1. Introduction

The search for a general formula to determine the Sophie Germain prime is an ongoing challenge in mathematics. This paper produces a test for the Sophie Germain/Safe prime set. Sophie Germain primes are generators of “Safe primes” , , where is a Sophie prime. For generality, we will use when we refer to a prime. Not all primes can generate a Safe prime . For example, the Sophie Germain primes, [3, 5, 11, 23, 29, 41, 53, 83, 89, 113, 131, 173, 179, 191, 233, 239, 251, 281, 293, 359, 419, 431, 443, 491, 509, 593, 641, 653, 659, 683, 719, 743, 761, 809, 911, 953], are examples that generate Safe primes. It is extremely difficult to find the Sophie Germain primes without tedious factorization, since the known set of Sophie Germain primes, like the Mersenne primes are separated by long distances of non-conforming primes.

In this paper, a novel set of relations are developed for the Sophie Germain primes using the product Gamma-function, denoted as

, first introduced by Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler [

1] 1729. Euler’s deep insights into

-function led to numerous results that provide key insights into many fields of mathematics including Probability theory and Statistics. Other major contributions to the development of the

-function used in this paper were developed by Carl Freidman Gauss [

2]. Gauss’s work led to the famous reflection formula of the

-function. A key insight into the

-function is its multiplicative nature. New results will be presented in this paper resulting from the properties of the

-function . So far, there has been little development in the additive representation of the

-function as a series of simple terms.

The

product-form of the

-function due to Gauss, provides further insights into many relations that will be developed in this paper. The product form is given by, [

4], p. 896:

Certain invariant relations of the product

-function will be developed in this paper to show the connections of the

-function to other functions. The

-function of Gauss is given in [

4], p.1038. It is related to the

-function reflection formula developed by

Other relations exist that relate the two functions using Bernoulli numbers. These relations are well studied, and they provide a wealth of information in Number theory and many disciplines in Mathematics. In this article, I show new relations that govern Sophie Germain primes. All these special integer relations are connected in precious way by powers of .

2. Sophie Germain Numbers.

A Sophie Germain prime is a prime number for which is also prime.

For example, the following set are Sophie Primes, :

[3, 5, 11, 23, 29, 41, 53, 83, 89, 113, 131, 173, 179, 191, 233, 239, 251, 281, 293, 359, 419, 431, 443, 491, 509, 593, 641, 653, 659, 683, 719, 743, 761, 809, 911, 953]. Their corresponding “Safe primes” :

[7, 11, 23, 47, 59, 83, 107, 167, 179, 227, 263, 347, 359, 383, 467, 479, 503, 563, 587, 719, 839, 863, 887, 983, 1019, 1187, 1283, 1307, 1319, 1367, 1439, 1487, 1523, 1619, 1823, 1907]

These primes were named after Marie-Sophie Germain (1776–1831), one of the earliest prominent female mathematicians in modern Europe. Sophie Germain’s study of such primes emerged from her work on Fermat’s Last Theorem (FLT).

In 1820, she corresponded with Carl Friedrich Gauss and developed a method that became known as the Sophie Germain Criterion for FLT. Her theorem stated that if there exists a prime p such that no two nonzero power residues modulo differ by 1, then Fermat’s equation has no nontrivial integer solutions. This result is one of the first partial proofs of FLT for infinitely many exponents. To construct such primes, Germain identified the condition being prime, leading to the definition used today.

After Germain, her primes were studied sporadically, often in connection with residue properties and FLT.

20th Century: Interest revived in the context of cryptographic key generation, since both and being prime yield strong cyclic groups for public-key systems (e.g., in Diffie–Hellman).

Modern research: It remains unproven whether infinitely many Sophie Germain primes exist, though it’s strongly conjectured — analogous to the Twin Prime Conjecture. The Hardy–Littlewood Conjecture (1923) predicts their asymptotic distribution:

where

is the twin-prime-constant. This connection is an aspect that I will explore as a diversion to Twin Prime, where if

is a prime, then

is also a prime.

Sophie Germain primes form the seed set of safe primes, which in turn are vital to cryptographic group theory.

They are also structurally related to twin primes and Mersenne primes, since each involves coupling primes through multiplicative or additive relations. My work, aims to show these are harmonic subclasses of a deeper lattice—suggesting an analytic reason for their infinitude. As with Mersenne primes, it is conjectured that there exist an infinite number of Sophie Germain primes.

3. The Invariance of the Gamma Function to Substitution .

I first want to introduce the curious fact that any function with a relational product

can be represented by the Sums of Divisor function

. Here is a simple example:

we can put

and so,

we can put

then, a Perfect number

has the relation:

Here is another example:

If

we can put

and so, applied to the formula [

3], p.41:

Interestingly,

and

, differentiate between odd and even values of

Since primes have

an even number, and

is always even except for the prime 2, the relations

does not apply to primes! Since

For example,

By using the sum of divisor function, for Perfect numbers,

the even trigonometric relations

apply, but the relations,

do not apply, so we can put in (8),

. The fact that the sum of divisor function

can be manipulated this way leads to some interesting formulas that can produce significant and unexpected results. See [

5].

4. Application of the Trigonometric Function to Sophie Germain Numbers.

A Sophie Germain primes

is defined as a number for which

Consequently, since both numbers are primes, we have

This is very intimately related to Perfect numbers

were,

Hence for, example, in (8), putting

then, we have

LEMMA 1: The rational trigonometric functions determine

This is the relation for Perfect Number, and so we arrive at: If

is a Perfect number, then, the equality applies only when. Since

, we have,

Hence the rational functions of the function in the trigonometric functions encodes this behavior of various types of numbers classes.

For Sophie Germain primes,

we have:

Then, since

Equation (20) only holds for Sophie Germain Primes . Hence, we find that (18) behave distinctly for the sets of Mersenne primes that yield Perfect numbers , while (20) behaves distinctly for Sophie Germain primes . The connection between the two suggest that the infinitum condition applies equally to both sets of numbers if it applies to one or the other. Perfect numbers are dealt with in a yet unpublished paper “There are infinitely many Mersenne Primes”, MDPI: Manuscript ID:mathematics-3942588.

The relations (20) hold exclusively for all Sophie Germain Primes. The right-hand side of (20) depends on implicit rational relationships between and It is clear that the basic rational trigonometric functions capture the properties of special prime integers. We now explore the general forms of trigonometric and exponential forms that capture Sophie Germain Primes.

5. Structural Difference Between σ(p) and (p + 1) for Special Primes.

For a prime

,

. At first glance,

and

look identical for all mathematical operations. However, when

is treated functionally inside a product operation,

and in a sum operation

over primes, the distinction is that

belongs to a

multiplicative arithmetic function, while

is just a linear term. Consider a trigonometric product expression such as:

Although we know that

is numerically correct for primes, when the

is inside a broader arithmetic context, especially if the product includes composite arguments or convolution terms, the product operation changes how the function expands when distributed through summation or logarithmic differentiation. That’s because σ satisfies,

= for coprime

. The linear combination of

. does not extend multiplicatively. If a product expression depends on multiplicative structure, replacing

with

breaks that property and alters convergence, periodicity, or symmetry. Trigonometric functions like sin, cos, tan, are periodic and analytic, but when you plug in an arithmetic function, the periodicity couples to the multiplicative nature of

. This behavior however is not true outside the fields of the product operation or the sum operation. This invariance in the product forms is highlighted by the following theorem due to the Author. See [

5].

Theorem 1.

Let represent one integer factor of , then, if,

is not a number theoretic function,

is invariant with respect to choices of any other factors of .

The significance of the Theorem 1, is its consequences for prime numbers, and their relations to functions like the-function and the sum of divisors function,and primes.

PROOF:

Let

be some

integer factor of

-factors a real or complex function

Then,

The Gauss gamma product formula is a simple relation given by:

Then, since is an integer-factor of we have, putting in

. Then,

If there any other integer factor labelled here

then, the substitution

leaves

invariant. However, this is also true for any integer factors,

of

then, for any

remains invariant to the substitutions

It is clear that inside the product terms, we have a different set of rules. Hence the Corollary applies in the sense that if is a non-integer number theoretic function, then the invariance does not apply. However, when we consider rational functions outside of the product, we find that simple arithmetic operations do apply, hence, (20).

6. The Relation of the Product Gamma Function to Primes.

From the Gauss

-product formula,

It is clear that the following relations are equal,

Then, for all real numbers

,

Since, for all primes,

,

from (28), we get for all primes,

:

and so, (29) is not invariant to the substitutions,

, unless

7. The General Relation That Captures the Behavior of Sophie Germain Primes.

A Sophie Germain Prime,

, generates another prime

, . Using (29) for both primes we get:

Lemma 1: Analytic Reduction for Sophie Germain Primes Pairs.

Let be a prime with a prime also, then (31) holds. To prove this, see SECTION 9 above using the Weierstrass-Euler Expansion to determine “primeness”. Relation (31) holds true for all Sophie primes sets .

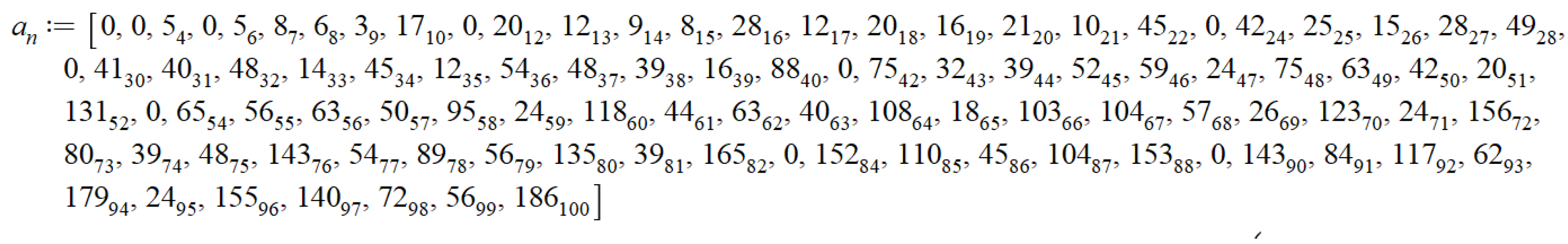

Now in general, for any

, we set:

The values of

, for

are shown in

Table 1 below, with

only for Sophie primes.

It is clear that in (32) , =0, for the Sophie Germain primes :

[3, 5, 11, 23, 29, 41, 53, 83, 89, 113, 131, 173, 179, 191, 233, 239, 251, 281, 293, 359, 419, 431, 443, 491, 509, 593, 641, 653, 659, 683, 719, 743, 761, 809, 911, 953].

Hence the dual prime condition gives us the correct result Sophie Germain primes in (30).

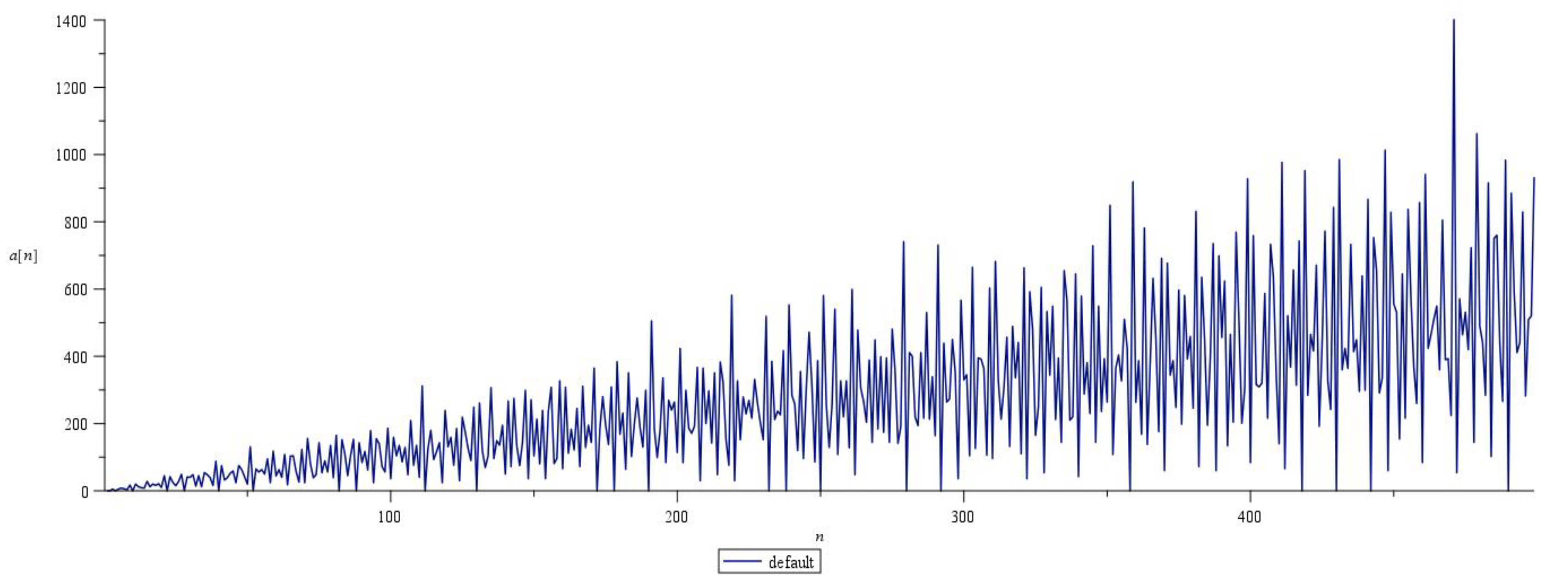

The Plot in

Figure 1 shows the values of

It is clear that the average trend for increases with increasing

The Sophie relation :

is analogous to the Perfect number relation:

This allows us to define a new sort of Sophie Perfect number with the relation (33) and (34). However, the product formulation is not invariant to the substitution of in (33) due to internal cancellations in the terms, and further the coupling , destroys the definition of the “Safe Prime”, since is not a safe prime except for certain values of Hence we need the proper transformation to make the substitution: in (33).

The invariance of (34) to the substitution

, is a key property of the coupling invariance allowed for the unique relation for tan(2).

In-fact the (35) gives exact results when

Hence in the Sophie world, a phase doubling occurs replacing the shift, is a Sophie perfect number if

Defining a Sophie Perfect Number .

Let

for some prime

that also satisfies

a prime. Then,

In classical number theory, an integer

is perfect if

This relation expresses an eigenvalue equation under the multiplicative operator

Perfect numbers thus correspond to the fixed points of a multiplicative scaling by 2. Sophie Germain primes introduce an additive and multiplicative relationship between primes

:

This reveals an arithmetic 2:1 resonance between

and

The analogue of a Sophie perfect number

, and a Perfect Number

can be summarized in the following

Table 2:

Hence, the Sophie Transform corresponds to a phase-doubling trigonometric transform—a discrete analogue of the Fourier dilation symmetry ). Perfect numbers represent amplitude-doubling; Sophie-perfect numbers represent frequency-doubling within the divisor-sum spectrum.

8. Defining the Sophie Transform

Define an operator

(the Sophie transform), acting an arithmetic function

such that :

Then the Sophie condition becomes a harmonic eigenvalue relation:

and

is an eigenfunction of the Sophie Transform

with eigenvalue 2.

| Analogue |

Transformation |

Commonality |

| Sophie transform |

|

The Sophie transform sits between the Mellin(scaled based) and the Hadamard (binary based) transforms. It doubles the index spacing while adding 1 – a quasi affine map on the number line. |

| Mellin Transform |

|

Eigenvalue scales with multiplicative factor |

| Dirichlet Convolution |

|

Multiplicative domain, uses this. |

| Walsh-Hadamard Transform |

Binary doubling of input |

Discrete parity relation similar to |

| Fourier on Cyclic groups |

Periodic phase doubling |

Same as 2:1 harmonic resonance seen in Sophie Perfect numbers |

Theorem1: There are an infinite number of Sophie Germain Primes.

Analytic Sophie Density and Infinitude.

Setup: From [

4], p.42, 1.411 (7) we find an expression for

:

Fix Partition , into disjoint classes , and where is the set of Sophie primes with a prime, and .

Put in (34), then, for Sophie primes,

Note and for

Definition (analytic Sophie density).

With the set up above, at a fixed suppose the following holds true:

(H1) (Regularity/positivity of coefficients).

Each summand is positive and satisfies the classical Bernoulli-Zeta representation:

Hence,

(H2): (Analytic density at ). The decomposition of ields a normalized quadratic identity in the as shown in LEMMA 2, only if LEMMA1 holds.

(H2): (Single-valuedness and discriminant collapse). Since is single valued, the discriminat of the quadratic in LEMMA 2 vanishes.

Proof Sketch:

Absolute positivity and conditional subtraction.

By (H1), , and . The analytic value may be negative (e.g. ), which arises from subtracting the strictly positive from .

Quadratic Normalization.

(H2) encodes the partition into a quadratic in

:

Since and , we have and finite and nonzero.

Discriminant collapse and consistency.

By (H3), . Solve for : the two roots coincide, so the quadratic exactly reproduces .

Contradiction from Finiteness.

Assume , is finite. Then is a fixed positive constant, hence is fixed. Meanwhile is also fixed. The identity becomes a rational equality among strictly positive finite constants. But this equality must be compatible with the sign of (e.g. negative at ); when the decomposition is realized by finite sets, the resulting rational combination cannot produce the required analytic sign/phase (it stays on the “algebraic” positive side). This contradicts the actual value of .

A symmetric argument applies if is finite: then is fixed and must bear the entire analytic burden; again the finite rational identity cannot reproduce the analytic sign at . Therefore, both classes must be infinite.

Interpretation via Classical Pillars.

Pringsheim (nonnegative coefficients ⇒ real singular control): Positivity of coefficients yields rigid real-axis behavior of generating series; finite truncations cannot emulate the required analytic sign at .

Gap/lacunary theorems (Fabry/Hadamard): Attempting to realize the analytic function from a set with “large gaps” (finite or too-sparse) obstructs continuation/phase needed at ; an infinite contribution from both parts is necessary.

Tauberian philosophy (Wiener–Ikehara): Analytic constraints (here, the discriminant identity at a real point) force “density/infinity-type” conclusions for the underlying index sets. Thus both and must be infinite.

Corollary:

(Intrinsic analytic density)

Under the hypotheses of Theorem A, the intrinsic analytic Sophie density

is well-defined with

. In particular,

cannot be realized by a finite index set on either side.

THEOREM 2: There exists an infinite number of Sophie Germain Primes.

Proof:

I start with the relationship between Perfect numbers and their sums of divisors. Let be a Sophie prime number, then the following applies.

Proof of LEMMA 1:

See the steps to get equation (36) for Sophie Germain primes, .

LEMMA 2:

Let p be a prime that generates a Sophie prime pair,

, then, there exits a unique decomposition of

into a quadratic identity

If then, we can separate the sum into parts for which

and

Now for Sophie primes,

Multiplying (49) by

,

However, by (H3),

can only have one value, hence, we get:

Then,

, in (57),

Note that (57) retains the trigonometric relations for

This is not possible since the sums are all positive quantities. It is clear that the contradiction results in a negative sum for the Sophie primes . The reasons are given by the Theorem 2 below.

Define the Sophie Prime indicator:

where

is the von Mangoldt function:

and

is the Möbius function. This indicator equals 1 exactly when

and

are both prime.

The Quadratic Discriminant Theorem for Sophie Infinitude (Conditional Framework)

Let be the set of all Sophie indices where = 1.

From the cotangent decomposition, define partial sums:

These satisfy (53) the truncated field equation:

Lemma: ( Negativity of the Discriminant)

For every finite , the discriminant = is negative. This follows from the positive and orthogonal contributions of the sine-product kernel in the cotangent expansion. Finite truncations underestimate cross interactions, so and hence .

Conditional Quadratic Discriminant Theorem for Sophie Infinitud

THEOREM 2: Assume the analytic cotangent identity converges as a real equality: , . Then, if for all finite N, the set of Sophie indices must be infinite.

Proof:

Suppose is finite. Then there exists such that , , remain stabilized for . The truncated equation (43) reduces to a fixed quadratic in with , hence no real solutions occur. However, the analytic identity requires a real solution, producing a contradiction. Therefore, the cotangent field can remain real only if the Sophie set is infinite.

Corollary. Either the cotangent field identity fails to hold for real arguments, or the Sophie prime set is infinite.

Remarks.

The theorem provides a conditional consistency proof: finite Sophie sets render the analytic system non-real.

A full unconditional proof would require establishing the cotangent identity and directly from number-theoretic first principles.

This framework connects the σ-perfection field with the primality condition encoded by (59), showing that real analytic balance implies infinite continuation of Sophie primes

-

(a)

Discriminant condition.

For a single-valued analytic function tan(2), both roots of (54) must coincide, giving the constraint (55), i.e.

-

(b)

Finite-set contradiction.

Suppose either or is finite. If is finite, then is bounded and is strictly positive; hence , contradicting the analytic value … .

If is finite is finite, diverges, destroying convergence and violating the finite analytic value of .

Therefore, both subsets must extend infinitely.

-

(c)

Analytic necessity.

The negative finite value of arises from the conditional convergence of the full series. Only infinite, interleaved contributions from both classes can reproduce the correct analytic continuation through the real axis.

Finite truncations cannot yield the required sign reversal because all partial sums are positive.

-

(d)

The analytic identity demands a real balance.

The equality (59) can hold with finite only if

Therefore, both the Sophie-primes and non-Sophie classes are infinite classes.

This is a quadratic equation (63) in

To have a real analytic solution, the discriminant must be non-negative:

If , there is no real number that satisfies this finite equation.

That means the analytic equality cannot hold in real numbers for any finite truncation of the sums.

For a given , finite, the partial sums will include only finitely many terms of which only finitely many Sophie and non-Sophie contributions. If the Sophie set were finite, there would exist some beyond which no new Sophie terms appear:

, stabilize for .Then the quadratic becomes a fixed, finite relation. Because it is shown that for any such finite , the discriminant , this stabilized equation has no real solution i.e., it cannot represent a real-valued field balance.

The cotangent identity (from σ and the product expansion) is real for all its parameters. If this real analytic equality holds in the limit, then truncating the series must approach a real number and it cannot “jump” from complex to real unless something is changing as grows. The only way to recover a real limit from a sequence of non-real finite partials is if the system never stabilizes and this means new terms keep entering forever. That “never stabilizing” is precisely infinitude of Sophie contributions.

If you stop adding Sophie terms (finite ), the balance equation becomes over-constrained and the geometry “folds” into the complex plane (negative discriminant). To stay real, the balance must keep being adjusted, which means more Sophie terms keep entering. In short:

Finite Sophie set ⇒ quadratic has no real solution (complex balance).

Analytic identity is real ⇒ real solution must exist.

Therefore, the only way to reconcile them is for the Sophie set to be infinite.

-

1.

Interpretative remark

Suppose Equation (58) and (62) both represents an analytic continuation and equilibrium between a sparse harmonic lattice (the Sophie indices) and the complementary dense continuum (non-Sophie integers). The finiteness of either subset would destroy the analytic balance and invert the sign of cot(2). Thus, the very existence of a finite negative cotangent value enforces the infinitude of both classes -a remarkable intersection of trigonometric analysis and arithmetic structure.

-

2.

-

Remarks and positioning

Theorem 1 is not a re-statement of any single classical result; it’s a fusion: positivity + analytic identity + discriminant collapse ⇒ infinitude of each class. The closest analogues are

Pringsheim (positivity constraints). The term "Pringsheim (positivity constraints)" refers to the Vivanti–Pringsheim theorem in complex analysis. The theorem states that a power series with non-negative real coefficients must have a singularity at a specific point on its circle of convergence. See [

6].

Fabry/Hadamard (sparsity ↔ analytic behavior): The Fabry and Hadamard theorems, particularly the gap theorems, are central results in complex analysis concerning the analytic continuation of power series with "lacunary" or gapped coefficients. Both theorems establish conditions under which a power series cannot be analytically extended beyond its circle of convergence, which then becomes a "natural boundary" for the function [

7].

Tauberian methods (analytic facts ⇒ density/infinitude): Tauberian methods use analytic properties of a function to deduce properties of its underlying sequence of coefficients. In analytic number theory, this approach often uses a Dirichlet series and facts about its analytic continuation to determine the density or infinitude of an arithmetic sequence.

b. The normalization that produces a quadratic in encapsulates the single-valuedness of the trigonometric function at ; the vanishing discriminant is precisely the statement that the two algebraic branches coincide with the analytic branch. For finite partitions, that coincidence cannot match the true sign/phase unless both classes are infinite.

Robustness. The argument isn’t tied to ; any with yields the same conclusion under (H1), (H2) and (H3).

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable”

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable”

Acknowledgements

I would like to pay respects to all the great mathematicians who worked on this problem. YTo them is owed a lot of gratitude for inspiration.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- On the Density of the Abundant Numbers, Paul Erdös, Journal of the London Mathematical Society: Volume s1-9, Issue 4, Pages: 241-320, October 1934.

- Leonhard Euler; “Institutiones calculi differentialis cum eius usu in analysi finitorum ac doctrina serierum, volume 1”.

- C.F. Gauss; “Theoria residuorum biquadraticorum, Commentatio secunda;” Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wis-senschaften zu Göttingen, 1863, 95 - 148.

- Gradshteyn, I.S.; Ryzhik, I.M. Table of Integrals, Series, and Products, 7th ed.; Zwillinger, D., Jeffrey, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007.

- Michael M. Anthony; Consequences of Invariant Functions for the Riemann hypothesis; SCIRP; Document ID: 5302512-20241007-102003-9957. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Thomas Muller. Study of combinatorial objects in higher dimensions. Discrete Mathematics [cs.DM]. Université de Bordeaux, 2025. English. ffNNT : 2025BORD0087ff. fftel-05263156f.

- Patrice Lass`ere and Nguyen Thanh Van; Hadamard Gap Theorem and Over convergence for Faber-Erokhin Expansions;Institut de Math´ematiques, Universit´e Paul Sabatier,118 Route de Narbonne, 31062 Toulouse Cedex 9, France.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).