1. Introduction

In the realm of multivariate regression analysis, have you ever found yourself navigating the complex landscape where multiple response variables are documented for each individual or experimental unit? Imagine the interplay of various economic indicators, such as the delicate dance between income and expenditure, or the intricate relationships in biomedical research where systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings are closely intertwined. Similarly, consider environmental metrics like temperature and humidity, whose fluctuations may influence one another in subtle yet profound ways.

In these scenarios, it's striking to observe how the response variables often display a profound statistical dependence, even when we account for the effects of explanatory variables. Ignoring this intricate web of relationships can lead to inefficiencies in estimation, biases in inference, and potentially misleading conclusions regarding the true influence of predictors. Each overlooked connection risks distorting our understanding of the underlying phenomena we seek to unravel.

Traditional regression methods often involve fitting individual univariate models for each response variable. However, these methods typically assume that the responses are conditionally independent given the predictor variables, a premise that is seldom met in real-world scenarios. In practice, correlations between outcomes can stem from various sources, including shared latent factors, common measurement processes, or intrinsic structural relationships among the responses themselves. When such dependencies are present, relying on separate univariate models fails to effectively represent the complex joint behavior of the responses. Consequently, the marginal predictions produced may not align with realistic joint distributions, leading to potentially misleading conclusions.

To overcome this limitation, copula-based regression presents a flexible and theoretically robust framework for modeling the joint distribution of multiple responses, while simultaneously maintaining distinct regression models for each marginal distribution. Sklar's theorem provides a foundational framework for understanding multivariate distributions by allowing them to be expressed as a combination of their marginal distributions and a copula function. This copula function serves to describe the dependence structure among the different variables. By utilizing this decomposition, researchers can develop tailored regression models for each marginal outcome, potentially employing various families or link functions. Furthermore, the copula effectively captures the strength and nature of the relationships between these outcomes, whether they are symmetric, asymmetric, or exhibit tail dependence, thereby enhancing the analysis of complex data sets.

When two response variables

and

depend on a common predictor

, the parametric copula regression model expresses their conditional joint distribution as

where

and

are the conditional marginal distributions and

is a parametric copula with a dependency parameter

that may itself vary with the predictor

.

This formulation empowers both the marginal behaviors and the strength of association between responses to evolve dynamically in response to predictors. Such adaptability is crucial across a multitude of applications. For example, in the realm of finance, the relationship between asset returns can intensify dramatically during times of market turbulence. In environmental studies, the interplay between rainfall and humidity can vary significantly based on factors like altitude or the changing seasons. In biomedical research, the connection between two biomarkers may fluctuate with age or the prescribed treatment dosage. A copula regression model adeptly captures these intricate, covariate-dependent patterns of dependence in a manner that traditional correlation-based or linear models simply cannot achieve.

The parametric copula framework opens a door to a sophisticated realm of understanding the intricate nature of dependence between variables. By dynamically estimating theta as a function of the predictor, researchers can rigorously test important hypotheses. For instance, one can determine whether the degree of dependence remains stable across all levels of predictor or if it exhibits a tendency to increase or decrease in response to the predictor. This transforms copula regression into more than just a modeling technique; it becomes a powerful inferential framework that illuminates how the relationships between outcomes evolve in tandem with various covariates.

In conclusion, dependence is important because it indicates structural relationships that cannot be fully understood through the predictors alone. Overlooking dependence may lead to an underestimation of uncertainty, skew prediction intervals, and result in inconsistent joint forecasts. The parametric copula regression model offers a coherent approach by enabling distinct, interpretable marginal regressions while also capturing the dependence structure among responses using a well-founded copula function.

Contribution of the study: This study stands apart from earlier research by examining dependence through parametric copulas instead of relying on nonparametric or vine copula methods. This unique approach adds significant value to the work.

Recent developments in multivariate statistics have highlighted the role of copula models, yet much of the existing research has concentrated on static dependence, where the copula parameters are treated as constant. Additionally, there has been a significant focus on high-dimensional vine structures, which are primarily utilized for risk aggregation and portfolio analysis. However, there has been relatively less exploration of copula-based regression models that jointly regress two or more response variables on covariates. Notably, the modeling of the dependence parameter as a function of a predictor offers valuable insights, as it enables researchers to directly interpret how the strength or nature of dependence varies across different levels of the covariate. This approach, while promising, has not been sufficiently examined in applied fields.

In the foundational works of the late 1990s and early 2000s (e.g., Joe, 1997 [

1]), scholars laid the groundwork for understanding conditional copulas and the intricate dynamics of dependence modeling. However, these early theories often faced limitations in their practical applications, typically restricted to specific types of data, including continuous time series and financial returns, which constricted their broader utility. Many authors discussed the rule copula in regression like [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]

Recent advancements in statistical modeling, particularly in copula regression, have been significantly influenced by the pioneering research conducted by Hans in 2023[

3] and Klein in 2019 [

21]. Their innovative work has expanded the boundaries of copula regression, integrating both distributional and boosted frameworks that adapt dynamically to varying data conditions. These contemporary methodologies not only enhance the estimation processes for both marginal and copula parameters but also demonstrate impressive flexibility across different contexts. However, despite the evident sophistication and potential of these advanced techniques, they often require the implementation of complex computational algorithms, which can be challenging to navigate. Additionally, they typically necessitate large sample sizes to yield reliable results. This reliance on robust data sets may inadvertently create barriers for practitioners who are working with smaller datasets, limiting the accessibility and applicability of these advanced statistical tools in real-world scenarios.

As a result, there is still a pressing need for more straightforward parametric copula regression models—ones that offer clarity and ease of interpretation, making them accessible and practical for those dealing with small to moderate samples while preserving the richness of the underlying statistical relationships.

In this study, the author delves into the innovative realm of parametric copula regression, exploring its application to two interrelated response variables linked through a single-dimensional predictor. This approach skillfully marries the clarity and interpretability of parametric regression with the adaptable capabilities of copula-based dependence modeling, resulting in a powerful analytical framework. The author's contribution unfolds in two significant ways:

1-The author establishes a robust modeling structure in which each response variable is intricately regressed on the predictor via a parametric quantile regression approach. Crucially, the dependence parameter of a selected copula (Gumbel) is elegantly modeled as a parametric function of the same predictor, enriching the understanding of their interrelationships.

2- The author illustrates the model's capacity to unveil varying dependence patterns across the predictor's range. Through meticulous evaluation employing bootstrap-based inference techniques and rigorous goodness-of-fit diagnostics, its performance can be assessed. Furthermore, its interpretability in practical scenarios where conventional multivariate regression methods struggle to capture crucial nuances, such as tail or asymmetric dependence is highlighted.

This comprehensive investigation not only advances methodological rigor but also enhances empirical insights, illuminating the complex tapestry of relationships that lie within our data. It also offers a constructive framework for the analysis of bivariate responses with covariate-dependent dependence by effectively bridging marginal regression models with dependence modeling through a parametric copula structure. By doing so, it enhances our theoretical understanding of regression copulas, while also providing valuable tools for practical applications in fields such as econometrics, environmental modeling, and biostatistics. This approach encourages further exploration and innovation in these areas.

This paper is structured into the following sections. Methodology and mathematical definitions are discussed in section 2. Estimation procedures and diagnostics are clarified in section 3. Real data analysis comprehending the results and the discussion is demonstrated in section 4. Conclusion is illuminated in section 5. Lastly future work is suggested in section 6.

4. Real Data Analysis: Results and Discussion

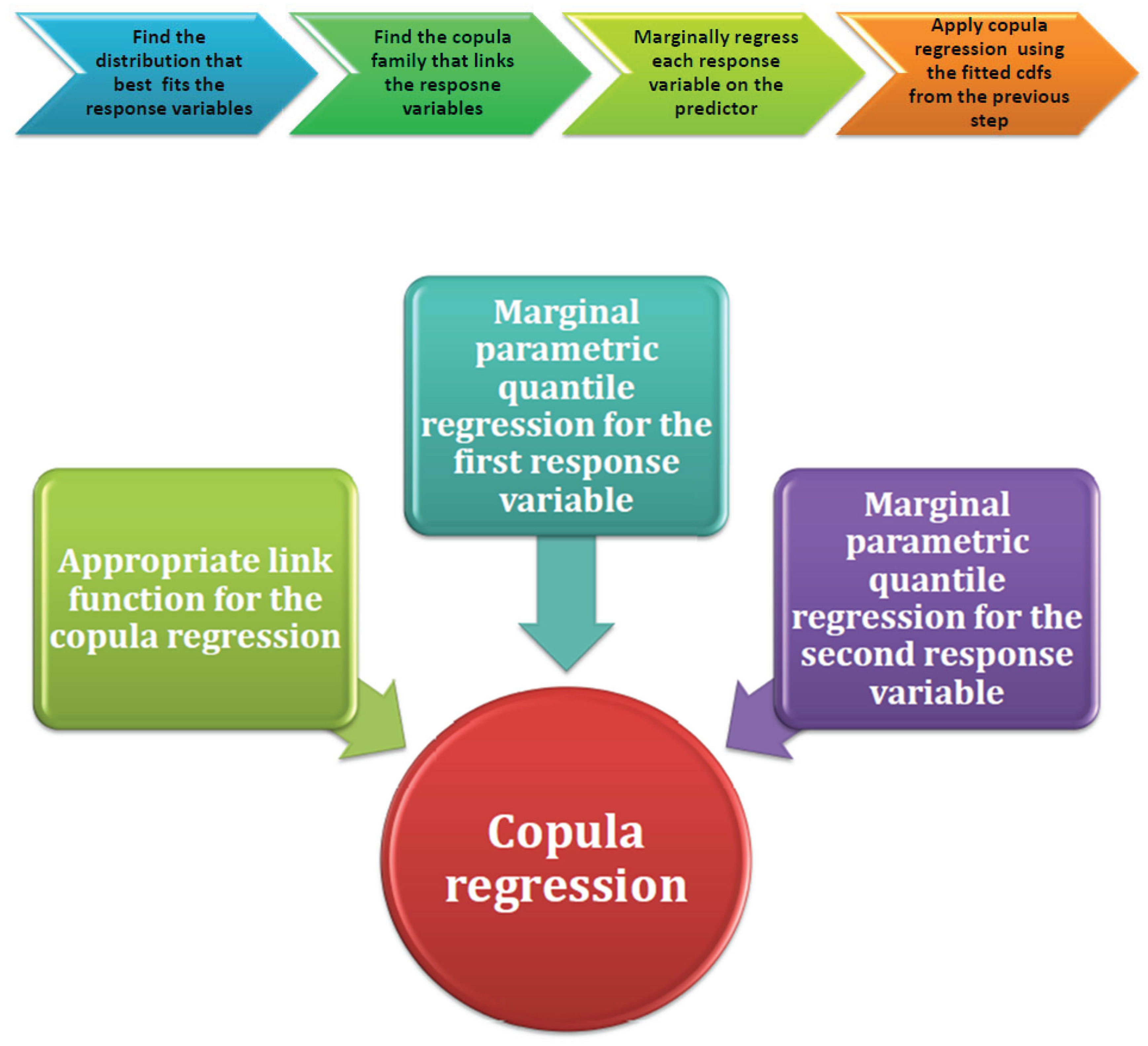

Parametric Quantile Copula regression algorithm steps

Assess the distribution of the two response variables and their fitness.

Assess the fitness of the type of family of copula that links the two variables.

Apply marginal parametric quantile regression: regress each variable on the predictor using the parametric quantile regression and assess the fitness of each marginal quantile regression model then obtain the fitted theoretical CDF for each response variable.

Use these fitted CDFs in the copula regression part of the algorithm (applying the IFM).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data platform located on the following site:

https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=BLI, delivers indicators in different segments such as economy, education, health, labor, trade and creation. The data are collected from 41 countries all over the world. In this manuscript, the author will regress two response variables or indicators; the water quality and the quality of support network on the predictor or the indicator; the life expectancy. The two response variables are distributed as median based unit Rayleigh (MBUR) introduced by Attia [

33]

These illustrated flow diagrams show the steps to follow in applying parametric copula regression model.

The water quality indicator is computed as the self-reported approval with water quality and is signified by the percentage of people who report being satisfied with the quality of water as regards safety and cleanliness. The values of the water quality data are0.92, 0.92, 0.79, 0.9 ,0.62, 0.82, 0.87, 0.89, 0.93, 0.86, 0.97, 0.78, 0.91, 0.67, 0.81, 0.97, 0.8, 0.77, 0.77, 0.87, 0.82, 0.83, 0.83, 0.85, 0.75, 0.91, 0.85, 0.98, 0.82, 0.89, 0.81, 0.93, 0.76, 0.97, 0.96, 0.62, 0.82, 0.88, 0.7, 0.62, 0.72.

The quality of support network indicator measures the availability and reliability of help offered as a social support of friends, family, or community members to individuals who can rely on in time of need, and it is expressed as the percentage of people who report having someone they can count on for this support. The values of the quality support network are0.93, 0.92, 0.9, 0.93, 0.88, 0.8, 0.82, 0.96, 0.95, 0.95, 0.96, 0.94, 0.9, 0.78, 0.94, 0.98, 0.96, 0.95, 0.89, 0.89, 0.8, 0.92, 0.89, 0.91, 0.77, 0.94, 0.95, 0.96, 0.94, 0.87, 0.95, 0.95, 0.93, 0.94, 0.94, 0.85, 0.93, 0.94, 0.83, 0.89, 0.89.

The life expectancy indicator refers to the average number of years a person can expect to live based on current mortality rates and it is represented as a single number expressing the expected lifespan at birth, the values of the life expectancy data are 83, 82, 82.1, 82.1, 80.6, 76.7, 80.5, 79.3, 81.5, 78.8, 82.1, 82.9, 81.4, 81.7, 76.4, 83.2, 82.8, 82.9, 83.6, 84.4, 83.3, 75.5, 76.4, 82.7, 75.1, 82.2, 82.1, 83, 78, 81.8, 77.8, 81.6, 83.9, 83.2, 84, 78.6, 81.3, 78.9, 75.9, 73.2, 64.2.

First Step of Algorithm: The Distribution of the Response Variables.

The 2 response variable are distributed as MBUR with the following PDF , CDF and quantile functions, respectively:

,

and the quantile is

Figure 1 shows the boxplot of the response variables.

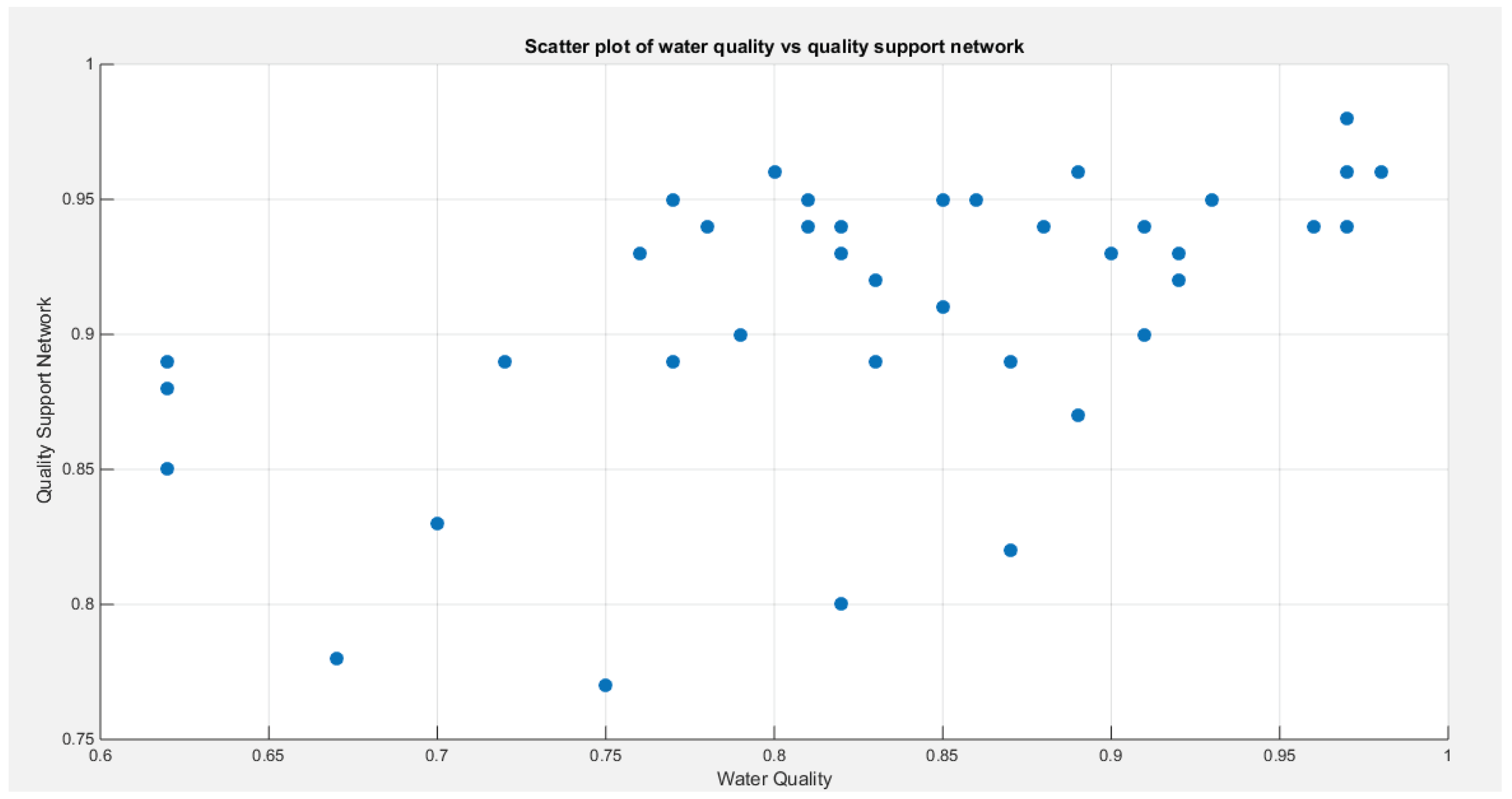

Figure 2 shows the scatter plot between the two response variables.

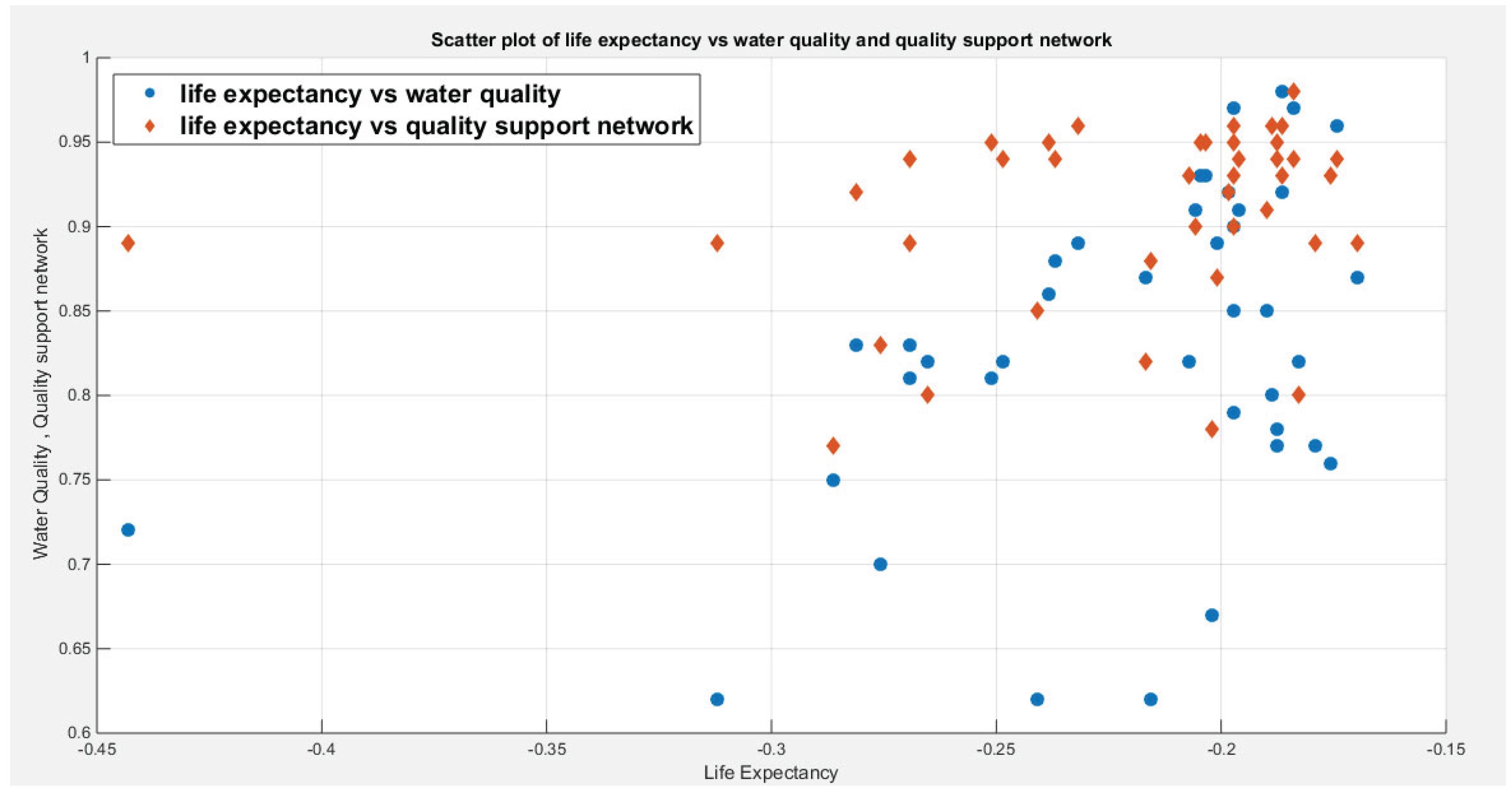

Figure 3 shows the scatter plot between the life expectancy water quality as well as the quality of support network.

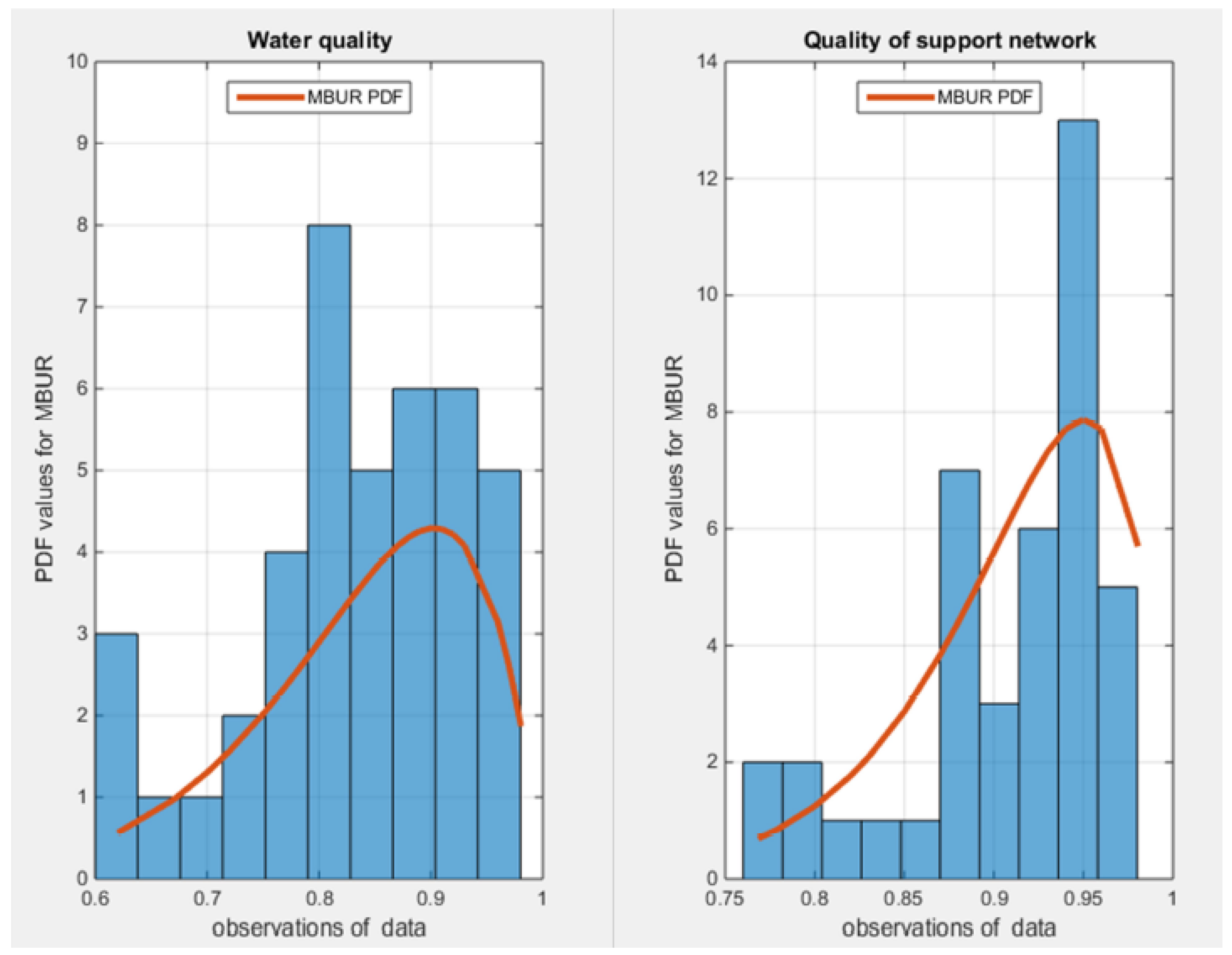

Figure 4 shows the fitted MBUR PDFs for both variables.

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the two response variables.

Table 2 shows the Kendall Tau coefficient between the response variables. And

Table 3 shows the statistical indices of both variables fitting MBUR distribution. The Kendall tau between water quality and life expectancy is 0.2859 and its statistically significant with p-value of 0.0099 while the Kendall tau between the quality of support network and the life expectancy is 0.2079 and it is statistically insignificant as the p-value is 0.0667. Although the distribution of the predictor does not affect the regression model, it is distributed as Kumaraswamy distribution as well as Beta distribution. But Kumaraswamy better fits the data rather than the Beta distribution as it has higher value of the Log-likelihood and more negative values of AIC, CAIC, BIC, and HQIC than the Beta distribution. To conduct the analysis, the predictor was transformed by dividing each value by 100 then taking the log of the result.

Table 1 depicts that the 2 response variables show left skewness that is more obvious for the quality of support network than that of the water quality. The quality of support network shows more leptokurtic shape than the shape of the water quality.

Table 2 illuminates that both variables show significant positive dependence as seen by significant Kendall Tau coefficient

Table 3 highlights that the two variables fit the median based unit Rayleigh as null hypothesis fail to reject the tested MBUR distribution.

Figure 4 shows the histogram and the fitted PDF curves for each response variable.

Second Step of Algorithm: The Copula Family That Links the Response Variables.

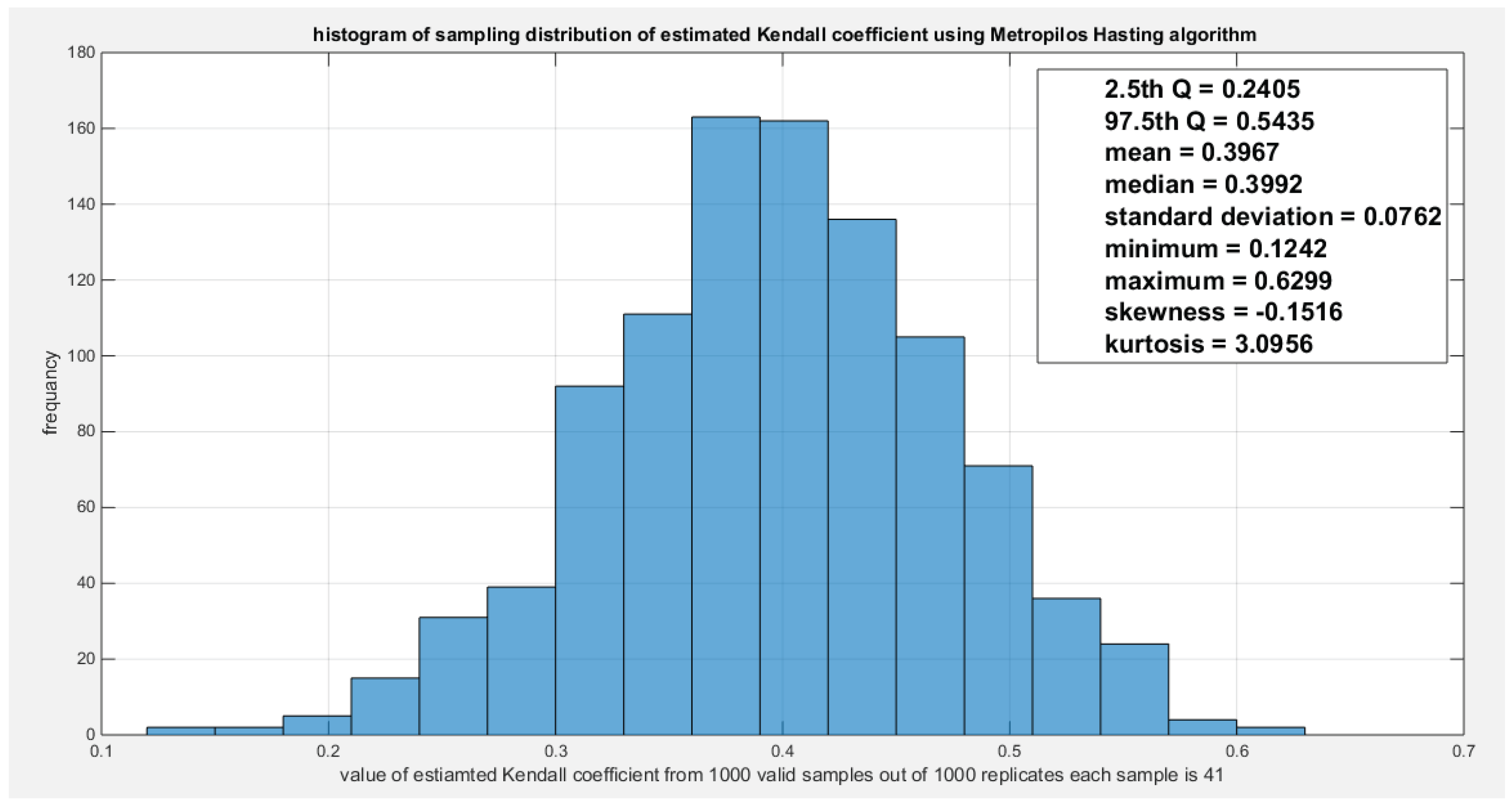

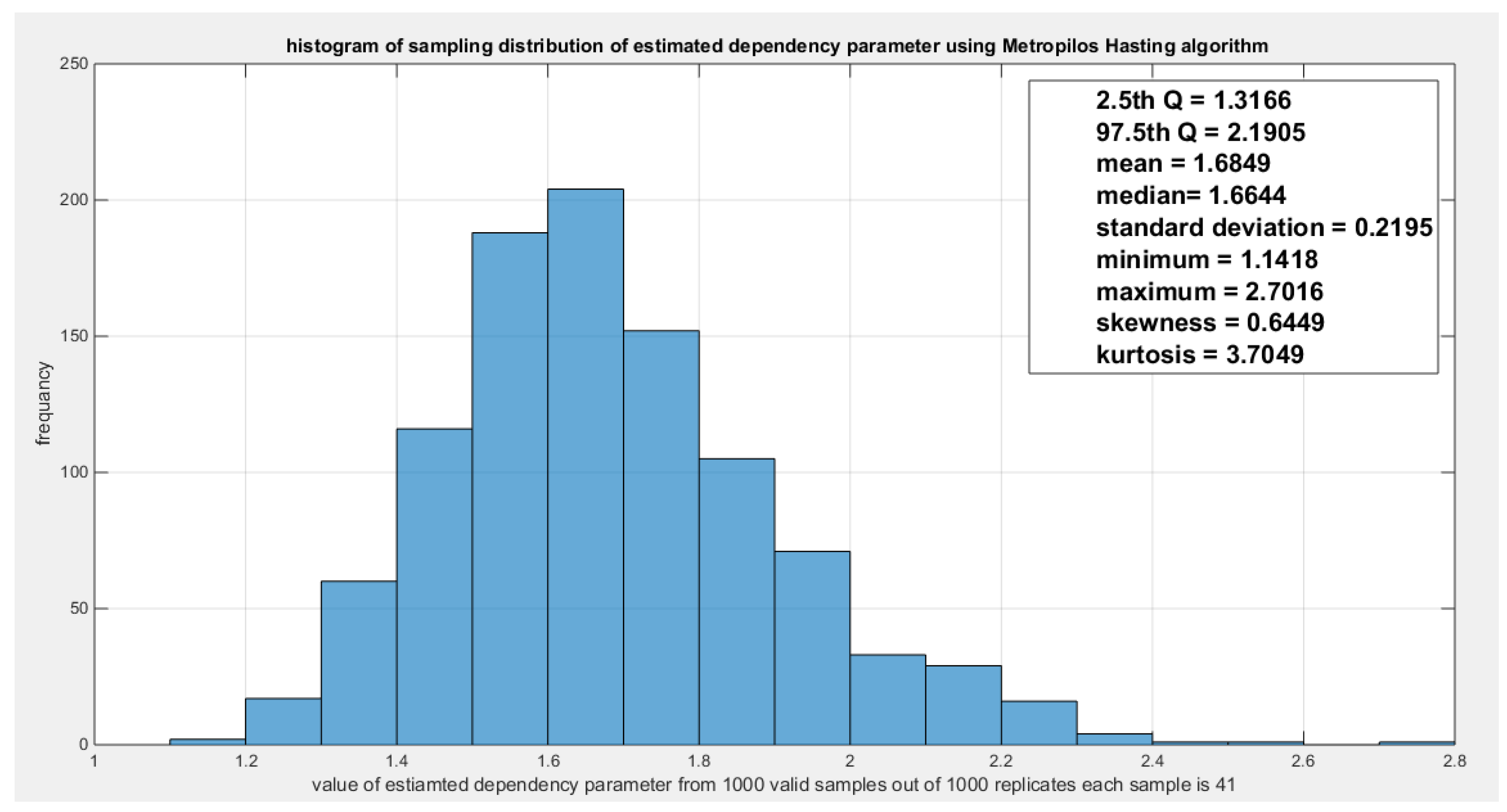

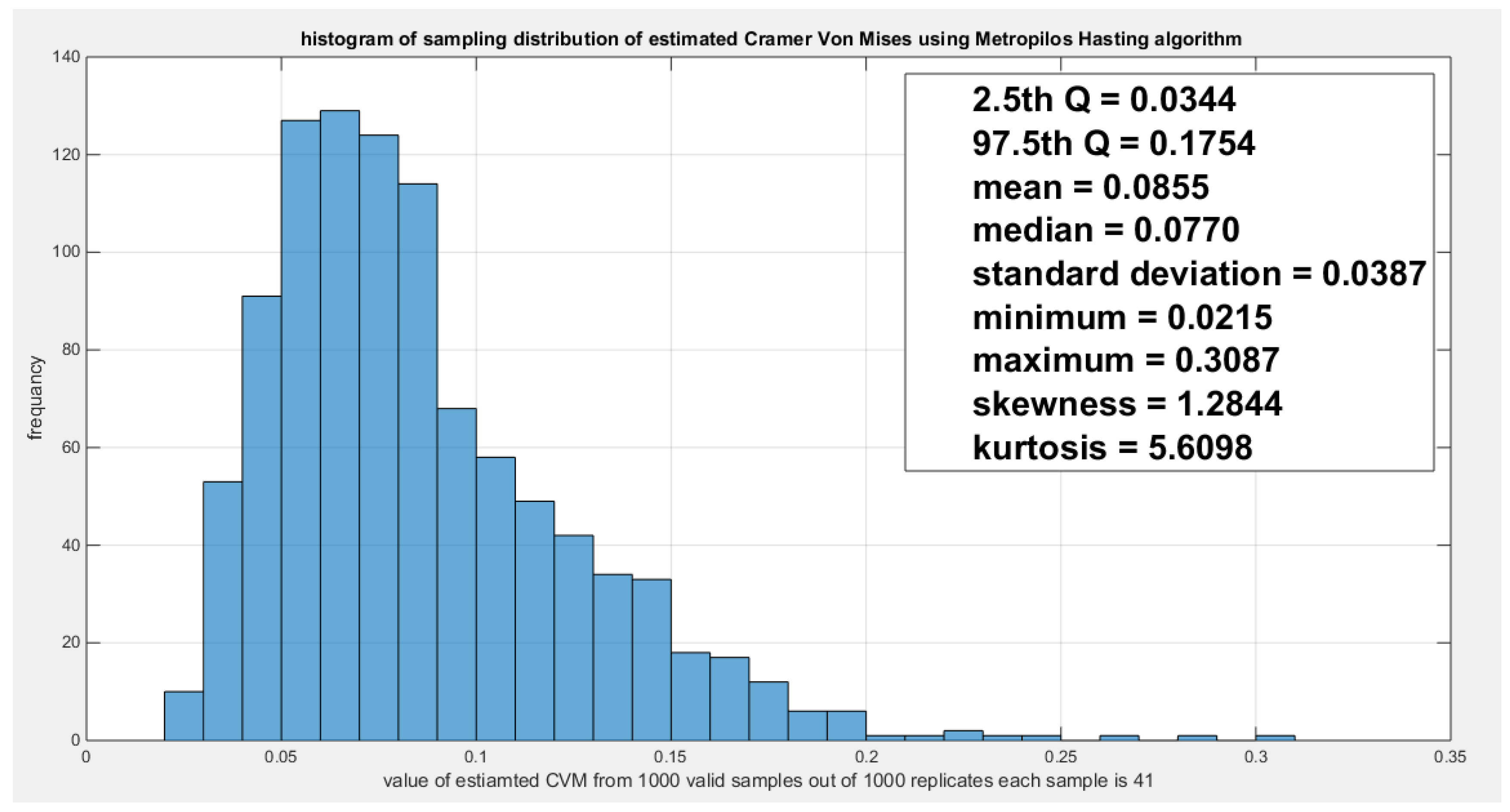

The response variables fit the Gumbel copula family. The theoretical tau is 0.3904 and the estimated dependency parameter is 1.6403. The estimated Cramer Von Mises (CVM) is 0.2154, the

while

. The Log-likelihood is 6.5649. Sampling from the fitted Gumbel copula using the Metropolis Hasting algorithm yielded a sampling distribution of the estimated tau with the 2.5

th and 97.5

th empirical quantiles being 0.2405 and 0.5432 respectively, a sampling distribution of the estimated dependency parameter with 2.5

th and 97.5

th empirical quantiles being 1.3166 and 2.1905 respectively, and a sampling distribution of the estimated CVM with 2.5

th and 97.5

th empirical quantiles being 0.0344 and 0.1754 respectively.

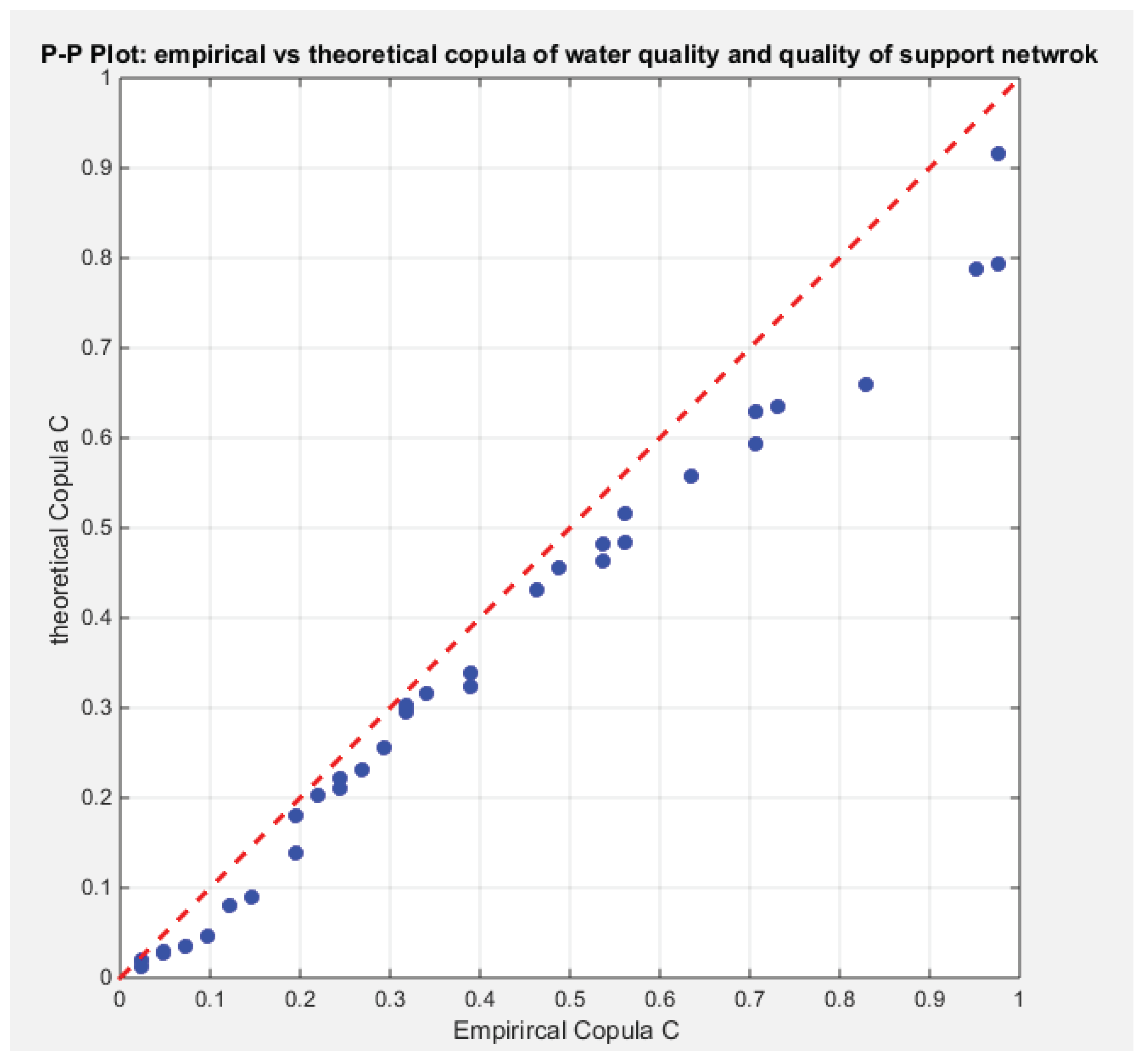

Figure 5 shows the P-P plot of the theoretical vs the empirical Gumbel copula.

Figure 5.

Shows the P-P plot of the empirical copula vs the theoretical copula. The theoretical copula shows near perfect alignment of the lower part and the central part with the diagonal than the upper part.

Figure 5.

Shows the P-P plot of the empirical copula vs the theoretical copula. The theoretical copula shows near perfect alignment of the lower part and the central part with the diagonal than the upper part.

Figure 6.

Shows the sampling distribution of the Kendall Tau coefficient. The estimated tau is 0.3904 and it lies between the 2.5th and 97.5th empirical quantile. The null hypothesis testing the estimated tau is failed to be rejected.

Figure 6.

Shows the sampling distribution of the Kendall Tau coefficient. The estimated tau is 0.3904 and it lies between the 2.5th and 97.5th empirical quantile. The null hypothesis testing the estimated tau is failed to be rejected.

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show the sampling distributions obtained from the Metropolis Hasting algorithm for testing estimated tau, estimated dependency parameter, and the estimated CVM test. And the null hypothesis fails to reject any of the tested estimates. Hence the GoF tests for the Gumbel copula are illustrated and subsequently the two variables fit the Gumbel copula well.

Third Step of Algorithm: The Marginal Parametric Quantile Regression

As the response variables are negatively skewed, the logit link function and the log-log complementary link function can be considered as a good candidate to reparameterize the alpha parameter in the MBUR PDF. Both functions are monotone increasing functions. Hence applying the median parametric regression model to regress the water quality variable on the life expectancy variable as well as regressing the quality of support network on the life expectancy gives estimate of the alpha parameter for each observation. This is called the marginal regression model of each response variable on the predictor. The estimated alpha parameters of the marginal MBUR are utilized to acquire the fitted CDF for each marginal (or variable), these estimated CDF will be utilized in the copula regression part in which the dependency parameter of the Gumbel copula is defined in terms of each observation by the help of a link function that ensure that the dependency parameter is more than one.

Reparameterize the PDF and CDF of MBUR using the quantile function where c is . U represents the chosen percentile, in this analysis the author uses the median so u=0.5 and

As y is the median corresponding to u=0.5 then; replacing this u into the c equation, the c will also be 0.5. Using the logit function of the median which is called

and

where n is the number of cases and k is the number of variables. Logit median is a linear combination of variables.

Replace this parameter in the Log-Likelihood function and the coefficients can be obtained by the MLE, the author used the derivative free algorithm; Nelder Mead simplex optimizer in MATLAB.

A link function other than the logit which is also monotonically increasing is the log-log (1-median) , hence the median is and . The author used the 2 link models and compare between them.

The results of the marginal regression of each of the response variable on the predictor are shown in 2 tables; each table represents the results gained from utilizing a specific link function.

Table 4 shows the results of regressing the response variable on the predictor using the logit link function. While,

Table 5 shows the results of regressing the response variable on the predictor using the log-log complementary link function.

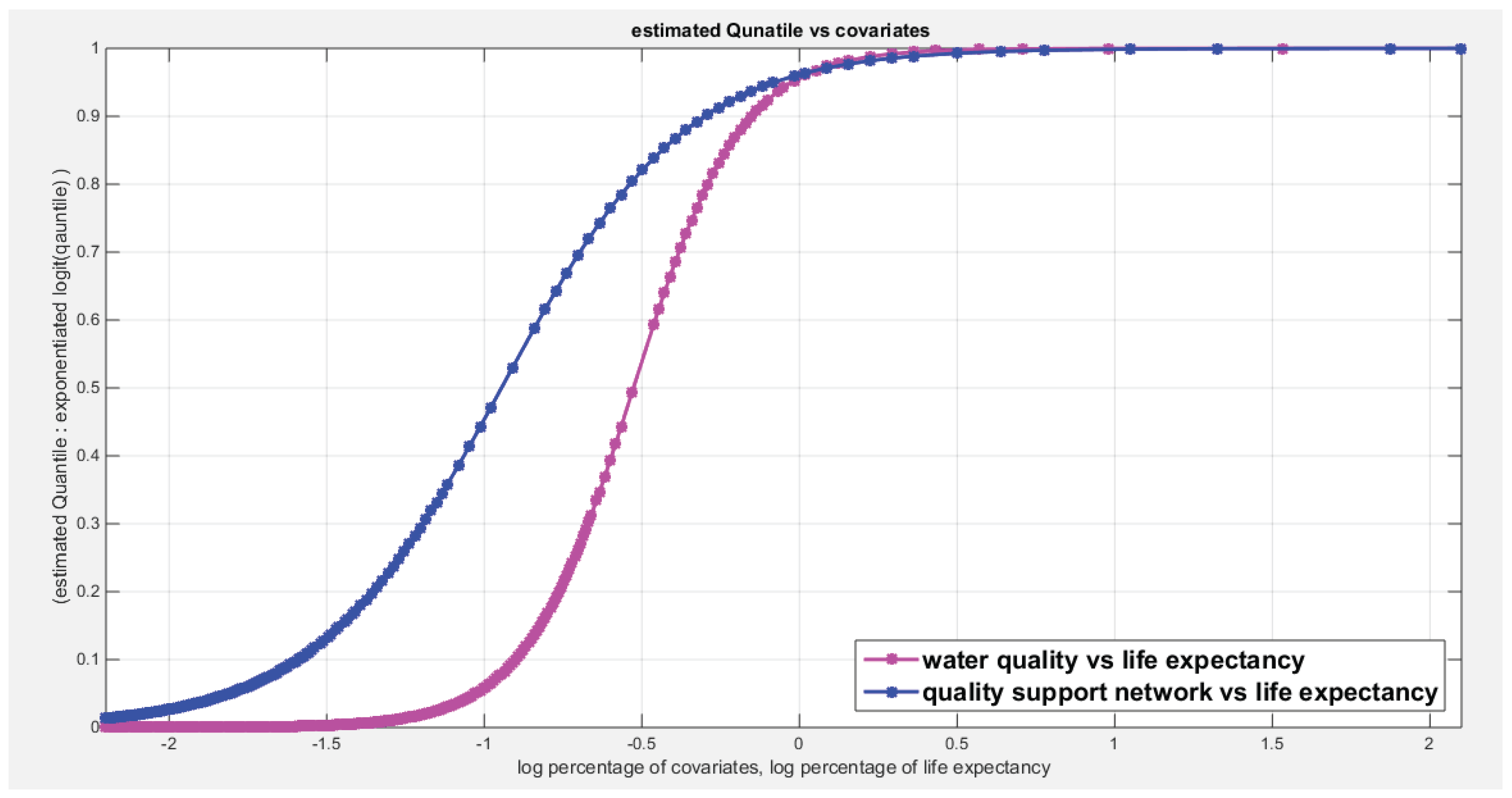

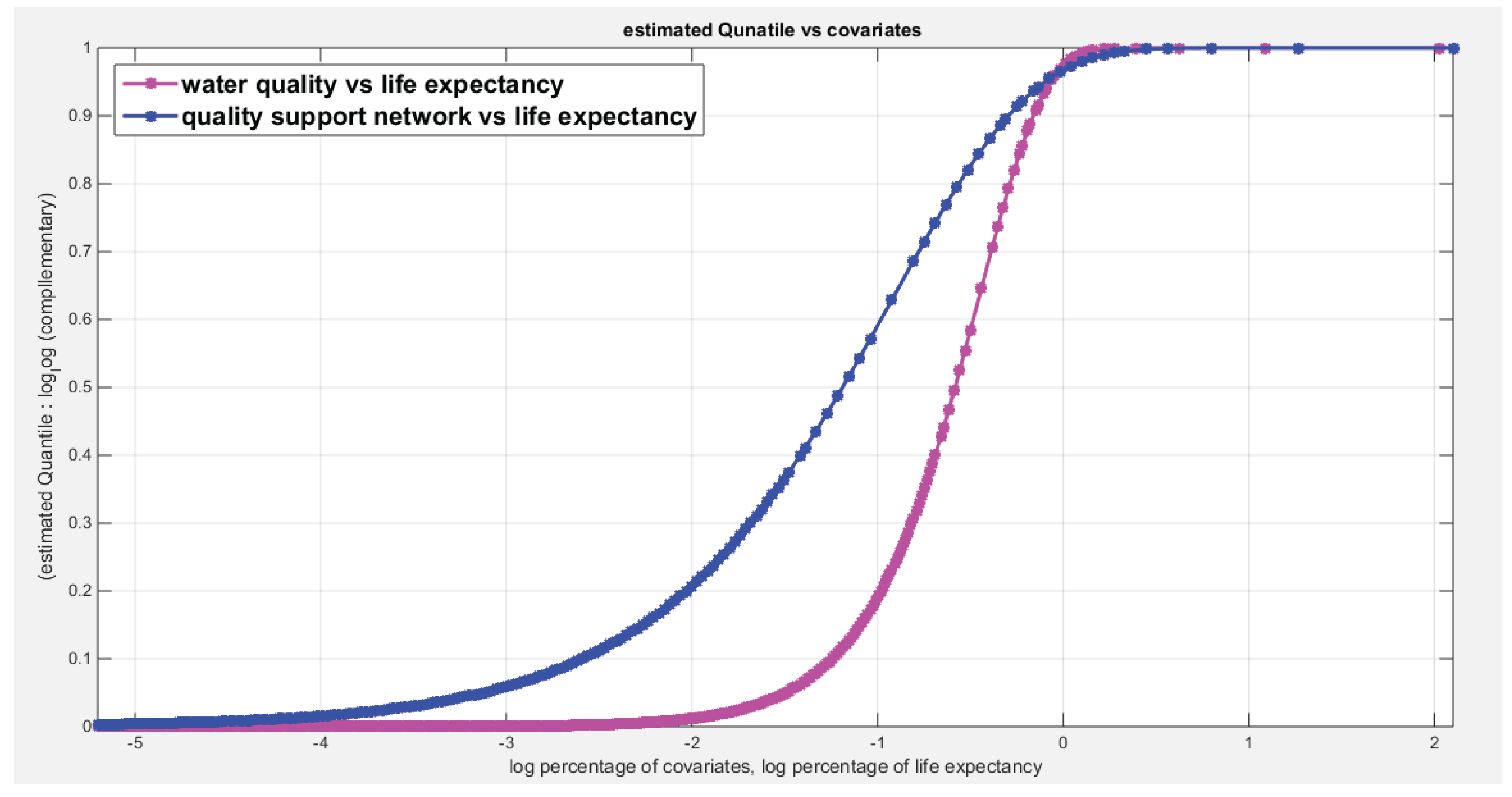

Figure 9 shows the estimated curve for regressing the water quality and the quality of support network on transformed life expectancy. The graph supports the results of the significant effect of life expectancy on the water quality than its significant effect on the quality of support network. The pink curve is steeper than the blue one. Although the log-likelihood has higher value for the model incorporating the quality of support network than the model incorporating the water quality but the LRT points to the significance of the water quality over the quality of support network which is supported by Wald test statistics results and graph in

Figure 9. The more the life expectancy is the more satisfaction of water quality is.

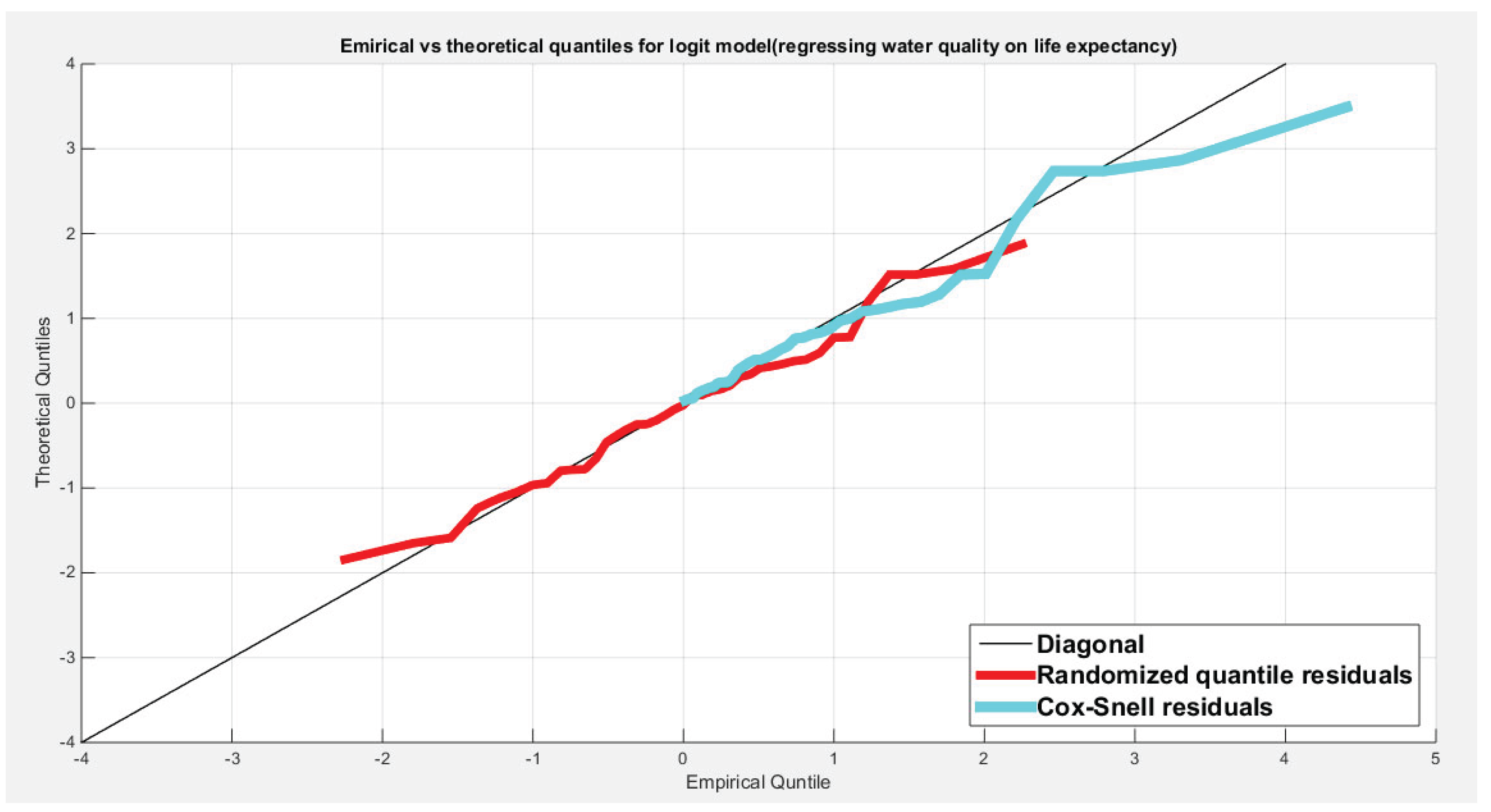

Figure 10 shows the QQ plot of the empirical quantiles versus the theoretical quantiles. The logit model regressing the water quality on the life expectancy has a curve of randomized quantile residuals that shows near perfect alignment with the diagonal all through its course, while the curve of the Cox-Snell residuals is mainly aligned with the diagonal at its lower tail and its center.

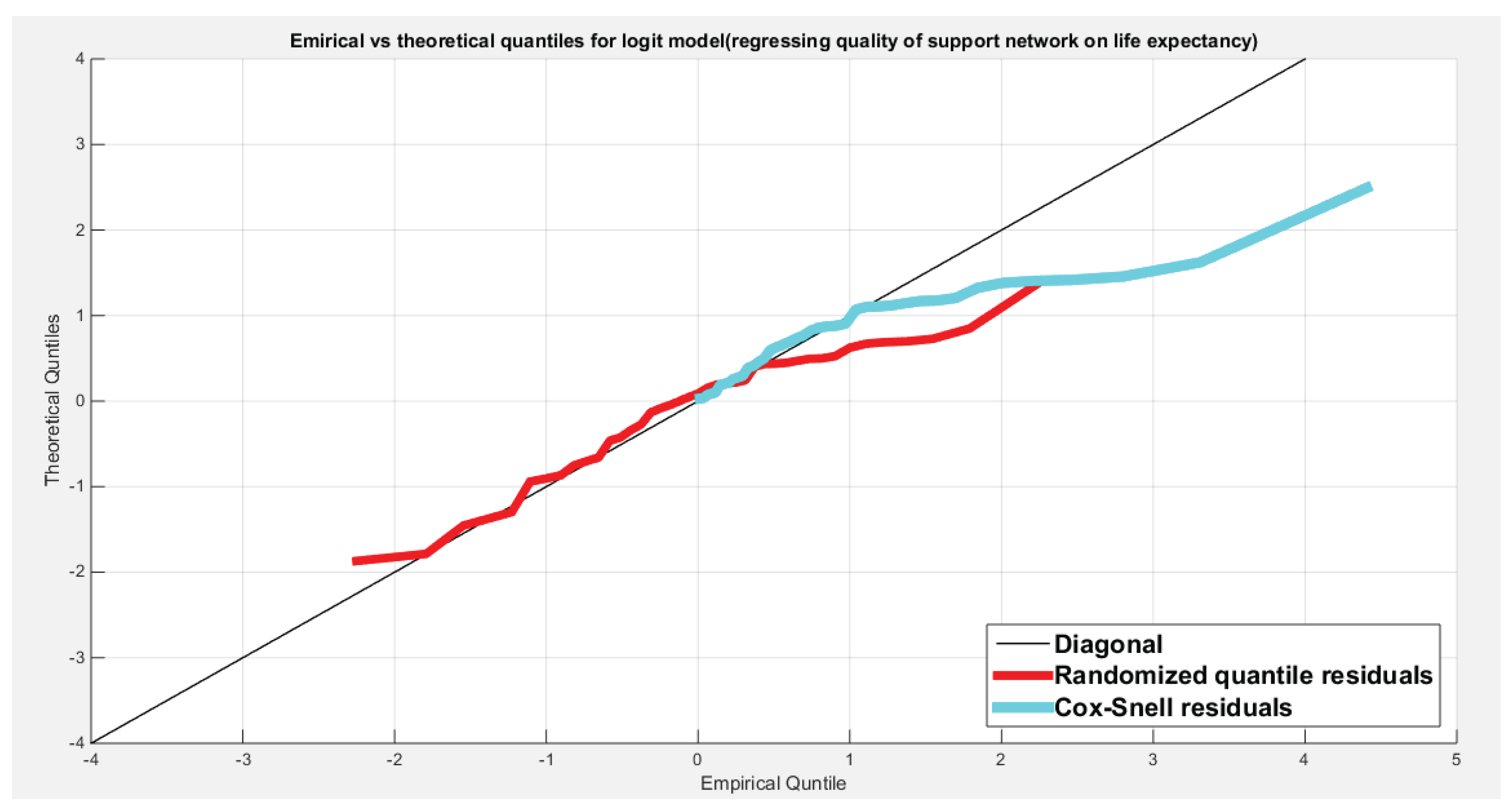

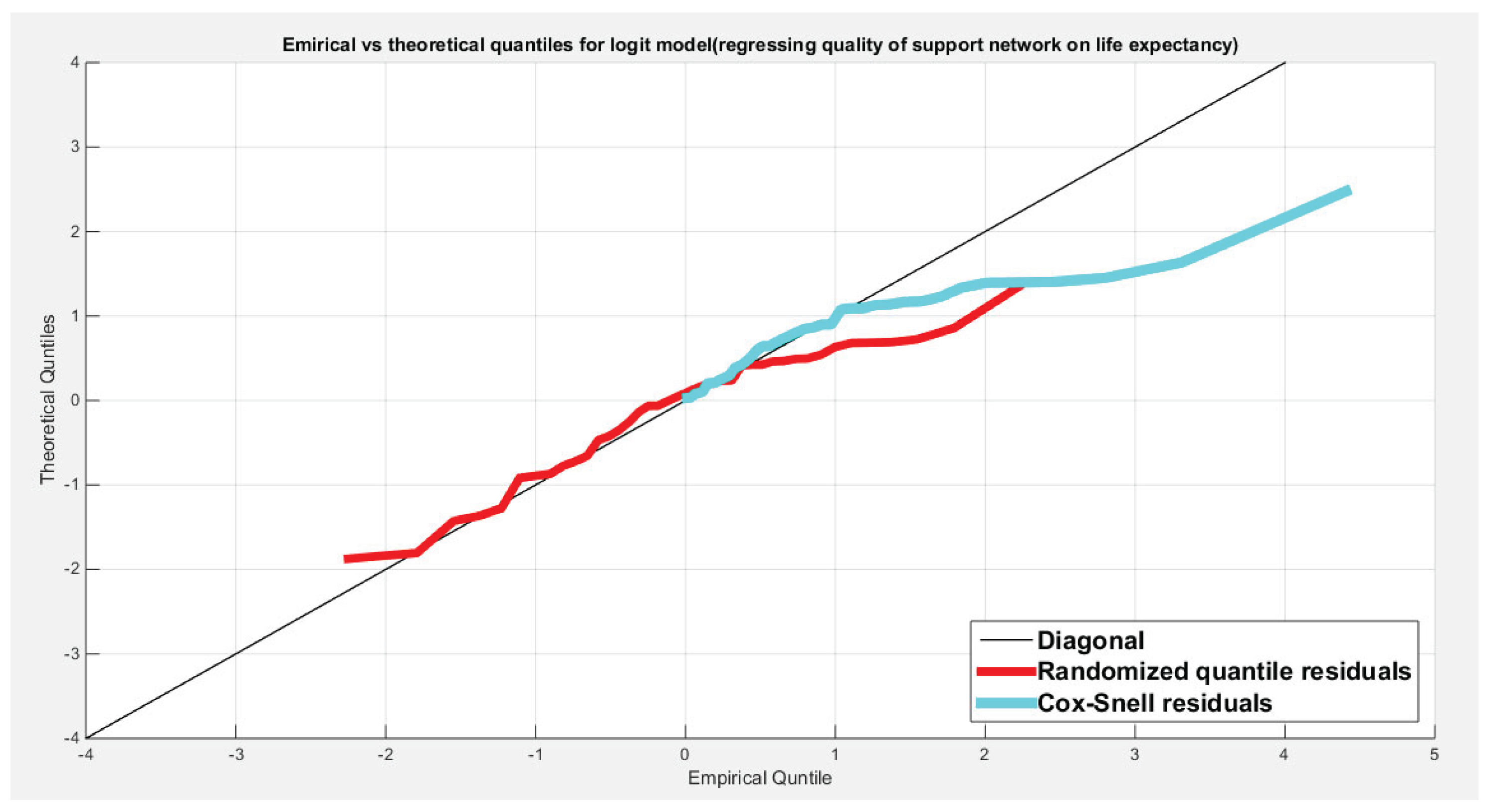

Figure 11 shows the QQ plot for the logit model curve regressing the quality of support network on the life expectancy which has less efficient alignment with the diagonal as regards residuals, the randomized quantile residuals and the Cox-Snell residuals.

Figure 12 and

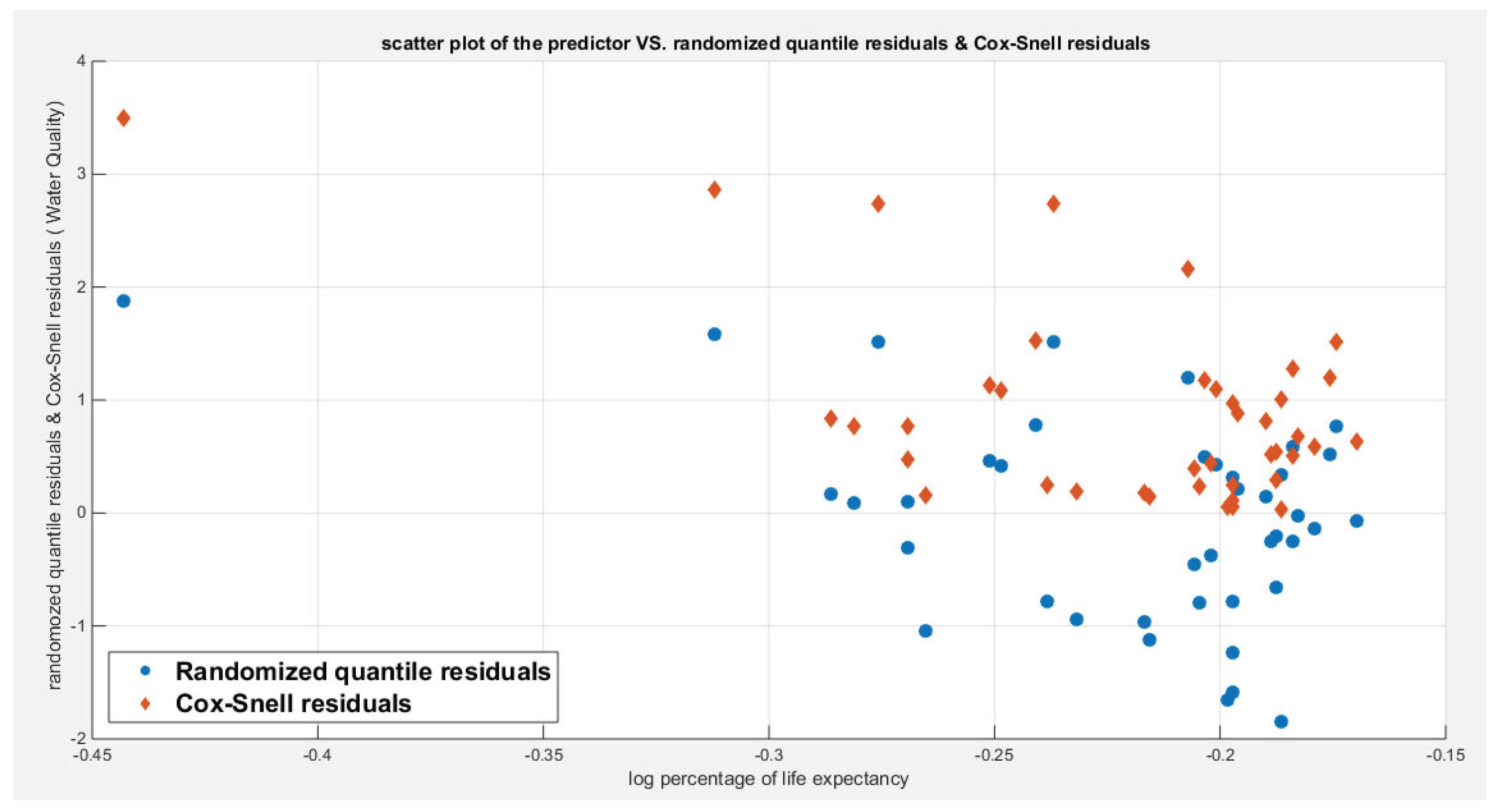

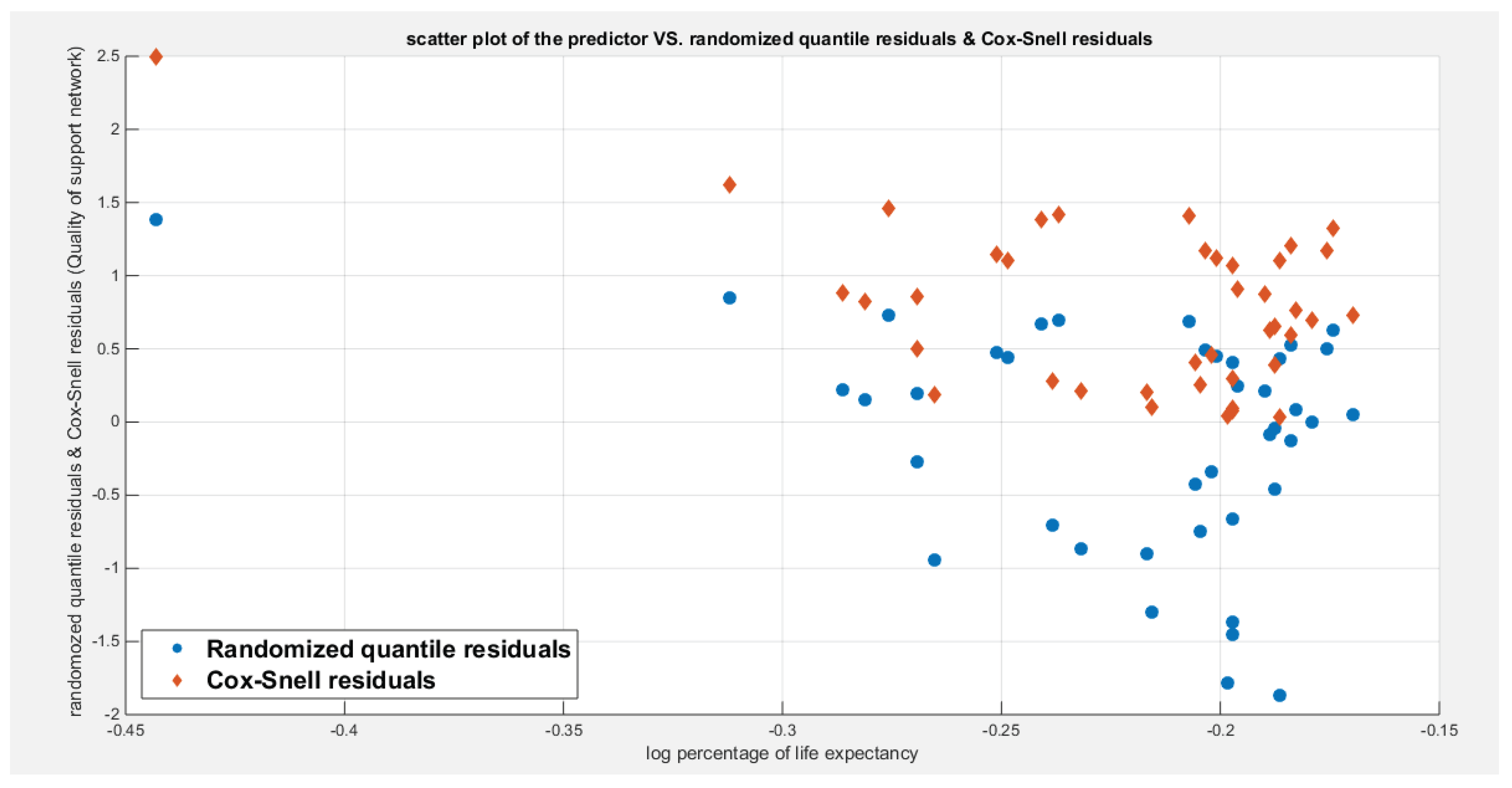

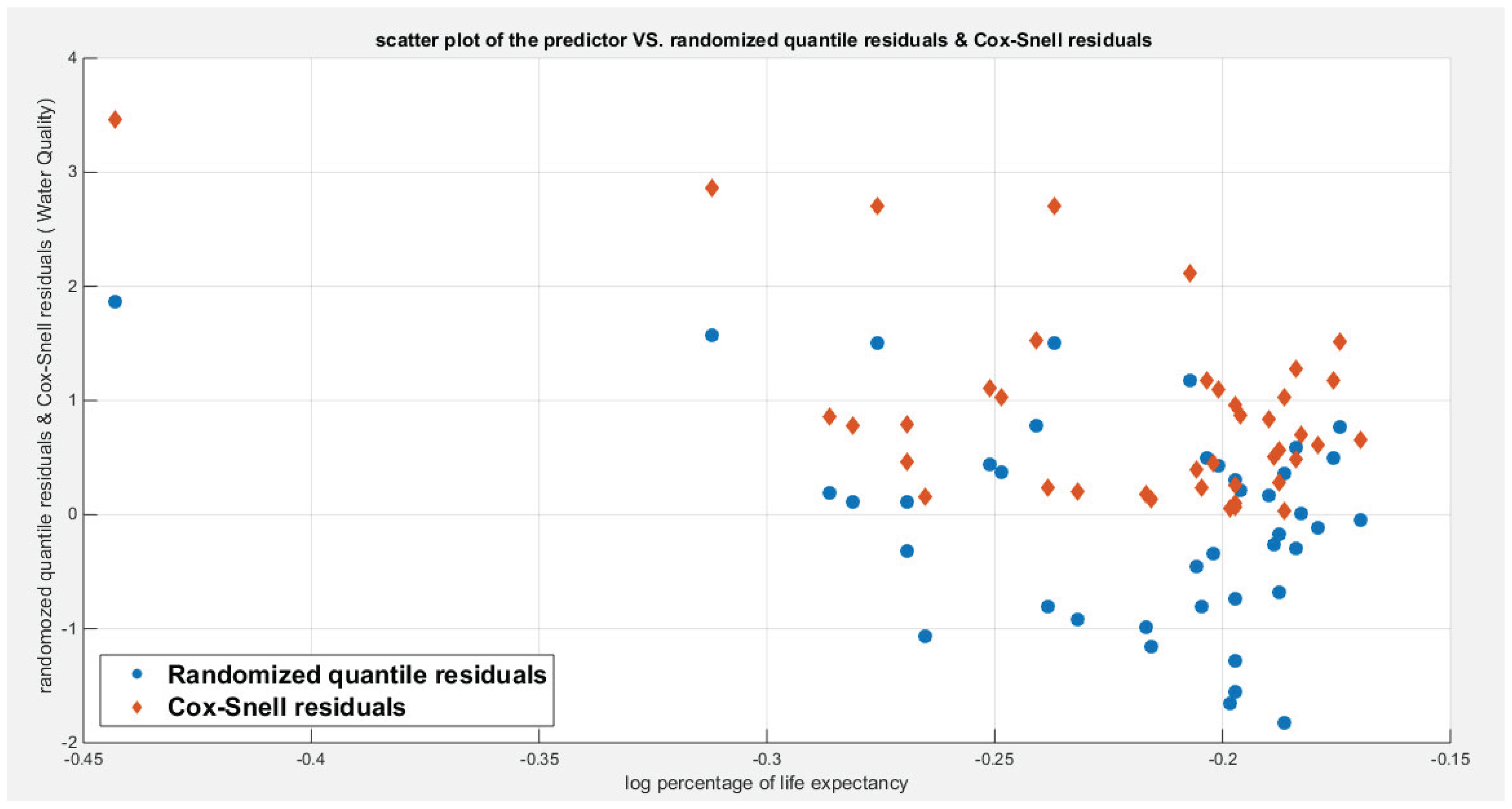

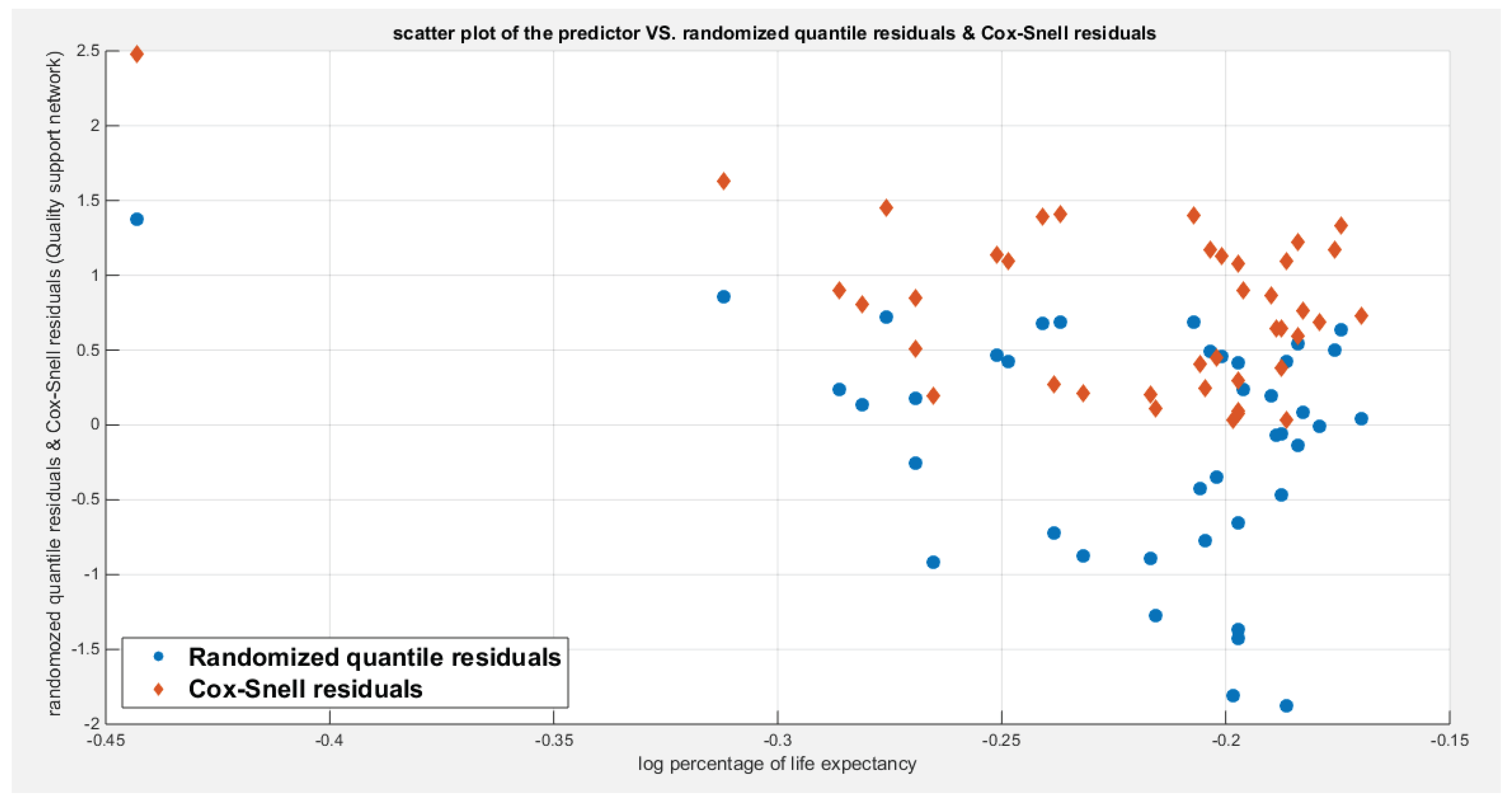

Figure 13 show the scatter plot of the predictor (transformed) and the both types of residuals (randomized quantile and Cox-Snell). There is no nonlinear relationship between the predictor and the residuals. This relationship can be expressed in Kendall tau coefficient as -0.1093 and associated p-value=0.3225 for the response variable (water quality) while it is -0.1104 and associated p-value=0.3171 for the response variable (quality of support network). These values are identical for both types of residuals for each response variable. So there is no evidence for dependency between the predictor and the residuals.

Figure 14 shows the estimated curve for regressing the water quality and the quality of support network on transformed life expectancy. The graph supports the results of the significant effect of life expectancy on the water quality than its significant effect on the quality of support network. The pink curve is steeper than the blue one. Although the log-likelihood has higher value for the model incorporating the quality of support network than the model incorporating the water quality but the LRT points to the significance of the water quality over the quality of support network which is supported by Wald test statistics results and graph in

Figure 14. The more the life expectancy is the more satisfaction of water quality is.

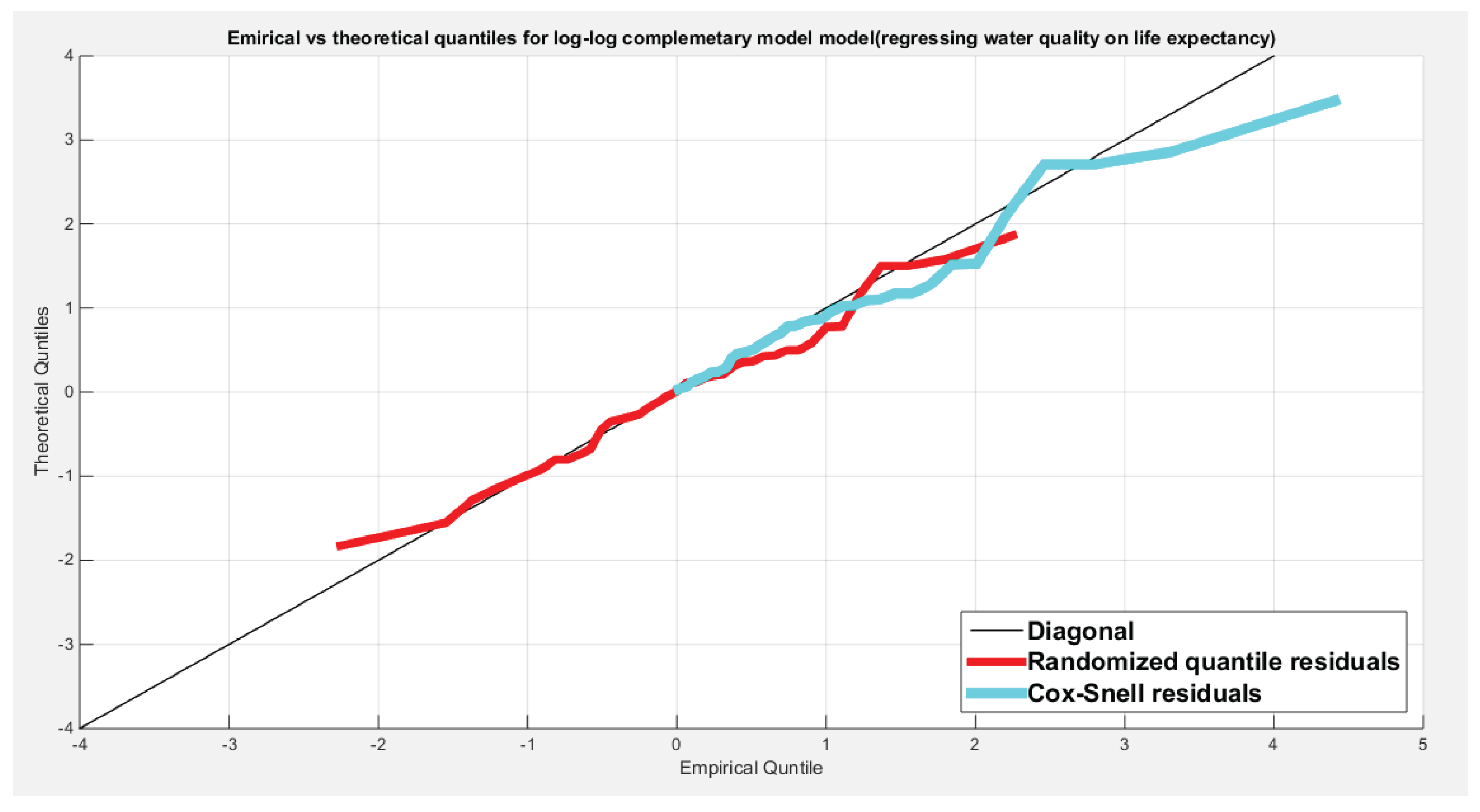

Figure 15 shows the QQ plot of the empirical quantiles versus the theoretical quantiles. The log-log complementary model regressing the water quality on the life expectancy has a curve of randomized quantile residuals that shows near perfect alignment with the diagonal all through its course, while the curve of the Cox-Snell residuals is mainly aligned with the diagonal at its lower tail and its center.

Figure 16 shows the QQ plot for the log-log complementary model curve regressing the quality of support network on the life expectancy which has less efficient alignment with the diagonal as regards the residuals, the randomized quantile residuals and the Cox-Snell residuals.

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 show the scatter plot of the predictor (transformed) and both types of residuals (the randomized quantile and the Cox-Snell). There is no nonlinear relationship between the predictor and the residuals. This relationship can be expressed in Kendall tau coefficient as -0.1093 and associated p-value=0.3225 for the response variable (water quality) while it is -0.1104 and associated p-value=0.3171 for the response variable (quality of support network). These values are identical for both types of residuals for each response variable. So there is no evidence for dependency between the predictor and the residuals.

Fourth Step of Algorithm: The Copula Parametric Quantile Regression

The quantile parametric copula regression is a copula regression model utilizing the fitted marginal CDFs obtained from the fitted marginal quantile parametric MBUR regression models. Regressing each copula dependency parameter on the corresponding observation with the aid of the link function

where h is the link function that ensures the dependency parameter is larger than one. The author used the Inference Function of Margin (IFM) and the Nelder Mead algorithm of MATLAB as an optimizer. The Gumbel copula PDF is

where

, reparameterize the dependency parameter

in this copula PDF with the

, in other words, replace the right hand side of the link function in copula PDF and optimize. The u and v are the fitted CDFs obtained from the quantile marginal regression step. The relation between the theta dependence parameter and Kendall tau is

. After applying the copula regression in this step, there will be a value of theta for each

, and in

Table 6, the mean of this tau is recorded as the mean of theoretical tau while the empirical tau is calculated from the u and v.

The Gumbel copula CDF is

Table 6 enlightens the results of copula regression part using log-log complementary model and the logit model. The AIC, CAIC, BIC, HQIC for the logit model are less than those of the log-log complementary model. CVM for the logit is less than that of the log-log complementary model. The LRT is statistically significant for the logit model than the LRT for the complementary model.

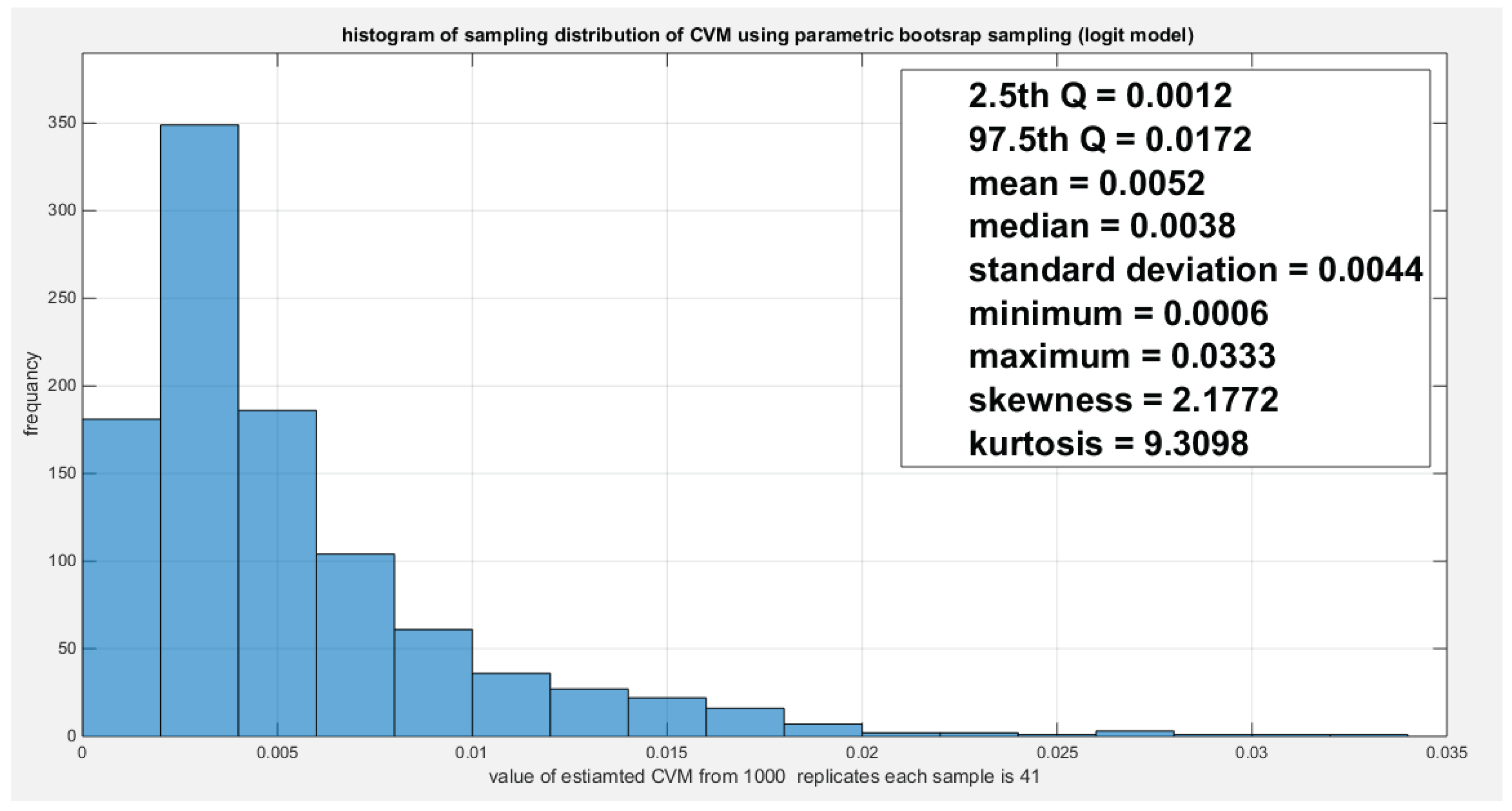

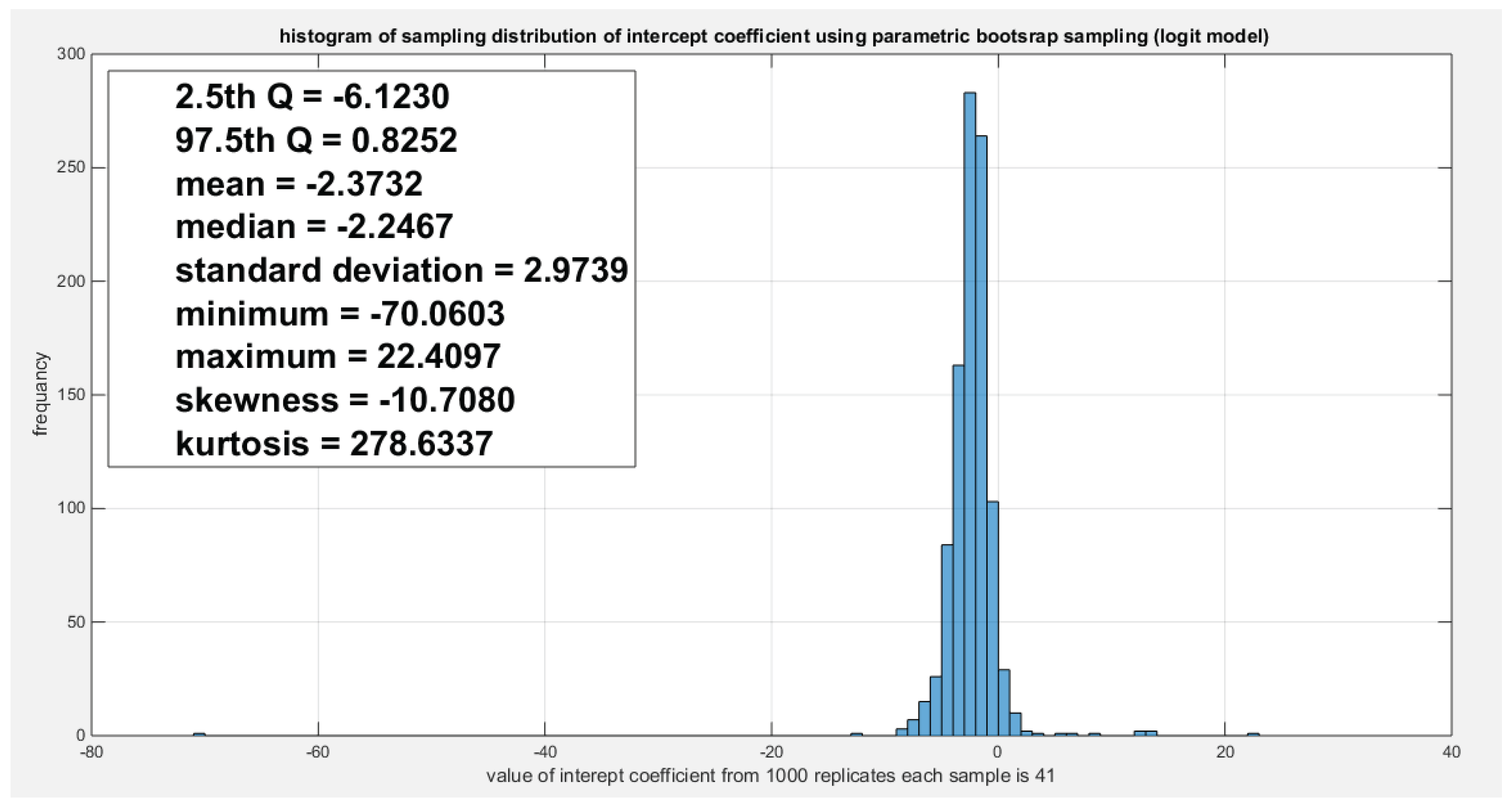

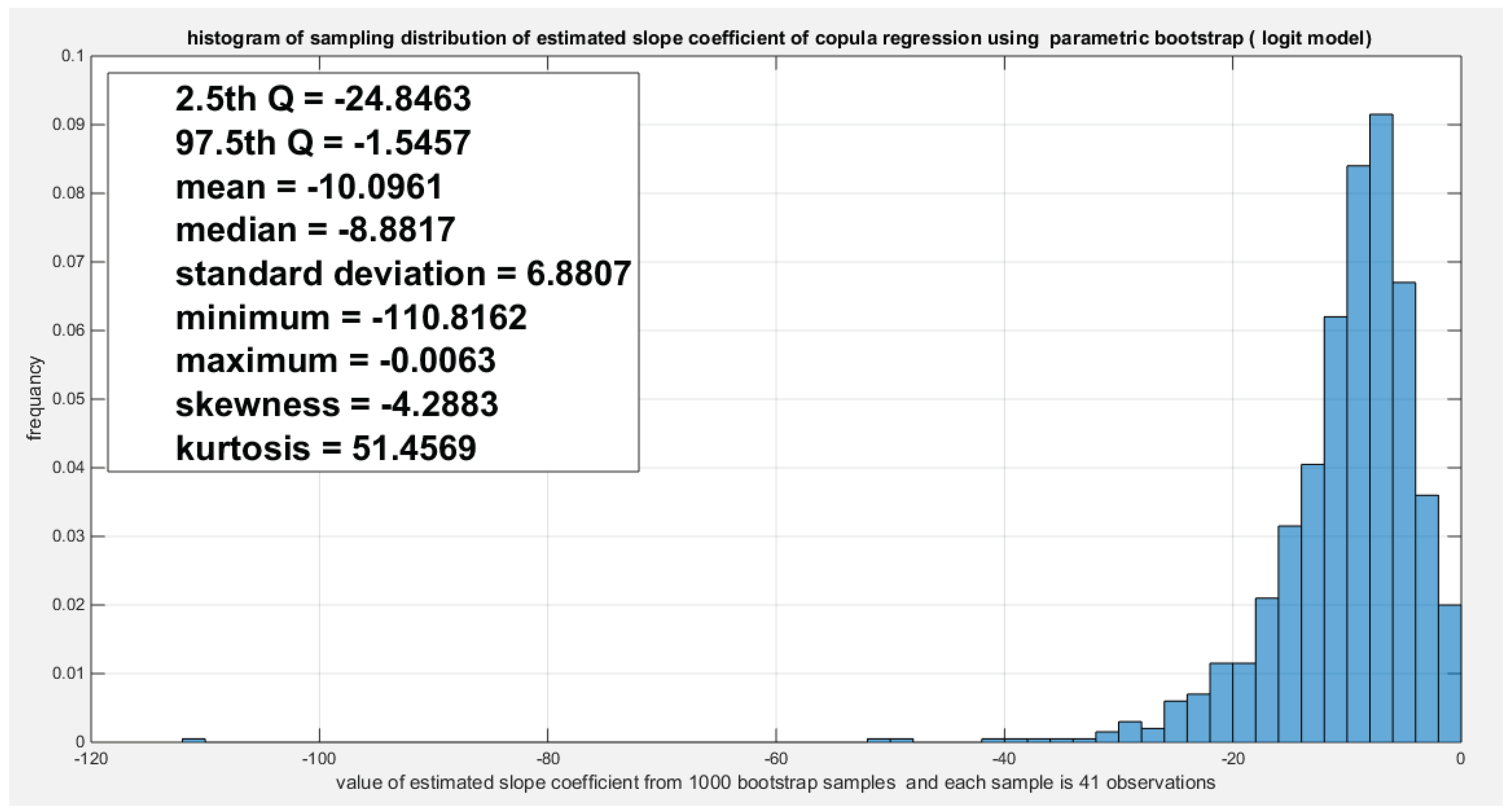

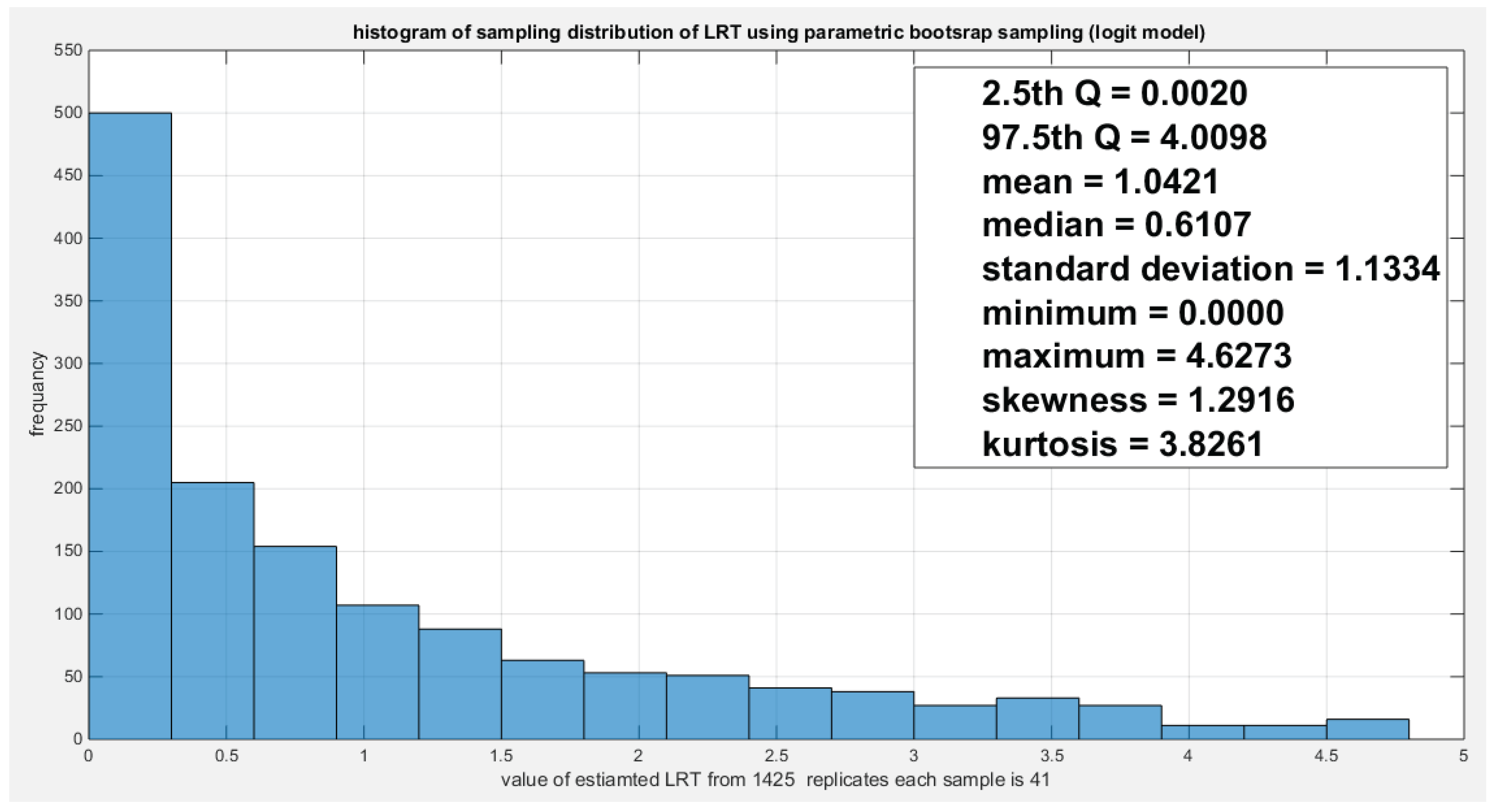

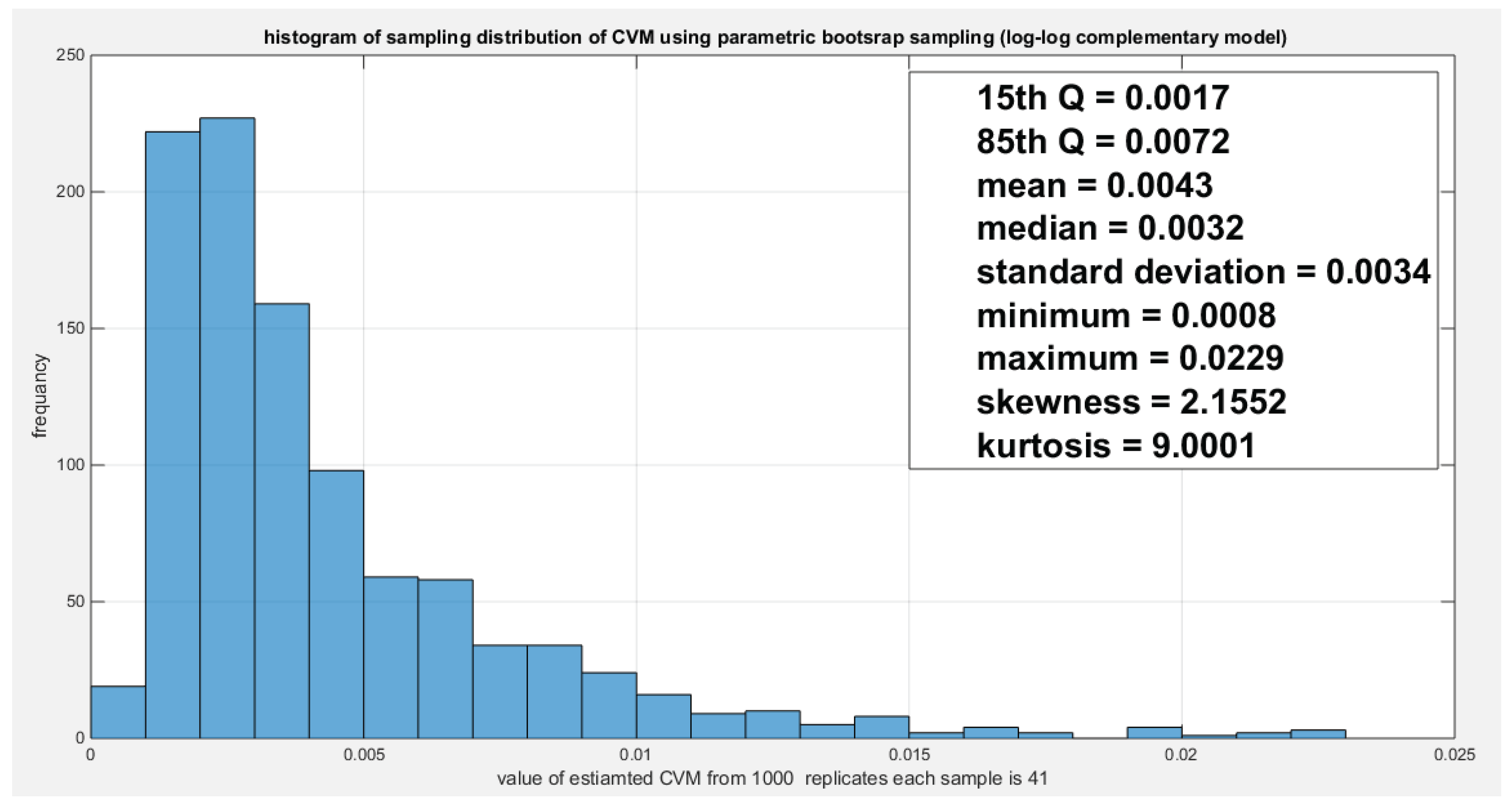

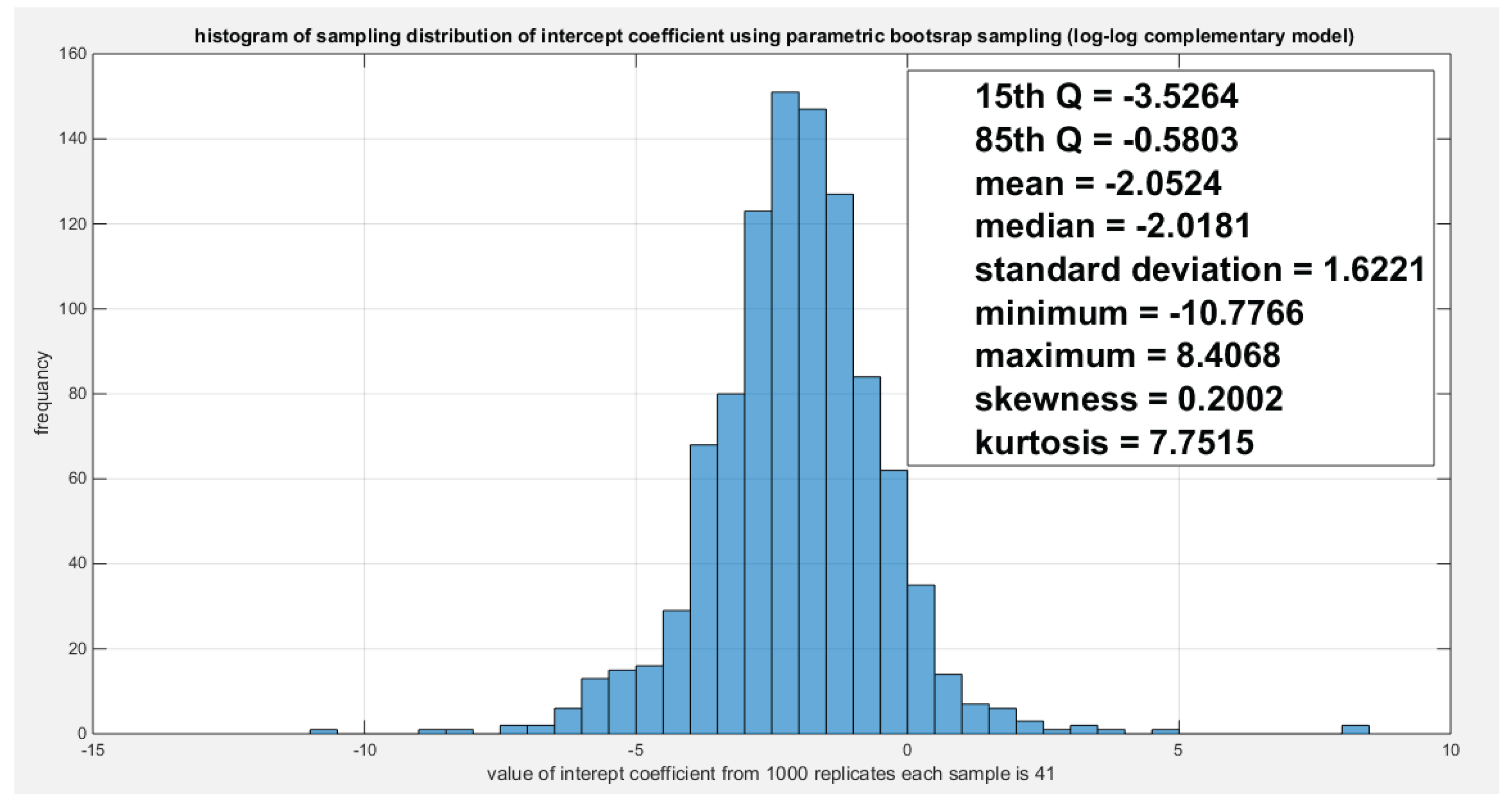

Figure 19,

Figure 20 and

Figure 21 explicate the histogram of the parametric bootstrap sampling of the estimated CVM, estimated intercept and the estimated slope, respectively obtained from the logit model depicting the descriptive statistics as shown in each figure.

Figure 22 elucidates that the estimated LRT value (4.3426) lies between the 2.5

th and 97.5

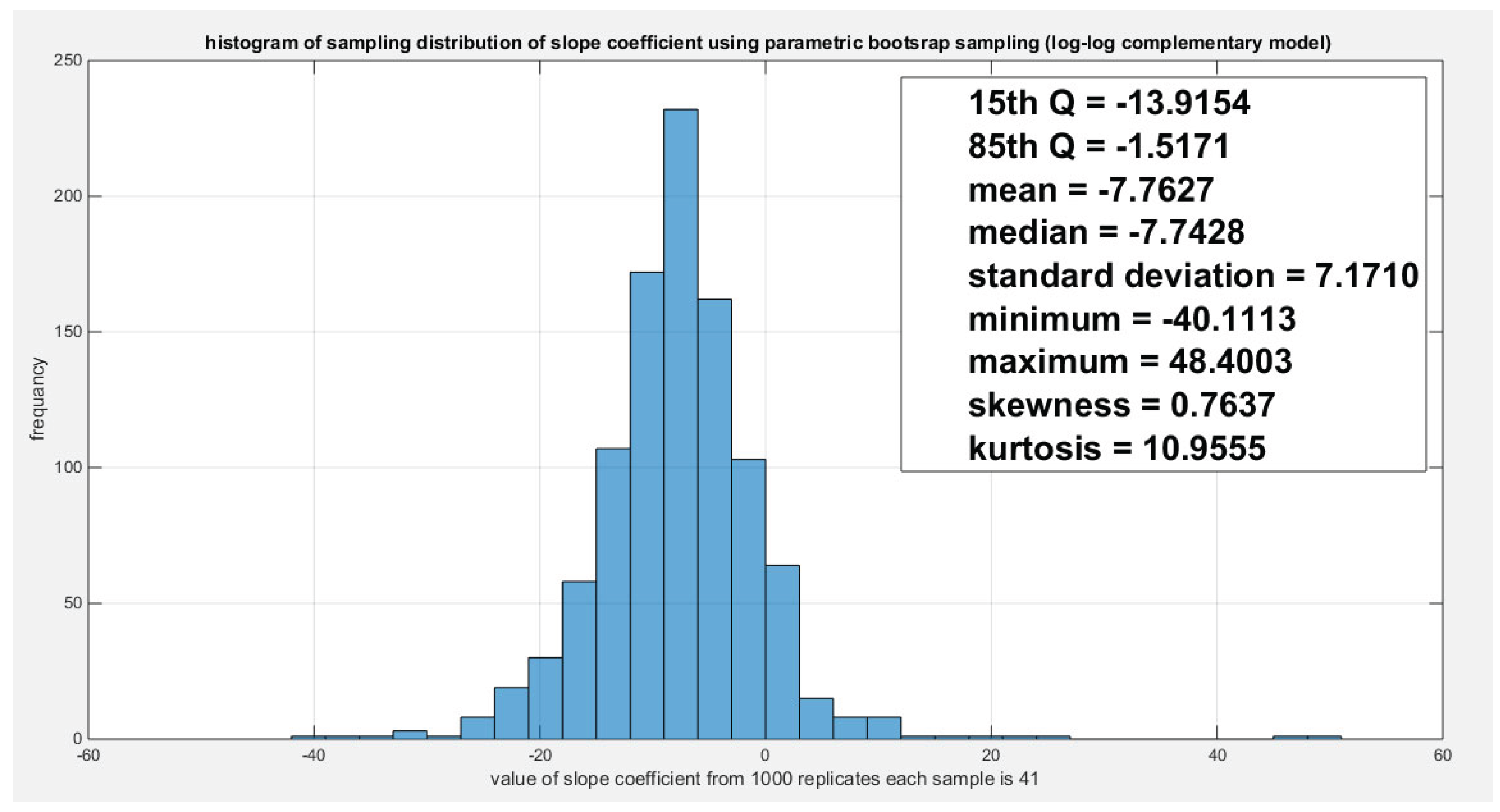

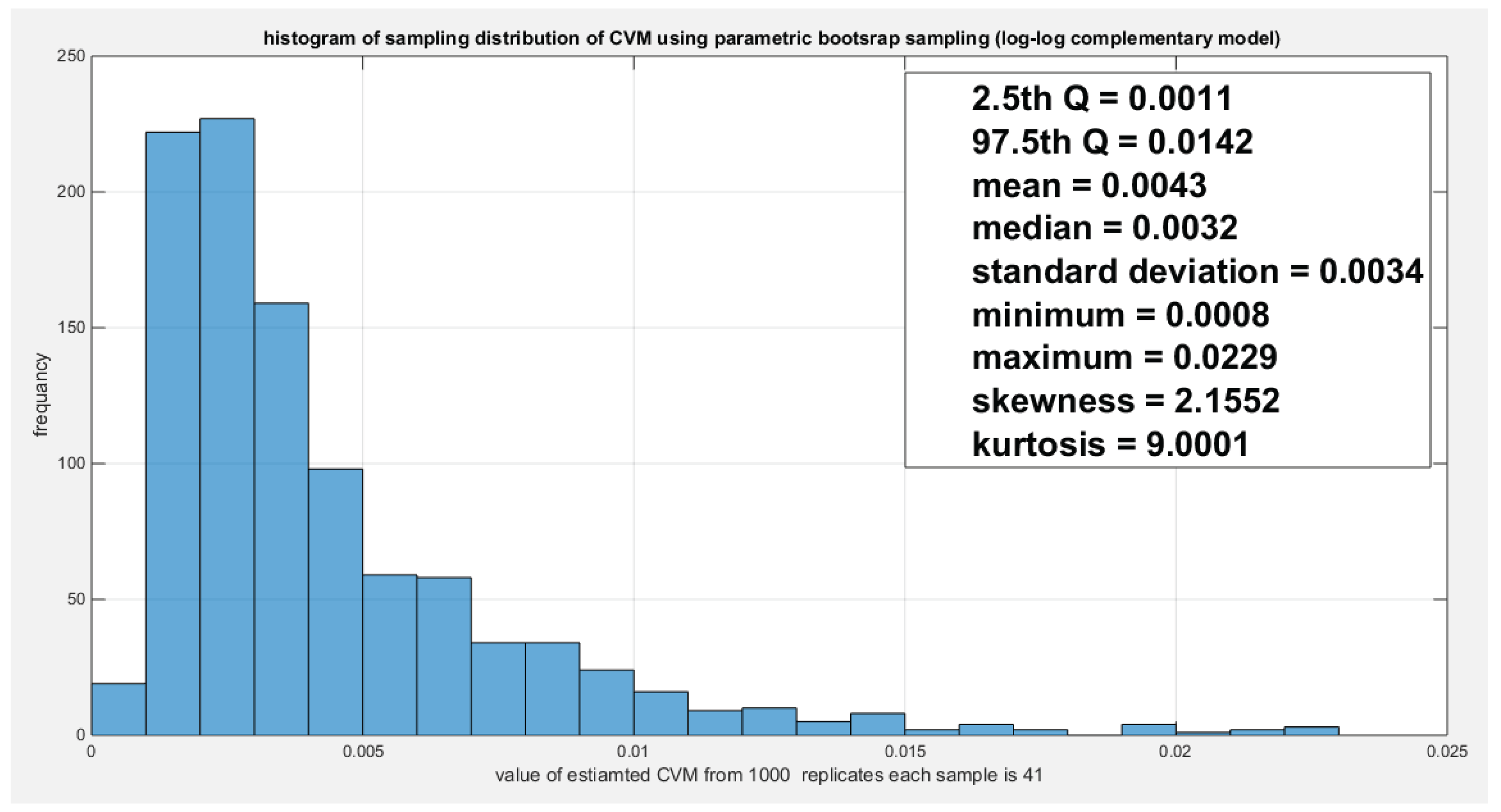

th quantile of the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution. The slope is 5 % statistically significant using the logit model. The log-log complementary model shows 30% statistical significance of the estimated CVM, estimated intercept, and estimated slope using the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution as expounded in

Figure 23,

Figure 24 and

Figure 25. Although, the estimated CVM is statistically significant at 5% significance level as shown from parametric sampling distribution in

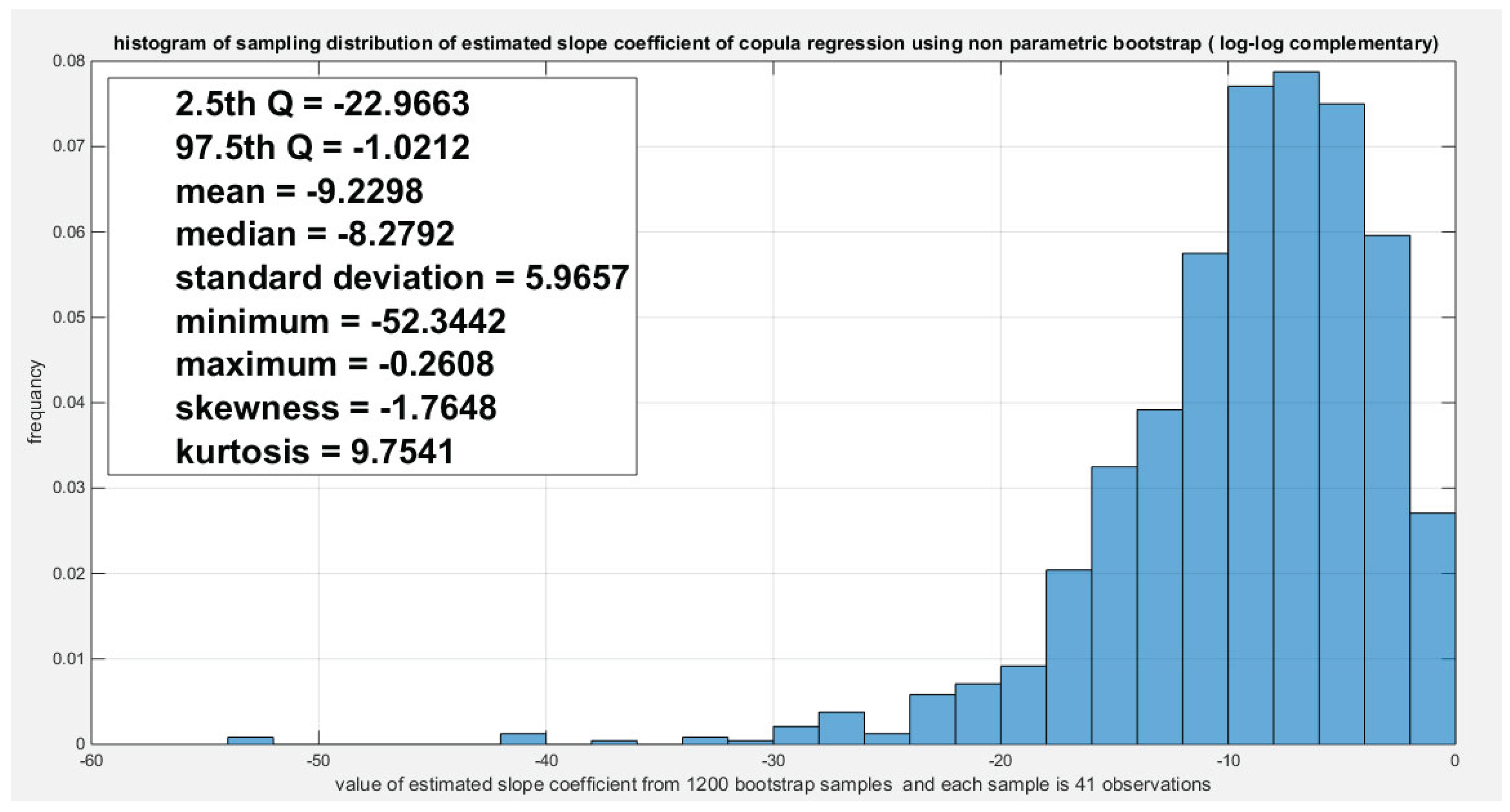

Figure 26, the estimated slope is statistically significant at 5% significant level as shown from the non-parametric bootstrap sampling distribution in

Figure 27; which is less powerful than the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution.

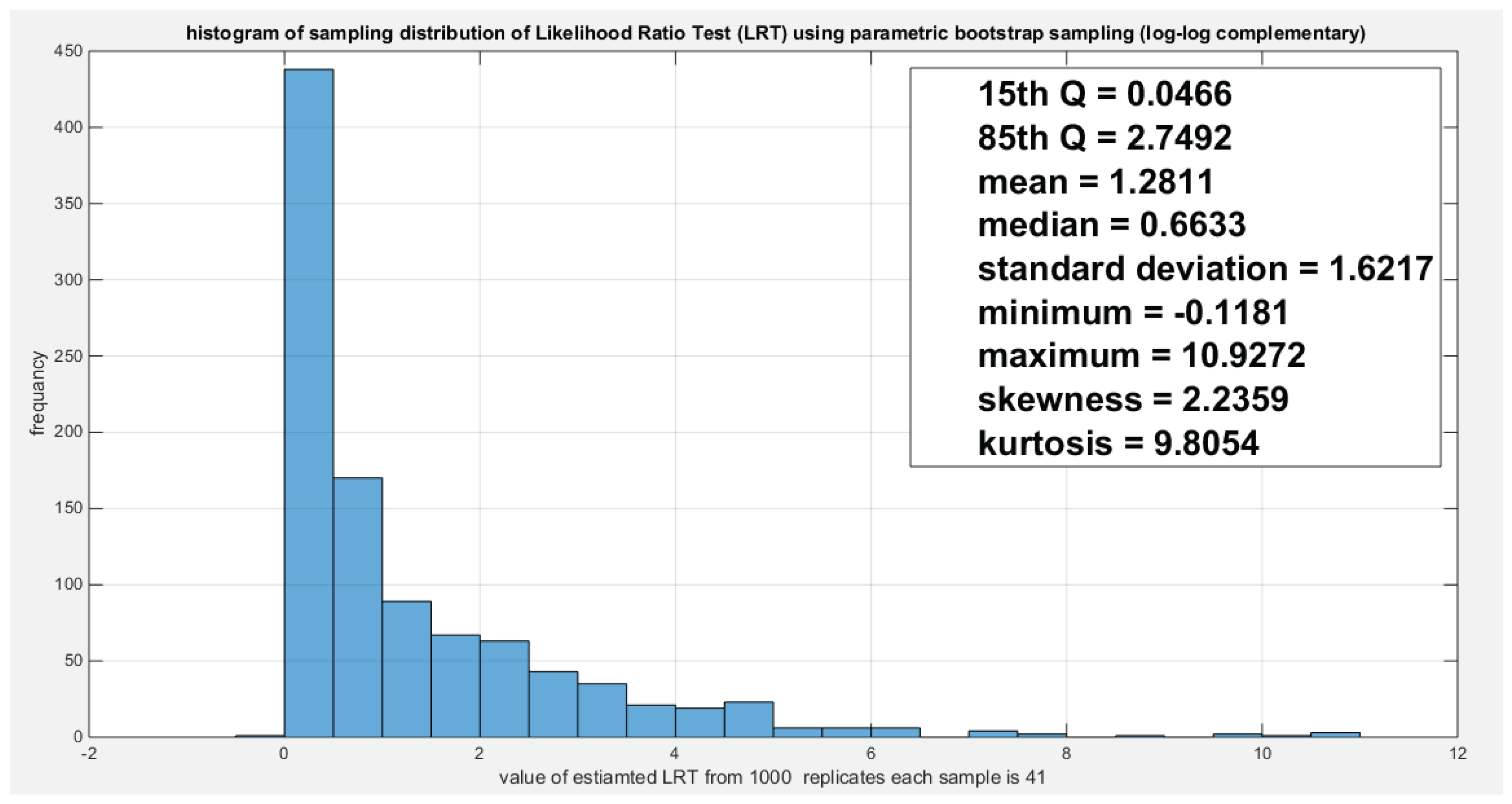

Figure 28 shows the parametric bootstrap sampling of the LRT illuminating that the LRT is significant at 30% significant level for the log-log complementary model.

From the above results, the logit model demonstrates better fit for the effect of predictor (life expectancy) on the dependency between the 2 response variables (water quality and quality of support network) than the log-log complementary model. The logit model is significant at 5% significant level while the log-log model is significant at 30 % significant level.

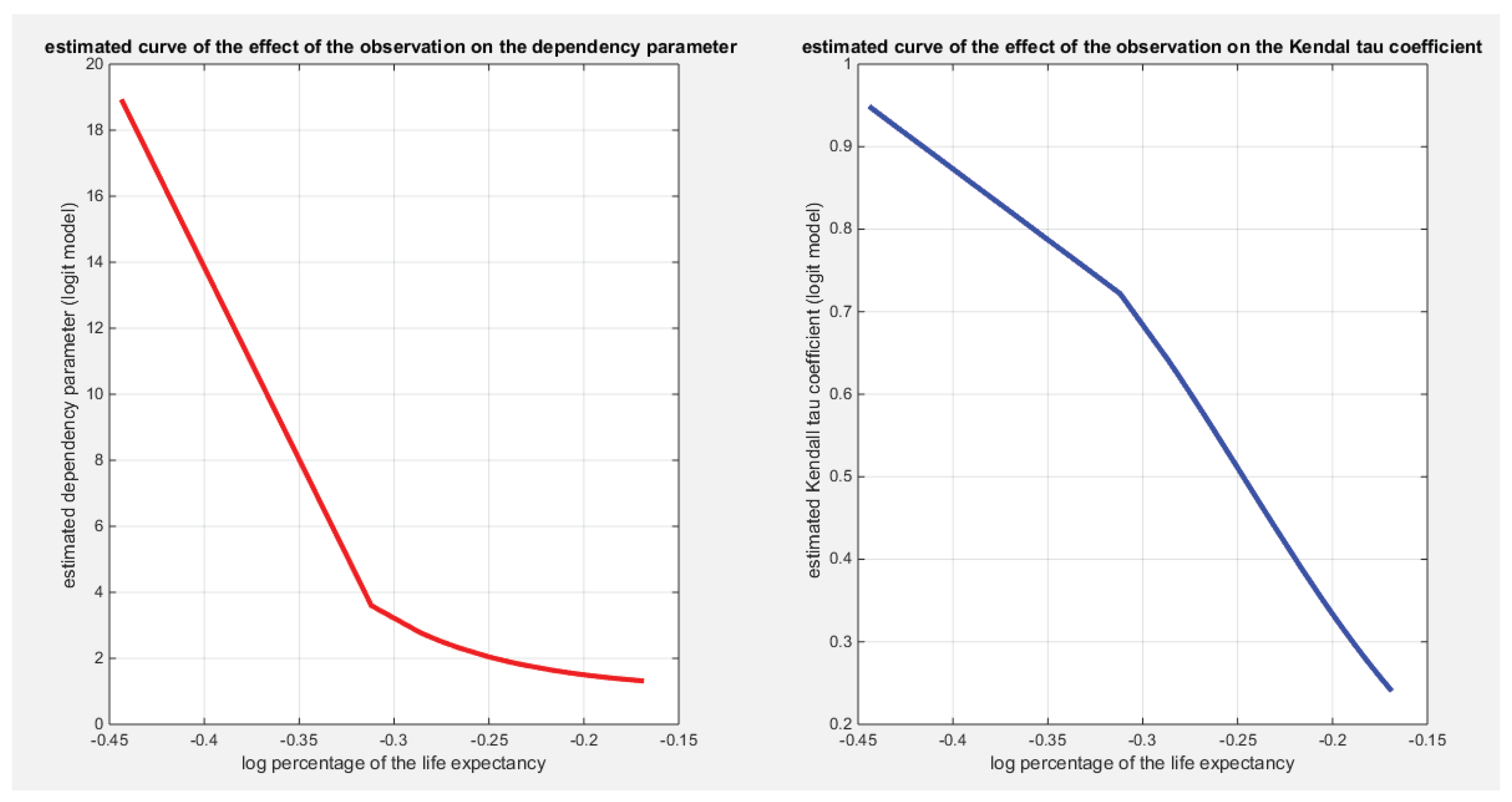

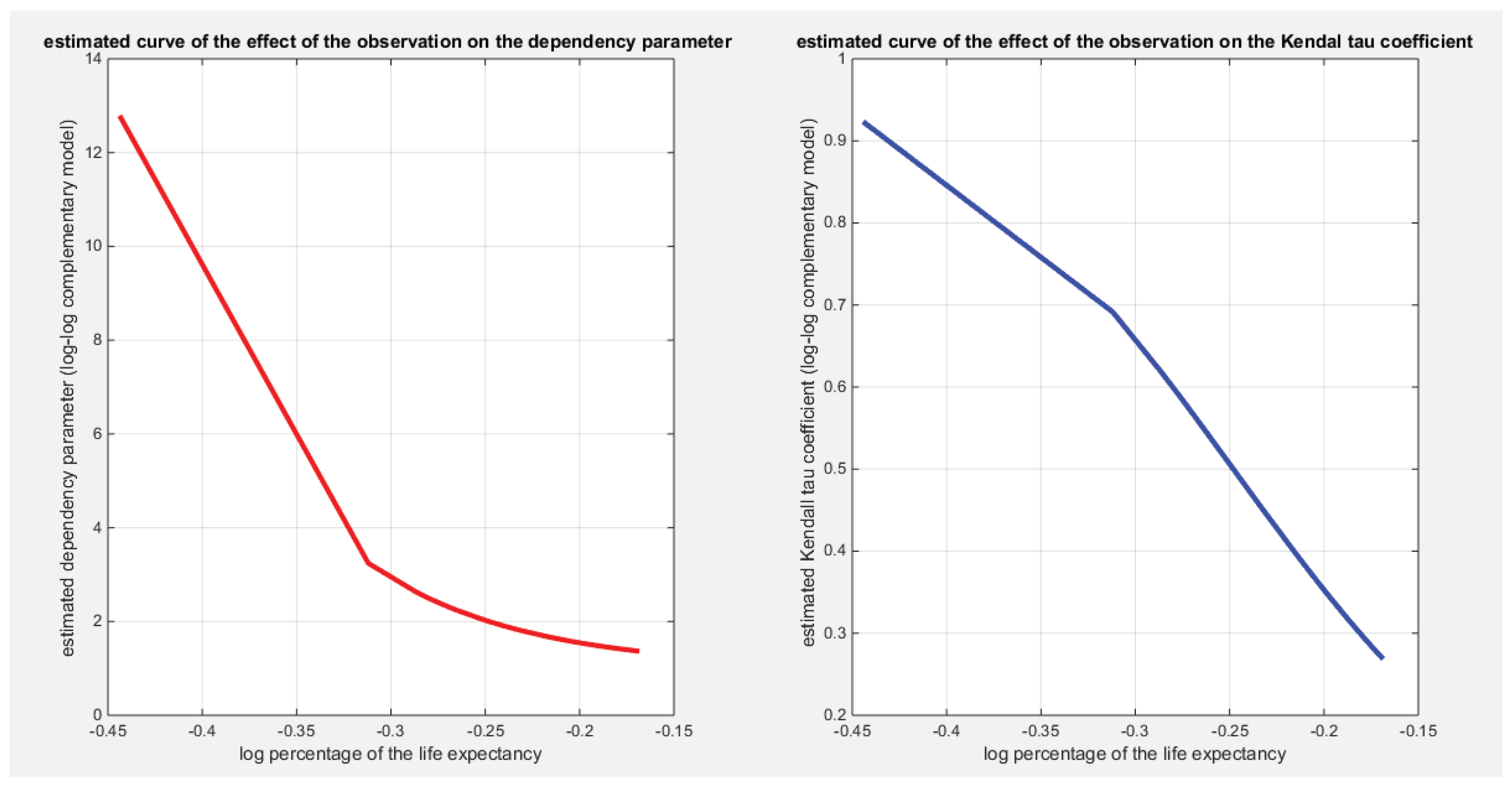

Figure 29 and

Figure 30 show that as the life expectancy increases, the dependency between water quality and quality of support network decrease for both the logit and the complementary model.

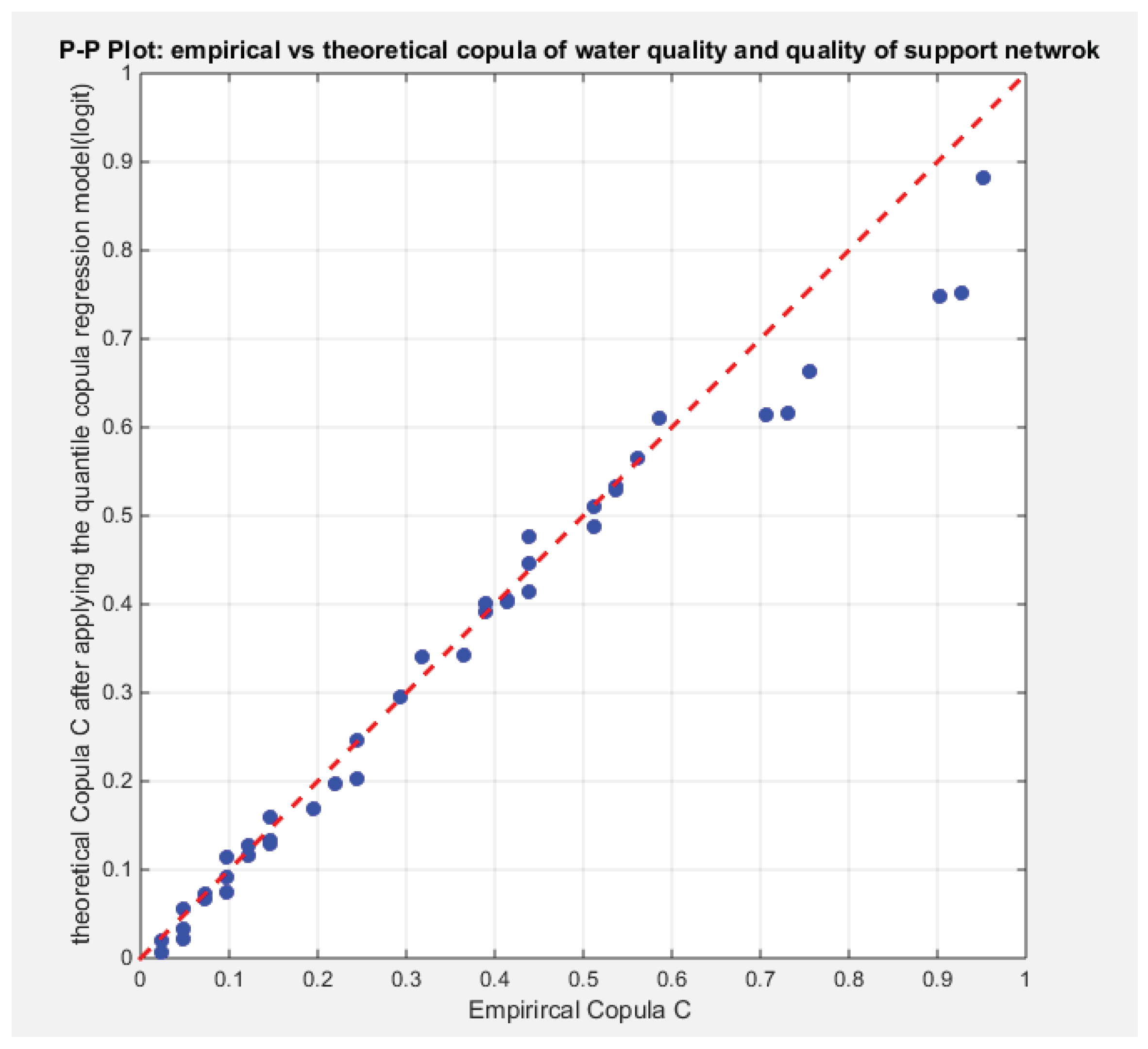

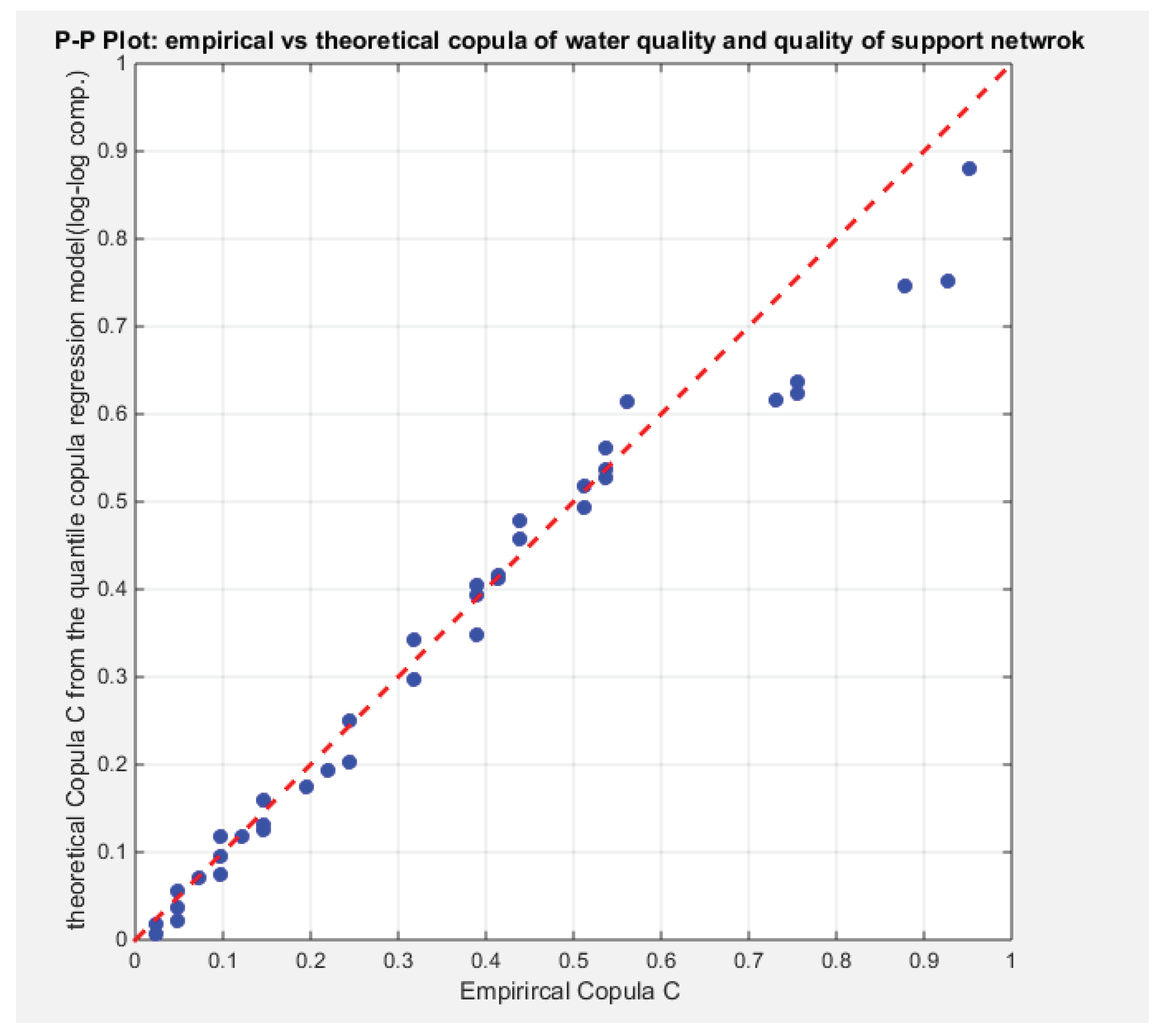

Figure 31 and

Figure 32 show the PP plot of the fitted theoretical copula vs. the empirical copula of the second regression part, the copula regression. Both graphs show near perfect alignment all through the course except of 6 observations which are a little bit far away from the diagonal.

Figure 1.

Shows the boxplot of the two response variable; water quality and quality support network. Both variables demonstrate left skewness, being -0.6059 for water quality and -1.176 for the quality support network.

Figure 1.

Shows the boxplot of the two response variable; water quality and quality support network. Both variables demonstrate left skewness, being -0.6059 for water quality and -1.176 for the quality support network.

Figure 2.

Shows the scatter plot of the two response variables that exhibits significant positive dependency. The Kendall Tau is 0.03929 and p-value=0.0006.

Figure 2.

Shows the scatter plot of the two response variables that exhibits significant positive dependency. The Kendall Tau is 0.03929 and p-value=0.0006.

Figure 3.

Shows the non-linear relationship between the two response variables and the predictors, life expectancy (transformed). The Kendall tau between the water quality and the life expectancy (raw and not transformed) is statistically significant (tau= 0.2859, p-value=0.0099) while the Kendall tau between the quality of support network and the life expectancy (raw & not transformed) is statistically insignificant (tau=0.2079 p-value=0.0667).

Figure 3.

Shows the non-linear relationship between the two response variables and the predictors, life expectancy (transformed). The Kendall tau between the water quality and the life expectancy (raw and not transformed) is statistically significant (tau= 0.2859, p-value=0.0099) while the Kendall tau between the quality of support network and the life expectancy (raw & not transformed) is statistically insignificant (tau=0.2079 p-value=0.0667).

Figure 4.

Shows the fitted PDF of MBUR for both response variables.

Figure 4.

Shows the fitted PDF of MBUR for both response variables.

Figure 7.

Shows the sampling distribution of the estimated dependency parameter coefficient. The estimated tau is 1.6403 and it lies between the 2.5th and 97.5th empirical quantile. The null hypothesis testing the estimated dependency parameter is failed to be rejected.

Figure 7.

Shows the sampling distribution of the estimated dependency parameter coefficient. The estimated tau is 1.6403 and it lies between the 2.5th and 97.5th empirical quantile. The null hypothesis testing the estimated dependency parameter is failed to be rejected.

Figure 8.

Shows the sampling distribution of the estimated CVM. The estimated tau is 0.2154 and it lies between the 2.5th and 97.5th empirical quantile. The null hypothesis testing the estimated CVM is failed to be rejected.

Figure 8.

Shows the sampling distribution of the estimated CVM. The estimated tau is 0.2154 and it lies between the 2.5th and 97.5th empirical quantile. The null hypothesis testing the estimated CVM is failed to be rejected.

Figure 9.

Shows that the curve of the logit model regressing the water quality on life expectancy is steeper than the curve that models the regression of quality of support network on life expectancy.

Figure 9.

Shows that the curve of the logit model regressing the water quality on life expectancy is steeper than the curve that models the regression of quality of support network on life expectancy.

Figure 10.

Shows the QQ plot of the empirical vs. the theoretical quantiles for the logit model where the water quality is regressed on the life expectancy. The randomized quantile residuals show near perfect alignment all through the course of the curve in contrast to the Cox-Snell residuals which show more or less near alignment mainly in the lower tail and center of the curve than the upper tail.

Figure 10.

Shows the QQ plot of the empirical vs. the theoretical quantiles for the logit model where the water quality is regressed on the life expectancy. The randomized quantile residuals show near perfect alignment all through the course of the curve in contrast to the Cox-Snell residuals which show more or less near alignment mainly in the lower tail and center of the curve than the upper tail.

Figure 11.

Shows the QQ plot of the empirical vs. the theoretical quantiles for the logit model where the quality of support network is regressed on the life expectancy. The randomized quantile residuals show near perfect alignment at the lower part and the center of the curve. While the Cox-Snell residuals only depict near alignment at the lower tail.

Figure 11.

Shows the QQ plot of the empirical vs. the theoretical quantiles for the logit model where the quality of support network is regressed on the life expectancy. The randomized quantile residuals show near perfect alignment at the lower part and the center of the curve. While the Cox-Snell residuals only depict near alignment at the lower tail.

Figure 12.

Shows the scatter plot between the life expectancy predictor (transformed) and the randomized quantile residuals and Cox-Snell residuals for the logit model regressing the life expectancy on water quality. There is no specific trend or relationship between them and the scatter is random. No evidence of dependence between the predictor and the residuals of both types. The Kendall tau dependency parameter between the predictor and the residuals is -0.1093 with p-value= 0.3225 which is not statistically significant. These values are true for both types of residuals.

Figure 12.

Shows the scatter plot between the life expectancy predictor (transformed) and the randomized quantile residuals and Cox-Snell residuals for the logit model regressing the life expectancy on water quality. There is no specific trend or relationship between them and the scatter is random. No evidence of dependence between the predictor and the residuals of both types. The Kendall tau dependency parameter between the predictor and the residuals is -0.1093 with p-value= 0.3225 which is not statistically significant. These values are true for both types of residuals.

Figure 13.

Shows the scatter plot between the life expectancy predictor (transformed) and the randomized quantile residuals and Cox-Snell residuals for the logit model regressing the life expectancy on quality of support network . There is no specific trend or relationship between them and the scatter is random. No evidence of dependence between the predictor and the residuals of both types. The Kendall tau dependency parameter between the predictor and the residuals is -0.1104 with p-value= 0.3171 which is not statistically significant. These values are true for both types of residuals.

Figure 13.

Shows the scatter plot between the life expectancy predictor (transformed) and the randomized quantile residuals and Cox-Snell residuals for the logit model regressing the life expectancy on quality of support network . There is no specific trend or relationship between them and the scatter is random. No evidence of dependence between the predictor and the residuals of both types. The Kendall tau dependency parameter between the predictor and the residuals is -0.1104 with p-value= 0.3171 which is not statistically significant. These values are true for both types of residuals.

Figure 14.

Shows that the curve of the log-log complementary model regressing the water quality on life expectancy is steeper than the curve that models the regression of quality of support network on life expectancy.

Figure 14.

Shows that the curve of the log-log complementary model regressing the water quality on life expectancy is steeper than the curve that models the regression of quality of support network on life expectancy.

Figure 15.

Shows the QQ plot of the empirical vs. the theoretical quantiles for the log-log complementary model where the water quality is regressed on the life expectancy. The randomized quantile residuals show near perfect alignment all through the course of the curve in contrast to the Cox-Snell residuals which show more or less near alignment mainly in the lower tail and center of the curve than the upper tail.

Figure 15.

Shows the QQ plot of the empirical vs. the theoretical quantiles for the log-log complementary model where the water quality is regressed on the life expectancy. The randomized quantile residuals show near perfect alignment all through the course of the curve in contrast to the Cox-Snell residuals which show more or less near alignment mainly in the lower tail and center of the curve than the upper tail.

Figure 16.

Shows the QQ plot of the empirical vs. the theoretical quantiles for the log-log complementary model where the quality of support network is regressed on the life expectancy. The randomized quantile residuals show near perfect alignment all through the course of the curve in contrast to the Cox-Snell residuals which show more or less near alignment mainly in the lower tail and center of the curve than the upper tail.

Figure 16.

Shows the QQ plot of the empirical vs. the theoretical quantiles for the log-log complementary model where the quality of support network is regressed on the life expectancy. The randomized quantile residuals show near perfect alignment all through the course of the curve in contrast to the Cox-Snell residuals which show more or less near alignment mainly in the lower tail and center of the curve than the upper tail.

Figure 17.

Shows the scatter plot between the life expectancy predictor (transformed) and the randomized quantile residuals and Cox-Snell residuals for the log-log complementary model regressing the life expectancy on water quality. There is no specific trend or relationship between them and the scatter is random. No evidence of dependence between the predictor and the residuals of both types. The Kendall tau dependency parameter between the predictor and the residuals is -0.1093 with p-value= 0.3225 which is not statistically significant. These values are true for both types of residuals.

Figure 17.

Shows the scatter plot between the life expectancy predictor (transformed) and the randomized quantile residuals and Cox-Snell residuals for the log-log complementary model regressing the life expectancy on water quality. There is no specific trend or relationship between them and the scatter is random. No evidence of dependence between the predictor and the residuals of both types. The Kendall tau dependency parameter between the predictor and the residuals is -0.1093 with p-value= 0.3225 which is not statistically significant. These values are true for both types of residuals.

Figure 18.

Shows the scatter plot between the life expectancy predictor (transformed) and the randomized quantile residuals and Cox-Snell residuals for the log-log complementary model regressing the life expectancy on quality of support network. There is no specific trend or relationship between them and the scatter is random. No evidence of dependence between the predictor and the residuals of both types. The Kendall tau dependency parameter between the predictor and the residuals is -0.1104 with p-value= 0.3171 which is not statistically significant. These values are true for both types of residuals.

Figure 18.

Shows the scatter plot between the life expectancy predictor (transformed) and the randomized quantile residuals and Cox-Snell residuals for the log-log complementary model regressing the life expectancy on quality of support network. There is no specific trend or relationship between them and the scatter is random. No evidence of dependence between the predictor and the residuals of both types. The Kendall tau dependency parameter between the predictor and the residuals is -0.1104 with p-value= 0.3171 which is not statistically significant. These values are true for both types of residuals.

Figure 19.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the CVM for the logit model depicting the significant of the CVM as the value 0.0032 lies between the 2.5th and the 97.5th quantile. .

Figure 19.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the CVM for the logit model depicting the significant of the CVM as the value 0.0032 lies between the 2.5th and the 97.5th quantile. .

Figure 20.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the intercept coefficient (g0) for the logit model depicting a non-significant coefficient as the zero value lies between the 2.5th and the 97.5th quantile. .

Figure 20.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the intercept coefficient (g0) for the logit model depicting a non-significant coefficient as the zero value lies between the 2.5th and the 97.5th quantile. .

Figure 21.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the slope coefficient (g1) for the logit model depicting the significance of the coefficient as the zero value do not lie between the 2.5th and the 97.5th quantile, and the estimated slope value (-14.6995) lies between these 2 quantiles. .

Figure 21.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the slope coefficient (g1) for the logit model depicting the significance of the coefficient as the zero value do not lie between the 2.5th and the 97.5th quantile, and the estimated slope value (-14.6995) lies between these 2 quantiles. .

Figure 22.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the LRT for the logit model depicting the significance of the ratio as the 4.3426 value does not lie between the 2.5th and the 97.5th quantile, it inhabits the upper tail.

Figure 22.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the LRT for the logit model depicting the significance of the ratio as the 4.3426 value does not lie between the 2.5th and the 97.5th quantile, it inhabits the upper tail.

Figure 23.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the CVM for the log-log complementary model depicting the significant of the CVM as the value 0.0033 lies between the 15th and the 85th quantile.

Figure 23.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the CVM for the log-log complementary model depicting the significant of the CVM as the value 0.0033 lies between the 15th and the 85th quantile.

Figure 24.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the intercept coefficient (g0) for the log-log complementary model depicting a non-significant coefficient as the zero value lies between the 15th and the 85th quantile. .

Figure 24.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the intercept coefficient (g0) for the log-log complementary model depicting a non-significant coefficient as the zero value lies between the 15th and the 85th quantile. .

Figure 25.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the slope coefficient (g1) for the log-log complementary model depicting the significance of the coefficient as the zero value do not lie between the 15th and the 85th quantile, and the estimated slope value (-12.6233) lies between these 2 quantiles.

Figure 25.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the slope coefficient (g1) for the log-log complementary model depicting the significance of the coefficient as the zero value do not lie between the 15th and the 85th quantile, and the estimated slope value (-12.6233) lies between these 2 quantiles.

Figure 26.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the CVM for the log-log complementary model depicting the significant of the CVM as the value 0.0033 lies between the 2.5th and the 97.5th quantile. .

Figure 26.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the CVM for the log-log complementary model depicting the significant of the CVM as the value 0.0033 lies between the 2.5th and the 97.5th quantile. .

Figure 27.

Shows the non-parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the slope coefficient (g1) for the log-log complementary model depicting the significance of the coefficient as the zero value do not lie between the 2.5th and the 97.5th quantile, and the estimated slope value (-12.6233) lies between these 2 quantiles. But this sampling is less powerful than the parametric bootstrap sampling.

Figure 27.

Shows the non-parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the slope coefficient (g1) for the log-log complementary model depicting the significance of the coefficient as the zero value do not lie between the 2.5th and the 97.5th quantile, and the estimated slope value (-12.6233) lies between these 2 quantiles. But this sampling is less powerful than the parametric bootstrap sampling.

Figure 28.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the LRT for the log-log complementary model depicting the significance of the ratio as the 3.8243 value does not lie between the 15th and the 85th quantile, it occupies the upper tail.

Figure 28.

Shows the parametric bootstrap sampling distribution of the LRT for the log-log complementary model depicting the significance of the ratio as the 3.8243 value does not lie between the 15th and the 85th quantile, it occupies the upper tail.

Figure 29.

Shows the estimated dependency parameter vs. the log percentage of the life expectancy for the logit model. As the life expectancy increase, the dependency between the 2 response variables weakens..

Figure 29.

Shows the estimated dependency parameter vs. the log percentage of the life expectancy for the logit model. As the life expectancy increase, the dependency between the 2 response variables weakens..

Figure 30.

Shows the estimated dependency parameter vs. the log percentage of the life expectancy for the log-log complementary model. The dependency between the 2 response variables weakens as the life expectancy increases.

Figure 30.

Shows the estimated dependency parameter vs. the log percentage of the life expectancy for the log-log complementary model. The dependency between the 2 response variables weakens as the life expectancy increases.

Figure 31.

Shows the empirical copula vs. the theoretical copula after applying step 4 of the algorithm using the u& v obtained from the logit regression model in step 3 of the algorithm.

Figure 31.

Shows the empirical copula vs. the theoretical copula after applying step 4 of the algorithm using the u& v obtained from the logit regression model in step 3 of the algorithm.

Figure 32.

Shows the empirical copula vs. the theoretical copula after applying step 4 of the algorithm using the u& v obtained from the log-log complementary regression model in step 3 of the algorithm.

Figure 32.

Shows the empirical copula vs. the theoretical copula after applying step 4 of the algorithm using the u& v obtained from the log-log complementary regression model in step 3 of the algorithm.

Table 1.

The descriptive statistics of the two response variables.

Table 1.

The descriptive statistics of the two response variables.

| indicator |

min |

mean |

Standard deviation |

skewness |

kurtosis |

25percentile |

50percentile |

75percentile |

max |

| Water quality |

0.62 |

0.8332 |

0.0972 |

-0.6059 |

2.9144 |

0.7775 |

0.83 |

0.91 |

0.98 |

| Quality of support network |

0.77 |

0.9078 |

0.0538 |

-1.176 |

3.5406 |

0.89 |

0.93 |

0.95 |

0.98 |

Table 2.

Kendall Tau coefficient between the two response variables.

Table 2.

Kendall Tau coefficient between the two response variables.

| |

Water quality |

Quality of support network |

| Water quality |

1 |

0.3929

(0.0006)

|

| Quality of support network |

0.3929

(0.0006)

|

1 |

Table 3.

Statistical indices for the two response variables.

Table 3.

Statistical indices for the two response variables.

| indicator |

Estimated theta |

variance |

AIC |

CAIC |

BIC |

HQIC |

KS-test |

Ho |

p-value of KS-test |

| Water quality |

0.4776 |

0.00072157 |

-78.9952 |

-78.8926 |

-77.2817 |

-78.3712 |

0.0991 |

Fail to reject |

0.7789 |

| Quality of support network |

0.3444 |

0.00037494 |

-131.651 |

-131.6505 |

-131.5479 |

-131.0265 |

0.1806 |

Fail to reject |

0.1217 |

Table 4.

The results of marginal regression of response variables on the predictor using the logit link function.

Table 4.

The results of marginal regression of response variables on the predictor using the logit link function.

| |

Regressing water quality on life expectancy using the logit link |

Regressing quality of support network on life expectancy using the logit link |

| b0

|

3.0944 |

3.2216 |

| b1

|

5.8750 |

3.4077 |

| LL |

43.2027 |

67.7959 |

| Wald statistics of bo |

4.8932 (p-value <0.025) |

5.5193 (p-value <0.025) |

| Wald statistics of b1 |

2.0702 (p-value <0.025) |

1.3126 (p-value >0.025) |

| AIC |

-82.4053 |

-131.5917 |

| CAIC |

-82.0896 |

-131.2759 |

| BIC |

-78.9782 |

-128.1646 |

| HQIC |

-81.1574 |

-130.3437 |

| LRT ( likelihood Ratio Test) |

5.4102 (p-value=0.02) |

1.9412 ( p-value=0.1635) |

| p-value for the randomized quantile residual |

0.6821 |

0.1079 |

| p-value for the Cox-Snell residual |

0.6821 |

0.1079 |

| Variance-covariance matrix |

0.3999 |

1.7612 |

0.3407 |

1.4842 |

| |

1.7612 |

8.0536 |

1.4842 |

6.7365 |

Table 5.

The results of marginal regression of response variables on the predictor using the log-log link complementary function.

Table 5.

The results of marginal regression of response variables on the predictor using the log-log link complementary function.

| |

Regressing water quality on life expectancy using the log –log complementary link |

Regressing quality of support network on life expectancy using the log-log complementary link |

| b0

|

1.2917 |

1.2317 |

| b1

|

2.848 |

1.3446 |

| LL |

43.3006 |

67.84 |

| Wald statistics of b0 |

4.282 (p-value<0.025) |

5.41 (p-value < 0.025) |

| Wald statistics of b1 |

2.0367 (p <0.025) |

1.297 (p-value > 0.025) |

| AIC |

-82.6011 |

-131.6799 |

| CAIC |

-82.2853 |

-131.3641 |

| BIC |

-79.174 |

-128.2528 |

| HQIC |

-81.3532 |

-130.4319 |

| LRT ( likelihood Ratio Test) |

5.6059 (p-value=0.0179) |

2.2094 ( p-value=0.1543) |

| p-value for the randomized quantile residual |

0.619 |

0.1033 |

| p-value for the Cox-Snell residual |

0.619 |

0.1033 |

| Variance-covariance matrix |

0.091 |

0.4154 |

0.0519 |

0.232 |

| |

0.4154 |

1.9553 |

0.232 |

1.0732 |

Table 6.

Shows the results utilizing the fitted CDFs (u & v) from model of regression, the logit model and the log-log complementary.

Table 6.

Shows the results utilizing the fitted CDFs (u & v) from model of regression, the logit model and the log-log complementary.

| |

after the log-log complementary regression model |

after the logit regression model |

| g0

|

-3.1311 |

-3.6314 |

| g1

|

-12.6233 |

-14.6995 |

| LL |

-70.8383 |

-70.6029 |

| Wald statistics of g0 |

2.509(p-value <0.025) |

2.4176(p-value <0.025) |

| Wald statistics of g1 |

2.6713(p-value <0.025) |

2.58155(p-value <0.025) |

| AIC |

145.6766 |

145.2058 |

| CAIC |

145.9924 |

145.5216 |

| BIC |

149.1034 |

148.6329 |

| HQIC |

146.9246 |

146.4538 |

| CVM |

0.0033 |

0.0032 |

| Empirical tau, (P-value) |

0.3356 (0.0021) |

0.3331 (0.0025) |

| Mean of theoretical tau |

0.4147 |

0.4045 |

| LRT, (P-value) |

3.8243 (0.0505) |

4.3426 (0.0372) |

| Variance-covariance matrix |

1.5569 |

5.7163 |

2.2562 |

8.3667 |

| |

5.7163 |

22.3305 |

8.3667 |

32.4221 |