1. Introduction

In recent decades, attitudes toward diversity have undergone significant transformations across Europe, with younger generations generally exhibiting greater openness to ethnic, religious, and cultural differences [

1,

2,

3]. Nevertheless, concerns about immigration and multiculturalism persist, particularly in regions shaped by complex historical and socio-political legacies. Montenegro, a multiethnic country at the intersection of Eastern and Western influences, presents a unique case for examining these dynamics. As a post-socialist and post-conflict society navigating the process of European integration, Montenegro reflects both aspirations for democratic inclusivity and the enduring weight of nationalist discourse.

Tolerance is not only a social value but also a critical competency for sustainable development. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 4.7 calls on higher education to promote knowledge, skills, and values that foster sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, and a culture of peace. Within this framework, tolerance can be understood as both an outcome of inclusive education and a prerequisite for building cohesive, sustainable societies.

Recent bibliometric and systematic reviews of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in higher education identify three major research clusters—(1) sustainability management and governance in universities, (2) sustainability competencies, and (3) implementation and curriculum integration [

4,

5,

6]. These studies show that ESD in higher education has expanded rapidly in the last decade, with growing emphasis on measurable learning outcomes and whole-institution transformation [

7,

8]. Despite clear evidence that ESD enhances student motivation, engagement, and problem-solving ability [

9,

10], implementation remains uneven across contexts due to limited resources, teacher training gaps, and a lack of valid indicators [

11]. By linking tolerance to sustainability competencies such as critical thinking, empathy, and civic responsibility, this study contributes to current debates on how higher education can operationalize Education for Sustainable Development in post-transition societies.

Several theoretical perspectives illuminate how tolerance is formed. Allport’s (1954) [

12] contact theory emphasizes the role of meaningful intergroup interaction, while Blalock’s (1967) [

13] threat theory explains how economic or cultural competition can produce exclusionary attitudes. Inglehart’s post-materialism thesis [

14] suggests that economic security supports openness, whereas precarity fosters retrenchment. Social Identity Theory [

15] highlights the influence of group affiliations in contexts where identity politics remain salient. These frameworks are particularly relevant for post-transition societies such as Montenegro.

Education is widely recognized as a central driver of tolerance and inclusion. Multicultural curricula, participatory pedagogies, and transformative learning approaches have been shown to enhance empathy, reduce prejudice, and develop sustainability competencies [

16,

17,

18]. However, the extent to which education fosters tolerance depends on institutional support and broader political conditions [

19]. Higher education thus plays a pivotal role in advancing Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) by equipping students with the critical thinking, intercultural understanding, and digital literacy needed to address societal challenges.

Digital media adds further complexity. Online platforms provide access to diverse perspectives but also amplify polarization through algorithmic filtering and echo chambers [

20,

21]. For youth in particular, digital literacy becomes an essential competency for navigating identity, civic participation, and sustainability challenges [

22]. Without such skills, opportunities for intergroup learning risk being overshadowed by ideological division.

Although Montenegro’s legal framework guarantees minority rights, the uneven implementation of policies and persistent socio-economic inequalities limit their impact [

23,

24]. Marginalized groups such as the Roma continue to face barriers to education, employment, and healthcare, highlighting the need for systemic interventions.

Against this backdrop, this study addresses three interrelated questions: (1) To what extent do young people in Montenegro express tolerant attitudes toward ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity? (2) How do these attitudes compare with broader European and regional trends? (3) Which individual-level and contextual factors—such as education, economic security, political engagement, and digital media use—influence tolerance? By situating these findings within the ESD framework, the study contributes to debates on how higher education can foster inclusive, sustainable societies in post-transition contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a mixed-methods research design that combined quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis. A structured online survey was conducted in Montenegro in 2021, targeting a sample of 712 individuals aged 15 to 30, with the aim of capturing a broad spectrum of youth perspectives on tolerance. The instrument consisted of 21 questions in multiple-choice and Likert-scale formats, addressing demographic characteristics, perceptions of diversity and discrimination, social interactions, political attitudes, and digital media use. Additionally, the survey included an open-ended question inviting participants to propose measures for improving societal tolerance.

Participants were recruited via social media platforms, student organizations, and youth networks to ensure diversity in educational background and socio-economic status. Stratification by gender, education level, and geographic region was applied to achieve sample balance and analytical representativeness. Based on the 2011 census, Montenegro’s youth population (15–30 years) was estimated at approximately 124,000. With 712 respondents, the sample size exceeds the minimum requirement for representativeness at a 95% confidence level with a ±5% margin of error. The questionnaire was pre-tested on a pilot group (n = 25) to assess clarity and relevance, with subsequent modifications made to improve item wording and structure.

Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, correlation analysis, logistic regression, and principal component analysis (PCA). A statistically significant association was observed between gender and societal tolerance (χ² = 61.82, p < 0.001), with a moderate effect size (Cramér’s V = 0.21). Logistic regression was applied to identify demographic predictors of tolerant attitudes, and PCA was used to extract latent dimensions from tolerance-related responses. The reliability of the instrument was confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86.

The open-ended responses were analyzed thematically to capture subjective insights and suggestions. This qualitative component allowed for triangulation and provided contextually rich reflections that complemented the quantitative findings.

All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. The study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards for social science research, ensuring anonymity, voluntariness, and data protection. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Donja Gorica (approval code: UDG-EC-2021-04, approved on 15 April 2021).

At the time of submission, we confirm that the data and results presented in this study are original and are being published for the first time. The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to privacy and ethical restrictions.

No generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools were used in the generation of text, data, or analysis in this study. Minor language edits were performed manually by the authors.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

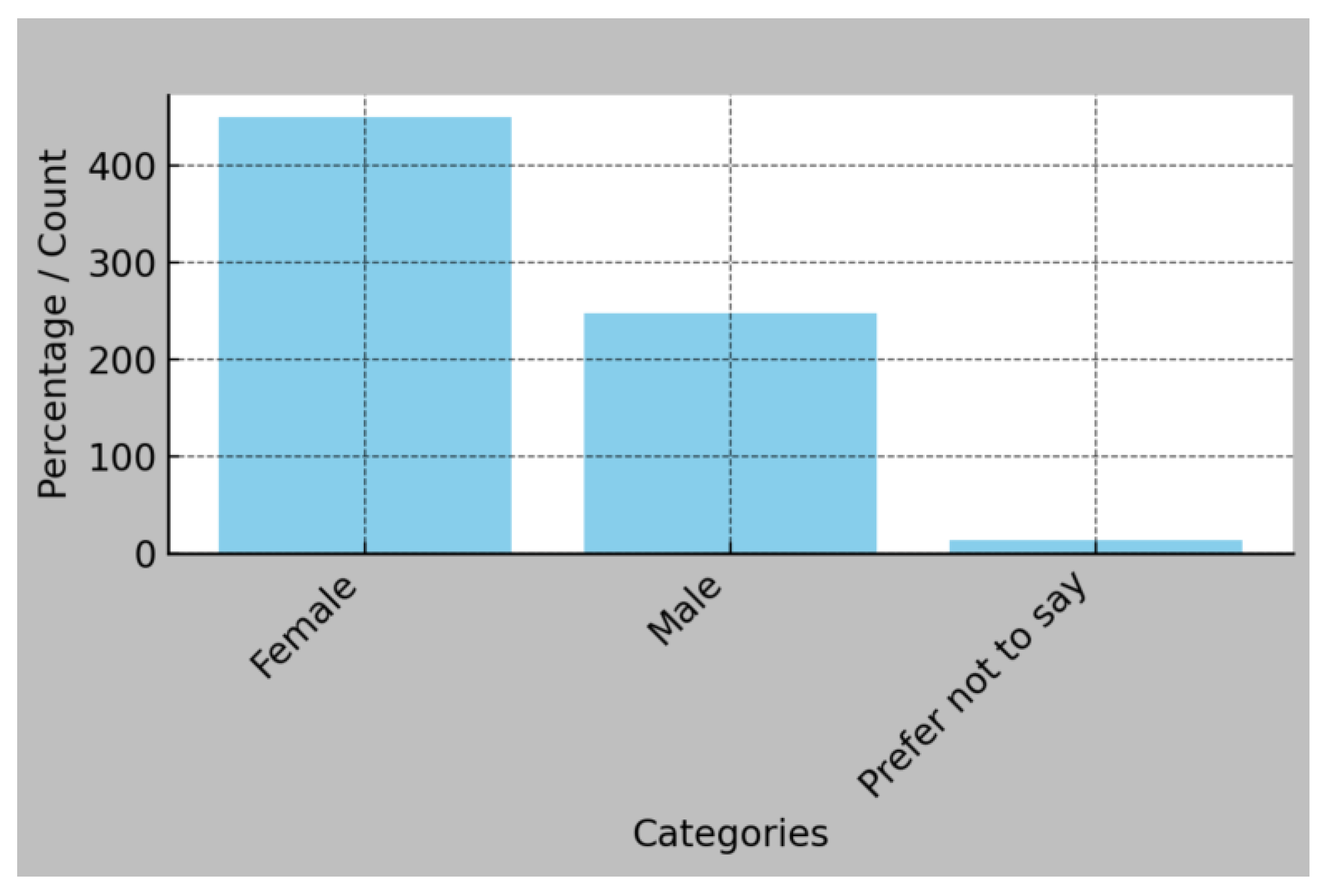

The final sample included 712 respondents aged 15 to 30, with balanced representation across gender, educational background, and geographic regions of Montenegro. Female respondents comprised 52.1% of the sample, while 47.3% were male and 0.6% identified outside the binary. Most participants were students or unemployed youth, reflecting the high youth unemployment rate in the country (

Figure 1).

Educational attainment varied, with the majority enrolled in or having completed secondary or higher education (

Figure 2). Participants were recruited through youth networks and platforms with national reach, ensuring heterogeneity in socio-economic and cultural exposure.

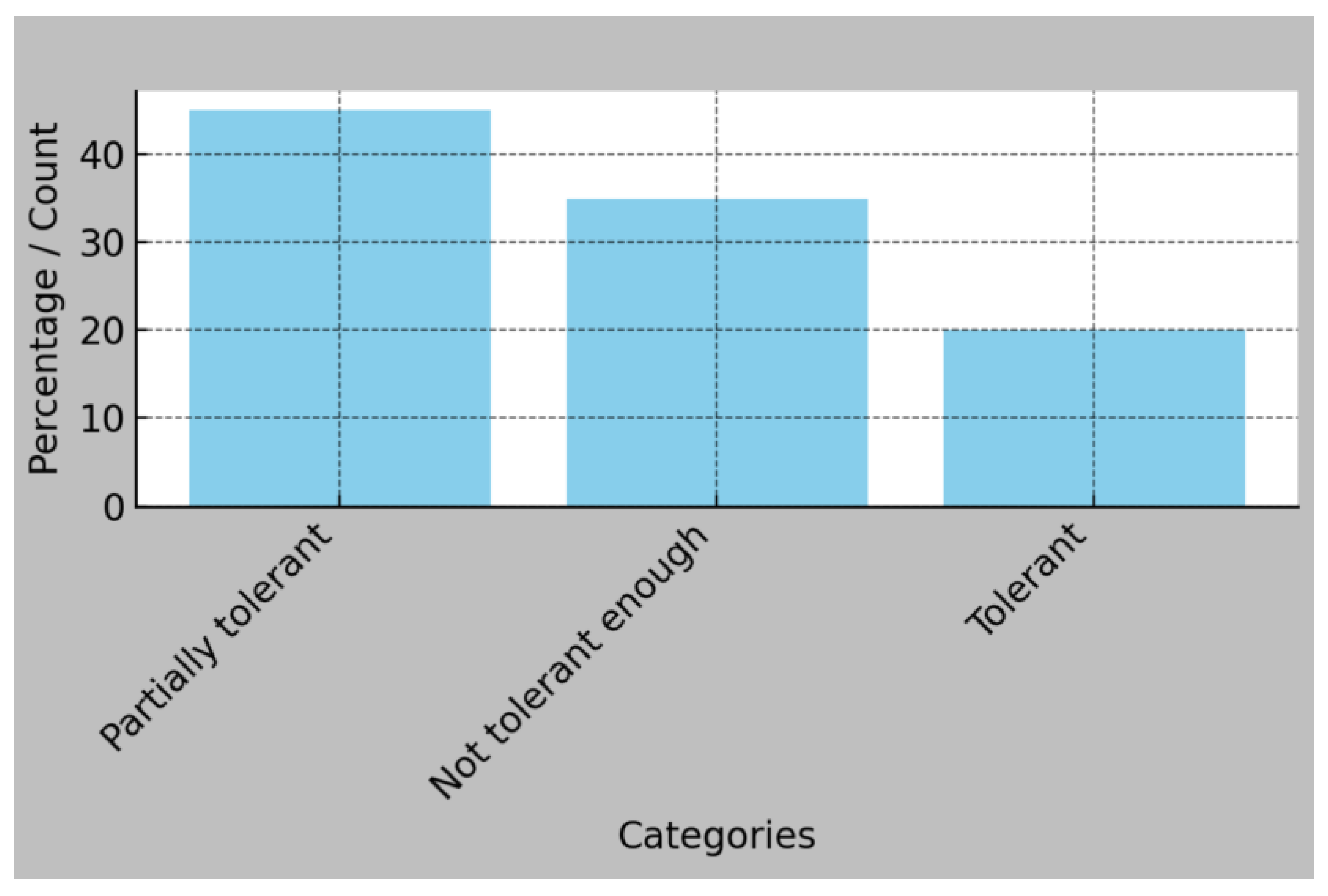

3.2. Awareness and Perceptions of Social Tolerance

Awareness of the International Day for Tolerance was relatively low; only 18% of respondents reported being familiar with it. However, 63% characterized Montenegrin society as moderately tolerant, while 14% considered it intolerant and 23% as tolerant (

Figure 3).

National identity was perceived as a key factor influencing intergroup attitudes: 48% of participants believed that nationalism negatively affects social cohesion.

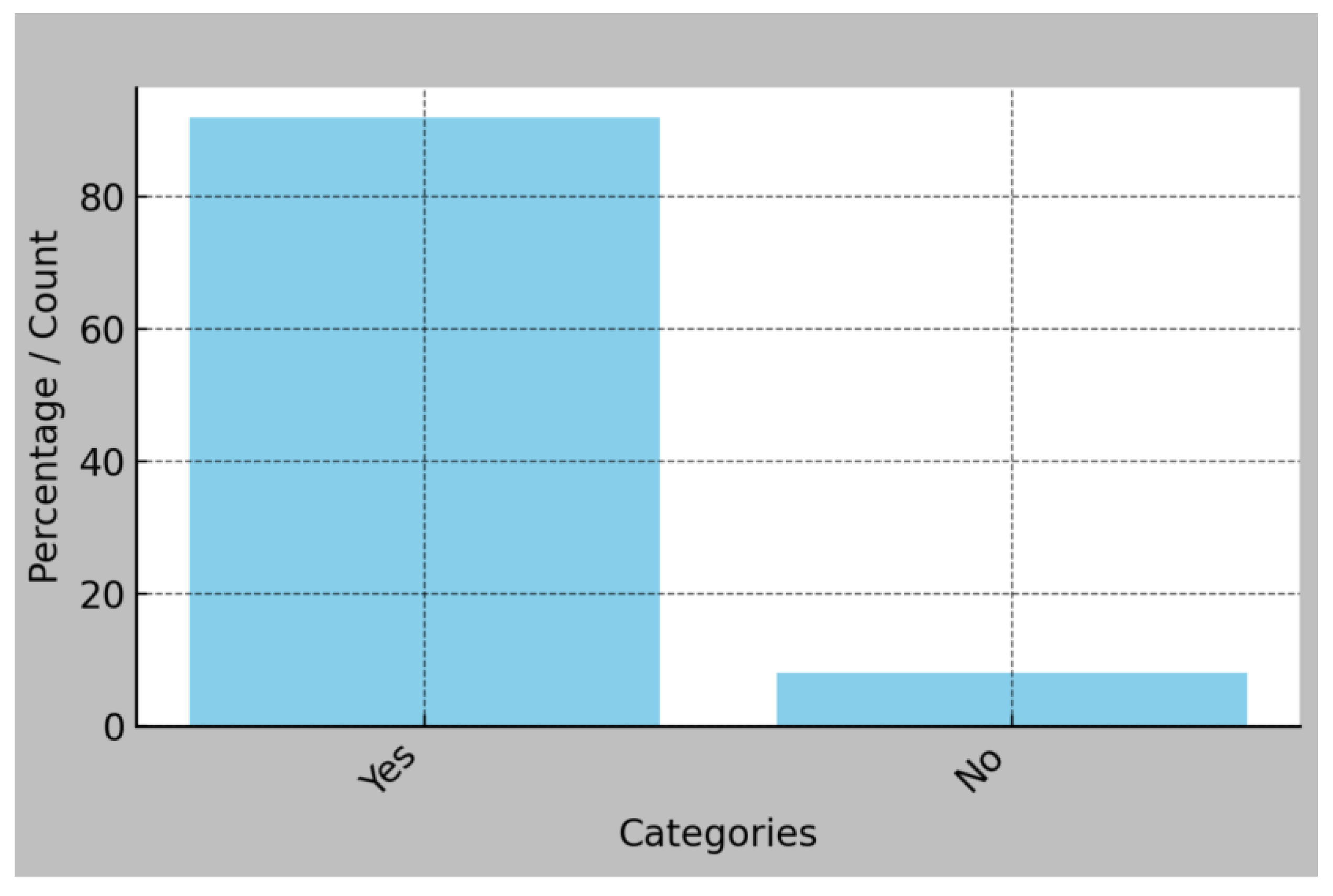

Social interactions across ethnic lines were common, with 68% of respondents reporting friendships with individuals of different national backgrounds (

Figure 4).

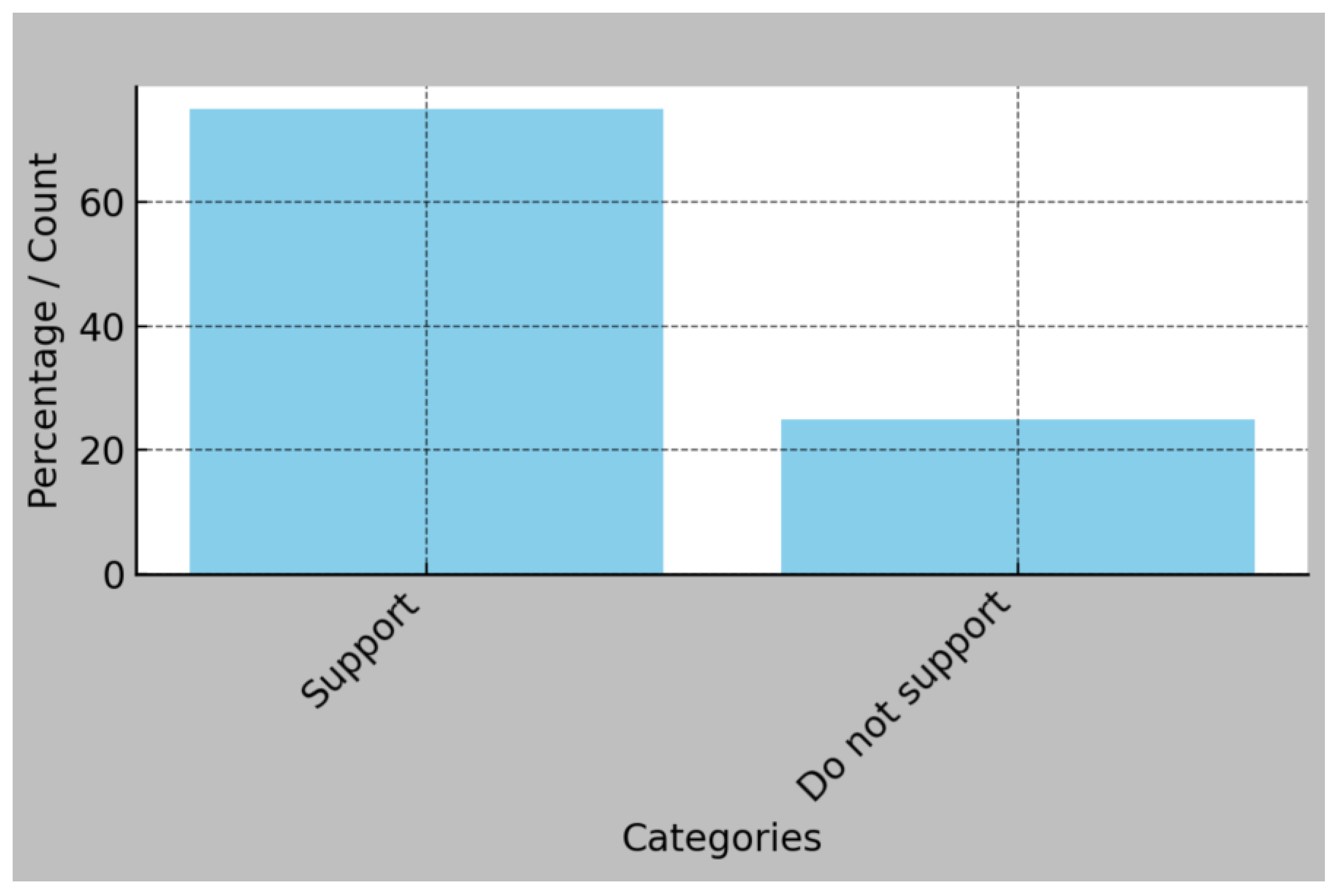

3.3. Cultural and Political Attitudes

A significant majority (72%) supported better cultural representation of minorities in public media and education (

Figure 5). However, only 38% believed that the political climate is becoming more tolerant, while 45% felt it remained the same and 17% perceived it as worsening.

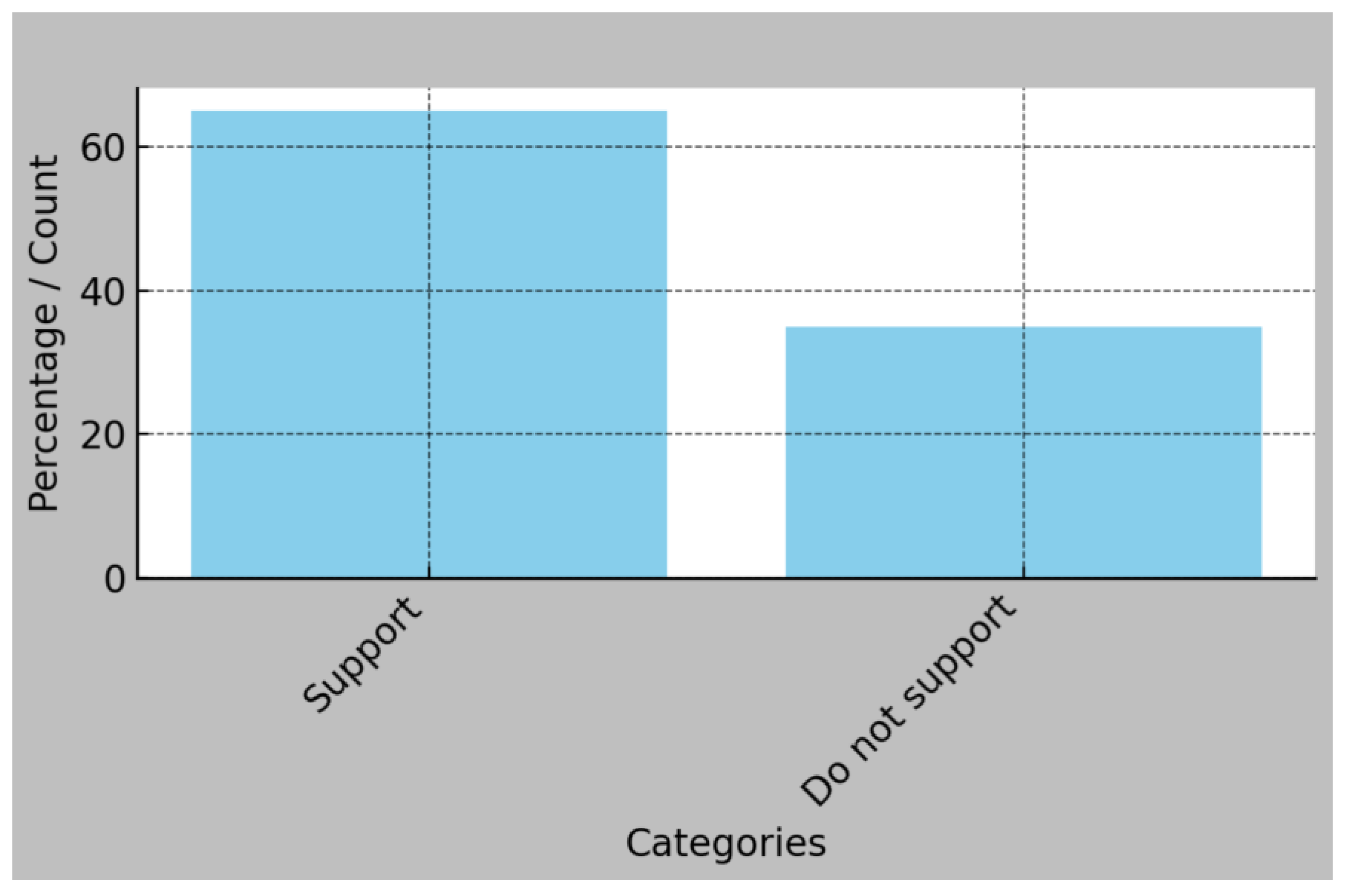

Regarding LGBTQ+ rights, 42% supported the legalization of same-sex partnerships, while 30% were opposed and 28% undecided (

Figure 6). On the question of transgender identity, 37% expressed openness to being friends or in a relationship with a transgender person, while 44% responded negatively.

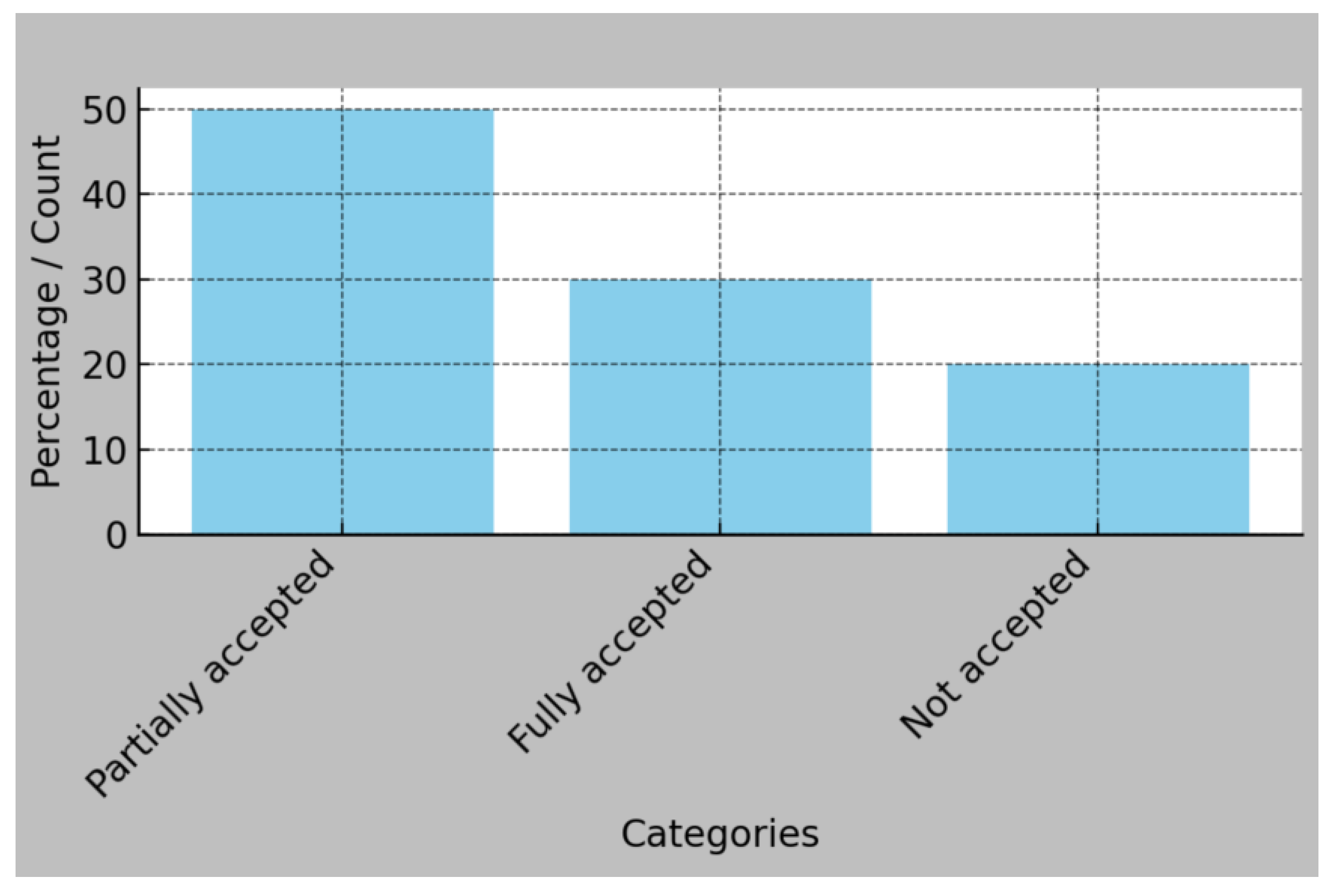

Racial and religious tolerance also showed mixed results: 55% agreed that Montenegro is accepting of racial diversity (

Figure 7), while 46% acknowledged the presence of religious discrimination in everyday life.

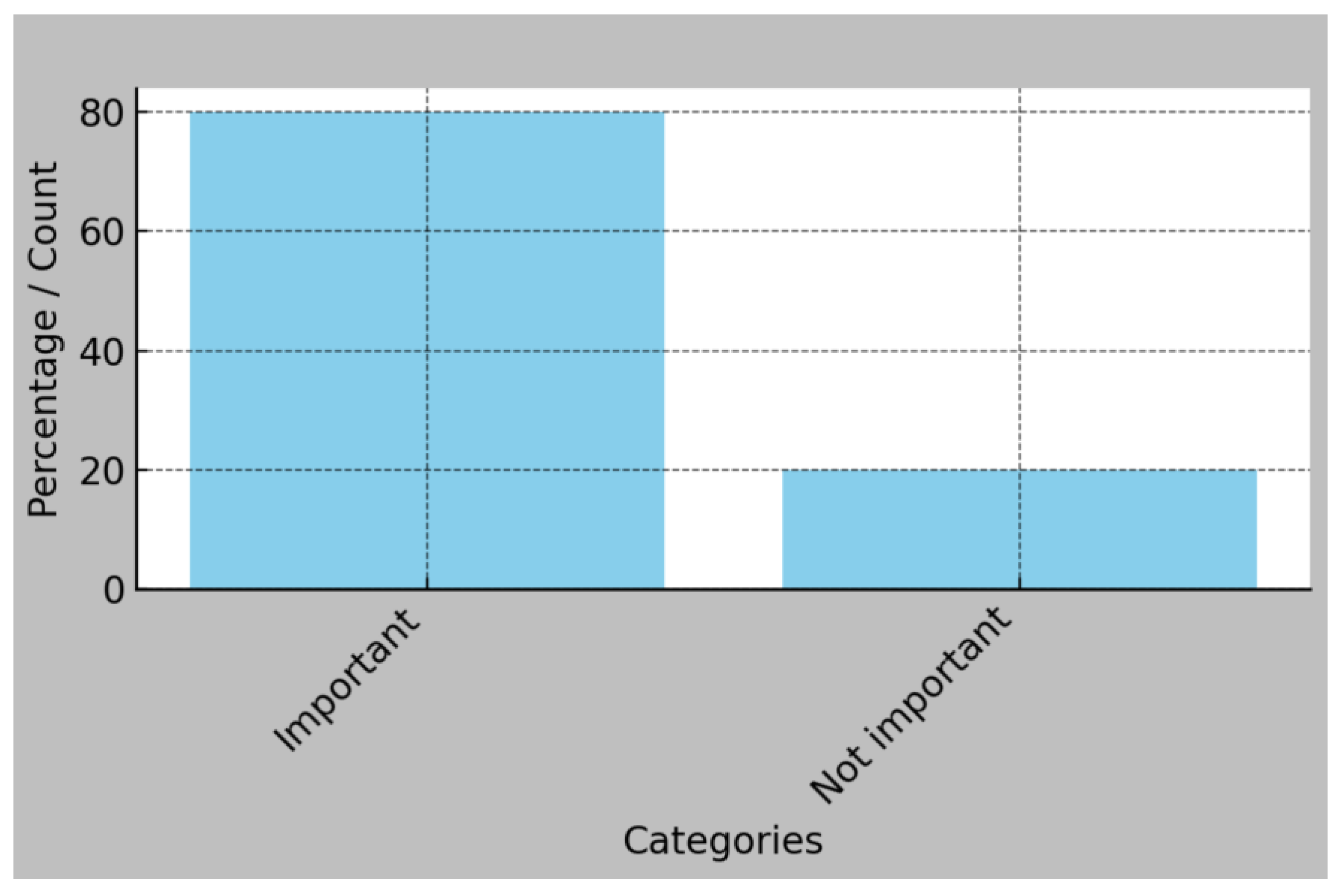

3.4. Media Influence and Digital Behavior

Social media was identified as both a source of awareness and a space for polarization. While 64% of respondents said digital platforms helped them learn about diversity and human rights, 58% also noted an increase in hateful content or online hostility toward minorities (

Figure 8). These findings reflect the dual role of digital environments in shaping attitudes.

3.5. Statistical Associations and Predictive Modelling

Statistical analysis revealed significant associations between demographic factors and tolerance-related attitudes. Gender was significantly associated with awareness of the International Day of Tolerance (χ² = 9.66, p = 0.008) and perceptions of societal tolerance (χ² = 61.82, p < 0.001), with a moderate effect size (Cramér’s V = 0.21). Education level was significantly linked to awareness of international observances (χ² = 11.01, p = 0.0117), but not to personal attitudes toward societal inclusivity or nationalism.

Further analyses using logistic regression and principal component analysis (PCA) confirmed the robustness of these associations, highlighting the importance of gender and education in shaping awareness of tolerance, though their influence on broader social attitudes appeared more limited.

3.6. Qualitative Insights

Open-ended responses provided additional nuance. Participants most frequently suggested the following interventions to improve tolerance:

Introducing intercultural education in schools;

Enhancing representation of minorities in media;

Organizing youth exchange programs and public forums.

Thematic coding revealed frustration with political polarization and a desire for more youth-inclusive policymaking. Many respondents expressed concern that tolerance is often promoted rhetorically but not consistently practiced in institutions or daily life.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings and Interpretations

This study provides the first empirical insight into the state of youth tolerance in Montenegro, revealing a landscape marked by both progressive openness and persisting societal cleavages, with direct implications for educational and societal sustainability. The results reflect broader European and Balkan trends but also underscore Montenegro’s unique socio-political context.

Education emerged as the most robust predictor of tolerance, echoing established research linking structured learning environments with inclusive worldviews [

12,

18]. Comparative findings from Croatia and Slovenia similarly highlight the positive role of civic and multicultural education [

25,

26]. In the Montenegrin context, however, the elective status of civic education limits systemic impact. The forthcoming Education Reform Strategy (2025–2035) [

27] therefore presents an opportunity to embed intercultural and experiential learning as mandatory elements of curricula. Such approaches align with Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), which emphasizes critical thinking, intercultural understanding, and empathy as sustainability competencies. As Veidemane (2022) [

28] argues, higher education institutions also need to operationalize these competencies through measurable indicators and internationally comparable benchmarks to ensure systematic progress toward sustainability goals.

Economic insecurity also emerged as a significant factor. As predicted by threat theory [

13], respondents facing greater economic precarity were more likely to express exclusionary views. With youth unemployment above 40%, these results highlight the need for policies that connect social equity, economic resilience, and sustainable development [

29].

Digital media demonstrated a dual role: while it increased awareness of human rights and diversity, it also amplified polarization. Similar findings across Europe [

21,

30] emphasize the urgency of developing national-level digital literacy strategies. For higher education institutions, integrating digital literacy into curricula represents a practical avenue for advancing both social inclusion and sustainability. In line with this, Muhonen, Timonen, and Väänänen (2024) [

31] show how contextualizing ESD competences through research, development, and innovation (RDI) enhances the relevance of higher education curricula and strengthens stakeholder-informed sustainability transformations.

Historical narratives and unresolved identity politics also shape intergroup attitudes. Montenegro’s contested national identity and the legacy of Yugoslavia influence how young people define belonging [

32,

33]. Lessons from post-conflict education reforms in Rwanda and Bosnia suggest that reconciliation-oriented curricula can mitigate such divisions [

34,

35].

Finally, the EU accession process holds transformative potential. Croatia’s experience indicates that alignment with EU standards on education, minority rights, and anti-discrimination can foster tolerance [

25]. For Montenegro, alignment with these frameworks will be essential for sustaining progress toward inclusive and sustainable societies.

4.2. Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. First, the use of self-reported data on sensitive issues such as nationalism and minority rights may have introduced social desirability bias. Second, the cross-sectional design provides only a snapshot and does not capture attitudinal changes over time. Longitudinal research is therefore needed to examine how youth tolerance evolves in response to political, social, and educational reforms.

Although open-ended responses enriched the quantitative results, the absence of in-depth qualitative interviews limited insights into the underlying motivations behind certain attitudes. Furthermore, while digital media use was analyzed, future studies should examine algorithmic exposure, misinformation, and digital activism in greater depth. Future research should also investigate how ESD-oriented curricula and higher education reforms shape long-term tolerance and sustainability competencies among students.

4.3. Comparative Perspectives: Montenegro and the Balkans

Montenegro’s youth attitudes toward tolerance are situated between more progressive contexts such as Slovenia and more polarized ones such as Romania. While openness toward ethnic and gender diversity is increasing, entrenched biases remain, particularly regarding LGBTQ+ and Roma communities—patterns consistent across the region [

36].

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, ethnic segregation in schools perpetuates exclusive narratives [

37], a challenge Montenegro also faces through politicized history curricula. In Serbia, nationalist rhetoric and algorithm-driven polarization play a central role in shaping youth perspectives [

38], a dynamic mirrored in Montenegro’s digital landscape.

Romania’s high levels of prejudice toward Roma and LGBTQ+ individuals [

39] contrast with more moderate, though still divided, views in Montenegro. These comparisons suggest that while economic insecurity is a shared regional challenge, educational systems and civic engagement policies remain critical differentiators. Within the sustainability agenda, higher education emerges as a decisive lever for shaping inclusive attitudes and fulfilling SDG 4.7 on global citizenship and sustainable development.

4.4. Challenges for Future Tolerance

Several emerging dynamics may hinder future progress. Digital polarization, youth emigration, demographic change, and climate-induced migration all pose risks for social cohesion.

With 80% of Montenegrin youth relying on social media as a primary news source, algorithmic echo chambers threaten to entrench ideological divisions [

21]. Youth emigration further exacerbates brain drain, potentially weakening the more progressive segment of society and limiting intergroup contact at home [

40]. Demographic aging and declining birth rates may strengthen conservative electoral trends [

41], while climate-related migration could test societal tolerance in new ways.

Addressing these challenges requires investments in:

Nationwide digital literacy programs rooted in ESD principles;

Economic strategies that reduce youth precarity and promote equity;

Inclusive educational policies that mainstream intercultural learning across curricula;

Community-based initiatives that foster intergroup collaboration and youth participation.

4.5. Implications for Higher Education and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD)

The findings of this study align with the current global discourse on Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in higher education. Recent MDPI reviews emphasize that universities must go beyond isolated courses and adopt whole-institution approaches that integrate sustainability values into teaching, research, and governance [

5,

7,

10]. Tolerance, as a social and civic competency, can be understood within the broader ESD competency framework, which includes systems thinking, critical thinking, collaboration, and empathy [

6,

9]. Embedding these competencies into curricula through experiential and participatory pedagogies has been shown to increase students’ motivation and ability to address complex societal challenges [

10,

11]. Therefore, higher education institutions in Montenegro could strengthen their contribution to SDG 4.7 by systematically aligning curricular reforms, digital literacy initiatives, and civic education with ESD principles.

4.6. Recommendations

4.6.1. Policy Recommendations

A coherent national strategy is needed to integrate education, digital literacy, and anti-discrimination policies within the sustainability framework. Embedding ESD principles into curricula and teacher education programs is essential to build the competencies outlined in SDG 4.7. Legal frameworks must be reinforced to ensure minority rights and equitable access to education and employment.

Public investment should support intercultural initiatives at community level, while participatory governance mechanisms—such as youth councils and forums—can enhance ownership and relevance of inclusion efforts.

4.6.2. Practical Recommendations

Practical measures for advancing educational and societal sustainability can be implemented through several complementary approaches. The integration of inclusion, diversity, and equity (IDE) into national curricula, delivered through interactive and experiential learning formats, can strengthen key competencies for sustainable development. Equally important are digital literacy campaigns in which different sectors collaborate to provide accessible training in critical media use, with a focus on sustainability values. Social-emotional learning (SEL) should be established as a core objective of both formal and informal education, promoting empathy, self-regulation, and conflict resolution skills. In addition, youth engagement must be fostered by creating participatory spaces such as councils, mentorship programs, and intercultural exchanges that build civic collaboration and contribute to sustainable social cohesion. Finally, all of these initiatives should be accompanied by continuous evaluation and feedback mechanisms to ensure they remain effective, scalable, and responsive to evolving societal needs.

5. Conclusions

This study offers the first empirical assessment of youth tolerance in Montenegro, revealing a society at a crossroads between progressive openness and persisting social divides. Younger generations increasingly embrace diversity across ethnic, religious, and gender lines, yet deep-rooted divisions linked to economic insecurity, historical narratives, and digital polarization remain influential.

Education emerged as the most consistent driver of tolerant attitudes, underscoring the urgent need for systemic reforms that align civic education with Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). Integrating experiential learning, media literacy, and intercultural dialogue into higher education and national curricula can foster critical thinking, empathy, and sustainability competencies among youth. In contrast, economic marginalization reinforces exclusionary attitudes, highlighting the necessity of policies that address youth unemployment and inequality as both economic and social imperatives.

The role of digital media presents a dual challenge: while enabling exposure to diverse perspectives, it also risks reinforcing ideological divides. Strengthening digital literacy and promoting responsible digital citizenship are essential for mitigating polarization and advancing sustainable societies.

Historical narratives continue to shape identity politics, but evidence from post-conflict contexts demonstrates that reconciliation-oriented education can reduce intergroup prejudice—an approach Montenegro could meaningfully adapt. Comparative analysis places Montenegrin youth between more progressive and more polarized regional counterparts, suggesting both opportunities and vulnerabilities.

In the context of higher education, these results reinforce recent ESD research that calls for competence-based, transformative learning models. Embedding tolerance, empathy, and intercultural understanding as measurable learning outcomes can enhance the sustainability competencies of university graduates. Universities that link civic engagement and digital literacy with Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) not only contribute to social cohesion but also fulfill their institutional responsibility within the sustainability transition.

Promoting tolerance therefore requires a comprehensive, cross-sectoral strategy that integrates educational reform, youth-centered economic policies, digital citizenship initiatives, and community-based intercultural programs. Crucially, youth must be recognized not only as beneficiaries but also as co-creators of these interventions.

Montenegro’s youth represent a promising foundation for building inclusive and sustainable societies. Realizing this potential will demand sustained investment in education, empowerment, and meaningful intergroup engagement, in line with the global sustainability agenda and the competencies outlined in SDG 4.7.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.P. and I.K.; methodology, I.K., and I.P., and A.O.; software, I.P.; validation, I.K., A.G., and A.O.; formal analysis, I.K.; investigation, A.O., M.M., and A.G.; resources, I.K. and M.M.; data curation, I.K., A.O. and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, I.P.; writing—review and editing, I.P., A.G., and I.K.; visualization, A.O.; supervision, I.P.; project administration, I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Donja Gorica (approval code: UDG-EC-2021-04, approved on 15 April 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and in line with ethical research guidelines.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the student organizations and youth networks in Montenegro that supported the dissemination of the survey. We also extend our appreciation to all participants who voluntarily contributed their time and perspectives. Special thanks go to the University of Donja Gorica (UDG) for institutional support throughout the research process. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4) for assistance in language editing and formatting. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NGO |

Non-Governmental Organization |

| EU |

European Union |

| ICT |

Information and Communication Technology |

| SEE |

South-East Europe |

| TVET |

Technical and Vocational Education and Training |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| MNE |

Montenegro |

| IDI |

In-Depth Interview |

| QOL |

Quality of Life |

| GDP |

Gross Domestic Product |

| OECD |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| ESD |

Education for Sustainable Development |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

References

- Janmaat, J.G.; Keating, A. Are today’s youth more tolerant? Trends in tolerance among young people in Britain. Ethnicities 2019, 19, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, S.B.; Özdemir, M.; Boersma, K. How does adolescents’ openness to diversity change over time? The role of majority-minority friendship, friends’ views, and classroom social context. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, E.; Schönwälder, K.; Petermann, S.; Vertovec, S. Diversity assent: Conceptualisation and an empirical application. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2023, pp. 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Yuenyong, T. (2024). Management Strategies for Higher Education Institutions Based on the Principles of ESD in the Lower Northern Region. Journal of Ecohumanism, 3(7), 712–722.

- Price, E.; White, R.M. (2025). Education for Sustainable Development. Routledge.

- Arruti, C.I.G.; Enriquez, A.J.M. (2022). Responsibility in Institutions of Higher Education: Education for Sustainable Development. Am. J. Appl. Sci. Res., 8(2), 25.

- Khan, S.; Khan, A.M. (2018). A Phenomenological Study of ESD in Higher Education of Pakistan. Pak. J. Educ., 35(2).

- Ujeyo, M.S.; Najjuma, R. (2022). Sustainable Development in the Context of Higher Education. In IGI Global Handbook.

- Ujeyo, M.S.S. (2019). Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in Higher Education. In IGI Global Handbook, 117–133.

- Jurado, D.M.B. et al. (2024). Advancing University Education: Exploring the Benefits of Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 16(17), 7847.

- Sebire, R.H.; Isabeles-Flores, S. (2023). Sustainable Development in Higher Education Practices. Revista Lengua y Cultura.

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1954.

- Blalock, H.M. Toward a Theory of Minority-Group Relations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1967.

- Inglehart, R. Post-materialism in an environment of insecurity. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1981, 75, 880–900. [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sahal, M.; Musadad, A.A.; Akhyar, M. Tolerance in multicultural education: A theoretical concept. Int. J. Multicult. Multireligious Underst. 2018, 5, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anugrah, D.S.; Supriadi, U.; Anwar, S. Multicultural education: Literature review of multicultural-based teacher education curriculum reform. Eurasia Proc. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2024, 39, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osin, R.; Roganova, A.E.; Medvedeva, I.A. Research of ethnic tolerance in the youth environment. Psikhologiia i Psikhotehnika 2022, 4, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariser, E. The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You; Penguin: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Metzler, H.; Garcia, D. Social drivers and algorithmic mechanisms on digital media. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2023, Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.; Karim, A.M.; Mondol, E.P.; Helal, M.S.A. Influence of digital education to uplift the global literacy rate in the age of digital civilization. Int. J. Acad. Res. Account. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2024, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Džankić, J. Montenegro’s minorities in the tangles of citizenship, participation, and access to rights. J. Ethnopolit. Minor. Issues Eur. 2012, 11, 40–59. Available online: https://www.pure.ed.ac.uk/ws/files/11769314/Dzankic_J_Montenegro_s_Minorities_in_the_Tangles_of_Citizenship_Participation_and_Access_to_Rights.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Vukadinović, S. The education situation of Roma in Montenegro. In Education in South-East Europe: From Reforms to Practices; Mihailova, A., Ed.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2023; pp. 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banovac, B.; Katunarić, V.; Mrakovčić, M. From war to tolerance? Bottom-up and top-down approaches to (re)building interethnic ties in the areas of the former Yugoslavia. Soc. Sci. Croat. 2014, 35, 455–483. https://repository.pravri.uniri.hr/islandora/object/pravri:340/datastream/FILE0/download.

- Isac, M.M.; Brese, F.; Diazgranados, S.; Higdon, J.; Maslowski, R.; Sandoval-Hernández, A.; Schulz, W.; van der Werf, G. Tolerance through education: Mapping the determinants of young people’s attitudes towards equal rights for immigrants and ethnic/racial minorities in Europe. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education, Science and Innovation. Strategy for Education Reform 2025–2035; Government of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2025; Available online: https://www.gov.me/dokumenta/73f999b6-b879-4868-a72d-e670ce78f77f (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Veidemane, A. Education for sustainable development in higher education rankings: Challenges and opportunities for developing internationally comparable indicators. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MONSTAT. Statistical Yearbook of Montenegro 2021; Statistical Office of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2021; Available online: https://monstat.org/uploads/files/publikacije/godisnjak%202021/STATISTI%C4%8CKI%20GODISNJAK%202021.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Törnberg, P. How digital media drive affective polarization through partisan sorting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2207159119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhonen, T.; Timonen, L.; Väänänen, K. Fostering education for sustainable development in higher education: A case study on sustainability competences in research, development and innovation (RDI). Sustainability 2024, 16, 11134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleshkina, E.; Pomiguev, I. Montenegro in search of national and state identity. Polit. Sci. Issues 2021, 15, 5–18. Available online: https://press.psu.ru/index.php/polit/article/download/4495/3351 (accessed on 19 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, S. Literature, social poetics, and identity construction in Montenegro. Int. J. Politics Cult. Soc. 2003, 17, 131–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staub, E. The roots of helping, heroic rescue and resistance to and the prevention of mass violence: Active bystandership in extreme times and in building peaceful societies. In Handbook of Prosocial Behavior; Schroeder, D., Graziano, W., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; Chapter 33; Available online: http://people.umass.edu/estaub/Prosocial%20Handbook%20Chapter%2033.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). Youth in Bosnia and Herzegovina: A Study on National Identity and Belonging; OSCE Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Special Eurobarometer 503: Discrimination in the European Union; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). Ethnic Divisions in Education and Their Impact on Social Cohesion in Bosnia and Herzegovina; OSCE: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckel, F.; Ceka, B. Political tolerance in Europe: The role of conspiratorial thinking and cosmopolitanism. Eur. J. Political Res. 2022, 62, 699–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Jaidka, K.; Chen, V.H.H.; Cai, M.; Chen, A.; Emes, C.S.; Yu, V.; Chib, A. Social media and anti-immigrant prejudice: A multi-method analysis of the role of social media use, threat perceptions, and cognitive ability. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1280366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES). Youth Study Southeast Europe 2024: Montenegro; FES: Berlin, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://www.fes.de (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- MONSTAT. Statistical Yearbook of Montenegro 2023; Statistical Office of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2023; Available online: https://www.monstat.org/uploads/files/publikacije/GODISNJAK%202023.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).