1. Introduction

Education systems in the Gulf region are undergoing profound transformation amid rising demands for digital innovation, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability. Yet, despite growing investments in school infrastructure and international curricula, few models in the region offer an integrated approach that combines academic rigor with psychosocial support, technological fluency, and cultural grounding. This gap is particularly evident in post-pandemic contexts, where students’ emotional and developmental needs remain under-addressed (UNICEF, 2021).

In response, this paper introduces the Smart and Inclusive School Complex in Halban, a national pilot model conceptualized for one of Oman’s emerging “green” urban zones. Situated in Halban—an eco-oriented neighborhood under active development—the proposed school serves as a blueprint for holistic, future-ready education in the Arab Gulf. The model integrates inclusive pedagogy, in-house psychosocial services, climate-resilient design, and Islamic ethical values rooted in Omani heritage.

International organizations have increasingly emphasized the need for schools to serve as catalysts for environmental awareness, social equity, and community resilience. UNESCO’s Greening Education Partnership (2022) advocates for transforming educational institutions into hubs for climate action and inclusive values. Similarly, the World Bank (Velez Bustillo & Patrinos, 2023) outlines critical challenges facing low- and middle-income countries, ranging from learning poverty to weak teacher capacity and underdeveloped early childhood systems. These frameworks call for educational environments that integrate psychosocial support, evidence-based design, and cultural sensitivity. The Halban model is directly informed by these priorities, offering a localized, scalable solution grounded in international evidence yet tailored to the Gulf context.

Against this backdrop, this paper invites a critical question: What would it take to design a school that is not only academically effective, but also emotionally nurturing, environmentally sustainable, technologically advanced, and culturally rooted—all within the context of a rapidly developing Gulf city?

1.1. Strategic Location and Urban Relevance

Halban is one of Oman’s emerging urban zones located approximately 47 kilometers (32 minutes) from central Muscat. It is home to a newly developed residential area comprising 1,442 housing units, established through a public–private partnership under the supervision of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning. Identified as a strategic growth corridor in Oman Vision 2040, the neighborhood is witnessing accelerated expansion but remains underserved in terms of integrated, inclusive educational infrastructure.

The Smart and Inclusive School Complex model is proposed to be constructed on a 40,000 square meter plot, offering education from pre-primary through the basic education stages (ages 3 to 18) for both boys and girls. Approximately 40% of the land will be allocated for buildings, including classrooms, administrative blocks, and boarding units—while 60% will be reserved for green spaces, outdoor learning areas, and recreational facilities, in line with environmental and developmental design principles.

The site is strategically located near several major academic and innovation hubs, including Sultan Qaboos University, the German University of Technology in Oman (GUtech), and the Knowledge Oasis Muscat (KOM)—a national technology and research park. These proximities offer unique opportunities for partnership, field training, and educational continuity from early childhood through to higher education. By embedding the school within a rapidly developing, knowledge-oriented urban ecosystem, the project strengthens social cohesion, supports demographic growth, and contributes to Oman’s broader agenda for sustainable urban and educational development.

1.2. The Rationale and Innovation Behind the Model

The Smart and Inclusive School Complex in Halban was conceived in response to multiple converging needs in the educational landscape of Oman and the wider Gulf region. While educational initiatives emphasize academic achievement and infrastructure expansion, few have holistically addressed the psychosocial, environmental, cultural, and technological dimensions of child development. This section presents the empirical and contextual foundations of the model and explains its distinctive contribution to rethinking school design in the 21st century.

1.3. Psychosocial and Technological Imperatives in Post-Pandemic Education

Global education systems increasingly recognize that academic instruction alone is insufficient to support students’ overall development. Emotional support and psychological resilience are now seen as integral to effective learning environments, especially in the aftermath of COVID-19. The pandemic has amplified longstanding deficiencies in education systems worldwide, particularly in addressing the emotional and psychological well-being of students.

According to UNICEF (2021), many children continue to experience anxiety, fear, and developmental regression due to prolonged school closures, social isolation, and disruption of daily routines. These effects are especially pronounced in Gulf countries like Oman, where school-based psychosocial support remains underdeveloped and culturally stigmatized (Author, year).

Simultaneously, the rapid digitization of childhood requires educational systems in the region to move beyond traditional, teacher-centered instruction. The Education 5.0 paradigm advocates for interactive, technology-enhanced learning, leveraging tools such as artificial intelligence, gamification, and virtual reality to personalize the learning experience and enhance 21st-century skills (Ahmad et al., 2023).

In this context, there is a pressing need for integrated school models in Oman and the wider Gulf that are not only academically rigorous but also emotionally responsive and digitally fluent. The Halban initiative directly responds to this multidimensional gap by embedding psychosocial care and smart learning infrastructure into the foundation of its design.

1.4. Contextualizing Private and Bilingual Education in Oman

In addition to global imperatives, the national landscape in Oman reflects both significant progress and persistent gaps in private education. Between 2017 and 2022, the number of private schools in the country grew from 578 to approximately 677, with a compound annual growth rate of 3.2% (Alpen Capital, 2023). Yet, private institutions still account for only 36% of all schools, well below the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) average, highlighting untapped potential for sectoral expansion.

To bridge capacity shortfalls and diversify educational options, the Ministry of Education launched a public-private partnership (PPP) initiative in 2022 to develop 76 new schools, including 42 co-financed projects targeting nearly 80,000 students. While this initiative signals promising policy momentum, the qualitative nature of private education remains a concern. Earlier reforms in Oman’s post-basic education system also faced similar challenges in bridging policy with equitable and inclusive outcomes (Issan & Gomaa, 2010). Most private schools in Oman rely on international or bilingual curricula, such as British, American, Indian (CBSE), or IB systems, focusing predominantly on academic performance and global certification rather than holistic development.

The Halban model offers an alternative paradigm—one that combines academic excellence with psychosocial care, inclusive design, environmental ethics, and culturally grounded values. It addresses the current imbalance by proposing a locally relevant ecosystem for sustainable, inclusive, and socially anchored education. This vision aligns with Oman Vision 2040, which emphasizes educational innovation, equity, and effective public-private partnerships as pillars of national development (Oman Vision 2040, 2020).

1.5. Theoretical and Contextual Foundations

The design of the Halban Smart School Complex is anchored in a multidimensional theoretical framework that combines internationally recognized pedagogical models with a regionally developed concept of social welfare governance. This dual foundation ensures that the school operates in alignment with global best practices and in direct response to the sociocultural and institutional realities of Oman and the broader Gulf region (Issan & Gomaa, 2010).

At the international level, the project draws on Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, which highlights the dynamic interplay between children and their surrounding environments—from family and school to society at large. It also reflects the principles of Social Justice Theory (Fraser, 1997; Rawls, 1971), particularly in its emphasis on equity, cultural inclusion, and rights-based accessibility. In alignment with UNESCO’s Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) agenda, the model advocates for holistic learning environments that integrate environmental consciousness, cultural identity, and community empowerment.

Complementing these global perspectives is the Eight Pillars of Social Welfare model—a Gulf-based governance framework developed by the lead researcher. This model outlines eight interlocking dimensions essential to building sustainable and accountable public systems: governance, fair legislation, multi-sectoral partnership, genuine empowerment, effective digitalization, continuous evaluation, supportive culture, and political will.

These dimensions serve as operational principles embedded in the school’s infrastructure, curriculum design, staffing policies, and evaluation mechanisms. For example, the emphasis on psychosocial resilience from Bronfenbrenner’s framework is operationalized through the inclusion of full-time counselors and sensory therapy rooms, while the pillar of “supportive culture” translates into culturally adapted curricula and spaces for ethical and spiritual reflection.

By fusing global insights with a contextually grounded framework, the Halban model offers a culturally responsive and operationally coherent approach to 21st-century education—bridging innovation, sustainability, and social justice in a tangible institutional form.

1.6. Empirical Evidence from the Gulf Region

Empirical research across the Gulf region reinforces the rationale behind the Halban School Complex by highlighting persistent gaps and promising initiatives in sustainable education. In Oman, environmental clubs in public schools have significantly increased student awareness of sustainability issues through experiential learning and green space engagement (International Journal of Environmental & Science Education, 2020).

In the UAE, an evaluation of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) integration in private schools reported notable improvements in student engagement and environmental responsibility (Sustainability, 2021). Similarly, a national survey of teachers in Saudi Arabia found strong support for ESD principles but emphasized the need for institutional reform and targeted professional development to move from policy to practice (Educational Research Quarterly, 2019).

These regional insights reveal a shared demand for more comprehensive educational frameworks that not only promote environmental awareness but also integrate emotional well-being, cultural identity, and inclusive pedagogy. The Halban model directly addresses this regional gap by operationalizing these dimensions through its curriculum, staff structure, physical environment, and governance philosophy.

1.7. Conceptual Uniqueness of the Halban School Model

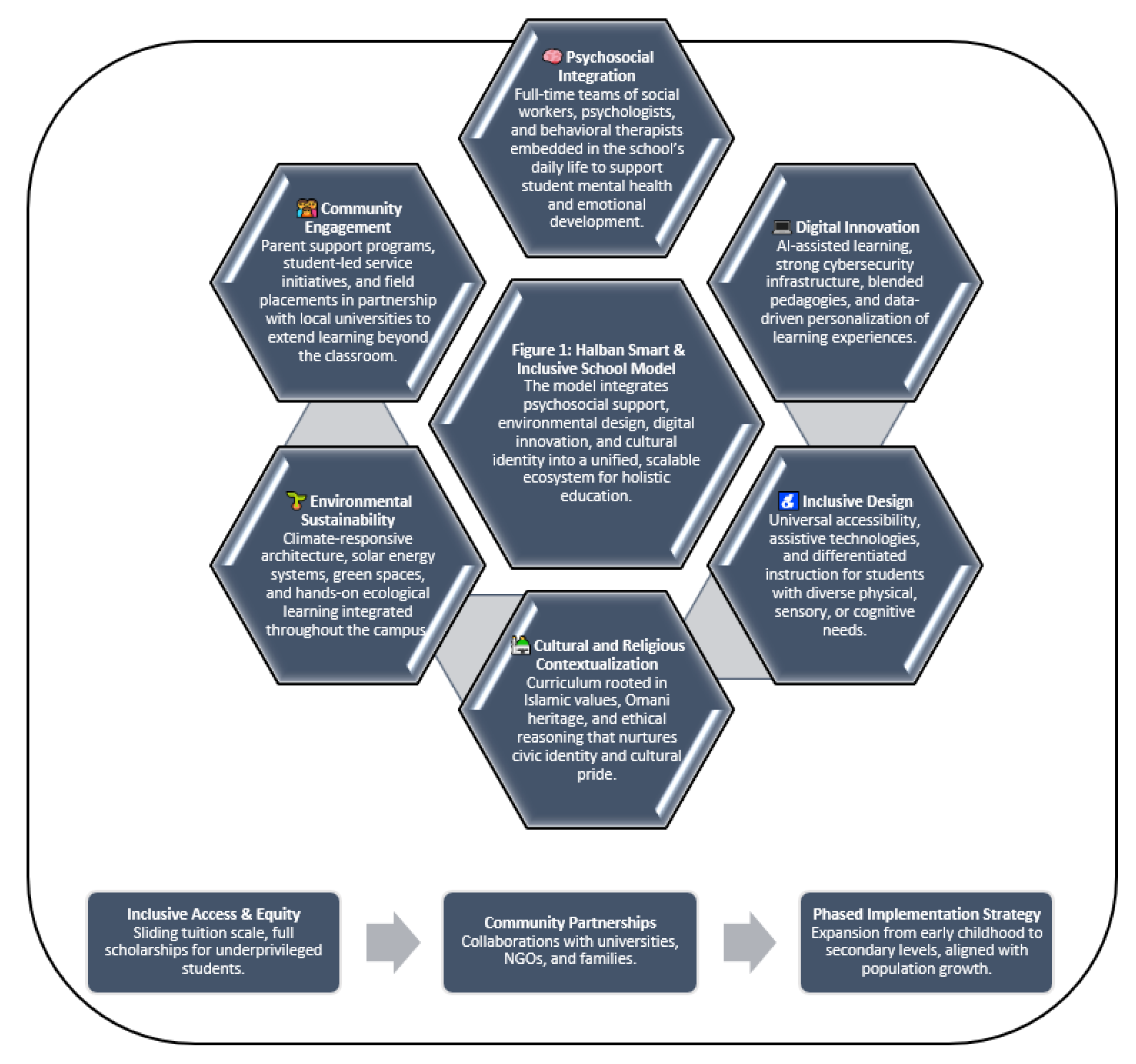

Anchored in social work principles and aligned with Oman Vision 2040, the Halban Smart and Inclusive School Complex introduces an innovative institutional model that bridges multiple domains of child development—academic, emotional, environmental, and cultural. Unlike most schools in the region that treat these domains separately or superficially, the Halban model fuses them into a unified, operational framework. Its distinctiveness lies not only in the presence of these elements but in their intentional integration within a single school environment. The model is built upon six core pillars:

- (1)

Psychosocial Integration – Full-time teams of social workers, psychologists, and behavioral therapists are embedded within the daily life of the school.

- (2)

Digital Innovation – AI-assisted learning, robust cybersecurity infrastructure, blended pedagogies, and real-time data systems that support personalized instruction and adaptive learning environments.

- (3)

Inclusive Design – Universal accessibility, assistive technologies, and differentiated instruction for students with diverse physical and cognitive needs (Frontiers in Psychology, 2022).

- (4)

Cultural and Religious Contextualization – Curricular emphasis on Islamic values, national identity, and ethical reasoning grounded in Omani heritage.

- (5)

Environmental Sustainability – Climate-responsive infrastructure, solar energy systems, green spaces, and hands-on ecological education.

- (6)

Community Engagement – Structured parent support programs, university-based field placements, and student-led service initiatives that extend learning beyond the classroom.

These six dimensions are treated as add-ons, and as interdependent components of a holistic system. As such, the Halban school is conceptualized as a site of academic instruction and as a living micro-community that nurtures intellectual growth, emotional well-being, civic identity, and social inclusion. This integrated vision offers a transferable model for future-ready education in the Gulf and beyond. The following

Figure 1 illustrates the six foundational pillars and enabling strategies that constitute the Halban Smart and Inclusive School model.

1.8. Social, Economic, and Environmental Relevance of the Project

In the 21st century, the effectiveness of educational initiatives is increasingly measured by their contribution to broader goals of social equity, economic resilience, and environmental sustainability. The Halban Smart and Inclusive School Complex was intentionally designed to respond to these intertwined imperatives—not merely as a place of instruction, but as an engine for community transformation. Its design recognizes that schools in the Gulf must evolve into institutions that serve both individual development and collective progress.

Aligned with Oman Vision 2040 and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, the Halban model embeds these three pillars into its operational philosophy. Socially, it promotes inclusion, emotional well-being, and civic identity through integrated psychosocial services, culturally grounded curricula, and universal design. Economically, it stimulates job creation, investment opportunities, and local capacity building through strategic public-private partnerships and workforce training. Environmentally, it adopts climate-responsive architecture, renewable energy, and sustainability-focused learning as core components of school life.

Together, these dimensions elevate the Halban initiative beyond the traditional boundaries of schooling, positioning it as a replicable framework for sustainable development in Oman and the wider Gulf region.

1.9. Social Impact and Educational Equity

At the heart of the Halban model lies a commitment to social equity and emotional well-being. The school embeds full-time social workers, counselors, and behavioral therapists into its daily operations, offering both preventive and responsive interventions that reduce school dropout, enhance attendance, and strengthen student resilience (Boothby et al., 2019). These psychosocial services are not auxiliary; they form an essential infrastructure for inclusive and supportive learning.

In terms of classroom experience, the model ensures that all children, regardless of ability, socioeconomic status, or geographic location, have access to tailored, high-quality education. Inclusive classroom design, differentiated instructional methods, and assistive technologies guarantee that diverse learners can thrive side by side. Emotional development and interpersonal competence are further nurtured through facilities such as sensory rooms, recreational spaces, and therapeutic activity centers, which promote learning through play, movement, and reflection (Ma & Wang, 2022). These elements help reduce behavioral disruptions, foster peer relationships, and improve academic engagement.

Finally, the model integrates values-based curricula rooted in Islamic ethics and Omani heritage, cultivating civic identity, moderation, and cultural pride. This intentional cultural grounding counters the risks of alienation, cultural erosion, and extremism, while promoting responsible citizenship (Patabendige, 2023, Ben-Porath, 2023). Together, these layers form a cohesive ecosystem of social development that extends far beyond access, embedding inclusion, identity, and resilience into the core fabric of the school.

1.10. Economic Value and Local Development

Economically, the Halban School Complex is envisioned as a catalyst for local development and inclusive growth. Its construction and operation generate direct employment for educators, therapists, administrators, and support staff, while also engaging local professionals in architecture, engineering, and maintenance. This creates a multiplier effect that stimulates various sectors and supports the broader service economy.

The model is also designed to attract private sector participation through flexible ownership and co-financing schemes, including public-private partnerships (PPPs). Partnerships with universities foster workforce development and applied training pipelines, while contracts with local suppliers—catering, transportation, facility services—channel institutional spending into the surrounding economy. Moreover, long-term opportunities arise from internships, research collaboration, and professional certification programs integrated into the school’s ecosystem.

On a community level, the presence of a high-quality, inclusive school raises the attractiveness of the area for families, stabilizes housing markets, and reduces pressure on overcrowded urban schools. Over time, such institutions can serve as economic anchors that bridge regional disparities in educational access and opportunity, advancing both spatial equity and sustainable development.

1.11. Environmental Innovation and Climate Education

The environmental dimension of the Halban School Complex is integral to its educational and operational philosophy. The buildings are designed with energy-efficient architecture, solar energy systems, water reuse technologies, and eco-friendly construction materials. Landscaped green spaces and shaded outdoor learning areas enhance biodiversity, support student health, and improve attention and cognitive outcomes.

Environmental education is embedded across the curriculum through recycling programs, school gardens, and student-led climate action projects. These initiatives promote ecological citizenship from an early age and align with Oman’s international commitments under the UNFCCC, the Paris Agreement, and the UN Sustainable Development Goals—particularly Goals 4 (Quality Education), 13 (Climate Action), and 15 (Life on Land) (Zaidan et al., 2019; United Nations, 2023).

The school also plans to adopt low-emission transportation solutions such as electric buses, not only to reduce its carbon footprint but also to model sustainable practices for the wider community. In a region facing high climate vulnerability, the Halban model offers a replicable institutional response to environmental challenges, merging education, infrastructure, and behavior change into one cohesive system.

1.12. Core Components and Operational Structure of the Model

The Halban School Complex is structured as a phased educational project encompassing all levels of schooling, from nursery through grade 12. Phase I includes nursery, kindergarten, and primary levels (grades 1–6), while Phase II will serve preparatory and secondary students (grades 7–12). This gradual implementation approach supports scalability and responsiveness to demographic and socioeconomic dynamics in Oman.

The school operates through a dual model: a full-time boarding program designed for students from remote areas or with high support needs, and a flexible day-school option tailored to local families. Both streams are integrated within a bilingual curriculum (Arabic–English) that combines values-based instruction with global academic competencies.

Designed as an inclusive and developmentally supportive environment, the school features sensory integration rooms, adaptive classrooms for students with physical or learning disabilities, art and music studios, and multi-purpose halls. Full-time psychological and social support services are embedded into the school’s routine, ensuring that students across all stages receive targeted emotional and behavioral care. Social workers and counselors offer structured interventions that promote resilience, self-regulation, and emotional well-being.

A key innovation is the formal collaboration with national universities. The school hosts supervised practicum placements for students in social work, psychology, and education, offering mutual benefit: enhanced staffing for the school, and hands-on training for future professionals. These partnerships advance Oman’s national goals of localizing expertise and promoting experiential learning in higher education.

Beyond academics, the Halban model fosters cultural identity and creative expression. Students engage with Omani heritage and Islamic values through curriculum-integrated programs in traditional crafts, ethics, and history. At the same time, the school provides access to advanced digital learning tools, robotics, and STEM laboratories.

Experiential learning is emphasized through facilities like a school cinema room, internal broadcasting studio, and student-run spaces such as, a café and school garden, designed to promote autonomy, initiative, and applied learning. The campus also includes infrastructure for performing arts, astronomy, physical education, and environmental exploration, transforming the school into a dynamic hub for civic engagement and lifelong learning.

1.13. Environmental Integration and Green Infrastructure

Environmental sustainability is a foundational pillar of the Halban School Complex. The campus is designed with energy efficiency, ecological responsibility, and environmental learning as central priorities. All buildings incorporate passive cooling systems, solar panels, green roofs, and locally sourced, low-impact construction materials to reduce the school’s carbon footprint. Water conservation strategies—including greywater reuse and drip irrigation, further reinforce a commitment to responsible resource management.

Beyond its infrastructure, the Halban model embeds environmental values throughout school life. Students participate in hands-on projects via educational gardens, animal care zones, and sustainability-focused learning modules. A solar-powered greenhouse, falconry zone, and astronomy observatory not only promote environmental literacy but also foster cross-disciplinary thinking that connects science, culture, and heritage. These immersive experiences form part of the school’s identity as a living model of sustainability.

The school also partners with local and international environmental organizations to enhance curricular relevance and facilitate project-based collaboration. Instructional content is aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals—particularly Goals 4 (Quality Education), 13 (Climate Action), and 15 (Life on Land)—and tailored to Oman’s ecological and cultural realities. Field trips, school-wide campaigns, and science fairs help extend environmental awareness beyond the classroom and into the broader community, cultivating responsible citizenship and ecological stewardship.

1.14. Funding Strategy and Strategic Partnerships

The Halban School Complex adopts a diversified and context-sensitive funding model grounded in public–private partnerships, developmental finance, and multi-sector collaboration. This approach is essential in Oman’s evolving educational landscape, where innovative school models must balance mission-driven impact with financial sustainability.

With a projected cost of 2–3 million OMR, the project requires a capital structure that minimizes fiscal risk while ensuring long-term viability. Preliminary discussions with the Oman Investment Authority have confirmed potential support for up to 60% of expenditures related to smart infrastructure—hardware, cybersecurity, and digital platforms, which directly align with the nation’s digital transformation priorities.

The remaining capital will be sourced through private equity, philanthropic contributions, and development-oriented soft loans. Equity-based partnerships are being explored with construction and service providers to reduce upfront infrastructure costs.

In-kind and co-financing contributions from national institutions are also integral. These include:

The Ministry of Youth, Culture, and Sports (equestrian and athletic facilities)

Environmental agencies (green infrastructure and astronomy garden)

Religious endowments and foundations (eco-mosque and Quranic education)

Future financing may involve issuing development bonds or opening partial equity offerings to mission-aligned investors. This hybrid strategy ensures financial resilience, scalability, and institutional alignment, positioning the Halban model as a national benchmark for financially viable, socially committed, and pedagogically advanced schooling.

1.15. Equity, Affordability, and Inclusive Access

The Halban School Complex adopts a diversified and context-sensitive funding model grounded in public–private partnerships, developmental finance, and multi-sector collaboration. This approach is essential in Oman’s evolving educational landscape, where innovative school models must balance mission-driven impact with financial sustainability.

With a projected cost of 2–3 million OMR, the project requires a capital structure that minimizes fiscal risk while ensuring long-term viability. Preliminary discussions with the Oman Investment Authority have confirmed potential support for up to 60% of expenditures related to smart infrastructure—hardware, cybersecurity, and digital platforms, which directly align with the nation’s digital transformation priorities.

While the project owner remains responsible for the core educational facilities, a phased and risk-conscious implementation strategy has been adopted. Phase I will target early education (nursery to grade 6), which requires lower capital and allows for earlier revenue generation. In parallel, a partner real estate developer will build the external infrastructure (roads, utilities) as part of a mixed-use urban plan.

To further mitigate risk, the project explores conditional equity agreements with service providers, such as boarding, transport, and catering operators, who co-invest in exchange for medium-term contracts. These financial instruments, along with soft loans and philanthropic support, provide a layered structure that reduces front-loaded capital pressure while preserving operational control.

Complementing this financial architecture is a deep commitment to social equity in educational access. In a region where private education often exacerbates socioeconomic disparities (Peddada & Alhuthaifi, 2021), the Halban model implements a sliding-scale tuition system, calibrated to household income. This approach, inspired by globally respected systems such as Waldorf, Montessori, and Harvard early childhood programs (AWSNA, 2024; AMS, 2024; HGSE, 2025), ensures that financial limitations do not hinder access to opportunity.

Additionally, 10–15% of seats will be fully subsidized through zakat funds, CSR contributions, and philanthropic sponsorships, covering tuition, meals, transport, and boarding when needed. The school also applies a tiered pricing structure, separating basic academic instruction from optional services like after-school programs or boarding, ensuring both access and financial sustainability.

Through this inclusive economic architecture, the Halban model advances equity and access while remaining financially sound, fulfilling SDG targets 4.5 and 10.2, and operationalizing Oman Vision 2040’s call for human-centered, just development.

1.16. Comparative Analysis – Halban Model and Global Educational Frameworks

In recent years, sustainable education has evolved into a multidimensional endeavor encompassing curriculum innovation, social inclusion, environmental design, cultural relevance, and digital transformation (UNESCO, 2021). While global models have pioneered areas such as play-based learning and technology integration, many struggle to adapt to culturally rooted approaches that reflect local identities and values (Hayden & Thompson, 2013). Conversely, several Arab and Gulf systems continue to rely on imported educational frameworks—such as British, American, or IB systems—with varying degrees of localization and contextual adaptation (Romanowski et al., 2018).

A distinctive feature of the Halban model is its values-based, bilingual curriculum, which embeds Islamic ethics and Omani heritage into school life. This stands in contrast to Western models that adopt secular, multicultural orientations (Booth & Ainscow, 2011), and Gulf systems like those in the UAE or Qatar that prioritize international accreditation over cultural integration (Romanowski & Al Attiyah, 2020).

The Halban model also foregrounds play-based and sensory learning in early education, utilizing therapeutic environments to foster emotional, cognitive, and social development. This aligns with pedagogical best practices from Finland and Reggio Emilia-inspired models (Edwards et al., 2012) yet remains underused in many Arab systems dominated by formalism (Faour & Muasher, 2011). Its integration of psychosocial services responds to global post-pandemic calls for mental health support in schools (UNICEF, 2021).

Technological infrastructure is embedded both structurally and pedagogically, with cybersecurity, AI-assisted learning, and EdTech partnerships reflecting trends in Canada and Singapore (OECD, 2020). Simultaneously, its commitment to solar energy, green construction, and school gardens mirrors international environmental education standards—surpassing many underfunded or pilot-based regional efforts (Zaidan et al., 2019).

The model extends beyond academics into community development. Its university partnerships, student field placements, and multi-sector engagement reflect an ecosystem approach seen in some European networks (Epstein, 2018). By contrast, Gulf schools often operate hierarchically, with limited authority given to parent bodies or community-based learning (Mahboob & Elyas, 2017).

In addition to international benchmarks, the Halban model also surpasses existing national efforts. A notable example is Oman’s Green Schools Project, launched by the Ministry of Education to promote sustainability through recycling, water conservation, and renewable energy use. While commendable, the initiative focuses narrowly on environmental aspects and lacks integrated psychosocial, cultural, and digital components (Ministry of Education, 2023).

The Halban model, by contrast, offers a holistic approach that merges environmental responsibility with emotional well-being, inclusive pedagogy, cultural identity, and smart learning technologies. The following

Table 1 summarizes these key distinctions across global, regional, and local models.

1.17. Challenges, Recommendations, and Conclusion

While the Halban Smart and Inclusive School model presents a promising blueprint for educational transformation, its implementation is not without challenges. This section outlines the key barriers that may hinder execution, followed by targeted policy and design recommendations to address them. The section concludes by reflecting on the model’s broader significance and future applicability.

1.18. Implementation Challenges

Implementing such an integrated and contextually grounded school model requires navigating multiple layers of complexity. These challenges span institutional culture, funding structures, human resource constraints, and societal perceptions, each of which must be acknowledged to ensure successful adoption.