1. Introduction

Agriculture has historically represented the economic, social, and symbolic foundation of territories and their communities. Since as early as the 8th century B.C., with the emergence and consolidation of the Greek polis model, land ownership was regarded not only as a means of subsistence but also as a fundamental component of civic identity and political power. Although institutional frameworks and territorial organization have profoundly evolved over the centuries, the relationship between land governance and agricultural use has remained central in many Mediterranean cultures. Consequently, agricultural activity has played a decisive role in shaping territorial morphology, settlement patterns, and the cultural values associated with them, as elements deeply embedded in collective perception. This historical relationship between agriculture and landscape is further reinforced by the European Landscape Convention (ELC) [

1], which redefines the concept of landscape beyond the traditional view as a mere outcome of human–nature interaction. The Convention emphasizes its central role in sustainable development and in safeguarding territorial identity. By asserting that “no people, no landscape,” the ELC introduced a new vision of territorial governance, positioning the landscape, conceived as a

part of the territory shaped by human action, as a key component of quality of life for local communities, in both urban and rural areas, and across degraded as well as exceptional environments [

2].

The landscape thus emerges as a bearer of identity and intangible values, such as narratives, knowledge systems, and traditions, classified as Cultural Ecosystem Services (CES) [

3]. This renewed conceptualization, combined with profound socio-ecological transformations intensified by climate change, underscores the urgent need for a paradigm shift in landscape planning and sustainable management across multiple scales, grounded in an inclusive, transdisciplinary approach. The Nature Restoration Law, recently adopted by the European Parliament [

4], strengthens the strategic framework for climate action and biodiversity conservation within the EU Green Deal, setting the goal of restoring at least 20% of the EU’s terrestrial and marine ecosystems by 2030. Within this framework, the ecological reinterpretation of spatial and urban planning redefines the landscape, an inherently interdisciplinary system integrating multiple ecosystem values [

5], as a central component in strategies for the restoration, protection, and enhancement of natural, rural and human-made environments [

6]. Achieving these objectives requires the development of more adaptive and flexible planning models than those traditionally adopted. Such models emphasize performance-based assessments of ecosystem functions [

7], enabling planners to address the growing complexity of territorial transformation processes in which landscape systems are deeply intertwined [

8].

This calls for a rethinking of two key dimensions:

a) Spatial, through the definition of new value and quality criteria for landscape assessment, consistent with evolving economic, environmental, social and cultural conditions [

9]; and b) Regulatory, through the promotion of strategic and programmatic approaches over rigid prescriptive frameworks, facilitating the implementation of innovative planning and management tools, such as Nature-Based Solutions (NBS), to enhance the adaptability and resilience of urban and rural systems. Regarding both the ecological and productive dimensions of rural landscapes, ecosystem-based mapping of environmental, historical, cultural and identity-related values enables planners to: a) detect spatial variations in landscape value based on newly defined criteria and indicators; b) develop targeted strategies for conservation and enhancement; and c) design restoration actions in degraded or low-value areas, turning them into opportunities for landscape regeneration and recomposition [

10]. Working with a spatially localized value scale allows the formulation of management strategies that integrate nature-based interventions and climate-smart agricultural practices, both essential to reinforcing the resilience of complex agri-productive systems [

11].

In high-value areas, the integration of traditional elements with innovative components is crucial to ensuring profitability, enhancing local production, maintaining human and social capital, and preserving the defining features of traditional landscapes in the face of increasingly frequent extreme events.

1.1. A New Approach to the Landscape Plan for the Marche Region: from PPAR 1989 to PPR 2025

Following the entry into force of Regional Law No. 19/2023, the Marche Region (

Figure 1) has initiated the revision of its

Regional Environmental Landscape Plan [

12] to develop the new

Regional Landscape Plan (PPR).

This update is driven by two main factors previously discussed: (a) the profound social and ecological transformations amplified by climate change, and (b) the conceptual evolution of landscape, starting from the preservation-oriented and defensive perspective of the 1922 Landscape Law to the inclusive vision introduced by the European Landscape Convention (2000), which conceives landscape as both the outcome of human–nature interactions and a vital component of community identity and well-being.

The

Cultural Heritage Code (Legislative Decree 42/2004), together with the recent Regional Law No. 19/2023, further consolidates this perspective, assigning the PPR the mandate to identify, safeguard, plan, and manage the regional landscape through an integrated and sustainability-oriented approach [

13,

14].

In this perspective, the new Plan defines 20 Landscape Units, establishes quality objectives and prescriptions, and introduces binding rules across all levels of spatial planning. It moves beyond the sectoral and thematic orientation of the previous plan (primarily aesthetic and regulatory in nature) which proved inadequate to address the increasing complexity of contemporary social, ecological, and territorial dynamics in which landscapes are embedded. By adopting a systemic and relational approach, the new PPR conceives the entire regional territory as a landscape to be recognized, managed, and enhanced. This shift lays the foundation for an integrated, multidisciplinary, and quality-oriented approach to landscape planning, supported by analytical and interpretive tools such as the Landscape Atlas, SWOT analysis, and the definition of new landscape quality objectives. Serving as a strategic reference for the forthcoming Regional Spatial Plan, the PPR plays a pivotal role in limiting land consumption, mitigating climate change, and promoting urban and territorial regeneration. Moreover, it contributes to strengthening both ecological and social resilience through a transdisciplinary integration of expertise spanning architecture, agronomy, ecology, sociology, and urban planning.

1.2. Scope and Objectives of the Research

Within this regulatory and operational framework, the paper presents the results of an experimental study developed as part of the technical–scientific support provided to the Marche Region for the preparation of the new Regional Landscape Plan (PPR). Conducted by a multidisciplinary team comprising agronomists, botanists, and spatial planners, the research focuses on the revision of two key components of the regional historical rural landscape, which strengthen its structural framework, regulatory system, and guidelines for protection and enhancement. These components are represented through two spatial layers: a) the agricultural landscape of historical and environmental interest (Article 51 of the Planning Regulations); and b) the minor landscape features within the Landscape–Environmental Subsystem (Article 44 of the Planning Regulations). These correspond to the two fundamental landscape categories already established by the 1989 PPAR: the Historical–Cultural Subsystem and the Landscape–Environmental Subsystem.

Two major shortcomings were identified in the previous plan. The first concerned the lack of a structured knowledge base and a consistent methodological framework to support the identification and mapping of agricultural landscapes of cultural, historical, and identity relevance during the zoning phase. Consequently, the designated areas often failed to accurately reflect the traditional and identity-rich rural landscape of the Marche Region, unique in Italy for its diversity and for the mosaic of alternating cereal fields, vineyards, olive groves, and orchards that shape its rolling hills [

15], alongside a dense network of rural farmhouses embodying the legacy of the

mezzadria (sharecropping) system [

16], further discussed in the following section.

The second limitation related to the absence of georeferenced mapping and classification of minor landscape features within the agricultural landscape subsystem, such as hedgerows, riparian vegetation, mixed shrub formations, and isolated or linear tree features

The lack of such spatial information resulted in an oversimplified regulatory framework, where uniform restrictions derived from the regional forestry law were generally applied to all categories of landscape features. This undifferentiated approach ultimately proved ineffective, constraining ordinary agricultural practices (e.g., pruning, selective thinning) and undermining the maintenance of their ecological, environmental, productive, and structural functions. In contrast, European studies and policy frameworks on green and landscape infrastructures highlight that context-specific management and targeted interventions are essential to preserve the diversity and complexity of the agrarian mosaic—core attributes of local rural landscape identity [

17] and key contributors to biodiversity support [

18,

19]. From this perspective, outlining operational tools to support downscaling from the regionale to the city-scale, and the design of differentiated management strategies is essential to preserve the diversity and complexity of the agrarian landscape matrix, as well as the structural components of local rural and peri-urban landscapes [

20]. To address all these limitations, the main objective of this study is to develop and test an ecosystem-based methodology for integrating Cultural Ecosystem Services (CES) into regional landscape planning, proposing a new set of ecosystem-based quality indicators designed to enable a more coherent and spatially explicit assessment of landscape quality [

21].

The research identifies and maps high-value rural landscapes and proposes a performance-oriented framework by integrating the traditional visual, perceptual, and experiential approaches [

22], to guide adaptive management and policy design. The main outcomes include: a) the identification and geolocation of new high-value areas within the traditional hilly landscape of the Marche Region, resulting in innovative yet consistent cartographic representations aligned with the historical agrarian matrix shaped by the

mezzadria system, and b) the redefinition of landscape protection levels, leading to the revision of both prescriptive measures and qualitative guidelines. The Discussion section critically examines the methodological strengths and limitations of the research, while the Conclusion outlines the main findings and future perspectives for the operational application of the proposed framework.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study. The Marche Region’s Mezzadria System: Key Elements

Known as “mezzadria”, sharecropping in central Italy emerged in the thirteenth century as a unique partnership among landowners, tenants, and the labor force. This innovative arrangement quickly transformed agricultural practices and led to the development of a comprehensive territorial management model. It’s a fascinating example of collaboration and resilience in farming history. Its expansion was primarily driven by urban elites, whose ownership and administrative control over rural land symbolized the consolidation of urban dominance across the countryside [

23].

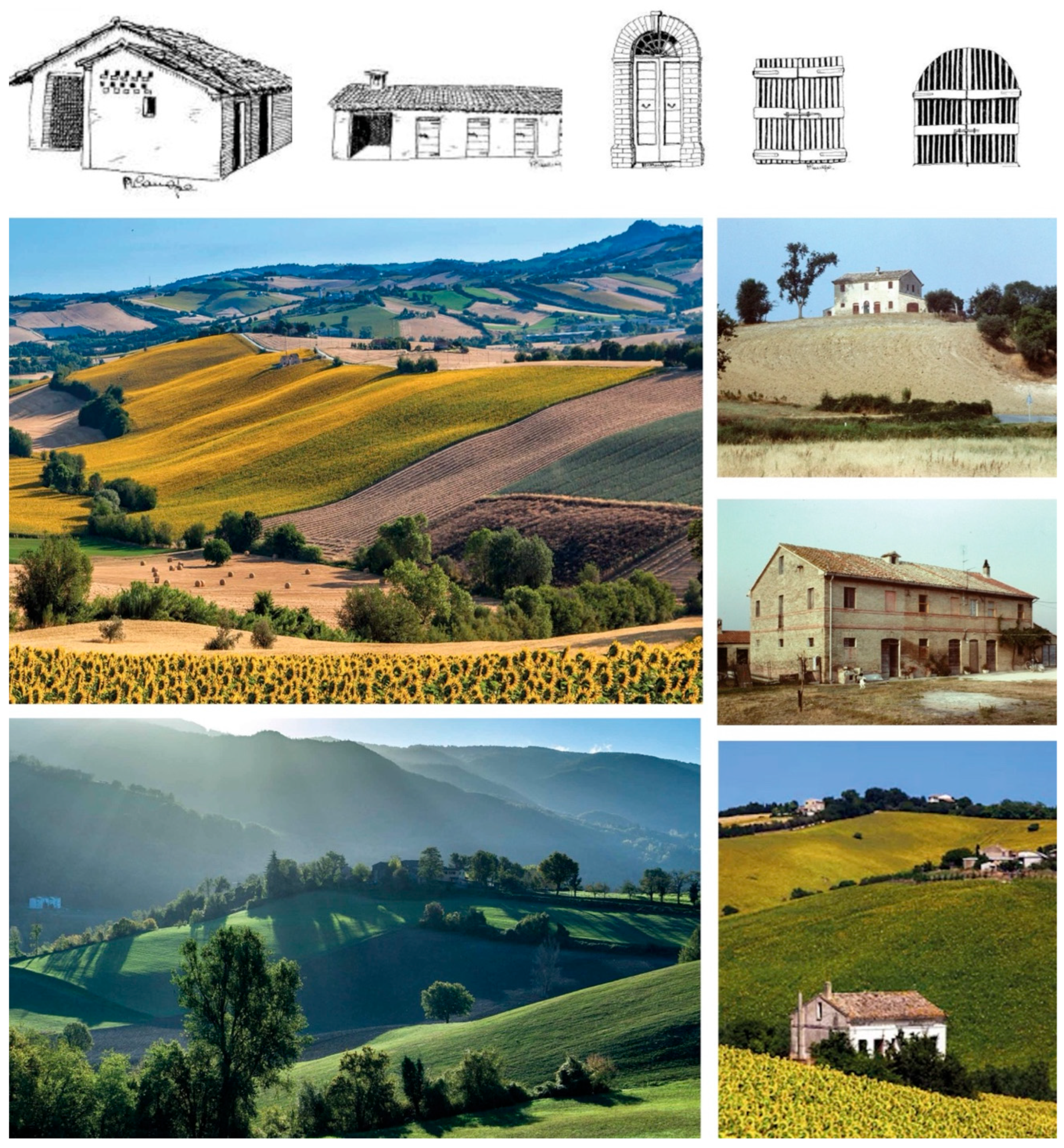

More than a mere mechanism for dividing agricultural yields equally between landlord and tenant,

mezzadria represented an integrated socio-economic structure centered on the

podere—a self-contained farmstead comprising a farmhouse inhabited by the tenant family. This organizational model fostered the development of a dense and finely articulated network of farms, initially characterized by large estates that gradually evolved into medium-sized holdings averaging approximately ten hectares. Each farm was managed by a sharecropping family whose composition and labor capacity were closely aligned with the productive requirements and spatial configuration of the holding (

Figure 2).

In the Marche Region, this contractual and land management model became predominant between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, driven by several interrelated factors: a) economic efficiency, as it relied on family-based labor for the continuous management of agricultural holdings; b) land value enhancement, associated with the process of appoderamento, the systematic parcelling of land and construction of farmsteads; and c) geo-pedological suitability, as it contributed to stabilizing clayey and erosion-prone soils through diversified cropping systems that required constant presence and labor, thereby promoting both territorial stewardship and soil conservation.

The mezzadria system, which persisted for centuries until its gradual dissolution in the mid-twentieth century, gave rise to a dense and finely articulated mosaic of farms.

Initially extensive, these holdings gradually decreased in size to an average of about ten hectares and were later fragmented into smaller plots ranging from three to five hectares. At the center of each

podere stood the farmhouse, serving as both a productive and residential core, and connected by countyroads (

strade bianche) to neighboring farmsteads and nearby villages. This long-standing management system, rooted in traditional agricultural practices, produced a distinctive rural landscape morphology along ridges and slopes: a complex, biodiverse

eco-mosaic composed of multifunctional systems integrating croplands, hedgerows, tree rows, and small woodlots. The interplay between human activity and natural dynamics typical of

mezzadria cultivation generated a distinctive mixed-farming landscape, characterized by alternating hydraulic and agricultural structures, small plots, crop rotations, and the prevalence of arable–vine systems (

Table 1).

This collective land management model produced, on the one hand, high ecological, landscape, and aesthetic resilience, but on the other, growing environmental fragility increasingly exposed to the effects of climate change.

Degradation processes such as erosion, landslides, and soil fertility loss, together with the decline of ecosystem services and the simplification of rural landscapes, call for a paradigm shift in landscape management, increasingly oriented toward risk and multi-hazard mitigation [

24]. In such context, hill areas with slopes exceeding 10–15% results as the most vulnerable: abandonment or unsustainable management practices can trigger severe environmental impacts. These dynamics, exacerbated by falling agricultural prices, low economic valorization of hillside products, and the reduction of skilled labor, have led to landscape simplification and a progressive loss of structural and functional diversity, eroding historical landscape features.

2.2. Identifying the Traditional Landscape of the Marche Region: a New Value Matrix

The proposed methodology relies on the selection of a set of indicators corresponding to georeferenced spatial layers representing specific land-use categories, cross-compared within geodatabases progressively developed over time (

Table 2).

The landscape components considered were classified into three main ecosystem-based categories:

Anthropic system, encompassing historical and identity-related invariants such as settlement structures and the rural road network;

Natural landscape system, including botanical and vegetational features such as hedgerows, groves, isolated trees, and riparian vegetation that shaped the cultivated hilly pattern;

Productive landscapes of vineyards and olive groves, representing traditional agricultural practices that have shaped the slopes and ridges.

The methodological framework integrates ecosystem-based theories, concepts, and indicators [

25] with the traditional approaches of landscape planning, grounded in the recognition of cultural, identity, and heritage values [[

26]. The selected indicators correspond to the structural elements that define the traditional agrarian landscape of the Marche hills, historically designed by the

mezzadria system, highlighting its identity, recognizability, and distinctiveness.

Each spatial layer was assigned a corresponding set of ecosystem values, with the historical–cultural and identity dimensions playing a particularly prominent role [

27]. This integration enables a more coherent and spatially explicit assessment of the rural landscape, bridging tangible and intangible components through an ecosystem-based analytical perspective.

These spatial layers were identified as the most suitable for redefining the landscape value system, ensuring continuity between tradition and innovation [

28].

A qualitative–quantitative analysis of landscape values was performed within a GIS environment and collected into a comprehensive digital dataset (

Figure 3).

To assess the distribution and concentration of point, linear and areal features belonging to both the rural and anthropic landscape, weighted according to their respective landscape values, a regular square grid model was applied, corresponding to a surface area of 2 hectares. This dimension represents the minimum historical unit of the family-managed mezzadrile podere, traditionally designed to guarantee household subsistence. Historically, the size of these farm units varied between 2 and 10 hectares, depending on family composition and productive capacity, reproducing the traditional polycultural matrix that characterizes the region’s historical rural landscape.

Each input dataset, corresponding to spatial layers selected as landscape value indicators, was assigned both a percentage weight (0–100%) and a ranking index (1–5) (

Table 3). This weighting process provided a standardized basis for evaluating the spatial significance and relative contribution of each indicator to the overall landscape value system.

2.3. Description of Spatial Layers and Input Data (see Table 2)

This category includes minor vegetational components structuring the agricultural landscape, such as woodlands, groves, riparian vegetation, hedgerows, and isolated trees—including mature or monumental specimens, as well as individual or clustered oaks. Anthropogenic vegetational features, such as rows of trees and roadside or field trees, were also incorporated when representative of historical or traditional planting forms (e.g., mulberries, olives, folignate systems).

Beyond their ecological functions - providing habitat, supporting biodiversity, sequestering carbon, and regulating hydrological and soil processes [

30] - these features also possess significant aesthetic, cultural, and identity value, as integral components of traditional agricultural practices and the region’s rural heritage. Their management is therefore essential to safeguard and preserve the typological and historical–identity characteristics of traditional landscapes.

From a technical perspective, the dataset includes linear structures (hedgerows ≤ 30 m wide and ≥ 30 m long) and point or areal features (scattered trees and small woodlots) covering areas between 200 m² and 5,000 m². Originally available as raster data with a 5 m spatial resolution, the dataset was converted into vector format through GIS-based geoprocessing, excluding urban and mountainous areas [

31] (

Figure 4).

In the Marche Region, the traditional farmhouses were considered multifunctional centers integrating production, storage, and domestic life within a single architectural unit. The sharecropping family represented both the social and economic core of the podere, embodying the self-sufficient model of the mezzadria system.

During this period, farmhouses evolved into complex and adaptive structures supporting diversified agricultural and household activities. Their form reflected both the functional needs of mixed farming and the cultural identity of the rural landscape. The size and layout of each farmhouse and its ancillary buildings were proportionate to the holding’s extent and labor capacity [

32]. The ratio between built-up area and cultivated land ranged from 13 to 34 m²/ha, depending primarily on productive efficiency, influenced by morpho-pedological conditions, management practices, and the performance of hydraulic–agricultural systems (

Figure 5).

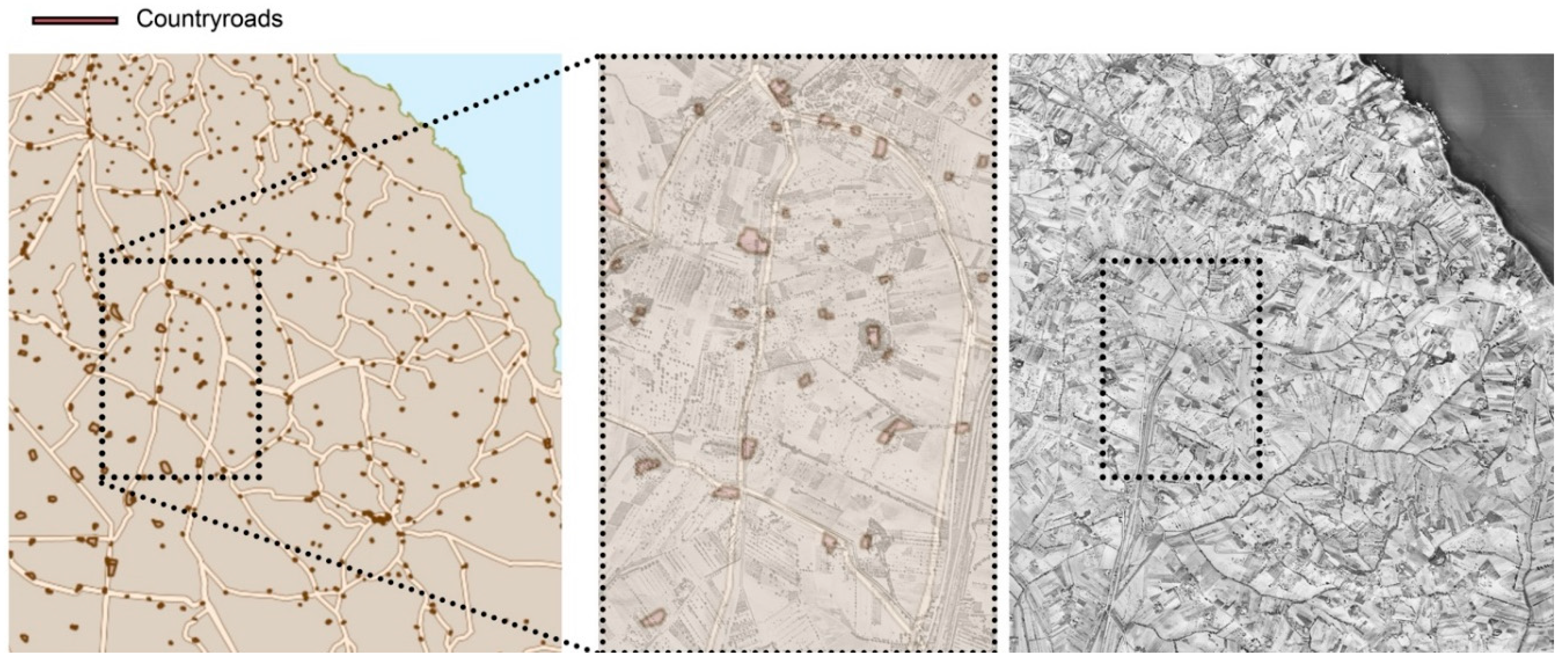

The network of country roads (strade bianche), linking farmhouses to one another and to nearby villages, constitutes a fundamental component of the appoderamento system and of the territorial organization established under the mezzadria model. These routes structured the spatial and social relationships of the rural landscape, supporting both agricultural management and community interaction.

The corresponding spatial layer was reconstructed using the earliest regional geodatabase, the 1984 Land Use Map of the Marche Region, which provides a reliable baseline for tracing the historical configuration and persistence of the rural road network (

Figure 6).

This category comprises permanent tree crops of vineyards and olive groves. In cases of intercropping with herbaceous species, the dominant cover type was used for classification. The corresponding spatial layers were derived from the Habitat Map of the Marche Region, produced by ISPRA (Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research) in 2022 at a 1:25,000 scale [

33]. Mapping was based on LANDSAT 7 ETM+ satellite imagery (25 × 25 m resolution), with a minimum cartographic unit of 1 hectare and exclusion of habitats narrower than 30 m. At the regional scale, photointerpretation identified approximately 15,000 hectares of vineyards and 13,100 hectares of olive groves, distributed across the entire Marche Region (

Figure 7).

This category includes areas cultivated with annual herbaceous crops, intercropped with fruit trees, vines, or olives. Such mixed-cropping systems have historically shaped the spatial architecture and visual harmony of the Marche agrarian landscape, contributing to its ecological and cultural complexity [

34]. Introduced as early as the sixteenth century to adapt to local geo-pedological constraints, these practices evolved during the eighteenth century into the characteristic

alberate or

folignate systems, where vines were trained on rows of trees such as elms or maples [

35].

3. Results

3.1. Updating the Ecosystem Values of the Marche region’s Rural Landscape

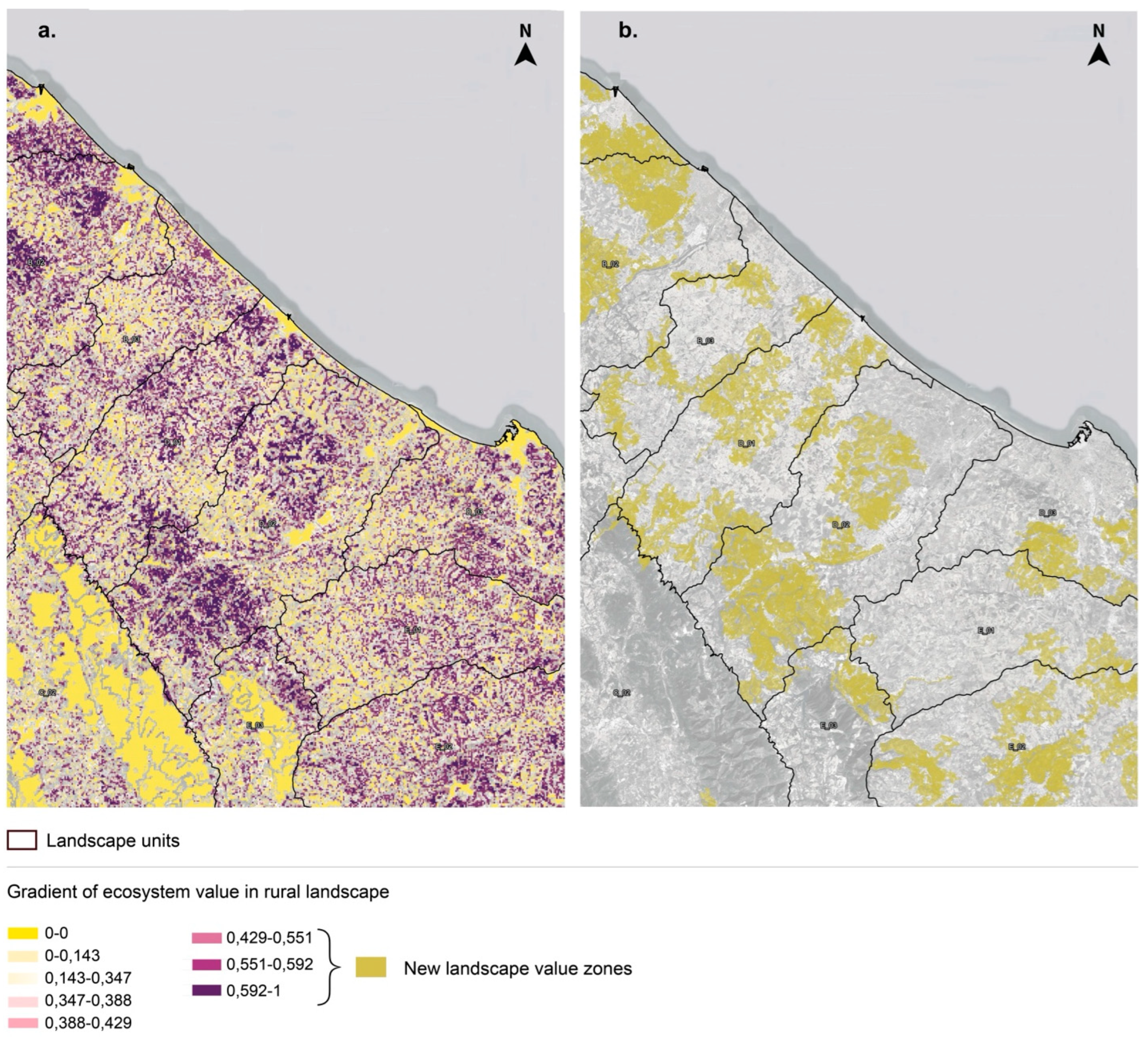

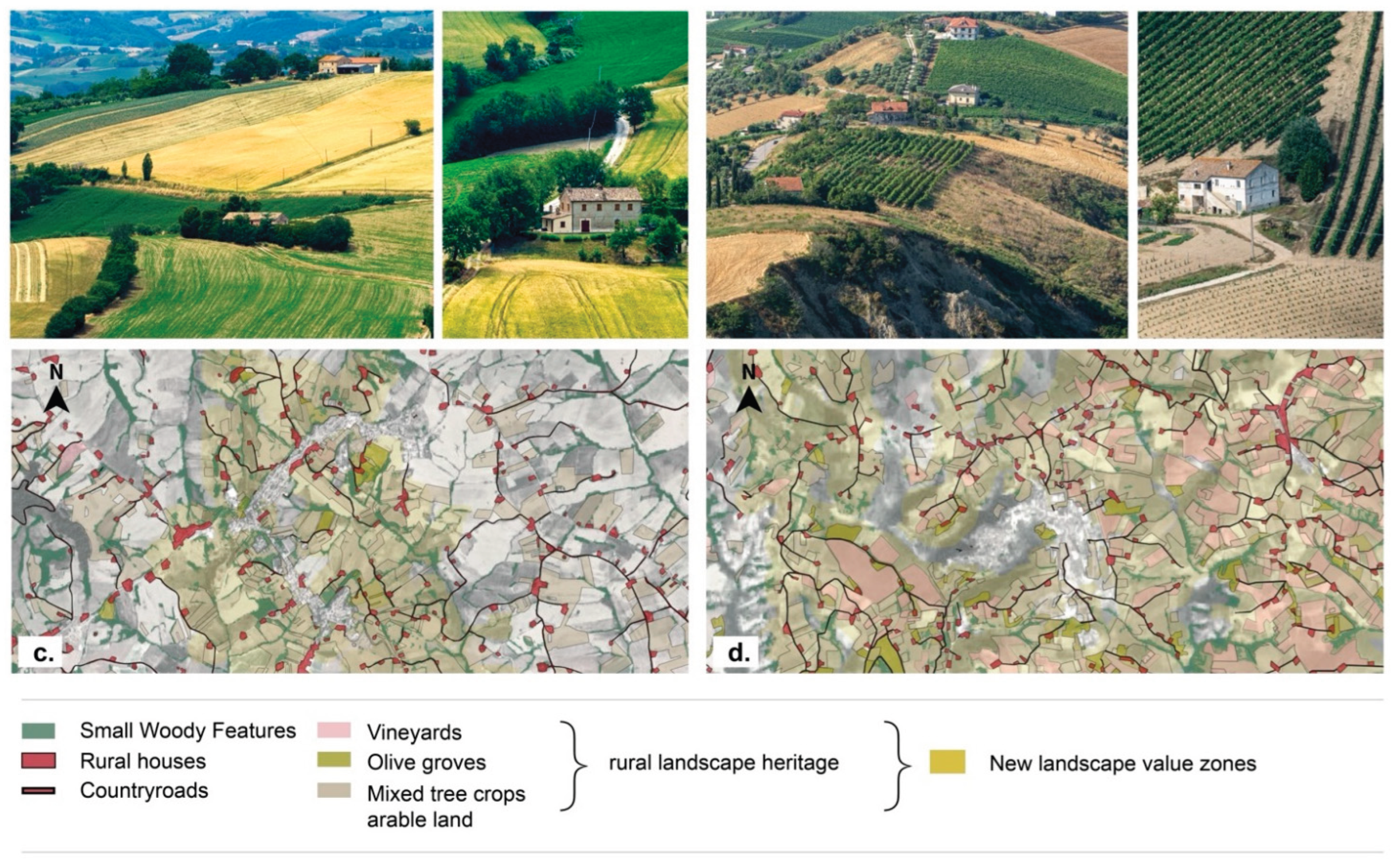

The spatial distribution of the six selected landscape–environmental value indicators, defined according to specific ecological and cultural criteria, enabled the identification of a gradient of spatially localized ecosystem values across the reference grid (

Figure 8a). Through a threshold-based classification, the highest value ranges were extracted to generate a new geospatial layer delineating high-value landscape areas, distributed in a relatively homogeneous pattern throughout the region (

Figure 8b). These newly mapped areas provide an updated interpretation of the traditional agrarian landscape historically shaped by the

mezzadria system, representing the most significant cultural, ecological, and identity components of the Marche Region.

Each identified level of ecosystem performance was then associated with specific management objectives, supporting the definition of differentiated strategies and targeted policies. These are intended to reconcile economic and productive innovation with the active conservation of the region’s landscape and environmental heritage (

Table 4).

The newly identified high-value areas present a widespread distribution across the intermediate hilly areas, characterized by a predominantly agricultural and productive vocation, located between the valley floors and the mountain zones (altitude > 600 m). The highest landscape and ecosystem values are concentrated in the mid- to upper-hill areas, where the complex structure of the historical poderi system has largely been preserved over time. In contrast, the mid- to low-hill areas have undergone progressive transformation, primarily due to the loss of structural and functional diversity linked to agricultural intensification and land-use change.

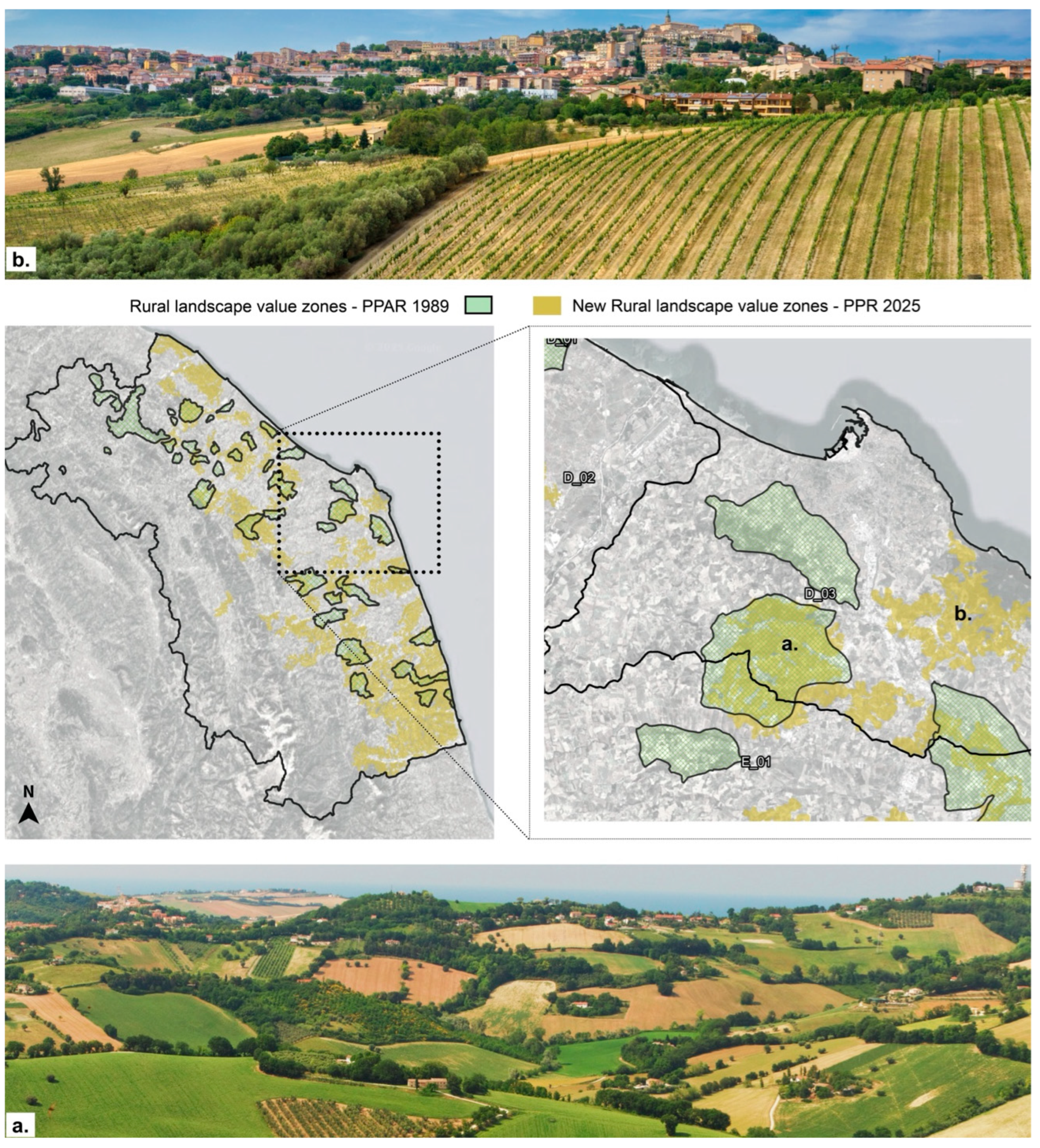

The overlay analysis between the spatial layer representing the

Historic Agrarian Landscape of Identity Value [

12] and the newly mapped high-value areas indicates an underestimation of approximately 10% of the historical rural heritage recognized by the previous plan, as well as limited spatial correspondence with areas of particular relevance for the traditional agrarian landscape (

Figure 9).

Moreover, the mismatch between landscape units and provincial administrative boundaries results in a fragmented regulatory and governance framework, generating limitations in the effective management of the rural landscape at the regional scale. A similar pattern emerges from the comparison with the geometries of the 20 regional landscape areas, designed according to the main geological, geomorphological, and hydrographic features (such as watercourses, valley systems, and slope patterns). In both cases, the analysis reveals that the absence of an intermediate administrative level constrains the coordination of local landscape management and the development of context-specific policies aimed at enhancing the multifunctionality and attractiveness of the rural territory.

From a quantitative perspective, the comparison between the areas of the newly delineated landscape value zones (km²) and those identified in 1989 reveals a notable percentage increase in the historic rural landscapes of southern Marche, particularly within the provinces of Fermo and Ascoli Piceno. Specifically, the area F_03 (Ascoli Piceno) recorded a 44% increase, while E_03 (Dorsale di Cingoli e Alta Collina di S. Ginesio) expanded by 24%. These results confirm that the region’s strong agricultural identity, reinforced by deep-rooted local traditions and a community-based rural culture, has played a decisive role in preserving the characteristic features and morphology of the traditional mezzadria landscape, thereby maintaining continuity in agricultural land use over time. Similarly, a 21% increase was observed in the landscapes of Macerata and Ancona, particularly in area D_02 (Jesi e la Vallesina), indicating a comparable persistence of traditional agricultural practices and territorial resilience.

Conversely, in the northern part of the region, particularly in the Pesaro area, a general decrease was observed in rural landscapes of identity value, with reductions of –26% in area A_02 (Urbinate e Alta Valle del Metauro) and –15% in area B_02 (Fanese e Valle del Metauro). These findings indicate a distinct landscape structure compared to the southern Marche: broader and more regular hill systems prevail, characterized by extensive crop cultivation and a less fragmented settlement pattern, in contrast to the mosaic of mixed crops and scattered settlements typical of the southern territories. In the central part of the region, a moderate decline was also recorded, with decreases of –14% in area D_03 (Paesaggio di Ancona) and –12% in E_01 (Loreto–Recanati e Val Musone,

Table 5).

Concerning the distribution of traditional mezzadria crops, such as vineyards and olive groves, the highest concentrations were recorded in areas F_03 (Ascoli Piceno e la Città Lineare della Valle del Tronto) and F_02 (Valle dell’Aso), with respective surface areas of approximately 6,706 ha and 3,811 ha, accounting for 17% and 13% of the total area. However, the relative incidence of these crops is higher in the northern historical–traditional landscapes (Urbino, Cagli) than in the southern ones (Fermo, Ascoli), where the overall landscape value remains more significant (

Table 6). This finding confirms that, beyond the mere extent of land occupied by traditional arboreal crops, it is the configuration of the settlement landscape that plays the most significant role in shaping the landscape value matrix. The complex network of rural farmhouses, the widespread presence of agrarian features, and the system of country roads shaped by the mezzadria model together define the complex hilly morphology and represent the structural invariants that most strongly characterize the traditional landscape of the Marche Region (

Figure 10a, b).

4. Discussion

Through the regional-scale case study of the Marche Region, this research advances an innovative methodological framework for landscape planning, centred on the definition of new ecological and landscape performance goals. These purposes emerge from an integrated interpretation of the historical, cultural, and ecological components embedded in rural areas, as well as from the relationships that connect them [

36].

By integrating the predominantly qualitative and perceptual approaches, this study introduces a performance-based paradigm into landscape planning [

37], that shift enables the subdivision of rural territories into value-based thresholds, defining distinct areas for the implementation of differentiated and context-specific management strategies. Performance analyses developed within an ecosystem-based framework thus become both disciplinary and strategic tools, integrated within the cartographic system. They support ex-ante assessments of landscape quality and ex-post evaluations of transformation compatibility, providing a dynamic foundation for adaptive and evidence-based landscape governance.

From this perspective, the proposed methodology has the potential to evolve into an interactive decision-support system for municipal and regional planning. It can enhance the performance of landscape management and valorization through three main dimensions: a) the progressive implementation and improvement of knowledge frameworks, ensuring more detailed and continuously updated territorial information [

38,

39];

b) the strengthening of regulatory coherence and effectiveness across planning levels;

c) the support of new policy frameworks that promote nature-based actions and climate-adaptive agricultural practices, both essential for the long-term conservation and sustainability of traditional and identity-based rural landscapes (

Table 7).

The adoption of sustainable and climate-smart agricultural practices serves not only as a means of mitigating risk and supporting ecological transition but also as a driver for enhancing the multifunctionality of landscapes and local production systems. These practices reinforce the attractiveness of rural areas, particularly through the promotion of ecotourism [

40].

Within this perspective, the landscape can be conceptualized as a distinctive territorial brand, capable of generating added value and supporting high-quality, identity-based agricultural products closely linked to the history and traditions of local contexts.

Accordingly, this study advocates for the adoption of an operational framework designed to foster synergy and alignment between rural development policies and landscape planning: despite the decentralized management of the Rural Development Plans (as key implementation tools of the Common Agricultural Policy, CAP) has facilitated the adaptation of interventions to local contexts by regional authorities, it has also limited the development of fully integrated policies for landscape enhancement.

Developing more flexible and adaptive planning tools, based on performance-oriented rather than merely quantitative–prescriptive principles, represents a crucial step toward strengthening networks and fostering synergies among beneficiaries, such as farms, consortia, and associations, and public institutions [

41]. Such an approach would enable the consolidation of a shared vision that promotes the Marche landscape as both an identity-based and competitive territorial asset.

Regarding the limitations of this study, it should be emphasized that the cartographic analyses developed are inherently dependent on the availability, resolution, and quality of spatial databases and territorial datasets, which may differ substantially across regions. Consequently, while the proposed methodology is replicable in other contexts, its effective application requires adaptation to local knowledge frameworks and integration with existing planning instruments, including their specific strategic and regulatory settings.

Another limitation concerns the operational applicability of the model by municipal administrations in the preparation of the new General Urban Plans (PUGs), in accordance with Regional Law No. 19/2023.

Effective implementation requires the availability of open-access databases and integrated information systems, conditions that are not yet consistently guaranteed within local technical offices. Furthermore, the selection of high-value landscape areas was based on simplified analytical models, which necessarily abstract from the full complexity of real-world conditions and, to some extent, rely on expert evaluation (e.g., value assignment, threshold definition, and class subdivision). Although these choices were supported by robust analytical procedures designed to ensure the consistent use of spatial models, they nonetheless represent a potential source of partial bias.

Finally, the temporal dimension and the capacity to update and refine databases play a crucial role in maintaining interpretative coherence with ongoing territorial dynamics. This underscores the importance of developing an open, dynamic, and adaptive framework, capable of evolving in parallel with the transformations of local contexts and ensuring the long-term relevance of planning instruments.

5. Conclusions

This paper has demonstrated how integrating Cultural Ecosystem Services (CES) into landscape planning can enhance both the conservation and valorization of rural historical landscapes [

42]. Building on the European Landscape Convention and the recent Nature Restoration Law, the study advocates a shift from prescriptive planning approaches toward more adaptive, ecosystem-based, and performance-oriented models.

The case study of the Marche Region, historically shaped by the mezzadria (sharecropping) system, served as an empirical setting for an innovative methodology grounded in georeferenced and ecosystem-based indicators. This approach enabled the identification of new high-value landscape areas, providing a more accurate representation of the region’s cultural identity while establishing performance thresholds to support differentiated management strategies.

The findings highlight the resilience and cultural integrity of mid to high-hill landscapes, alongside the increasing vulnerability of lowland and mid-hill areas affected by the gradual erosion of structural and functional diversity. Comparison with the previous Regional Landscape Plan [

12] revealed both the expansion and underestimation of valuable rural heritage areas, underscoring the need for updated and coherent territorial knowledge frameworks.

Although the methodology presents limitations related to data availability, model simplification, and the need for continuous updating, it has proven to be an effective, replicable, and policy-relevant tool. Its integration can strengthen the alignment between landscape planning, rural development strategies, and climate-smart agricultural practices, while promoting the landscape as a distinctive territorial asset and identity brand.

Overall, the study advances a paradigm shift toward dynamic and performance-based landscape planning, offering transferable insights for Mediterranean regions where agriculture, culture, and identity remain deeply interconnected.

Funding

This research was funded under the Implementation Agreement for Scientific Collaboration (pursuant to Article 15 of Law 241/1990) between the Marche Region and the universities of the Marche region — the University of Camerino (School of Architecture and Design), the Polytechnic University of Marche (Departments of SIMAU, D3A, DICEA, and DIMA), and the University of Macerata. The agreement, signed in October 2024 following Regional Government Resolution No. 1353/2024, aims to foster joint activities in the fields of spatial and landscape planning and to provide guidelines, orientations, and methodological tools for the elaboration of the Regional Landscape Plan (PPR), the Regional Spatial Plan (PTR), and the establishment of Regional Observatories for Landscape Quality and Land Consumption. The work was developed in the context of the implementation of Regional Law No. 19 of 30 November 2023, “Planning Regulations for Territorial Governance”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The row data used in this study were sourced from regional databases provided by the Marche Region and open platform, as indicated in the article. Processed data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was carried out within the framework of the technical and scientific support activities provided by the research group of UNIVPM, Dept. of Science and Engineering of Matter, Environment and Urban Planning (SIMAU) & Dept. of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences (D3A). The author wishes to express sincere gratitude to all members of the interdisciplinary working group for their valuable collaboration, constructive discussions, and shared commitment throughout the research process. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions involved.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CES |

Cultural Ecosystem Services |

| ELC |

European Landscape Convention |

| PPR |

New Regional Landscape Plan (Piano Paesaggistico Regionale) |

| PUGs |

General Urban Plans (Piano Urbanistico Generale) |

| SWF |

Small woody features |

| CAP |

Common Agricultural Policy |

References

- M. Déjeant-Pons, “The European Landscape Convention,” Landsc Res, vol. 31, pp. 363–384, Oct. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe, “European Landscape Convention and Explanatory Report Document by the Secretary General established by the General Directorate of Education. Culture, Sport dnd Youth, and Environment,” Council of Europe, vol. <http, no. 176, p. jiconventions,coe.i, 2000.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Program), Ecosystems and human well-being : synthesis. Island Press, 2005.

- E. C. D.-G. for Environment, Nature restoration law – For people, climate, and planet. Publications Office of the European Union, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Nevzati, M. Veldi, J. Storie, and M. Külvik, “Leveraging Ecosystem Services and Well-Being in Urban Landscape Planning for Nature Conservation: A Case Study of Peri-Urban Dynamics,” Conservation, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1–22, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, S. Ronchi, and S. Salata, “Managing Multiple Ecosystem Services for Landscape Conservation: A Green Infrastructure in Lombardy Region,” Procedia Eng, vol. 161, pp. 2297–2303, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Kendig, Performance zoning. Chicago, Illinois: APA Planners press, American Planning Association, 1980. Accessed: Feb. 11, 2025. [Online]. Available: ISBN 0-918286-18-2.

- C. Cortinovis and D. Geneletti, “A performance-based planning approach integrating supply and demand of urban ecosystem services,” Landsc Urban Plan, vol. 201, p. 103842, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Tengberg, S. Fredholm, I. Eliasson, I. Knez, K. Saltzman, and O. Wetterberg, “Cultural ecosystem services provided by landscapes: Assessment of heritage values and identity,” Ecosyst Serv, vol. 2, pp. 14–26, Dec. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Petti and M. Ottaviano, “Identification of Agricultural Areas to Restore Through Nature-Based Solutions (NbS),” Land (Basel), vol. 13, no. 11, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), “Words into Action: Nature-based solutions for disaster risk reduction,” 2021. Accessed: Oct. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.undrr.org/words-action-nature-based-solutions-disaster-risk-reduction.

- Marche Region, “PPAR, Piano Paesistico Ambientale Regionale.” [Online]. Available: https://www.regione.marche.it/Regione-Utile/Paesaggio-Territorio-Urbanistica-Genio-Civile/Paesaggio.

- Legislative Decree n. 42, “Code of the Cultural and Landscape Heritage,” Jan. 2004.

- M. Agnoletti, Ed., The conservation of cultural landscapes, 1st ed. Wallingford and New York.: CAB International, 2006.

- E. Sereni, Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano. Roma, Bari: Laterza, 1974.

- S. Anselmi, Storia dell’agricoltura italiana in età contemporanea, vol. II. Venezia, 1990.

- M. Agnoletti, “Rural landscape, nature conservation and culture: Some notes on research trends and management approaches from a (southern) European perspective,” Landsc Urban Plan, vol. 126, pp. 66–73, 2014. [CrossRef]

- European Union, “Copernicus Land Monitoring Service ,” European Environment Agency (EEA).

- T. Plieninger et al., “The role of cultural ecosystem services in landscape management and planning,” Curr Opin Environ Sustain, vol. 14, pp. 28–33, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Pantaloni, G. Marinelli, R. Santilocchi, and A. Minelli, “Sustainable Management Practices for Urban Green Spaces to Support Green Infrastructure : An Italian Case Study,” Sustainability, no. 14, 4243, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Agnoletti, Ed., Paesaggi Rurali Storici. Per un Catalogo Nazionale. Roma, Bari: Editori Laterza, 2010.

- R. Knight and R. Therivel, “Landscape and visual,” in Methods of Environmental and Social Impact Assessment, 4th ed., P. Morris, R. Therivel, R. Therivel, and G. Wood, Eds., Routledge, 2017.

- M. Moroni, “La mezzadria marchigiana in una prospettiva storica,” in Le Marche nella mezzadria Un grande futuro dietro le spalle, F. Adornato and A. Cegna, Eds., Macerata: Quodlibet Studio, 2013, pp. 13–26.

- F. Renaud, K. Sudmeier-Rieux, and M. Estrella, The Role of Ecosystems in Disaster Risk Reduction. 2013.

- R. Costanza et al., “The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital,” Nature, vol. 387, no. 6630, pp. 253–260, 1997. [CrossRef]

- C. Albert, C. Galler, J. Hermes, F. Neuendorf, C. Von Haaren, and A. Lovett, “Applying ecosystem services indicators in landscape planning and management: The ES-in-Planning framework,” Ecol Indic, vol. 61, pp. 100–113, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- V. Žlender, “Assessing cultural ecosystem service potential for green infrastructure planning in a peri-urban landscape: An expert-based matrix approach,” Urbani Izziv, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 168–183, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. García-Mayor and A. Nolasco-Cirugeda, “New Approach to Landscape-Based Spatial Planning Using Meaningful Geolocated Digital Traces,” Land (Basel), vol. 12, no. 5, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Liquete, N. Cid, D. Lanzanova, B. Grizzetti, and A. Reynaud, “Perspectives on the link between ecosystem services and biodiversity: The assessment of the nursery function,” Ecol Indic, vol. 63, pp. 249–257, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Haines-Young and M. Potschin, “CICES V5. 1. Guidance on the Application of the Revised Structure,” Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES), no. January, p. 53, 2018, [Online]. Available: https://cices.eu/resources/.

- L. Fraucqueur et al., A new Copernicus high resolution layer at pan-European scale: the small woody features. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Melley M.E., “Edifici rurali e paesaggio: il trattamento delle aree esterne partinenziali come fattore importante per un corretto inserimento ambientale,” in Edilizia rurale e territorio. Analisi, metodi, progetti, Mambriani A. and Zappavigna P., Eds., Firenze: Mattioli, 2005, pp. 183–188.

- Papallo O., Bagnaia R., Bianco P.M., and Ceralli D, “Carta della Natura della Regione Marche: Carta degli habitat alla scala 1:25.000,” ISPRA. Accessed: Jun. 16, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://sinacloud.isprambiente.it/portal/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=885b933233e341808d7f629526aa32f6.

- M. Moroni, “Trasformazioni del paesaggio e crisi ambientali nella storia delle Marche.,” Proposte e ricerche. Economia e società nella storia dell’Italia centrale, vol. 68, 2012, [Online]. Available: www.proposteericerche.it.

- Valeriani, “Memorie relative all’agricoltura nel Dipartimento del Tronto,” in Annali di Agricoltura del regno d’Italia, vol. XIII, 1812, pp. 59–88.

- H. Schaich, C. Bieling, and T. Plieninger, “Linking Ecosystem Services with Cultural Landscape Research,” GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, vol. 19, pp. 269–277, Dec. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, S. Ronchi, V. Di Martino, and G. Pristeri, “A Multi-Scalar Green Infrastructure Project for the Landscape Enhancement and Regional Regeneration of Media and Alta Valtellina,” 2023, pp. 69–82. [CrossRef]

- L. Gardossi, A. Tomao, M. A. M. Choudhury, E. Marcheggiani, and M. Sigura, “Semi-Automatic Extraction of Hedgerows from High-Resolution Satellite Imagery,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 17, no. 9, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- Patriarca et al., “Wide-Scale Identification of Small Woody Features of Landscape from Remote Sensing,” Land (Basel), vol. 13, no. 8, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. T. Lovell and D. M. Johnston, “Creating multifunctional landscapes: How can the field of ecology inform the design of the landscape?,” Front Ecol Environ, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 212–220, May 2009. [CrossRef]

- P. Picchi, S. Verzandvoort, D. Geneletti, K. Hendriks, and S. Stremke, “Deploying ecosystem services to develop sustainable energy landscapes: a case study from the Netherlands,” Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 422–437, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Babí Almenar, B. Rugani, D. Geneletti, and T. Brewer, “Integration of ecosystem services into a conceptual spatial planning framework based on a landscape ecology perspective,” Landsc Ecol, vol. 33, no. 12, pp. 2047–2059, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Geographic location of the Marche Region (case study area), Italy.

Figure 1.

Geographic location of the Marche Region (case study area), Italy.

Figure 2.

Historical representations of the mezzadria landscape in the Marche Region.

Figure 2.

Historical representations of the mezzadria landscape in the Marche Region.

Figure 3.

Georeferenced spatial layers employed as input data for the development of the landscape value map.

Figure 3.

Georeferenced spatial layers employed as input data for the development of the landscape value map.

Figure 4.

Minor vegetational elements associated with drainage ditch management. Continuous belts of riparian vegetation, hedgerows, and small shrubs ensure the maintenance of multiple ecosystem functions and services. They contribute to the stabilization of slopes and the hydrogeological regulation of cultivated fields, reducing the risk of erosion, soil loss, and landslides. These elements are also essential for maintaining ecological connectivity and supporting biodiversity. Historically, the maintenance of hedgerows played a key role in providing rural households with firewood and supplementary food resources, thereby reinforcing the multifunctional character of traditional agricultural landscapes.

Figure 4.

Minor vegetational elements associated with drainage ditch management. Continuous belts of riparian vegetation, hedgerows, and small shrubs ensure the maintenance of multiple ecosystem functions and services. They contribute to the stabilization of slopes and the hydrogeological regulation of cultivated fields, reducing the risk of erosion, soil loss, and landslides. These elements are also essential for maintaining ecological connectivity and supporting biodiversity. Historically, the maintenance of hedgerows played a key role in providing rural households with firewood and supplementary food resources, thereby reinforcing the multifunctional character of traditional agricultural landscapes.

Figure 5.

Traditional Marche farmhouses: typological features, architectural components, and integration within the hilly landscape. Bottom right: mid-slope farmhouse in Cesano di Senigallia. Top right: hilltop farmhouse with internal staircase in Castelvecchio di Monteporzio, Pesaro.

Figure 5.

Traditional Marche farmhouses: typological features, architectural components, and integration within the hilly landscape. Bottom right: mid-slope farmhouse in Cesano di Senigallia. Top right: hilltop farmhouse with internal staircase in Castelvecchio di Monteporzio, Pesaro.

Figure 6.

Map detail from the

Gregorian Cadastre (1835) (left;

https://www.provincia.ancona.it/Servizi-online/Web-Gis/Catasto-Gregoriano-1) and

GAI aerial survey (1954, rigth). The overlapping between the two maps (center) highlights the persistence of the sharecropping landscape structure established by 1835, including the country road network and a widespread system of farmhouses organizing the rural territory. Linear vegetative elements defining the hydrographic and field systems are also clearly visible in the 1954 imagery.

Figure 6.

Map detail from the

Gregorian Cadastre (1835) (left;

https://www.provincia.ancona.it/Servizi-online/Web-Gis/Catasto-Gregoriano-1) and

GAI aerial survey (1954, rigth). The overlapping between the two maps (center) highlights the persistence of the sharecropping landscape structure established by 1835, including the country road network and a widespread system of farmhouses organizing the rural territory. Linear vegetative elements defining the hydrographic and field systems are also clearly visible in the 1954 imagery.

Figure 7.

The Marche rural landscape characterized by alternating patterns of vineyards (left) and olive groves (right), forming the distinctive mosaic structure of the region’s traditional agrarian landscape.

Figure 7.

The Marche rural landscape characterized by alternating patterns of vineyards (left) and olive groves (right), forming the distinctive mosaic structure of the region’s traditional agrarian landscape.

Figure 8.

a) Landscape value map based on the defined value gradient. b) Gelocalization of areas with high ecosystem value within the regional landscape.

Figure 8.

a) Landscape value map based on the defined value gradient. b) Gelocalization of areas with high ecosystem value within the regional landscape.

Figure 9.

Top: Offagna Hills, Ancona Province (a). Center: Spatial correspondence between high-value landscape areas and the Historic Agrarian Landscape of Identity Value spatial layer (PPAR, 1989). The overlay analysis highlights a partial mismatch, with an underestimation of approximately 10% of the historically recognized rural heritage, mainly concentrated in the mid- and upper-hill zones of the Marche Region. Bottom: View of Camerano, Ancona province, Marche, Italy and vineyards (b).

Figure 9.

Top: Offagna Hills, Ancona Province (a). Center: Spatial correspondence between high-value landscape areas and the Historic Agrarian Landscape of Identity Value spatial layer (PPAR, 1989). The overlay analysis highlights a partial mismatch, with an underestimation of approximately 10% of the historically recognized rural heritage, mainly concentrated in the mid- and upper-hill zones of the Marche Region. Bottom: View of Camerano, Ancona province, Marche, Italy and vineyards (b).

Figure 10.

Rural landscapes of the Marche Region: a) Fano–Mondavio road, Pesaro and Urbino Province (spring), characterized by extensive arable land and industrial crops (tobacco, sugar beet, maize) with scattered manor farms; b) Ripatransone countryside, Ascoli Piceno Province (summer), showing the denser rural fabric typical of southern Marche landscape.

Figure 10.

Rural landscapes of the Marche Region: a) Fano–Mondavio road, Pesaro and Urbino Province (spring), characterized by extensive arable land and industrial crops (tobacco, sugar beet, maize) with scattered manor farms; b) Ripatransone countryside, Ascoli Piceno Province (summer), showing the denser rural fabric typical of southern Marche landscape.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of the Marche Region’s mezzadria landscape.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of the Marche Region’s mezzadria landscape.

| Landscape features |

Description |

| Hills and Fields |

The landscape is dominated by rolling, green hills with a distinct geometry of rectangular and square fields. |

| Vegetation |

Lines of trees, such as oak trees, and cane ditches, as well as vineyards, divide the fields, adding to the structured appearance. |

| Patchwork Effect |

The mixed cultivation of crops like wheat, sunflowers, and legumes creates a vibrant patchwork, making the land appear like a well-tended garden. |

| Rural Architecture |

The landscape is dotted with farmhouses and small rural settlements that are integrated into the topography and often serve multiple functions for agricultural work and family life. |

| Historical Context |

The mezzadria system, which required tenant farmers to share their harvest with landowners, fostered intensive and meticulous cultivation. |

| Anthropized Landscape |

The result of centuries of human intervention, the landscape is a highly organized and cultivated environment, far from a purely wild state. |

Table 2.

Input data selected for defining the value matrix of the historical-identity rural landscape.

Table 2.

Input data selected for defining the value matrix of the historical-identity rural landscape.

Table 3.

Landscape matrix - hillside sharecropping-based landscape structure.

Table 3.

Landscape matrix - hillside sharecropping-based landscape structure.

| Spatial level selected * |

Indicators (1-5) |

weight (%) |

ES associated (Biotic/Biophysical) |

Small woody features (SWF)

|

3 |

60 |

Regulation & Maintenance

- -

Land stability - -

Hazard mitigation (wind protection, Buffering and attenuation of mass movement - landslide) - -

Hydrological cycle and water flow regulation - -

Erosion control (Control of wind e/o water erosion rates) - -

Lifecycle maintenance, habitat and gene pool protection - -

Biodiversity / Habitat creation and maintenance [ 29]

Provisioning

- -

Biomass (nutritional purpose) / Food production - -

Biomass (source of energy)

Cultural

- -

Spiritual, symbolic and other cultural interactions with natural environment - -

Landscape esthetic

|

| Farmhouses ‘case coloniche’ |

5 |

100 |

| Countryroads |

4 |

80 |

| Vineyards |

5 |

100 |

| Olive groves |

5 |

100 |

| Mixed tree crops arable land ‘seminativo arborato’

|

2 |

40 |

Table 4.

Correspondence between the three levels of transformability derived from the synthesis of value ranges into three thresholds, and the related differentiated management strategies. High-value landscape areas correspond to Level 3, characterized by a low degree of transformability.

Table 5.

Comparison between the 1989 and current spatial layers of traditional agricultural landscapes, classified by Landscape Units (a) and Province (b).

Table 5.

Comparison between the 1989 and current spatial layers of traditional agricultural landscapes, classified by Landscape Units (a) and Province (b).

| Abbreviation |

(a) Provinces

(name) |

Area

(km2) |

Rural landscape value zones year 1989

(km2) |

New rural landscape value zones

year 2025

(km2) |

Difference

(%) |

| PU |

Pesaro Urbino |

2,510.82 |

239.03 |

234.49 |

-0.2 |

| AN |

Ancona |

1,963.21 |

278.10 |

278.10 |

6 |

| MC |

Macerata |

2,779.31 |

128.55 |

431.20 |

15 |

| FM |

Fermo |

862.75 |

149.32 |

339.29 |

22 |

| AP |

Ascoli Piceno |

1,228.18 |

24.78 |

425.28 |

32 |

| |

Total |

9,344.29 |

819.8 |

1,822.61 |

10 |

| ID (n.) |

(a) Landscape units

(name) |

Area

(km2) |

Rural landscape

value zones

year 1989

(km2) |

New rural landscape value zones

year 2025

(km2) |

Difference

(%) |

| A_01 |

Il Monte Carpegna e le alte Valli del Conca e del Foglia |

370.41 |

138.34 |

/ |

|

| A_02 |

L'Urbinate e l'Alta Valle del Metauro |

520.37 |

137.73 |

1.28 |

- 26 |

| B_01 |

Il Pesarese |

259.70 |

100.85 |

79.42 |

-8 |

| B_02 |

Il Fanese e la Valle del Metauro |

405.19 |

176.96 |

115.08 |

-15 |

| B_03 |

La Valle del Cesano |

238.32 |

59.83 |

56.06 |

-1 |

| C_01 |

Cagli e le Valli del Candigliano ed alto Cesano |

799.49 |

55.46 |

3.14 |

-6 |

| C_02 |

Fabriano e l'Alto Esino |

742.28 |

40.19 |

17.24 |

-3 |

| C_03 |

Camerino e le Alte Valli del Potenza e del Chienti |

610.74 |

- |

5.98 |

0,9 |

| D_01 |

Senigallia e la Valle del Misa |

346.66 |

92.46 |

127.67 |

10 |

| D_02 |

Jesi e la Vallesina |

505.20 |

69.05 |

175.86 |

21 |

| D_03 |

Il Paesaggio di Ancona |

303.87 |

98.88 |

55.96 |

-14 |

| E_01 |

Loreto-Recanati e la Val Musone |

343.00 |

85.10 |

40.84 |

-12 |

| E_02 |

Le Colline del Maceratese |

745.09 |

125.88 |

256.14 |

17 |

| E_03 |

La Dorsale di Cingoli e l'Alta Collina di S. Ginesio |

444.68 |

- |

106.96 |

24 |

| F_01 |

Fermo e la Vallata del Tenna |

560.83 |

149.32 |

260.08 |

19 |

| F_02 |

La Valle dell'Aso |

275.12 |

98.41 |

219.73 |

44 |

| F_03 |

Ascoli Piceno e la Città Lineare della Valle del Tronto |

378.86 |

24.78 |

262.60 |

62 |

| F_04 |

Il Monte dell'Ascensione e l'Alta

Collina del Piceno

|

399.90 |

28.17 |

23.85 |

-1 |

| G_01 |

I Monti Sibillini |

749.12 |

- |

2.18 |

0,2 |

| G_02 |

I Monti della Laga e l'Alta Valle del Tronto |

320.60 |

- |

12.32 |

4 |

Table 6.

Coverage of vineyard and olive grove areas across the 20 regional Landscape units.

Table 6.

Coverage of vineyard and olive grove areas across the 20 regional Landscape units.

| ID (n.) |

Landscape units

(name) |

Area

(ha) |

(a.)

Vineyard

(ha) |

(b.)

Olive groves

(ha) |

Tree crop

(a.+b.)

(ha) |

Tree

crop/

Total surface

(%) |

Tree

crop/ landscape value zones

(%) |

| A_01 |

Il Monte Carpegna e le alte Valli del Conca e del Foglia |

3,7041 |

53.6 |

24.5 |

78.2 |

0,2 |

/ |

| A_02 |

L'Urbinate e l'Alta Valle del

Metauro |

52,037 |

74.5 |

26.9 |

101.5 |

0,2 |

78,7 |

| B_01 |

Il Pesarese |

25,970 |

437.3 |

741.4 |

1178.7 |

4,5 |

14,8 |

| B_02 |

Il Fanese e la Valle del Metauro |

40,519 |

585.0 |

989.2 |

1574.2 |

3,8 |

13,7 |

| B_03 |

La Valle del Cesano |

23,832 |

317.4 |

160.8 |

478.2 |

2,0 |

8,5 |

| C_01 |

Cagli e le Valli del Candigliano ed alto Cesano |

79,949 |

70.5 |

26.7 |

97.3 |

0,1 |

30,9 |

| C_02 |

Fabriano e l'Alto Esino |

74,228 |

405.6 |

82.8 |

488.5 |

0,6 |

28,3 |

| C_03 |

Camerino e le Alte Valli del Potenza e del Chienti |

61,074 |

121.0 |

144.1 |

265.2 |

0,4 |

44,3 |

| D_01 |

Senigallia e la Valle del Misa |

34,666 |

1118.6 |

666.3 |

1785 |

5,1 |

14,0 |

| D_02 |

Jesi e la Vallesina |

50,520 |

2588.6 |

1037.4 |

3626.1 |

7,1 |

20,6 |

| D_03 |

Il Paesaggio di Ancona |

30,387 |

637.4 |

306.0 |

943.5 |

3,1 |

16,9 |

| E_01 |

Loreto-Recanati e la Val

Musone |

34,300 |

433.1 |

243.8 |

677 |

1,9 |

16,6 |

| E_02 |

Le Colline del Maceratese |

74,509 |

583.3 |

1541.3 |

2124.6 |

2,8 |

8,3 |

| E_03 |

La Dorsale di Cingoli e

l'Alta Collina di S. Ginesio |

44,468 |

352.4 |

769 |

1121.5 |

2,5 |

10,5 |

| F_01 |

Fermo e la Vallata del Tenna |

56,083 |

761.6 |

1167.6 |

1929.3 |

3,4 |

7,4 |

| F_02 |

La Valle dell'Aso |

27,512 |

2442.2 |

1369.6 |

3811.8 |

13,8 |

17,3 |

| F_03 |

Ascoli Piceno e la Città Lineare della Valle del Tronto |

37,886 |

3712.0 |

2994 |

6706.1 |

17,7 |

25,5 |

| F_04 |

Il Monte dell'Ascensione e l'Alta

Collina del Piceno |

39,990 |

357.1 |

330.7 |

687.9 |

1,7 |

28,8 |

| G_01 |

I Monti Sibillini |

74,912 |

7.69 |

159.2 |

166.9 |

0,2 |

76,5 |

| G_02 |

I Monti della Laga e l'Alta

Valle del Tronto |

32,060 |

9.48 |

328.5 |

338 |

1,0 |

27,4 |

Table 7.

Objectives and design strategies to foster climate-resilient agriculture within landscape planning. Action and measures of both categories could be applied distinctively, depending on the level of transformability (1-high, 2-medium low, 3-low).

Table 7.

Objectives and design strategies to foster climate-resilient agriculture within landscape planning. Action and measures of both categories could be applied distinctively, depending on the level of transformability (1-high, 2-medium low, 3-low).

| Category |

Objective |

Level of transformability |

targeted

response measures |

Actions/Measures |

Conservation

agriculture |

Create a biodiverse, resource-conserving and resilient rural landscape |

3 - low

2 - medium-low

|

maintenance/

valorization

rebalancing

|

Climate-resilient crop and variety selection: promote cultivars resistant to drought, extreme temperatures, and other climate-related stresses; Enhancement of soil ecosystem functions: improve water retention capacity, reduce erosion and soil loss risk, and increase soil fertility; Restoration, recovery, and creation of minor agrarian landscape elements: hedgerows, tree rows, field trees, small watercourses, and terraced slopes; Irrigation system efficiency: develop water storage systems (e.g., small hillside reservoirs) to supplement consortium water supplies. |

Agro-technological

Infrastructure |

Enhance climate resilience, energy transition, and economic sustainability |

2 - medium-low

1 - high

|

rebalancing

regeneration

|

- 5.

Active protection systems against abiotic stress: multifunctional nets (hail, wind, shading, rain, insect, photo-selective) to protect crops from extreme weather, pests, and diseases. - 6.

Agrivoltaics systems: integrate renewable energy production into agricultural landscapes. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).