5. The General Relation That Captures the Behavior of Abondant Numbers, Perfect Numbers and Deficient Numbers

Definition 1. An Abundant number is a positive integer for which the sum of its proper divisors excluding itself is greater than the number itself.

Definition 2. A Perfect number is a number for which the sums of all divisors is equal to twice the number.

Definition 3. A Deficient number is a number for which the sums of all divisors is less than twice the number.

is a Perfect number, then,

Proof. for a Perfect number,

The distribution of

perfect numbers, abondant numbers and

deficient numbers is captured by the general relation:

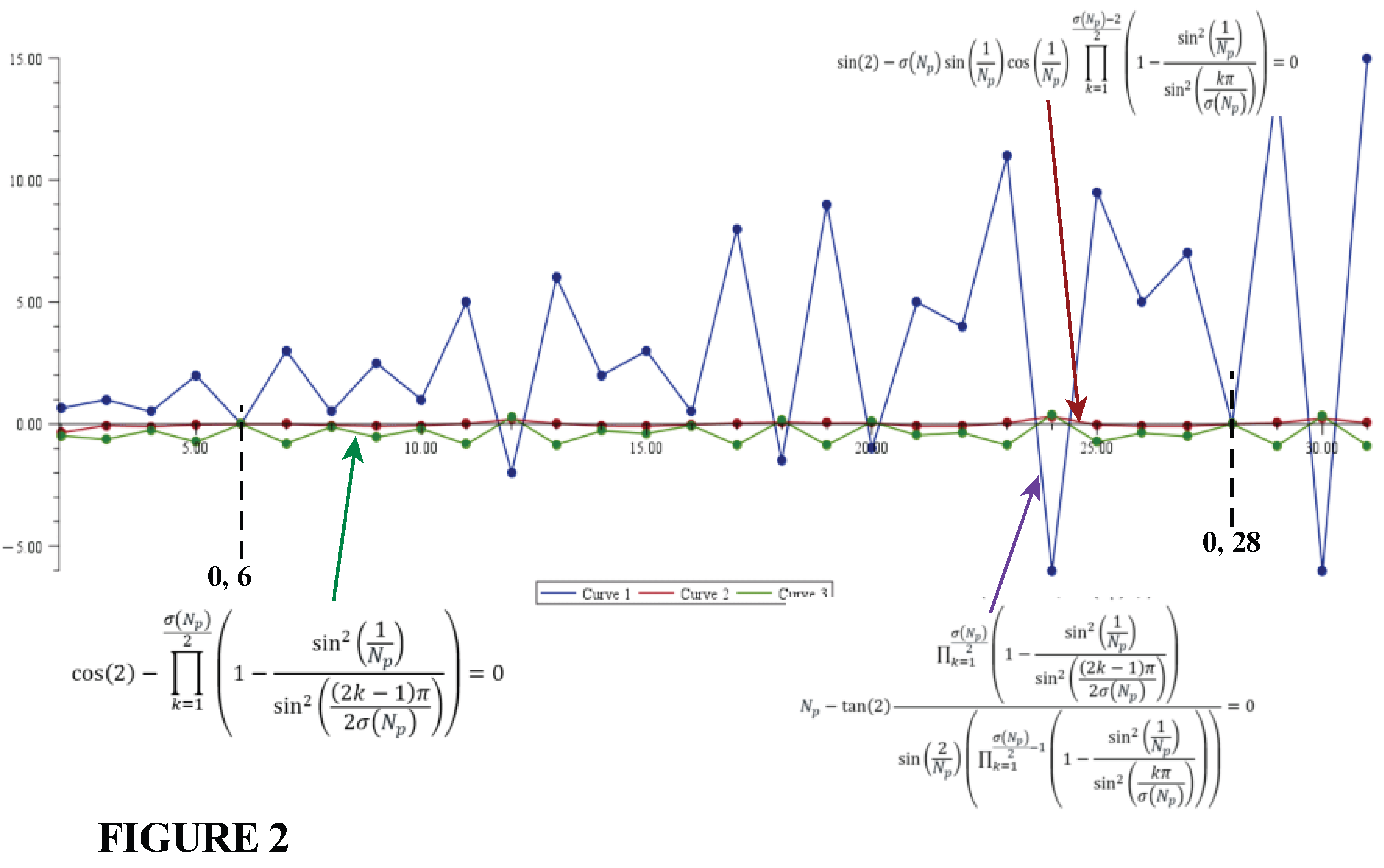

For perfect numbers, and the relation (33) vanishes.

For

abondant numbers,

and the relation does not vanish but generates negetaive imaginary values for

For

deficient numbers,

and the relation does not vanish but generates positive imaginary values for

To see this, put the relation (33) in the form:

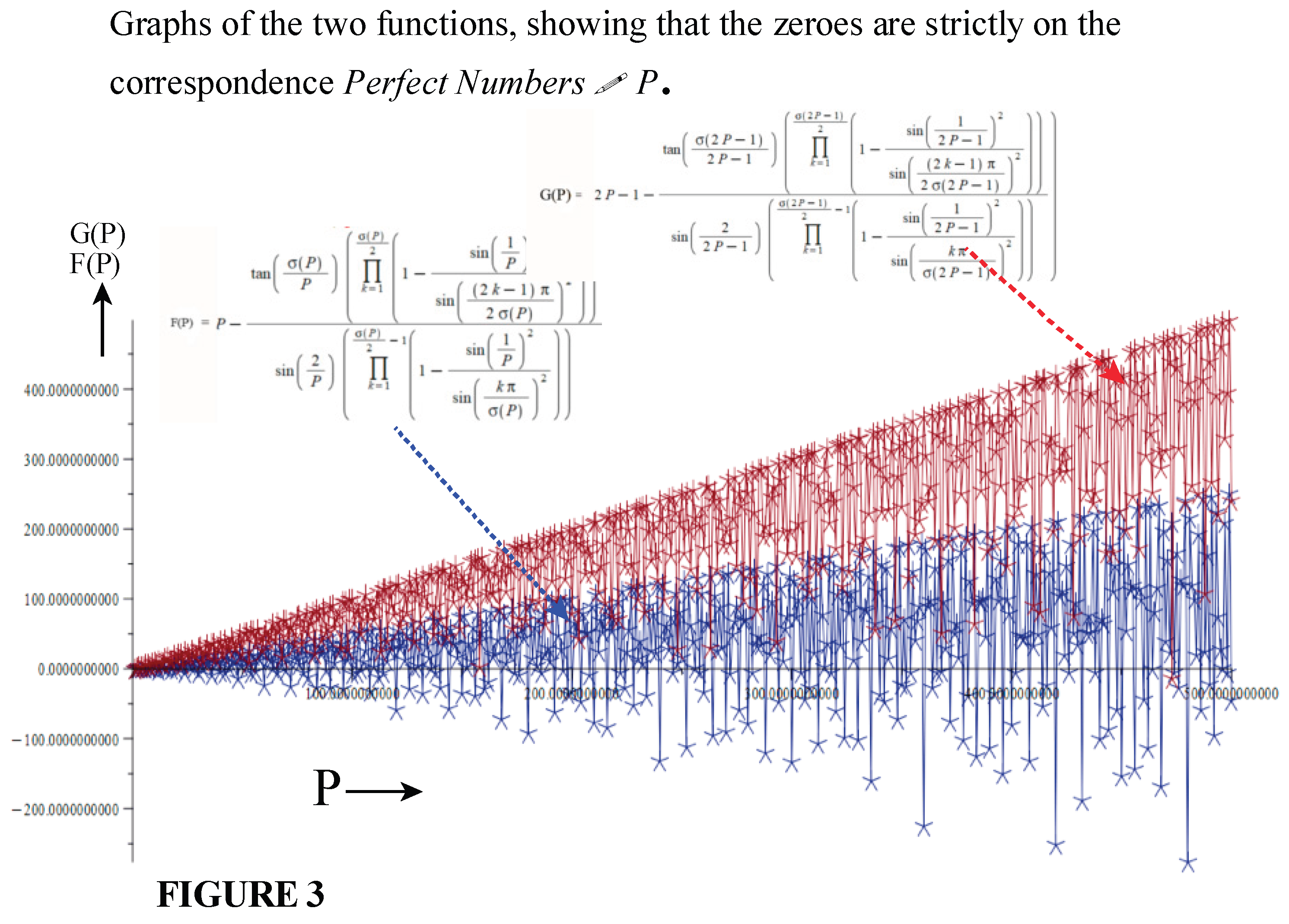

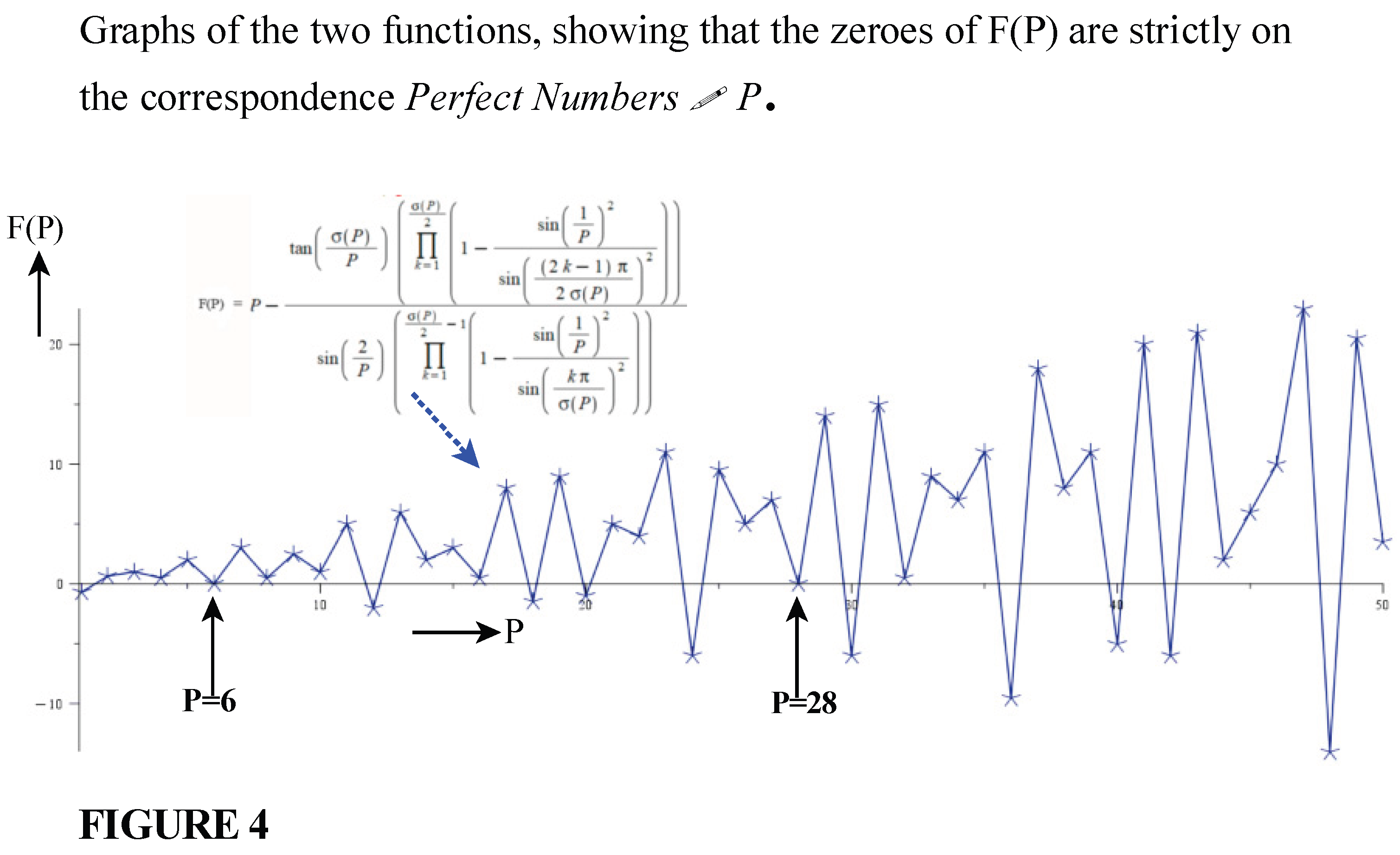

Obviously, the

zeros of the function (34) occur at the Perfect numbers. However, for clarity

we convert this relation to the exponential form:

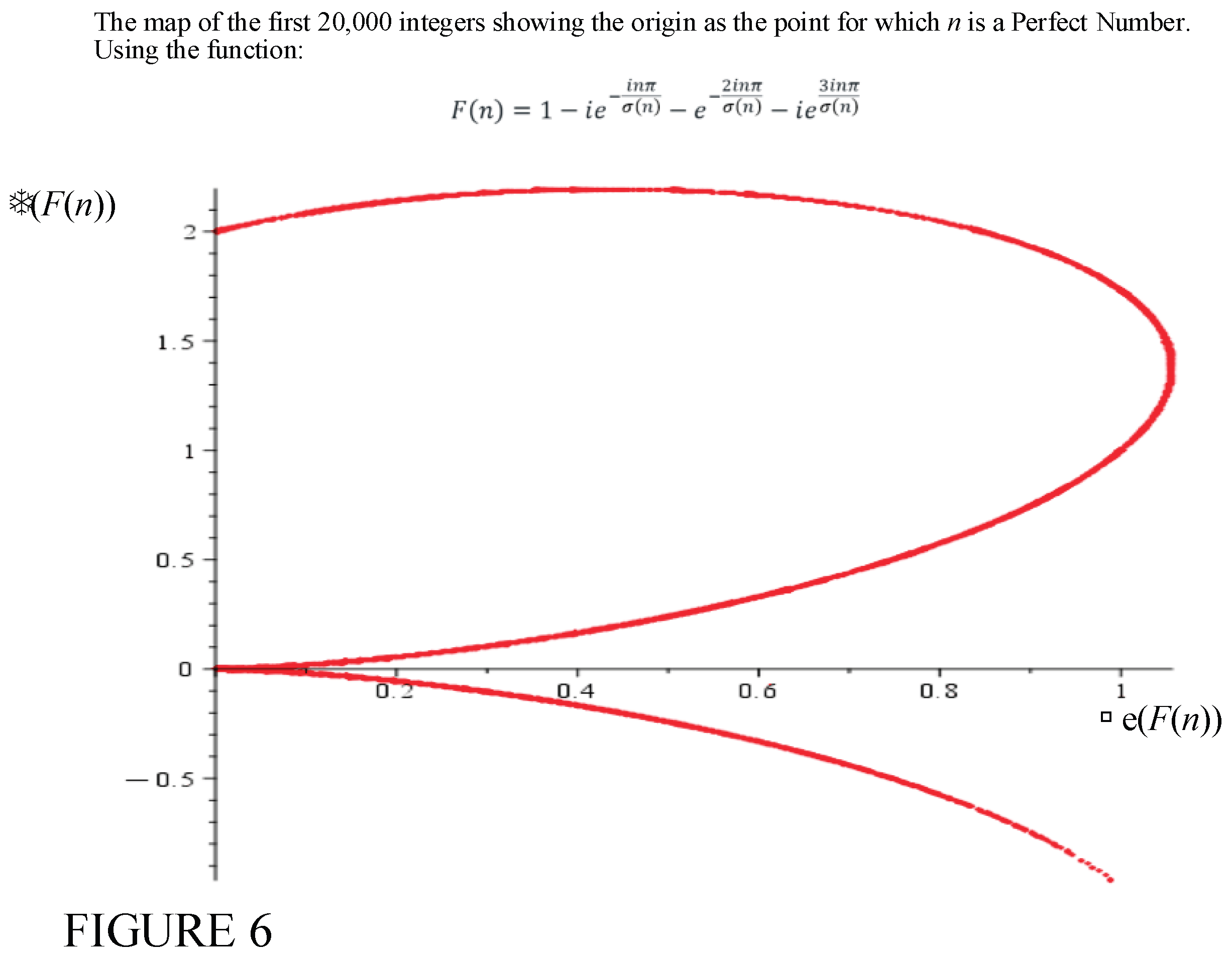

Figure 6 shows the complex map of the function

over the range

.

The zeros of the function occur at the values 6, 28, 496, 8124….

NOTE*: The Mersenne primes and the perfect numbers can only exist on the upper right quadrant corrsponding to deficient numbers. Perfect numbers are the zeros of the function .

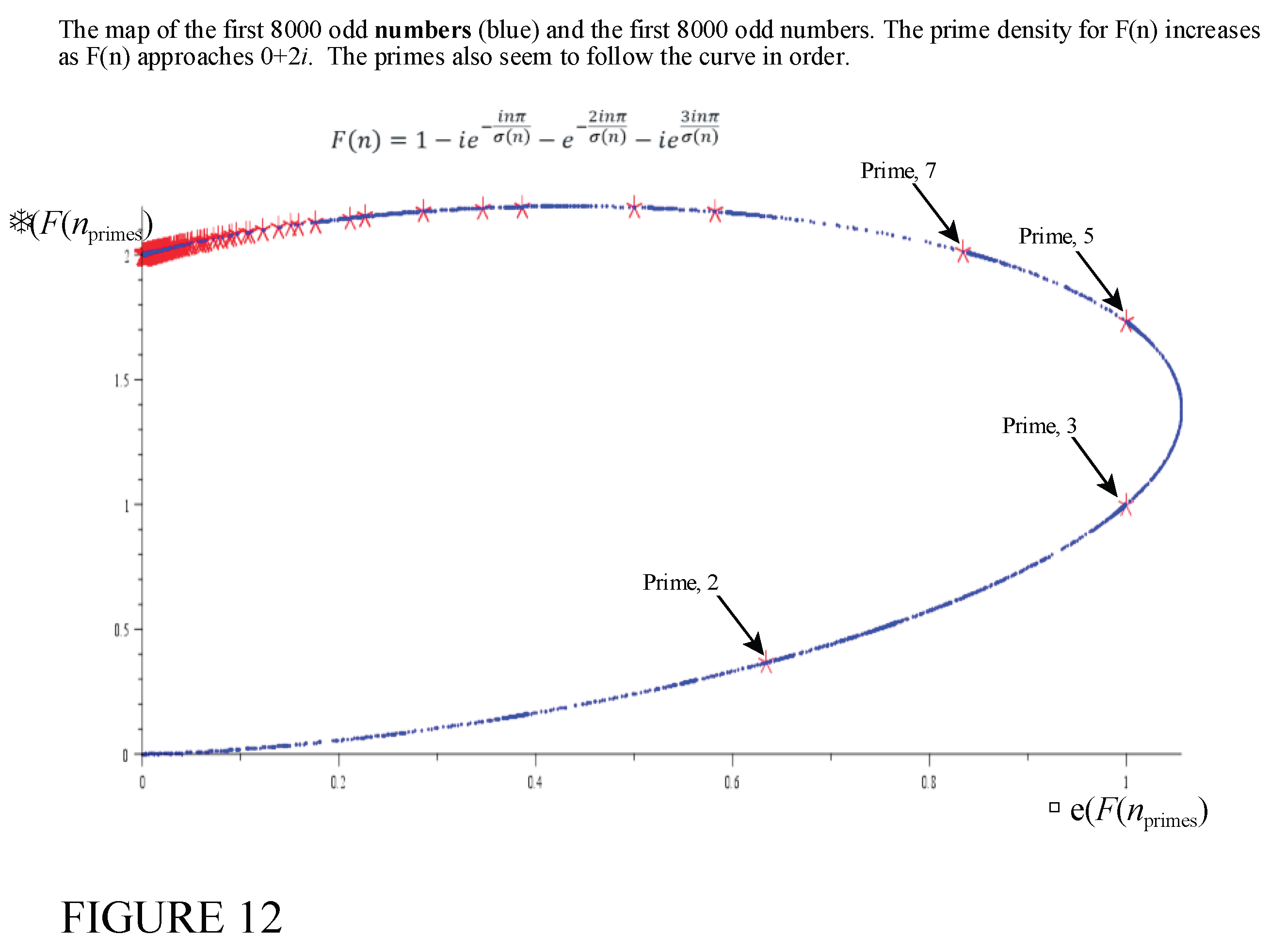

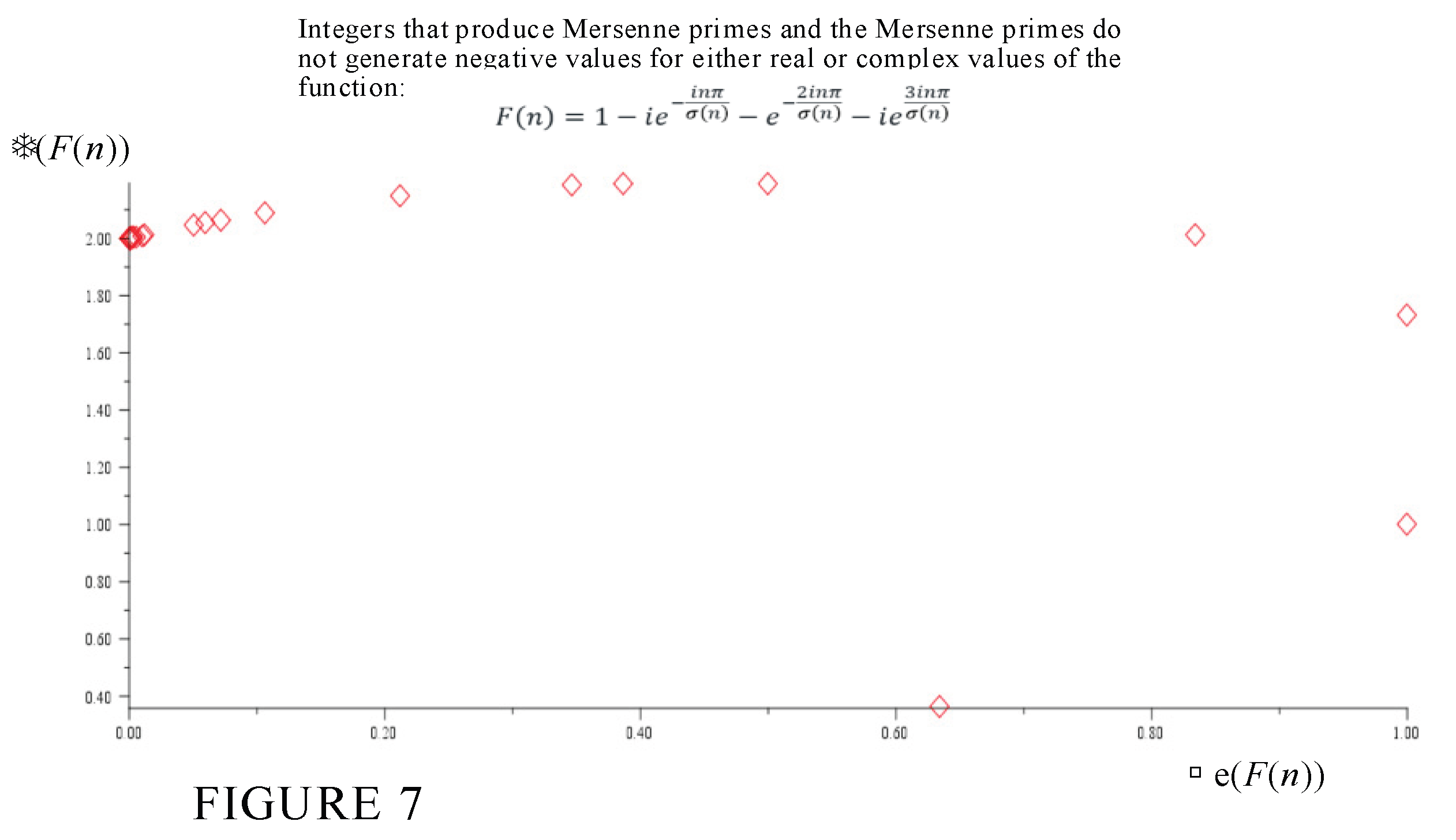

The general locations of primes and Mersenne primes are shown in

Figure 7. As can be seen, the oprimes do not generate negative imaginary values, and are located on the top-right quadrant of the complex plane.

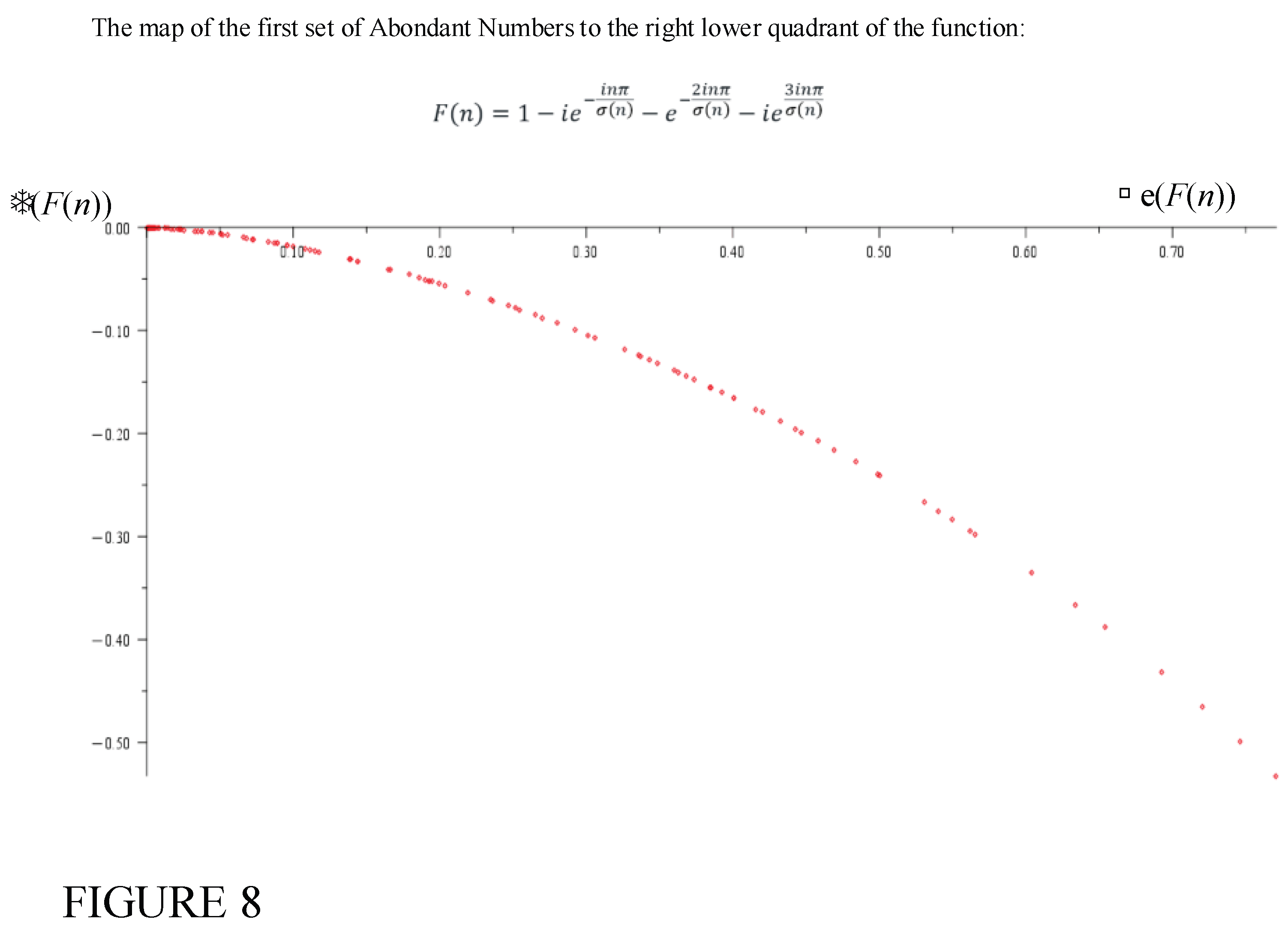

Hence, It is clear that the sequence of abundant numbers,

[12, 18, 20, 24, 30, 36, 40, 42, 48, 54, 56, 60, 66, 70, 72, 78, 80, 84, 88, 90, 96, 100, 102, 104, 108, 112, 114, 120, 126, 132, 138, 140, 144, 150, 156, 160, 162, 168, 174, 176, 180, 186, 192, 196, 198, 200, 204, 208, 210, 216, 220, 222, 224, 228, 234, 240, 246, 252, 258, 260, 264, 270, 272, 276, 280, 282, 288, 294, 300, 304, 306, 308, 312, 318, 320, 324, 330, 336, 340, 342, 348, 350, 352, 354, 360, 364, 366, 368, 372, 378, 380, 384, 390, 392, 396, 400, 402, 408, 414, 416, 420, 426, 432, 438, 440, 444, 448, 450, 456, 460, 462, 464, 468, 474, 476, 480, 486, 490, 492, 498, 500],

produce values of in (35) that lie on the lower right quadrant of the complex plane. This distinct observation for the first 500, abondant numbers provides a clue as to their distribution.

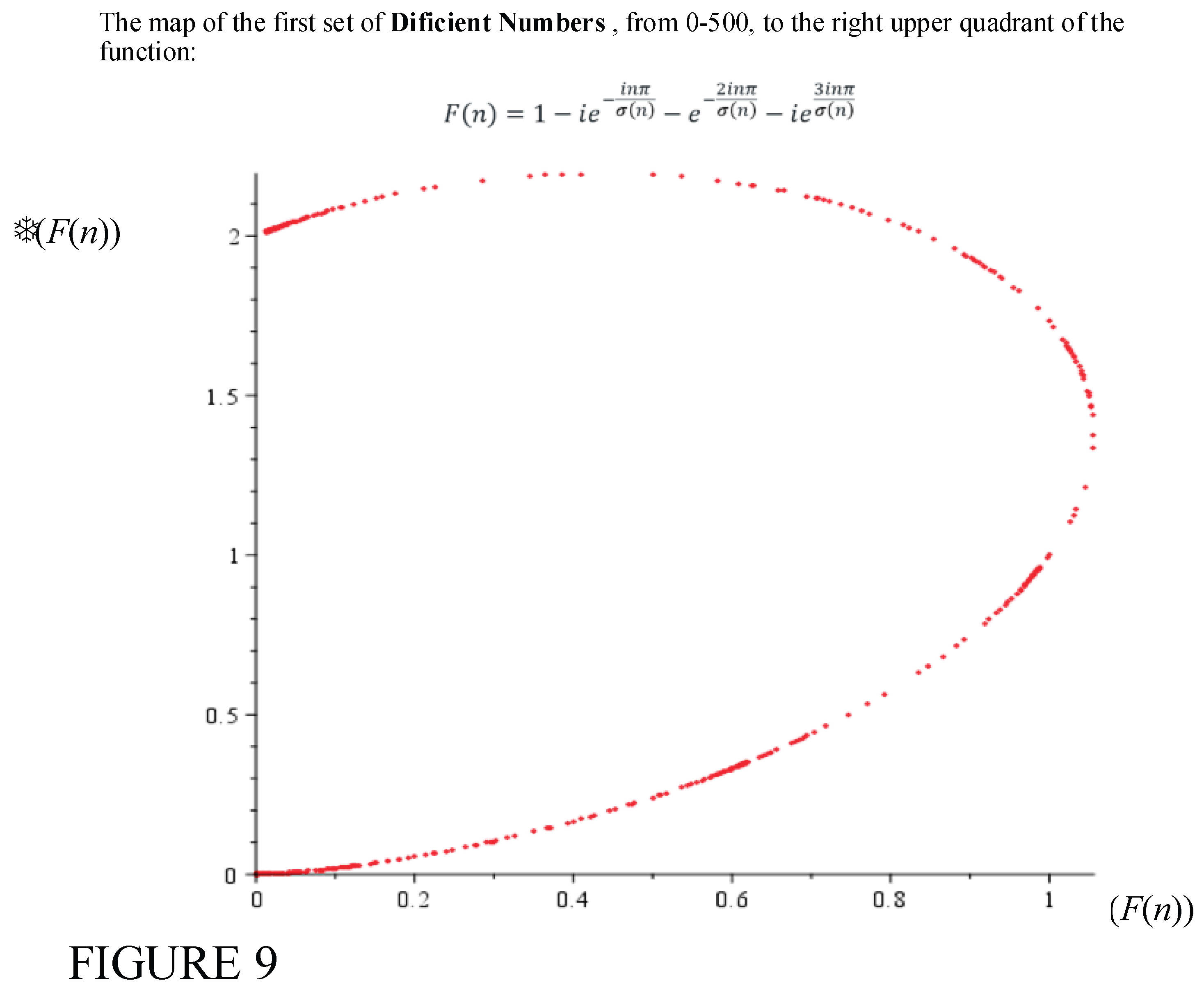

It is clear the first numbers between 0 and 500 that generate a sequence of deficient numbers:

[2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 41, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 55, 57, 58, 59, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 67, 68, 69, 71, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 79, 81, 82, 83, 85, 86, 87, 89, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 97, 98, 99, 101, 103, 105, 106, 107, 109, 110, 111, 113, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 139, 141, 142, 143, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 157, 158, 159, 161, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 175, 177, 178, 179, 181, 182, 183, 184, 185, 187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 193, 194, 195, 197, 199, 201, 202, 203, 205, 206, 207, 209, 211, 212, 213, 214, 215, 217, 218, 219, 221, 223, 225, 226, 227, 229, 230, 231, 232, 233, 235, 236, 237, 238, 239, 241, 242, 243, 244, 245, 247, 248, 249, 250, 251, 253, 254, 255, 256, 257, 259, 261, 262, 263, 265, 266, 267, 268, 269, 271, 273, 274, 275, 277, 278, 279, 281, 283, 284, 285, 286, 287, 289, 290, 291, 292, 293, 295, 296, 297, 298, 299, 301, 302, 303, 305, 307, 309, 310, 311, 313, 314, 315, 316, 317, 319, 321, 322, 323, 325, 326, 327, 328, 329, 331, 332, 333, 334, 335, 337, 338, 339, 341, 343, 344, 345, 346, 347, 349, 351, 353, 355, 356, 357, 358, 359, 361, 362, 363, 365, 367, 369, 370, 371, 373, 374, 375, 376, 377, 379, 381, 382, 383, 385, 386, 387, 388, 389, 391, 393, 394, 395, 397, 398, 399, 401, 403, 404, 405, 406, 407, 409, 410, 411, 412, 413, 415, 417, 418, 419, 421, 422, 423, 424, 425, 427, 428, 429, 430, 431, 433, 434, 435, 436, 437, 439, 441, 442, 443, 445, 446, 447, 449, 451, 452, 453, 454, 455, 457, 458, 459, 461, 463, 465, 466, 467, 469, 470, 471, 472, 473, 475, 477, 478, 479, 481, 482, 483, 484, 485, 487, 488, 489, 491, 493, 494, 495, 497, 499 ],

produce values of that lie on the upper right quadrant of the complex plane. This distinct observation for the first 500, defficient numbers and abondant numbers provides a clue as to their distributions.

Between the

abondant numbers and the deficient numbers, are the P

erfect Numbers, [6, 7, 28, 496, 8128, 33550336,….], that generate the zeros of the function:

Hence, the imaginary part of the function

determines if a number is an

abondant number, a

perfect number or a

deficient number.

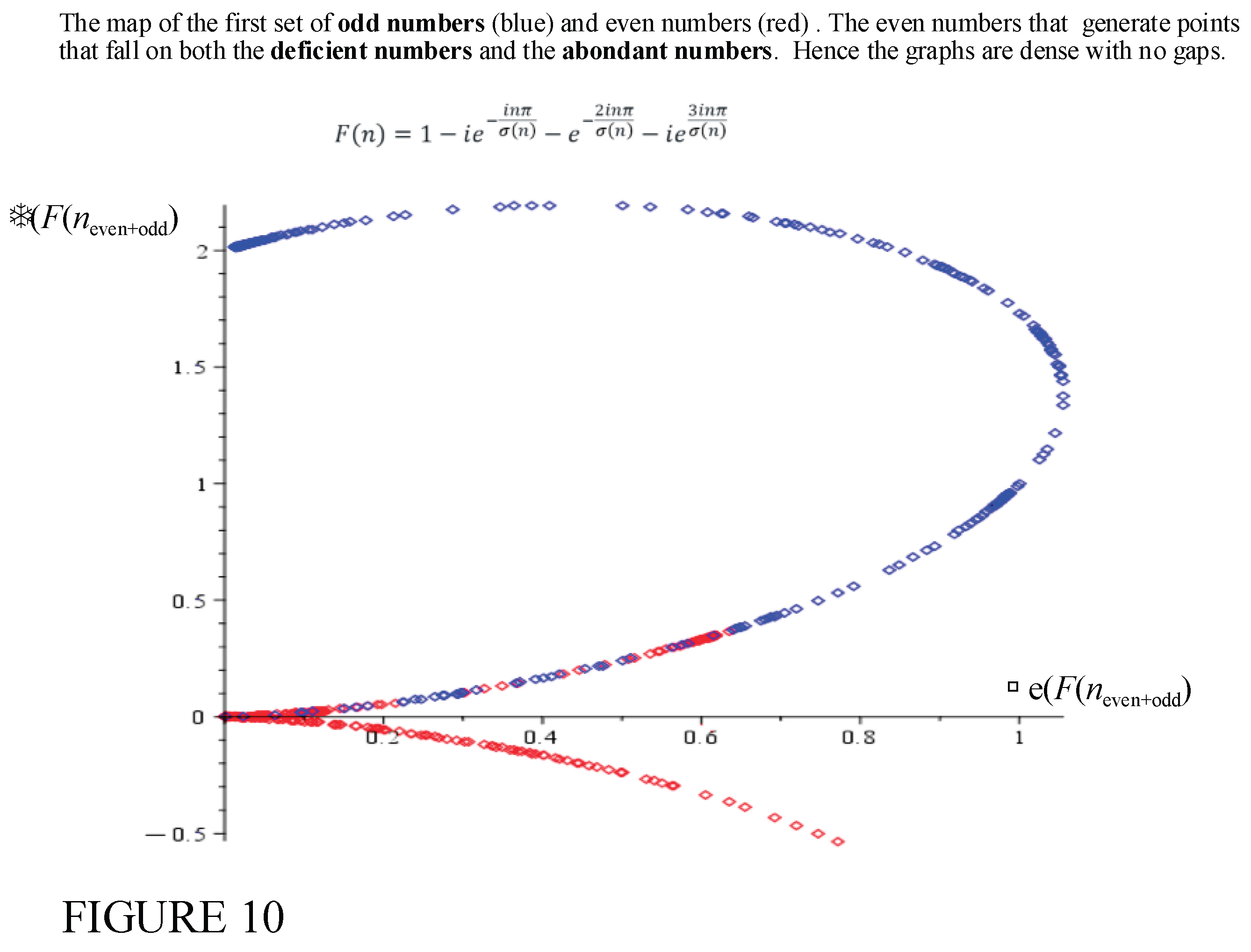

The first set of even numbers from 0..500 that lie on the defient number curve but are not abondant numbers are:

[2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 14, 16, 22, 26, 28, 32, 34, 38, 44, 46, 50, 52, 58, 62, 64, 68, 72, 74, 76, 82, 86, 92, 94, 98, 106, 110, 116, 118, 122, 124, 128, 130, 134, 136, 142, 146, 148, 152, 154, 158, 164, 166, 170, 172, 178, 182, 184, 188, 190, 194, 202, 206, 212, 214, 218, 226, 230, 232, 236, 238, 242, 244, 248, 250, 254, 256, 262, 266, 268, 274, 278, 284, 286, 290, 292, 296, 298, 302, 304, 310, 314, 316, 322, 326, 328, 332, 334, 338, 344, 346, 356, 358, 362, 370, 374, 376, 382, 386, 388, 394, 398, 404, 406, 410, 412, 418, 422, 424, 428, 430, 434, 436, 442, 446, 452, 454, 458, 466, 470, 472, 478, 482, 484, 488, 494, 496].

These numbers are clearly defined by (37).

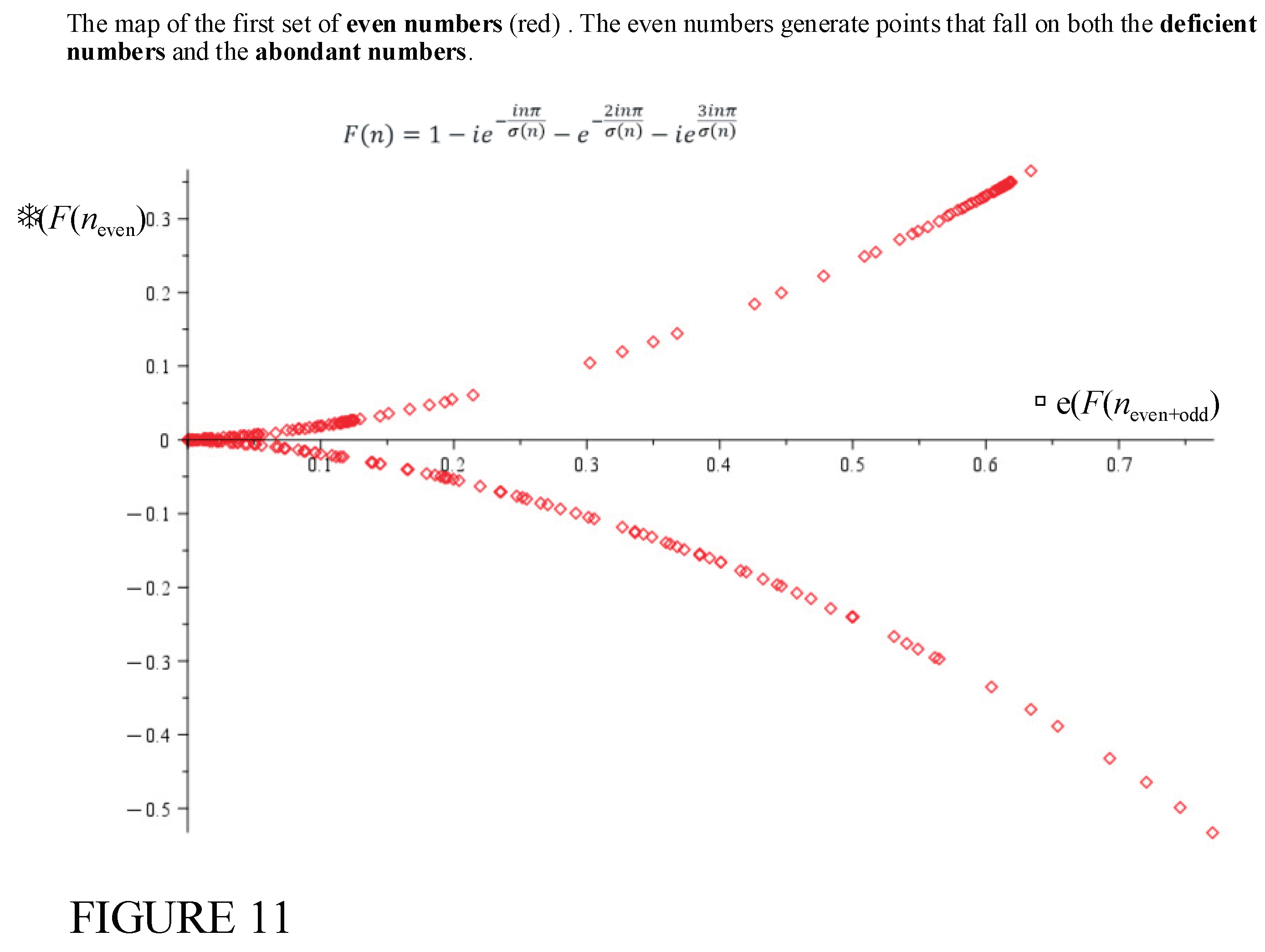

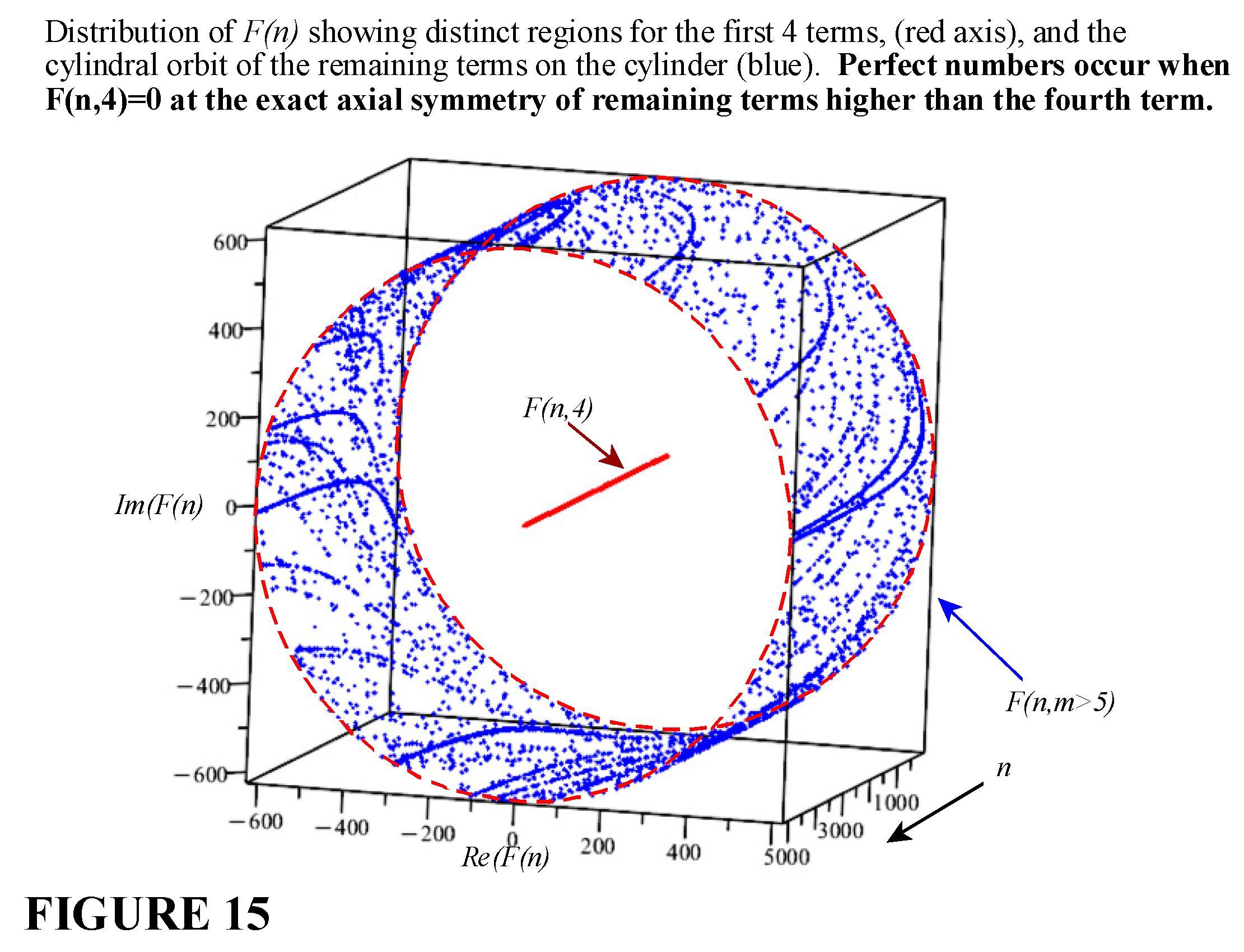

Figure 10 shows the 2D plot of the function covering both odd and even numbers in the range

0.

It is clear that the even numbers (red points) can fall on both the deficient number curve and the abondant number curve. The deficient numbers seem to be bounded by the line and a maximum imaginary value of .

Definition 4: An

Deficient disturbing number , (

DDN), is a

deficient number which:

These are the red points on

Figure 10 that intermingle with the blue odd number points.

[2,4,8,10,14,16,22,26,32,34,38,44,46,50,52,58,62,64,68,74,76,82,86,92,94,98,106,110,116,118,122,124,128,130,134,136,142,146,148,152,154,158,164,166,170,172,178,182,184,188,190,194,202,206,212,214,218,226,230,232,236,238,242,244,248,250,254,256,262,266,268,274,278,284,286,290,292,296,298,302,310,314,316,322,326,328,332,334,338,344,346,356,358,362,370,374,376,382,386,388,394,398,404,406,410,412,418,422,424,428,430,434,436,442,446,452,454,458,466,470,472,478,482,484,488,494…..].

The extent to which the even numbers infiltrate the deficient number space for up to

seems to be confined to the approximate range,

The extent to which the even numbers penetrate the abondant number space is unknown. However it is known that there exists in infinite number of abundant numbers. It has been shown that every multiple is either an abondant number, or taking more multiples of 6 of such numbers leads to an bondant number. Since there is an infinite number of multiples of 6, then there are an infinite number of abondant numbers.

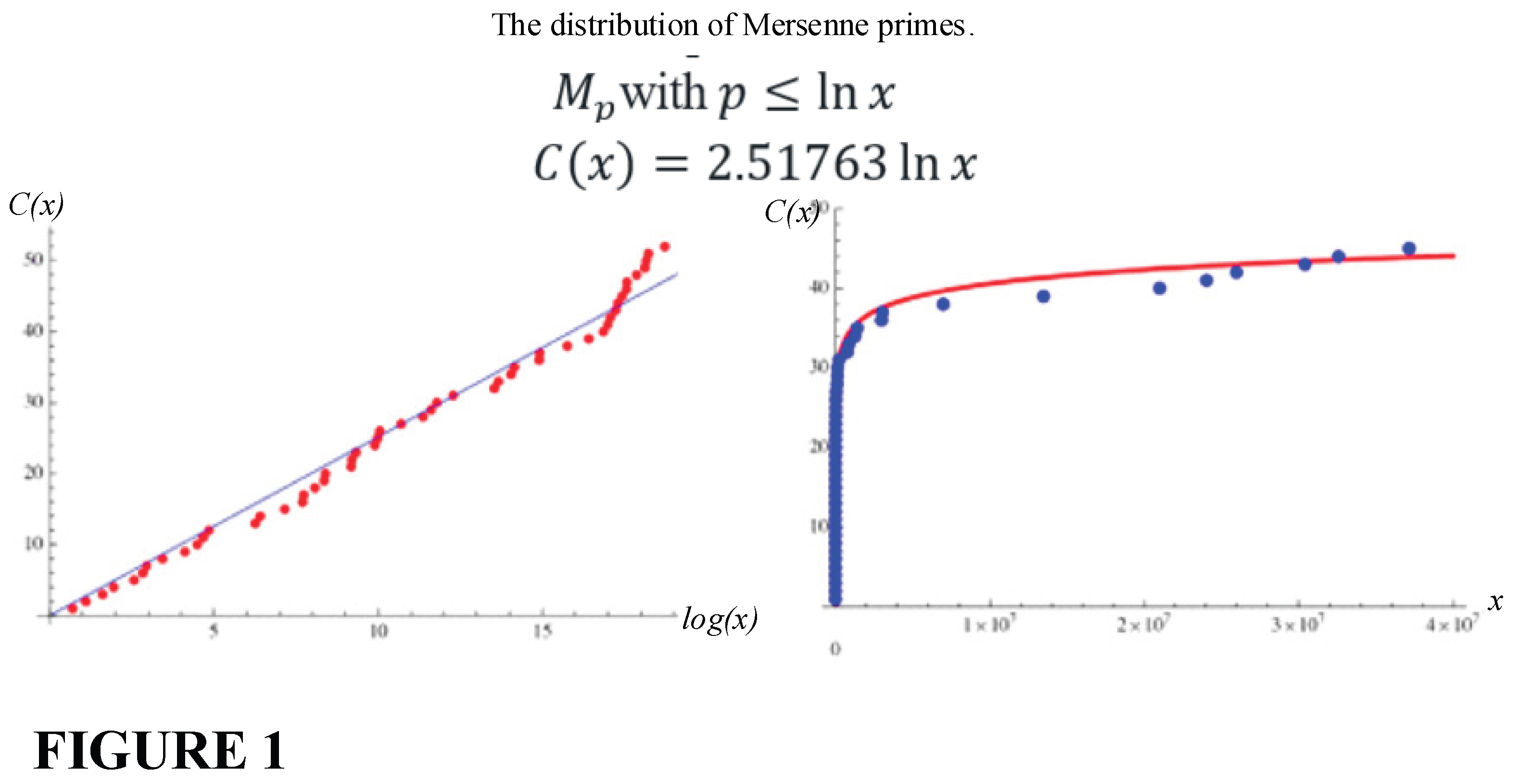

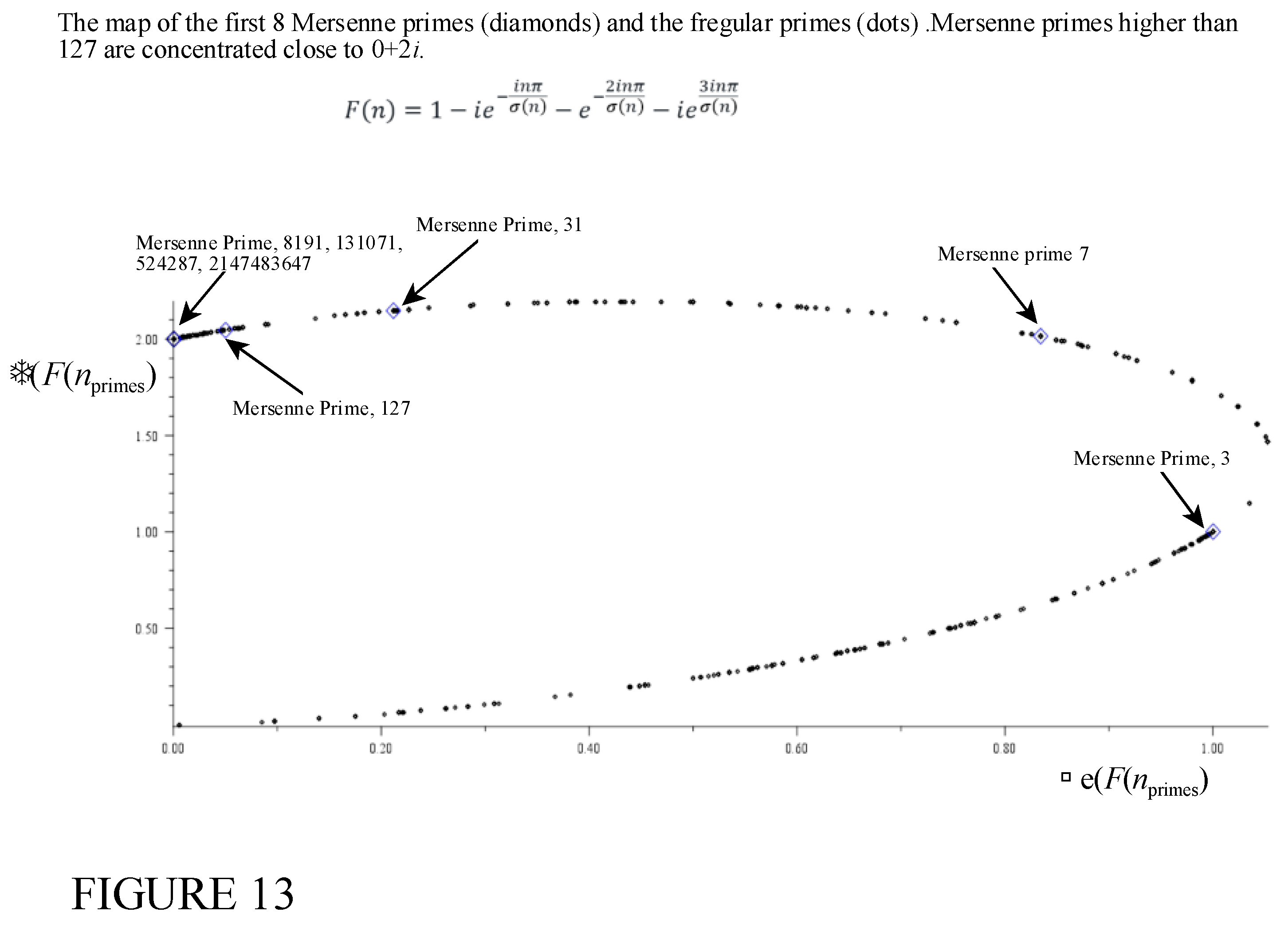

Figure 13 shows the distribution of the Mersenne primes with the regular primes.