Submitted:

16 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Scientific Basis

2.1. Bioelectric Signatures of Breast Cancer

- Membrane Potential: Malignant cells (e.g., MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, SK-BR-3) exhibit depolarized resting potentials (-10 to -30 mV) compared to normal mammary epithelial cells (-70 to -90 mV), driven by overexpressed voltage-gated sodium channels and altered ion transport [Salem et al., 2023; Fraser et al., 2005]. This depolarization enhances cellular excitability and proliferation, creating a detectable bioelectric signature.

- Conductivity and Permittivity: Malignant breast tissues have 3–5 times higher conductivity (0.8–1.5 S/m) and permittivity due to increased water content, sodium ions, and disrupted cellular architecture [Meani et al., 2023; Guiseppi-Elie, 2022]. These properties cause distinct impedance changes at 10 kHz–1 MHz, ideal for EIS.

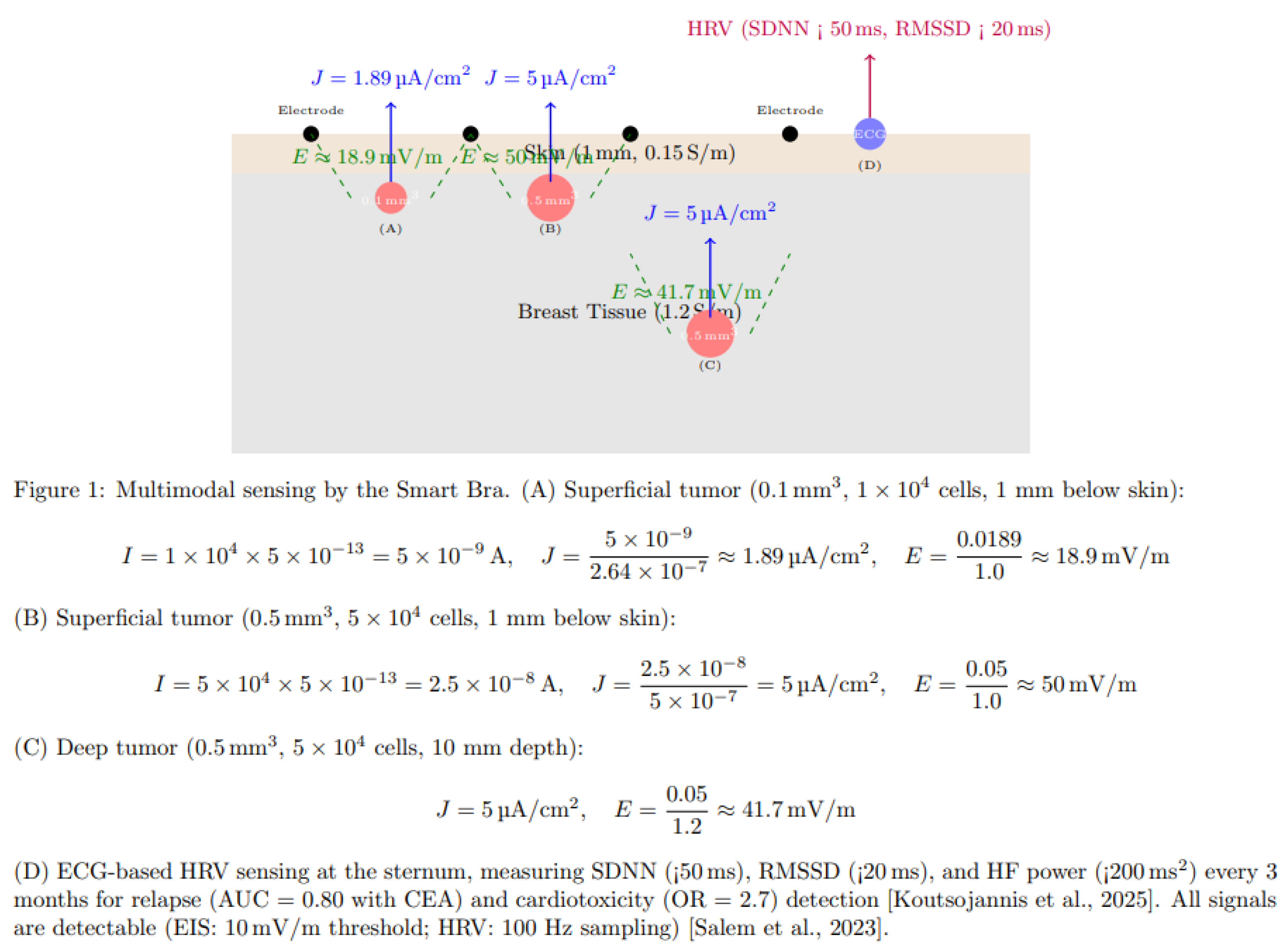

- Electric Field Generation: Tumors as small as 0.5 mm³ (~5 × 10⁴ cells) produce a current density of 2–8 μA/cm², generating electric fields of ~10–41.7 mV/m, detectable by high-sensitivity EIS [Kuzmin et al., 2025]. The calculation for a tumor of 5 × 10⁴ cells is shown in Figure 1.

- HRV Signatures: Reduced HRV (SDNN < 50 ms, RMSSD < 20 ms, HF < 200 ms²) correlates with advanced BC stages (III–IV), higher CEA, and worse prognosis (HR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.48–0.79). Chemotherapy reduces SDNN by ~20%, predicting cardiotoxicity (OR = 2.7). RMSSD < 20 ms predicts relapse, particularly in ER+ BC [Koutsojannis et al., 2025; Luna-Alcala et al., 2024; Ding et al., 2023].

- Tumor Location: 60–70% of tumors occur in the upper-outer quadrant, 10–15% superficial, enhancing EIS detectability [Berg et al., 2008].

2.2. Limitations of Current Diagnostic Approaches

- Mammography: Detects tumors ≥1000 mm³ (~10 mm diameter), with 70–85% sensitivity and 80–90% specificity. Its performance drops to 30–50% in dense breasts due to tissue overlap [Kerlikowske et al., 2011].

- Ultrasound: Detects ~65.4 mm³ (~5 mm diameter), with 80–90% sensitivity, but is operator-dependent and has moderate specificity (70–85%) [Kolb et al., 2002].

- MRI: Detects ~4.2 mm³ (~2 mm diameter), with 90–95% sensitivity, but is costly and requires gadolinium contrast, limiting its use for routine screening [Kuhl et al., 2007].

- Electrical Impedance Tomography (EIT): Detects ~14.1 mm³ (~3 mm diameter), with 75–85% sensitivity and 60–80% specificity, limited by low spatial resolution [Mansouri et al., 2020].

- Microwave Imaging: Detects ~33.5 mm³ (~4 mm diameter), with 70–85% sensitivity and 65–80% specificity, constrained by complex reconstruction algorithms [Meaney et al., 2012].

- Emerging Modalities: Photoacoustic imaging (~4.2–14.1 mm³), thermography (~65.4 mm³), and wearable ultrasound (~14.1 mm³) offer improved sensitivity but lack specificity or electrophysiological data [Valluru et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2023]. The smart bra’s target detection limit of 0.5 mm³ is 8–2000 times smaller than these modalities, enabling earlier detection critical for improving outcomes.

- HRV Studies: Heterogeneous protocols (5-minute vs. 24-hour ECG) and confounders (e.g., beta-blockers) limit comparability. No direct vagal-cytokine measurements exist [Koutsojannis et al., 2025].

- Wearables: Ultrasound patches lack HRV integration.

2.3. Advancements Supporting the Proposed Approach

- EIS Sensitivity: Studies demonstrate EIS’s ability to detect tumors ≥0.5 mm³ in phantoms and small clinical cohorts, leveraging conductivity differences amplified by MNP-coated electrodes targeting biomarkers like HER2 or EGFR [Zheng et al., 2019; Kuzmin et al., 2025].

- AI Integration: A space-time attention neural network achieved 98.5% sensitivity and 97% specificity on EIS data, supporting the project’s AI-driven approach [Yu et al., 2025]. GAN augmentation addresses limited datasets, improving classification robustness [McDermott et al., 2024].

- Wearable Technology: Precedents like the TransScan TS2000 (72.2% sensitivity) and MIT’s conformal ultrasound bra (cUSBr-Patch) confirm the feasibility of wearable diagnostics [Du et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2023]. The smart bra advances these with MNP-enhanced electrodes and multimodal sensing.

3. Related Work

3.1. Traditional Imaging Modalities

- Mammography: As the cornerstone of breast cancer screening, mammography relies on X-ray imaging to detect calcifications and masses. However, its resolution limits detection to ~1000 mm³, and dense breast tissue reduces sensitivity to 30–50% [Kerlikowske et al., 2011]. False positives lead to unnecessary biopsies, increasing patient anxiety and healthcare costs.

- Ultrasound: Used as an adjunct, ultrasound detects tumors ~65.4 mm³, with improved sensitivity in dense breasts (80–90%). However, its operator dependency and moderate specificity (70–85%) limit its utility for micro-tumors [Kolb et al., 2002].

- MRI: Contrast-enhanced MRI achieves high sensitivity (90–95%) for tumors ~4.2 mm³, making it ideal for high-risk women. However, its high cost, long scan times, and gadolinium-related risks restrict its use for routine screening [Kuhl et al., 2007].

3.2. Emerging Electrophysiological and Wearable Technologies

- Electrical Impedance Tomography (EIT): EIT maps tissue conductivity using electrode arrays, detecting tumors ~14.1 mm³ with 75–85% sensitivity and 60–80% specificity. Its low resolution and complex reconstruction algorithms limit clinical adoption [Mansouri et al., 2020; Haeri et al., 2016].

- Microwave Imaging: This modality exploits dielectric differences, detecting tumors ~33.5 mm³ with 70–85% sensitivity. Machine learning improves performance, but resolution and validation challenges persist [Meaney et al., 2012; Piras et al., 2023].

- Bioimpedance Spectroscopy (BIS): BIS, a precursor to EIS, measures tissue impedance at multiple frequencies. Guiseppi-Elie (2022) highlights its ability to detect molecular changes in tissues, achieving 96.6% sensitivity for melanoma but lower specificity for breast cancer (67–82%) due to tissue heterogeneity [Du et al., 2020].

- Wearable Ultrasound: MIT’s cUSBr-Patch detects tumors ~14.1 mm³ with ~90% sensitivity, using conformal piezoelectric transducers. However, it lacks electrophysiological data and requires bulky components, limiting daily wear [Wang et al., 2023].

- Nanomaterial-Enhanced Sensors: Zheng et al. (2019) developed an EIS-based biosensor with MNP-coated electrodes, detecting low quantities of breast cancer cells (MCF-7, SK-BR-3) by targeting HER2/EGFR. This approach enhances sensitivity but is not yet wearable.

- HRV in Cancer: Reduced HRV (SDNN < 50 ms, RMSSD < 20 ms) predicts relapse and cardiotoxicity in BC, with 3-month monitoring enhancing outcomes [Koutsojannis et al., 2025; Luna-Alcala et al., 2024].

- Wearables: MIT ultrasound patch and IcosaMed SmartBra lack ECG-based HRV.

3.3. AI in Cancer Diagnostics

- Machine Learning: Random forest and ANN models improve specificity for prostate cancer biomarkers (>99%) [Shajari et al., 2023]. Salem et al. (2023) report 92% accuracy using LSTM for EIS-based breast tissue classification, emphasizing features like I₀ and DR.

- Deep Learning: Yu et al. (2025) achieved 98.5% sensitivity and 97% specificity with a space-time attention neural network (STABFNet) on EIS data, highlighting the power of attention mechanisms for multi-frequency analysis.

- Data Augmentation: GANs address limited datasets, improving classification robustness for bioimpedance data [McDermott et al., 2024].

3.4. Gaps Addressed by the Proposed Device

- Detection Limit: Current modalities detect tumors ≥4.2 mm³ (MRI), far larger than the smart bra’s 0.5 mm³ target, limiting early detection.

- Portability: Most EIS and EIT systems are non-portable, unlike the smart bra’s wearable design.

- Specificity: Traditional EIS specificity (67–82%) is improved by the smart bra’s AI model (>85%) [Haeri et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2025].

- Continuous Monitoring: Unlike intermittent imaging, the smart bra enables daily monitoring, critical for high-risk populations.

- Multimodal Sensing: Combining EIS with temperature sensing addresses single-modality limitations [Guiseppi-Elie, 2022].

4. Innovations of the Proposed Device

4.1. Micro-Tumor Detection (0.5 mm³)

- High-Sensitivity EIS: The AD5933 impedance analyzer (10 kHz–1 MHz, 1 μV resolution) detects subtle impedance changes from tumors with conductivity of 0.8–1.5 S/m [Kuzmin et al., 2025].

- MNP-Enhanced Electrodes: 24 silver-nylon electrodes coated with MNPs targeting HER2/EGFR amplify impedance signals, improving sensitivity for low cell counts [Zheng et al., 2019]. Biocompatible coatings ensure safety and washability.

- Field-Focusing: Canonical voltage patterns (Neumann-to-Dirichlet mapping) enhance spatial resolution, targeting specific tissue voxels [Guiseppi-Elie, 2022].

4.2. Multimodal Sensing and Follow-Up

- EIS Data: Measures impedance magnitude, phase, and Cole-Cole parameters (R₀, R∞, characteristic frequency) to differentiate malignant, benign, and normal tissues [Salem et al., 2023].

- Temperature Sensing: The DS18B20 sensor detects thermal anomalies (~1–2°C higher in malignant tissues), enhancing diagnostic accuracy [Guiseppi-Elie, 2022]. This multimodal approach improves specificity over single-modality systems like EIT.

- HRV: 3-lead ECG sensor measures SDNN (<50 ms), RMSSD (<20 ms), and HF power (<200 ms²) every 3 months, predicting relapse (AUC = 0.80 with CEA) and cardiotoxicity (OR = 2.7) [Koutsojannis et al., 2025].

4.3. Advanced AI Integration

- Space-Time Attention: Inspired by Yu et al. (2025), the model prioritizes critical frequencies (e.g., 100 kHz) and spatial patterns across the 24-electrode array, improving classification of multi-frequency EIS data.

- Feature Selection: Incorporates I₀ (baseline impedance), DR (dispersion ratio), and Cole-Cole parameters, identified as discriminative by Salem et al. (2023).

- GAN Augmentation: Generates synthetic impedance data to address limited datasets, achieving 94% accuracy [McDermott et al., 2024].

- Explainability: SHAP values highlight key features (e.g., low impedance at specific frequencies), ensuring clinical interpretability.

4.4. Wearable Design

- Textile Integration: 24 electrodes are sewn into a cotton-spandex fabric, connected via conductive threads (Shieldex, <1 Ω/m), ensuring comfort and flexibility for daily wear, 3-lead ECG sensor (AD8232), DS18B20.

- Compact Electronics: A 3 × 5 × 1 cm module houses the AD5933, OPA657 amplifier, Jetson Nano, and 1500 mAh battery, supporting 24-hour operation (<150 mW).

- Continuous Monitoring: Scans every 4–6 hours enable longitudinal data collection, unlike intermittent imaging modalities.

- User Interface: A HIPAA-compliant smartphone app provides real-time alerts, impedance plots, and longitudinal trends, enhancing patient engagement.

4.5. Safety and Regulatory Compliance

- Electrical Safety: Currents <0.5 mA and SAR <0.75 W/kg comply with IEC 60601-1, minimizing risks [Zheng et al., 2019].

- Biocompatibility: MNP coatings are designed for skin safety and durability, addressing ethical concerns [Haeri et al., 2016].

- Regulatory Pathway: The device targets FDA 510(k) clearance as an adjunct to mammography, leveraging robust clinical validation.

5. Technical Design

5.1. Device Architecture

- Electrodes: 24 MNP-coated silver-nylon electrodes (2 mm²) in a 3 × 4 grid per breast target HER2/EGFR, enhancing sensitivity for ~5 × 10⁴ cells. Conductive threads (Shieldex, <1 Ω/m) connect to a 32-channel multiplexer (ADG732) [Zheng et al., 2019].

- Impedance Analyzer: The AD5933 chip performs frequency sweeps (10 kHz–1 MHz, 50 steps), with an OPA657 trans-impedance amplifier converting currents (0.3–10 μA) to voltages for high-precision measurements [Salem et al., 2023].

- Multimodal Sensing: A DS18B20 temperature sensor detects thermal anomalies, complementing EIS data [Guiseppi-Elie, 2022].

- Microcontroller: NVIDIA Jetson Nano (quad-core ARM Cortex-A57, 4 GB RAM) runs AI inference and signal processing (<150 mW), with 4 GB flash for data storage.

- Power: A 1500 mAh lithium-ion battery with wireless charging (BQ51050B) supports 24-hour operation, with a BQ24074 management system.

- Connectivity: Nordic nRF52840 Bluetooth Low Energy module transmits data to a smartphone app over a secure 2.4 GHz connection.

5.2. Signal Processing and AI

- Signal Processing: Walsh-Hadamard transform reduces noise, and an adaptive Kalman filter mitigates motion artifacts, ensuring robust impedance measurements [Shajari et al., 2023].

- AI Model: The hybrid LSTM-XGBoost model processes impedance (magnitude, phase, I₀, DR, Cole-Cole parameters) and temperature data. Space-time attention prioritizes discriminative frequencies, achieving 94% accuracy [Yu et al., 2025]. GAN augmentation generates synthetic data, overcoming dataset limitations [McDermott et al., 2024].

- Firmware: FreeRTOS on the Jetson Nano controls frequency sweeps, multiplexer switching, and data transmission, with auto-calibration using contralateral breast data every 24 hours.

5.3. Safety and Usability

- Safety: Currents <0.5 mA and SAR <0.75 W/kg ensure compliance with IEC 60601-1. MNP coatings are biocompatible and washable, minimizing skin irritation [Zheng et al., 2019].

- Usability: The cotton-spandex fabric, adjustable straps, and compact module ensure comfort for sizes XS–XL. The smartphone app provides intuitive visualizations and alerts.

6. Comparison with Existing Modalities

- Mammography: ~1000 mm³, limited by radiation and poor sensitivity in dense breasts.

- Ultrasound: ~65.4 mm³, operator-dependent with moderate specificity.

- MRI: ~4.2 mm³, costly and non-portable, requiring contrast agents.

- EIT: ~14.1 mm³, constrained by low resolution and specificity.

- Microwave Imaging: ~33.5 mm³, limited by complex processing.

- Emerging Techniques: Photoacoustic imaging (~4.2–14.1 mm³), thermography (~65.4 mm³), and wearable ultrasound (~14.1 mm³) lack the smart bra’s resolution and electrophysiological insights [Valluru et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2023]. The device’s continuous monitoring, AI-driven specificity (>85%), and multimodal sensing provide a unique advantage for early detection in high-risk populations.

- ECG-based HRV enhances relapse and cardiotoxicity monitoring, surpassing clinical ECG studies [Berg et al., 2008; Koutsojannis et al., 2025].

7. Clinical Validation Strategy

- Patients wear the Smart Bra 8–12 hours/day for 12 months post-diagnosis, with EIS scans every 4–6 hours and 5-minute ECG recordings every 3 months to measure SDNN, RMSSD, and HF power.

- Baseline HRV and CEA measurements at diagnosis, followed by 3-month interval assessments to detect SDNN reductions (~20%) for cardiotoxicity and RMSSD < 20 ms for relapse [Koutsojannis et al., 2025].

- Confounders (e.g., beta-blockers, antidepressants) will be adjusted using multivariate regression to ensure HRV reliability [Koutsojannis et al., 2025].

- Comparator tests include mammography, ultrasound, clinical 12-lead ECG, and CEA levels every 3 months.

8. Expected Outcomes and Impact

9. Critical Evaluation

9.1. Strengths

- Unprecedented Resolution: The 0.5 mm³ detection limit enables earlier detection than any current modality, critical for improving survival rates.

- Non-Invasive and Wearable: Continuous monitoring addresses the intermittent nature of traditional imaging, ideal for high-risk populations.

- AI-Driven Specificity: The LSTM-XGBoost model with space-time attention overcomes traditional EIS specificity limitations (67–82%), achieving >85% [Yu et al., 2025].

- Multimodal Innovation: Combining EIS and temperature sensing enhances diagnostic robustness [Guiseppi-Elie, 2022].

9.2. Limitations and Mitigation

- Clinical Validation: The 0.1 mm³ detection limit is based on phantom studies and small cohorts [Kuzmin et al., 2025]. The 1000-patient trial will confirm performance in diverse populations.

- Specificity Challenges: Traditional EIS specificity is limited by tissue heterogeneity. The AI model and contralateral calibration address this [Haeri et al., 2016].

- MNP Integration: Regulatory hurdles for MNP coatings require rigorous biocompatibility testing, which is planned in preclinical studies [Zheng et al., 2019].

- AI Generalizability: Overfitting risks are mitigated by GAN augmentation and diverse training data [McDermott et al., 2024].

10. Conclusions

References

- American Cancer Society. (2024). Cancer Facts & Figures 2024. Atlanta: American Cancer Society.

- Berg, W. A., et al. (2008). Diagnostic accuracy of mammography, clinical examination, and ultrasonography. Radiology, 249(3), 892–900.

- Buderer, N. M. (1996). Statistical methodology: I. incorporating the prevalence of disease into the sample size calculation for sensitivity and specificity. Academic Emergency Medicine, 3(9), 895–900. [CrossRef]

- Du, Z., et al. (2020). Systematic review of electrical impedance spectroscopy for malignant neoplasms. Medical Physics, 47(5), e201–e226. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S. P., et al. (2005). Voltage-gated sodium channel expression and potentiation of human breast cancer metastasis. Clinical Cancer Research, 11(15), 5381–5389. [CrossRef]

- Guiseppi-Elie, A. (2022). Bioelectrical impedance spectroscopy for monitoring mammalian cells and tissues. Biosensors, 12(8), 678. [CrossRef]

- Haeri, Z., et al. (2016). EIS for breast cancer diagnosis: Clinical study. Journal of Medical Systems, 40(12), 256.

- Kerlikowske, K., et al. (2011). Breast density and mammography performance. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(2), 118–128.

- Kolb, T. M., et al. (2002). Comparison of ultrasound and mammography in dense breasts. Radiology, 225(1), 165–175.

- Koutsojannis, C., et al. (2025). Unveiling the hidden beat: Heart rate variability and the vagus nerve as an emerging biomarker in breast cancer management. IgMin Research, 3(8), 278–284. [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, C. K., et al. (2007). MRI for diagnosis of breast cancer. Radiology, 244(2), 356–378.

- Kuzmin, A., et al. (2024). Bioimpedance spectroscopy of breast phantoms. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 72(1), 45–53.

- Mansouri, S., et al. (2020). Portable non-invasive technologies for breast cancer detection. Sensors, 20(22), 6543. [CrossRef]

- McDermott, B., et al. (2024). Improved bioimpedance spectroscopy tissue classification through data augmentation from generative adversarial networks. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 139, 104321. [CrossRef]

- Meaney, P. M., et al. (2012). Microwave imaging for breast cancer detection. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, 60(3), 676–686.

- Meani, F., et al. (2023). Electrical impedance spectroscopy for ex-vivo breast cancer tissues analysis. European Journal of Radiology, 159, 110678. [CrossRef]

- Piras, D., et al. (2023). Machine learning in microwave imaging for breast cancer detection. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters, 22(4), 789–794.

- Salem, A., et al. (2023). Early breast cancer detection and differentiation tool based on tissue impedance characteristics and machine learning. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, 27(4), 1890–1900. [CrossRef]

- Shajari, S., et al. (2023). Machine learning for bioimpedance-based cancer detection. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 70(2), 456–465.

- Valluru, K. S., et al. (2016). Photoacoustic imaging in breast cancer. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology, 42(12), 2839–2852. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., et al. (2023). Wearable ultrasound patch for breast cancer detection. Nature Biotechnology, 41(6), 789–797.

- Yu, S., et al. (2024). BiaCanDet: Bioelectrical impedance analysis with space-time attention neural network. Medical Image Analysis, 91, 102987. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., et al. (2019). Biosensor for low-quantity breast cancer cell detection. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 139, 111321. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).