Submitted:

14 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Data Acquisition

2.2. piRNA Annotation and Reference Preparation

2.3. Sequence Alignment and Read Counting

2.4. Differential Expression Analysis

2.5. Data Visualization

3. Results

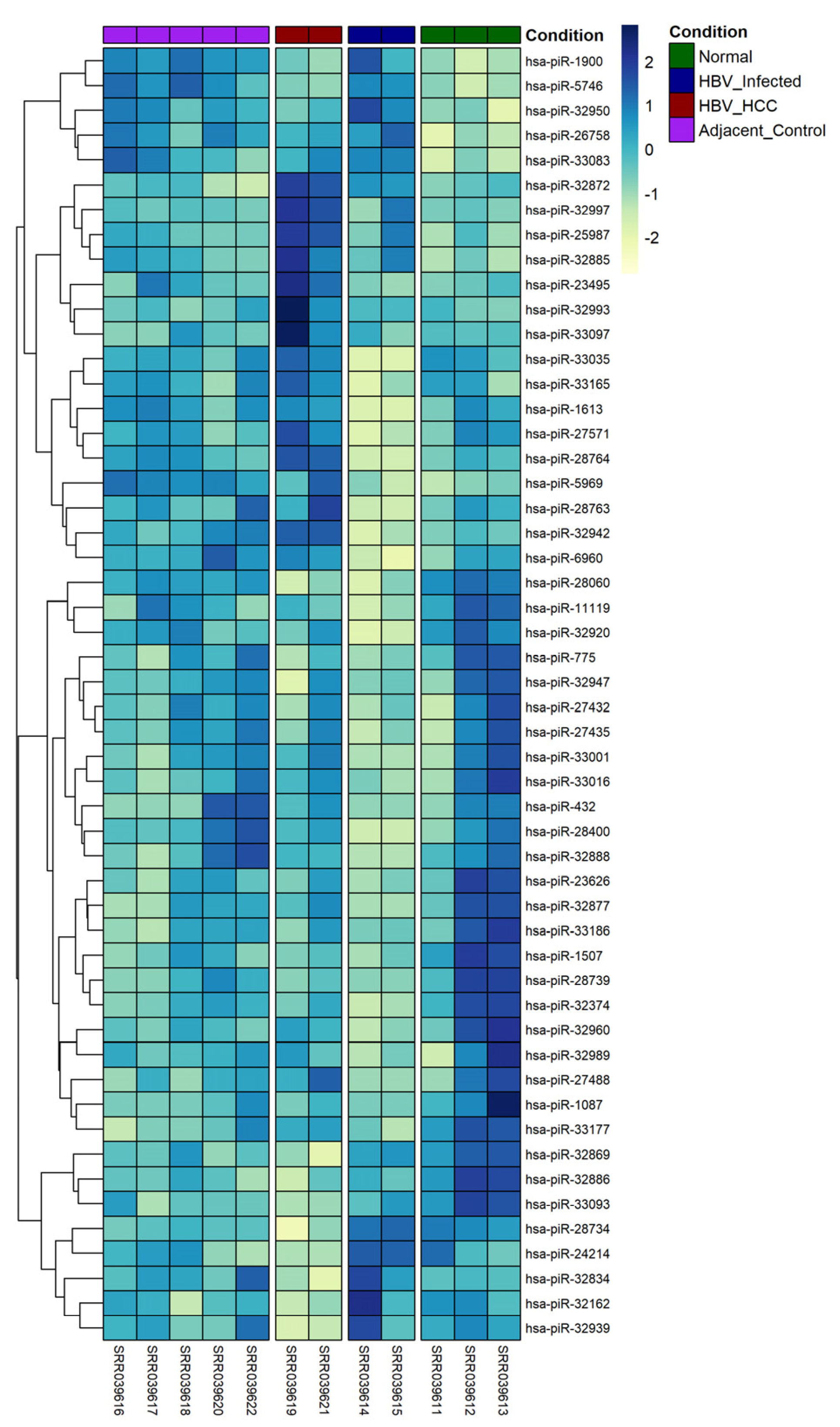

3.1. Overview of Differentially Expressed piRNAs

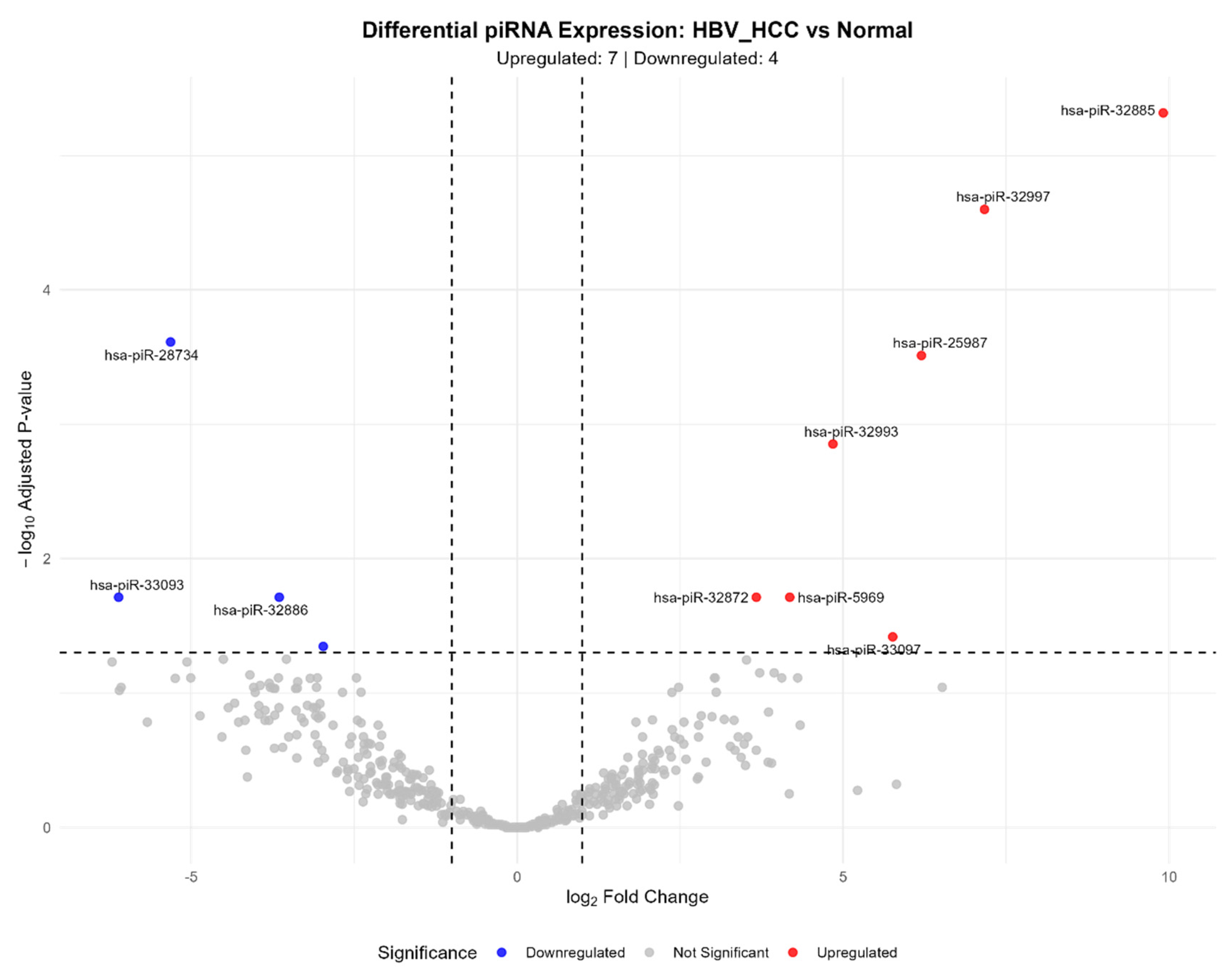

3.2. HBV-Related HCC vs. Normal Liver Comparison

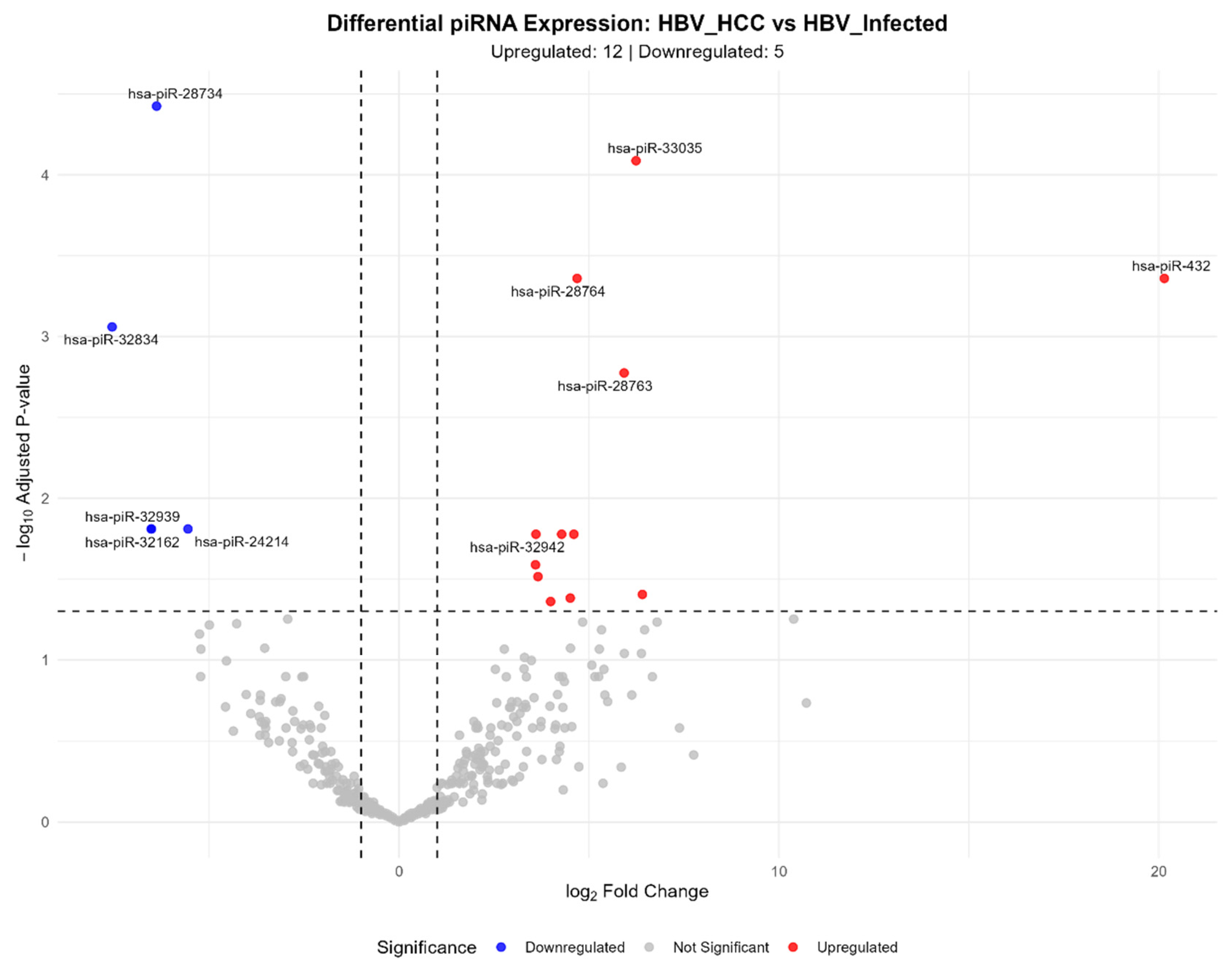

3.3. HBV-Related HCC vs. HBV-Infected Liver Comparison

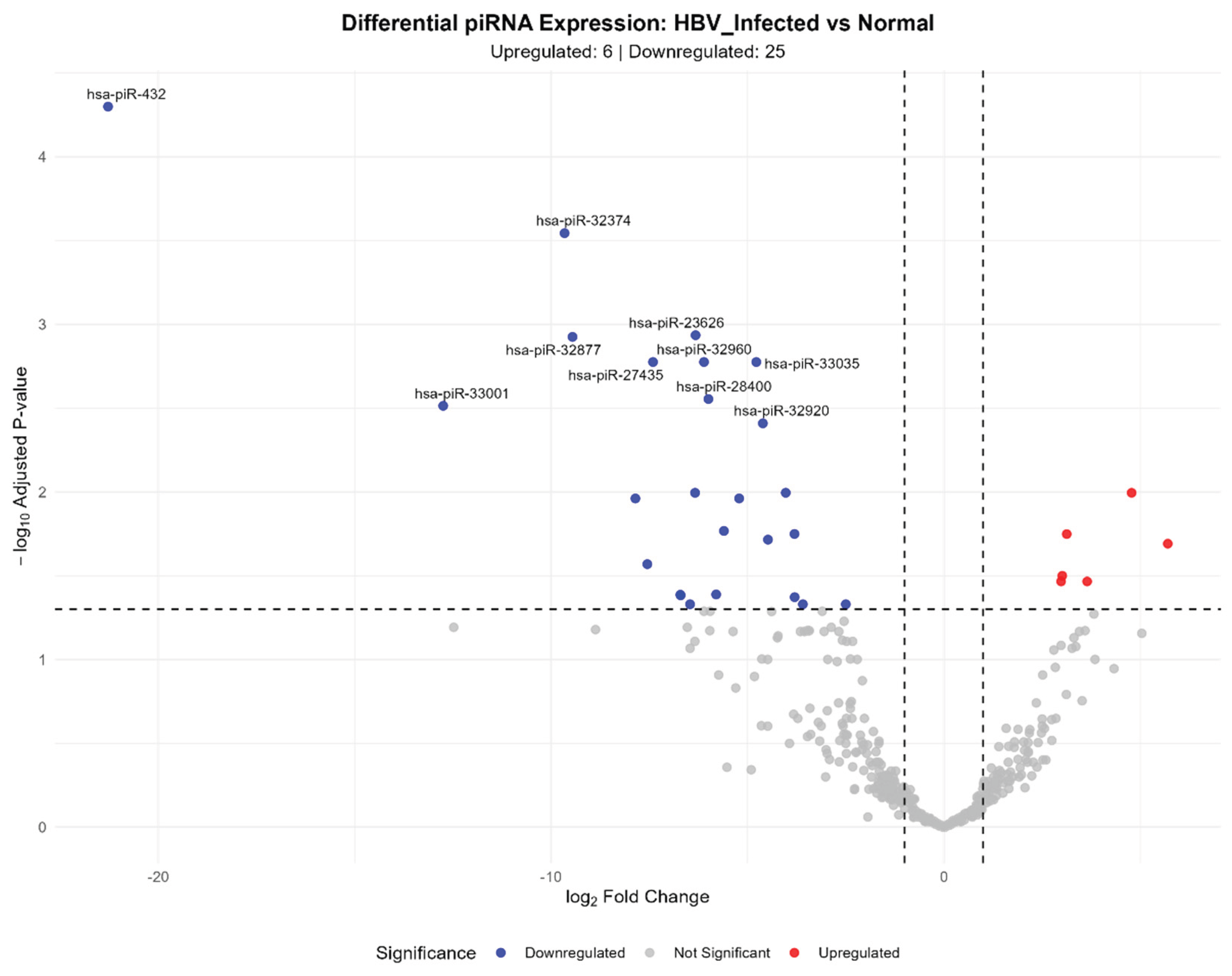

3.4. HBV-Infected vs. Normal Liver Comparison

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Declaration of Generative AI Use

Informed Consent and Patient Details

Clinical Trials

Data Statement

Declaration of Competing Interests

References

- Li, Q.; Ding, C.; Cao, M.; Yang, F.; Yan, X.; He, S.; Cao, M.; Zhang, S.; Teng, Y.; Tan, N.; et al. Global epidemiology of liver cancer 2022: An emphasis on geographic disparities. Chin. Med J. 2024, 137, 2334–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebbi, A.; Lorestani, N.; Tahamtan, A.; Kargar, N.L.; Tabarraei, A. An Overview of Hepatitis B Virus Surface Antigen Secretion Inhibitors. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, M.; Salavatiha, Z.; Gogoi, U.; Mohebbi, A. An overview of anti-Hepatitis B virus flavonoids and their mechanisms of action. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1356003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, S. ; A, S. Novel biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance: has the future arrived? Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2014, 3, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Xiang, X.; Feng, B.; Zhou, H.; Wang, T.; Chu, X.; Wang, R. Targeting Long Non-Coding RNAs in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Progress and Prospects. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, L.-X.; Wang, Z.-C.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Ling, Y.-Z.; Wang, F.; Feng, X.; et al. Exploring non-coding RNA mechanisms in hepatocellular carcinoma: implications for therapy and prognosis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1400744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Xu, Q.; Ni, C.; Ye, S.; Xu, X.; Hu, X.; Jiang, J.; Hong, Y.; Huang, D.; Yang, L. Prospects of Noncoding RNAs in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Clark, D.; Mao, L. Novel dimensions of piRNAs in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013, 336, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Yang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Zhuang, J.; Han, S. Biological significance of piRNA in liver cancer: a review. Biomarkers 2020, 25, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, W.; Bian, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Gou, A.; Zhang, W.; Fu, K.; Shi, W. Emerging roles of piRNAs in cancer: challenges and prospects. Aging 2019, 11, 9932–9946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, A.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Qi, Q.; Wu, Y.; Dong, P.; Chen, L.; Wang, F. PIWI-Interacting RNAs (piRNAs): Promising Applications as Emerging Biomarkers for Digestive System Cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 848105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Borja, E.; Siegl, F.; Mateu, R.; Slaby, O.; Sedo, A.; Busek, P.; Sana, J. Critical appraisal of the piRNA-PIWI axis in cancer and cancer stem cells. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dou, M.; Song, X.; Dong, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Tao, J.; Li, W.; Yin, X.; Xu, W. The emerging role of the piRNA/piwi complex in cancer. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, P.T.-Y.; Qin, H.; Ching, A.K.-K.; Lai, K.P.; Na Co, N.; He, M.; Lung, R.W.-M.; Chan, A.W.-H.; Chan, T.-F.; Wong, N. Deep sequencing of small RNA transcriptome reveals novel non-coding RNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2013, 58, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koduru, S.V.; Leberfinger, A.N.; Kawasawa, Y.I.; Mahajan, M.; Gusani, N.J.; Sanyal, A.J.; Ravnic, D.J. Non-coding RNAs in Various Stages of Liver Disease Leading to Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Differential Expression of miRNAs, piRNAs, lncRNAs, circRNAs, and sno/mt-RNAs. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, F.; Rinaldi, A.; Marchese, G.; Coviello, E.; Sellitto, A.; Cordella, A.; Giurato, G.; Nassa, G.; Ravo, M.; Tarallo, R.; et al. Specific patterns of PIWI-interacting small noncoding RNA expression in dysplastic liver nodules and hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 54650–54661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rui, T.; Wang, K.; Xiang, A.; Guo, J.; Tang, N.; Jin, X.; Lin, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X. Serum Exosome-Derived piRNAs Could Be Promising Biomarkers for HCC Diagnosis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, ume 18, 1989–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y. The potential emerging role of piRNA/PIWI complex in virus infection. Virus Genes 2024, 60, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. feature Counts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. I. Love, W. Huber, S. Anders, Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Lin, L.; Zhou, W.; Wang, Z.; Ding, G.; Dong, Q.; Qin, L.; Wu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. Identification of miRNomes in Human Liver and Hepatocellular Carcinoma Reveals miR-199a/b-3p as Therapeutic Target for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2011, 19, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Piuco, P.A.F. R. Piuco, P.A.F. Galante, piRNAdb: A piwi-interacting RNA database, (n.d.). [CrossRef]

- Kondratov, K.A.; Artamonov, A.A.; Nikitin, Y.V.; Velmiskina, A.A.; Mikhailovskii, V.Y.; Mosenko, S.V.; Polkovnikova, I.A.; Asinovskaya, A.Y.; Apalko, S.V.; Sushentseva, N.N.; et al. Revealing differential expression patterns of piRNA in FACS blood cells of SARS-CoV−2 infected patients. BMC Med Genom. 2024, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimniyazova, A.; Yurikova, O.; Pyrkova, A.; Rakhmetullina, A.; Niyazova, T.; Ryskulova, A.-G.; Ivashchenko, A. In Silico Study of piRNA Interactions with the SARS-CoV-2 Genome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhmetullina, A.; Akimniyazova, A.; Niyazova, T.; Pyrkova, A.; Kamenova, S.; Kondybayeva, A.; Ryskulova, A.-G.; Ivashchenko, A.; Zielenkiewicz, P. Endogenous piRNAs Can Interact with the Omicron Variant of the SARS-CoV-2 Genome. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 2950–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, H.; Gu, W. Small RNA Plays Important Roles in Virus–Host Interactions. Viruses 2020, 12, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.W.; Wang, W.; Zamore, P.D.; Weng, Z. piPipes: a set of pipelines for piRNA and transposon analysis via small RNA-seq, RNA-seq, degradome- and CAGE-seq, ChIP-seq and genomic DNA sequencing. Bioinformatics 2014, 31, 593–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, P.Z.; Yang, Y.; Chen, E.B.; Zhu, G.Q.; Wang, B.; Dai, Z. [Differential expressions analysis of piwi-interacting RNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma]. . 2018, 26, 842–846. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeng, G.; Zhang, D.; Liu, X.; Kang, Q.; Fu, Y.; Tang, B.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, G.; He, D. Co-expression of Piwil2/Piwil4 in nucleus indicates poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 8, 4607–4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| piRNA_ID | baseMean | log2FoldChange | p-value | padj | Sequence |

| hsa-piR-32885 | 247.62 | 9.91 | 1.11e-08 | 4.81e-06 | CACCAGTGTGAGTTCTACCATTGCCAAA |

| hsa-piR-32997 | 101.21 | 7.17 | 1.16e-07 | 2.51e-05 | TCACAGTGAATTCTACCAGTGCCATA |

| hsa-piR-25987 | 138.90 | 6.20 | 2.85e-06 | 3.08e-04 | TTTGGCAATGGTAGAACTCACACTGGTGAGGT |

| hsa-piR-32993 | 284.37 | 4.84 | 1.62e-05 | 1.40e-03 | TAGAGGAGCCTGTTCTGTAATCGATAAACC |

| hsa-piR-5969 | 57.80 | 4.18 | 4.04e-04 | 1.94e-02 | TCCGTAGTGTAGTGGTTATCACGTTCGCCT |

| hsa-piR-32872 | 109.14 | 3.67 | 3.69e-04 | 1.94e-02 | AGTCTCAGTTTCCTCTGCAAACAGTT |

| hsa-piR-33097 | 11.79 | 5.76 | 8.85e-04 | 3.82e-02 | CAGCTGATGATGATAATATTGCCTGAAGA |

| hsa-piR-32869 | 1458.61 | -2.97 | 1.15e-03 | 4.51e-02 | AGGGAGATGAAGAGGACAGTGACTGAGAGAC |

| hsa-piR-32886 | 2045.14 | -3.65 | 3.51e-04 | 1.94e-02 | CACCATGATGGAACTGAGGATCTGAGGAA |

| hsa-piR-28734 | 198.73 | -5.32 | 1.69e-06 | 2.44e-04 | GTTCACTGATGAGAGCATTGTTCTGAGCCA |

| hsa-piR-33093 | 9.71 | -6.11 | 3.69e-04 | 1.94e-02 | CAGCAAATGATGTGAGAGATTCTGCTGATA |

| piRNA_ID | baseMean | log2FoldChange | p-value | padj | Sequence |

| hsa-piR-432 | 58.19 | 20.14 | 4.22e-06 | 4.36e-04 | ACAGTAGCATTGGTGGTTCAGTGGTA |

| hsa-piR-1613 | 11.85 | 6.40 | 1.52e-03 | 3.94e-02 | ATAGGTTTGGTCCTAGCCTTTCTATT |

| hsa-piR-33035 | 123.76 | 6.24 | 4.18e-07 | 8.16e-05 | TGGTTCGTCCAAGTGCACTTTCCAGT |

| hsa-piR-28763 | 778.02 | 5.92 | 2.58e-05 | 1.68e-03 | GTTTAGACGGGCTCACATCACCCCATAAACA |

| hsa-piR-28764 | 718.99 | 4.68 | 4.48e-06 | 4.36e-04 | GTTTCCGTAGTGTAGTGGTCATCACGTTCGC |

| hsa-piR-23495 | 15.51 | 4.51 | 1.70e-03 | 4.15e-02 | CGTAGTGTAGTGGTCATCACGTTCGCCT |

| hsa-piR-32993 | 284.37 | 4.28 | 4.98e-04 | 1.67e-02 | TAGAGGAGCCTGTTCTGTAATCGATAAACC |

| hsa-piR-5969 | 57.80 | 4.60 | 5.09e-04 | 1.67e-02 | TCCGTAGTGTAGTGGTTATCACGTTCGCCT |

| hsa-piR-32885 | 247.62 | 5.70 | 1.04e-03 | 2.03e-02 | CACCAGTGTGAGTTCTACCATTGCCAAA |

| hsa-piR-28734 | 198.73 | -6.38 | 9.62e-08 | 3.75e-05 | GTTCACTGATGAGAGCATTGTTCTGAGCCA |

| hsa-piR-32162 | 19.55 | -6.52 | 2.88e-04 | 1.55e-02 | CACAATGCTGACACTCAAACTGCTGACA |

| piRNA_ID | baseMean | log2FoldChange | p-value | padj | Sequence |

| hsa-piR-1900 | 1399.71 | 3.13 | 8.22e-04 | 1.78e-02 | ATTGGTGGTTCAGTGGTAGAATTCTCGCC |

| hsa-piR-26758 | 837.01 | 3.01 | 1.78e-03 | 3.16e-02 | GAGGAATGATGACAAGAAAAGGCCGAA |

| hsa-piR-5746 | 669.93 | 2.98 | 2.10e-03 | 3.42e-02 | TCCCTGGTGGTCTAGTGGTTAGGATA |

| hsa-piR-432 | 58.19 | -21.28 | 1.29e-07 | 5.02e-05 | ACAGTAGCATTGGTGGTTCAGTGGTA |

| hsa-piR-33001 | 428.37 | -12.75 | 7.06e-05 | 3.06e-03 | TCATGCTCTATCGACTGAGCTAGCCGGG |

| hsa-piR-32374 | 117.15 | -9.66 | 1.46e-06 | 2.86e-04 | GTCGATGATGATTGGTAAAAGGTCTGA |

| hsa-piR-32877 | 41.49 | -9.46 | 1.22e-05 | 1.19e-03 | ATCAATGATGAAACTAGCCAAATCTGAGC |

| hsa-piR-32888 | 38.81 | -7.85 | 4.20e-04 | 1.09e-02 | CAGAATGCTAACCATTACACGATGGAACC |

| hsa-piR-1087 | 9.69 | -7.55 | 1.45e-03 | 2.69e-02 | AGCCTATGATGGTTAGTTATCCCTGTCTGAAA |

| hsa-piR-27435 | 109176.10 | -7.41 | 2.73e-05 | 1.68e-03 | GCCCGGCTAGCTCAGTCGGTAGAGCATGAGAC |

| hsa-piR-32947 | 249.02 | -5.60 | 7.00e-04 | 1.71e-02 | GCTCAGAAAATACCTTTCAGTCACACATT |

| hsa-piR-32960 | 43.45 | -6.11 | 2.89e-05 | 1.68e-03 | GGTCAATGATGAATGGTAAAAGGTCTGAGT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).