Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Highlights

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

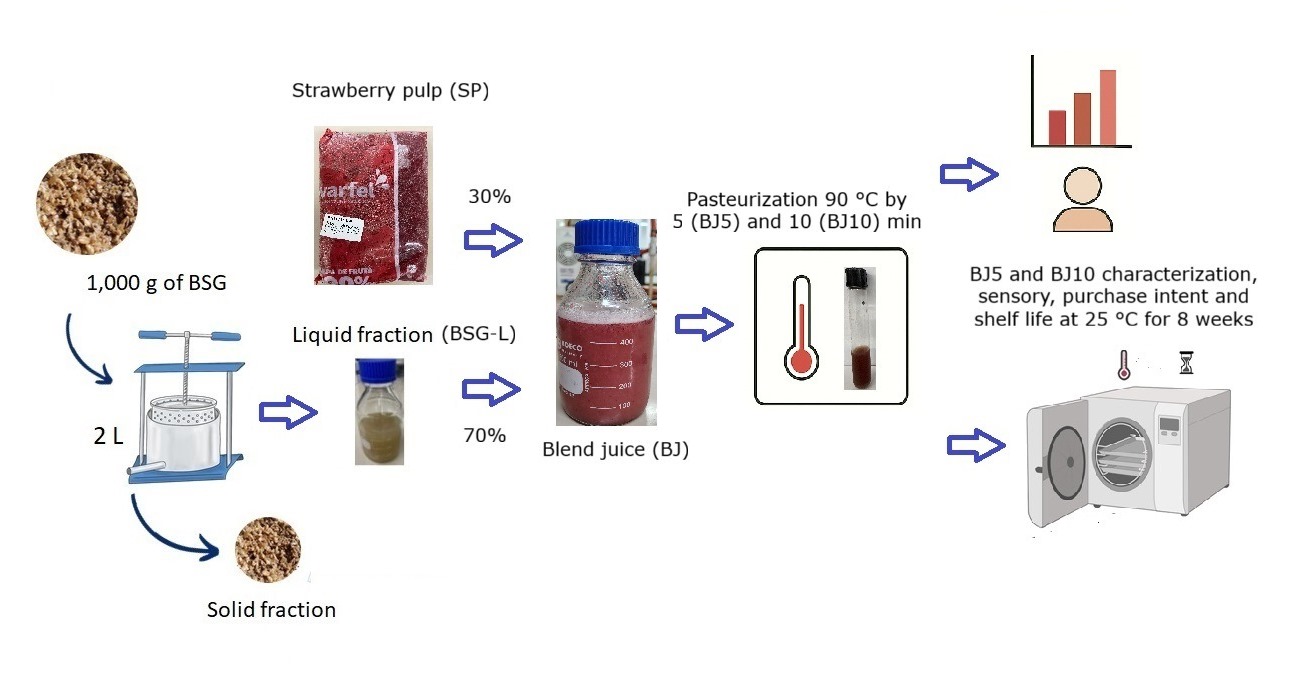

2.1. BSG Liquid Fraction, Strawberry Pulp and Blend Juice

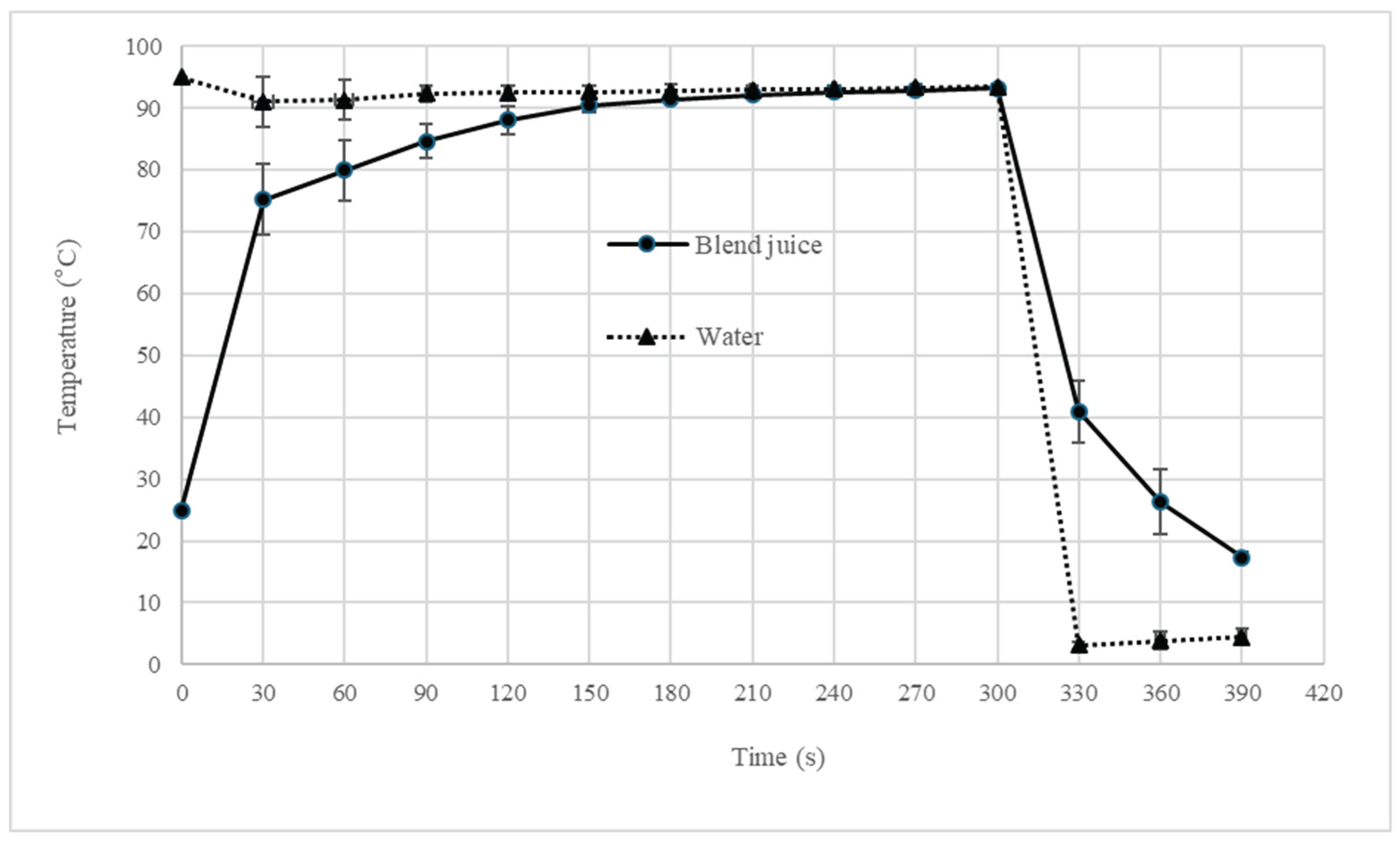

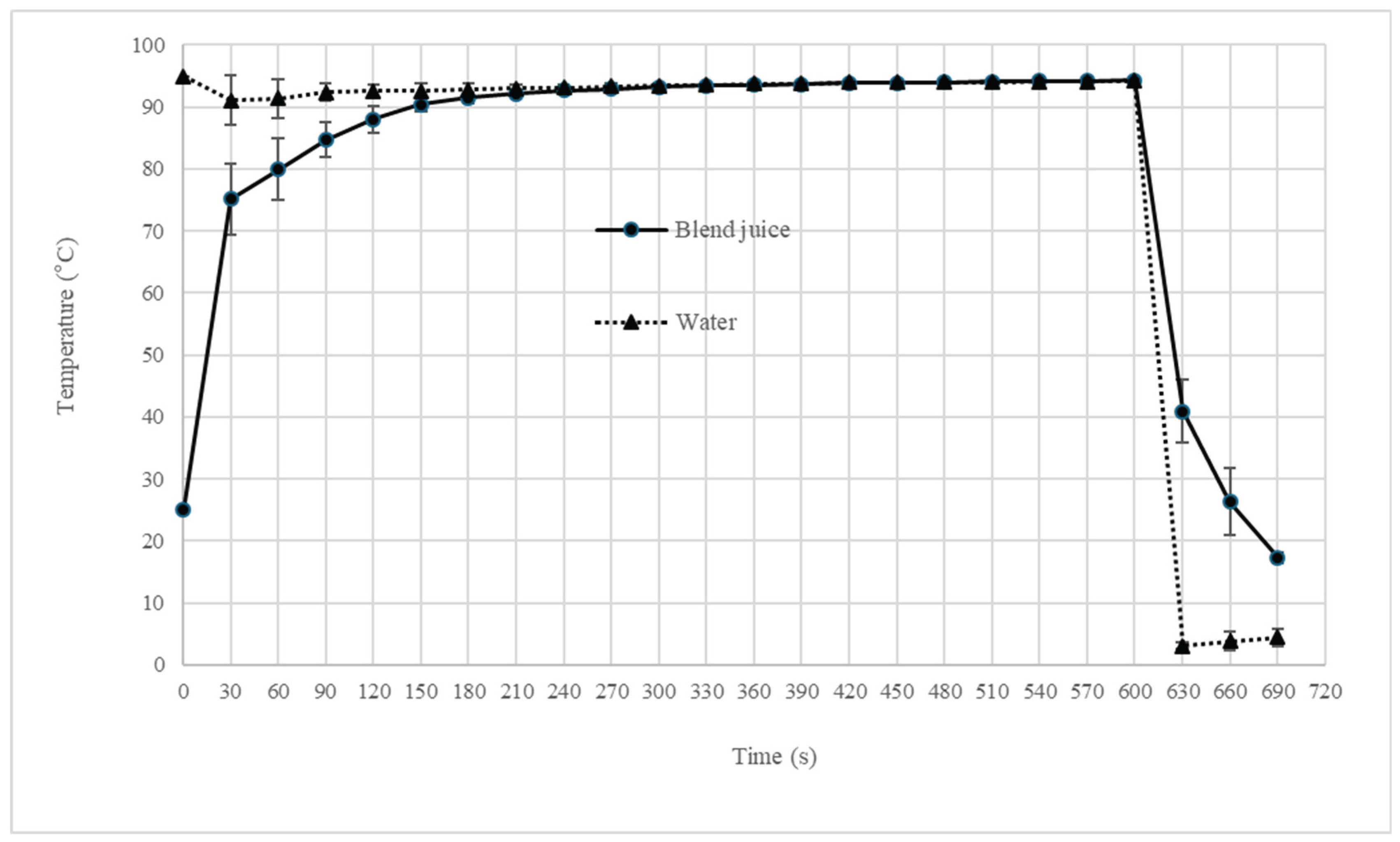

2.2. Blend Juice Pasteurization

2.3. Shelf-Life of Pasteurized Blend Juice

2.4. Analysis

2.4.1. Moisture Content

2.4.2. Instrumental Color

2.4.3. Soluble Solids

2.4.4. Reducing Sugar Content

2.4.5. pH

2.4.6. Titratable Acidity (TA)

2.4.7. Total Polyphenol Content (TPC)

2.4.8. Ascorbic Acid Content

2.4.9. Microbiology Determination

2.5. Sugar Characterization by HPLC

2.6. Sensory Evaluation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of BSG Liquid Fraction, Strawberry Pulp and Blend Juice

3.2. Effect of Pasteurization on Blend Juice

| Sample | Color | Appearance | Consistency | Aroma | Taste | Overall Acceptance |

Purchase Intent |

| BJ | 7.2 ± 1.3 a | 6.5 ± 1.4 a | 6.9 ± 1.1 a | 6.8 ± 1.4 a | 7.2 ± 1.5 a | 6.7 ± 1.5 a | 6.7 ± 1.5 a |

| BJ5 | 7.0 ± 1.5 a | 6.1 ± 1.8 a | 6.5 ± 1.4 a | 6.6 ± 1.6 a | 6.9 ± 1.6 ab | 6.7 ± 1.5 a | 6.5 ± 1.3 a |

| BJ10 | 6.7 ± 1.6 ab | 6.0 ± 2.0 a | 6.7 ± 1.3 a | 6.5 ± 1.4 a | 6.5 ± 1.2 ab | 6.6 ± 1.4 a | 6.2 ± 1.7 a |

| FS | 5.7 ± 1.7 b | 5.8 ± 1.6 a | 6.8 ± 1.6 a | 6.5 ± 1.6 a | 5.8 ± 1.8 b | 6.2 ± 1.8 a | 5.6 ± 2.3 a |

| AFE | 6.4 ± 2.0 ab | 6.2 ± 2.2 a | 6.8 ± 1.5 a | 6.2 ± 1.4 a | 6.3 ± 1.6 ab | 6.2 ± 1.7 a | 5.7 ± 2.1 a |

3.3. Shelf Life of Pasteurized Blend Juice

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lynch, K.M.; Steffen, E.J.; Arendt, E.K. Brewers’ spent grain: A review with an emphasis on food and health. J. Inst. Brew. 2016, 122, 553–568. [CrossRef]

- Naibaho, J.; Korzeniowska, M.; Sitanggang, A.B.; Lu, Y.; Julianti, E. Brewers’ spent grain as a food ingredient: techno-processing properties, nutrition, acceptability, and market. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 152, 104685. [CrossRef]

- Ravanal, M.C.; Doussoulin, J.P.; Mougenot, B. Does sustainability matter in the global beer industry? Bibliometrics trends in recycling and the circular economy. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1437910. [CrossRef]

- Verni, M.; Pontonio, E.; Krona, A.; Jacob, S.; Pinto, D.; Rinaldi, F.; Verardo, V.; Díaz-de-Cerio, E.; Coda, R.; Rizzello, C.G. Bioprocessing of brewers’ spent grain enhances its antioxidant activity: characterization of phenolic compounds and bioactive peptides. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1831. [CrossRef]

- Finley, J.W.; Walkera, C.E.; Hautala, E. Utilisation of press water from brewer’s spent grains. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1976, 27, 655–660. [CrossRef]

- El-Shafey, E.I.; Gameiro, M.L.F.; Correia, P.F.M.; De Carvalho, J.M.R. Dewatering of brewer’s spent grain using a membrane filter press: a pilot plant study. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2004, 39, 3237–3261. [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.M.; Rodrigues, R.A.D.; Henriques, C.M.C.; Gameiro, M.L.F.; Ismael, M.R.C.; Reis, M.T.A.; Freire, J.P.B.; Carvalho, J.M.R. Dewatering of brewer’s spent grain using an integrated membrane filter press with vacuum drying capabilities. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 692–700. [CrossRef]

- Ruíz, C.; Schalchli, H.; Melo, P.S.; Moreira, C.d.S.; Sartori, A.d.G.O.; de Alencar, S.M.; Scheuermann, E.S. Effect of physical separation with ultrasound application on brewers’ spent grain to obtain powders for potential application in foodstuffs. Foods 2024, 13, 300. [CrossRef]

- Madsen, S.K.; Priess, C.A.P.; Wätjen, S.; Øzmerih, M.A.; Mohammadifar, C.; Bang-Berthelsen, H. Development of a yoghurt alternative, based on plant-adapted lactic acid bacteria, soy drink and the liquid fraction of brewers' spent grain. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2021, 368, fnab093. [CrossRef]

- Akermann, A.; Weiermüller, J.; Christmann, J.; Guirande, L.; Glaser, G.; Knaus, A.; Ulber, R. Brewers’ spent grain liquor as a feedstock for lactate production with Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis. Eng. Life Sci. 2019, 20, 168-180. [CrossRef]

- Shetty, R.; Petersen, F.R.; Podduturi, R.; Molina, G.E.S.; Wätjen, A.P.; Madsen, S.K.; Zioga, E.; Øzmerih, S.; Hobley, T.J.; Bang-Berthelsen, C.H. Fermentation of brewer's spent grain liquids to increase shelf life and give an organic acid enhanced ingredient. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 182, 114911. [CrossRef]

- Bjerregaard, M.F.; Charalampidis, A.; Frøding, R.; Shetty, R.; Pastell, H.; Jacobsen, C.; Zhuang, S.; Pinelo, M.; Hansen, P.B.; Hobley, T.J. Processing of brewing by-products to give food ingredient streams. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 245, 545–558. [CrossRef]

- Herbst, G.; Hamerski, F.; Errico, M.; Corazza, M.L. Pressurized liquid extraction of brewer’s spent grain: kinetics and crude extracts characterization. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 102, 370-383. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. C.; Lee S. H. Flavor quality of concentrated strawberry pulp with aroma recovery. J. Food Qual. 1992, 1992, 15321-332. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, G.A.S.; Resende, N.S.; Carvalho, E.E.N.; de Resende, J.V.; Vilas Boas, E.V. de B. Effect of pasteurisation and freezing method on bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of strawberry pulp. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 68, 682-694. [CrossRef]

- López-Ortiz, A.; Salgado, M.N.; Nair, P.K.; Balbuena, A.O.; Méndez-Lagunas, L. L.; Hernández-Díaz, W.N.; Guerrero, L.L. Improved preservation of the color and bioactive compounds in strawberry pulp dried under UV-Blue blocked solar radiation. Clean. Circ. Bioeconomy 2024, 9, 100112. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, G.S.; Wu, X.; Patterson, K.M.; Barnes, J.; Carter, S.G. In vitro and in vivo antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capacities of an antioxidant-rich fruit and berry juice blend. Results of a pilot and randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover study. J. Agric. Food Chem 2008, 56, 8326-8333. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, G.S.; Ager, D.M.; Redman, K.A.; Mitzner, M.A.; Benson, K.F. Pain reduction and improvement in range of motion after daily consumption of an açai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) pulp-fortified polyphenolic-rich fruit and berry juice blend. J. Med. Food 2011, 14, 702-711. [CrossRef]

- Atef, A.M.; Nadir, A.S.; Mostafa, T.R. Studies on sheets properties made from juice and puree of pumpkin and some other fruit blends. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2012, 8, 2632-2639.

- Salgado, J.M.; Ferreira, T.R.B.; Biazotto, F.O.; Dias, C.T.S. Increased antioxidant content in juice enriched with dried extract of pomegranate (Punica granatum) peel. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2012, 67, 39–43. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Bi, X.; Ma, Y. Comparison of high hydrostatic pressure, ultrasound, and heat treatments on the quality of strawberry–apple–lemon juice blend. Foods 2020, 9, 218. [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Zheng, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Yang, N.; Xu, X.; Jin, Y.; Meng, M.; Wang, F. Induced electric field as alternative pasteurization to improve microbiological safety and quality of bayberry juice. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141137. [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Salud Pública de Chile. Manual Métodos de Análisis Físico-químicos de Alimentos, Aguas y Suelo; Andros Ltda.: Santiago, 1998a; pp. 13–14.

- Ihl, M.; Aravena, L.; Scheuermann, E.; Uquiche, E.; Bifani, V. Effect of immersion solutions on shelf-life of minimally processed lettuce. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2003, 36, 591–599. [CrossRef]

- Pathare, P.B.; Opara, U.L.; Al-Said, F.A.J. Colour measurement and analysis in fresh and processed foods: A review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 36–60. [CrossRef]

- Adekunte, A.; Tiwari, B.; Cullen, P.; Scannell, A.; O’Donnell, C. Effect of sonication on colour, ascorbic acid and yeast inactivation in tomato juice. Food Chem. 2010, 122, 500–507. [CrossRef]

- Scheuermann, E.; Ihl, M.; Beraud, L.; Quiroz, A.; Salvo, S.; Alfaro, S.; Bustos, R.O.; Seguel, I. Effects of packaging and preservation treatments on the shelf life of murtilla fruit (Ugni molinae Turcz) in cold storage. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2013, 27, 241–248. [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.L. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426-428. [CrossRef]

- Pirce, F.; Vieira, T.M.F.S.; Augusto-Obara, T.R.; de Alencar, S.M.; Romero, F.; Scheuermann, E. Effects of convective drying assisted by ultrasound and osmotic solution on polyphenol, antioxidant and microstructure of murtilla (Ugni molinae Turcz) fruit. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 138–146. [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Salud Pública de Chile. Manual de Técnicas Microbiológicas para Alimentos y Aguas; Andros Ltda.; Santiago, Chile, 1998b; pp. 14–17.

- Choo, Y.X.; Teh, L.K.; Tan, C.X. Effects of sonication and thermal pasteurization on the nutritional, antioxidant, and microbial properties of noni juice. Molecules 2023, 28, 313. [CrossRef]

- Lepaus, B.M.; Santos, A.K.P.d.O.; Spaviero, A.F.; Daud, P.S.; de São José, J.F.B. Thermosonication of orange-carrot juice blend: overall quality during refrigerated storage, and sensory acceptance. Molecules 2023, 28, 2196. [CrossRef]

- Cendrowski, A.; Przybył, J.L.; Studnicki, M. Physicochemical characteristics, vitamin C, total polyphenols, antioxidant capacity, and sensory preference of mixed juices prepared with rose fruits (Rosa rugosa) and apple or strawberry. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 113. [CrossRef]

- Carciochi, R.A.; Sologubik, C.A.; Fernández, M.B.; Manrique, G.D.; D’Alessandro, L.G. Extraction of antioxidant phenolic compounds from brewer’s spent grain: optimization and kinetics modeling. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 45. [CrossRef]

- Meneses, N.G.T.; Martins, S.; Teixeira, J.A.; Mussatto, S.I. Influence of extraction solvents on the recovery of antioxidant phenolic compounds from brewer’s spent grains. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 108, 152–158. [CrossRef]

- Bonifácio-Lopes, T.; Castro, L.M.G.; Vilas-Boas, A.; Campos, D.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pintado, M. Impact of gastrointestinal digestion simulation on brewer’s spent grain green extracts and their prebiotic activity. Food Res. Int. 2023, 165, 112515. [CrossRef]

- Ogundele, O.M.A.; Awolu, O.O.; Badejo, A.A.; Nwachukwu, I.D.; Fagbemi, T.N. Development of functional beverages from blends of Hibiscus sabdariffa extract and selected fruit juices for optimal antioxidant properties. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 4, 679–685. [CrossRef]

- Prandi, B.; Ferri, M.; Monari, S.; Zurlini, C.; Cigognini, I.; Verstringe, S.; Schaller, D.; Walter, M.; Navarini, L.; Tassoni, A.; Sforza, S.; Tedeschi, T. Extraction and chemical characterization of functional phenols and proteins from coffee (Coffea arabica) by-products. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1571. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.A.; I'Anson, K.J.; Treimo, J.; Faulds, C.B.; Brocklehurst, T.F.; Eijsink, V.G.H.; Waldron, K.W. Profiling brewers’ spent grain for composition and microbial ecology at the site of production. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 43, 890–896. [CrossRef]

- Basiony, M.; Saleh, A.; Hassabo, R.; AL-Fargah, A. The effect of using pomegranate and strawberry juices with red beet puree on the physicochemical, microbial and sensory properties of yoghurt. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 5024–5033. [CrossRef]

- EL Moutaouakil, S.; EL Madhi, Y.; Inekach, S.; Chauiyakh, O.; Nabil, Benzakour, A.; Ouhssine, M. Evaluation of the physicochemical and microbiological quality of strawberry pulp in a moroccan food industry company. RJPT. 2024, 17, 2505-2509.

- Radziejewska-Kubzdela, E. Effect of ultrasonic, thermal and enzymatic treatment of mash on yield and content of bioactive compounds in strawberry juice. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4268. [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, F.; Ren, D.; Kanwal, W.; Ding, M.; Su, J.; Shang, X. The potential role of nondigestible raffinose family oligosaccharides as prebiotics. Glycobiology 2023, 33, 274–288. [CrossRef]

- Mandha, J.; Shumoy, H.; Matemu, A.O.; Raes, K. Characterization of fruit juices and effect of pasteurization and storage conditions on their microbial, physicochemical, and nutritional quality. Food Biosci. 2023, 51, 102335. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | BSG-LF | SP | BJ |

| Moisture content (%, w.b.) | 87.0 ± 0.1 a | 69.2 ± 0.1 c | 82.4 ± 0.1 b |

| Color | |||

| L* | 43.7 ± 4.3 a | 30.1 ± 0.6 b | 34.4 ± 0.4 b |

| a* | 0.2 ± 0.3 c | 15.9 ± 0.8 a | 8.9 ± 0.1 b |

| b* | 12.9 ± 0.2 a | 11.4 ± 0.4 b | 10.6 ± 0.5 b |

| ΔE | 13.2 ± 2.9 a | 8.4 ± 0.4 a | - |

| Soluble solid (° Brix) | 13.5 ± 0.1 c | 29.1 ± 0.1 a | 17.2 ± 0.2 b |

| Reducing sugar (g 100 g-1 d.m.) | 65.6 ± 1.3 a | 20.9 ± 0.1 c | 47.4 ± 0.8 b |

| pH | 6.26 ± 0.09 a | 3.64 ± 0.16 c | 4.28 ± 0.03 c |

| Titratable acidity (%) | 0.065 ± 0.007 c | 0.663 ± 0.067 a | 0.243 ± 0.002 b |

| TPC (mg GAE 100 g-1 d.m.) |

169.4 ± 13.2 b | 256.6 ± 10.3 a | 181.2 ± 3.3 b |

| Ascorbic acid (mg 100 g-1 d.m.) | < 16,7 | 30.9 ± 3.2 a | 23.2 ± 1.5 b |

| Microbiology | |||

| AMB (log CFU mL-1) | 4.8 ± 0.1 a | Absent | 3.5 ± 0.0 b |

| YM (log CFU mL-1) | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Sample | Fructose | Glucose | Maltose | Raffinose |

| BSG-LF | n.d. | 12.16 ± 0.16 d | 61.83 ± 0.72 a | 17.14 ± 0.39 a |

| SP | 28.50 ± 0.76 a | 31.05 ± 1.12 a | n.d. | n.d. |

| BJ | 11.22 ± 0.70 b | 23.87 ± 0.54 b | 34.58 ± 1.06 b | 11.84 ± 1.20 b |

| BJ5 | 10.44 ± 0.42 b | 19.26 ± 0.46 c | 31.75 ± 0.96 c | 10.92 ± 0.86 b |

| BJ10 | 11.19 ± 0.64 b | 20.82 ± 1.02 c | 34.50 ± 1.68 b | 11.48 ± 0.61 b |

| Parameter | BJ | BJ5 | BJ10 |

| Moisture content (%, w.b.) | 82.4 ± 0.1 a | 81.9 ± 0.1 b | 81.7 ± 0.1 b |

| Color | |||

| L* | 34.4 ± 0.4 a | 33.5 ± 0.6 a | 33.9 ± 1.0 a |

| a* | 8.9 ± 0.1 a | 8.7 ± 0.6 a | 8.7 ± 0.7 a |

| b* | 10.6 ± 0.5 a | 9.4 ± 0.8 a | 9.9 ± 0.7 a |

| ΔE | - | 1.7 ± 0.5 a | 1.2 ± 0.3 a |

| Soluble solid (° Brix) | 17.2 ± 0.2 b | 17.7 ± 0.2 a | 18.0 ± 0.0 a |

| Reducing sugar (g 100 g-1 d.m.) | 47.4 ± 0.8 a | 48.9 ± 2.9 a | 49.4 ± 3.4 a |

| pH | 4.28 ± 0.03 a | 4.18 ± 0.02 ab | 4.14 ± 0.07 b |

| Titratable acidity (%) | 0.243 ± 0.002 a | 0.259 ± 0.031 a | 0.260 ± 0.030 a |

| TPC (mg GAE 100 g-1 d.m.) |

181.2 ± 3.3 ab | 172.8 ± 4.4 b | 186.8 ± 1.8 a |

| Ascorbic acid (mg 100 g-1 d.m.) | 23.2 ± 1.5 a | 27.9 ± 2.5 a | 26.7 ± 3.6 a |

| Microbiology | |||

| AMB (log CFU mL-1) | 3.5 ± 0.0 | Absent | Absent |

| YM (log CFU mL-1) | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Parameter | Immediately after pasteurized | Storage time at 25 °C (Week) | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | |||

| Moisture content (%, w.b.) | BJ5 | 81.9 ± 0.1 aA | 81.6 ± 0.0 abA | 81.3 ± 0.2 bA | 81.7 ± 0.1 abA | 81.4 ± 0.2 bA |

| BJ10 | 81.7 ± 0.1 aA | 80.7 ± 0.2 cA | 80.9 ± 0.2 bcA | 81.4 ± 0.0 abA | 80.9 ± 0.0 bcA | |

| Color | ||||||

| L* | BJ5 | 33.5 ± 0.6 aA | 36.1 ± 2.6 aA | 34.3 ± 2.0 aA | 34.9 ± 1.7 aA | 34.6 ± 0.4 aA |

| BJ10 | 33.9 ± 1.0 bA | 37.3 ± 2.6 aA | 33.9 ± 0.7 bA | 33.6 ± 1.0 bA | 33.4 ± 0.6 bB | |

| a* | BJ5 | 8.7 ± 0.6 aA | 8.5 ± 0.5 aA | 7.3 ± 0.8 bA | 6.5 ± 0.5 bB | 6.8 ± 0.5 bA |

| BJ10 | 8.7 ± 0.7 abA | 9.0 ± 0.7 aA | 7.6 ± 0.5 bcA | 7.1 ± 0.4 cA | 7.1 ± 0.6 cA | |

| b* | BJ5 | 9.4 ± 0.8 aA | 10.5 ± 2.3 aA | 8.1 ± 0.5 aA | 9.7 ± 2.2 aA | 10.1 ± 1.6 aA |

| BJ10 | 9.9 ± 0.7 aA | 12.1 ± 2.6 aA | 9.3 ± 1.2 aA | 9.8 ± 1.7 aA | 9.8 ± 0.4 aA | |

| ΔE | BJ5 | - | 2.9 ± 2.5 aA | 2.7 ± 1.4 aA | 3.6 ± 2.1 aA | 3.2 ± 0.7 aA |

| BJ10 | - | 4.4 ± 2.6 aA | 1.8 ± 0.9 aA | 2.5 ± 0.7 aA | 2.0 ± 1.0 aA | |

| Soluble solid (° Brix) | BJ5 | 17.7 ± 0.2 bcA | 17.5 ± 0.0 cB | 18.0 ± 0.1 abB | 18.2 ± 0.3 aA | 18.3 ± 0.2 aB |

| BJ10 | 18.0 ± 0.0 dA | 19.1 ± 0.1 aA | 18.9 ± 0.1 bA | 18.5 ± 0.2 cA | 19.0 ± 0.1 abA | |

| Reductor sugar (g 100 g-1 d.m.) | BJ5 | 48.9 ± 2.9 aA | 46.2 ± 0.4 aA | 48.0 ± 5.2 aA | 49.1 ± 0.9 aA | 47.2 ± 0.7 aB |

| BJ10 | 49.4 ± 3.4 aA | 49.3 ± 3.4 aA | 42.4 ± 0.2 bA | 48.6 ± 1.7 aA | 49.4 ± 0.3 aA | |

| pH | BJ5 | 4.18 ± 0.02 bA | 4.07 ± 0.01 cB | 4.19 ± 0.01 bA | 4.17 ± 0.01 bB | 4.27 ± 0.01 aA |

| BJ10 | 4.14 ± 0.07 aA | 4.17 ± 0.01 aA | 4.17 ± 0.01 aA | 4.24 ± 0.01 aA | 4.27 ± 0.01 aA | |

| Titratable acidity (%) | BJ5 | 0.259 ± 0.031 aA | 0.254 ± 0.001 aA | 0.247 ± 0.001 aA | 0.242 ± 0.002 aA | 0.252 ± 0.001 aA |

| BJ10 | 0.260 ± 0.030 aA | 0.280 ± 0.001 aB | 0.246 ± 0.002 aA | 0.250 ± 0.000 aA | 0.251 ± 0.001 aA | |

| TPC (mg GAE 100 g-1 d.m.) |

BJ5 | 172.8 ± 4.4 aB | 170.0 ± 2.2 aB | 147.8 ± 0.3 bB | 149.0 ± 7.8 bB | 134.0 ± 3.7 cA |

| BJ10 | 186.8 ± 1.8 abA | 195.7 ± 5.1 aA | 160.1 ± 0.0 cA | 175.9 ± 7.5 bA | 136.2 ± 7.8 dA | |

| Ascorbic acid (mg100 g-1 d.m.) | BJ5 | 27.9 ± 2.5 aA | 23.5 ± 1.3 abA | 21.1 ± 0.9 bA | 22.9 ± 0.9 abA | 22.0 ± 1.5 abA |

| BJ10 | 26.7 ± 3.6 aA | 22.2 ± 1.2 aA | 23.1 ± 1.5 aA | 23.2 ± 0.6 aA | 21.4 ± 0.3 aA | |

| Microbiology | ||||||

| AMB (log CFU mL-1) | BJ5 | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| BJ10 | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | |

| YM (log CFU mL-1) | BJ5 | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| BJ10 | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).