1. Introduction

“Human beings learn and do things that have never been done before.” [

1]

The capacity for creative improvisation is one of the elements that characterizes human action. No practice, in fact, in which essential steps are performed to obtain a ‘good product’, from the most habitual such as cooking or speaking to the one such as designing a building, is free from a continuous adaptation to circumstances and a modulation according to them of the knowledge and skills possessed.

If man did not have this ability to adapt possessed knowledge to circumstances, referred to as ‘creative freedom’, and had to live exclusively by total adherence to executive procedures allocated to the frontal lobes, scientific progress, one of the most structured and design-oriented forms of human action, would most likely not have taken place.

However, improvisation has always been subject to a defect of interpretation: it is considered an activity without rules and references and assimilated to an action that does not require expertise, therefore totally unexpected and ‘surprising’. In this way it is contrasted with all those activities based on rigorous data analysis and scientific methodologies, which would seem to be the only ones that guarantee ‘authority’. But improvisational practice is certainly something much more definite than the simple description used in common mental representation.

Indeed, like other forms of complex cognition, improvisation involves a dynamic participation involving all regions of the cerebral cortex [

3]. As the American ethnomusicologist Berliner states

: ‘Popular definitions of improvisation that only emphasize its spontaneous and intuitive nature, characterizing it as “making something out of nothing”, are surprisingly incomplete. This simplistic understanding of improvisation belies the discipline and experience on which improvisers depend and obscures the actual practices and processes involved. Indeed, improvisation depends on thinkers absorbing a broad base of musical knowledge, including a myriad of conventions that help formulate ideas logically, convincingly and expressively. It is not surprising, therefore, that improvisers use language metaphors to discuss their art form. The same complex mix of elements and processes coexists for improvisers as for qualified language professionals; the learning, absorption, and use of linguistic conventions conspire in the writer’s mind and the use of linguistic conventions con- flow in the mind of the writer or speaker or, in the case of jazz improvisation, the musician to create a living work’ [

4].

In this sense, one can therefore understand how improvisational action is a common constituent of various practices that affect human action, and yet this value still seems to be misunderstood and delegated only to the domain of art, although not all creativity ends within this domain. Certainly, in a certain sense, artists are predisposed to and develop the skills necessary to enable creative mental states and thus may offer scientists an opportunity to study this faculty. But the capacity for creativity and improvisation should not be conceived as exclusive to this domain. In support of this idea, the philosopher Donald Schön has investigated the various technical professional practices that are characterized by a ‘

reflection in the course of action’ [

5], which occurs exclusively due to the uniqueness of the situation one finds oneself in. This situation, which cannot be framed within the usual interpretative categories, requires that the knowledge possessed must necessarily be remodeled and restructured into a new interpretative key, which will only be defined as effective when applied to the circumstance. Thus, if man wants to act in a competent manner, depending on the situation, he must necessarily call upon his capacity for creative improvisation, which enables him to make his possessed knowledge interact with the ‘

indeterminate zones of practice’ [

6].

1.1. The Elements of Musical Improvisation and Improvisation in Psychotherapy: An Integrative Study Hypothesis

Research on improvisation can inform basic cognitive neuroscience because it provides an original insight into how experience can shape brain structure and function [

7]. The field of music constitutes the field of choice for the development of this line of research.

The improvising musician undergoes a particular test: he or she manages many simultaneous processes in the here and now. These processes are generating and evaluating melodic and rhythmic sequences, coordinating performances with other musicians in a group and performing elaborate motor movements, all with a view to the goal of creating aesthetically interesting music [

8].

The question of the specific modalities through which musicians improvise and the knowledge of the brain regions that are activated during musical improvisations seems to be relevant not only to the discipline that studies the “psychology of music”, but also to shed light on the mental processes involved in psychotherapeutic practice.

Within it, in fact, it is possible to find the action of that mechanism of reorganization and adaptation of acquired knowledge to the experience that is occurring in the here and now of the therapeutic situation, a mechanism that is at the basis of every improvisational action [

9].

The critical review of the literature produced so far shows the use of neuroimaging methods to explore the cerebral basis of the improvisation mechanism and study its characteristics, exclusively in the field of music composition, using jazz pianists, classical musicians, freestyle rap performers and, as a group, freestyle rap performers as study samples. of freestyle rap and, as a control group, non-musicians.

These studies have distinctly shown how the improvisation mechanism is based on a series of continuous processes of evaluation and creation, involving the reworking of known materials in relation to unforeseen ideas, conceived, shaped and transformed by the specific conditions of the performance. These conditions contribute to making each creation unique. Furthermore, behavioral and neurophysiological research findings suggest that improvisation draws on general domain processes such as divergent thinking [

10] and cognitive flexibility.

2. Materials and Methods

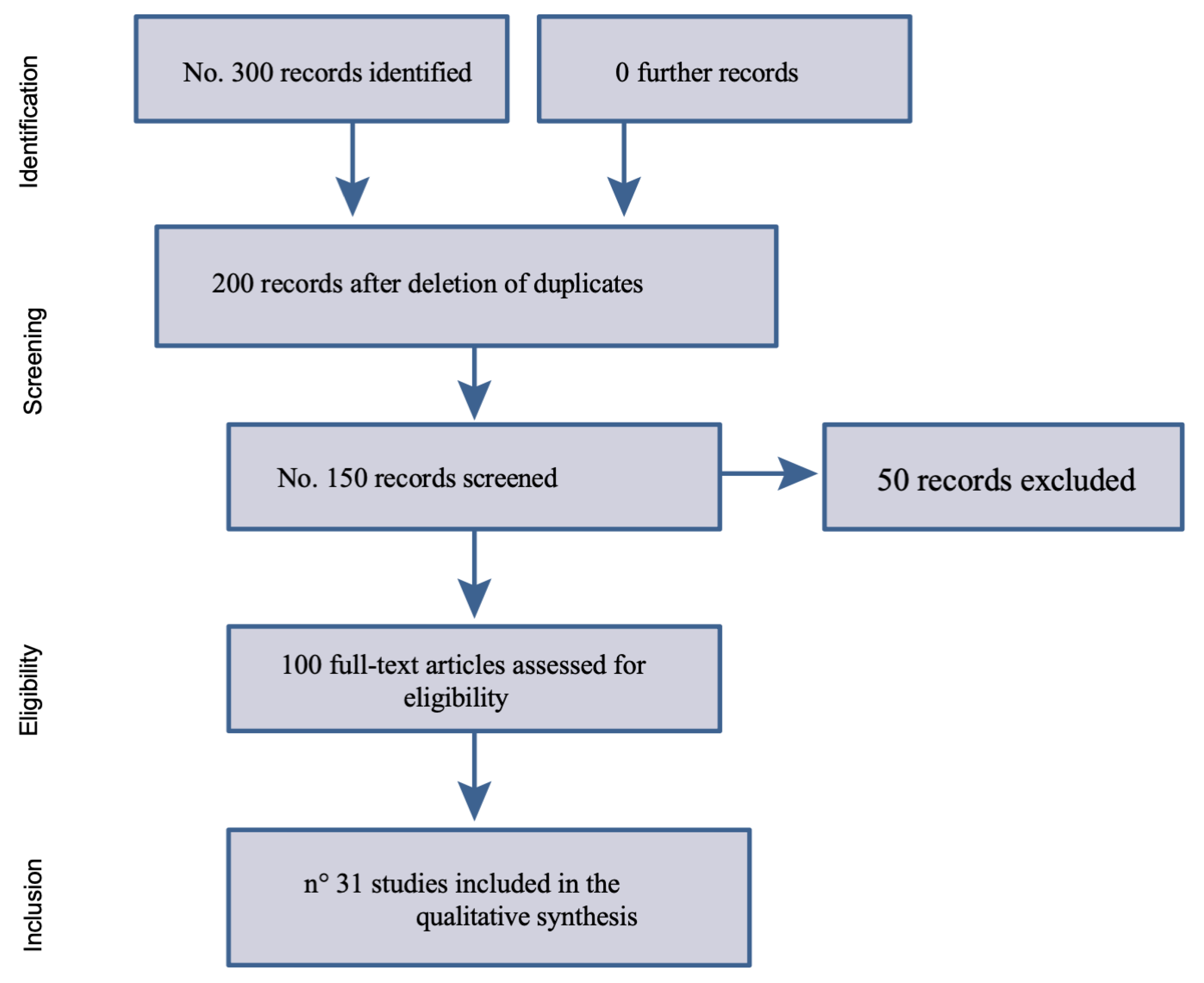

To systematically identify the most recent research conducted on this topic, a scoping review was conducted to identify missing elements and thus produce new hypotheses for investigation.

Scoping review is a methodology for synthesising the scientific literature produced on a topic or field where there is a lack of rigorous evidence, with the aim of quickly mapping the key concepts underlying that area of research. It is an optimal tool to identify the existence of a sample of literature on a given topic and provide an overview (broad or detailed) of its focus; it is useful for examining emerging evidence when it is not yet clear what more specific questions can be asked and addressed by a systematic review [

11].

The model used in this review is the one offered by the PRISMA framework [

12], in the extension elaborated for scoping reviews (PRISMA- ScR) published in 2019; this model provides 20 criteria (plus two optional ones) that the researcher is asked to answer to identify their work within the Scoping Reviews category.

The question that guided this review was to investigate whether equivalent research had also been carried out in the field of psychotherapy about the neurophysiological correlates of creative improvisation through neuroimaging methods. This investigation started from the study hypothesis that similar mental processes to those affecting the improvising musician occur in psychotherapeutic practice, which would therefore appeal to the activation in the mind of the practitioner in the here and now of his work of the same brain areas that are activated in the mind of the improvising musician.

The study assumption starts from the consideration of one aspect, among many, that musicians and psychotherapists have in common: the ability to listen with participation and attunement [

13,

14]. Just as musical production can be defined, in accordance with Gestalt principles, as a moment of intensified presence in the here and now [

15], the work of the psychotherapist involves an experimentation of interaction with the client on multiple levels [

16], which go far beyond the aspect of content: melody, sound, tone, consonance and dissonance, accompaniment, rhythm and tempo are the elements underlying his action.

As Yalom puts it: ‘In its essence, the flow of therapy should be spontaneous, always following an unexpected course; it is grotesquely distorted if it is packaged in a formula that allows inexperienced and inadequately trained therapists to provide uniform therapy [

17]’.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria for Selected Articles

To answer the research question of the present scoping review, those articles were included that described research carried out using neuroimaging methods and that had as their topic the analysis of the process of musical improvisation and creativity, from the perspective of its neuropsychological correlates. These studies were then further selected by choosing those that focused on jazz improvisation.

A similar discrimination process was carried out to highlight the existence of similar research in the field of psychotherapy, pertaining to the study of the neuropsychological correlates of the improvisation process introduced by the psychotherapist during the psychotherapy session.

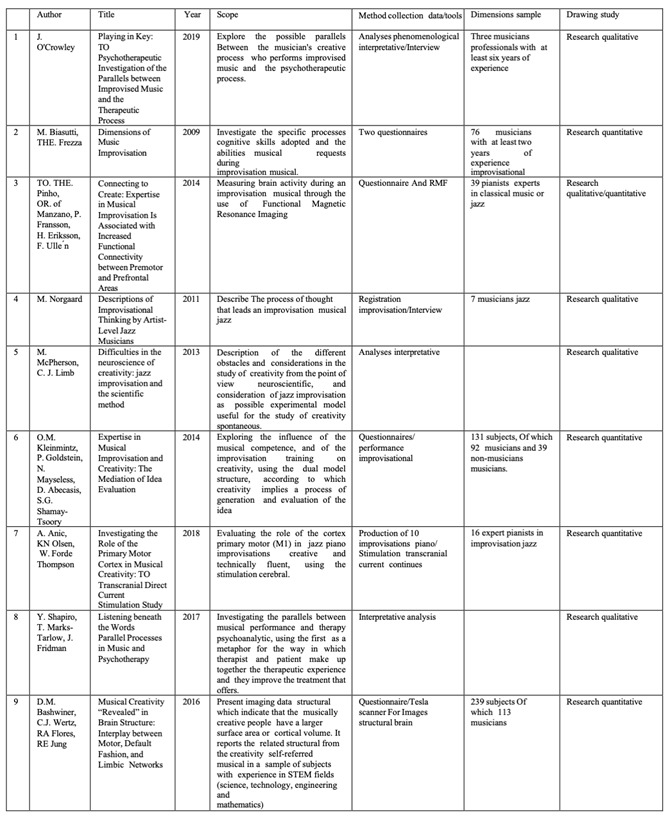

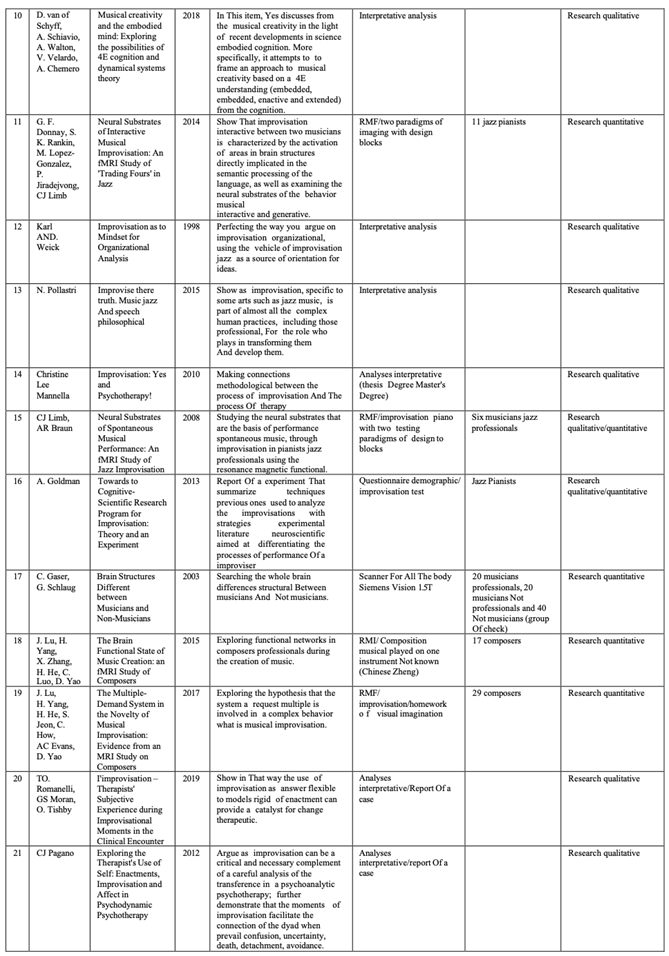

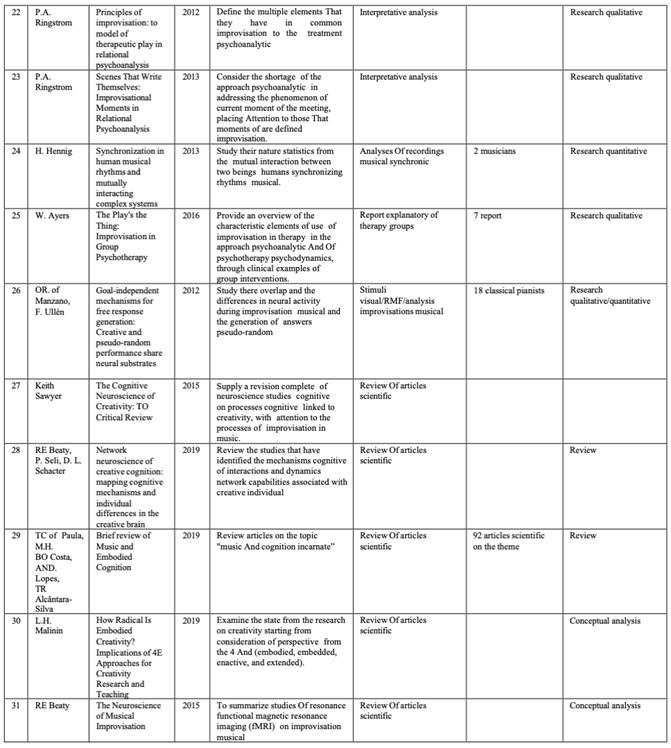

The main sources of information for the research were taken from four electronic databases: Google Scholar, PubMed, PsycInfo, Scopus, from which articles were selected with a publication date from the year 2009 onwards, using words such as: musical improvisation, neuropsychological correlates, psychotherapy, creativity, improvisation process in psychotherapy as search keys (

Table 1).

The language of the selected articles was predominantly English, although there were also examples of articles written in Italian.

A total of 31 articles were identified as suitable for the purposes of the review using the key words, some of which (no. 5) were already significant reviews in themselves; a much larger number (approx. 300), following a reading of the abstracts, did not meet the inclusion criteria, as they dealt with the topic of improvisation exclusively in areas such as dance and/or theatrical performance or, in the case of the analysis of the topic in psychotherapy, did not take the psychotherapist’s mental process as the point of observation. (

Table 2), (

Figure 1)

The characteristics of the selected studies were summarized in schematic information in

Table 3, concerning the author, title, year of publication, purpose, method of data collection and instruments used, sample size and study design. The study population consisted mainly of experienced musicians, performers specialized in classical music and/or jazz improvisation.

3. Results

As can be deduced from an analysis of the literature produced to date, a rather large number of studies have employed neuroimaging methods to explore the brain basis of spontaneous musical composition. Much of the research has focused on understanding the involvement of different brain regions associated with executive control mechanisms in improvised behaviour.

This section will summarize the results of this analysis, which aim to highlight the elements characterizing the improvisation process.

In most of the selected studies, it became clear that musical improvisation involves the activation of extensive brain regions (see

Table 3, Nos. 2, 3, 7, 11, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19). The frontal and premotor regions, e.g., the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), the parietal association areas, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the supplementary motor areas (SMA) and pre-supplementary motor areas (pre-SMA), as well as the lateral premotor regions, are important for the generation of musical structures from scratch [

18].

An intense activation in Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area, two regions belonging to the perisylvian circuit that defines itself as the neural substrate of language, was highlighted; the homologues of the right hemisphere of both these areas were also activated. Improvisation has also been associated with a strong bilateral deactivation of the angular gyrus, an area identified as a cross-modal centre for semantic integration in numerical, linguistic and problem-solving processing [

19]. It is clear, therefore, that improvised musical communication, as opposed to performance based on memorized music, can lead to an intense involvement of the cortical areas of the left hemisphere classification associated with language, as well as their counterparts in the right hemisphere. These results provide concrete suggestions with respect to the neural overlap between music and language processing and support the idea that these systems are partly based on a common network of prefrontal and temporal cortical processing areas [

20]. Indeed, the thought process underlying improvisation in jazz has been likened to the thought process that elicits spoken language, due to the commonality between them: production in the here and now of performance [

21,

22,

23]. Just as the linguistic product goes through various stages, in which an idea is planned, translated into a linguistic structure, performed and finally evaluated through monitoring [

24], in the same way in improvisation it is possible to conceptualize a musical goal, formulate it with reference to tonality and melody, plan and realize the motor plan and finally evaluate the result [

25].

Activation in the pre-supplementary motor area (pre-SMA) and in the dorsal premotor cortex (PDM), brain circuits that play a fundamental role in many cognitive aspects of movement, in that basic human capacity to freely generate and organize movement sequences to achieve higher order goals, was also found [

26].

Specifically, activity in the pre-SMA correlates with rhythmic improvisation but also increases in melodic improvisation, whereas PDM activation was present in melodic improvisation but not in rhythmic improvisation. However, both regions are active to some extent in the improvisational conditions. Ultimately, while free generation of spatial or temporal sequences is only associated with subtle modulations in the activity level of pre-SMA and PMD, creative musical improvisation of melody and rhythm appears to be a largely integrated process. In this regard, studies (in Tab 3. no. 1, 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 27, 28) focusing on the analysis of the creative process to identify structural correlates of creativity were considered. Examination of the literature led to the identification of the existence of a complex neuronal network that deter- mines many of the cognitive processes essential for creative thinking; these include, among others, goal-dependent memory retrieval (executive default) [

27], inhibition of the predominant response (executive default; [

28]) and internally focused attention (executive-visual) [

29].

The neuronal circuits and brain areas involved in musical improvisation, therefore, produce the five constituent dimensions of the activity, namely: anticipation, emotional communication, flow, feedback, use of the repertoire [

30].

The anticipation dimension refers to the ability to anticipate the objects, characteristics and set of processes corresponding to the musical clusters to be played. It is eminently related to individual aspects and requires the ability to plan the improvisation and to have an overall idea of the entire solo [

31]. It is also characterized as a rational and conscious activity: it implies a cognitive effort that enables the improviser to find very complex solutions.

The emotional communication dimension refers to the ability to communicate emotions through musical performance which can induce, convey and represent emotional states through all three constituent elements of music, namely rhythm, melody and harmony. The listener’s emotional reactions influence the performer’s emotional expression through the feedback provided: therefore, the improviser will modify his or her performance based on the feedback received.

The flow factor refers to a state of mind that brings together cognitive, physiological and affective elements, linked to the concept of optimal experience. When improvisers experience a state of flow, they only concentrate on what they are performing by focusing on the here and now of the creative moment and overcoming their own cognitive limitations.

The feedback factor refers to the ‘process by which an environment returns to individuals some of the information, in their response output, needed to compare their current strategy with a representation of an ideal strategy’ [

32]. Environmental feedback - i.e., the reactions that the environment sends back with respect to a behavior - provides that information that enables individuals to confront their current strategy with internal representations and enables a process of creative adaptation with response restructuring [

33]. This element is configured to be essential in every human activity/performance, not exclusively in the musical one.

Finally, the use of the repertoire factor refers to the pre-composed formulas or clichés used during the improvisation, assimilated from previous listening to other musicians and often modified by the performer in the here and now of the ongoing improvisation. Many times, the improvising musician draws on a set of formulas or clichés he has constructed himself, and the choice of the particular musical pattern to be used at a given moment depends on the general idea he intends to reproduce or the direction in which he intends his improvisation to move.

It is therefore clear that improvisation involves many areas of the cerebral cortex in a dynamic communication, calling into play general processes such as divergent thinking and cognitive flexibility: it is therefore a structured activity requiring specific skills. It is therefore conceivable as a multidimensional concept, which includes technical, expressive and social elements, and a structured activity, which requires several specific skills.

3.1. Discussion and Developments

Seen in this way, we find that creative improvisation can be understood as a characterizing part of psychotherapy, in which all the elements examined are reflected.

As Bradford Keeney has illustrated, ‘given the unpredictable nature of a client’s communication, the therapist’s participation in theatrical performances of a session becomes an invitation to improvisation. In other words, since the therapist never knows exactly what the client will say at any given moment, he or she cannot rely solely on previously designed lines, patterns, or scripts... (.....) each particular expression in a session offers a unique opportunity for improvation, invention,innovation, or, more simply, change’ [

34].

It becomes clear how people ‘compose’ each session using the art of creative improvisation that implies, as we have seen, the recombination of familiar materials into new forms, in ways that are sensitive to context, interaction and response [

35]. Roles are not established; scripts are not defined; time and space are indeterminate. Acts begin from the unknown, draw from the unknown and develop from the unknown in an environment and in a relationship [

27]. Psychotherapy in this way appears as a situated creative process, within which the therapist and patient co-construct the context of the experience, which transforms and evolves over the course of the session. In this sense, creative improvisation becomes a means through which all dimensions of the therapeutic work emerge more deeply and intensely [

36].

The use of creative improvisation becomes a means by which all dimensions of psychotherapeutic work are realized more deeply and vividly.

It is beyond any doubt that when therapist and patient resonate with the “relational melody”, they experience a very deep bodily-emotional contact: they act in an “interbody” relationship that supports the patient’s self-discovery [

37], modifying the pathways of his internal representations. In this framework, psychotherapy presents itself as a synergetic duet, between two systems, producing change through shared bodily resonance, in the same way as in musical improvisations. Therapy thus becomes conceivable as a process of synchronizing relational melodies, a relational improvisation that is attuned to dyadic evolution, in verbal and non-verbal domains, and that amalgamates art with objective, subjective and intersubjective science.

The parallelism between therapeutic and musical process rests on the underlying factor of both creative endeavors, which is embodied in the emerging non-linear dynamics: each relational encounter becomes a unique interpretation, which transforms both the performer and the listener.

The use in psychotherapy of the musical model of relational transactions, based on the improvisational process, stimulates therapists of all orientations to pay attention to the flow of the process by listening beyond words and to tune into the experiential space by paying attention to the intersubjective dimensions of interaction. The associative-emotional focus that develops in playing (or listening to) music transposed into the therapeutic process allows for a deeper resonance with the patient, highlights mutual synchronizations, convergent and divergent contents, ruptures and relational attachments.

Ultimately, both performer and therapist enable the development of a pure reactivity in the here and now of each encounter.

The searches in the different databases consulted did not reveal a significant number of studies investigating the neuronal processes on which the elaboration of therapeutic thinking based on the typical mechanisms of improvisation is based. The methodological resonance between the two fields does not yet seem to have been investigated from the point of view of its neuroscientific basis based on improvisational behavior explained according to the criteria listed above.

In fact, the material found referred mainly to qualitative research based on interpretative analyses restricted to the psychoanalytic/psychodynamic field (in

Table 3 no. 8, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25).

This seems to introduce a knowledge gap as to how (how) improvisation is experienced in therapy, what the subjective experience of the therapist and client is in the improvised moments, and finally, how and why that experience leads to changes in the therapeutic process. Furthermore, it raises interesting questions about the possibility of the therapist remaining detached from the process or immerses himself totally in it, whether he seeks an objective meaning of the therapeutic story, or loses himself in the subjective and intersubjective vicissitudes of the here and now of the story and the session.

Only in one of the selected articles (in

Table 3 No. 14) was an explicit attempt made to establish the methodological connections existing between the therapeutic process and the improvisation process, pointing out that in the therapeutic encounter, as well as in improvisation, it is evident that “the whole is more than the sum of its parts”, therefore what is produced and experienced is certainly more than what each person consciously offers. And it is precisely the creative and improvisational ability of the therapist that gives him/her the possibility to understand this totality beyond the limits that normal verbal communication imposes, enabling him/her to grasp richer and more significant aspects of information. It should not be forgotten that the most important part of the information processing is carried out by the subcortical networks, in which simultaneous readings of physiological environments, emotional/affective valences and changes in the contexts and ourselves in relation to them are determined. The model of mutual resonance in relational approaches to psychotherapy emphasizes the mind/body tuning between the somatic, affective and cognitive systems of the patient and therapist. But whereas attuned listening and responding aim to achieve interpersonal harmony, attunement is to be thought of in the context of interaction whereby a patient and therapist become partners in a relational duet, striving for a more harmonious and coherent relational movement, starting from a point where the patient’s relational melody is interspersed with frequent dissonances that he or she is unable to integrate into his or her experience.

The rhythm of relational flow goes back and forth, expressions are often punctuated by silences, the synchronized rhythms of affective response unique to each dyad and moment to moment. This is the essence of psychotherapy as relational improvisation.

Therefore, future research development could focus on the use of a study approach in psychotherapy like that used in the field of musical improvisation, to more accurately determine the cognitive processes underlying therapeutic improvisation. The proposed study of the neurological correlates of the improvisation process in psychotherapy could be developed using Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS), a non-invasive functional neuroimaging technique that employs scattered light in the near-infrared spectral band to investigate the haemodynamic activity of the cerebral cortex and the associated functional capacity [

38]. Similarly to other functional neuroimaging techniques, the physiological principle that allows measured haemodynamic activity to be correlated with individual functional capacities refers to the phenomenon of neurovascular coupling. This principle states that a neural activity relative to a specific brain area, which refers to a functional response of the subject to a stimulus, causes a local increase in oxygen consumption and a consequent change in blood flow. This metabolic process results in a local increase in the supply of oxygenated haemoglobin and a corresponding decrease in deoxygenated haemoglobin in the brain area assigned to a specific task.

Although the relationship between neuronal and vascular activity in the brain is not yet fully understood, experiments have shown that they are directly proportional: an increase in blood flow, resulting in an increase in local oxygenation, is followed by an increase in neuronal activitỳ. Thus, by detecting local variations in blood flow and oxygenation, the presence or absence of brain activity and its localization can be deduced, from which important information can be deduced, e.g., on the process of attention, memory, planning and reasoning.

4. Conclusions

The idea behind this scoping review was to investigate the existence of studies and research that would validate the hypothesis that the neuronal mechanisms underlying the psychotherapist’s actions may be common to those activated in the mind of the performer who improvises music. Here, neu- roimaging methods have in fact revealed specific processes in the domain of improvisational cognition and that the experience of being musically creative is correlated with increased cortical surface area or volume in domain-general creative ideation regions, domain-specific regions frequently recruited for musical tasks, and emotion-affiliated regions. This results in the activation of cognitive functions such as attention, perception, language, memory and intellectual reasoning, functions that are at play in the psychotherapist’s mind during the encounter.

Thus, to conclude, if the neuroscience of musical improvisation may have implications in better understanding the mechanisms that allow for the reorganisation of circuits underlying high order functions such as semantics and creativity, the neuroscience of improvisation in therapy may provide important insights to help understand how and in what way it represents an effective therapeutic modality of interaction due to the fact that it configures a change in the therapist’s way of being, which in parallel triggers a change in the patient. This is because a patient and a therapist are partners in a relational duet, working together to create a harmonious and coherent relational flow from a point where the patient’s relational melody is characterized by multiple dissonances that are not integrated into his or her experience of reality [

39].

Both psychotherapy and musical performances constitute creative enterprises involving new perceptions, integrated cognitive-emotional processing and contextual re-presentations.

Frequently, creative improvisation is embodied in actions that therapists enact without giving them this specific label, when they encounter moments in which the usual ways of interacting fail when they encounter moments in which the usual ways of interacting fail: it is in these moments that something new happens, in which the therapist is at the same time conductor, accompanist, co-creator and listener of the composition in action.

Analyzing the mechanisms that substantiate this capacity for improvisation, parallel to that of the patient, would allow the measure of the therapist’s creative capacity and the measure of his efficacy in interpersonal play to emerge [

40].

Brahms stated that, if truly inspired, a ‘finished product’ was often ‘revealed’ to him ‘bar after bar’. He argued the necessity of being ‘in a condition of semi-trance to achieve such results, a condition in which the conscious mind is temporarily in abeyance and the subconscious mind is in control, for it is through the subconscious mind ... that inspiration comes. [

41].