1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide, with 2.3 million new cases detected in 2020 – 11.7% of total new cancer cases [

1]. It is the fifth leading cause of death worldwide, having been responsible for 685,000 deaths in 2020 [

1]. In women, it is the most common type of cancer and the leading cause of cancer death worldwide [

1]. In Portugal, breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed type of cancer in women, with an incidence of around 118 per 100,000 inhabitants and a mortality rate of 18.2 per 100,000 inhabitants [

2].

In the US, as in Europe, there has been an increasing trend in breast cancer incidence. This trend reflects, on the one hand, an increase in case detection due to organized screening programs. On the other hand, changes in lifestyle (smoking, alcohol intake, obesity and sedentarism) and in reproductive patterns (early menarche, late menopause, advanced age at first birth, lower breastfeeding rate, use of hormone replacement therapy during menopause, use of oral contraceptives) constitute known risk factors for the development of breast cancer [

1].

Organized screening for breast cancer has been implemented in a large number of countries worldwide since 1990, with mammography being the most widely used diagnostic method and the only one that showed efficacy in reducing mortality [

3]. However, these programs have been the subject of much debate. One of the points of non-consensus is the definition of the target age group for screening, namely its lower age limit [

4].

Currently, the Council of the European Union advocates breast cancer screening from the age of 50 to the age of 69, every two years. A lower age limit of 45 years and an upper age limit of 74 years is suggested, with Portugal altering its guidelines accordingly in March 2025 [

5,

6].

In 2014, the Canadian National Breast Screening Study found no evidence that screening women aged 40 to 49 had an impact on breast cancer mortality after 25 years of follow-up [

6]. This study was the first to estimate an overdiagnosis of breast cancer associated with organized annual screening programs: 1 in every 424 women who received mammography screening, resulting in overtreatment, consequent toxicity and treatment sequelae, compromising the patient’s quality of life and mental health [

6]. On the other hand, in 2015, the American Cancer Society modified its recommendations, advising women to have a mammogram annually from the age of 45 [

7]. In 2017, the American College of Radiology and the Society of Breast Imaging issued new guidelines recommending that screening begins at age 40 [

8]. More recently, in 2020, the UK Age Trial reported that annual mammography screening starting at age 40 was associated with a significant reduction in mortality from breast cancer in the first 10 years of follow-up [

9]. Other studies conducted in Canada and Sweden also demonstrated that screening women between the ages of 40 and 49 reduced mortality from breast cancer by 30% [

10].

In fact, according to the U.S. Surveillance and Epidemiology data, about 18% of breast cancers occur in women aged 40 to 49, with 23% occurring in women aged 50 to 59, 26% in women aged 60 to 69, and 28% in women aged 70 and older [

11]. In Europe, it is estimated that 21% of breast cancer cases occur in women under 50 years of age and 35% occur in women aged 50–64 years [

12]. These data demonstrate that there is currently no abrupt increase in the incidence of breast cancer at age 50. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that tumors diagnosed before the age of 50 generally progress faster, are more likely to be estrogen receptor-negative and present less favorable histological grades, with a worse prognosis [

13,

14].

Considering the controversy surrounding the current screening methodologies and the growing knowledge of the risk factors associated with breast cancer, researchers have been seeking to individualize screening, namely with the implementation of a user-centered model [

15]. Tools that integrate clinical information relating to individual risk predictors and epidemiological characteristics of breast cancer have been developed. The

Tyrer-Cuzick™ risk assessment is one of the most sensitive models for estimating 10-year and lifetime risk of developing breast cancer [

16]. The

Tyrer-Cuzick™ score considers several risk factors, namely age, biometric data, personal and family history of breast or ovarian cancer, previous breast biopsy results, age at menarche, age at first pregnancy, age at menopause and history of hormone therapy use. A score of 15 to 19% indicates an intermediate risk of developing breast cancer, while a score above 20% represents a risk considered high [

16].

This personalized approach involves assessing the individual risk of each woman, stratifying the population into several risk groups, and adapting prevention and early detection interventions to each of these risk groups [

15]. Thus, evolving towards a user-centered model could address the limitations of current screening, increase the sensitivity and specificity of breast cancer screenings, and improve the risk-benefit balance associated with screening [

15,

17].

Here we aimed to investigate relevance of defining a new lower age limit for breast cancer screening, characterize risk factors not included in the Tyrer-Cuzick™ risk assessment calculator, and explore the feasibility of personalizing screening.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is an observational case-control study, focusing on the 8560 female patients registered at Carvalhido and Prelada Family Health Units. The case group includes female patients of the Units with diagnosed breast cancer, according to the following criteria.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Code “Malignant Neoplasm of Breast” in the records;

Diagnosis of breast cancer between the ages of 40-49;

Diagnosis carried out in the last 10 years.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Diagnosis of breast cancer before 40 years of age or after 50 years of age;

Malignant Neoplasm of Breast codification, without breast neoplasm;

Genetic mutations, namely BRCA 1 and BRCA 2, already known at diagnosis;

Death declared up to the time of data collection.

2.4. Sample Size

The control group consists of a sample of female patients of the Units without a diagnosis of breast cancer. The sample size was calculated using the Epi info® platform, considering the total number of female users without breast cancer registered in the participating Units. The sample selection and recruitment was randomized, with all elements of the population having a uniform probability of belonging to the sample. Only patients aged 40 to 59 years were considered for randomization.

2.5. Sources of Information

We used a public business intelligence program to collect lists of users diagnosed with Breast Cancer, a digital clinical process platform for collecting clinical data, a structured questionnaire applied to users of the sample under study (

Figure S1) and the

Tyrer-Cuzick™ risk assessment model.

2.6. Data Collection

The recruitment process was conducted over a period of 3 months, starting after the approval from the Ethics Committee of the Northern Regional Health Administration. A list of all female users diagnosed with Malignant Breast Neoplasia was acquired, which corresponded to a sample of 228 women. After calculating the sample size and randomly selecting the two samples, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, individually consulting the digital medical records to define the case and control groups.

The variables under study were collected by consulting the patient’s medical records, as well as applying an electronic questionnaire completed by the patient: age, BMI, age at diagnosis, presence of family history of breast or ovarian cancer, age at menarche, contraceptive method, age at the date of the first pregnancy, breastfeeding, smoking and alcohol habits, physical activity and personal history of radiotherapy treatment.

Finally, using the data above, the individual risk of each woman was calculated by applying the Tyrer-Cuzick™ risk assessment model, and subsequently stratifying the sample into several risk groups depending on the resulting score.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data processing was performed using Microsoft Excel® 2020 and Statistical Package for Social Science® software, version 23.0 for Windows®. For descriptive statistical analysis, absolute and relative frequencies were calculated for qualitative variables and measures of dispersion and central tendency (mean, standard deviation) for quantitative variables. In the inferential analysis, the relations between the variables were studied using the Student’s t-test for continuous variables with normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables with non-normal distribution, and the Odds Ratio for discrete variables. The tests were considered statistically significant for a significance level (p-value) less than 0.05 and the confidence interval considered was 95%.

2.8. Ethical Considerations

The present study is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Data confidentiality was guaranteed by researchers at all stages of the process.

Before completing the questionnaire, all users were informed about the objectives of the study and how anonymity was guaranteed. Informed written consent was obtained in duplicate, one copy for the researcher and another copy for the participant.

The data collected is confidential and for exclusive use for this study. To ensure data protection, a list of users has been created which includes the National Health Service number and a sequential identification number. Access to the database is exclusive to researchers and password protected.

The researchers ensure that the data collected in the questionnaire was only used in this research and will not be made available to third parties, thus ensuring both the confidentiality and anonymity of the participants.

This protocol was submitted and approved by the Coordinators of the Units where the study was carried out.

This protocol was submitted and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Northern Regional Health Administration (CE/2023/84).

3. Results

3.1. Group Characterization

Regarding the characterization of the two groups under study (

Table 1), there is no statistically significant difference in age (

p = 0.058).

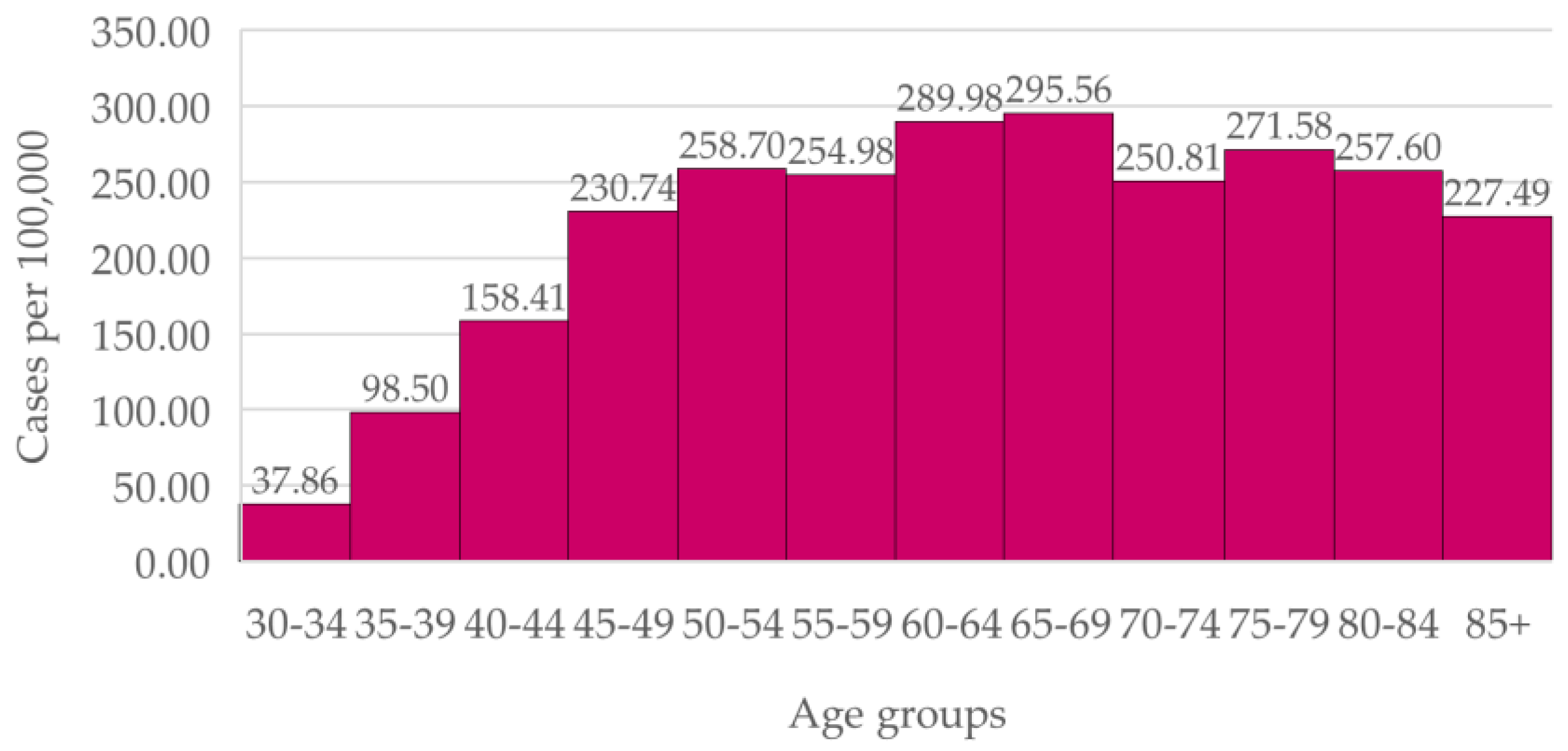

3.2. Breast Cancer Incidence by Age Group

In the overall Portuguese population (

Figure 1), incidence of breast cancer increases with age before reaching a plateau from age 45. The difference between new cases of breast cancer at the ages of 40 to 49 and at the ages of 50 to 69 (the latter being contained in the national screening) is statistically significant (p < 0.0001). However, there is not a statistically significant difference between the age groups of 45 to 49 and 55 to 60 (

p = 0.071).

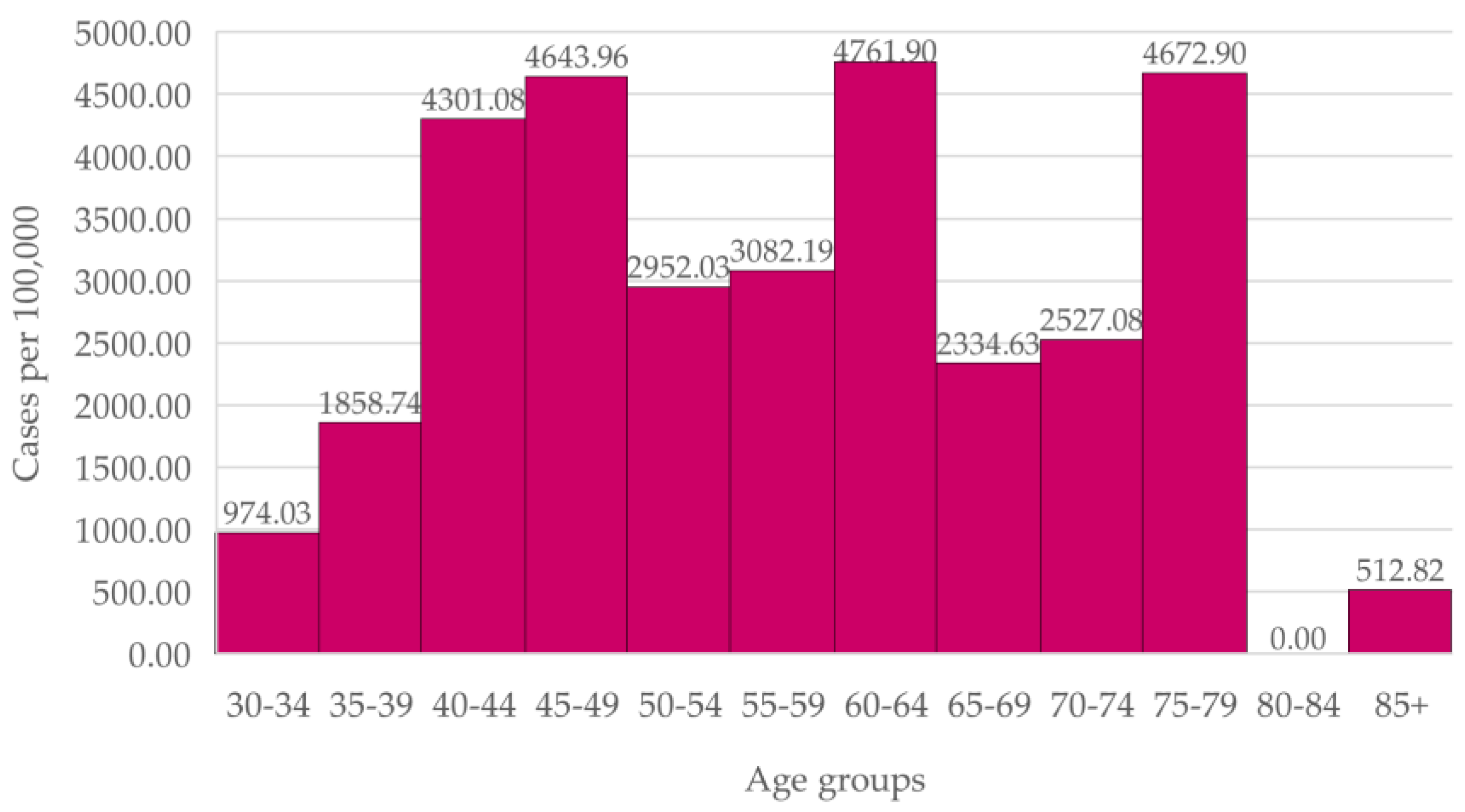

In the Carvalhido Health Unit women (

Figure 2), we observed a higher incidence in the age groups 40-44 and 45-49 than in the 50-54, 55-59 and 65-69 year-old groups. The difference between new cases in the 40-49 ages and in the 50-69 ages, the latter being the age range for screening, is not statistically significant (

p = 0.22).

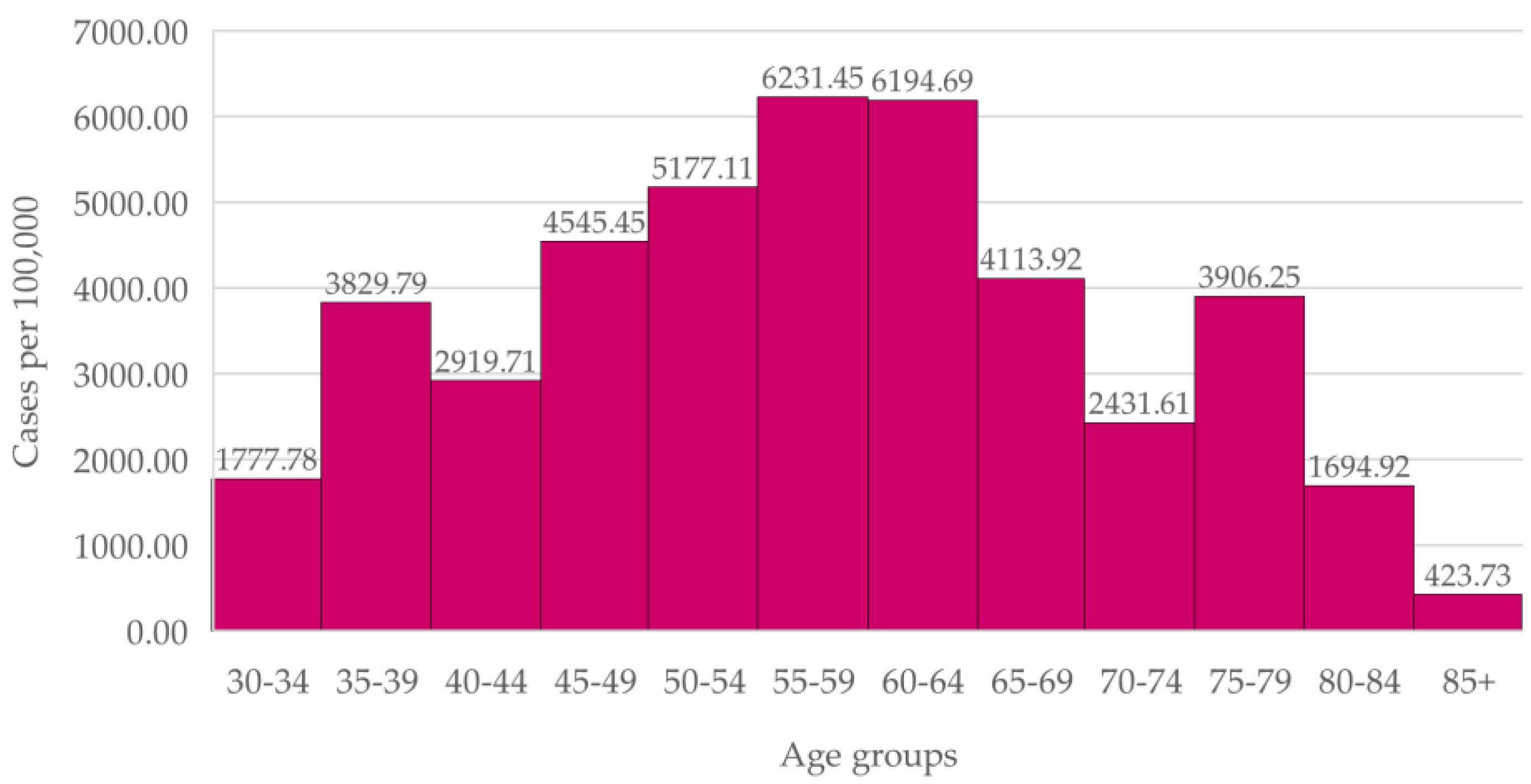

In the Prelada Health Unit women (

Figure 3), incidence in the age group 45-59 is higher than in the 65-69 age group.

The difference between new cases in the 40-49 ages and in the 50-69 ages, the latter being the age range for screening, is not statistically significant (p = 0.1220).

3.3. Risk Factors

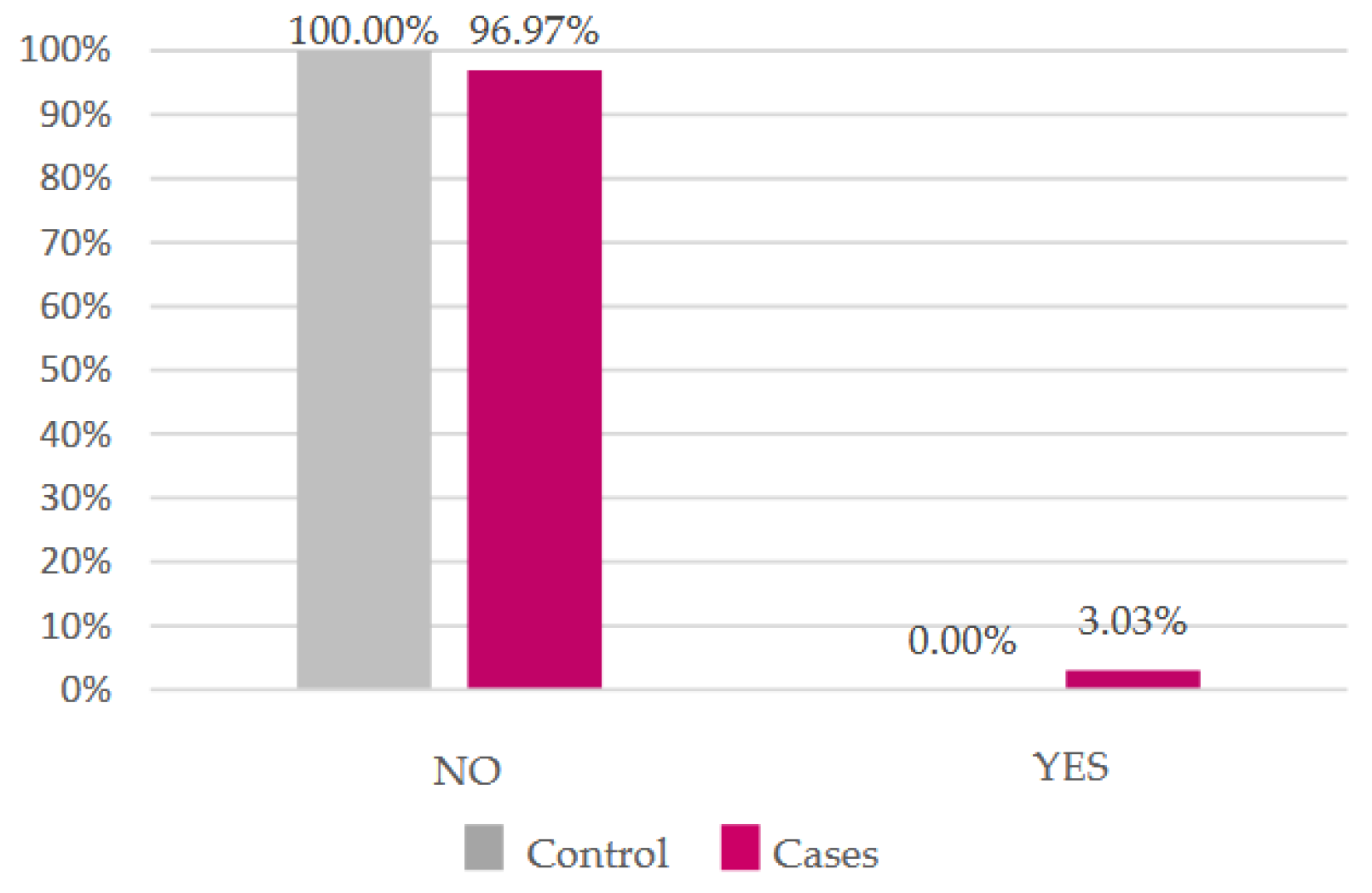

Most of our participants do not smoke, but the proportion of smokers is higher in the case group (

Figure 4). As for alcohol, most women do not drink regularly, however all those who do belong to the case group (

Figure 5). There was no statistically significant difference in either (

p = 0.87 and

p = 0.47, respectively).

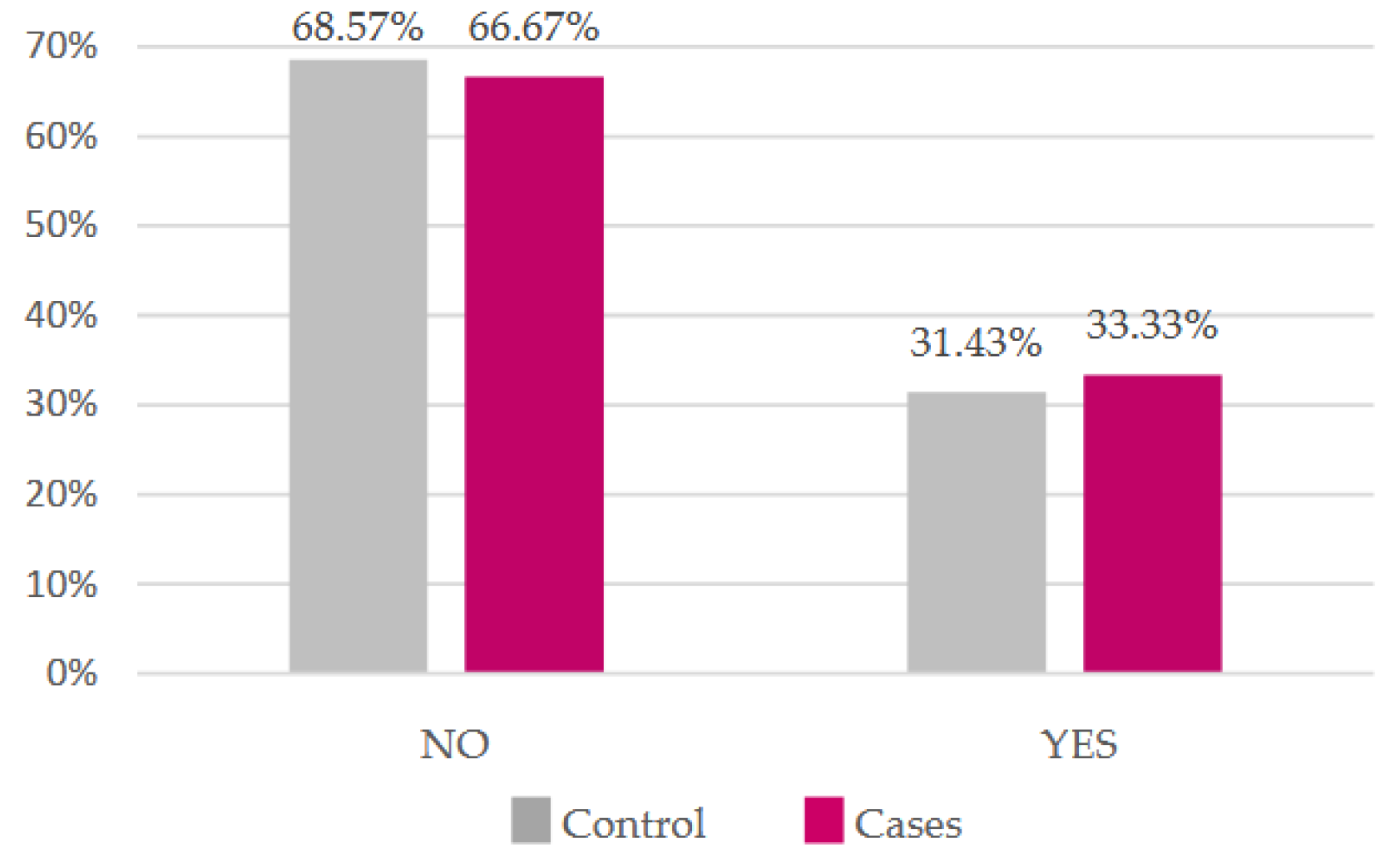

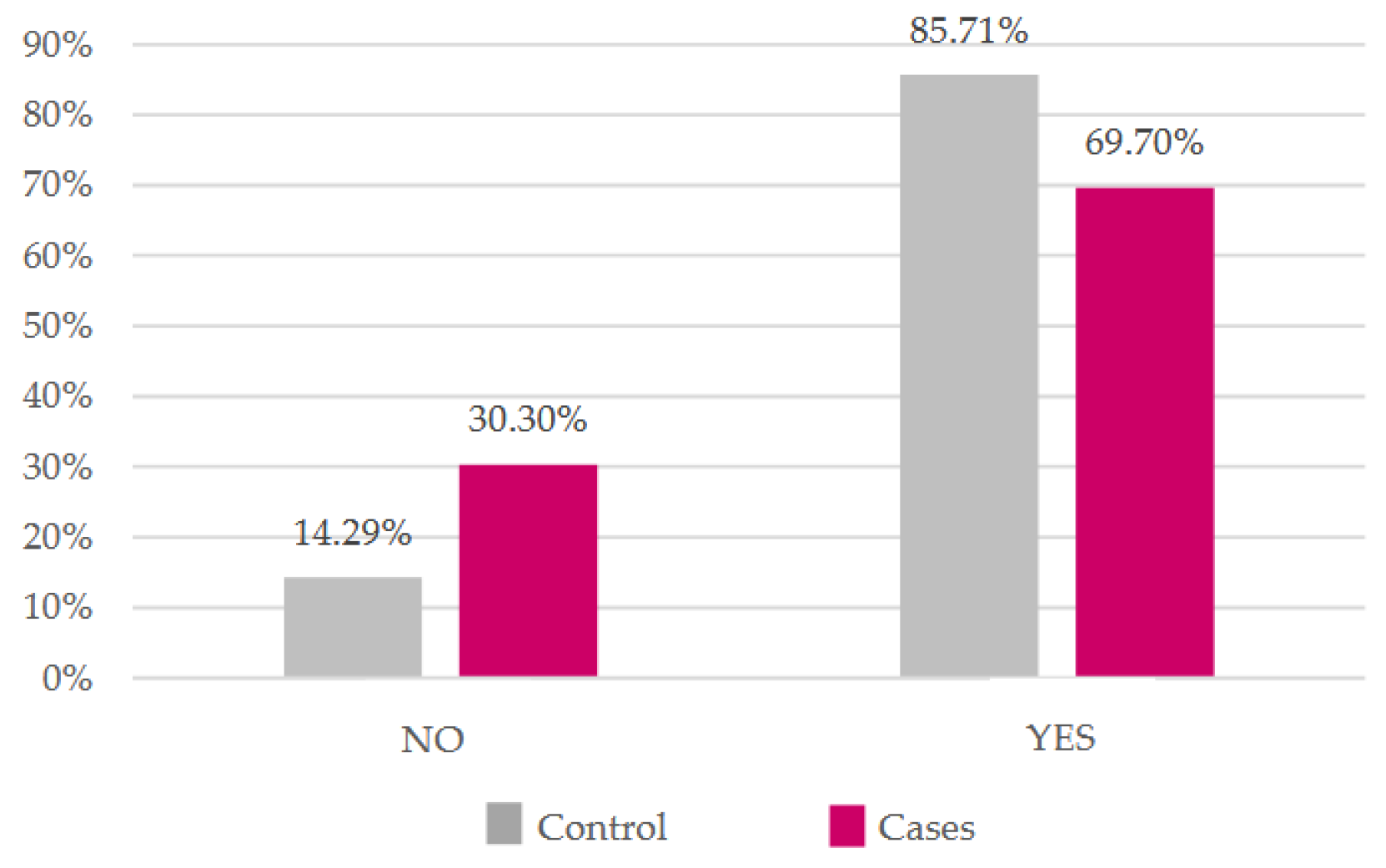

There was a higher percentage of women who breastfed in the control group and a higher percentage of women who did not breastfeed in the case group (

Figure 6), although there was also no evidence of statistical significance (

p = 0.1183).

3.4. Risk Score

Regarding the risk score data (

Table 2), the average 10-year risk is 3.47% in the case group and 2.55% in the control group, while the average lifetime risk is 15.68% in the case group and 11.14% in the control group. Considering these risk scores, 32 of the individuals in the control group were classified as baseline risk and 3 as intermediate or high risk. On the other hand, in the case group, 17 individuals were classified as baseline risk and 16 presented an intermediate or high risk (

Table 3). Thus, a statistically significant positive odds ratio (OR = 10.04,

p = 0.0009) was observed between intermediate-to-high risk scores and breast cancer.

4. Discussion

4.1. Breast Cancer Incidence by Age Group

Breast cancer incidence in women aged 40 to 49 in both Health Units was equal or higher than the incidence in women within the screening age range. In the overall Portuguese population, breast cancer incidence increases with age before plateauing from age 45.

These data shows no abrupt increase in breast cancer incidence at age 50. However, in the Portuguese population, we found a statistically significant difference between breast cancer incidence in the 40-49 and in the 50-69 groups, possibly due to reduced medical following in the national population, compared to the patients of the Family Units. Nonetheless, we found age groups contained in the screening age range with a similar incidence to the 45-49 group. Altogether, this evidence raises the possibility of lowering the minimum screening age to 45, alike the new Portuguese screening program, or to 40 years, the latter being in accordance to the American College of Radiology and the Society of Breast Imaging and the UK Age Trial recommendations [

8,

9].

4.2. Risk Factors and the Tyrer-CuzickTM Calculator

Regarding breast cancer risk factors, though the

Tyrer-CuzickTM model is currently the tool that includes the largest number of established breast cancer risk factors [

19], smoking habits, regular alcohol consumption and breastfeeding (the latter being a known protective factor against breast cancer [

20]) are not considered in the score. We could not find a statistically significant relationship between these risk factors and the diagnosis of breast cancer at an age of 40 to 49 years.

We also observed that the calculator presents 49% of sensibility and 91% of specificity, which translates to a reduced number of false positives, diminishing overdiagnosis, but a large number of false negatives, which is undesirable for a screening method.

Nonetheless, as the Tyrer-Cuzick™ risk assessment calculator does not consider important variables such as the risk factors previously discussed, we wonder if more risk and protective factors linked to the development of breast cancer were added to the calculator, greater sensitivity would be achieved. This hypothesis supports the need of further investigation in this area.

4.3. Tyrer-CuzickTM Risk Assessment Score and Breast Cancer Development

The relationship between a high-risk score in the

Tyrer-CuzickTM model and the development of breast cancer has been described in previous studies, in which the age range of the studied population was either broad [

21,

22] or restricted to postmenopausal women [

23]. Our work focuses on women aged 40-49, and we found a statistically significant relation between an individualized risk score considered intermediate to high at the age of 40-49 and the development of breast cancer.

These results specifically support the applicability of an individualized patient-centered model in screening of women from the age of 40. Furthermore, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines in the U.S. advise that women with a risk considered high should undergo breast magnetic resonance imaging and genetic counseling [

16], empathizing the importance of calculating risk scores in our practice to adapt the course of action and improve prognosis.

4.4. Study Strengths

This study approaches a present-day theme under discussion, in light of the new recommendations included in the European plan to combat cancer presented by the European Commission. It is the first application of the Tyrer-Cuzick™ risk assessment calculator for individual assessment of breast cancer in Portugal, at the time it was carried out. The results of the study may serve as a basis for the implementation of strategies aimed at improving breast cancer screening programs and for carrying out other larger studies. Additionally, our results may lead to potential health gains from increased early detection of breast cancer.

4.5. Study Limitations

Our study is limited by potential biases, namely a classification bias, as some participants of the control group may develop breast cancer before age 50, and a recall bias, as data was collected retrospectively. Additionally, the Tyrer-Cuzick™ risk model considers variables for which information from the user was not obtained, namely Ashkenazi progeny. However, we believe this was mitigated by the large information regarding risk factors and family history contained in the questionnaire. Finally, the results of the study could serve as a basis for the implementation of strategies that may contribute to the increase in the overdiagnosis of breast cancer. However, as previously mentioned, we observed that the calculator has a 91% specificity. Altogether, we consider that the limitations identified do not compromise the conclusions of the study.

4.6. Future Perspectives

Considering the high breast cancer incidence before the age of 50, if these results are upheld in larger studies, we would have support to extend screening programs to women from the age of 40 with and individualized approach.

In order to achieve this, we should focus on developing a predictive risk model that integrates more known risk factors for breast cancer, as a high sensitivity is required in a proper screening program.

5. Conclusions

This study observed a high breast cancer incidence in women aged 40-49 years and a statistically significant relation between an intermediate to high Tyrer-Cuzick™ individualized risk score and the development of breast cancer in these women. The findings of this study support the discussion on lowering the starting age for breast cancer screening, as they suggest a relevant incidence among younger women, being in accordance with the new Portuguese screening program. However, these results should be interpreted with caution, as they do not in themselves provide sufficient evidence to justify a generalized change in screening policy without further large-scale studies and cost-effectiveness analyses. Our obtained results also support the applicability of an individualized patient-centered model in screening of women from the age of 40, given that the screening tool would have high sensibility. A more individualized approach to screening could also contribute to improving the risk-benefit balance of breast cancer screening, though risk tools currently available should be modified in order to increase sensibility.

Until a more sensitive individualized screening tool is available, these findings support the extension of the screening age range.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Questionnaire template.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I.L., D.C.B., A.L.; methodology, M.I.L., S.T., D.B.; validation, M.I.L..; formal analysis, A.B.S., A.L; investigation, M.I.L.; S.T., D.B.; data curation, M.I.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I.L., S.T., A.B.S., D.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B.S., D.C.B., A.L.; supervision, D.C.B, A.L.; project administration, M.I.L.; funding acquisition, M.I.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Liga Portuguesa Contra o Cancro (LPCC) and Agência de Investigação Clínica e Inovação Biomédica (AICIB), in the context of the medical research grant LPCC AICIB 2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Northern Regional Health Administration (protocol code CE/2023/84 and date of approval of 09.11.2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical concerns, as the data involves human subjects.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2021, 71, 209-249. [CrossRef]

- Direção Geral da Saúde. Programa Nacional para as Doenças Oncológicas. Direção Geral da Saúde 2017.

- Autier, P.; Boniol, M. Mammography screening: A major issue in medicine. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 90, 34–62. [CrossRef]

- Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jørgensen, K.J. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD001877. [CrossRef]

- The Council Of The European Union. Council Recommendation of 9 December 2022 on strengthening prevention through early detection: A new EU approach on cancer screening replacing Council Recommendation 2003/878/EC 2022/C 473/01. Official Journal of the European Union 2022.

- Liga Portuguesa Contra o Cancro. Programa de Rastreio de Cancro da Mama - Rastreio e Diagnóstico Precoce. Liga Portuguesa Contra o Cancro 2025.

- Miller, A.B.; Wall, C.; Baines, C.J.; Sun, P.; To, T.; Narod, S.A. Twenty five year follow-up for breast cancer incidence and mortality of the Canadian National Breast Screening Study: Randomised screening trial. BMJ 2014, 348, g366. [CrossRef]

- Oeffinger, K.C.; Fontham, E.T.H.; Etzioni, R.; Herzig, A.; Michaelson, J.S.; Shih, Y.-C.T.; Walter, L.C.; Church, T.R.; Flowers, C.R.; LaMonte, S.J.; et al. Breast Cancer Screening for Women at Average Risk. JAMA 2015, 314, 1599–1614. [CrossRef]

- Mainiero, M.B.; Lourenco, A.; Mahoney, M.C.; Newell, M.S.; Bailey, L.; Barke, L.D.; D’oRsi, C.; Harvey, J.A.; Hayes, M.K.; Huynh, P.T.; et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria Breast Cancer Screening. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2016, 13, R45–R49. [CrossRef]

- Duffy, S.W.; Vulkan, D.; Cuckle, H.; Parmar, D.; Sheikh, S.; A Smith, R.; Evans, A.; Blyuss, O.; Johns, L.; O Ellis, I.; et al. Effect of mammographic screening from age 40 years on breast cancer mortality (UK Age trial): final results of a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1165–1172. [CrossRef]

- Feig, S.A. Screening Mammography Benefit Controversies. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 2014, 52, 455–480. [CrossRef]

- Seely, J.; Alhassan, T. Screening for Breast Cancer in 2018—What Should We be Doing Today? Curr. Oncol. 2018, 25, 115–124. [CrossRef]

- System, E.-E.C.I. Series of Cancer Factsheets in EU-27 countries. European Commission Information System 2020.

- Schünemann, H.J.; Lerda, D.; Quinn, C.; Follmann, M.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Rossi, P.G.; Lebeau, A.; Nyström, L.; Broeders, M.; Ioannidou-Mouzaka, L.; et al. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis: A Synopsis of the European Breast Guidelines. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, 46–56. [CrossRef]

- TabÁR, L.; Chen, H.-H.; Fagerberg, G.; Duffy, S.W.; Smith, T.C. Recent Results From the Swedish Two-County Trial: The Effects of Age, Histologic Type, and Mode of Detection on the Efficacy of Breast Cancer Screening. JNCI Monogr. 1997, 1997, 43–47. [CrossRef]

- Pashayan, N.; Antoniou, A.C.; Ivanus, U.; Esserman, L.J.; Easton, D.F.; French, D.; Sroczynski, G.; Hall, P.; Cuzick, J.; Evans, D.G.; et al. Personalized early detection and prevention of breast cancer: ENVISION consensus statement. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 687–705. [CrossRef]

- Himes, D.O.; Root, A.E.; Gammon, A.; Luthy, K.E. Breast Cancer Risk Assessment: Calculating Lifetime Risk Using the Tyrer-Cuzick Model. J. Nurse Pr. 2016, 12, 581–592. [CrossRef]

- Brentnall, A.R.; Cuzick, J. Risk Models for Breast Cancer and Their Validation. Stat. Sci. 2020, 35, 14–30. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Português de Oncologia do Porto Francisco Gentil - EPE. Rastreio Oncológico Nacional de Todos os Tumores na População Residente em Portugal, em 2019. IPO Porto 2022.

- Amir, E.; Freedman, O.C.; Seruga, B.; Evans, D.G. Assessing Women at High Risk of Breast Cancer: A Review of Risk Assessment Models. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010, 102, 680–691. [CrossRef]

- Łukasiewicz, S.; Czeczelewski, M.; Forma, A.; Baj, J.; Sitarz, R.; Stanisławek, A. Breast Cancer—Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Prognostic Markers, and Current Treatment Strategies—An Updated Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 4287. [CrossRef]

- Tyrer, J.; Duffy, S.W.; Cuzick, J. A breast cancer prediction model incorporating familial and personal risk factors. Stat. Med. 2004, 23, 1111–1130. [CrossRef]

- Terry, M.B.; Liao, Y.; Whittemore, A.S.; Leoce, N.; Buchsbaum, R.; Zeinomar, N.; Dite, G.S.; Chung, W.K.; Knight, J.A.; Southey, M.C.; et al. 10-year performance of four models of breast cancer risk: a validation study. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 504–517. [CrossRef]

- Kurian, A.W.; Hughes, E.; Simmons, T.; Bernhisel, R.; Probst, B.; Meek, S.; Caswell-Jin, J.L.; John, E.M.; Lanchbury, J.S.; Slavin, T.P.; et al. Performance of the IBIS/Tyrer-Cuzick model of breast cancer risk by race and ethnicity in the Women’s Health Initiative. Cancer 2021, 127, 3742–3750. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).