Submitted:

14 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. E-Cigarette Preparation

2.3. siRNA Transfection

2.4. Immunofluorescence Microscopy

2.5. Reagents

2.6. Trans-Endothelial Monolayer Electrical Resistance (TEER) Measurements

2.7. AFM Imaging

2.8. Statistical Significance and Data Analysis

3. Results

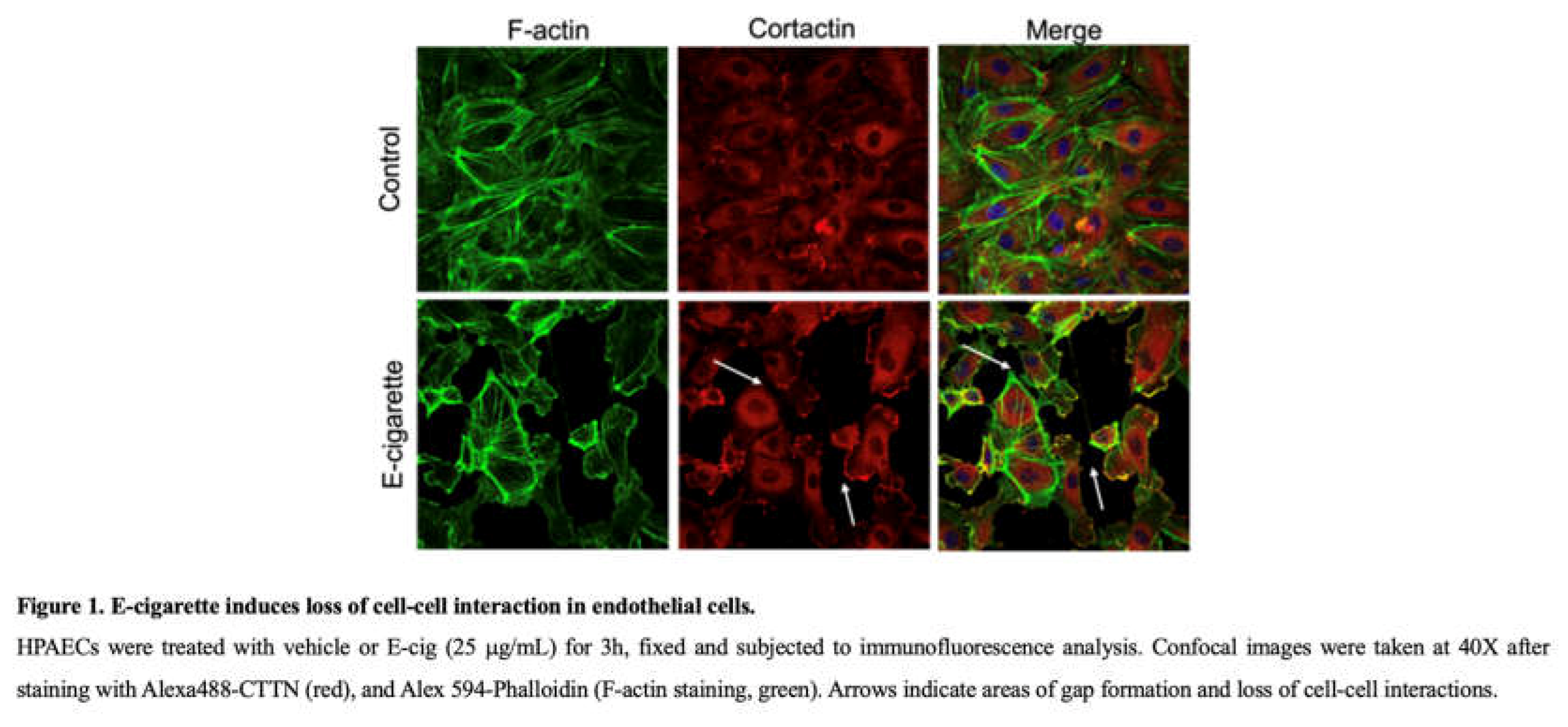

3.1. E-Cigarette Exposure Induces Cytoskeletal Rearrangement and Gap Formation in Lung ECs

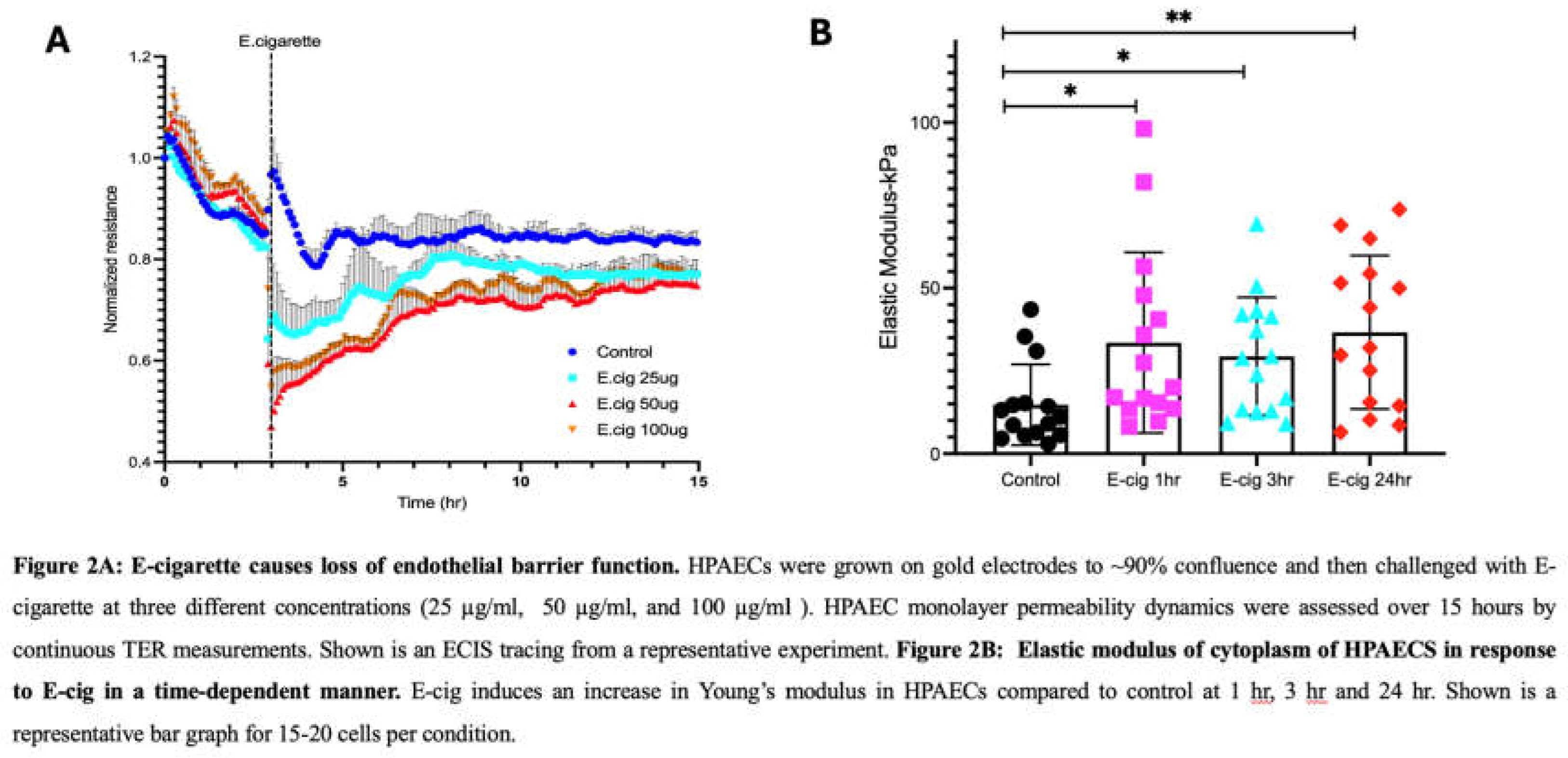

3.2. Trans-Endothelial Resistance Is Decreased by E-Cigarette Exposure in a Dose-Dependent Manner in Lung ECs

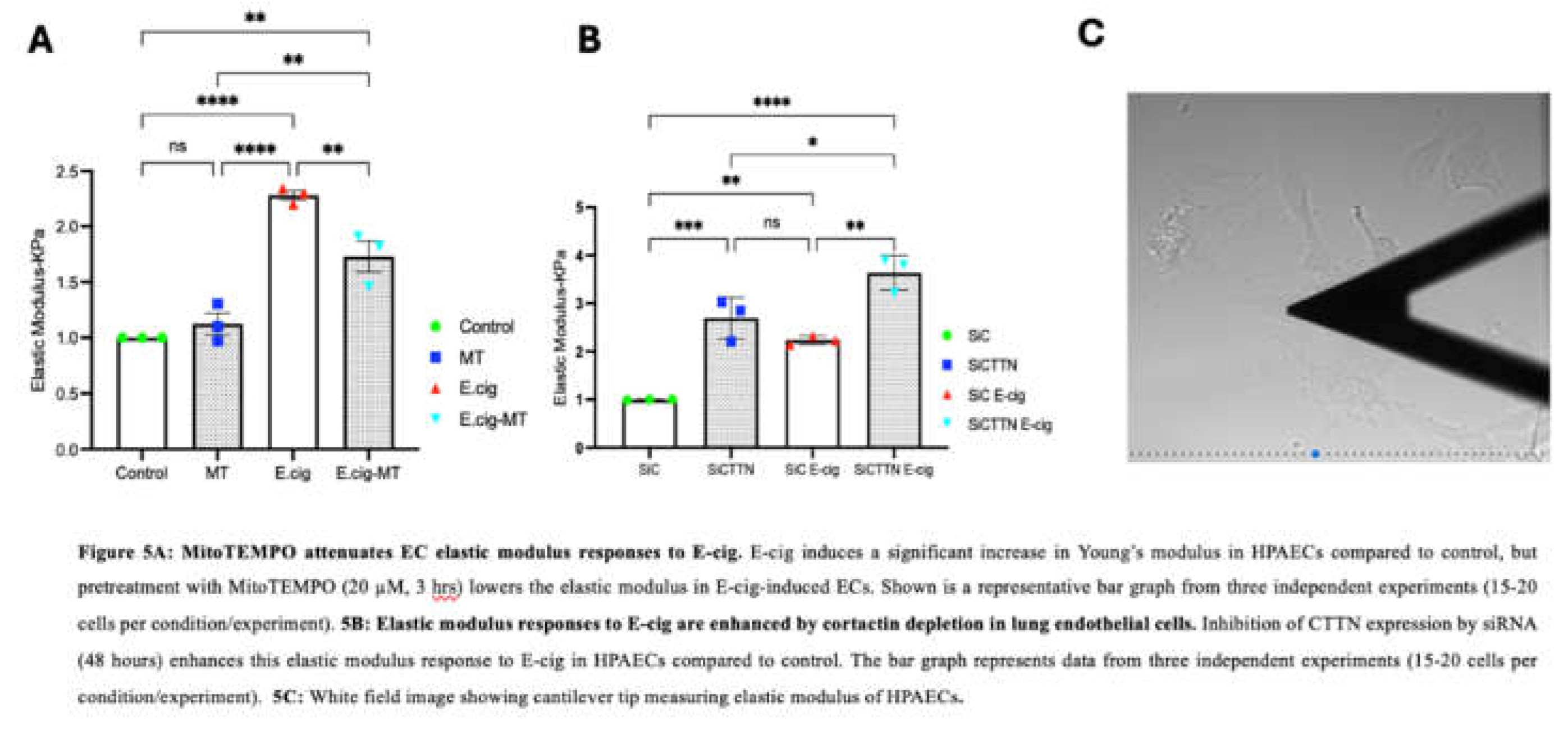

3.3. Elastic Modulus Magnitude Is Increased in Lung ECs by E-Cig Exposure

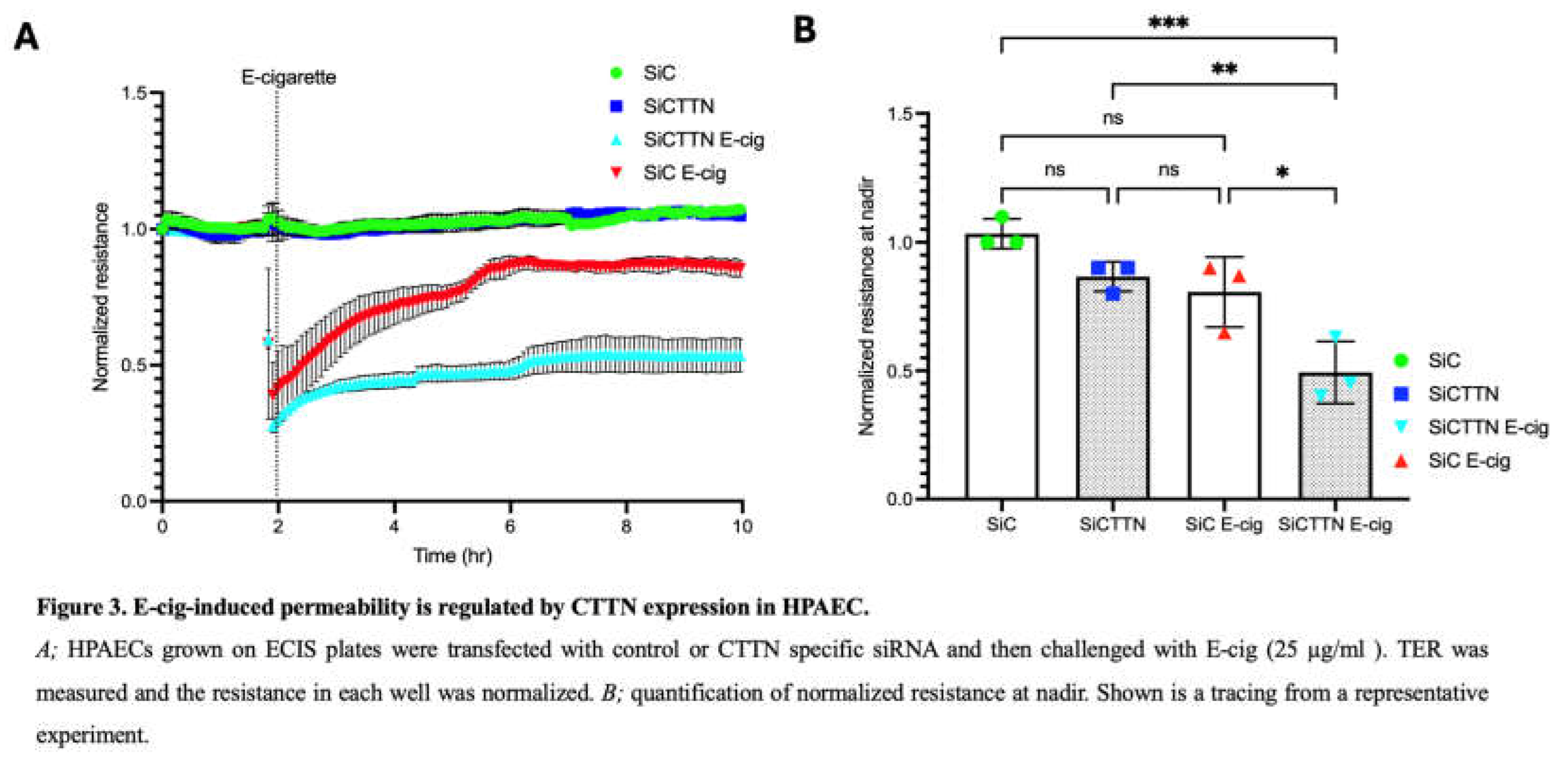

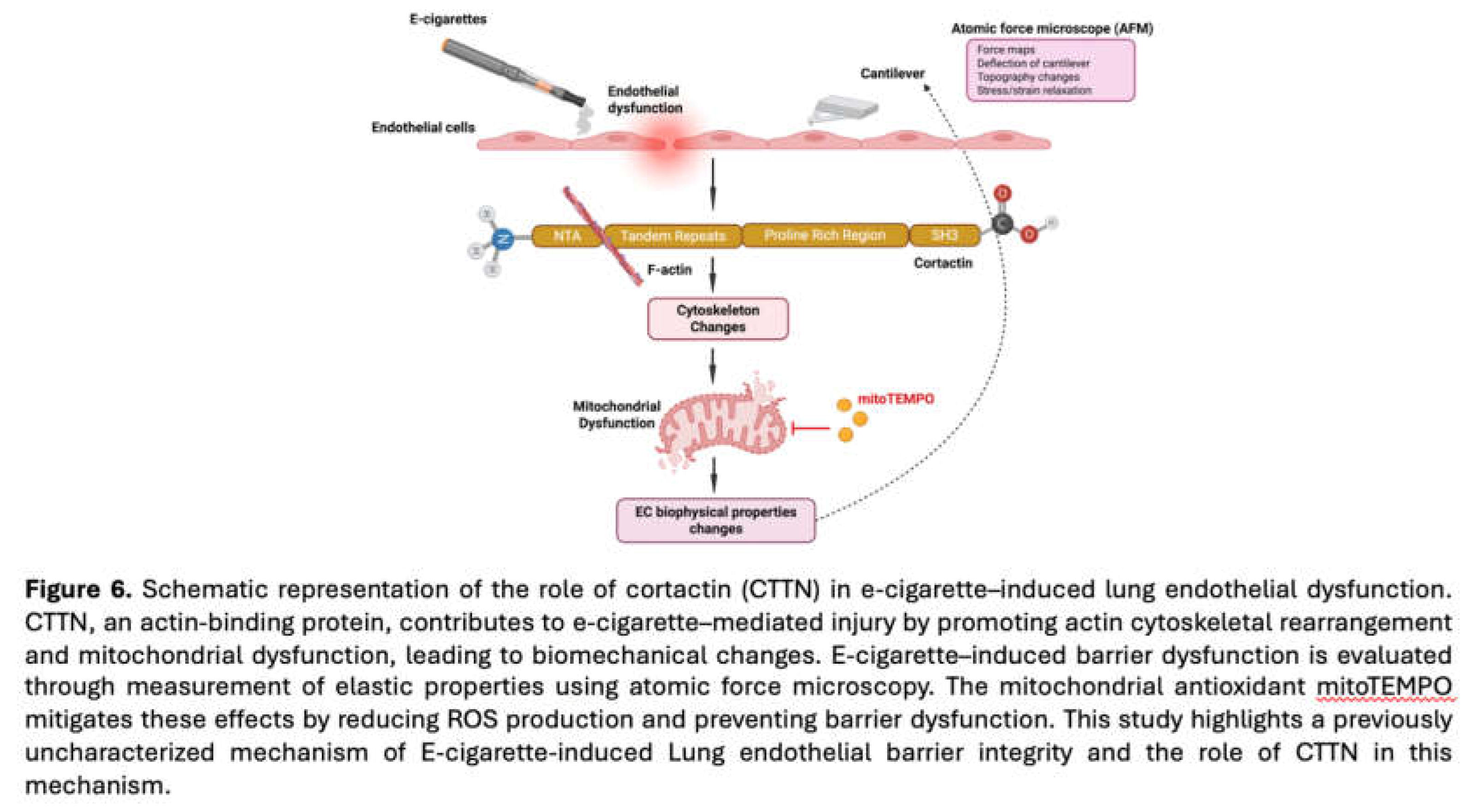

3.4. Cortactin Expression Modulates the Lung Barrier Effects of E-Cigarettes

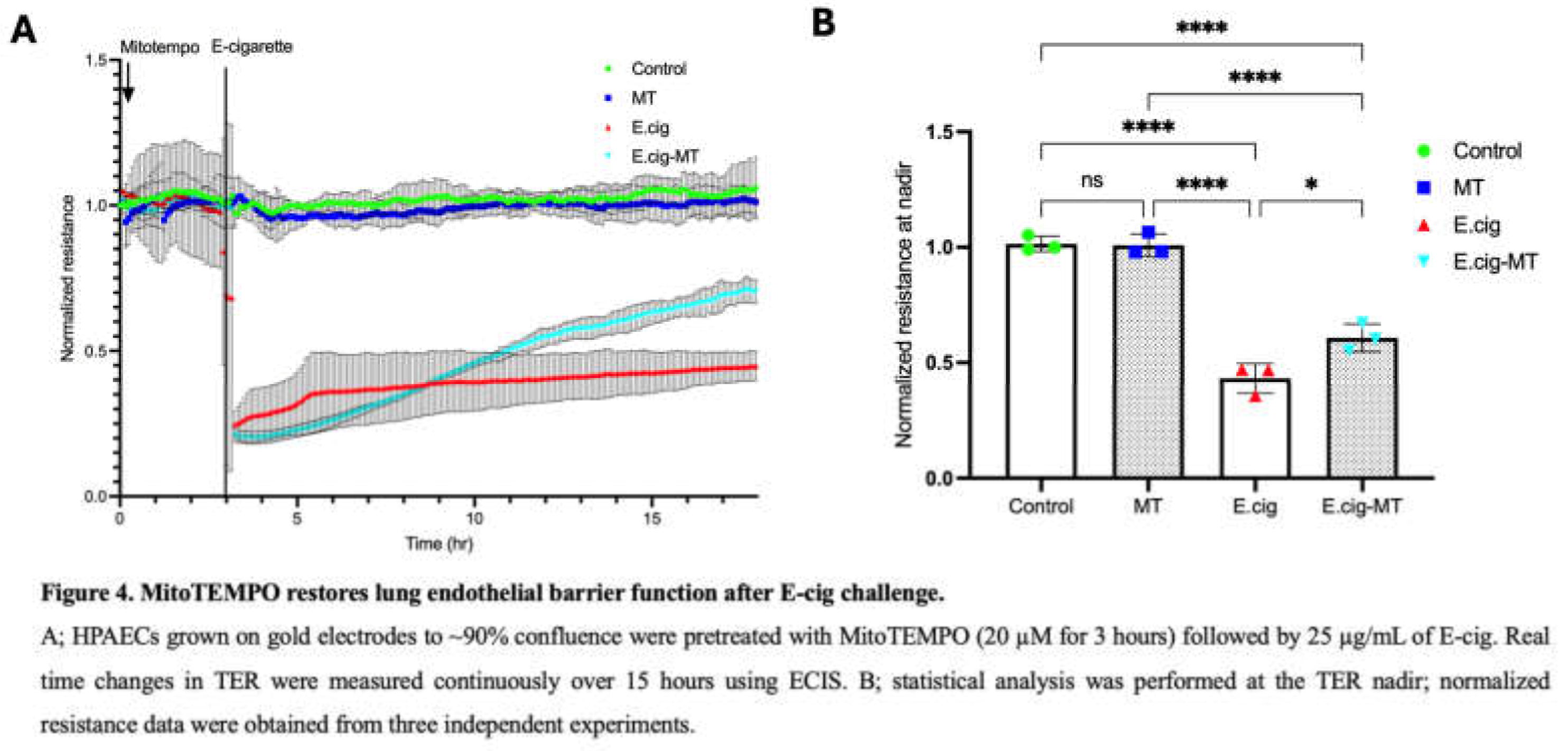

3.5. Role of MitoROS in E-Cig-Induced Lung EC Permeability

3.6. Mitochondrial ROS Participates in E-Cig-Induced Elastic Modulus Changes in Lung ECs

3.7. CTTN Expression Regulates E-Cig-Induced Elastic Modulus Responses in Lung Endothelial Cells

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Dockrell, M.; Morrison, R.; Bauld, L.; McNeill, A. E-Cigarettes: Prevalence and Attitudes in Great Britain. Nicotine Tob. Res. Off. J. Soc. Res. Nicotine Tob. 2013, 15, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, P.; Etter, J.-F.; Benowitz, N.; Eissenberg, T.; McRobbie, H. Electronic Cigarettes: Review of Use, Content, Safety, Effects on Smokers and Potential for Harm and Benefit. Addict. Abingdon Engl. 2014, 109, 1801–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizoń, M.; Maciejewski, D.; Kolonko, J. E-Cigarette or Vaping Product Use-Associated Acute Lung Injury (EVALI) as a Therapeutic Problem in Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Departments. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 2020, 52, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morjaria, J.B.; Mondati, E.; Polosa, R. E-Cigarettes in Patients with COPD: Current Perspectives. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2017, 12, 3203–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalininskiy, A.; Bach, C.T.; Nacca, N.E.; Ginsberg, G.; Marraffa, J.; Navarette, K.A.; McGraw, M.D.; Croft, D.P. E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use Associated Lung Injury (EVALI): Case Series and Diagnostic Approach. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Chen, W.; Moshensky, A.; Shakir, Z.; Khan, R.; Crotty Alexander, L.E.; Ware, L.B.; Aldaz, C.M.; Jacobson, J.R.; Dudek, S.M.; Natarajan, V.; Machado, R.F.; Singla, S. Cigarette Smoke and Nicotine-Containing Electronic-Cigarette Vapor Downregulate Lung WWOX Expression, Which Is Associated with Increased Severity of Murine Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021, 64, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, C.; Chahine, J.B.; Haykal, T.; Al Hageh, C.; Rizk, S.; Khnayzer, R.S. E-Cigarette Aerosol Induced Cytotoxicity, DNA Damages and Late Apoptosis in Dynamically Exposed A549 Cells. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 127874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; Majeste, A.; Hanus, J.; Wang, S. E-Cigarette Aerosol Exposure Induces Reactive Oxygen Species, DNA Damage, and Cell Death in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Toxicol. Sci. Off. J. Soc. Toxicol. 2016, 154, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bleher, R.; Brown, M.E.; Garcia, J.G.N.; Dudek, S.M.; Shekhawat, G.S.; Dravid, V.P. Nano-Biomechanical Study of Spatio-Temporal Cytoskeleton Rearrangements That Determine Subcellular Mechanical Properties and Endothelial Permeability. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birukova, A.A.; Arce, F.T.; Moldobaeva, N.; Dudek, S.M.; Garcia, J.G.N.; Lal, R.; Birukov, K.G. Endothelial Permeability Is Controlled by Spatially Defined Cytoskeletal Mechanics: Atomic Force Microscopy Force Mapping of Pulmonary Endothelial Monolayer. Nanomedicine Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2009, 5, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandela, M.; Letsiou, E.; Natarajan, V.; Ware, L.B.; Garcia, J.G.N.; Singla, S.; Dudek, S.M. Cortactin Modulates Lung Endothelial Apoptosis Induced by Cigarette Smoke. Cells 2021, 10, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Gottlieb, E.; Rounds, S. Effects of Cigarette Smoke on Pulmonary Endothelial Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2018, 314, L743–L756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, J.R.; Dudek, S.M.; Singleton, P.A.; Kolosova, I.A.; Verin, A.D.; Garcia, J.G.N. Endothelial Cell Barrier Enhancement by ATP Is Mediated by the Small GTPase Rac and Cortactin. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2006, 291, L289–L295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, A.; Lawson, C.; Ghassemian, M.; Schlaepfer, D.D. Cortactin as a Target for FAK in the Regulation of Focal Adhesion Dynamics. PloS One 2012, 7, e44041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandela, M.; Belvitch, P.; Garcia, J.G.N.; Dudek, S.M. Cortactin in Lung Cell Function and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belvitch, P.; Htwe, Y.M.; Brown, M.E.; Dudek, S. Cortical Actin Dynamics in Endothelial Permeability. Curr. Top. Membr. 2018, 82, 141–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, F.T.; Younger, S.; Gaber, A.A.; Mascarenhas, J.B.; Rodriguez, M.; Dudek, S.M.; Garcia, J.G.N. Lamellipodia Dynamics and Microrheology in Endothelial Cell Paracellular Gap Closure. Biophys. J. 2023, 122, 4730–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavara, N.; Chadwick, R.S. Determination of the Elastic Moduli of Thin Samples and Adherent Cells Using Conical Atomic Force Microscope Tips. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 733–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Xia, Y.; Sandig, M.; Yang, J. Characterization of Cell Elasticity Correlated with Cell Morphology by Atomic Force Microscope. J. Biomech. 2012, 45, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, S.E.; Jin, Y.-S.; Rao, J.; Gimzewski, J.K. Nanomechanical Analysis of Cells from Cancer Patients. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007, 2, 780–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Condeelis, J. Regulation of the Actin Cytoskeleton in Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1773, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekka, M.; Gil, D.; Pogoda, K.; Dulińska-Litewka, J.; Jach, R.; Gostek, J.; Klymenko, O.; Prauzner-Bechcicki, S.; Stachura, Z.; Wiltowska-Zuber, J.; Okoń, K.; Laidler, P. Cancer Cell Detection in Tissue Sections Using AFM. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 518, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.; Gaikwad, R.M.; Subba-Rao, V.; Woodworth, C.D.; Sokolov, I. Atomic Force Microscopy Detects Differences in the Surface Brush of Normal and Cancerous Cells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htwe, Y.M.; Wang, H.; Belvitch, P.; Meliton, L.; Bandela, M.; Letsiou, E.; Dudek, S.M. Group V Phospholipase A2 Mediates Endothelial Dysfunction and Acute Lung Injury Caused by Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Cells 2021, 10, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Master, E.; Paul, A.; Lazarko, D.; Aguilar, V.; Ahn, S.J.; Lee, J.C.; Minshall, R.D.; Levitan, I. Caveolin-1 Is a Primary Determinant of Endothelial Stiffening Associated with Dyslipidemia, Disturbed Flow, and Ageing. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Sun, B.; Sammani, S.; Dudek, S.M.; Belvitch, P.; Camp, S.M.; Zhang, D.; Bime, C.; Garcia, J.G.N. Genetic and Epigenetic Regulation of Cortactin (CTTN) by Inflammatory Factors and Mechanical Stress in Human Lung Endothelial Cells. Biosci. Rep. 2024, 44, BSR20231934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belvitch, P.; Dudek, S.M. Role of FAK in S1P-Regulated Endothelial Permeability. Microvasc. Res. 2012, 83, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Dudek, S.M. Regulation of Vascular Permeability by Sphingosine 1-Phosphate. Microvasc. Res. 2009, 77, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.N.; Belvitch, P.; Demeritte, R.; Garcia, J.G.N.; Letsiou, E.; Dudek, S.M. Arg Mediates LPS-Induced Disruption of the Pulmonary Endothelial Barrier. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2020, 128–129, 106677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Letsiou, E.; Wang, H.; Belvitch, P.; Meliton, L.N.; Brown, M.E.; Bandela, M.; Chen, J.; Garcia, J.G.N.; Dudek, S.M. MRSA-Induced Endothelial Permeability and Acute Lung Injury Are Attenuated by FTY720 S-Phosphonate. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2022, 322, L149–L161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Epshtein, Y.; Sammani, S.; Quijada, H.; Chen, W.; Bandela, M.; Desai, A.A.; Garcia, J.G.N.; Jacobson, J.R. UCHL1, a Deubiquitinating Enzyme, Regulates Lung Endothelial Cell Permeability in Vitro and in Vivo. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2021, 320, L497–L507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryadevara, V.; Huang, L.; Kim, S.-J.; Cheresh, P.; Shaaya, M.; Bandela, M.; Fu, P.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.; Di Paolo, G.; Kamp, D.W.; Natarajan, V. Role of Phospholipase D in Bleomycin-Induced Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Generation, Mitochondrial DNA Damage, and Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2019, 317, L175–L187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layden, J.E.; Ghinai, I.; Pray, I.; Kimball, A.; Layer, M.; Tenforde, M.W.; Navon, L.; Hoots, B.; Salvatore, P.P.; Elderbrook, M.; Haupt, T.; Kanne, J.; Patel, M.T.; Saathoff-Huber, L.; King, B.A.; Schier, J.G.; Mikosz, C.A.; Meiman, J. Pulmonary Illness Related to E-Cigarette Use in Illinois and Wisconsin - Final Report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 903–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birukov, K.G.; Birukova, A.A.; Dudek, S.M.; Verin, A.D.; Crow, M.T.; Zhan, X.; DePaola, N.; Garcia, J.G.N. Shear Stress-Mediated Cytoskeletal Remodeling and Cortactin Translocation in Pulmonary Endothelial Cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2002, 26, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, A.M.; Izumo, S. Mechanism of Endothelial Cell Shape Change and Cytoskeletal Remodeling in Response to Fluid Shear Stress. J. Cell Sci. 1996, 109 Pt 4, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janmey, P.A.; Miller, R.T. Mechanisms of Mechanical Signaling in Development and Disease. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124 Pt 1, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kihara, T.; Nakamura, C.; Suzuki, M.; Han, S.-W.; Fukazawa, K.; Ishihara, K.; Miyake, J. Development of a Method to Evaluate Caspase-3 Activity in a Single Cell Using a Nanoneedle and a Fluorescent Probe. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 25, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandela, M.; Suryadevara, V.; Fu, P.; Reddy, S.P.; Bikkavilli, K.; Huang, L.S.; Dhavamani, S.; Subbaiah, P.V.; Singla, S.; Dudek, S.M.; Ware, L.B.; Ramchandran, R.; Natarajan, V. Role of Lysocardiolipin Acyltransferase in Cigarette Smoke-Induced Lung Epithelial Cell Mitochondrial ROS, Mitochondrial Dynamics, and Apoptosis. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 80, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.S.; Kotha, S.R.; Avasarala, S.; VanScoyk, M.; Winn, R.A.; Pennathur, A.; Yashaswini, P.S.; Bandela, M.; Salgia, R.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Kagan, V.E.; Zhu, X.; Reddy, S.P.; Sudhadevi, T.; Punathil-Kannan, P.-K.; Harijith, A.; Ramchandran, R.; Bikkavilli, R.K.; Natarajan, V. Lysocardiolipin Acyltransferase Regulates NSCLC Cell Proliferation and Migration by Modulating Mitochondrial Dynamics. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 13393–13406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).