Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Chemical Equilibrium

3.1. Chemical Equilibrium, Where K > 1

3.2. Strong Acid and Strong Base pH Calculation

3.3. Weak Acid and Weak Base pH Calculation

3.4. Salts pH Calculation

3.5. Neutralization

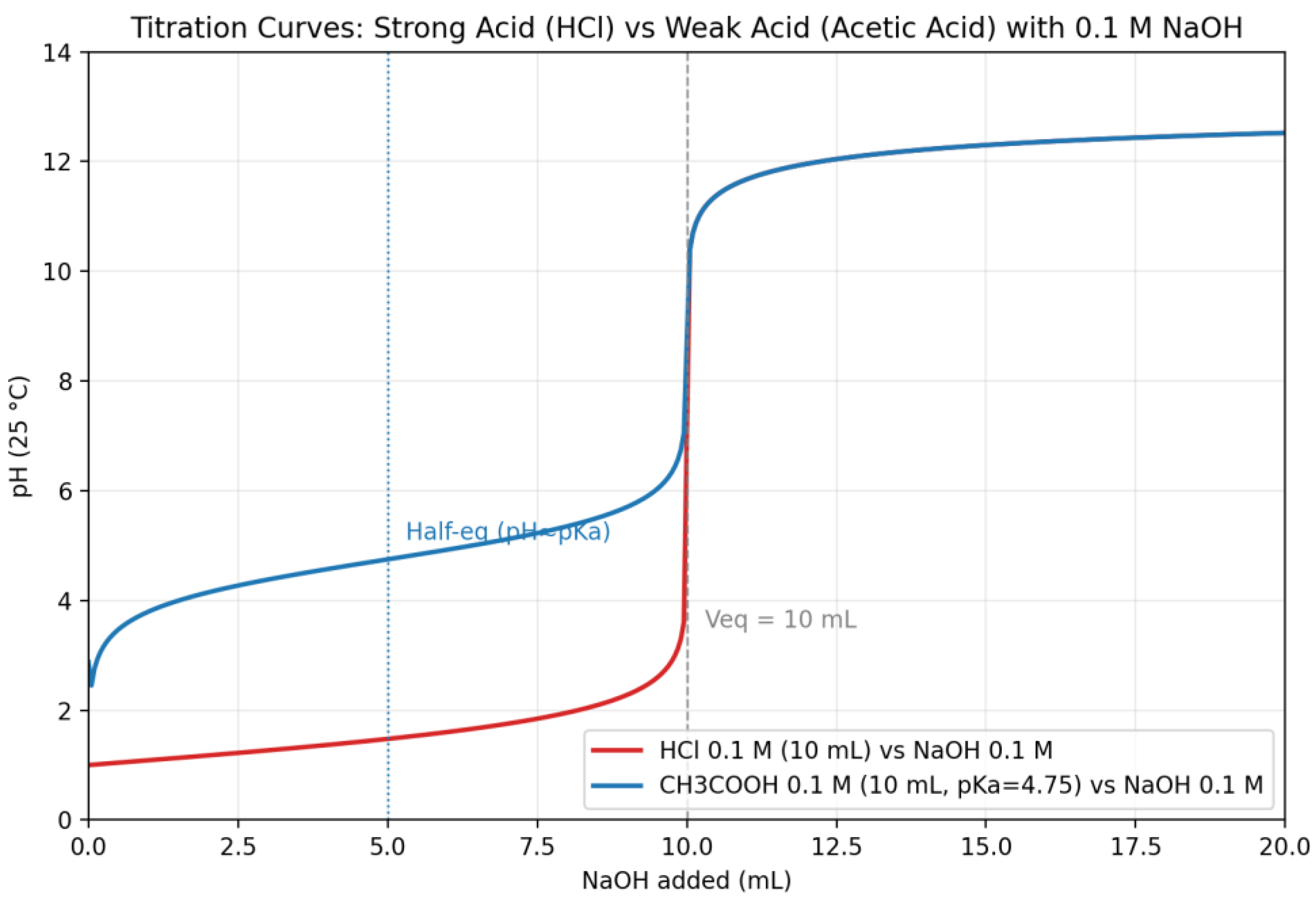

3.6. Titration

3.6. Buffer Calculation

3.7. Calculation {H+] Ratio

3.8. Building Titration Plots

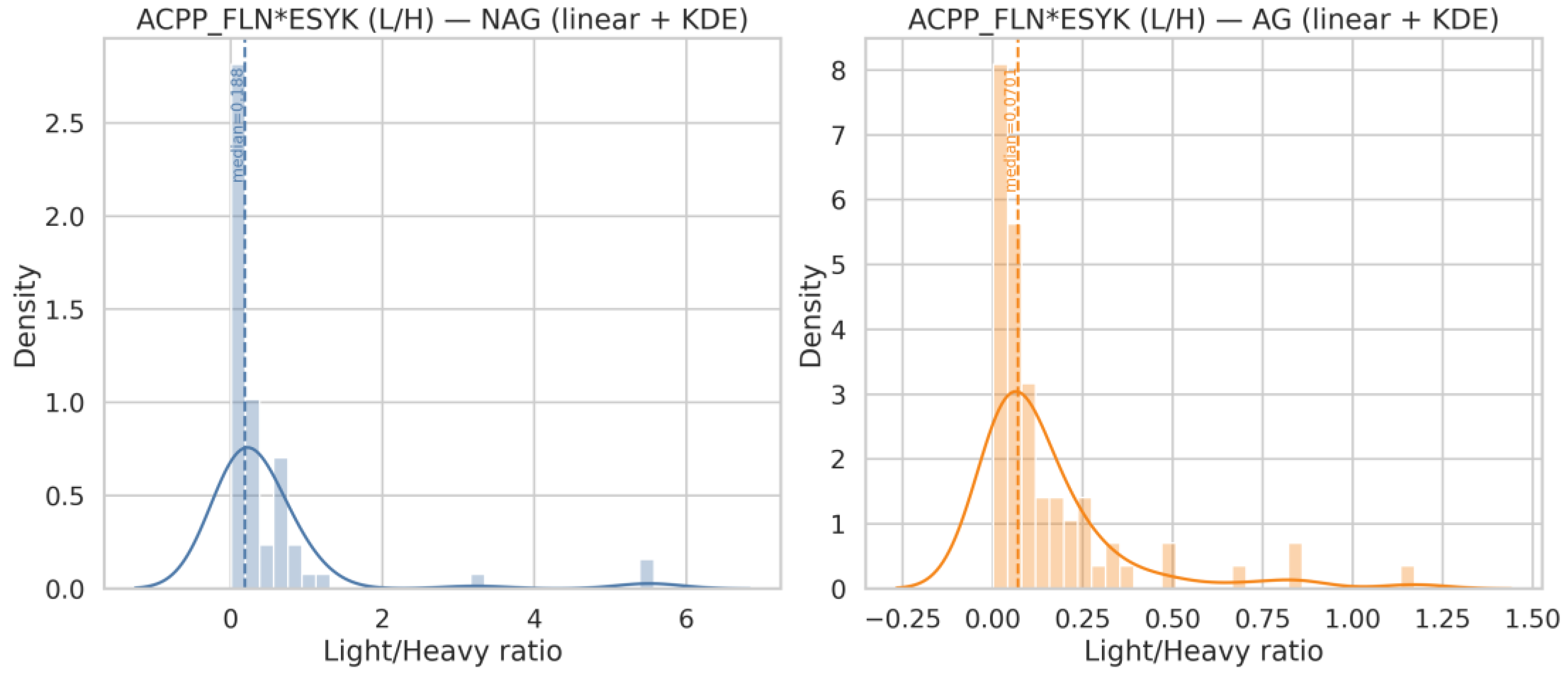

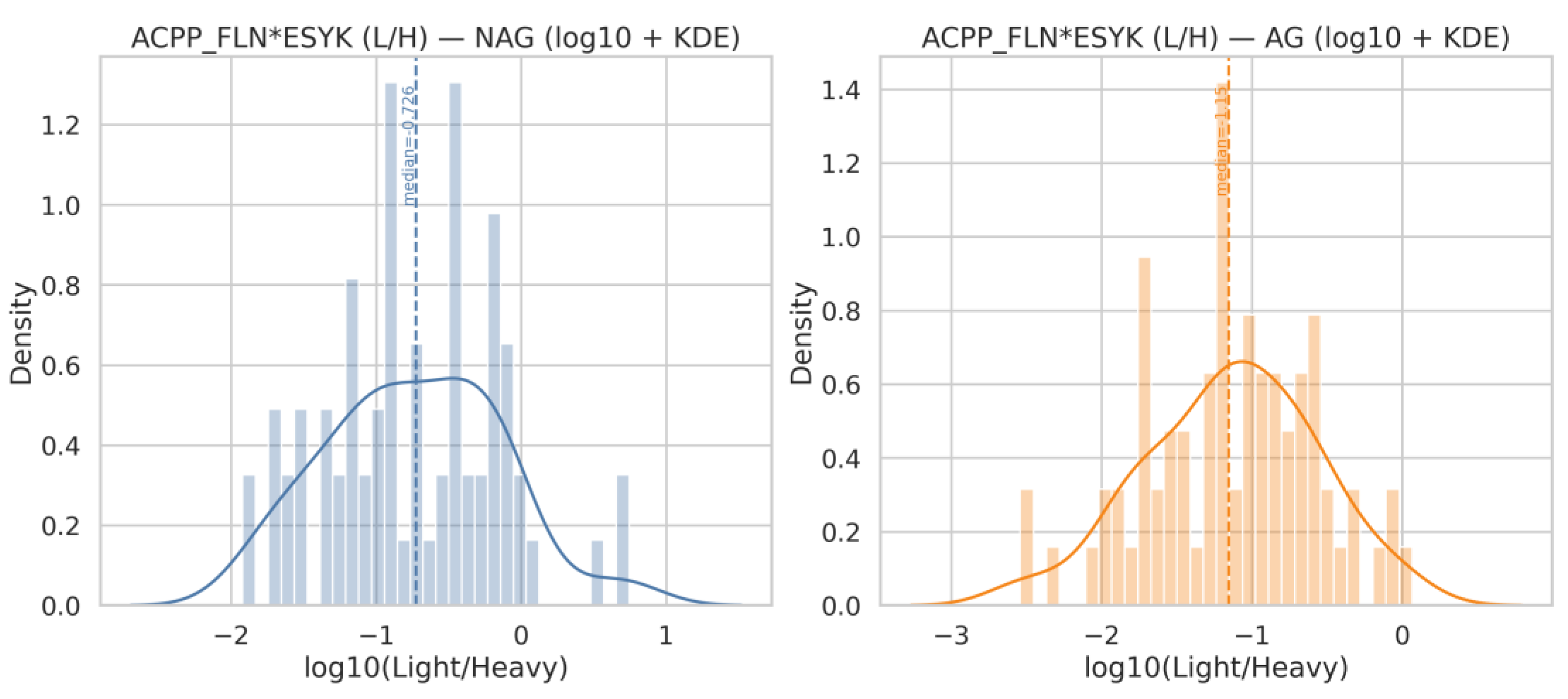

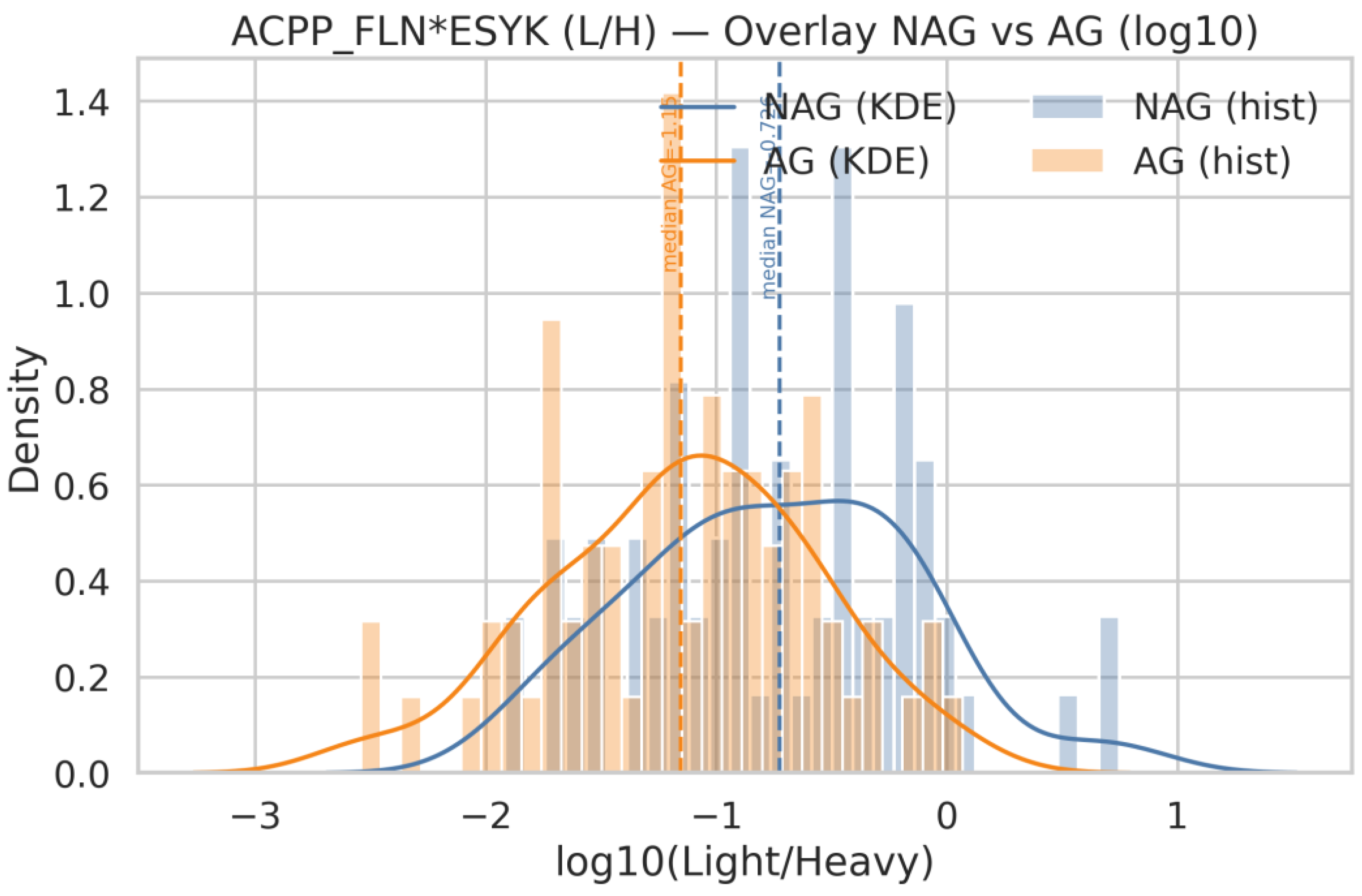

4. Uploading Datasets and Building Images

4.1. Histograms

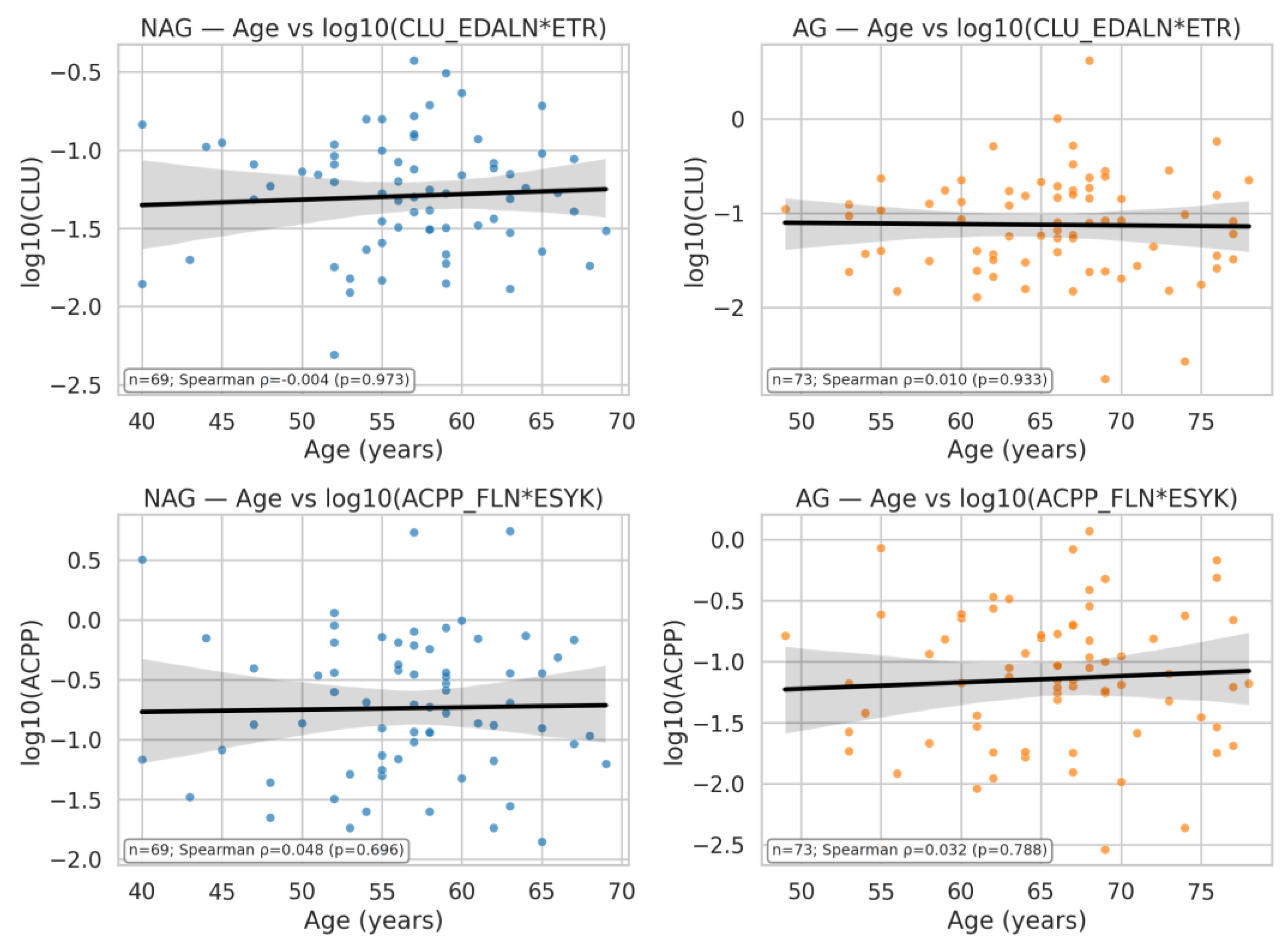

4.3. Correlation Plots

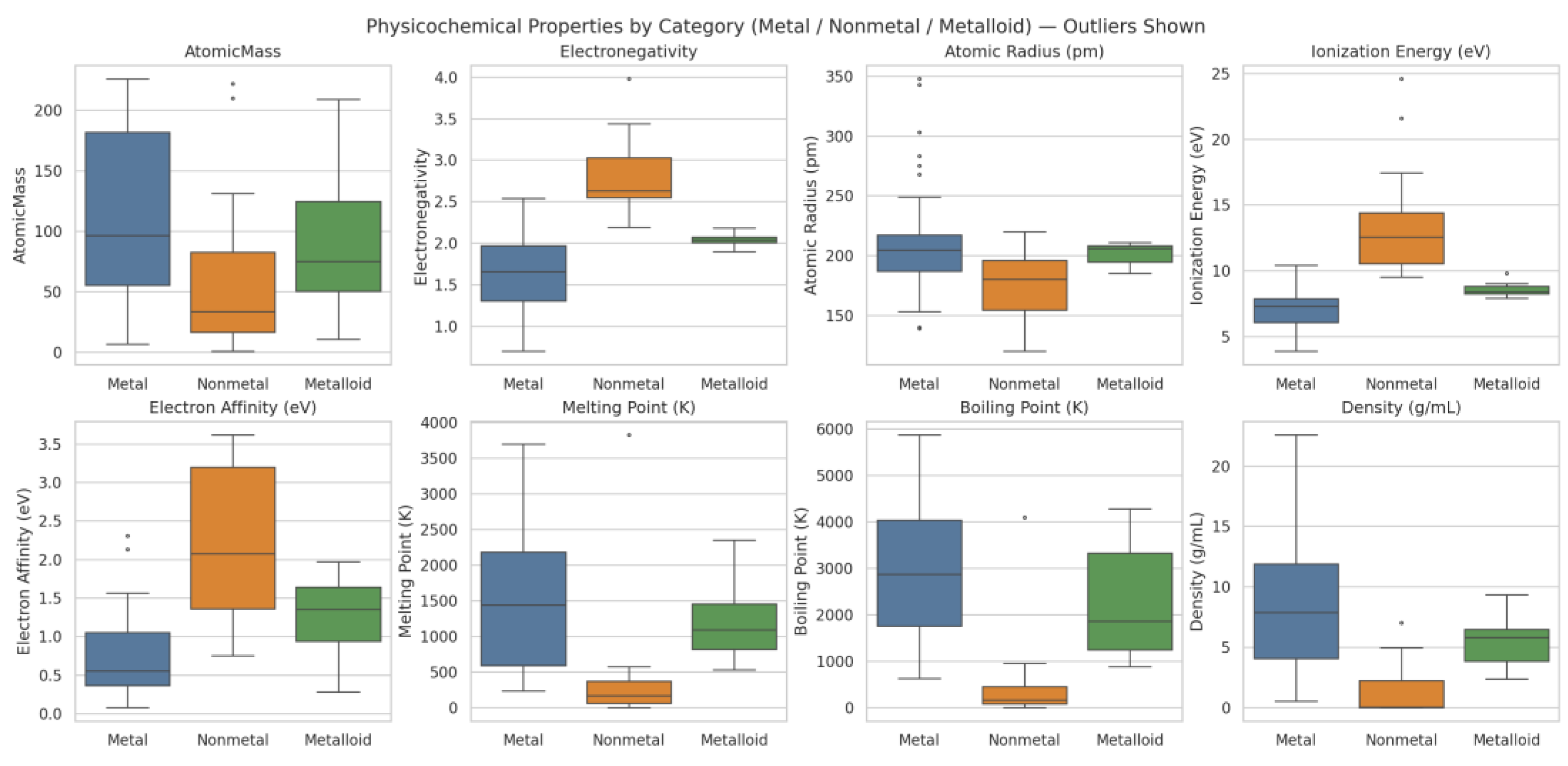

5. Exploring the Physicochemical Properties of Elements in the Periodic Table

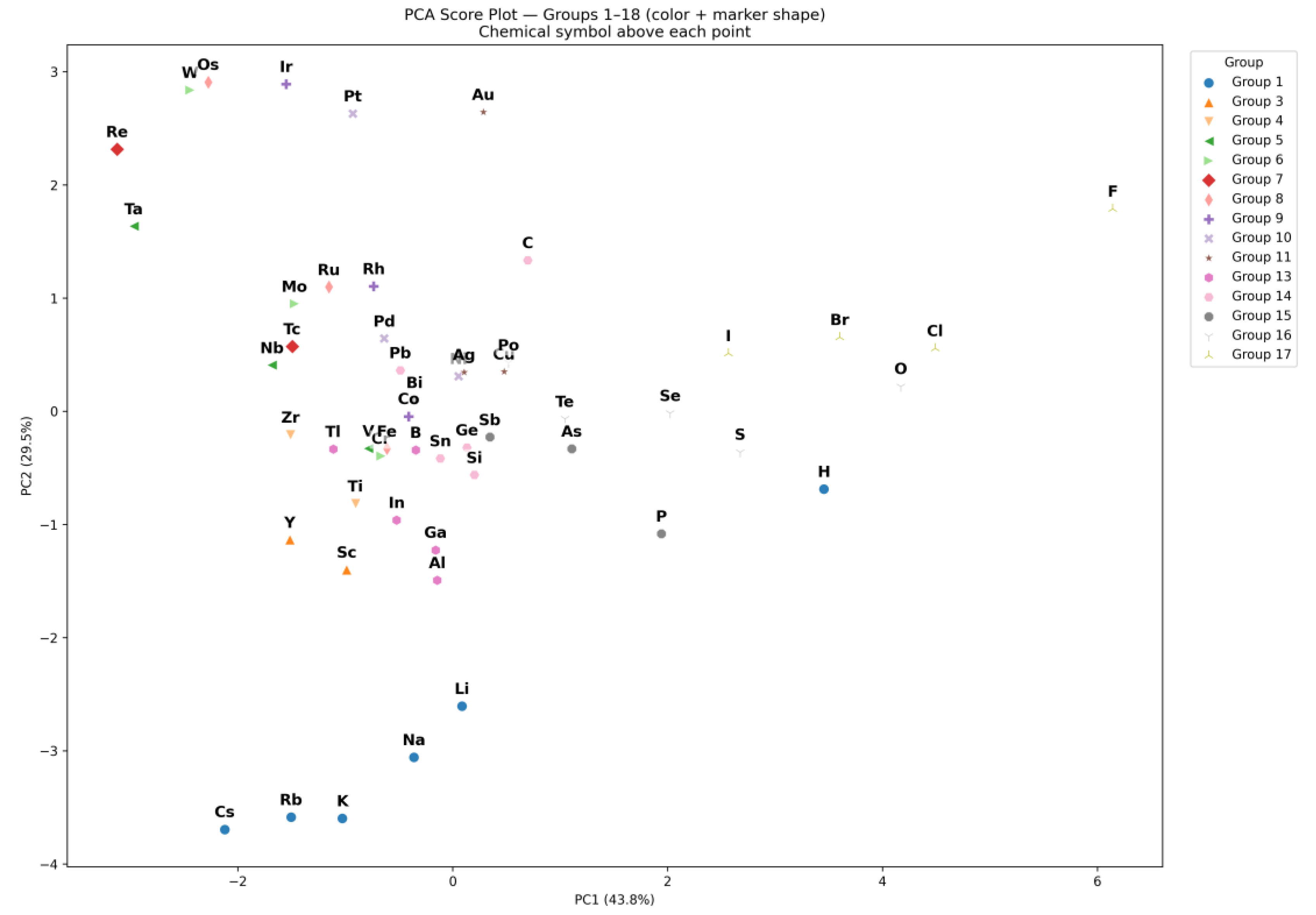

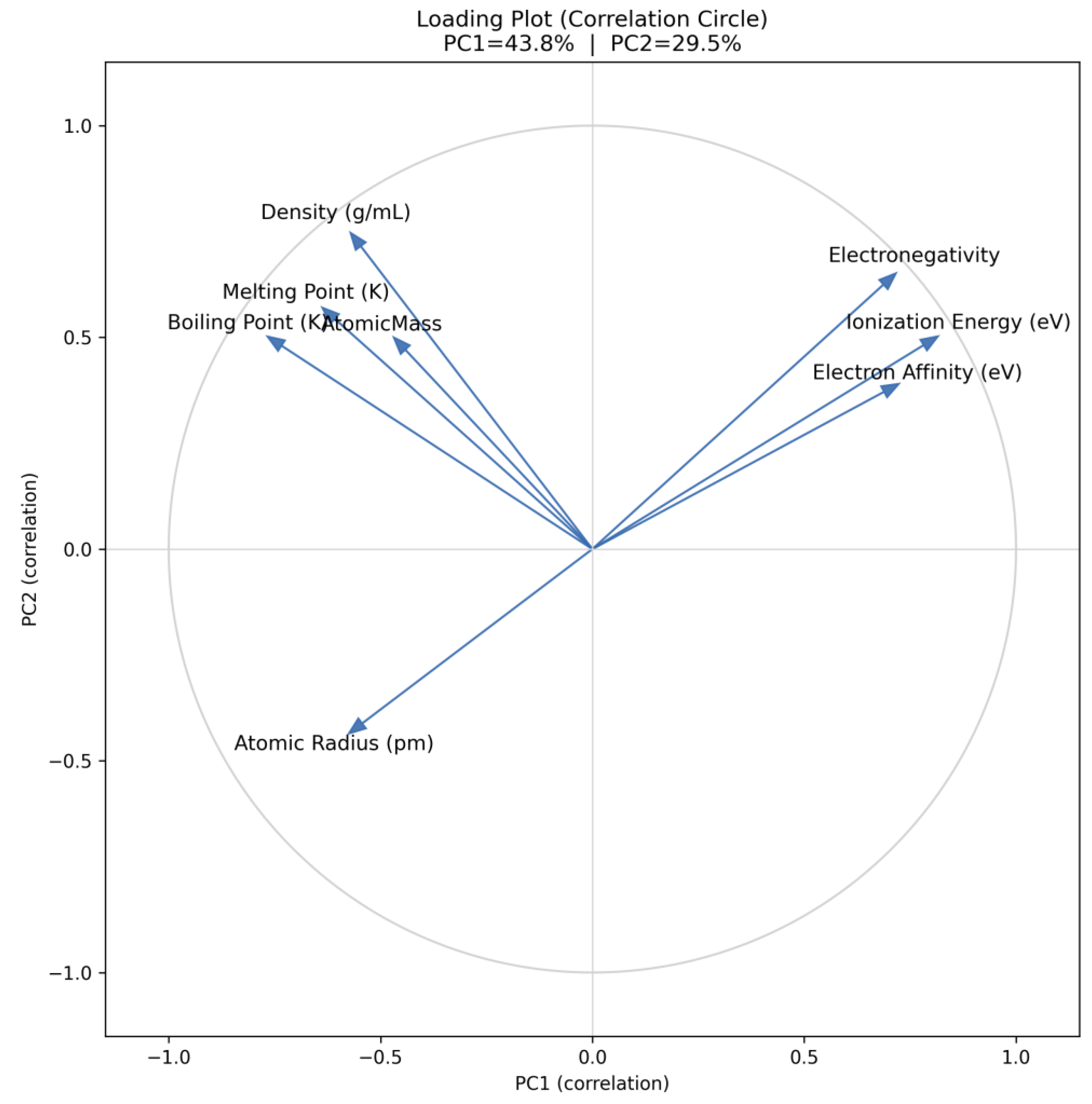

5.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

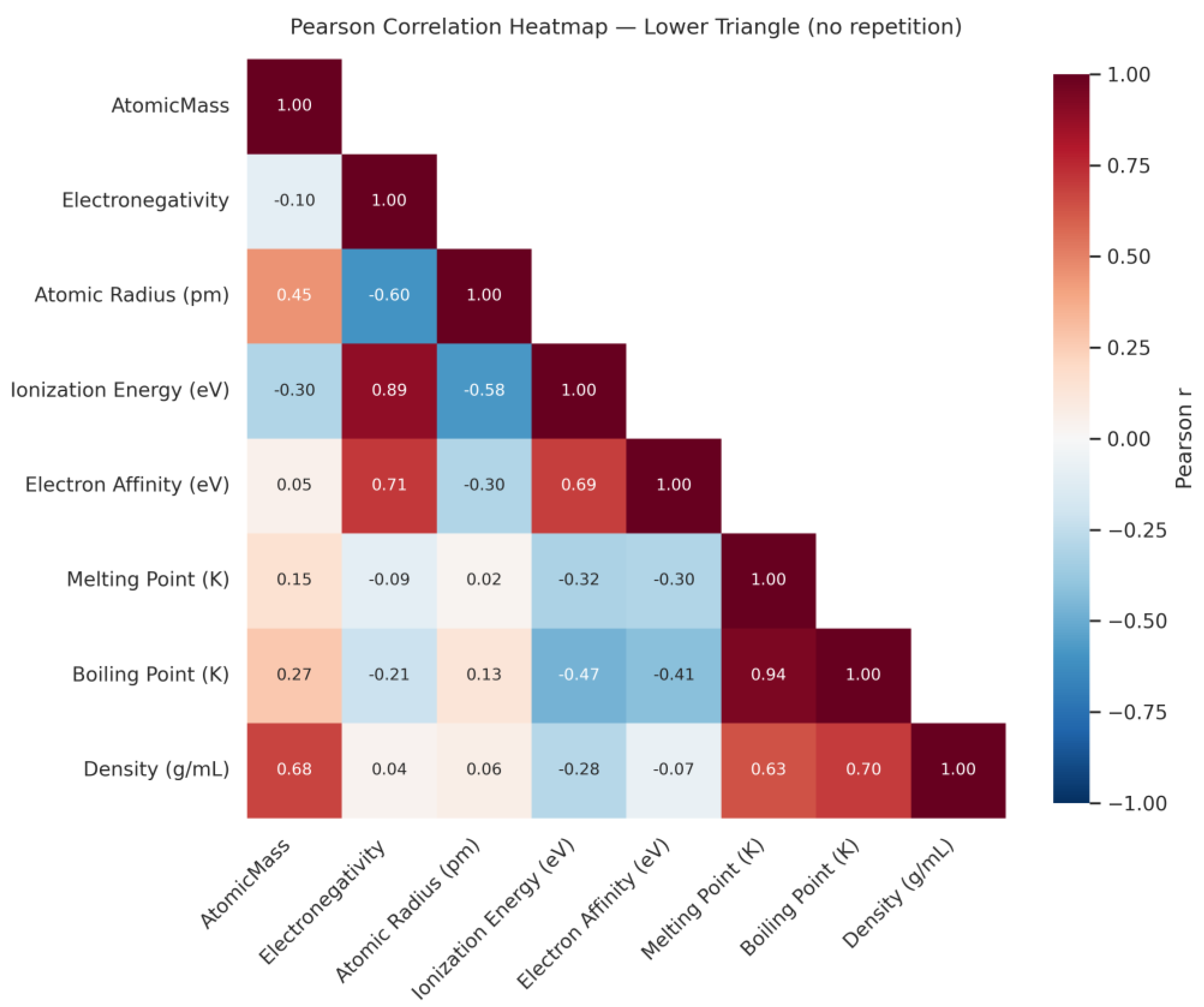

5.2. Correlation Plots of the Physicochemical Properties of Elements in the Periodic Table

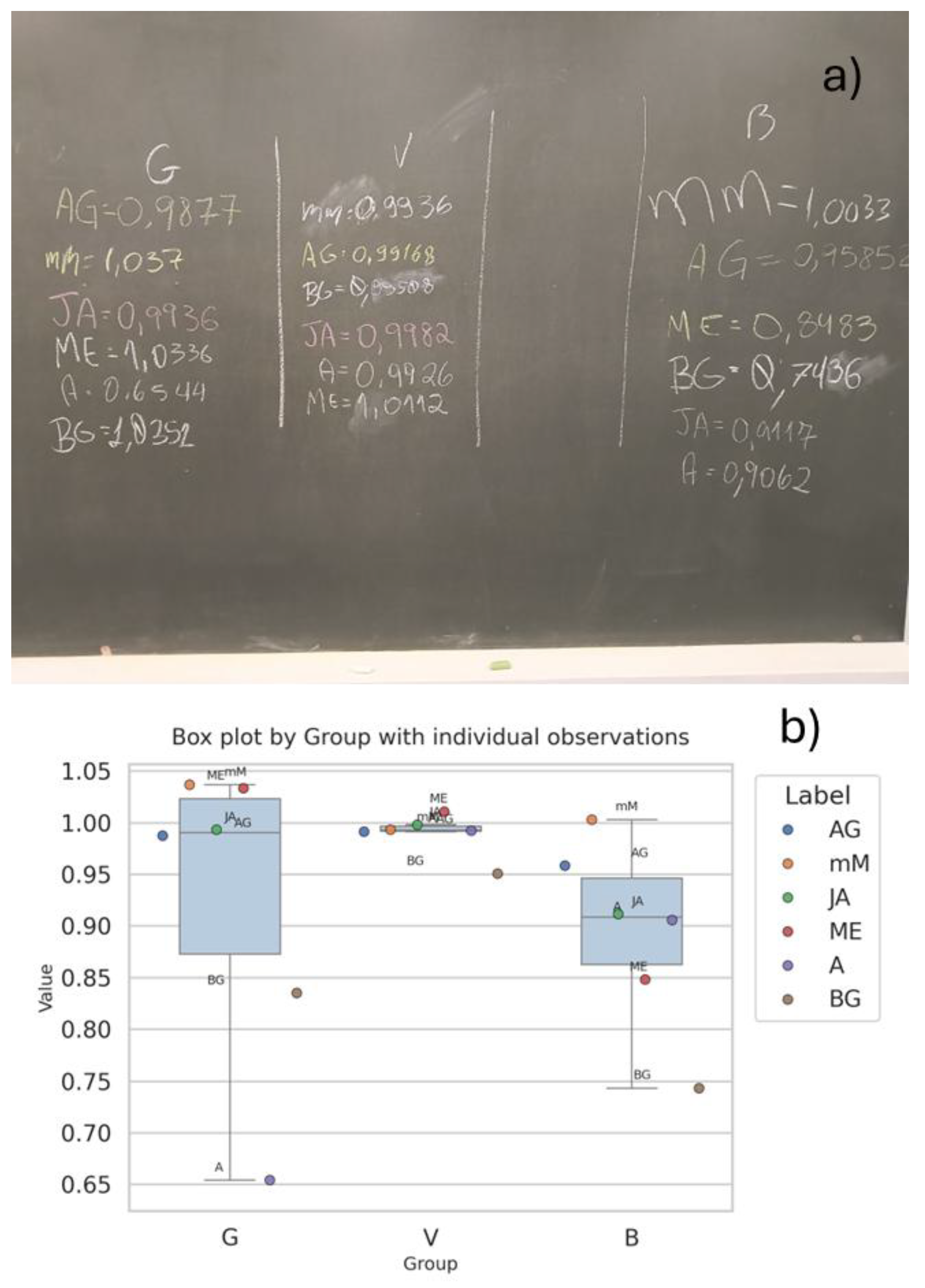

6. Image Interpretation and Generation in Classroom

Conclusion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Madsen, D.Ø.; Toston, D.M. ChatGPT and Digital Transformation: A Narrative Review of Its Role in Health, Education, and the Economy. Digital 2025, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exintaris, B.; Karunaratne, N.; Yuriev, E. Metacognition and Critical Thinking: Using ChatGPT-Generated Responses as Prompts for Critique in a Problem-Solving Workshop (SMARTCHEMPer). J Chem Educ 2023, 100, 2972–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouqian, W.; Fangyuan, C.; Chen, G.; Haofu, S.; Yanxiang, Y.; Junru, G.; Shunlin, Z.; Xingyu, Z. Using Local LLM Tools to Optimize Chinese High School Chemistry Education: Practice, Challenges, and Future Directions. J Chem Educ 2025, 102, 4368–4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lear, B.J. Using ChatGPT-4 to Teach the Design of Data Visualizations. J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 2749–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasinghe, S.M.S.; Gersib, S.G.; Mankad, N.P. Large Language Models (LLMs) as Graphing Tools for Advanced Chemistry Education and Research. J Chem Educ 2025, 102, 1563–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigot, M.; Tassoti, S. An Investigation of Change in Prompting Strategies in a Semester-Long Course on the Use of GenAI. J Chem Educ 2025, 102, 2507–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigot, M.; Tassoti, S. A Missed Opportunity for No-Code Chatbots? Current Challenges in Publicly Available Chemistry GPTs. J Chem Educ 2025, 102, 2151–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, E. Scientists Flock to DeepSeek: How They’re Using the Blockbuster AI Model. Nature 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, J. China Made Waves with Deepseek, but Its Real Ambition Is AI-Driven Industrial Innovation. Nature 2025, 638, 609–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibney, E. China’s Cheap, Open AI Model DeepSeek Thrills Scientists. Nature 2025, 638, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento Júnior, W.J.D.; Morais, C.; Girotto Júnior, G. Enhancing AI Responses in Chemistry: Integrating Text Generation, Image Creation, and Image Interpretation through Different Levels of Prompts. J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 3767–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasadi, E.A.; Baiz, C.R. Multimodal Generative Artificial Intelligence Tackles Visual Problems in Chemistry. J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 2716–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geantă, M.; Bădescu, D.; Chirca, N.; Nechita, O.C.; Radu, C.G.; Rascu, Ș.; Rădăvoi, D.; Sima, C.; Toma, C.; Jinga, V. The Emerging Role of Large Language Models in Improving Prostate Cancer Literacy. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaner, M.C.; Anguita, R.; Antaki, F.; Balas, M.; Boberg-Ans, L.C.; Ferro Desideri, L.; Grauslund, J.; Hansen, M.S.; Klefter, O.N.; Potapenko, I.; et al. Opportunities and Challenges of Chatbots in Ophthalmology: A Narrative Review. J Pers Med 2024, 14, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ittarat, M.; Cheungpasitporn, W.; Chansangpetch, S. Personalized Care in Eye Health: Exploring Opportunities, Challenges, and the Road Ahead for Chatbots. J Pers Med 2023, 13, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabijan, A.; Chojnacki, M.; Zawadzka-Fabijan, A.; Fabijan, R.; Piątek, M.; Zakrzewski, K.; Nowosławska, E.; Polis, B. AI-Powered Western Blot Interpretation: A Novel Approach to Studying the Frameshift Mutant of Ubiquitin B (UBB+1) in Schizophrenia. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.S.; Fan, K.H. Dermatological Knowledge and Image Analysis Performance of Large Language Models Based on Specialty Certificate Examination in Dermatology. Dermato 2024, 4, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuessler, K.; Rodemer, M.; Giese, M.; Walpuski, M. Organic Chemistry and the Challenge of Representations: Student Difficulties with Different Representation Forms When Switching from Paper–Pencil to Digital Format. J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 4566–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, D.; Enderle, B.; Pham, J. Teaching Formal Charges of Lewis Electron Dot Structures by Counting Attachments. J Chem Educ 2025, 102, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzolani, S.P.; Mistretta, M.J.; Bugajczyk, A.E.; Sam, A.J.; Elezi, S.R.; Silverio, D.L. Effective Visualization of Implicit Hydrogens with Prime Formulae. J Chem Educ 2025, 102, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayyar, P.; Young, J.D.; Dawood, L.; Lewis, S.E. Evaluating an Intervention to Improve General Chemistry Students’ Perceptions of the Utility of Chemistry. J Chem Educ 2025, 102, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.M.; Grove, N.; Underwood, S.M.; Klymkowsky, M.W. Lost in Lewis Structures: An Investigation of Student Difficulties in Developing Representational Competence. J Chem Educ 2010, 87, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yik, B.J.; Dood, A.J. ChatGPT Convincingly Explains Organic Chemistry Reaction Mechanisms Slightly Inaccurately with High Levels of Explanation Sophistication. J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 1836–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.K.; Franz, J.L.; Hein, S.M.; Leverentz-Culp, H.R.; Mauser, J.F.; Ruff, E.F.; Zemke, J.M. An Analysis of AI-Generated Laboratory Reports across the Chemistry Curriculum and Student Perceptions of ChatGPT. J Chem Educ 2023, 100, 4351–4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, T.; Gupta, O.; Chawla, G. The Future of ChatGPT in Medicinal Chemistry: Harnessing AI for Accelerated Drug Discovery. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, A.J. An Investigation into ChatGPT’s Application for a Scientific Writing Assignment. J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 1959–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Lee, D. Leveraging ChatGPT for Enhancing Critical Thinking Skills. J Chem Educ 2023, 100, 4876–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, S.; Botha, M.; Ostovar, M. Evaluating Academic Answers Generated Using ChatGPT. J Chem Educ 2023, 100, 1672–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, A.J.; Vidhani, D. ChatGPT Needs a Chemistry Tutor Too. J Chem Educ 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.A.; López-Torres, M.; Fernández, J.J.; Vázquez-García, D. ChatGPT as an Instructor’s Assistant for Generating and Scoring Exams. J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 3780–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berber, S.; Brückner, M.; Maurer, N.; Huwer, J. Artificial Intelligence in Chemistry Research─Implications for Teaching and Learning. J Chem Educ 2025, 102, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayyar, P.; Teran, O.A.; Lewis, S.E. Artificial Intelligence as a Catalyst for Promoting Utility Value Perceptions of Chemistry. J Chem Educ 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrubeš, J.; Jaroš, A.; Nemirovich, T.; Teplá, M.; Petrželová, S. Integrating Computational Chemistry into Secondary School Lessons. J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 2343–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.M.; Tafini, N. Exploring the AI–Human Interface for Personalized Learning in a Chemical Context. J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 4916–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.M.; Anderson, E.; Dickson-Karn, N.M.; Soltanirad, C.; Tafini, N. Comparing the Performance of College Chemistry Students with ChatGPT for Calculations Involving Acids and Bases. J Chem Educ 2023, 100, 3934–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shallcross, D.E.; Davies-Coleman, M.T.; Lloyd, C.; Dennis, F.; McCarthy-Torrens, A.; Heslop, B.; Eastman, J.; Baldwin, T.; Thistlethwaite, I. Smart Worksheets and Their Positive Impact on a First-Year Quantitative Chemistry Course. J Chem Educ 2025, 102, 1062–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrier, J. Comment on “Comparing the Performance of College Chemistry Students with ChatGPT for Calculations Involving Acids and Bases. ” J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 1782–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.M. Investigating the Use of an Artificial Intelligence Chatbot with General Chemistry Exam Questions. J Chem Educ 2023, 100, 1905–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margoum, S.; Berrada, K.; Burgos, D.; El Hasri, S. Microcomputer-Based Laboratory Role in Developing Students’ Conceptual Understanding in Chemistry: Case of Acid–Base Titration. J Chem Educ 2022, 99, 2548–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz Nieves, E.L.; Barreto, R.; Medina, Z. JCE Classroom Activity #111: Redox Reactions in Three Representations. J Chem Educ 2012, 89, 643–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Fu, S.; Wang, G.; Yu, J.; Fu, Q. Inquiry-Based Investigation of the Influencing Factors on the Redox Titration Curves by Simulation. J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 3301–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrs, P.S. Class Projects in Physical Organic Chemistry: The Hydrolysis of Aspirin. J Chem Educ 2004, 81, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, N.L.; Le, B.; Ward, R.; Hansen, S.J.R.; Ulichny, J.C. Titrating Consumer Acids to Uncover Student Understanding: A Laboratory Investigation Leading to Data-Driven Instructional Interventions. J Chem Educ 2022, 99, 2378–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, M.; Hamer, M.; Vago, M.J.; Leal Denis, M.F. Real-World Sample-Based Teaching in Analytical Chemistry: Afterthoughts on a Hands-On Experience. J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucy, C.A. Is Your Henderson–Hasselbalch Calculation of Buffer PH Correct? J Chem Educ 2023, 100, 2418–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergantis, S.A.; Saridakis, I.; Lyratzakis, A.; Mavroudakis, L.; Montagnon, T. Buffer Squares: A Graphical Approach for the Determination of Buffer PH Using Logarithmic Concentration Diagrams. J Chem Educ 2019, 96, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gómez, D.; Airado Rodríguez, D.; Cañada-Cañada, F.; Jeong, J.S. A Comprehensive Application To Assist in Acid–Base Titration Self-Learning: An Approach for High School and Undergraduate Students. J Chem Educ 2015, 92, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Fu, S.; Yang, H.; Yu, J.; Liu, L. Prelaboratory Practice with a Titration Simulation Program for Carbonate Mixtures. J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Lih, T.S.M.; Höti, N.; Chen, S.Y.; Ponce, S.; Partin, A.; Zhang, H. Development of Parallel Reaction Monitoring Assays for the Detection of Aggressive Prostate Cancer Using Urinary Glycoproteins. J Proteome Res 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, E.M. Hypothesis Tests and Exploratory Analysis Using R Commander and Factoshiny. J Chem Educ 2023, 100, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.S.; Sequeira, C.A.; Borges, E.M. Enhancing Statistical Education in Chemistry and STEAM Using JAMOVI. Part 1: Descriptive Statistics and Comparing Independent Groups. J Chem Educ 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.G.; Özgün-Koca, A.; Barr, J. Interpretations of Boxplots: Helping Middle School Students to Think Outside the Box. Journal of Statistics Education 2017, 25, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.E. V.; Miranda, R.M.; Figueiredo, A.F.; Barbosa, J.P.; Brasil, E.M. Box-and-Whisker Plots Applied to Food Chemistry. J Chem Educ 2016, 93, 2026–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, E.M. Data Visualization Using Boxplots: Comparison of Metalloid, Metal, and Nonmetal Chemical and Physical Properties. J Chem Educ 2023, 100, 2809–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupp, A.M.; Kovarik, M.L.; McCurry, D.A. Emerging Areas in Undergraduate Analytical Chemistry Education: Microfluidics, Microcontrollers, and Chemometrics. Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry 2024, 17, 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidou, L.F.; Borges, E.M. Teaching Principal Component Analysis Using a Free and Open Source Software Program and Exercises Applying PCA to Real-World Examples. J Chem Educ 2020, 97, 1666–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, E.J. Series of Jupyter Notebooks Using Python for an Analytical Chemistry Course. J Chem Educ 2020, 97, 3899–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuente, D.; Cohen, B.; Fiorini, G.; García, A.A.; Bringas, M.; Morzan, E.; Onna, D. A Gentle Introduction to Machine Learning for Chemists: An Undergraduate Workshop Using Python Notebooks for Visualization, Data Processing, Analysis, and Modeling. J Chem Educ 2021, 98, 2892–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Jeon, I.; Kang, S.-J. Integrating Data Science and Machine Learning to Chemistry Education: Predicting Classification and Boiling Point of Compounds. J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 1771–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bro, R.; Smilde, A.K. Principal Component Analysis. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 2812–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, C.A.; Borges, E.M. Enhancing Statistical Education in Chemistry and STEAM Using JAMOVI. Part 2. Comparing Dependent Groups and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). J Chem Educ 2024, 101, 5040–5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.-S. Open-Source Visual Programming Software for Introducing Principal Component Analysis to the Analytical Curriculum. J Chem Educ 2025, 102, 1428–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira de Quental, A.G.; Firmino do Nascimento, A.L.; de Lelis Medeiros de Morais, C.; de Oliveira Neves, A.C.; Seixas das Neves, L.; Gomes de Lima, K.M. Periodic Table’s Properties Using Unsupervised Chemometric Methods: Undergraduate Analytical Chemistry Laboratory Exercise. J Chem Educ 2025, 102, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L. Teaching Principal Component Analysis in the Course of Analytical Chemistry: A Q&A Based Heuristic Approach. J Chem Educ 2025, 102, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, D.; Santos, J.S.; Escher, G.B.; Ferreira, B.L.; Maggio, R.M. Use of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) for Multivariate Association between Bioactive Compounds and Functional Properties in Foods: A Critical Perspective. Trends Food Sci Technol 2018, 72, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.A.; Alvarenga, V.O.; de Souza Sant’Ana, A.; Santos, J.S.; Granato, D. The Use of Statistical Software in Food Science and Technology: Advantages, Limitations and Misuses. Food Research International 2015, 75, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, A.A.F.; Haminiuk, C.W.I.; Nunes, C.A.; Schnitzler, E.; van Ruth, S.M.; Granato, D. Chemical Composition, Sensory Properties, Provenance, and Bioactivity of Fruit Juices as Assessed by Chemometrics: A Critical Review and Guideline. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2014, 13, 300–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant St James, A.; Hand, L.; Mills, T.; Song, L.S.J.; Brunt, A.; Bergstrom Mann, P.E.F.; Worrall, A.I.; Stewart, M.; Vallance, C. Exploring Machine Learning in Chemistry through the Classification of Spectra: An Undergraduate Project. J Chem Educ 2023, 100, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackey, H.E.; Sell, R.L.; Nelson, G.L.; Bryan, T.A.; Lines, A.M.; Bryan, S.A. Practical Guide to Chemometric Analysis of Optical Spectroscopic Data. J Chem Educ 2023, 100, 2608–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva de Souza, R.; Borges, E.M. Teaching Descriptive Statistics and Hypothesis Tests Measuring Water Density. J Chem Educ 2023, 100, 4438–4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questions | Task |

| Q1 | Calculate the amount of ethyl ethanoate formed when 2 moles of ethanoic acid and 3 moles of ethanol and 8 moles of water are allowed to come to equilibrium. The equilibrium constant for the reaction is 3.0. |

| Q2 | Calculate the pH of 0.025 M HI |

| Q3 | Calculate the pH of 0.025 M Sr(OH)₂ |

| Q4 | Calculate the pH of 2.0 M HF. Ka for HF = 6.6 × 10⁻⁴ |

| Q5 | Calculate the pH of 2.0 M CH₃NH₂. Kb for CH₃NH₂ = 4.38 × 10⁻⁴ |

| Q6 | Calculate the pH of 0.25 M NH₄Cl. Kb for NH₃ = 1.8 × 10⁻⁵ |

| Q7 | Calculate the pH of 0.25 M NaF. Ka for HF = 6.6 × 10⁻⁴ |

| Q8 | How many mL of 0.20 M KOH are needed to neutralize 150 mL of 0.020 M H₂SO₄? |

| Q9 | How many mL of 0.20 M HCl are needed to neutra lize 150 mL of 0.020 M Ca(OH)₂? |

| Q10 | If 25.0 mL of 0.25 M HNO₃ is combined with 15.0 mL of 0.25 M CH₃NH₂, what is the pH? Kb = 4.38 × 10⁻⁴ |

| Q11 | : If 25.0 mL of 0.25 M NaOH is combined with 15.0 mL of 0.25 M CH₃COOH, what is the pH? Ka = 1.8 × 10⁻⁵ |

| Q12 | A household cleaner contains ammonia. A 25.37 g sample of the cleaner is dissolved in water and made up to 250 cm3. A 25.0 cm3 portion of this solution requires 37.3 cm3 of 0.360 mol dm-3 sulfuric acid for neutralization. What is the percentage by mass of ammonia in the cleaner? |

| Q13 | 8.492 g of Ammonium iron (II) sulphate crystals ((NH4)2SO4.FeSO4.nH2O) were dissolved in water and the solution was made up to 250 cm3 with distilled water and diluted sulphuric acid. A 25.0 cm3 portion of the solution was further acidified and titrated against potassium permanganate (VII) solution of concentration 0.0150 mol dm-3, requiring 22.5 cm3 for neutralization to be achieved. Determine the value of n. |

| Q14 | An aspirin tablet was ground using a glass rod, and 25 mL of a 1.0 mol/L NaOH solution was added to the powder. The mixture was then heated for 15 minutes to ensure complete reaction. After cooling, the excess NaOH was titrated with 20 mL of a 0.5 mol/L H₂SO₄ solution. Based on this data, calculate the mass of aspirin present in the tablet. (Molar mass of aspirin = 180.1574 g/mol). The aspirin was neutralized by NaOH, the, it was hydrolyzed to salicylic acid |

| Q15 | How many moles of sodium ethanoate must be added to 1.00 dm3 of 0.0100 mol dm-3 of ethanoic acid to produce a buffer solution of pH 5.8? |

| Q16 | : Calculate the pH of the following solutions: a) HCl, 0.1 mol/L b) Acetic acid, 0.1 mol/L (pKa = 4.75) c) How many times is the [H⁺] concentration in the HCl solution greater than that in the acetic acid solution? |

| Q17 | .For 10 mL of HCl (0.1 mol/L) and 10 mL of acetic acid (0.1 mol/L, pKa = 4.75), each titrated with NaOH (0.1 mol/L).Present both titration curves on the same graph for comparison. |

| Load the spreadsheet 1 | |

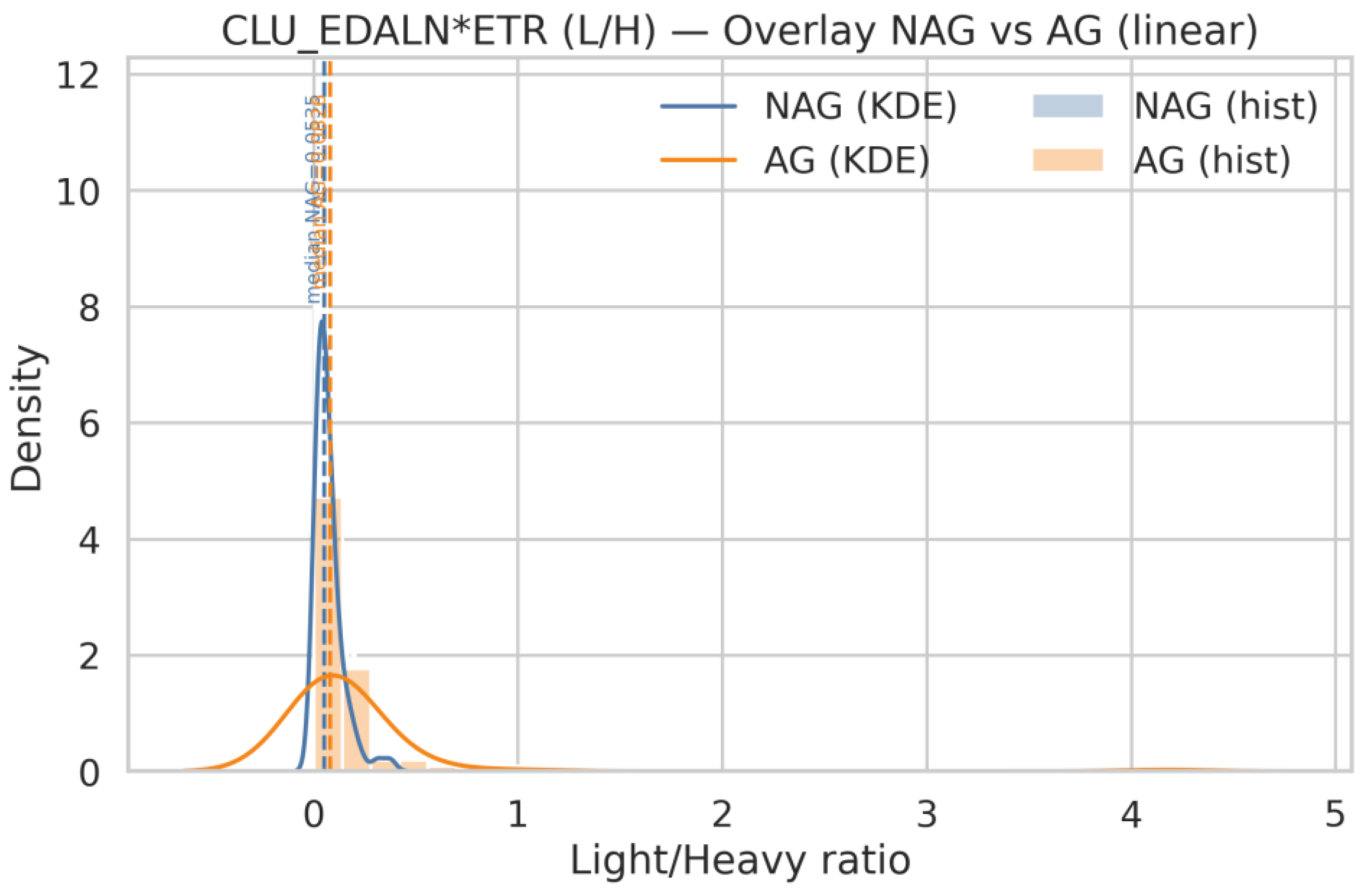

| Q18 | Generate histograms for ACPP_FLN*ESYK (Light/Heavy) and, split by AG and NAG groups. Display both linear and logarithmic scales, include KDE (kernel density estimation) curves, and overlay the NAG and AG distributions on the same axis for comparison |

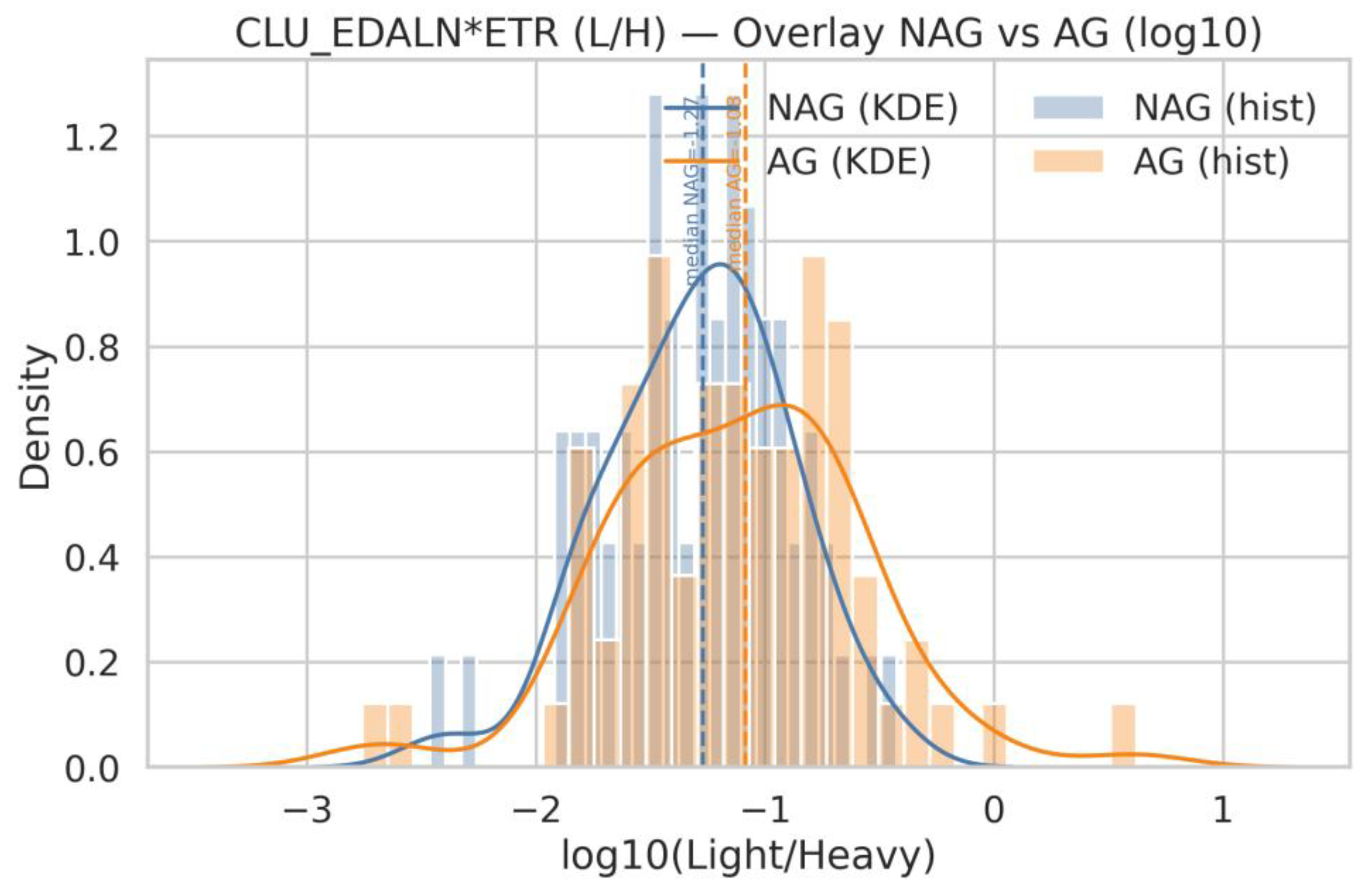

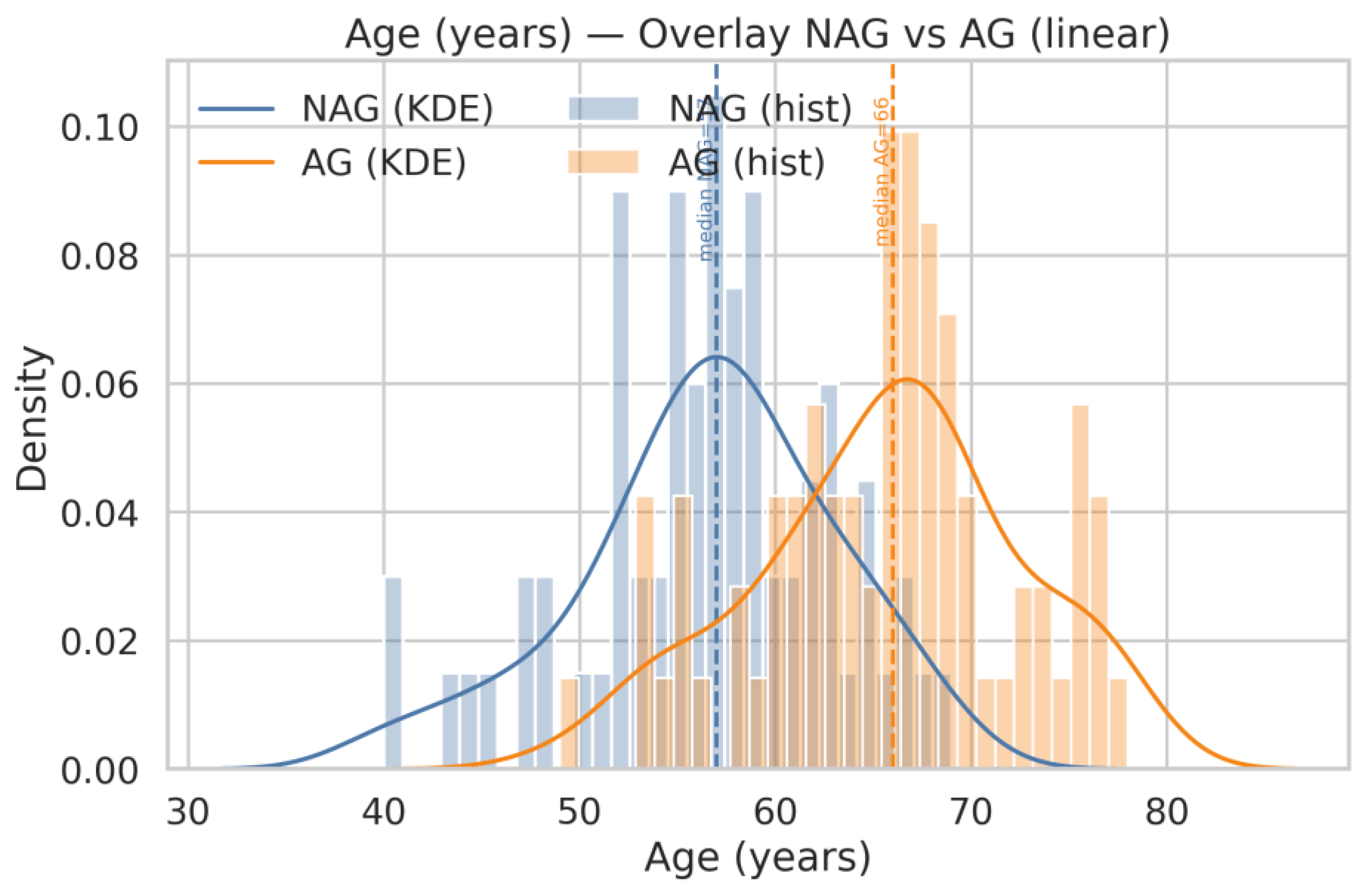

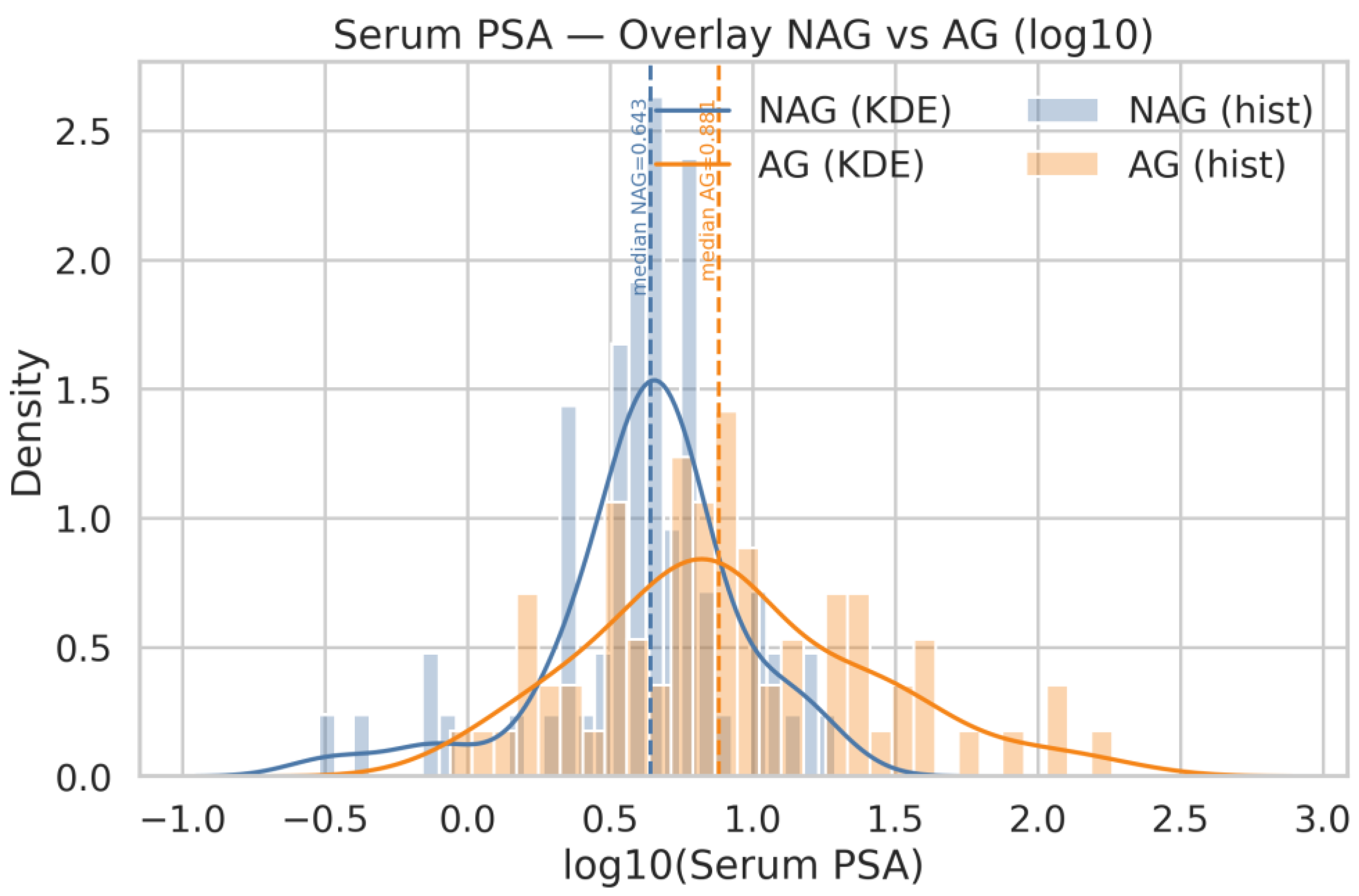

| Q19 | Show same for CLU_EDALN*ETR |

| Q20 | Show the same for age and Serum PSA |

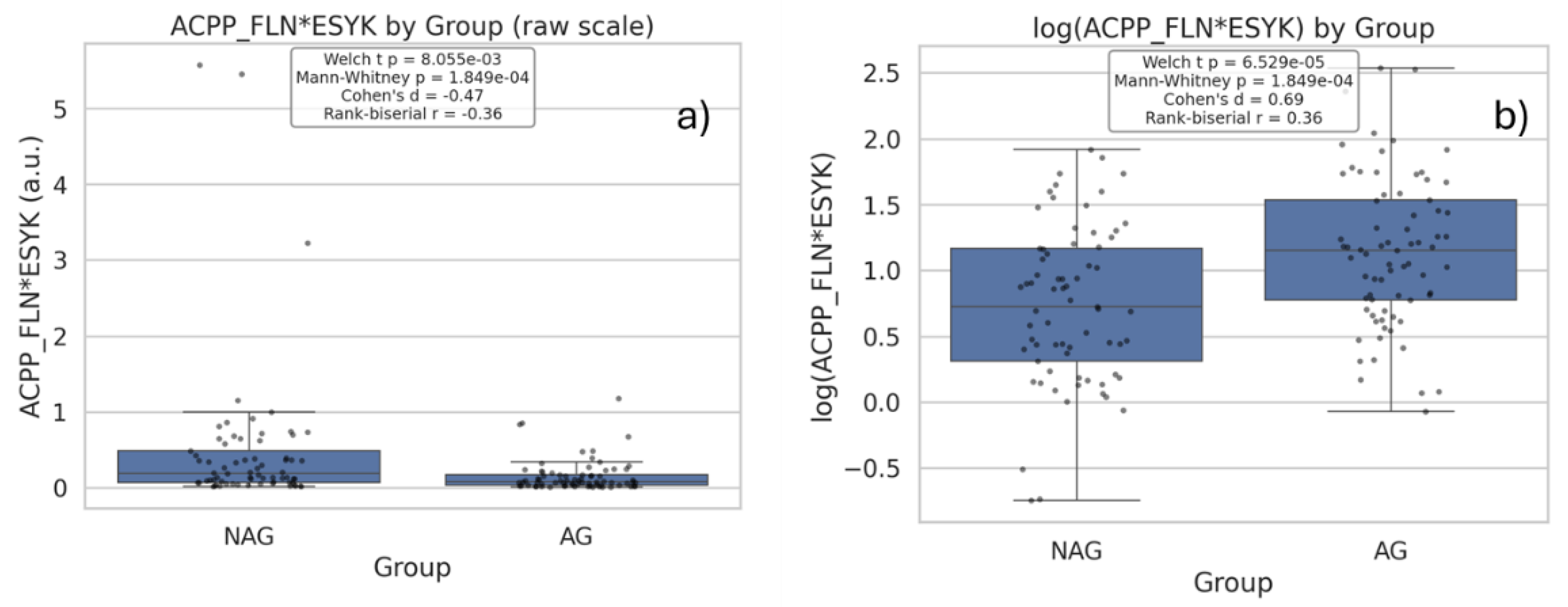

| Q21 | Compare the expression levels of the glycopeptide ACPP_FLN*ESYK between aggressive (AG) and nonaggressive (NAG) prostate cancer groups using box plots. |

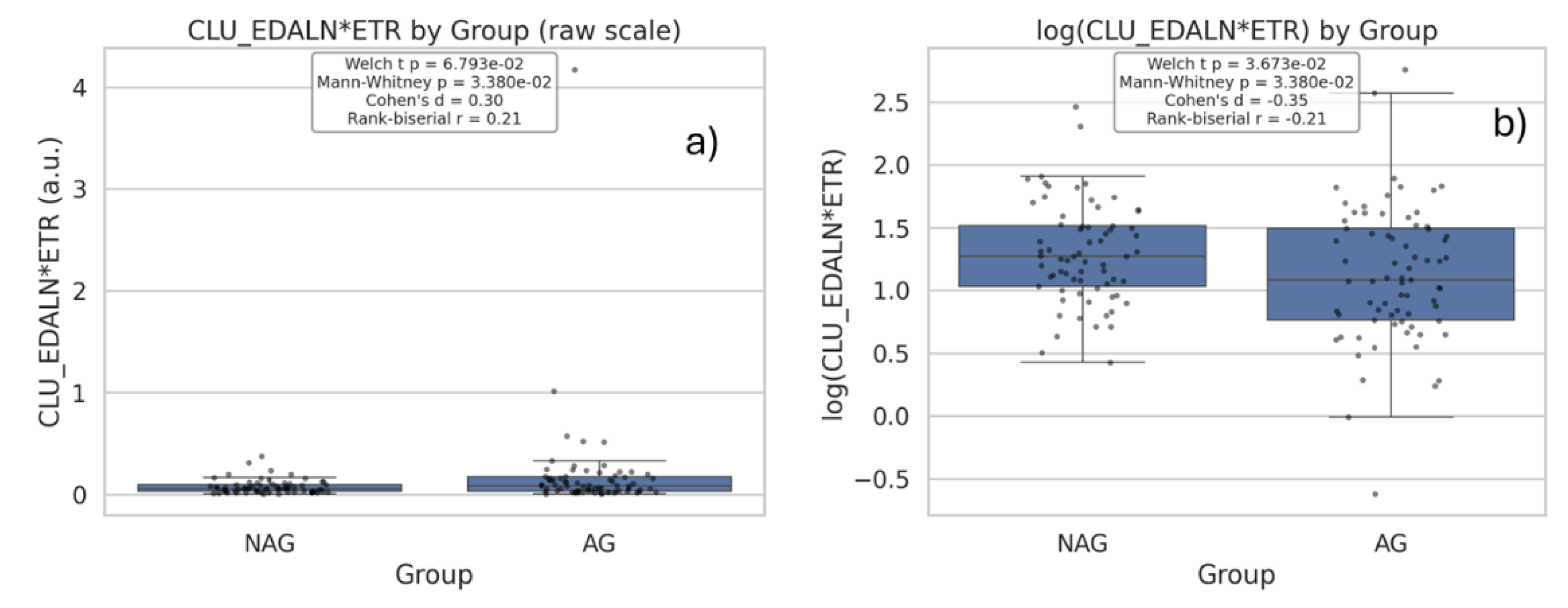

| Q22 | Compare the expression levels of the glycopeptide CLU_EDALN*ETR between aggressive (AG) and nonaggressive (NAG) prostate cancer groups using box plots |

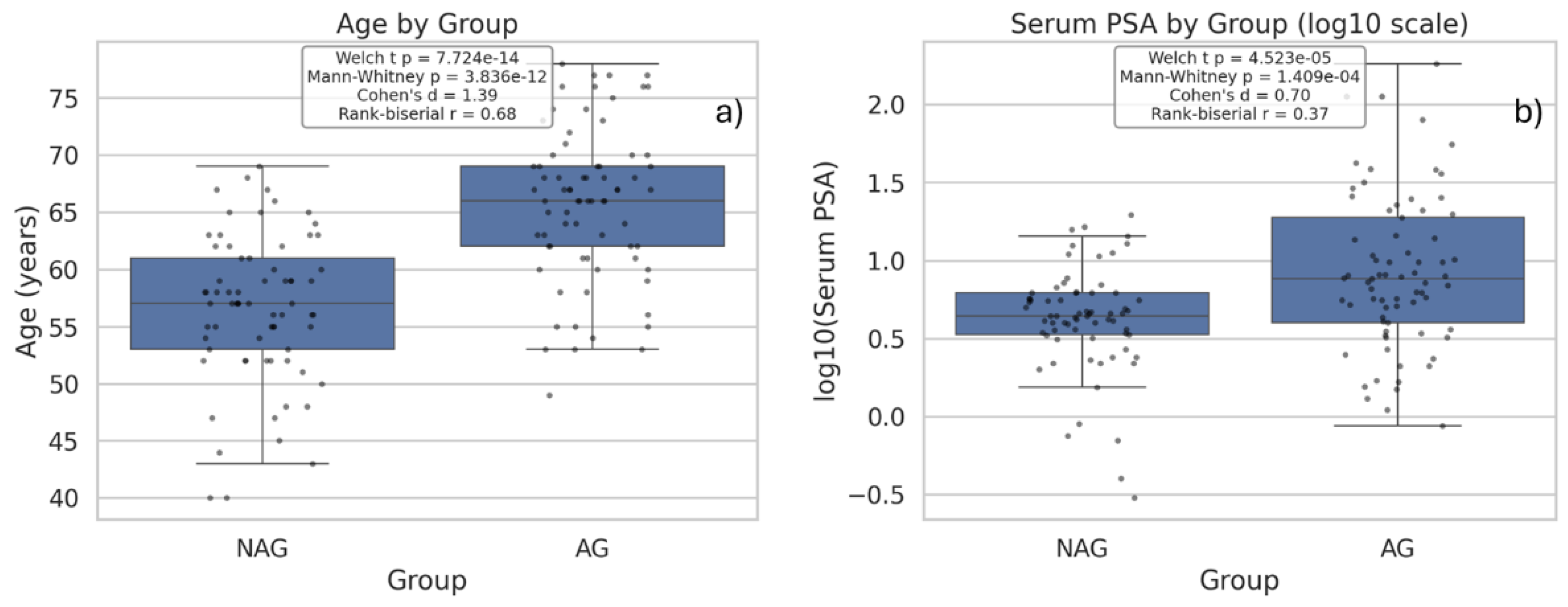

| Q23 | Compare age and serum PSA between aggressive (AG) and nonaggressive (NAG) prostate cancer groups using box plots |

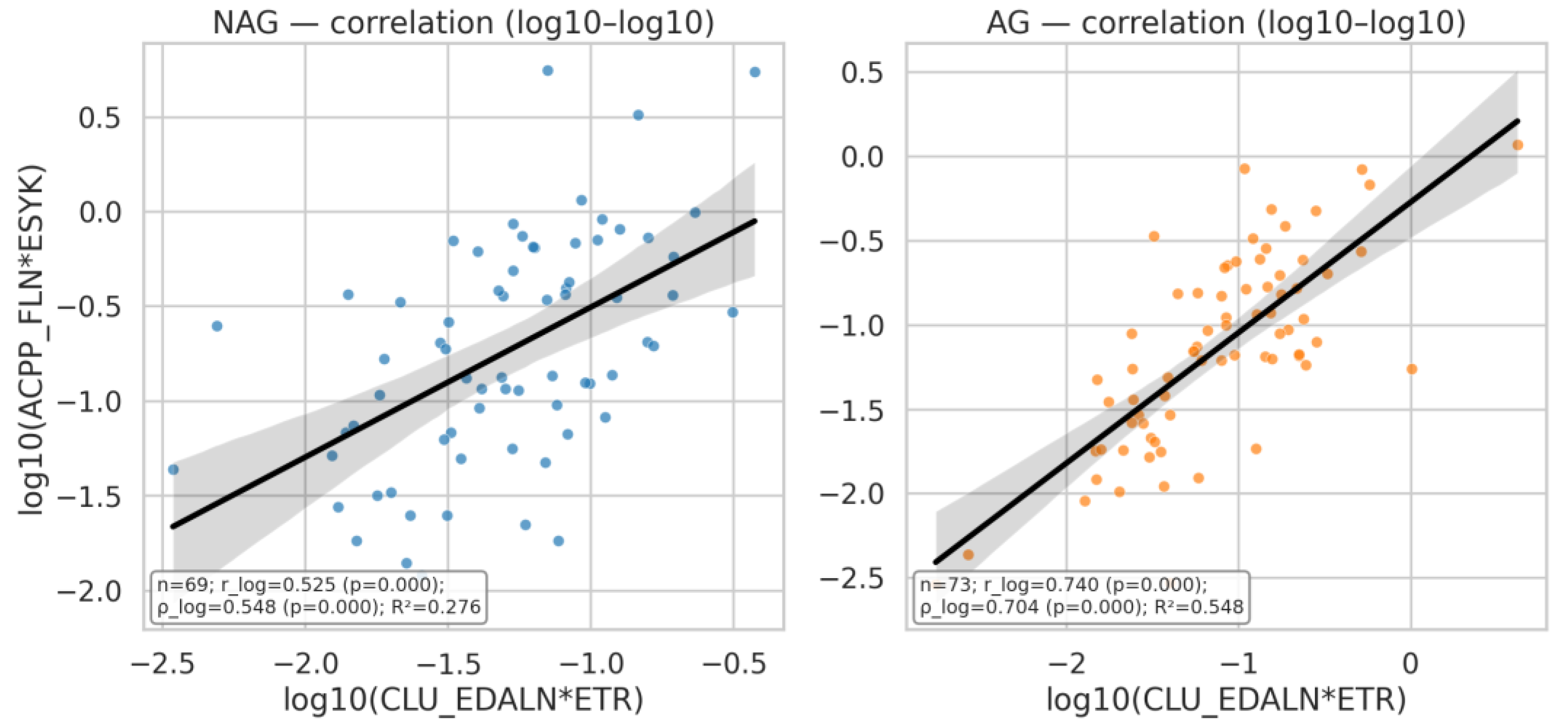

| Q24 | Build a correlation plot of ACPP_FLN*ESYK (y-axis) vs CLU_EDALN*ETR (x-axis), with the data split by AG and NAG groups |

| Q25 | : Build a correlation plot of age vs ACPP_FLN*ESYK (y-axis) and CLU_EDALN*ETR (x-axis), with the data split by AG and NAG groups |

| Upload Spreadsheet 2 | |

| Q26 | Generate a score plot showing the distribution of different physicochemical properties (e.g., atomic radius, electronegativity, ionization energy) for the elements in the periodic table. |

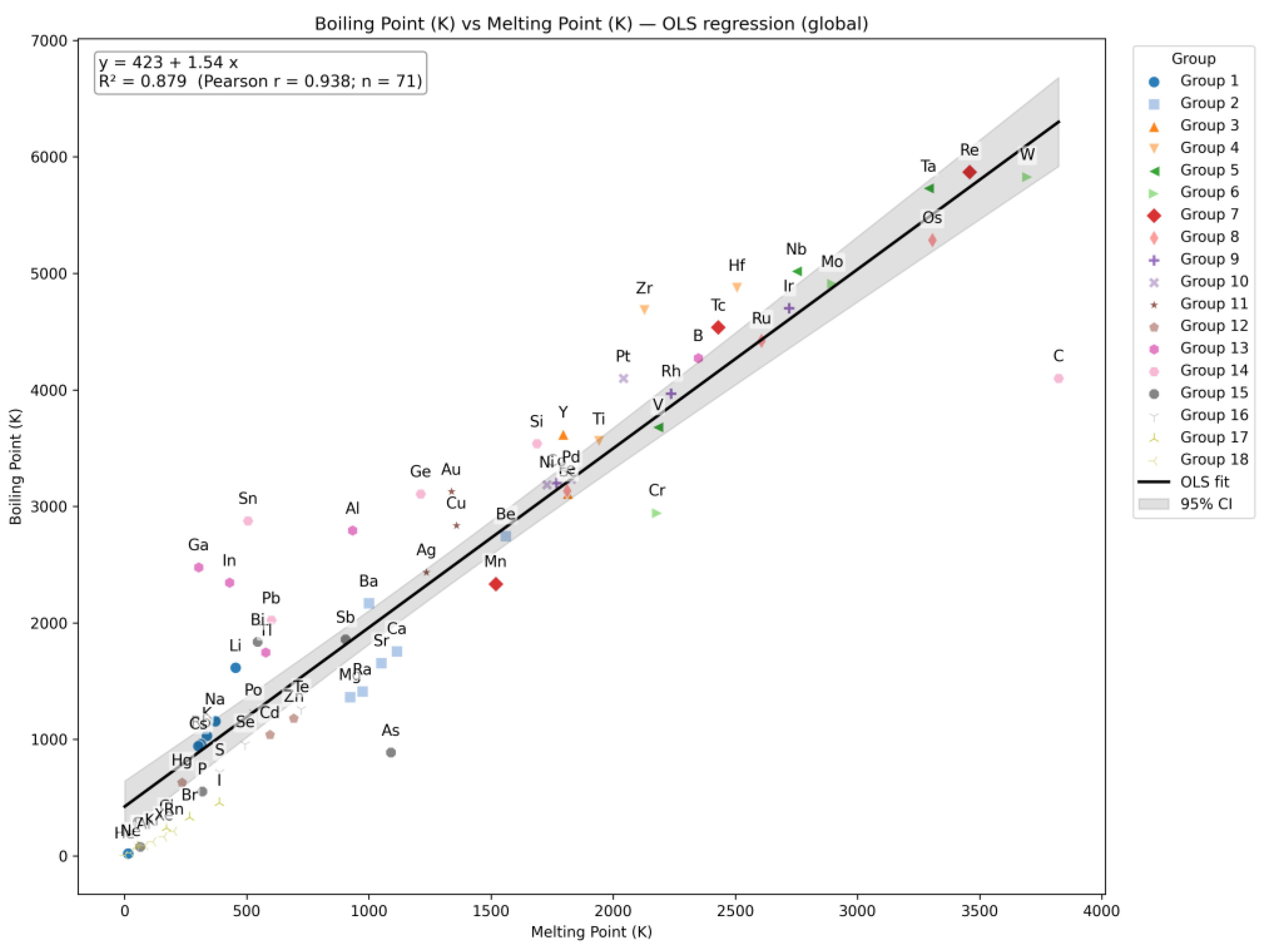

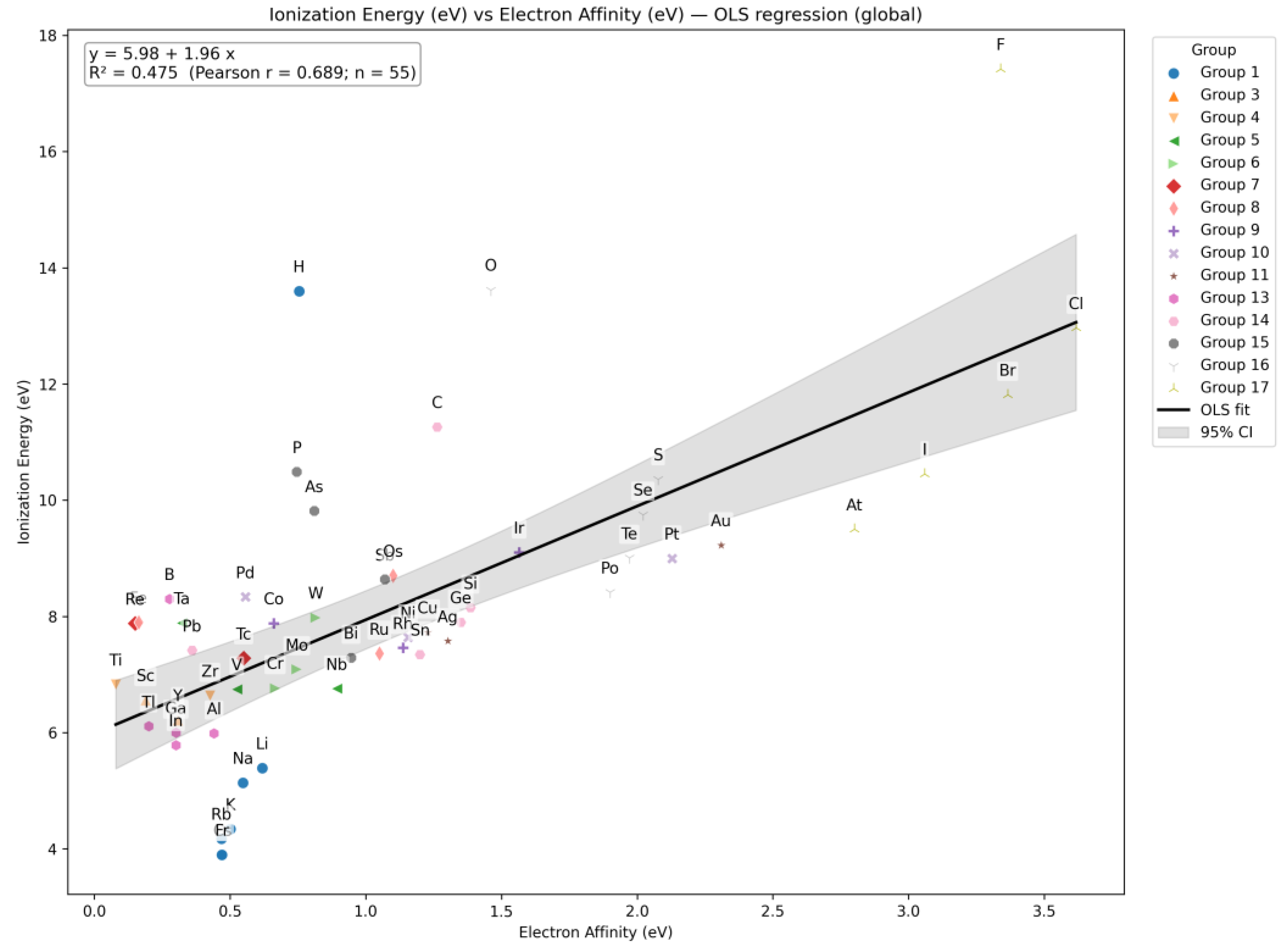

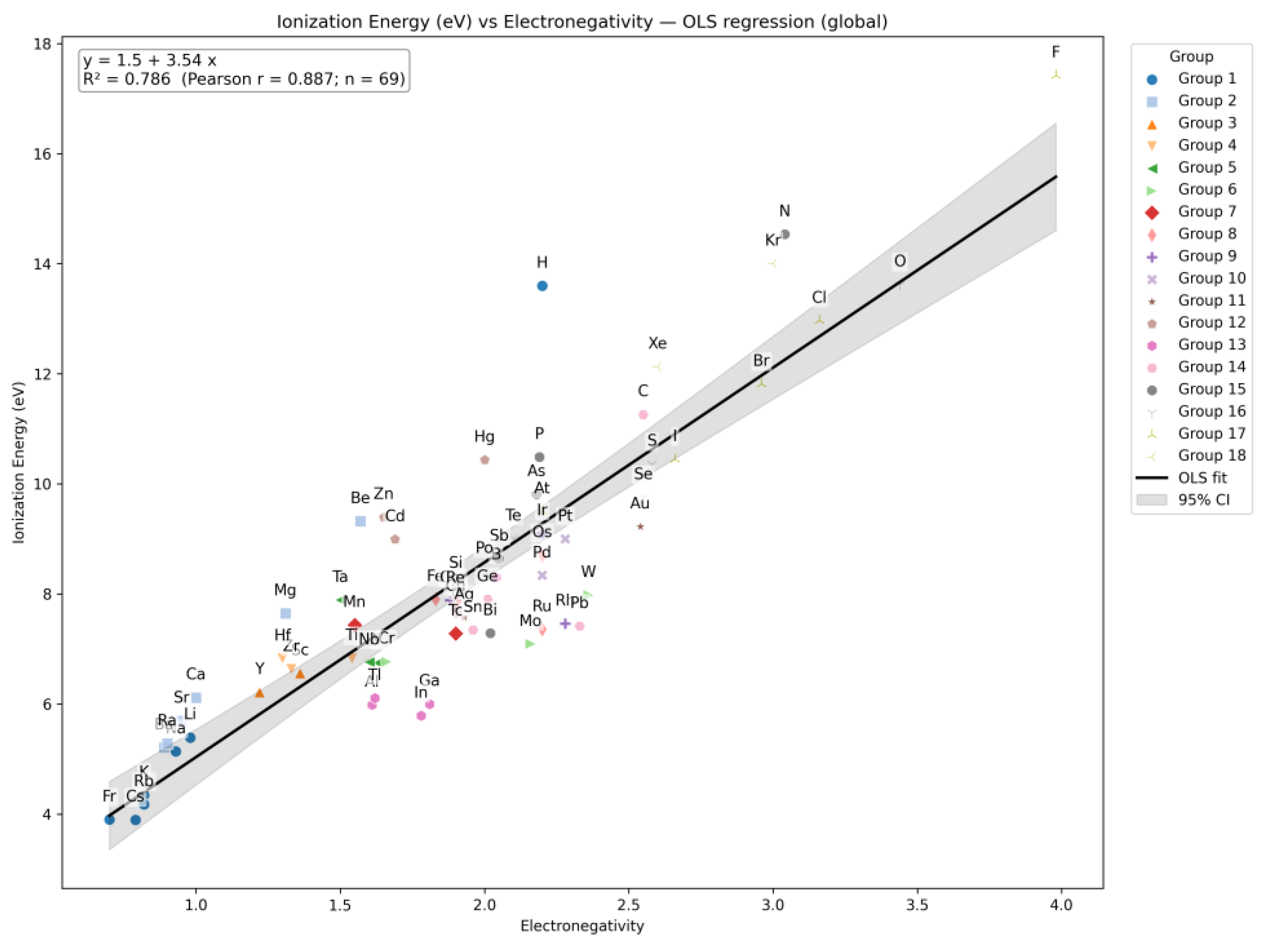

| Q27 | Generate a PCA loading plot to display the relationship between variables and principal components, highlighting their contributions and directions |

| Q28 | Create a Pearson correlation heatmap showing the relationships between the physicochemical properties of the elements in the periodic table |

| Q29 | Construct a correlation plot comparing the Boiling Point and Melting Point of elements. |

| Q30 | Construct a correlation plot comparing Ionization Energy and Electron Affinity of elements |

| Q31 | Construct a correlation plot comparing Ionization Energy and Electronegativity of elements. |

| Q32 | Does a comparison of physicochemical properties among groups (Column E; metals, nonmetals, and metalloids) using box plot, show all the box plots in the same image |

| Species | Initial (moles) | Change (moles) | Equilibrium (moles) |

| CH3COOH | 2 | -x | 2 - x |

| CH3CH2OH | 3 | -x | 3 - x |

| CH3COOCH2CH3 | 0 | +x | x |

| H2O | 8 | +x | 8 + x |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).