1. Introduction

The proprotein convertases are a mammalian family of nine secretory serine proteases related to bacterial subtilases and yeast kexin (PCs or PCSKs), implicated in various biological processes as well as in pathologies such as cancer/metastasis [

1]. PCs are responsible for the cleavage and maturation of a wide variety of precursor proteins [

1]. The first seven PCs cleave (↓) precursor proteins at specific single or paired basic amino acid (aa) within the motif (R/K)-(2X)n-(R/K)↓, where n = 0, 1, 2, or 3 spacer aa, and X is a variable amino acids (aa) [

1]. Cellular and animal studies demonstrated the implication of Furin [

2,

3], PC7 [

4], PACE4 [

5,

6,

7], and PCSK9 [

8,

9,

10] in cancer/metastasis. So far in the clinic, therapies targeting the last member of the family, PCSK9, are highly successful in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia and beyond [

11,

12]. The physiological roles of the ubiquitously expressed PC7 (gene PCSK7), the seventh member of the family [

13], remained obscure for a long time—however, very recently, Sachan et al. [

14] demonstrated that in mice, liver PC7 plays a critical role in enhancing apolipoprotein B (apoB) levels, and the silencing of its expression provided a promising treatment for diet-induced metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), a devastating pathology that affects at least 25% the population worldwide [

15].

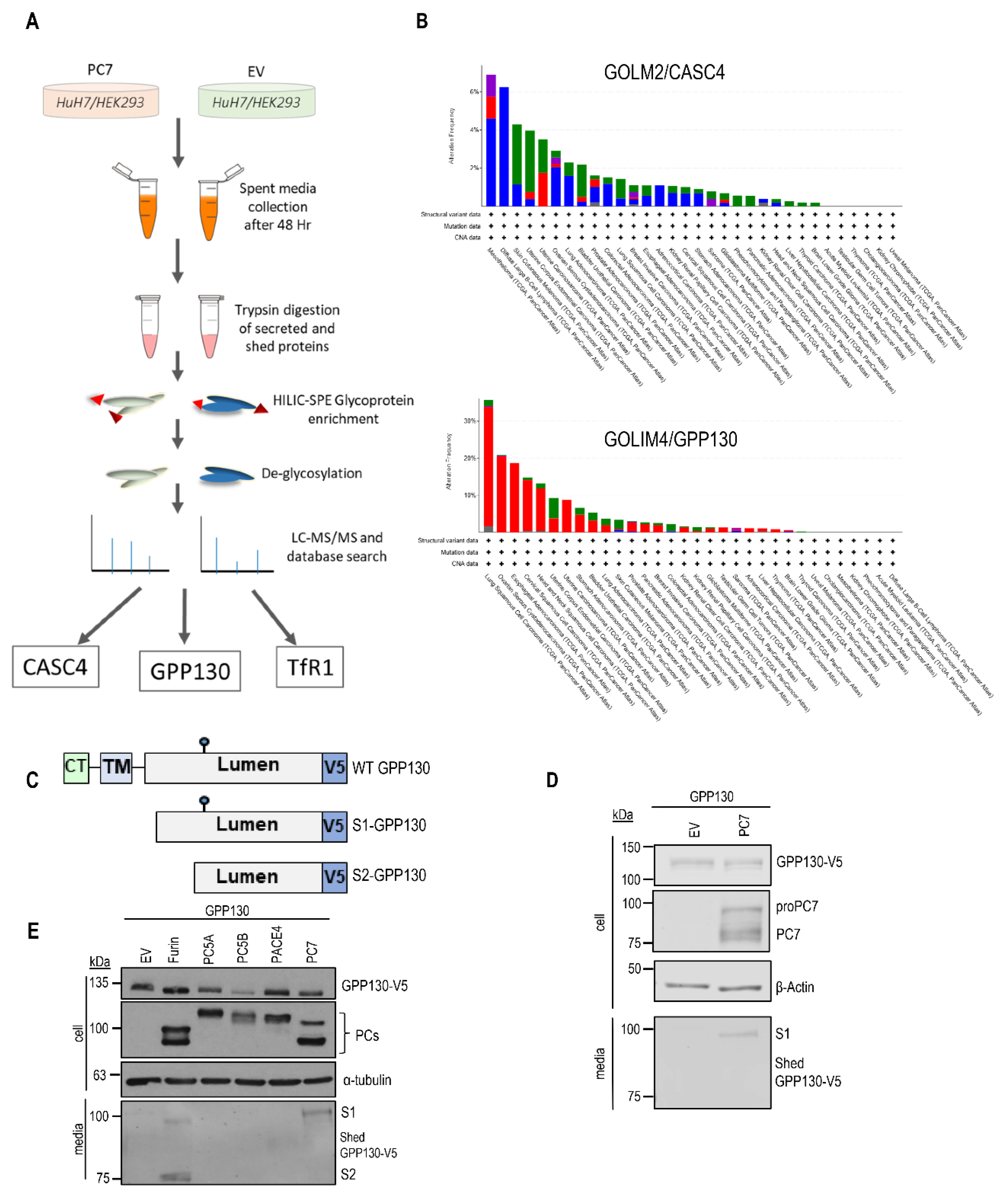

In our search for new PC7 substrates, a quantitative proteomics screen for selective enrichment of N-glycosylated polypeptides secreted from hepatic HuH7 cells overexpressing PC7 we identified two type-II transmembrane proteins that were shed into soluble secreted forms by PC7 and/or Furin: cancer susceptibility candidate 4 (CASC4) and Golgi Phosphoprotein of 130 kDa (GPP130) (

Figure 1A) [

4]. The latter study revealed that CASC4, especially its PC7/Furin-cleaved N-terminal membrane-bound fragment, enhanced the migration and invasion of triple-negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells [

4]. Our analysis from the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics database has shown that the expression of the genes coding for CASC4 and GPP130 are differentially modified in various cancers (

Figure 1B). However, GPP130 and its shedding were not functionally characterized, especially since GPP130 expression is amplified in up to 35% of patients with lung cancer and >10% in head-and-neck cancer patients (

Figure 1B). Herein, we have filled the knowledge gap on GPP130 and additionally compared the properties of GPP130 to those of CASC4.

GPP130 is a type-II transmembrane Golgi protein that has a small cytosolic tail, a 20 aa transmembrane domain followed by a luminal domain containing features that dictate its trafficking route [

16,

17]. Thus, it was demonstrated that GPP130 traffics from the cis-Golgi to the plasma membrane and back via the TGN38/46 bypass pathway [

18,

19]. Further investigations demonstrated that GPP130 traffics to early endosomes where it binds the Shiga toxin internalized into cell surface endosomes, and the complex is then sorted back to the Golgi and retrograde transported to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to exert its cytotoxic effects [

20,

21]. In addition, manganese (Mn

2+) treatment was also shown to induce GPP130 oligomerization, which in turn reroutes GPP130 into multivesicular bodies (MVBs) before trafficking to lysosomes for degradation [

22,

23]. Thus, GPP130 maintains intracellular Mn

2+ homeostasis by binding excess Mn

2+ in the Golgi lumen, thereby initiating the routing of Mn

2+-bound GPP130 to lysosomes for degradation. Indeed, Mn

2+ treatment inhibits the progression of multiple types of 3q-amplified malignancies by degrading GPP130, resulting in a secretory blockade that interrupts pro-survival autocrine loops and attenuates pro-metastatic processes in the tumor microenvironment [

24]. Therefore, GPP130 is thought to be a Golgi protein endowed with a unique trafficking route that shuttles cargo within the secretory pathway. The GPP130/GOLIM4 gene was also connected to head-and-neck cancer in a study investigating downstream targets of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STM1), a Ca

2+ channel protein member of the store-operated calcium entry (SOCE), a pathway activated upon reduction of Ca

2+ levels in the ER [

25]. In the above study, GPP130 expression was shown to be higher in head-and-neck cancer cells and suggested to be a downstream target of STM1 [

26]. Furthermore, GPP130 is implicated in cell cycle progression and cell proliferation by modulating the expression levels of MDM2 and CDK6 in head-and-neck cancer cells [

26]. Recently, it was also shown that miR-105-3p acts as an oncogene to promote the proliferation and metastasis of breast cancer cells by silencing GOLIM4 [

27] and that targeting miR-942-5p/GPP130 axis suppressed breast cancer malignant behavior [

28]. Finally, a non-biased proteomic analysis identified GPP130 as a novel target for the treatment of endometrial cancer [

29]. Thus, so far, the available data suggest that depending on the cancer type, GPP130 can act as a tumor suppressor or an oncogene. However, the specific role of GPP130 or its fragments in lung cancer has not been studied.

Because of the amplified expression of GPP130 in lung cancer patients (

Figure 1B), in the present study, we concentrated on the ex vivo growth function activity of GPP130 in the lung carcinoma A549 cell line. The functional implication of PC7/Furin in the cleavage of GPP130, as well as its cytosolic tail Cys-palmitoylation, were studied in more detail. We also compared the growth-promoting activities of GPP130 to those of CASC4 and their shed products. The data showed that GPP130 cleavage by PC7 and/or Furin results in enhanced cellular growth, likely due to the production of a secreted soluble form and an N-terminal membrane-bound fragment. The potential Cys-palmitoylation of the latter was found to reduce its growth-promoting activity. Conversely, blocking the PC7/Furin processing of GPP130 results in a substantial reduction of cellular growth. Thus, inhibition of PC7/Furin-induced shedding of GPP130 may represent a promising strategy for the reduction of lung cancer tumor growth.

3. Discussion

GPP130 is a Golgi resident protein with a unique trafficking pathway. Most of the literature covering GPP130 is related to its role in transporting the Shiga toxin intracellularly [

23]. In addition, investigations aiming at targeting GPP130 trafficking for therapeutic uses in the context of Shiga toxin infections have demonstrated that this protein is sensitive to Mn

2+ and can be rerouted for degradation in lysosomes following Mn

2+ treatment [

36]. However, other biological roles of GPP130, including its cell biology, remain unknown. Notably, a group interested in Ca

2+ signaling during tumor growth has recently highlighted the importance of GPP130 in cell cycle progression and showed that the knockdown of GPP130 severely impacts cell proliferation in head-and-neck cancer cells [

26].

Herein, we demonstrated that GPP130 is shed by PC7 and Furin at two distinct sites (S1 and S2) in its luminal domain, which would be expected to have dramatic consequences on the efficient binding and transport of the Shiga toxin. Site-directed mutagenesis revealed that the S1 site cleaved by PC7, and Furin occurs at Arg

70↓ and Lys

73↓, respectively (

Figure 3B), and that Furin is the only convertase that cleaves at Arg

277↓ (S2 site). Notably, site directed mutagenesis revealed that the PC7 cleavage at S1 occurs at H

RS

R70↓ and that Arg

70 at P1 and Arg

68 at P3 are critical but not His

67 at P4 (

Figure 3B). It is unusual that a P3 Arg would be critical for PC-cleavage, but His at P4 is present in other PC-substrates such as mouse pro-epidermal growth factor (proEGF) [

37].

We also demonstrated that the independent cleavages at S1 and S2 occur in distinct intracellular acidic compartments. Cleavage at S1 is inhibitable by dec-RVKR-cmk and NH

4Cl, suggesting that both PC7 and Furin process GPP130 in the TGN and/or acidic endosomes, as expected from the localization of PC7 activity in endosomes [

31,

38] and of Furin activity in the TGN and endosomes [

39]. In contrast, the S2 cleavage by Furin seems to occur in dec-RVKR-cmk resistant but NH

4Cl-sensitive acidic compartment(s) (

Figure 4). Interestingly, in the absence of overexpressed PC7 or Furin, GPP130 seems to be shed at a site closer to the transmembrane domain, possibly by an endogenous cell surface metalloprotease (more active in the presence of NH

4Cl), as suggested by the upward shift of S1 on Western blots (compare EV

versus PC7 or Furin in

Figure 4C-E). Finally, one drawback of this study is the need to overexpress PC7 or Furin to detect GPP130 shedding by endogenous proteases in either HEK293 or A549 cells. The identification of a lung cancer cell line with high enough endogenous PC7 and GPP130 levels may support our conclusions. In addition, analysis of the Cancer Genome Atlas database revealed that in breast cancer tumors, PC7 and GPP130/GOLIM4 are also highly expressed (

Supplemental Figure S2).

It is possible that GPP130 shedding by endogenous PC7 may be readily observed in cells derived from breast cancer tumors, e.g., MDA-MB-231 [

4], which is what this study is trying to mimic using PC7 overexpression in model cell lines.

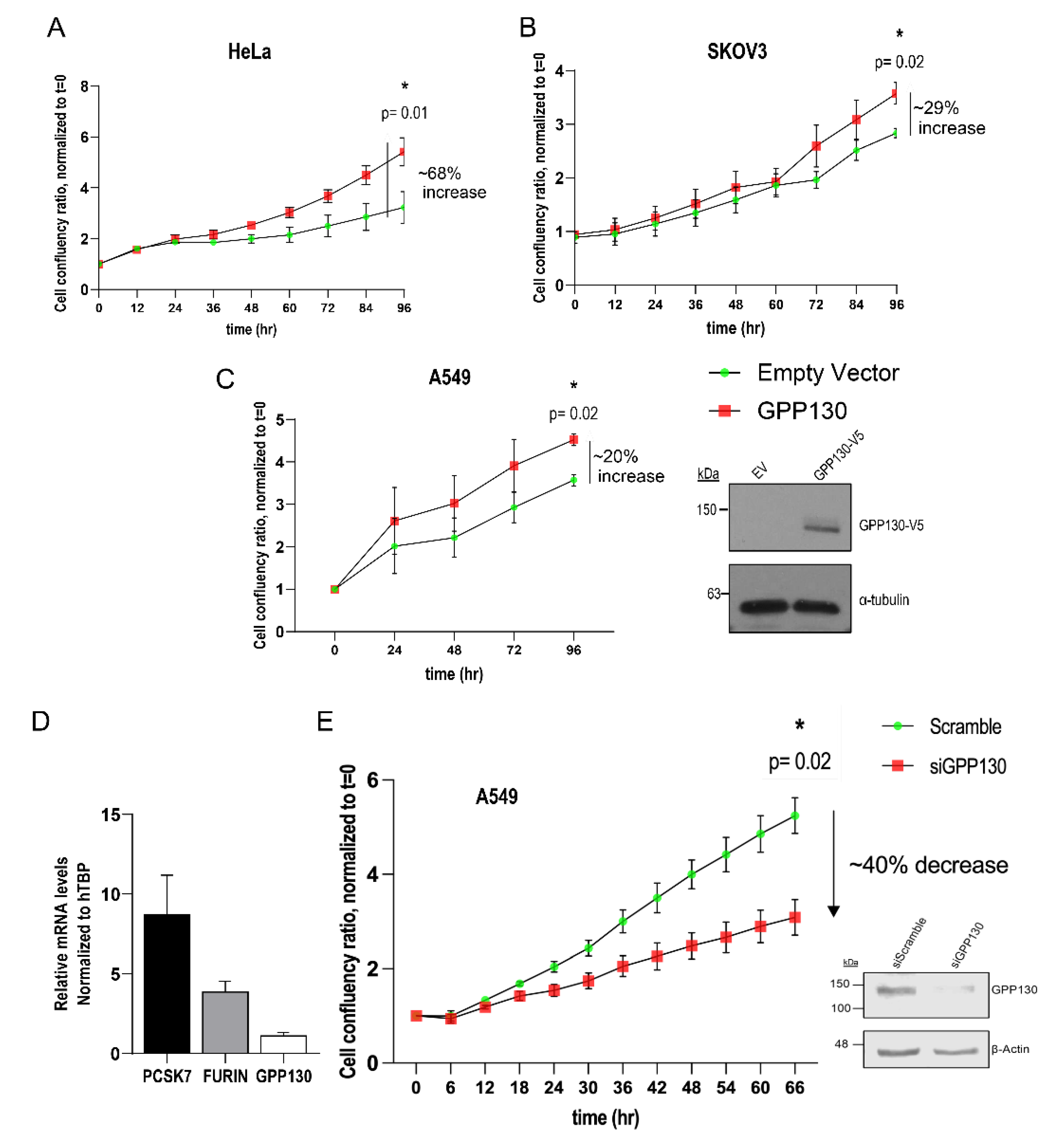

We next tested the effect of silencing endogenous GPP130 (siRNA) or its overexpression on the cellular proliferation of A549 cells (

Figure 5). As shown for head and neck cancer, it is plausible that the knockdown of GPP130 also leads to the perturbation of Stromal Interaction Molecule 1 (STIM1)-GOLIM4 signal axis in A549 cells, thereby reducing the cellular growth [

26]. Our data extends this GPP130-induced pro-proliferative activity to lung cancer A549 cells and reveals that it is the GPP130 shedding at S1 by PC7 and/or Furin that enhances such proliferative activity (

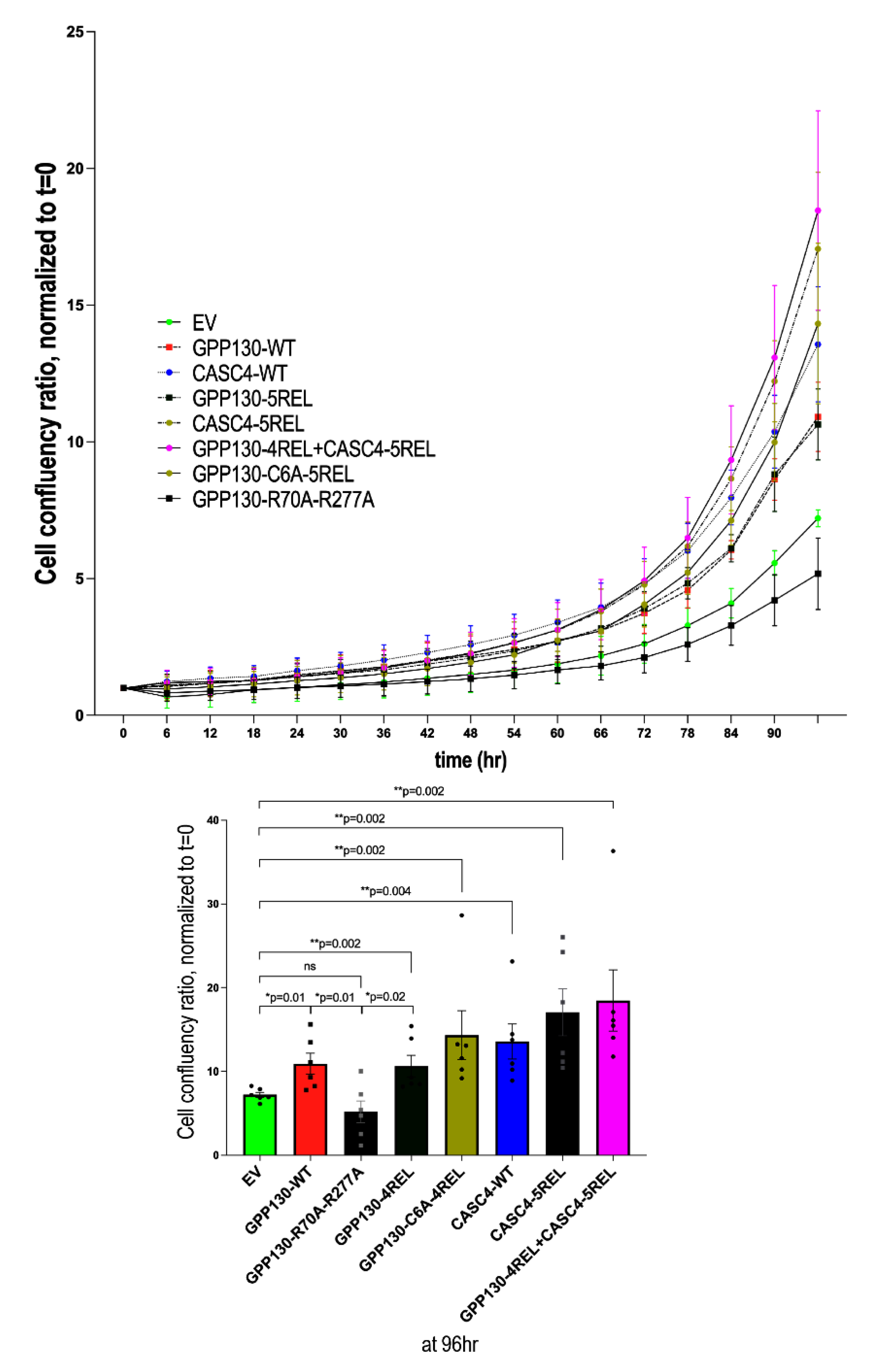

Figure 6). In contrast, the GPP130 R70A-R277A variant that is completely resistant to shedding showed no proliferative activity at all (

Figure 7).

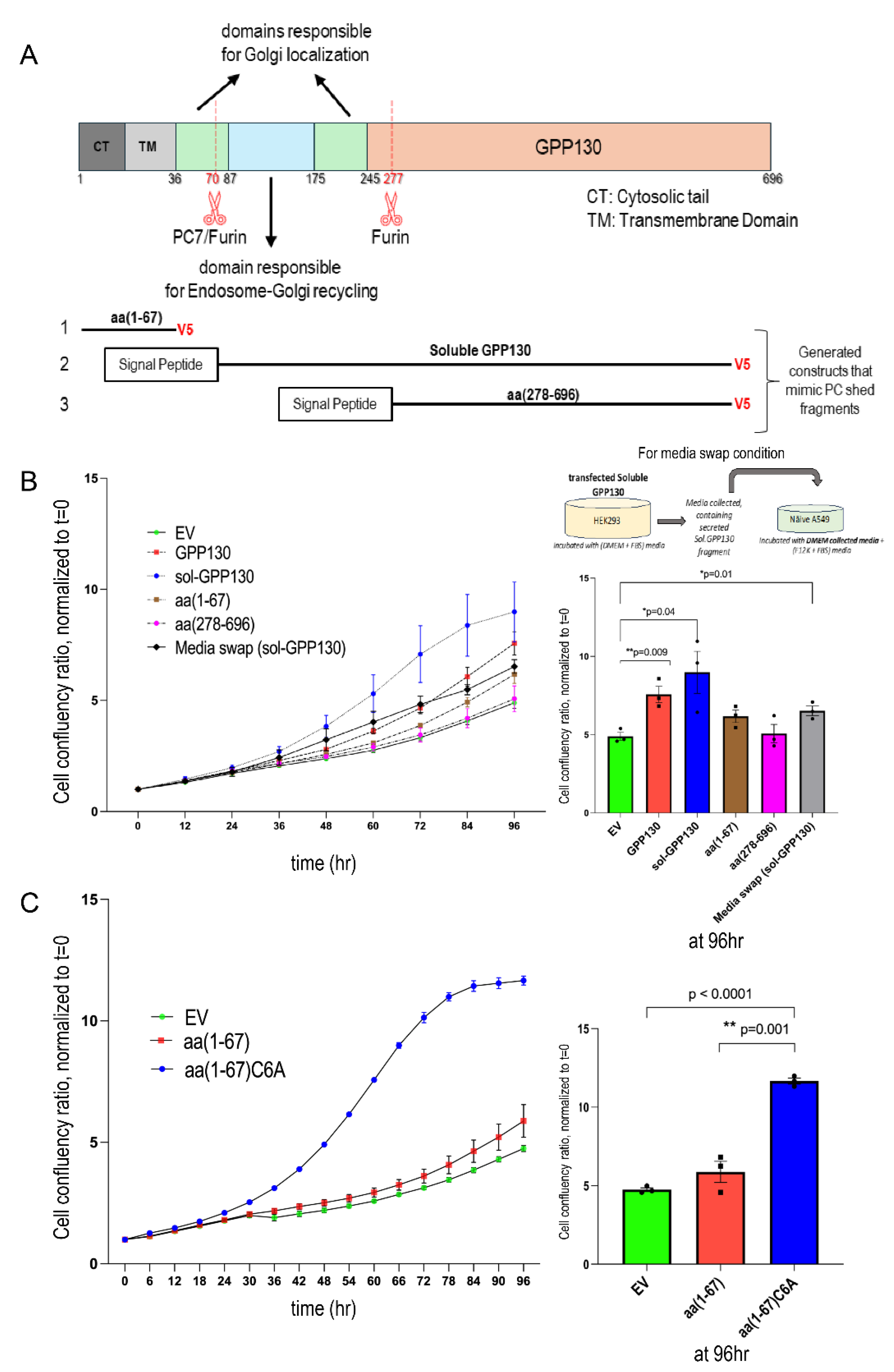

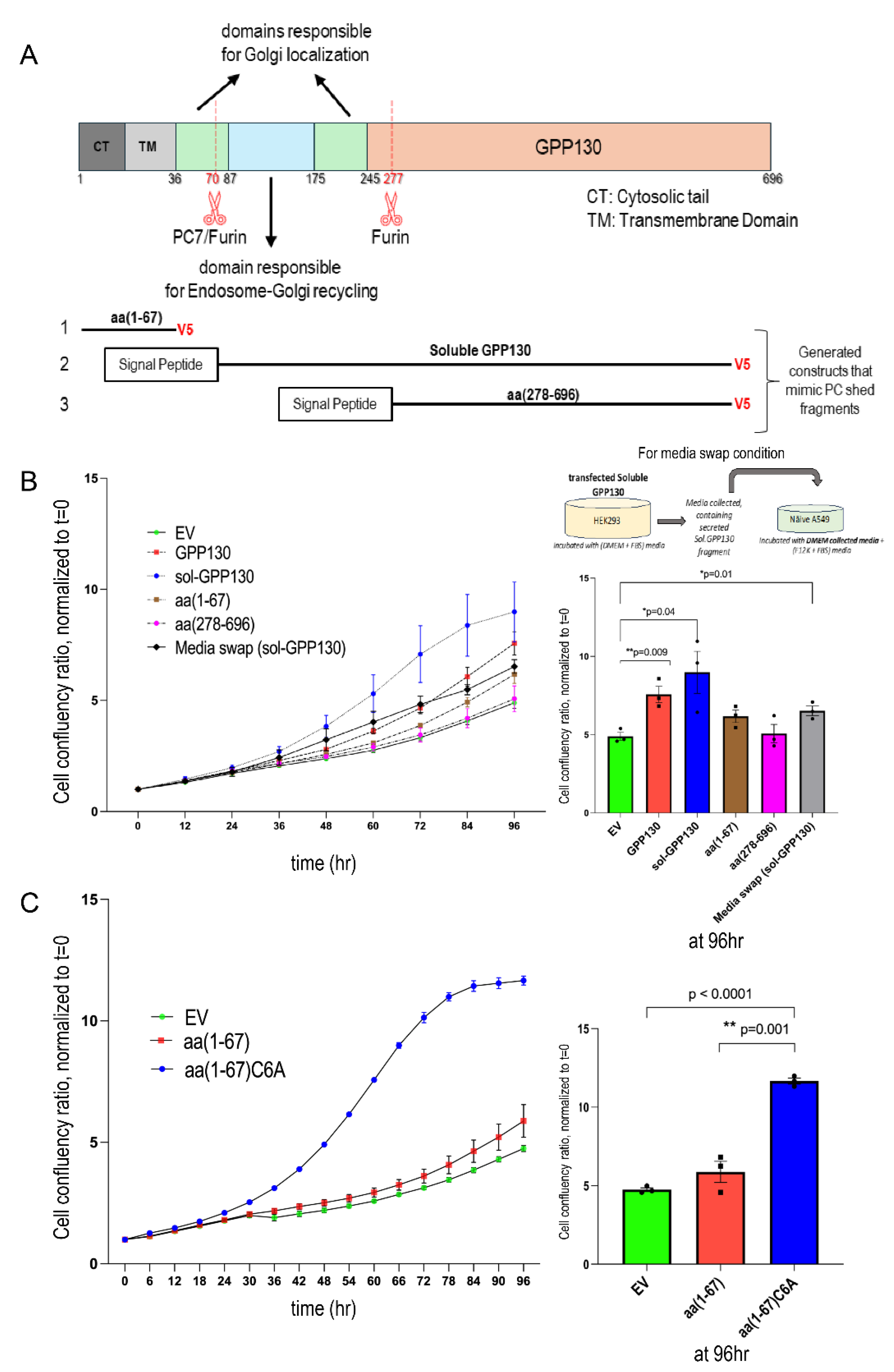

Structure-function studies demonstrated that two domains in GPP130 regulate its pro-proliferative activity: (1) The N-terminal domain aa(1-67), in which the prevention of the likely reversible Cys

6-palmitoylation aa(1-67)C6A [

40] of GPP130 [

41] significantly enhances cellular growth (

Figure 6C); and (2) the N-terminal domain of the secreted shed GPP130 at S1 [aa (71-696)] (

Figure 6B) that encompasses domains responsible for endosome to Golgi recycling and TGN localization (

Figure 6A). Since this fragment seems to enhance cellular proliferation upon its incubation with naïve A549 cells (

Figure 6B), future studies may identify a putative cell-surface binding partner/receptor and its subsequent signaling pathway. Interestingly, sortilin has been shown to interact with the luminal domain of GPP130 [

42], it is plausible that shed GPP130 may bind sortilin at the cell surface to that triggers a cascade of events resulting in higher cellular proliferation [

43].

By comparison, CASC4 was also shown to be shed at a single site by Furin and PC7, and the generated N-terminal transmembrane fragment (aa 1-66) also enhances cellular migration and invasion [

4]. Thus, both GPP130 and CASC4 have N-terminal membrane-bound domains that enhance cellular proliferation and/or migration, which may be implicated in cancer progression. Indeed, the overexpression of CASC4 or the efficiently shed CASC4-5REL variant in A549 cells led to increased proliferation compared to EV (

Figure 7). The presence of multiple basic residues in the cytosolic tails of both GPP130 and CASC4 suggests that they may act as nuclear localization signals that could sort them to the nucleus [

44] if released into the cytosol following a putative g-secretase cleavage within their transmembrane domain, as observed with various transmembrane proteins [

45]. Previous studies have shown that the dysregulation of palmitoylation is indeed critically involved in many cancers [

46]. This dysregulation, combined with GPP130 shedding via PC7/Furin, may explain the proliferative effects of GPP130.

In conclusion, we showed for the first time that GPP130 is cleaved by PC7 and Furin and that this shedding could lead to the release of an ectodomain fragment, which may enhance cell proliferation in a similar fashion to that of another family member protein, GP73 that is highly oncogenic [

47,

48]. The present study sheds light on a poorly characterized Golgi-resident substrate of PC7 and Furin, and future work will help to elucidate its biological roles, binding partners, and how PCs modulate its functions. Our findings highlight the functional significance of the shedding of GPP130 by PC7 and Furin and its effect on the proliferation of human lung carcinoma A549 cells. Our data suggest that PC7 and/or Furin, which are implicated in many cancers via their enzymatic activity [

3,

4,

49], that may also enhance the shedding of novel cancer growth factors such as GPP130 and CASC4. Future studies should validate the functional importance and consequences of their silencing/inhibition in the treatment of aggressive cancers and their associated metastasis.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plasmids

Human GPP130 WT, GPP130 aa(1-67), GPP130 aa(278-696), soluble GPP130 (Signal peptide - aa (71-696)- lacking the transmembrane domain; ΔTM), GPP130 SP-aa(71-277), full-length human PC7, full-length human Furin cDNAs were cloned V5 tag at the C-terminus, into pIRES-EGFP vector (Clontech). Site-directed mutagenesis was used to generate G2A, C6A, G2AC6A, R70A, GPP130 (RSR70LEK) variant RRRR71EL (called 4REL) to generate a Furin/PC7 optimized cleavage site, and a PC uncleavable mutant, GPP130 (R70AR277A).

4.2. Cell Culture, Transfections, and Cell Treatments

A549 cells were grown in Kaighn’s Modification of Ham’s F-12 Medium (F12K, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (Wisent) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Sigma). HEK293 and HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Invitrogen) with 10% FBS, Invitrogen. SKOV3 cells were grown in McCoy’s 5A medium with 10% FBS. All cells were maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2. HEK293 cells were co-transfected with equimolar quantities of each plasmid using Jetprime Polyplus, whereas A549 cells were transfected with equimolar quantities of each plasmid using FuGene HD, using the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.3. Cell Treatments

At 24 hours post-transfection, cells were washed in serum-free medium followed by an additional 24 hours with serum-free media (SFM) alone or SFM media with 20 μM NH4Cl or 10 μM D6R, 75 μM dec-RVKR-cm.

4.4. Immunofluorescence

Cells were grown on coverslips and fixed with warm paraformaldehyde (4%) for 10 min and permeabilized with PBS 1X + Triton 0.1%. Following permeabilization or PBS incubation, cells were stained for primary antibodies: anti-EEA1 (Abcam), anti-Golgin 97 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-LDLR (R&D Systems), anti-calnexin (Abcam), or anti-V5 (Invitrogen) for 1 hour followed by incubation with fluorescent corresponding secondary antibodies for 1 hour in the dark. Coverslips were then mounted on a microscope slide (Fisher Scientific) with ProLong Gold antifade with DAPI (Invitrogen) to stain the nucleus. For cell surface labeling, the permeabilization step was skipped, keeping the rest of the protocol as mentioned above.

4.5. Western Blot Analysis and Antibodies Used

Proteins were extracted in RIPA buffer with cocktails of protease inhibitors (Roche). Bradford assay was used to evaluate the protein concentrations. Proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. The following primary and secondary antibodies were used to incubate the membrane: Mouse anti-V5 (1:5000, Invitrogen), rabbit anti-β-actin (1:5,000, Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-αtubulin (1:10000, Proteintech) or horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated mAb V5 (1:10,000, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-PC7 (1:1000; cell signaling technology) and anti-Furin (1:5,000 ThermoFisher). Quantifications were done using the ChemiDoc imaging system (Biorad).

4.6. Cell Proliferation Analysis

For cell proliferation assays, cells were seeded into 24 well plates (Greiner) at low cellular density (15,000 cells/well) and placed into the Incucyte imager for up to 96 hours. Images were taken by the machine at intervals of 12 hours to generate cellular density (% of confluence), and results were graphed over time. Each experiment was performed at least 3 times, and subsequent statistical analysis was done, wherein ns means p > 0.05, * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01 and *** p ≤ 0.001. Normality and equality of variance of the data were checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test and F-test, respectively. The differences between groups were tested using parametric unpaired Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction for unequal variance or nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test if required.

Author Contributions

P.P., S.D. and N.G.S.; methodology, P.P, S.D., A.E., and V.S.; data curation, P.P., V.S. and N.G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.P., V.S. and N.G.S.; visualization, P.P, S.D., A.E., V.S. and N.G.S; supervision, N.G.S.; project administration, N.G.S.; funding acquisition, N.G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

PC7 and Furin cleave GPP130. A) A schematic explaining the identification of three PC7 substrates using mass spectrometry analysis. B) Analysis of genetic alterations in the GOLM2 gene (protein product: CASC4) and GOLIM4 (protein product: GPP130) using cBioPortal data. The figure was plotted using the cBioPortal website and depicts the frequency and type of genetic alterations for the two genes. C) Schematic representation of human Golgi Phosphoprotein of 130 kDa (GPP130) protein. Depicted are the cytosolic tail (CT), the transmembrane domain (TM), the luminal domain, and the C-terminal V5-tag. The blue circle depicts a potential N-glycosylation site. D) Western blot analysis of cell lysates and media from HEK293 cells expressing GPP130-V5 with either pIRES-empty vector (EV) or human PC7 [n=3]. E) Western blot analysis of cell lysates and media from HEK293 cells expressing GPP130-V5 with all the basic aa PCs or pIRES-empty vectors [n=3]. Images shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 1.

PC7 and Furin cleave GPP130. A) A schematic explaining the identification of three PC7 substrates using mass spectrometry analysis. B) Analysis of genetic alterations in the GOLM2 gene (protein product: CASC4) and GOLIM4 (protein product: GPP130) using cBioPortal data. The figure was plotted using the cBioPortal website and depicts the frequency and type of genetic alterations for the two genes. C) Schematic representation of human Golgi Phosphoprotein of 130 kDa (GPP130) protein. Depicted are the cytosolic tail (CT), the transmembrane domain (TM), the luminal domain, and the C-terminal V5-tag. The blue circle depicts a potential N-glycosylation site. D) Western blot analysis of cell lysates and media from HEK293 cells expressing GPP130-V5 with either pIRES-empty vector (EV) or human PC7 [n=3]. E) Western blot analysis of cell lysates and media from HEK293 cells expressing GPP130-V5 with all the basic aa PCs or pIRES-empty vectors [n=3]. Images shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 2.

GPP130 is localized primarily in the TGN when overexpressed in HeLa cells. Immunofluorescence analysis of permeabilized HeLa cells overexpressing human GPP130-V5 colocalizing (white arrows) with TGN marker (Golgin-97), early endosome marker (EEA1), endoplasmic reticulum marker (calnexin) and plasma membrane marker low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) (non-permeabilized condition) [n=3]. Images shown are representative of three independent experiments. Scale: 10µm.

Figure 2.

GPP130 is localized primarily in the TGN when overexpressed in HeLa cells. Immunofluorescence analysis of permeabilized HeLa cells overexpressing human GPP130-V5 colocalizing (white arrows) with TGN marker (Golgin-97), early endosome marker (EEA1), endoplasmic reticulum marker (calnexin) and plasma membrane marker low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) (non-permeabilized condition) [n=3]. Images shown are representative of three independent experiments. Scale: 10µm.

Figure 3.

GPP130 cleavage by PC7 and Furin occurs at HRSR70↓LE and HRSRLEK73↓, respectively, and solely at KPTR277↓EV for Furin. A) Schematic representation of GPP130 cleavage motifs and released fragments. B) Western blot analysis of cell lysates and media from HEK293 cells overexpressing GPP130-V5 WT and different point mutations (H67A, R68A, R70A, K73A, R148A, K274A, or R277A), with human PC7, human Furin, or pIRES-empty vector (EV) [n=3]. C) Western blot analysis and quantifications of cell lysates and media from HEK293 cells overexpressing GPP130-V5 WT, GPP130 4REL (an optimally cleaved mutant), or GPP130 R70A (a PC non-cleavable mutant) co-expressed with human PC7, human Furin, or pIRES-empty vector [n=3]. Images shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 3.

GPP130 cleavage by PC7 and Furin occurs at HRSR70↓LE and HRSRLEK73↓, respectively, and solely at KPTR277↓EV for Furin. A) Schematic representation of GPP130 cleavage motifs and released fragments. B) Western blot analysis of cell lysates and media from HEK293 cells overexpressing GPP130-V5 WT and different point mutations (H67A, R68A, R70A, K73A, R148A, K274A, or R277A), with human PC7, human Furin, or pIRES-empty vector (EV) [n=3]. C) Western blot analysis and quantifications of cell lysates and media from HEK293 cells overexpressing GPP130-V5 WT, GPP130 4REL (an optimally cleaved mutant), or GPP130 R70A (a PC non-cleavable mutant) co-expressed with human PC7, human Furin, or pIRES-empty vector [n=3]. Images shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 4.

GPP130 is cleaved in a post-ER acidic compartment by PC7 and Furin. (A, B) Western blot analysis of cell lysates and media from HEK293 cells overexpressing GPP130-V5 WT and human PC7, human Furin, or with pIRES-empty vector (vector) in the presence or absence of BFA (A) or (B) Sar1p(H79G) variant [n=3]. Notice the secretion of the s1-fragment by PC7 and Furin and the S2 fragment by Furin. C, D, E) Western blot analysis and quantifications of cell lysates and media from HEK293 cells overexpressing GPP130-V5 WT, and human PC7, human Furin or with pIRES-empty vector (vector) in the presence or absence of NH4Cl (C), D6R (D) or dec-RVKR-cmk (RVKR) (E) [n=3]. The red boxes depict the shedding of the S1 and S2 fragments in the presence of the inhibitors. Images shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 4.

GPP130 is cleaved in a post-ER acidic compartment by PC7 and Furin. (A, B) Western blot analysis of cell lysates and media from HEK293 cells overexpressing GPP130-V5 WT and human PC7, human Furin, or with pIRES-empty vector (vector) in the presence or absence of BFA (A) or (B) Sar1p(H79G) variant [n=3]. Notice the secretion of the s1-fragment by PC7 and Furin and the S2 fragment by Furin. C, D, E) Western blot analysis and quantifications of cell lysates and media from HEK293 cells overexpressing GPP130-V5 WT, and human PC7, human Furin or with pIRES-empty vector (vector) in the presence or absence of NH4Cl (C), D6R (D) or dec-RVKR-cmk (RVKR) (E) [n=3]. The red boxes depict the shedding of the S1 and S2 fragments in the presence of the inhibitors. Images shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 5.

GPP130 enhances the proliferation of HeLa, SKOV3, and A549 cells. A, B, C) Incucyte analysis of the cellular proliferation of human HeLa (A), SKOV3 (B), and A549 (C) cells overexpressing GPP130. The data are normalized to day 0, and proliferation is followed by 96h [n=3]. D) qPCR analysis of the mRNA levels of PCSK7, Furin, and GPP130 in naive A549 cells, normalized to the housekeeping gene human TATA-binding protein (hTBP) [n=3]. E) Incucyte analysis of the cellular proliferation of A549 cells lacking GPP130 (siGPP130) [n=3]. The efficiency of the siRNA is shown in (E), and the overexpressed levels of GPP130 in A549 cells are shown in (C) [n=3]. The statistically significant results (p<0.05) at the 96h timepoint are depicted. Western blot images shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 5.

GPP130 enhances the proliferation of HeLa, SKOV3, and A549 cells. A, B, C) Incucyte analysis of the cellular proliferation of human HeLa (A), SKOV3 (B), and A549 (C) cells overexpressing GPP130. The data are normalized to day 0, and proliferation is followed by 96h [n=3]. D) qPCR analysis of the mRNA levels of PCSK7, Furin, and GPP130 in naive A549 cells, normalized to the housekeeping gene human TATA-binding protein (hTBP) [n=3]. E) Incucyte analysis of the cellular proliferation of A549 cells lacking GPP130 (siGPP130) [n=3]. The efficiency of the siRNA is shown in (E), and the overexpressed levels of GPP130 in A549 cells are shown in (C) [n=3]. The statistically significant results (p<0.05) at the 96h timepoint are depicted. Western blot images shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 6.

A, B) GPP130 domains implicated in enhancing the proliferation of A549 cells and the paracrine effect of GPP130 shedding. A) Schematic diagram of the various constructs used. B) Incucyte analysis of cellular proliferation of A549 cells overexpressing GPP130-FL, soluble GPP130, the N-terminal fragment (aa 1-67) generated by S1-cleavage and the C-terminal product of the S2-cleavage (aa 278-696) or with pIRES-empty vector (EV) [n=3]. Additionally, cellular proliferation of naïve A549 cells incubated with the conditioned media of HEK293 over expressing sol-GPP130 compared to A549 cells overexpressing soluble GPP130 or the pIRES-empty vector (EV) is also depicted (experimental design shown in the inlet). C) Palmitoylation of GPP130 regulates the proliferation of A549 cells. Incucyte analysis of cellular proliferation of naïve A549 cells overexpressing soluble GPP130 aa(1-67) compared to its non-palmitoylated C6A mutant or the pIRES-empty vector (EV) [n=3]. The data are normalized to day 0 and proliferation is followed for 96h. The data are normalized to day 0 and proliferation is followed for 96h. The statistically significant results (*; p<0.05, **; p<0.005) at the 96h timepoint are depicted as separate bar graphs.

Figure 6.

A, B) GPP130 domains implicated in enhancing the proliferation of A549 cells and the paracrine effect of GPP130 shedding. A) Schematic diagram of the various constructs used. B) Incucyte analysis of cellular proliferation of A549 cells overexpressing GPP130-FL, soluble GPP130, the N-terminal fragment (aa 1-67) generated by S1-cleavage and the C-terminal product of the S2-cleavage (aa 278-696) or with pIRES-empty vector (EV) [n=3]. Additionally, cellular proliferation of naïve A549 cells incubated with the conditioned media of HEK293 over expressing sol-GPP130 compared to A549 cells overexpressing soluble GPP130 or the pIRES-empty vector (EV) is also depicted (experimental design shown in the inlet). C) Palmitoylation of GPP130 regulates the proliferation of A549 cells. Incucyte analysis of cellular proliferation of naïve A549 cells overexpressing soluble GPP130 aa(1-67) compared to its non-palmitoylated C6A mutant or the pIRES-empty vector (EV) [n=3]. The data are normalized to day 0 and proliferation is followed for 96h. The data are normalized to day 0 and proliferation is followed for 96h. The statistically significant results (*; p<0.05, **; p<0.005) at the 96h timepoint are depicted as separate bar graphs.

Figure 7.

Shedding of GPP130 and CASC4 enhances the proliferation of A549 cells. Incucyte analysis of cellular proliferation of A549 cells overexpressing pIRES-empty vector (EV) or WT GPP130, GPP130-R70A-R277A, GPP130-4REL, WT CASC4, CASC4-5REL, GPP130-4REL + CASC4-5REL. The data are normalized to day 0 and proliferation is followed for 96h. The statistically significant results (*; p<0.05, **; p<0.005) at the 96h timepoint are depicted as separate bar graphs [n=3].

Figure 7.

Shedding of GPP130 and CASC4 enhances the proliferation of A549 cells. Incucyte analysis of cellular proliferation of A549 cells overexpressing pIRES-empty vector (EV) or WT GPP130, GPP130-R70A-R277A, GPP130-4REL, WT CASC4, CASC4-5REL, GPP130-4REL + CASC4-5REL. The data are normalized to day 0 and proliferation is followed for 96h. The statistically significant results (*; p<0.05, **; p<0.005) at the 96h timepoint are depicted as separate bar graphs [n=3].