Submitted:

25 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

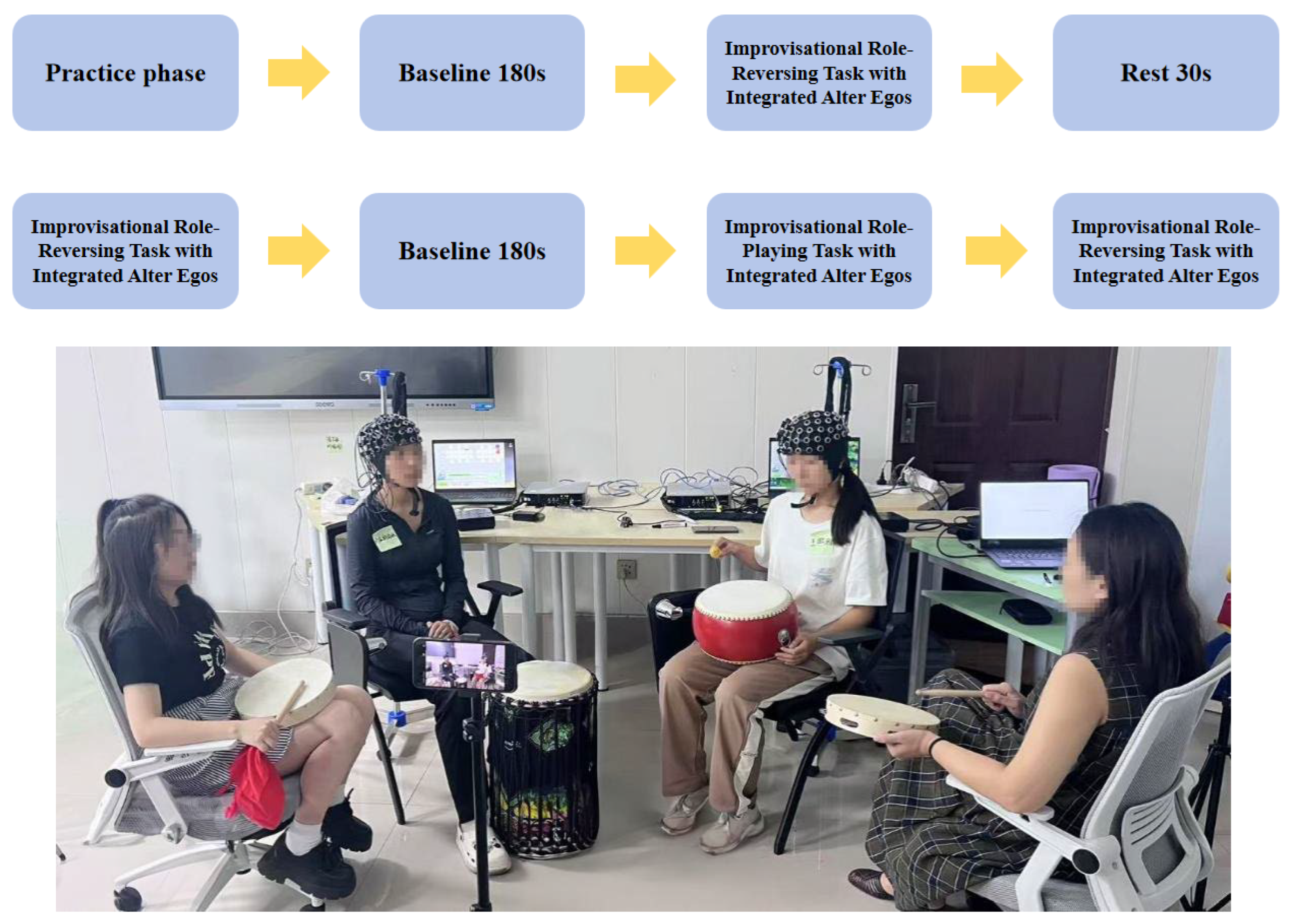

2.2. Experimental Tasks and Procedure

| Channels | MNI x | MNI y | MNI z | Brodmann’s Area | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH01 | 12 | 59 | 40 | 9 – Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | 0.82731 |

| CH02 | 13 | 73 | 15 | 10 – Frontopolar area | 1 |

| CH03 | 42 | 29 | 50 | 8 – Includes Frontal eye fields | 0.93886 |

| CH04 | 20 | 46 | 50 | 8 – Includes Frontal eye fields | 0.91266 |

| CH05 | 24 | 65 | 26 | 10 – Frontopolar area | 0.92015 |

| CH06 | 28 | 69 | 10 | 10 – Frontopolar area | 1 |

| CH07 | 52 | 28 | 39 | 9 – Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | 0.67993 |

| CH08 | 34 | 49 | 39 | 9 – Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | 0.891 |

| CH09 | 37 | 65 | 10 | 10 – Frontopolar area | 1 |

| CH10 | 45 | 49 | 15 | 10 – Frontopolar area | 0.53648 |

| CH11 | 64 | -64 | 6 | 6 – Pre-Motor and Supplementary Motor Cortex | 0.97193 |

| CH12 | 66 | 8 | 19 | 6 – Pre-Motor and Supplementary Motor Cortex | 0.45307 |

| CH13 | 70 | -35 | 19 | 40 – Supramarginal gyrus part of Wernicke’s area | 0.9125 |

| CH14 | 65 | -29 | 50 | 40 – Supramarginal gyrus part of Wernicke’s area | 0.45353 |

| CH15 | 69 | -9 | 31 | 6 – Pre-Motor and Supplementary Motor Cortex | 0.61489 |

| CH16 | 71 | -10 | 0 | 21 – Middle Temporal gyrus | 0.55882 |

| CH17 | 69 | -49 | 13 | 22 – Superior Temporal gyrus | 0.82026 |

| CH18 | 61 | -38 | 40 | 40 – Supramarginal gyrus part of Wernicke’s area | 0.65116 |

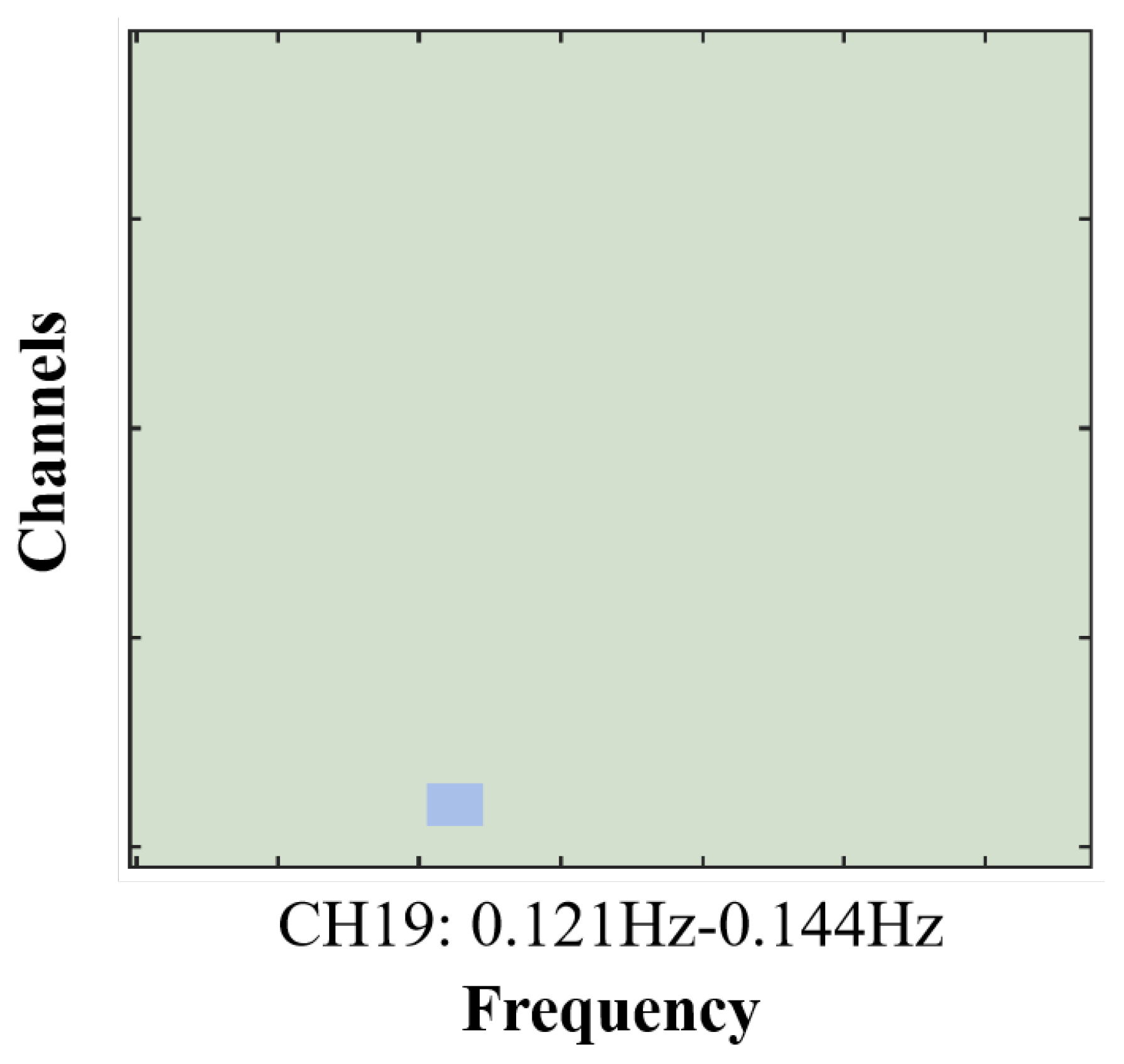

| CH19 | 72 | -22 | 42 | 42 – Primary and Auditory Association Cortex | 0.63125 |

| CH20 | 73 | -35 | 21 | 21 – Middle Temporal gyrus | 0.59621 |

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Behavioral Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Results

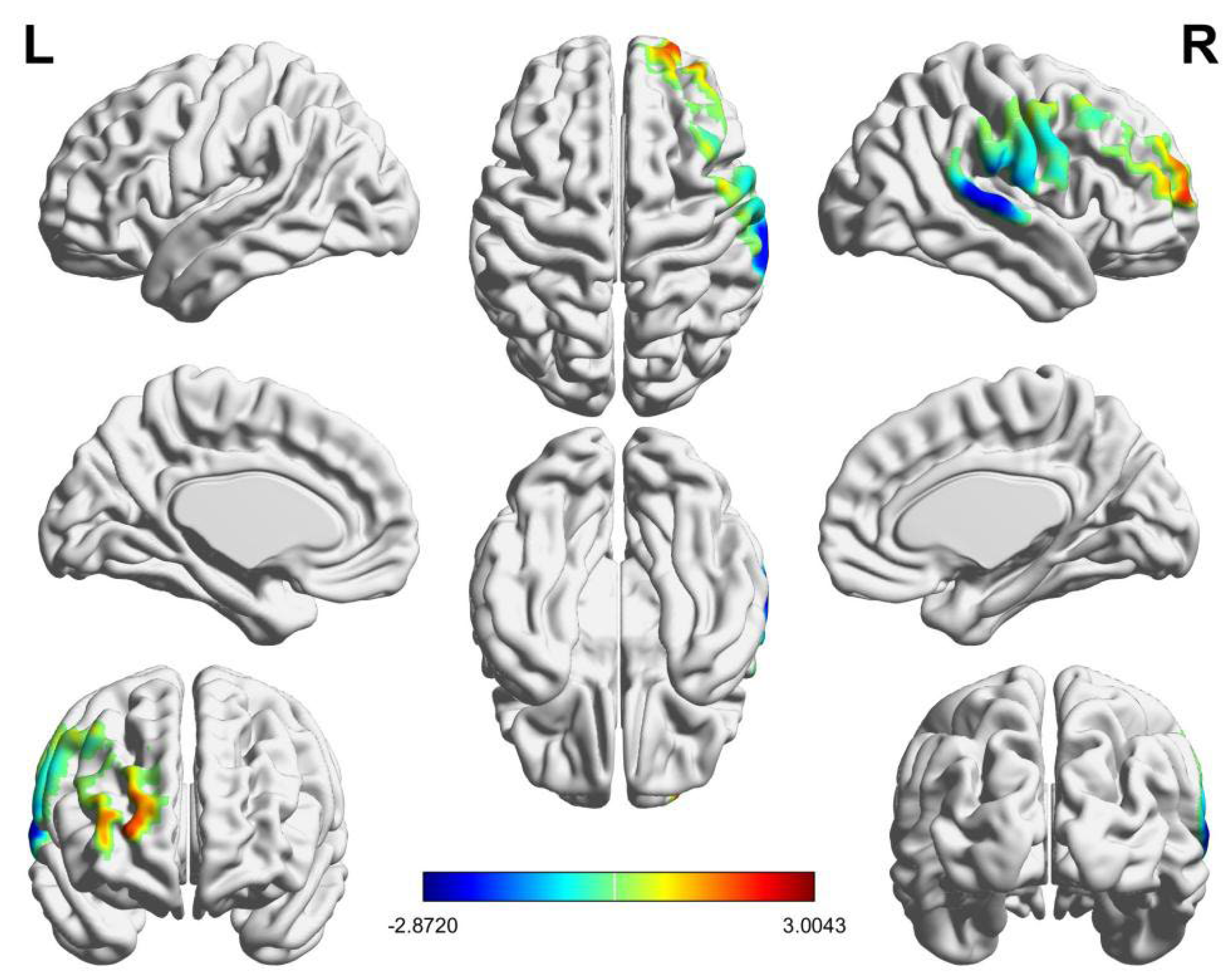

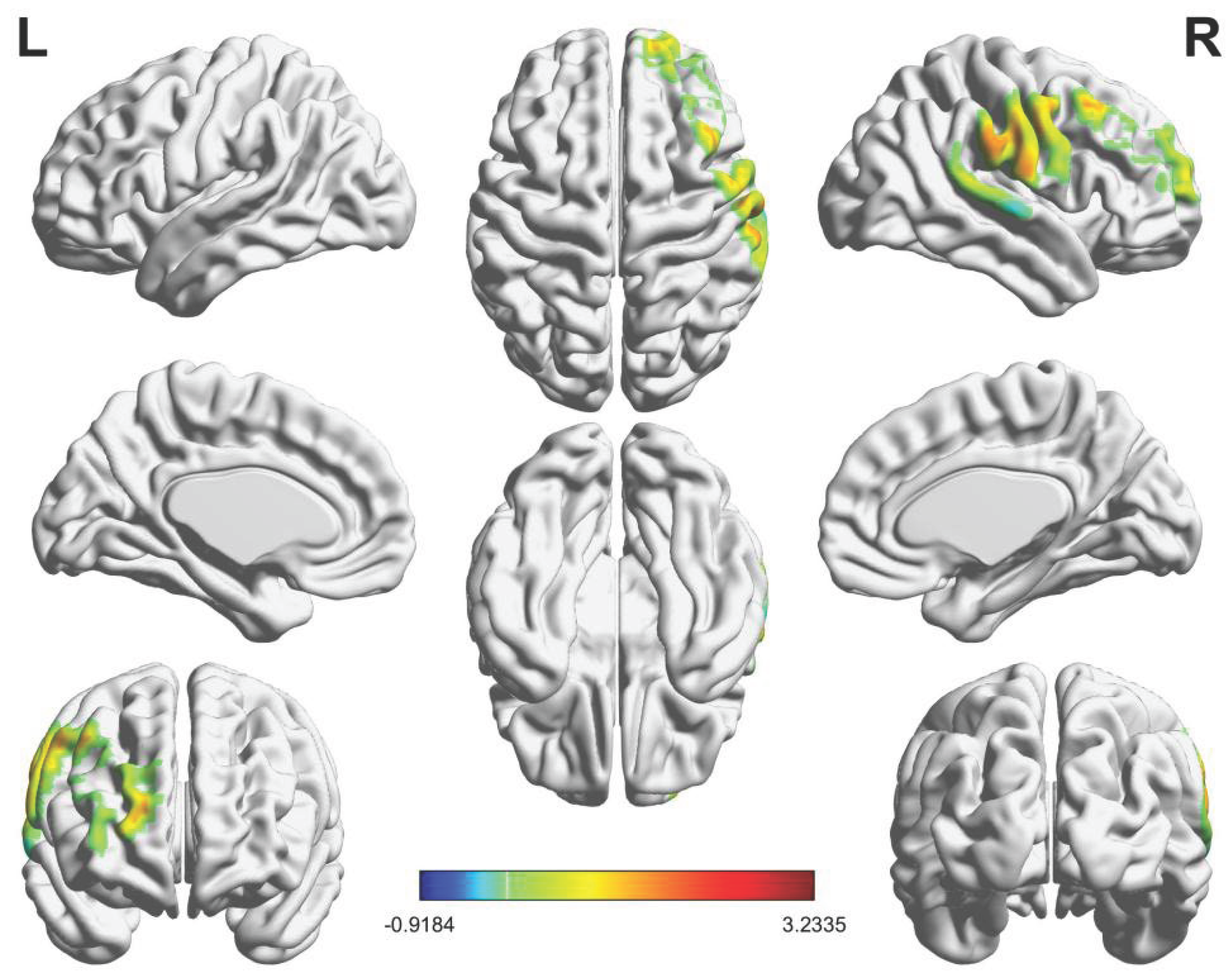

3.2. Intra-Brain Activation Results

3.3. Inter-Brain Synchrony Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sang, Z. Q.; Huang, H. M.; Benko, A.; Wu, Y. The spread and development of psychodrama in mainland China. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, H.; Skolnik, S. Periphery to core: scenes from a psychodrama. Soc. Work Groups 2024, 47, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.; Sales, C. M.; Alves, P.; Moita, G. The core techniques of Morenian psychodrama: A systematic review of literature. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicciari, A.; Rossi, F.; Iero, L.; Di Pietro, E.; Verrotti, A.; Franzoni, E. Drama therapy and eating disorders: a historical perspective and an overview of a Bolognese project for adolescents. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2013, 19, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somov, P. G. A psychodrama group for substance use relapse prevention training. Arts Psychother. 2008, 35, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ding, F.; Chen, D.; Zhang, X.; Shen, K.; Fan, Y.; Li, L. Intervention effect of psychodrama on depression and anxiety: A meta-analysis based on Chinese samples. Arts Psychother. 2020, 69, 101661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatner, A. Psychodrama: The state of the art. Arts Psychother. 1997, 24, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J. J. Acting Your Inner Music: Music Therapy and Psychodrama; MMB Music: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, J. J. Musical psychodrama: A new direction in music therapy. J. Music Ther. 1980, 17, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, V.; Lindenberger, U. Dynamic orchestration of brains and instruments during free guitar improvisation. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Ni, J.; De Dreu, C. K.; Ma, Y. Leader–follower behavioural coordination and neural synchronization during intergroup conflict. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 2169–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Bryant, D.M.; Reiss, A.L. NIRS-based hyperscanning reveals increased interpersonal coherence in superior frontal cortex during cooperation. Neuroimage 2012, 59, 2430–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Cui, H.; Huang, B.; Huang, Y.; Sun, H.; Ru, X.; Zhang, M.; Chen, W. Interbrain neural mechanism and influencing factors underlying different cooperative behaviors: a hyperscanning study. Brain Struct. Funct. 2023, 229, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montague, P.R.; Berns, G.S.; Cohen, J.D.; McClure, S.M.; Pagnoni, G.; Dhamala, M.; Fisher, R.E. Hyperscanning: simultaneous fMRI during linked social interactions. Neuroimage 2002, 16, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Liu, T.; He, L.; Li, Y. Micro-foundations of strategic decision-making in family business organisations: a cognitive neuroscience perspective. Long Range Plan 2023, 56, 102198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, U.; De Felice, S.; Pinti, P.; Zhang, X.; Noah, J.; Ono, Y.; Burgess, P.W.; Hamilton, A.; Hirsch, J.; Tachtsidis, I. Quantification of inter-brain coupling: a review of current methods used in haemodynamic and electrophysiological hyperscanning studies. NeuroImage 2023, 280, 120354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, J. J. Musical psychodrama in Naples. Arts Psychother. 1991, 18, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J. J. Musical psychodrama in Paris. Music Ther. Perspect. 1984, 1, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.; Carollo, A.; Bizzego, A.; Chen, S. A.; Esposito, G. Decreased activation in left prefrontal cortex during role-play: an fNIRS study of the psychodrama sociocognitive model. Arts Psychother. 2024, 87, 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fávero, M.; Sousa, R.; Budal-Oliveira, L.; Sousa-Gomes, V. Psychodrama: Comprehensive review of the effectiveness of psychodrama in sexual abuse trauma. Eur. Psychol. 2024, 29, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipper, D.; Ritchie, T. The effectiveness of psychodramatic techniques: A metaanalysis. Group Dyn.: Theory Res. Pract. 2003, 7, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.; Sales, C. M.; Alves, P.; Moita, G. The core techniques of Morenian psychodrama: A systematic review of literature. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behav. Brain Sci. 2013, 36, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kube, T.; Schwarting, R.; Rozenkrantz, L.; Glombiewski, J. A.; Rief, W. Distorted cognitive processes in major depression: A predictive processing perspective. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 87, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamin, J. A. Habitually breaking habits: Agency, awareness, and decision-making in musical improvisation. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2024, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutti, M.; Frezza, L. Dimensions of music improvisation. Creat. Res. J. 2009, 21, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, K. C.; Barrett, F. S.; Jiradejvong, P.; Rankin, S. K.; Landau, A. T.; Limb, C. J. Classical creativity: A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) investigation of pianist and improviser Gabriela Montero. NeuroImage 2020, 209, 116496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, K. C.; Jiradejvong, P.; Jacobs, L.; and Limb, C. J. Children engage neural reward structures for creative musical improvisation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz Abrahan, V.; Bossio, M.; Benítez, M.; Justel, N. Musical strategies to improve children’s memory in an educational context. Psychol. Music 2022, 50, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, R. A.; Wilson, G. B. Musical improvisation and health: a review. Psychol. Well-Being 2014, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeditehrani, H.; Dijk, C.; Toghchi, M. S.; Arntz, A. Integrating cognitive behavioral group therapy and psychodrama for social anxiety disorder: An intervention description and an uncontrolled pilot trial. Clin. Psychol. Eur. 2020, 2, e2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raglio, A.; Oasi, O.; Gianotti, M.; Rossi, A.; Goulene, K.; Stramba-Badiale, M. Improvement of spontaneous language in stroke patients with chronic aphasia treated with music therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Neurosci. 2016, 126, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipper, D. A. The cognitive double: Integrating cognitive and action techniques.J. Group Psychother. Psychodrama Sociom. 2002, 55, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaniv, D. Revisiting Morenian psychodramatic encounter in light of contemporary neuroscience: Relationship between empathy and creativity. Arts Psychother. 2011, 38, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, D. L.; Jenkins, A. C.; Banaji, M. R.; Mitchell, J. P. Taking another person’s perspective increases self-referential neural processing. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 642–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majdandžić, J.; Amashaufer, S.; Hummer, A.; Windischberger, C. , and Lamm, C. The selfless mind: How prefrontal involvement in mentalizing with similar and dissimilar others shapes empathy and prosocial behavior. Cognition 2016, 157, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Pellegrino, G.; Fadiga, L.; Fogassi, L.; Gallese, V.; Rizzolatti, G. Understanding motor events: a neurophysiological study. Exp. Brain Res. 1992, 91, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penagos-Corzo, J. C.; Cosio van-Hasselt, M.; Escobar, D.; Vázquez-Roque, R. A.; Flores, G. Mirror neurons and empathy-related regions in psychopathy: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and a working model. Soc. Neurosci. 2022, 17, 462–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaty, R. E. The neuroscience of musical improvisation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 51, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Iversen, J.; Callan, D. E. Music improvisation is characterized by increase EEG spectral power in prefrontal and perceptual motor cortical sources and can be reliably classified from non-improvisatory performance. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, C.; Duan, L.; Gong, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhu, C. NIRS-KIT: a MATLAB toolbox for both resting-state and task fNIRS data analysis. Neurophotonics 2021, 8, 010802–010802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Schleihauf, H.; Kayhan, E.; Matthes, D.; Vrtička, P.; Hoehl, S. The effects of interaction quality on neural synchrony during mother-child problem solving. Cortex 2020, 124, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, K.; Yu, T.; Hao, N. Creating while taking turns, the choice to unlocking group creative potential. NeuroImage 2020, 219, Article–117025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Bray, S.; Reiss, A. L. Functional near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) signal improvement based on negative correlation between oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin dynamics. Neuroimage 2010, 49, 3039–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emberson, L. L.; Crosswhite, S. L.; Goodwin, J. R.; Berger, A. J.; Aslin, R. N. Isolating the effects of surface vasculature in infant neuroimaging using short-distance optical channels: a combination of local and global effects. Neurophotonics 2016, 3, 031406–031406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Bao, M.; Xuan, B. Neural mechanisms distinguishing two types of cooperative problem-solving approaches: An fNIRS hyperscanning study. NeuroImage 2024, 291, 120587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Y.; You, H. L.; Song, C. L.; Zhou, L.; Wang, S. Y.; Li, X. L.; ... Zhang, B. W. Shared and distinct prefrontal cortex alterations of implicit emotion regulation in depression and anxiety: An fNIRS investigation. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 354, 126–135. [CrossRef]

- Grinsted, A.; Moore, J. C.; Jevrejeva, S. Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series. Nonlin. Process. Geophys. 2004, 11, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Xuan, B.; Liu, C.; Yi, J.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, M. The influence of task and interpersonal interdependence on cooperative behavior and its neural mechanisms. npj Sci. Learn. 2025, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozawa, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Sakaki, K.; Yokoyama, R.; Kawashima, R. Interpersonal frontopolar neural synchronization in group communication: an exploration toward fNIRS hyperscanning of natural interactions. Neuroimage 2016, 133, 484–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonzo, G. A.; Goodkind, M. S.; Oathes, D. J.; Zaiko, Y. V.; Harvey, M.; Peng, K. K.; ... Etkin, A. Selective effects of psychotherapy on frontopolar cortical function in PTSD. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 1175–1184. [CrossRef]

- Macuga, K. L.; Frey, S. H. Selective responses in right inferior frontal and supramarginal gyri differentiate between observed movements of oneself vs. another. Neuropsychologia 2011, 49, 1202–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccino, G.; Solodkin, A.; Small, S. L Functions of the mirror neuron system: implications for neurorehabilitation. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 2006, 19, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidanagamage, S. D.; Bhaumik, A. O.; Irugalbandara, A. I. Role reversal in psychodrama: Enhancing empathy and emotional understanding among institutionalized children in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2024, 8, 1550–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usluoglu, F. The effects of psychodrama on relationship between the self and others: a case study. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 30863–30877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R. Free improvisation and performance anxiety among piano students. Psychol. Music 2013, 41, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachner, J.; Gold, C.; Erkkilä, J. Music therapy modulates fronto-temporal activity in rest-EEG in depressed clients. Brain Topogr. 2013, 26, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinigaglia, C.; Rizzolatti, G. Through the looking glass: self and others. Conscious. Cogn. 2011, 20, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhani, S.; Marsh, A. A.; Pine, D. S.; Blair, R. J. R. Neural correlates of response reversal: considering acquisition. Neuroimage 2007, 34, 1754–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kringelbach, M. L.; Rolls, E. T. Neural correlates of rapid reversal learning in a simple model of human social interaction. Neuroimage 2003, 20, 1371–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Wang, J.; Luo, R.; Hao, N. Brain to brain musical interaction: A systematic review of neural synchrony in musical activities. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 164, 105812.53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).