Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Overview

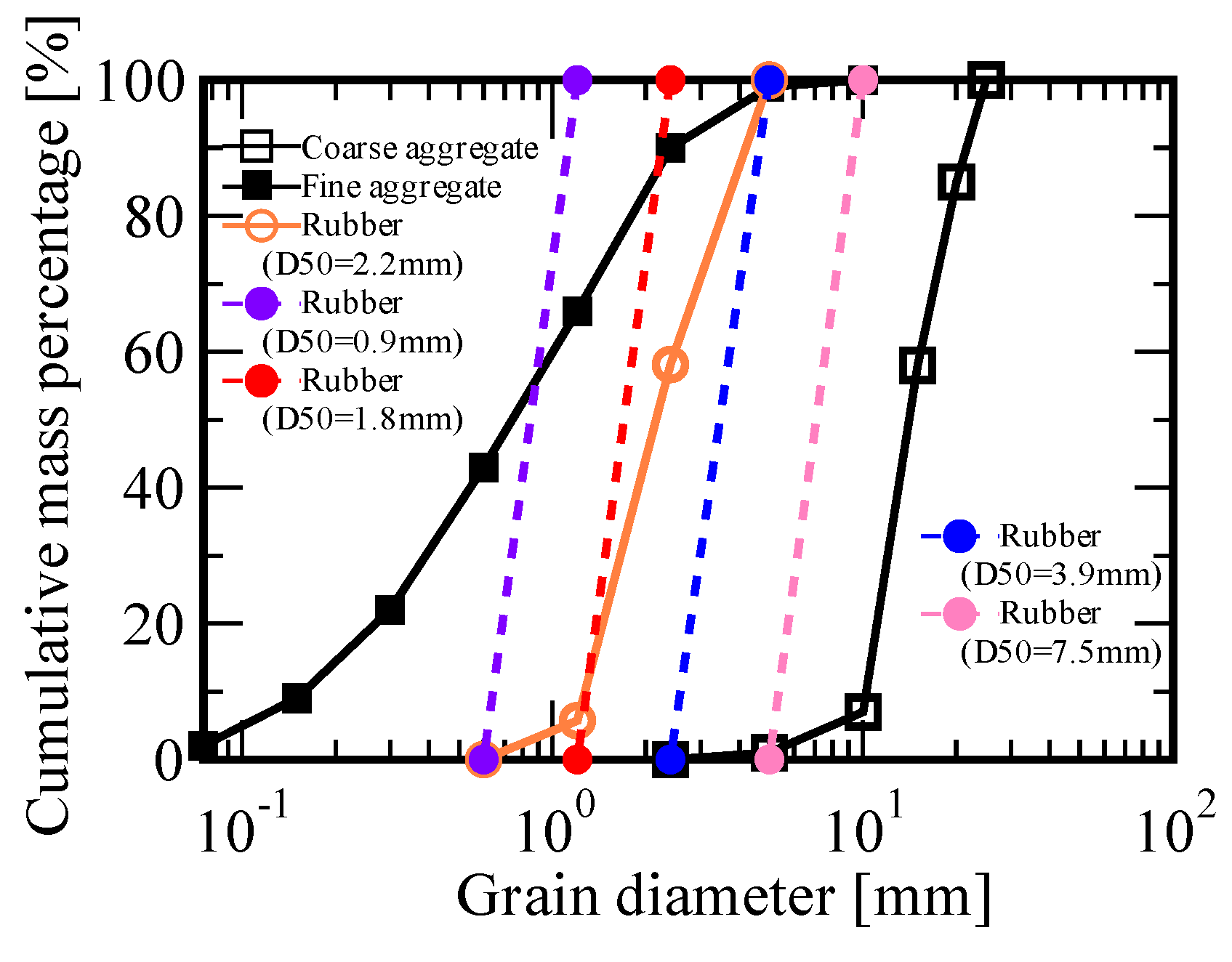

2.1. Experimental Materials and Specimen Preparation

2.2. Experimental Cases

2.3. Measurement Overview

3. Experimental Results

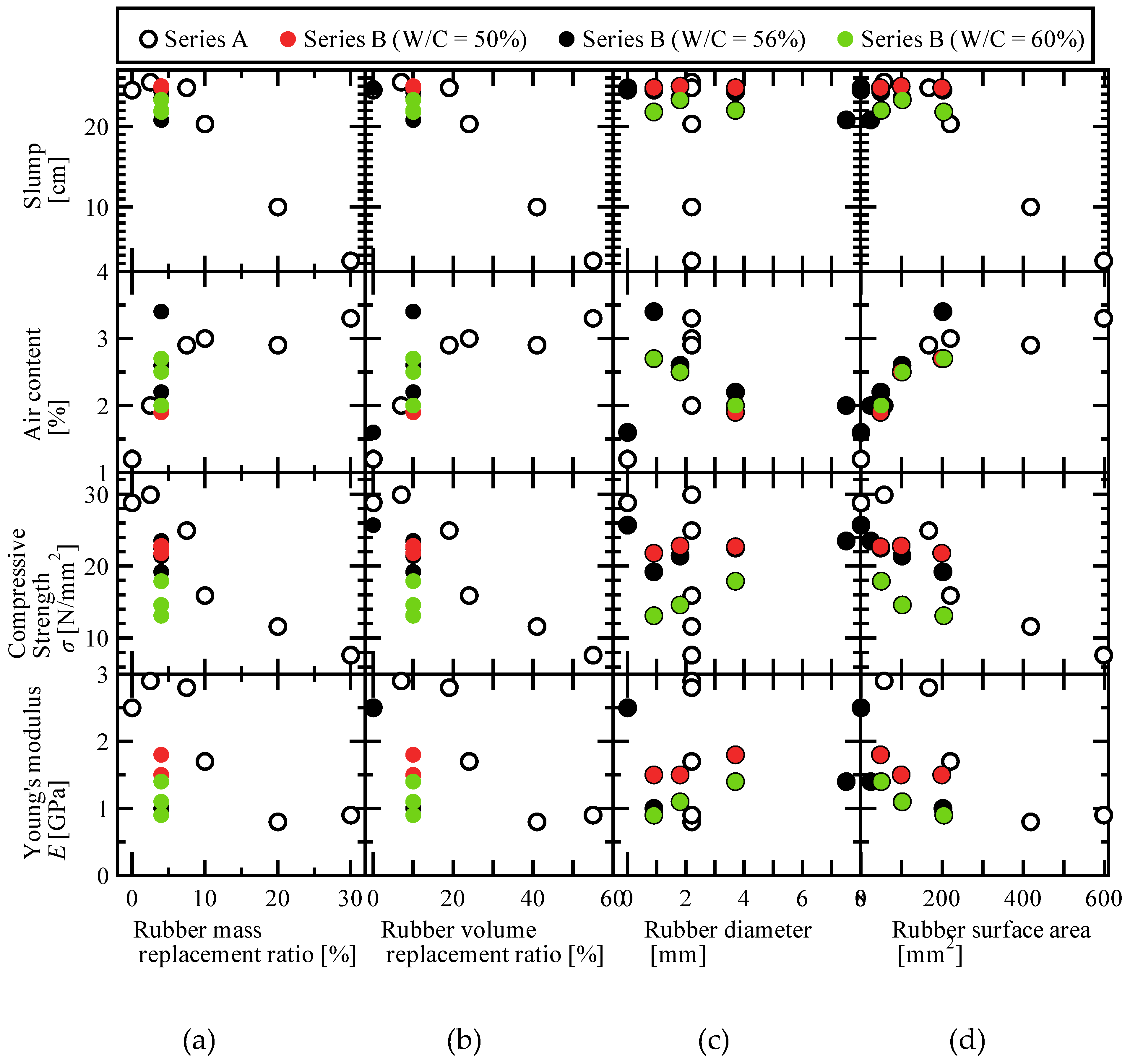

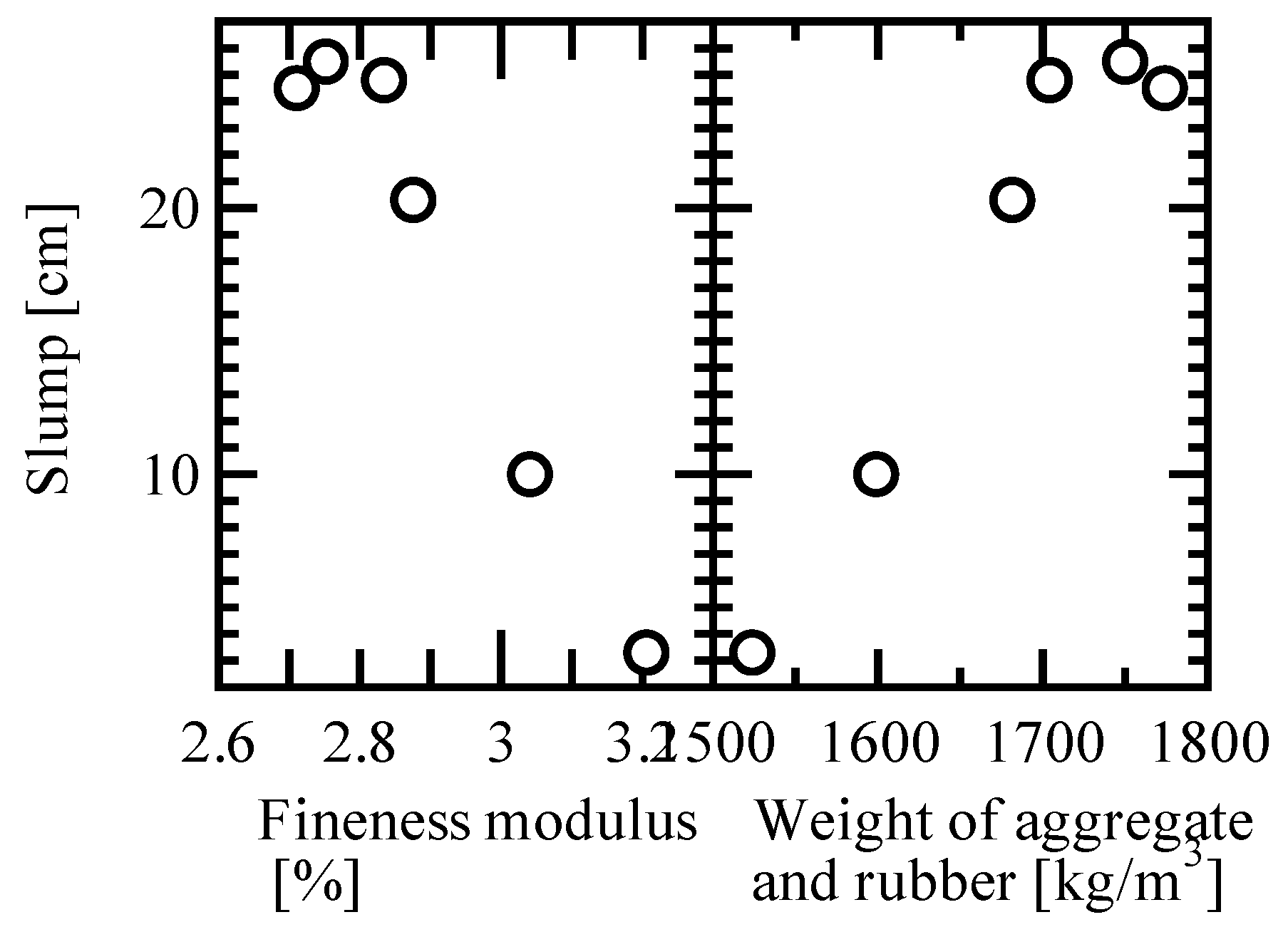

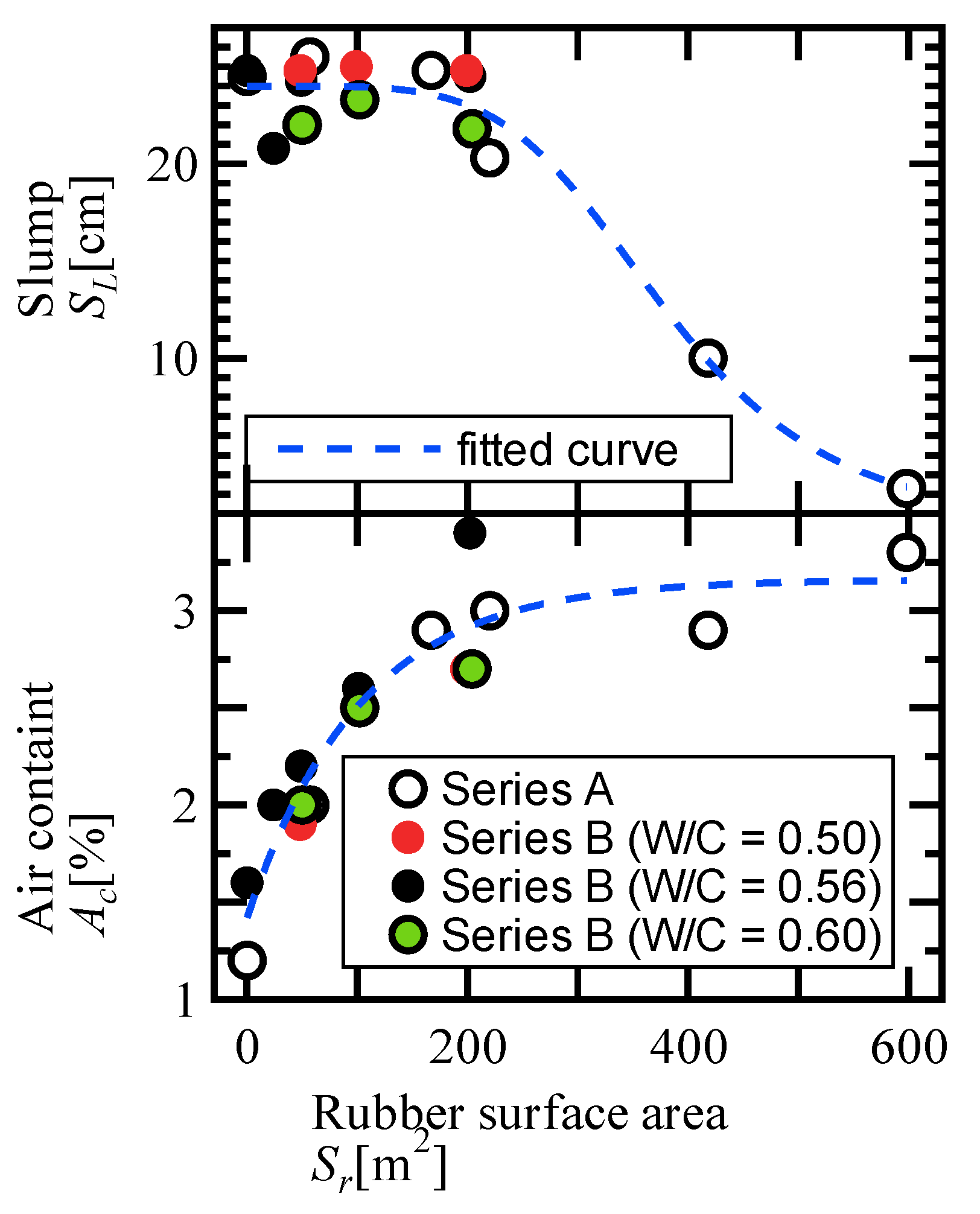

3.1. Slump Test Results

3.2. Air Content Test Results

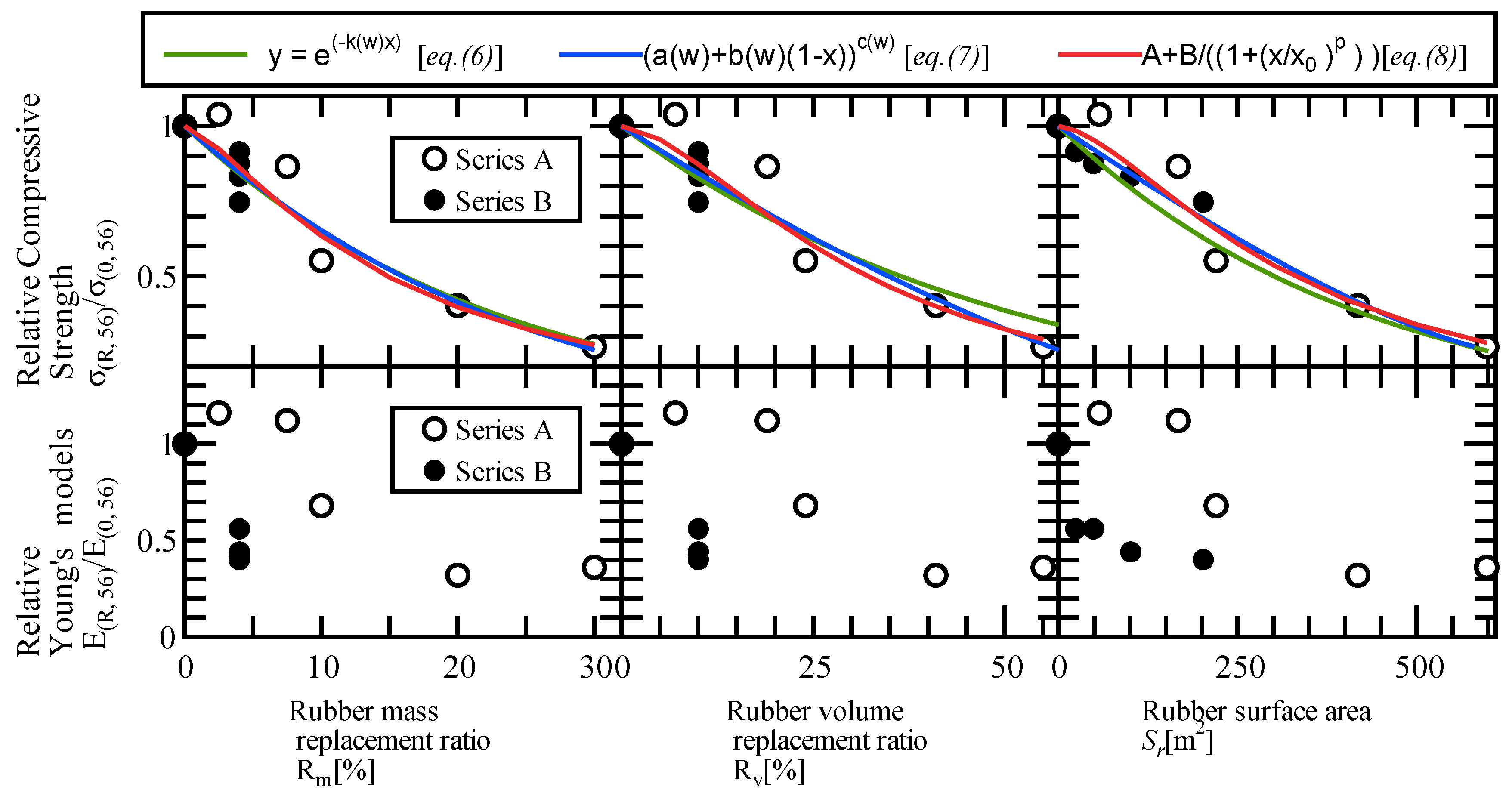

3.3. Compressive-Strength Test Results

4. Proposal of Estimation Equations for RuC Properties

4.1. Estimation Equations for Fresh Concrete Properties (Slump and Air Content)

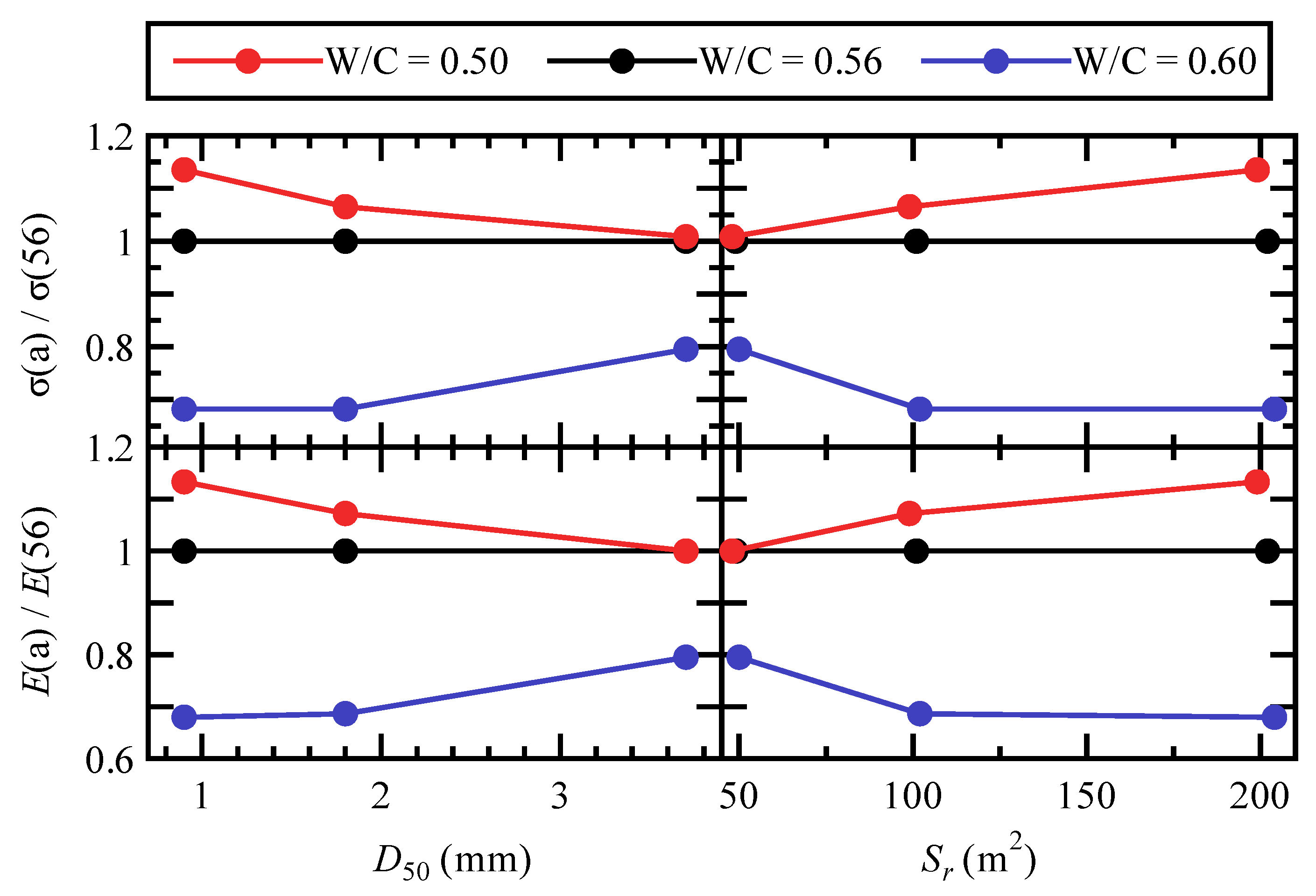

4.2. Proposal of Estimation Equations for Mechanical Properties

4.2.1. Estimation Equations for the Results at W/C = 0.56

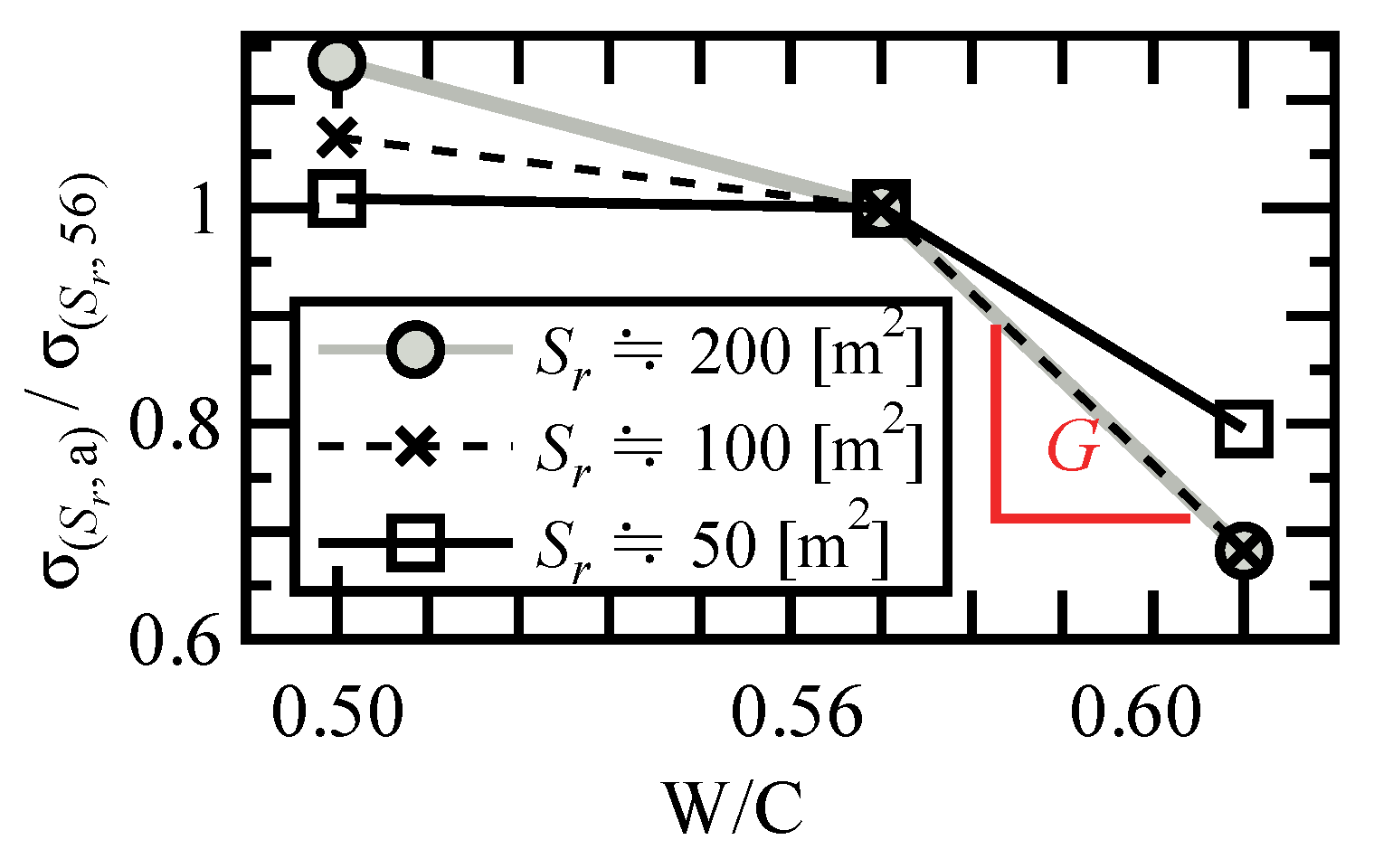

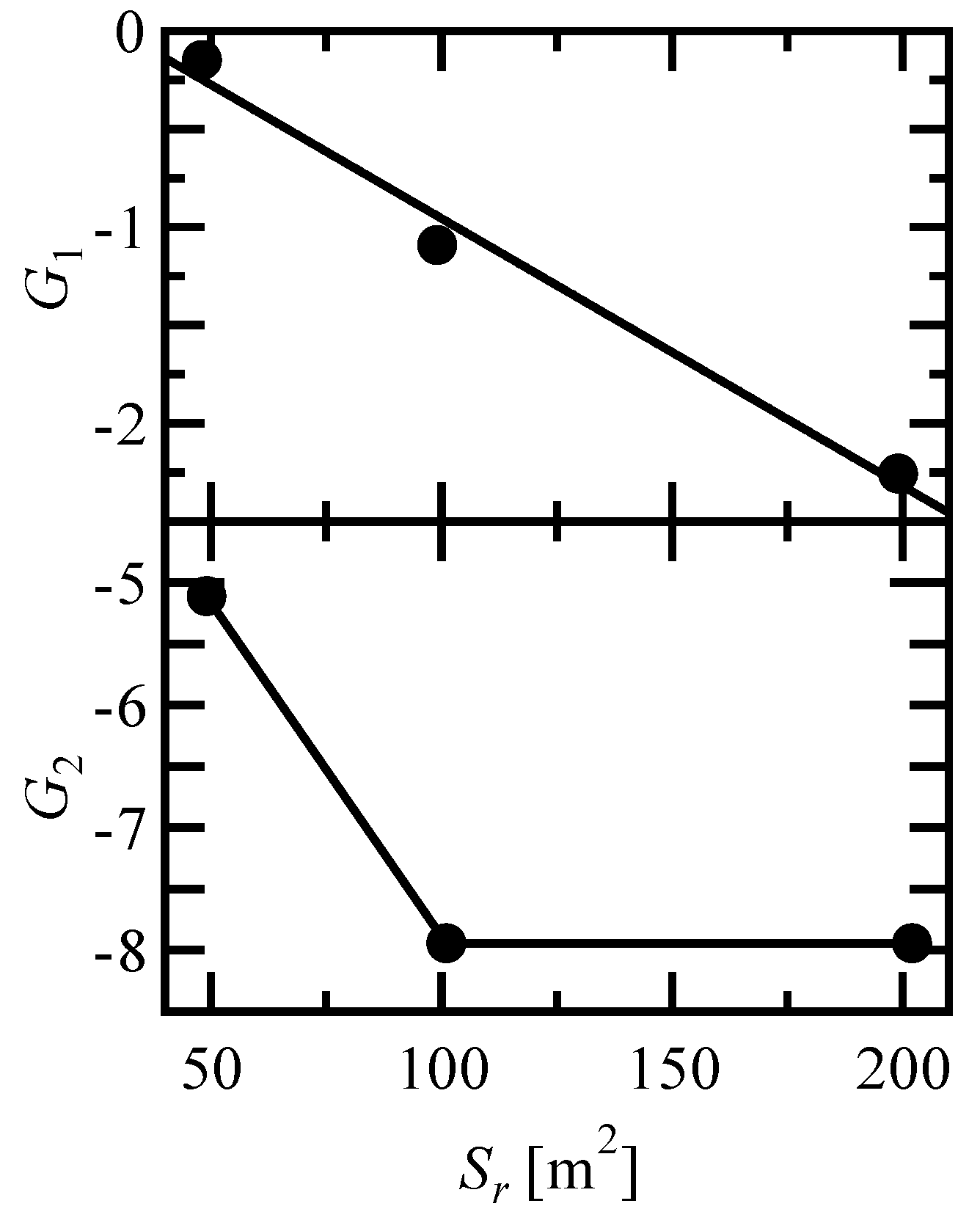

4.2.2. Estimation Equation for Compressive Strength of RuC with Arbitrary W/C and Rubber Content

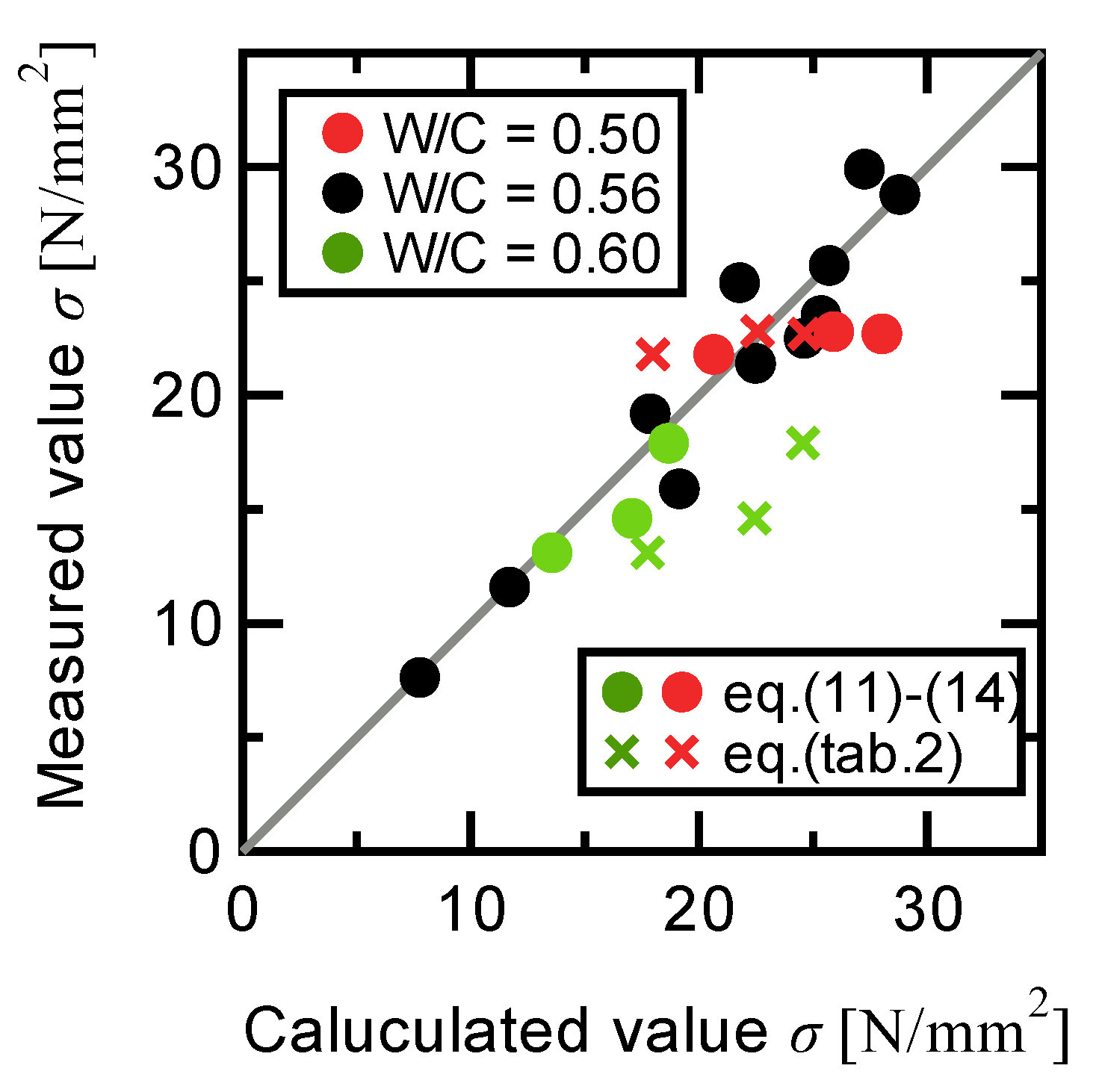

4.2.3. Verification of Estimation Accuracy

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- The slump and air content of RuC are strongly governed by the total surface area of the incorporated rubber, whereas the influence of the W/C ratio is limited. The slump, which is a monotonic quantity with upper and lower bounds, was well approximated by a logistic function, whereas the air content was well captured by a saturating exponential function. This supports the treatment of the total rubber surface area as the primary control variable in the mix design.

- The compressive strength decreased with increasing rubber content; however, the degree of reduction was not uniform and depended on the W/C ratio, amount, and properties of the rubber. Specifically, strength sensitivity to variations in the W/C ratio increased with smaller particle size or larger surface area, and decreased with larger particles or smaller surface areas.

- The logistic function provided a more appropriate mathematical model than conventional exponential or polynomial functions. This is because the experimental results exhibited a distinctly nonlinear reduction in compressive strength: a modest decrease at low and high rubber contents, but a sharp decline in an intermediate transition zone. The logistic function accurately captured this rapid strength reduction, whereas simpler models fail to reproduce it with comparable accuracy.

- The relationship between compressive strength and total rubber surface area at a W/C ratio of 0.56 was defined using a logistic baseline, and a W/C-dependent correction was proposed to account for differences in strength ratios across W/C levels. This two-step model (“symmetric baseline” + “W/C-dependent correction”) enables consistent estimation of the RuC compressive strength for arbitrary conditions (W/C and rubber content).

- By correcting for W/C using the two-step model, the tendency of a simple symmetric model (logistic function) to overestimate relative to the experiments was mitigated, yielding improved agreement. Thus, even for strongly asymmetric material behaviors, such as the RuC compressive strength, appropriately corrected symmetric models can provide accurate and practical predictions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, B.; Wu, H.; Wu, Y.F. Evaluation of carbon footprint of compression cast waste rubber concrete based on LCA approach. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, H.; Chen, Z.; Ding, J.; Deng, H.; Mosallam, A.S. Mechanical properties, durability, and structural applications of rubber concrete: A state-of-the-art-review. Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, D.; Waghe, U.; Ansari, K.; Amran, M.; Gamil, Y.; Alluqmani, A.E.; Thakare, N. Optimization of eco-friendly concrete with recycled coarse aggregates and rubber particles as sustainable industrial byproducts for construction practices. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, T.; Yang, Y.; Cao, H.; Si, N.; Kordestani, H.; Sktani, Z.D.I.; Arab, A.; Zhang, C. Rubberized concrete: Effect of the rubber size and content on static and dynamic behavior. Buildings 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guíñez, F.; Santa María, H.; Araya-Letelier, G.; Lincoleo, J.; Palominos, F. Effect of mix dosage on rubberized concrete mechanical performance: A multivariable prediction model towards design provisions. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, D.K.; Ray, S. An improved understanding of the influence of w/c ratio and interfacial transition zone on fracture mechanisms in concrete. Mag. Concr. Res. 2023, 75, 847–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gao, W.; Zhu, P.; Wu, J.; Liu, H.; Lyu, Q.; Liu, S. Leaching-induced deterioration of shear bonding strength and micro-Vickers hardness of the ITZ modified by micro-SiO2 and nano-SiO2. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregori, A.; Castoro, C.; Venkiteela, G. Predicting the compressive strength of rubberized concrete using artificial intelligence methods. Sustainability 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvonarić, M.; Benšić, M.; Barišić, I.; Dokšanović, T. Prediction models for mechanical properties of cement-bound aggregate with waste rubber. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Du, H.; Li, J.; Yuan, J. Effect of rubber aggregates on early-age mechanical properties and deformation behaviors of cement mortar. Buildings 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddhacosa, N.; Galos, J.; Khatibi, A.; Das, R.; Kandare, E. Effect of tyre-derived rubber particle size on the mechanical properties of rubberised syntactic foam. Cleaner Mater. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japanese Industrial Standards Committee. JIS A 1101:2020 Method of Test for Slump of Concrete; Japanese Standards Association. 2020.

- Japanese Industrial Standards Committee. JIS A 1128: 2020 Method of Test for Air Content of Fresh Concrete; Japanese Standards Association. 2020.

- Japanese Industrial Standards Committee. JIS A 1108: 2020 Method of Test for Compressive Strength of Concrete; Japanese Standards Association. 2018.

- Japanese Industrial Standards Committee. JIS A 1149 Method of Test for Static Modulus of Elasticity of Concrete; Japanese Standards Association, 2010.

- Zheng, W.; Shui, Z.; Xu, Z.; Gao, X.; Gao, K. Impact of coarse aggregate morphology andseparation distance on concrete properties based on visual learning. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Series | Case | Mix Design | Rubber Quantities | Experimental Results | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse Aggregate [kg/m3] |

Fine Aggregate [kg/m3] |

Rubber Quantity [kg/m3] |

W/C [%] |

Mass Replacement Rate [%] |

Volume Replacement Rate [%] |

Rubber Particle Diameter [mm] |

Rubber Surface Area [m2] |

Slump [cm] |

Air content [%] |

Compre-ssive Strength [N/mm2] |

Young’s Modulus [GPa] |

||

| A | GC | 983.0 | 791.0 | 0 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24.5 | 1.2 | 28.8 | 2.5 |

| GS2.5 | 969.7 | 760.8 | 19.5 | 56 | 2.5 | 6.8 | 2.2 | 56.9 | 25.5 | 2.0 | 29.9 | 2.9 | |

| GS7.5 | 944.3 | 702.9 | 57.0 | 56 | 7.5 | 18.5 | 2.2 | 165.9 | 24.8 | 2.9 | 24.9 | 2.8 | |

| GS10 | 932.0 | 675.0 | 75.0 | 56 | 10.0 | 23.8 | 2.2 | 218.4 | 20.3 | 3.0 | 15.9 | 1.7 | |

| GS20 | 886.0 | 570.4 | 142.6 | 56 | 20.0 | 41.2 | 2.2 | 415.3 | 10.0 | 2.9 | 11.6 | 0.8 | |

| GS30 | 844.3 | 475.6 | 203.8 | 56 | 30.0 | 54.6 | 2.2 | 593.7 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 7.6 | 0.9 | |

| B | C | 983.0 | 791 | 0 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24.8 | 1.6 | 25.7 | 2.5 |

| G0.9-56 | 983.0 | 711.8 | 28.2 | 56 | 3.8 | 10.0 | 0.9 | 202.2 | 24.5 | 3.4 | 19.2 | 1.0 | |

| G1.8-56 | 983.0 | 711.8 | 28.2 | 56 | 3.8 | 10.0 | 1.8 | 101.1 | 23.5 | 2.6 | 21.4 | 1.1 | |

| G3.7-56 | 983.0 | 711.8 | 28.2 | 56 | 3.8 | 10.0 | 3.7 | 49.2 | 24.3 | 2.2 | 22.5 | 1.4 | |

| G7.5-56 | 983.0 | 711.8 | 28.2 | 56 | 3.8 | 10.0 | 7.5 | 24.3 | 20.8 | 2.0 | 23.5 | 1.4 | |

| G0.9-50 | 964.0 | 698.0 | 27.7 | 50 | 3.8 | 10.0 | 0.9 | 198.6 | 24.8 | 2.7 | 21.8 | 1.5 | |

| G1.8-50 | 964.0 | 698.0 | 27.7 | 50 | 3.8 | 10.0 | 1.8 | 99.3 | 25.0 | 2.5 | 22.8 | 1.5 | |

| G3.7-50 | 964.0 | 698.0 | 27.7 | 50 | 3.8 | 10.0 | 3.7 | 48.3 | 24.8 | 1.9 | 22.7 | 1.8 | |

| G0.9-60 | 992.0 | 718.0 | 28.5 | 60 | 3.8 | 10.0 | 0.9 | 203.9 | 21.8 | 2.7 | 13.1 | 0.9 | |

| G1.8-60 | 992.0 | 718.0 | 28.5 | 60 | 3.8 | 10.0 | 1.8 | 102.0 | 23.3 | 2.5 | 14.6 | 1.1 | |

| G3.7-60 | 992.0 | 718.0 | 28.5 | 60 | 3.8 | 10.0 | 3.7 | 49.6 | 22.0 | 2.0 | 17.9 | 1.4 | |

| Eq.(6) |

[R2 = 089] |

[R2 = 0.85] |

[R2 = 0.89] |

| Eq.(7) | 0.05+0.95(1−/100)4.3 [R2 = 0.89] |

(1/100) 1.6 [R2 = 0.88] |

0.26+0.74 (1/598) 1.3 [R2 = 0.91] |

| Eq.(8) |

[R2 = 0.93] |

[R2 = 0.93] |

[R2 = 0.95] |

| G Sr [m2] (D50 [mm]) |

G1 (W/C = 0.50—0.56) | G2 (W/C = 0.56—0.60) |

|---|---|---|

| 200 (0.9) | -2.17 | -7.94 |

| 100 (1.8) | -1.09 | -7.94 |

| 50 (3.7) | -0.15 | -5.11 |

| Table 2 equations | Eqs. (11)–(14) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| W/C = 0.50 and 0.60 | Average | 0.88 | 1.02 |

| Standard division | 0.21 | 0.20 | |

| All data | Average | 0.95 | 1.00 |

| Standard division | 0.15 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).