∙ Borax has high chemical potential to extend setting time of

geopolymer, but affects strength development.

∙ A combination of borax and starch is effective in enhancing

setting time without affecting the strength.

∙ The optimum combination developed is effective at higher slag to

fly ash ratio.

∙ The geopolymerisation reaction is hindered by high dosage of

borax in fly ash based geopolymer.

∙ The physio-chemical action of starch and borax geopolymer delays

setting time.

1. Introduction

Geopolymers are one among the alternative green materials being explored globally, aligning with the concept of sustainable and green environmental practices. Geopolymers cementitious products derived from aluminosilicate minerals, through their reaction in an aqueous alkaline medium, forming an amorphous three-dimensional polymer structure [

1,

2,

3]. Despite its superior mechanical and durability properties, challenges remain in controlling their setting characteristics. The setting time of geopolymer depends on the aluminosilicate source materials involved in their synthesis. Fly ash (FA)-based geopolymers generally exhibit setting characteristics comparable to that of ordinary Portland cement; but they often require elevated temperature curing, which causes challenges for practical applications. In high calcium FA systems, the presence of calcium oxides leads to high pH value of the geopolymer results in rapid setting and the readily available calcium ions forms calcium silicate hydrate (CSH) gels through reaction with silicates [

4,

5]. The CSH gel precipitates rapidly at the early stage of reaction and some of the calcium hydroxide remains intact due to the reduction of solubility and common ion effect [

6]. Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBFS) is an aluminosilicate mineral rich in calcium oxides which is often blended with low calcium FA geopolymer, to accelerate the geo-polymerization and hydration reactions, resulting in superior mechanical properties. The calcium oxide in GGBFS is known to accelerate geo-polymerization due to the formation of calcium aluminon silicate hydrate (CASH) and hybrid CASH/ sodium aluminon silicate hydrate (NASH) gel phases [

7]. The increased GGBFS content if fly ash geopolymer results in reduced setting time due to early precipitation of the calcium rich gel phases that act as the nucleation sites, for enhanced geo-polymerization due to greater dissolution of aluminosilicates. However, this accelerated reaction comes at the cost of a significantly reduced setting time, which becomes a major drawback [

8]. Additionally, the rapid setting leads to poor workability of the mixture, which hampers its practical application [

6]. Retarders are added to slow down this reaction, allowing more time for mixing, transport, or placement. They significantly extend the initial and final setting times, which is critical in hot climates or when using highly reactive precursors like slag or metakaolin [

9,

10].

Commonly used retarders in cement composites include lignosulfonates, hydroxylated carboxylic acids, polyhydric alcohols and different sugar-based compounds. However, geopolymer chemistry is different from that of ordinary Portland cement, rendering the ineffectiveness of cement retarders. Efforts to enhance the setting time of geopolymer have led to the exploration of various additives. Different additives like calcium chloride, calcium sulphate, sodium sulphate and sucrose have minimal impact on the compressive strength, and calcium based additives accelerates the setting of geopolymer [

5]. Due to the high mobility of chlorine ions in calcium chloride, early formed gel tends to be more open and porous, resulting in more gel formation. Unlike calcium sulphate, sodium sulphate significantly delayed the initial setting time, due to the formation of ettringite around FA particles, preventing leaching of alumina and silica. Addition of sugars like glucose, fructose, lactose, and sucrose improves both the initial and final setting time of geopolymer [

11]. Attempts to reduce the pH of the mix through acid addition, aimed to extend the setting time, has proven ineffective and even detrimental [

12,

13].

Borax, a well-known additive in geopolymers, improved the initial and final setting times of fly ash–slag geopolymers by approximately 2.25 and 1.25 times, respectively, with a 10% addition [

14]. The addition of borax reduces the affinity of aluminosilicates in the precursor and the silicates in the activator, thereby delaying the setting and enhancing workability. Antoni et al. [

15] observed that the addition of borax delays setting of fly ash geopolymer, although the improvement is marginal even at a dosage of 7%. In a subsequent study, Antoni et al. [

16] found that high dosage of borax (20% by weight of binder) could improve setting time by 75-90 min, compared to the flash setting of control mix. However, this was accompanied by a 30% reduction in compressive strength. Various other retarders have also been explored in literature, including sodium lignosulfonate, borax, citric acid, sucrose, sodium gluconate, sodium pyrophosphate, sodium hexametaphosphate, sodium tripolyphosphate, calcium sulphate, anhydrous sodium sulphate, anhydrous calcium chloride, barium chloride and boric acid [

17,

18]. While some of the retarders have negative effect and some have marginal effect in improving the setting characteristics, borax emerged as the most effective with a dosage of 8% improving the initial and final setting time by 307.5% and 268% respectively [

18]. It should be worth noted that use of borax is effective only at high dosages [

14,

16].

The addition of cellulose and starch as retarders in geopolymer is a novel concept. Ferreira et al. [

19] employed microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) as an additive in geopolymer and found improvement in the mechanical properties. It was reported that the addition of MCC has resulted in accelerated setting of geopolymer in 36 min (15% faster), and delayed setting time of cement pastes in 97 min (40% slower). Hoyos et al. [

20] reported the delay in hydration reaction in cement based composites by the addition of MCC, due to the formation of a waterproofing barrier on the anhydrous particles of cement. On the other hand, cellulose addition results in reduction in setting time of geopolymer, possibly due to the heat generated during cellulose degradation causing enhanced polymerization reaction [

21].

Investigating the effect of a retarder on the set time and curing of geopolymers is crucial for both scientific understanding and practical application. First, geopolymers often have rapid setting behavior, which can be challenging in large-scale or complex construction projects. By studying retarders, researchers can better control the set time, allowing more time for placement, finishing, and adjustments on-site. In addition, the rate of setting and curing can directly impact the development of mechanical strength and durability. A well-tailored setting profile can improve long-term performance and resilience of the geopolymer. Thus, the present study deals with the evaluation of the setting characteristics of different retarders including cellulose, starch, borax and their combinations. The effects of the retarders on workability and mechanical performance are also analyzed. The effect temperature curing on the mechanical properties of geopolymer with the retarder additives are also evaluated.

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Materials

The geopolymer binder materials used in the study were FA and GGBFS, procured from Tuticorin coal-fired thermal power plant and JSW Cements, in India. Low calcium FA with higher silica content conforming to class F as per IS 3812-1 [

22], was used. The physical properties and chemical composition of FA and GGBFS are given in

Table 1. The fine aggregate used in the study was graded sand with a maximum particle size of 4.75 mm. A combination of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and sodium silicate (Na

2SiO

3) solutions were used as alkali activators for binders. Industrial grade NaOH flakes white in color and having 98% purity were used to prepare the NaOH solution. Industrial grade Na

2SiO

3 solution bluish grey in color with 14.7% Na

2O, 35% SiO

2 and 50.3% H

2O by weight was used in the study. The chemicals used as retarders include carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC), starch and borax in powder form given in Figure

1. CMC and HEC are commercially available cellulose in powder form, both are water-soluble and derived from cellulose, a natural polymer found in trees and plants. Borax is a colorless crystalline water-soluble salt, a hydrated borate of sodium. Starch derived from grain flour was used in the study.

Figure 1.

Retarders; a) CMC b) HEC c) starch d) borax.

Figure 1.

Retarders; a) CMC b) HEC c) starch d) borax.

2.2. Mix Proportion and Sample Preparation

FA and GGBFS were used as the binder in 60:40 proportion, for the evaluation of the effect of retarders. The alkali activators Na

2SiO

3 solution and 10M NaOH solutions were mixed prior (24 h prior to casting) in the ratio 2:1. The retarder solution dosage was 3% weight of binder, and it was prepared by adding 95% water into the retarder powder. Six retarder combinations were selected for the study given in

Table 2. For retarder combinations containing cellulose/starch and additives, the additives are dissolved in water in the ratio 1:1.

Geopolymer paste was prepared to evaluate the standard consistency and setting time. The binder content for the geopolymer paste was 1350 kg/m3. The solution to binder ratio for the setting time measurements was selected based on the standard consistency. Geopolymer mortar samples were prepared to evaluate the compressive strength of the mixes with retarders, with a binder to sand ratio of 1:2. For the preparation of geopolymer mortar, binder content in the mix proportion was selected as 630 kg/m3, and the alkali solution to binder ratio was fixed as 0.5. The setting time of FA-GGBFS geopolymer is dependent on the percentage weight of GGBFS in the mix. As the GGBFS content increases, the setting time is drastically affected with the increased geo-polymerization reaction, due to presence of the calcium oxide. After choosing a suitable retarder, the effectiveness of the combination is tested for different GGBFS content in geopolymer mixes. Two different mixes of geopolymer with the optimum retarder containing FA:GGBFS in the ratio 50:50 and 40:60 are analyzed and compared with 60:40 mix.

2.3. Test for Setting Time, Workability and Compressive Strength

The setting time of the geopolymer was measured using the Vicat apparatus as per [

23]. The Vicat apparatus is a fundamental tool in construction materials testing, used primarily to measure the setting time and consistency of cement-based pastes, including emerging materials like geopolymers. It functions with a vertical rod that holds different types of needles or plungers, depending on the specific test being conducted. This rod is carefully lowered into a standardized mold filled with the test paste, and the depth to which it sinks is measured using a graduated scale. To determine the standard consistency of a paste, a plunger is used. The amount of water in the mix is adjusted until the plunger penetrates the paste to a specific depth—typically 33 to 35 millimeters. This consistency is important because it provides a baseline for further testing. For setting time measurements, different needle configurations are employed. The initial setting time is recorded as the duration from the moment water is added until the needle fails to penetrate to a point 5 mm from the bottom of the mold. To find the final setting time, a needle with an annular attachment is used, and the test ends when the needle marks an impression on the specimen surface and the annular attachment fails to do so.

The flow workability of geopolymer mortar with additives was measured using a mini-slump flow test with modified ASTM C1611 [

24]. A mini slump cone was employed having a bottom diameter, top diameter and height of 1.5 in, 0.75 in and 2.25 in, respectively [

25,

26]. The flow workability of the mortar was expressed in terms of relative slump [

27]. The slump cone is filled in three layers and compacted thoroughly to remove any air voids, and the cone is lifted and the flow diameter of the mortar on a glass plate was measured after 60 s. The flow in percentage was expressed in terms of bottom diameter of the cone [

28], the relative slump (

r0) given in Equation 1.

(1)

Where d is the average of three diameters of mortar flow, and d0 is the bottom diameter of the mini slump cone.

The compressive strength of geopolymer mortar was evaluated according to ASTM C873 [

29]. Cylindrical specimens of 50 mm in diameter and 100 mm height were cast as per the standard, maintaining a height to diameter ratio of 2. The specimens were cast in three layers, and were demolded next day, and ambient cured for 28 days in a temperature of 29±3◦C and relative humidity of 70±10%. After curing period, the specimens were tested in a compression testing machine of capacity 3000 kN, at a displacement-controlled loading rate of 1 mm/min. To study the effect of temperature curing, after demolding some of the specimens were cured in a hot air oven under a temperature of 60

oC for 7 days after demolding and further kept at ambient conditions until 28 days of aging is achieved.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Setting Time

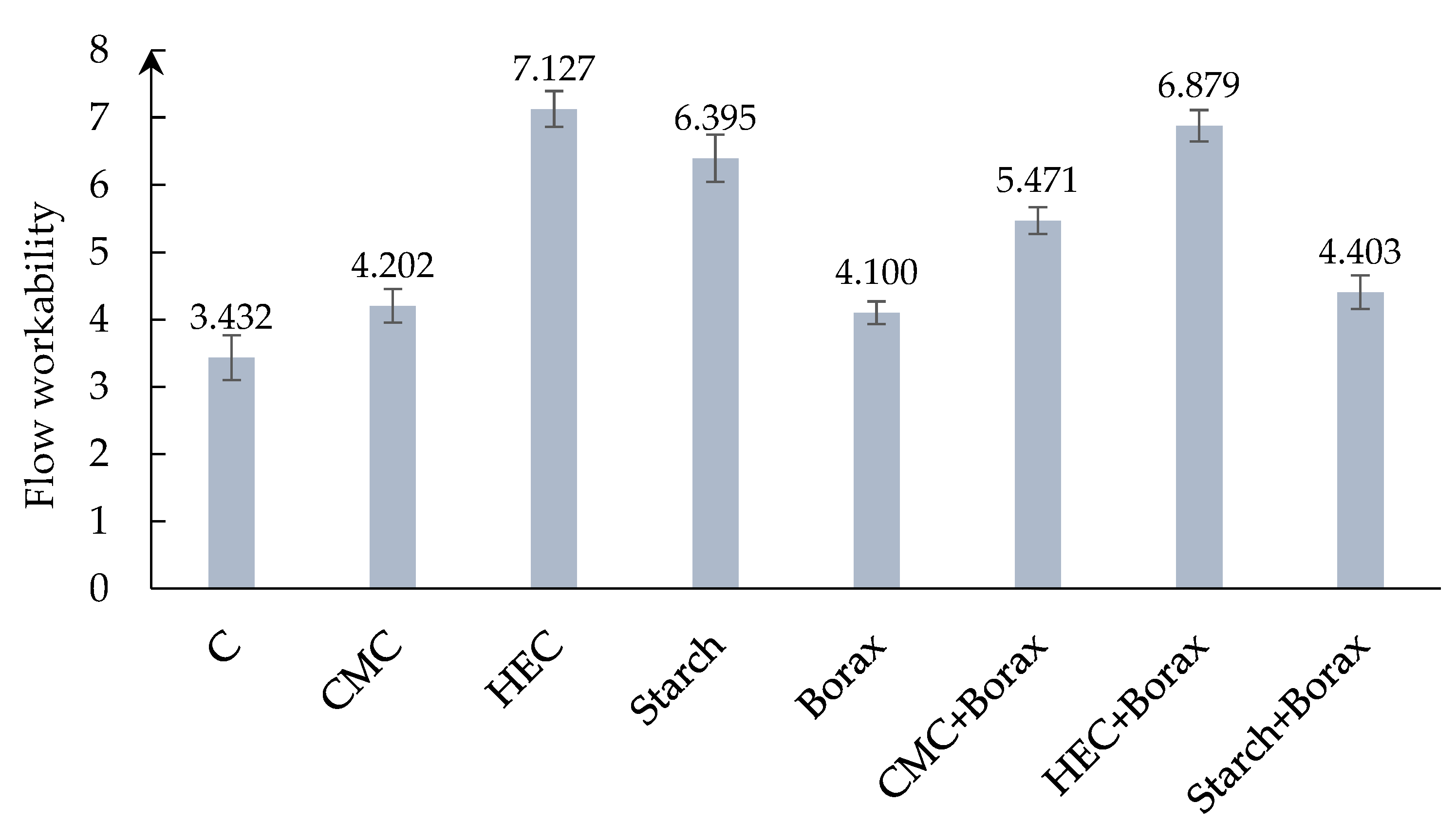

For the measurement of setting time, the alkali solution to binder ratio was fixed as 0.35 based on the standard consistency of binder with the alkali solution, for a FA to GGBFS ratio of 60:40. The results for the setting time characteristics of the mixes are given in

Figure 2. The letter ‘C’ stands for the control mix followed by the mixes with different retarder combinations.

The final setting time of geopolymers is a critical parameter that must be optimized for practical applications. The preferred final setting time should be more than 350 minutes, while the minimum initial setting time is to be at least 60 minutes [

30]. In the present study, a combination of starch and borax was found to be the most suitable retarder combination for geopolymer with FA:GGBFS ratio 60:40, yielding the longest setting time, meeting the mechanical properties. The setting time of geopolymer reduces based on the GGBFS content as the calcium oxides in GGBFS accelerates the geo-polymerization reaction. The combination was also selected based on the compressive strength which is discussed further. Borax is known to complex with alkaline ions (Na

+), thereby reducing the availability of free alkali ions, and thus suppress the dissolution of silicates from aluminosilicate precursors, delaying nucleation and polycondensation [

31,

32]. Additionally, borax can adsorb on particle surfaces, limiting nucleation and growth of gel phase [

33]. Natural polysaccharides such as cellulose and starch forms a diffusion barrier around the unreacted precursors or absorbs free water, affecting the mobility of ions [

34]. Starch, in contrast, a polysaccharide that can absorb water, physically delays gelation by hindering molecular mobility, through creating a viscous medium [

35]. Additionally, both can interact with the activating solution; their hydroxyl groups undergo ring-opening reactions, forming low-molecular weight acids that reduce the pH of the activating solution. The hydroxyl ions will enhance the interconversion of the sugars in the solution, leading to opening the ring of sugar molecules. Thus, cellulose and starch sugars form organic acid in the solution, and the strong alkali degrades it [

11]. Cellulose/starch, with borax shows synergistic effects, combining the chemical (via complexation and acidification) and physical hindrance, making the setting time more controllable.

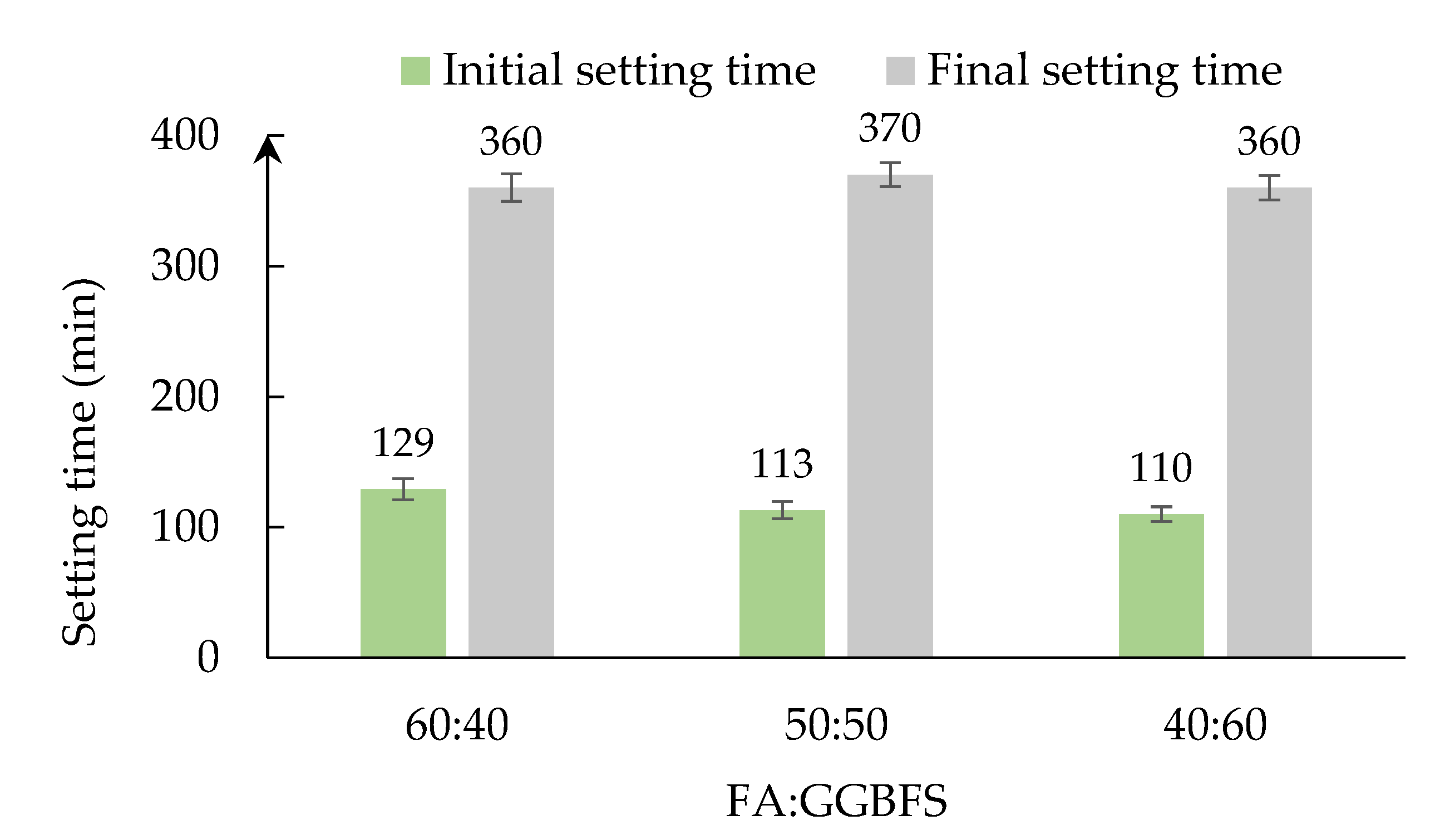

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the starch and borax retarder combination in mixes containing higher GGBFS content, the authors evaluated mixes with FA:GGBFS proportion 50:50 and 40:60. The results for setting time is given in

Figure 3. The initial setting time gradually reduces as the GGBFS content increases but is within limits. However, the final setting time is not affected.

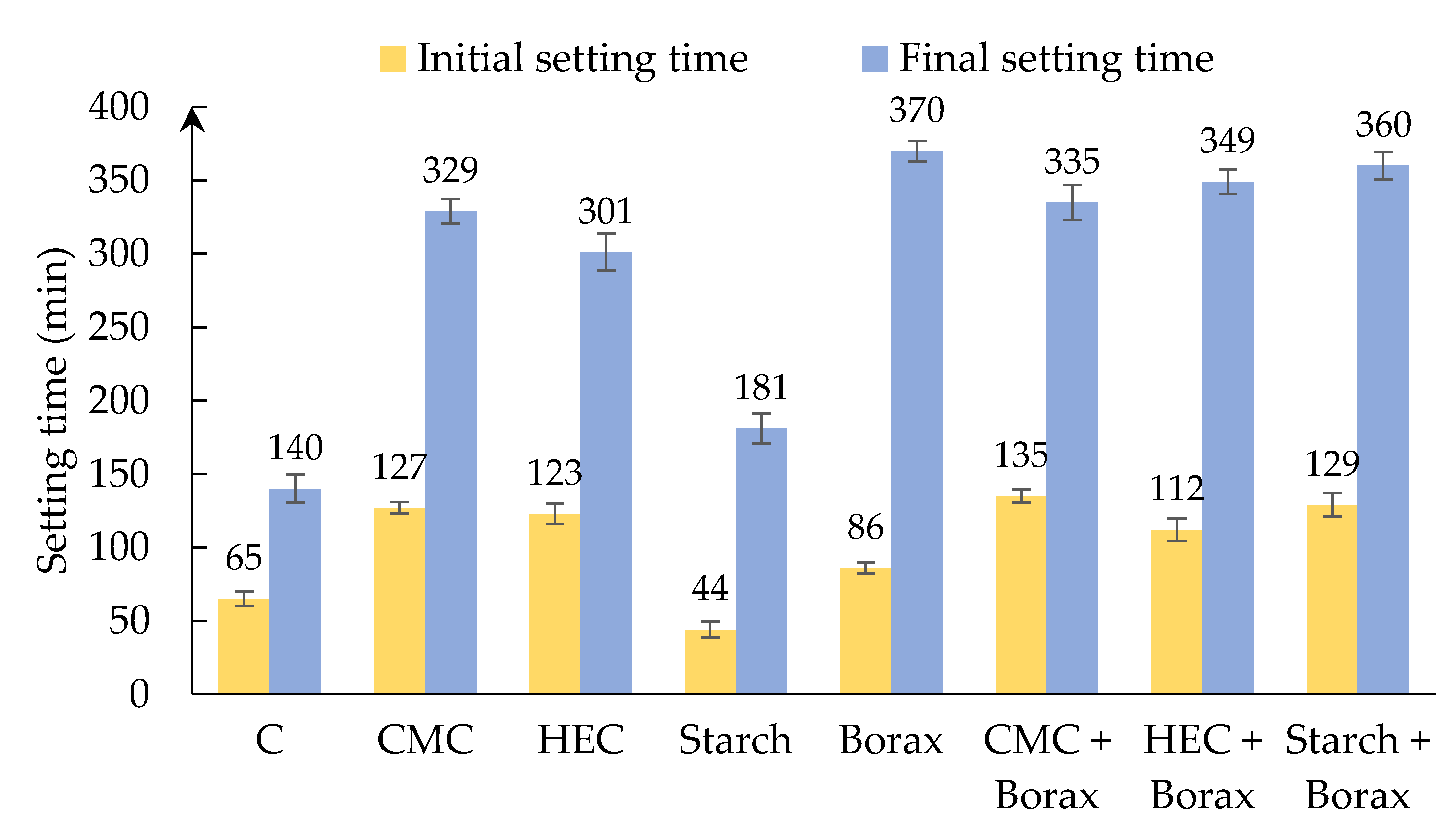

3.2. Workability

The flow workability of was measured using flow workability based on mini slump flow test. The mini slump flow test is a compact and efficient method used to evaluate the flowability and consistency of fresh cement pastes, including those used in geopolymer systems. It involves a small, cone-shaped mold -essentially a scaled-down version of the traditional slump cone—placed on a flat, non-absorbent surface like a glass or plexiglass sheet. Once the mold is filled with paste and carefully lifted, the material spreads out under its own weight. The key measurement in this test is the diameter of the spread, which reflects the material’s fluidity. A larger spread indicates a more workable or flowable mix, while a smaller spread suggests a stiffer consistency. The results of workability properties of geopolymer mortar with additives are given in Figure 4. The retarders did not affect workability but has acted as a fluidizing agent to improve workability. The results indicate that more fluidizing property is imparted by cellulose and starch addition. Significant improvement in workability was obtained by the addition of HEC.

Figure 1.

Flow workability of geopolymer with retarders.

Figure 1.

Flow workability of geopolymer with retarders.

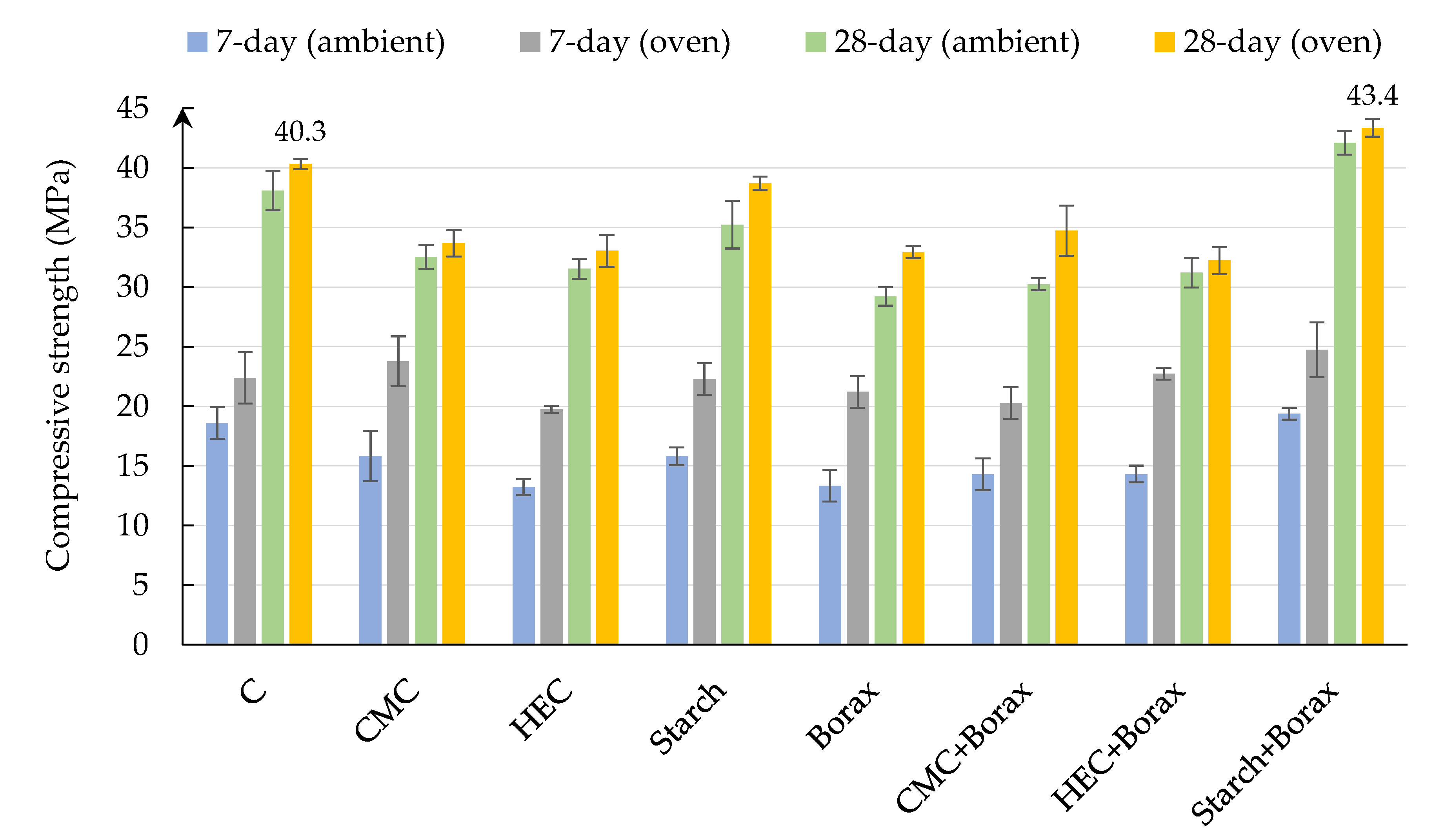

3.3. Compressive Strength

The compressive strength of geopolymer with different retarders are given in

Figure 5. The geopolymer mortars were cured in both ambient conditions and in oven at 60

oC, to evaluate the effect of retarders on the compressive strength development. The mix with starch alone as retarder, and with starch and borax has a positive impact on the compressive strength. All other retarders resulted in a decrease in compressive strength after 28 days for both ambient and oven curing. Borax delays setting too much, preventing polymerization, and trap unreacted alkalis, affecting strength development [

36]. Cellulose interferes with gel packing or introduce micro voids during degradation, which affects the microstructure and strength [

19]. The glucose in the starch may have transformed into acid complexes in alkaline environment, which can chelate the Na

+ ions in the system, and delay the formation of geopolymer [

9]. In the presence of borax, cellulose/starch chars forming an insulating layer, which takes part in the geo-polymerization reaction, forming boron modified aluminosilicate hydrates. The tetrahedral boron directly participate in geo-polymerization, resulting in enhanced polycondensation [

37]. It should be worth noting that higher dosage of borax has detrimental effect, since it complexes with the Al and Si ions, delaying gel formation. Starch alone, while it delays setting, it may not promote strength unless it is used with another agent that balances the reaction kinetics. Starch and borax have a balanced retardation providing controlled geo-polymerization, avoiding flash setting and allowing complete reaction. In addition, the slower and uniform gel formation may have resulted in a denser, and homogenous gel network, which improves the compressive strength.

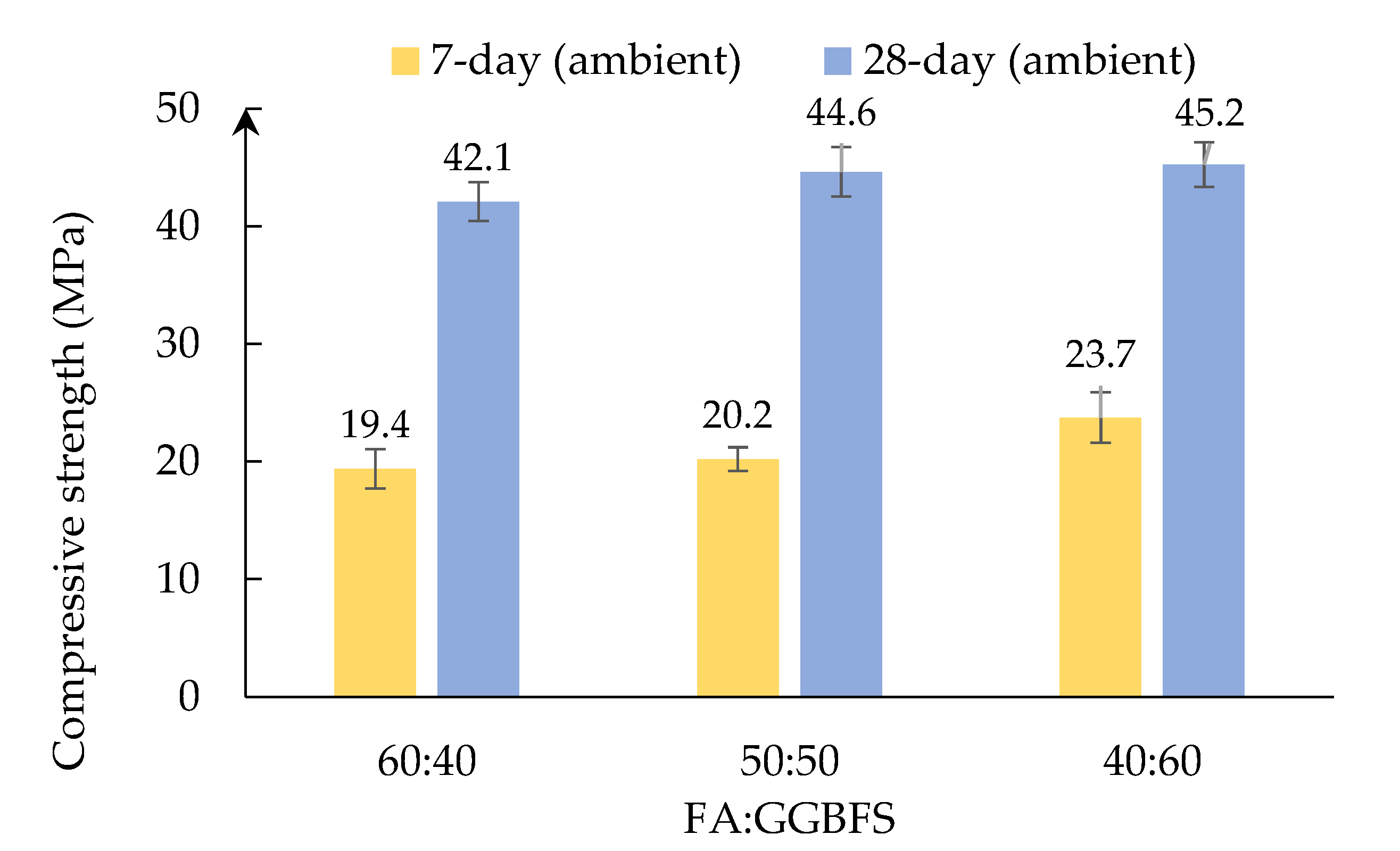

3.4. Compressive Strength of Geopolymer with Varying Binder Proportions

The compressive strength of geopolymer with different FA:GGBFS ratio and starch and borax as the retarders are given in

Figure 6. A clear trend is observed wherein the compressive strength increases with higher GGBFS content, due to the formation of additional CASH gel phases. GGBFS provides readily available calcium ions, which accelerates the polycondensation process, early and higher strength development. The selected retarder combination remains effective across all mixed proportions, demonstrating its compatibility with aluminosilicate precursors. The retardation mechanism is not significantly disrupted by the GGBFS content, the reaction kinetics is maintained without impeding the strength development. The setting time and the strength development is governed by the calcium content, and the compressive strength is least affected by the optimum retarder combination. The system achieved balanced retardation enabling extended workability and consistent strength, without much effect on the mixed proportions.

4. Conclusions

The present study aimed at improving the setting time of FA-GGBFS geopolymer using cellulose, borax and starch as retarders, and the following conclusions are drawn.

Among the different retarders, CMC, HEC and combination of CMC, HEC and starch with borax found to be effective in improving the initial and final setting time. However, starching alone as retarder was found to be less effective. The cellulose forms a waterproofing barrier which hinders the setting time of geopolymer. Cellulose/starch with borax shows synergic effects combining the physical and chemical retardation mechanisms, delaying setting time.

The compressive strength at 28 days improved for the starch and borax retarder combination, compared to the negative effect for all other retarders. The optimum retarder, a combination of starch and borax, has complementary effects that lead to controlled geo-polymerization and a complete reaction.

The retarders were equally effective from the results of oven cured specimens compared to ambient cured ones. For all the specimens, a slight improvement in the 28-day strength was obtained. In addition, the retarder worked well for different mix proportions of FA and GGBFS. The retarder works well in calcium rich geopolymer with aluminosilicate precursors.

While this study focused on a fixed dosage of retarders to identify an effective combination, future research should explore the optimal dosage levels of each retarder, their influence on mechanical properties, and their performance across varying proportions of GGBFS incorporation.

Author Contributions

S.K.J. conceptualized the research methodology, analyzed the data, and wrote original draft. A.C. validated the analysis, reviewed and edited the original draft. M. N., F.K. and N.A.F. collected the resources, investigated, and did the formal analysis. M.M.A. conceptualized, designed the research work and supervised. Y.N. developed the methodology, supervised and reviewed and edited the original draft.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported.

References

- Rowles, M.; O’Connor, B. Chemical Optimisation of the Compressive Strength of Aluminosilicate Geopolymers Synthesised by Sodium Silicate Activation of Metakaolinite. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2003, 13, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. The Geopolymerisation of Alumino-Silicate Minerals. International Journal of Mineral Processing 2000, 59, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, C.A.; Swanepoel, J.C. Utilisation of Fly Ash in a Geopolymeric Material. Applied Geochemistry 2002, 17, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni; Wijaya, S. W.; Hardjito, D. Factors Affecting the Setting Time of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer. Materials Science Forum 2016, 841, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanasak, U.; Pankhet, K.; Chindaprasirt, P. Effect of Chemical Admixtures on Properties of High-Calcium Fly Ash Geopolymer. International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Material 2011, 18, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Lee, S.; Chon, C. Setting Behavior and Phase Evolution on Heat Treatment of Metakaolin-Based Geopolymers Containing Calcium Hydroxide. Materials 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilton, R.; Wang, S.; Banthia, N. Use of Polysaccharides as a Rheology Modifying Admixture for Alkali Activated Materials for 3D Printing. Construction and Building Materials 2025, 458, 139661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, T.; Ramaswamy, K.P.; Saraswathy, B. Effects of Slag and Superplasticizers on Alkali Activated Geopolymer Paste. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2020, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, S.H.; Nematollahi, B.; Nazari, A.; Xia, M.; Sanjayan, J. Efficiency of Different Superplasticizers and Retarders on Properties of “one-Part” Fly Ash-Slag Blended Geopolymers with Different Activators. Materials 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M.; Khalifeh, M.; Samarakoon, S.; Salehi, S.; Wu, Y. Effect of Organic Retarders on Fluid-State and Strength Development of Rock-Based Geopolymer. RILEM Bookseries 2023, 44, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toobpeng, N.; Thavorniti, P.; Jiemsirilers, S. Effect of Additives on the Setting Time and Compressive Strength of Activated High-Calcium Fly Ash-Based Geopolymers. Construction and Building Materials 2024, 417, 135035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni; Herianto, J. G.; Anastasia, E.; Hardjito, D. Effect of Adding Acid Solution on Setting Time and Compressive Strength of High Calcium Fly Ash Based Geopolymer. AIP Conference Proceedings 2017, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusbiantoro, A.; Ibrahim, M.S.; Muthusamy, K.; Alias, A. Development of Sucrose and Citric Acid as the Natural Based Admixture for Fly Ash Based Geopolymer. Procedia Environmental Sciences 2013, 17, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.E.; Muhsin Lebba, A.; Sreeja, S.; Ramaswamy, K.P. Effect of Borax in Slag-Fly Ash-Based Alkali Activated Paste. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2023, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, A.; Wijaya, S.W.; Satria, J.; Sugiarto, A.; Hardjito, D. The Use of Borax in Deterring Flash Setting of High Calcium Fly Ash Based Geopolymer. Materials Science Forum 2016, 857, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, A.; Purwantoro, A.A.T.; Suyanto, W.S.P.D.; Hardjito, D. Fresh and Hardened Properties of High Calcium Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Matrix with High Dosage of Borax. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology—Transactions of Civil Engineering 2020, 44, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhang, Z. Control of Setting Time of Fly Ash Geopolymer. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Architectural, Advances in Engineering Research; Atlantis Press International BV, 2024, Civil and Hydraulic Engineering (ICACHE 2024); pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W. hua; Liu, M. hui Setting Time and Mechanical Properties of Chemical Admixtures Modified FA/GGBS-Based Engineered Geopolymer Composites. Construction and Building Materials 2024, 431, 136473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.R.; Ukrainczyk, N.; Defáveri do Carmo e Silva, K.; Eduardo Silva, L.; Koenders, E. Effect of Microcrystalline Cellulose on Geopolymer and Portland Cement Pastes Mechanical Performance. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 288, 123053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Hoyos, C.; Cristia, E.; Vázquez, A. Effect of Cellulose Microcrystalline Particles on Properties of Cement Based Composites. Materials and Design 2013, 51, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Wu, D.; Guo, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Qu, E.; Liu, J. Effect of Plant Fiber on Early Properties of Geopolymer. Molecules 2023, 28, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IS 3812 (Part 1) Pulverized Fuel Ash-Specification. Bureau of Indian Standards 2003, 1–10.

- IS 4031 (Part 5) Methods of Physical Tests for Hydraulic Cement. Bureau of Indian Standards 1988, Reaffirmed, 1–2.

- ASTM C1611 Standard Test Method for Slump Flow of Self-Consolidating Concrete. American Society for Testing and Materials 2009, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Ishwarya, G.; Singh, B.; Deshwal, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.K. Effect of Sodium Carbonate/Sodium Silicate Activator on the Rheology, Geopolymerization and Strength of Fly Ash/Slag Geopolymer Pastes. Cement and Concrete Composites 2019, 97, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Wang, K.; Fu, C. Shrinkage Behavior of Fly Ash Based Geopolymer Pastes with and without Shrinkage Reducing Admixture. Cement and Concrete Composites 2019, 98, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, B.; Sanjayan, J. Effect of Different Superplasticizers and Activator Combinations on Workability and Strength of Fly Ash Based Geopolymer. Materials and Design 2014, 57, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, S.K.; Nadir, Y.; Cascardi, A.; Arif, M.M.; Girija, K. Effect of Addition of Nanoclay and SBR Latex on Fly Ash-Slag Geopolymer Mortar. Journal of Building Engineering 2023, 66, 105875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C873/C873M-10 Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Concrete Cylinders Cast in Place in Cylindrical Molds. American Society for Testing and Materials 2010.

- ASTM C 191-04 Time of Setting of Hydraulic Cement by Vicat Needle. American Society for Testing and Materials 2004, 1–8.

- Ataie, F.F. Influence of Cementitious System Composition on the Retarding Effects of Borax and Zinc Oxide. Materials 2019, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Qian, C. Effect of Borax on Hydration and Hardening Properties of Magnesium and Pottassium Phosphate Cement Pastes. Journal of Wuhan University of Technology-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2010, 25, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, D.; Jia, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Yu, B. Effects of Mud Content on the Setting Time and Mechanical Properties of Alkali-Activated Slag Mortar. Materials 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baba, T.; Tsujimoto, Y. Examination of Calcium Silicate Cements with Low-Viscosity Methyl Cellulose or Hydroxypropyl Cellulose Additive. BioMed Research International 2016, 4583854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spychał, E.; Stępień, P. Effect of Cellulose Ether and Starch Ether on Hydration of Cement Processes and Fresh-State Properties of Cement Mortars. Materials 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlawan, T.; Tarigan, J.; Ekaputri, J.J.; Nasution, A. Effect of Borax on Very High Calcium Geopolymer Concrete. International Journal on Advanced Science, Engineering and Information Technology 2023, 13, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rożek, P.; Florek, P.; Król, M.; Mozgawa, W. Immobilization of Heavy Metals in Boroaluminosilicate Geopolymers. Materials 2021, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).