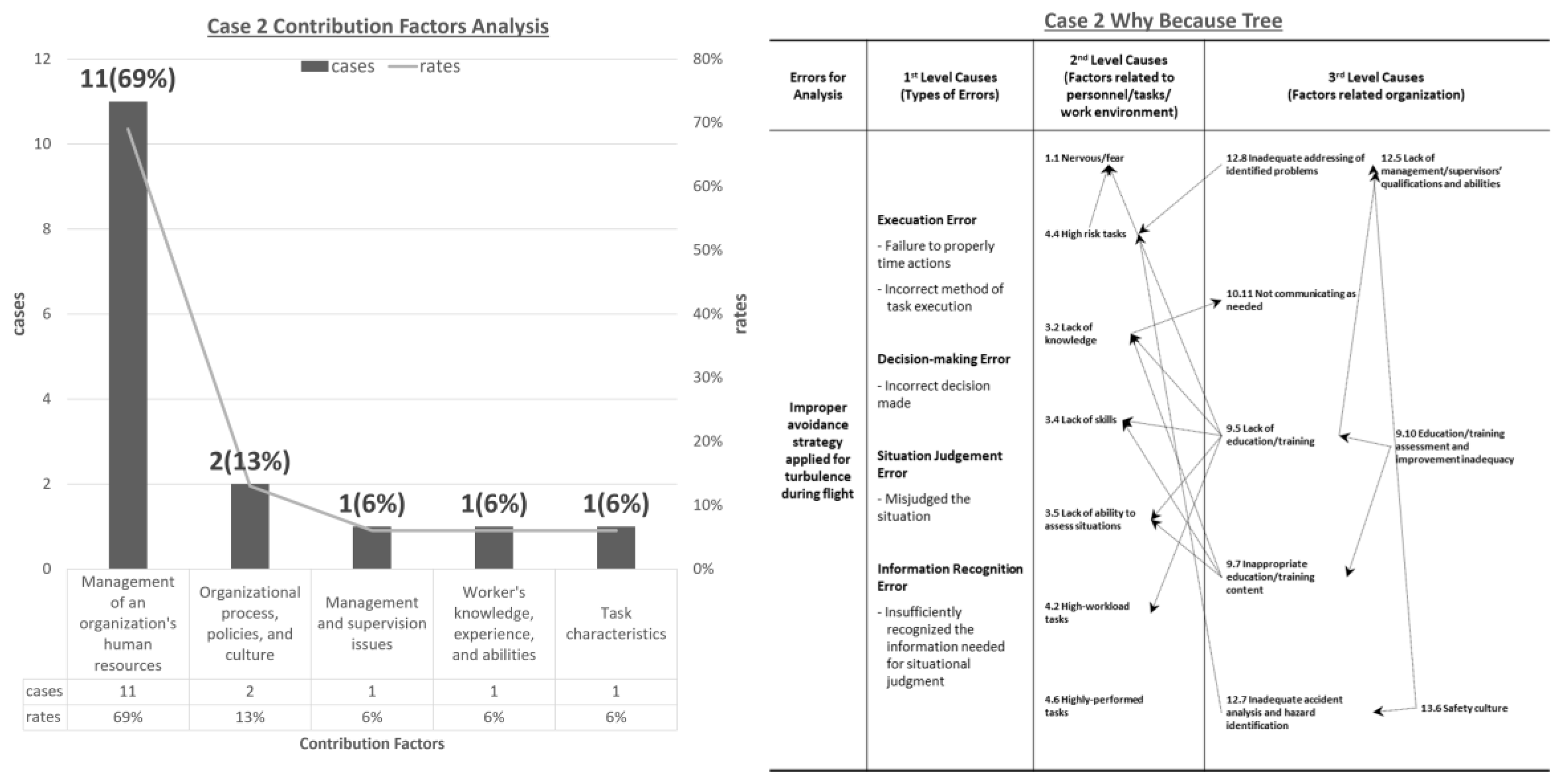

3.1.2. Case 2: Analysis of Turbulence-Related Failure Cases

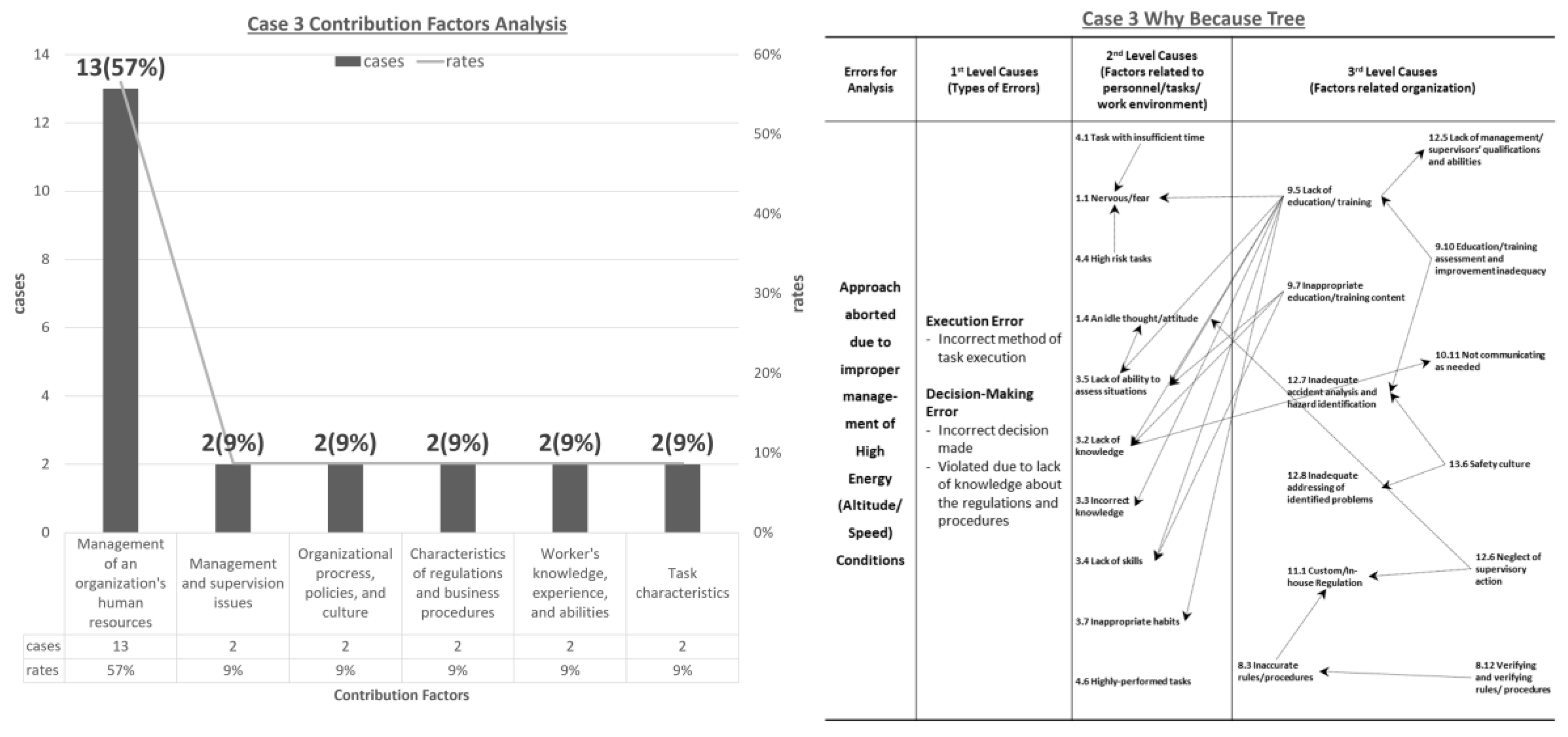

3.1.3. Case 3: Analysis of Aircraft Energy Management-Related Failure Cases

3.2. Comprehensive Analysis Results

4. Methods for Improving Resilient Behavior

4.1. Definition of ’Flight Crew’s Resilient Behavior’

4.2. Case-Specific Methods for Improving Resilient Behavior

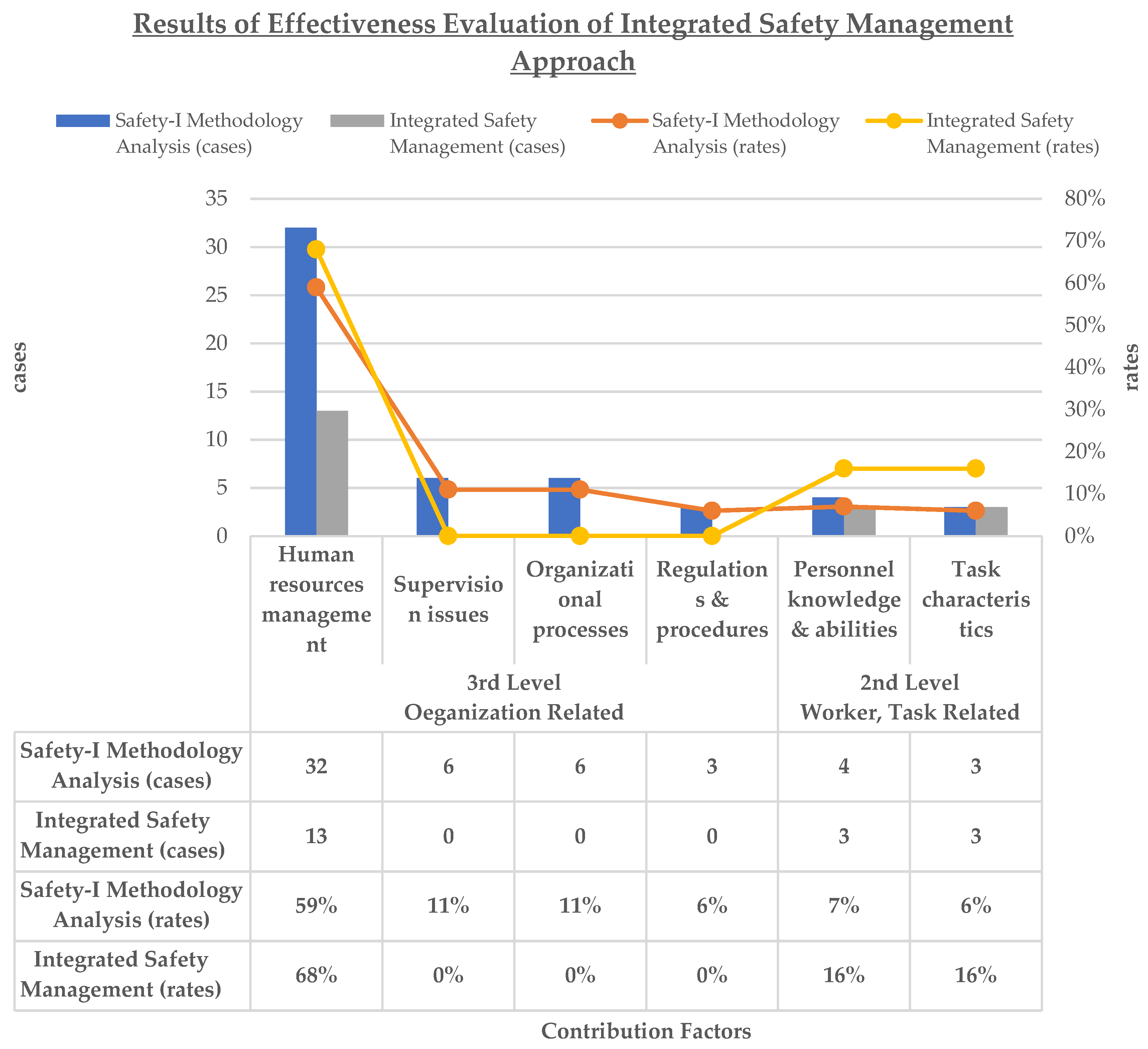

5. Evaluation of Integrated Safety Management Approach

5.1. Practical Application Guidelines for Integrated Safety Management

5.2. Analysis and Evaluation of Safety Management Improvement Effects

5.3. Future Improvement Tasks

6. Conclusions

6.1. Key Research Achievements

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Research Limitations and Future Tasks

References

- IATA. Interactive Safety Report. Available online: https://www.iata.org/en/publications/safety-report/interactive-safety-report/ (accessed on.

- Yoon, W.C. HEAR 6th Year Final Report. 2010, rev 5.

- Flight Safety Foundation. Learning From All Operations Concept Note 7: Pressures, Adaptations and Manifestations Framework. 2022.

- American Airlines Department of Flight Safety. Charting a new approach: What goes well and why at American Airlines, A whitepaper outlining the second phase of AA's Learning and Improvement Team(LIT). 2021.

- Hollnagel, E. Safety-I and safety-II: the past and future of safety management; CRC press: 2015.

- Hollnagel, E.; Pariès, J.; Woods, D.; Wreathall, J. Resilience Engineering in Practice: A Guidebook; 2010.

- EASA. Easy Access Rules for Flight Crew Licencing. 2020.

- American Airlines Department of Flight Safety. Trailblazers into Safety-II: American Airlines’ Learning and Improvement Team, A White Paper Outlining AA’s Beginnings of a Safety-II Journey. 2020.

- Kim, D.S.; Baek, D.H.; Yoon, W.C. Development and evaluation of a computer-aided system for analyzing human error in railway operations. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2010, 95, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOLIT. Cabin crew injury due to turbulence encountered during flight. 2022.

- Rasmussen, J. SKILLS, RULES, AND KNOWLEDGE - SIGNALS, SIGNS, AND SYMBOLS, AND OTHER DISTINCTIONS IN HUMAN-PERFORMANCE MODELS. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1983, 13, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.; Magis-Weinberg, L.; Jansen, B.R.J.; Van Atteveldt, N.; Janssen, T.W.P.; Lee, N.C.; Van Der Maas, H.L.J.; Raijmakers, M.E.J.; Sachisthal, M.S.M.; Meeter, M. Motivation-Achievement Cycles in Learning: a Literature Review and Research Agenda. Educational Psychology Review 2022, 34, 39–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisa, S. Metacognition: The Thinking Parent Makes the Thinking Child; book21: 2019.

- Flight Safety Foundation. Learning From All Operations Concept Note 6: Mechanism of Operational Resilience. 2022.

- EUROCONTROL; Hollnagel, E.; Leonhardt, J.; Licu, T.; Shorrock, S. EUROCONTROL; Hollnagel, E.; Leonhardt, J.; Licu, T.; Shorrock, S. From Safety-I to Safety-II: a white paper. EUROCONTROL, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Causes | Contribution Factors | cases | rates | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Overall | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Overall | |||

| 2nd Level Worker, Task Related |

Personnel’s knowledge, experience, abilities | Lack of knowledge | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6.7 % | 6.3 % | 8.6 % | 7.4 % |

| Lack of ability to assess situations | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Task characteristics | Task with insufficient time | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 % | 6.3 % | 8.6 % | 5.6 % | |

| High risk tasks | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| 3rd Level Organization Related |

Characteristics of regulations and business procedures | Absence of rules/procedures | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.7 % | 0 % | 8.6 % | 5.6 % |

| Inaccurate rules/procedures | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Verifying and verifying rules/procedures | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Management of an organization’s human resources | Absence of training/education | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 53.4 % | 68.8 % | 56.5 % | 59.3 % | |

| Lack of education/training | 1 | 6 | 7 | 14 | ||||||

| Inadequate training/education content | 3 | 3 | 4 | 10 | ||||||

| Inadequate evaluation and improvement of training programs | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | ||||||

| Management and supervision issues | Inadequate identification and provision of necessary resources | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 % | 6.3 % | 8.7 % | 11.1 % | |

| Neglect of supervisory action | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | ||||||

| Inadequate accident analysis and hazard identification | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| Organizational processes, policies, and culture | Safety culture | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 13.3 % | 12.5 % | 8.7 % | 11.1 % | |

| Total | 15 | 16 | 23 | 54 | 100 % | 100 % | 100 % | 100 % | ||

| Category | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safety Management Department Response | Proposing superficial solutions that focus on preventing recurrence through enhancement of frontline worker capabilities | Proposing superficial remedial measures that emphasize failure case prevention through improvement of operational personnel competencies | Implementation of superficial mitigation measures, including recurrence prevention through enhancement of frontline worker competencies and adherence to Standard Operating Procedures |

| Safety-I Methodology Analysis Results | Insufficient analytical perspective of safety managers combined with inappropriate education and training methodologies | Insufficient analytical perspective of safety managers combined with inappropriate education and training methodologies | Inadequate management methodology implementation coupled with deficiencies in educational and training protocols |

| Flight Crew’s Resilient Behavior | |

| The repetitive capability to accurately and quickly reconfigure FMS in adverse situations such as setting/changing instrument approach procedures or late runway changes, based on effective learning and high-level understanding of FMS | |

| System to be studied | |

| |

| Pressure (potential or actual) | |

| |

| Learn | Plan |

|

|

| Adapt | Coordinate |

|

|

| Causes | Contribution Factors | Existing (Safety-I Methodology Analysis) |

Improved (Integrated Safety Management) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cases | cases | ||||||||

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Overall | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Overall | ||

| 2nd Level Worker, Task Related |

Personnel’s knowledge, experience, abilities | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Task characteristics | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 3rd Level Organization Related |

Characteristics of regulations and business procedures | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Management of an organization’s human resources | 8 | 11 | 13 | 32 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 13 | |

| Management and supervision issues | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Organizational processes, policies, and culture | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 15 | 16 | 23 | 54 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 19 | |

| Causes | Contribution Factors |

Existing (Safety-I Methodology Analysis) |

Improved (Integrated Safety Management) |

||||||

| rates (%) | rates (%) | ||||||||

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Overall | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Overall | ||

| 2nd Level Worker, Task Related |

Personnel’s knowledge, experience, abilities | 6.7% | 6.3% | 8.7% | 7.4% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 25.0% | 15.8% |

| Task characteristics | 0.0% | 6.3% | 8.7% | 5.6% | 0.0% | 16.7% | 25.0% | 15.8% | |

| 3rd Level Organization Related |

Characteristics of regulations and business procedures | 6.7% | 0.0% | 8.7% | 5.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Management of an organization’s human resources | 53.3% | 68.8% | 56.5% | 59.3% | 80.0% | 83.3% | 50.0% | 68.4% | |

| Management and supervision issues | 20.0% | 6.3% | 8.7% | 11.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Organizational processes, policies, and culture | 13.3% | 12.5% | 8.7% | 11.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).