1. Introduction

Precision oncology is the use of precision medicine in oncology. In fact, the development of precision medicine has been primarily driven by the development of precision oncology. Precision oncology is the most studied and widely applied subarea of precision medicine.

Precision oncology refers to the use of broad molecular tumor characterization with the aim of personalized therapeutic management. In simple terms, the goal of precision medicine is to deliver the right cancer treatment to the right patient, at the right dose, at the right time.

The term ‘precision medicine’ first gained prominence after a publication by the US National Research Council in 2011 [

1]. Four years later, precision medicine has become a term that symbolizes the new age of medicine following the launch of the national Precision Medicine Initiative by then President Obama in the United States in 2015 [

2].

However, the use of molecular characterization of an individual patient’s tumor in routine oncologic practice roughly began 20 years ago, especially following the publication of the first draft of the Human Genome Project in 2003. Moreover, the idea and practice of precision medicine/oncology had even earlier origins, beginning in the 1980s and 1990s [

2,

3].

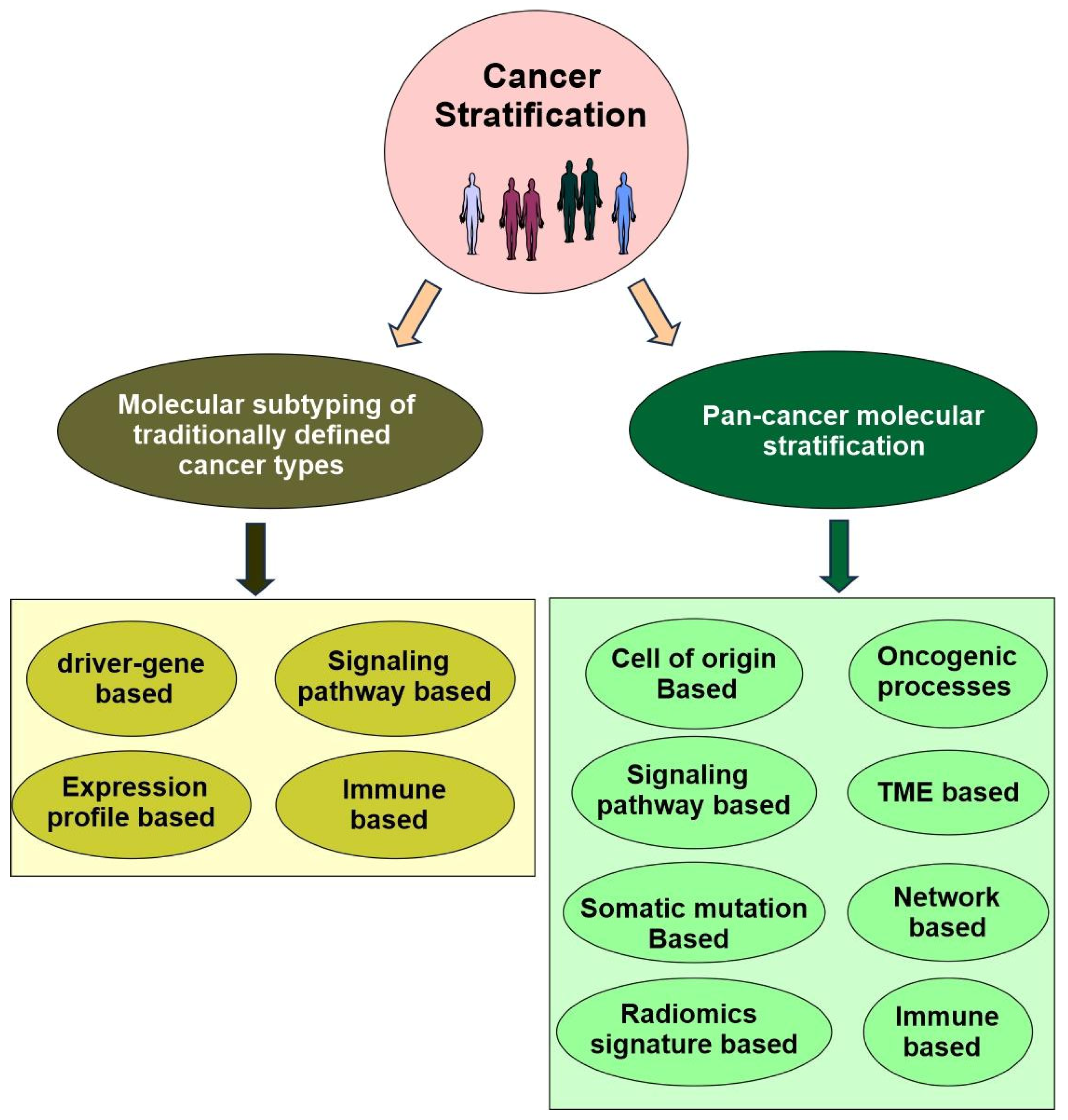

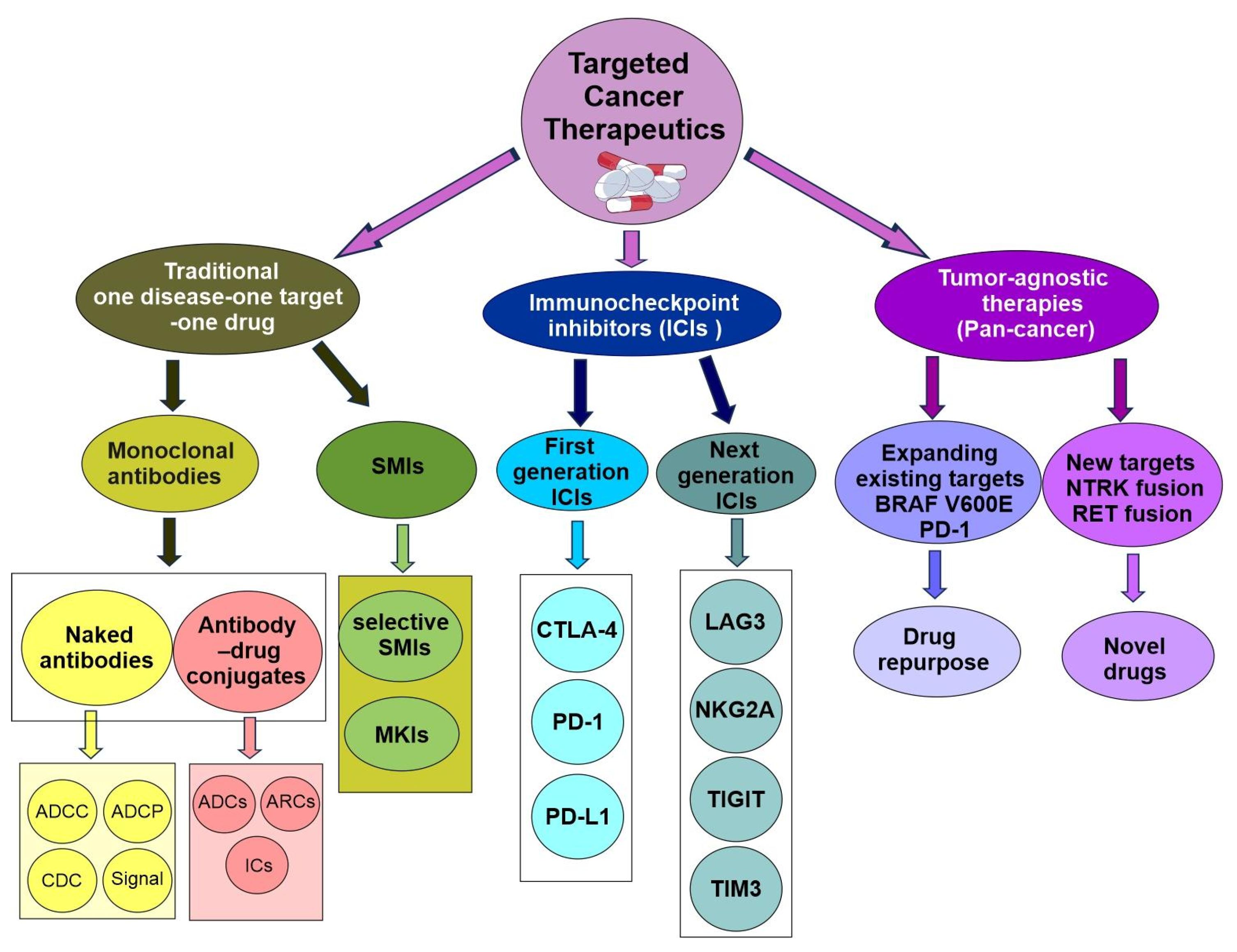

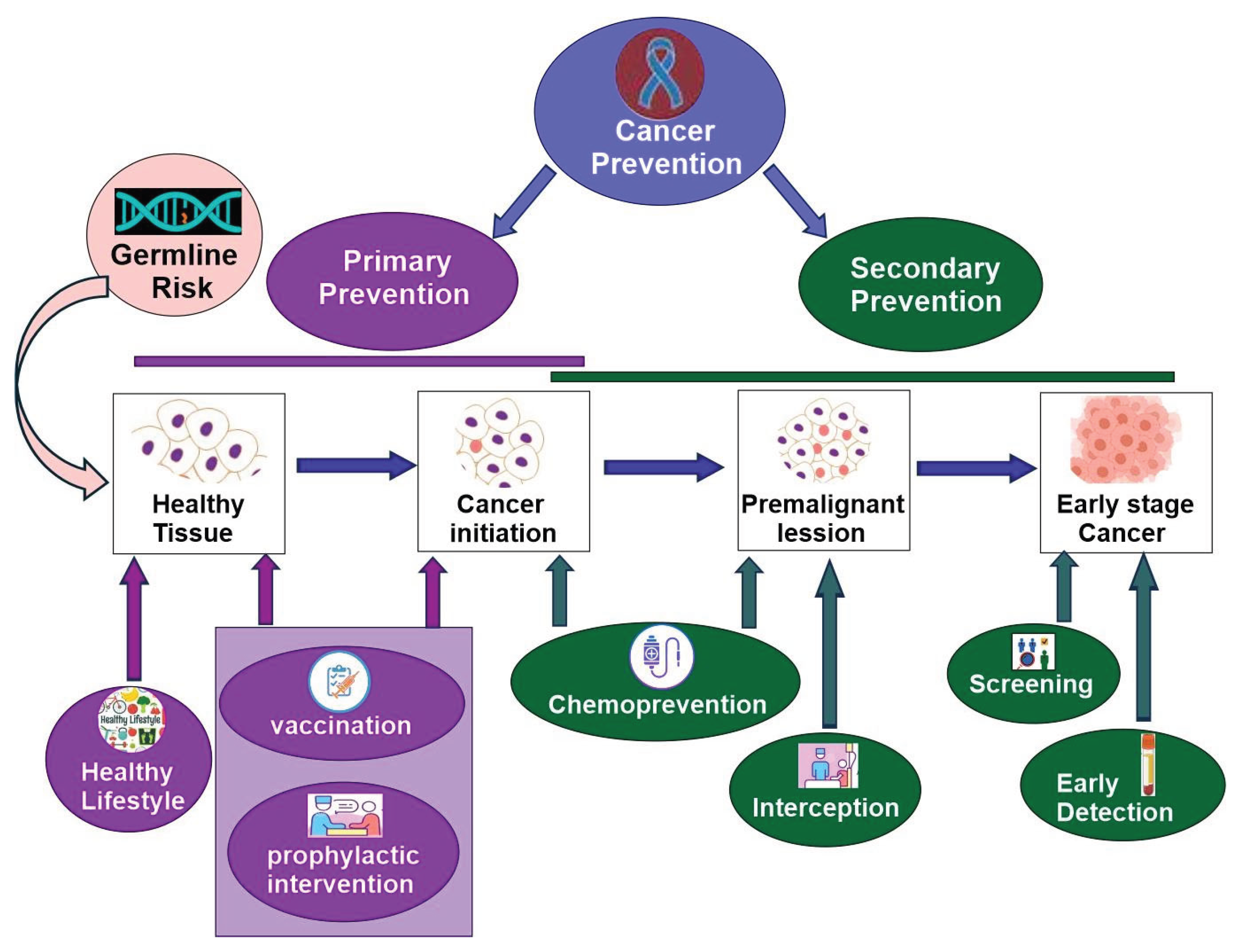

The early development of precision oncology was driven by a desire to move beyond blanket treatments for patients to a more refined, efficient, and patient-centred approach. To achieve this goal, three essential objectives must be met. First, the cancer needs to be stratified into various subtypes. Second, there must be tailored treatment available for each specific subtype. Third, comprehensive molecular profiling of each individual patient must be generated. When all three objectives are met, patients can be individually assigned to a particular cancer subtype and then treated with appropriate tailored therapies [

2]. In addition, early diagnosis is another important element of a successful cancer treatment. This becomes increasingly possible due to the rapid development of modern technology and deeper understanding of cancer biology.

Now, precision oncology has expanded to include modern technology (big data, single-cell spatial multiomics, molecular imaging, liquid biopsy, CRISPR gene editing, stem cells, organoids), a deeper understanding of cancer biology (driver cancer genes, single nucleotide polymorphism, cancer initiation, intratumor heterogeneity, tumor microenvironment ecosystem, pan-cancer), cancer stratification (subtyping of traditionally defined cancer types and pan-cancer re-classification based on shared properties across traditionally defined cancer types), clinical applications (cancer prevention, early detection, diagnosis, targeted therapy, minimal residual disease monitoring, managing drug resistance), lifestyle changes (physical activity, smoking cessation, reduced alcohol consumption, sunscreen), cost management, public policy, and more (

Figure 1) [

2,

4].

In this review, we will focus on the various pillars of precision oncology, with an emphasis on emerging trends, challenges, and future perspectives.

2. Emerging and Maturation of Technologies in Precision Oncology

Advanced emerging technologies have revolutionized cancer research since the completion of the human genome project in the early 21st century and empowered precision oncology. These technologies include, but are not limited to bulk multiomics, single-cell multiomics, spatial multiomics, single-cell spatial multiomics, organoids, induced pluritopical stem cells (iPSCs), CRISPE gene editing, liquid biopsy, molecular imaging, and artificial intelligence (AI) (

Figure 2). These technologies help by providing a snapshot of any biological system of interest at an unprecedented resolution and dimension. Omics is a nomenclature broadly applied to the collective study of molecular characterization and quantification of biological molecules from various subdomains of molecular biology using high-throughput technology. These subdomains include genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, among others [

2].

The fundamental high-throughput technology in omics is Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). NGS sequences millions of DNA fragments at once, producing enormous amounts of molecular data efficiently, quickly, and at a lower cost. It has advanced nearly every area of omics research.

However, these one-dimensional bulk omics struggle with many issues, such as intratumor heterogeneity and tumor microenvironment (TME). Recently developed technologies, including single-cell multiomics, spatial multiomics, and liquid biopsy, have allowed for a much deeper understanding of the novel aspects of tumor biology. In the following sections, we will discuss several cutting-edge technologies that have made important contributions to precision oncology.

2.1. Single-Cell Multiomics

Single-cell sequencings can reveal the specific effect of an individual cellular component. Since the first report of single-cell genome-wide mRNA sequencing in 2009 [

5], various single-cell cell sequencing methods have been developed, including single-cell DNA sequencing for genomics, single-cell DNA methylome sequencing quantifying DNA methylation, single-cell ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing) investigating chromatin accessibility at the single-cell level, single-cell proteomics quantifying the expressed proteome in an individual cell, and single-cell metabolomics [

6,

7].

Single-cell omics technologies offer high-resolution analysis of cellular diversity, overcoming the limitations of bulk methods that mask individual cell differences. These approaches enable the identification of distinct cell types and rare cell populations, as well as dynamic cell states. These techniques offer unprecedented sensitivity and resolution, empowering researchers to reveal the molecular landscape of individual cells [

7].

The emerging trend in single-cell omics is to integrate multimodal omics data within a single-cell to generate a holistic and comprehensive picture of cellular processes. Multimodal omics can help clarify complex cellular interactions, regulatory networks, and molecular mechanisms.

Importantly, the single-cell multiomics approach has revolutionized our ability to dissect cellular mechanisms by allowing for the concurrent measurement of multiple biomolecular layers from the same cell. This integrative perspective is particularly valuable for understanding cellular heterogeneity in complex tissues, disease microenvironments, and developmental processes. As a result, researchers are now able to trace lineage relationships, map cell fate decisions, and identify novel biomarkers with greater precision than ever before (

Figure 3) [

6,

7].

2.1.1. Technological Advancements in Single-Cell Multiomics

Single-cell multimodal omics techniques allow for the simultaneous analysis of genomics, transcriptomics, epitranscriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics in individual cells, making them valuable for studying complex cellular processes. A more comprehensive understanding of cellular function and regulation can be achieved by integrating multimodal information [

6,

7].

Recent advancements in single-cell multiomics have been driven by the development of high-throughput platforms and innovative analytical methods that allow simultaneous measurement of multiple molecular modalities. Technologies such as microfluidics, droplet-based sequencing, and combinatorial indexing have greatly increased the scale and accuracy of single-cell analyses (

Figure 3). These innovations have not only expanded the capabilities of researchers to interrogate cellular complexity, but have also facilitated the integration of transcriptomic, genomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data within individual cells, paving the way for more holistic and nuanced biological insights.

Single-cell sequencing was named ‘Method of the Year’ in 2013 for its accessibility and versatility. Recent scRNA-seq techniques are vital for analysing intercellular variation at scale. Multiomics technologies expand on this by integrating transcriptomic data with other types, boosting throughput via cell multiplexing, tagging, and hashing.

Simultaneous analysis of the genome and transcriptome can directly identify alterations in genetic material since the transcriptome is the product of the genome via transcription. We can gain valuable information by monitoring mutations and sequence specificity during the transcription of DNA sequences to RNA sequences, which helps to uncover changes in cellular phenotype. The initial methods of this kind were gDNA-mRNA sequencing (DR-seq) and genome and transcriptome sequencing (G&T-seq). In DR-seq, preamplified nucleic acids from a single cell are divided into RNA and DNA and sequenced. Recently developed methods include simultaneous isolation of genomic DNA and total RNA (SIDR-seq) [

8], TARGET-seq [

9], direct nuclear tagmentation and RNA sequencing (DNTR-seq) [

10], and scONE-seq [

11].

Concurrent examination of the transcriptome and methylome provides key insights into how DNA methylation influences transcription in heterogeneous cell populations. The current methods include single-cell genome-wide methylome and transcriptome sequencing (scM&T-seq) [

12], scMT-seq [

13], and SMART-RRBS62 [

14].

Simultaneous examination of the epigenome and transcriptome within a single cell enables analysis of how epigenetic regulation relates to gene activity in single-cells, offering greater insight into cellular diversity and regulatory patterns. Current methods include sci-CAR [

15], scCAT-seq [

16], SNARE-seq [

17], Paired-seq [

18], SHARE-seq [

19], and ISSAAC-seq [

20].

Proteins are central to cellular structure and biochemical activity, acting as enzymes. Characterizing their post-translational modifications and interactions at the single-cell level is crucial. While several methods have been employed for this purpose, a significant advancement in co-profiling the transcriptome and proteome by high throughput was established in 2017, through cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes by sequencing (CITE-seq). This method enables the integration of multiplexed protein marker detection with transcriptome profiling across thousands of single-cells [

21]. This was followed by the development of RNA expression and protein sequencing assay (REAP-seq)[

22] and SCITO-seq [

23].

Single Nuclei RNA-Seq (snRNA-Seq)

While scRNA-seq offers valuable insights, it has limitations. Firstly, it requires tissues to be processed into single-cell suspensions, a step involving enzymatic incubation at high temperatures that can cause artifacts and noise, detectable only after sequencing. Additionally, this process may favour easily dissociable cells, leading to biased cellular representation.

Single nuclei RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) addresses these issues by profiling gene expression from isolated nuclei, making it suitable for archived or hard-to-dissociate tissues. This method reduces bias in cell type isolation and better reveals the cellular basis of disease, enabling identification of otherwise difficult-to-isolate cell types.

In 2019, Wu et al. conducted a genomic study of the kidney, comparing scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq methods. Their results indicated that snRNA-seq achieves a comparable gene detection rate to scRNA-seq in adult kidney tissue, while also offering advantages such as compatibility with frozen samples and reduced dissociation bias. That same year, Joshi et al. applied snRNA-seq in a human lung biology study and observed that this approach enabled the identification of cell types from both frozen healthy and fibrotic lung tissues without bias [

24]. Sequencing adult mammalian heart tissue is challenging due to difficulties in tissue dissociation without cellular damage. Nevertheless, in 2020, researchers in Germany reported sequencing an adult mammalian heart using snRNA-seq and provided data on cell-type distributions within the tissue [

25].

2.1.2. Opportunities Provided by Single-Cell Multiomics

Single-cell multiomics is an emerging tool in molecular and cell biology that offers detailed insights into complex cellular environments. With the maturation of the technology and the increase in number of profiled cells, single-cell multiomics has empowered the identification of previously unknown rare cell types, the elucidation of cellular compositions, the characterization of cellular interactions in complex tissues, and the expansion of single-cell atlases for both diseased and healthy human tissues. The Human Cell Atlas (HCA) project seeks to profile all human cells in order to construct a comprehensive reference map. Since its launch, the HCA has assembled single-cell atlases at a large scale. The data collected by the project includes the fluxome, genome, metabolome, proteome, and transcriptome. Overall, the advent of single-cell multiomics has revolutionized the field of precision oncology, providing novel strategies for cancer management (

Figure 3).

2.1.2.1. Tracing Cell Lineages

Single-cell multiomics is mainly used to construct cellular lineage trees that track disease evolution. These trees help identify new cell types, trace cell lineages, and find biomolecular markers by thoroughly profiling cells at various developmental stages [

6].

Single-cell multiomics allow for the simultaneous collection of information regarding genomic copy number variations, the DNA methylome, nucleosome occupancy and the transcriptome of single-cells, which can reveal new cell types and their roles in a studied lineage. Profiling transcriptomes alongside chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation, histone modifications, and nucleosome organization offers new insights into cell identity and epigenetic processes in lineage priming [

26]. Integrating epigenome and transcriptome data from single-cells helps to reveal how DNA modifications drive cell differentiation. Single-cell proteomics methods analyse lineage-specific transcription factors and their abundance over time, which contributes to our understanding of how protein levels change as cells differentiate and ultimately leads to the maintenance or emergence of a lineage trajectory [

27].

Single-cell multiomics has had a large impact on cell lineage classification for cancer and our understanding of evolution of tumor cell states and types. The integration of genome, transcriptome, and lineage reporter techniques facilitates lineage tracing in cancer research. Insights into the persistence of epigenetic states and genetic mutations may contribute to the informed development of new therapies. Recent studies show that single-cell lineage analysis helps explain drug resistance in glioblastoma [

28] and clarifies which chronic lymphocytic leukemia lineages respond to treatment using combined transcriptome and methylome data [

29]. Overall, single-cell multiomics has greatly advanced disease lineage classification, tumor identification, and our understanding of cell state evolution.

2.1.2.2. Production of Cell-Type Atlases of Various Organs

Single-cell multiomics datasets grow more complex with additional samples, conditions, and acquisition methods. Integration methods aim to reduce batch effects while preserving biological variation. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) provides multiomics data focused on cancer, including over 20,000 primary cancer samples and their matched normal counterparts from 33 cancer types. This dataset includes genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic information. TCGA is the largest repository of cancer multiomics data and is widely used in scientific research. The role of TCGA in supporting different areas of cancer research, including pan-cancer studies, has been reviewed in previous sections.

2.1.2.3. Tumor Heterogeneity, Immunology, and Genetics

Single-cell multiomics technologies have added unprecedented breadth and depth into cancer research. Significant comprehensive and transformative knowledge are generated in immuno-oncology research. Single-cell multiomics helps researchers to define tumour and immune cell states and the interplay between them, identify predictive biomarkers of treatment response, infer the complex nature of antigen–immune receptor dynamics, and guide the development of therapeutics for multiple cancer types.

Integration Analysis of Single-Cell Multiomics reveals prostate cancer heterogeneity [

30]. This study integrates single-cell RNA sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and bulk ATAC-sequencing data obtained from a cohort of prostate cancer patients and healthy controls. In summary, the cellular heterogeneity is delineated in the stage-specific prostate cancer microenvironment at single-cell resolution, uncovering their reciprocal crosstalk with disease progression, which can be helpful in promoting prostate cancer diagnosis and therapy.

Single-cell multiomics uncover intra-cell-line heterogeneity across human cancer cell lines [

31]. This study conducted single-cell RNA-seq on 42 human cell lines and ATAC-seq on 39 lines to demonstrate transcriptomic and epigenetic heterogeneity within each line. This study conducts single-cell multiomics analysis of widely used human cancer cell lines, providing information about intra-cell-line heterogeneity and its dynamics that may be useful for future research involving cancer cell lines.

Single-cell multiomics with clonal resolution reveals differentiation pathways in acute myeloid leukemia [

32]. Inter-patient variability and the similarity of healthy and leukemic stem cells (LSCs) have impeded the characterization of LSCs in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and their differentiation landscape. The study presents CloneTracer, a new method that provides clonal resolution for single-cell RNA-seq data. In 19 AML patient samples, CloneTracer identified leukemic differentiation pathways. Taken together, CloneTracer reveals a differentiation landscape that mimics its healthy counterpart and may determine biology and therapy response in AML.

Single-cell multiomics is also employed to characterize the cancer immunosenescence landscape, which shows that patients exhibiting higher levels of immunosenescence signature have poorer prognoses.

Single-cell multiomics sequencing facilitates complementary therapeutic strategies by identifying region-specific characteristics of glioblastoma [

33]. In this study, paired tissues from the tumor core (TC) and peritumoral brain (PTB) were collected for integrated snRNA-seq and snATAC-seq analyses. The findings indicate molecular changes in infiltrated GBM cells and demonstrate the potential for combination therapy targeting intratumor heterogeneity both within and beyond the GBM region.

Single-cell multiomics identifies chronic inflammation as a driver of TP53-mutant leukemic evolution [

34]. In this study an allelic-resolution single-cell multiomic analysis was performed in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells from individuals with myeloproliferative neoplasms who progressed to TP53-mutant secondary acute myeloid leukemia. This study reveals a previously unknown effect of chronic inflammation, supporting improved risk assessment, early detection, and treatment strategies for TP53-mutant leukemia, with implications for other cancers.

Single-cell multiomics reveals that FABP1 + renal cell carcinoma drive tumor angiogenesis through the PLG-PLAT axis under fatty acid reprogramming [

35].

In another study, a barcode-shared transcriptome and chromatin accessibility map of 117,911 human lung cells from age/sex-matched ever- and never-smokers were developed to profile context-specific gene regulation. The finding indicates a context-dependent function for susceptibility genes [

36].

A single-cell multiomics atlas from 695,819 pre-infusion CAR T cells was examined to investigate the molecular determinants of ultralong CAR T cell persistence. The results reveal key mediators of lasting CAR T therapy response and indicate that enhancing type 2 functionality in CAR T cells may help maintain long-term remission [

37].

These methods have also been used to study immune-checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapies for human cancer. A study analyzing published single-cell data found that CXCL13+CD8+ T cells are associated with better ICB responses across tumor types [

38].

2.2. Spatial-Multiomics

Although single-cell multiomics has provided valuable insights into cellular heterogeneity, it lacks spatial context. Single-cell multiomics methods require cell dissociation, resulting in loss of information about cellular physical interactions. This spatial context is essential to many biological processes. Spatial multiomics overcomes this limitation by enabling the precise localization and molecular characterization of individual cells within their tissue environments [

39]. The advancements demonstrated by these innovative techniques are expected to build upon—and potentially surpass—the considerable progress achieved through dissociated single-cell approaches (

Figure 3) [

6,

7,

40].

2.2.1. Technological Advancements in Spatial Multiomics

Methods for spatial mono-omics including spatial transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics and metabolomics have progressed tremendously in the last decade. Single-cell multiomics provides data about gene regulation across different omics layers but does not offer the spatial information needed to analyze cellular functions within tissues. Now, the emerging trend is to integrate spatial mono-omics methods to perform spatial multiomics. Spatial multiomics facilitates the concurrent analysis of various data modalities—including transcriptomics, proteomics, genomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics—within a single tissue section (Liu, 2024).

Most spatial multiomics techniques build upon existing mono-omics methods, such as array-based spatial transcriptomics, microfluidic barcoding, DNA antibody tags, multiplex smFISH, in situ sequencing, and mass spectrometry imaging (

Figure 3) [

40]. These approaches can be applied independently to adjacent tissue sections, sequentially or concurrently on the same section, depending on analyte quality and compatibility. The number of analytes analyzed across molecular levels varies by method. Spatial multiomics is often complemented by histological stains like H&E for additional morphological context.

Integrating multiomics data remains technically challenging, requiring advanced computational and statistical tools. Interpretation is further complicated by environmental variability and technical noise, making the development of robust analytical methods for large-scale datasets crucial to fully realize the potential of spatial multiomics.

2.2.2. Applications of Spatial-Multiomics

Spatial multiomics advances precision oncology by providing detailed insights into tumor cell composition and tissue architecture. It also reveals cell-cell interactions and provides key insights into the spatial organization of the TME. Spatial multiomics is able to identify key cell-cell signaling pathways that drive tumor progression and affect treatment response. As a results, spatial multiomics has broad applications, including spatial-based heterogeneity in cancers, spatial-related crosstalk in tumor immunology, spatial trajectory and lineage tracking of tumor cells, biomarker discovery, disease mechanisms, drug target identification, and the development of novel therapies (

Figure 3) [

41].

Recently, various spatial multiomics methods have been employed in precision oncology. For example, spatial transcriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics were integrated to analyze glioblastoma and demonstrated bidirectional tumor-host interdependence. Notably, they revealed that hypoxia significantly affects glioma architecture and induces chromosomal rearrangements [

42]. Another study uses digital spatial profiling (DSP) technology to quantitate transcript and protein abundance in spatially distinct regions of metastatic prostate cancer. It shows that DSP is a great technology which can accurately classify tumor phenotype, assess tumor heterogeneity, and identify aspects of tumor biology involving the immunological composition of metastases [

43]. Another spatial multiomics study reveals the impact of tumor ecosystem heterogeneity on immunotherapy efficacy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with a bispecific antibody [

44]. Spatial multiomics has also been used to map immune activity in HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. The study evaluates intertumor heterogeneity using a 27-gene expression signature to stratify tumors by their immunologic activity status. This study shows that gene expression and cell colocalization signatures can predict immunological activity and immunotherapy response in HNSCC [

45]. Through spatial multiomics, it is revealed that SPP1+ fibroblasts play a pivotal role in determining metabolic heterogeneity and promoting metastatic growth of colorectal cancer liver metastasis [

46]. A comprehensive spatial multiomics strategy involving imaging mass cytometry (IMC), spatial proteomics, single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) and multiplex immunofluorescence have been developed for profiling breast cancer oligo-recurrent lung metastasis. This comprehensive analysis facilitates the development of therapeutic options to treat lung metastasis from breast cancer [

47]. Spatial multiomics is also used to analyze tumor-stroma boundary cell features to predict breast cancer progression and therapy response [

48].

Combined imaging-based spatial metabolomics and lipidomics with microarray-based spatial transcriptomics are employed to visualize intratumor metabolic heterogeneity in gastric cancer. This study provides a highly integrated picture of intratumor heterogeneity and reveals unique transcriptional features and significant immune-metabolic changes [

49]. Spatial multiomics has also been used to investigate the spatial distribution of intratumoral microbiota in breast cancer and their interactions with the local TME. The data revealed some novel roles of microbiota in breast cancer and identified potential therapeutic targets [

50].

2.3. Single-Cell-Spatial Multiomics and Human Tumor Atlas Network (HTAN)

As discussed above, both single-cell multiomics and spatial multiomics have its unique advantage and limitations. To maximize the advantages and overcome the limitations, single-cell spatial multiomics have emerged as the most powerful tool to reveal the molecular profiles of both normal and cancer cells/tissues in a temporal-spatial dynamic way. Integrating spatial multiomic data with single-cell multiomic data opens possibilities to add anatomical dimensions to existing datasets and to better understand cell-type-specific molecular profiles in humans (

Figure 3).

Single-cell spatial multiomics were initially developed as single-cell spatial transcriptomics by combining single-cell RNAseq with spatial transcriptomics. With the inclusion of more and more other single-cell mono-omics and spatial mono-omics, it truly becomes single-cell spatial multiomics. However, currently, based on the purpose of the study, most studies only combine select single-cell mono-omics (such as single-cell transcriptomic, single-cell proteomics, single-cell epigenomics etc.) with select spatial mono omics (such as spatial transcriptomics, spatial proteomics, and spatial epigenomics etc.).

Single-cell spatial multiomics-based international initiatives have emerged to facilitate the advancement and application of precision oncology. The Human Tumor Atlas Network (HTAN) is a prominent representative. HTAN leverages scientific collaboration to integrate samples, analytical modalities, and tools into detailed atlases of tumor evolution. HTAN offers a multidimensional view of cancer biology by expanding our spatial understanding of molecular, cellular and tissue features, which greatly helps the advancement of precision oncology.

Since 2018, HTAN researchers have gathered single-cell spatial multiomics data and used advanced analytical methods to better understand tumor ecosystems across various organs and types. This project demonstrates how spatial and single-cell data advances knowledge of cancer progression and supports the discovery of new tumorigenesis mechanisms. Following are some important contributions from the HTAN researchers, as well as from the broad scientific community (

Figure 3).

2.3.1. Tumor Evolution and Microenvironment Interactions in 2D and 3D Space

By using spatially resolved single-cell genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics

, a comprehensive study characterized 131 tumour spatial transcriptomics sections across 6 different cancers: uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, colorectal carcinoma, breast cancer, and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. The findings from this research have made significant contributions to the understanding of spatial tumour evolution through interactions with the local microenvironment in 2D and 3D space, providing valuable insights into tumour biology [

51].

2.3.2. Temporal Recording of Development and Precancer

Lineage tracing methods based on CRISPR evolving barcodes are utilized in studies of mouse development and mouse models of colorectal cancer. The findings reveal the polyclonal make-up of early cancers and their decreasing clonal diversity during the transition to advanced cancers. This result was also observed in human colorectal cancer samples at various stages of progression [

52].

2.3.3. Molecular Pathways Associated with Early Tumorigenesis in Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP)

Single-cell spatial multiomics, including transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic and lipidomic, were integrated to profile 93 samples, consisting of normal mucosa, benign polyps, or dysplastic polyps, from six persons with FAP. The results generated by this research reveal key genomic, molecular, and cellular events during the earliest steps in colorectal cancer formation and potential mechanisms of pharmaceutical prophylaxis [

53].

Besides HTAN associated studies, single-cell spatial multiomics has been employed by the scientific community to study various aspects of many cancer types.

2.3.4. Cancer Subtype Stratification

Single-cell spatial multiomics has been instrumental in cancer subtype stratification. The spatial immunophenotypes were assigned in TNBC by integrating spatial phenotypes and immunity effectors with multiplexed immunofluorescent imaging, scRNA-seq and TCR repertoire analysis, which helped to elucidate T cell evasion pathways in response to ICB [

54]. By integrating data generated with scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics sequencing, as well as bulk RNA sequencing, proteomic analysis, and genome sequencing, a recent study reveals novel subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma [

55].

2.3.5. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAF)

It is recognized that CAF plays an important role in cancer development, and single-cell spatial multiomics has been used to study CAF. Through integrative analyses of over 14 million cells from 10 cancer types across 7 spatial transcriptomics and proteomics platforms, a recent study validates and characterizes four distinct spatial CAF subtypes, which facilitates novel approaches to target and modulate CAFs [

56]. Integrating spatial and single-cell transcriptomes reveals the role of COL1A2(+) MMP1(+/-) cancer-associated fibroblasts in ER-positive breast cancer [

57].

2.3.6. Tumor Heterogeneity and Holistic TME Cellular Components

While tumor heterogeneity and TME cellular components have been studied by single-cell omics and spatial omics. Single-cell spatial omics allows for a deeper and broader understanding.

An integrated single-cell spatial multiomics landscape of WHO grade 2-4 diffuse gliomas has revealed locoregional metabolomic regulators of glioma growth [

58]. A high-throughput single-nucleus snRNA-seq and snATAC-seq multiomic dataset from matching "core" and "margin" dissections in four distinct grade 4 High-Grade Gliomas (HGG) patients are combined with new spatial transcriptomics data from two additional HGG samples to evaluate "core-to-margin" transition, which provides insights into the residual disease biology of tumors and the microenvironment at the infiltrative margin [

59]. By integrating 12 spatial and single-cell technologies, a recent study characterized tumor neighborhoods and cellular interactions in three skin cancer types [

60]. In neuroblastoma, single-cell multiomics from a mouse spontaneous tumor model and spatial transcriptomics from human patient samples are used to dissect the transcriptional and epigenetic landscapes governing developmental states and demonstrates tumour developmental plasticity [

61].

Multimodal single-cell-resolved spatial proteomics has been employed to reveal pancreatic tumor heterogeneity [

62]. Single-cell spatial multiomics has been used in several studies to gain insights into deadly pancreatic cancers. For example, immune dysfunction in pancreatic cancer has been analyzed by single-cell spatial multiomics, which reveals novel mechanisms underlying disease development [

63].

2.4. Patient-Derived Tumor Organoids (PDTO)

The identification of features specific to each patient and tumor is central to the development of precision medicine and preclinical studies for cancer treatment. However, cancer is associated with a high degree of inter- and intra-tumor heterogeneity, which leads to considerable variability in clinical response to common treatments across patients. This heterogeneity has hindered precision cancer treatments until the emergence of PDTOs. PDTOs stably recapitulate the structures, specific functions, molecular characteristics, genomics alterations, and expression profiles of primary tumors, as well as permit genomic and environmental manipulation. PDTOs are an indispensable tool in precision oncology to mimic illnesses, explore mechanisms, identify innovative therapeutic targets, screen and assess novel drugs in a high-throughput manner, and customize treatment regimens for individual cancer patients [

64]

-[

68].

2.4.1. A Brief History

An organoid is a three-dimensional structure created in vitro that replicates key functional, structural, and biological characteristics of an organ in a simplified and smaller form. Organoids are derived from either pluripotent or tissue-resident stem (embryonic or adult) or progenitor or differentiated cells from healthy or diseased tissues, such as tumours [

69].

It was proposed over a century ago that complex tissue/organ structures could be recreated in vitro through self-organization and regeneration and could be utilized to recapitulate parts of complete tissues or organs. The notable plasticity of embryonic tissue was initially suggested by observations of cell dissociation and subsequent reaggregation in vertebrates in the mid-20th-century. Scientists have sought to maintain or recreate tissue/organ complexity through various three-dimensional (3D) cell culture approaches. The spheroid model was proposed in the early 1970s by radiobiologists [

70]. These compact spherical structures, typically over 1 mm in size, are mainly derived from immortalized cell lines. In 1987, the optimization of cell culture conditions enabled mammary epithelial cells to assemble into 3D spheroids and ducts [

71]. In 1998, human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) were successfully extracted from human blastocysts, opening the door for the development of regenerative medicine [

72]. In the early years of the 21st century, iPSCs were successfully generated through the reprogramming of mouse and human fibroblasts. iPSCs are similar to embryonic stem cells. Pluripotent stem cells serve as organ progenitors capable of differentiating into various cell types in culture, which has greatly advanced the development of three-dimensional organoid models [

73].

Over the past decade, PDTOs have contributed to developments in 3D culture in precision oncology research. In 2009, it was shown that an adult intestinal stem cell expressing the LGR5 receptor, isolated from mice, could be cultured to form structures and cellular diversity resembling the crypts and villi of the intestinal epithelium [

74]. Organotypic cultures have since been created from various primary tumors and have shown to better mimic original tumor features than traditional cell lines. An effective PDTO can grow, store, and freeze cells that maintain the genetic and histological features of the original tumour. In addition, PDTOs are amenable to modelling TME cell heterogeneity and heterotypic cell interactions through co-culture with non-neoplastic cell types, including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and various immune-cell types. As a result, PDTOs demonstrate utility in various aspects of cancer research, including cancer therapies, disease progression and tumour niche factor requirements [

67].

2.4.2. Application of PDTOs

2.4.2.1. Cancer Biology

Organoids including PDTOs are increasingly being used to understand cancer biology. Organoids have been used to model the stages of tumorigenesis in various types of tumors. The formation of organoid from cells can be evaluated to reveal different stages of tumor evolution. Observing this process shows that inactivating tumor suppressor genes (such as TP53, PTEN, or APC) and activating oncogenes (such as KRAS) are keys to tumor formation. Studying the shift from healthy to tumor organoids helps clarify the molecular basis of tumor initiation and may reveal novel biomarkers for early cancer diagnosis, advancing precision oncology [

67]. Tumor organoid models may also be relevant for mimicking the genomic evolution of tumors, as shown by a recent study in bladder cancer [

75].

Mechanisms underlying drug resistance are dynamic and sequential, including irreversible mutational changes, epigenetic changes, metabolic reprogramming, modification of the tumor microenvironment, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition. These changes are difficult to observe in patients or animal models. Organoids have shown potential to recapitulate the clinical response of the original tumor and thus could be used to track the sequence of resistance acquisition and identify the involved mechanisms in a reproducible and more relevant manner. Furthermore, combined with imaging techniques, the different responses of cells within the PDTO can be analyzed separately to overcome the challenges imposed by cell heterogeneity.

Recently, researchers have used molecular comparisons between PDTOs from chemotherapy-treated patients and those from untreated tumors to find targetable signaling pathways [

76]. Another method is growing tumor organoids from chemotherapy-treated PDXs in mice to measure parameters not assessable in vivo [

77]. Organoids have also been used to model acquired resistance in pancreatic cancer [

78].

In recent years, a three-dimensional (3D) organoid culture of human tumour tissue has gained recognition as a cost-effective and representative platform for modelling cancer heterogeneity and tumour microenvironment interactions in vitro.

Organoid models from human tumors capture both intra- and intertumoral diversity, reflecting the (epi)genetic and phenotypic variation among neoplastic cell subclones and their tumor-specific morphology. Studies have modeled patient-to-patient heterogeneity by creating ‘living biobanks’ of organoids derived from cancer tissues. Pancreatic cancer organoids from a genetically and phenotypically comprehensive cohort of 138 patient tumor samples have been established, which revealed population-level genetic and transcriptomic signatures associated with anticancer drug responses [

79]. A biobank consisting of 55 colorectal cancer organoid lines was established, representing a range of tumor phenotypes, including both primary and metastatic lesions [

80].

Cancer organoids also enable modelling of TME heterogeneity, including the presence and functions of non-neoplastic TME cells, the signalling of niche-specific soluble factors and the altered composition of the extracellular matrix (ECM). Recent studies have aimed to create culture platforms that better reflect TME cell diversity and their interactions. It is shown that native CAFs and immune cell types could be retained in PDTOs to test personalized immunotherapies [

81]. The authors recreated the in vivo tumor-infiltrating T-cell repertoire and modelled patient-specific PD1/PDL1-dependent immune suppression. Schmalzier et al. also introduced a platform to evaluate cancer immunotherapies using human CAR-engineered natural killer cells targeted at patient-derived CRC organoids [

82].

2.4.2.2. Clinical Application

Organoids offer multifold potential applications, including high-throughput screening of anti-cancer drugs, evaluation of drug toxicity and side effects, identification of therapeutic targets and drug candidates, predicting drug sensitivity, customized therapy in clinical settings, emulation of pathological processes for disease modeling, as well as enhance fundamental research through CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing [

65]

A major clinical application of PDTOs is drug screening. The PDTO model allows for high-throughput screening of therapeutic options, making it possible to identify tumor subtypes that could preferentially benefit patients. Tumor organoids derived from rectal cancer patients have been used to conduct drug sensitivity tests. These findings were used to guide patient treatment with a success rate of 88% in terms of effectiveness [

83]. Another study utilizes lung cancer organoids for high-throughput drug screening and prediction of drug response, which could potentially facilitate personalized cancer treatment strategies [

84]. Through high-throughput drug screening, a study evaluated 76 drugs across 30 PDOs obtained from pancreatic tumors and showed the potential of the PRMT5 inhibitor EZP015556 in inhibiting MTAP-negative tumors. Moreover, the generated data base was used for screening addition drug candidates [

85]. Another organoid platform was developed for high-throughput screening of 2,427 drugs to test their sensitivity colorectal cancer [

86]. Panels of PDTOs from various tumor types have been used to screen therapeutic molecules. In gastric cancer, nine PDTOs were exposed to 37 clinical and developmental compounds, confirming their responsiveness to existing targeted therapies [

87]. Similarly, colorectal cancer-derived PDTOs were screened with 83 molecules, highlighting links between drug efficacy and specific genetic alterations [

67]. By recapitulating tumor heterogeneity and imitating the characteristics of the original tumor, the PDTO model allows for high-throughput screening of numerous emerging therapeutic options.

PDTO panels are utilized to identify predictive molecular signatures—including genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic markers—associated with treatment responses. Increasing evidence demonstrates that PDTOs can accurately forecast the responsiveness of their source tumors to anticancer therapies [

88].

2.4.3. Challenges and Limitations

Despite the rapid development and wide application and unique ability to address difficult questions facing precision oncology, current PTDOs have several limitations and challenges. The experimental protocols are still too complicated, which hinders the timely delivery of reliable data to the clinicians for optimal clinical management. Organoid creation and maintenance are expensive, raising concerns about cost. Tumor tissues are complex and varied, but current organoids do not fully reflect this diversity in vitro. Success rates for generating cancer organoids differ widely across tumor types. Despite improvements in protocols, techniques remain variable and difficult to reproduce due to non-standardized tissue sources, processing methods, media, and matrices [

64,

65,

67].

Moving forward, the emerging trend is to develop more complex models that recapitulate in vivo structure and function as faithfully as possible and enhance its application value in clinical treatment and drug development. Tumor organoids can be co-cultured with non-tumor cells or iPSC-derived organoids, which enables the investigation TME and the effects of immune cells in the absence of an immune system. Moreover, organoids can be integrated with advanced technologies such as 3D printing and organ chips to create engineered organs.

2.5. Liquid Biopsy

Liquid biopsy is an emerging precision medicine method that examines blood and other body fluids for insights into a patient’s health. It is a non-invasive technique for identifying and analyzing biomarkers such as circulating tumor cells (CTCs), cell-free DNA (cfDNA), circulating carcinoma proteins, circulating miRNAs, and exosomes. It allows for real-time monitoring of a patient’s cancer mutations and genomic profile. Liquid biopsies are quicker, safer, and more practical than conventional tissue biopsies, and they also allow for serial samples to monitor tumor evolution over time (

Figure 4) [

89,

90]. Although liquid biopsy has the potential to disrupt the field of medical diagnosis, it is met by various challenges such as limited tumor-derived components, less specificity, and inadequate advancement in methods to isolate biomarkers.

Liquid biopsies include both blood-based and non-blood-based methods. Due to its prominence, blood-based biopsies also are referred to as liquid biopsies. Non-blood-based liquid biopsies include urine analysis, breath analysis, and saliva analysis, which were recently reviewed by other articles [

91,

92] and will not be discussed here.

2.5.1. Circulating Tumors Cells (CTCs)

First discovered in 1869 by Thomas Ashworth, CTCs are cancer cells shed into the bloodstream from primary or metastatic tumor sites [

90,

93]. In the last 20 years, CTCs have been detected across a breadth of malignancies of both epithelial and non-epithelial origin including prostate cancer, ovarian cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, bladder cancer, renal cancer, lung cancer, glioblastoma, melanoma [

94,

95]. CTCs are traditionally characterized as nucleated cells present in a blood sample that exhibits negative staining for the ubiquitous leukocyte marker CD45 while demonstrating positive staining for epithelial cytokeratin.

Analysis of CTCs through liquid biopsy has been used for decades in various cancer types, showing applications in early diagnosis, prognostic risk assessment, disease monitoring, and informing personalized treatment decisions. CTCs are intact tumor cells that originate from primary or metastatic tumors. This characteristic enables CTCs to serve as a source of information at multiple molecular levels, including DNA, RNA, protein, and metabolites. In addition, CTC monitoring uses routine blood draws rather than tissue biopsies, offering a less invasive and more repeatable method for detecting cancer and assessing its progression.

Major challenges are that CTCs exhibit high heterogeneity and have a short half-life of just 1-2.4 hours in circulation, existing at extremely low concentrations in peripheral blood [

90]. It has been estimated that although millions of CTCs are shed daily into the circulation per gram of tumor tissue, CTCs still comprise only a minute fraction of total cells present in blood, with as few as one tumor cell per 10 billion blood cells [

95]. Facing these challenges, the clinical potential of CTC-based diagnosis has not been fully realized due to the limitation of the existing methods and devices to harvest CTCs and their clusters from peripheral blood [

96]. Therefor, the advancement of CTCs in precision oncology is significantly dependent on the advancement of CTC enrichment technology.

All CTC isolation strategies exploit unique properties of CTCs including distinct immunological, molecular, and/or bio-physical properties. These strategies are classified into two main classes: methods that achieve up to 10[

4]-fold CTC enrichment and methods that achieve up to 10[

8]-fold enrichment [

95,

97]. The methods for 10[

4]-fold enrichment include direct visualization of CTCs, CTC capture based on size or physical properties, positive immunoselection of CTCs, and depletion of hematopoietic cells to achieve negative enrichment of CTCs. To achieve10[

8]-fold enrichment, additional purification is required and typically involves labeling residual white blood cells and CTCs using fluorescence-conjugated antibodies, optically identifying CTCs, and sorting them individually. The use of droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies is another approach [

95,

97].

In addition to CTCs, metastasis is facilitated by dissemination of cell clusters containing CTCs. Some CTCs travel in clusters, ranging from doublets to dozens of cancer cells tethered together. Some clusters may include tumor-derived fibroblasts, blood-derived leukocytes, or other cells. Other methods have also been developed to isolate CTC clusters. For example, negative enrichment of CTC clusters from peripheral blood samples based on the apoptosis resistance of malignant cells of tumorigenic origin and enrichment by immunocytochemistry profiling [

96,

98].

2.5.2. Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA)

ctDNA comprises small fragments of DNA that are released by tumor cells into the blood and tissue fluids. The molecular similarities observed between plasma ctDNA and tumor tissue, combined with the practicality of measurement via blood draw, suggest that ctDNA may serve as a biomarker for primary cancer screening. Plasma ctDNA concentration is related to tumor location, size, and disease extent. Detection of ctDNA in liquid biopsy material has gained attention due to recent advancements in DNA technologies.

Half a century ago, scientists realized that plasma levels of free DNA increased in cancer patients [

99]. Specific mutated genes began to be identified in the blood of cancer patients in the form of ctDNA about 20 years ago, including KRAS and PIK3CA in patients with colorectal cancer [

100], EGFR in breast cancer patients [

101] and in NSCLC patients [

101,

102]. Many studies demonstrate that the plasma ctDNA concentration is associated with tumor location, size, and extent of disease [

103]. For example, it is shown that ctDNA positivity is in 42%, 67% and 88% of patients with stage I, II, and III NSCLC, respectively [

104]. In 2014, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved the use of ctDNA for detecting EGFR mutations in NSCLC [

105]. ctDNA assay was recommended for cancer patients by the Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Precision Medicine Working Group in 2022 [

106].

Different cancers have different patterns of epigenetic characteristics (e.g., nucleosome distribution) and different preferential genomic breakpoints where ctDNA is generated, which forms the basis to predict the types of primary tumors. Although these signatures are not necessarily unique to one sub-type, it is still possible to identify the cancer type by comparing DNA methylation profiles, nucleosome footprints, and genetic alternations of ctDNA with those in the reference databases [

103,

107].

Because ctDNA is highly fragmented and scarce, increasing detection sensitivity remains a key research focus. With the development of second-generation sequencing, it is possible to detect multiple gene variants simultaneously and generate high-throughput data. Currently, ctDNA detection is well-developed and includes two main types: targeted PCR-based methods and nontargeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques.

While ctDNA could be applied to other applications such as monitoring disease progression and evaluating treatment effectiveness, it is mostly used for cancer screening and diagnosis. It was initially used to screen for specific cancer types, and multiple platforms have been on the market including ExoDx prostate Intelliscore and SelectMDx for prostate cancer [

108], Shield [

109], Freenome test, and Epi proColon [

110] for colorectal cancer, Viome CancerDetect for oral and oropharyngeal cancer [

111], and a test for breast cancer [

112].

ctDNA now is heavily explored for multicancer early detection (MCED). With the years several MCED platforms have been developed including CancerSEEK and PANSEER for 8 solid tumors [

113,

114], TEC-seq for 4 solid tumors [

115], OverC for 6 solid tumors [

116], and ARISTOTLE for 10 solid tumors [

117]. The sensitivity of these tests varies between 29% and 98%, while the specificity is close to 100% [

103].

In recent years, more comprehensive studies have been conducted to screen and diagnose more cancers with or without symptoms. In 2023, the first large-scale prospective evaluation of an MCED diagnostic test in a symptomatic population was conducted in England and Wales (SYMPLIFY) [

118]. The study, which included 6,238 participants, assessed the performance of a methylation-based MCED diagnostic test in symptomatic patients referred from primary care. The findings indicate that the current MCED test may identify symptomatic patients for further investigation who do not meet existing referral criteria, pending confirmation in an interventional trial. The test may also have potential use in guiding decisions about which patients may not require additional investigations.

Another study, the NHS-Galleri trial (ISRCTN91431511), aims to establish whether an MCED test that screens asymptomatic individuals for cancer can reduce late-stage cancer incidence. This randomized controlled trial has enrolled over 140,000 individuals without cancer diagnosis or treatment and are not undergoing investigation for suspected cancer in England. The findings may provide valuable insights for determining the appropriateness of implementing the MCED test within population screening programs [

119]. At the same time, another large multi-institutional prospective study in the U.S, PATHFINDER, investigated the feasibility of cancer screening with MCED testing, using next-generation sequencing of cell-free DNA in peripheral blood, with a focus on diagnostic investigations in participants who tested positive for a cancer signal. The study detects cancer-specific methylation patterns from ctDNA in more than 50 distinct cancer type [

120]. This study supports the feasibility of MCED screening for cancer and underscores the need for further research investigating the test’s clinical utility.

2.5.3. Exosomes

Exosomes offer a promising option and can enhance liquid biopsy diagnostics in some cases. Exosomes carry less information than CTCs, but much more information than ctDNAs as they contain DNAs, RNAs, proteins, lipids, and others. Exosomes are secreted by living cells, offering a more representative view of the cellular state than cell-free DNA (ctDNA), which is primarily released by dying cells. The lipid bilayer of exosomes provides a stable environment for the biomolecules they carry, protecting them from degradation and making them reliable diagnostic indicators. The rich chemistry of exosomes offers various therapeutically relevant diagnostic options. There is a possibility that exosomes may be used for cancer screening and early diagnosis because of the information they disclosed about viable tumor cells. A cancer cell can release about 20,000 vesicles in 48 hours. Tumor-related exosomal biomarkers have been studied in cancers such as lung, breast, kidney, prostate, and colorectal cancer [

121].

In order to be used as a biomarker, exosomes must first be separated from the respective biofluid. Many methods have been developed over the years including the conventional methods such Centrifugation-Based Methods, Ultrafiltration Methods, Precipitation Methods, Field Flow Fractionation Methods, Chromatographic Methods, and Affinity Binding-Based methods [

122], as well as newly developed microfluidic technology-based methods. Advances in microfluidic technology enable efficient and portable exosome separation and detection, paving the way for point-of-care applications [

122,

123].

Combining different exosomal components (RNA, proteins, lipids) and integrating them with other liquid biopsy markers (like ctDNA) can improve diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. Mutations in exosomal RNA can complement ctDNA signals, enhancing mutation detection sensitivity. Studies indicate that cfDNA combined with exosomal RNA outperforms cfDNA analysis alone [

124].

2.5.4. Other Biomarkers

Liquid biopsies can also analyze other tumor-derived material like proteins, metabolites, and RNAs.

2.6. Non-Invasive Imaging Methods

Conventional oncology image analysis, utilizing modalities such as ultrasound, X-ray, CT, and MRI, has traditionally depended on manually defined features for the interpretation and evaluation of clinical images. The low precision has impeded the accurate diagnosis of the cancer, leading to more unnecessary biopsies. Recent breakthroughs in oncologic imaging leads to the emerging and development of cancer molecular imaging, which have transformed cancer diagnosis, treatment planning, and monitoring.

2.6.1. Cancer Molecular Imaging

Cancer molecular imaging is the non-invasive visualization of molecular and cellular processes characteristic to neoplasia, such as proliferation, glucose metabolism, and receptor expression. Several molecular imaging modalities are now available, including magnetic resonance, optical, and nuclear imaging [

125]. Cancer molecular imaging is mostly supported by dual-modality imaging, such as PET/CT (commercialized in 2001) and SPECT/CT (commercialized in 2004), which combine anatomical, metabolic, and functional information for more accurate diagnosis. [

126]. Other molecular imaging technologies have also improved significantly, enhancing their capabilities to support precision medicine. For example, MRI is able to generate high-resolution anatomic images of soft tissue. Optical imaging is empowered by the use of bioluminescence, fluorescence, and near-infrared imaging. Ultrasound imaging offers real-time, portable, nonradioactive options [

92,

126].

In recent years, significant novel developments of molecular imaging have been reported including the super-resolution fluorescence microscopy which allows nanoscale visualization of cellular processes, DNA-based point accumulation in nanoscale topography (DNA-PAINT) with sub-20 nm resolution, and photoacoustics that offers the ability to image deep tissues. Moreover, the accumulation of imaging data, coupled with advances in machine learning, has enabled the discovery of hidden biomarkers and quantitative features in cancer molecular images [

126].

RECIST is a system for evaluating tumor response to treatment by measuring changes in lesion size on standard imaging. However, it can be slow and sometimes inaccurate when assessing targeted therapies. Molecular imaging techniques have the potential to overcome this weakness due to its ability to quantitatively assess the response at the cellular, subcellular, or even molecular level [

127].

As precision medicine continues to evolve, the application of molecular imaging will continue to evolve alongside it, encompassing a wider range of clinical and research settings.

2.6.2. Omics Imaging, Radiomics and Imaging Genomics

Due to the widespread availability of omics data and improvements in imaging technologies, integrating biomedical image information with omics data has become feasible. This integration process can reveal the links between the micro-level molecular information generated by various omics with the macro-level structural and functional information provided by biomedical images. This newly emerging interdisciplinary field is named omics imaging.

Omics imaging focuses on integrating omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, etc.) with structural, functional, and molecular imaging data. Bridging imaging and omics factors and exploring their connections has the potential to provide important new insights into the phenotypic characteristics and molecular mechanisms of cancer development. These, in turn, will impact the development of new diagnostic, prognostic, therapeutic, and preventive approaches, becoming an important component of precision oncology [

128].

Radiogenomics uses big data to aid cancer diagnosis and treatment decisions, offering insights into tumor biology and identifying key imaging biomarkers. These approaches have been validated in a variety of tumors including glioblastoma, breast cancer, liver cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, lung cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, retinoblastoma, head and neck squamous cell cancer [

129].

2.7. AI powered Data Integration, Machine Learning and Deep Learning

The primary objective of precision medicine is to combine substantial amounts of data from various databases into analytic frameworks that support the creation of diagnostic and therapeutic methods that are individualized and context specific. This data is generated by various layers of high-throughput technologies such as multiomics. However, it faces challenges over its dimensionality, interpretability, predictability, and high computational power demand. Integration of AI into precision oncology provides the best solution to overcome these challenges. AI can be used to build analytical models of complex disease to improve diagnostic accuracy, optimizing treatment strategies, and enhancing patient care through personalized interventions and remote monitoring that predict personalized health conditions and outcomes. AI has rapidly emerged as a transformative force in precision oncology and has revolutionized various aspects of cancer care from diagnosis to treatment [

130,

131].

2.7.1. Principles and Workflow

A workflow for data integration by AI modeling in precision medicine include the following steps: A) Selection of the data sources. A wide variety of data sources with diverse features are available for selection. B) Data collection and pre-processing. Different approaches to data collection and pre-processing are needed to deal with the diverse data sources. C) Integration of the diverse and heterogenous data through data processing and modeling. D) Application of the integrated data to precision medicine for diagnosis, treatment strategies, and outcome prediction [

130].

2.7.2. Subtypes of AI in Medicine

AI in medicine manifests in various subtypes, each with unique functionalities.

2.7.2.1. Machine learning

Machine learning is a branch of AI that uses algorithms to mimic human learning. It helps uncover patterns in medical data that may escape experts. Common healthcare algorithms include decision trees, support vector machines, and random forests, which analyse large datasets to predict treatment protocols and outcomes [

131,

132].

2.7.2.2. Deep learning

Deep learning constitutes a branch of machine learning that leverages multilayered neural networks to accomplish tasks including classification, regression, and representation learning. The discipline draws conceptual frameworks from biological neuroscience and focuses on organizing artificial neurons into hierarchical layers, which are "trained" to process information efficiently. Deep learning techniques are particularly effective for analyzing intricate data patterns, such as those found in images, natural language, and genomic sequences. Some common deep learning network architectures include fully connected networks, deep belief networks, recurrent neural networks, convolutional neural networks (CNN). CNN is a powerful deep learning method that enables the precise detection of malignant lesions.

2.7.2.3. Transfer Learning

Transfer learning is a technique in machine learning in which knowledge learned from a task is re-used in order to boost performance on a related task.

2.7.2.4. Natural Language Processing

Natural language processing enables machines to understand and generate human language. It is used to extract information from medical records, summarize patient histories, generate tailored treatment plans, transcribe patient-doctor interactions, and produce medical reports. Much patients’ information is stored in free-text format in electronic health records... Natural language processing techniques can be used to extract information from unstructured clinical notes and social media data, enabling analysis of patient experiences and disease trends [

133].

2.7.2.5. Computer Vision

Computer vision empowers machines to interpret and understand visual information from the world, such as images and videos, which is essential for medical image analysis, detecting abnormalities in X-rays or MRIs, and assisting in surgical procedures.

2.7.3. Application in Precision Oncology

2.7.3.1. Cancer detection

AI has been applied for the detection of almost all types of cancers including breast cancer, lung cancer, skin cancer, colorectal cancer, and prostate cancer.

AI-based tools for detecting breast cancer via mammography represent a rapidly advancing field, with many systems progressing toward real-world clinical application [

134]. Several AI products have received FDA clearance for assisting radiologists with the detection of breast cancer from mammograms, as well as in interpreting MRI and breast ultrasound examinations. Ongoing prospective studies are being conducted to assess these products within clinical settings. A recent clinical study in Sweden demonstrated that integrating AI into mammography screening workflows significantly decreased radiologists’ workload—by approximately 44%—without compromising diagnostic performance [

135]. The application of AI to predict future breast cancer risk is also explored by several studies and these AI risk prediction algorithms have been shown to outperform traditional risk models [

136]

-[

138].

Similar studies have applied deep learning to colonoscopy images and video for colorectal cancer screening and reported increased detection rate [

139]

-[

141]. AI has also been used to localize lung nodules for purpose to predict lung cancer risk [

142,

143] and to predict prostate cancer risk [

144,

145]. Advanced deep learning models have been developed for skin-cancer detection [

146].

2.7.3.2. Cancer treatment

AI algorithms are also being developed to improve treatment, including designing personalized treatments and monitoring treatment efficacy. For example, AI is used to predict the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in TNBC [

147] and in predicting the prognosis for breast cancer [

148] and colorectal cancer [

149].

2.7.3.3. Cancer biology

AI has been used for the interpretation of germline and somatic mutations observed in cancer. For example, deep learning was employed in a recent study to detect pathogenic germline variant in prostate cancer and melanoma [

150]. Various deep learning-based model have been used in recent research to identify driver genes and pathogenic variants. Researchers have developed a deep learning tool called Dig, which models mutation rates across the genome with high resolution. Applied to data from 37 different cancer types, this approach has proven more effective than several existing methods in pinpointing likely driver mutations, showing both higher sensitivity and accuracy [

151]. AlphaMissense, an AI tool developed using advancements from AlphaFold, has recently been used to assess missense mutations, suggesting that nearly one-third of all such protein variants could be disease-causing [

152]. Additionally, CancerVar, another deep learning-based platform, has been developed to predict the oncogenicity of somatic variants using both functional and clinical features [

153].

Multiple AI methods have developed cell-of-origin prediction, which is particularly relevant for cancers of an unknown primary. These AI models are based on various omics such as genomics [

154,

155], transcriptomics [

156], and proteomics [

157]. The OncoNPC model, trained using sequencing data from tens of thousands of tumor samples spanning over 20 cancer types, has demonstrated strong predictive power. When assessed on cancers of unknown origin, it successfully identified likely primary sites in about 41% of cases. It also identifies subgroups with significantly higher polygenic germline risk for the predicted cancer types [

155]. Another study developed a deep neural network model to classify cancers based on gene expression data. It analyzed transcriptomics data from 37 cancer types provided by TCGA to identify cancer tissue-of-origin specific gene expression signatures [

156]. Cross-protein transfer learning substantially improved disease variant prediction in a recent study [

157]. In this study, cross-protein transfer models were trained using deep mutational scanning data from only five proteins and achieved state-of-the-art performance on clinical variant interpretation for unseen proteins across the human proteome.

Various AI algorithms have also been established for detecting cancer specific neoantigens [

158,

159] and associated T-cell receptors [

160,

161]. Deep learning on pathology images are also used to analyze spatial organization and molecular correlation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes to better understand TME [

162].

Various AI models have also been developed for the purpose of cancer subclassification. For example, a comprehensive deep learning and transfer learning analytic model has been introduced for skin cancer classification [

163].

3. Complete Understanding of the Tumor Biology

A complete understanding of tumor biology is the key for cancer prevention, early detection and diagnosis, and effective treatment, which is also the ultimate goal of precision oncology. With the rapid development of novel and powerful technologies as discussed above, we now have a much deeper understanding of cancer biology. The discovery of novel knowledge and the emergence of novel concepts and principles have significantly advanced precision oncology.

3.1. Tumorigenesis/Cancer Initiation

Tumorigenesis is a complex, multistep process in which oncogenic mutations within normal cells initiate clonal expansion. This progression is significantly modulated by additional factors, including environmental tumor risk elements and epigenetic modifications, both of which can substantially affect early clonal proliferation and malignant transformation independently of mutational events [

164]. A deeper understanding of the earliest molecular events holds promise for translational applications, predicting individuals at high-risk of tumor and developing strategies to intercept malignant transformation.

3.1.1. Genomics and Cancer Genes

Mutation processes acting from embryological development onwards drives clonal evolution by generating variation in the tumor cell population. Some of these mutations occurs in cancer driver genes that fuel positive selection [

4,

164]. Driver genes are a specific subset of genes that harbor mutations directly contributing to the initiation and progression of cancer. These genes often regulate critical cellular processes such as the cell cycle, apoptosis, and DNA repair. Mutations in driver genes give a growth advantage to the cells and are thus positively selected; they promote clonal expansion and can lead to uncontrolled proliferation [

4,

164,

165].

Early genomic alterations encompass point mutations, short insertions, deletions, structural variations, copy number changes, gene fusions, and methylation differences. Analysis of exome data from 33 tumor types has identified 229 genes undergoing positive selection [

166]. Further investigation into somatic mutations across more than 28,000 tumors representing 66 cancer types has revealed 568 cancer-associated genes and provided insights into their roles in tumorigenesis [

167]. Utilizing data from 2,658 cancers across 38 tumor types provided by the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) Consortium under the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC), sixteen distinct signatures of structural variation have been characterized [

168]. In a recent study, MethSig was developed to specifically identify candidate DNA methylation driver genes of cancer progression and relapse from 22 cancer types. Chromosomal instability (CIN) leads to extensive losses, gains, and rearrangements of DNA. The resulting genomic complexity is recognized as a hallmark of cancer; however, no comprehensive framework currently exists to systematically quantify various forms of CIN or assess their impact on clinical phenotypes across cancer types. This study analyses the extent, diversity, and origin of chromosomal instability in 7,880 tumors spanning 33 distinct cancer entities. Seventeen copy number signatures defining specific CIN types have been identified, which facilitate drug response prediction and support the discovery of novel therapeutic targets [

169]. Accumulating evidence suggests that clones with aberrantly rewired epigenetic programs show increased tumor susceptibility in morphologically normal tissues [

170]. For example, during precancerous evolution of lung cancer, epigenomes undergo a stepwise progression, culminating in a high level of intra-tumor heterogeneity in invasive lesions. The phylogenetic patterns inferred from methylation aberrations resemble those based on somatic mutations, suggesting parallel methylation and genetic evolution [

171].

3.1.2. Clonal Expansion

Through intensive studies, the process of cancer initiation begins with healthy tissue through clonal expansion [

4]. Single-cell spatial multiomics and many other cutting-edge technologies have been employed to study cancer clonal expansion from normal tissue in many different cancer types [

172]

-[

174]. However, many issues remain unsolved and have become emerging research areas. For example, how can cancer driver events exist in normal tissues? Some studies suggest that selection pressure is different under different environments. NFKBIZ mutations may confer a selective advantage in a chronically inflamed environment; however, these mutations may be negatively selected in cancer and restrict tumor formation [

98]. Little is known about how such dynamic competition in normal epithelia influences early tumorigenesis. A recent study shows that the majority of newly formed oesophageal tumours are eliminated through competition with mutant clones in the adjacent normal epithelium [

175].

Understanding mechanisms driving the clonal expansion of normal tissue toward early cancer initiation will provide insight into cancer prevention and treatment and is thus an important topic being explored.

3.1.3. Environmental Carcinogenesis

The causal links between environmental exposures and cancer initiation has been gradually established [

176]

-[

179]. These environmental factors include chemical and radical insults, unhealthy metabolic behaviors such as alcohol consumption and smoking, and specific pathogenic infections. These environmental factors induce genetic and epigenetic alterations in transformed cells and have profound impacts on microenvironmental components that predispose to tumor initiation. For example, KRAS G12C mutations in NSCLC are generated through smoking-related mutagenesis [

180,

181].

However, many environmental factors cause cancer by mechanisms other than mutations [

182]. This non-mutagenic carcinogenesis is an emerging hot research topic [

4]. One likely mechanism is the deregulation of cancer-related gene expression through epigenetic modifications [

4,

183]

-[

185]. Another mechanism may be through chronic inflammation. Some studies indicate that many environmental factors cause local inflammation, which provides a different selection pressure in favor of cancer initiation [

164,

185]. The mechanisms by which inflammation facilitate early tumorigenesis include oxidative stress, DNA damage, mutation clone expansion, cell proliferation, and cell survival [

34,

98,

186,

187].

3.2. Tumor Heterogeneity

Thanks to the development of single-cell spatial multiomics, the concept of tumor heterogeneity has moved onto the center stage of cancer research. Both intertumoral and intratumoral heterogeneity are crucial factors for the complete understanding of molecular foundation of tumors. While intertumoral heterogeneity has been well studied and largely reflected by molecular stratifications based on driver genes, pathways, and expression profiles, intratumor heterogeneity (ITH) is much less understood and is an emerging area being extensively studied [

2,

4].

ITH is frequently observed in malignant tumors and results from dynamic changes involving genetic, epigenetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolic, and microenvironmental factors. This complexity can influence tumor development and contribute to treatment resistance, potentially affecting the accuracy of clinical diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment planning. While multiomics technologies now provide comprehensive mapping of ITH at multiple molecular levels, there are ongoing challenges with applying these findings clinically.

ITH is a major mechanism conferring resistance to most targeted drugs because cancer cells of a given tumor are usually composed of a mixed population with diverse clonal or subclonal genetic structures.