3.1.1. GEOGEBRA

i. GeoGebra in Learning

GeoGebra is an interactive and dynamic software designed to support mathematics learning, especially in the fields of geometry, algebra, calculus, and now developing in the field of statistics. The app was first developed by Markus Hohenwarter in 2001, and since then GeoGebra has continued to undergo feature improvements, including the addition of capabilities for statistical data visualization, graphing, and probability simulation [

78] . Currently, GeoGebra has been used by more than 20 million teachers and students around the world, with the existence of 155 GeoGebra Institutes (IGI) spread across various countries and translations into more than 62 languages, including Indonesian, making it easier for local users to use it in learning. Its accessibility that can be used on both computer and mobile devices makes GeoGebra one of the most flexible educational applications that are in line with the times. In the Indonesian context, the availability of GeoGebra in Indonesian has encouraged an increase in its use by teachers and lecturers in various higher education institutions. [

30,

31]

The evolution of GeoGebra from a simple geometry tool into a comprehensive mathematical platform demonstrates the transformation of educational technology toward dynamic and interactive learning environments. The integration of statistical features, such as data analysis tools, regression modeling, and probability simulations, has positioned GeoGebra as a versatile application capable of supporting multidisciplinary teaching and learning processes. Through these features, students can explore mathematical and statistical relationships in a visual, exploratory, and inquiry-based manner, enabling a shift from passive to active learning. Studies have shown that such dynamic visualization tools enhance students’ conceptual understanding and cognitive engagement compared to conventional instruction. Moreover, the use of GeoGebra in statistics encourages learners to connect theoretical principles with empirical data through simulation-based experiments, making abstract ideas more tangible. As technology becomes more embedded in education, GeoGebra stands as a model of open-access innovation that bridges pedagogical theory and computational practice. This adaptability is essential in fostering statistical literacy in an era where data-driven reasoning is fundamental across disciplines [

91].

From a pedagogical perspective, GeoGebra supports constructivist and inquiry-based learning by allowing students to actively manipulate mathematical and statistical objects to observe patterns and relationships. The interactive features enable learners to test hypotheses, visualize data transformations, and understand statistical variability more effectively than through static materials. Teachers, in turn, can design customized learning tasks that align with students’ prior knowledge and cognitive levels, promoting differentiated instruction. This adaptability aligns with the principles of Realistic Mathematics Education (RME), which emphasizes the use of contextual and meaningful problems to stimulate understanding. GeoGebra’s interactive applets provide a rich environment where statistical learning is grounded in authentic problem-solving situations. Moreover, it allows educators to integrate technology seamlessly into their pedagogical design, facilitating a balance between procedural fluency and conceptual depth. In this regard, GeoGebra serves as a mediator between theoretical abstraction and practical application in mathematical statistics education [

92].

The role of GeoGebra in improving student motivation and engagement has also been widely acknowledged in recent educational research. Interactive simulations and visualizations foster a sense of curiosity, autonomy, and satisfaction during the learning process, particularly among students who might otherwise struggle with abstract mathematical ideas. The integration of GeoGebra in blended and online learning environments has been shown to increase participation and improve performance outcomes. For instance, students using GeoGebra in data analysis tasks exhibit higher retention rates and more accurate interpretations of statistical information. This engagement effect can be attributed to the multimodal nature of the platform, which combines visual, symbolic, and numerical representations. Furthermore, the use of GeoGebra aligns with current educational trends emphasizing digital literacy and computational thinking as key [

93,

94].

The integration of GeoGebra into statistical learning environments enhances students’ capacity for critical thinking and conceptual understanding. When learners interact with dynamic visualizations, they are not merely passive recipients of information but become active participants in constructing their own knowledge structures. This constructivist approach enables them to manipulate variables, observe real-time changes, and identify mathematical relationships through exploration. Such experiences make statistical reasoning more intuitive, especially when dealing with complex data sets or probability models that are difficult to comprehend through symbolic formulas alone. Additionally, GeoGebra promotes self-directed learning, as students are able to experiment independently and validate hypotheses without relying solely on instructor demonstrations. This hands-on interaction fosters deeper comprehension of statistical principles such as distribution, variability, and correlation. As reported in recent studies, technology-enhanced visualization tools like GeoGebra can significantly strengthen learners’ analytical abilities and conceptual retention over time [

95,

96].

Beyond enhancing individual learning, GeoGebra also plays a crucial role in fostering collaborative problem-solving within digital classrooms. Instructors can design interactive applets that encourage small-group discussions, peer feedback, and cooperative exploration of data. This pedagogical approach transforms the traditional lecture format into an inquiry-based experience, where students exchange interpretations, question each other’s assumptions, and negotiate meaning. By enabling simultaneous manipulation of parameters and collective observation of outcomes, GeoGebra supports a social constructivist learning model consistent with Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development. Collaborative engagement of this kind not only strengthens communication and teamwork skills but also improves statistical literacy and data reasoning competence among students. Research in technology-assisted mathematics education underscores that interactive collaboration supported by GeoGebra can significantly elevate both student engagement and learning outcomes [

1,

3,

7].

Moreover, the flexibility of GeoGebra to adapt across different learning modalities—face-to-face, hybrid, and fully online—makes it highly relevant to modern education systems. During remote learning conditions, such as those intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic, GeoGebra proved invaluable for maintaining instructional continuity in quantitative courses. Lecturers used the platform to conduct live simulations, interactive assessments, and guided data analysis sessions, providing students with immediate feedback and visualization. These applications ensured that learners could still engage deeply with statistical material despite physical limitations of classroom settings. The platform’s open-source nature also reduced economic barriers to access, supporting educational equity in resource-limited contexts. Consequently, GeoGebra’s integration into e-learning ecosystems has been recognized as a catalyst for sustaining academic engagement and improving digital pedagogy in the post-pandemic era [

93,

94].

Another essential advantage of GeoGebra lies in its ability to link theoretical concepts with practical, real-world applications. By simulating phenomena such as sampling distributions, regression models, or probability experiments, the software bridges the gap between abstract theory and empirical reasoning. Students can observe the implications of statistical decisions, such as how varying sample sizes or standard deviations influence confidence intervals and hypothesis tests. This experiential learning dimension deepens comprehension and cultivates transferable analytical skills applicable in research and professional contexts. The immediacy of visual feedback helps learners recognize conceptual errors early and refine their reasoning strategies accordingly. This alignment between visualization and critical interpretation is vital in modern statistical education, where data-driven reasoning forms the backbone of scientific inquiry [

90,

91].

Lastly, GeoGebra’s continuing evolution through cloud integration, AI-assisted applets, and mobile accessibility signals a progressive step toward smart, adaptive learning technologies. Its developers have increasingly incorporated real-time analytics, allowing educators to monitor student progress and customize instruction based on performance patterns. This data-informed pedagogy enhances the personalization of learning experiences, offering targeted support to students with diverse learning needs. As a result, GeoGebra stands not only as a mathematical visualization tool but also as an intelligent platform for fostering digital competence, creativity, and autonomy. The growing body of literature highlights GeoGebra’s pivotal role in aligning mathematics education with Industry 4.0 competencies, including computational thinking, data literacy, and technological fluency [

92].

GeoGebra is also open source so it can be downloaded for free and allows various groups, both academics and practitioners, to use it widely. This makes GeoGebra a medium that not only supports knowledge transfer, but also encourages creativity in problem-solving through simulation and self-exploration. More than that, GeoGebra has been proven to support various learning models, such as problem-based learning, project-based learning, and collaborative learning. Thus, the role of GeoGebra in the world of education is increasingly important because it is in accordance with the 21st century learning paradigm that emphasizes critical, creative, collaborative, and communicative (4C) thinking skills. Not only that, this application is also in line with the education digital transformation policy launched by the government in the 2020–2025 period to improve the quality of human resources in the era of the industrial revolution 4.0 and society 5.0 [

38,

39,

40].

ii. Application Selection Considerations

In choosing a computer application for learning, there are five important considerations that need to be considered so that the application can be used widely and effectively. First, the app should provide a dynamic view so that it can be used to analyze abstract concepts more easily. Second, the application needs to allow users to express their personal models, so that students can develop their creativity and learning styles. Third, the application should assist in the search for mathematical models or patterns that emerge from the data or exploration process [

32,

33]. Fourth, applications must support the provision and processing of real data so that it is relevant to the context of daily life and academic research. Fifth, the application is expected to be able to share and communicate the results of exploration or modeling to others more simply. GeoGebra is an application that meets these five criteria well. Therefore, many recent studies confirm that GeoGebra has a significant role as an interactive mathematics learning medium that suits the needs of the digital age. For example, according to the results of recent research, the use of GeoGebra in mathematics learning has been proven to increase student engagement, strengthen concept understanding, and encourage collaboration between students in solving problems [

47,

48,

49,

57,

58,

59].

A dynamic visual interface is a fundamental characteristic of educational applications designed to promote mathematical understanding. Through an interactive and responsive display, learners are able to manipulate mathematical objects and observe immediate graphical outcomes, which bridge the gap between abstract reasoning and concrete representation. In GeoGebra, this feature facilitates deep conceptual comprehension by allowing students to explore statistical and mathematical relationships dynamically. The capacity to adjust variables, functions, or geometric parameters in real time enhances students’ cognitive engagement and promotes exploratory learning. As a result, abstract ideas such as function transformations, probability distributions, or data variability become more accessible. Such interactivity aligns with the principles of cognitive constructivism, emphasizing learning through active engagement rather than passive reception. Empirical studies demonstrate that dynamic visualization tools like GeoGebra significantly improve students’ conceptual retention and transfer of knowledge to new contexts [

96,

97,

98].

Equally important, effective mathematical applications must allow students to express personal models and individual interpretations of mathematical ideas. GeoGebra supports this by offering open-ended environments where learners can design their own constructions, applets, or simulations that reflect their understanding of mathematical principles. This flexibility empowers students to personalize their learning process and explore mathematical phenomena creatively. Instructors, meanwhile, can use these self-generated models as diagnostic tools to assess conceptual development and misconceptions. The platform’s adaptability encourages diverse learning styles, accommodating both visual and kinesthetic learners. Consequently, GeoGebra functions not only as a computational utility but also as a pedagogical bridge that connects personal creativity with formal mathematical structure. Recent findings affirm that students’ autonomy in model creation enhances motivation and self-efficacy in mathematics learning [

99,

100,

101].

The third crucial criterion for an effective learning application involves its ability to facilitate pattern recognition and mathematical modeling through exploration. GeoGebra excels in this domain by providing tools for regression analysis, curve fitting, and functional modeling that allow learners to derive mathematical relationships from data sets. This promotes inductive reasoning, as students can hypothesize patterns, test conjectures, and refine models iteratively. The real-time feedback available through graphical representation strengthens metacognitive awareness, enabling learners to evaluate the accuracy and relevance of their findings. Furthermore, the availability of dynamic sliders and linked algebraic views helps students develop an intuitive sense of how parameters influence mathematical behavior. Through this process, students become more proficient in constructing and interpreting models, a vital skill in the era of data-driven inquiry. Research supports that GeoGebra enhances analytical thinking by linking exploration to formal reasoning processes [

102,

103,

104].

The fourth feature concerns the application’s capacity to integrate real-world data, bridging theoretical learning with practical relevance. GeoGebra supports this integration by enabling users to import, manipulate, and analyze authentic datasets directly within its environment. Students can engage in activities such as investigating population growth, analyzing climate data, or studying economic trends using real statistical information. This approach situates mathematical learning in realistic contexts, thereby improving students’ data literacy and critical thinking. In addition, it supports interdisciplinary connections between mathematics, science, and social studies. Through such contextualized learning, students understand how mathematical tools function as instruments for problem-solving in real life. Studies have shown that when learners interact with authentic data through platforms like GeoGebra, their appreciation of mathematics as a practical discipline significantly increases [

105,

106,

107].

Finally, the fifth aspect of effective learning applications is their capacity to facilitate communication and sharing of mathematical ideas among learners. GeoGebra’s cloud-based ecosystem and collaborative features allow students and teachers to share applets, models, and visualizations easily across digital platforms. This encourages peer-to-peer learning, where knowledge construction becomes a social and interactive process. Learners can comment on, modify, and build upon others’ work, fostering a sense of academic community and collective inquiry. Moreover, the ability to publish interactive resources supports open educational practices and continuous professional development among educators. By simplifying the dissemination of mathematical representations, GeoGebra democratizes access to quality learning materials globally. Recent research highlights that such collaborative and communicative affordances of GeoGebra enhance both engagement and deeper learning outcomes [

108,

109,

110].

iii. GeoGebra as a Visualization Media

According to [

78], GeoGebra has various main functions that make it very useful in mathematics learning, including as a demonstration and visualization medium, as a construction aid, and as a discovery process media. The visualization function becomes especially crucial in statistical topics that are often considered abstract by students, such as probability distribution, hypothesis testing, and regression. With the dynamic graph feature, students can see firsthand the change in the shape of the opportunity distribution when the parameters are changed, or can understand the sampling process more intuitively through simulations. This not only helps students understand concepts more quickly, but also increases long-term retention of the material. The interactive visualization provided by GeoGebra is able to reduce the cognitive burden of students because abstract concepts are presented in the form of graphics that are easier to digest [

60]. Furthermore, GeoGebra supports exploration-based learning, where students can manipulate data and see its impact directly on graphs or tables. This approach is in accordance with constructivism theory which emphasizes the active role of students in building knowledge through learning experiences [

61]. Thus, GeoGebra is not just an additional application, but an integral part of modern pedagogical strategies that support statistical learning outcomes in higher education. [

34,

35]

GeoGebra serves as a multifunctional educational platform that integrates visualization, construction, and discovery in mathematical learning. Its versatility lies in its capacity to combine symbolic, algebraic, and graphical representations within a single interactive interface. This integration provides learners with a coherent and dynamic learning environment where abstract mathematical relationships become visually meaningful. In the context of statistical education, such visualization transforms symbolic formulas and theoretical distributions into concrete, manipulable forms. Students are able to directly observe how probability curves, regression lines, or sampling intervals behave when parameters are adjusted in real time. This interaction enhances conceptual understanding while simultaneously reinforcing procedural fluency. GeoGebra’s adaptability across devices—laptops, tablets, and smartphones—further broadens access to active learning experiences beyond classroom boundaries. Studies in the last few years have confirmed that this multifunctional capability makes GeoGebra a critical instrument in contemporary mathematics education [

111,

112].

Visualization plays an especially significant role in helping students comprehend complex and abstract topics in statistics. Concepts such as probability distributions, hypothesis testing, and correlation often present cognitive challenges when taught solely through numerical or symbolic approaches. GeoGebra bridges this gap by allowing learners to visualize how parameter changes affect statistical models dynamically. For instance, in exploring the normal distribution, students can manipulate the mean and standard deviation to observe how the curve’s shape and spread vary. Such immediate visual feedback enables learners to establish connections between theoretical parameters and empirical behavior, fostering deeper understanding. The interactive nature of this visualization not only clarifies statistical concepts but also reduces student anxiety and misconceptions in data interpretation. Consequently, students develop stronger confidence in their analytical skills. Empirical findings have shown that dynamic visualization tools like GeoGebra enhance comprehension and retention of abstract statistical concepts [

113,

114,

115].

Beyond mere visualization, GeoGebra fosters a discovery-oriented learning approach consistent with constructivist educational principles. It provides an environment where learners can actively explore mathematical and statistical relationships, generate hypotheses, and verify results through experimentation. By manipulating data and observing real-time outcomes, students construct their own understanding rather than memorizing predefined solutions. This experiential process strengthens both cognitive engagement and metacognitive awareness, as learners continuously reflect on their discoveries. Furthermore, GeoGebra encourages curiosity-driven inquiry by allowing learners to experiment freely without fear of making irreversible errors. Instructors can guide these explorations by posing open-ended questions or problem scenarios that stimulate deeper reasoning. Research supports that discovery-based learning facilitated through GeoGebra improves conceptual transfer and long-term academic achievement [

116,

117].

An additional advantage of GeoGebra lies in its ability to reduce students’ cognitive load through multimodal learning. When abstract ideas are presented in purely symbolic forms, students often experience cognitive overload due to the need to process several abstract operations simultaneously. GeoGebra alleviates this challenge by presenting the same information across multiple representations—graphical, algebraic, and numerical—allowing learners to select the form that best supports their understanding. This multisensory approach promotes more efficient mental processing and facilitates the integration of new knowledge with prior understanding. Moreover, by simplifying complex concepts visually, GeoGebra increases accessibility for diverse learners, including those with lower mathematical readiness. The combination of simplicity and interactivity makes it an effective bridge between abstract theory and practical comprehension. Recent educational research confirms that such multimodal digital environments significantly reduce extraneous cognitive load in mathematics learning [

118,

119,

120].

Finally, GeoGebra’s emphasis on exploration-based and collaborative learning aligns with the needs of higher education in the digital era. The platform’s capacity to simulate data-driven experiments and visualize outcomes enables students to approach statistics as an active process of discovery rather than passive knowledge reception. Instructors can design interactive tasks where students work in pairs or groups to analyze datasets, test hypotheses, and discuss graphical results. This promotes peer learning and collective problem-solving, two essential competencies in data-centered academic disciplines. Additionally, the platform’s sharing features allow for immediate dissemination of applets and results, facilitating academic collaboration beyond geographical limitations. As higher education increasingly integrates technology into pedagogical practice, GeoGebra exemplifies the shift toward student-centered, inquiry-driven instruction that enhances digital literacy and statistical reasoning simultaneously. Studies from recent years confirm its effectiveness as a pedagogical innovation that advances both engagement and understanding in statistical learning [

121,

122].

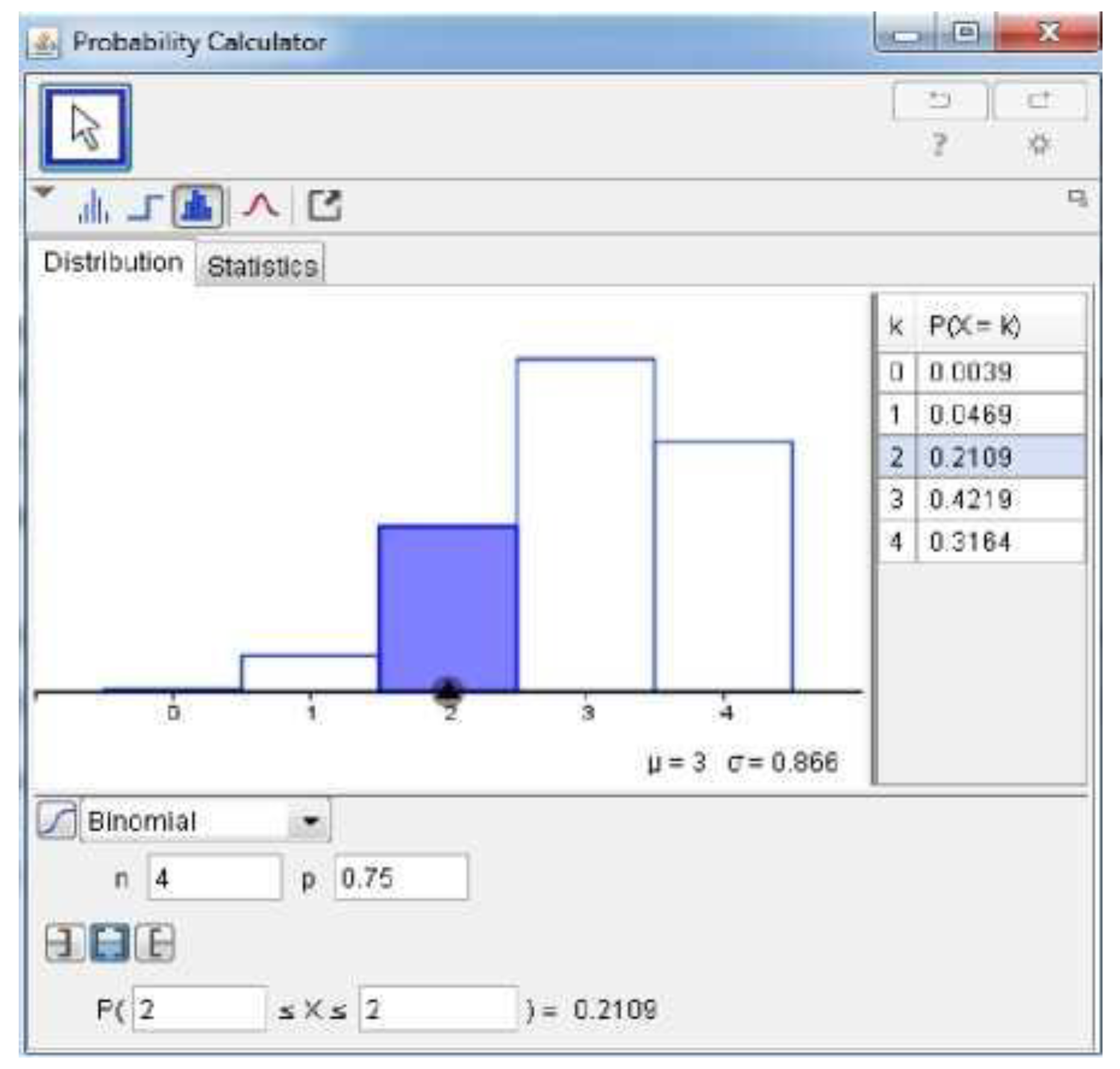

iv. GeoGebra in Statistical Learning

In the context of statistical learning, the use of GeoGebra focuses not only on the final result in the form of numbers or graphs, but also on the underlying procedural understanding. Students are not only invited to enter data, but also understand the analysis steps carried out by the application. Thus, GeoGebra helps students develop analytical and technical thinking skills. GeoGebra can be used to manage data, create frequency distribution graphs, calculate the size of data centers, and analyze opportunities [

36,

37,

38]. In addition, students can simulate the distribution of opportunities both continuously and discretely to strengthen their understanding of the properties of distribution. Hypothesis tests that are usually considered complicated by students can also be visualized more simply through interactive graphs displayed by GeoGebra. Thus, GeoGebra helps connect abstract statistical concepts with visual representations that are easier to understand. Recent studies have shown that students who use GeoGebra in statistical learning show a significant improvement in concept understanding compared to students who only use traditional lecture-based methods [

20,

24,

25,

26,

27].

In the context of statistical learning, the use of GeoGebra extends beyond mere computational output, emphasizing a deeper engagement with procedural understanding. Rather than treating statistics as a series of mechanical steps, GeoGebra enables learners to visualize and comprehend each stage of data analysis, from input to interpretation. Through interactive manipulation, students can observe how datasets are transformed through various analytical processes, such as organizing data, applying formulas, and constructing visual outputs. This procedural visibility helps bridge the gap between abstract numerical calculations and conceptual understanding. It also encourages students to ask critical questions about

why and

how certain methods produce specific results. As a result, learners gain not only technical proficiency but also metacognitive awareness of their analytical reasoning. Recent pedagogical research emphasizes that this process-oriented use of GeoGebra strengthens both statistical literacy and computational thinking in students [

123,

124,

125].

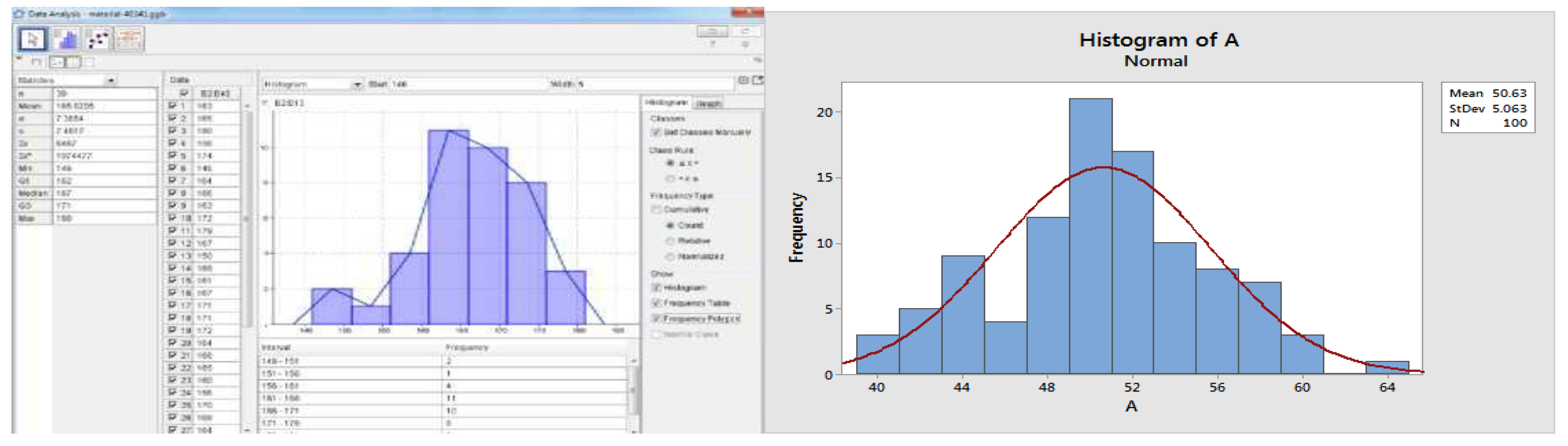

GeoGebra’s capacity to manage data and generate frequency distribution graphs allows students to explore statistical principles interactively and meaningfully. For instance, learners can quickly visualize changes in data centrality or dispersion by adjusting numerical inputs, thereby observing direct effects on histograms or box plots. Beyond static representation, GeoGebra promotes an active exploration of data variation, enabling learners to grasp the significance of statistical measures such as mean, median, mode, variance, and standard deviation in a dynamic context. By presenting these measures in real-time, the application transforms statistical learning into an exploratory experience rather than a passive exercise in formula memorization. This interactive feature encourages a hands-on approach that has been proven to enhance data literacy and deepen students’ understanding of descriptive statistics. As reported in empirical studies, using digital visualization tools such as GeoGebra significantly improves students’ retention and application of statistical measures [

126,

127].

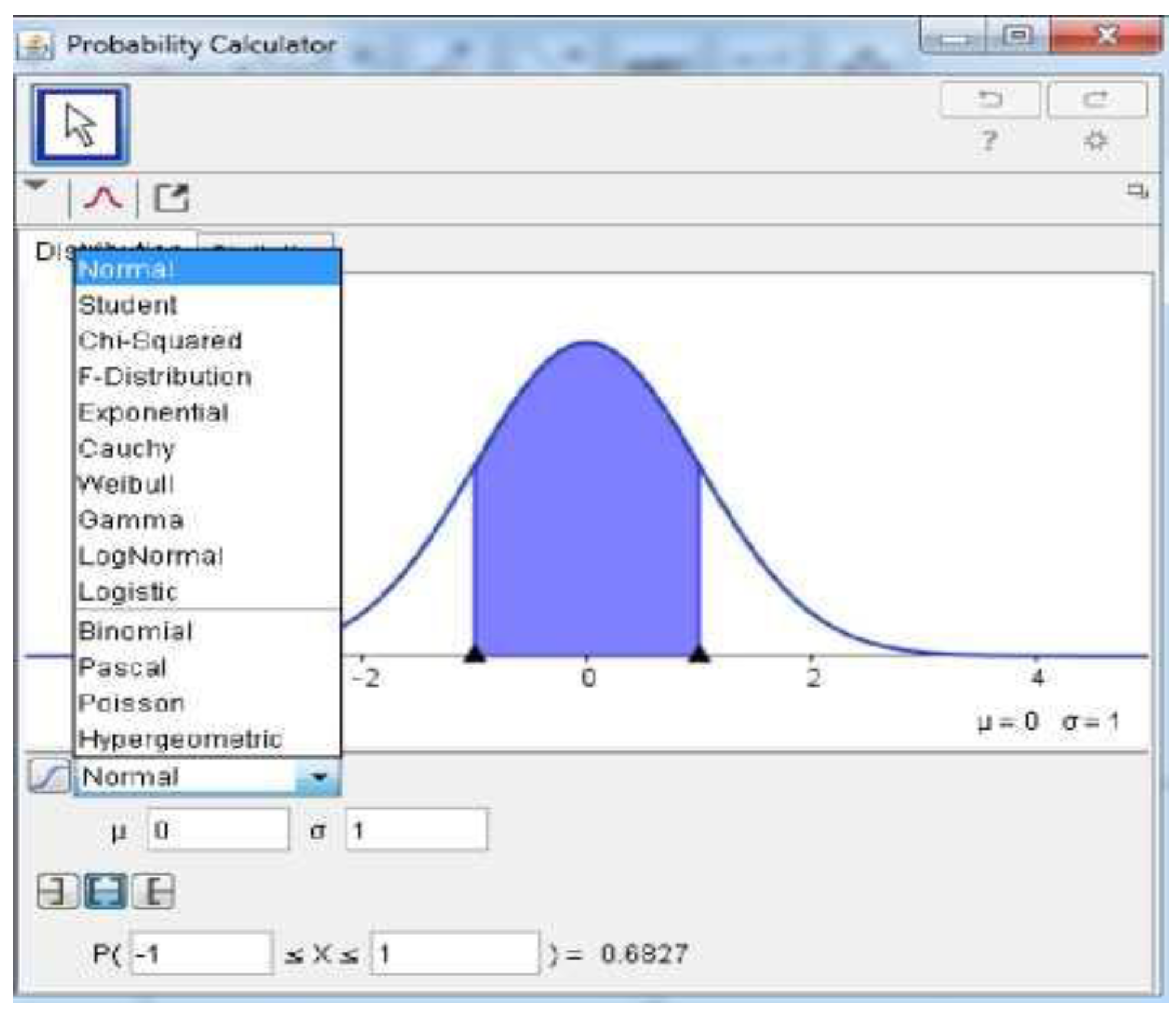

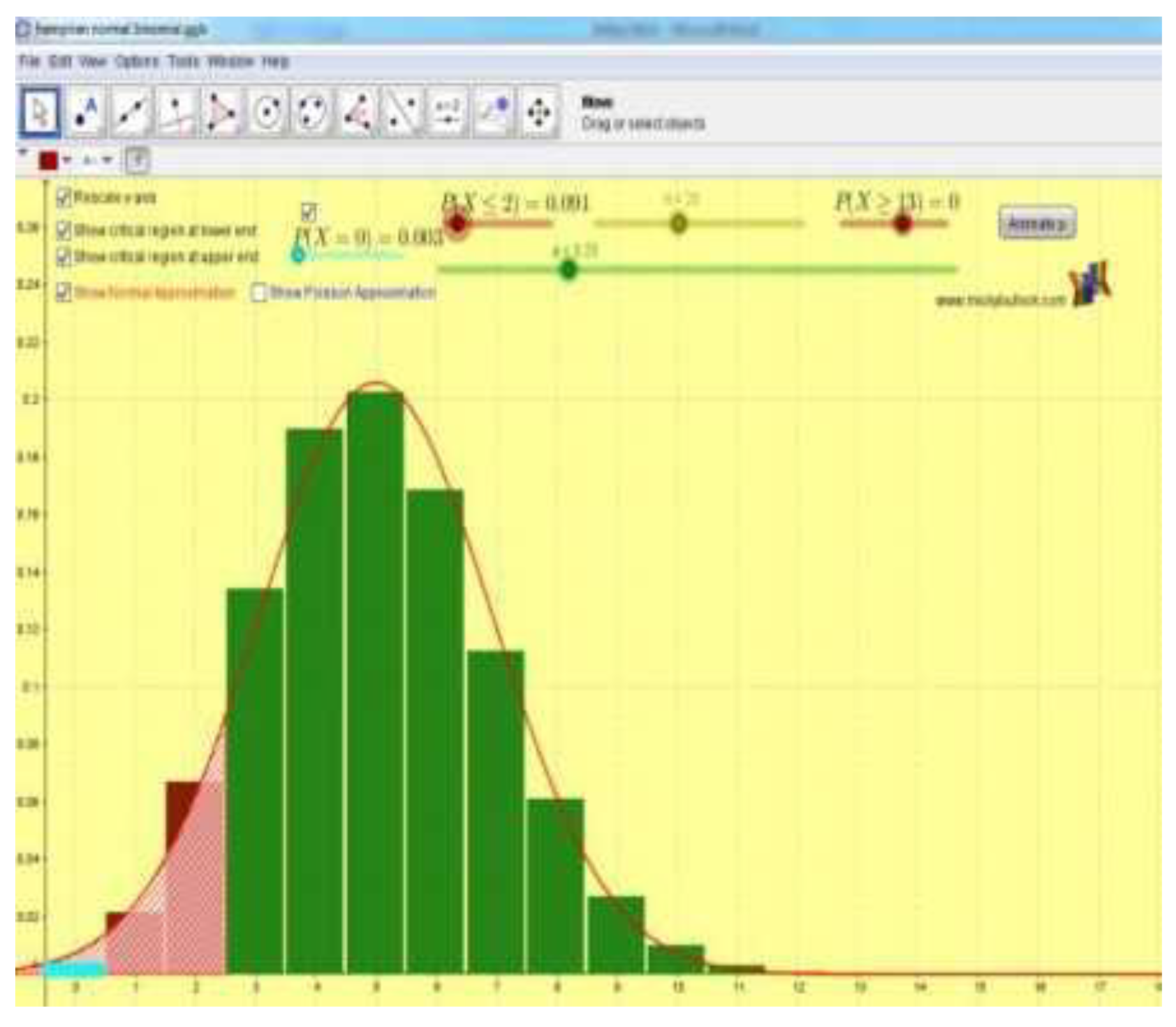

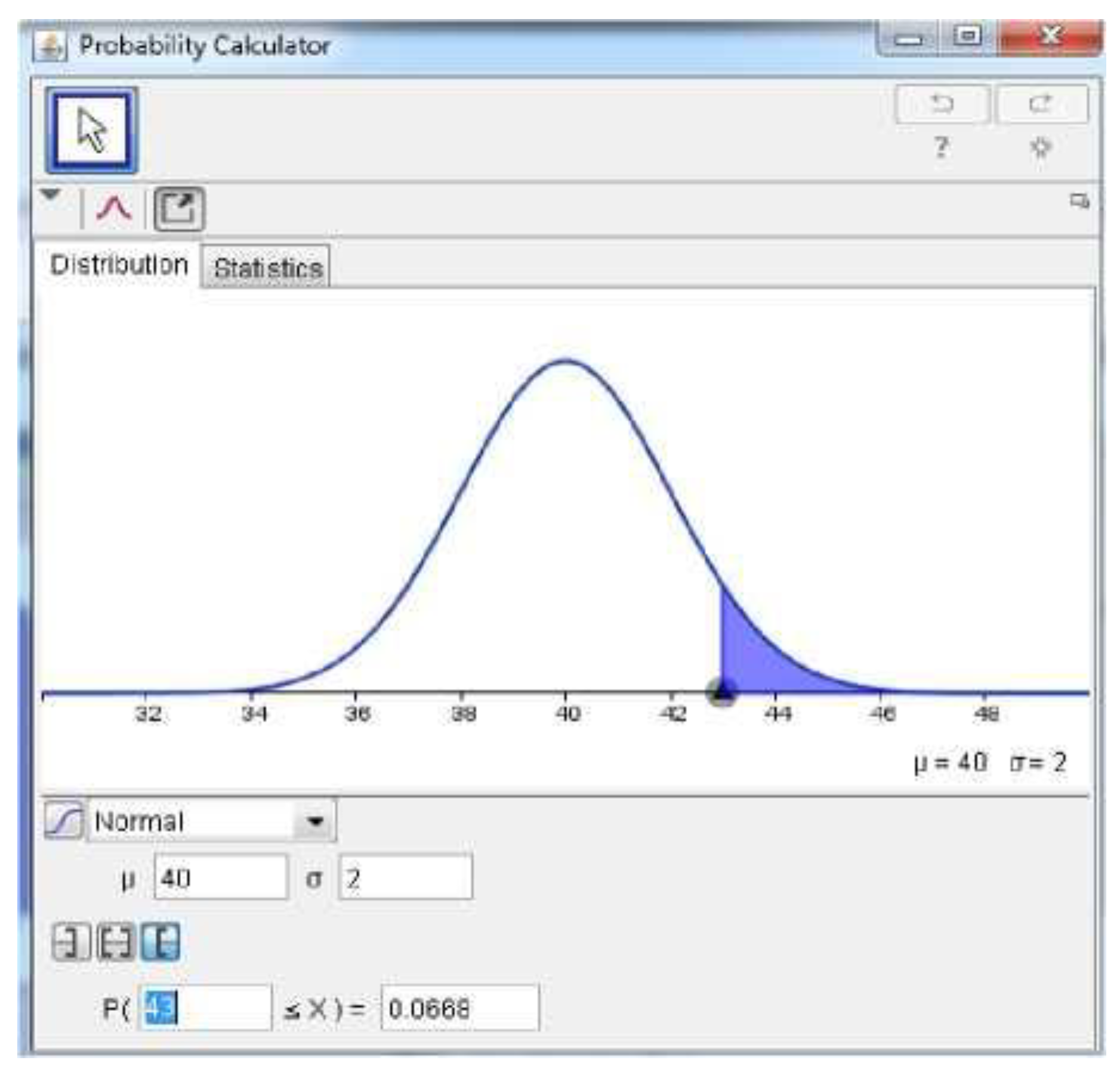

Another significant pedagogical advantage of GeoGebra lies in its ability to model probability distributions—both discrete and continuous—allowing learners to visualize randomness, variation, and uncertainty. Abstract ideas such as binomial, normal, or Poisson distributions become more tangible when represented dynamically, where students can manipulate parameters like sample size or probability of success and immediately see how curves change. This real-time visualization helps demystify probabilistic concepts that are often misunderstood when presented purely symbolically. Students can also simulate multiple experiments to observe convergence toward theoretical probabilities, reinforcing the concept of the law of large numbers. Such simulations foster a deeper appreciation for the stochastic nature of data and encourage a more intuitive grasp of variability. Research in recent years confirms that visual simulation in GeoGebra significantly enhances learners’ conceptual understanding of probability and statistical reasoning [

128,

129,

130].

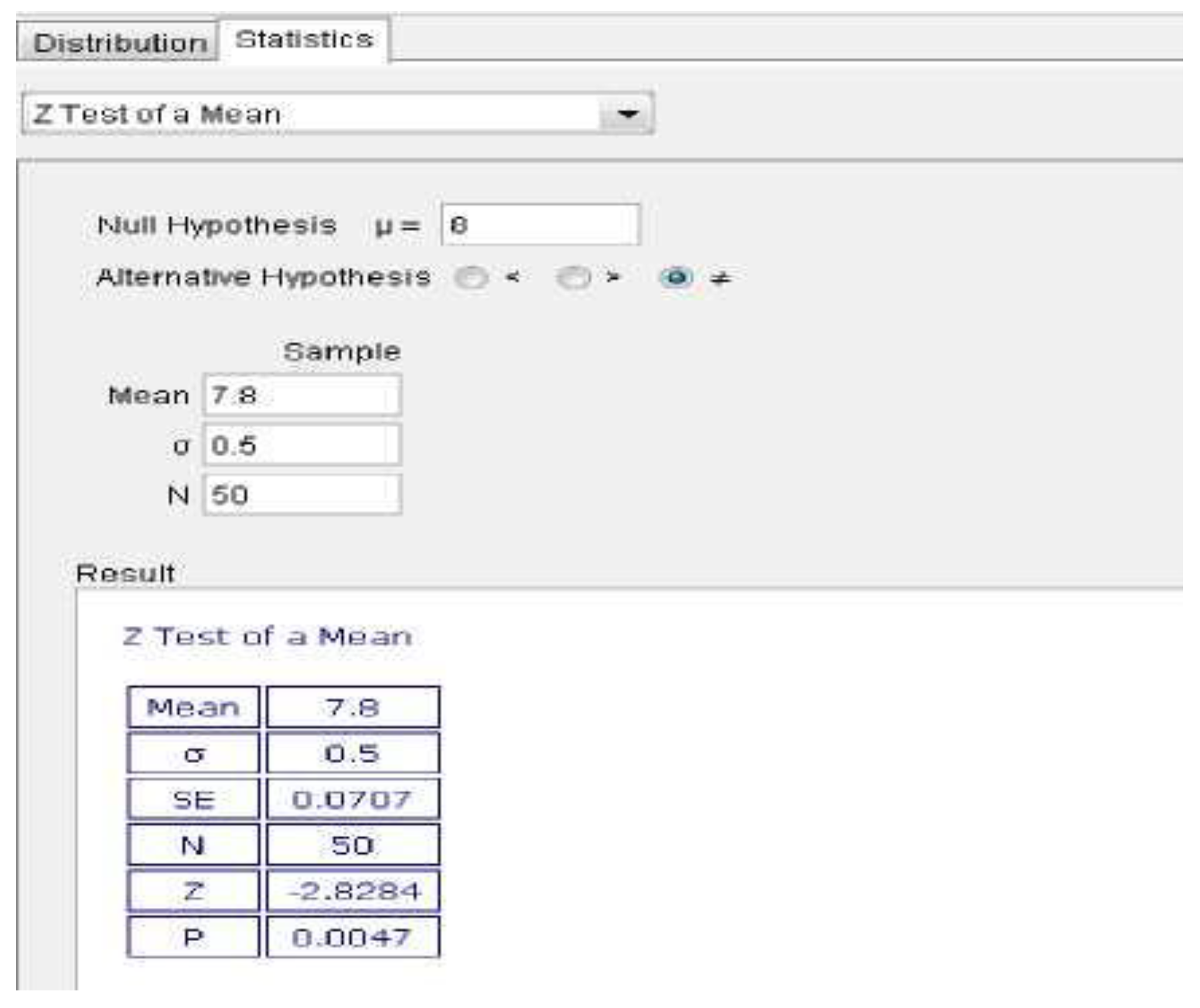

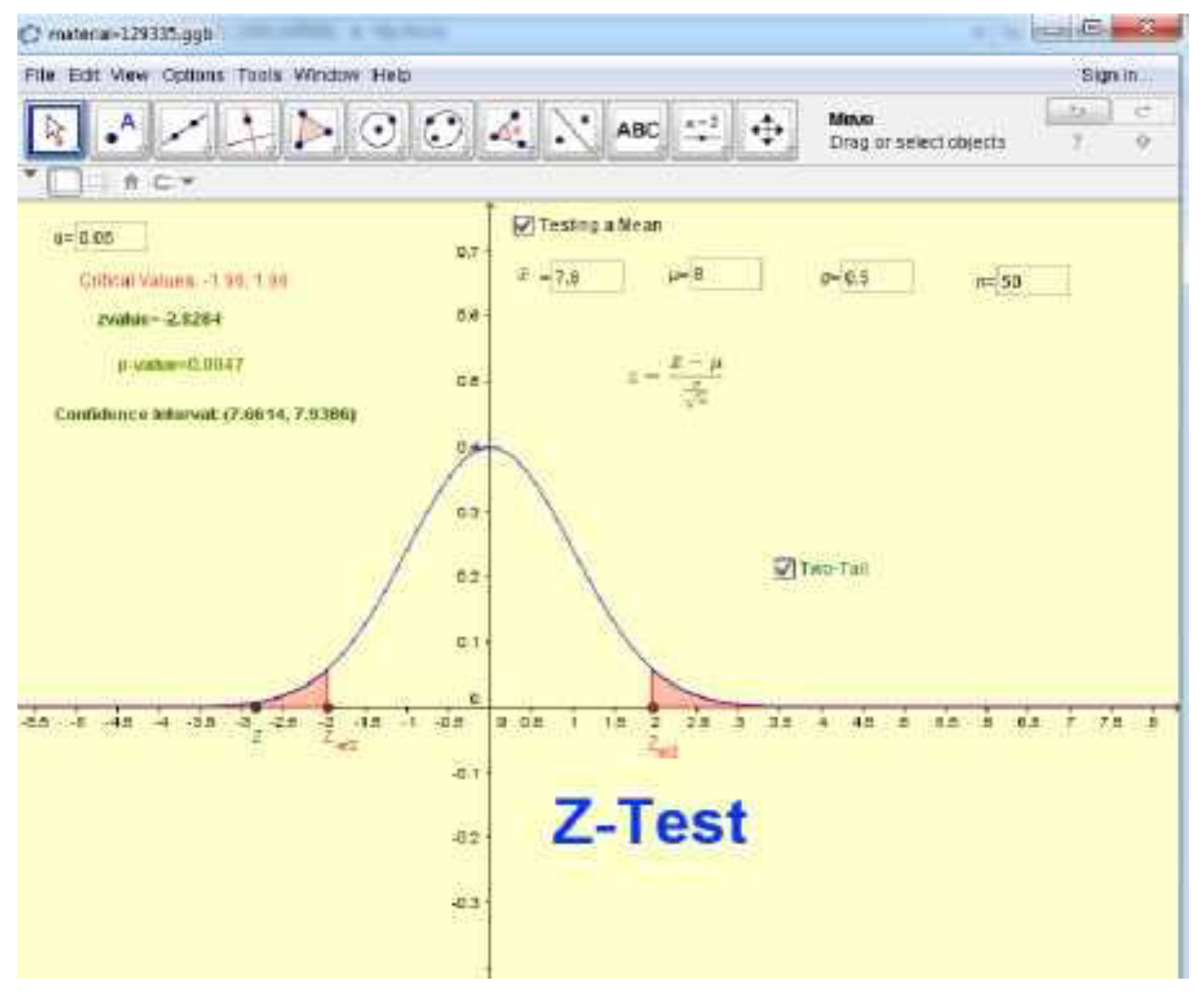

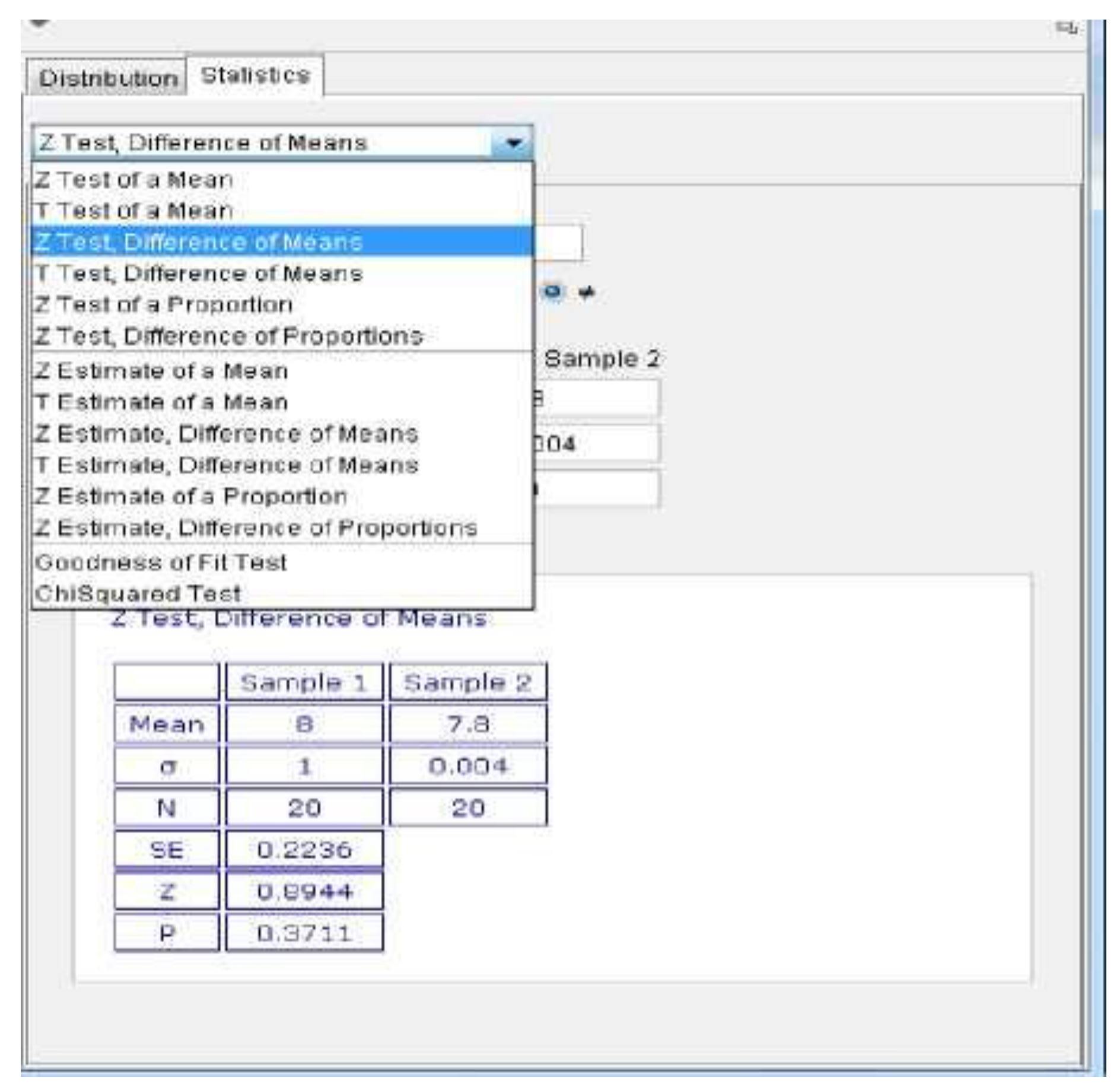

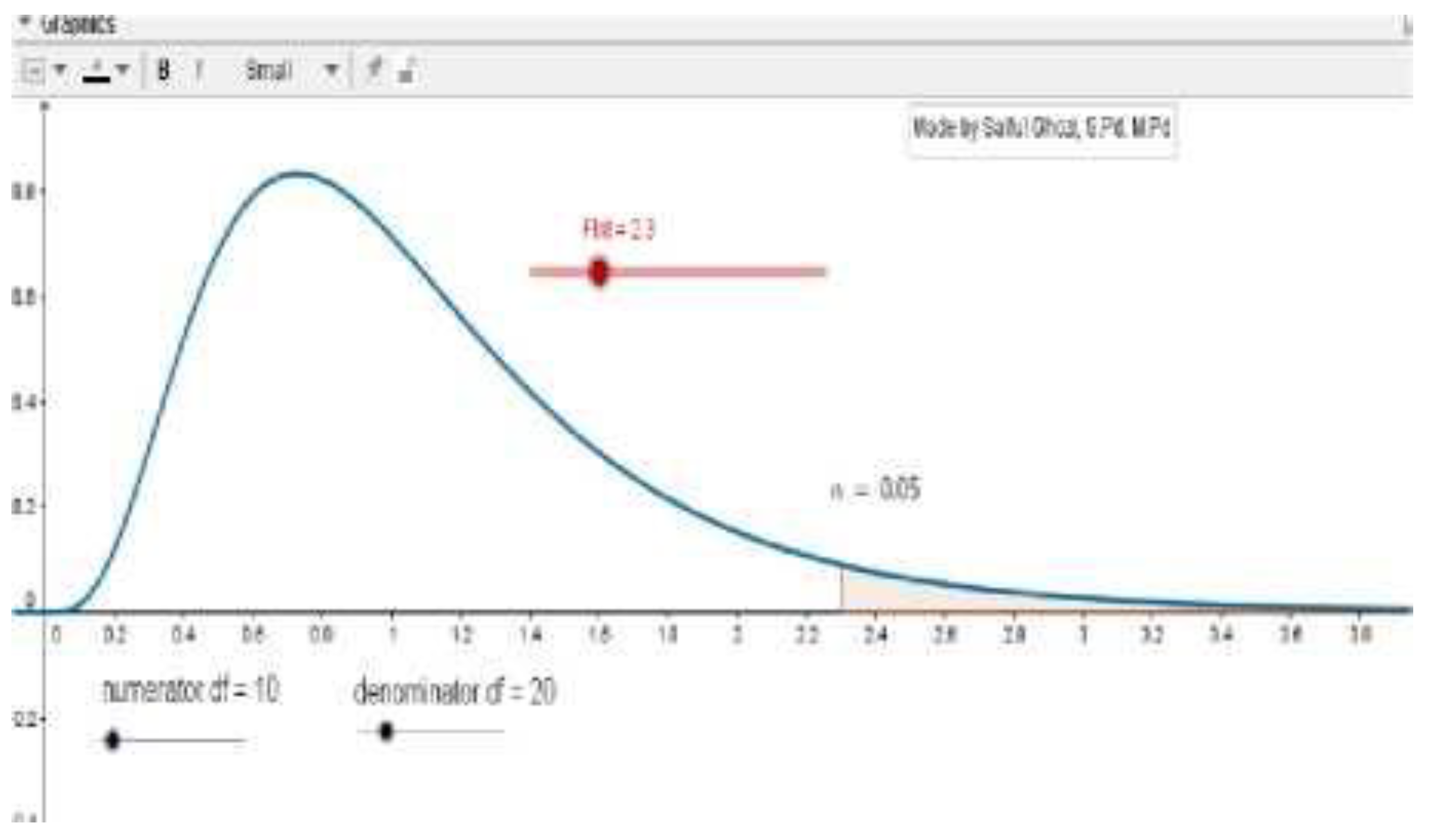

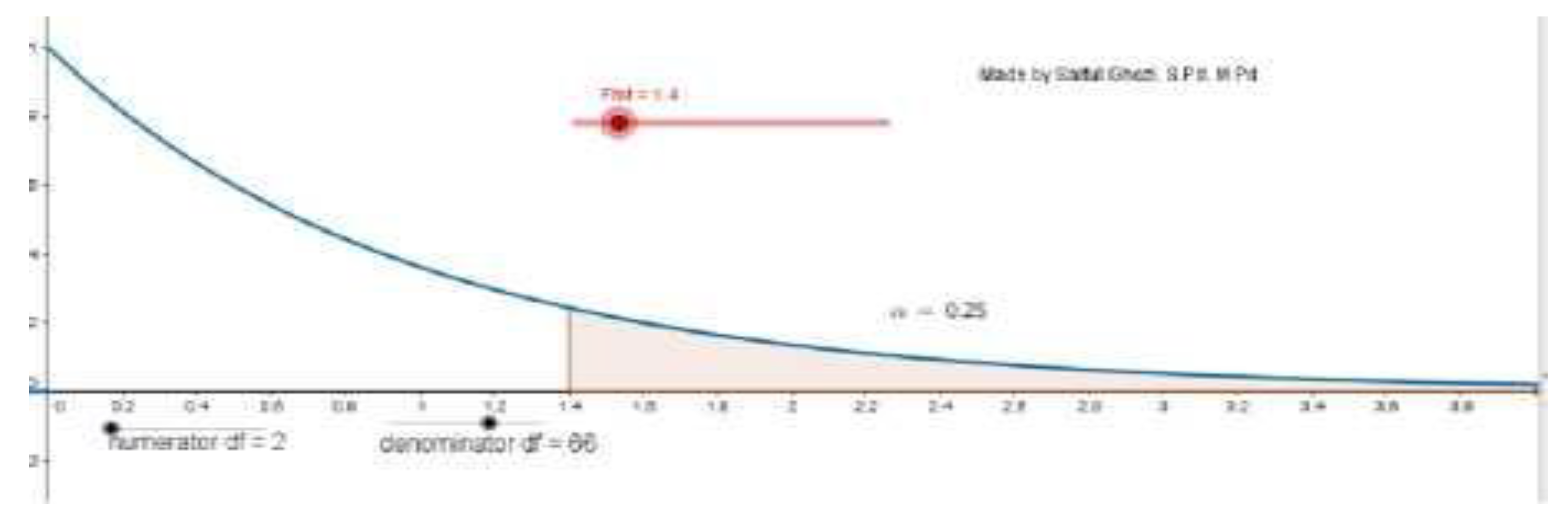

In inferential statistics, GeoGebra’s contribution is particularly valuable in visualizing hypothesis testing processes that many students traditionally find challenging. Through interactive graphical displays, learners can visualize critical regions, p-values, and sampling distributions that correspond to specific tests such as the

Z-test,

t-test, or

χ²-test. Rather than relying solely on abstract formulas, students can directly observe how test statistics are positioned within a distribution curve and how changes in parameters influence decision outcomes. This dynamic approach helps clarify the logic behind statistical inference—linking theoretical assumptions with graphical evidence. Moreover, by manipulating data inputs, students can explore how sample size, standard deviation, or confidence level affect hypothesis results. Consequently, GeoGebra transforms inferential statistics from an intimidating procedural topic into an engaging visual reasoning process. Studies have demonstrated that visual-based learning environments such as GeoGebra promote greater comprehension and confidence in hypothesis testing [

131].

Ultimately, the integration of GeoGebra in statistical education fosters a more holistic form of learning that connects abstract concepts to concrete visual representations. Students not only learn how to compute and interpret data but also develop analytical reasoning, pattern recognition, and decision-making abilities grounded in visual evidence. GeoGebra’s dynamic learning environment supports both inductive and deductive reasoning—allowing students to discover relationships through experimentation and verify them through formal analysis. This balance between procedural fluency and conceptual insight is vital for cultivating statistical competence in higher education. Moreover, GeoGebra’s flexibility to blend with other digital tools and learning management systems extends its relevance to both traditional and online classrooms. Current research affirms that the integration of GeoGebra in statistical pedagogy enhances student motivation, engagement, and long-term retention of key statistical ideas [

132].

v. Data Presentation and Processing with GeoGebra

One of the advantages of GeoGebra is its ability to present and process data interactively. Students can enter raw data and then visualize it in the form of bar charts, histograms, pie charts, or boxplots. This visualization helps students understand the distribution of data, detect outliers, and see general trends in the data [

39,

40]. In addition, students can also calculate data centering measures such as mean, median, and mode, as well as dispersion measures such as variance and standard deviation faster. This process not only generates numbers, but also emphasizes understanding why the value appears and how it is interpreted in the context of real data. With this approach, students not only master technical skills in data processing, but also analytical skills that are essential in understanding the reality represented by data. Therefore, the use of GeoGebra in data processing is considered very relevant to the needs of statistical learning in higher education [

67,

68].

One of GeoGebra’s primary advantages lies in its capability to process and present data dynamically through real-time visualization. Rather than requiring learners to switch between manual calculation and static display, GeoGebra integrates both processes within an interactive interface. Students can input raw data directly into the spreadsheet view, which is automatically linked to the graphical display. This feature allows immediate transformation of numeric data into visual forms such as histograms, bar charts, pie charts, and boxplots, bridging the gap between quantitative analysis and conceptual understanding. The seamless interaction between data input and visual feedback encourages learners to explore relationships among variables and detect patterns intuitively. Moreover, GeoGebra’s adaptability across multiple data types—categorical, discrete, or continuous—enhances its applicability across diverse statistical topics. Recent pedagogical research highlights that such dynamic visualization environments significantly improve statistical comprehension and analytical reasoning among higher education students [

133].

Interactive data visualization in GeoGebra plays a pivotal role in helping students understand the overall structure and behavior of data distributions. By observing the graphical outputs, learners can easily identify outliers, skewness, and clustering patterns that may not be apparent through numerical summaries alone. This dual approach—numerical computation supported by visual exploration—facilitates deeper engagement with the data. For instance, when a student modifies a data point in the spreadsheet, the associated histogram or boxplot updates instantly, providing immediate visual confirmation of how the change affects the entire dataset. This responsiveness transforms the learning process into an exploratory cycle of hypothesis formation, testing, and reflection. Students begin to see statistical analysis not as a series of isolated steps but as a coherent process of interpretation and meaning-making. Empirical studies have demonstrated that this iterative engagement strengthens students’ inferential thinking and data interpretation skills [

134].

Furthermore, GeoGebra simplifies the calculation and interpretation of key statistical measures such as mean, median, and mode, as well as variance and standard deviation. The integration of computation with visualization allows students to connect abstract numerical results to the graphical characteristics of a dataset, reinforcing understanding of central tendency and variability. When students can visually perceive how dispersion relates to the shape of a histogram or boxplot, statistical formulas gain contextual significance. This integrated process fosters both procedural fluency and conceptual understanding—two competencies that are often taught separately in traditional instruction. GeoGebra’s ability to display intermediate steps in data computation also helps demystify how summary statistics are derived from raw data. Such transparency promotes statistical literacy by enabling learners to trace relationships between numbers and their real-world interpretations. Research confirms that interactive platforms combining visualization and computation improve students’ understanding of statistical measures and their conceptual meanings [

135].

The use of GeoGebra in data processing also nurtures higher-order analytical skills that extend beyond simple calculation. Students learn to interpret statistical results critically, asking

why a particular measure appears and

how it reflects the characteristics of the dataset. This process-oriented approach cultivates analytical habits of mind—students begin to analyze variability, question data sources, and evaluate whether conclusions are supported by empirical evidence. Instructors can leverage GeoGebra to design inquiry-based tasks where students investigate authentic datasets, simulate sampling processes, and justify their interpretations. Such experiences align with the goals of modern statistical education, which emphasize reasoning, communication, and contextual understanding rather than rote computation. Studies from multiple higher education contexts report that the integration of GeoGebra promotes analytical thinking, self-reflection, and data-driven argumentation among university students [

136].

Ultimately, the relevance of GeoGebra in statistical learning derives from its alignment with 21st-century educational needs. The platform supports both digital literacy and data competence, which are essential skills for graduates navigating a data-intensive world. GeoGebra transforms traditional statistical exercises into interactive explorations that mirror the authentic processes of data analysis in research and industry. By combining accessibility, interactivity, and visual feedback, the software promotes equitable participation in statistical reasoning regardless of learners’ prior background or mathematical confidence. Moreover, its integration with web-based environments allows for collaborative learning and knowledge sharing across institutional boundaries. This pedagogical transformation positions GeoGebra as more than a teaching tool—it functions as a catalyst for developing critical, creative, and analytical thinkers in the era of big data. Contemporary studies reaffirm its effectiveness as a digital medium that bridges theory, application, and critical reflection in statistical education [

1,

2,

130].

vi. Discrete and Continuous Opportunity Distribution

The topic of opportunity is one of the important parts of learning statistics which is often considered difficult by students because of its abstract nature. GeoGebra is here to bridge these difficulties by providing opportunity distribution visualization features, both discrete and continuous[

41,

42]. For example, in binomial or Poisson distributions, students can easily manipulate parameters to see how changes in odds occur. Meanwhile, for continuous distributions such as normal or exponential, students can see directly the shape of the curve and the area below the curve that represents a specific opportunity. This visualization process is very helpful for students in understanding the integral concept of continuous distribution and the relationship between parameters and forms of distribution. In other words, GeoGebra allows students to learn more intuitively about opportunities without having to be directly burdened by complex formulas. This is in line with recent research that states that the use of GeoGebra in the topic of opportunity distribution increases students' motivation to learn as well as their ability to relate theory to practice [

34,

35,

36].

The topic of probability, often referred to as

opportunity in certain educational contexts, constitutes one of the most conceptually challenging areas of statistics learning. Many students perceive probability as an abstract and theoretical field due to its reliance on symbolic reasoning, formulaic manipulation, and conceptual generalization. GeoGebra, with its capacity to visualize dynamic mathematical relationships, provides an effective pedagogical bridge to overcome this abstraction. Through its probability distribution visualization tools, the software allows students to interactively explore the behavior of random variables in both discrete and continuous forms. Instead of merely memorizing formulas, learners can directly observe how probability distributions change in response to variations in parameters such as the mean, variance, or rate. This immediate visual feedback transforms the learning of probability from passive memorization into active conceptual inquiry. As several studies confirm, interactive visualization enhances comprehension and helps students internalize complex probabilistic relationships [

136].

GeoGebra enables students to manipulate parameters in discrete distributions such as binomial, geometric, and Poisson models to explore how these parameters influence outcome probabilities. For example, when learners adjust the number of trials or the probability of success in a binomial setting, the shape of the distribution dynamically shifts, revealing the relationship between model parameters and data variability. This interactivity promotes experiential understanding, allowing students to hypothesize and test predictions instantly. The software thus supports an inquiry-based learning model where students construct probabilistic meaning through experimentation and observation rather than through formulaic derivation alone. In doing so, GeoGebra encourages a form of visual reasoning that complements symbolic and numerical approaches traditionally emphasized in probability instruction. Empirical findings suggest that this exploratory experience improves conceptual retention and reduces the cognitive load associated with learning abstract probability formulas [

135].

For continuous probability distributions, GeoGebra’s graphing capabilities further strengthen conceptual understanding by linking algebraic and geometric representations. Students can visualize continuous models such as the normal, exponential, or uniform distributions and dynamically observe how probability density changes with parameter variations. By adjusting the mean and standard deviation, for instance, learners see the normal curve widen or narrow in real time, reinforcing their comprehension of variance and spread. Moreover, the ability to shade the area under the curve directly connects the graphical representation with the integral concept that defines continuous probabilities. This visual approach helps demystify calculus-based reasoning in probability, allowing students to see that the area corresponds to the likelihood of specific outcomes. Consequently, GeoGebra bridges the cognitive gap between symbolic integration and conceptual probability, leading to a deeper, more intuitive grasp of continuous models [

134].

The visualization of probability distributions in GeoGebra also cultivates higher-order cognitive skills such as analytical reasoning, modeling, and interpretation. Rather than focusing solely on procedural accuracy, students engage in reflective thinking—interpreting probability values, identifying relationships between variables, and explaining observed patterns. Such reflective engagement is consistent with constructivist learning theories that view knowledge as actively built through interaction and contextualization. Instructors can further extend this approach by designing problem-based activities in which students simulate random events, compare theoretical and empirical distributions, and evaluate the accuracy of probabilistic models. These learning experiences foster critical thinking and connect abstract probability concepts with real-world data phenomena. Research has shown that using GeoGebra in this way promotes self-directed exploration, deeper metacognitive awareness, and meaningful engagement in learning probability [

133].

Ultimately, GeoGebra’s integration into the teaching of probability aligns with the pedagogical shift toward visualization-based, technology-supported learning in mathematics and statistics education. By enabling intuitive exploration of discrete and continuous distributions, it provides a scaffold that helps students transition from visual understanding to formal reasoning. The dynamic representation of probability fosters not only conceptual mastery but also learning motivation, as students experience a sense of discovery and empowerment in manipulating abstract concepts visually. Furthermore, the tool supports inclusivity in learning by accommodating diverse cognitive styles—particularly for students who struggle with purely symbolic or numerical representations. As recent studies demonstrate, the incorporation of GeoGebra in teaching probability distributions substantially enhances students’ learning outcomes, engagement, and ability to link theoretical knowledge with applied interpretation [

132].

vii. Test Hypotheses with GeoGebra

Hypothesis testing is one of the most challenging materials in statistics because it requires understanding the concept of chances, distribution, and the ability to interpret test results. GeoGebra can help students understand the hypothesis testing process through graphical visualization, for example by displaying the acceptance and rejection regions of the hypothesis at normal distributions [

43,

44]. Students can see how the statistical value of the test compares to the critical value, as well as how the interpretation of the test results is to the null hypothesis. In this way, students not only calculate, but also understand the basic concepts behind statistical decision-making. This visualization helps reduce misunderstandings that often arise, for example regarding the difference between type I and type II errors. Furthermore, students can perform repeated simulations with different data to understand the variations in results that may appear in real research. Thus, GeoGebra is not only a technical tool, but also a pedagogical means to deepen students' conceptual understanding of hypothesis tests [

45,

46,

47].

Hypothesis testing represents one of the most conceptually and procedurally demanding topics in statistics education. Students must comprehend abstract ideas such as sampling distribution, critical regions, significance levels, and error types, which often leads to confusion and cognitive overload. GeoGebra offers an interactive platform that assists students in visualizing the entire hypothesis testing process, from the establishment of hypotheses to the interpretation of statistical outcomes. Through dynamic graphing tools, students can visualize acceptance and rejection regions in normal or

t distributions, observe how test statistics are positioned relative to critical values, and interpret the implications for null and alternative hypotheses. This visualization transforms an otherwise abstract decision-making process into an intuitive and interactive experience. By engaging with these visual models, learners can develop a deeper and more flexible conceptual understanding of inferential reasoning. As demonstrated in recent educational research, interactive simulations in GeoGebra significantly improve students’ comprehension of hypothesis testing principles [

131].

The use of GeoGebra in hypothesis testing instruction bridges the gap between procedural calculations and conceptual understanding. Rather than focusing solely on formulaic operations, students are guided to visualize the logic behind the testing process. For instance, by graphically representing the

p-value area under the curve, learners can immediately grasp its relationship to the chosen significance level. Similarly, by altering sample size or standard deviation, students can observe how the shape of the sampling distribution changes and how that affects test sensitivity. These manipulations help internalize critical inferential concepts, including power and variability, through exploration rather than rote computation. The real-time feedback provided by GeoGebra also supports formative assessment, allowing instructors to identify misconceptions as they emerge during learning activities. This form of visual inquiry learning aligns closely with the constructivist approach to teaching statistics [

130,

131].

A particularly important advantage of using GeoGebra in hypothesis testing lies in its ability to clarify the distinctions between type I and type II errors—two areas that consistently cause confusion among students. By illustrating the overlap between distributions representing true and false hypotheses, the software makes visible how α (alpha) and β (beta) relate to one another in determining the accuracy of statistical decisions. This visualization allows students to see how reducing one type of error inevitably increases the other, helping them appreciate the trade-offs involved in real-world statistical inference. Through repeated simulations, learners can also experiment with different critical values or significance thresholds to observe their effects on rejection regions and decision outcomes. Such explorations transform static statistical ideas into dynamic cognitive experiences that foster analytical reasoning. Evidence suggests that when hypothesis testing is taught through dynamic visualization, students achieve significantly higher conceptual retention [

128,

129].

Moreover, GeoGebra provides opportunities for students to perform virtual experiments and sampling simulations that reinforce the relationship between empirical and theoretical results. By generating multiple random samples and performing automated tests, learners observe how test statistics fluctuate across samples and how conclusions vary in response. This experiential learning connects the logic of hypothesis testing with real research contexts, demonstrating the probabilistic nature of statistical inference. The iterative process of simulation also promotes metacognitive reflection, as students evaluate their understanding of variability, error, and confidence levels. In this way, GeoGebra supports the development of statistical literacy—helping students transition from procedural competence to interpretive expertise. Research in technology-enhanced statistics education highlights this as a key factor in improving reasoning and critical thinking [

127].

Ultimately, GeoGebra should be seen not merely as a computational aid, but as a pedagogical framework that transforms how students learn hypothesis testing. It shifts emphasis from symbolic manipulation toward visual reasoning, conceptual clarity, and analytical dialogue. Students actively construct meaning by linking graphs, numbers, and conceptual inferences, leading to deeper understanding and longer knowledge retention. Furthermore, GeoGebra encourages collaborative exploration, allowing students to share and discuss visual results that support their arguments in a data-driven way. This approach resonates strongly with current trends in digital mathematics education that value interactivity, inquiry, and visualization as central components of effective learning. Recent empirical studies affirm that GeoGebra-based learning significantly improves motivation, comprehension, and inferential reasoning accuracy in hypothesis testing tasks [

126].

viii. Collaboration and Exploration through GeoGebra

In addition to being used individually, GeoGebra also supports collaborative learning. Students can work in small groups to solve specific statistical problems using GeoGebra, then discuss the results of their exploration. The sharing feature in GeoGebra allows students to exchange files or projects, thus enriching the learning process through discussion and comparison. This approach is in line with social learning theory which emphasizes the importance of interaction and communication in building knowledge. In this way, students not only learn statistical concepts, but also develop scientific communication skills and teamwork. Recent research shows that collaboration-based learning with GeoGebra is able to improve students' problem-solving skills and strengthen their confidence in dealing with statistical problems [

3,

45,

46].

Collaborative learning has become a cornerstone of contemporary educational practice, emphasizing interaction, communication, and shared meaning-making. Within this pedagogical framework, GeoGebra serves as an ideal platform for promoting collaboration in statistical learning. Its dynamic and interactive interface allows students to collectively manipulate mathematical and statistical representations, fostering active engagement and cooperative problem-solving. By working together on a shared GeoGebra project, students exchange perspectives and discuss alternative solutions, thereby enhancing conceptual understanding through social negotiation. This process aligns with Vygotsky’s social constructivist principles, which posit that learning occurs most effectively through social interaction and scaffolding among peers. The visual and interactive nature of GeoGebra facilitates these processes by providing a shared representational space where ideas can be made explicit and compared. Research has shown that such collaborative visualization enhances collective reasoning and supports deeper comprehension of complex concepts [

125].

The sharing and cloud-based collaboration features of GeoGebra extend learning beyond the confines of the traditional classroom. Students can create, upload, and share interactive applets or statistical models, enabling asynchronous collaboration and continuous discussion. This feature supports the development of both individual and collective competencies, as learners can analyze peers’ work, provide feedback, and refine their own ideas in response. Moreover, instructors can monitor collaborative activities, offering targeted guidance and formative assessment based on real-time student interactions. The process of co-constructing mathematical knowledge within a digital environment encourages reflective learning and critical thinking, as students must articulate their reasoning clearly to others. Such peer-to-peer exchanges also promote inclusivity, as students with different levels of proficiency can support each other’s progress. Studies confirm that digital collaboration through GeoGebra fosters social presence and academic engagement in virtual and blended learning environments [

124].

Collaborative use of GeoGebra also cultivates important soft skills such as teamwork, communication, and digital literacy—competencies increasingly valued in modern education and professional contexts. When students collectively engage in solving statistical problems, they must negotiate roles, distribute tasks, and synthesize findings into coherent conclusions. This collaborative dynamic mirrors authentic professional research practices where data analysis is often a group endeavor. Through this process, learners not only gain technical proficiency in statistical computation but also develop communication skills required to explain, justify, and defend their analytical conclusions. The process of articulating reasoning in front of peers enhances metacognitive awareness and consolidates conceptual understanding. Furthermore, the shared digital workspace in GeoGebra ensures that each group member contributes meaningfully to the task, reinforcing accountability and interdependence. Recent empirical evidence shows that such collaborative learning experiences improve both cognitive achievement and interpersonal skill development in statistical education [

123].

From a pedagogical perspective, collaboration-based learning through GeoGebra aligns with the principles of inquiry-based learning, where knowledge is built collectively through exploration, questioning, and discussion. The software’s interactive tools enable students to test hypotheses, visualize statistical data, and interpret findings as a team, thus promoting a deeper and more socially mediated learning experience. This communal construction of knowledge transforms statistical learning from a passive activity into an active inquiry process. Moreover, the availability of real-time feedback and graphical visualization supports evidence-based reasoning within group discussions. Students become co-investigators who collaboratively interpret and validate data-driven conclusions. This approach encourages the development of epistemic beliefs about mathematics as a dynamic and collaborative discipline rather than a fixed set of procedures. Studies have found that collaborative inquiry using GeoGebra enhances students’ confidence, motivation, and statistical reasoning skills [

122].

Ultimately, GeoGebra’s collaborative capabilities not only enhance the mastery of statistical content but also cultivate 21st-century skills essential for lifelong learning. The integration of communication, critical thinking, creativity, and collaboration into the statistical learning process reflects the broader educational goal of producing adaptive and innovative thinkers. By engaging in shared explorations, learners experience how technology can mediate cooperation and co-construction of knowledge. The open-ended nature of GeoGebra activities allows for flexibility and personalization within teamwork, ensuring that each participant’s contribution shapes the collective outcome. Moreover, the transparent and replicable nature of shared GeoGebra projects encourages scientific rigor and accountability, as group outputs can be revisited and refined. As highlighted in recent studies, GeoGebra-supported collaboration has been shown to significantly enhance engagement, performance, and self-efficacy in mathematical problem-solving tasks [

121].

ix. Challenges and Limitations of Using GeoGebra

While GeoGebra has many advantages, there are also some challenges in its use in statistical learning. One of the main challenges is the limited digital literacy of some students who are still not used to using technology-based applications. Additionally, some GeoGebra features may require further adjustment to suit the needs of advanced statistical analysis. Lecturers also need to spend additional time to design learning activities that are in accordance with the use of GeoGebra. However, this challenge can be overcome with initial training, both for lecturers and students, as well as by providing clear practical guidance. Over time, these limitations will diminish as the user experience in using the app improves. In fact, some studies have stated that students who initially had difficulty using GeoGebra were finally able to master it well and feel more confident in doing statistical assignments [

64,

65].

While GeoGebra offers numerous pedagogical advantages in facilitating interactive and conceptual learning, its integration into statistical education is not without challenges. One of the most pressing issues is the digital divide that persists among students and instructors, particularly in developing contexts. Limited exposure to technology and insufficient digital literacy can hinder effective use of GeoGebra’s features. Students who are unfamiliar with interactive tools may struggle to navigate the software or misinterpret visualizations, thereby reducing learning efficiency. This limitation is especially evident in cohorts where technology integration in mathematics education remains at an early stage. Furthermore, lecturers may face difficulties when adapting traditional lesson plans into digitally enriched activities that align with GeoGebra’s constructivist approach. These challenges underscore the need for strategic capacity-building programs that equip both educators and learners with the necessary skills to maximize the pedagogical potential of digital platforms. As pointed out by Pratama (2021), the success of digital learning environments largely depends on sustained digital readiness and institutional support structures.

Another significant challenge lies in the customization of GeoGebra features for advanced statistical analysis. Although GeoGebra has evolved beyond geometry and calculus into statistical modeling, some complex analyses—such as multivariate regressions or inferential hypothesis testing—may still require integration with specialized software such as R or SPSS. Consequently, educators often need to design hybrid learning environments that combine GeoGebra’s visual strengths with the computational rigor of other tools. This process requires technical expertise and pedagogical creativity, as lecturers must align software functionalities with intended learning outcomes. However, this challenge also presents opportunities for cross-software literacy, allowing students to experience how visual analytics and statistical programming complement one another. The interdisciplinary integration of GeoGebra within broader analytical ecosystems encourages students to approach data analysis holistically, bridging conceptual understanding with computational application. Studies have highlighted that effective orchestration of multiple technologies can significantly enhance the depth of statistical reasoning and applied data literacy [

120].

The time investment required for educators to prepare GeoGebra-based lessons is another recurrent concern. Designing interactive statistical activities demands not only conceptual mastery but also technical fluency in manipulating the software. Instructors must anticipate potential misconceptions, construct dynamic worksheets, and ensure that simulations align with curricular objectives. Such preparation may initially appear time-consuming, particularly for lecturers balancing teaching, research, and administrative duties. However, once developed, these learning modules can be reused and shared among peers through online repositories, amplifying their impact across institutions. This collaborative approach aligns with open educational resource (OER) principles, fostering academic sharing and innovation. Moreover, institutional support in the form of workshops and professional development programs can reduce individual workload and accelerate pedagogical adaptation. Research suggests that teacher professional learning communities play a crucial role in promoting long-term sustainability of technology integration [

119].

To address the aforementioned barriers, structured digital training for both lecturers and students is imperative. Orientation sessions that introduce GeoGebra’s key functionalities and pedagogical affordances can significantly improve users’ confidence and motivation. Clear instructional scaffolding—such as video tutorials, guided worksheets, and task-based exercises—enables smoother transitions from traditional to technology-enhanced learning. In addition, incorporating reflective discussions about the role of visualization and interactivity in learning helps students develop metacognitive awareness of how tools shape understanding. The iterative practice of applying GeoGebra in progressively complex statistical tasks allows learners to build fluency over time. Institutions that integrate these support mechanisms within their curricula have reported higher adoption rates and more positive student attitudes toward digital learning. Recent studies emphasize that early-stage digital mentorship reduces technology-related anxiety and enhances academic engagement in STEM contexts [

118].

Despite the initial learning curve, evidence shows that with consistent practice and guided instruction, both educators and students adapt successfully to using GeoGebra in statistical contexts. Learners who initially faced difficulties navigating the interface eventually reported greater satisfaction and self-efficacy in handling data-driven tasks. Over time, familiarity with the platform transforms apprehension into empowerment, as students gain autonomy in exploring mathematical models and statistical relationships. This progressive mastery supports lifelong digital competence, preparing learners for future data-intensive careers. The transformative potential of GeoGebra thus extends beyond mathematics classrooms, contributing to digital literacy and analytical thinking more broadly. As educators refine their methodologies and technological fluency improves, the early challenges of adoption are likely to diminish substantially. Empirical studies have consistently found that sustained use of GeoGebra leads to enhanced motivation, confidence, and conceptual retention in mathematical and statistical learning [

115,

116,

117].

Overall, GeoGebra is proving to be one of the most relevant and effective applications to use in statistical learning in college. This application not only helps students in solving technical problems, but also supports a deeper conceptual understanding. With interactive visualizations, GeoGebra bridges the gap between abstract theory and real practice, and encourages the 21st-century skills students need. The use of GeoGebra in the topics of data presentation, opportunity distribution, and hypothesis testing shows great potential in improving the quality of statistical learning. [

62,

63] Despite the limitations, the benefits provided are much greater, especially in the context of the digital transformation of education in the 2020–2025 period. Therefore, the integration of GeoGebra in statistics learning needs to be expanded in order to make maximum contributions to improving the quality of mathematics and statistics education in Indonesia [

5,

6,

7].