1. Introduction

Root exportation is an important way for plants to respond to external stress, an important carrier material for transmitting and exchanging rhizosphere soil information, which can regulate rhizosphere dialogue, and is also an important factor in forming rhizosphere microecological characteristics [

1,

2]. Root exudates play an important role in plant biogeochemical cycle, rhizosphere ecological process regulation, plant growth and development, etc [

3]. Fenugreek root exudates significantly stimulated Orobanche seed germination [

4]. Yan identified two important coumarins in the root exudates of Daphne sapiens, which could inhibit the mitosis process of lettuce root tip, affecting the growth [

5]. Intercropping can both reduce the occurrence of plant leaf diseases, and effectively inhibit the spread and expansion of soil-borne diseases [

6,

7,

8]. The control of soil-borne plant diseases is one of the key factors to ensure the sustainable development of agricultural production. With the development of ecology, soil-borne plant diseases have been studied in a new perspective. The accumulation of autotoxins and pathogens in soil is the main driving factor of soil-borne diseases [

9,

10]. Some water-soluble substances detected in the root secretions of leguminous alfalfa can cause serious autotoxicity, and different concentrations have different promoting or inhibiting effects on the growth of surrounding plants [

11]. Allelopathic effects of root exudates from different alfalfa cultivars exhibit significant variation in terms of seed germination inhibition and seedling growth suppression, with more pronounced phytotoxicity observed under long-term continuous monoculture practices [

12].

Root-secreted organic acids, phenolic acids, and terpenoids serve as vital energy sources for soil microorganisms. The diverse components of root exudates differentially influence the composition and abundance of rhizosphere microbial communities [

13]. For example, salicylic acid and jasmonic acid found in Arabidopsis thaliana root exudates can selectively recruit specific microbial taxa, thereby shaping both rhizosphere and endosphere microbiomes and enhancing plant resistance to diseases [

14,

15]. Zhang showed that in rice-watermelon intercropping systems, watermelon roots increase the secretion of phenolic acids, amino acids, and organic acids, which helps reduce the incidence of Fusarium wilt in watermelon [

16]. Likewise, in maize-pepper intercropping, maize root exudates have been found to inhibit the growth and spread of Phytophthora capsici, thus alleviating pepper blight [

17]. These results highlight the strong link between root exudates and soil-borne pathogens. Plants may suppress pathogen proliferation either through the release of specific allelochemicals [

18] or by modifying their root exudate profiles to indirectly alter pathogen behavior [

19]. Gao [

20] reported that cinnamic acid released in soybean-maize intercropping significantly decreases the occurrence of soybean red crown rot. Dong [

21] further demonstrated that tomato-chrysanthemum intercropping induces chrysanthemum roots to secrete lauric acid, which disrupts gene expression in root-knot nematodes and prevents nematode infection in tomatoes. Moreover, in wheat-watermelon intercropping systems, wheat root exudates effectively control Fusarium wilt in watermelon by strongly inhibiting spore germination and mycelial growth of the causal pathogen [

22].

Root rot related and harmful pathogens, as one of the most serious soilborne diseases in the production of mangold and wolfberry [

23], accumulate yearly along with repeated cropping time, leading tothe biggest obstacle to the cultivation of wolfberry. Extensive studies have been conducted on the pathogenic factors of root rot, finding the close relation [

24]. The wolfberry root rot is closely related to phenolic acids in root secretions, and as the cropping years continue, these compounds accumulate in the wolfberry root, restricting the continuous cropping[

25]. By conducting indoor extraction of root exudates from wolfberry and herbage species, this study systematically investigated their effects on seed germination and seedling growth of mangold and wolfberry, while simultaneously evaluating their inhibitory potential against root rot pathogens. The findings are expected to provide robust technical support for elucidating interspecific interactions within the wolfberry-herbage intercropping systems, thereby providing technical references for optimizing cultivation models and scaling up agricultural applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Acquisition of Root Exudates

Sampling types and methods: forage material was nutrient matrix seedling for 30 days of growth, and wolfberry was 3-leaf tissue culture seedling. When sampling, gently shake off the root matrix and obtain the whole plant. After cleaning and disinfection, first culture the plants in the nutrient solution. The nutrient solution should be changed twice a week. After 7 days, repeatedly clean the roots of the well - growing plants with deionized water 2-3 times, and then transfer them to a 25-well hydroponics box containing 1L of sterilized deionized water for culture (25 plants in monoculture; in intercropping, 15 grasses+10 goji berries). During the culture period, regularly replenish water to maintain the volume at 1L, and sample the root exudates on the 21st day of culture.

2.2. Seed Germination Test

After disinfected with 75% alcohol for 3min, disinfected with 3% NaClO for 12 min, washed with distilled water, transferred to petri dishes (10 cm diameter) covered with filter paper, each dish containing 30 seeds, 2 ml root exudates, and 2 ml distilled water (blank control) were dark treated at 28 oC. Three replicates were set for each treatment. The seeded petri dishes were cultured in a light/dark cycle at temperature (28 oC), 16/8h, and the germination of the seeds was observed and recorded daily.

The germination rate of the seeds of the 7 plants was calculated according to the description of germination in the International Code of Seed Inspection. Germination rate (%) = (the number of germinated seeds in each petri dish/the number of seeds sown)×100%, starting from the 5th day, the germination rate of 2-10 days was calculated, and statistical records were made; Germination potential (%) = (the number of germinated seeds on the day with the highest number of germinations/the number of seeds sown)×100%; Vigor index (VI) = (a/1 + b/2 + c/3 +d/4 +... + x/n) x [100/S], where a, b, c, d... 1,2,3,4, respectively. The amount of seeds germinated on day 1, x indicates the amount of seeds germinated on day n, S denotes the number of seeds tested. 10 plants were randomly selected from each petri dish on day 4 and day 7 to measure the plant height and root length, respectively.

2.3. Root Rot Identification Experiment

2.3.1. Root Rot Sampling

Medlar rot root sampling and Medlar Science Research Institute of Ningxia Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences garden farm for more than 6 years root rot seriously harm the test field; mangold rot roots were taken from the mangold planting base in Mazhuang Village, Yanchi County.

2.3.2. Morphological Identification

Mainly referring to previous identification methods [

26,

27], using PDA medium as the base medium, according to 22 oC, 12h light and dark alternating conditions of 96 h colony diameter and culture characteristics; BX51 fluorescence microscope and DIC differential interferometer were used to observe the strain. When the strain grew mycelia, it was immediately transferred to a new PDA plate, and this operation was repeated for 3 times until the pure culture of the strain was obtained. The morphology and structure of the colony on the purified medium were observed, including shape, diameter, color, concavity and mycelia characteristics. Single colony pathogens were selected for preparation and staining with compound red, and mycelia morphology and spore shape were observed under 10x, 20x, 40x eyepiece and 100x oil lens. The observation results were recorded and photographed at the same magnification. After that, the presence, size, morphology and spore-forming mode of large and small conidia were investigated. The presence or non-presence of chlamydospore and the morphology and size of spore-forming stem were identified, and their classification status was determined.

2.3.3. Molecular Biological Identification

The fungal culture was aseptically maintained on PDA medium for 3 days. Mycelial plugs (5 mm diameter) were excised from the advancing colony margin using a sterile cork borer and inoculated into 100 mL of PS liquid medium. The PS medium formulation consisted of potato extract (200 g/L), sucrose (20 g/L), and distilled water (adjusted to 1L total volume). Shake culture at 150rpm at 25 oC for 5-8 days, filter with 4 layers of gauze, rinse with sterilized normal saline twice, then blot with sterilized absorbent paper, store at -20 oC for later use. Universal primers ITS1/ITS4 (ITS1:TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGC, ITS4:TCCTCC GCTTATTGATATGC) and 5f2/7cr (5f2:GGGGWGAYCAGAAGAAGGC,7cr: CCCATRGCTTGYTTRCCCATPCR) were used to amplify the tested strains.

High-quality genomic DNA was extracted and separated by 0.35% agarose-gel electrophoresis. Purity, concentration and integrity were inspected by Nanodrop and Qubit. BluePippin automatic nucleic acid recovery system recovered large fragments of DNA; Library construction and sequencing reactions include: DNA damage repair and end repair, magnetic bead purification; Junction connection, magnetic bead purification; Qubit library quantification; Four steps of computer sequencing (commissioned by Shanghai Bioengineering Co., LTD.). The sequencing results on

http://www, ncbi. While NLM. Nih. Gov database, pathogen identification to species, to clear its classification status.

2.4. Root Exudate Re-Inoculation Experiment

The bacteria cake in the center of the colony formed by activated culture strains on PDA medium (at 28 oC) was cut off with a sterilizing hole punch (with an inner diameter of 5mm), and the bacteria cake was transferred to PDA medium, and the pathogenic bacteria strains of root rot were treated with 1mm root secretions, and cultured at 25 oC under constant temperature and continuous light for 3 days. With the cross-crossing method in 1, 2, 3 days respectively record the colony diameter, the measurement number after subtracting 5mm to get the growth of the strain. 3 repetitions were set for each treatment. BX51 fluorescence microscope and DIC differential interferometer were employed to observe the strains. When the strains grew mycelia, the complete mycelia suitable for observation was selected, and the optimal focal length and magnification were adjusted to image the mycelia. In the imaging image, the mycelia length of the image was calculated according to the magnification of the image. After the mycelia length statistics of the imaging images of three different parts were completed, the mean value was obtained. Each group of three biological repeats was processed, and there were 3 groups in total.

2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

All experimental data were analyzed using Excel v2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and SPSS v17.0 Statistics (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Before statistical analyses, the Chi-square test for normality of the data was conducted. Mean comparisons among treatments were performed using Fisher’s protected least significant difference test when the analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated a significant effect (Fisher’s LSD, P < 0.05)..

3. Results

3.1. Root Exudates’ Influence on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth

The root exudates of wolfberry could promote the seed germination of white clover, mangold and ryegrass, and inhibit the seed germination of alfalfa by 6.91% (P < 0.05). In terms of the effects on the growth of grass seedlings, the root secretions of wolfberry inhibited the growth of ryegrass seedlings by 53.66%, promoted the growth of alfalfa, white clover and mangold seedlings by 75.24%, 46.74% and 6.94% (

Table 1). The seed germination test of four kinds of grass root secretions demonstrated that except for four kinds of grass, there were no significant inhibitory effects on the seed germination of wolfberry (P>0.05). The root exudates of the four forage species significantly promoted the seedling growth of wolfberry seeds (P<0.05) (

Table 2).

3.2. Pathogens of Wolfberry Root Rot Identification

3.2.1. Morphological Identification of Pathogens to Wolfberry Root Rot Disease

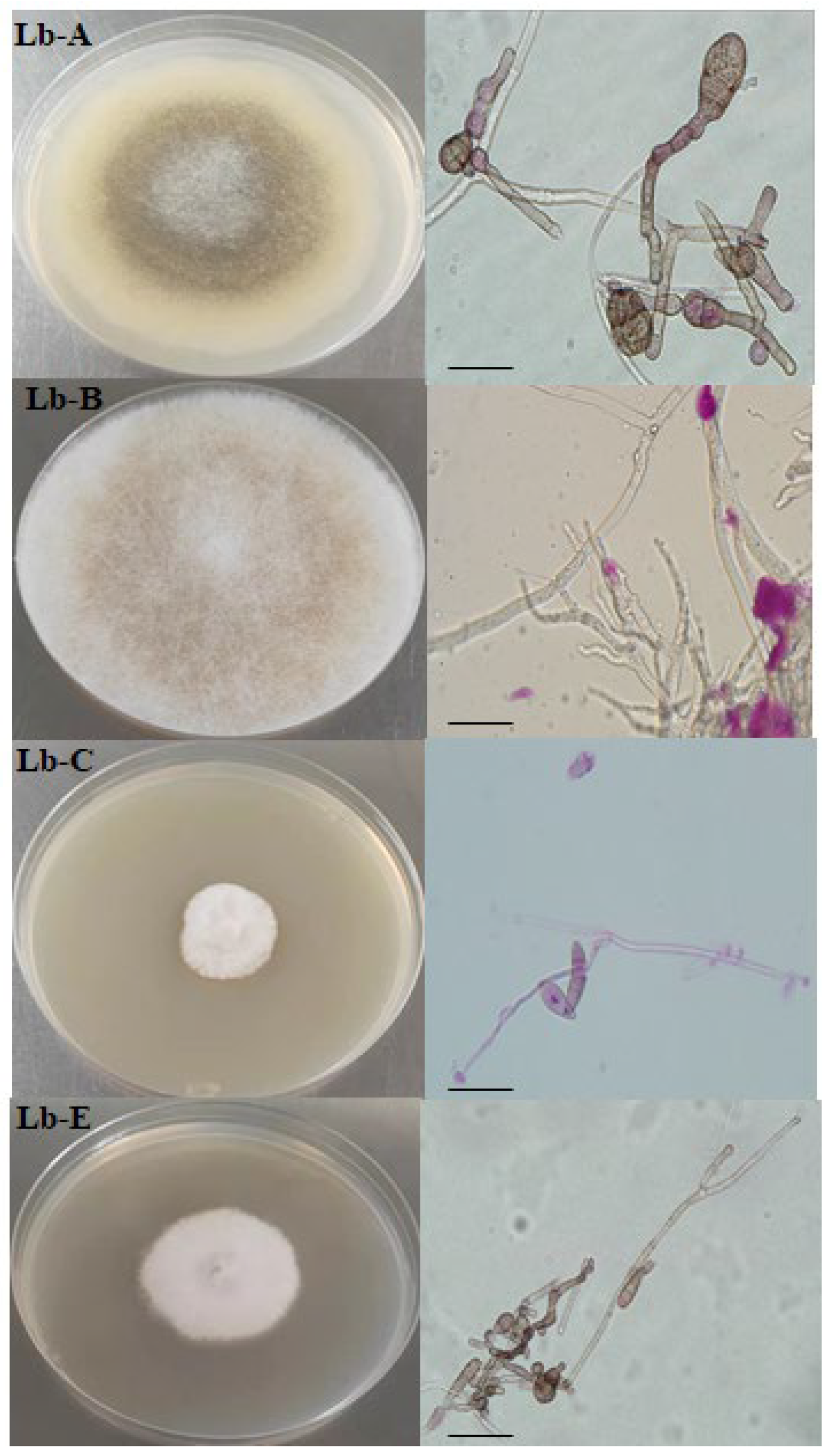

The roots of the root rot from the planting base of wolfberry in the garden were cultured, and four dominant strains were selected. The identification was made according to the presence of large or small conidium, chlamydospore, the size, morphology and mode of sporulation of conidium, and the morphology and size of sporulation stem, which can be seen in

Figure 1. Lb-A mycelium was white, transparent, branched and without transverse septum in early stage, which was divided into latent trophic mycelium and gaseous creeping mycelium, and cyan and black in the late stage. Spore peduncle grew from stolon mycelium, unbunched, solitary, without rhizomes; Sporangium terminal, globular, colorless at first, grayish brown later. The spores of the pathogen Lb-B have no septum, and the apical branches are broom-like, asymmetrical or symmetrical. The sporangium stems are single from the mycelium, branched or unbranched. The colony is white at the beginning, evenly distributed, and the mycelium is long and dense, and the whole becomes black at the latter stage. Lb-A and Lb-B were preliminarily identified as Mucor or rhizopus. Small conidium and chlamycospore were observed in the colony of strain Lb-C, which were white and flocculant, mycelium was septate, and the air mycelium was slightly higher arachnoid, and light red pigment was produced in the later stage, which was most obvious at the bottom of the petri dish. The airborne mycelia formed by strain LP-E on the PDA medium were fluffy, white or powdery white. With the growth of mycelia, bluish gray mycelia clusters could be seen on the front side. The large conidia were sickle-shaped and slightly curved, the small conidia were oval, and the interhyphal or apical chlamydia spores were observed. Lb-C and Lb-E were preliminarily identified as one kind of Fusarium.

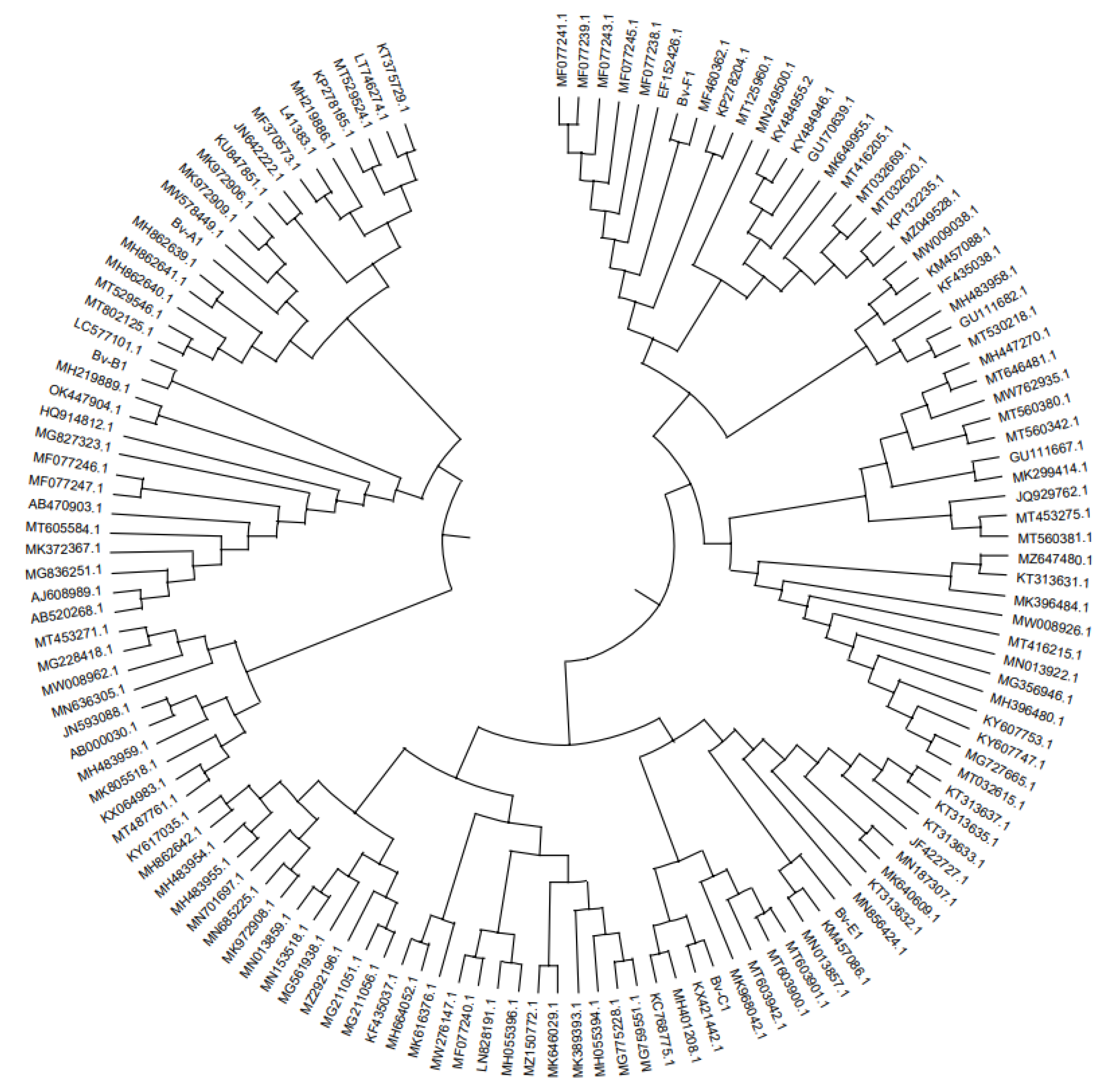

3.2.2. Molecular Biological Identification

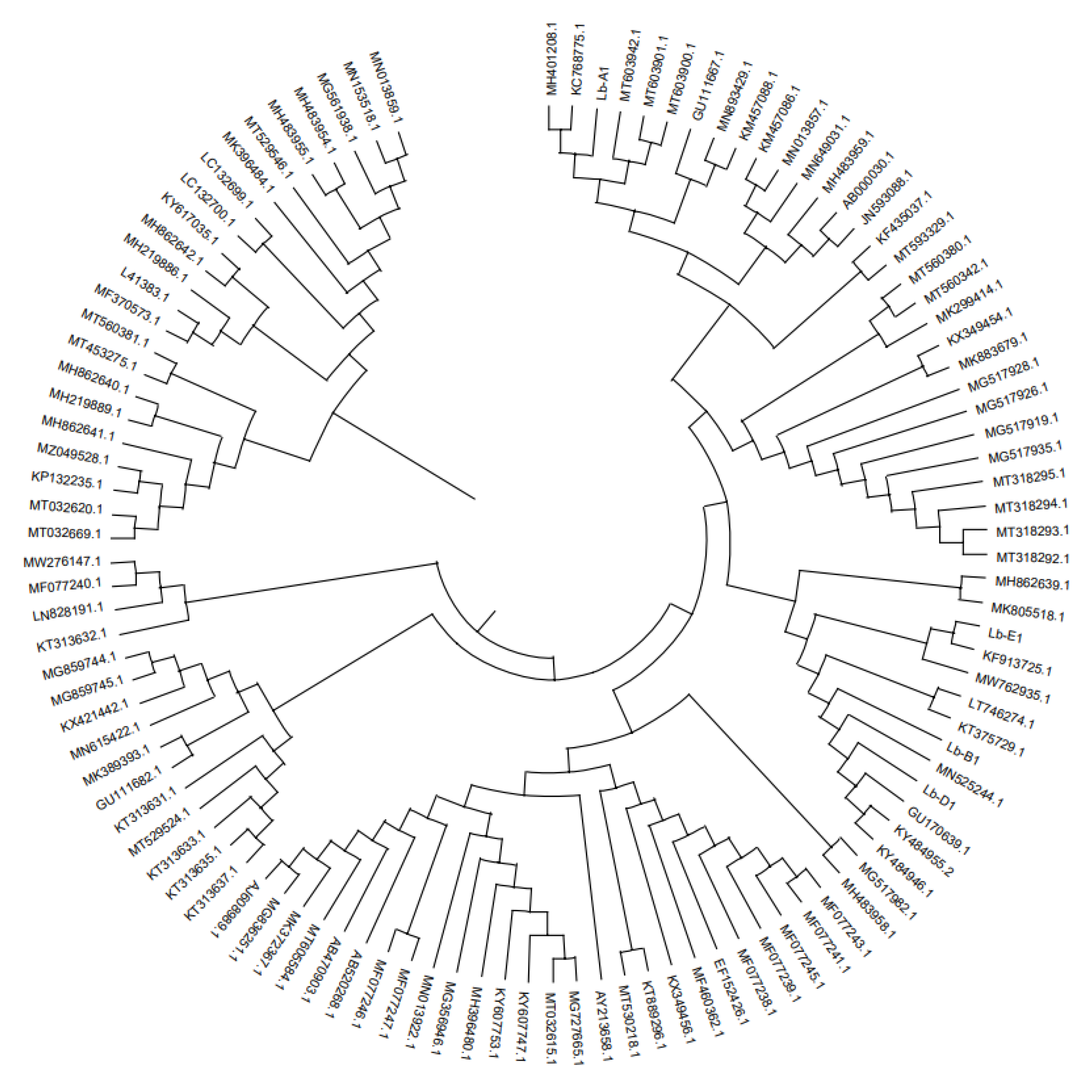

The rDNA sequences of each related species were selected from Genbank database, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed with the tested strains. DNA sequence was analyzed using NCBI sequence comparison tool BLAST (http: nucleotide blast of blast.ncBI.nlm.nih.gov) program compares and analyzes the sequence obtained by cloning, Clustal X compares and analyzes multiple sequences, MEGA X Neighbor-joining method builds evolutionary tree. Where the number of repetition is set to 1000.

The second major subgene (RPB2) of root rot pathogen RNA polymerase Ⅱ was amplified by 5f2/7cr primer. The results of 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis showed that the Lb-A1 sequence of wolfberry root rot strain was compared with Mucor circinelloides (MT603942.1: Mucor circinelloides was 99.67% similar; The similarity between Lb-B1 and Rhizopus arrhizus (MN525244.1: Rhizopus) was 100%. The similarity between Lb-C1 and Fusarium solani (GU170639.1: Fusarium arrhizus) was 100%. The similarity between Lb-E1 sequence and Fusarium oxysporum (KF913725.1: Fusarium oxysporum) was 100%.

The sequence was amplified by primer ITS1/ITS4, the 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis showed that the similarity between Lb-A2 and Rhizopus arrhizus (MK174988.1: Rhizopus) was 77%. The similarity between Lb-B2 and Fusarium oxysporum (MT560342.1: Fusarium oxysporum) was 91%. The similarity between Lb-C2 sequence and Fusarium solani (MN013859.1: Fusarium fusarium) was 100%; And the Lb-E2 sequence was 100% similar to Fusarium oxysporum (KF574854.1: Fusarium oxysporum). The pathogens related to the root rot disease of wolfberry were identified as Mucor cirlocladus (Lb-A), Rhizopus (Lb-B), Fusarium dermatitis (Lb-C) and Fusarium oxysporum (Lb-E). (

Table 3,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

3.3. Pathogenic Bacteria of Mangold Root Rot Identification

3.3.1. Morphological Identification of Pathogens Related to Mangold Root Rot

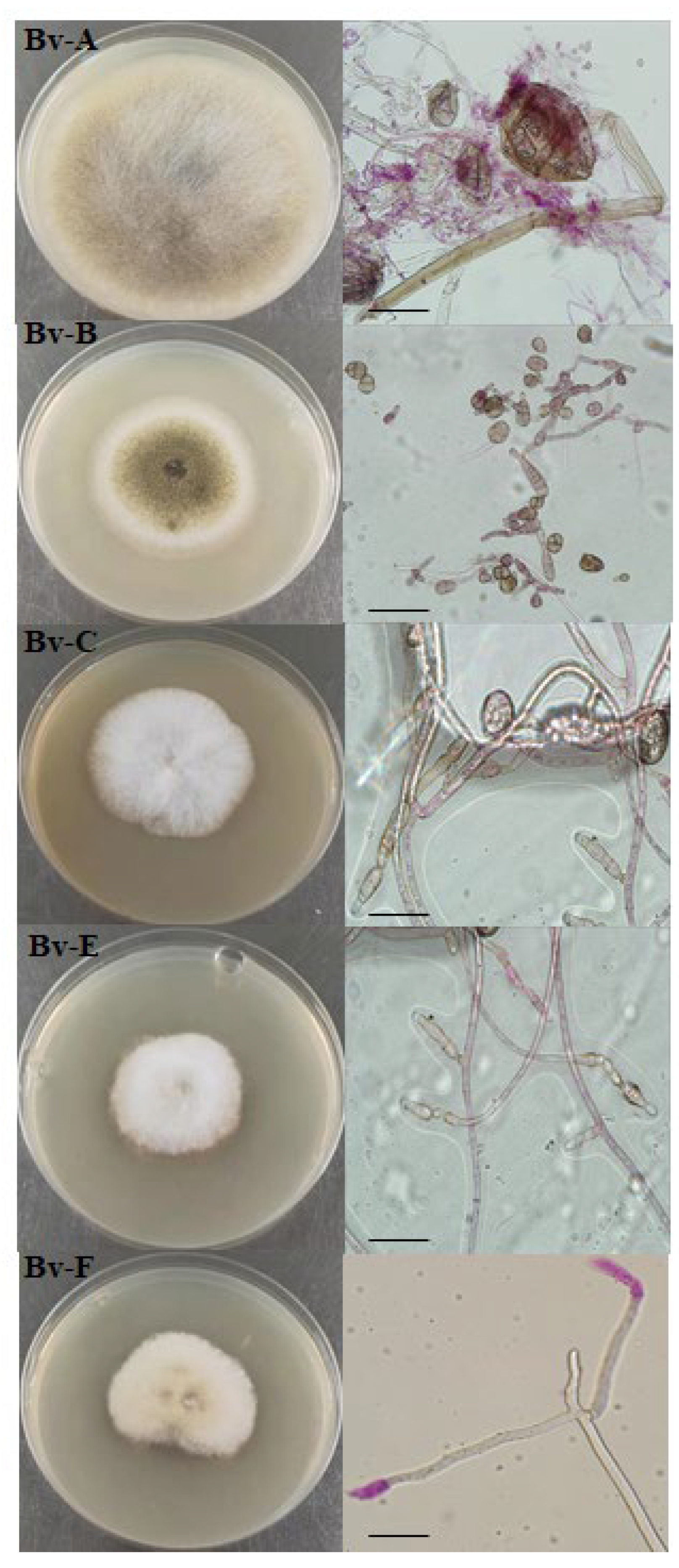

After separating and purifying the diseased roots, five dominant strains were selected for classification and identification, and morphological identification was conducted according to the presence or not of large and small conidia, the size, morphology and production mode of conidia, the shape and size of sporogenous stem, and the presence or not of chlamydospore, these results were presented in

Figure 4.

The mycelia of Bv-A had no rhizomes, unbunched sporangium, solitary, dense stratified, erect, uniaxial or pseudouniaxial branching, and all apical sporangium. Sporangium is large, spherical, oval or irregular. Preliminary identification as mold. Bv-B colony 1-2cm or smaller in diameter, slow growth in the later period, gry-green colony, with obvious shape in the middle, dense short villi, dry appearance, the apex of conidial pedicle expanded into an apical sac, generally spherical, preliminary identification as kojase. Bv-C colony was white at the early stage, with short villi erect and uninterleaved. The colony was thin and its thickness increased from inside to outside. Most of the small conidia were single cells with septa, and most of the shapes were ovate or fusiform. The Bv-E colony was white in the early stage, and turned yellow in the later stage, with deepened color; The villi were long and interlaced like cotton wool, and the colonies were thick, and the middle was higher than the edge; Conidium scattered on air mycelium or conidium seat, sickle-shaped and fusiform, with obvious separation, and more separation number. The Bv-F colony was thick and light yellow, and the spreading rate of colony diameter was low. Air mycelium, conidium mostly single cell, or very few microspores. Bv-C, Bv-E and Bv-F were identified as a species of Fusarium.

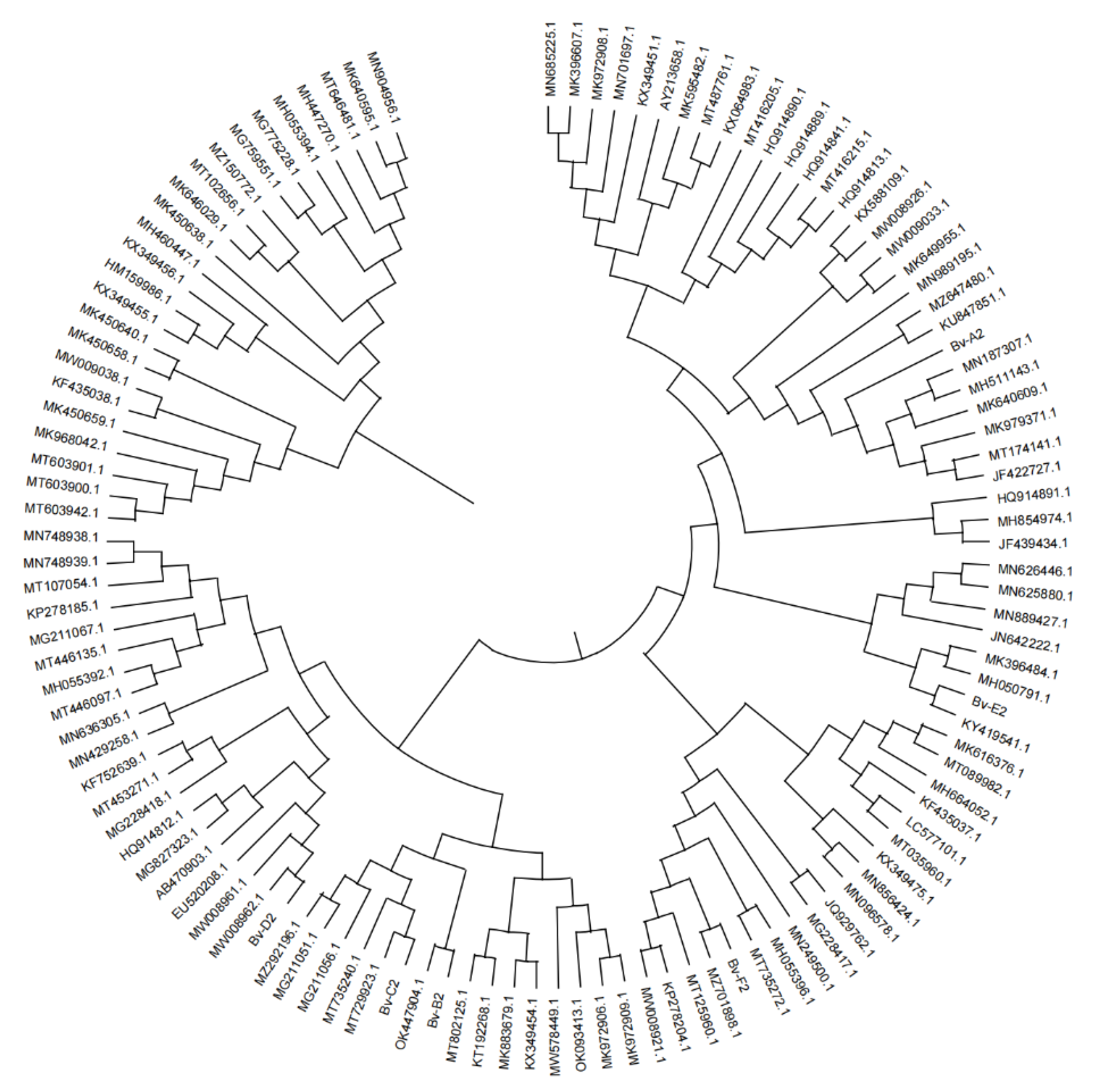

3.3.2. Molecular Biological Identification

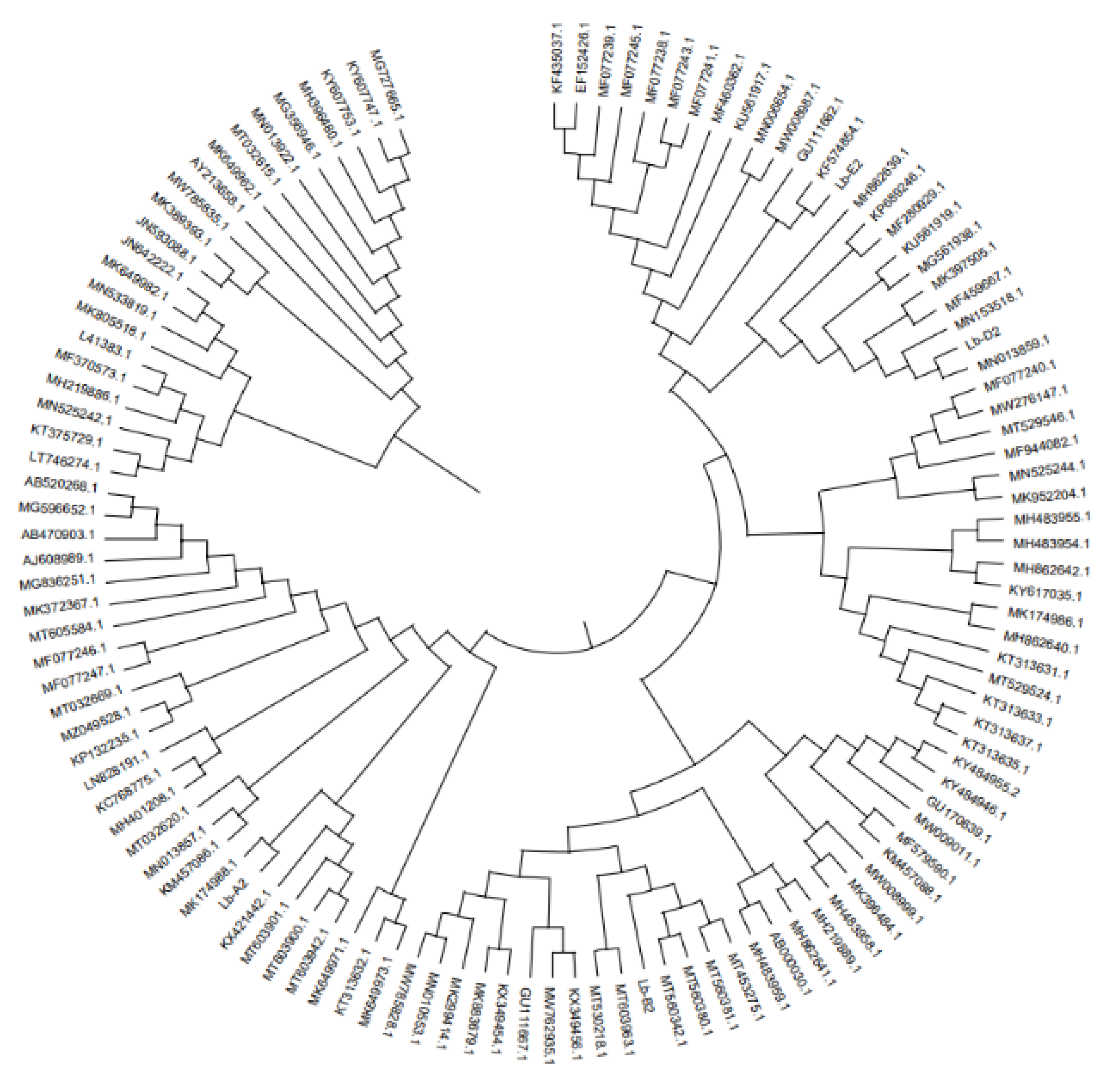

The sequencing data were employed to search and screen for the rDNA sequences of related species of each strain in the GenBank database. A phylogenetic tree was constructed via the related species and the tested strain. DNA sequences were sequenced using NCBI sequence alignment tool BLAST (http: nucleotide blast of blast.ncBI.nlm.nih.gov) program, by comparing and analyzing the sequence obtained by cloning, Clustal X compares and analyzes multiple sequences, MEGA X Neighbor-joining method builds evolutionary tree. The number of repetition is set to 1000.

The second sub-gene (RPB2) of the root-rot pathogen’s RNA polymerase II was amplified using the 5f2/7cr primer. The 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis indicated that the Bv-A1 sequence of the mangold root-rot strain showed high homology with Mucor circinelloides (MW578449.1: Mucor circinelloides) and clustered together; Bv-B1 had high homology with Aspergillus niger (LC577101.1: Aspergillus niger) and was clustered together; Bv-C1 had high homology with Fusarium solani (KX421442.1: Fusarium solani) and clustered together; Bv-E1 had higher homology with Fusarium solani (KM457086.1: Fusarium solani) and clustered together; Bv-F1 sequences had higher homology with Fusarium solani (MF460362.1: Fusarium solani) and clustered together.

The sequence was amplified by primer ITS1/ITS4, and 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis showed that the Bv-A2 sequence of the mangold root putrid disease strain had high homology with Penicillium solitum (JN642222.1: Penicillium). Bv-B2 had high homology with Aspergillus niger (LC577101.1: Aspergillus Niger) and clustered together. Bv-C2 had high homology with Fusarium solani (KP132235.1: Fusarium fusarium fusarium) and clustered together; Bv-E2 had higher homology with Fusarium solani (KY484946.1: Fusarium fusarium) and clustered together; And Bv-F2 sequences have higher homology with Fusarium solani (KT313632.1: Fusarium fusarium), clustered together. The pathogenic bacteria associated with mangold root rot were identified as mold (Bv-A), Aspergillus Niger (Bv-B) and Fusarium solani (Bv-C~E) (

Table 4Figure 5and

Figure 6).

3.4. Root Exudates’ Effect on Pathogenic Bacteria of Root Rot Disease

3.4.1. Acquisition of root exudates

The well-grown monocroponic material cultured in the 25-well hydroponics box was selected, and the roots were repeatedly cleaned with sterilized deionized water for 2 to 3 times. The 5 plants in 1 group were placed in a beacher, cultured with 100ml sterilized deionized water for 24h, then the water was poured out for repeated operations, and the root exudates were collected after 48h of re-culture. The enriched liquid was filtered and dried, then methanol was added, and the residue on the bottle wall was eluted by an ultrasonic oscillator. After the methanol was completely volatilized, the root exudates were obtained by repeated washing for 2 to 3 times and dissolved in 100ml sterilized deionized water.

3.4.2. Effects of Different Root Secretions on the Plaque Size of Pathogenic Bacteria Related to Wolfberry Root Rot Disease

In the medium containing CK, Lb-A had the maximum values in both plaque diameter and mycelial growth rate. It also showed significant differences when compared with the root exudates of the three herbage species. This indicates that the root exudates of alfalfa, white clover, ryegrass, and mangold can effectively inhibit the growth of these bacteria. Moreover, ryegrass and mangold have significant effects on inhibiting the spread of the strain and mycelial growth. In the medium containing CK, Lb-B had the smallest plaque diameter, and showed significant difference from the root exudates of the 3 forage species. There was no significant difference in mycelial growth rate between CK and Lp and Bv. The root exudates of Ms and Tr were significantly higher than those of CK. In the medium treated with Ms and Tr root secretions, Lb-C had the largest plaque diameter, which was significantly different from other treatments, while the mycelial growth rate was the smallest. Ryegrass root exudates treated medium had significant differences with the control in both plaque diameter and mycelia growth rate, and significantly inhibited the growth of this strain. The root secretion of mangold inhibited the growth of these strains to a certain extent, and ryegrass showed a more significant inhibitory effect on Lb-C bacteria. In the medium containing CK, both the plaque diameter and mycelial growth rate of the Lb-E strain reached their maximum values. When compared with the root secretions of the three herbage species, significant differences were observed. This indicates that the root secretions of alfalfa, white clover, ryegrass, and mangold can effectively inhibit the growth of this bacterium. Moreover, mangold and white clover have more significant inhibitory effects on the Lb-E strain. The root exudates of wolfberry promoted the expansion of plaque and mycelia growth of fusarium oxysporum in the root rot of wolfberry (

Table 5).

The root exudates of mangold and ryegrass significantly inhibit the development of wolfberry root rot. The root exudates of alfalfa and white clover can promote the expansion of fungal colonies of Rhizopus, Aspergillus niger, and Fusarium solani, but they inhibit the mycelial growth of pathogens associated with root rot disease. The roots of alfalfa and white clover may contain certain compounds, which promote the growth and reproduction of other two kinds of pathogens. The existence of self-toxic compounds in root exudates of wolfberry can aggravate the harm of root rot (

Table 6).

3.4.3. Effects of Different Root Exudates on the Plaque Size of Pathogenic Bacteria Related to Root Rot Disease of Mangold

Both the plaque diameter and mycelial growth rate of Bv-A in the CK medium were the maximum values, and there were significant differences in plaque diameter between BV-A and the three kinds of grass root exudes. The mycelial growth rate of ryegrass showed significant difference; It indicated that the root exudates of ryegrass could effectively inhibit the growth of Bv-A bacteria, and the root exudates of wolfberry also had a certain inhibitory effect, but the effect was not significant. The plaque diameter of Bv-B was the largest in the medium containing CK, and it was significantly different from that of alfalfa and ryegrass root exudates. In addition, the growth rate of mycelium was the maximum after treatment of alfalfa and white clover root exudates, and there was no significant difference compared with control and ryegrass treatment, but there was significant difference compared with wolfberry root exudates. The plaque diameter of Bv-C and Bv-E on Ms, Tr and Lb treated media was significantly increased than that of the control. In terms of mycelial growth rate, ryegrass, alfalfa and white clover showed inhibitory effect, and white clover showed the most significant inhibitory effect, while Lb root exude treatment showed the promotion effect (P < 0.05). The plaque diameter of BV-F strain was the largest on the medium treated with Bv, which had no significant difference compared with Lb treatment, but showed significant difference compared with Ms, Tr, Lp and CK (P < 0.05). Mycelial growth rate decreased significantly under Tr and Lp root secretion treatment, but there was no significant difference in other strains (

Table 7).

The five root exudations had different effects on the five root rot pathogens of mangold. The root exudations of Lycium berry promoted the expansion of Fusarium fusarium and mycelium growth. Alfalfa and white clover promoted the expansion of Fusarium solani colonies but inhibited mycelial growth, which was basically consistent with their effects on wolfberry root - rot disease. Ryegrass root exudates could significantly reduce the incidence of mangold root rot. The root exudates of mangold promoted the occurrence of root rot, but there was no significant change (P > 0.05) (

Table 8).

4. Discussion

4.1. Root Exudates Play a Significant Role in Modulating Interspecific Plant Interactions

Root exudates are diverse organic compounds actively or passively secreted by plant roots into the rhizosphere, encompassing sugars, amino acids, organic acids, phenolic compounds, and enzymes [

28] (Kong et al., 2018). These exudates play a pivotal role in plant disease resistance through multiple mechanisms, including direct inhibition of pathogens, modulation of the rhizosphere microbial community, and induction of systemic immunity [

29,

30]. The composition and profile of root exudates vary markedly among plant species and genotypes, resulting in differential impacts on pathogenic microorganisms. Our findings demonstrate that root exudates from various plant species, including Lycium barbarum, promote mycelial growth and conidial germination of Fusarium oxysporum. In contrast, Ma [

31] reported that exudates from disease-resistant plant varieties frequently suppress the growth of soil-borne pathogens, whereas those from susceptible varieties lack inhibitory effects and may even enhance pathogen proliferation. These contrasting results suggest a potential link between root exudate-mediated allelopathic effects and plant disease resistance, highlighting the need for comparative studies across crop varieties with differing resistance profiles. To date, such allelopathic effects have been documented in several solanaceous crops, notably tobacco [

31]. However, research on the role of root exudates in wolfberry resistance to root rot were closely related solanaceous species—remains scarce and largely relies on preliminary findings from our research group. Moreover, intercropping systems involving wolfberry have been shown to reshape the rhizosphere micro-ecological environment, primarily by altering the structure and composition of root exudates, thereby improving both yield and quality [

32,

33,

34]. Our studies further confirm that root exudates exert significant influence on the development of soil-borne diseases. Identifying the specific bioactive compounds underlying these effects will be a key focus of future research.

4.1. Effects of Allelopathic Compounds in Root Exudates on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth

Plants can detect and respond to neighboring plants, playing an essential role in plant coexistence and community assembly [

28]. Compared with the independent germination and growth of herbage, treatment of wolfberry root exude could promote the germination of clover, mangold, ryegrass and oat seeds, and the germination and growth of clover, mangold, sweet sorghum, alopecas and alfalfa seeds, while other herbage demonstrated inhibitory effects, consisting with the results reported by Liu et al that root exudates and exogenous allelopathic compounds ferulic acid significantly inhibited the emergence rate of ginseng seeds and the higher morphological indices of seedlings [

4]. Distinct grass root exudates did not significantly inhibit the germination of Lycium berry seeds, but significantly promoted the growth of seedlings, especially clover and alfalfa of legumes. This is in line with the study of Sun [

35] extracts from different parts of wheat and alfalfa all inhibited cotton seed germination, wheat extracts showed low concentration promotion on the growth of cotton seedlings [

36].

4.3. Effects of Root Exudates on Soil-Borne Diseases

The control of plant root rot is one of the key factors to ensure the sustainable development of agricultural production. Intercropping can reduce the occurrence of plant leaf diseases, and effectively inhibit the spread and expansion of soil-borne diseases [

6,

7,

8]. The root secretions secreted by wolfberry and mangold on the whole promoted the occurrence of their own root rot disease, although not significantly, but both of them promoted the expansion of fusarium plaque and mycelium growth. This is consistent with the results [

37] and enhance the pathogenic ability of pathogenic bacteria, aggravating the occurrence and harm of panax notoginseng root rot. The root exudates of alfalfa and white clover can promote the growth of Rhizopus arrhizus in wolfberry root rot and Aspergillus niger and Fusarium solani in mangold root rot. However, it inhibited the spread and propagation of root-rot-related pathogens. The interaction between these two effects helped peppers resist the occurrence of Phytophthora blight, observed in [

38,

39].

Wolfberry is restricted by the shortage of land resources and planting habits in the natural producing areas, and the obstacles of continuous cultivation are becoming more and more prominent [

40]. We found that the root exudates of different herbage had different effects on the pathogenic bacteria of wolfberry root rot, and the root exudates of ryegrass and mangold had obvious inhibitory effects on wolfberry root rot, especially on mucor fritillaris, Fusarium and Fusarium oxysporum. Previous studies on the root exudes of ryegrass and mangold have been few, but benzooxazines (BX) secreted by the roots of other grasses have been extensively studied as important herbivores and pathogen resistance factors. HU found that the roots of wheat and corn and other grasses generally release a class of defensive secondary metabolites, benzooxazines [

41]. Mangold root rot is an important factor threatening the sustainable and stable development of the mangold industry [

42]. The root exudates of wolfberry can significantly inhibit the growth and spread of Fusarium in mangold root rot.

5. Conclusions

This study explores the effects of forage grass root exudates on seed germination, growth, and root rot pathogens of wolfberry via continuous tests. The findings can be summarized as follows: (1) The root exudates of different herbage had distinct effects on seed germination and seedling growth of wolfberry. The root exudates of wolfberry had different effects on seed germination and seedling growth of different herbage, and could promote seed germination of ryegrass, clover and mangold, and germination and growth of alfalfa, clover and mangold. A comprehensive analysis indicates that the intercropping of wolfberry with mangold and alfalfa yields superior performance. (2) In terms of morphological and molecular biological identification, the main pathogens of the root rot disease of wolfberry were mucor cirriculus, rhizopus, Fusarium pistiformis and Fusarium oxysporum; The main pathogens of mangold root rot were mold, aspergillus Niger and Fusarium pistiformis; (3) Root secretions of wolfberry and mangold can promote root rot in these plants. Some plants produce autotoxic substances that limit their own growth and encourage root rot. Root exudates from different forage grasses have varying effects on wolfberry root rot pathogens. Ryegrass secretions strongly inhibit pathogens like Mucor penicillium, Fusarium pistiformis and Fusarium oxysporum. Alfalfa and white clover secretions promote fungal growth in wolfberry and mangold root rot, but inhibit some Fusarium species. Mangold secretions reduce wolfberry root rot but worsen their own.

Author Contributions

Xiaoying Li: Methodology, Writing-original draft. Lizhen Zhu: Conceptualization, Writing - review, editing & Software, Funding acquisition, Visualization, Formal analysis. Jun He: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – review. Xiongxiong Nan: Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Funding acquisition. Fang Wang: Writing-review & editing, methodology, editing & Software, Funding acquisition. Yali Wang: Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation. Hao Wang: Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation. Yu Li: Visualization, Investigation, literature search, data collection. Xinru He: Formal analysis, Software, data collection, Investigation. Yuchao Chen: Methodology, Data curation, Investigation. Ken Qin: Study design, methodology ,Resources, Supervision.

Funding

This research is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Ningxia (2024AAC03769, 2024AAC03768, 2024AAC03387, 2024AAC03129), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 42561010) and the Key Research and development of Ningxia (Talent special) (2024BEH04070).

Data Availability Statement

All the data can be obtained by contacting the author.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Ningxia and the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Key Research and development of Ningxia (Talent special).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hazrati, H.; Fomsgaard, I.; Kudsk, P. Root-Exuded Benzoxazinoids: Uptake and Translocation in Neighboring Plants. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.Q.; Kong, C.H.; Wang, P.; et al. Root exudate signals in plant–plant interactions. Plant, Cell & Environment 2021, 44, 1044–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frémont, A.; Sas, E.; Sarrazin, M.; et al. Phytochelatin and coumarin enrichment in root exudates of arsenic-treated white lupin. Plant, Cell & Environment 2022, 45, 936–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FERNÁNDEZ-APARICIOM; ANDOLFIA; EVIDENTEA; et al. Fenugreek root exudates show species-specific stimulation of Orobanche seed germination. Weed Research 2008, 48, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wang, D.; Cui, H.; et al. Phytotoxicity mechanisms of two coumarin allelochemicals from Stellera chamaejasme in lettuce seedlings[J]. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 2016, 38, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadfield, V.G.A.; Hartley, S.E.; Redeker, K.R. Associational resistance through intercropping reduces yield losses to soil-borne pests and diseases[J]. New Phytologist 2022, 235, 2393–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Robert, C.; Selma, C.; et al. Root exudate metabolites drive plant-soil feedbacks on growth and defense by shaping the rhizosphere microbiota[J]. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, R.; Hu, H.; Wu, X.; et al. Intercropping oilseed rape as a potential relay crop for enhancing the biological control of green peach aphids and aphid-transmitted virus diseases[J]. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 2019, 167(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson-Benavides, B.A.; Dhingra, A. Understanding Root Rot Disease in Agricultural Crops[J]. Horticulturae 2021, (2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Fen, L.; Guo, C.; et al. Negative plant-soil feedback driven by re-assemblage of the rhizosphere microbiome with the growth of Panax notoginseng[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanjun, Saihenna; Yamei, Shimei; et al. Allelopathic effects of alfalfa ( Medicago sativa ) in the seedling stage on seed germination and growth of Elymus nutans in different areas[J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2019, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Shi, S.L.; Li, X.L.; et al. Effects of Autotoxicity on Alfalfa (Medicago sativa): Seed Germination, Oxidative Damage and Lipid Peroxidation of Seedlings[J]; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannipieri, P.; Ascher, J.; Ceccherini, M.T.; et al. Effects of Root Exudates in Microbial Diversity and Activity in Rhizosphere Soils[J]. In soil biology; 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeis, S.L.; Paredes, S.H.; Lundberg, D.S.; et al. PLANT MICROBIOME. Salicylic acid modulates colonization of the root microbiome by specific bacterial taxa[J]. Science 2015, 349(6250). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalhais, L.C.; Dennis, P.G.; Badri, D.V.; et al. Linking Jasmonic Acid Signaling, Root Exudates, and Rhizosphere Microbiomes[J]. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2015, 28, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, R.; Wu, P.; et al. Responses of Root Exudates in Watermelon/Upland Rice Intercropping Systems to the Alleviation of Watermelon Fusarium Wilt[J]. Acta pedologica sinica 2014, 51, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Yang Min; et al. Plant-Plant-Microbe Mechanisms Involved in Soil-Borne Disease Suppression on a Maize and Pepper Intercropping System[J]. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, W.Y.; Ren, L.X.; Ran, W.; et al. Allelopathic effects of root exudates from watermelon and rice plants on Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. niveum[J]. Plant & Soil. 2010, 336(1-2), 485–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.X.; Zhang, N.; Wu, P.; et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization alleviates Fusarium wilt in watermelon and modulates the composition of root exudates[J]. Plant Growth Regulation 2015, 77, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wu, M.; Xu, R.; et al. Root Interactions in a Maize/Soybean Intercropping System Control Soybean Soil-Borne Disease, Red Crown Ro[J]. Plos One 2014, 9, e95031. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; Li, X.; Li, H.; et al. Lauric acid in crown daisy root exudate potently regulates root-knot nematode chemotaxis and disrupts Mi-flp-18 expression to block infection[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany 2014, 131–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Liu, D.; Wu, F.; et al. Root exudates of wheat are involved in suppression of Fusarium wilt in watermelon in watermelon-wheat companion cropping[J]. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2015, 141, 209–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FARQUHARML; PETERSONRL Induction of protoplast formation in the ectomycorrhizal fungus Paxillus involutus by the root rot pathogen Fusarium oxysporum[J]. New Phytologist 1990, 116, 107–113. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.M.; Qiu, H.Z.; Zhang, C.H.; et al. Identification of chemicals in root exudates of potato and their effects on Rhizoctonia solani[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology 2015, 26, 859. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zeng, M. A study on allelopathy and analysis of allelochemicals in rhizosphere soil in orchards with continuous cropping of pear[J]. Journal of Fruit Science 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smilanick, J.L. Postharvest Diseases of Fruits and Vegetables[J]. Postharvest Biology & Technology 2001, 31, 213. [Google Scholar]

- 39Benichou, M.; Ayour, J.; Sagar, M.; etal. Postharvest Technologies for Shelf Life Enhancement of Temperate Fruits[J]; 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.H.; Zhang, S.Z.; Li, Y.H.; et al. Plant neighbor detection and allelochemical response are driven by root-secreted signaling chemicals[J]. Nature Communications 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Rahman et, a.l. Francisco. Interspecific plant interaction via root exudates structures the disease suppressiveness of rhizosphere microbiomes[J]. Molecular Plant 2023, 16, 849–864. [Google Scholar]

- Afridi, M S; Kumar, A; Javed, M A. Harnessing root exudates for plant microbiome engineering and stress resistance in plants[J]. Microbiological Research 2024, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, Y. Atale for two roles: Root-secreted methyl ferulate inhibits, P. nicotianae and enriches the rhizosphere Bacillus against black shank disease in tobacco[J]. Microbiome 2025, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L*; He, J; Tian, Y. Intercropping Wolfberry with Gramineae plants improves productivity and soil quality[J]. Scientia Horticulturae 2022, 292, 110632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.*.; Li, X.; He, J.; et al. Development of Lycium barbarum –Forage Intercropping Patterns[J]. Agronomy 2023, 13(5). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Zhu, L.*.; He, J.; et al. Selecting appropriate forage cover crops to improve growth, yield, and fruit quality of wolfberry by regulation of photosynthesis and biotic stress resistance[J]. Scientia Horticulturae 2024, 337, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.Z.; Liu, J.G.; Chen, H.W.; et al. The chemical sensitivity effect of wheat and alfalfa straw extract on cotton[J]. Acta Agriculturae Boreali-occidentalis Sinica 2018, 27, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, S.K.; Wendt, C.W.; Gannaway, J.R.; et al. Allelopathic Effects of Wheat Straw on Cotton Germination, Emergence, and Yield[J]. Crop Science 1989, 29(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, M.; Yin, R.; et al. Autotoxin Rg1 Induces Degradation of Root Cell Walls and Aggravates Root Rot by Modifying the Rhizospheric Microbiome[J]. Microbiology Spectrum 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jiao, Y.; et al. Tobacco Rotated with Rapeseed for Soil-Borne Phytophthora Pathogen Biocontrol: Mediated by Rapeseed Root Exudates[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016, 7, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Mei, X.; et al. Phenolic Acids Released in Maize Rhizosphere During Maize-Soybean Intercropping Inhibit Phytophthora Blight of Soybean[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, X.; et al. Allelopathic effects of phenolic acids on the growth and physiological characteristics of strawberry plants[J]. Allelopathy Journal 2015, 35, 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, J.; et al. Long-Term Intercropping With Nitrogen Management to Improve Soil Quality and Control Crop Diseases[J]. Plant, Cell & Environment 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FARQUHARML; PETERSONRL Induction of protoplast formation in the ectomycorrhizal fungus Paxillus involutus by the root rot pathogen Fusarium oxysporum[J]. New Phytologist 1990, 116, 107–113. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).