Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Preparation of ECA and CS-Conditioned Media

2.4. Cell Exposure

2.5. Microscopy and Cell Morphology

2.6. Cell Viability Test

2.7. Flow Cytometry - Cell Cycle Analysis

2.8. Assessment of Oxidative Stress

2.9. Glutathione Level

2.10. Superoxide Dismutase Activity

2.11. Intracellular IL-6, TNF-α and NF-κB

2.12. Binary Fluorescence Scatterplots of IL-6 vs TNF-α

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

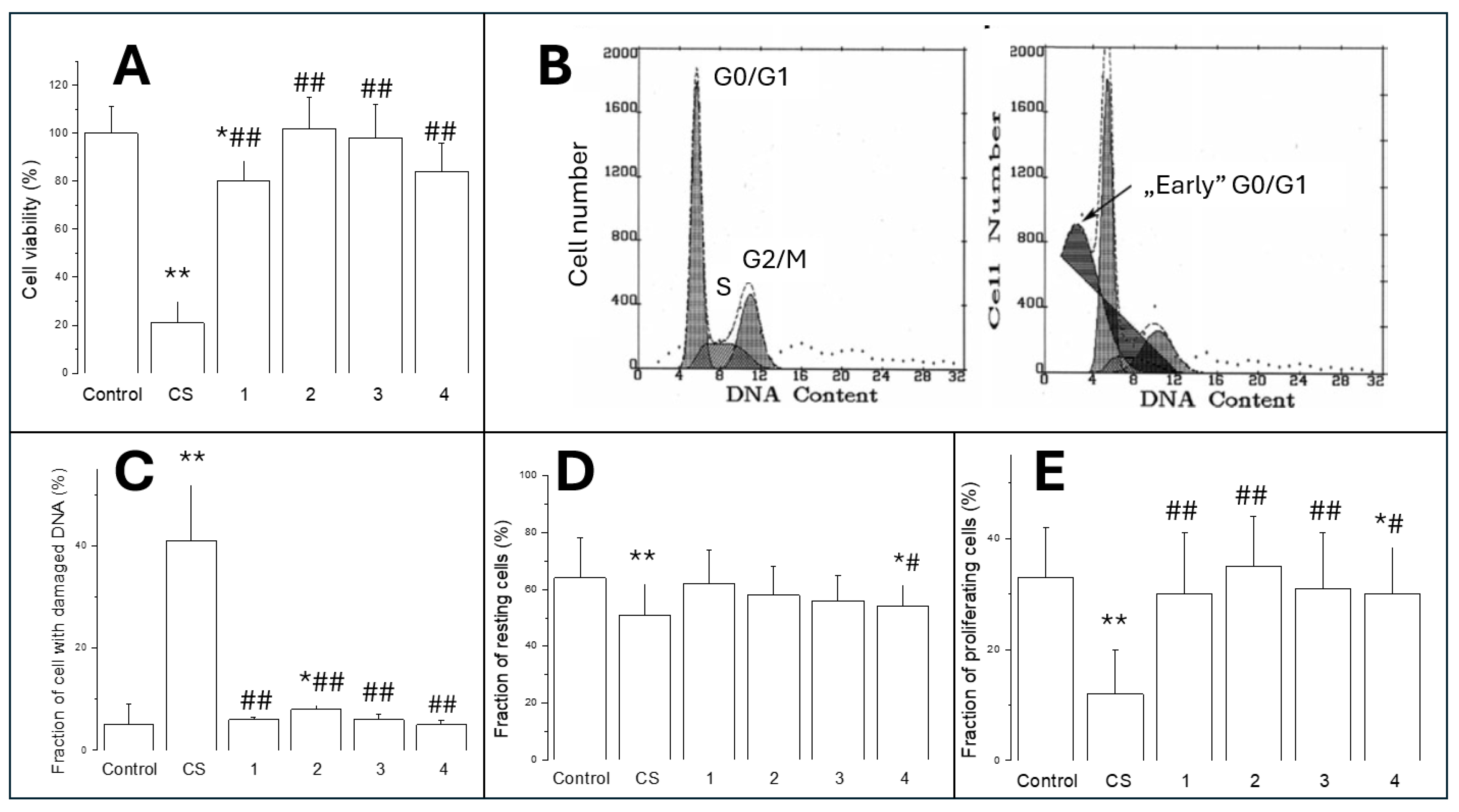

3.1. Panel 1: Cell Morphology, Growth, Cytotoxicity and DNA Damage

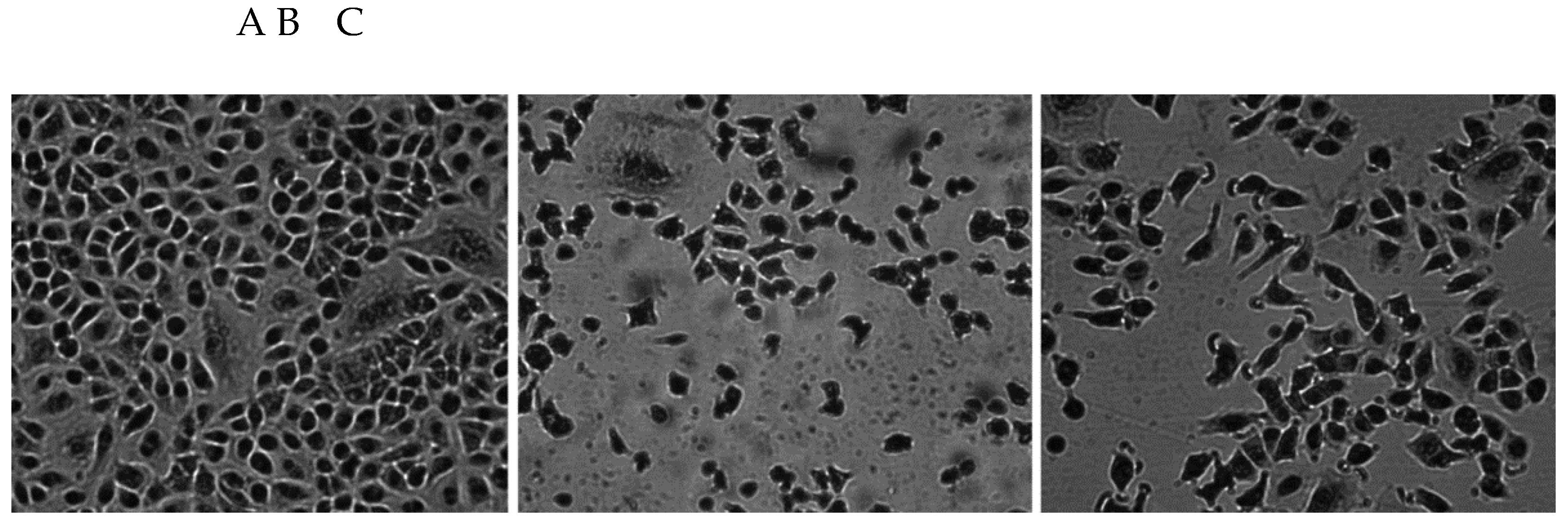

3.1.1. Morphology of A549 Cells

3.1.2. Cell Viability (MTT Test)

3.1.3. Cytotoxicity/Analysis of Cell Cycle

3.1.4. Cell Proliferation

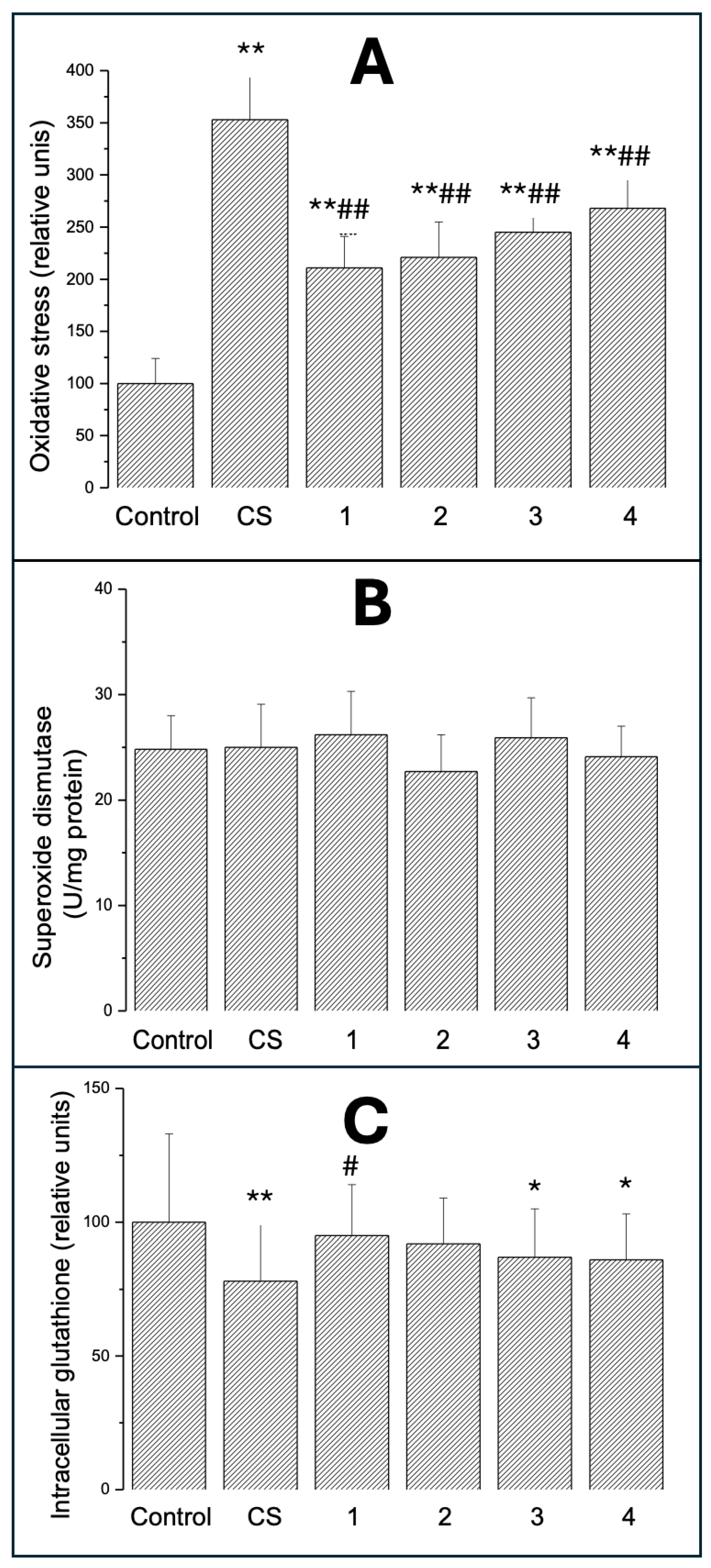

3.2. Panel 2: Oxidative Stress

3.2.1. Intracellular Oxidative Stress

3.2.2. SOD Activity

3.2.3. Intracellular GSH

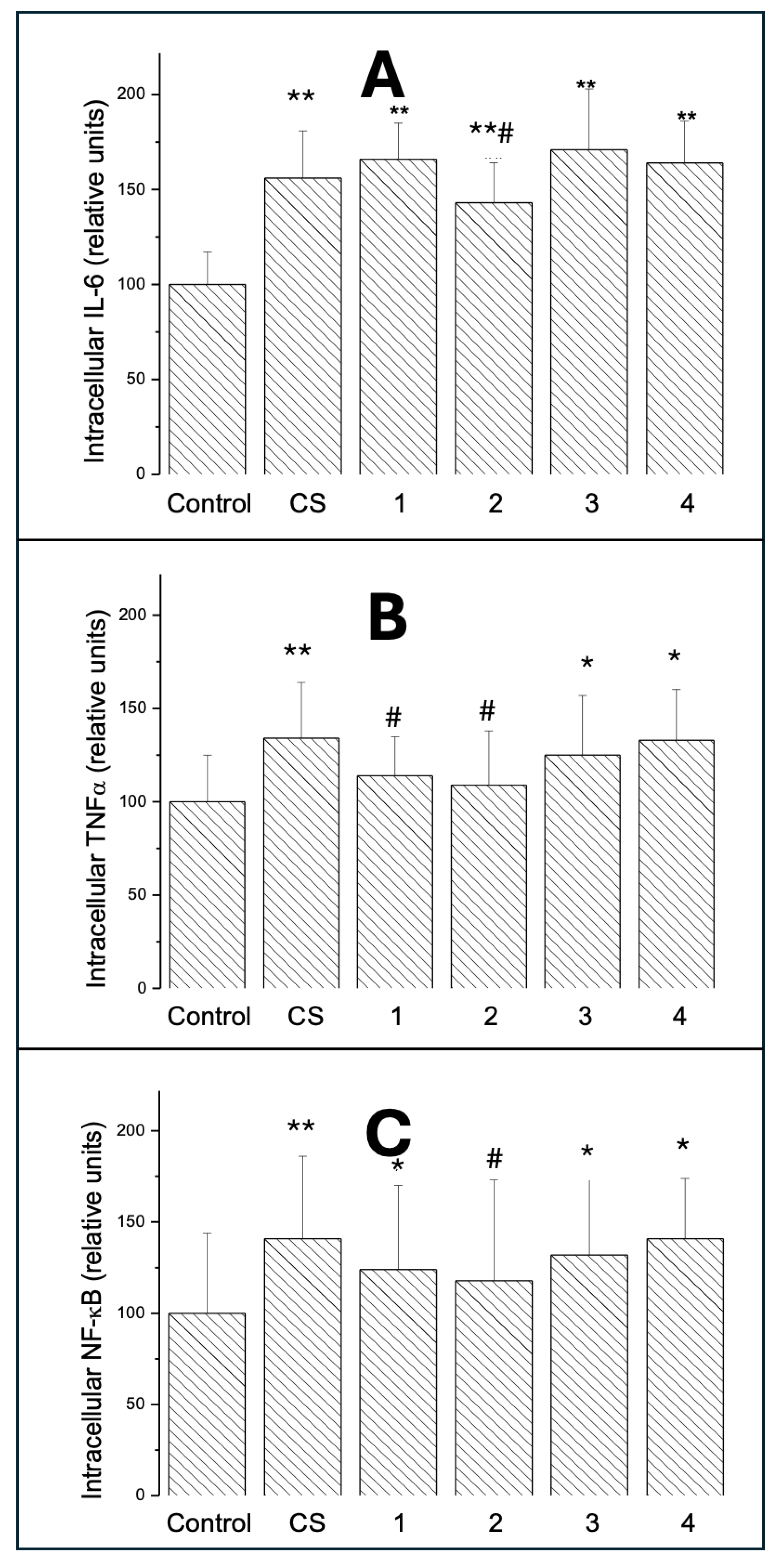

3.3. Panel 3: Inflammation

3.3.1. Intracellular IL-6

3.3.2. Intracellular TNF-

3.3.3. Intracellular NF-B

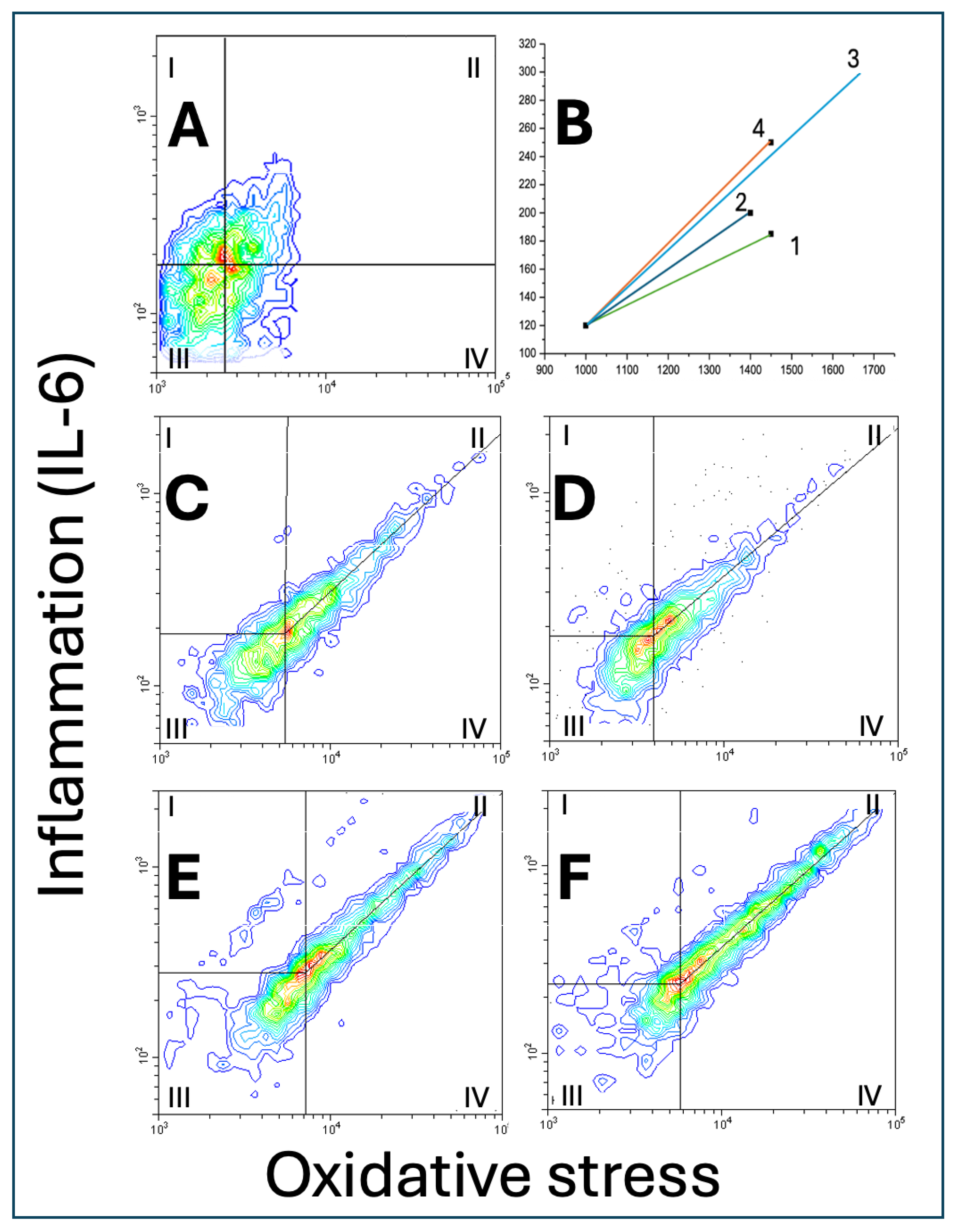

3.4. Panel 4: Double Fluorescence Scatterplots

3.4.1. Scatter Area

3.4.2. Vector Size

3.4.3. Slopes of the Central Tendency Line

3.4.4. Cell Distribution

4. Discussion

Study Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

References

- Cullen, K.A.; Gentzke, A.S.; Sawdey, M.D.; Chang, J.T.; Anic, G.M.; Wang, T.W.; Creamer, M.R.; Jamal, A.; Ambrose, B.K.; King, B.A. e-Cigarette Use Among Youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA 2019, 322, 2095–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindson, N.; Butler, A.R.; McRobbie, H.; Bullen, C.; Hajek, P.; Begh, R.; Theodoulou, A.; Notley, C.; Rigotti, N.A.; Turner, T.; Livingstone-Banks, J.; Morris, T.; Hartmann-Boyce, J. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2024, 1, CD010216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goniewicz, M.L.; Gawron, M.; Smith, D.M.; Peng, M.; Jacob P3rd Benowitz, N.L. Exposure to Nicotine and Selected Toxicants in Cigarette Smokers Who Switched to Electronic Cigarettes: A Longitudinal Within-Subjects Observational Study. Nicotine Tob Res 2017, 19, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Villarreal, A.; Bozhilov, K.; Lin, S.; Talbot, P. Metal and silicate particles including nanoparticles are present in electronic cigarette cartomizer fluid and aerosol. PLoS One 2013, 8, e57987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleiman, M.; Logue, J.M.; Montesinos, V.N.; Russell, M.L.; Litter, M.I.; Gundel, L.A.; Destaillats, H. Emissions from Electronic Cigarettes: Key Parameters Affecting the Release of Harmful Chemicals. Environ Sci Technol 2016, 50, 9644–9651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talih, S.; Balhas, Z.; Eissenberg, T.; Salman, R.; Karaoghlanian, N.; El Hellani, A.; Baalbaki, R.; Saliba, N.; Shihadeh, A. Effects of user puff topography, device voltage, and liquid nicotine concentration on electronic cigarette nicotine yield: measurements and model predictions. Nicotine Tob Res 2015, 17, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieber, M.; Smith, B.; Szakal, A.; Nelson-Rees, W.; Todaro, G. A continuous tumor-cell line from a human lung carcinoma with properties of type II alveolar epithelial cells. Int J Cancer 1976, 17, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.A.; Oster, C.G.; Mayer, M.M.; Avery, M.L.; Audus, K.L. Characterization of the A549 cell line as a type II pulmonary epithelial cell model for drug metabolism. Exp Cell Res 1998, 243, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabba, S.V.; Diaz, A.N.; Erythropel, H.C.; Zimmerman, J.B.; Jordt, S.E. Chemical Adducts of Reactive Flavor Aldehydes Formed in E-Cigarette Liquids Are Cytotoxic and Inhibit Mitochondrial Function in Respiratory Epithelial Cells. Nicotine Tob Res 2020, 22 (Suppl 1), S25–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay-Greene, F.; Donnellan, S.; Vass, S. Analysing the acute toxicity of e-cigarette liquids and their vapour on human lung epithelial (A549) cells in vitro. Toxicol Rep. 2025, 15, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, V.; Rahimy, M.; Korrapati, A.; Xuan, Y.; Zou, A.E.; Krishnan, A.R.; Tsui, T.; Aguilera, J.A.; Advani, S.; Crotty Alexander, L.E.; Brumund, K.T.; Wang-Rodriguez, J.; Ongkeko, W.M. Electronic cigarettes induce DNA strand breaks and cell death independently of nicotine in cell lines. Oral Oncol 2016, 52, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effah, F.; Elzein, A.; Taiwo, B.; Baines, D.; Bailey, A.; Marczylo, T. In Vitro high-throughput toxicological assessment of E-cigarette flavors on human bronchial epithelial cells and the potential involvement of TRPA1 in cinnamon flavor-induced toxicity. Toxicology 2023, 496, 153617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, V.; Manyanga, J.; Brame, L.; McGuire, D.; Sadhasivam, B.; Floyd, E.; Rubenstein, D.A.; Ramachandran, I.; Wagener, T.; Queimado, L. Electronic cigarette aerosols suppress cellular antioxidant defenses and induce significant oxidative DNA damage. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0177780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeschen, C.; Jang, J.J.; Weis, M.; Pathak, A.; Kaji, S.; Hu, R.S.; Tsao, P.S.; Johnson, F.L.; Cooke, J.P. Nicotine stimulates angiogenesis and promotes tumor growth and atherosclerosis. Nat Med 2001, 7, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.; Rizwani, W.; Banerjee, S.; Kovacs, M.; Haura, E.; Coppola, D.; Chellappan, S. Nicotine promotes tumor growth and metastasis in mouse models of lung cancer. PLoS One 2009, 4, e7524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behar, R.Z.; Davis, B.; Wang, Y.; Bahl, V.; Lin, S.; Talbot, P. Identification of toxicants in cinnamon-flavored electronic cigarette refill fluids. Toxicol In Vitro 2014, 28, 198–08. [Google Scholar]

- Omaiye, E.E.; Luo, W.; McWhirter, K.J.; Pankow, J.F.; Talbot, P. Disposable Puff Bar Electronic Cigarettes: Chemical Composition and Toxicity of E-liquids and a Synthetic Coolant. Chem Res Toxicol 2022, 35, 1344–1358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caruso, M.; Distefano, A.; Emma, R.; Zuccarello, P.; Copat, C.; Ferrante, M.; Carota, G.; Pulvirenti, R.; Polosa, R.; Missale, G.A.; Rust, S.; Raciti, G.; Li Volti, G. In vitro cytoxicity profile of e-cigarette liquid samples on primary human bronchial epithelial cells. Drug Test Anal 2023, 15, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.S.; Wu, X.R.; Lee, H.W.; Xia, Y.; Deng, F.M.; Moreira, A.L.; Chen, L.C.; Huang, W.C.; Lepor, H. Electronic-cigarette smoke induces lung adenocarcinoma and bladder urothelial hyperplasia in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019, 116, 21727–21731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, L.; Foley, G. E-cigarettes and respiratory health: the latest evidence. J Physiol 2020, 598, 5027–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.A.; Oster, C.G.; Mayer, M.M.; Avery, M.L.; Audus, K.L. Characterization of the A549 cell line as a type II pulmonary epithelial cell model for drug metabolism. Exp Cell Res 1998, 243, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szoka, P.; Lachowicz, J.; Cwiklińska, M.; Lukaszewicz, A.; Rybak, A.; Baranowska, U.; Holownia, A. Cigarette Smoke-Induced Oxidative Stress and Autophagy in Human Alveolar Epithelial Cell Line (A549 Cells). Adv Exp Med Biol 2019, 1176, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. Journal of Immunological Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindeløv, L.L.; Christensen, I.J.; Nissen, N.I. A detergent-trypsin method for the preparation of nuclei for flow cytometric DNA analysis. Cytometry 1983, 3, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Joseph, J.A. Quantifying cellular oxidative stress by dichlorofluorescein assay using microplate reader. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 1999, 27, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, V.; Jaganathan, R.; Chinnaiyan, M.; Chengizkhan, G.; Sadhasivam, B.; Manyanga, J.; Ramachandran, I.; Queimado, L. E-Cigarette effects on oral health: A molecular perspective. Food Chem Toxicol 2025, 196, 115216. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, S.R.; Jang, J.; Park, S.M.; Ryu, S.M.; Cho, S.J.; Yang, S.R. Cigarette Smoke-Induced Respiratory Response: Insights into Cellular Processes and Biomarkers. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthumalage, T.; Lamb, T.; Friedman, M.R.; Rahman, I. E-cigarette flavored pods induce inflammation, epithelial barrier dysfunction, and DNA damage in lung epithelial cells and monocytes. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 19035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wen, C. The risk profile of electronic nicotine delivery systems, compared to traditional cigarettes, on oral disease: a review. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1146949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzelli, S.; De Flora, S.; Bagnasco, M.; Hietanen, E.; Camus, A.M.; Saracci, R.; Izzotti, A.; Bartsch, H.; Giuntini, C. Carcinogen metabolism studies in human bronchial and lung parenchymal tissues. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989, 140, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, G.D.; Wingfors, H.; Uski, O.; Hedman, L.; Ekstrand-Hammarström, B.; Bosson, J.; Lundbäck, M. The toxic potential of a fourth-generation E-cigarette on human lung cell lines and tissue explants. J Appl Toxicol 2019, 39, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford, R.; Smith, G.; Rothwell, E.; Martin, S.; Medhane, R.; Casentieri, D.; Daunt, A.; Freiberg, G.; Hollings, M. A multi-organ, lung-derived inflammatory response following in vitro airway exposure to cigarette smoke and next-generation nicotine delivery products. Toxicol Lett 2023, 387, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Potlapalli, R.; Quan, H.; Chen, L.; Xie, Y.; Pouriyeh, S.; Sakib, N.; Liu, L.; Xie, Y. Exploring DNA Damage and Repair Mechanisms: A Review with Computational Insights. BioTech (Basel) 2024, 13, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Milara, J.; Cortijo, J. Tobacco, inflammation, and respiratory tract cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2012, 18, 3901–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoal, C.; Granjo, P.; Mexia, P.; Gallego, D.; Adubeiro Lourenço, R.; Sharma, S.; Pérez, B.; Castro-Caldas, M.; Grosso, A.R.; Dos Reis Ferreira, V.; Videira, P.A. Unraveling the biological potential of skin fibroblast: responses to TNF-α, highlighting intracellular signaling pathways and secretome. Immunol Lett 2025, 276, 107057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovac, S.; Domijan, A.M.; Walker, M.C.; Abramov, A.Y. Seizure activity results in calcium- and mitochondria-independent ROS production via NADPH and xanthine oxidase activation. Cell Death Dis 2014, 5, e1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čapek, J.; Roušar, T. Detection of Oxidative Stress Induced by Nanomaterials in Cells-The Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species and Glutathione. Molecules 2021, 26, 4710. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Güler, M.C.; Tanyeli, A.; Ekinci Akdemir, F.N.; Eraslan, E.; Özbek Şebin, S.; Güzel Erdoğan, D.; Nacar, T. An Overview of Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury: Review on Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Response. Eurasian J Med 2022, 54 (Suppl1), 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Marzoog, B.A. Cytokines and Regulating Epithelial Cell Division. Curr Drug Targets 2024, 25, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voirin, A.C.; Perek, N.; Roche, F. Inflammatory stress induced by a combination of cytokines (IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α) leads to a loss of integrity on bEnd.3 endothelial cells in vitro BBB model. Brain Res 2020, 1730, 146647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Nie, X.K.; Chen, Z.C.; Zhou, S.J.; Lin, X.H.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, D.; Xiao, B.Y.; Jiang, S.Q.; Huang, W.Y.; Lin, M.H.; Wang, Y.J. Mechanism Study on Inhibition of EPHA2 Expression Impaired Skin Barrier Function by Gefitinib. Exp Dermatol 2025, 34, e70145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam, A.R.; Kucera, C.; Srivastava, S.; Paily, R.; Stephens, D.; Lorkiewicz, P.; Wilkey, D.W.; Merchant, M.; Bhatnagar, A.; Carll, A.P. Acute and Persistent Cardiovascular Effects of Menthol E-Cigarettes in Mice. J Am Heart Assoc 2025, 14, e037420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Scatter area, vector size, slope of the central tendency line and distribution of A549 cells on scatterplots of oxidative stress vs. IL-6 | ||||

| (relative units) | ECE 1 | ECE 2 | ECE 3 | ECE 4 |

| Scatter area | 101.1 ± 13.7 | 100.0 ± 9.1 | 110.2 ± 16.4 | 115.4 ± 10.2*^ |

| Vector size | 1.0 ± 0.21 | 1.0 ± 0.19 | 1.83 ± 0.22**^^ | 1.29 ± 0.17*^^## |

| Slope of the central tendency line | 0.90 ± 0.10 | 0.83 ± 0.11 | 0.97 ± 0.12 | 0.90 ± 0.15 |

| Zone I cells | 2.9 ± 0.31 | 3.7 ± 0.35* | 3.5 ± 0.40 | 4.0 ± 0.51** |

| Zone II cells | 8.9 ± 0.43 | 10.3 ± 0.97** | 12.6 ± 0.77**^^ | 17.7 ± 0.61**^^## |

| Zone III cell | 11.2 ± 1.04 | 12.5 ± 0.98 | 12.3 ± 0.87 | 15.4 ± 1.45**^^## |

| Zone IV cells | 77.0 ± 9.4 | 73.5 ± 10.2 | 71.6 ± 9.1 | 62.9 ± 9.7* |

| II/IV ratio | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.03*^ | 0.28 ± 0.06**^^# |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).