1. Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare autoimmune disease characterized by widespread vasculopathy and progressive fibrosis of the skin and internal organs [

1]. SSc-associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) is among the most severe complications, further impairing functional capacity and survival [

2]. Assessing quality of life (QoL) in SSc-ILD is challenging, as SSc is a multisystem, inflammatory, and vasculopathic condition in which multiple organ domains contribute to overall disease burden [

3,

4]. This multifaceted involvement alters physical, emotional, and social well-being, yet the point at which patients begin to experience meaningful declines in daily functioning remains poorly defined [

5].

Accurate evaluation of disease burden requires integrating both clinical assessments and the patient’s perspective. Traditional physician-derived indices—such as the European Scleroderma Study Group Activity Index (EScSG-AI), the Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium Activity Index (SCTC-AI), and the Medsger Severity Scale (MSS)—capture clinician-observed parameters but may not fully reflect the functional limitations and QoL impact experienced by patients [

6,

7,

8].

In clinical studies of SSc-ILD, a variety of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have been used to capture the impact of the disease and its treatments on QoL. Organ-specific instruments, such as the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), King’s Brief Interstitial Lung Disease Questionnaire (K-BILD), and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Dyspnea Scale (FACIT-D), primarily assess respiratory symptoms and their functional impact [

9,

10,

11]. Generic PROMs, including the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36), Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index (HAQ-DI), and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-29 (PROMIS-29), evaluate overall health status and disability [

12,

13,

14]. In the SENSCIS trial [

15], PROMs included the SGRQ, FACIT-D, and HAQ-DI, incorporating the Scleroderma HAQ Visual Analogue Scale (SHAQ VAS) assessed at baseline and week 52 for associations with SSc-ILD severity [

16]. Other commonly applied tools include the Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ), Mahler’s Dyspnea Index (MDI), and Baseline and Transition Dyspnea Indices (BDI/TDI) [

17,

18,

19]. Recent studies, such as a prospective investigation correlating QoL with disease parameters and the Phase 2 ATHENA-SSc-ILD trial evaluating PRA023, have also integrated PROMs to assess patient-centered outcomes and the impact of therapeutic interventions on QoL [

20,

21].

Building on previous work, a novel PROM, the EULAR Systemic Sclerosis Impact of Disease (ScleroID), was recently introduced [

22]. The ScleroID is a brief, patient-derived questionnaire designed to capture self-assessed disease severity in SSc. It comprises 10 items across multiple domains, including physical function and organ involvement, with two items on fatigue and respiratory difficulty, which may be particularly relevant in patients with pulmonary involvement. ScleroID has been validated across multiple European centers, including Romania, showing strong internal consistency, high reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.839), and sensitivity to change over time. Its role capturing the impact of SSc-ILD on patients’ daily functioning and QoL remains unclear, prompting the present investigation into its relationship with lung function. This reinforces the importance of integrating objective measures of organ involvement with patient-reported outcomes. , as recommended in recent EULAR and SCTC guidelines for comprehensive SSc assessment [

23,

24]..

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This prospective observational study was conducted from 15 October 2023 to 30 August 2025. Patients with SSc-ILD confirmed by high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the thorax were recruited from the rheumatology clinic. All participants met the 2013 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (ACR/EULAR) classification criteria for SSc [

25]. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. SSc patients without evidence of ILD were excluded. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of „Sfanta Maria” Clinical Hospital (IRB Number:41520).

We retrieved pulmonary function tests (PFTs) and electronic lung HRCT image files from both baseline and the last available follow-up visit. The extent of lung fibrosis on HRCT, characterized by the presence of reticular changes and/or honeycombing, was classified as either <20% or ≥ 20% relative to the total lung volume [

26]. PFTs including diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), forced vital capacity (FVC), and forced expiratory volume during the first second (FEV1) were conducted following the guidelines of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ERS) [

27]. We also recorded the 6-minute walk test (6-MWT) and assessed dyspnea symptoms using functional classes [

28]. Documentation of right heart catheterization (RHC) was noted when performed, and pulmonary hypertension (PH) was diagnosed according to the 2015 European Society of Cardiology/ERS guidelines, defining PH as a mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) ≥25 mm Hg, measured with RHC [

29]. In the absence of RHC, PH was defined as a systolic arterial pressure (sPAP) >40mmHg on the echocardiography. Patients with available data over a 10-year follow-up period were evaluated for ILD progression, which was assessed by absolute changes in percentage predicted from baseline to follow-up, and defined as severe (total FVC decline >10%), moderate (FVC decline, 5-10%), or stable FVC (≤ 5% change) [

30,

31,

32].

The study aimed to evaluate the associations between the ScleroID, disease activity, and severity scores with baseline lung involvement in SSc-ILD patients. Disease activity was assessed using the European Scleroderma Study Group Activity Index (EScSG-AI) and the Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium Activity Index (SCTC-AI), both of which combine clinical and laboratory domains, with higher indicating greater disease activity. Disease severity was assessed using the Medsger Severity Scale (MSS), which rates major organ involvement on a 0–4 scale (0 = no involvement, 4 = severe involvement). QoL was measured using the self-administered validated Romanian version of the ScleroID questionnaire, in addition to the clinical indices above [

33].

Besides demographic data, collected information included SSc subtype (limited vs diffuse), disease duration calculated from the onset of non-Raynaud’s phenomenon, routine hematologic and immunologic tests, and nailfold capillaroscopy findings [

34,

35,

36]. Clinical features such as digital ulcers, telangiectasia, tendon friction rubs, PH, muscle weakness, and upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms, (if ever present) were recorded. Data on mortality related to ILD was also included.

2.2. Statistics

Baseline characteristics of the cohort were summarized using descriptive statistics, and the distribution of continuous variables was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Group comparisons were performed using two-sample t-tests, Chi-square tests, Kruskal-Wallis tests, or Mann-Whitney U tests, as appropriate. Relationships between patient-reported outcomes, disease activity and severity indices, and lung-specific measures were explored using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rho). Patients were stratified by HRCT-assessed lung fibrosis extent (10–20% vs. ≥20%) to determine whether associations differed by fibrosis severity. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 31.0.0.0, and graphical representations of correlations and group comparisons were generated to visualize trends in disease activity, severity, and patient-reported impact across fibrosis strata.

2.3. Results

2.3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Mean age was 56.0 (±10.8) years and median time since first non-Raynaud’s symptom was 4.2 (±4.7) years. Mean FVC% predicted was 76.8%, and mean DLCO% pre dicted was 54.3%. Mean baseline EscSG-AI total score was 6.1 (±1.7), baseline SCTC-AI was 34.5 (±14.8), Medsger severity score was 9.6 (±3.8), ScleroID total 4.1 (±2.4), and breathlesness item of ScleroID score was 3.8 (±2.9). No significant differences were observed by sex, age, or disease duration; however, patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc had higher SCTC-AI scores (p = 0.03), ATA positivity was associated with higher EscSG-AI scores (p = 0.04), while dyspnea of NYHA class > III and FVC < 80% predicted correlated with higher EscSG-AI scores (p = 0.05 and p = 0.04, respectively); notably, an HRCT fibrosis extent >20% and the presence of pulmonary hypertension were both linked to significantly higher scores across all instruments (p < 0.001) (

Table 1).

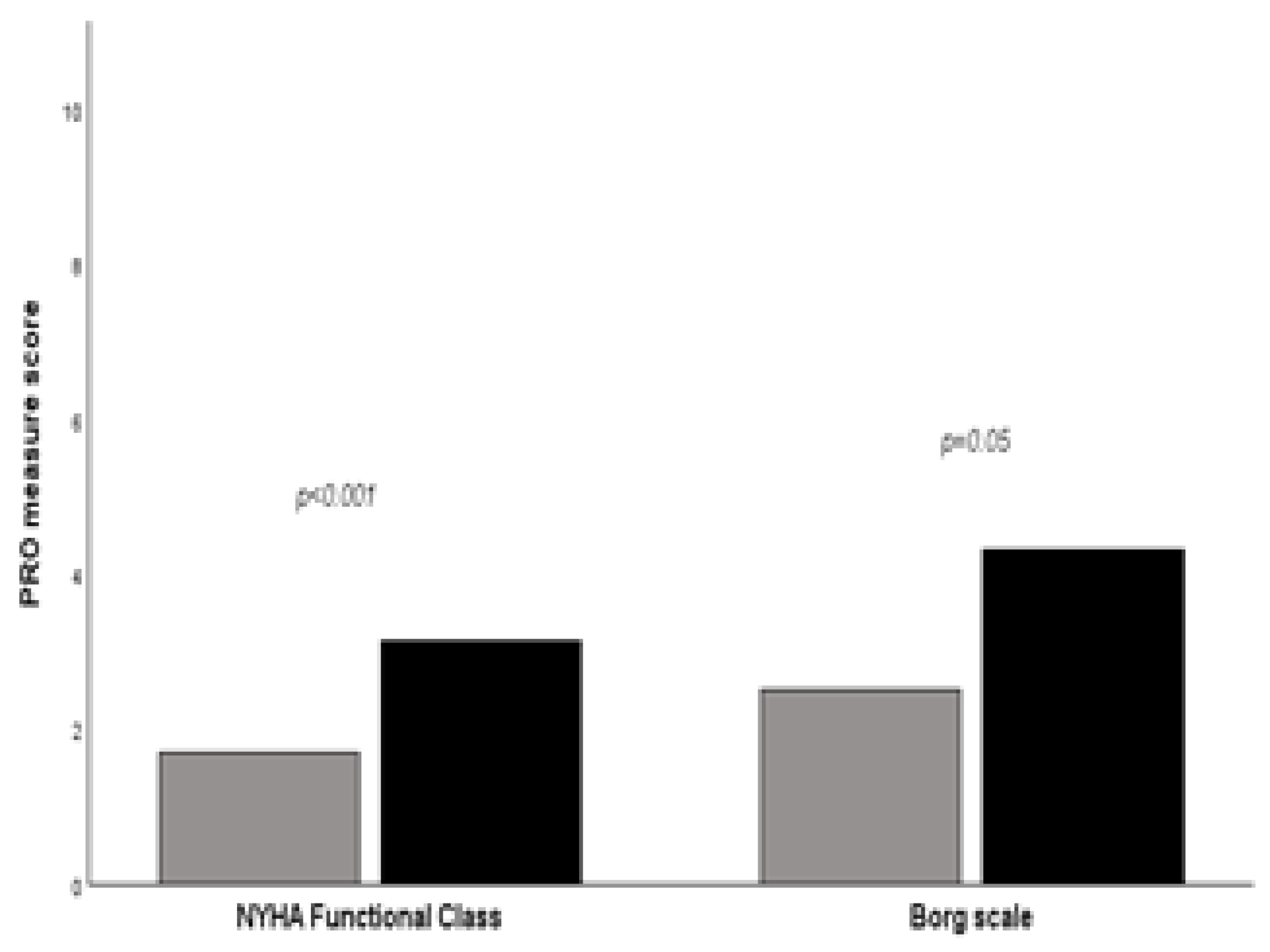

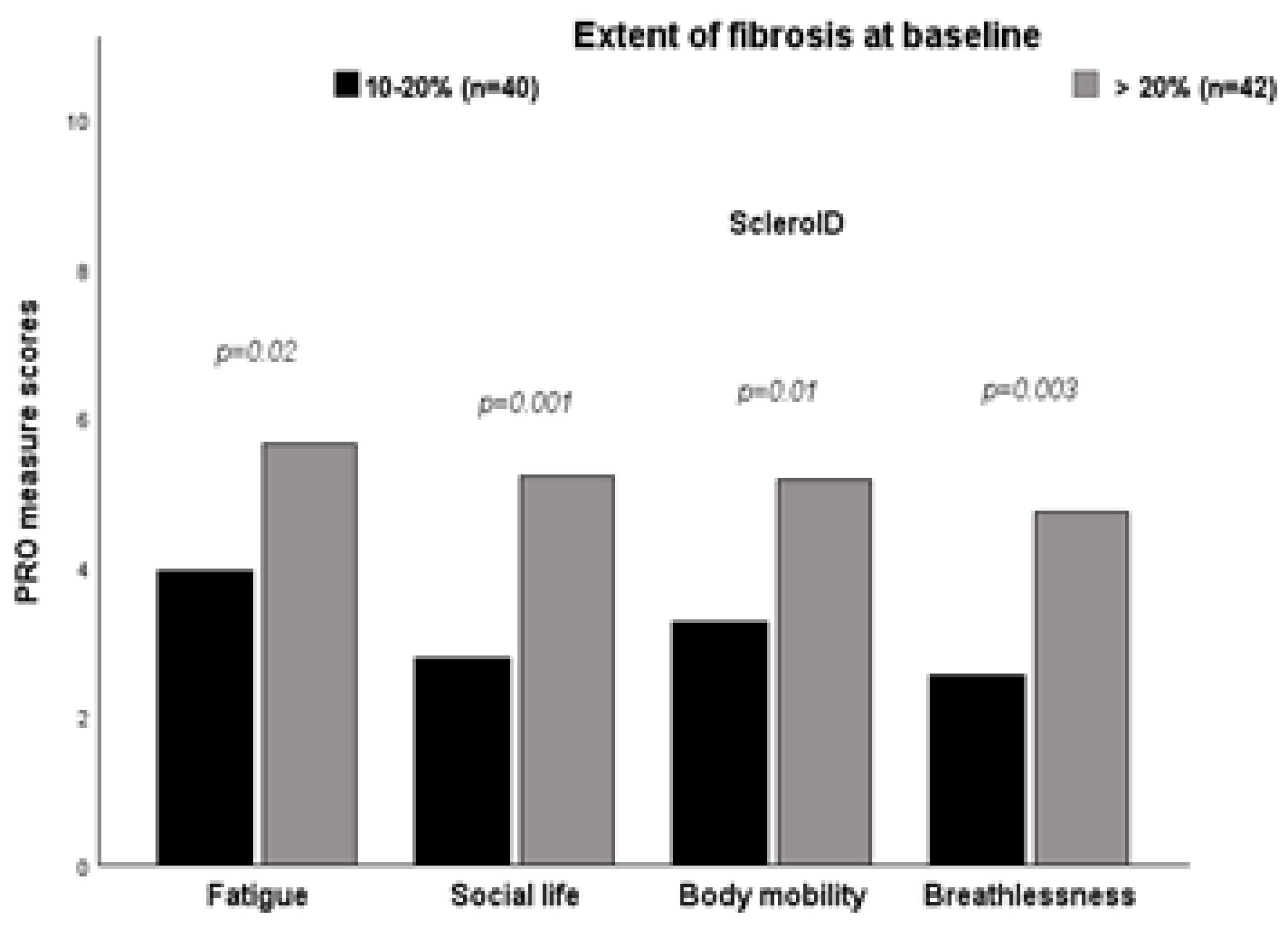

Patients with ≥ 20% fibrosis on HRCT at baseline reported worse mean scores in most ScleroID items than those between 10-20%, again reflecting worse QoL in patients with more severe disease: Fatigue 5.56 vs 3.97 (p=0.02), Social life 5.23 vs 2.88 (p=0.001), Body mobility 5.10 vs 3.32 (p=0.01), Breahlesness 4.64 vs 2.61 (p=0,003). Similarly, NYHA functional class and worst Borg scale during the 6-MWD reported worse mean scores (

Figure 1).

2.3.2. Cross-sectional Associations Between ScleroID Items and Baseline Lung Parameters

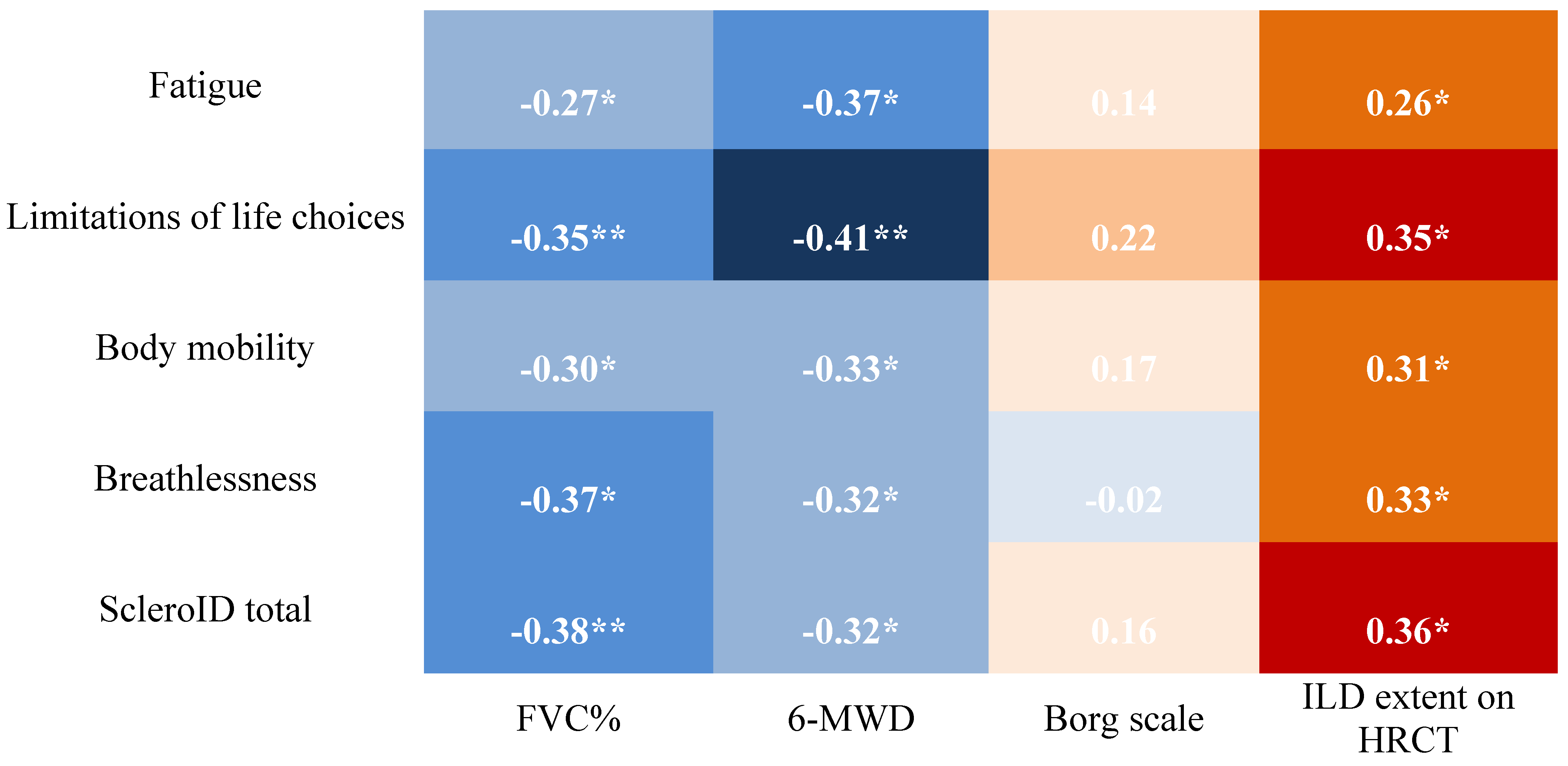

Higher ScleroID scores were associated with worse lung function and exercise capacity, reflected by lower FVC% and shorter 6-minute walk distance. In addition, both total and individual ScleroID items showed positive associations with ILD extent on HRCT, indicating that greater patient-reported disease impact corresponds not only to functional impairment but also to more extensive radiographic lung involvement (

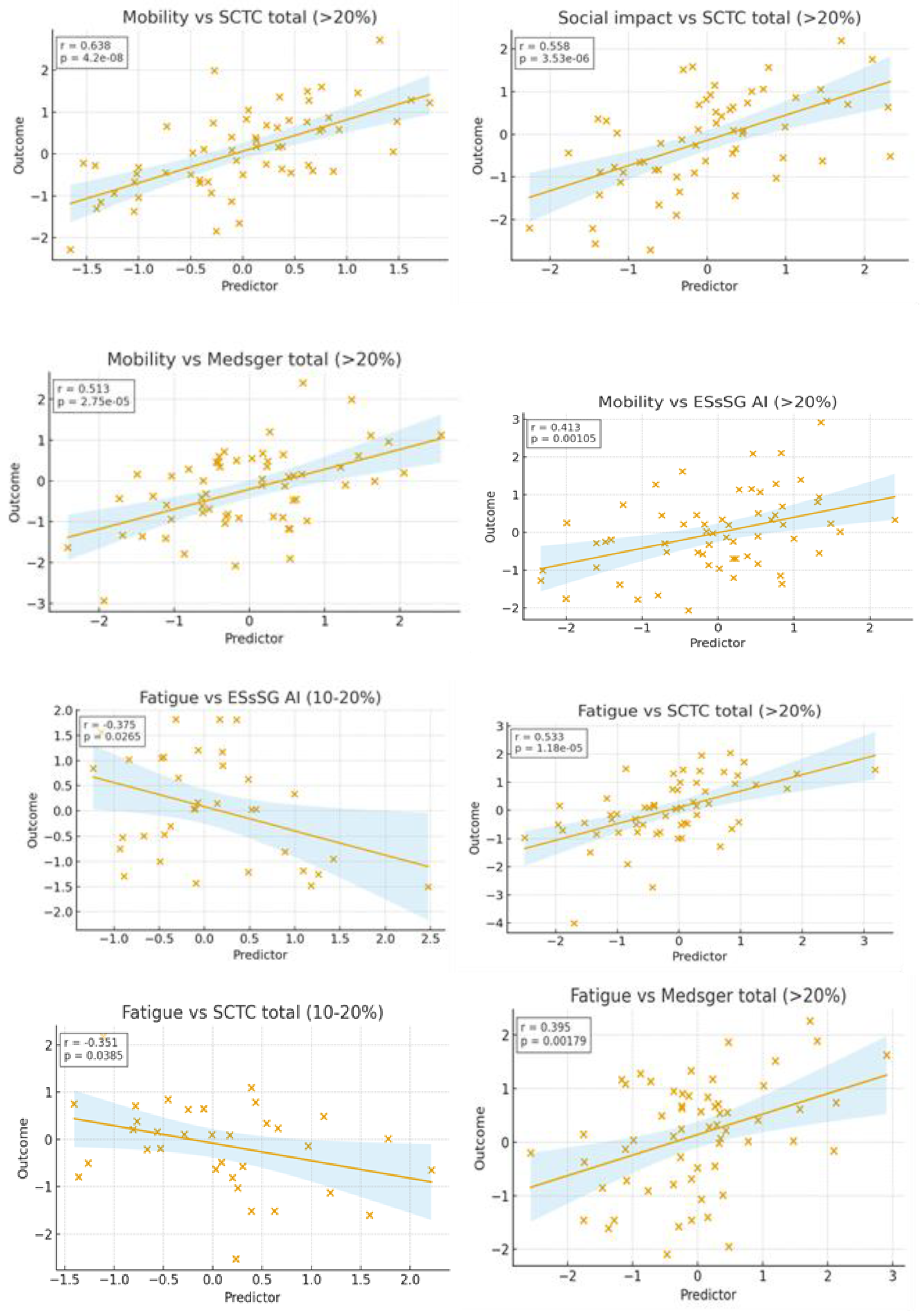

Figure 2).

Stratifying patients based on the extent of lung fibrosis showed that ScleroID domains (fatigue, social impact, mobility, and breathlessness) were strongly interrelated in both subgroups. In patients with 10–20% and >20% fibrosis, fatigue correlated with social impact (r = 0.700 vs. 0.686, p < 0.001), mobility (r = 0.618 vs. 0.778, p < 0.001), and breathlessness (r = 0.598 vs. 0.737, p < 0.001), and mobility correlated with breathlessness (r = 0.772 vs. 0.588, p < 0.001). NYHA class was consistently associated with fatigue (r = 0.466 in both groups) and, in the >20% group, also with social impact (r = 0.608, p < 0.001) and mobility (r = 0.568, p < 0.001). Differences emerged in functional correlations: in the 10–20% group, mobility and breathlessness were linked to exercise-induced desaturation (r = –0.561 and –0.602) and worst Borg scores (r = 0.641 and 0.531), whereas in the >20% group, correlations with FVC% and 6-MWD remained weak. Overall, the pattern of interrelated symptoms and associations with NYHA was similar across subgroups, but exercise-induced limitation and perceived exertion were more pronounced in patients with 10–20% fibrosis.

2.3.3. Impact of SSc Disease Activity and Damage on QoL in the Studied SSc-ILD Cohort

Regarding the correlation between disease activity, severity, and ScleroID, fatigue, social impact, and mobility were the domains most related to activity and severity scores. In patients with >20% fibrosis, fatigue correlated with Medsger total (r = 0.373, p = 0.019), mobility with ESsSG AI (r = 0.384, p = 0.016) and Medsger total (r = 0.525, p < 0.001), and all three domains correlated with SCTC total (r = 0.515–0.635, all p < 0.001). In the 10–20% group, correlations were weak or absent, with fatigue showing only weak negative correlations with SCTC total (r = –0.341, p = 0.045) and ESsSG AI (r = –0.359, p = 0.034). Breathlessness showed minimal associations in both groups (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated baseline patient-reported outcomes using ScleroID in a cohort of SSc patients with varying degrees of ILD, examining their associations with clinical measures of disease activity, organ involvement, and QoL. Our findings provide novel insights into how patient-perceived disease impact aligns—or sometimes diverges—from objective measures of organ involvement and functional status.

Functional impairments, such as NYHA class > III dyspnea and FVC < 80% predicted, were associated with higher ESsSG-AI scores, underscoring the influence of pulmonary function on both clinician-assessed and patient-reported disease activity. Interestingly, even in patients with significant pulmonary involvement—such as those with FVC below 80% predicted or experiencing a decline greater than 10%—the mean ScleroID score remained relatively low (4.8 ± 2.3). This suggests that factors beyond objective pulmonary function contribute to patient-reported outcomes in SSc. Paradoxically, patients with less severe dyspnea (NYHA class < III) sometimes reported higher ScleroID scores, highlighting the complex interplay between symptoms, perception, and disease burden.

Overall, higher ScleroID scores corresponded to greater fatigue, reduced mobility, social limitations, and breathlessness, highlighting the tool’s sensitivity to patient-perceived disease burden and quality of life, independent of objective lung function or fibrosis extent. In our cohort, ScleroID reliably reflected the patient-perceived impact of SSc-associated ILD (SSc-ILD) across all stages of lung fibrosis. In patients with 10–20% fibrosis, correlations with objective measures such as FVC% and 6-MWT were generally weak, whereas associations with exercise-induced desaturation and Borg scores were more pronounced. This suggests that in early-to-moderate fibrosis, patients primarily experience disease impact through symptoms and functional limitations rather than ventilatory impairment alone. In patients with >20% fibrosis, ScleroID scores were strongly interrelated and clearly associated with NYHA class, yet correlations with FVC% and 6-MWT remained modest. This indicates that even in more extensive lung involvement, ScleroID primarily captures patient-perceived limitations and quality of life rather than radiographic or physiological severity. Overall, these findings demonstrate that higher ScleroID scores correspond to greater fatigue, mobility and social limitations, and breathlessness, highlighting the tool’s sensitivity to patient-reported disease burden independently of objective pulmonary function. These observations align with prior studies emphasizing that patient-reported outcomes provide complementary insights to traditional measures, particularly in chronic, multisystem diseases such as SS [

28,

38,

39,

40].

In both fibrosis subgroups, ScleroID domains—fatigue, social impact, mobility limitations, and breathlessness—were strongly interrelated, indicating that SSc patients experience a coherent construct of disease burden. The EULAR ScleroID has been compared with other PROMs, demonstrating its validity and reliability in capturing the disease impact in SSc patients [

22]. The EULAR Systemic Sclerosis Impact of Disease (ScleroID) questionnaire serves as a comprehensive patient-reported outcome measure, capturing the multifaceted impact of systemic sclerosis (SSc) on patients' lives. Our findings indicate that ScleroID domains exhibit stronger correlations with disease activity and severity in patients with greater than 20% fibrosis, while such correlations are weaker or absent in those with 10–20% fibrosis. Fatigue emerged as a significant correlate of disease activity in the >20% fibrosis subgroup, with a moderate positive correlation to the Medsger total score (r = 0.373, p = 0.019). This aligns with previous studies highlighting fatigue as a prevalent and debilitating symptom in SSc, significantly affecting patients' quality of life and social participation [

41].

The association between fatigue and disease activity underscores its importance as a clinical indicator, particularly in advanced stages of fibrosis. Mobility demonstrated a strong positive correlation with both the Medsger total score (r = 0.525, p < 0.001) and the ESsSG AI (r = 0.384, p = 0.016) in the >20% fibrosis group. This finding is consistent with research indicating that musculoskeletal complications, including contractures and muscle weakness, significantly impair mobility and diminish quality of life in SSc patients [

42]. The robust relationship between mobility and disease severity in advanced fibrosis stages highlights the utility of mobility assessments in monitoring disease progression. The social impact domain exhibited moderate to strong positive correlations with the SCTC total score (r = 0.515–0.635, all p < 0.001) in patients with >20% fibrosis. The interplay between fatigue and social impact underscores the broader implications of disease activity on patients' social well-being, particularly in advanced stages of fibrosis. In contrast, patients with 10–20% fibrosis exhibited weak or absent correlations between ScleroID domains and clinical measures of disease activity and severity. Notably, fatigue showed only weak negative correlations with the SCTC total (r = –0.341, p = 0.045) and ESsSG AI (r = –0.359, p = 0.034). These findings suggest that in the early to moderate stages of fibrosis, the impact of disease activity on patient-reported outcomes may be less pronounced, potentially due to the compensatory mechanisms or subclinical manifestations characteristic of these stages. Breathlessness demonstrated minimal associations with disease activity and severity in both fibrosis subgroups.

Figure 3.

Relationship Between ScleroID Domains (Fatigue, Mobility, Social Impact) and Disease Activity/Severity Scores Stratified by Skin Fibrosis Extend

Figure 3.

Relationship Between ScleroID Domains (Fatigue, Mobility, Social Impact) and Disease Activity/Severity Scores Stratified by Skin Fibrosis Extend

This may be attributed to the relatively preserved pulmonary function in patients with <20% fibrosis, as indicated by studies showing no significant difference in ScleroID scores between patients with forced vital capacity (FVC) ≤80% and those with FVC >80% [

40]. The limited impact of pulmonary involvement on disease activity in early fibrosis stages may account for the weak correlations observed. The differential correlations observed between ScleroID domains and disease activity across fibrosis subgroups have important implications for clinical practice. In patients with >20% fibrosis, ScleroID domains, particularly fatigue, mobility, and social impact, serve as valuable indicators of disease activity and severity, aiding in monitoring disease progression and informing treatment strategies. Conversely, in patients with 10–20% fibrosis, clinicians may consider supplementing ScleroID assessments with other measures to capture the subtler manifestations of disease activity characteristic of this stage.

This study has several limitations. First, the analysis was based on baseline, cross-sectional data, which limits the ability to infer causal relationships between ScleroID scores and disease progression. Second, the sample sizes of fibrosis-based subgroups were relatively small, which may affect statistical power and generalizability. Additionally, ScleroID is a patient-reported outcome measure, and scores may be influenced by psychosocial factors or comorbidities not captured in this study. Finally, not all clinical manifestations and functional parameters (e.g., high-resolution imaging or specific inflammatory markers) were included, which may limit the comprehensive interpretation of correlations with disease activity and severity.

5. Conclusions

PROMs provide essential insights into the broad impact of SSc, especially in patients with early to moderate ILD. The ScleroID tool captures key aspects of disease burden—fatigue, mobility limitations, and social participation—that are often overlooked by traditional clinical measures. Even when lung function appears preserved, PROs reveal significant patient-perceived limitations, highlighting the importance of including subjective assessments in routine care to support personalized management.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization LG.; methodology LG,CN.; software CN.; validation LG.; formal analysis CN.; resources CN.; data curation LG.; writing—original draft preparation CN.; writing—review and editing, CN.; visualization LG.; supervision LG.; project administration LG.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

IRB Number:41520

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

dr Catalina Boromiz, Prof dr Andra Balanescu

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

SSc- systemic sclerosis

PFR – pulmonary function tests

HRCT - high-resolution CT

PRO- Patient-reported outcomes

ILD – interstitial lung disease

EScSG-AI - European Scleroderma Study Group Activity Index

SCTC-AI- Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium Activity Index

MSS - Medsger severity scale

FVC- forced volume capacity

DLCO – diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide

ATA- antitopoisomerase 1 antibodies

6- MWT - 6 minutes walkink test

QoL- quality of life

ScleroID - EULAR Systemic Sclerosis Impact of Disease

RHC – right heart catheterization

PH – pulmonary arterial hypertension

NYHA – New York Heart Association

dcSSc- diffuse cutaneous form of systemic sclerosis

lcSSc – limited cutaneous form of systemic sclerosis

References

- llanore Y, Simms R, Distler O, Trojanowska M, Pope J, Denton CP, et al. Systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 23 aprilie 2015;1(1):15002. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann-Vold AM, Petelytska L, Fretheim H, Aaløkken TM, Becker MO, Jenssen Bjørkekjær H, et al. Predicting the risk of subsequent progression in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease with progression: a multicentre observational cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. iulie 2025;7(7):e463-71. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Wallace L, Patnaik P, Alves M, Gahlemann M, Kohlbrenner V, et al. Disease frequency, patient characteristics, comorbidity outcomes and immunosuppressive therapy in systemic sclerosis and systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease: a US cohort study. Rheumatology. 6 aprilie 2021;60(4):1915-25. [CrossRef]

- Boleto G, Santiago T, Sieiro Santos C. Editorial: Advances in understanding and managing systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease: bridging prognostic biomarkers to therapeutic innovations. Front Med. 16 septembrie 2025;12:1683554. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann-Vold AM, Allanore Y, Bendstrup E, Bruni C, Distler O, Maher TM, et al. The need for a holistic approach for SSc-ILD – achievements and ambiguity in a devastating disease. Respir Res. decembrie 2020;21(1):197. [CrossRef]

- Valentini G, Bencivelli W, Bombardieri S, D’Angelo S, Della Rossa A, Silman AJ, et al. European Scleroderma Study Group to define disease activity criteria for systemic sclerosis. III. Assessment of the construct validity of the preliminary activity criteria. Ann Rheum Dis. septembrie 2003;62(9):901-3. [CrossRef]

- Ross L, Hansen D, Proudman S, Khanna D, Herrick AL, Stevens W, et al. Development and Initial Validation of the Novel Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium Activity Index. Arthritis Rheumatol. noiembrie 2024;76(11):1635-44. [CrossRef]

- Medsger TA, Silman AJ, Steen VD, Black CM, Akesson A, Bacon PA, et al. A disease severity scale for systemic sclerosis: development and testing. J Rheumatol. octombrie 1999;26(10):2159-67.

- Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P. A Self-complete Measure of Health Status for Chronic Airflow Limitation: The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis. iunie 1992;145(6):1321-7. [CrossRef]

- Sinha A, Patel AS, Siegert RJ, Bajwah S, Maher TM, Renzoni EA, et al. The King’s Brief Interstitial Lung Disease (KBILD) questionnaire: an updated minimal clinically important difference. BMJ Open Respir Res. februarie 2019;6(1):e000363. [CrossRef]

- Hinchcliff M, Beaumont JL, Thavarajah K, Varga J, Chung A, Podlusky S, et al. Validity of two new patient-reported outcome measures in systemic sclerosis: Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system 29-item health profile and functional assessment of chronic illness therapy–dyspnea short form. Arthritis Care Res. noiembrie 2011;63(11):1620-8. [CrossRef]

- Mchorney CA, Johne W, Anastasiae R. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and Clinical Tests of Validity in Measuring Physical and Mental Health Constructs. Med Care. martie 1993;31(3):247-63. [CrossRef]

- Allanore Y, Bozzi S, Terlinden A, Huscher D, Amand C, Soubrane C,; EUSTAR Collaborators. Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI) use in modelling disease progression in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: an analysis from the EUSTAR database. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020 Oct 28;22(1):257. [CrossRef]

- Fisher CJ, Namas R, Seelman D, Jaafar S, Homer K, Wilhalme H, et al. Reliability, construct validity and responsiveness to change of the PROMIS-29 in systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37 Suppl 119(4):49-56.

- Distler O, Highland KB, Gahlemann M, Azuma A, Fischer A, Mayes MD, et al. Nintedanib for Systemic Sclerosis–Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. N Engl J Med. 27 iunie 2019;380(26):2518-28. [CrossRef]

- Merkel PA, Herlyn K, Martin RW, Anderson JJ, Mayes MD, Bell P, et al. Measuring disease activity and functional status in patients with scleroderma and Raynaud’s phenomenon. Arthritis Rheum. septembrie 2002;46(9):2410-20. [CrossRef]

- Khanna D, Tseng CH, Furst DE, Clements PJ, Elashoff R, Roth M, et al. Minimally important differences in the Mahler’s Transition Dyspnoea Index in a large randomized controlled trial--results from the Scleroderma Lung Study. Rheumatology. 1 decembrie 2009;48(12):1537-40. [CrossRef]

- Birring SS. Development of a symptom specific health status measure for patients with chronic cough: Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ). Thorax. 1 aprilie 2003;58(4):339-43. [CrossRef]

- Witek TJ, Mahler DA. Minimal important difference of the transition dyspnoea index in a multinational clinical trial. Eur Respir J. februarie 2003;21(2):267-72. [CrossRef]

- Ponniah T, Wong CK, Ng CM, Raja J. Quality of life in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease and its association with respiratory clinical parameters. J Scleroderma Relat Disord. 24 februarie 2025;23971983251318827. [CrossRef]

- Orphanet: ATHENA-SSc-ILD: A Double Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of PRA023 in Subjects with Systemic Sclerosis Associated with Interstitial Lung Disease (SSc-ILD) - PL [Internet]. [citat 30 septembrie 2025]. Disponibil la: http://www.orpha.net/en/research-trials/clinical-trial/674705?country=&mode=&name=&recruiting=0&terminated=0.

- Becker MO, Dobrota R, Garaiman A, Debelak R, Fligelstone K, Tyrrell Kennedy A, et al. Development and validation of a patient-reported outcome measure for systemic sclerosis: the EULAR Systemic Sclerosis Impact of Disease (ScleroID) questionnaire. Ann Rheum Dis. aprilie 2022;81(4):507-15. [CrossRef]

- Johnson SR, Bernstein EJ, Bolster MB, Chung JH, Danoff SK, George MD, et al. 2023 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) Guideline for the Treatment of Interstitial Lung Disease in People with Systemic Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases. Arthritis Care Res. august 2024;76(8):1051-69. [CrossRef]

- Antoniou KM, Distler O, Gheorghiu AM, Moor CC, Vikse J, Bizymi N, et al. ERS/EULAR clinical practice guidelines for connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease developed by the task force for connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease of the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) Endorsed by the European Reference Network on rare respiratory diseases (ERN-LUNG). Ann Rheum Dis. septembrie 2025;S0003496725043201. [CrossRef]

- Van Den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. noiembrie 2013;72(11):1747-55. [CrossRef]

- Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: Glossary of Terms for Thoracic Imaging. Radiology. martie 2008;246(3):697-722. [CrossRef]

- Quanjer PhH, Tammeling GJ, Cotes JE, Pedersen OF, Peslin R, Yernault JC. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Eur Respir J. 1 martie 1993;6(Suppl 16):5-40.

- Tennøe AH, Murbræch K, Andreassen JC, Fretheim H, Garen T, Gude E, et al. Left Ventricular Diastolic Dysfunction Predicts Mortality in Patients With Systemic Sclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. octombrie 2018;72(15):1804-13. [CrossRef]

- Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS)Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J. 1 ianuarie 2016;37(1):67-119. [CrossRef]

- Goh NS, Hoyles RK, Denton CP, Hansell DM, Renzoni EA, Maher TM, et al. Short-Term Pulmonary Function Trends Are Predictive of Mortality in Interstitial Lung Disease Associated With Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. august 2017;69(8):1670-8. [CrossRef]

- Khanna D, Mittoo S, Aggarwal R, Proudman SM, Dalbeth N, Matteson EL, et al. Connective Tissue Disease-associated Interstitial Lung Diseases (CTD-ILD) — Report from OMERACT CTD-ILD Working Group. J Rheumatol. noiembrie 2015;42(11):2168-71. [CrossRef]

- Zappala CJ, Latsi PI, Nicholson AG, Colby TV, Cramer D, Renzoni EA, et al. Marginal decline in forced vital capacity is associated with a poor outcome in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 1 aprilie 2010;35(4):830-6. [CrossRef]

- Dobrota R, Becker MO, Fligelstone K, Fransen J, Tyrrell Kennedy A, Allanore Y, et al. AB0787 The eular systemic sclerosis impact of disease (SCLEROID) score – a new patient-reported outcome measure for patients with systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. iunie 2018;77:1527. [CrossRef]

- Van Den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. noiembrie 2013;72(11):1747-55. [CrossRef]

- Allanore Y, Simms R, Distler O, Trojanowska M, Pope J, Denton CP, et al. Systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 23 aprilie 2015;1(1):15002. [CrossRef]

- LeRoy EC, Medsger TA. Criteria for the classification of early systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. iulie 2001;28(7):1573-6.

- ATS Statement: Guidelines for the Six-Minute Walk Test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1 iulie 2002;166(1):111-7. [CrossRef]

- Higuero Sevilla JP, Memon A, Hinchcliff M. Learnings from clinical trials in patients with connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Res Ther. 8 iulie 2023;25(1):118. [CrossRef]

- Kreuter M, Hoffmann-Vold AM, Matucci-Cerinic M, Saketkoo LA, Highland KB, Wilson H, et al. Impact of lung function and baseline clinical characteristics on patient-reported outcome measures in systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology. 6 februarie 2023;62(SI):SI43-53. [CrossRef]

- Nagy G, Dobrota R, Becker MO, Minier T, Varjú C, Kumánovics G, et al. Characteristics of ScleroID highlighting musculoskeletal and internal organ implications in patients afflicted with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther. 20 mai 2023;25(1):84. [CrossRef]

- Murphy SL, Kratz AL, Whibley D, Poole JL, Khanna D. Fatigue and Its Association With Social Participation, Functioning, and Quality of Life in Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res. martie 2021;73(3):415-22. [CrossRef]

- Pellar RE, Tingey TM, Pope JE. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Systemic Sclerosis (Scleroderma). Rheum Dis Clin N Am. mai 2016;42(2):301-16. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).