Introduction

The increasing adoption of subcrestally placed implants (SPIs) has underscored the need for a refined understanding of peri-implant soft tissue behavior. While the biologic width concept has been extensively studied in natural teeth, its direct application to implants remains inadequate, particularly in the three-dimensional context of SPI. Traditional models fail to account for the dynamic interplay between the implant restoration, soft tissue, and underlying crestal bone, leading to potential challenges in ensuring long-term peri-implant health and esthetics.

Subcrestally placed implants (SPI) have emerged as a versatile technique designed to address specific clinical challenges. While their adoption has increased significantly, key concerns remain—particularly due to the lack of a well-defined model that explains the biologic width around implants in a three-dimensional context. This gap in understanding is especially evident in efforts to differentiate between pathological pockets, typically associated with periodontal disease, and the extended peri-implant soft tissue interface found around implant restorations. Despite these challenges, SPI continues to gain traction as a technique aimed at achieving biologically stable and esthetically favorable outcomes. (1,2,3,4)

This article introduces an advanced clinical framework that defines the peri-implant soft tissue interface using the concepts of the Transitional Zone (TZ) and Subcrestal Zone (SZ). By differentiating these regions and establishing parameters for optimal soft tissue adaptation, the proposed model offers a biologically driven approach to implant restoration planning. This framework integrates anatomical, biomechanical, and prosthodontic considerations to enhance peri-implant stability, mitigate the risk of mucositis, and optimize esthetic outcomes. Furthermore, a mathematical approach to emergence profile design is presented to guide clinicians in determining appropriate implant placement depth and restoration contours.

Through a combination of clinical observations and theoretical modeling, this manuscript provides practical guidelines for achieving predictable, biologically stable, and esthetically integrated implant restorations. By shifting from traditional empirical approaches to a structured three-dimensional analysis, this framework advances the precision and predictability of peri-implant soft tissue management.

Though some concepts introduced here may be regarded as hypothetical, they are supported by numerous clinical cases and practical applications, as demonstrated throughout this article.

Optimizing Emergence Profile and Placement Depth in Molar Implant Restorations

A fundamental principle in implant therapy is the recreation of natural tooth anatomy and function. Beyond mere replacement, successful implant restoration demands careful consideration of emergence profile design, particularly in the posterior region where esthetics and function must coexist. Although the anterior region typically receives more attention regarding esthetic outcomes, molar restorations require equal attention to ensure harmonious soft tissue adaptation and biomechanical stability.

The emergence profile of the implant must facilitate a seamless transition between the restoration and surrounding tissues, mimicking the contours of a natural tooth. This involves meticulous planning of the submucosal portion, including the implant abutment and the crown’s cervical region, to ensure a biologically stable and esthetically natural result.

Coronal Flaring: A Crucial Consideration in IPS Implants

In Internal Platform Switching (IPS) implants, coronal flaring plays a critical role in achieving both biological stability and esthetic integration. Coronal flaring refers to the gradual widening of the implant restoration’s emergence profile as it transitions from the implant fixture-abutment connection (FAC) to the cervical contour of the crown. This design ensures a natural emergence profile that blends seamlessly with the surrounding soft tissue.

However, there is a clinical debate regarding the ideal placement of coronal flaring relative to the peri-implant mucosa:

(a) Supra-mucosal coronal flaring: When flaring occurs above the mucosal level, the emergence profile remains entirely supramucosal. This results in a less natural transition between the implant restoration and peri-implant soft tissue, which may compromise esthetics, especially in visible regions.

(b) Sub-mucosal coronal flaring: When flaring occurs beneath the mucosa, it allows for a progressive transition between the abutment and the soft tissue, leading to a more natural-looking emergence profile and improved esthetic outcomes.

Clinical Concerns About Sub-Mucosal Coronal Flaring

Some clinicians prefer supra-mucosal coronal flaring over sub-mucosal flaring due to concerns about the potential formation of a deep peri-implant pocket, which could increase the risk of bacterial colonization and peri-implant disease. Their argument is based on the assumption that a longer peri-implant soft tissue interface may be more susceptible to pathogenic invasion.

However, this assumption is flawed. Sub-mucosal coronal flaring is not only esthetically superior but also biologically advantageous. The elongated soft tissue seal, rather than being a source of vulnerability, reinforces peri-implant defense mechanisms by increasing the area of connective tissue attachment and vascular supply. This enhanced biologic width around IPS implants provides greater resistance to microbial penetration and peri-implant disease, ensuring long-term stability.

Rationale for Supporting Sub-Mucosal Coronal Flaring

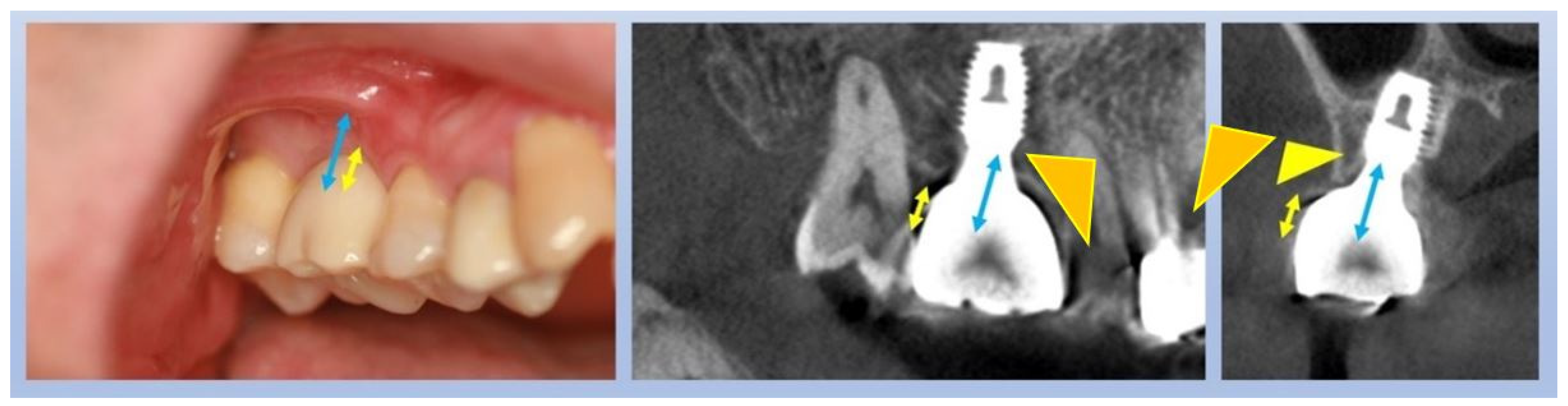

Figure 1 highlights the importance of a carefully designed emergence profile in achieving a natural and biologically stable peri-implant soft tissue interface. In SPI cases, ensuring seamless soft tissue adaptation to the implant restoration is critical. By placing coronal flaring submucosally, the transition between the implant and the soft tissue more closely mimics that of natural dentition, enhancing both esthetic and functional outcomes. However, this approach inevitably results in an extended and broader transitional zone within the peri-implant soft tissue.

The primary objective of peri-implant soft tissue management is to establish a biologically stable and esthetically harmonious integration between the implant and the surrounding gingiva. Increasing the contact area between the peri-implant mucosa and the implant restoration enhances soft tissue adaptation, leading to a more natural-looking appearance. However, this technique and its clinical applications require validation to confirm that an enlarged contact area not only increases biologic width but also reinforces the peri-implant soft tissue barrier against microbial infiltration.

To dispel the misconception that sub-mucosal coronal flaring predisposes implants to peri-implantitis, it is essential to understand the broader contact zone of peri-implant soft tissue established in SPI. The key question is whether this configuration results in a hazardous pocket prone to microbial infiltration or a biologically protective seal that reinforces peri-implant health.

As proposed in this article—A Novel Framework for Optimizing Peri-Implant Soft Tissue in SPI—by integrating the Transitional Zone (TZ) and Subcrestal Zone (SZ) as components of Self-Sustained Soft Tissue (SSST), this study introduces a new framework for interpreting the broad contact area generated in SPI. Grounded in both clinical observation and theoretical analysis, this model provides a more comprehensive understanding of peri-implant soft tissue behavior in subcrestally placed implants.

Biologically Stable and Esthetic Molar Implant Restoration (BEMIR)

For an implant restoration to achieve a natural appearance, the peri-implant soft tissue (pink) and the cervical portion of the implant restoration (white) must be proportional in size and aligned harmoniously with the gingival levels of adjacent teeth. As long as the surrounding gingiva remains healthy, ensuring this precise correspondence from the very first visible point of the restoration supports a seamless and natural-looking integration within the oral environment (

Figure 1).

To achieve this outcome, the submucosal portion of the implant restoration—including the abutment and cervical region of the crown—must be designed in accordance with morphological and biological principles. This ensures a progressive emergence profile, facilitates soft tissue adaptation, and enhances both esthetics and biological stability. The emergence profile must be meticulously planned to maintain a smooth transition between the implant restoration and peri-implant soft tissue, preventing abrupt contour changes that may compromise integration.

Determining the Vertical Dimension for Optimal Emergence Profile

A key step in BEMIR planning is defining the required vertical distance (V) from the peri-implant soft tissue to the implant restoration’s starting point, i.e., the fixture-abutment connection (FAC). This is influenced by:

Horizontal emergence profile dimensions (difference between the FAC diameter and the cervical diameter of the crown).

Emergence angle (EA) or flaring angle (FA), dictating the contour transition.

A refined understanding of coronal flaring mechanics—particularly the distinction between supra-mucosal and sub-mucosal flaring—is essential in optimizing soft tissue adaptation and achieving a functional, esthetic emergence profile.

Table 1 presents calculated vertical distances based on various emergence angles (EA) and horizontal differences, providing a guideline for bone-level implants with IPS designs.

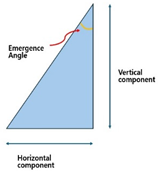

It has been long since the emergence angle (EA) is more known in academic literature with its definition (angle formed between the long axis of implant and the lateral surface or the implant restoration). But clinically, using flaring angle (FA) is more convenient. FA is defined as the angle between the lateral surface of the implant restoration and the horizontal plane which is perpendicular to the long axis of implant) Simply, EA = 90 -FA. FA is more nuanced when addressing the coronal flaring phenomenon which is indispensable for IPS implants.

Flaring Angle (FA) vs. Emergence Angle (EA): A Practical Perspective

The Emergence Angle (EA) has long been the standard parameter in academic literature for describing the transition between an implant and its restoration. It is defined as the angle formed between the implant’s long axis and the lateral surface of the implant restoration. This definition has been widely accepted in theoretical discussions and research studies. However, in clinical practice, the Flaring Angle (FA) offers a more intuitive and practical alternative for evaluating the coronal flaring phenomenon, which is crucial for Internal Platform Switching (IPS) implants.

Defining the Flaring Angle (FA)

FA is measured as the angle between the lateral surface of the implant restoration and the horizontal plane, which is perpendicular to the implant’s long axis. This makes FA more relevant for clinical applications, particularly when adjusting submucosal contours and ensuring optimal emergence profile design. Since FA is measured from the horizontal reference, while EA is measured from the implant’s long axis, they are related by the equation:

EA = 90 − FA

This relationship highlights how FA provides a direct representation of the horizontal flaring component, whereas EA focuses on the vertical emergence transition.

While EA remains essential in theoretical discussions, FA provides a more clinically relevant and practical alternative—particularly for IPS implants, where the coronal flaring effect plays a critical role in soft tissue adaptation and implant esthetics.

Mathematical Approach to Determining Vertical Distance for Emergence Profile Optimization

In designing a biologically stable and esthetic molar implant restoration (BEMIR), a key factor is determining the necessary vertical distance (v) from the first visible point of the implant restoration above the peri-implant soft tissue to the fixture-abutment connection (FAC). This measurement is typically taken from the buccal first point (BFP)—the most coronal visible part of the implant restoration above the mucosa—and is based on the emergence angle (EA) or flaring angle (FA), where:

FA=90−EA

This distance (v) is dependent on two factors:

The horizontal distance difference (d) between the cervical diameter of the restoration and the FAC diameter.

The emergence angle (EA), which describes the inclination of the lateral contour of the implant restoration relative to the implant axis.

To achieve a natural-looking, esthetic emergence profile, the diameter of the implant restoration at the BFP should correspond to the height of the contour of the designed restoration.

Accounting for Peripheral Crestal Offset (PCO) in Total Vertical Distance Calculation

Before determining the actual depth of implant placement, it is necessary to account for the natural curvature of the edentulous ridge, as it is rarely flat.

CP (Center Point): The midpoint of the ridge, where the implant depth is measured.

BFP (Buccal First Point): The peripheral area (~5 mm off-center), where the cervical contour of the crown meets the surrounding soft tissue.

Due to the natural ridge curvature, the BFP is often positioned 1–2 mm more apically than the CP, particularly on the buccal side. This vertical discrepancy, known as Peripheral Crestal Offset (PCO), must be incorporated into the final implant depth calculation to ensure a properly designed emergence profile and seamless esthetic integration.

Example Calculation (Including PCO Adjustment)

Consider an SPI case with:

Emergence Angle (EA) = 40° / or Flaring Angle (FA) = 50°

Fixture Diameter = 5 mm

Fixture-Abutment Connection (FAC) Diameter = 3 mm

Cervical Crown Diameter = 10 mm

First, we calculate d:

D = (10−3) / 2=3.5 mm

Using the emergence profile formula:

V = 3.5 / tan (40) ≈ 4.17 mm

Now, adjusting for PCO (1.5 mm):

V total = v + PCO = 4.17 + 1.5 = 5.67 mm

Clinical Implications of V_total

When applying this V_total clinically, clinicians must:

Ensure that the reference point of measurement remains at the center of the edentulous crest (CP).

Recognize that the total vertical distance (5.67 mm) includes mucosal thickness, which varies between 2–3 mm.

Adjust implant positioning to accommodate the natural curvature of the ridge, ensuring optimal peri-implant soft tissue support.

By incorporating the PCO effect, this refined approach ensures a precise implant depth determination, ultimately facilitating the achievement of a Biologically Stable and Esthetic Molar Implant Restoration (BEMIR).

Cross-Sectional Variations in Emergence Profiles and Their Clinical Implications from MDCS (Mesiodistal Crest Slope) Discrepancy

Figure 2 highlights the discrepancy between the buccolingual (BL) and mesiodistal (MD) cross-sections in emergence profiles, which differ in vertical height and emergence slope:

BL Cross-Section: The Peripheral Crestal Offset (PCO) causes an apical shift of the peripheral crest, increasing the total vertical height at the Center Point (CP). However, the vertical height from the Fixture-Abutment Connection (FAC) to the Buccal First Point (BFP) is lower than that from the FAC to CP.

MD Cross-Section: The Mesiodistal Crest Slope (MDCS) discrepancy results in a saddle-shaped ridge, particularly between adjacent teeth. This leads to a greater vertical height from the FAC to the Mesial First Point (MFP) or Distal First Point (DFP) compared to the FAC to CP.

Key Considerations: The Influence of MDCS Discrepancy on Flaring Angles (FA) and Emergence Angles (EA)

-

MD Cross-Section Bias in Vertical Height Determination

- o

Clinicians traditionally rely on MD cross-sectional views from plain X-rays, which can lead to overestimated vertical height due to the naturally higher MD plane compared to the BL plane.

-

Impact on Flaring and Emergence Angles

- o

Since the BL cross-section requires a shorter vertical height, the flaring angle (FA bl) is lower than the FA md in the MD plane.

- o

Using a single emergence angle (EA) or flaring angle (FA) for both planes can cause discrepancies in soft tissue adaptation and prosthetic contouring.

-

Clinical and Prosthetic Implications

- o

Submucosal Contour Estimation: Differentiating between FA bl and FA md is essential to avoid errors in soft tissue adaptation.

- o

Prosthetic Design Adjustments: The buccal aspect should serve as the primary reference for esthetics, ensuring a harmonious emergence profile.

How Deep is Deep Enough? Rethinking the Optimal Subcrestal Implant Depth Through Calculated Analysis

Therefore, considering that FA_bl is lower than FA_md, clinicians should reconsider the favorable EA range, which typically falls within 30°–40° (corresponding to FA 60°–50°). However, most clinical reports on EA originate from EA_md, as they are primarily derived from plain X-ray data. Given that EA_bl tends to be larger than EA_md in the same tooth case, as illustrated in

Figure 2, it is prudent to reevaluate the clinically favorable range of EA_bl, which is likely within 60°–50° (FA 30°–40°).

Assuming PCO = 1.5 mm, the following estimations can be made:

FA = 30°, v = 2.02 mm, V total = 3.52 mm

FA = 40°, v = 2.94 mm, V total = 4.44 mm

FA = 45°, v = 3.5 mm, V total = 5.0 mm

Clinical Implications:

In summary, when FA_bl falls within the range of 30°–45°, the corresponding V total ranges from 3.52 to 5.0 mm. If the mucosal thickness is assumed to be 2.0 mm, the actual subcrestal implant placement depth will range between 1.52 and 3.0 mm, averaging approximately 2.0 mm subcrestal placement.

(Note: The reference point for implant placement depth is typically measured at the buccal aspect in clinical settings.)

While many clinicians may expect the proposed subcrestal placement depth to be significantly deeper than conventional practice, this analysis provides a logically derived range, demonstrating that deeper placement is not only feasible but biologically advantageous for long-term peri-implant stability in BEMIR.

While scientific data suggest that a favorable emergence angle exists—primarily derived from mesiodistal analyses, which have inherent limitations—the true clinical relevance of emergence angle lies in its role in protecting peri-implant soft tissue. In this context, the thickness of Supracrestal Tissue Height (STH) becomes a critical factor for long-term implant stability. However, incorporating these parameters into clinical practice remains challenging, as it is impractical to measure precise values for every case. This is where the Three-Dimensional Soft Tissue Analysis (3DSTA) model provides a clinically beneficial approach—allowing for a biologically favorable implant restoration design that enhances peri-implant soft tissue health while optimizing esthetics.

Clinical Scenarios for SPI

The SPI technique is particularly advantageous in three primary scenarios:

-

Esthetic Considerations in Molar Restorations

SPI is frequently employed to meet esthetic demands, particularly in molar restorations where establishing an appropriate emergence profile is essential. This technique enables seamless integration of prosthetic components with the surrounding soft tissue, enhancing both functionality and esthetics by ensuring adequate vertical soft tissue height for the transit area (Transitional Zone, TZ).

-

Managing Narrow Alveolar Ridges

In cases of narrow ridges, SPI offers an effective solution by allowing for deeper implant placement while promoting a favorable peri-implant phenotype. This ensures sufficient bone and soft tissue support, both of which are essential for long-term implant stability and health.

-

Implant Placement Adjacent to Natural Teeth

SPI is particularly useful in anterior or premolar regions adjacent to healthy natural teeth, especially in the upper arch. These regions often present challenges due to variations in edentulous ridge levels between buccolingual and mesiodistal interproximal spans. By placing implants subcrestally, clinicians can better accommodate these anatomic differences, preserving the functionality and esthetics of neighboring teeth.

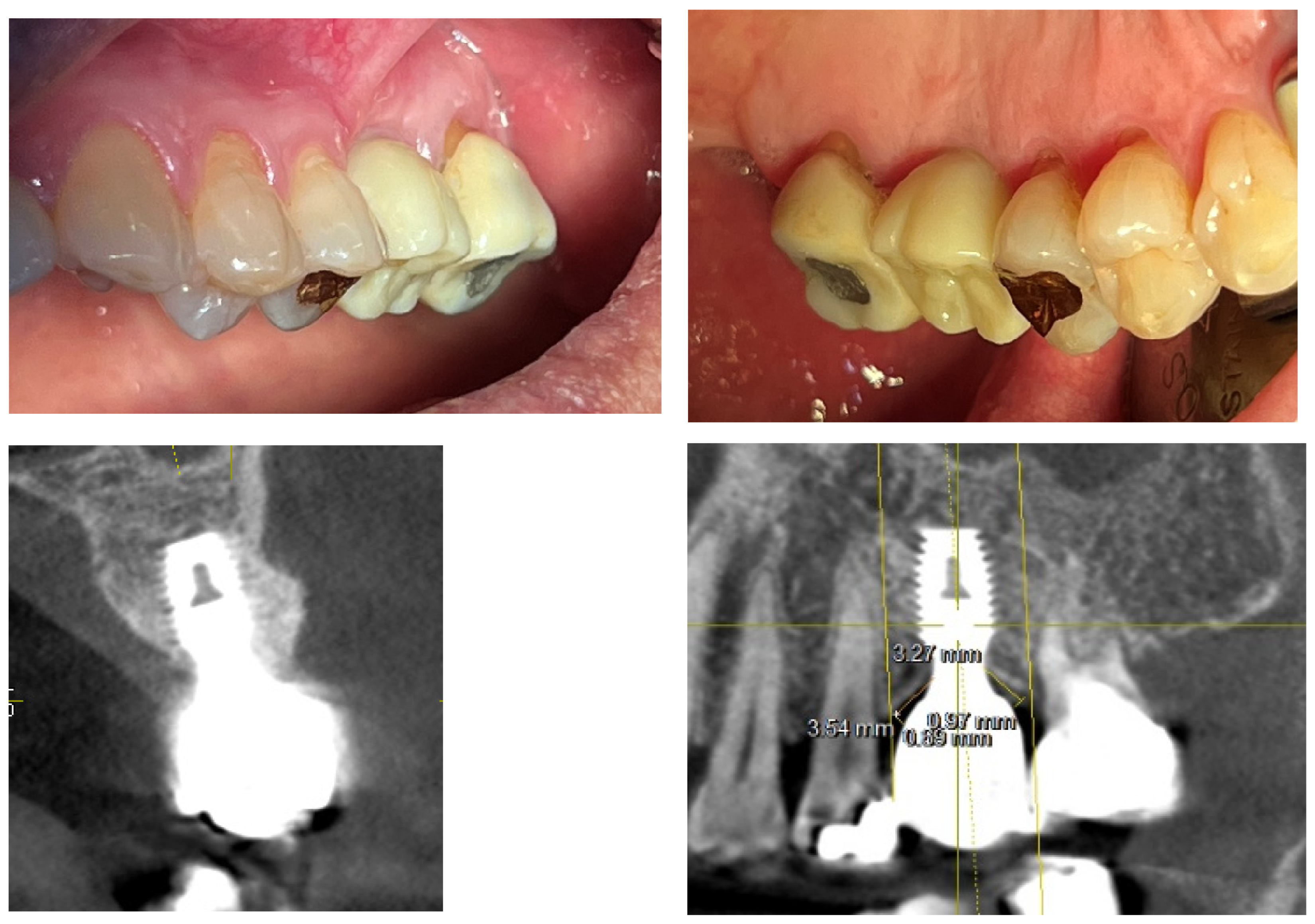

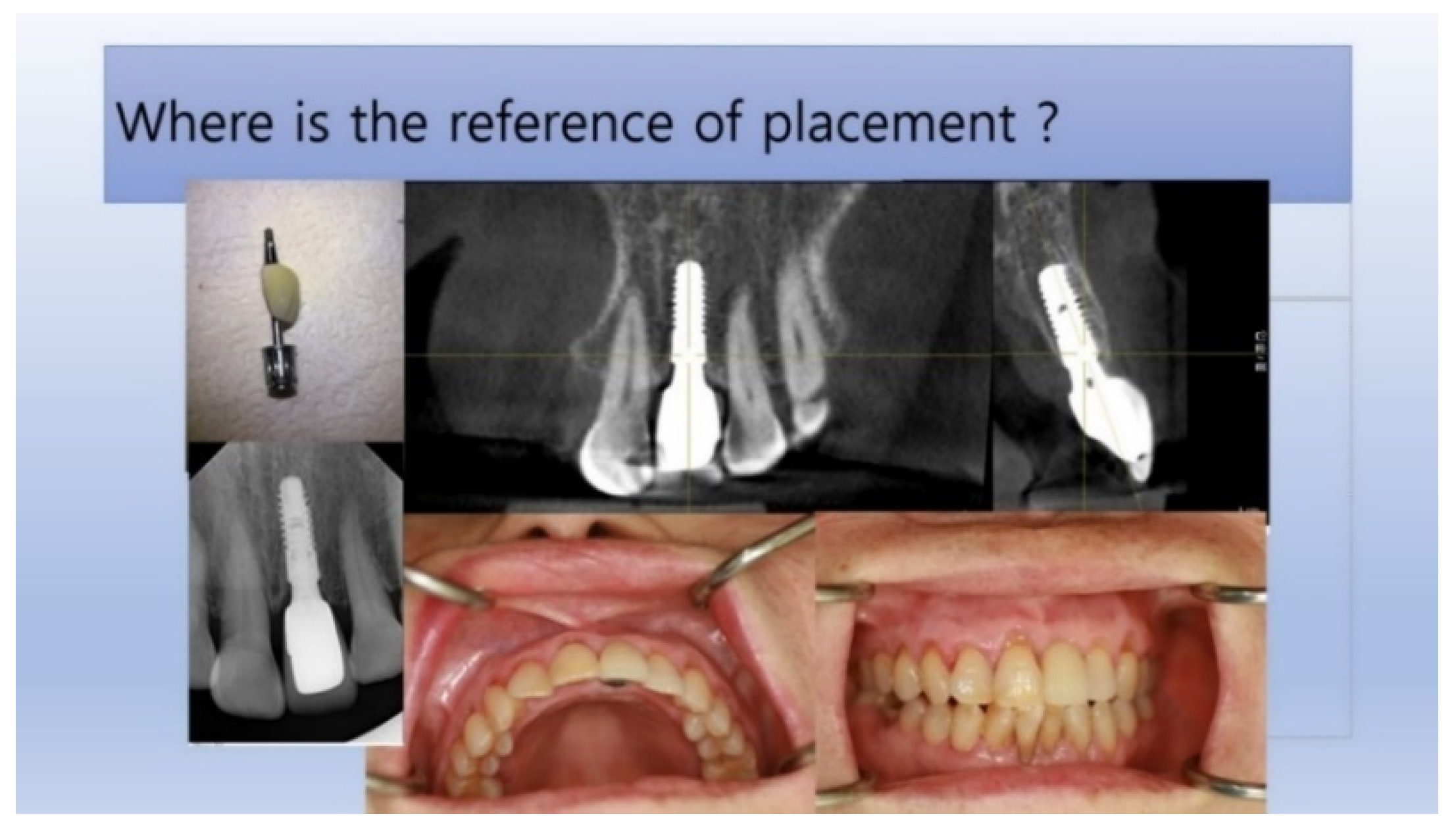

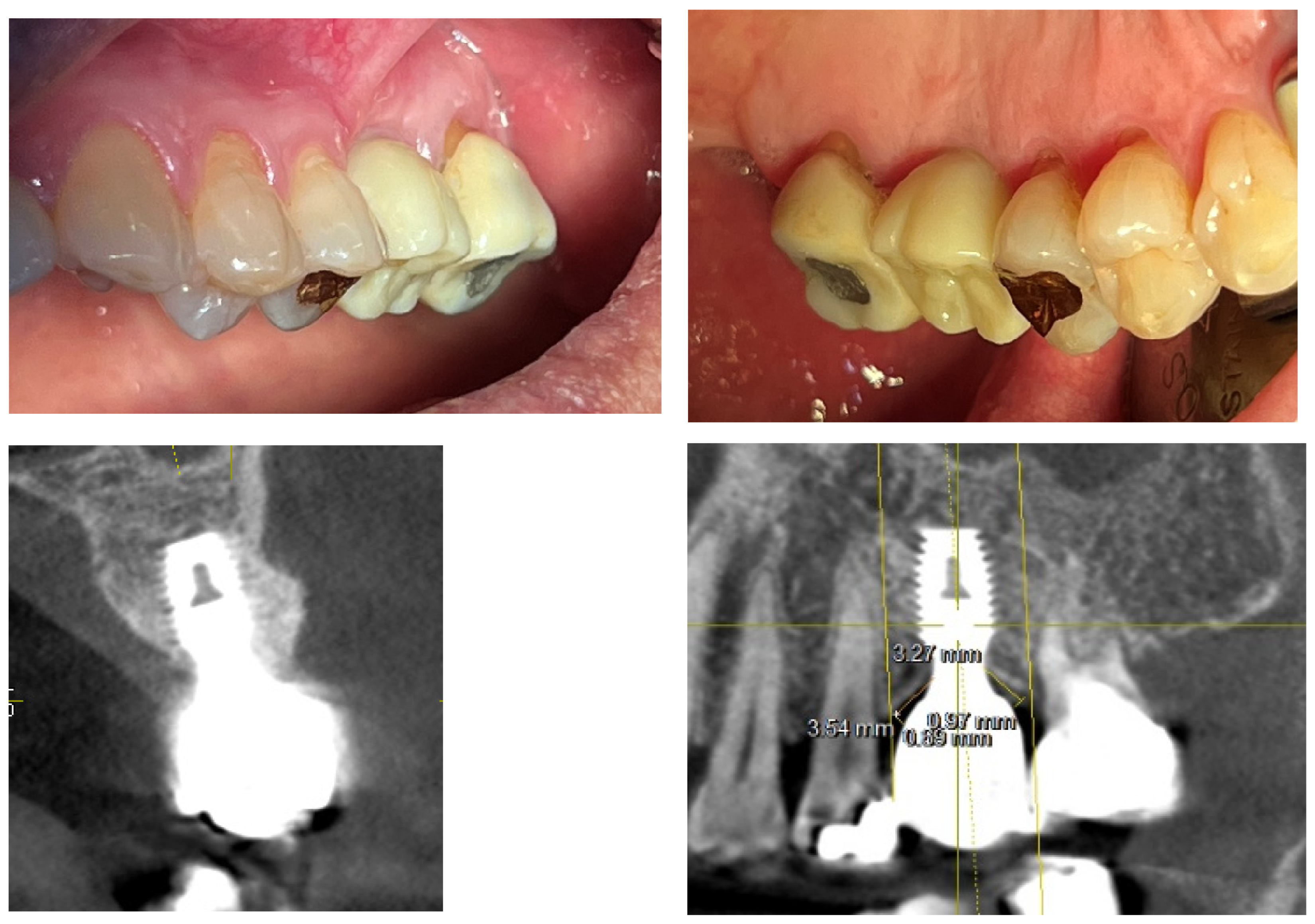

Figure 4 showcases a successful case of SPI, demonstrating stable and esthetic outcomes. The clinical photos highlight natural soft tissue integration, while the CBCT images provide peri-implant soft tissue analysis, including measurements of Transitional Zone Length (TZL) and Soft Tissue Thickness (STT). These parameters help to evaluate the relationship between structural support and biological stability achieved with SPI.

Figure 4.

Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes of an SPI-Restored Upper Left First Molar. Upper Two Images (Clinical Photos): Show the restored upper left first molar with well-integrated soft tissue, demonstrating a natural emergence profile and coronal flaring of the implant restoration. These features contribute to both biological stability and esthetic success. Lower Left Image (CBCT Cross-Section, Buccolingual View): Displays the implant placement. While the PCO effect suggests that the buccal margin is positioned more apically than the mesiodistal margin—resulting in a shorter overall distance from the fixture-abutment connection (FAC) to the soft tissue margin in the buccal aspect—this does not necessarily imply that the crestal zenith at the buccal side must always be positioned apically. Unlike the palatal side, where the crest may be observed at an epicrestal level, implant placement at the buccal side can still be subcrestal, provided it meets the required vertical depth for peri-implant stability or is intended to enhance the bone phenotype. Lower Right Image (CBCT with Measurements): Highlights the Transitional Zone Length (TZL) and Soft Tissue Thickness (STT), showing the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the peri-implant soft tissue. Additionally, it reflects the influence of Mesiodistal Crestal Slope (MDCS), emphasizing how ridge morphology affects implant positioning, peri-implant soft tissue stability, and overall emergence profile.

Figure 4.

Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes of an SPI-Restored Upper Left First Molar. Upper Two Images (Clinical Photos): Show the restored upper left first molar with well-integrated soft tissue, demonstrating a natural emergence profile and coronal flaring of the implant restoration. These features contribute to both biological stability and esthetic success. Lower Left Image (CBCT Cross-Section, Buccolingual View): Displays the implant placement. While the PCO effect suggests that the buccal margin is positioned more apically than the mesiodistal margin—resulting in a shorter overall distance from the fixture-abutment connection (FAC) to the soft tissue margin in the buccal aspect—this does not necessarily imply that the crestal zenith at the buccal side must always be positioned apically. Unlike the palatal side, where the crest may be observed at an epicrestal level, implant placement at the buccal side can still be subcrestal, provided it meets the required vertical depth for peri-implant stability or is intended to enhance the bone phenotype. Lower Right Image (CBCT with Measurements): Highlights the Transitional Zone Length (TZL) and Soft Tissue Thickness (STT), showing the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the peri-implant soft tissue. Additionally, it reflects the influence of Mesiodistal Crestal Slope (MDCS), emphasizing how ridge morphology affects implant positioning, peri-implant soft tissue stability, and overall emergence profile.

Biologic Width in Natural Teeth vs. Peri-Implant Tissues

The Concept of Biologic Width in Natural Teeth

The biologic width, first described in 1961 (8), refers to the gingival soft tissue extending from the gingival sulcus to the alveolar crest. This dimension averages approximately 2.0 mm in width and is composed of two key layers:

Junctional Epithelium (~0.97 mm wide): Functions as a protective epithelial barrier against microbial invasion.

Connective Tissue (~1.07 mm wide): Provides mechanical support and contributes to immunologic defense mechanisms (9).

Together, these structures act as a biological seal, preventing bacterial infiltration and ensuring periodontal stability (10).

Structural Differences Between Peri-Implant Tissues and Natural Teeth

Although the biologic width concept has been applied to implants, several key structural differences highlight the need for a dedicated model for peri-implant tissues (11):

- 1.

-

Absence of a Periodontal Ligament

Natural teeth rely on the periodontal ligament (PDL) for biological and mechanical mediation. In contrast, implants achieve stability through direct osseointegration, lacking any ligamentous attachment. This structural difference increases the vulnerability of peri-implant soft tissues to mechanical stress and bacterial challenges.

- 2.

-

Lack of Dentogingival Fiber Attachment

In natural teeth, dentogingival fibers anchor the gingiva to the cementum, contributing to soft tissue stability and resistance against external forces. Implants, however, lack this intrinsic fibrous attachment, making their soft tissue seal inherently different. Peri-implant tissues rely solely on their own structural and immunological integrity to provide protection.

- 3.

-

Distinct Crown-Root Morphology and Coronal Flaring

- o

Natural teeth exhibit a gradual transition from the root to the crown, allowing for a smooth adaptation of the soft tissue.

- o

Implant restorations, on the other hand, display a distinct coronal flaring, where the prosthetic crown widens abruptly. This poses unique challenges for peri-implant soft tissue adaptation and stability.

Since implant restorations interface directly with peri-implant soft tissue, their morphology significantly influences soft tissue behavior. Unlike natural teeth, which have a gradual emergence profile, implants require careful emergence profile design to optimize biological stability. Consequently, multiple studies have examined the relationship between peri-implant soft tissue stability, crestal bone health, implant positioning, and restoration morphology (12,13,14,15).

Implications of Coronal Flaring and the Limitations of Existing Biologic Width Models

SPIs are almost exclusively performed using implants with Internal Platform Switching (IPS) design, which offers several biological advantages, particularly in maintaining crestal bone stability. A key characteristic of SPI restorations is coronal flaring, a feature that significantly influences both soft tissue adaptation and esthetic integration (16,17,18).

However, this coronal flaring phenomenon creates a distinct peri-implant soft tissue configuration, fundamentally different from the traditional biologic width model of natural teeth. Unlike natural teeth, where the dentogingival fibers provide intrinsic support, peri-implant soft tissues must adapt to abrupt diameter changes. This adaptation occurs primarily in the transit area—a critical horizontal and vertical zone that must be carefully designed to ensure peri-implant health and long-term stability.

Thus, the traditional biologic width model fails to adequately explain the peri-implant soft tissue interface in three dimensions. A new model is necessary—one that accounts for:

✔ Soft Tissue Adaptation to Coronal Flaring

✔ The Role of the Transitional Zone (TZ) and Subcrestal Zone (SZ)

✔ Horizontal and Vertical Components of the Peri-Implant Soft Tissue Seal

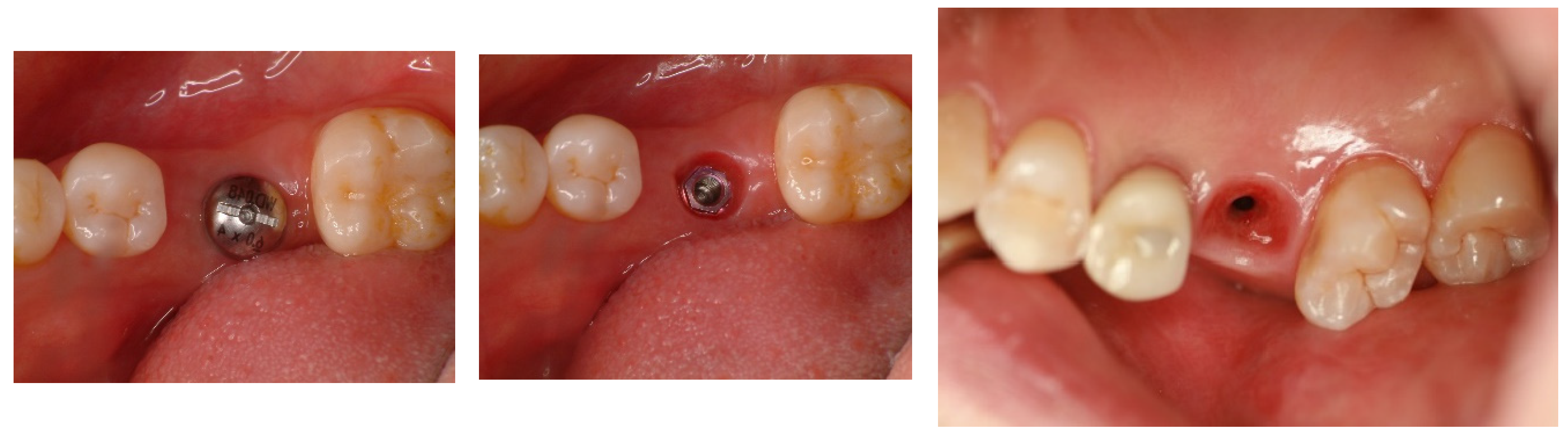

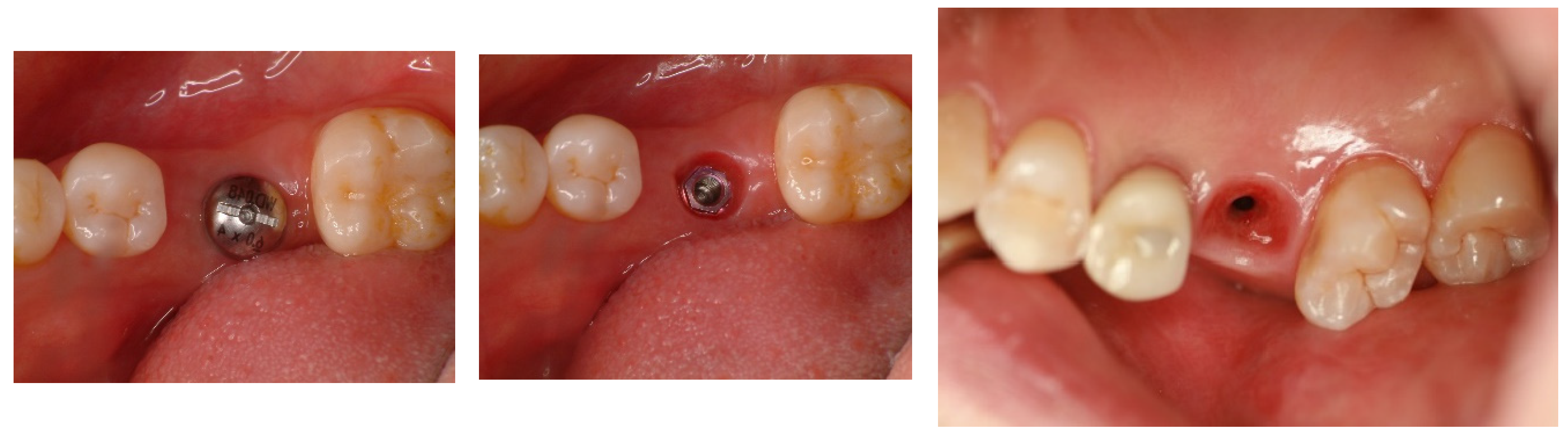

The images in Figure 5 illustrate the differences in peri-implant soft tissue adaptation based on implant connection type and coronal morphology.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Peri-Implant Soft Tissue Architecture With and Without Horizontal Extension. This figure illustrates three different peri-implant soft tissue configurations, highlighting the impact of implant design on soft tissue adaptation: Left Image (Healing Abutment): Displays a healing abutment in place, where the peri-implant soft tissue adapts primarily in a vertical manner, similar to the biologic width observed around natural teeth. Middle Image (External Hex Connection Implant): Shows an external hex connection implant embedded in the edentulous ridge without being covered by a healing cap or cover screw. In this configuration, the peri-implant soft tissue exhibits only a vertical component, directly interfacing with the implant structure in a manner akin to natural teeth. Right Image (Internal Platform Switching Implant, SPI): Demonstrates an SPI with an internal connection and platform switching, exposed in the same manner as the middle image. Unlike the external hex implant, the peri-implant soft tissue here exhibits both vertical and horizontal components, adapting to the coronal flaring of the restoration. This horizontal extension alters the peri-implant soft tissue structure, making it more complex than the simple vertical adaptation seen in external hex implants or healing abutments. This comparison underscores the fundamental difference between traditional biologic width models based on natural teeth and the peri-implant soft tissue configuration in SPIs, necessitating a revised conceptual framework for understanding peri-implant tissue adaptation.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Peri-Implant Soft Tissue Architecture With and Without Horizontal Extension. This figure illustrates three different peri-implant soft tissue configurations, highlighting the impact of implant design on soft tissue adaptation: Left Image (Healing Abutment): Displays a healing abutment in place, where the peri-implant soft tissue adapts primarily in a vertical manner, similar to the biologic width observed around natural teeth. Middle Image (External Hex Connection Implant): Shows an external hex connection implant embedded in the edentulous ridge without being covered by a healing cap or cover screw. In this configuration, the peri-implant soft tissue exhibits only a vertical component, directly interfacing with the implant structure in a manner akin to natural teeth. Right Image (Internal Platform Switching Implant, SPI): Demonstrates an SPI with an internal connection and platform switching, exposed in the same manner as the middle image. Unlike the external hex implant, the peri-implant soft tissue here exhibits both vertical and horizontal components, adapting to the coronal flaring of the restoration. This horizontal extension alters the peri-implant soft tissue structure, making it more complex than the simple vertical adaptation seen in external hex implants or healing abutments. This comparison underscores the fundamental difference between traditional biologic width models based on natural teeth and the peri-implant soft tissue configuration in SPIs, necessitating a revised conceptual framework for understanding peri-implant tissue adaptation.

The left-side images display cases using older external hex connection implants, where healing abutments are positioned without horizontal widening at the tissue-restoration interface. In these instances, the peri-implant soft tissue closely mimics the biologic width observed around natural teeth, adapting vertically without significant horizontal extension. Consequently, the tissue thickness in these cases primarily reflects the dimensions of the adjacent mucosal tissue.

In contrast, the right-side images depict subcrestally placed implants (SPI) with internal connection and platform-switching designs, which introduce a coronal flaring effect at the restoration interface. This horizontal extension at the tissue-implant junction modifies the peri-implant soft tissue structure, leading to the formation of both horizontal and vertical soft tissue components. This dimensional adaptation is a defining characteristic of peri-implant tissues influenced by coronal flaring, fundamentally distinguishing them from the soft tissue architecture seen around natural teeth and conventional external hex implants.

Clinical Implications of Coronal Flaring and Soft Tissue Adaptation in SPIs

The presence of both vertical and horizontal soft tissue components in SPIs suggests that the traditional biologic width model, originally developed for natural teeth, cannot be directly applied to implants—especially those featuring internal platform switching (IPS) and subcrestal placement. Unlike the vertically adapted soft tissue seen in natural teeth and external hex implants, the coronally flared emergence profile in SPIs reconfigures the peri-implant soft tissue adaptation, requiring a more comprehensive three-dimensional model.

- 2.

Enhanced Soft Tissue Stability Through Horizontal Extension:

The horizontal extension created by platform switching and coronal flaring plays a crucial role in reinforcing peri-implant soft tissue stability. This expanded tissue interface enhances connective tissue contact, reduces microleakage at the implant-abutment junction, and contributes to long-term peri-implant soft tissue maintenance, thereby reducing the risk of peri-implant inflammation.

- 3.

Prosthetic Design Considerations for Optimized Soft Tissue Adaptation:

The emergence profile in SPIs must be meticulously contoured to accommodate the horizontal and vertical soft tissue dimensions. Failing to recognize this structural complexity can result in poor soft tissue adaptation, leading to esthetic and biological complications. A precisely designed transition zone, incorporating both buccolingual (BL) and mesiodistal (MD) emergence profiles, is essential for achieving biological integration and esthetic continuity with adjacent natural teeth.

Implications for Future Peri-Implant Soft Tissue Modeling

These findings highlight the necessity for a novel framework to accurately define and analyze peri-implant soft tissue behavior in SPIs. Traditional biologic width concepts must be expanded to incorporate three-dimensional aspects, acknowledging the impact of coronal flaring, horizontal soft tissue extension, and emergence profile variations across different cross-sections. This paradigm shift in understanding soft tissue adaptation in SPIs will pave the way for refined clinical protocols and improved implant designs, ultimately enhancing long-term peri-implant health and esthetic outcomes.

The Need for a Multidimensional Analysis Framework

Traditional two-dimensional analyses of peri-implant tissues, long considered the standard, fail to capture the multidirectional complexity of soft tissue and bone adaptation around implants. The biologic width in natural teeth is typically represented as a single vertical dimension, yet implant morphology—especially with coronal flaring—requires a broader, multidirectional perspective.

While CBCT-based studies have investigated peri-implant soft tissue thickness, prior research has been largely confined to the anterior region, where esthetic concerns are more pronounced. However, posterior restorations also require precise peri-implant soft tissue management to ensure both functional stability and esthetic harmony. Given that CBCT serves as a valuable tool for assessing peri-implant structures, it is crucial to establish clinically relevant and theoretically meaningful parameters that enhance our understanding and improve implant outcomes across both anterior and posterior regions.

Advancements in Implant Technology and Soft Tissue Analysis

With the integration of digital workflows in contemporary dentistry—such as Computer-Aided Design (CAD), Computer-Aided Manufacturing (CAM), and digital scanning—prosthetic designs have become increasingly customized to achieve a seamless transition between implant restorations and peri-implant soft tissues. However, accurate restoration planning requires a deeper understanding of the biological and structural interactions between soft tissue and the underlying bone.

To address this need, this study introduces a novel investigative framework: 3-Dimensional Soft Tissue Analysis (3DSTA). Unlike conventional two-dimensional measurements, 3DSTA evaluates peri-implant soft tissue holistically, emphasizing the interplay between horizontal and vertical dimensions. By integrating three-dimensional peri-implant soft tissue analysis with CBCT-based assessment, this model lays the foundation for precise restoration design and biologically stable outcomes.

Implications for Future Implant Restoration Planning

When statistical data becomes available through extensive studies utilizing this model, the fabrication of Biologically Stable and Esthetic Molar Implant Restorations (BEMIR) will no longer rely solely on customary design approaches but will instead be guided by peri-implant soft tissue dictated by its underlying bone anatomy. This transition shifts the paradigm from empirical prosthetic adjustments to biologically driven restoration planning, ensuring long-term peri-implant health and esthetic success.

Given the structural differences between natural teeth and implants, particularly in subcrestally placed implants (SPIs) with coronal flaring, a three-dimensional analytical framework is essential for understanding peri-implant soft tissue adaptation. Conventional biologic width models, originally based on natural teeth, fail to capture the buccolingual variations and the impact of horizontal soft tissue extension in SPIs. Therefore, this study introduces a novel 3-Dimensional Soft Tissue Analysis (3DSTA) model to provide a comprehensive understanding of these interactions and guide biologically driven implant restoration planning.

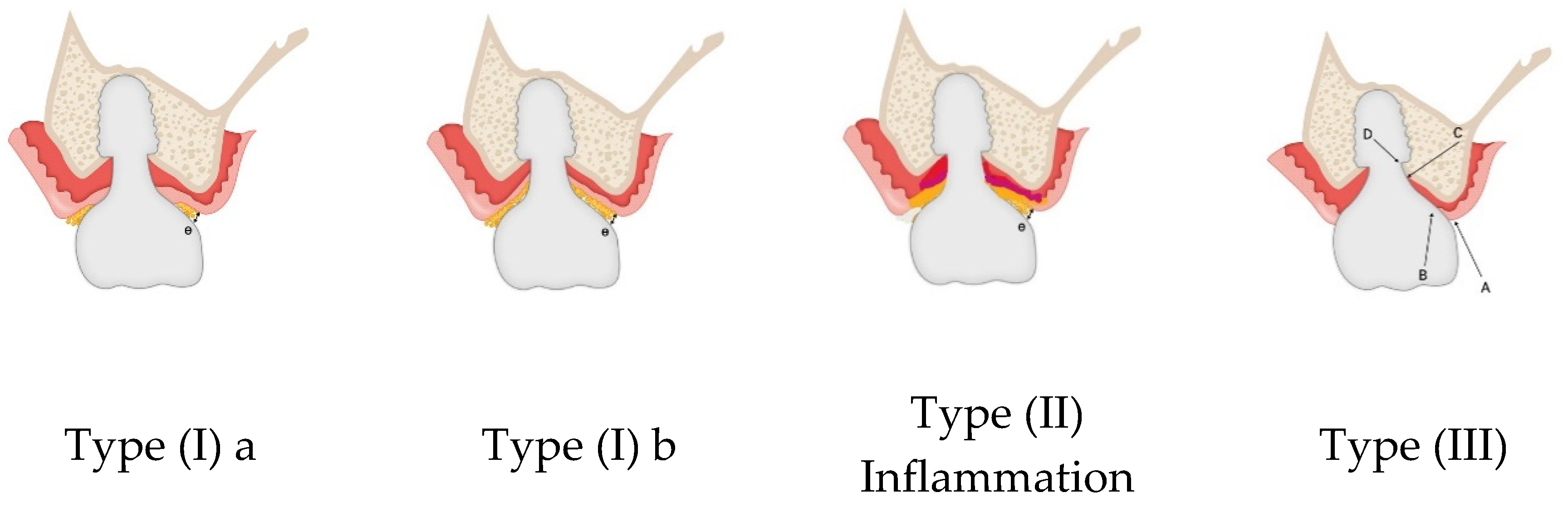

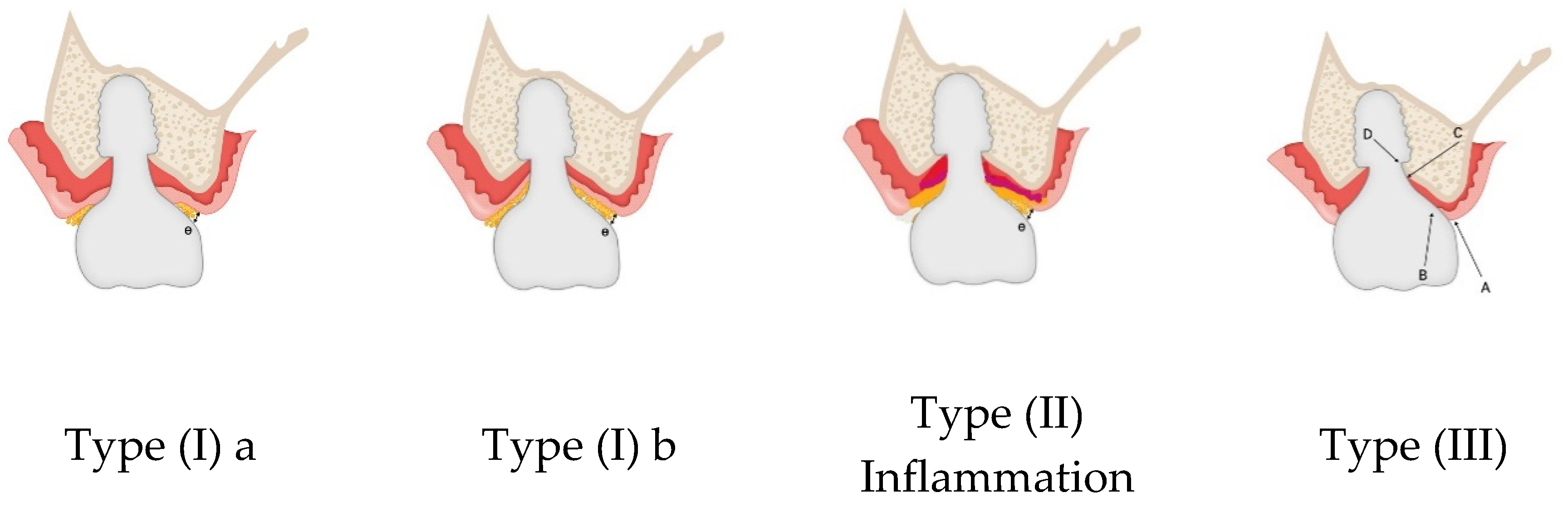

Figure 6.

Schematic models postulated to address concerns about the development of unhealthy pockets around SPI. What defines the transitional zone in SPI? Unlike the biologic width in natural teeth, the peri-implant soft tissue around SPI is shaped by a horizontal transit zone extending from the implant-abutment connection to the outer soft tissue margin.Two plausible models describe how epithelium and connective tissue might distribute within this zone: Type I: Epithelium and connective tissue exist in two distinct layers throughout the entire transit zone—epithelium faces the restoration, while connective tissue contacts the crestal bone. Type II: Inflammation stage: As bacteria invade the sulcus, peri-implant soft tissue breakdown and inflammation begin. Type III: Epithelium is present only at the entrance of the transit zone, while the remainder consists of a single-layer connective tissue barrier. Determining factors for either model likely depend on restoration design, crestal bone topography, and peri-implant soft tissue thickness and length.

Figure 6.

Schematic models postulated to address concerns about the development of unhealthy pockets around SPI. What defines the transitional zone in SPI? Unlike the biologic width in natural teeth, the peri-implant soft tissue around SPI is shaped by a horizontal transit zone extending from the implant-abutment connection to the outer soft tissue margin.Two plausible models describe how epithelium and connective tissue might distribute within this zone: Type I: Epithelium and connective tissue exist in two distinct layers throughout the entire transit zone—epithelium faces the restoration, while connective tissue contacts the crestal bone. Type II: Inflammation stage: As bacteria invade the sulcus, peri-implant soft tissue breakdown and inflammation begin. Type III: Epithelium is present only at the entrance of the transit zone, while the remainder consists of a single-layer connective tissue barrier. Determining factors for either model likely depend on restoration design, crestal bone topography, and peri-implant soft tissue thickness and length.

Logical Transition to 3DSTA: Understanding the Histological Composition of the Peri-Implant Soft Tissue

Before delving into the 3-Dimensional Soft Tissue Analysis (3DSTA) framework, it is essential to first address the histological composition of peri-implant soft tissue—particularly the connective tissue and junctional epithelium, which play a crucial role in the stability of SPI restorations. Proper interpretation of the Transitional Zone (TZ) is key to distinguishing between a healthy peri-implant interface and the formation of an unhealthy pocket.

While biologic width in natural teeth is well-established, the horizontal transit layer in SPIs remains less clearly defined, raising questions about its structural composition and biological function. Since direct histologic examination of peri-implant tissue is impractical in a clinical setting, logical postulation based on known tissue behavior is required.

Two Hypothetical Models for the Composition of the Transitional Zone (TZ)

To better conceptualize the structural organization of peri-implant soft tissue in SPIs, three plausible schematic models have been proposed:

-

Type I Model (Layered Epithelium and Connective Tissue Across the Entire Transit Zone)

- o

-

In this model, the transit zone (TZ) consists of two distinct layers extending horizontally:

- ▪

Epithelium (either junctional or sulcular) faces the restoration side.

- ▪

Connective tissue is positioned beneath the epithelium, adjacent to the underlying crestal bone.

- o

This structure resembles the biologic width of natural teeth but may develop voids due to an excessively long Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD), which could compromise soft tissue adaptation.

-

Type II: Inflammation Stage

- o

As bacteria invade the sulcus, peri-implant soft tissue breakdown and inflammation begin.

-

Type III Model (Epithelium Limited to the Entrance Area, Dominated by Connective Tissue)

- o

In contrast, this model proposes that the epithelial layer (junctional or sulcular) is only present at the entrance of the transit zone, forming a two-layer structure only in the initial entry area.

- o

The majority of the transit zone is occupied solely by connective tissue, forming a single-layer barrier between the restoration and the underlying crestal bone.

- o

This reduces epithelial downgrowth, potentially enhancing soft tissue attachment and resistance to microbial penetration.

The determinants of whether Type I or Type III is expressed in a given SPI case likely depend on multiple factors, including:

The topography of contributing elements (implant-abutment interface, restoration contour, and underlying bone).

The distribution and thickness of peri-implant soft tissue in both horizontal and vertical dimensions.

The emergence profile design, which influences the biological response of the surrounding soft tissue.

Why This Analysis is Critical for 3DSTA

Understanding the histologic variations within the peri-implant transit zone is crucial for establishing a clinically relevant framework for evaluating SPI restorations. By considering these hypothetical models, 3DSTA can provide a structured approach to analyzing the peri-implant soft tissue in three dimensions, bridging the gap between theoretical morphology and real-world clinical adaptation.

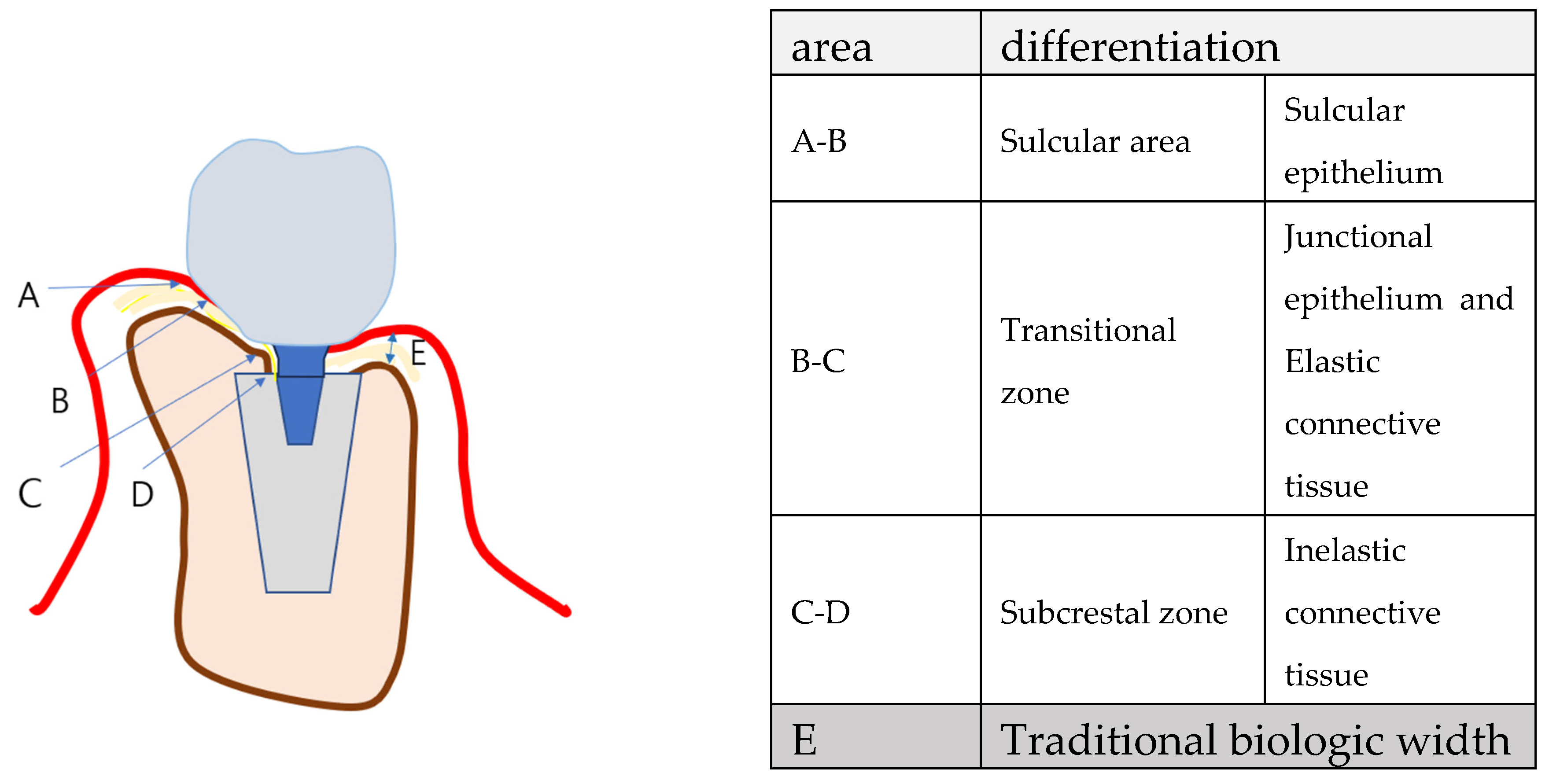

Figure 7 is a schematic representation of peri-Implant soft tissue zones. This schematic drawing illustrates the differentiation of peri-implant soft tissue into three distinct zones, each playing a crucial role in the biological stability and function of SPI:

Figure 7.

Schematic drawing to differentiate the peri-implant soft tissue into 3 zones 1) sulcular area 2) transitional zone 3) subcrestal zone.

Figure 7.

Schematic drawing to differentiate the peri-implant soft tissue into 3 zones 1) sulcular area 2) transitional zone 3) subcrestal zone.

Peri-Implant Soft Tissue Zones

Sulcular Area – The most coronal portion, adjacent to the restoration, lined with sulcular epithelium. This zone is functionally similar to the gingival sulcus around natural teeth, permitting limited probing without compromising the biological seal.

Transitional Zone (TZ) – The horizontal extension of peri-implant soft tissue that connects the sulcular area to the deeper subcrestal zone. This region is hypothesized to contain both junctional epithelium and connective tissue, forming a critical biologic barrier against external irritants. Structurally, the TZ is essential for stabilizing peri-implant soft tissue and preventing apical migration of the epithelium, thereby maintaining peri-implant health.

Subcrestal Zone (SZ) – The portion of peri-implant soft tissue located below the crestal bone level. This zone is predominantly composed of connective tissue and remains relatively thin due to its direct proximity to the subcrestal bone. The SZ is thought to contribute to peri-implant soft tissue stability by reinforcing the underlying bone-implant interface.

This conceptual division emphasizes the need to understand peri-implant soft tissue beyond the conventional biologic width model, particularly in SPIs, where both vertical and horizontal soft tissue components must be accounted for.

Histological Perspective on Junctional Epithelium and Connective Tissue: Addressing the Differences Between Implants and Natural Teeth for Clinical Advantage

Connective Tissue and Its Role in Peri-Implant Health

Connective tissue within the peri-implant soft tissue plays a critical role in maintaining biological stability. Its thickness and proximity to the underlying crestal bone, as measured through Crest to Restoration Gap (CRG)—which transitions into Soft Tissue Thickness (STT) when optimized—are key to its structural and functional integrity. Maintaining stable CRG/STT dimensions is essential for long-term peri-implant health, preventing bone loss, and supporting soft tissue adaptation.

Key Functional Roles of Peri-Implant Connective Tissue:

Supporting the Junctional Epithelium – Provides a stable foundation and vascular supply, ensuring biological sealing.

Immune Functionality – Acts as a conduit for immune cells and signaling molecules, facilitating immune responses.

Mechanical Sealing – Resists external forces through resilience and biochemical properties, including protein-carbohydrate macromolecules.

Tissue Repair – Serves as a reservoir of stem cells and fibroblasts, promoting healing and soft tissue regeneration.

Bone Protection – Functions similarly to the periosteum, safeguarding the underlying bone and promoting homeostasis.

Junctional Epithelium and Its Role in Peri-Implant Soft Tissue Stability

The junctional epithelium is the first line of defense against microbial colonization around implants. While its sealing capacity is reported to be less robust than that of natural teeth, hemidesmosomal attachments have been well-documented, forming a functional barrier by adhering both to the implant surface and the underlying connective tissue. (19,20,21,22,23,24)

Key Features of Peri-Implant Junctional Epithelium:

Limited Thickness – Typically 0.5–1 mm, this layer is restricted to the coronal portion of the peri-implant soft tissue, while connective tissue comprises the majority of the interface.

High Turnover Rate – The rapid renewal capacity of the junctional epithelium aids in maintaining its protective barrier.

Structural Characteristics – Consists of 15–30 cell layers with larger intercellular spaces and fewer desmosomes compared to oral epithelium. This feature enhances immune cell mobility, improving immunological function.

Hemidesmosomal Attachments – These structures provide adhesion to both the implant surface and the underlying connective tissue, forming the biologic seal that prevents microbial invasion. While weaker than the attachment seen in natural teeth, it remains essential for peri-implant integrity.

Immunological Function – Facilitates endocytosis and decomposition of exogenous factors, helping to regulate the local immune response.

Comparing Peri-Implant vs. Natural Tooth Junctional Epithelium:

Unlike natural teeth, where the periodontal ligament and hemidesmosomal attachments provide continuous integration with the oral mucosa, the peri-implant junctional epithelium is functionally distinct. Since implants lack the periodontal ligament, the peri-implant soft tissue relies more on connective tissue support to maintain long-term biological stability.

In essence, peri-implant soft tissue stability is more connective tissue-dependent than in natural teeth, making soft tissue engineering and implant-abutment interface design crucial for long-term success.

Why This Understanding Matters Clinically

Implant Design Considerations – Given the limited sealing capacity of the junctional epithelium, implant-abutment surface modifications may enhance soft tissue attachment.

Importance of Connective Tissue Stability – Soft tissue grafting techniques or optimized peri-implant soft tissue thickness (STT) may compensate for the absence of a periodontal ligament.

Reducing Risk of Peri-Implantitis – Enhancing connective tissue attachment minimizes epithelial apical migration, reducing peri-implant pocket formation.

Final Thoughts

By understanding these fundamental histological differences, clinicians can optimize peri-implant tissue behavior through prosthetic design, surgical techniques, and strategic soft tissue management to enhance peri-implant health and longevity.

Figure 8 illustrates a common clinical observation: while the plain X-ray suggests a subcrestal implant placement, the CBCT image reveals an epi-crestal position in the buccolingual aspect. This discrepancy highlights the limitations of two-dimensional imaging and reinforces the necessity of three-dimensional evaluation for precise implant positioning.

Figure 8.

Although the plain X-ray image suggests that the implant was placed subcrestally, the CBCT image reveals that the fixture was actually placed epi-crestally in the buccolingual aspect. This discrepancy highlights the limitations of two-dimensional imaging, emphasizing the need for three-dimensional evaluation to accurately assess implant positioning relative to the crestal bone in both buccolingual and mesiodistal dimensions.

Figure 8.

Although the plain X-ray image suggests that the implant was placed subcrestally, the CBCT image reveals that the fixture was actually placed epi-crestally in the buccolingual aspect. This discrepancy highlights the limitations of two-dimensional imaging, emphasizing the need for three-dimensional evaluation to accurately assess implant positioning relative to the crestal bone in both buccolingual and mesiodistal dimensions.

Although epi-crestal placement in the buccolingual direction is frequently observed, the subcrestal positioning in the mesiodistal aspect requires further academic interpretation. Despite various hypotheses proposed in the literature—most of which are speculative rather than based on actual human histology—a consistent and widely accepted model to explain the transitional zone in subcrestally placed implants has yet to be established.

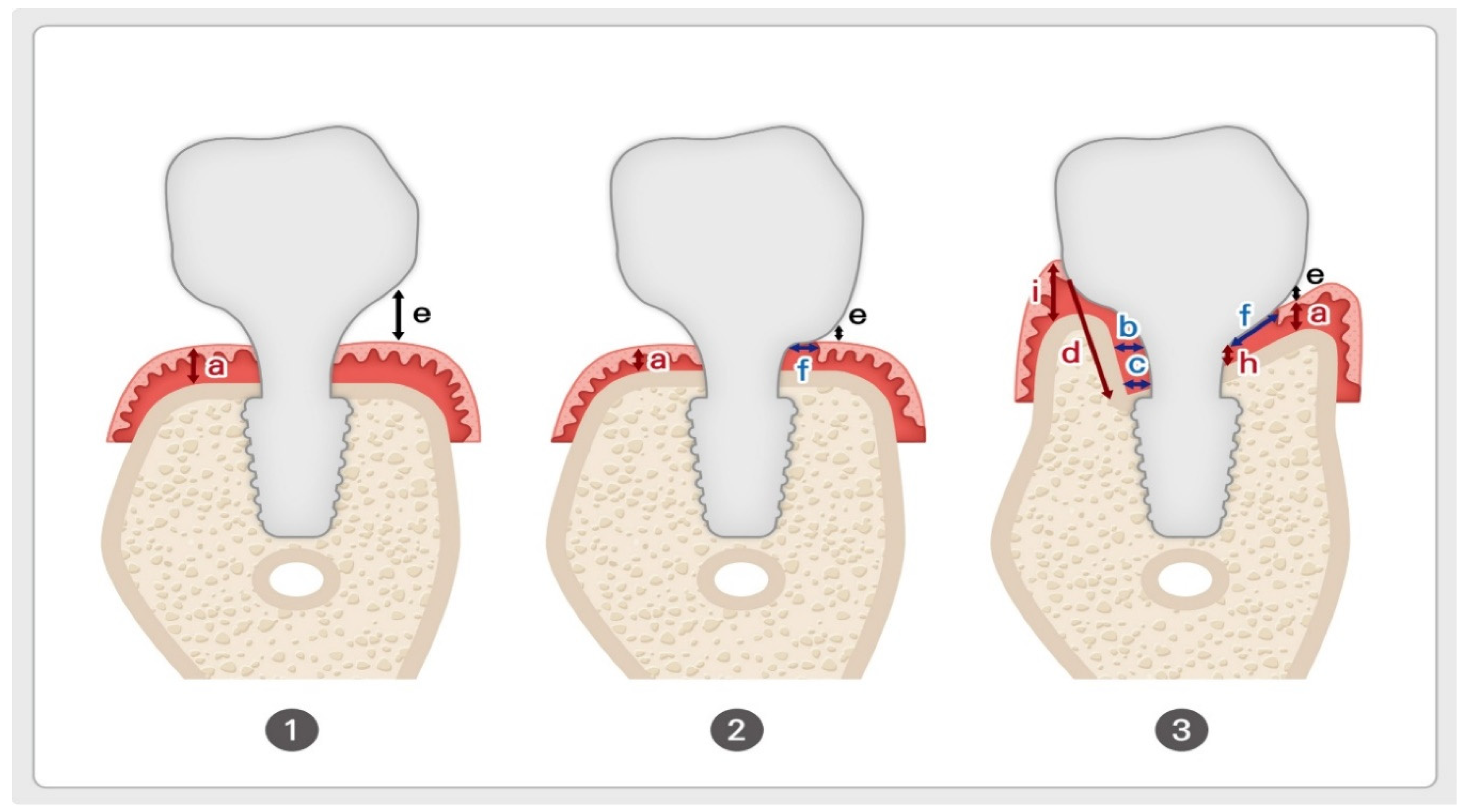

Variations in Peri-Implant Soft Tissue Adaptation Based on Implant Placement Depth

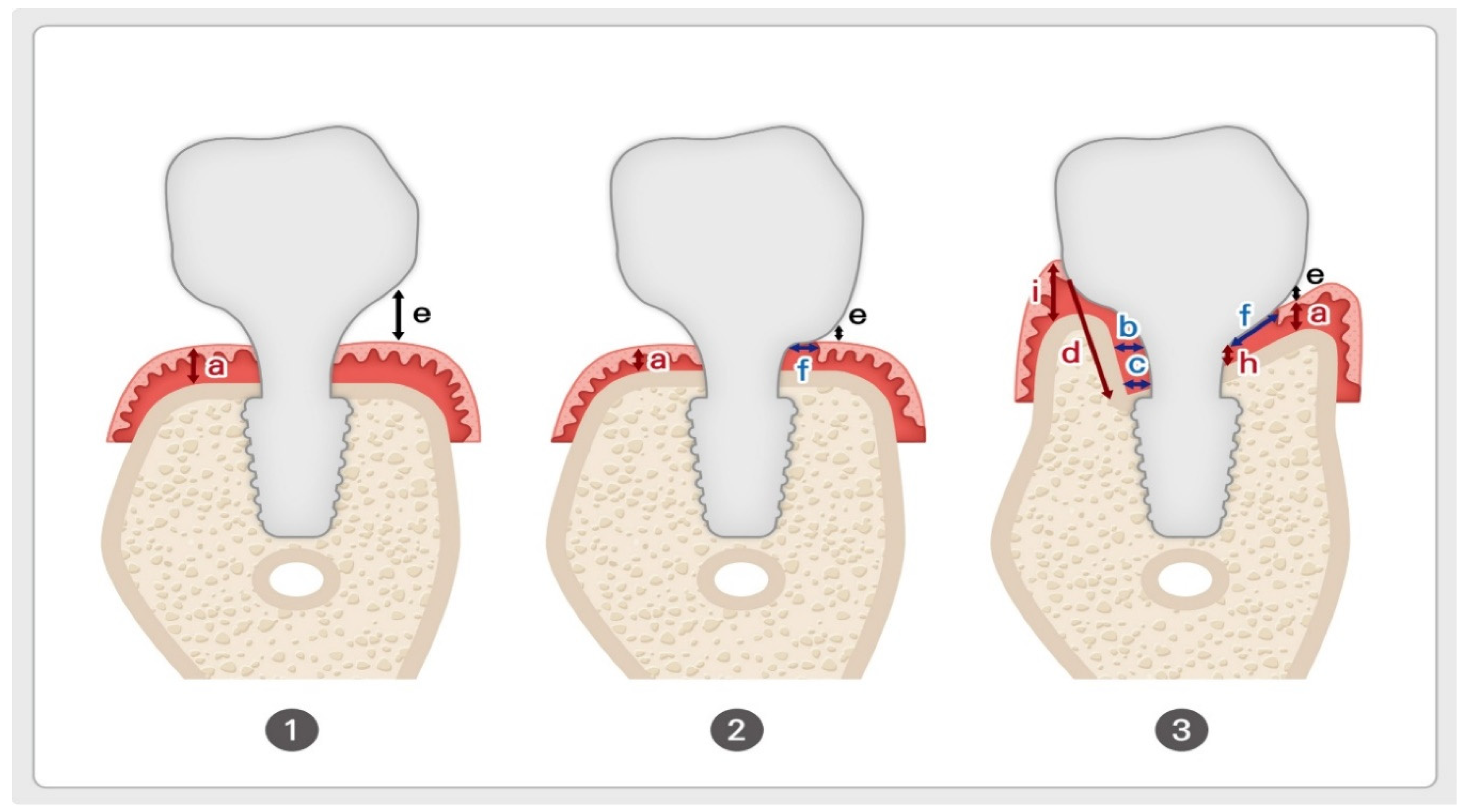

Figure 9 presents three distinct peri-implant soft tissue configurations, demonstrating how different implant placement depths and emergence profile designs influence soft tissue stability, biologic integration, and esthetic outcome.

1. Epi- or Equi-Crestal Placement Without Submucosal Flaring

In this scenario, the cervical contour of the restoration does not extend beneath the mucosa, avoiding soft tissue compression by keeping the flaring region entirely supramucosal.

This results in a void space (e) between the restoration and mucosa, reducing peri-implant soft tissue adaptation but preventing excessive compression.

The soft tissue thickness (a) corresponds to the traditional biologic width model in natural teeth but lacks the connective tissue attachment characteristic of natural dentition.

Due to the absence of horizontal flaring, the emergence profile appears unnatural, with the crown contour remaining narrow until it exits the mucosa.

This design is commonly seen in healing abutment placement and external hex connection implants, where peri-implant soft tissue adaptation occurs only in a vertical dimension.

2. Epi- or Equi-Crestal Placement With Submucosal Flaring

This variation incorporates a submucosal flaring design by allowing the buccal cervical contour of the crown to maintain direct contact with the underlying mucosa, mimicking the emergence profile of natural teeth.

The soft tissue contact distance (f) represents the region where the restoration interfaces with the peri-implant mucosa.

This configuration provides a more natural emergence profile but results in a more abrupt emergence compared to SPI.

However, buccal bone thickness is a critical determinant of soft tissue stability—insufficient buccal bone support may increase the risk of tissue recession or marginal bone loss due to excessive pressure on the mucosa.

Clinicians must carefully balance flaring dimensions and soft tissue adaptation to achieve optimal esthetic and biological outcomes, as a reduced emergence angle has been associated with unfavorable peri-implant soft tissue responses.

3. Subcrestal Implant Placement (SPI) With Transitional Zone Formation

In SPI cases, the subcrestal positioning of the implant leads to a more complex peri-implant soft tissue adaptation, where both vertical and horizontal components influence the biological interface.

Unlike epi- or equi-crestal placements, the horizontal extension of the soft tissue beneath the mucosa generates a distinct Transitional Zone (TZ).

This horizontal adaptation cannot be adequately explained using the traditional biologic width model, as it introduces new tissue dynamics that influence emergence profile stability.

-

This peri-implant soft tissue adaptation is shaped by:

- o

The relationship between the restoration and underlying bone

- o

The width and height of peri-implant soft tissue

- o

The degree of subcrestal positioning

- o

The interplay between connective tissue and junctional epithelium in the TZ

Figure 9.

Variations in Peri-Implant Soft Tissue Adaptation Based on Implant Placement Depth. 1. Epi- or Equi-Crestal Placement Without Submucosal Flaring. The implant restoration maintains a gap (e) between the cervical contour and the underlying soft tissue, preventing tissue compression but resulting in a non-anatomic emergence profile. (a) represents the thickness of epithelium and connective tissue, analogous to the biologic width in natural teeth. 2. Epi- or Equi-Crestal Placement With Submucosal Flaring. The buccal cervical contour of the restoration maintains direct contact (f) with the underlying mucosa, creating a more natural emergence profile. However, adequate buccal bone support is required to prevent soft tissue recession or marginal bone loss due to excessive pressure on the mucosa. 3. Subcrestal Implant Placement (SPI) With Transitional Zone (TZ) Formation. The implant is positioned subcrestally, leading to complex peri-implant soft tissue adaptation with both vertical and horizontal components. The Transitional Zone (TZ) serves as a biologic interface, contributing to peri-implant stability and soft tissue integration. This schematic also introduces key variables that will be discussed in detail later: a, e, f – Same as in (1) and (2); b, c – Representing Soft Tissue Thickness (STT). d – Representing Crest to Restoration Length (CRL). i – Representing Free-Standing Peripheral Soft Tissue Height.

Figure 9.

Variations in Peri-Implant Soft Tissue Adaptation Based on Implant Placement Depth. 1. Epi- or Equi-Crestal Placement Without Submucosal Flaring. The implant restoration maintains a gap (e) between the cervical contour and the underlying soft tissue, preventing tissue compression but resulting in a non-anatomic emergence profile. (a) represents the thickness of epithelium and connective tissue, analogous to the biologic width in natural teeth. 2. Epi- or Equi-Crestal Placement With Submucosal Flaring. The buccal cervical contour of the restoration maintains direct contact (f) with the underlying mucosa, creating a more natural emergence profile. However, adequate buccal bone support is required to prevent soft tissue recession or marginal bone loss due to excessive pressure on the mucosa. 3. Subcrestal Implant Placement (SPI) With Transitional Zone (TZ) Formation. The implant is positioned subcrestally, leading to complex peri-implant soft tissue adaptation with both vertical and horizontal components. The Transitional Zone (TZ) serves as a biologic interface, contributing to peri-implant stability and soft tissue integration. This schematic also introduces key variables that will be discussed in detail later: a, e, f – Same as in (1) and (2); b, c – Representing Soft Tissue Thickness (STT). d – Representing Crest to Restoration Length (CRL). i – Representing Free-Standing Peripheral Soft Tissue Height.

Implications for 3DSTA

These three scenarios highlight the necessity for a three-dimensional soft tissue analysis (3DSTA), as traditional two-dimensional models fail to account for the horizontal components of peri-implant soft tissue adaptation.

In equi- or epi-crestal placements, peri-implant soft tissue remains vertically oriented, allowing a simplified emergence profile evaluation.

In SPI cases, the transitional zone (TZ) adds a horizontal dimension, requiring a more nuanced analytical approach to understand its biologic function.

The 3DSTA model provides a systematic method to quantify peri-implant soft tissue behavior, ensuring predictable soft tissue adaptation and long-term implant stability.

By incorporating 3DSTA principles, clinicians can strategically design peri-implant soft tissue contours, ensuring optimal esthetic integration, biologic sealing, and functional longevity in implant restorations.

New 3-Dimensial Model (3DSTA: 3 Dimensional Soft Tissue Analysis)

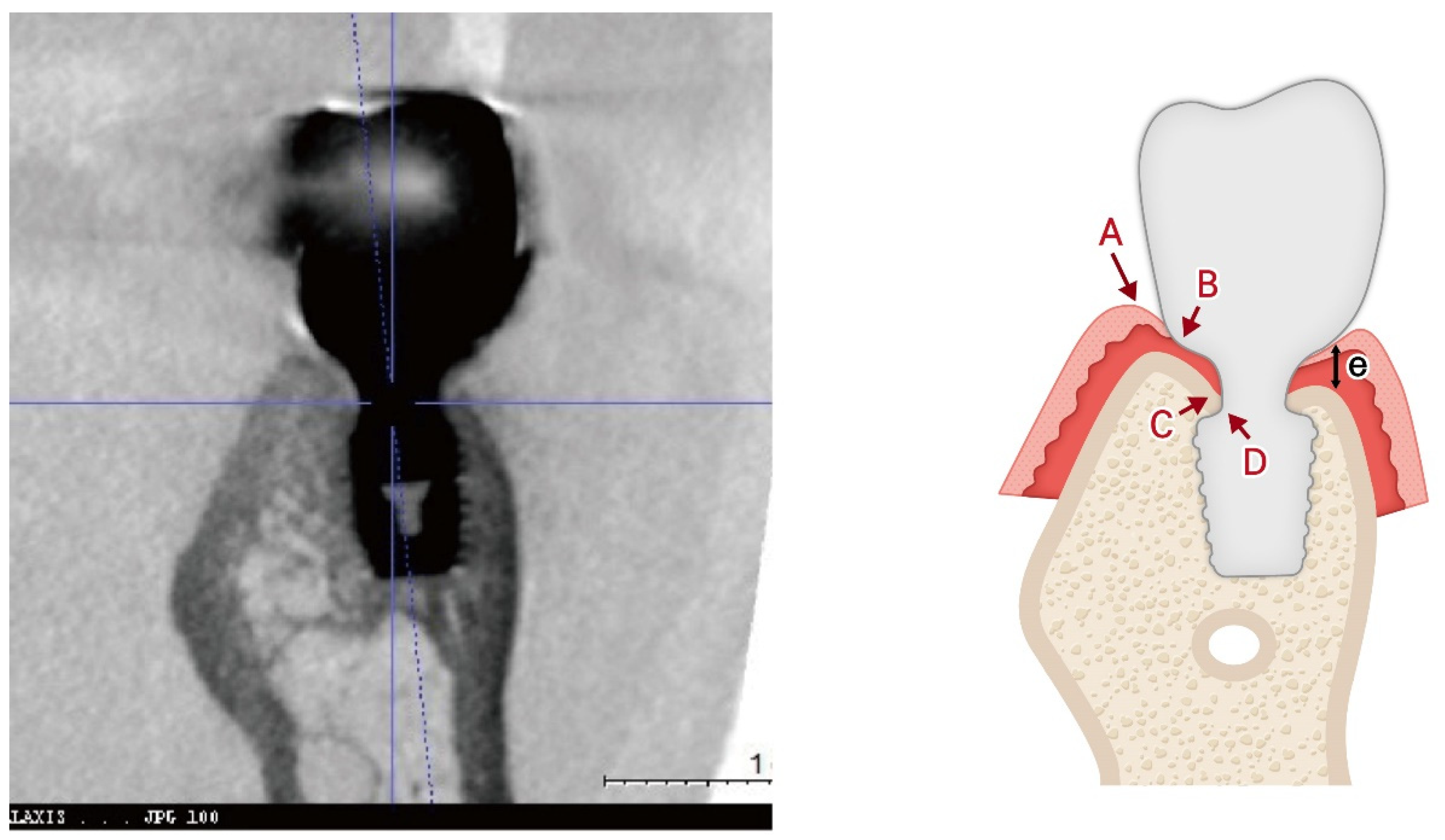

Figure 10 introduces a three-dimensional soft tissue analysis model (3DSTA) designed to quantify peri-implant soft tissue components using CBCT imaging. The left image represents a real CBCT scan, providing the foundation for the schematic. The right schematic model is derived from the CBCT image, outlining the soft tissue structure around subcrestally placed implants (SPI).

Figure 10.

Three-Dimensional Schematic Model for 3D Soft Tissue Analysis (3DSTA). This model, based on a real CBCT image (left), illustrates the key components of peri-implant soft tissue in a subcrestally placed implant (SPI). The schematic (right) highlights three zones: Sulcus Zone (A–B), Transitional Zone (TZ, B–C), and Subcrestal Zone (SZ, C–D). The traditional biologic width (e), observed in equi-crestal implants, is shown for comparison. This model provides a framework for measuring peri-implant soft tissue dimensions using CBCT.

Figure 10.

Three-Dimensional Schematic Model for 3D Soft Tissue Analysis (3DSTA). This model, based on a real CBCT image (left), illustrates the key components of peri-implant soft tissue in a subcrestally placed implant (SPI). The schematic (right) highlights three zones: Sulcus Zone (A–B), Transitional Zone (TZ, B–C), and Subcrestal Zone (SZ, C–D). The traditional biologic width (e), observed in equi-crestal implants, is shown for comparison. This model provides a framework for measuring peri-implant soft tissue dimensions using CBCT.

This schematic divides the peri-implant soft tissue into three key zones:

Sulcus Zone (A to B): The most coronal portion, adjacent to the implant restoration, mirroring the gingival sulcus in natural teeth. This is composed of sulcular epithelium.

Transitional Zone (TZ, B to C): A critical biologic interface that adapts to the implant contour and plays a role in soft tissue stability. It consists of junctional epithelium and connective tissue, forming a functional seal against microbial invasion while maintaining a stable soft tissue attachment.

Subcrestal Zone (SZ, C to D): The deepest layer, positioned below the crestal bone level, supporting long-term peri-implant health. It is composed entirely of connective tissue, providing structural support and acting as a protective barrier for the underlying bone.

Additionally, e represents the traditional biologic width, typically found in equi-crestally placed implants (EPI). This serves as a comparative reference, emphasizing the structural and biological differences between SPI and traditional implant placement.

By segmenting peri-implant soft tissue into measurable zones, 3DSTA offers a systematic approach to assessing soft tissue adaptation, aiding in clinical decision-making and implant design optimization.

New Concepts with Core Hypotheses

Table 2.

Summary of Peri-Implant Soft Tissue Parameters. This table defines key parameters used to characterize peri-implant soft tissue structure and stability. It distinguishes measurable components (CRG, STT) from inferred components (CRL, SSST) and highlights their visibility in CBCT imaging. The table also illustrates how Crestal Restoration Soft Tissue (CRST) dynamically transitions into Self-Sustained Soft Tissue (SSST) when CRG is optimized, ensuring peri-implant health and stability. The reason why some parameters can be measured in CBCT while others cannot is due to the lack of a distinct demarcation between sulcular epithelium and junctional epithelium in radiographic imaging. This boundary can only be precisely identified through histological analysis, which is clinically impractical. However, indirect inferences can be drawn through clinical sulcus depth measurements or by assessing free-standing supracrestal tissue height (STH).

Table 2.

Summary of Peri-Implant Soft Tissue Parameters. This table defines key parameters used to characterize peri-implant soft tissue structure and stability. It distinguishes measurable components (CRG, STT) from inferred components (CRL, SSST) and highlights their visibility in CBCT imaging. The table also illustrates how Crestal Restoration Soft Tissue (CRST) dynamically transitions into Self-Sustained Soft Tissue (SSST) when CRG is optimized, ensuring peri-implant health and stability. The reason why some parameters can be measured in CBCT while others cannot is due to the lack of a distinct demarcation between sulcular epithelium and junctional epithelium in radiographic imaging. This boundary can only be precisely identified through histological analysis, which is clinically impractical. However, indirect inferences can be drawn through clinical sulcus depth measurements or by assessing free-standing supracrestal tissue height (STH).

| Parameter |

Definition |

Component Type |

Visibility in X-Ray |

Measurement/Inference |

| CRST (Crestal Restoration Soft Tissue) |

Peri-implant soft tissue between the crestal bone and implant restoration. |

Vertical & Horizontal |

Partially visible (depends on thickness) |

CRG (vertical) and CRL (horizontal) define its dimensions. |

| CRST (Crestal Restoration Soft Tissue) |

| CRG (Crest to Restoration Gap) |

Vertical distance from the crestal bone to the implant restoration, composed of void and soft tissue. |

Vertical |

Visible (depends on thickness) |

Measured radiologically (CBCT). When optimized, CRG is converted into STT of SSST (TZ and SZ) |

| CRL (Crest Restoration Length) |

Horizontal dimension of the CRST. |

Horizontal |

Partially visible (e.g., palatal side) |

Inferred based on CBCT and visible where tissue is thick enough (e.g., on the palatal side). |

| |

| Parameter |

Definition |

Component Type |

Visibility in X-Ray |

Measurement/Inference |

| SSST (Self-Sustained Soft Tissue) |

Optimized CRST, divided into the TZ and SZ, maintaining peri-implant tissue stability. |

Vertical & Horizontal |

TZ and SZ are inferred zones. |

Vertical component measured with STT; horizontal component inferred using CRL. |

| SSST (Self-Sustained Soft Tissue) |

| TZ (Transitional Zone) |

Elastic soft tissue zone within the SSST, positioned coronally. |

Vertical (STT)

Horizontal (TZL) |

STT visible |

Vertical thickness measured via STT.

TZL ; inferred |

| SZ (Subcrestal Zone) |

Inelastic soft tissue zone within the SSST, located closer to the crestal bone. |

Vertical (STT)

Horizontal (SZL) |

Visible and measurable |

Vertical thickness measured via STT

SZL ; measurable |

Distinguishing Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD), Soft Tissue Thickness (STT), and Self-Sustained Soft Tissue (SSST):

Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD) represents the vertical distance measured from the crestal bone to the restoration interface, encompassing void spaces, epithelial layers, and connective tissue. However, CRD transitions into Soft Tissue Thickness (STT) only when it lies within an optimal thickness range—a hypothetical proposal grounded in clinical observations and outcomes. While the exact “optimal thickness” awaits validation through large-scale statistical investigations and further research, it is not an unvalidated concept. Rather, it carries its own identity as a valid notion derived from observed clinical outcomes.

The distinction between CRD and STT lies in their functional and biological significance. STT refers specifically to the biologically functional thickness of Self-Sustained Soft Tissue (SSST). When measured using radiographic tools such as CBCT, STT can align with CRD only if the CRD falls within the optimal range, where void spaces and epithelial layers are minimal or absent. Conversely, a CRD exceeding this threshold indicates void formation and epithelial downgrowth, which predisposes the peri-implant environment to pocket formation, bacterial infiltration, and inflammation.

Maintaining CRD within its optimal range is crucial for fostering the formation of SSST—a biologic structure composed of the Transitional Zone (TZ) and Subcrestal Zone (SZ). SSST serves as a stable connective tissue interface that resists epithelial migration, creates a protective seal around the implant, and supports long-term peri-implant health.

Key distinctions:

CRD is a measurable vertical parameter influenced by implant placement depth and prosthodontic design. It reflects a composite dimension that may include voids and epithelial layers, depending on its alignment with the optimal thickness range.

STT, on the other hand, conveys the biologically functional tissue thickness of SSST. It is valid only when void spaces are absent, and the connective tissue is structurally optimized to support peri-implant health.

Although both CRD and STT can be measured radiographically, their implications differ. CRD is a descriptive vertical measurement, while STT represents a biologically functional dimension. The concept of optimal thickness, though awaiting broader validation, is firmly rooted in clinical experience and provides a meaningful framework for understanding the biological behavior of peri-implant tissues.

Additional Explanation:

These notions of CRD and STT become especially evident in subcrestally placed implants (SPIs). In other types of implant placements, such as equi-crestally placed implants (EPIs), these concepts are less apparent to clinicians and researchers. However, this does not mean CRD and STT are absent in non-SPI cases; they may simply be more subtle and require careful and precise investigation to be recognized.

For instance, depending on the angulation formed by the slope of the crestal bone and the design of the prosthodontic restoration, CRD and the phenomena of STT may become evident even in EPI cases. Similarly, in SPIs, these features may be less pronounced under certain conditions. For example, in SPIs, placing a broad gap between the restoration and the crestal bone may reduce the prominence of CRD and STT, diminishing their functional role in peri-implant tissue behavior.

These examples highlight that the visibility and impact of CRD and STT are influenced by clinical factors, including implant placement depth, bone topography, and prosthodontic design. Such variability underscores the need for further exploration and standardization to better understand their implications across diverse implant scenarios.

SSST in SPIs:

Self-Sustained Soft Tissue (SSST) in Subcrestally Placed Implants (SPIs) is a biologic structure that can be conceptualized as a three-dimensional model integrating vertical and horizontal components:

Vertical component: Represented by Soft Tissue Thickness (STT), which corresponds to the optimized Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD). This ensures sufficient connective tissue thickness to protect the peri-implant interface and maintain peri-implant health.

-

Horizontal component: Defined by the Transitional Zone Length (TZL), which establishes a robust biologic seal around the implant restoration.

- -

In subcrestally placed implants (SPIs), the horizontal dimension of SSST is exclusively defined by the Transitional Zone Length (TZL), which contributes to the biologic sealing function.

- -

Supracrestal Tissue Height (STH) is traditionally defined as the vertical distance from the crest tip to the zenith of the free-standing peripheral soft tissue coronally. However, in the unique environment of SPIs, a new term—Total Soft Tissue Distance (TSTD)—is proposed to better describe this composite concept.

- -

TSTD in SPIs encompasses both the original vertical distance (STH) from the crest tip to the zenith of the free-standing peripheral soft tissue and the TZL, which is essential for the biologic functionality of SSST.

- -

In SPIs, TZL serves as the primary horizontal connective tissue component, while the free-standing peripheral soft tissue height reflects the coronal soft tissue extending beyond the constricted and contained environment surrounded by the underlying crestal bone, adjacent implant restorations, or neighboring teeth.

- -

TZL is difficult to measure clinically because the boundary between the sulcular epithelium and junctional epithelium cannot be distinguished in a clinical setting. As a result, TZL is considered a histological component rather than a direct clinical parameter. However, if STT at the TZ is statistically validated, it may become possible to theoretically infer and measure TZL in clinical practice.

Subcomponents of SSST:

The Subcrestal Zone (SZ) is formed at the interface between the implant and the neighboring subcrestal bone when the implant is placed subcrestally. Despite its clinical importance, the existence of this zone has historically been overlooked. Early implant research and clinical practice intentionally neglected SZ because it was assumed that this area must achieve osseointegration, and any soft tissue engagement was considered undesirable or contrary to the ideal of osseointegration. Fibro-osseointegration was seen as contradictory to the foundational principle of implant success.

However, long-term clinical observations have demonstrated that this zone exhibits remarkable stability, even in the absence of strict osseointegration. The SZ arises when a space exists between the implant fixture or restoration and the neighboring subcrestal bone. This phenomenon is particularly noticeable in bone-level implants placed deeply subcrestally, where restorations are designed to maintain an intimate relationship with the neighboring subcrestal bone without cutting or removing it. This stability is especially evident when matching abutment techniques are employed. Based on Won’s study of 20 cases performed with SPIs incorporating internal platform switching (IPS), the estimated thickness of the SZ is approximately 0.3 mm.

- 2.

Transitional Zone (TZ):

The Transitional Zone (TZ) represents the coronal elastic connective tissue zone that dynamically adapts to the implant restoration, playing a vital role in maintaining a tight biologic seal. Unlike the Subcrestal Zone (SZ), which is primarily a biologic response, the formation and characteristics of the TZ are predominantly influenced by clinical design and intentional prosthodontic planning.

The TZ is shaped by:

The thickness of the TZ, represented as Soft Tissue Thickness (STT) at the TZ, theoretically ranges from 0.3 mm to 1.0–1.5 mm in width, depending on restoration design and its interaction with the crestal bone. Acting as an elastic connective tissue zone, the TZ ensures a secure biologic seal around the restoration, helping to protect underlying peri-implant structures.

Need for Further Investigation:

Further studies are needed to clinically investigate the STT of TZ through statistical analysis. The Self-Sustained Soft Tissue (SSST) begins where the junctional epithelium starts. If Crest to Restoration Gap (CRG) is excessive, the sulcular epithelium is present along with a void (sulcus facing sulcular epithelium). However, once the sulcular epithelium is no longer required, the junctional epithelium must begin.

The Junctional Epithelium and Connective Tissue as a Functional Unit:

Due to histologic similarities between junctional epithelium and connective tissue, a single layer of junctional epithelium may extend over the connective tissue of the TZ. Given this structural and functional overlap, the junctional epithelium and the connective tissue of the TZ can be considered a single functional unit—integrating both biologic function and structural harmony in subcrestally placed implants.

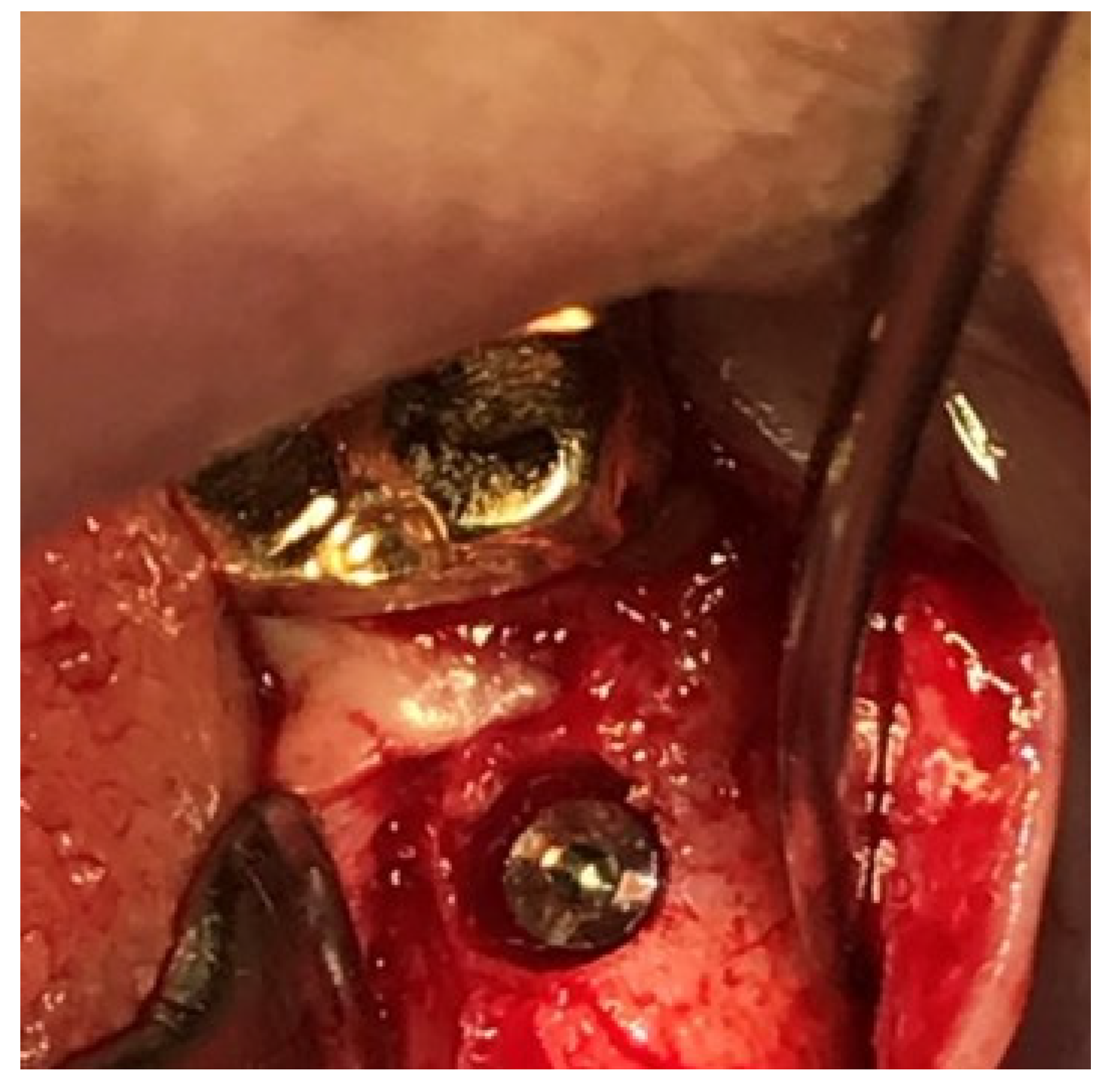

Figure 11 illustrates the step-by-step process of integrating pre-fabricated abutments with subcrestally placed healing abutments and the corresponding biological response of peri-implant soft tissue.

Figure 11.

Procedural Steps for Matching Ready-Made Abutments with Subcrestally Placed Healing Abutments. The upper images include X-rays and clinical photographs, illustrating the process of matching ready-made abutments with subcrestally placed healing abutments. The lower images highlight the Transitional Zone (TZ) and Subcrestal Zone (SZ), showing their structural and functional differences. The TZ appears pink and elastic, while the SZ is paler and less elastic. Notably, the SZ forms after using a matching healing abutment due to its proximity to the adjacent subcrestal bone. Despite its thin structure, the SZ remains functional and stable, possibly due to its protected position beneath the TZ.

Figure 11.

Procedural Steps for Matching Ready-Made Abutments with Subcrestally Placed Healing Abutments. The upper images include X-rays and clinical photographs, illustrating the process of matching ready-made abutments with subcrestally placed healing abutments. The lower images highlight the Transitional Zone (TZ) and Subcrestal Zone (SZ), showing their structural and functional differences. The TZ appears pink and elastic, while the SZ is paler and less elastic. Notably, the SZ forms after using a matching healing abutment due to its proximity to the adjacent subcrestal bone. Despite its thin structure, the SZ remains functional and stable, possibly due to its protected position beneath the TZ.

In the upper images, both X-ray and clinical photographs capture the procedural workflow involved in this process. These images demonstrate how ready-made abutments are carefully matched with subcrestally placed implants. The application of healing abutments plays a crucial role in shaping peri-implant soft tissue, ensuring a well-adapted emergence profile that facilitates long-term soft tissue stability.

The lower images provide a closer look at the peri-implant soft tissue structure following this process. Two distinct zones can be observed: the Transitional Zone (TZ) and the Subcrestal Zone (SZ). The TZ appears pink and elastic, indicating its dynamic adaptation to the implant’s emergence profile. In contrast, the SZ is paler and less elastic, positioned closer to the crestal bone, where it serves a more structural and stabilizing role. Unlike the TZ, the SZ is not naturally present but is formed as a result of healing abutment placement, developing due to its proximity to adjacent subcrestal bone.

Despite its thinness, the SZ remains functionally stable, likely benefiting from its deep subcrestal location, where it is protected from excessive mechanical stress. The overlying TZ may further contribute to this protection, reinforcing the structural and biological stability of the peri-implant soft tissue.

This figure underscores the importance of healing abutments in peri-implant tissue adaptation, revealing how distinct soft tissue zones develop around implants and contribute to long-term stability and biological integration.

Confirmation of Self-Sustained Soft Tissue (SSST) Existence

The distinct separation of the Transitional Zone (TZ) and Subcrestal Zone (SZ) in Figure 11 provides strong visual and clinical evidence supporting the concept of Self-Sustained Soft Tissue (SSST). The presence of the SZ beneath the peri-implant mucosa, maintaining its stability without epithelial coverage, challenges traditional assumptions that peri-implant soft tissue must always be epithelialized for long-term functionality.

This observation aligns with clinical experiences where SZ formation is consistently observed in subcrestally placed implants (SPIs), particularly in cases where healing abutments are carefully matched. The functional integrity of the SZ—despite its thinness and subcrestal location—demonstrates that SSST can exist as a stable biological structure without requiring epithelial coverage.