1. Introduction

In the heavy-duty vehicle industry, such as trucks, trains, and even airplanes, preventive maintenance includes essential tasks such as visual inspection. One of the critical aspects of these inspections is the detection of cracks in the brake discs. Traditional visual inspection methods have significant limitations, such as susceptibility to human error, lack of consistency, and the repetitive and tedious nature of work [

1,

2]. In response to these limitations, automating the inspection process emerges as an effective solution to optimize evaluation time and allow technical staff to focus on other maintenance tasks. However, to ensure accurate detection and determine which cracks are classified as acceptable or unacceptable, the first major challenge arises: the limited documentation and research regarding what qualifies as an unacceptable crack in brake discs. The only sources that provide a detailed classification of cracks by size and type are maintenance manuals from railway brake disc manufacturers. Currently, we rely on the Faiveley Transport manual “Axle-mounted brake disc WKS 640G-NB” [

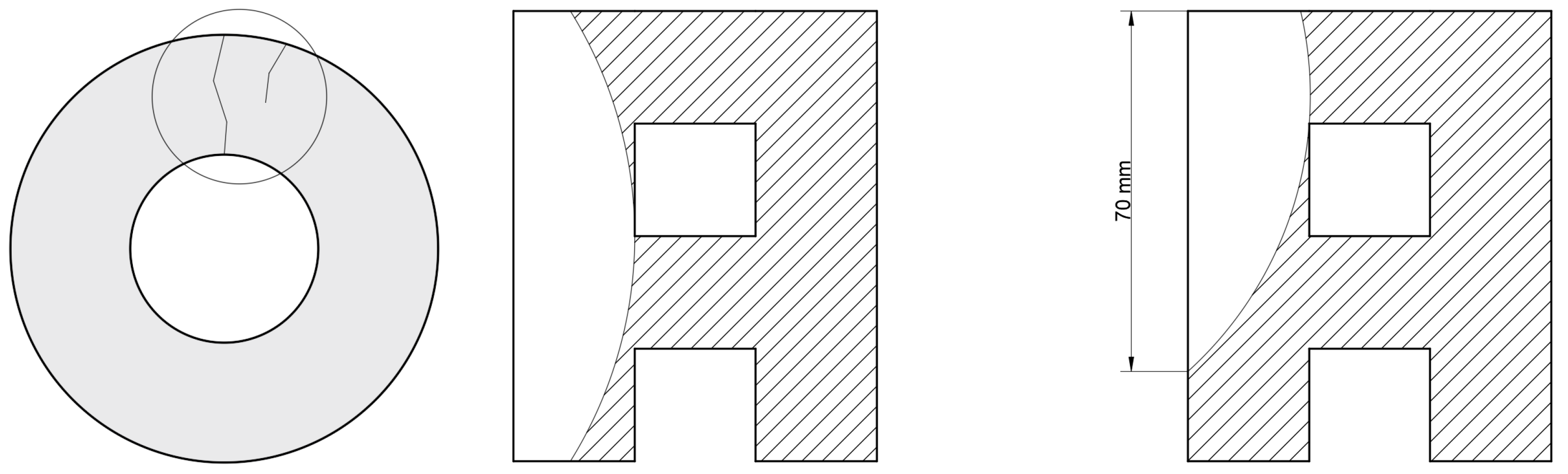

3] that defines penetrating cracks as unacceptable and, under certain conditions, also classifies incipient cracks as such (

Figure 1). The penetrating cracks run across the entire inner and outer diameter of the brake disc, fully penetrating the cross section. Incipient cracks originate on the friction surface, either at the inner or outer edge of the friction ring, and locally penetrate that area. These are considered acceptable up to 70mm in length, although this limit may vary depending on the manufacturer or maintenance company. This regulatory gap poses a challenge to automating railway maintenance, as it prevents the establishment of objective intervention criteria. Therefore, this study adopts Faiveley Transport’s parameters, considering cracks longer than 80 mm as unacceptable. This criterion was directly implemented into the automatic classification system, enabling the model to distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable cracks based on thermal analysis. This integration helps overcome the lack of unified standards and allows maintenance decisions to be standardized through artificial intelligence.

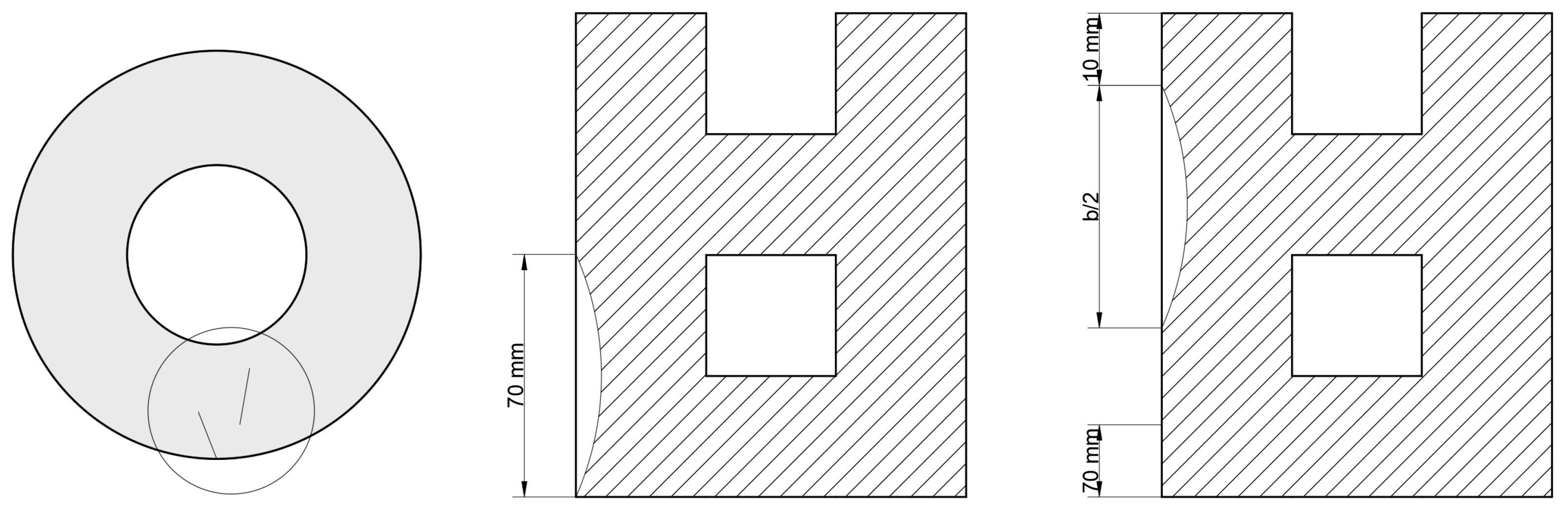

Superficial cracks are also detailed, such as cracks in the friction surface that do not penetrate the side of the friction ring in the axial direction. In addition, they are allowed up to 70 mm and touch the outer edge, and if they are more than 10 mm from the edge (inner or outer) and measure less than half of the diameter b (

Figure 2). As with incipient cracks, the value of 70 mm can vary, and this study will also work with permissible cracks of up to 80 mm.

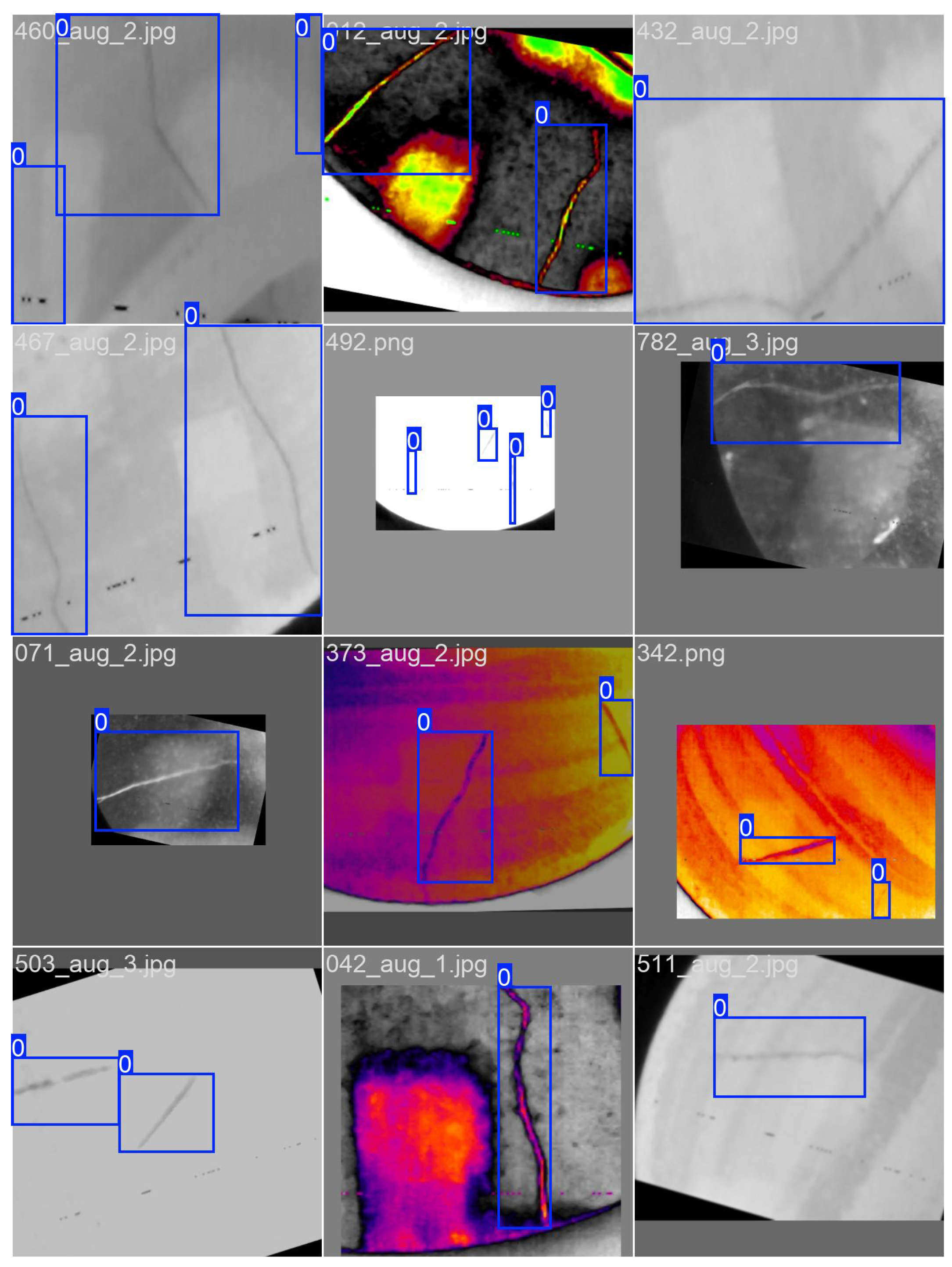

First, the Yolov8 training model was selected, chosen after evaluating different object detection models. Wang [

1] was able to detect areas affected by corrosion and cracks in the aerospace industry by combining computer vision and machine learning using the Mask R-CNN model. In their research, they managed to integrate visual inspection by technical personnel and augmented reality glasses when making the detection in real time. Similarly, for the metallurgical industry, Konovalenko [

4] performs the detection of abrasions and scratches on metal surfaces with a database of 9385 in grayscale, using the ResNet152 training model. Wang [

5], who used thermo graphic vision to detect five imperfections: upward deformation, black line, cracks, inclusion of gas bubbles and slag, and convolutional neural networks (CNN) were used to heat a sheet of metal with these deformations by passing it through hot rollers. Wang [

6] and Liu [

7] incorporate the use of the YoloV4 and SLF-Yolo models, respectively, both improved for the detection of defects, bumps, and cracks in metal surfaces. These investigations have evaluated previous Yolo models (You Only Look Once) that were discarded, since the proposed method exceeds the average average accuracy of previous models. Yu [

8] takes a different approach, since, instead of using existing methods, he proposes a deep learning precision metal corrosion detector based on Deep Learning reaching an average accuracy of 84.96%, surpassing its investigated counterpart, Yolov3-tiny. Aboulhson [

9] evaluates various detection models such as CNNs, FPN, and U-Net, incorporating "Explainable Artificial Intelligence" (XAI), which introduces a greater understanding of the decision-making processes of steel surface defect detection models. Zhang [

10] uses the Yolov8-CM model, achieving an overall detection of 90% and crack detection of 74%, exceeding its previous counterparts (v4, v5, v7). Chen [

11] performs the detection of defects in aluminum surfaces by proposing an improved algorithm based on the Yolov8n model, also comparing two databases: the "Tianchi aluminum profile surface defect dataset" (APDDD) and the GC10-DET and demonstrated that the proposed model improves the average accuracy by 6.6% and 7.7% respectively.

In this study, the FLIR Lepton 3.1R thermal camera was selected to acquire thermal images of brake discs with and without cracks, due to its low cost, 160 × 120 px resolution, and compatibility with the Raspberry Pi 5. This single-board computer was used as an embedded platform to load the trained neural network and run the classification system in the field. To validate the functionality of the model, a simulated railway environment was created using artificially heated car brake discs to replicate the heat generated by friction under real conditions. The thermal images obtained were used to train crack detection and segmentation models.

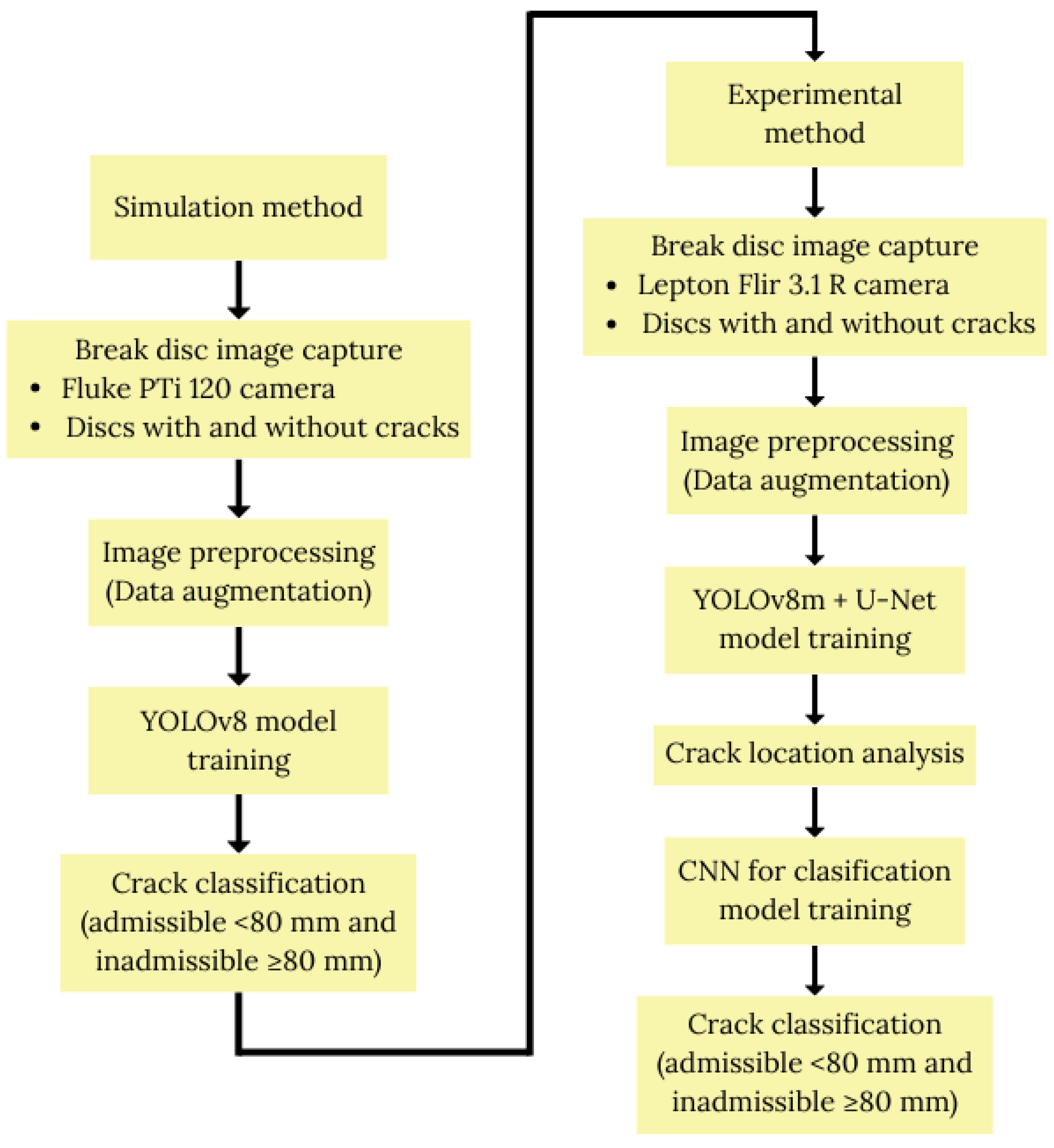

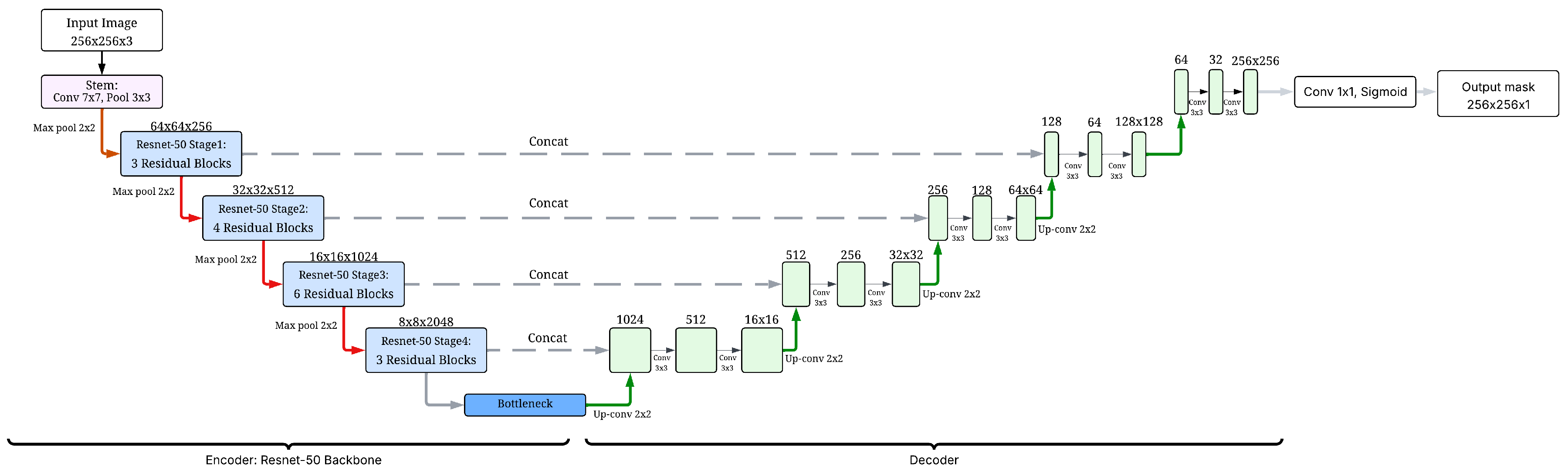

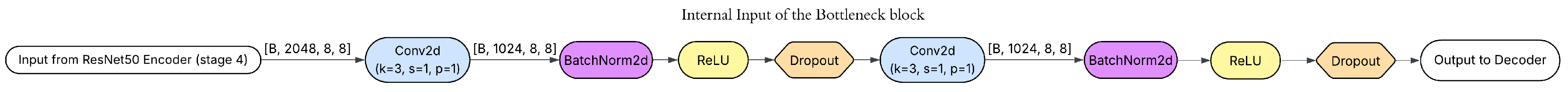

The methodology developed was divided into two main phases. In the first phase, a FLUKE PTi120 camera was used to acquire thermal images of a simulated brake disc. These images were processed, augmented, and used to train a base model with Yolov8, in order to preliminarily validate the feasibility of the thermal approach. In the second phase, new images were acquired using the FLIR Lepton 3.1R camera, allowing the creation of a larger and higher-quality dataset. These images were augmented and processed to train a Yolov8m model. Subsequently, the U-Net with ResNet50 architecture was trained on the same data set to perform semantic segmentation, and finally an additional CNN was integrated to classify the detected cracks by type. This hybrid architecture was evaluated using standard metrics and experimentally validated.

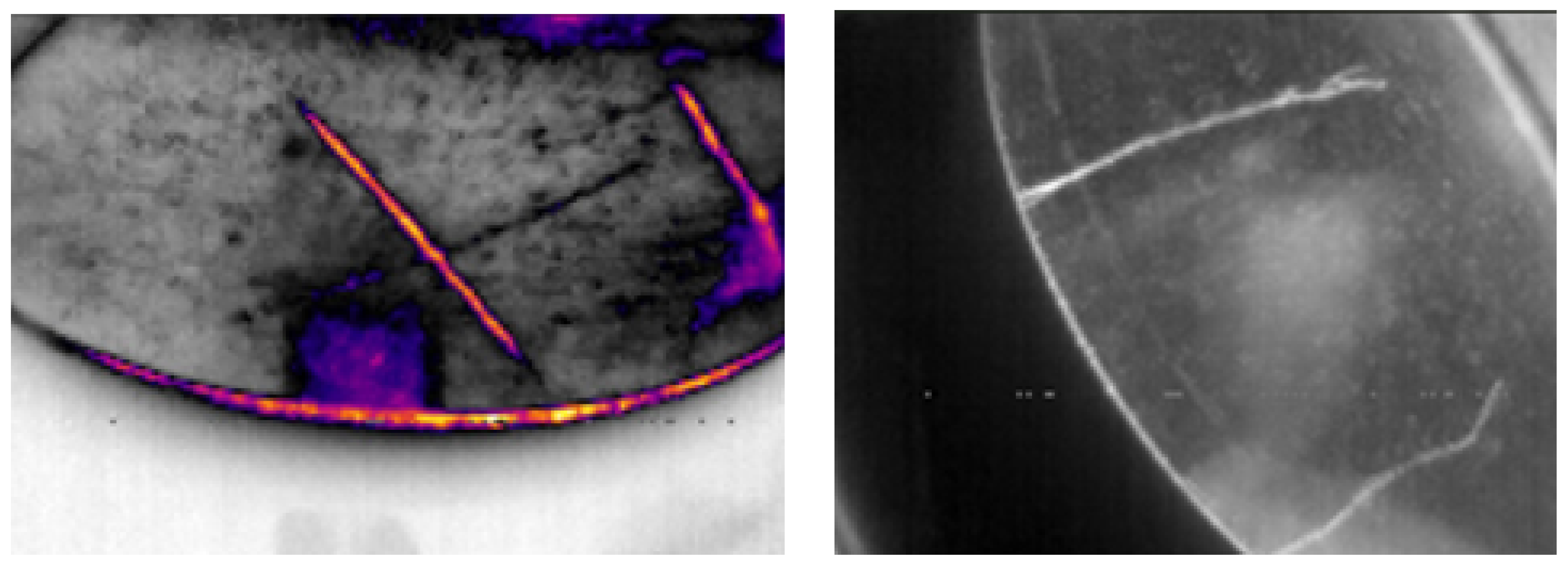

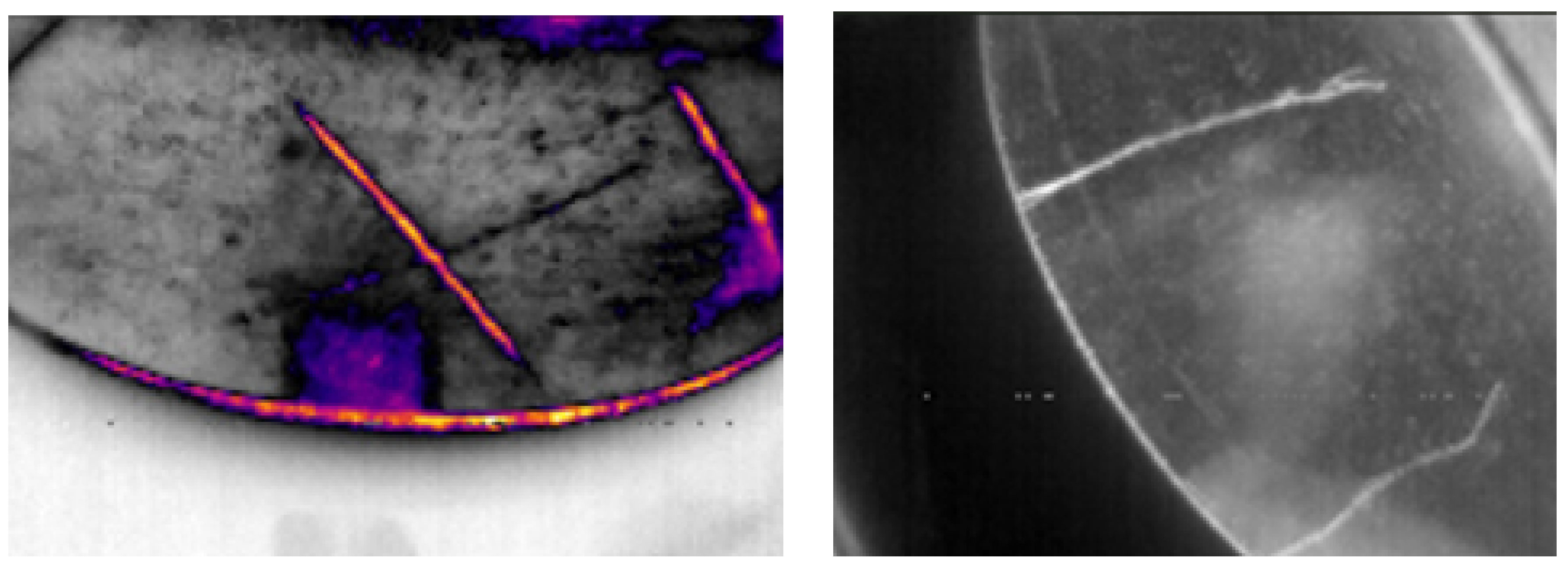

Figure 3.

Disc crack with combined vision (left) and grayscale (right). Own elaboration (2025)

Figure 3.

Disc crack with combined vision (left) and grayscale (right). Own elaboration (2025)

This complete methodological workflow is summarized in

Figure 4 and is further detailed in the following sections, including a comparative analysis between models and a discussion of the future applicability of the system in real railway environments.

3. Results

To validate our research, we used the precision metrics (P), recall (R), and mean average precision (mAP), following their corresponding equations (6), (7), (8) and (9). Precision represents the percentage of correctly detected cracks by dividing true positives (TP) by the sum of true positives and false positives (FP). Recall indicates the percentage of actual cracks that were detected, taking into account false negatives (FN). Finally, the mean average precision (mAP) summarizes the model performance based on the relationship between Precision and Recall. A high mAP value indicates that the model maintains high accuracy in object detection tasks [

2].

TP: True Positives – correctly detected cracks;

FP: False Positives – detections incorrectly classified as cracks;

FN: False negatives – actual cracks that were not detected.

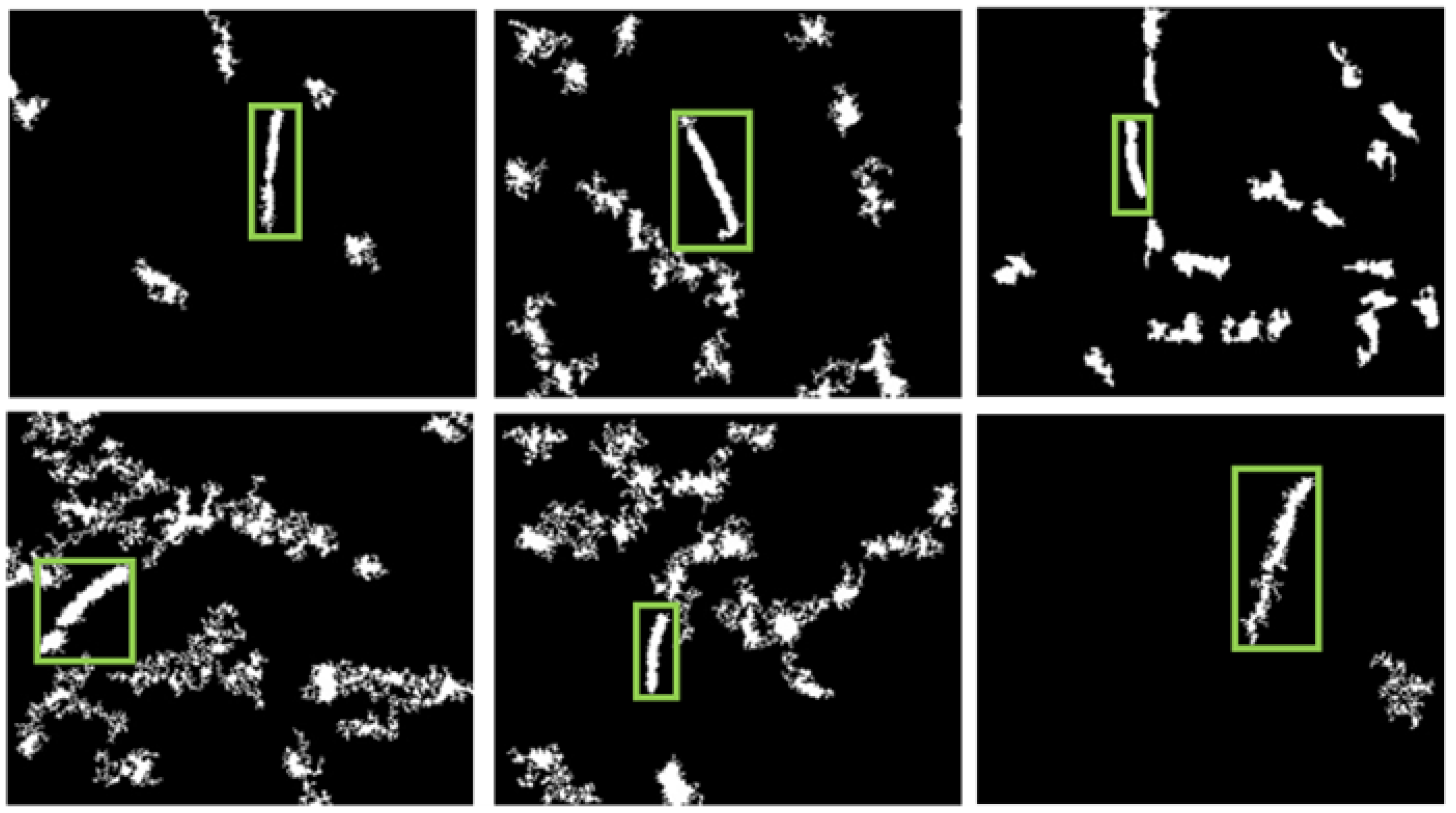

During the validation stage, consistent results were obtained in the detection of simulated cracks on car brake discs (simulation method). The tiny artificially generated cracks were correctly identified by the model even in cases with low thermal contrast, demonstrating the importance of the interpolation process and data augmentation techniques in enhancing the quality of the training set.

To quantitatively validate the system performance, a comparison was made between different approaches: the basic YOLOv8 model, the U-Net architecture used independently, and the proposed YOLOv8 medium model, which forms part of the final system. It should be noted that the developed Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) was not included in this comparison, as its role is focused solely on the post-detection classification of cracks, rather than on detection or segmentation.

These findings support the feasibility of implementing low-cost thermal cameras, such as the FLIR Lepton 3.1R, in combination with modern convolutional neural networks for predictive maintenance applications. Furthermore, the results confirm that a progressive training approach, starting with controlled simulations and later incorporating the full dataset, contributes significantly to the robustness and generalization of the model in real-world operating scenarios.

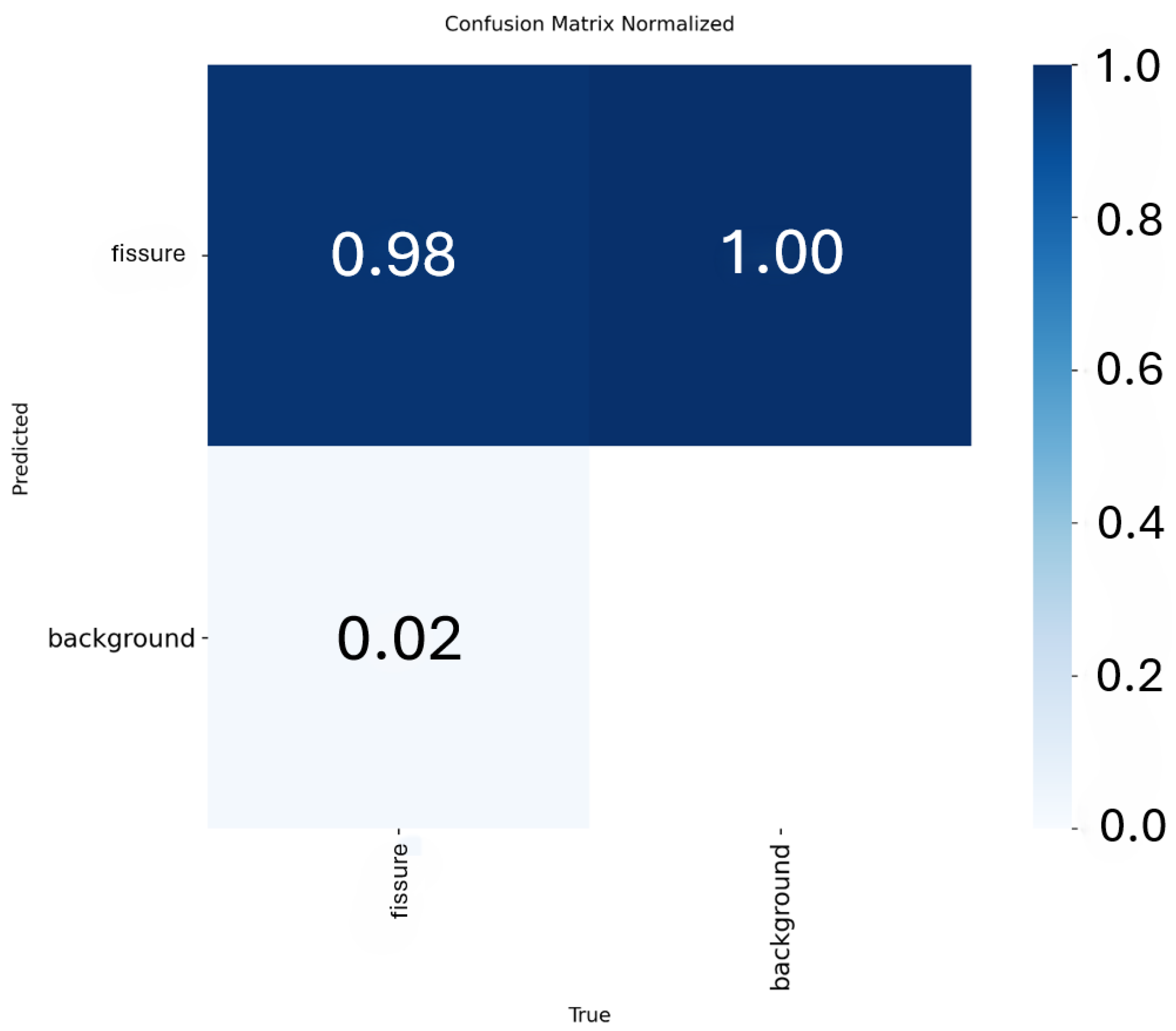

Figure 15 presents the normalized confusion matrix corresponding to the YOLOv8m model, which allows evaluating its performance by class. In this case, only two classes were considered: "crack" and "background." For the "crack" class, a recall of 0.98 was achieved, meaning the model correctly identified 98% of the actual cracks present in the images. Only 2% of the cracks were misclassified as background (false negatives), which is considered a low and desirable value for our detection model.

For the "background" class, perfect specificity was observed (TNR = 1.00), indicating that all regions without cracks were correctly classified as such. In other words, no false positives were detected for the "crack" class, which means that the model did not mistake background areas for defects, thereby minimizing false alarms. These results further demonstrate that the model is not only sensitive to real crack detection but also highly precise in background discrimination.

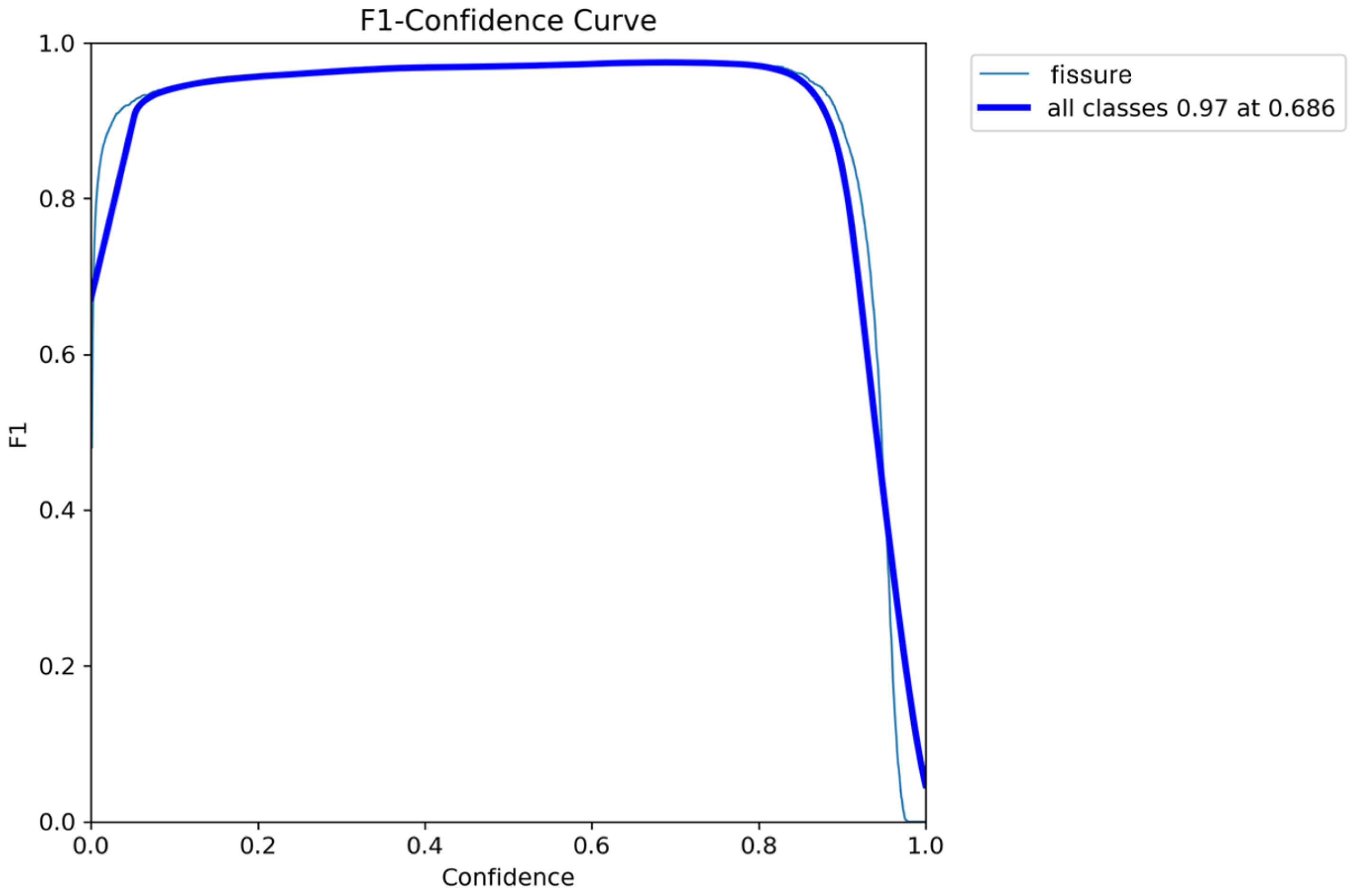

Figure 16 shows the F1 curve of the trained YOLOv8 medium model, which evaluates the balance between precision and recall as a function of the confidence threshold applied during detection. The blue line represents the overall behavior of the model, reaching a maximum F1-score of 0.97 at an optimal confidence threshold of 0.686. Moreover, the curve remains consistently high with an F1-score > 0.90 across a wide range of confidence values, from 0.2 to 0.9, demonstrating the model’s strong stability under varying levels of error tolerance. This suggests that the model maintains its performance without requiring critical adjustments to the decision thresholds.

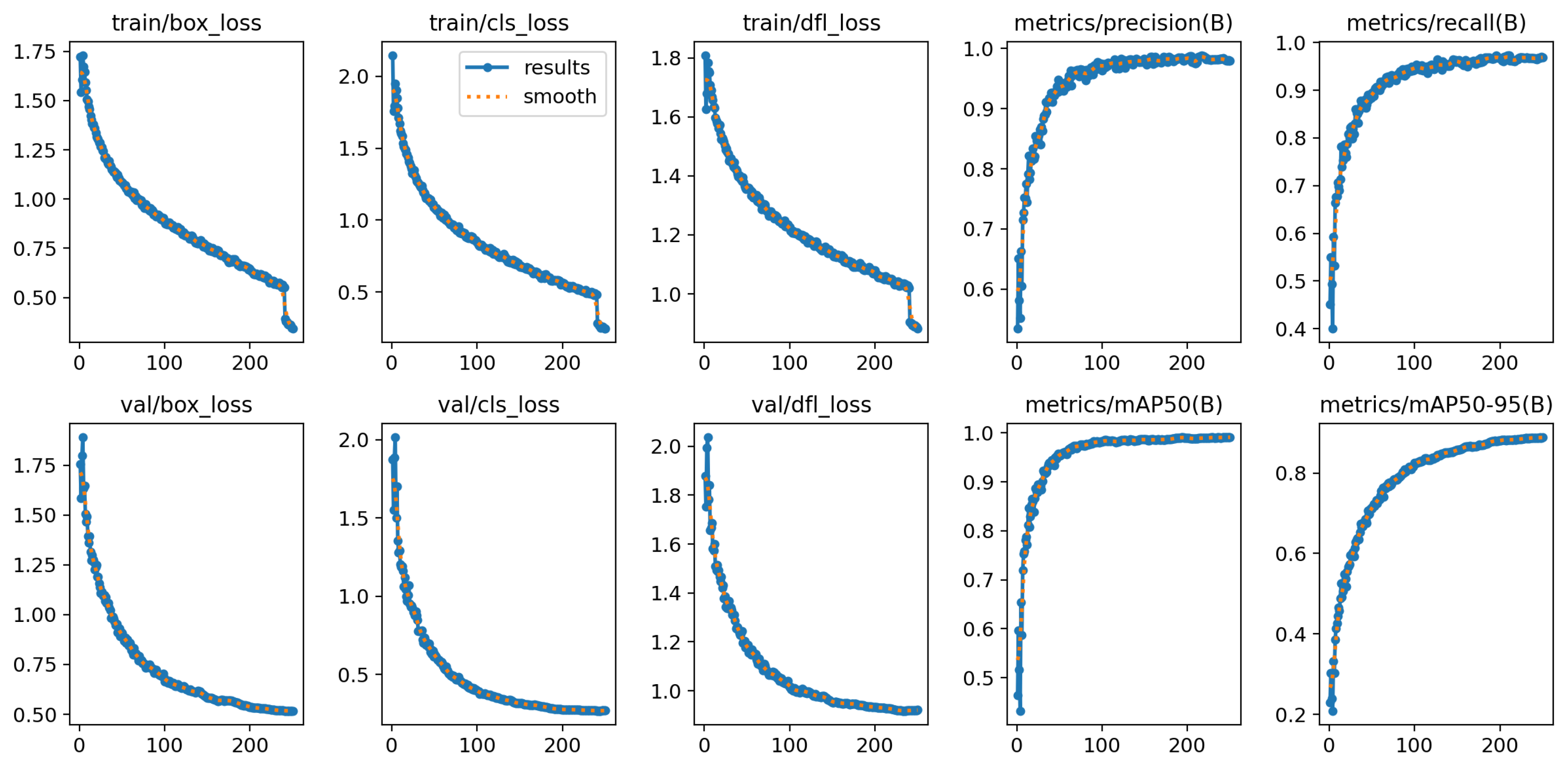

The model’s performance during the 250 training epochs (

Figure 17) shows both the evolution of the loss functions and the performance metrics. At the top, the training loss curves (train/box_loss, train/cls_loss, and train/dfl_loss) display a progressive and stable decrease, indicating that the model improves its ability to accurately locate cracks, classify their presence, and adjust the bounding box edges.

In parallel, the validation curves (val/box_loss, val/cls_loss, and val/dfl_loss) exhibit a similar downward trend, suggesting good generalization and the absence of significant overfitting. This convergence between training and validation supports that the model maintains stable performance when exposed to unseen data.

On the right-hand side of the figure, performance metrics are shown: precision, recall, mAP50, and mAP50-95. All of them display rapid growth during the initial epochs, followed by stabilization at high values, close to 1.0. The mAP50, which measures average precision at 50% intersection over union (IoU), reaches values near 1.0, indicating highly effective and reliable detection. Similarly, mAP50-95, a stricter metric than mAP50, also shows a sustained upward trend.

These results reinforce the evidence that the model not only correctly detects the presence of cracks but also delineates their contours with high precision, meeting the expected standards for automated railway inspection applications.

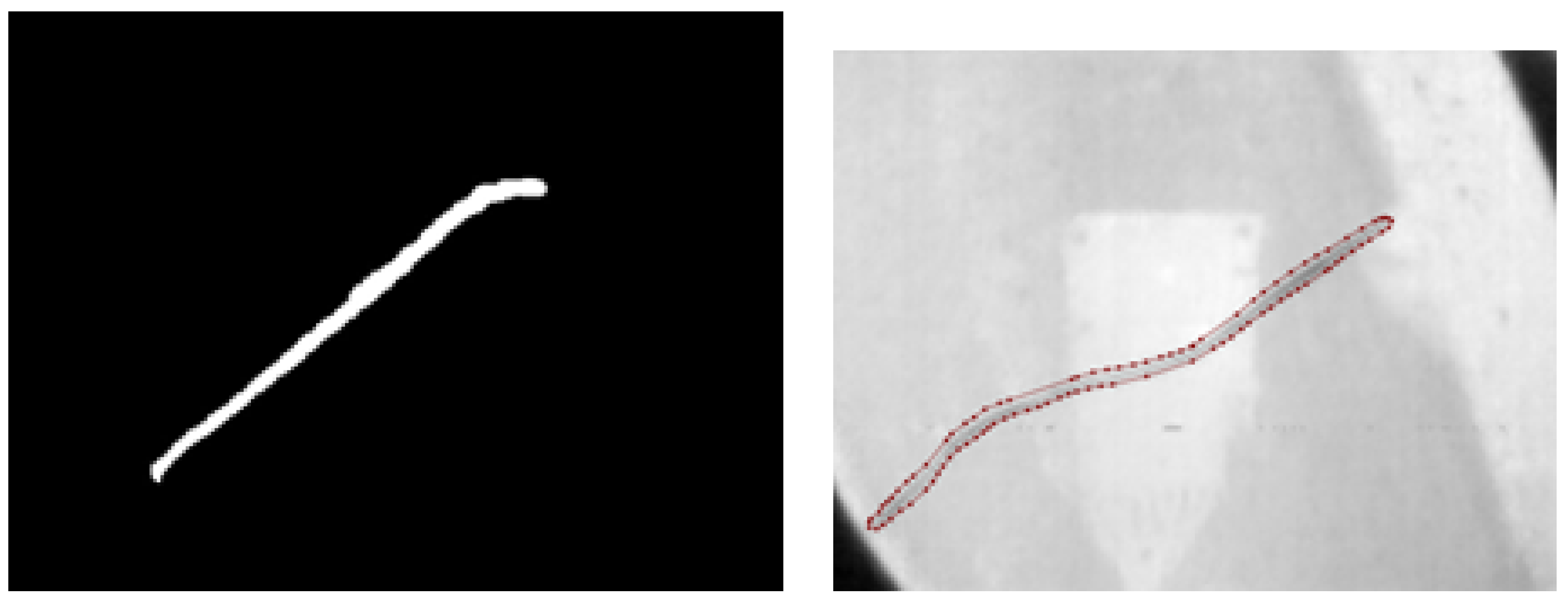

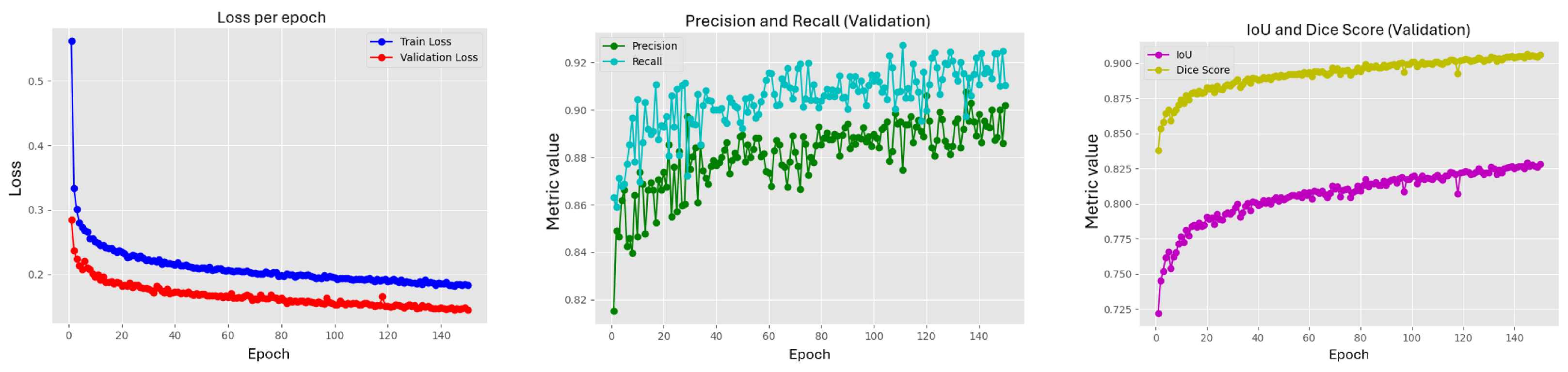

Regarding the performance of the U-Net (ResNet50) model during 150 training epochs (

Figure 18). The training loss shows a steady decline, while the validation loss stabilizes and exhibits a slight increase after epoch 30, suggesting potential overfitting. Despite this, the validation metrics remain high: precision ( 0.90) and recall ( 0.85), both indicating strong segmentation capability. Additionally, the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) ( 0.88) and Dice Score (>0.90) reflect a high degree of overlap between the predicted and ground truth masks of the cracks. The consistently high Dice Score demonstrates excellent spatial accuracy in segmentation, indicating that the model is able to accurately predict both the shape and location of the cracks.

As a basis for performance comparison, our proposed methodology was evaluated against several architectures: the basic YOLOv8 model, the medium variant YOLOv8m, a standard U-Net, a simplified U-Net with data augmentation and fine-tuning, and a U-Net with transfer learning using ResNet50 as backbone. The custom CNN model was excluded from this comparison, as it was designed exclusively for classification tasks and not for detection or segmentation. The results, summarized in

Table 2, reveal a clear performance improvement across the models as the training approach and architecture complexity increased, particularly when using enhanced datasets captured with the FLIR Lepton 3.1R thermal camera.

Among the detection-based models, the YOLOv8m model demonstrated the best overall performance, achieving a precision of 98%, mAP50 of 99%, mAP50-95 of 89%, and recall of 97%. These values represent a substantial improvement over the basic YOLOv8 model, highlighting the benefits of higher-resolution data, more robust augmentation strategies, and appropriate model selection.

In addition to evaluating detection-based models, a detailed comparison was also carried out among different configurations of the U-Net architecture to assess their segmentation capabilities. Initially, a simplified version of the U-Net model was implemented, using its most basic configuration without any pretrained weights. This version struggled significantly in accurately segmenting the cracks, particularly due to the low thermal contrast and fine morphology of the defects. As a result, its performance remained limited, with a precision of 71%, recall of 75%, and a mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) of 0.61.

To improve these outcomes, a second approach was attempted using the same simplified U-Net architecture, but now integrating data augmentation techniques and fine-tuning. Specifically, the model was initialized with the pretrained weights obtained from the previous training, with the goal of enhancing its learning capacity from the augmented dataset. Although this method led to a noticeable performance improvement—reaching a precision of 79%, recall of 88%, and mIoU of 0.71—the segmentation accuracy was still not optimal for field application.

Finally, to address these limitations, a more advanced version of U-Net was developed using a ResNet50 backbone. This model was trained from scratch with transfer learning, allowing ResNet50 to act as a feature extractor and automatically select the most relevant filters for segmentation. This architectural enhancement enabled the model to generalize more effectively and extract higher-level spatial features from the input images. As a result, this version achieved the best performance among all U-Net configurations: 90% precision, 92% recall, and an mIoU of 0.83—demonstrating a significantly improved ability to accurately delineate cracks, even under challenging thermal conditions.

These progressive results clearly show that the segmentation quality is highly dependent on both the model architecture and training strategy. While the basic U-Net provided a useful baseline, incorporating fine-tuning and ultimately using a deep backbone like ResNet50 yielded much more robust and reliable segmentation, particularly critical for evaluating the morphology and severity of cracks in predictive maintenance applications.

Table 3.

Comparison between the simulated and experimental method

Table 3.

Comparison between the simulated and experimental method

| Type |

Train Loss |

Val Loss |

Precision |

mAP50 |

mAP50-95 |

Recall |

mIoU |

| Yolov8 |

0.45 |

0.53 |

0.85 |

0.69 |

0.65 |

0.68 |

– |

| Yolov8m |

0.34 |

0.51 |

0.98 |

0.99 |

0.89 |

0.97 |

– |

| U-Net |

0.24 |

0.39 |

0.71 |

– |

– |

0.75 |

0.61 |

| Simplified U-Net with data augmentation and fine tunning |

0.24 |

0.28 |

0.79 |

– |

– |

0.88 |

0.71 |

| U-Net Transfer Learning (Backbone ResNet50) |

0.18 |

0.14 |

0.90 |

– |

– |

0.92 |

0.83 |

| Final model (YOLOv8m and U-Net Transfer Learning (Backbone ResNet50)) |

0.003 |

0.03 |

0.90 |

– |

– |

0.86 |

0.89 |

It is important to note that the significant improvement in precision, mAP, and recall values cannot be attributed solely to the change in model architecture. In this second phase, improvements were made not only to the model but also to the data set itself. The quality and thermal resolution of the images were improved, the amount of data was increased through augmentation techniques, and more representative images of simulated conditions were incorporated. Therefore, this comparison reflects the combined impact of both factors, model architecture and data set quality, on the final performance of the system, highlighting the importance of a comprehensive approach to crack detection and classification tasks.

To achieve a robust and deployable solution, a final model was constructed by combining the detection capabilities of YOLOv8m with the high precision segmentation provided by the U-Net architecture enhanced with a ResNet50 backbone. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both models: YOLOv8m contributes an outstanding detection performance, while U-Net with transfer learning provides detailed segmentation with 90% precision, 92% recall, and a mean intersection over Union (mIoU) of 0.83. The integrated system achieves balanced performance with strong generalization, as reflected in the final evaluation metrics: a training loss of 0.003, validation loss of 0.03, 90% precision, 86% recall, and a mIoU of 0.89. These results confirm that the proposed model is well suited for real-world crack detection and segmentation tasks, enabling reliable identification and accurate delineation of structural defects under challenging thermal imaging conditions.

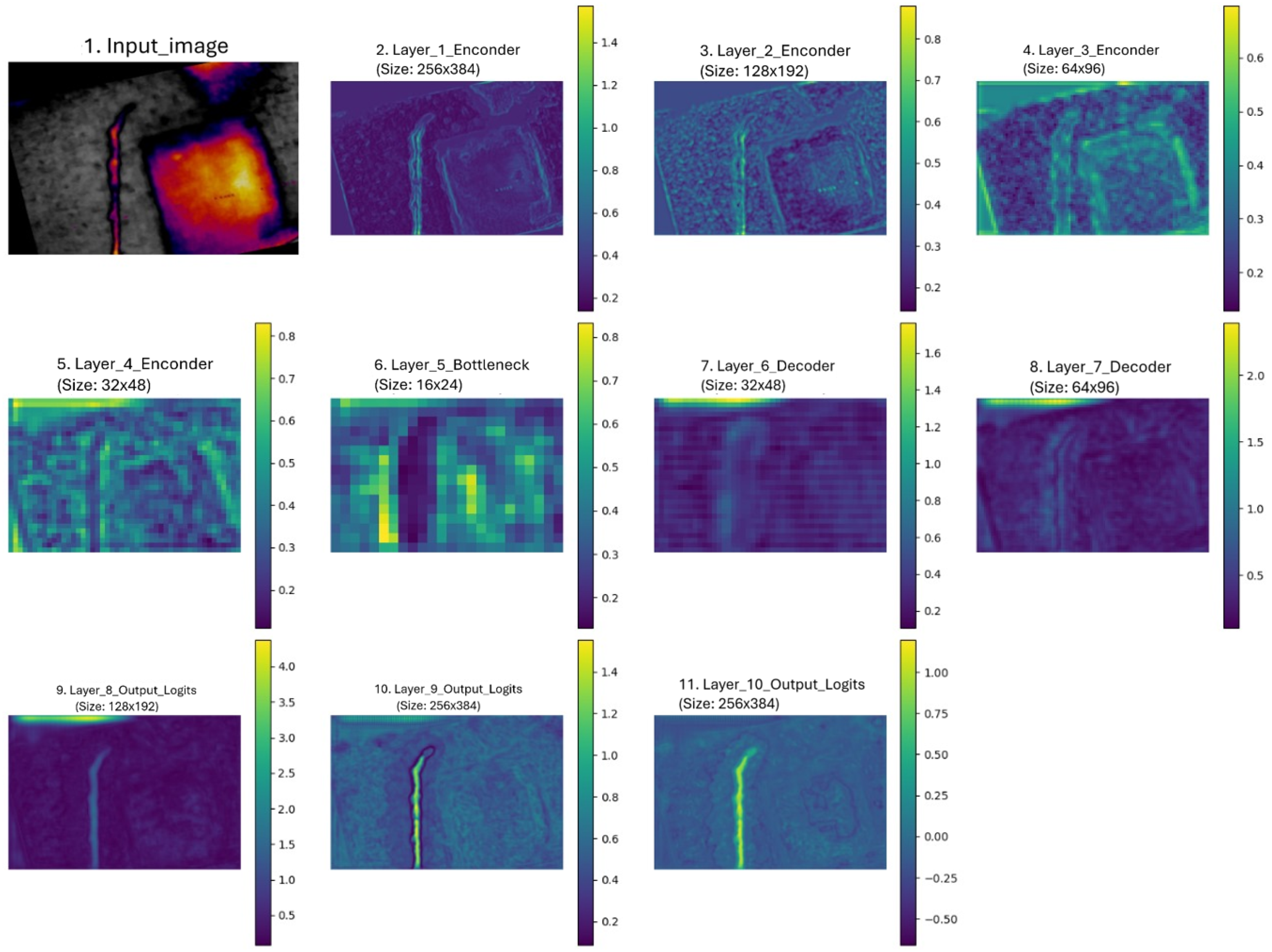

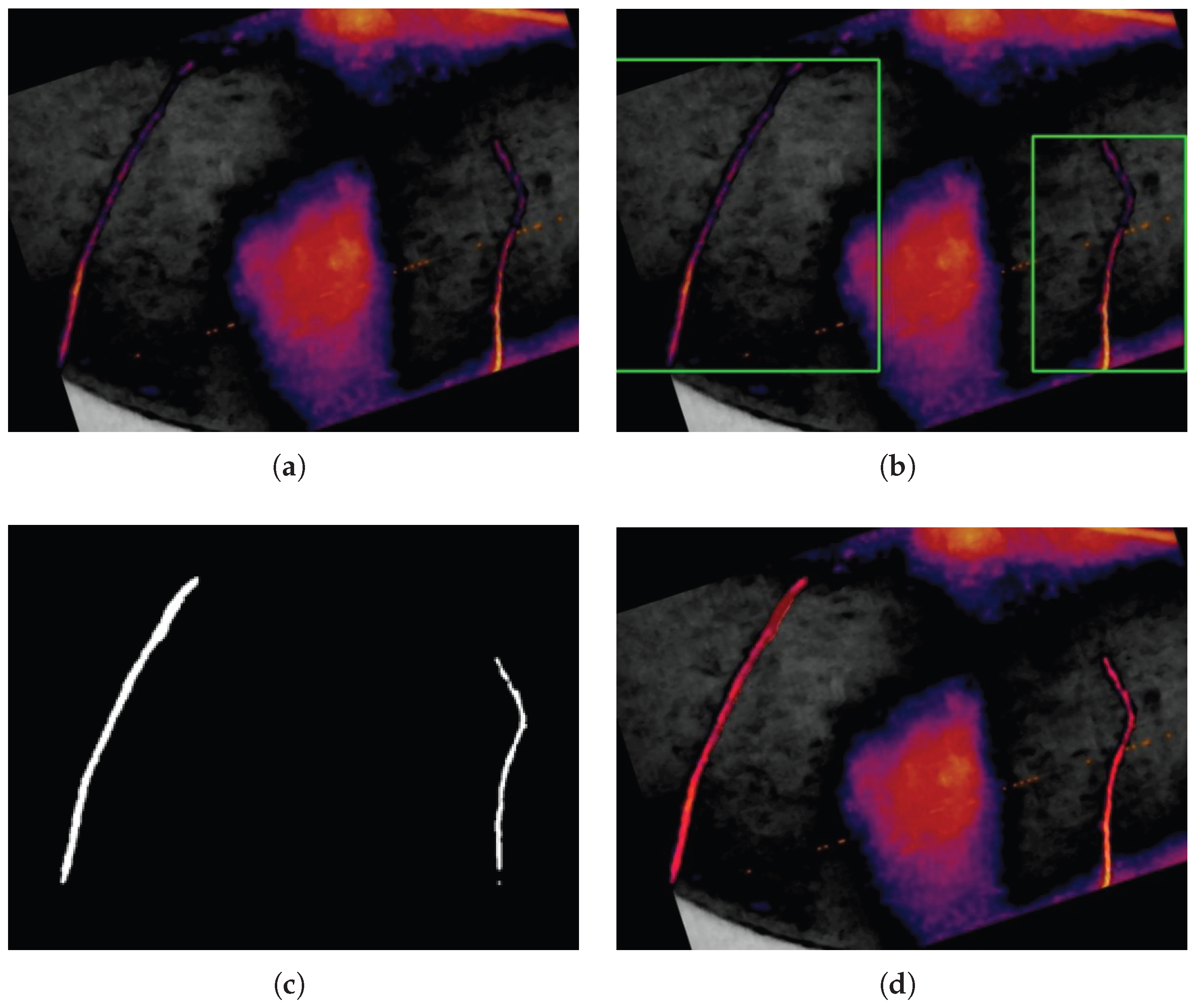

The combined operation of the YOLOv8 medium and U-Net (ResNet50) models can be observed in

Figure 19, illustrating the integration of both architectures in the crack detection and segmentation process. In Step A, the original image captured by the thermal camera is shown. Then, in Step B, the YOLOv8m model detects the cracks and outlines their approximate locations on the brake disc surface using bounding boxes. In Step C, each detected region is automatically cropped and individually processed by the U-Net model, which performs precise segmentation of the cracks through a mask. Lastly, in Step D, the combined result is presented: the accurate detection of the two cracks present, along with their segmented representation, allowing for detailed visualization of their shape, length, and path.

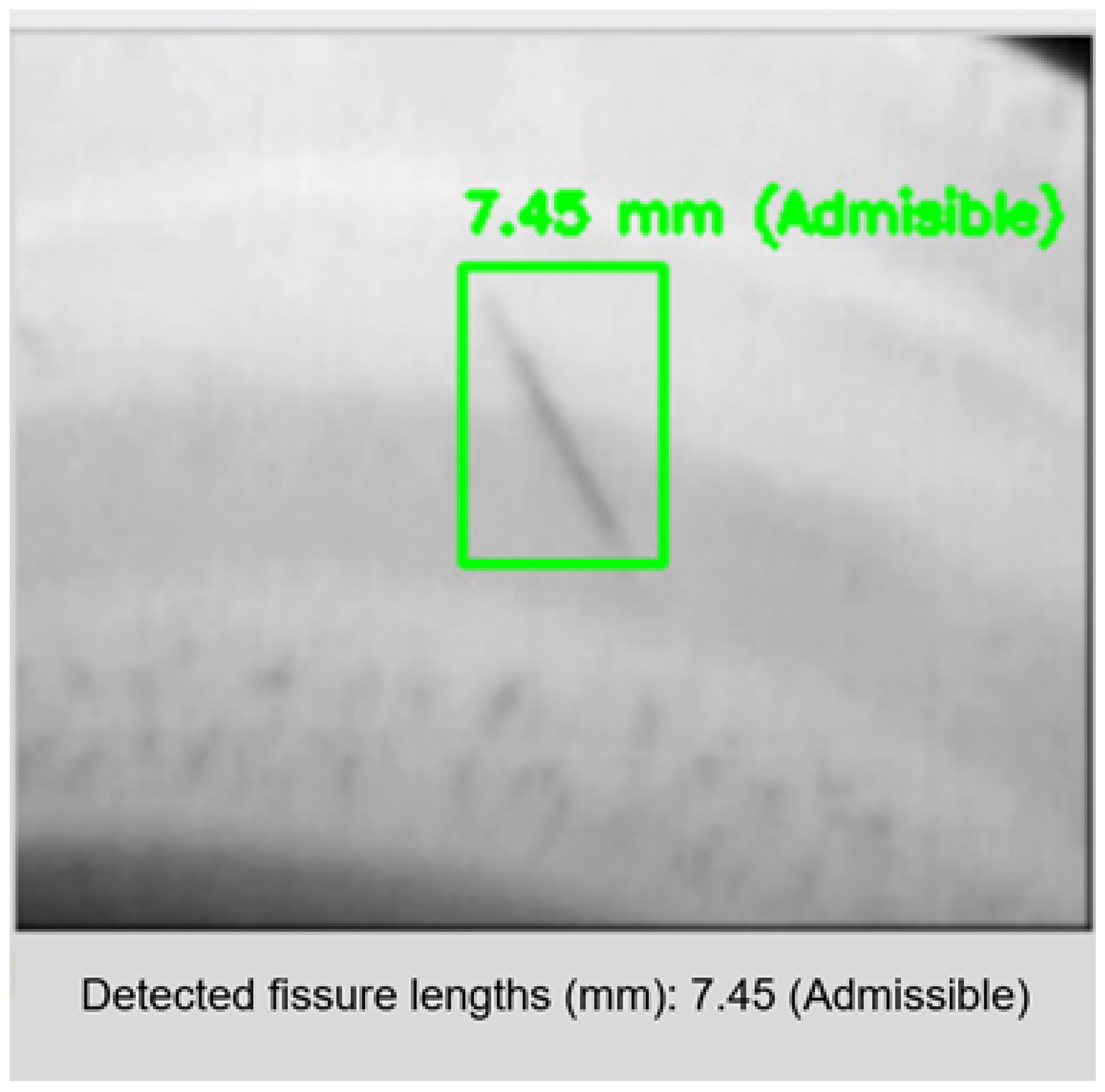

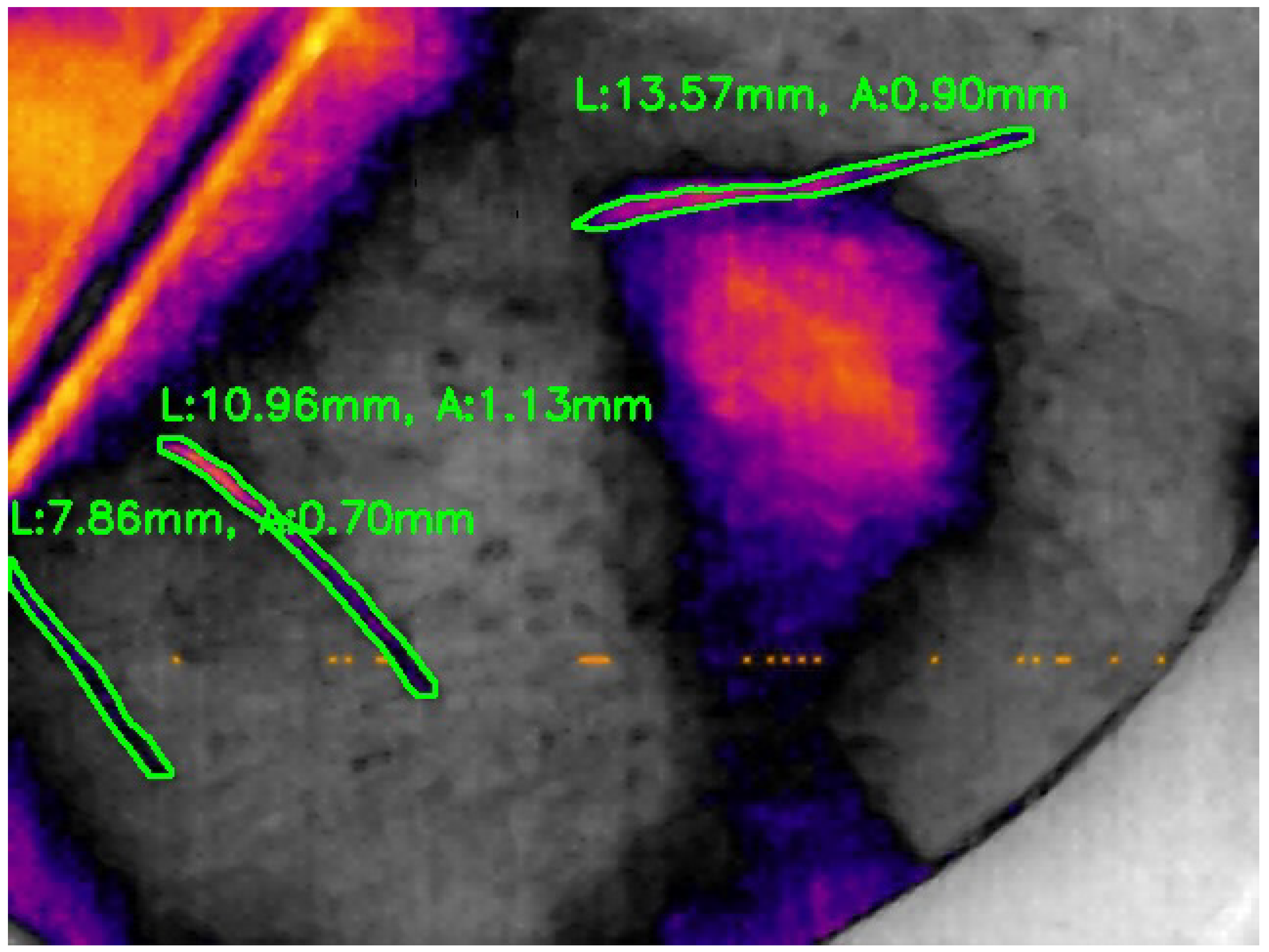

Finally,

Figure 20 illustrates the final implementation of the system, which includes the use of the infrared camera’s field of view (FOV) to estimate the real dimensions of the cracks. In this case, the FLIR Lepton 3.1R was placed at a distance of 3 cm from the brake disc, allowing accurate measurement of each crack’s length (L) and width (A) in millimeters. These values were extracted by converting pixel dimensions using the known FOV of the camera and the camera to object distance. The green outlines indicate the detected cracks that are classified as admissible, meaning their size is below the threshold established by Faiveley Transport (80 mm in length). This final step confirms the system’s capability not only to detect and segment cracks, but also to evaluate their dimensions with physical relevance for field applications.

4. Conclusions

The analysis of these results leads to the conclusion that the combined model—integrating both bounding box-based detection (YOLOv8m) and precise segmentation (U-Net (ResNet50)) offers a robust and adaptable solution. Furthermore, the system has proven capable of generalizing effectively without relying exclusively on environmental thermal conditions, which is crucial for its application in predictive railway maintenance under various operational scenarios.

One of the main limitations in applications of this nature is the scarcity of specific datasets for thermal cracks. Previous studies [

30,

31], have highlighted this gap, which hinders the performance of advanced models like YOLOv8 that require large volumes of data for effective generalization. In this study, a dataset of over 27000 images was generated, combining both synthetic and real data. This was a key factor in achieving high levels of precision and robustness in the model.

However, it is important to emphasize that the results cannot be attributed solely to dataset enhancement. Model architecture selection and the integration of different deep learning approaches also played a critical role. In particular, the combination of YOLOv8m and U-Net (ResNet50) takes advantage of the strengths of both models: YOLOv8m provides fast detection with high accuracy, while U-Net (ResNet50) delivers detailed segmentation of crack contours. This dual architecture outperforms individual approaches by offering both speed and morphological precision, improving the evaluation of the defect in terms of presence, shape, and severity. Therefore, the final system performance reflects the combined result of an optimized model and an improved dataset, demonstrating that a comprehensive approach is key to thermal crack detection and classification tasks.

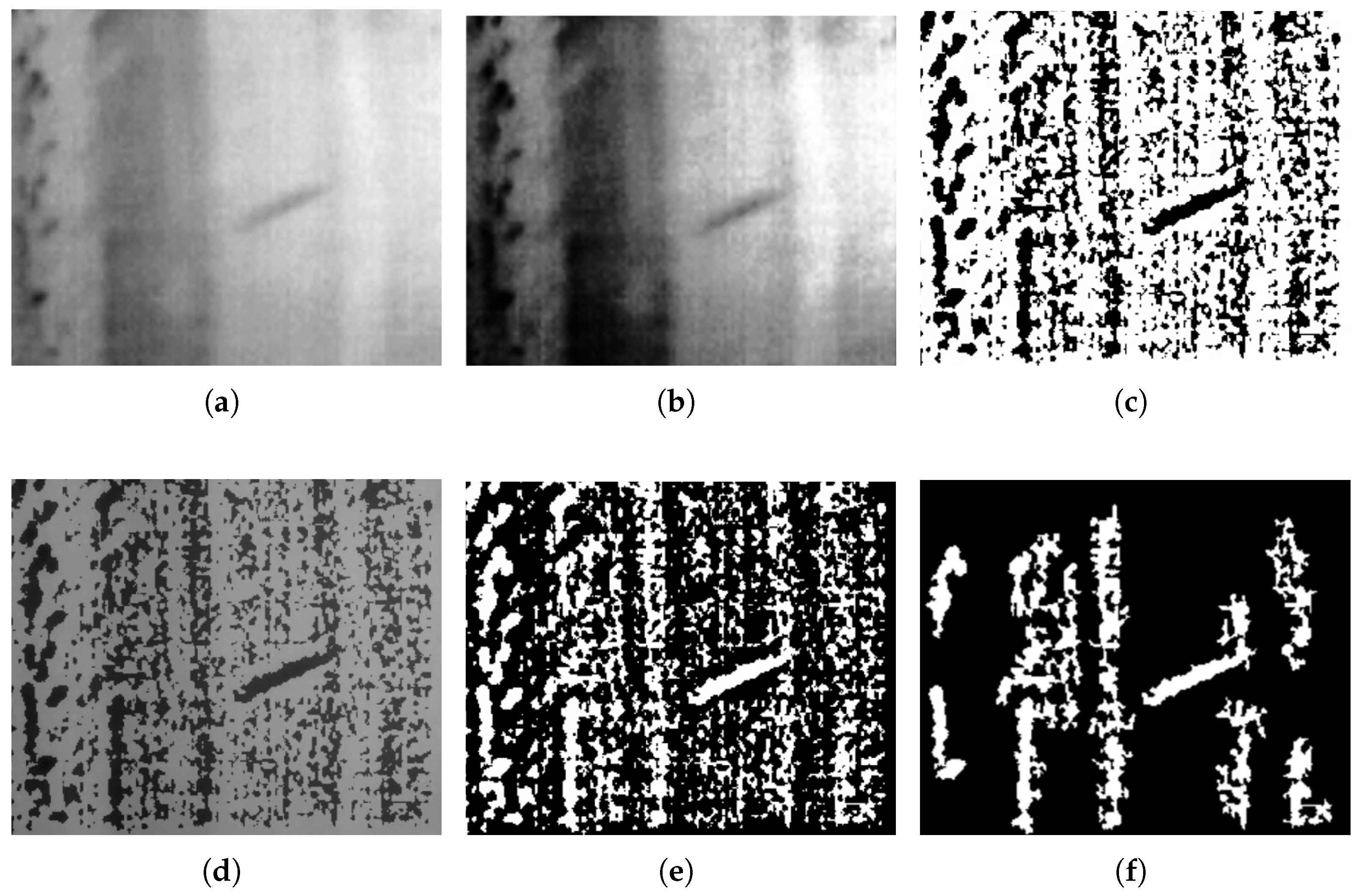

Additionally, it was shown that image pre-processing plays a fundamental role in enhancing model performance. Binarization and noise reduction helped facilitate crack detection, as the preprocessed images were interpreted more effectively by the model during training. This improvement was clearly reflected in the comparative tables between results obtained in simulations and experimental tests.

The results also revealed that YOLOv8m consistently outperformed U-Net (ResNet50) in overall accuracy and detection stability, while U-Net (ResNet50) contributed value through its morphological segmentation precision. This synergy validates the hybrid approach used and suggests that combining architectures can be an effective strategy in critical applications where both speed and detail are required.

Moreover, the proposed methodology is not limited to railway brake disc analysis. By integrating a fast detection model like YOLOv8m with a segmentation model like U-Net (ResNet50), a versatile solution is proposed that could also be applied to other domains where crack detection is essential—such as structural components in aircraft, industrial pipelines, heavy machinery, or even weld inspection. Its adaptability demonstrates that the system is not only effective in the railway context but also has potential for implementation across various areas requiring reliable, automated surface defect inspection.

Finally, the model has shown its ability not only to detect cracks but also to classify them by size and estimate their severity based on the wear level of the disc. This classification capability represents a significant step toward the development of intelligent structural monitoring systems that, beyond fault identification, provide objective prioritization criteria for field intervention. As a next step, the system will be validated in a real railway environment by acquiring thermal images directly from operational train brake discs and evaluating its performance in the context of preventive maintenance. The complete system is expected to be integrated into a Raspberry Pi for real-time execution, allowing technicians to visualize detections on-site and generate automatic reports. This implementation will verify the model’s performance under real operational conditions and assess its impact on railway maintenance efficiency.