Submitted:

14 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Collection of Primary Sequences and 3D Structures of Human Serpin Superfamily Members

Multiple Sequence Alignment

Subcellular Distribution Data Retrieval of Human Serpins

NLS and NES Analysis

Assessment of the Solvent Accessibility of the NES Motif

Cell Culture and Immunofluorescence Staining

Mitochondrial Isolation and Western Blotting

Results

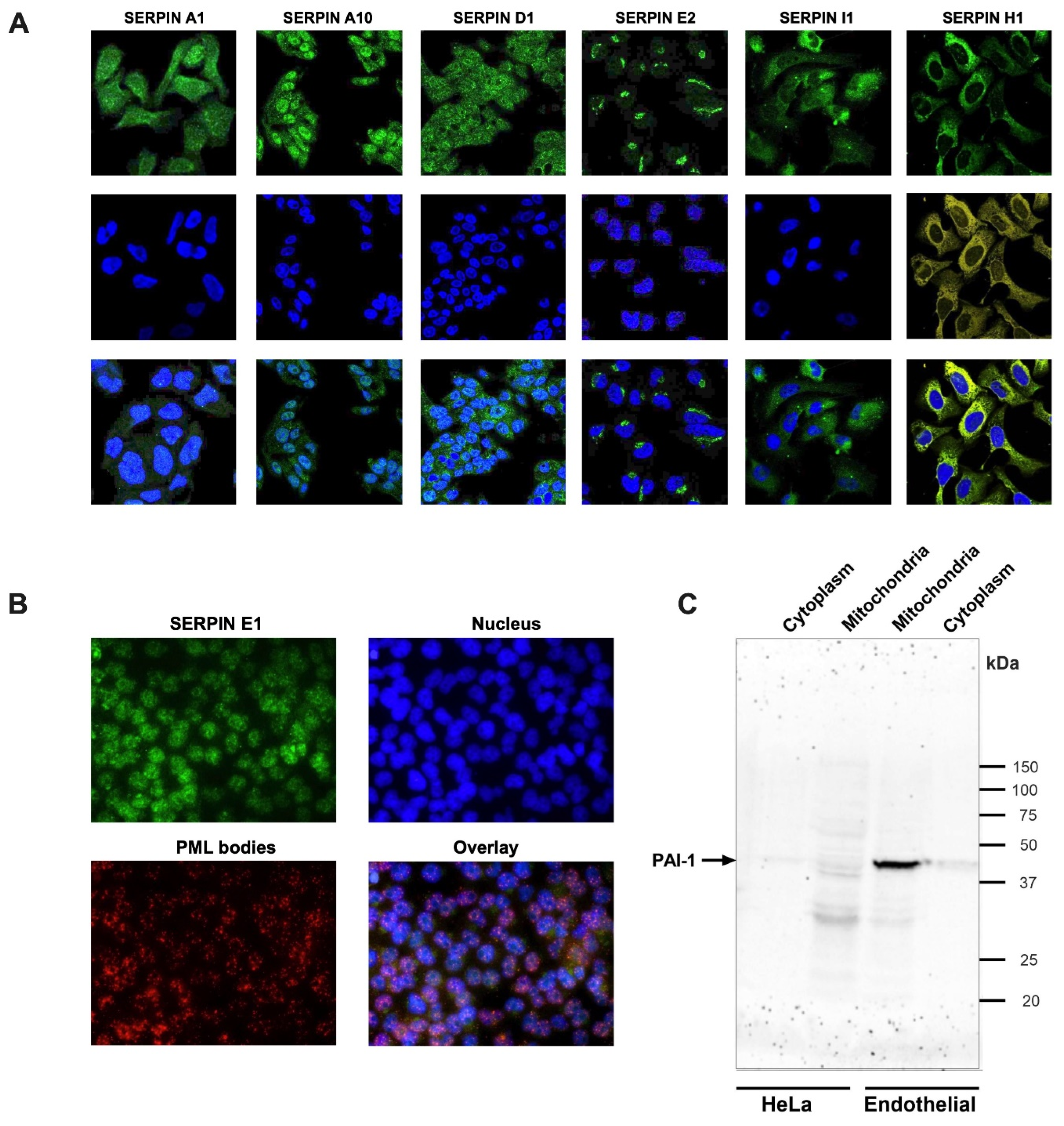

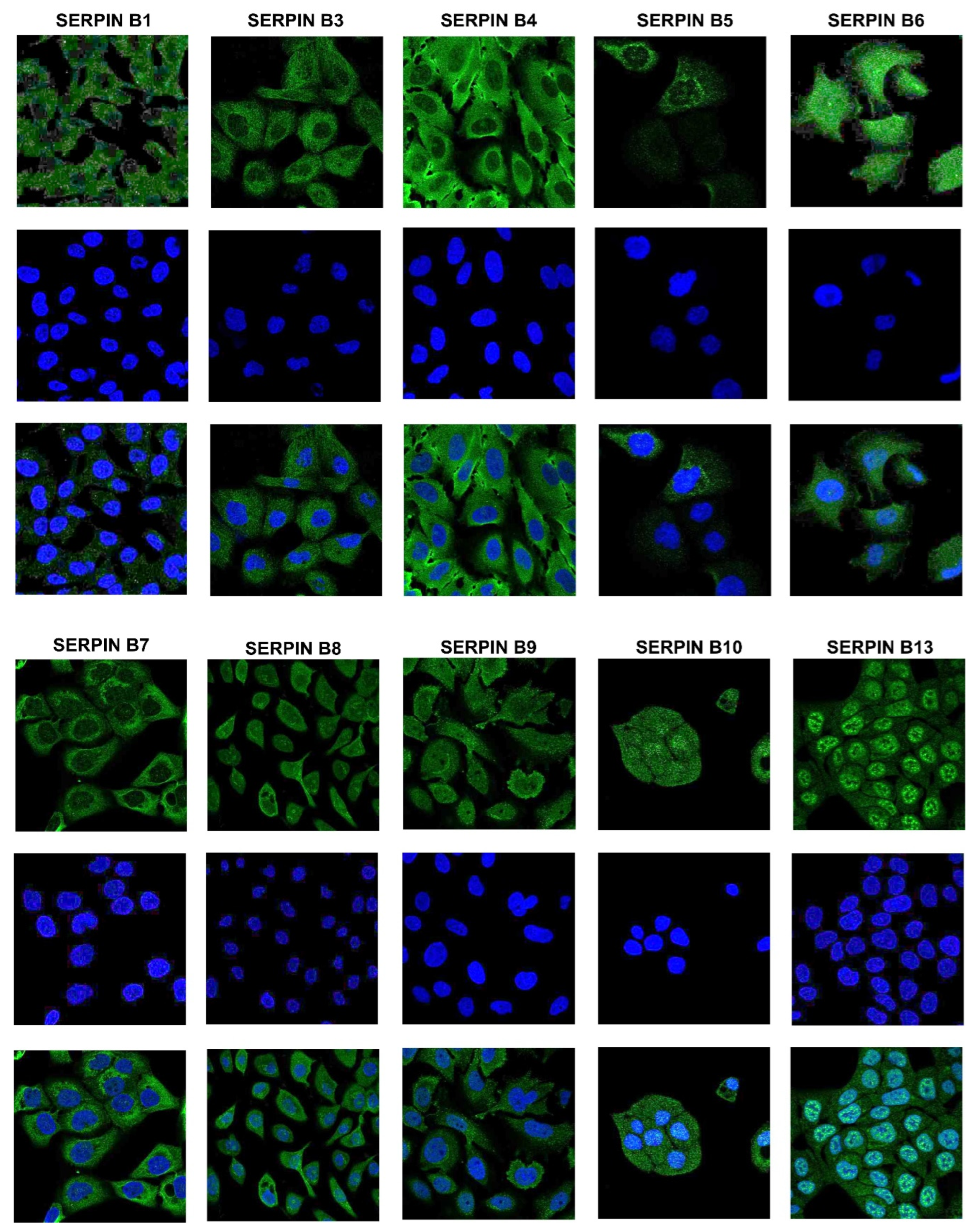

Various Secretory Serpins from Different Clades are Not Obligatory Extracellular and Are Found to Be Localized Inside the Cells

Various Serpins are Localized in the Nucleus and Have Potential Nuclear Localization Signals

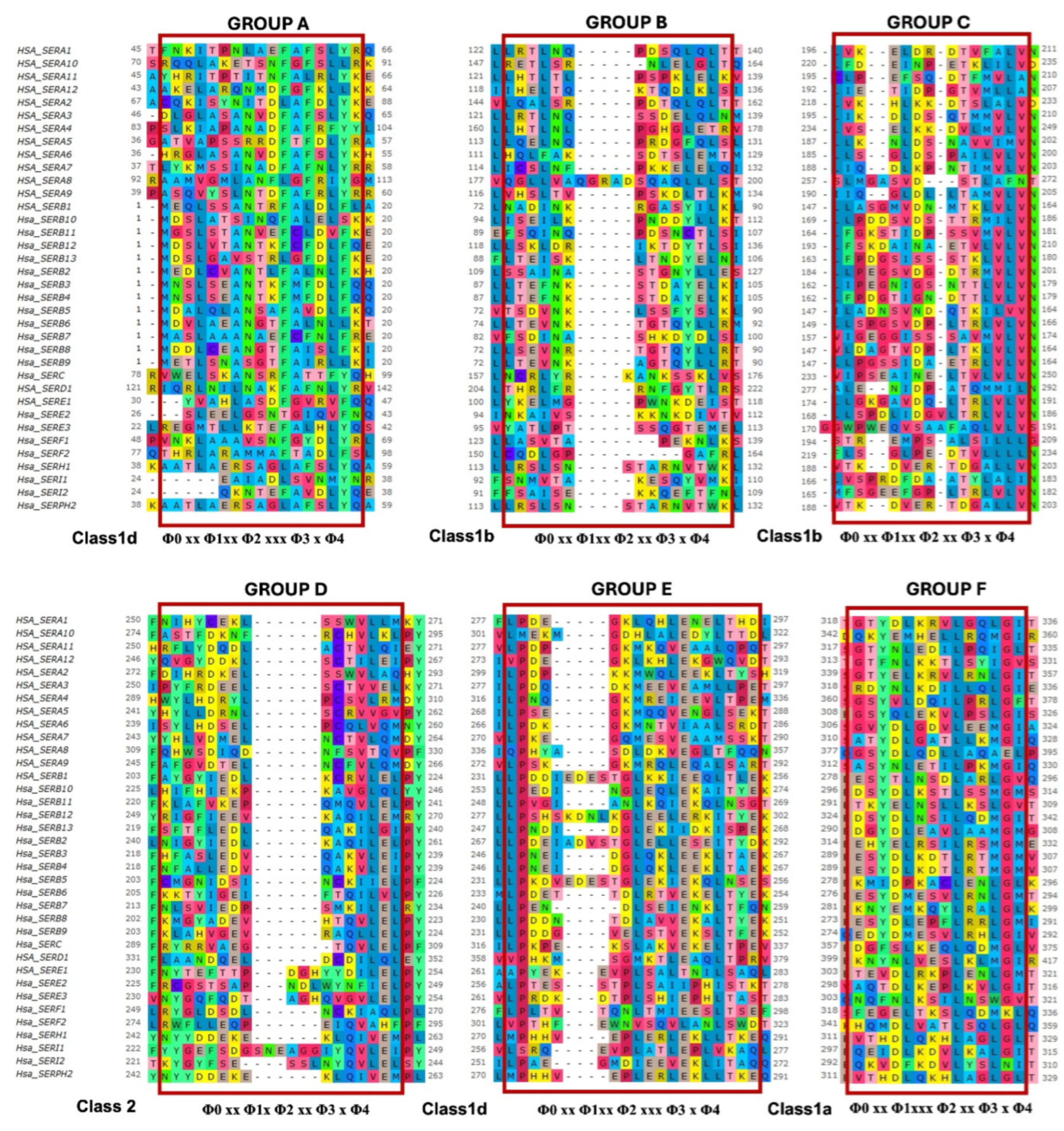

Identification of Potential Nuclear Export Signals in the Serpin Superfamily

Conservation of Identified NES Motifs in Human SERPIN Superfamily

Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

References

- Law, R.H.P.; Zhang, Q.; McGowan, S.; Buckle, A.M.; Silverman, G.A.; Wong, W.; Rosado, C.J.; Langendorf, C.G.; Pike, R.N.; Bird, P.I.; et al. An overview of the serpin superfamily. Genome Biol. 2006, 7, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, G.A.; Whisstock, J.; Askew, D.J.; Pak, S.C.; Luke, C.J.; Cataltepe, S.; Irving, J.A.; Bird, P.I. Human clade B serpins (ov-serpins) belong to a cohort of evolutionarily dispersed intracellular proteinase inhibitor clades that protect cells from promiscuous proteolysis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004, 61, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gent, D.; Sharp, P.; Morgan, K.; Kalsheker, N. Serpins: structure, function and molecular evolution. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2003, 35, 1536–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gettins, P.G.W. Serpin Structure, Mechanism, and Function. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 4751–4804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, J.A.; Pike, R.N.; Lesk, A.M.; Whisstock, J.C. Phylogeny of the Serpin Superfamily: Implications of Patterns of Amino Acid Conservation for Structure and Function. Genome Res. 2000, 10, 1845–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Bayesian phylogeny analysis of vertebrate serpins illustrates evolutionary conservation of the intron and indels based six groups classification system from lampreys for ∼500 MY. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubala, M.H.; DeClerck, Y.A. The plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 paradox in cancer: a mechanistic understanding. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2019, 38, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, M.A.; Mortimer, M.D.; Buckle, A.M.; Minh, B.Q.; Jackson, C.J. A Comprehensive Phylogenetic Analysis of the Serpin Superfamily. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 2915–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlot, P.; Brünnert, D.; Kaushik, V.; Yadav, A.; Bage, S.; Gaur, K.; Saini, M.; Ehrhardt, J.; Manjunath, G.K.; Kumar, A.; et al. Unconventional localization of PAI-1 in PML bodies: A possible link with cellular growth of endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 39, 101793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, P.I.; Ferreira, Z.; Martins, M.; Figueiredo, J.; Silva, D.I.; Castro, P.; Morales-Hojas, R.; Simões-Correia, J.; Seixas, S. SERPINA2 Is a Novel Gene with a Divergent Function from SERPINA1. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e66889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Nagata, K. Biology of Hsp47 (Serpin H1), a collagen-specific molecular chaperone. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 62, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wu, T.; Zhang, B.; Liu, S.; Song, W.; Qiao, J.; Ruan, H. Types of nuclear localization signals and mechanisms of protein import into the nucleus. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosugi, S.; Hasebe, M.; Matsumura, N.; Takashima, H.; Miyamoto-Sato, E.; Tomita, M.; Yanagawa, H. Six Classes of Nuclear Localization Signals Specific to Different Binding Grooves of Importin α. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Görlich, D.; Kutay, U. Transport Between the Cell Nucleus and the Cytoplasm. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1999, 15, 607–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, T.M.; MacNeil, K.M.; Mymryk, J.S. Piggybacking on Classical Import and Other Non-Classical Mechanisms of Nuclear Import Appear Highly Prevalent within the Human Proteome. Biology 2020, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, H.Y.J.; Fu, S.-C.; Chook, Y.M. Nuclear export receptor CRM1 recognizes diverse conformations in nuclear export signals. eLife 2017, 6, RP89040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Pei, J.; Baumhardt, J.M.; Chook, Y.M.; Grishin, N.V. Structural prerequisites for CRM1-dependent nuclear export signaling peptides: accessibility, adapting conformation, and the stability at the binding site. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosugi, S.; Hasebe, M.; Tomita, M.; Yanagawa, H. Nuclear Export Signal Consensus Sequences Defined Using a Localization-Based Yeast Selection System. Traffic 2008, 9, 2053–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UniProt Consortium UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D609–D617. [CrossRef]

- Sievers, F.; Higgins, D.G. Clustal Omega for making accurate alignments of many protein sequences. Protein Sci. 2017, 27, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, F.; Wilm, A.; Dineen, D.; Gibson, T.J.; Karplus, K.; Li, W.; Lopez, R.; McWilliam, H.; Remmert, M.; Söding, J.; et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011, 7, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M.; The UGENE Team. Unipro UGENE: A unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thul, P.J.; Åkesson, L.; Wiking, M.; Mahdessian, D.; Geladaki, A.; Ait Blal, H.; Alm, T.; Asplund, A.; Björk, L.; Breckels, L.M.; et al. A subcellular map of the human proteome. Science 2017, 356, eaal3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orre, L.M.; Vesterlund, M.; Pan, Y.; Arslan, T.; Zhu, Y.; Woodbridge, A.F.; Frings, O.; Fredlund, E.; Lehtiö, J. SubCellBarCode: Proteome-wide Mapping of Protein Localization and Relocalization. Mol. Cell 2019, 73, 166–182.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otlewski, J.; Jelen, F.; Zakrzewska, M.; Oleksy, A. The many faces of protease–protein inhibitor interaction. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, V.; Brünnert, D.; Hanschmann, E.-M.; Sharma, P.K.; Anand, B.G.; Kar, K.; Kateriya, S.; Goyal, P. The intrinsic amyloidogenic propensity of cofilin-1 is aggravated by Cys-80 oxidation: A possible link with neurodegenerative diseases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 569, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remold-O'DOnnell, E. The ovalbumin family of serpin proteins. FEBS Lett. 1993, 315, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, G.A.; Bird, P.I.; Carrell, R.W.; Church, F.C.; Coughlin, P.B.; Gettins, P.G.; Irving, J.A.; Lomas, D.A.; Luke, C.J.; Moyer, R.W.; et al. The serpins are an expanding superfamily of structurally similar but functionally diverse proteins. Evolution, mechanism of inhibition, novel functions, and a revised nomenclature. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 33293–33296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigami, S.; Sandkvist, M.; Tsui, F.; Moore, E.; Coleman, T.A.; Lawrence, D.A. Identification of a novel targeting sequence for regulated secretion in the serine protease inhibitor neuroserpin. Biochem. J. 2007, 402, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raykhel, I.; Alanen, H.; Salo, K.; Jurvansuu, J.; Nguyen, V.D.; Latva-Ranta, M.; Ruddock, L. A molecular specificity code for the three mammalian KDEL receptors. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 179, 1193–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanen, H.I.; Williamson, R.A.; Howard, M.J.; Hatahet, F.S.; Salo, K.E.H.; Kauppila, A.; Kellokumpu, S.; Ruddock, L.W. ERp27, a New Non-catalytic Endoplasmic Reticulum-located Human Protein Disulfide Isomerase Family Member, Interacts with ERp57. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 33727–33738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Khan, A.U.; Dai, J.; Ouyang, J. Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade E, member 2 in physiology and pathology: recent advancements. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1334931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsara, R.D.; Ploplis, V.A. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1: The double-edged sword in apoptosis. Thromb. Haemost. 2008, 100, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medcalf, R.L.; Stasinopoulos, S.J. The undecided serpin. The ins and outs of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 2. FEBS J. 2005, 272, 4858–4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulet, B.; Kennette, W.; Ablack, A.; O Postenka, C.; Hague, M.N.; Mymryk, J.S.; Tuck, A.B.; Giguère, V.; Chambers, A.F.; Lewis, J.D. Nuclear localization of maspin is essential for its inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis. Lab Invest 2011, 91, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longhi, M.T.; Silva, L.E.; Pereira, M.; Magalhães, M.; Reina, J.; Vitorino, F.N.L.; Gumbiner, B.M.; da Cunha, J.P.C.; Cella, N. PI3K-AKT, JAK2-STAT3 pathways and cell–cell contact regulate maspin subcellular localization. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 19, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, C.H.; Blink, E.J.; Hirst, C.E.; Buzza, M.S.; Steele, P.M.; Sun, J.; Jans, D.A.; Bird, P.I. Nucleocytoplasmic Distribution of the Ovalbumin Serpin PI-9 Requires a Nonconventional Nuclear Import Pathway and the Export Factor Crm1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 5396–5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, I.; Granero-Moya, I.; Chahare, N.R.; Clein, K.; Molina-Jordán, M.; Beedle, A.E.M.; Elosegui-Artola, A.; Abenza, J.F.; Rossetti, L.; Trepat, X.; et al. Mechanical force application to the nucleus regulates nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nat. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soman, A.; Nair, S.A. Unfolding the cascade of SERPINA3: Inflammation to cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2022, 1877, 188760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, M.; Pardo–Saganta, A.; Alvarez–Asiain, L.; Di Scala, M.; Qian, C.; Prieto, J.; Avila, M.A. Nuclear α1-Antichymotrypsin Promotes Chromatin Condensation and Inhibits Proliferation of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 818–828.e814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Pandey, D.; Behring, A.; Siess, W. Inhibition of Nuclear Import of LIMK2 in Endothelial Cells by Protein Kinase C-dependent Phosphorylation at Ser-283. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 27569–27577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardo, F.; Li, X.; Siddiq, F.; Singh, R.; Al-Abbadi, M.; Pass, H.I.; Sheng, S. Maspin nuclear localization is linked to favorable morphological features in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer 2006, 51, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, L.; Vanselow, K.; Skogs, M.; Toyoda, Y.; Lundberg, E.; Poser, I.; Falkenby, L.G.; Bennetzen, M.; Westendorf, J.; A Nigg, E.; et al. Novel asymmetrically localizing components of human centrosomes identified by complementary proteomics methods. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 1520–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauk JJ, Nikitakis N, and Siavash H. Hsp47 a novel collagen binding serpin chaperone, autoantigen and therapeutic target. Front. Biosci. 2005, 10, 107–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.-M.; Mi, Y.-S.; Yu, F.-D.; Han, Y.; Liu, X.-S.; Lu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, S.-L.; Ye, L.; Liu, T.-T.; et al. SERPINA4 is a novel independent prognostic indicator and a potential therapeutic target for colorectal cancer. Am J Cancer Res 2016, 6, 1636–1649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Navarro, A.; González-Soria, I.; Caldiño-Bohn, R.; Bobadilla, N.A. Integrative view of serpins in health and disease: the contribution of SerpinA3. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2021, 320, C106–C118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janciauskiene, S.; Lechowicz, U.; Pelc, M.; Olejnicka, B.; Chorostowska-Wynimko, J. Diagnostic and therapeutic value of human serpin family proteins. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 175, 116618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Water, N.; Tan, T.; Ashton, F.; O'Grady, A.; Day, T.; Browett, P.; Ockelford, P.; Harper, P. Mutations within the protein Z-dependent protease inhibitor gene are associated with venous thromboembolic disease: a new form of thrombophilia. Br. J. Haematol. 2004, 127, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Zhou, H.; Zeng, T.-T.; Jin, C.; Lin, J.-R.; Gao, S.; Li, Y.; Guan, X.-Y.; et al. SERPINA11 Inhibits Metastasis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Suppressing MEK/ERK Signaling Pathway. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2021, 8, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillen, M.; Declerck, P.J. A Narrative Review on Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 and Its (Patho)Physiological Role: To Target or Not to Target? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madjene, C.; Boutigny, A.; Bouton, M.-C.; Arocas, V.; Richard, B. Protease Nexin-1 in the Cardiovascular System: Wherefore Art Thou? Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 652852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| S.No. | Clade | Protein code | HPA | Cell line | Subcell Barcode | Cell line | Literature |

| 1. | A | SERPINA1 | Vesicles | HepG2 | N/A | N/A | ER [10] |

| 2. | SERPINA2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ER [10] | |

| 3. | SERPINA3 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Nucleus [40], [39] |

|

| 4. | SERPINA4 | N/A | N/A | Cytoplasm | MCF7 | N/A | |

| 5. | SERPINA6 | N/A | N/A | Cytoplasm | MCF7 | N/A | |

| 6. | SERPINA7 | N/A | N/A | Cytoplasm | MCF7 | N/A | |

| 7. | SERPINA10 | Cytosol, Nucleus | HepG2 | Cytoplasm | H322 | N/A | |

| 8. | B | SERPINB1 | Cytoplasm | SK-MEL-30 | Cytoplasm, cytoskeleton | H322 | N/A |

| 9. | SERPINB2 | N/A | N/A | Cytoplasm | A431, H322 | Nucleus [34] | |

| 10. | SERPINB3 | Cytoplasm, PM | A431 | Cytoplasm | H322 | N/A | |

| 11. | SERPINB4 | Cytoplasm, PM | U2OS | Cytoplasm | H322, HCC827 | N/A | |

| 12. | SERPINB5 | Vesicles | A431 | Cytoplasm | A431, H322, MCF7, HCC827 | Nucleus [35,36,42] | |

| 13. | SERPINB6 | Centrosome | U251-MG | NA | A431 | Centrosome [43] | |

| 14. | SERPINB7 | Mitochondria, ER | HaCaT | NA | H322 | N/A | |

| 15. | SERPINB8 | Golgi bodies, Nucleus | HBEC3KT | Cytoplasm, cytoskeleton | A431, HCC827 | N/A | |

| 16. | SERPINB9 | Cytoplasm, Nucleus | SiHa | Cytoplasm, cytoskeleton | HCC827 | Nucleus, cytoplasm [37] | |

| 17. | SERPINB10 | Cytoplasm, Nucleus | HaCaT | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 18. | SERPINB11 | N/A | N/A | Nuclear | HCC827 | N/A | |

| 19. | SERPINB12 | N/A | N/A | Mitochondria | HCC827 | N/A | |

| 20. | SERPINB13 | Cytoplasm, Nuclear speckles | RT-4 | Cytoplasm | H322 | N/A | |

| 21. | D | SERPIND1 | Vesicles | HepG2 | Cytoplasm | U251 | N/A |

| 22. | E | SERPINE1 | N/A | N/A | Mitochondria, ER | U251 | Nucleus [9] |

| 23. | SERPINE2 | Golgi bodies | SK-MEL-30 | PM | U251 | N/A | |

| 24. | F | SERPINF1 | N/A | N/A | Cytoplasm cytoskeleton | H322 | N/A |

| 25. | G | SERPING1 | N/A | N/A | Cytoplasm | H322, MCF7 | N/A |

| 26. | H | SERPINH1 | ER | U2OS | Nucleosol, ER | U251, A431 | ER [11,44] |

| 27 | I | SERPINI1 | Cytoplasm, vesicles | U251-MG | N/A | N/A | ER, Golgi bodies, vesicles [29] |

| S. No. | Name | Position | cNLS Mapper | ELM Database | Manual curation | ||

| Sequence | Score | Classical NLS | Non classical NLS (PY-NLS) | ||||

| 1 | SERPINA2 | 11-16 350-378 203-220 |

RNLGITKIFSNEADLSGVSQEAPLKLSKA |

5.3 | N/A |

EKRTGRKVVDLVKHLKKD |

HRLGPY |

| 2 | SERPINA3 | 247-253 | N/A | N/A | HHLTIPY | ||

| 3 | SERPINA5 | 254-260 294-300 292-299 |

N/A |

FKKRQLE KMFKKRQL |

RVVGVPY | ||

| 4 | SERPINA9 | 171-189 280-301 |

N/A | N/A | AQARINSHVKKKTQGKVV RQLEQALSARTLRKWSHSLQKR |

||

| 5 | SERPINA10 | 179-206 238-267 286-292 |

FNLSKRYFDTECVPMNFRNASQAKRLMN FKGKWLTPFDPVFTEVDTFHLDKYKTIKVP |

5.4 6.4 |

N/A |

HVLKLPY |

|

| 6 | SERPINA12 | 39-66 339-345 385-390 |

WKQRMAAKELARQNMDFGFKLLKKLAFN | 5.35 | N/A | N/A |

LTKIAPY KIDKPY |

| 7 | SERPINB1 | 168-197 189-205 185-200 215-221 |

KGNWKDKFMKEATTNAPFRLNKKDRKTVKM | 5.1 |

KKDRKTVKMMYQKKKFA |

FRLNKKDRKTVKMMYQ |

RVLELPY |

| 8 | SERPINB2 | 143-172 165-181 |

RLCQKYYSSEPQAVDFLECAEEARKKINSW | 6.3 | N/A |

ARKKINSWVKTQTKGKI |

|

| 9 | SERPINB3 | 143-160 229-236 |

N/A | N/A | SRKKINSWVESQTNEKIK |

AKVLEIPY |

|

| 10 | SERPINB4 | 142-150 | N/A | N/A | ESRKKINSW | ||

| 11 | SERPINB5 | 83-114 87-114 |

FYSLKLIKRLYVDKSLNLSTEFISSTKRPYAK KLIKRLYVDKSLNLSTEFISSTKRPYAK |

5.1 6.1 |

N/A | N/A | |

| 12 | SERPINB8 | 176-191 | N/A | N/A | N/A | RKYTRGMLFKTNEEKK | |

| 13 | SERPINB10 | 73-83 222-233 |

N/A | N/A | N/A | EKKRKMEFNLS MKKKLHIFHIEK |

|

| 14 | SERPINB13 | 143-155 | N/A | N/A | ESRKKINSWVESK | ||

| 15 | SERPIND1 | 203-219 | N/A | N/A | RKLTHRLFRRNFGYTLR | ||

| 16 | SERPINE1 | 54-61 | N/A | N/A | N/A | RNVVFSPY | |

| 17 | SERPINI1 | 283-289 | N/A | VKKQKVE | N/A | ||

| Clade | Position | Sequence | Serpin | Group | Class | Consensus class |

| A | 116-130 | DVHRGFQHLLHTLNL | A4 | U | 1a | Φ0 xx Φ1xxx Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 |

| 118-133 | SDTSLEMTMGNALFL | A6 | U | 1c | Φ0 xx Φ1xxx Φ2 xxx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| 307-321 | SGVYDLGDVLEEMGI | A6 | F | 1a | Φ0 xx Φ1xxx Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| 300-312 | VVLMEKMGDHLAL | A10 | U | 1d | Φ0 xx Φ1xx Φ2 xxx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| 92-106 | QANTSALILEGLGFN | A11 | D | 2 | Φ0 xx Φ1x Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| B | 238-252 | DESTGLKKIEEQLTL | B1 | E | 1d | Φ0 xx Φ1xx Φ2 xxx Φ3 x Φ4 |

| 279-293 | EESYTLNSDLARLGV | B1 | ||||

| 259-273 | TKPENLDFIEVNVSL | B1 | F | 1a | Φ0 xx Φ1xxx Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| 268-282 | LPDEIADVSTGLELL | B2 | E | 1d | Φ0 xx Φ1xx Φ2 xxx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| 292-306 | ESYDLKDTLRTMGMV | B4 | F | 1a | Φ0 xx Φ1xxx Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| 74-88 | TSDVNKLSSFYSLKL | B5 | B | 1b | Φ0 xx Φ1xx Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| 149-163 | LLSPGSVDPLTRLVL | B6 | C | 1b | Φ0 xx Φ1xx Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| 241-255 | LPENDLSEIENKLTF | B7 | E | 1d | Φ0 xx Φ1xx Φ2 xxx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| 283-297 | KNYEMKQYLRALGLK | B7 | F | 1a | Φ0 xx Φ1xxx Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| 274-288 | EESYDLEPFLRRLGM | B8 | ||||

| 297-311 | ENSYDLKSTLSSMGM | B10 | ||||

| 305-319 | EDSYDLNSILQDMGI | B12 | ||||

| 218-232 | QMMFMKKKLHIFHIE | B10 | U | 1a | Φ0 xx Φ1xxx Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| 221-235 | SFTFLEDLQAKILGI | B13 | D | 2 | Φ0 xx Φ1x Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| 250-262 | NDIDGLEKIIDKI | B13 | U | 1aR | Φ0 x Φ1xx Φ2 xxx Φ3 xx Φ4 | |

| C | 358-372 | EDGFSLKEQLQDMGL | C1 | F | 1a | Φ0 xx Φ1xxx Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 |

| E | 306-318 | ETEVDLRKPLENLGM | E1 | |||

| 150-164 | LSPDLIDGVLTRLVL | E2 | U | 1a | Φ0 xx Φ1xxx Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| 175-189 | DGVLTRLVLVNAVYF | E2 | C | 1b | Φ0 xx Φ1xx Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 | |

| 318-332 | VTDLFDPLKANLKGI | E3 | U | 1aR | Φ0 x Φ1xx Φ2 xxx Φ3 xx Φ4 | |

| H | 312-326 | EVTHDLQKHLAGLGL | H1 | F | 1a | Φ0 xx Φ1xxx Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 |

| I | 298-312 | EQEIDLKDVLKALGI | I1 | F | 1a | Φ0 xx Φ1xxx Φ2 xx Φ3 x Φ4 |

| S.no. | Clade | Protein code | NLS | NES | S.no. | Clade | Protein code | NLS | NES |

| 1. | A | SERPINA2 | NLS | N/A | 15. | B. | SERPINB6 | N/A | NES |

| 2. | SERPINA3 | NLS | N/A | 16. | SERPINB7 | N/A | NES | ||

| 3. | SERPINA4 | N/A | NES | 17. | SERPINB8 | NLS | NES | ||

| 4. | SERPINA5 | NLS | N/A | 18. | SERPINB10 | NLS | NES | ||

| 5. | SERPINA6 | N/A | NES | 19. | SERPINB12 | N/A | NES | ||

| 6. | SERPINA9 | NLS | N/A | 20. | SERPINB13 | NLS | NES | ||

| 7. | SERPINA10 | NLS | NES | 21. | C. | SERPINC1 | N/A | NES | |

| 8. | SERPINA11 | N/A | NES | 22. | D. | SERPIND1 | NLS | N/A | |

| 9. | SERPINA12 | NLS | N/A | 23. | E. | SERPINE1 | NLS | NES | |

| 10. | B | SERPINB1 | NLS | NES | 24. | SERPINE2 | N/A | NES | |

| 11. | SERPINB2 | NLS | NES | 25. | SERPINE3 | N/A | NES | ||

| 12. | SERPINB3 | NLS | N/A | 26. | H. | SERPINH1 | N/A | NES | |

| 13. | SERPINB4 | NLS | NES | 27. | I. | SERPINI1 | NLS | NES | |

| 14. | SERPINB5 | NLS | NES | ||||||

| S.No. | Clade | Protein code | Localization signal | Functions (protease inhibition-independent) and associated diseases | References | |

| NLS | NES | |||||

| 1. | A | SERPINA3 | NLS | N/A | Inflammation, apoptosis, cancer diagnosis, Alzheimer’s and emphysema | [39,40] |

| 2. | SERPINA4 | N/A | NES | Inflammation, Diabetic retinopathy, novel prognostic indicator and therapeutic target for Colorectal cancer. | [45,46] | |

| 3. | SERPINA5 | NLS | N/A | Coagulation, sperm development, tumor cell invasion and metastasis | [28] | |

| 4. | SERPINA6 | N/A | NES | Hormone transport | [28] | |

| 5. | SERPINA9 | NLS | N/A | B cell development | [28] | |

| 6. | SERPINA10 | NLS | NES | Venous thromboembolic disease | [47,48] | |

| 7. | SERPINA11 | N/A | NES | Hepatocellular carcinoma | [47,49] | |

| 8. | SERPINA12 | NLS | N/A | Anti-insulin resistance and Obesity | [28] | |

| 9. | E | SERPINE1 | NLS | NES | Cell Growth , aging, cancer prognosis | [7,9,50] |

| 10. | SERPINE2 | N/A | NES | Neurotrophic factors, emphysema, thoracic aortic aneurysms and atherosclerosis. | [28,46,47,51] | |

| 11. | H | SERPINH1 | N/A | NES | Rheumatoid arthritis, cancer and aortic stenosis | [11,44] |

| 12. | I | SERPINI1 | NLS | NES | Neurotrophic factors | [28] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).