Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

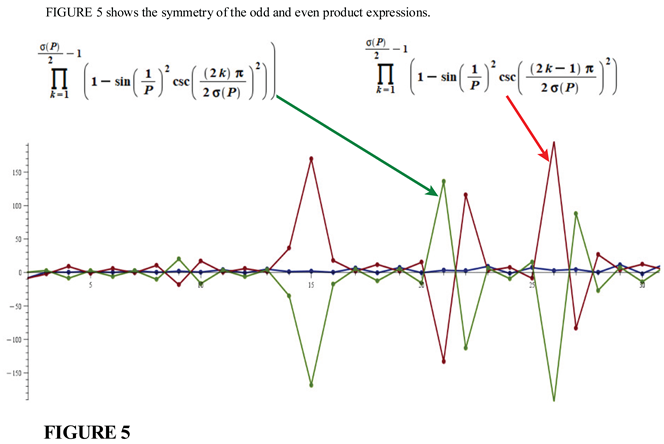

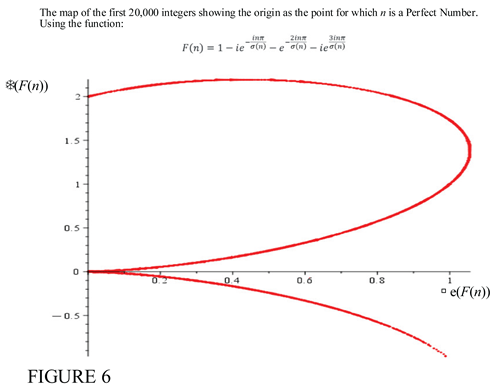

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

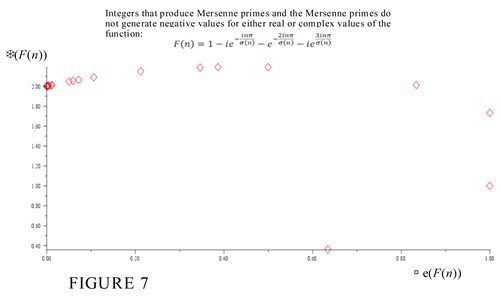

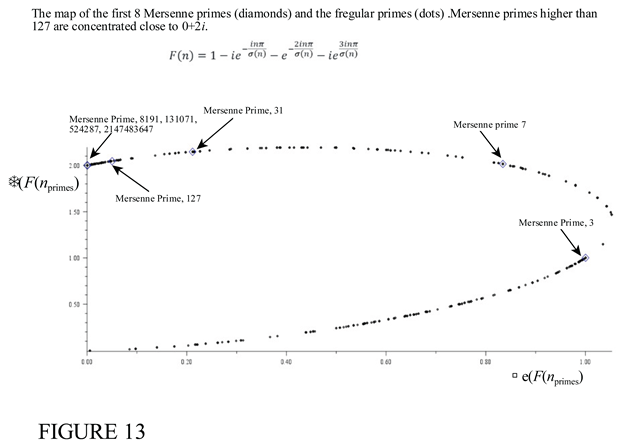

2. Mersenne Numbers

3. The Invariance of the Gamma Function to Substitution

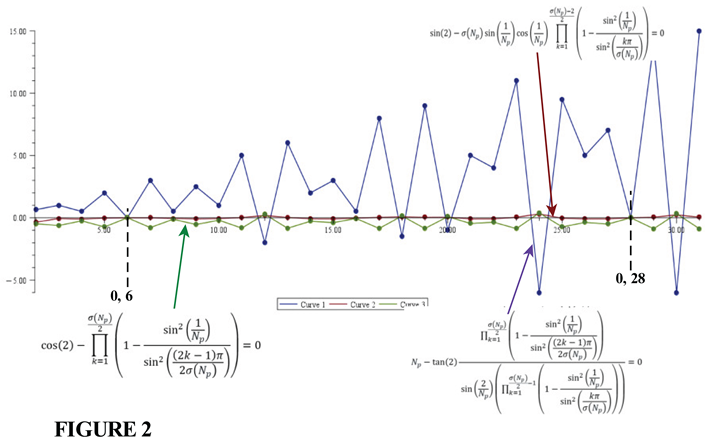

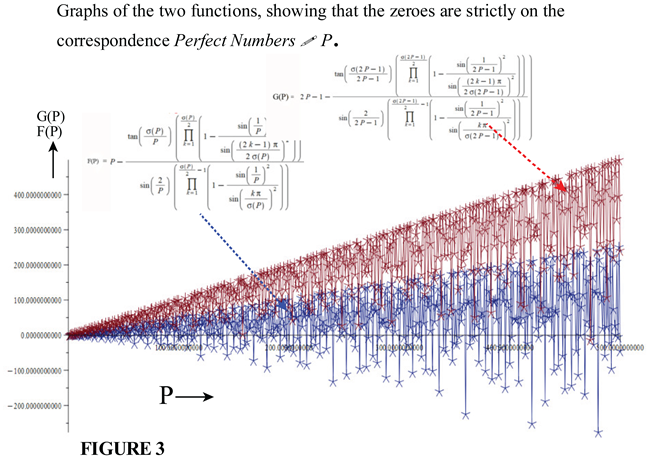

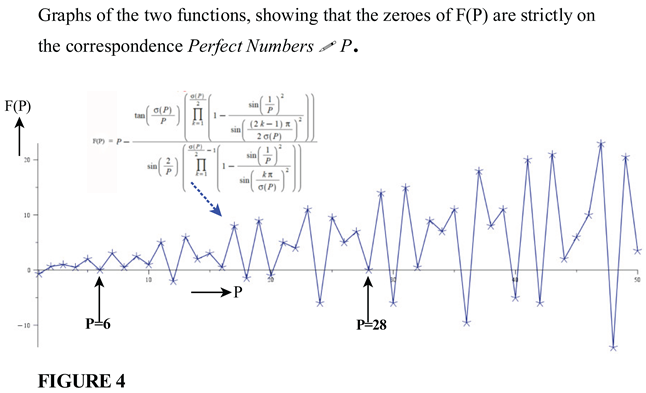

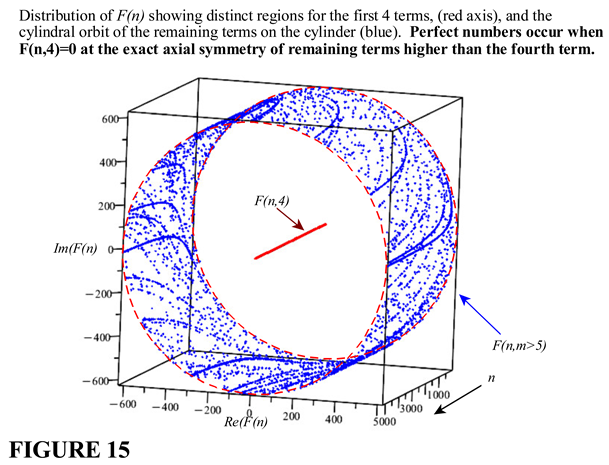

4. Application of the Trigonometric Function to Perfect Numbers

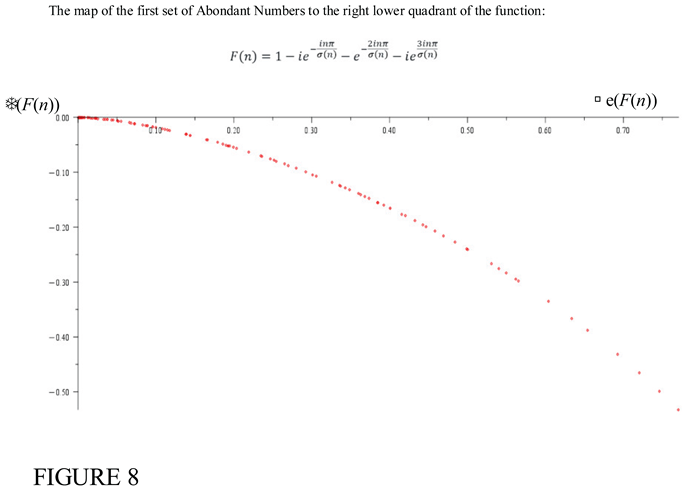

5. The General Relation That Captures the Behavior of Abondant Numbers, Perfect Numbers and Deficient Numbers

- For perfect numbers, and the relation (33) vanishes.

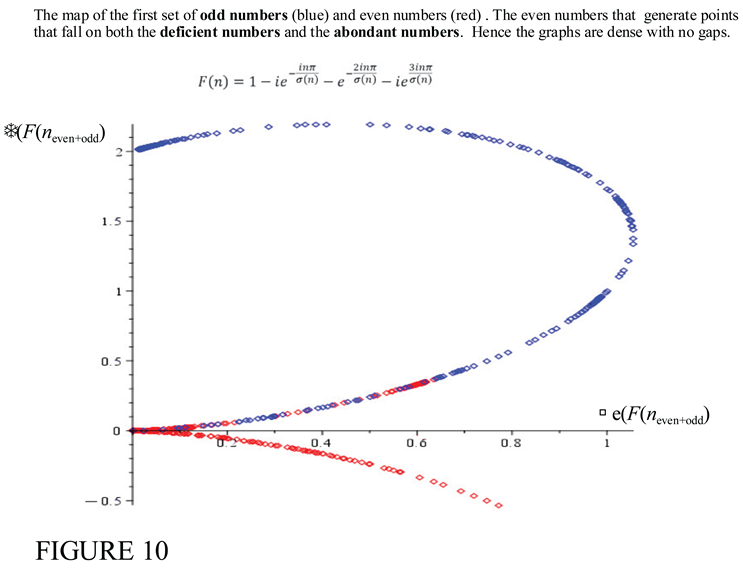

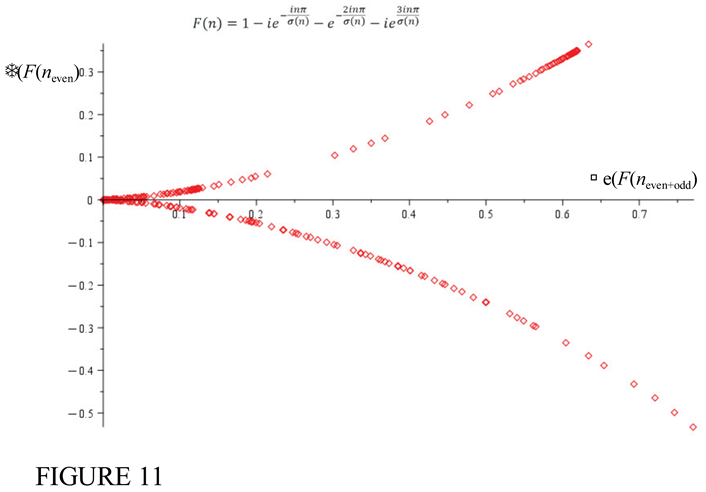

- For abondant numbers, and the relation does not vanish but generates negetaive imaginary values for

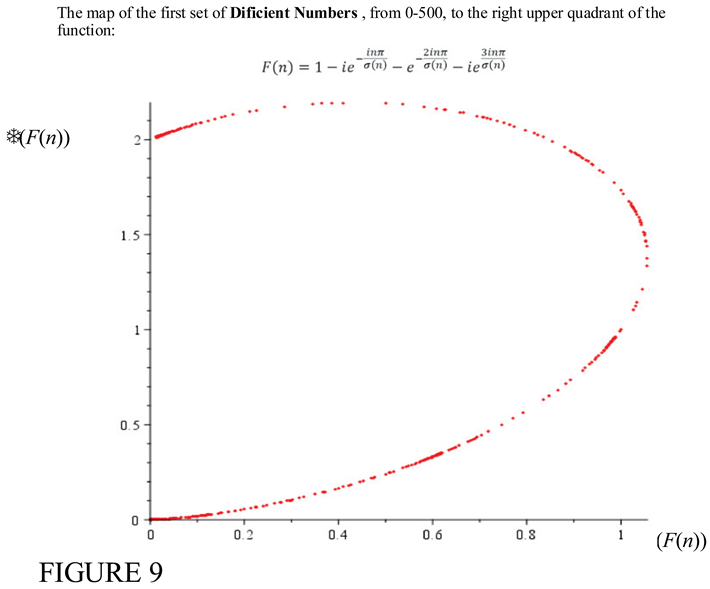

- For deficient numbers, and the relation does not vanish but generates positive imaginary values for

6. The Extension of TH Function F(n) to a General Series Form

| k | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 |

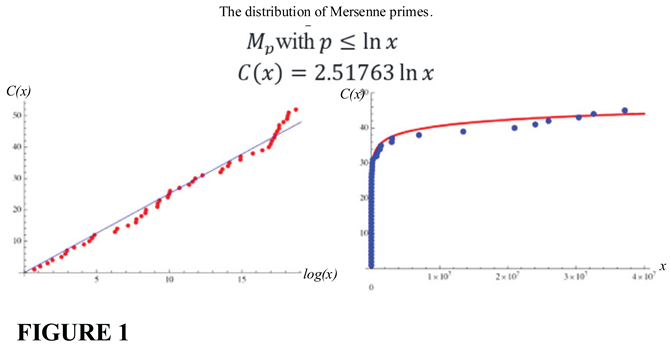

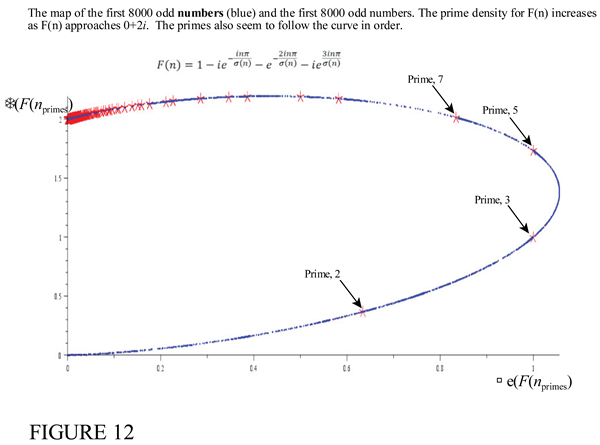

7. Analytic Mersenne Density and Infinitude

8. Application of the Trigonometric Function to Sophie Germain Numbers

- Fabry/Hadamard (sparsity ↔ analytic behavior) [5]: The Fabry and Hadamard theorems, particularly the gap theorems, are central results in complex analysis concerning the analytic continuation of power series with “lacunary” or gapped coefficients. Both theorems establish conditions under which a power series cannot be analytically extended beyond its circle of convergence, which then becomes a “natural boundary” for the function.

- Lindemann–Weierstrass Theorem (1885) [6]:

- c.

- Siegel–Shidlovsky Theorem (1956) [7]

- d.

- Baker’s Theorem (1966) on Linear Forms in Logarithms [8].

- e.

- Nesterenko’s Theorem (1996) [9] on the algebraic independence of

9. The Quadratic Discriminant Lemma for Special Infinitude

- By the Lindemann–Weierstrass Theorem [6] (1885), if a is a non-zero algebraic number, then sin(a) and cos(a) are transcendental. Hence, is transcendental for any algebraic ; in particular cot(2) is transcendental.

- Each Bernoulli number is rational, and are integers.Therefore every partial sum Is an algebraic number.

- If were finite, would stabilize at some algebraic value .Since a finite algebraic sum cannot equal a transcendental constant,equality is impossible for finite .

- Consequently the equality can hold only in the limit of an infinite series, implying that is infinite.

10. Conditional Quadratic Discriminant Theorem for Special Infinitude

- a)

- Discriminant condition.

- b)

- Finite-set contradiction.

- c)

- Analytic necessity.

- d)

- The analytic identity demands a real balance.

11. Interpretative Remark

12. Remarks and Positioning

- a)

- Novelty. The Main Theorem, and Theorem 1 are not a re-statement of any single classical result; it’s a combination of positivity, analytic identity, discriminant collapse ⇒ infinitude of each class. The closest analogues are

- b)

- Fabry/Hadamard (sparsity ↔ analytic behavior) [5]: The Fabry and Hadamard theorems, particularly the gap theorems, are central results in complex analysis concerning the analytic continuation of power series with “lacunary” or gapped coefficients. Both theorems establish conditions under which a power series cannot be analytically extended beyond its circle of convergence, which then becomes a “natural boundary” for the function.

- c)

- Tauberian methods (analytic facts ⇒ density/infinitude): Tauberian methods use analytic properties of a function to deduce properties of its underlying sequence of coefficients. In analytic number theory, this approach often uses a Dirichlet series and facts about its analytic continuation to determine the density or infinitude of an arithmetic sequence.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- On the Density of the Abundant Numbers, Paul Erdös, Journal of the London Mathematical Society: Volume s1-9, Issue 4, Pages: 241-320, October 1934. [CrossRef]

- 2. Leonhard Euler; “Institutiones calculi differentialis cum eius usu in analysi finitorum ac doctrina serierum, volume 1”. [CrossRef]

- C.F. Gauss; “Theoria residuorum biquadraticorum, Commentatio secunda;” Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wis-senschaften zu Göttingen, 1863, 95 - 148.

- Gradshteyn, I.S.; Ryzhik, I.M. Table of Integrals, Series, and Products, 7th ed.; Zwillinger, D., Jeffrey, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007.

- Michael M. Anthony; Consequences of Invariant Functions for the Riemann hypothesis; SCIRP; Document ID: 5302512-20241007-102003-9957. 2024.

- C. Lindemann, Über die Zahl π, Math. Ann. 20 (1882) 213–225. [CrossRef]

- K. Weierstrass, Zur Theorie der Abelschen Functionen, J. reine angew. Math. 90 (1881).

- C. L. Siegel, Über einige Anwendungen diophantischer Approximationen, Abh. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. Berlin. Phys.-Math. Kl. (1929).

- Baker, Linear Forms in the Logarithms of Algebraic Numbers, Mathematika 13 (1966) 204–216. [CrossRef]

- Yu. V. Nesterenko, Modular functions and transcendence questions, Mat. Sb. 187 (1996) 65–96. [CrossRef]

- T. Rivoal & W. Zudilin, Diophantine properties of numbers related to ζ(2), Math. Ann. 326 (2003) 705–721. [CrossRef]

- Thomas Muller. Study of combinatorial objects in higher dimensions. Discrete Mathematics [cs.DM]. Université de Bordeaux, 2025. English. ffNNT: 2025BORD0087ff. fftel-05263156f.

- Patrice Lass`ere and Nguyen Thanh Van; Hadamard Gap Theorem and Over convergence for Faber-Erokhin Expansions;Institut de Math’ematiques, Universit’e Paul Sabatier,118 Route de Narbonne, 31062 Toulouse Cedex 9, France.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).