Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

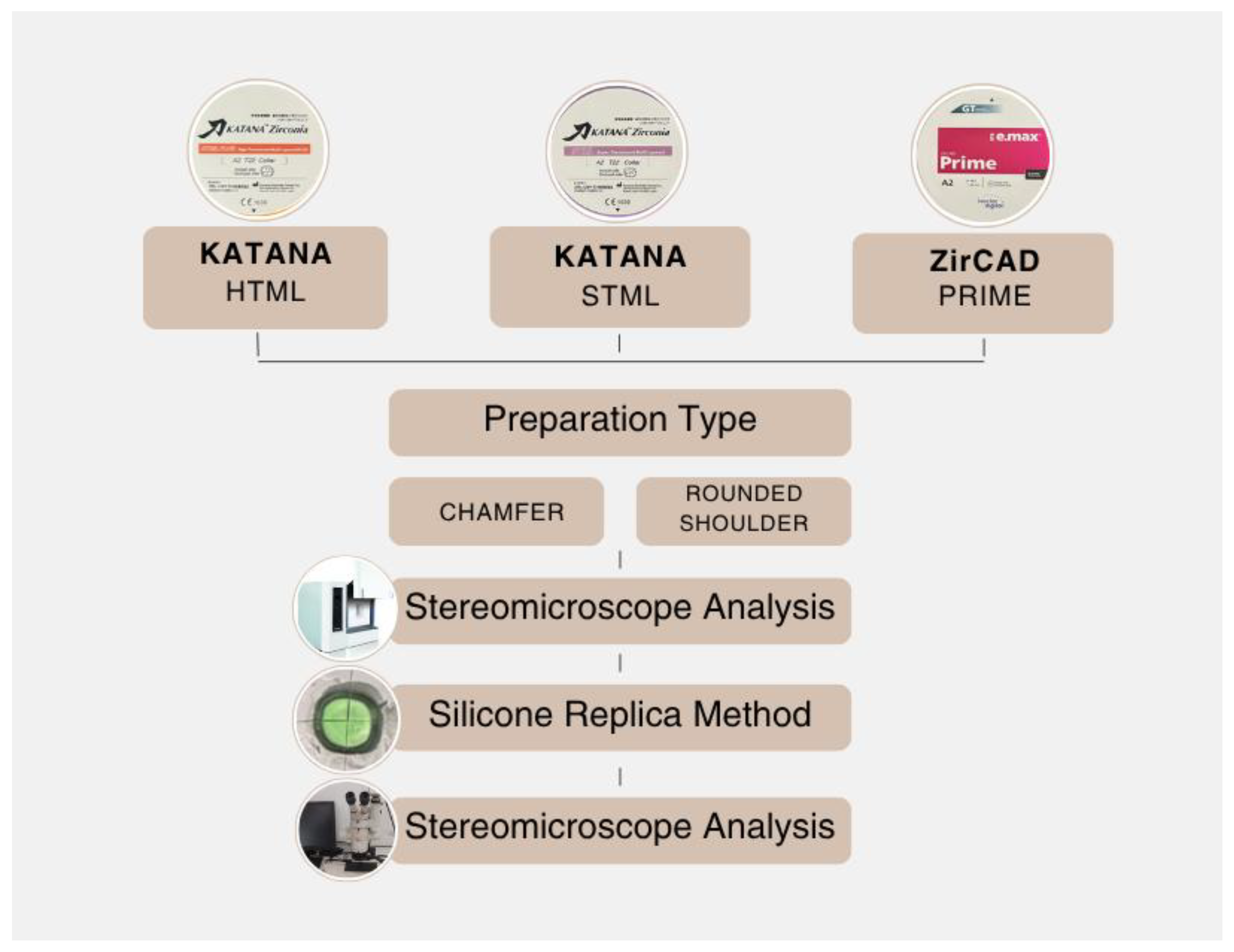

Aim: This in vitro study aimed to evaluate the marginal and internal fit of three monolithic CAD/CAM zirconia ceramics with different Y-TZP contents, prepared with chamfer and rounded shoulder finish lines. Methods. Sixty zirconia crowns were fabricated and equally divided into three material groups, each further subdivided into chamfer and rounded shoulder designs. Marginal and internal gaps were assessed using the silicone replica technique under a stereomicroscope by a single operator. Statistical analysis was performed with three-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05). Results: The occlusal region exhibited the largest gap values, while the axial region showed the smallest across all groups. Mean marginal and internal gaps were 33.79 µm for chamfer and 43.37 µm for rounded shoulder finish lines. Zirconia with higher Y-TZP content demonstrated significantly greater gap values than those with lower percentages (p < 0.05). Significant interactions were found among finish line design, material type, and measurement region (P < 0.05), with rounded shoulder margins showing larger gaps (p = 0.001). Conclusions: Y-TZP content significantly affects marginal and internal adaptation, with higher percentages associated with increased gap values. Both finish line types produced clinically acceptable fits, although chamfer margins provided superior adaptation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Size Calculation

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Evaluation of Marginal and İnternal Fit

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HTML | KATANA High Translucent Multilayer Zirconia |

| STML | KATANA Super Translucent Multilayer Zirconia |

| ZirCAD | IPS e.max ZirCAD Prime |

| R | Rounded Shoulder |

| C | Chamfer |

| µm | Micrometer |

| ANOVA | A three-way analysis of variance |

| Y-TZP | Yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystal |

| 2D | Two Dimensions |

References

- P.F. Cesar, R.B. de Paula Miranda, K.F. Santos, S.S. Scherrer, Y. Zhang, Recent advances in dental zirconia: 15 years of material and processing evolution, Dent. Mater. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, B.R. Lawn, Evaluating dental zirconia, Dent. Mater. 35(1) (2019) 15–23. [CrossRef]

- S. Kongkiatkamon, D. Rokaya, S. Kengtanyakich, C. Peampring, Current classification of zirconia in dentistry: An updated review, PeerJ 11 (2023) e15669. [CrossRef]

- M. Hasanzade, M. Moharrami, M. Alikhasi, How adjustment could affect internal and marginal adaptation of CAD/CAM crowns made with different materials, J. Adv. Prosthodont. 12(6) (2020) 344. [CrossRef]

- M.R. Baig, A.A. Akbar, M. Embaireeg, Effect of finish line design on the fit accuracy of CAD/CAM monolithic polymer-infiltrated ceramic-network fixed dental prostheses: an in vitro study, Polymers 13(24) (2021) 4311. [CrossRef]

- S. Suzuki, Y. Katsuta, K. Ueda, F. Watanabe, Marginal and internal fit of three-unit zirconia fixed dental prostheses: effects of prosthesis design, cement space, and zirconia type, J. Prosthodont. Res. 64(4) (2020) 460–467. [CrossRef]

- C.-C. Peng, K.-H. Chung, H.-T. Yau, Assessment of the internal fit and marginal integrity of interim crowns made by different manufacturing methods, J. Prosthet. Dent. 123(3) (2020) 514–522. [CrossRef]

- M. Rizonaki, W. Jacquet, P. Bottenberg, L. Depla, M. Boone, P.J. De Coster, Evaluation of marginal and internal fit of lithium disilicate CAD-CAM crowns with different finish lines by using a micro-CT technique, J. Prosthet. Dent. 127(6) (2022) 890–898. [CrossRef]

- J. Lyu, X. Cao, X. Yang, J. Tan, X. Liu, Effect of finish line designs on the dimensional accuracy of monolithic zirconia crowns fabricated with a material jetting technique, J. Prosthet. Dent. (2025). [CrossRef]

- [10] E. Mancuso, T. Gasperini, T. Maravic, C. Mazzitelli, U. Josic, A. Forte, et al., The influence of finishing line and luting material selection on the seating accuracy of CAD/CAM indirect composite restorations, J. Dent. 148 (2024) 105231. [CrossRef]

- [11] P. Fasih, S. Tavakolizadeh, M.S. Monfared, A. Sofi-Mahmudi, A. Yari, Marginal fit of monolithic versus layered zirconia crowns assessed with 2 marginal gap methods, J. Prosthet. Dent. 130(2) (2023) 250.e1–250.e7. [CrossRef]

- [12] M. Molin, S. Karlsson, The fit of gold inlays and three ceramic inlay systems: A clinical and in vitro study, Acta Odontol. Scand. 51(4) (1993) 201–206. [CrossRef]

- [13] J. Abduo, G. Ho, A. Centorame, S. Chohan, C. Park, R. Abdouni, et al., Marginal accuracy of monolithic and veneered zirconia crowns fabricated by conventional and digital workflows, J. Prosthodont. 32(8) (2023) 706–713. [CrossRef]

- [14] H. Zhu, Y. Zhou, J. Jiang, Y. Wang, F. He, Accuracy and margin quality of advanced 3D-printed monolithic zirconia crowns, J. Prosthet. Dent. (2023). [CrossRef]

- [15] L.F. Tabata, T.A. de Lima Silva, A.C. de Paula Silveira, A.P.D. Ribeiro, Marginal and internal fit of CAD-CAM composite resin and ceramic crowns before and after internal adjustment, J. Prosthet. Dent. 123(3) (2020) 500–505. [CrossRef]

- [16] A.C. de Paula Silveira, S.B. Chaves, L.A. Hilgert, A.P.D. Ribeiro, Marginal and internal fit of CAD-CAM-fabricated composite resin and ceramic crowns scanned by 2 intraoral cameras, J. Prosthet. Dent. 117(3) (2017) 386–392. [CrossRef]

- [17] J.W. McLean, Evolution of dental ceramics in the twentieth century, J. Prosthet. Dent. 85(1) (2001) 61–66. [CrossRef]

- [18] A. Baldi, A. Comba, D. Rozzi, G.K.R. Pereira, L.F. Valandro, R.M. Tempesta, et al., Does partial adhesive preparation design and finish line depth influence trueness and precision of intraoral scanners?, J. Prosthet. Dent. 129(4) (2023) 637.e1–637.e9. [CrossRef]

- [19] S. Sirous, A. Navadeh, S. Ebrahimgol, F. Atri, Effect of preparation design on marginal adaptation and fracture strength of ceramic occlusal veneers: A systematic review, Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 8(6) (2022) 1391–1403. [CrossRef]

- [20] K. Haggag, M. Abbas, H. Ramadan, Effect of thermo-mechanical aging on the marginal fit of two types of monolithic zirconia crowns with two finish line designs, Al-Azhar Dent. J. Girls 5(1) (2018) 121–128.

- [21] H. Yu, Y.-h. Chen, H. Cheng, T. Sawase, Finish-line designs for ceramic crowns: A systematic review and meta-analysis, J. Prosthet. Dent. 122(1) (2019) 22–30.e5. [CrossRef]

- [22] P. Yadav, V. Sharma, J. Paliwal, K.K. Meena, R. Madaan, B. Gurjar, An in vitro comparison of zirconia and hybrid ceramic crowns with heavy chamfer and shoulder finish lines, Cureus 15(1) (2023). [CrossRef]

- [23] D. Angerame, M. De Biasi, M. Agostinetto, A. Franzò, G. Marchesi, Influence of preparation designs on marginal adaptation and failure load of full-coverage occlusal veneers after thermomechanical aging simulation, J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 31(3) (2019) 280–289. [CrossRef]

- [24] R. Euán, O. Figueras-Álvarez, J. Cabratosa-Termes, R. Oliver-Parra, Marginal adaptation of zirconium dioxide copings: Influence of the CAD/CAM system and the finish line design, J. Prosthet. Dent. 112(2) (2014) 155–162. [CrossRef]

- [25] M. Bruhnke, Y. Awwad, W.-D. Müller, F. Beuer, F. Schmidt, Mechanical properties of new generations of monolithic, multi-layered zirconia, Materials 16(1) (2022) 276. [CrossRef]

- [26] S.E. Elsaka, Influence of surface treatment on the bond strength of resin cements to monolithic zirconia, J. Adhes. Dent. 18(5) (2016). [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, B.R. Lawn, Novel zirconia materials in dentistry, J. Dent. Res. 97(2) (2018) 140–147. [CrossRef]

- M. Michailova, A. Elsayed, G. Fabel, D. Edelhoff, I.-M. Zylla, B. Stawarczyk, Comparison between novel strength-gradient and color-gradient multilayered zirconia using conventional and high-speed sintering, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 111 (2020) 103977. [CrossRef]

- C.-M. Kang, W.-C. Hsu, M.-S. Chen, H.-Y. Wu, Y. Mine, T.-Y. Peng, Fracture characteristics and translucency of multilayer monolithic zirconia crowns of various thicknesses, J. Dent. 145 (2024) 105023. [CrossRef]

- N. Güntekin, B. Kızılırmak, A.R. Tunçdemir, Comparison of mechanical and optical properties of multilayer zirconia after high-speed and repeated sintering, Materials 18(7) (2025) 1493. [CrossRef]

- R. Giordano II, Ceramics overview, Br. Dent. J. 232(9) (2022) 658–663. [CrossRef]

- J.-H. Kim, S. Oh, S.-H. Uhm, Effect of the crystallization process on the marginal and internal gaps of lithium disilicate CAD/CAM crowns, Biomed. Res. Int. 2016(1) (2016) 8635483. [CrossRef]

- G. Yildirim, I.H. Uzun, A. Keles, Evaluation of marginal and internal adaptation of hybrid and nanoceramic systems with microcomputed tomography: An in vitro study, J. Prosthet. Dent. 118(2) (2017) 200–207. [CrossRef]

- G. Goujat, H. Abouelleil, P. Colon, C. Jeannin, N. Pradelle, D. Seux, et al., Mechanical properties and internal fit of 4 CAD-CAM block materials, J. Prosthet. Dent. 119(3) (2018) 384–389. [CrossRef]

- K. Son, S. Lee, S.H. Kang, J. Park, K.-B. Lee, M. Jeon, et al., A comparison study of marginal and internal fit assessment methods for fixed dental prostheses, J. Clin. Med. 8(6) (2019) 785. [CrossRef]

- P. Boitelle, L. Tapie, B. Mawussi, O. Fromentin, Evaluation of the marginal fit of CAD-CAM zirconia copings: Comparison of 2D and 3D measurement methods, J. Prosthet. Dent. 119(1) (2018) 75–81. [CrossRef]

- K. Ueda, F. Watanabe, Y. Katsuta, M. Seto, D. Ueno, K. Hiroyasu, et al., Marginal and internal fit of three-unit fixed dental prostheses fabricated from translucent multicolored zirconia: Framework versus complete contour design, J. Prosthet. Dent. 125 (2021) 340.e1–340.e6. [CrossRef]

- R.S. Cunali, R.C. Saab, G.M. Correr, L.F. Cunha, B.P. Ornaghi, A.V. Ritter, et al., Marginal and internal adaptation of zirconia crowns: a comparative study of assessment methods, Braz. Dent. J. 28 (2017) 467–473. [CrossRef]

- T.M. Doan, T.N. Nguyen, V.-K. Pham, N. Chotprasert, C.T.B. Vu, Comparative analysis of the fit quality of monolithic zirconia veneers produced through traditional and digital workflows using silicone replica technique: an in vitro study, BMC Oral Health 24 (2024) 1566. [CrossRef]

- A. Arezoobakhsh, S.S. Shayegh, A.J. Ghomi, S.M.R. Hakimaneh, Comparison of marginal and internal fit of 3-unit zirconia frameworks fabricated with CAD-CAM technology using direct and indirect digital scans, J. Prosthet. Dent. 123 (2020) 105–112. [CrossRef]

- Z.N. Al-Dwairi, M. Al-Sardi, B.J. Goodacre, C.J. Goodacre, K.Q. Al Hamad, M. Özcan, et al., Evaluation of marginal and internal fit of ceramic laminate veneers fabricated with five intraoral scanners and indirect digitization, Materials 16 (2023) 2181. [CrossRef]

- L. Guachetá, C.D. Stevens, J.A. Tamayo Cardona, R. Murgueitio, Comparison of marginal and internal fit of pressed lithium disilicate veneers fabricated via a manual waxing technique versus a 3D printed technique, J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 34 (2022) 715–720. [CrossRef]

- N. Sakornwimon, C. Leevailoj, Clinical marginal fit of zirconia crowns and patients’ preferences for impression techniques using intraoral digital scanner versus polyvinyl siloxane material, J. Prosthet. Dent. 118 (2017) 386–391. [CrossRef]

- Z.N. Al-Dwairi, R.M. Alkhatatbeh, N.Z. Baba, C.J. Goodacre, A comparison of the marginal and internal fit of porcelain laminate veneers fabricated by pressing and CAD-CAM milling and cemented with 2 different resin cements, J. Prosthet. Dent. 121 (2019) 470–476. [CrossRef]

| Material Type | Measured Region | Mean±SD1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTML | Occlusal Mean | 51.117± | |

| Axio-occlusal Mean | 40.085±13.215 | ||

| Axial Mean | 23.317± | ||

| Marginal Mean | 34.426±10.245 | ||

| Total | 37.237±15.928 | ||

| STML | Occlusal Mean | 42.913±6.140 | |

| Axio-occlusal Mean | 30.795±5.516 | ||

| Axial Mean | 19.750±2.950 | ||

| Marginal Mean | 35.901±8.060 | ||

| Total | 32.340±10.290 | ||

| ZirCAD | Occlusal Mean | 36.654±6.266 | |

| Axio-occlusal Mean | 28.287±2.433 | ||

| Axial Mean | 21.311±3.184 | ||

| Marginal Mean | 40.944±6.300 | ||

| Total | 31.799±8.988 | ||

| Overall | Occlusal Mean | 43.562±13.131 | |

| Axio-occlusal Mean | 33.056±9.598 | ||

| Axial Mean | 21.460±3.383 | ||

| Marginal Mean | 37.091±8.551 | ||

| Total | 33.792±12.262 |

| Material Type | Measured Region | Mean±SD1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTML | Occlusal Mean | 66.663±14.895 | |

| Axio-occlusal Mean | 55.164±12.050 | ||

| Axial Mean | 29.179±13.233 | ||

| Marginal Mean | 56.598±10.364 | ||

| Total | 51.901±18.616 | ||

| STML | Occlusal Mean | 53.664±20.243 | |

| Axio-occlusal Mean | 37.166±12.458 | ||

| Axial Mean | 20.283±4.331 | ||

| Marginal Mean | 54.962±15.504 | ||

| Total | 41.519±19.870 | ||

| ZirCAD | Occlusal Mean | 43.004±10.589 | |

| Axio-occlusal Mean | 35.036±6.548 | ||

| Axial Mean | 25.508±2.950 | ||

| Marginal Mean | 43.227±5.370 | ||

| Total | 36.694±9.918 | ||

| Overall | Occlusal Mean | 54.444±18.101 | |

| Axio-occlusal Mean | 42.456±13.815 | ||

| Axial Mean | 24.990±8.755 | ||

| Marginal Mean | 51.596±12.392 | ||

| Total | 43.371±17.771 |

| Material Type | Measured Region | Mean±SD1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTML | Occlusal Mean | 58.890±18.440 | |

| Axio-occlusal Mean | 47.625±14.538 | ||

| Axial Mean | 26.249±9.857 | ||

| Marginal Mean | 45.512±15.164 | ||

| Total | 44.569±18.729 | ||

| STML | Occlusal Mean | 48.289±15.569 | |

| Axio-occlusal Mean | 33.980±9.931 | ||

| Axial Mean | 20.017±3.617 | ||

| Marginal Mean | 45.432±15.500 | ||

| Total | 36.929±16.387 | ||

| ZirCAD | Occlusal Mean | 39.829±9.073 | |

| Axio-occlusal Mean | 31.662±5.925 | ||

| Axial Mean | 23.409±3.683 | ||

| Marginal Mean | 42.085±5.816 | ||

| Total | 34.246±9.722 | ||

| Overall | Occlusal Mean | 49.003±16.610 | |

| Axio-occlusal Mean | 37.756±12.711 | ||

| Axial Mean | 23.225±6.817 | ||

| Marginal Mean | 44.343±12.842 | ||

| Total | 38.582±15.973 |

| Variable | df | F | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 23 | 15.510 | <0.001 |

| Model intercept | 1 | 3.355.358 | <0.001 |

| Finish Line Type | 1 | 51.712 | <0.001 |

| Material Type | 2 | 21.554 | <0.001 |

| Measured Region | 3 | 71.062 | <0.001 |

| Finish Line Type * Material Type | 2 | 4.505 | 0.012 |

| Finish Line Type * Measured Region | 3 | 2.939 | 0.034 |

| Material Type * Measured Region | 6 | 4.034 | 0.001 |

| Finish Line Type * Material Type * Region | 6 | 1.117 | 0.354 |

| Group | Group2 | Mean | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material Type | HTML | 43.939±18.714a | <0.001 |

| STML | 37.224±16.489b | ||

| ZirCAD | 34.246±9.722bc | ||

| Overall | 38.582±15.973 | ||

| Measured Region | Occlusal | 49.003±16.610a | <0.001 |

| Axio-occlusal | 37.756±12.711b | ||

| Axial | 23.225±6.817c | ||

| Marginal | 44.343±12.842a | ||

| Overall | 38.582±15.973 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).