Submitted:

01 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

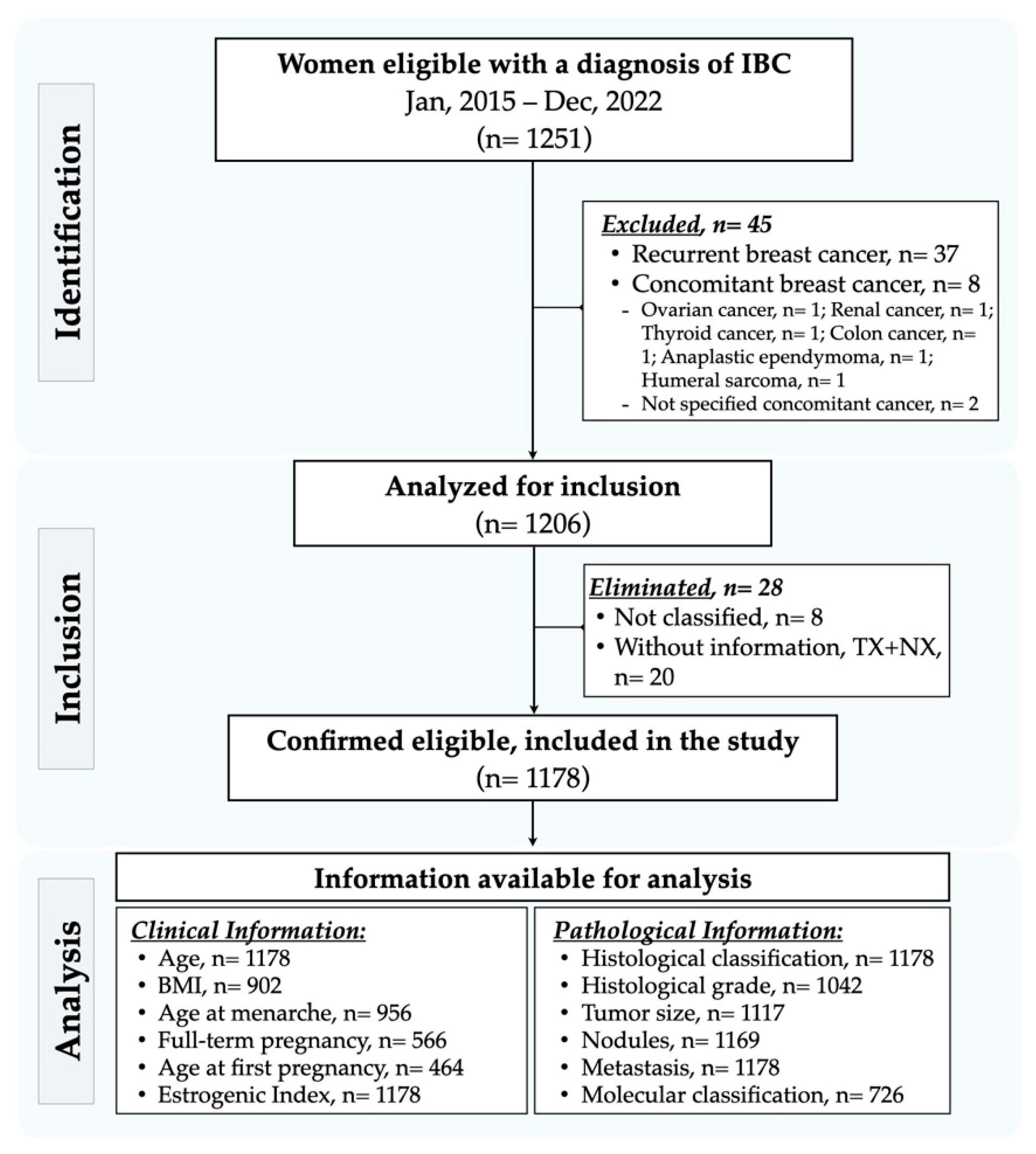

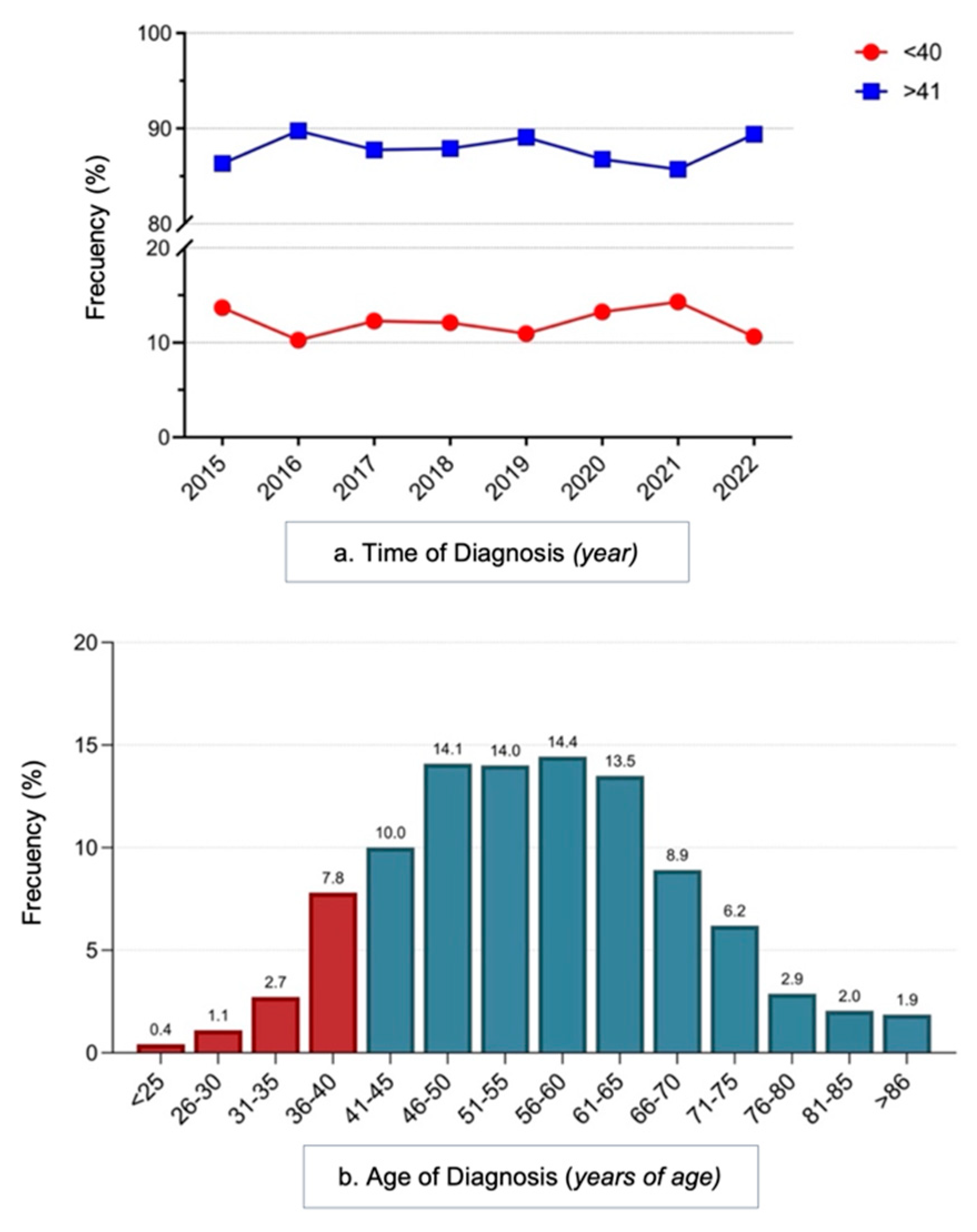

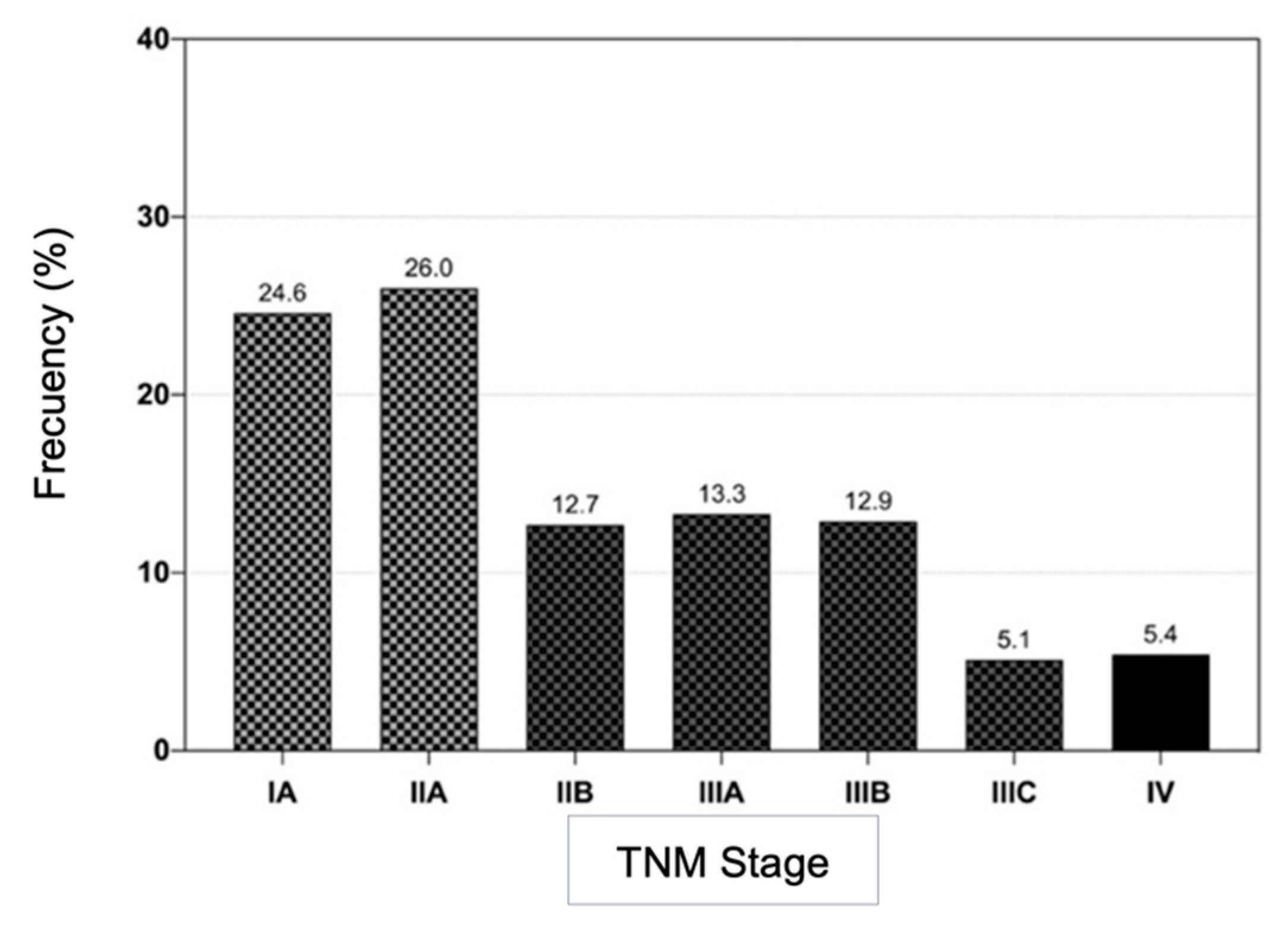

Background: Invasive breast cancer (IBC) is the most prevalent neoplasm and the leading cause of death in women worldwide. Young women under 40 years of age, despite their low incidence, have different clinical-pathological characteristics than older women, giving them a worse prognostic profile. Objective: To determine the association between risk factors associated with MIC in young women in Michoacan. Methods: descriptive, observational, retrospective and cross-sectional study that included 1178 patients < 40 years of age with MIC diagnosed in the period 2015-2022 in a second-level hospital of the IMSS in Michoacán. Sample size at convenience, with database registration, with the use of means, standard deviation, chi-square and Student's t-test, p ≤ 0.05 as an indicator of significance. Registration Number: R-2022-1602-025. Results: of 1178 cases, 12.1% were in young women, who had an increased risk of tumors > 2 cm (p = 0.02, 1.062–2.058), ER–/RP– (p = 0.0067, 1.158–2.501) and triple negative (p = 0.0006; 1.377–5.563). Obesity III was associated with larger tumors (P = 0.0028, 1.051–3.518), advanced TNM stages (P = 0.0445), and greater tissue involvement (T3-T4, P = 0.0301). Conclusions: Breast cancer in young women in Michoacan showed worse prognostic clinical profiles compared to older women.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Pathological and Molecular Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusiones

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Parkin DM, Pineros M, Znaor A, et al. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int J Cancer. 2021;149(4):778–89. Epub 20210405. PubMed PMID: 33818764. [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Salud, DGE. Anuario de Morbilidad 1984 - 2022 México: Secretaría de Salud; 2023 [cited 01/2025 01/2025]. Available from: https://www.gob.mx/salud/acciones-y-programas/anuarios-de-morbilidad-1984-a-2022.

- Rivera-Cruz F. Este año, en Michoacán 238 casos de cáncer de mama y 157 muertes. Gente del Balsas. 2021.

- Cárdenas-Sánchez J, Valle-Solís AA, Arce-Salinas C, Bargalló-Rocha JE, Bautista-Piña V, Cervantes-Sánchez MG, et al. Consenso Mexicano sobre diagnóstico y tratamiento del cáncer mamario. 10 ed. Colima, México. 2023. 266 p.

- INEGI. Estadísticas a propósito del día internacional de la lucha contra el cáncer de mama (19 de octubre). Comunicado de Prensa Núm. 595/23 [Internet]. 2023 [01/2025]. 10/2023:[1–7]. Available from: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/aproposito/2023/EAP_CMAMA23.pdf.

- Moncada-Madrazo M A-GA, Isojo-Gutiérrez R, Issa-Villarreal ME, Elizondo-Granillo C, Ramos-Reyes A. et al Factores de riesgo modificables del cáncer de mama: una comparación entre mujeres menores y mayores de 40 años. Ginecología y Obstetricia de México. 2020;88(3):131-8. [CrossRef]

- Maffuz-Aziz A, Labastida-Almendaro S, Espejo-Fonseca A, Rodriguez-Cuevas S. [Clinical and pathological features of breast cancer in a population of Mexico]. Cir Cir. 2017;85(3):201-7. Epub 20160919. PubMed PMID: 27658545. [CrossRef]

- Alarcon Rojas CA, Alvarez-Banuelos MT, Morales-Romero J, Suarez-Diaz H, Hernandez-Fonseca JC, Contreras-Alarcon G. Breast Cancer: Metastasis, Molecular Subtypes, and Overweight and Obesity in Veracruz, Mexico. Clin Breast Cancer. 2019;19(1):e166-e71. Epub 20180822. PubMed PMID: 30236925. [CrossRef]

- Rocha López AG, Gómez-García A, Montecillo-Aguado M, Sánchez-Ceja SG, Huerta-Yepez S, Gutiérrez-Castellanos S. Risk Factors Associated to Poor Survival in Primary Breast Cancer of Premenopausal and Postmenopausal Patients: A Mexican-Based Population Study. Preprints: Preprints; 2025.

- Reynoso-Noveron N, Villarreal-Garza C, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Arce-Salinas C, Matus-Santos J, Ramirez-Ugalde MT, et al. Clinical and Epidemiological Profile of Breast Cancer in Mexico: Results of the Seguro Popular. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3(6):757-64. Epub 20170208. PubMed PMID: 29244990; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5735969. [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Esparza S, Jansen EC, Hernandez-Avila JE, Zamora-Munoz S, Stern D, Lajous M. Menarche characteristics in association with total and cause-specific mortality: a prospective cohort study of Mexican teachers. Ann Epidemiol. 2021;62:59-65. Epub 20210622. PubMed PMID: 34166807. [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Lima E, Gamboa-Loira B, Cebrian ME, Rothenberg SJ, Lopez-Carrillo L. A cumulative index of exposure to endogenous estrogens and breast cancer by molecular subtypes in northern Mexican women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;180(3):791-800. Epub 20200222. PubMed PMID: 32086656. [CrossRef]

- Tan J, Le A. The Heterogeneity of Breast Cancer Metabolism. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1311(1311):89-101. PubMed PMID: 34014536; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC9703239. [CrossRef]

- Tran TXM, Moon SG, Kim S, Park B. Association of the Interaction Between Mammographic Breast Density, Body Mass Index, and Menopausal Status With Breast Cancer Risk Among Korean Women. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2139161. Epub 20211201. PubMed PMID: 34940866; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8703253. [CrossRef]

- Liu R, Xiao Z, Hu D, Luo H, Yin G, Feng Y, et al. Cancer-Specific Survival Outcome in Early-Stage Young Breast Cancer: Evidence From the SEER Database Analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:811878. Epub 20220118. PubMed PMID: 35116010; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8805172. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Montemayor DF, Orozco-Licona CA. Automated breast ultrasound (ABUS) in asymptomatic young women: an exploratory study. Journal of the Mexican Federation of Radiology and Imaging. 2022;1(4). [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández AG, Ortiz-Mendoza CM. Frequency of mammography use in women insured by the ISSSTE in an urban general hospital. Gaceta Mexicana de Oncolog�a. 2022;18(3). [CrossRef]

- Flores-Diaz D, Arce C, Flores-Luna L, Reynoso-Noveron N, Lara-Medina F, Matus JA, et al. Impact of invasive lobular carcinoma on long-term outcomes in Mexican breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;176(1):243-9. Epub 20190417. PubMed PMID: 30997623. [CrossRef]

- Chen JQ, Russo J. ERalpha-negative and triple negative breast cancer: molecular features and potential therapeutic approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1796(2):162-75. Epub 20090613. PubMed PMID: 19527773; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2937358. [CrossRef]

- Jung AY, Ahearn TU, Behrens S, Middha P, Bolla MK, Wang Q, et al. Distinct Reproductive Risk Profiles for Intrinsic-Like Breast Cancer Subtypes: Pooled Analysis of Population-Based Studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(12):1706-19. PubMed PMID: 35723569; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC9949579. [CrossRef]

- Lee K, Kruper L, Dieli-Conwright CM, Mortimer JE. The Impact of Obesity on Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21(5):41. Epub 20190327. PubMed PMID: 30919143; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6437123. [CrossRef]

- Herr D, Wischnewsky M, Joukhadar R, Chow O, Janni W, Leinert E, et al. Does chemotherapy improve survival in patients with nodal positive luminal A breast cancer? A retrospective Multicenter Study. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0218434. Epub 20190708. PubMed PMID: 31283775; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6613686. [CrossRef]

- Chie WC, Hsieh C, Newcomb PA, Longnecker MP, Mittendorf R, Greenberg ER, et al. Age at any full-term pregnancy and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151(7):715-22. PubMed PMID: 10752799. [CrossRef]

- Hu T, Chen Z, Hou M, Lin K. Overall and cancer-specific survival in patients with breast Paget disease: A population-based study. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2022;247(3):187-99. Epub 20211129. PubMed PMID: 34842487; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8851527. [CrossRef]

- Yadav P, Rathore SS, Verma V, Yadav MK, Sangwan Y. Immunohistochemical profile of carcinoma breast and its association with clinicopathological features: a single institutional experience. International Surgery Journal. 2022;9(4). [CrossRef]

- Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Prat A, Perou CM, Sherman ME. How many etiological subtypes of breast cancer: two, three, four, or more? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(8). Epub 20140812. PubMed PMID: 25118203; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4148600. [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan BN, Ferianto D, Pieter J, Jr. Evaluation of breast cancer metastasis and mortality rates based on molecular subtype: A description study. Breast Dis. 2022;41(1):427-32. PubMed PMID: 36591651. [CrossRef]

| Clinical variables | ≤40 years (n= 142) n/% |

>40 years (n= 780) n/% |

RR (95%CI) | p-value⊥ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age†—years, mean (SD) | 35.8 ± 4.0 | 58.6 ± 11.0 | - | <0.0001* |

| BMI†—kg/m2, mean (SD) | 26.7 ± 4.9 | 29.3 ± 5.4 | - | <0.0001* |

| <18.4 | 4 / 3.3 | 4 / 0.5 | 3.79 (1.61 – 6.23) | 0.0024* |

| 18.5 – 24.9 | 36 / 29.5 | 173 / 22.2 | 1.39 (0.97 – 1.97) | 0.0744 |

| 25.0 – 29.9 | 61 / 50.0 | 296 / 37.9 | 1.53 (1.10 – 2.12) | 0.0114* |

| 30.0 – 34.9 | 14 / 11.5 | 204 / 26.2 | 0.41 (0.24 – 0.69) | 0.0004* |

| 35.0 – 39.9 | 4 / 3.3 | 69 / 8.8 | 0.39 (0.15 – 0.95) | 0.0360* |

| >40 | 3 / 2.5 | 34 / 4.4 | 0.59 (0.20 – 1.57) | 0.3251 |

| Age at Menarche†—years, mean (SD) | 12.3 ± 1.2 | 12.3 ± 1.2 | - | 0.4454 |

| < 10 | 4 / 2.8 | 24 / 2.9 | 0.96 (0.38 – 2.16) | 0.9317 |

| 120 / 84.5 | 671 / 82.4 | 1.14 (0.76 – 1.75) | 0.5461 | |

| > 13 | 18 / 12.7 | 119 / 14.6 | 0.87 (0.55 – 1.35) | 0.5420 |

| Full-term gestations†—no., mean (SD) | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 3.7 ± 2.4 | - | <0.0001* |

| Nulligest | 21 / 22.3 | 58 / 12.3 | 1.77 (1.15 – 2.65) | 0.0102* |

| 1 – 2 | 39 / 41.5 | 138 / 29.2 | 1.56 (1.08 – 2.24) | 0.0193* |

| 3 – 4 | 32 / 34.0 | 167 / 35.4 | 0.95 (0.64 – 1.40) | 0.8039 |

| > 5 | 2 / 2.1 | 109 / 23.1 | 0.09 (0.02 – 0.32) | <0.0001* |

| Age at 1st gestation†—years, mean (SD) | 21.9 ± 5.4 | 22.3 ± 4.8 | - | 0.1440 |

| < 19 | 29 / 42.0 | 116 / 29.4 | 1.60 (1.03 – 2.45) | 0.0363* |

| 20-34 | 38 / 55.1 | 269 / 68.1 | 0.63 (0.41 – 0.97) | 0.0348* |

| > 35 | 2 / 2.9 | 10 / 2.5 | 1.12 (0.31 – 3.13) | 0.8594 |

| Breastfeeding† —months, mean (SD) | 8.6 ± 8.9 | 9.0 ± 10.7 | - | 0.9187 |

| < 6 | 13 / 34.2 | 66 / 27.4 | 1.32 (0.71 – 2.39) | 0.3855 |

| ≥ 6 | 25 / 65.8 | 175 / 72.6 | 0.76 (0.42 – 1.41) |

| Pathological variables | ≤40 years (n= 142) n/% |

>40 years (n= 780) n/% |

RR (95%CI) | p-value⊥ | Total (N= 1178) n/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size† — cm, mean (SD) | 3.95 ± 3.04 | 3.53 ± 2.96 | 0.0285* | 3.58 ± 2.97 | |

| < 2 | 45 / 32.8 | 418 / 42.2 | 0.68 (0.48 – 0.96) | 0.0374* | 463 / 41.0 |

| ≥ 2 | 92 / 67.2 | 573 / 57.8 | 1.30 (0.95 – 1.79) | 665 / 59.0 | |

| HG | |||||

| HG1 | 23 / 18.4 | 164 / 17.9 | 1.03 (0.67 – 1.56) | 0.8879 | 187 / 17.9 |

| HG 2 | 67 / 53.6 | 564 / 61.5 | 0.75 (0.54 – 1.05) | 0.0898 | 631 / 60.6 |

| HG 3 | 35 / 28 | 189 / 20.6 | 1.42 (0.99 – 2.02) | 0.0592 | 224 / 21.5 |

| Tumor TNM | |||||

| T1–T2 | 98 / 71.5 | 742 / 74.1 | 0.89 (0.63 – 1.26) | 0.5173 | 840 / 73.8 |

| T3–T4 | 39 / 28.5 | 259 / 25.9 | 1.12 (0.79 – 1.58) | 298 / 26.2 | |

| Nodules TNM† — no. , mean (SD) | 3.1 ± 4.5 | 2.4 ± 4.0 | 0.0142* | 4.75 ± 4.53 | |

| N0 | 55 / 41.4 | 441 / 48.7 | 1.77 (1.15 – 2.65) | 0.0102* | 496 / 47.8 |

| NI | 42 / 31.6 | 241 / 26.6 | 1.56 (1.08 – 2.24) | 0.0193* | 283 / 27.3 |

| NII | 28 / 21.1 | 161 / 17.8 | 0.95 (0.64 – 1.40) | 0.8039 | 189 / 18.2 |

| NIII | 8 / 6.0 | 62 / 6.9 | 0.09 (0.02 – 0.32) | <0.0001* | 70 / 6.7 |

| Metástasis TNM | |||||

| M1 | 11 / 7.8 | 51 / 4.9 | 1.51 (0.85 – 2.54) | 0.1576 | 62 / 5.3 |

| M0 | 131 / 92.3 | 985 / 95.1 | 0.66 (0.39 – 1.18) | 1116 / 94.7 | |

| TNM Stage | |||||

| IA– IIA | 63 / 48.1 | 517 / 52.5 | 0.86 (0.62 – 1.18) | 0.3441 | 580 / 52.0 |

| IIB–IIIC | 68 / 51.9 | 468 / 47.5 | 1.17 (0.85 – 1.61) | 536 / 48.0 |

| Molecular Variables | ≤40 years (n= 142) n/% |

>40 years (n= 780) n/% |

RR (95%CI) | p-value⊥ | Total (N= 1178) n/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER† — % | 32. 5 ± 40.3 | 40.7 ± 27.5 | 0.0009* | 72.95 ± 1.53* | |

| ER– | 40 / 43.5 | 173 / 27.3 | 1.85 (1.27 – 2.70) | 0.0014* | 228 / 30 |

| ER+ | 52 / 56.5 | 461 / 72.7 | 0.54 (0.37 – 0.79) | 533 / 70 | |

| PR† — % | 27.8 ± 38.1 | 32.5 ± 38.9 | 0.2895 | 57.82 ± 1.87* | |

| PR– | 41 / 44.6 | 238 / 37.5 | 1.29 (0.88 – 1.88) | 0.1954 | 466 / 61.2 |

| PR+ | 51 / 55.4 | 396 / 62.5 | 0.78 (0.53 – 1.14) | 295 / 38.8 | |

| HR | 0.0388* | ||||

| ER+ / PR+ | 49 / 58.3 | 376 / 59.9 | 0.95 (0.63 – 1.42) | 0.7871 | 446 / 58.6 |

| ER– / PR– | 30 / 35.7 | 158 / 25.2 | 1.55 (1.02 – 2.33) | 0.0393* | 208 / 27.3 |

| ER+ / PR– | 3 / 3.6 | 79 / 12.6 | 0.28 (0.10 – 0.01) | 0.0151* | 87 / 11.4 |

| ER– / PR+ | 2 / 2.4 | 15 / 2.4 | 0.99 (0.28 – 2.98) | 0.9966 | 20 / 2.6 |

| HER2 | |||||

| Positive | 23 / 25.0 | 138 / 21.8 | 1.17 (0.75 – 1.80) | 0.4854 | 166 / 22 |

| Negative | 69 / 75.0 | 496 / 78.2 | 0.86 (0.56 – 1.33) | 588 / 78 | |

| Ki-67† — % | 40.7 ± 27.5 | 33.8 ± 24.9 | 0.0588 | 34.44 ± 1.04* | |

| Positive (>20%) | 51 / 12.7 | 340 / 87.3 | 1.44 (0.85 – 2.49) | 0.1807 | 410 / 70.2 |

| Negative (<20%) | 15 / 8.6 | 151 / 91.4 | 0.69 (0.40 – 1.18) | 174 / 29.8 | |

| Molecular Subtype | |||||

| Luminal A | 43 / 46.7 | 398 / 62.8 | 0.57 (0.39 – 0.83) | 0.0032* | 441 / 59.4 |

| Luminal B | 11 / 12.0 | 78 / 12.3 | 0.97 (0.54 – 1.70) | 0.9246 | 89 / 12.0 |

| HER2 | 12 / 13.0 | 60 / 9.5 | 1.36 (0.77 – 2.30) | 0.2830 | 81 / 10.9 |

| Triple negative | 26 / 28.3 | 98 / 15.5 | 1.91 (1.26 – 2.85) | 0.0023* | 131 / 17.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).