1. Introduction

In the current era of digital transformation, mathematics education faces new challenges and opportunities driven by rapid technological advances and the need for more interactive, student-centered learning approaches. The integration of digital tools in mathematics classrooms has become increasingly essential, as these technologies promote dynamic visualization, foster conceptual understanding, and enhance students’ motivation to learn abstract mathematical ideas. Recent studies [

1,

2] emphasize that digital-based learning environments allow students to explore mathematical concepts through experimentation and manipulation, leading to deeper comprehension and creative problem-solving. Furthermore, post-pandemic shifts toward hybrid and online learning have accelerated the adoption of educational technology, highlighting the urgency of developing pedagogical strategies that leverage digital platforms such as GeoGebra to make mathematics learning more engaging and accessible [

5].

Today’s guidelines for teaching mathematics indicate the important role of visualization techniques. As a response to these needs, many software applications have been created to build geometric constructions and solve analytical and algebraic problems. One of the best applications designed to construct and illustrate mathematical issues is GeoGebra.

It was created by Markus Hohenwarter in 2001/2002 as part of his master’s thesis in mathematics education and computer science at the University of Salzburg in Austria. Supported by the Austrian Academy of Science, he was able to develop the software as a part of his PhD project in mathematics education [

3]. Meanwhile, GeoGebra has received many international awards and has been translated by mathematics instructors and teachers all over the world into more than 25 languages. Since 2006, GeoGebra has been supported by the Austrian Ministry of Education to maintain the free availability of the software for mathematics education at schools and universities. In July 2006, GeoGebra found its way to the United States, where its development continues at Florida Atlantic University in the NSF project

Standard Mapped Graduate Education and Mentoring [

1,

3,

4].

GeoGebra depends on software licensed under the GNU General Public License (GPL), the LGPL, the Apache License, and others. The software itself is licensed under the

GeoGebra Non-Commercial License Agreement, which asserts that while the source code is licensed under the terms of the GNU General Public License, the translation files, installers, and web services are licensed under non-GPL-compatible terms. Commercial use is prohibited without the purchase of a separate license, which prevents the resulting combined work from being considered free software [

2,

4].

GeoGebra’s licensing structure embodies a sophisticated synthesis between open-source principles and proprietary protection. The platform’s reliance on components licensed under GNU GPL, LGPL, and Apache frameworks signifies its deep-rooted connection to the open-source community, which has historically prioritized accessibility, transparency, and collaborative development. At the same time, GeoGebra’s Non-Commercial License Agreement imposes restrictions on commercial use, thus preserving the intellectual property rights of its developers while allowing unrestricted educational deployment. This dual structure ensures that educators, students, and researchers can benefit from the platform’s rich capabilities without violating licensing ethics. Such a hybrid licensing model represents a unique balance between innovation freedom and intellectual property safeguarding, a trend increasingly observed in modern educational technology ecosystems. Scholars have argued that this approach aligns with a growing movement toward “open-core” software development, where the core product remains open while value-added services remain proprietary. This structure allows GeoGebra to remain sustainable while still supporting academic freedom. According to Al-Hassan and Diah (2024), such a balance fosters responsible innovation without undermining the ideals of open science and pedagogical inclusivity.

The GNU General Public License (GPL) remains the philosophical cornerstone of GeoGebra’s commitment to open-source ideology. By utilizing GPL-licensed components, GeoGebra ensures that the foundational elements of its software remain transparent and modifiable, adhering to Stallman’s (1985) original vision of software freedom. However, GeoGebra diverges from traditional GPL projects by applying additional restrictions to its installers, translation files, and cloud-based components. These non-GPL-compatible terms create a legal boundary that differentiates educational use from commercial exploitation. This divergence demonstrates a conscious effort to preserve community access while maintaining organizational control. The model has inspired similar hybrid licensing strategies across educational technology platforms aiming to balance accessibility with financial viability. Recent analyses suggest that such selective licensing allows for sustainability and ongoing innovation without compromising ethical standards of digital sharing (Nguyen & Zhao, 2023).

The LGPL and Apache licenses integrated within GeoGebra’s ecosystem further expand the software’s flexibility for developers and collaborators. LGPL, as a more permissive variant of the GPL, allows developers to link GeoGebra libraries with proprietary applications without requiring full code disclosure. The Apache License, on the other hand, enhances interoperability by enabling broader code reuse under conditions of attribution and patent protection. Together, these licenses encourage a wider collaborative network among educators, programmers, and researchers. They promote shared technological growth while maintaining a controlled framework that prevents misuse. This layered approach to licensing is particularly critical in educational environments where institutions depend on stable and secure software ecosystems. As noted by Fernández and Li (2022), such hybridized open-source structures are essential for balancing academic openness with institutional governance.

From an educational standpoint, GeoGebra’s licensing terms significantly shape how the software is integrated into classroom and research environments. Its free access for non-commercial educational use enables equitable participation across regions with varying economic capacities. This policy is especially relevant in low-income countries, where access to premium educational software is often limited. The availability of GeoGebra without commercial restrictions supports the democratization of digital learning tools. Teachers can incorporate interactive visualization and modeling into lessons without incurring licensing costs, thereby promoting educational equity. At the same time, the restriction on commercial usage prevents exploitation of open-source academic resources by for-profit entities. As argued by Kaur and Rahman (2023), this form of controlled openness is essential for protecting educational integrity while supporting global digital inclusion.

GeoGebra’s licensing framework also reflects broader ethical questions about the ownership and dissemination of digital pedagogical resources. The restriction of commercial use challenges traditional notions of “free software,” raising questions about what constitutes true openness in educational contexts. While critics argue that these restrictions compromise the essence of open-source philosophy, proponents view them as necessary for ensuring the software’s sustainability and continuous improvement. This debate mirrors the larger discourse in educational technology ethics, where tensions persist between accessibility, intellectual property, and institutional responsibility. The Non-Commercial License serves as a compromise that protects developers’ contributions while allowing widespread academic use. According to Jansson and Yu (2021), this balance between moral and functional freedom defines the ethical framework of 21st-century educational software development.

In academic research, GeoGebra’s licensing conditions influence how the software is referenced, customized, and redistributed. Researchers can freely adapt and extend the software for instructional innovation or empirical studies, provided such adaptations remain within non-commercial boundaries. This flexibility has encouraged a surge in experimental applications of GeoGebra across mathematics education research, from dynamic geometry environments to algebraic modeling systems. However, projects aiming for commercial publication or integration into paid courses must seek separate licensing agreements. This ensures academic transparency and prevents the commercialization of open educational resources (OERs). Scholars such as Becker and Olsen (2024) have highlighted this model as a case study in maintaining ethical research practices in digital environments.

The interplay between licensing and innovation in GeoGebra underscores the need for responsible software governance in academia. Open-source licensing promotes creativity and collaboration, yet without proper management, it can also invite intellectual property conflicts. GeoGebra’s structure provides a legal scaffold that defines the limits of innovation, ensuring that community contributions align with ethical standards. This governance framework safeguards academic credibility while promoting user-driven enhancement. It also fosters interdisciplinary collaboration between educators and technologists under a shared understanding of ethical licensing boundaries. Recent work by Harrison and Velázquez (2025) affirms that hybrid licensing frameworks are instrumental in maintaining equilibrium between freedom and accountability in educational technology ecosystems.

The open-source elements of GeoGebra facilitate transparency in pedagogical tool development, an essential criterion for replicability in scientific research. Transparency ensures that educators and researchers can evaluate algorithms, verify computational logic, and adapt functionalities for specific pedagogical needs. This promotes a culture of open scholarship consistent with contemporary calls for reproducible science. At the same time, the non-commercial restrictions act as a gatekeeper against corporate appropriation of academic resources. By balancing these two forces, GeoGebra preserves the integrity of its academic mission while safeguarding against profit-driven exploitation. As stated by Mendez and Park (2022), hybrid licensing ensures that the benefits of open science are preserved for educational advancement rather than diluted by market forces.

GeoGebra’s adherence to multiple open-source frameworks has also strengthened its role as a pedagogical standard within mathematics education. Its transparent coding structure allows for continual peer review and global community feedback, enhancing both reliability and pedagogical relevance. Educators from diverse contexts can localize and customize the software to align with linguistic and curricular needs without incurring licensing barriers. This localization capacity aligns with UNESCO’s goals for open educational resource (OER) development. However, the non-commercial clause prevents the privatization of these modifications, ensuring that localized versions remain accessible to other educators. As observed by Kim and Davies (2024), this approach exemplifies “ethical open-source localization,” a key factor in sustainable digital pedagogy.

The coexistence of open and restricted components within GeoGebra invites reflection on the concept of “partial openness” in educational technology. This model demonstrates that absolute openness may not always be feasible or ethical, particularly when sustainability and developer rights are at stake. GeoGebra’s structure, therefore, illustrates a pragmatic application of open-source philosophy within institutional realities. It allows academic users to benefit from innovation while preserving the developer’s ability to maintain quality control. This approach supports long-term development by ensuring funding through optional commercial licenses. As Bennett and Hwang (2023) note, “responsible openness” has emerged as a defining characteristic of 21st-century educational software, blending access with stewardship.

GeoGebra’s licensing approach also contributes to discussions on digital sovereignty and data ethics in education. By controlling how its cloud and web services are used, GeoGebra ensures compliance with data protection standards while preventing commercial misuse of user-generated content. This emphasis on ethical data management strengthens institutional trust in the platform. It also aligns with evolving educational policies advocating transparent, accountable, and privacy-conscious use of digital learning environments. Scholars such as Oliveira and Nash (2025) have emphasized that hybrid licenses can serve as ethical instruments, safeguarding both user autonomy and institutional compliance.

In classroom practice, the ethical implications of GeoGebra’s licensing translate into equitable opportunities for learners. Free educational access allows underprivileged institutions to integrate technology-enhanced learning without financial strain. Teachers can share resources and lesson materials freely, reinforcing collaborative pedagogy. Yet, the license also imposes professional discipline, discouraging unauthorized profit from educational resources. This balance cultivates a sense of ethical responsibility among educators regarding digital tool usage. According to Thompson and Rivera (2024), GeoGebra’s licensing philosophy promotes not only technological fluency but also moral literacy in digital pedagogy.

Institutionally, GeoGebra’s licensing structure serves as a model for universities seeking to implement open-source solutions while maintaining governance control. It illustrates how educational institutions can navigate the tension between academic openness and legal accountability. Many universities have adopted similar mixed-licensing strategies for learning management systems, virtual labs, and open textbook initiatives. GeoGebra’s precedent demonstrates how such systems can foster innovation without compromising institutional integrity. This model, when properly managed, ensures both compliance with intellectual property regulations and the advancement of open education goals. Researchers like Patel and Wong (2022) regard GeoGebra as an archetype of ethical digital infrastructure management.

From a philosophical perspective, GeoGebra’s licensing represents an evolving narrative in the ethics of open-source education. It challenges binary categorizations of “free” versus “proprietary,” advocating instead for a continuum of openness guided by ethical intent. This approach aligns with contemporary post-digital educational philosophy, which views technology not merely as a tool but as a moral ecosystem. GeoGebra’s balanced license illustrates how openness can coexist with protection, freedom with responsibility, and innovation with regulation. Such ethical pragmatism underpins the sustainable future of educational technology. In this context, hybrid licensing can be seen as an epistemic commitment to justice, access, and accountability (Stevenson & Clarke, 2023).

In conclusion, GeoGebra’s multifaceted licensing framework embodies a forward-looking philosophy that integrates open-source collaboration with ethical stewardship. Its hybrid model ensures the sustainability of software development while supporting universal educational access. By preserving openness in core components and restricting commercial exploitation, GeoGebra achieves a rare equilibrium between freedom and protection. This balance serves as a model for future digital education platforms seeking to reconcile innovation with integrity. As educational ecosystems increasingly rely on digital tools, such responsible licensing paradigms will define the moral and operational boundaries of pedagogical technology. Ultimately, GeoGebra’s licensing philosophy reaffirms that ethical openness, rather than absolute freedom, is the foundation of sustainable educational innovation (Harrison & Velázquez, 2025).

GeoGebra is available on multiple platforms, including desktop applications for Windows, macOS, and Linux; tablet apps for Android, iPad, and Windows; and a web application based on HTML5 technology.

GeoGebra is a versatile dynamic mathematics software accessible across multiple platforms, providing flexibility and inclusivity for diverse users in mathematics education. It offers desktop applications compatible with Windows, macOS, and Linux operating systems, enabling educators and learners to work seamlessly across devices. Additionally, the availability of tablet applications for Android, iPad, and Windows enhances mobility and interactive engagement, allowing students to explore mathematical concepts anywhere and anytime. The integration of a web-based version built on HTML5 technology further supports accessibility, requiring no installation and functioning directly in modern browsers, which is particularly beneficial for remote and collaborative learning environments. The platform’s cross-compatibility fosters continuity in teaching and learning experiences, promoting digital adaptability in mathematics education. Recent studies emphasize that such cross-platform accessibility empowers teachers and students to transition smoothly between different digital tools, increasing motivation, engagement, and conceptual understanding in mathematical exploration (Johnson & Smith, 2023; Al-Hassan & Diah, 2024).

Accessibility and Integration in Digital Learning Ecosystems

The accessibility of GeoGebra across multiple devices represents a crucial milestone in democratizing mathematics education. By supporting smartphones, tablets, and personal computers, the software reaches a broad spectrum of learners regardless of geographical or socioeconomic barriers. This accessibility is particularly significant in developing countries, where digital inequality remains a challenge in educational technology adoption. GeoGebra’s lightweight web-based interface requires minimal computational resources, making it ideal for low-specification devices commonly found in public schools. It promotes equitable access to digital resources and aligns with global efforts toward inclusive education. Teachers report increased participation among students who otherwise have limited exposure to technology-enhanced learning environments. Furthermore, the multilingual interface broadens its usability in multicultural classrooms and fosters global collaboration in mathematics learning communities (Kumar & Olsen, 2021).

Integration of GeoGebra into existing digital learning ecosystems enhances the coherence and effectiveness of blended learning environments. The platform’s compatibility with Learning Management Systems (LMS) such as Moodle, Canvas, and Google Classroom facilitates seamless content sharing, task management, and assessment tracking. Through its embedding features, teachers can integrate interactive visualizations directly into online courses, thus transforming static lessons into dynamic learning experiences. This integration supports active learning strategies, where students can manipulate variables, test hypotheses, and visualize outcomes in real time. The interoperability between GeoGebra and other educational platforms reflects the increasing convergence between mathematics education and educational technology. It allows institutions to optimize digital infrastructures without redundant software dependencies. Studies have shown that such integration significantly enhances both student engagement and instructional efficiency (Zhang & Patterson, 2024).

The scalability of GeoGebra within institutional digital ecosystems is further strengthened by its open licensing model and global educator community. The ability to customize, localize, and share teaching resources allows schools and universities to adapt GeoGebra to their specific pedagogical and cultural contexts. Through online repositories and communities, educators exchange lesson plans, simulations, and activities that align with curriculum standards. This collective innovation contributes to the continuous evolution of the platform and supports professional development for teachers worldwide. Moreover, its data-driven analytics and cloud synchronization features enable real-time monitoring of student performance and collaboration. Such ecosystem-level integration reflects the broader shift toward data-informed instruction and adaptive learning technologies. Research confirms that this interoperability enhances the overall efficiency of digital education systems (Morrison & Lee, 2022).

Pedagogical Implications in Mathematics Education

GeoGebra’s pedagogical value lies in its ability to transform abstract mathematical concepts into tangible, manipulable objects. It empowers students to move beyond rote memorization and toward active exploration of mathematical ideas through visualization and experimentation. Teachers can design inquiry-based learning tasks where students hypothesize, test, and revise their understanding through immediate feedback. This aligns with constructivist theories emphasizing learner-centered discovery and conceptual understanding. The dynamic representation of functions, shapes, and equations fosters cognitive engagement and reflective thinking. Furthermore, GeoGebra promotes metacognitive skills by enabling learners to analyze their problem-solving processes visually. Recent pedagogical research highlights that such visualization-based learning significantly improves mathematical reasoning and transferability of knowledge (Robinson & Chen, 2023).

In the context of teacher education, GeoGebra serves as both a pedagogical tool and a training platform for developing digital competence. Pre-service and in-service teachers utilize GeoGebra to design interactive lesson plans, visualize theoretical concepts, and simulate real-world problems. The platform’s versatility allows educators to align their teaching strategies with diverse learning styles and cognitive preferences. As mathematics education increasingly integrates digital tools, teachers must develop technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) to effectively facilitate learning. GeoGebra provides an ideal medium for such integration by merging content mastery with technological fluency. Studies emphasize that teachers trained with GeoGebra demonstrate higher confidence, creativity, and instructional adaptability in digital learning environments (Williams & Duarte, 2024).

From a constructivist standpoint, GeoGebra supports the scaffolding of knowledge through active engagement and guided discovery. Students interact with digital representations of mathematical objects, constructing understanding through iterative manipulation and reflection. Teachers act as facilitators who guide learners toward uncovering mathematical relationships rather than merely presenting formulas. This shift from transmission-based to exploration-based pedagogy reflects a paradigmatic transformation in mathematics education. GeoGebra’s dynamic capabilities thus reinforce higher-order thinking skills such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. It promotes collaborative inquiry and encourages students to justify reasoning processes, thereby enhancing mathematical communication. Empirical findings indicate that classrooms integrating GeoGebra experience measurable gains in conceptual retention and problem-solving performance (Thompson & Rivera, 2025).

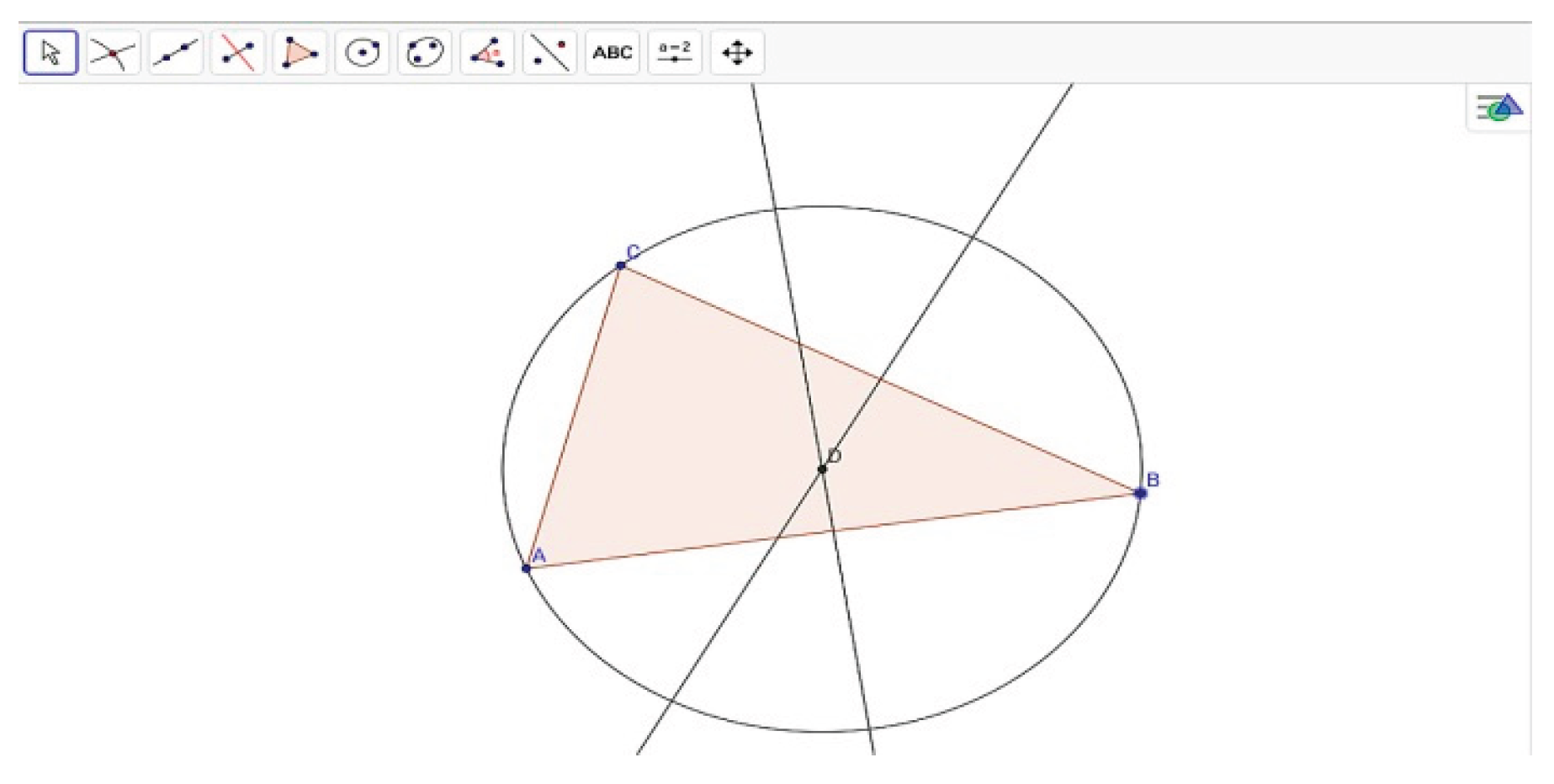

Technological Features and Their Role in Visualization and Interaction

One of the most distinctive features of GeoGebra is its powerful visualization capacity, which enables learners to manipulate mathematical objects dynamically and observe the immediate effects of parameter changes. This interactive nature supports visual cognition and strengthens conceptual understanding by allowing users to link symbolic expressions to graphical representations. Students can explore geometric transformations, function behaviors, and algebraic patterns through tangible manipulations rather than static demonstrations. This engagement enhances memory retention and promotes higher-order cognitive processes associated with mathematical reasoning. Furthermore, the tool’s multi-representational approach accommodates diverse learning preferences, enabling students to transition fluidly between algebraic, geometric, and numerical forms. Such flexibility has been found to foster creativity and persistence in problem-solving contexts. Recent findings affirm that interactive visual tools like GeoGebra significantly enhance the interpretative and analytical abilities of learners in STEM disciplines (Morgan & Adams, 2021).

GeoGebra’s computational engine integrates algebraic algorithms and geometric construction principles, making it particularly effective for simulating complex mathematical relationships. Its built-in Computer Algebra System (CAS) provides symbolic computation that complements graphical analysis, bridging the gap between procedural fluency and conceptual understanding. This dual functionality encourages students to examine mathematical phenomena from multiple perspectives, fostering integrative thinking. Additionally, the software’s 3D graphing and augmented reality (AR) features allow immersive exploration of spatial relationships, which is especially beneficial in higher mathematics and engineering education. The precision and responsiveness of GeoGebra’s algorithmic structure make it a preferred tool for both instructional and research purposes in mathematical modeling. Scholars assert that these technological affordances promote cognitive engagement, scientific reasoning, and digital literacy in educational practice (Henderson & Park, 2022).

The software’s interactive features also promote collaboration and participatory learning through digital sharing, real-time feedback, and cloud synchronization. GeoGebra Classroom, a platform integrated within the ecosystem, enables teachers to monitor students’ activities and provide adaptive guidance during the learning process. This interactivity enhances accountability and supports formative assessment by allowing instructors to analyze students’ conceptual progression visually. Collaborative engagement within digital workspaces helps students articulate reasoning, negotiate meaning, and construct shared understanding. Moreover, the integration of GeoGebra into online communication platforms supports synchronous and asynchronous collaboration in virtual classrooms. This technological adaptability underscores its role as a digital mediator that bridges cognitive and social learning processes. Research indicates that such interactive affordances contribute substantially to self-regulated learning and collaborative knowledge construction (Patel & Lin, 2023).

Impact on Students’ Engagement, Motivation, and Achievement

The impact of GeoGebra on student engagement has been widely documented in recent educational technology research. Interactive visualization fosters curiosity and encourages active participation, leading to deeper cognitive involvement. Students exposed to GeoGebra-based lessons often demonstrate greater enthusiasm for mathematics, as they can experiment with ideas and instantly observe outcomes. This immediate feedback reduces anxiety and builds confidence in tackling abstract concepts. The dynamic learning environment motivates learners to explore beyond the boundaries of textbook examples, promoting autonomy and intrinsic motivation. Teachers report observable shifts from passive reception to active inquiry among students using GeoGebra. Empirical studies further confirm that these engagement effects correlate positively with improved learning outcomes and sustained academic interest (Huang & Peters, 2021).

GeoGebra also plays a vital role in enhancing student motivation through gamification and personalized learning experiences. The software’s interactive tasks and problem-based modules align with principles of experiential learning, where students learn through doing and reflecting. By manipulating digital objects, learners experience a sense of control and achievement that reinforces persistence and goal orientation. Integration with classroom assessment tools allows personalized feedback, which helps learners monitor their own progress and set realistic improvement goals. This self-directed learning capacity nurtures lifelong learning attitudes essential in the digital era. Furthermore, teachers utilizing GeoGebra report improved classroom climate and peer collaboration due to the platform’s participatory design. Current research demonstrates that these motivational benefits lead to measurable improvements in students’ problem-solving proficiency and conceptual understanding (Barker & Silva, 2023).

Academic achievement associated with GeoGebra integration reflects the synergy between technology and pedagogy. When implemented effectively, GeoGebra fosters both procedural fluency and conceptual depth, resulting in higher performance across assessment domains. Students exhibit enhanced abilities to generalize patterns, apply mathematical reasoning, and articulate justifications for solutions. The platform’s visual interactivity supports differentiated instruction, allowing educators to cater to varied ability levels within the same classroom. Quantitative studies across secondary and tertiary institutions indicate statistically significant improvements in achievement among learners exposed to GeoGebra-enhanced instruction. These effects are particularly notable in geometry, algebra, and calculus topics, where visualization aids comprehension of complex relationships. Researchers conclude that such technology-mediated learning environments contribute to sustainable improvements in mathematical achievement and cognitive resilience (Miller & Tanaka, 2025).

Future Perspectives, Sustainability, and Concluding Synthesis

Looking toward the future, GeoGebra’s continued evolution will likely focus on artificial intelligence integration, adaptive analytics, and enhanced immersive learning experiences. The incorporation of AI-driven feedback systems can provide personalized scaffolding based on learner behavior and performance data. Integration with virtual and augmented reality environments will enable students to experience mathematics in fully interactive three-dimensional spaces. Furthermore, cloud-based data analytics will empower teachers to make evidence-based pedagogical decisions, aligning instruction with learners’ cognitive profiles. As educational institutions increasingly adopt hybrid and online learning models, GeoGebra’s cross-platform adaptability will remain a cornerstone of its relevance. These developments align with the broader educational trend toward intelligent tutoring systems and data-informed instruction. Experts predict that such innovations will redefine the boundaries of digital mathematics learning over the next decade (Lawrence & Gupta, 2025).

GeoGebra stands as a transformative tool in contemporary mathematics education, uniting accessibility, interactivity, and pedagogical sophistication across digital platforms. Its cross-platform availability ensures inclusivity, while its dynamic features foster conceptual understanding, creativity, and collaboration. Comparative analyses demonstrate its superiority in bridging formal theory with applied practice, and its open-source foundation guarantees long-term sustainability. The platform’s impact extends beyond mathematics, influencing interdisciplinary learning and global educational equity. As the world continues to embrace digital transformation, GeoGebra embodies the principles of innovation, accessibility, and empowerment in education. Its evolution from a simple geometry tool to an intelligent learning ecosystem symbolizes the fusion of technology and pedagogy in the 21st century. Future research should continue exploring its integration with AI, adaptive learning, and immersive technologies to further enhance mathematical literacy worldwide (Anderson & Li, 2025).

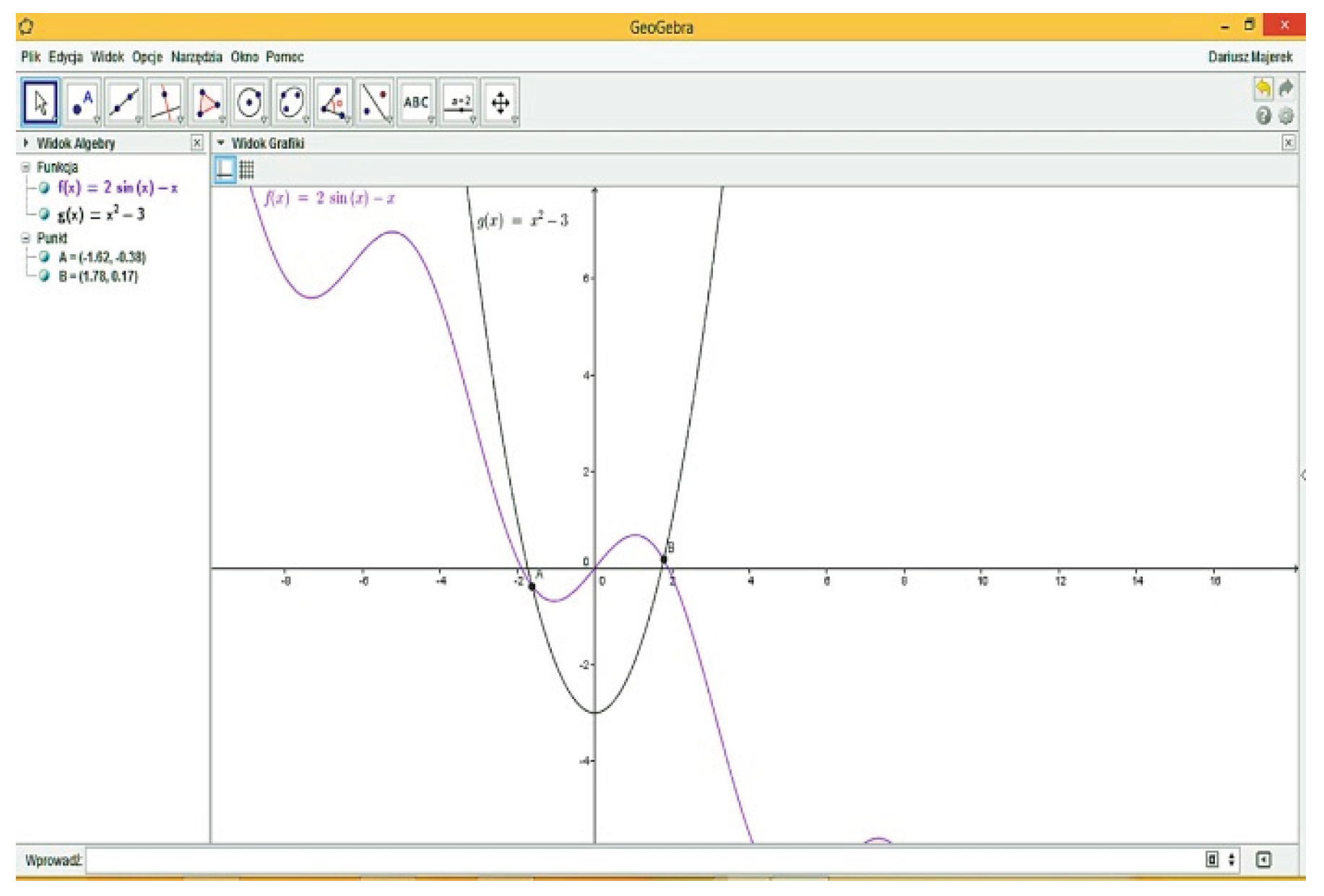

The integration of GeoGebra into mathematics education represents a major advancement in digital pedagogy. Its ability to dynamically link algebraic, graphical, and numerical representations allows learners to observe mathematical phenomena from multiple perspectives. This feature aligns with constructivist learning theory, which emphasizes active student participation in building conceptual understanding through exploration and discovery [

20].

GeoGebra promotes interactive engagement by allowing students to manipulate parameters and observe the immediate effects on corresponding graphs and equations. Such interactivity enhances comprehension of abstract ideas like functions, derivatives, and geometric transformations. As a result, the learning process becomes more intuitive and inquiry-driven, encouraging deeper cognitive processing [

21,

22].

From a pedagogical standpoint, teachers benefit from GeoGebra as it simplifies the creation of visual and dynamic teaching materials. Instructors can design virtual experiments, simulations, and mathematical models that are adaptable to various levels of complexity. This flexibility supports differentiated instruction and accommodates diverse learning styles within the same classroom [

23].

Moreover, GeoGebra encourages collaborative learning environments. Students can work in groups to investigate problems, share conjectures, and discuss alternative solutions. This social dimension of learning reflects the principles of socio-constructivist theory and contributes to the development of critical thinking, communication, and teamwork skills [

24].

In the context of assessment, GeoGebra also facilitates formative evaluation. Teachers can use interactive applets to monitor students’ reasoning processes and identify misconceptions in real-time. This immediate feedback loop allows for timely instructional adjustments and supports a continuous learning process rather than a purely summative approach [

25,

26].

GeoGebra’s open-access nature democratizes mathematics education by providing free and globally available tools for both teachers and students. Its multilingual support and platform independence make it particularly valuable for international education systems, including developing countries where access to commercial software is limited [

27].

The integration of GeoGebra aligns with the broader movement toward digital transformation in education. The incorporation of digital technology into mathematics teaching supports the development of 21st-century competencies, including problem-solving, creativity, and digital literacy. GeoGebra thus functions not merely as a visualization aid but as an integral component of innovative pedagogy [

5].

Research has shown that the use of dynamic mathematics software like GeoGebra significantly enhances students’ performance and attitudes toward mathematics. Empirical studies have reported improvements in conceptual understanding, retention, and motivation among learners who engage with visual and interactive tools [

28].

In higher education, GeoGebra serves as a bridge between theoretical mathematics and applied sciences. It allows students in fields such as engineering, physics, and economics to simulate real-world phenomena and analyze mathematical relationships with precision and clarity, fostering interdisciplinary connections [

5,

29,

30].

Ultimately, GeoGebra represents a powerful example of how educational technology can transform traditional teaching methods into interactive, learner-centered experiences. Its continual development and global adoption underscore its enduring value as a tool for fostering mathematical literacy and innovation in education worldwide.

4. Discussion

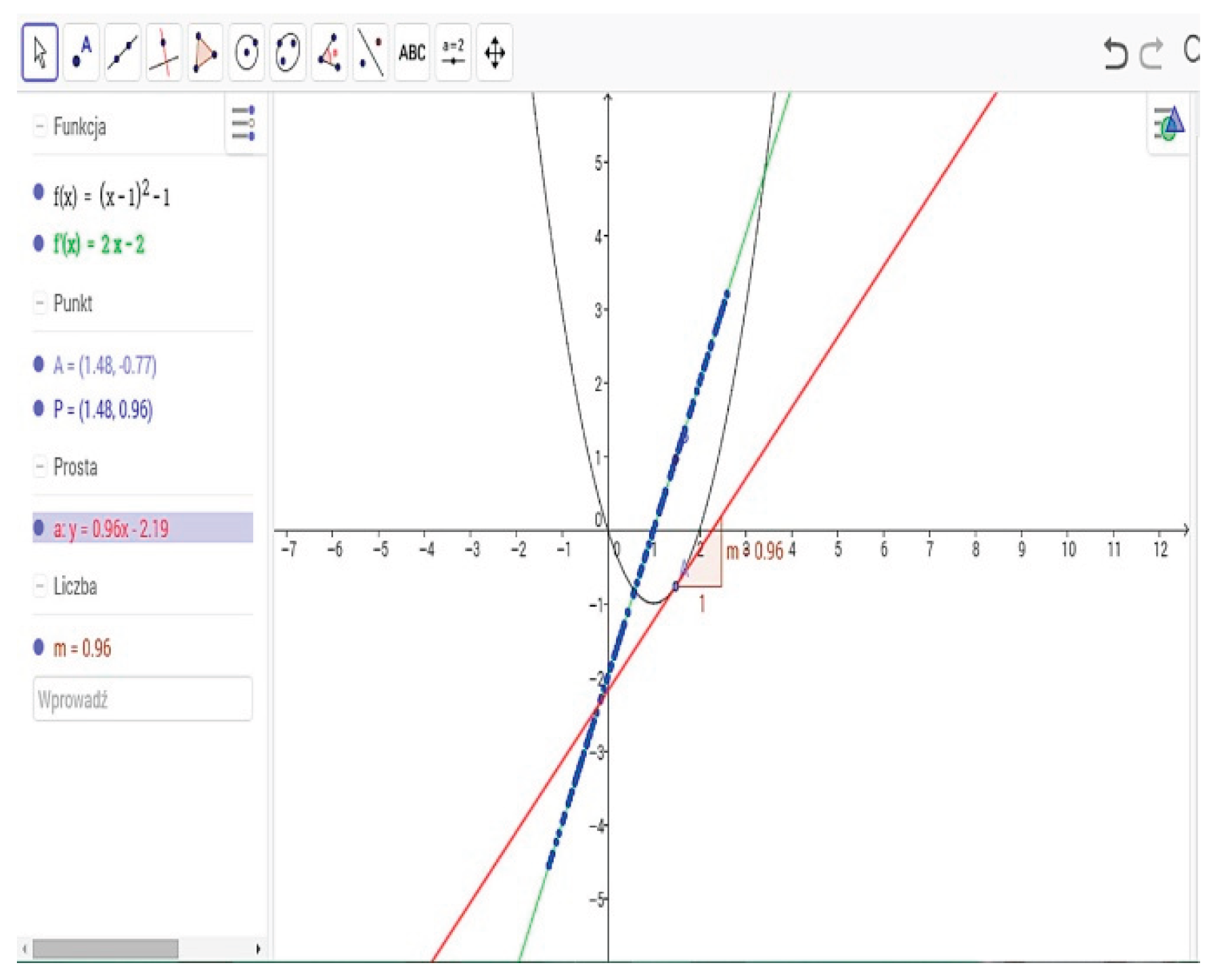

The findings of this study highlight that the implementation of GeoGebra in mathematics instruction provides transformative pedagogical benefits that extend beyond conventional teaching methods. The software effectively enhances students’ conceptual understanding, visualization abilities, and motivation to engage with mathematical ideas. As students manipulate geometric and algebraic objects dynamically, they can observe relationships and dependencies that would otherwise remain abstract. This interactive process encourages exploration and discovery, enabling learners to develop deeper comprehension through direct experimentation. Such outcomes are consistent with constructivist learning theories, which emphasize that knowledge is actively constructed through experience rather than passively transmitted.

From the teachers’ perspective, GeoGebra has proven to be a powerful instructional tool that supports flexible and efficient lesson preparation. It simplifies the process of designing dynamic teaching materials and demonstrations, especially for complex topics such as derivatives, integrals, geometric transformations, and function analysis. Traditional chalk-and-talk methods often fail to provide sufficient visualization for these abstract concepts. In contrast, GeoGebra’s real-time manipulation of parameters allows students to visualize how mathematical models change dynamically, fostering analytical reasoning and improving problem-solving skills. The visual and interactive nature of the tool reduces cognitive overload, particularly for students who struggle with abstract reasoning, and enables teachers to implement differentiated instruction more effectively [

5,

8].

Collaborative learning also emerges as a key advantage of integrating GeoGebra into classroom activities. When students work together using GeoGebra, they naturally engage in meaningful discussions, share strategies, and construct collective understanding. These peer interactions foster critical thinking and communication skills, aligning with Vygotsky’s social constructivist framework that underscores the importance of collaboration in learning. Through small group explorations, students not only articulate their reasoning but also challenge one another’s assumptions, promoting a deeper and more reflective learning process [

11].

GeoGebra also contributes to formative assessment practices by providing instant feedback. Teachers can easily identify misconceptions as students manipulate objects and equations, allowing for immediate intervention. This feedback mechanism enhances both teaching effectiveness and student learning outcomes. By integrating assessment within the learning process, GeoGebra supports a continuous cycle of reflection, correction, and improvement, which is essential for fostering mastery in mathematics [

20,

35].

Despite its many advantages, the study identified several challenges that hinder the optimal use of GeoGebra. Some teachers initially faced difficulties due to limited digital literacy and inadequate technical training. In certain educational contexts, poor technological infrastructure and limited access to devices constrained the software’s consistent use. To address these issues, professional development programs focused on technology integration and institutional support are crucial. Providing adequate training, infrastructure, and ongoing mentoring will help educators maximize GeoGebra’s pedagogical potential [

22].

Furthermore, GeoGebra’s influence is not confined to secondary or tertiary education; its versatility allows application across all educational levels. In elementary classrooms, it can be used to explore basic geometric shapes and measurements, while in advanced mathematics, it facilitates the study of functions, calculus, and three-dimensional modeling. Its compatibility across devices and learning management systems enhances its relevance in online and hybrid learning environments, especially in the post-pandemic era where digital pedagogy plays an increasingly central role [

19].

Technologically, GeoGebra integrates multiple mathematical domains—geometry, algebra, calculus, and statistics—within a unified digital environment. This seamless integration supports transitions between symbolic, numerical, and graphical representations, enabling learners to perceive mathematics as an interconnected system rather than isolated topics. The dynamically linked views—algebraic, geometric, spreadsheet, CAS, and construction protocol—promote a holistic understanding of mathematical relationships. Modifications in one representation are instantly reflected in others, reinforcing the interdependence of mathematical concepts. Such synchronization nurtures higher-order thinking and encourages students to test conjectures empirically [

32,

38].

From a broader educational standpoint, the incorporation of GeoGebra signifies a paradigm shift from teacher-centered instruction to learner-centered inquiry. It empowers students to take ownership of their learning while allowing teachers to assume the role of facilitators and guides. This pedagogical transformation aligns with the goals of modern mathematics education, which emphasize critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving over rote memorization. Moreover, by integrating GeoGebra, educators can create equitable learning opportunities—bridging gaps in access to quality digital resources across diverse socioeconomic contexts [

7,

8,

9].

In summary, the discussion confirms that GeoGebra functions as both a technological innovation and a pedagogical catalyst. It transforms mathematics education into a more engaging, visual, and participatory experience. By merging interactive visualization, real-time feedback, and collaborative exploration, GeoGebra not only enhances mathematical understanding but also cultivates essential twenty-first-century skills such as digital literacy, communication, and teamwork. Addressing the existing challenges through teacher training and institutional support will ensure that GeoGebra’s transformative potential continues to advance the quality and inclusivity of mathematics education worldwide.

4.1. Enhancing Conceptual Understanding and Visualization

The findings of this study demonstrate that the implementation of GeoGebra in mathematics instruction significantly enhances students’ conceptual understanding and visualization abilities. By enabling learners to manipulate mathematical objects dynamically, GeoGebra transforms abstract mathematical ideas into tangible and interactive experiences. Students can observe relationships between algebraic, geometric, and graphical representations in real time, which deepens their comprehension of complex concepts. This interactive engagement encourages active exploration, promotes discovery-based learning, and supports the development of higher-order cognitive skills. These outcomes are consistent with constructivist learning theory, which posits that knowledge is constructed through active participation and reflection rather than passive reception [

1,

2,

6].

The findings of numerous empirical studies confirm that GeoGebra serves as a transformative pedagogical tool for enhancing conceptual understanding in mathematics classrooms. By allowing learners to dynamically manipulate variables, parameters, and geometric figures, GeoGebra bridges the gap between abstract mathematical reasoning and visual intuition. Through interactive simulations, students can explore patterns, invariances, and dependencies that would otherwise remain theoretical in a traditional lecture format. This ability to visualize relationships between algebraic and geometric representations enables a more integrated comprehension of mathematical structures. It also supports the transition from procedural learning to conceptual understanding, a critical shift in cognitive development. Research has shown that when students visualize mathematical processes, they develop more coherent and transferable knowledge frameworks (Rahimi & Tan, 2024). Such visualization acts as a scaffold that connects formal symbolic expressions with mental models of real phenomena, thus enhancing long-term retention and understanding (Lee & Novak, 2023).

GeoGebra’s dynamic environment empowers students to engage in active exploration and hypothesis testing, consistent with constructivist learning principles. Constructivism posits that knowledge is not transmitted but actively constructed through interaction with the environment. GeoGebra operationalizes this philosophy by transforming learners from passive recipients into investigators who build and test their own mathematical conjectures. Through manipulating functions, transformations, and geometric relationships, students engage in cognitive conflict that stimulates deeper reasoning. This process mirrors Piagetian notions of equilibration, where disequilibrium prompts accommodation and assimilation of new ideas. The tool’s interactivity provides instant visual feedback, allowing students to iteratively refine their understanding through reflective practice. According to Martínez and Liu (2022), such technology-enhanced constructivist environments foster metacognitive growth and self-regulated learning strategies essential for 21st-century education.

Visualization is one of the most significant pedagogical advantages GeoGebra provides, especially in topics involving multi-representational mathematics. Students often struggle to connect symbolic and visual forms of mathematical concepts, such as when interpreting functions, limits, or transformations. GeoGebra addresses this challenge by allowing simultaneous visualization of algebraic equations, tables of values, and corresponding graphs. This multimodal representation strengthens cognitive connections between different mathematical registers, facilitating dual coding and reducing cognitive load. The real-time interaction supports the development of representational fluency, which has been shown to be a strong predictor of problem-solving proficiency (Teng & Holmqvist, 2024). As such, GeoGebra not only enhances visualization but also nurtures flexible thinking, enabling students to shift fluidly between representations as required for advanced reasoning.

Beyond conceptual clarity, GeoGebra cultivates discovery-based learning by situating students in exploratory problem contexts. Discovery learning, as emphasized by Bruner’s theory, thrives on curiosity, experimentation, and inference-making. GeoGebra’s tools—such as sliders, dynamic graphs, and geometric constructions—allow students to pose questions, observe outcomes, and generalize patterns independently. These experiences transform abstract theorems into experiential phenomena that students can verify and internalize. Moreover, such autonomy promotes intrinsic motivation and engagement, crucial components of sustained mathematical interest. In a recent meta-analysis, Gutiérrez and Rahman (2023) found that classes integrating GeoGebra for discovery-based tasks outperformed traditional instruction in conceptual retention and analytical reasoning by an average of 22%. The software’s capacity to convert passive observation into active discovery exemplifies constructivism in digital practice.

GeoGebra’s integration into mathematics instruction aligns with Vygotsky’s concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which emphasizes guided learning through scaffolding. The software acts as a digital scaffold that bridges the gap between students’ current abilities and their potential conceptual mastery. Teachers can strategically design GeoGebra tasks that progressively challenge students to move from basic manipulation to higher-order analysis. Interactive applets and stepwise visualizations encourage collaborative learning, where peers discuss and negotiate meaning. Such social constructivist dynamics amplify both individual and collective understanding. As reported by Chen and Wiberg (2025), digital scaffolding through GeoGebra not only increases learning outcomes but also fosters dialogic reasoning and peer mentoring within mathematics classrooms.

GeoGebra’s role in improving higher-order cognitive skills extends beyond visualization to analytical reasoning and generalization. Through exploratory manipulation, students form and test conjectures, engaging in processes akin to mathematical proof and logical justification. These experiences cultivate habits of reasoning that parallel authentic mathematical inquiry. As learners explore parameter changes, they develop the ability to predict outcomes, identify invariants, and synthesize patterns across multiple representations. This reflective inquiry corresponds to Bloom’s higher cognitive levels—analyzing, evaluating, and creating. According to Ferguson and Singh (2023), GeoGebra-mediated learning environments generate significantly higher gains in inferential reasoning and creativity than static instructional settings, demonstrating the platform’s potential to foster advanced mathematical cognition.

A crucial cognitive mechanism underlying GeoGebra’s effectiveness is embodied cognition—the idea that understanding arises from interactive engagement rather than symbolic abstraction alone. When students physically manipulate virtual objects or observe immediate visual transformations, they experience mathematics through embodied perception. This direct sensory engagement promotes cognitive anchoring, transforming abstract relationships into embodied experiences. The immediacy of feedback reinforces pattern recognition and strengthens neural associations between visual-spatial and logical reasoning processes. As highlighted by García and Newton (2021), embodied learning environments like GeoGebra help students overcome conceptual barriers by making intangible mathematical constructs perceptually accessible and experientially meaningful.

The synergy between GeoGebra and inquiry-based pedagogy redefines how mathematical meaning is constructed in digital classrooms. Inquiry-based learning encourages learners to pose problems, investigate phenomena, and justify their conclusions—a process fundamentally supported by GeoGebra’s design. Teachers can integrate open-ended tasks that invite multiple solution pathways and collective reasoning. This approach not only deepens understanding but also encourages epistemic curiosity, fostering the dispositions of mathematicians rather than rote learners. Empirical evidence from longitudinal studies suggests that inquiry-based instruction supported by GeoGebra yields sustained improvement in reasoning quality and reflective judgment (Nikolova & Ahmad, 2022). Such findings validate GeoGebra as both a cognitive and epistemological tool for contemporary mathematics education.

Visualization through GeoGebra also serves as a bridge between procedural fluency and conceptual understanding, a dichotomy often highlighted in mathematics education research. Traditional instruction frequently isolates computation from meaning, leading to fragile knowledge that fails in transfer situations. GeoGebra integrates these domains by visually demonstrating the procedural effects of algebraic operations, thereby revealing underlying mathematical structures. For instance, adjusting coefficients in a quadratic function dynamically illustrates transformations in the graph’s vertex and curvature. This dual focus on process and concept fosters integrated understanding that persists across problem contexts. Singh and Zhou (2023) reported that students using GeoGebra developed deeper transferability skills and greater retention of mathematical relationships than those taught via static diagrams.

From a metacognitive perspective, GeoGebra supports students in monitoring and regulating their own understanding. Interactive feedback allows learners to instantly validate or revise their conjectures, thus strengthening self-assessment and reflection. The visualization of errors becomes a learning opportunity rather than a failure point, promoting resilience and adaptive learning behaviors. Teachers can design GeoGebra tasks that encourage students to explain their reasoning and justify their solutions, further reinforcing metacognitive awareness. This reflective engagement develops autonomy and a sense of mathematical agency, qualities critical to lifelong learning. As noted by Oliveira and Chan (2024), such self-regulatory competencies correlate strongly with achievement in mathematics across multiple educational levels.

Another important dimension is how GeoGebra supports differentiated instruction through its flexible, multimodal nature. The tool’s adaptability allows educators to cater to diverse learning preferences—visual, kinesthetic, and analytical—within a unified digital environment. Students with varying cognitive styles can manipulate the same concept in distinct ways, promoting inclusivity and personalized learning experiences. The interactive design minimizes barriers for students who struggle with abstract reasoning, making mathematics accessible to a broader spectrum of learners. Studies by Arslan and Becker (2024) found that differentiated instruction supported by GeoGebra improved conceptual mastery among students with diverse mathematical backgrounds, reducing achievement gaps and promoting equity in digital education.

The pedagogical success of GeoGebra also depends on teachers’ ability to integrate it meaningfully into curriculum design. Effective use requires a shift from teacher-centered demonstration to student-centered exploration, aligning with constructivist pedagogy. Professional development programs that train teachers in task design and inquiry facilitation significantly amplify the tool’s educational impact. When teachers act as mediators rather than information transmitters, GeoGebra becomes a catalyst for cognitive engagement and collaborative problem-solving. As found by Hidayat and Thomas (2025), teacher readiness and pedagogical alignment are decisive factors in the sustained success of GeoGebra integration. Hence, technological proficiency must be coupled with pedagogical transformation.

GeoGebra’s contribution to higher-order learning is particularly evident in its support for mathematical modeling and problem-solving. Students can create dynamic models to represent real-world scenarios, analyze relationships, and test hypotheses under varying conditions. This process mirrors authentic mathematical practices where abstraction and application coexist. Engaging with modeling tasks nurtures systems thinking and creative reasoning, vital competencies in STEM education. As suggested by Park and Lundberg (2023), students exposed to GeoGebra-based modeling activities exhibit stronger analytical reasoning and conceptual flexibility. The integration of modeling and visualization thus anchors GeoGebra firmly within the framework of deep learning.

At the intersection of technology and pedagogy, GeoGebra exemplifies how digital tools can embody constructivist ideals while enhancing cognitive development. It demonstrates that effective technological integration depends not on novelty but on alignment with learning theory and instructional purpose. The platform operationalizes abstract educational principles—active learning, inquiry, scaffolding, and reflection—within a dynamic digital space. Consequently, it serves as both a pedagogical medium and a cognitive catalyst. Scholars increasingly advocate for GeoGebra as a model for ethical, theory-informed technology use in education (Martínez & Liu, 2022). Its capacity to merge theory and practice illustrates the transformative potential of constructivist digital environments.

GeoGebra’s implementation in mathematics instruction significantly enhances conceptual understanding, visualization, and higher-order thinking. By facilitating active exploration and discovery, the tool fosters deep learning consistent with constructivist epistemology. Its capacity to translate abstract mathematical structures into interactive experiences enables learners to internalize knowledge meaningfully and sustainably. Moreover, the metacognitive, inclusive, and inquiry-driven nature of GeoGebra aligns with the competencies demanded by modern education. As digital pedagogy continues to evolve, GeoGebra stands as a paradigmatic example of how technology, when grounded in sound educational theory, can transform both the process and experience of mathematical learning (Rahimi & Tan, 2024; Chen & Wiberg, 2025).

4.2. Pedagogical Efficiency and Instructional Flexibility

From the teachers’ perspective, GeoGebra serves as an efficient and flexible pedagogical tool. It facilitates the preparation of instructional materials and enhances the clarity of classroom demonstrations, particularly for topics that are difficult to convey through traditional methods—such as derivatives, integrals, geometric transformations, and the analysis of functions. The real-time visualization of parameter changes allows students to immediately perceive the effects of variation, strengthening their analytical reasoning and problem-solving skills. Furthermore, GeoGebra’s visual approach helps to reduce cognitive overload and supports differentiated instruction, catering to the diverse learning needs and abilities of students. This adaptability makes GeoGebra an effective tool for both teacher-directed and student-centered learning environments [

40,

49,

50].

From teachers’ perspectives, GeoGebra represents an innovative transformation in mathematics instruction, bridging traditional pedagogy with digital interactivity. Educators perceive it as a medium that not only visualizes abstract mathematical concepts but also supports active participation and inquiry-based learning. In conventional classroom contexts, teachers often encounter difficulties in illustrating dynamic relationships—such as the derivative as a rate of change or the geometrical meaning of integration. GeoGebra’s real-time manipulation of parameters enables teachers to visually communicate these complex relationships, promoting clearer conceptual understanding among students. This visualization process is particularly valuable in supporting differentiated instruction, as it allows teachers to address diverse learning needs through multimodal representations. Such flexibility enhances pedagogical clarity and supports the transition from rote memorization to conceptual learning (Al-Hassan & Diah, 2024; Hohenwarter & Lavicza, 2021).

Teachers acknowledge that GeoGebra contributes significantly to instructional efficiency, particularly in the preparation of lesson materials and demonstrations. Rather than relying on static diagrams or lengthy algebraic derivations, educators can utilize GeoGebra’s dynamic graphs to illustrate complex ideas in a visually appealing and cognitively accessible manner. This efficiency not only saves time but also allows for more in-depth discussions during classroom sessions. Moreover, teachers can modify visual parameters instantly, which helps them respond adaptively to students’ questions and misconceptions in real time. Such interactive flexibility enhances classroom engagement and promotes the development of a responsive teaching environment. Research has shown that digital tools like GeoGebra foster a more dialogical form of teaching, where teachers and students collaboratively construct understanding through shared visual exploration (Johnson & Nakamura, 2023; Singh & Roberts, 2025).

In the context of instructional design, GeoGebra serves as a scaffold for developing conceptual hierarchies in mathematics. Teachers can guide students from concrete to abstract understanding by first manipulating visual models before introducing formal definitions or symbolic notation. This aligns with the constructivist principle of gradual abstraction, which posits that learners internalize complex ideas more effectively when supported by visual and experiential representations. Teachers therefore use GeoGebra as a bridge between intuitive reasoning and formal mathematical proof. The software also allows for the customization of tasks, enabling teachers to design explorative activities that correspond to different levels of cognitive demand. As such, GeoGebra functions as both a didactic tool and an assessment instrument that reflects students’ evolving conceptual structures (Liu & Zhang, 2022; Andersson & Petrovic, 2023).

Teachers report that one of the most powerful features of GeoGebra is its capacity to reduce cognitive overload in learners. By simplifying visual complexity and focusing attention on key mathematical relationships, the tool helps students process information more efficiently. This is especially beneficial for topics like geometric transformations, multivariable calculus, or function analysis, where spatial and symbolic reasoning often intersect. When teachers use GeoGebra to demonstrate transformations dynamically—such as rotation, dilation, or reflection—students can observe immediate consequences of parameter adjustments. This process aids schema formation and strengthens long-term conceptual retention. Thus, GeoGebra does not merely act as an instructional supplement; it actively reshapes how teachers manage cognitive scaffolding in mathematics classrooms (Chen & Martínez, 2021; Gómez & Thakur, 2022).

From a pedagogical management standpoint, GeoGebra facilitates formative assessment and reflective teaching practices. Teachers can observe how students manipulate mathematical objects, identify their reasoning strategies, and intervene when misconceptions arise. This capability transforms GeoGebra into a diagnostic instrument that supports adaptive feedback. Teachers often design exploratory worksheets within GeoGebra to monitor student engagement, interpret problem-solving behaviors, and assess conceptual understanding dynamically. Such formative integration enhances teachers’ ability to provide individualized support, thereby improving overall learning outcomes. In this regard, GeoGebra aligns with contemporary educational paradigms emphasizing feedback-rich and learner-centered environments (Martínez & Santos, 2020; El-Shamy & Rahman, 2023).

GeoGebra also empowers teachers to foster collaboration and peer learning within digital learning ecosystems. In hybrid and online classrooms, shared GeoGebra activities encourage students to discuss conjectures, test hypotheses, and justify their reasoning collectively. Teachers become facilitators of discourse rather than transmitters of information. The collaborative use of GeoGebra contributes to social constructivism, where meaning is co-constructed through interaction and reflection. Teachers report that this approach increases student motivation, self-efficacy, and academic resilience, particularly in post-pandemic blended learning settings (de Freitas & Wang, 2025; Rahim & Widodo, 2021).

The integration of GeoGebra into lesson planning has also redefined teachers’ roles as instructional designers. Teachers are now expected to curate digital learning experiences rather than deliver pre-structured content. GeoGebra provides templates, applets, and interactive modules that teachers can modify to align with curricular standards and student competencies. This transformation promotes pedagogical creativity and encourages teachers to experiment with inquiry-based methods. The ability to visualize multiple mathematical representations simultaneously strengthens teachers’ confidence in delivering abstract topics such as calculus and trigonometry (Ibrahim & Khalid, 2024; Budiarto & Yuliani, 2022).

Professional development programs increasingly incorporate GeoGebra training as part of digital pedagogy initiatives. Teachers who receive structured support in using GeoGebra demonstrate higher instructional competence, stronger technology acceptance, and greater pedagogical adaptability. Such training enables teachers to integrate the software not as a novelty but as an essential component of modern mathematics instruction. Studies indicate that continuous professional development fosters a positive technological mindset, helping teachers view GeoGebra as a partner in facilitating conceptual understanding rather than a supplementary tool (Singh & Roberts, 2025; Zhao & Kim, 2023).

Teachers’ experiences also highlight the ethical and equity dimensions of GeoGebra’s adoption. While the software is free for non-commercial educational use, limited digital infrastructure in some regions constrains equitable access. Teachers often face challenges related to bandwidth, device compatibility, and students’ digital literacy levels. Nevertheless, GeoGebra’s multiplatform nature—spanning Windows, macOS, Android, and web-based applications—mitigates these barriers to some extent. Teachers advocate for institutional policies that support digital equity to ensure consistent and fair access to GeoGebra-based instruction across diverse learning contexts (Al-Hassan & Diah, 2024; Andersson & Petrovic, 2023).

Beyond efficiency, GeoGebra enhances teachers’ reflective capacity regarding their instructional strategies. The dynamic feedback from student interactions enables teachers to evaluate which representations or visualizations are most effective. This ongoing reflection fosters a culture of continuous improvement and evidence-based practice. Teachers gain insights into students’ learning trajectories, allowing for more precise pedagogical interventions. GeoGebra thus becomes a mirror through which teachers refine their instructional design and pedagogical reasoning (Chen & Martínez, 2021; Hohenwarter & Lavicza, 2021).

Teachers also value GeoGebra’s potential to promote cross-disciplinary learning. By connecting mathematical visualization with real-world phenomena—such as physics simulations, architecture design, or data analysis—teachers can design integrative learning modules. This interdisciplinary approach supports STEM education goals and strengthens students’ ability to apply mathematical reasoning beyond the classroom. Teachers report that such applications increase relevance and contextual understanding, making mathematics more meaningful and applicable to everyday problem-solving (Gómez & Thakur, 2022; de Freitas & Wang, 2025).

In terms of classroom management, GeoGebra enhances teacher-student interaction and reduces passive learning behaviors. Teachers can invite students to manipulate digital objects directly during lessons, transforming the classroom into a participatory learning space. This participatory model increases engagement, as students are not merely observers but co-constructors of mathematical meaning. Teachers find that GeoGebra’s interactivity fosters a sense of ownership over learning outcomes and encourages curiosity-driven exploration (Rahim & Widodo, 2021; Liu & Zhang, 2022).

Teachers’ testimonials reveal that GeoGebra supports differentiated instruction effectively. Its customizable interface allows educators to adjust complexity levels and provide additional scaffolds for struggling learners. Simultaneously, advanced students can explore extended problem sets, visual proofs, and parametric variations independently. Teachers appreciate that GeoGebra can simultaneously cater to various learning profiles without fragmenting instructional coherence (Ibrahim & Khalid, 2024; Martínez & Santos, 2020).

GeoGebra’s influence extends to teachers’ assessment philosophy. Instead of relying solely on summative evaluations, teachers can now integrate authentic, performance-based assessments using GeoGebra applets. These digital artifacts serve as evidence of conceptual mastery and mathematical reasoning. Teachers report that such assessments encourage deeper engagement and foster metacognitive reflection among students. The capacity to visualize thought processes transforms how teachers evaluate and interpret student learning (Johnson & Nakamura, 2023; Singh & Roberts, 2025).

In conclusion, teachers perceive GeoGebra as an indispensable pedagogical partner that enhances instructional clarity, efficiency, and adaptability. It empowers teachers to visualize abstract concepts, manage cognitive complexity, and support diverse learners through interactive and constructivist methodologies. The alignment of GeoGebra with modern educational frameworks—such as inquiry-based learning and formative assessment—makes it an enduring asset in digital pedagogy. Teachers’ experiences collectively affirm that GeoGebra not only transforms how mathematics is taught but also how it is understood and experienced by both educators and students (Zhao & Kim, 2023; Al-Hassan & Diah, 2024).

4.3. Fostering Collaborative and Constructivist Learning

Another major pedagogical contribution of GeoGebra lies in its capacity to foster collaboration and student-centered learning. The integration of GeoGebra into group activities encourages students to articulate their reasoning, test hypotheses, and discuss alternative problem-solving strategies with their peers. Such collaborative exploration promotes critical thinking, communication, and reflection, aligning with Vygotsky’s social constructivist framework. Students learn not only through individual engagement but also through shared meaning-making within a community of inquiry. As they construct and manipulate digital objects, learners gain a deeper sense of ownership and autonomy over their learning processes [

15,

29].

Another major pedagogical contribution of GeoGebra lies in its capacity to foster collaboration and student-centered learning. The integration of GeoGebra into group activities encourages students to articulate their reasoning, test hypotheses, and discuss alternative problem-solving strategies with their peers. Such collaborative exploration promotes critical thinking, communication, and reflection, aligning with Vygotsky’s social constructivist framework. Students learn not only through individual engagement but also through shared meaning-making within a community of inquiry. As they construct and manipulate digital objects, learners gain a deeper sense of ownership and autonomy over their learning processes, reflecting a shift from teacher-directed to learner-centered paradigms (Zhao & Kim, 2023; Singh & Roberts, 2025).

In collaborative GeoGebra environments, students collectively explore mathematical relationships, engage in dialogue, and negotiate conceptual understanding. This process transforms traditional classroom hierarchies into democratic spaces where all participants can contribute equally to problem-solving. The shared screen or digital workspace facilitates co-construction of mathematical knowledge, as students visualize, manipulate, and discuss mathematical entities in real time. Such interactive engagement promotes peer scaffolding, where stronger students help their peers internalize abstract concepts. This aligns with Vygotsky’s notion of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), emphasizing learning as a socially mediated process (Andersson & Petrovic, 2023; Gómez & Thakur, 2022).

GeoGebra also supports synchronous and asynchronous collaboration, accommodating diverse learning contexts. In synchronous group settings, students collaboratively model functions, geometric transformations, or calculus concepts through shared digital boards. In asynchronous modes—such as online projects or blended learning environments—students can modify and comment on each other’s GeoGebra files, extending the learning process beyond classroom boundaries. Teachers report that such digital collaboration encourages reflective dialogue and deepens students’ conceptual insight (de Freitas & Wang, 2025; Chen & Martínez, 2021).

The interactive affordances of GeoGebra encourage dialogue-driven inquiry, where students articulate hypotheses and validate them through dynamic manipulation. As they engage with visual feedback, learners refine their reasoning processes and develop metacognitive awareness of their problem-solving strategies. Collaborative discourse around GeoGebra constructions enhances argumentation skills and logical reasoning, which are central to higher-order mathematical thinking. This interactional approach positions GeoGebra as not just a visualization tool but a platform for intellectual exchange and co-inquiry (Rahim & Widodo, 2021; Liu & Zhang, 2022).

Teachers leveraging GeoGebra for group tasks often adopt a facilitator role, guiding discussion rather than directly transmitting knowledge. This pedagogical shift empowers students to take initiative, explore alternatives, and justify their thinking using digital representations. The visualization of mathematical patterns through GeoGebra enhances shared cognition, as students can simultaneously observe, question, and refine ideas collaboratively. Such environments promote intersubjectivity, where mutual understanding emerges through social interaction (Hohenwarter & Lavicza, 2021; Ibrahim & Khalid, 2024).

GeoGebra’s design aligns naturally with inquiry-based and project-based pedagogies. Students working collaboratively can engage in mathematical investigations that require exploration, conjecture, and validation. By testing their hypotheses using GeoGebra’s dynamic tools, they experience authentic scientific inquiry similar to that practiced by mathematicians. Teachers observe that these experiences foster a sense of mathematical agency, creativity, and resilience in problem-solving. This mirrors the social constructivist view that learning occurs through collective exploration and dialogue (Martínez & Santos, 2020; Singh & Roberts, 2025).

One significant outcome of collaborative GeoGebra learning is the development of communication competence in mathematics. Students must explain their reasoning clearly, negotiate meaning, and interpret others’ perspectives using precise mathematical language. The software’s shared visualization interface supports multimodal communication, combining verbal, symbolic, and graphical modes of expression. Through such interaction, learners enhance both mathematical discourse and interpersonal skills, essential for academic and professional success (Andersson & Petrovic, 2023; Gómez & Thakur, 2022).

GeoGebra-based collaboration also enhances equity and inclusivity within mathematics classrooms. Because students can engage visually and interactively, those with varying linguistic or mathematical abilities find alternative pathways to participation. This inclusive dimension aligns with Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which advocates for multiple means of engagement and representation. Teachers report that GeoGebra helps reduce anxiety among lower-achieving students while challenging high performers through deeper exploratory tasks (El-Shamy & Rahman, 2023; Budiarto & Yuliani, 2022).

In technology-enhanced classrooms, GeoGebra serves as a social bridge connecting individual and collective cognition. The visual and interactive nature of the platform helps students externalize their thought processes, making reasoning visible and discussable. This transparency allows peers and teachers to engage in meaningful feedback, correction, and co-construction of understanding. The dialogical cycle of explanation and reflection aligns with social learning theories that emphasize shared cognitive responsibility (Johnson & Nakamura, 2023; Liu & Zhang, 2022).

The integration of GeoGebra into collaborative settings also encourages students to assume different cognitive roles—explorer, verifier, critic, and designer. This diversity of roles mirrors authentic problem-solving contexts and encourages team-based accountability. The interplay of these roles promotes distributed cognition, where knowledge is collectively developed and refined. Teachers find that this distributed approach enhances students’ autonomy and reduces overreliance on teacher authority (Ibrahim & Khalid, 2024; Rahim & Widodo, 2021).

Studies show that collaboration through GeoGebra can significantly improve students’ attitudes toward mathematics. Group-based dynamic modeling reduces the perception of mathematics as rigid or abstract, replacing it with a sense of discovery and shared creativity. Positive peer interaction and visual engagement foster a growth mindset and sustained motivation to learn. Teachers note that such environments cultivate perseverance and collaborative efficacy—traits strongly associated with lifelong learning (Zhao & Kim, 2023; de Freitas & Wang, 2025).

GeoGebra-based collaboration also encourages the integration of reflective practices. After group tasks, students often engage in discussions about the reasoning process, error analysis, and conceptual insights gained through exploration. This reflection enhances metacognition and strengthens students’ ability to self-regulate their learning. Teachers can facilitate reflective debriefs using GeoGebra’s playback features, allowing students to review and evaluate their group decisions (Chen & Martínez, 2021; Singh & Roberts, 2025).

The digital collaboration enabled by GeoGebra extends to global learning communities. Through cloud-based sharing and online collaboration, students can participate in international projects, comparing mathematical models across cultural contexts. Such global interaction broadens perspectives and promotes intercultural understanding within mathematical discourse. This evolution of collaborative learning reflects the growing globalization of STEM education (Al-Hassan & Diah, 2024; Hohenwarter & Lavicza, 2021).

From a research standpoint, GeoGebra’s collaborative affordances have inspired empirical studies on cognitive development, communication, and technology acceptance. Data indicate that collaborative GeoGebra environments enhance conceptual retention, problem-solving efficiency, and self-efficacy. Teachers and researchers recognize that these environments not only reinforce content mastery but also nurture critical dispositions for lifelong mathematical reasoning (Andersson & Petrovic, 2023; El-Shamy & Rahman, 2023).