1. Introduction

Pepper plants, belonging to the genus

Capsicum of the Solanaceae family, are vegetables that stand out for their phenotypic characteristics. The structure of the plants, the morphology of the flowers, and the diversity of shapes and colors of the fruits, in addition to other aesthetic attributes, generate growing interest in this crop, showing great potential for development as ornamental plants [

1]. In Brazil, the ornamental plant sector has contributed significantly to the economy. It has gained prominence over the years, generating around R

$19.8 billion, creating more than 800,000 indirect jobs and 272,000 direct jobs, involving approximately 8,300 producers in a cultivated area of 15,600 hectares [

2]. These data show a growing demand for varieties with high aesthetic value and good adaptability to different cultivation conditions.

However, water stress, often associated with high temperatures, is the environmental variable that most affects crops [

3]. This problem is further aggravated by global warming and climate change, which expose the varieties to abiotic and biotic stresses, compromising initial growth and, consequently, productivity [

4]. In Iran, under controlled conditions, when applying 80%, 60%, and 40% of the water requirements for

Capsicum annuum plants, observed a reduction in yield of 29.4%, 52.7%, and 69.5%, respectively [

5]. In the work by Molla et al. [

6], a significant reduction in the length of pepper cultivars was observed compared to the control group as a consequence of water stress. In the initial and reproductive stages, pepper plants are more susceptible to stress caused by drought [

7]. Bernau et al. [

8], by inducing water stress conditions, observed a slower and, in some cases, incomplete germination process in chili pepper (

Capsicum spp.) seeds. To meet the demands of the ornamental sector, the selection of genotypes that are more tolerant to water stress is essential for the development of new cultivars [

2].

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is a compound commonly used to simulate water stress (drought) conditions in mainly controlled environments. Its application allows for the assessment of crop tolerance to water scarcity, which contributes to the selection of better-adapted varieties [

9]. Recent studies have shown great variation in the germination and initial growth of pepper plant accessions from various species (

Capsicum annuum L.,

C. frutescens L., and

C. chinense Jacq.) when subjected to concentrations of PEG [

8,

10,

11]. These authors examined the influence of genotype and the collection site of the germplasm on drought stress tolerance. In this sense, there is no consensus on critical levels of stress induced by PEG in vitro and studies using PEG in the selection of pepper germplasm for ornamental use have not yet been verified.

Researchers used PEG to induce different levels of water stress during the germination of the ornamental plant

Alcea rosea, allowing for the assessment of morphological, physiological, and biochemical changes [

12]. In this study, the authors concluded that the compound is effective for simulating water stress under controlled conditions, aiding in the selection of more drought-tolerant ecotypes even in the initial development phase. This reinforces the importance and efficiency of the technique for selecting tolerant accessions in breeding programs for ornamental plants.

This study is predicated on the hypothesis that moderate concentrations of PEG inhibit germination and initial growth while inducing stomatal modifications in Capsicum. However, the extent of these effects varies among different accessions. Given the necessity to identify accessions with tolerance to water stress at an early stage, this approach offers a reduction in both time and cost compared to traditional field trials. In this context, the present study aimed to evaluate germination, initial growth, and stomatal characteristics of ornamental pepper (Capsicum spp.) accessions subjected in vitro to different levels of water stress induced by PEG 6000.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Vegetal Material

In this study, seven accessions of pepper plants (

Table 1) with ornamental potential were used, previously selected based on earlier studies. These accessions are stored in the Active Germplasm Bank of the Federal University of Piauí, Professora Cinobelina Elvas Campus in Bom Jesus-Piauí- Brazil.

2.2. Seed Preparation and Inoculation

Five concentrations of PEG 6000: 0% (control), 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%, were added to the culture medium to simulate in vitro water stress conditions. The culture medium used in the study was the Murashige & Skoog (MS) medium [

13] (Sigma Alderich

®, St. Louis, Missouri, EUA) and consists of macronutrients, micronutrients, and vitamins. Sucrose was added to the medium (Dinâmica

® ,Indaiatuba, São Paulo, Brazil) (30g L

-1) and polyethylene glycol (PEG) (Dinâmica

®,Indaiatuba, São Paulo, Brazil), with concentrations according to the treatment. 8 g L

-1 of agar (Mericlone Biotecnologia, Holambra, São Paulo, Brazil) were also added, and the medium pH was adjusted to 5.8 using 0.1 N NaOH and 0.1 N HCl solutions. After preparation, the medium was distributed into glass jars containing 40 mL of medium each, totaling four jars per concentration. The jars were organized in plastic bags and were then autoclaved at 120°C±2°C and pressure of 1kgf/cm

2.

The seeds of each accession were disinfected in a laminar flow chamber using a 1:1 solution (v/v) of distilled water and sodium hypochlorite for 10 minutes. After disinfestation, three seeds from each accession were inoculated into each pot containing culture medium. The material was kept in a growth room at 25°C ± 2°C and under 2,400 lux illumination from fluorescent lamps, with a 12:12h photoperiod. The experiment was conducted in a completely randomized design in a 5 x 7 factorial scheme (PEG concentrations x accessions) with four replications, each containing three seeds in each.

2.3. In Vitro Germination

Germination was evaluated daily for 20 days, always in the afternoon, completing 24 hours after inoculation. A seed was considered germinated when there was a protrusion of the radicle, according to the guidelines established by the reference “Regras para Análise de Sementes”

[16].

In addition, the germination rate was calculated based on the number of inoculated seeds over the total and the germination speed index (GSI), following the formula proposed by Maguire [

14]:

where:

= number of germinated seeds on i-th day

= i-th day at which counting is being made

2.4. Seedling Morphology Assessment

The growth of pepper seedlings was observed 35 days after the seeds were inoculated in a medium with different concentrations of PEG. At this point, the seedlings were in the vegetative stage and had developed approximately six true leaves. For this, two seedlings, randomly selected from each replicate, were evaluated. The length of the shoot and the root (mm) was measured using a digital caliper (Pantec

®). The fresh and dry weight (g) of the aerial part and the root were determined using a precision balance (Bel engineering

®, model s203). Soon after, the aerial part and the root were placed in properly labeled paper bags and set to dry in a drying oven (Tecnal

®, model TE-394/2) at 60°C until constant weight was achieved, the dry weight of the shoot and the root was then determined. The dry matter content in the aerial part and in the root were calculated based on the following expression:

2.5. Stomatal Assessment

The stomatal evaluations were carried out with the aid of a trinocular microscope (Leica® DM2500) with 400x magnification equipped with a digital color camera system (Leica®, DFC700T). For this procedure, leaves were removed from seedlings 35 days after inoculation in order to assess their stomata. The adaxial side of four leaves/treatment was glued onto the slide for 5 minutes with glue (tekbond®, Embu das Artes, São Paulo, Brazil) until the impression was made. The measurements were taken with the aid of the Leica LAS interactive measurements module, using the ruler tool. Two stomata per leaf were randomly measured for the length (SL) and width (SW) of the stomata (µm), drawing a straight line along the longest axis of the stoma, from the end of one guard cell to the other, and the diameter by drawing a straight line across the opening (ostiole), measuring the width of the central region of the stoma, then it was calculated the ratio between length/width of the stomata (SL/SW). Stomata midpoint length (SML) (µm) and stomata midpoint width (SMW) (µm), were measured in the internal region of the stomata, by drawing a straight line in the longitudinal and transverse directions of the ostiole, respectively. The number of stomata in an area of 0.29mm² for the calculation of stomatal density as number of stomata per area unit (number of stomata per mm²).

The evaluation of stomata was carried out for the accessions CPCE 005, CPCE 007, CPCE 010, and CPCE 011, at two PEG concentrations (0% and 5%). A completely randomized design was used, in a 2 x 4 factorial scheme (concentration x accessions) using four repetitions (four leaves).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All data processing, analyses, and classifications were performed in R v4.0.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the package easyanova [

15]. The homogeneity of variances was verified by the Bartlett test and the normality of the residuals by the Shapiro-Wilk test. When the assumptions were met, the means of the factors - accessions, PEG concentrations, and interaction - were compared using Tukey's test (p < 0.05). For the variables whose assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity were not met, the analysis was performed using generalized linear models (GLM), selected based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC) [

16]. The model with binomial distribution was used for the germination variable; the model with Inverse Gaussian distribution for the percentage of shoot dry matter; and the model with Gamma distribution for the percentage of root dry matter. For the stomatal variables, the Gamma model was used for density and Inverse Gaussian for SL/SW. Significant differences between factors and interaction for the GLM models were compared by Tukey’s tests (p < 0.05) with confidence intervals adjusted by the Šidák method using the ‘emmeans’ function in the multcomp.

3. Results

3.1. Influence of Water Restriction on Seedling Germination and Morphology

The high concentrations of PEG tested completely inhibited germination in ornamental pepper accessions. Germinated seeds and developed seedlings were observed only in the control treatment (0% PEG) and at the 5% concentration. Therefore, in the analyses carried out in this study, only two PEG concentrations were considered.

Germination, germination speed index (GSI), length of the aerial part (AL), root length (RL), percentage of dry matter in the aerial part (ADMP) the percentage of dry matter in the root (RDMP) are parameters that explain the significant effects (p<0.05) observed between the accessions and the PEG concentrations (

Table 2). The results indicate that both the accessions and the concentrations of PEG significantly influenced the evaluated parameters.

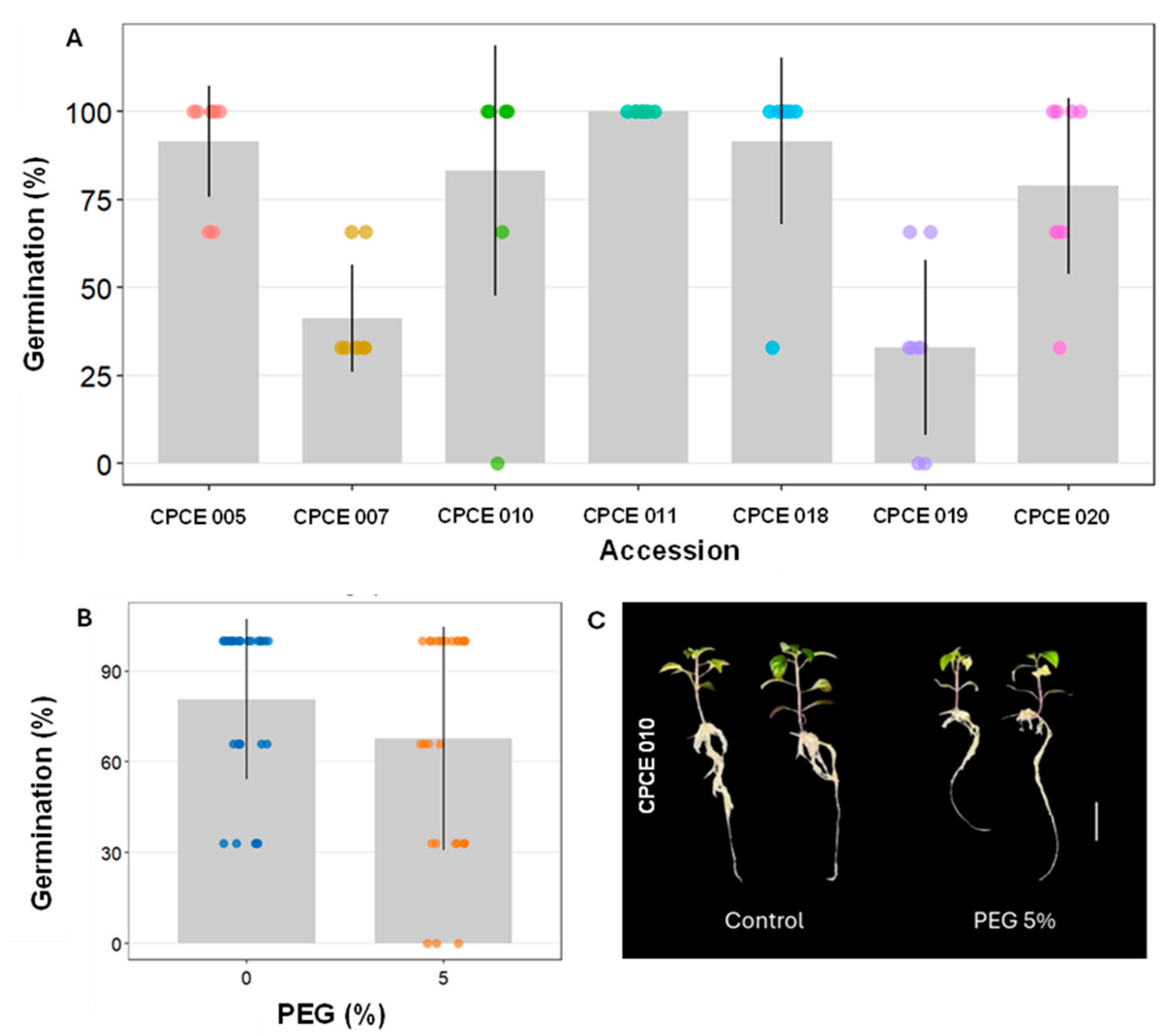

Germination was strongly influenced by the genotypic factor and the PEG concentration (5%), with the CPCE 011 accession showing superior performance, reaching 100% germination, followed by CPCE 018 (91.62%), CPCE 005 (91.5%), and CPCE 010 (83.25%), which did not differ from each other (

Figure 1A). On the other hand, the CPCE 007 and CPCE 019 accessions showed the lowest germination rates, with only 41.25% and 33%, respectively.

The water restriction simulated by PEG reduced the germination percentage regardless of the accessions (

Table 2 and

Figure 1B). The average germination in the control treatment of 80.75% dropped to 67.67% at the 5% PEG concentration, a reduction of approximately 13.1%. It can be observed that water restriction influenced germination; however, it did not alter the germination speed (GSI), as no differences were observed between the PEG concentrations (

Table 2). However, the effect of genotype was significant (

Table 2). Accessions CPCE 018 (0.29±0.03) and CPCE 020 (0.26±0.04) showed higher GSI values compared to the other accessions, regardless of PEG concentration.

Regarding the length of the shoot length (SHL), there was a significant difference between the accessions evaluated independently, with CPCE 020, CPCE 010, CPCE 011, and CPCE 018 showing, respectively, more developed seedlings, which may indicate good tolerance (

Table 2). A significant interaction effect was also observed (

Table 2 and

Table 3). Considering the PEG concentration of 0%, once again the accessions CPCE 10, CPCE 11, CPCE 18, and CPCE 20 showed seedlings with greater length of the aerial part. Under water restriction conditions (5% PEG), the CPCE 010 and CPCE 020 accessions stood out. It is important to emphasize, however, that the CPCE 010 accession was strongly influenced by the PEG dose, with a reduction of approximately 10 mm in shoot length at the 5% concentration (

Table 3 and

Figure 1C). No significant reductions were observed between the two concentrations for the other accessions.

When observing RL development, the accession CPCE 005 stood out with the greatest average length (124.16±28.7), followed by accessions CPCE 007 and CPCE 010 (

Table 2). On average, the water restriction imposed by PEG did not influence the root length of the seedlings.

Regarding dry matter percentage, differences were observed among the accessions (

Table 2). Accessions CPCE 007, CPCE 010, CPCE 011, and CPCE 019 showed the highest average percentages. It is important to highlight accession CPCE 020, which showed seedlings with greater shoot length but low dry matter percentages. The accessions did not influence the dry matter percentage of the root. There was an effect of PEG concentrations on the ADMP and RDMP, with higher percentages observed at the 5% PEG concentration, suggesting possible physiological adaptation mechanisms of the seedlings induced to water stress (

Table 2).

3.2. Stomatal Characteristics

Significant changes were observed in the stomatal characteristics of the seedlings in response to the different accessions and PEG concentrations, and an interaction effect was observed for stomatal density, stomatal length, midpoint length, and midpoint width (

Table 4).

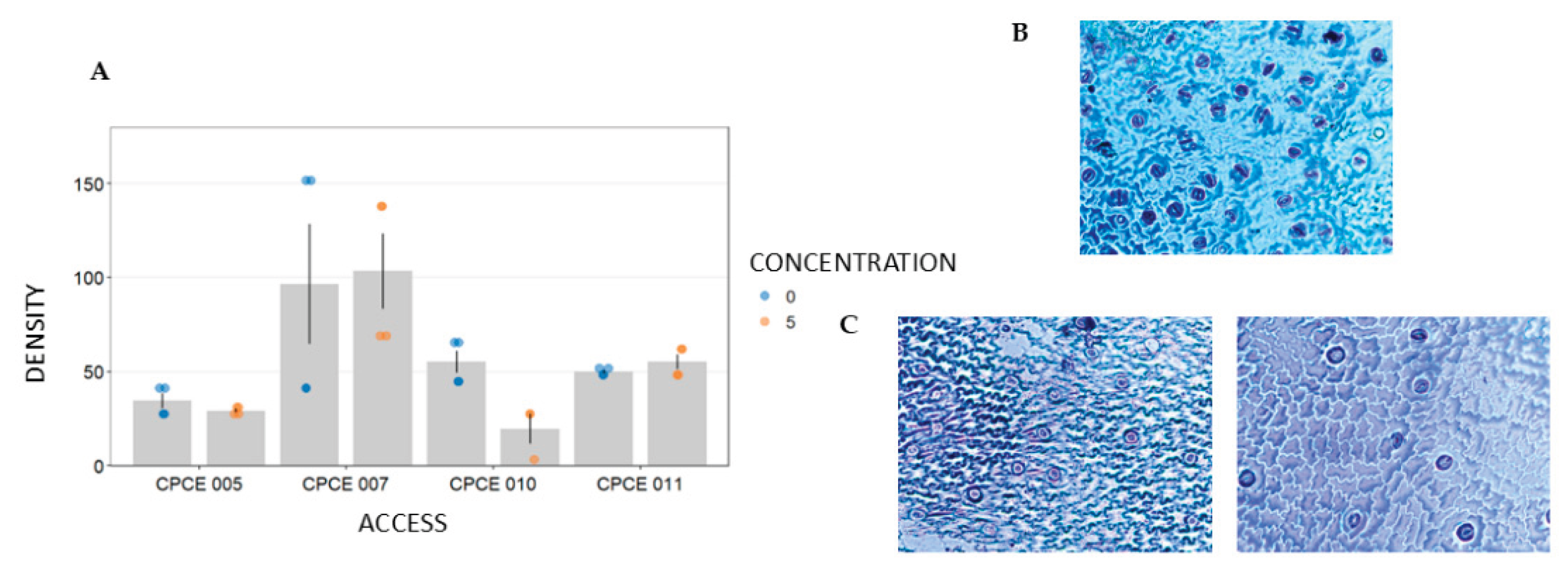

Stomatal density varied significantly among the accessions (p < 0.001) and in interaction with PEG (p = 0.01), with the CPCE 007 accession showing the highest number of stomata per area (99.9±49.32) (

Table 2 and

Figure 2A and 2B).

Considering the interaction, under the control condition (0% PEG), there was no difference in stomatal density among accessions CPCE 007, CPCE 010, and CPCE 011 (

Table 5). Under water restriction (5% PEG), accession CPCE 007 does not differ from accession CPCE 011. Although the means observed are much higher for accession CPCE 007, greater data variability was observed, as reflected by the standard deviation (

Figure 2A). In both conditions, accession CPCE 005 showed lower stomatal density. When comparing the effect of water restriction simulated by PEG, a reduction in stomatal density was observed for Accession CPCE 010 (

Figure 2C). The stomatal density of 55.2±11.94 observed at the 0% PEG concentration decreased to 19.5±13.9 in the 5% PEG treatment. The other accessions maintained stability under both conditions.

The stomatal length (SL) and stomatal width (SW) did not show significant differences between the accessions or between PEG concentrations. However, a significant interaction between the two factors was observed for length (

Table 4). The accession CPCE 007 showed a reduction in SL (25.08 ± 1.17) with increasing PEG concentration, while the accession CPCE 010 demonstrated an increase in stomatal length (30.83 ± 6.29) under stress conditions (

Table 5).

The mid-point length (SML) and mid-point width (SMW) proved to be sensitive to stress, with significant effects from the interaction and access (

Table 4). A reduction in mid-point length (17.90±2.59) was observed for accession CPCE 007 when subjected to water stress, while CPCE 005 and CPCE 010 stood out, with an increase in this variable under the same conditions (

Table 5). Accession CPCE 011 showed a significant reduction in mid-point width under the 5% PEG concentration (

Table 5), indicating a possible physiological mechanism of the seedling to minimize water loss through transpiration. For the other accessions, no significant differences were observed between the two conditions. The SL/SW ratio, which is related to the diameter/shape of the stomata, did not show significant differences in any of the factors, nor in the interaction between factors.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Water Stress on Seed Germination Characteristics and Seedling Vigor

This study revealed that certain accessions of

Capsicum have low osmotic tolerance, reinforcing a strong genotypic control and expanding knowledge about the little-studied intraspecific variability in ornamental peppers. PEG concentrations above 5% completely inhibited seed germination. Many

Capsicum cultivars germinate under PEG between 10–20%, with gradual reductions [

7,

8], but not with completely inhibited germination as observed in this work. In the genus

Capsicum spp., seed germination is usually evaluated after 14 days [

17]. In this study, the evaluations were conducted over a period of twenty days in order to better describe the influence of PEG concentrations on the germination process. The stress simulated by PEG reduces the seed’s ability to absorb water due to an osmotic effect [

18,

19]. Keeping seeds in a non-germinated state during periods of drought can allow plants to escape dehydration, one of the strategies used by species for drought resistance [

20,

21].

The results indicated that germination, subjected to a 5% PEG concentration, was reduced to 67.67±36.92% compared to the control (80.75±26.53) (

Table 2), confirming the inhibitory effect of simulated water stress on pepper seed germination

(Capsicum spp.). Similar results were obtained by Gangotri et al. [

7]

, who observed a significant reduction in the germination percentage of pepper genotypes with the increase in PEG 6000 concentrations. In the same way, Wickramasinghe & Seran [

22]

evaluated drought stress tolerance in tomato seedlings, which belong to the same family as pepper plants (Solanaceae), and observed significant losses in the germination rate. However, in the present study, some pepper plant accessions maintained high germination rates when compared to the tomato seedlings (Solanum lycopersicum L.) in which germination was below 60% [

22]

.

In this sense, accessions that maintained a high germination rate regardless of the conditions tested are important in breeding programs, as they exhibit tolerance to water restriction. The accessions CPCE 011, CPCE 005, and CPCE 018 show germination rates above 90%. An expected trait of high-quality seeds is the ability to germinate under adverse growth conditions. Rapid germination and emergence are essential for the successful establishment of crops [

23].

The significant interaction for the shoot length of the seedlings reveals the differential response of the accessions (genotype effect) to environmental variations, in this study imposed by the concentrations of PEG. Only the accession CPCE 010 (

Table 3) had its seedling length reduced by water restriction, demonstrating tolerance among the accessions tested. The reduction of external water potential triggers several important events in plant tissues.

For example, at the macroscopic level, osmotic stress inhibits cell growth due to the decrease in turgor pressure [

24]

, what can explain the variability between the accessions, as indicated by the standard deviations associated with the averages of the shoot length.

Root growth was not influenced by PEG concentrations. In the face of osmotic stress, plants maintain root growth and reduce shoot growth, especially in the early stages of development [

25]. The optimized architecture of the root system can strengthen the properties of plants facing drought stress, including root length and number, to increase the absorption of deeper water sources, ultimately enhancing drought tolerance [

26]. In this way, accessions with more developed roots may show greater tolerance under water-restricted conditions, as seen in accessions CPCE 005, CPCE 007, and CPCE 010.

In the variables of percentage of shoot dry matter (ADMP) and percentage of root dry matter (RDMP), the treatment with PEG promoted a significant increase. Demir & Mavi [

18] also observed that, in contrast to the decrease in fresh weight, the seedling's dry weight increases as stress concentrations rise. This result suggests that although stress inhibits germination and initial growth, it may induce adaptation mechanisms at the metabolic level, such as the partitioning of biomass to the shoot and root of the seedling. Sané et al. [

27] used as one of the parameters for evaluating drought stress tolerance in tomatoes (

Solanum lycoperiscum L.) the accumulation of proline by the seedlings, using the colorimetry method proposed by Monneveux & Nemmar [

28]. The accumulation of this compound can be considered a plant response to water stress. Therefore, in future research, it is recommended to quantify proline in order to verify possible relationships between this biomass accumulation and the significant results observed for the percentage of dry matter.

4.2. Stomatal Characteristics in Response to Water Stress

By integrating the analysis of stomata, it was found that they act as sensitive markers of stress tolerance in ornamental pepper plants, especially in the measurements of the mid-point (SML and SMW). The reduction in stomatal aperture and, in some cases in stomatal density, indicated physiological adjustments to reduce water loss, which are characteristic of drought responses. These changes in the length and width of the mid-point have not yet been described for ornamental pepper plants, and this response was genotype-dependent. Stomata are essential structural features of most plants; they play a crucial role in gas exchange, photosynthesis, and transpiration in plants in general [

29]. Studies explore stomatal behavior in response to water stress and environmental changes [

30].

Stomatal density varied significantly among the accessions (p < 0.001), with accession CPCE 007 standing out compared to the others due to its higher number of stomata/area, highlighting the variability among the accessions (

Figure 2). A higher stomatal density may be associated with a greater ability of the plants to capture CO

2 from the atmosphere and, consequently, increase photosynthetic efficiency [

31].

Different from the results found in this work, Syafriani et al. [

11] did not observe differences in the number of stomata, but they did observe variation in length and width, emphasizing the genotypic effect as an adaptation mechanism. There was no significant effect of PEG 6000 on stomatal length (SL) or width (SW), nor on mid-point length (SML) (p > 0.05), however, an effect of the accession was observed, corroborating the results for pepper plants reported by Syafriani et al. [

11]. The midpoint width (SMW) was significantly reduced by the application of 5% PEG (p = 0.04). This response is consistent with a plant defense mechanism under water deficit stress conditions, through the closing or fine adjustment of stomatal opening [

29]. The reduction in SMW can decrease water loss through transpiration, representing an important stress tolerance strategy.

The significant interaction between accession and PEG concentration for SL (p = 0.03), SML (p < 0.001), and SMW (p = 0.04) reinforces that the response of stomatal morphology to water stress depends on the genotype. This genetic variability is valuable for breeding programs, as genotypes capable of maintaining functional stomata under stress may exhibit better physiological performance under drought conditions. The SL/SW ratio, which is associated with stomatal shape, was not significantly affected by any of the factors studied (p > 0.05), suggesting that stomatal shape is a stable structural characteristic in pepper plants, less susceptible to changes resulting from water stress. Higher values of this ratio indicate greater stomatal functionality due to their ellipsoid shape [

31].

5. Conclusions

In this study, unlike previous articles with Capsicum, no germination was observed at PEG concentrations higher or equal to 10%. Furthermore, water stress induced by PEG significantly impacted germination, the percentage of shoot and root dry matter, and the width of the stomata mid-point. The accessions CPCE 020, CPCE 018, and CPCE 011 exhibited more characteristics of tolerance to water stress, demonstrating great potential for selection in breeding programs. CPCE 019 was the most susceptible to water stress. The results of this work can guide breeding programs for the selection and improvement of tolerant genotypes, aiming at the development of ornamental pepper varieties. It is suggested that further studies be conducted to evaluate the performance of these accessions under greenhouse conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A.B. and A.M.M.N.; methodology, P.A.B, AM.M.N, S.C.S; software, A.M.M; P.A.B; formal analysis, AM.M., PA.B.; investigation, M.C.A.R, P.S.R.; resources, PA.B.; data curation, M.C.A.R., P.S.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.A.R., P.A.B; writing—review and editing, R.R.G., A.M.M.N.; supervision, P.A.B.

Funding

This research was funded by CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e.Tecnológico), grant number 408444/2021-5.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Laboratory Technician Dr. Roberta Menezes Santos for her support in the development of protocols and equipment calibration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADMP |

Aerial Dry Matter Percentage |

| AGB |

Active Germplasm Bank |

| AL |

Aerial length |

| CPCE |

Campus Professora Cinobelina Elvas |

| GSI |

Germination Speed Index |

| PEG |

Polyethylene Glycol |

| RDMP |

Root Dry Matter Percentage |

| RL |

Root length |

| SL |

Stomatal Length |

| SML |

Stomata Midpoint Length |

| SMW |

Stomata Midpoint Width |

| SW |

Stomatal Width |

References

- Tripodi, P.; Kumar, S. The Capsicum Crop: An Introduction. In The Capsicum Genome; Ramchiary, N., Kole, C., Eds.; Compendium of Plant Genomes; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-3-319-97216-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ibraflor Instituto Brasileiro de Floricultura. 2024.

- Ding, Y.; Yang, S. Surviving and Thriving: How Plants Perceive and Respond to Temperature Stress. Dev. Cell 2022, 57, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramegowda, V.; Senthil-Kumar, M. The Interactive Effects of Simultaneous Biotic and Abiotic Stresses on Plants: Mechanistic Understanding from Drought and Pathogen Combination. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 176, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardani, S.; Tabatabaei, S.H.; Pessarakli, M.; Zareabyaneh, H. Physiological Responses of Pepper Plant ( Capsicum Annuum L.) to Drought Stress. J. Plant Nutr. 2017, 40, 1453–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, A.E.; Andualem, A.M.; Ayana, M.T.; Zeru, M.A. Effects of Drought Stress on Growth, Physiological and Biochemical Parameters of Two Ethiopian Red Pepper (Capsicum Annum L.) Cultivars. J. Appl. Hortic. 2023, 25, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangotri, S.; Peerjade, D.A.; Awati, M.; Satish, D. Evaluation of Chilli (Capsicum Annuum L.) Genotypes for Drought Tolerance Using Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) 6000. J Exp Agric Int 2022, 44, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernau, V.M.; Barbolla, L.J.; McHale, L.K.; Mercer, K.L. Germination response of diverse wild and landrace chile peppers (Capsicum spp.) under drought stress simulated with polyethylene glycol. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0236001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ema, R.M.; Samad, R.; Mohtasim, M.; Islam, T. Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Analysis of PEG-Induced Water Stress Responses in Lentil (Lens Culinaris Medik.). J. Plant Nutr. 2025, 48, 2019–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud Sir, L.A.; Agustina P, L.; Winarseh, Y. In Vitro Selection of Cayenne Pepper (Capsicum Frutescens L.) Varieties Against Drought Stress Mediated Through Polyethylene Glycol. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2021, 20, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syafriani, E.; Sawitri, W.D.; Nur Syafia, E. Growth Response and Gene Expression Analysis of Chili Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.) Plant Dehydrin Against Salt Stress and Drought In Vitro. Pertanika J. Trop. Agric. Sci. 2024, 47, 1429–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oraee, T.; Shoor, M.; Tehranifar, A.; Nemati, S.H.; Oraee, A. Effect of Different Growth Medium on Soil Properties and Physiological Traits of Hollyhocks (Alcea Rosea L.) under Drought Stress. J. Hortic. Sci. 2021, 38, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A Revised Medium for Rapid Growth and Bio Assays with Tobacco Tissue Cultures. Physiol. Plant. 2006, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, J.D. Speed of Germination—Aid In Selection And Evaluation for Seedling Emergence And Vigor cropsci1962.0011183X000200020033x. Crop Sci. 1962, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnhold, E. Pacote Em Ambiente R Para Análise de Variância e Análises Complementares. Braz. J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci. 2013, 50, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. A New Look at the Statistical Model Identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Regras Para Análise De Sementes; Mapa, 2009; ISBN 978-85-99851-70-8.

- Demir, I.; Mavi, K. Effect of Salt and Osmotic Stresses on the Germination of Pepper Seeds of Different Maturation Stages. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2008, 51, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammoudi, N.; Nagaz, K.; Ferchichi, A. Hydrotime Analysis to Explore the Effect of H2O2− Priming in the Relationship between Water Potential (Ψ) and Germination Rate of Capsicum Annuum L. Seed under NaCl− and PEG− Induced Stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 167, 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finch-Savage, W.E.; Leubner-Metzger, G. Seed Dormancy and the Control of Germination. New Phytol. 2006, 171, 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A. Drought Resistance–Is It Really a Complex Trait? Funct. Plant Biol. 2011, 38, 753–757. [Google Scholar]

- Wickramasinghe, I.M.; Seran, T.H. Assessing in Vitro Germination and Seedling Growth of Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) Cv KC-1 in Response to Polyethylene Glycol-Induced Water Stress. Sri Lanka J. Food Agric. 2019, 5, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbay, N. Studies on Seed Priming in Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.). In Advances in seed priming; Springer, 2018; pp. 209–239. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, H.; Song, C.; Zhu, J.-K.; Shabala, S. Mechanisms of Plant Responses and Adaptation to Soil Salinity. The innovation 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dias, M.C.; Freitas, H. Drought and Salinity Stress Responses and Microbe-Induced Tolerance in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 591911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Peng, Y.; Xu, W. Crop Root Responses to Drought Stress: Molecular Mechanisms, Nutrient Regulations, and Interactions with Microorganisms in the Rhizosphere. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sané, A.K.; Diallo, B.; Kane, A.; Sagna, M.; Sané, D.; Sy, M.O. In Vitro Germination and Early Vegetative Growth of Five Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) Varieties under Water Stress Conditions. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 1478–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monneveux, P.; Nemmar, M. Contribution à l’étude de la résistance à la sécheresse chez le blé tendre (Triticum aestivum L.) et chez le blé dur (Triticum durum Desf.) : étude de l’accumulation de la proline au cours du cycle de développement. Agronomie 1986, 6, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiz, L.; Zeiger, E.; Møller, I.M.; Murphy, A. Fisiologia e Desenvolvimento Vegetal - 6ed; Artmed Editora, 2017; ISBN 978-85-8271-367-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandra, A.; Vijayaraghavareddy, P.; Purushothama, C.; Nagaraju, S.; Sreeman, S. Decoding Stomatal Characteristics Regulating Water Use Efficiency at Leaf and Plant Scales in Rice Genotypes. Planta 2024, 260, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Castro, E.; Pereira, F.J.; Paiva, R. Histologia Vegetal: Estrutura e Função de Órgãos Vegetativos. Lavras UFLA 2009, 9. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).