Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

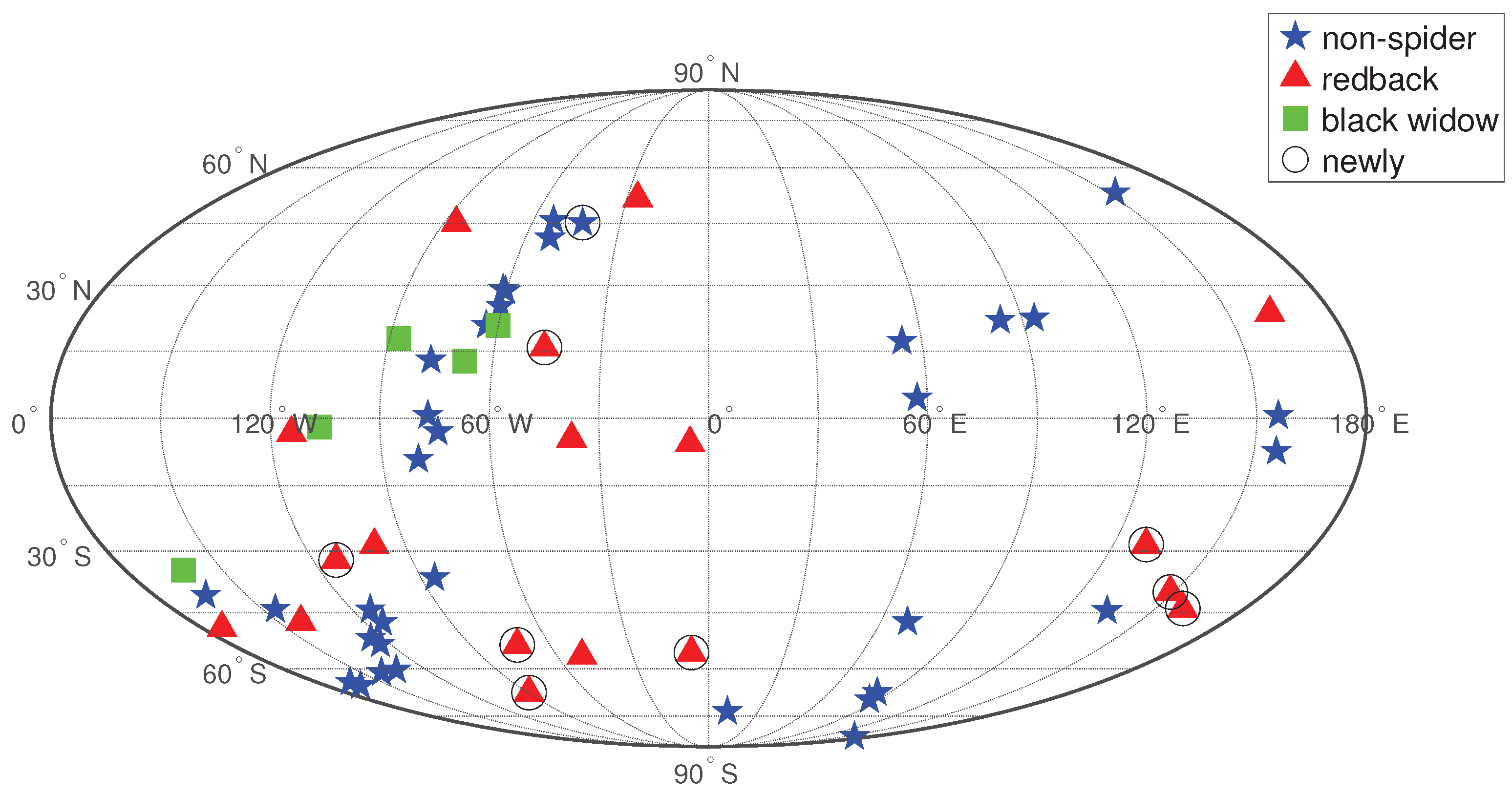

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

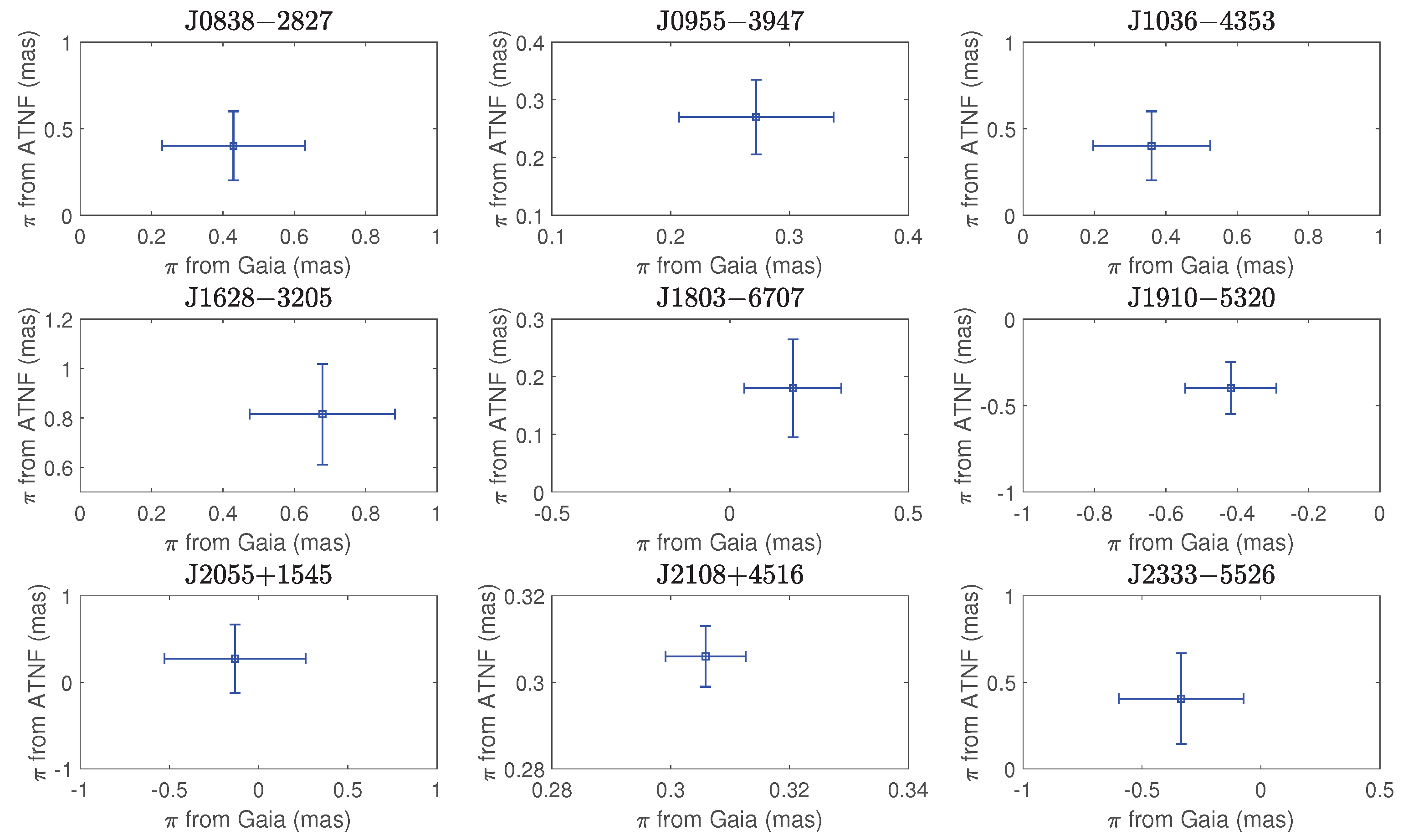

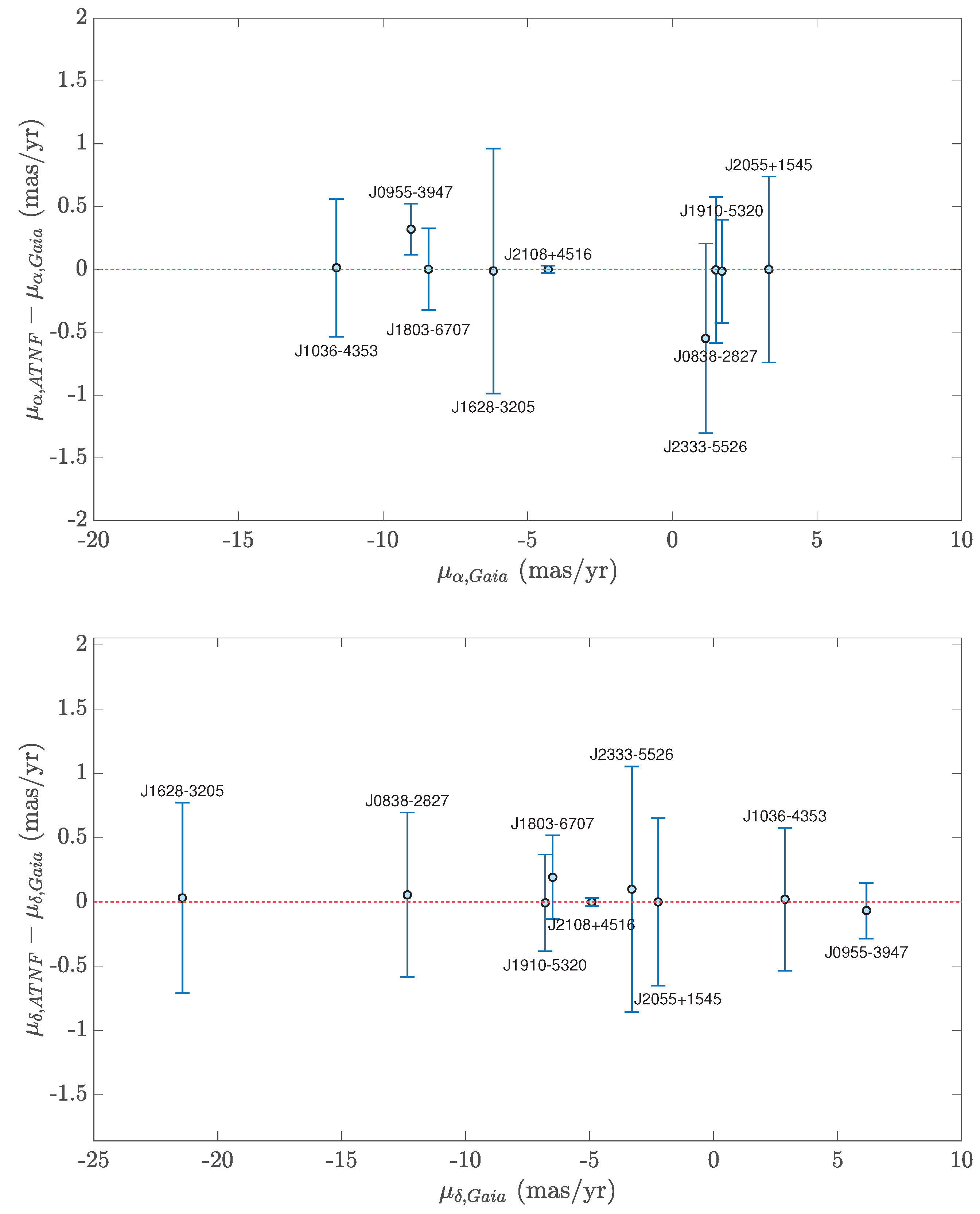

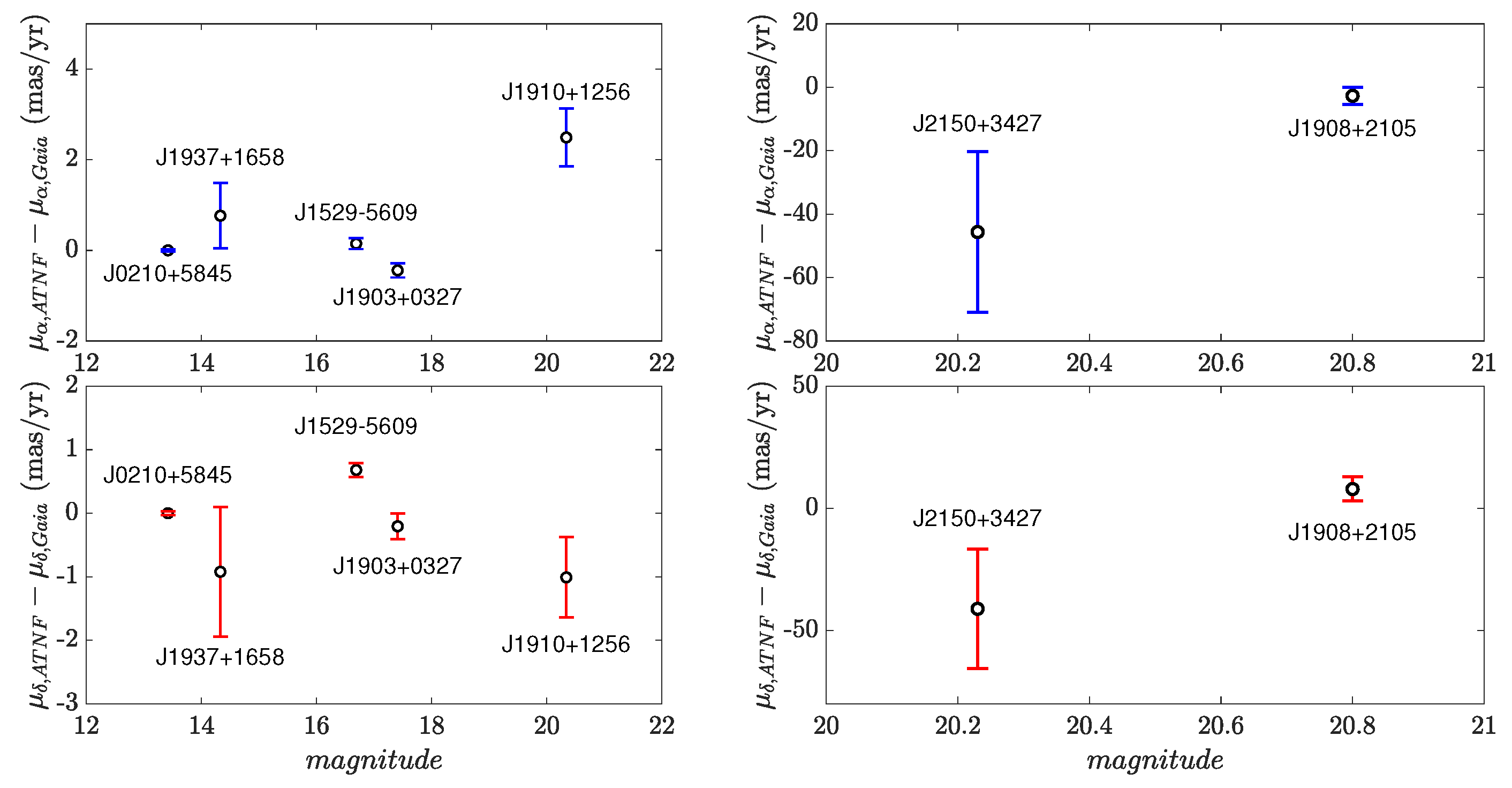

3. Results

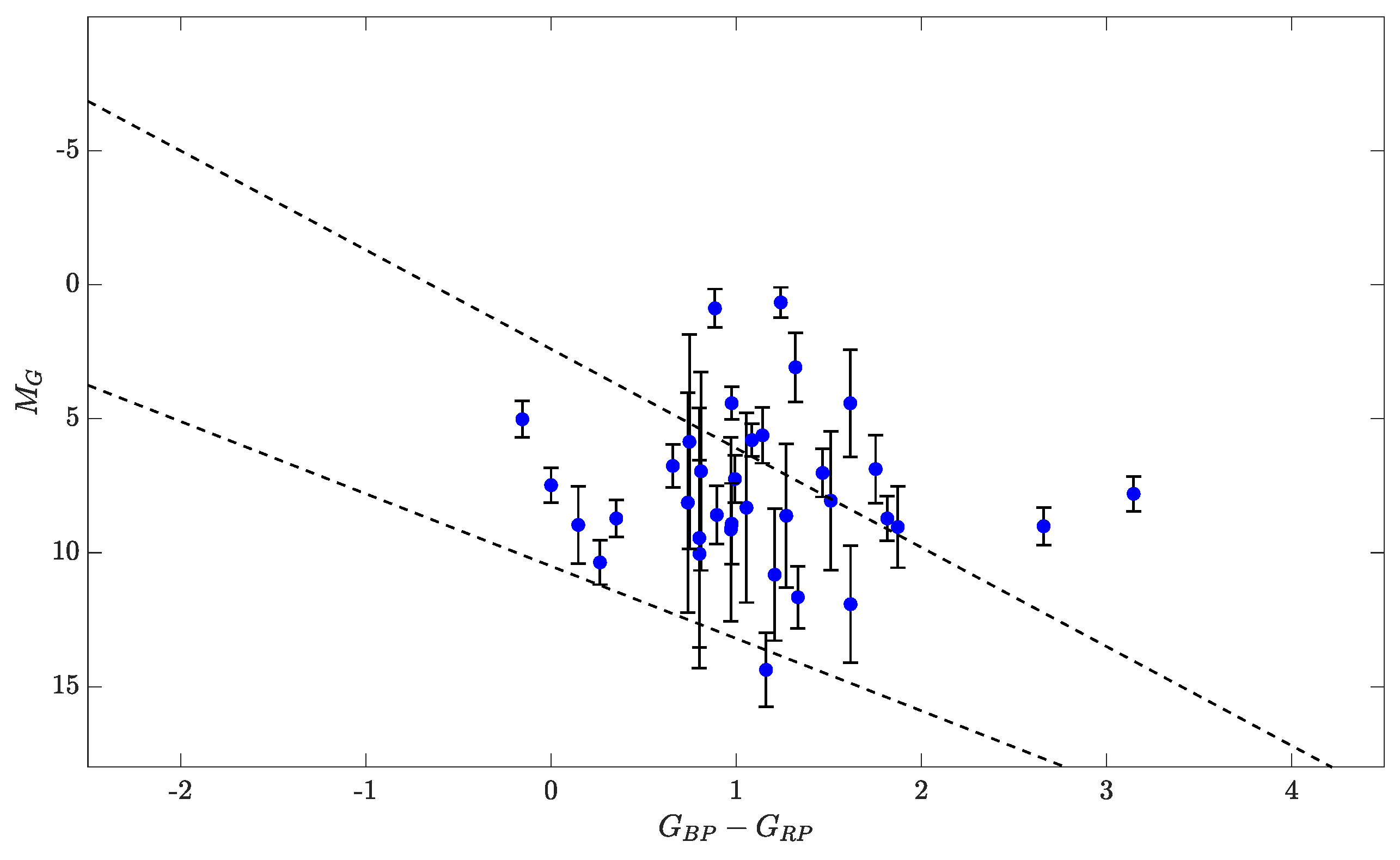

3.1. Main-sequence Star

3.2. Neutron Star

3.3. White Dwarf

3.4. Ultra-light Companion or Planet

3.5. Spiders

4. Discussions and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATNF | Australia Telescope National Facility |

| CVN | Chinese VLBI Network |

| DM | Dispersion Measure |

| DNS | double neutron star |

| DR | data release |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| FAST | Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical radio Telescope |

| GTC | Gran Telescopio Canarias |

| HR | Hertzsprung-Russell |

| IPTA | International Pulsar Timing Array |

| LBA | Long Baseline Array |

| LMXB | Low-mass X-ray binary |

| MeerKAT | Meer Karoo Array Telescope |

| MSP | Millisecond pulsar |

| NS | neutron star |

| PTA | Pulsar Timing Array |

| ToAs | pulse times of arrival |

| VLA | Very Large Array |

| VLBA | Very Long Baseline Array |

| VLBI | Very Long Baseline Interferometry |

References

- Alpar, M.A.; Cheng, A.F.; Ruderman, M.A.; Shaham, J. A new class of radio pulsars. Nature 1982, 300, 728-730. [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, V.; Srinivasan, G. On the origin of the recently discovered ultra-rapid pulsar. Current Science, 1982, 51, 1096-1099.

- Bhattacharya, D.; van den Heuvel, E.P.J. Formation and evolution of binary and millisecond radio pulsars. Physics Reports, 1991, 203, 1-2. [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Deller, A.T.; Stappers, B.W.; Lazio, T.J.W.; Kaplan, D.; Chatterjee, S.; Brisken, W.; Cordes, J.; Freire, P.C.C.; Fonseca, E.; et al. The MSPSRπ catalogue: VLBA astrometry of 18 millisecond pulsars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2023, 519, 4982–5007. [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, G.; Archibald, A.; Arzoumanian, Z.; Backer, D.; Bailes, M.; Bhat, N.D.R.; Burgay, M.; Burke-Spolaor, S.; Champion, D.; Cognard, I.; et al. The International Pulsar Timing Array project: using pulsars as a gravitational wave detector. Class. Quantum Grav. 2010, 27, 084013. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.S.E. Surrounded by spiders! New black widows and redbacks in the Galactic field. Proceedings of the IAU 2013, 291, 127-132. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.S.E.; Al Noori, H.; Torres, R.A.; McLaughlin, M.A.; Gentile, P.A.; Hessels, J.W.T.; Ransom, S.M.; Ray, P.S.; Kerr, M.; Breton, R.P. X-Ray and Optical Properties of Black Widows and Redbacks. Proceedings of the IAU 2018, 337, 43-46. [CrossRef]

- Gaia Collaboration.; Prusti, T.; de Bruijne, J.H.J.; Brown, A.G.A.; Vallenari, A.; Babusiaux, C.; Bailer-Jones, C.A.L.; Bastian, U.; Biermann, M.; Evans, D.W.; et al. The Gaia mission. Astron. Astrophys. 2016, 595, A1. [CrossRef]

- Manchester, R.N.; Hobbs, G.B.; Teoh, A.; Hobbs, M. The Australia Telescope National Facility Pulsar Catalogue. Astron. J. 2005, 129, 1993-2006. [CrossRef]

- Pancino, E.; Bellazzini, M.; Giuffrida, G.; Marinoni, S. Globular clusters with Gaia. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2017, 467, 412-427. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.B. TOPCAT & STIL: Starlink Table/VOTable Processing Software. Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems XIV 2005, 347.

- Antoniadis, J. Gaia pulsars and where to find them. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021, 501, 1116-1126. [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhu, Z.; Antoniadis, J.; Liu, J.C.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, N. Comparison of dynamical and kinematic reference frames via pulsar positions from timing, Gaia, and interferometric astrometry. Astron. Astrophys. 2023, 670, A173. [CrossRef]

- Becker, W.; Trümper, J. Detection of pulsed X-rays from the binary millisecond pulsar J0437 - 4715. Nature 1993, 365, 528-530. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, B.C.; Fonseca, E.; McKee, J.W.; Meyers, B.W.; Luo, J.; Tan, C.M.; Stairs, I.H.; Kaspi, V.M.; van Kerkwijk, M.H.; Bhardwaj, M.; et al. CHIME Discovery of a Binary Pulsar with a Massive Nondegenerate Companion. Astron. J. 2023, 943, 57. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.D.; Wang, N.; Yuan, J.P.; Li, D.; Wang, P.; Xue, M.Y.; Zhu, W.W.; Miao, C.C.; Yan, W.M.; Wang, J.B.; et al. PSR J2150+3427: A Possible Double Neutron Star System. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2023, 958, L17. [CrossRef]

- Desvignes, G.; Caballero, R.N.; Lentati, L.; Verbiest, J.P.W.; Champion, D.J.; Stappers, B.W.; Janssen, G.H.; Lazarus, P.; Osłowski, S.; Babak, S.; et al. High-precision timing of 42 millisecond pulsars with the European Pulsar Timing Array. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 458, 3341-3380. [CrossRef]

- Mingarelli, C.M.F.; Anderson, L.; Bedell, M.; Spergel, D.N.; Moran, A. Improving Binary Millisecond Pulsar Distances with Gaia. eprint arXiv 2018. [CrossRef]

- Deneva, J.S.; Ray, P.S.; Camilo, F.; Freire, P.C.C.; Cromartie, H.T.; Ransom, S.M.; Ferrara, E.; Kerr, M.; Burnett, T.H.; Parkinson, P.M.S. Timing of Eight Binary Millisecond Pulsars Found with Arecibo in Fermi-LAT Unidentified Sources. Astron. J. 2021, 909, 6. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Bhattacharyya, B.; Kumari, S.; Johnston, S.; Weltevrede, P.; Roy, J. Exploring Unusual High-frequency Eclipses in MSP J1908+2105. Astron. J. 2025, 982, 168. [CrossRef]

- Halpern, J.P.; Strader, J.; Li, M. A Likely Redback Millisecond Pulsar Counterpart of 3FGL J0838.8-2829. Astron. J. 2017, 844, 150. [CrossRef]

- Rea, N.; Coti Zelati, F.; Esposito, P.; D’Avanzo, P.; de Martino, D.; Israel, G.L.; Torres, D.F.; Campana, S.; Belloni, T.M.; Papitto, A.; et al. Multiband study of RX J0838-2827 and XMM J083850.4-282759: a new asynchronous magnetic cataclysmic variable and a candidate transitional millisecond pulsar. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2017, 471, 2902-2916. [CrossRef]

- Thongmeearkom, T.; Clark, C.J.; Breton, R.P.; Burgay, M.; Nieder, L.; Freire, P.C.C.; Barr, E.D.; Stappers, B.W.; Ransom, S.M.; Buchner, S.; et al. A targeted radio pulsar survey of redback candidates with MeerKAT. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2024, 530, 4676-4694. [CrossRef]

- Drake, A.J.; Djorgovski, S.G.; Catelan, M.; Graham, M.J.; Mahabal, A.A.; Larson, S.; Christensen, E.; Torrealba, G.; Beshore, E.; McNaught, R.H.; et al. The Catalina Surveys Southern periodic variable star catalogue. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2017, 469, 3688-3712. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.L.; Hou, X.; Strader, J.; Takata, J.; Kong, A.K.H.; Chomiuk, L.; Swihart, S.J.; Hui, C.Y.; Cheng, K.S. Multiwavelength Observations of a New Redback Millisecond Pulsar Candidate: 3FGL J0954.8-3948. Astron. J. 2018, 863, 194. [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.J.; Breton, R.P.; Barr, E.D.; Burgay, M.; Thongmeearkom, T.; Nieder, L.; Buchner, S.; Stappers, B.; Kramer, M.; Becker, W.; et al. The TRAPUM L-band survey for pulsars in Fermi-LAT gamma-ray sources. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2023, 519, 5590-5606. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Halpern, J.P.; Thorstensen, J.R. Optical Counterparts of Two Fermi Millisecond Pulsars: PSR J1301+0833 and PSR J1628-3205. Astron. J. 2014, 795, 115. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, J.; Halpern, J. Observations and Modeling of the Companions of Short Period Binary Millisecond Pulsars: Evidence for High-mass Neutron Stars. Astron. J. 2014, 793, 78. [CrossRef]

- Au, K.Y.; Strader, J.; Swihart, S.J.; Lin, L.C.C.; Kong, A.K.H.; Takata, J.; Hui, C.Y.; Panurach, T.; Molina, I.; Aydi, E.; et al. Multiwavelength Observations of a New Redback Millisecond Pulsar 4FGL J1910.7-5320. Astron. J. 2023, 943, 103. [CrossRef]

- Dodge, O.G.; Breton, R.P.; Clark, C.J.; Burgay, M.; Strader, J.; Au, K.Y.; Barr, E.D.; Buchner, S.; Dhillon, V.S.; Ferrara, E.C.; et al. Mass estimates from optical modelling of the new TRAPUM redback PSR J1910-5320. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2024, 528, 4337-4353. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.F.; Olszanski, T.E.E.; Deneva, J.S.; Freire, P.C.C.; McLaughlin, M.A.; Stovall, K.; Bagchi, M.; Martinez, J.G.; Perera, B.B.P. Discovery and Timing of Millisecond Pulsars with the Arecibo 327 MHz Drift-scan Survey. Astron. J. 2023, 956, 132. [CrossRef]

- Turchetta, M.; Sen, B.; Simpson, J.A.; Linares, M.; Breton, R.P.; Casares, J.; Kennedy, M.R.; Shahbaz, T. Discovery of the variable optical counterpart of the redback pulsar PSR J2055+1545. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2025, 538, 380-394. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, S.; Acero, F.; Ackermann, M.; Ajello, M.; Atwood, W.B.; Axelsson, M.; Baldini, L.; Ballet, J.; Barbiellini, G.; Bastieri, D.; et al. Fermi Large Area Telescope Fourth Source Catalog. Astron. J. Supplement Series 2020, 247, 33. [CrossRef]

- Swihart, S.J.; Strader, J.; Urquhart, R.; Orosz, J.A.; Shishkovsky, L.; Chomiuk, L.; Salinas, R.; Aydi, E.; Dage, K.C.; Kawash, A.M. A New Likely Redback Millisecond Pulsar Binary with a Massive Neutron Star: 4FGL J2333.1-5527. Astron. J. 2020, 892, 21. [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.J.; Kerr, M.; Barr, E.D.; Bhattacharyya, B.; Breton, R.P.; Bruel, P.; Camilo, F.; Chen, W.; Cognard, I.; Cromartie, H.T.; et al. Neutron star mass estimates from gamma-ray eclipses in spider millisecond pulsar binaries. Nature Astronomy 2023, 7, 451-462. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D.L.; van Kerkwijk, M.H.; Koester, D.; Stairs, I.H.; Ransom, S.M.; Archibald, A.M.; Hessels, J.W.T.; Boyles, J. Spectroscopy of the Inner Companion of the Pulsar PSR J0337+1715. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2014, 783, L23. [CrossRef]

- Ransom, S.M.; Stairs, I.H.; Archibald, A.M.; Hessels, J.W.T.; Kaplan, D.L.; van Kerkwijk, M.H.; Boyles, J.; Deller, A.T.; Chatterjee, S.; Schechtman-Rook, A.; et al. A millisecond pulsar in a stellar triple system. Nature 2014, 505, 520-524. [CrossRef]

- Tauris, T.M.; van den Heuvel, E.P.J. Formation of the Galactic Millisecond Pulsar Triple System PSR J0337+1715—A Neutron Star with Two Orbiting White Dwarfs. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2014, 781, L13. [CrossRef]

- Bailes, M.; Johnston, S.; Bell, J.F.; Lorimer, D.R.; Stappers, B.W.; Manchester, R.N.; Lyne, A.G.; Nicastro, L.; Gaensler, B.M. Discovery of Four Isolated Millisecond Pulsars. Astron. J. 1997, 481, 386. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D.L.; Kupfer, T.; Nice, D.J.; Irrgang, A.; Heber, U.; Arzoumanian, Z.; Beklen, E.; Crowter, K.; DeCesar, M.E.; Demorest, P.B.; et al. PSR J1024-0719: A Millisecond Pulsar in an Unusual Long-period Orbit. Astron. J. 2016, 826, 86. [CrossRef]

- DeCesar, M.E.; Ransom, S.M.; Kaplan, D.L.; Ray, P.S.; Geller, A.M. A Highly Eccentric 3.9 Millisecond Binary Pulsar in the Globular Cluster NGC 6652. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2015, 807, L23. [CrossRef]

- Bassa, C.G.; Janssen, G.H.; Stappers, B.W.; Tauris, T.M.; Wevers, T.; Jonker, P.G.; Lentati, L.; Verbiest, J.P.W.; Desvignes, G.; Graikou, E.; et al. A millisecond pulsar in an extremely wide binary system. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 460, 2207-2222. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.M.; Manchester, R.N.; Wang, N. A New Electron-density Model for Estimation of Pulsar and FRB Distances. Astron. J. 2017, 835, 29. [CrossRef]

- Cordes, J.M.; Lazio, T.J.W. NE2001.I. A New Model for the Galactic Distribution of Free Electrons and its Fluctuations. eprint arXiv 2002. [CrossRef]

- Gaia Collaboration.; Vallenari, A.; Brown, A.G.A.; Prusti, T.; de Bruijne, J.H.J.; Arenou, F.; Babusiaux, C.; Biermann, M.; Creevey, O.L.; Ducourant, C.; et al. Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties. Astron. Astrophys. 2023, 674, A1. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Song, Y.Q.; Yan, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, G.L. Linking Planetary Ephemeris Reference Frames to ICRF via Millisecond Pulsars. Universe 2025, 11, 54. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Shen, Z.Q.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, H.Y.; Cui, L.; Luo, J.T.; Chen, R.R.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, H.; et al. Pathfinding Pulsar Observations with the CVN Incorporating the FAST. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2024, 41, 117501. [CrossRef]

| PSR | Gaia source | G | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (”) | (mas) | (mas/yr) | (mas/yr) | (mas/yr) | (mas/yr) | (s) | (d) | (mag) | ||

| J0045-7319 | 4685849525145183232 | 0.531 | −0.04(4) | - | - | 0.58(5) | −1.49(5) | 0.926 | 51.17 | 16.20 |

| J0337+1715 | 44308738051547264 | 0.021 | 0.54(20) | 4.8(5) | −4.4(5) | 5.48(19) | −4.43(16) | 0.003 | 1.63 | 18.05 |

| J0348+0432 | 3273288485744249344 | 0.015 | −0.04(78) | 4.04(16) | 3.5(6) | 3.44(13) | −0.23(9) | 0.04 | 0.10 | 20.59 |

| J0437-4715 | 4789864076732331648 | 0.688 | 7.10(5) | 121.44(5) | −71.47(5) | 121.65(6) | −70.70(7) | 0.006 | 5.74 | 20.35 |

| J0534+2200 | 3403818172572314624 | 0.004 | 0.51(8) | −11.34(6) | 2.65(14) | −11.51(10) | 2.30(6) | 0.033 | - | 16.53 |

| J0534-6703 | 4660152083015919872 | 1.555 | 0.16(16) | - | - | 1.27(26) | 0.44(19) | 1.818 | - | 18.86 |

| J0540-6919 | 4657672890443808512 | 0.069 | 0.67(13) | - | - | 3.59(21) | 4.97(23) | 0.05 | - | 20.77 |

| J0614+2229 | 3376990741688176384 | 0.390 | −1.22(7) | −0.24(4) | −1.25(4) | −0.53(7) | −0.87(5) | 0.335 | - | 19.61 |

| J0838-2827 | 5645504747023158400 | 0.002 | 0.43(40) | 1.5(3) | −12.3(3) | 1.50(3) | −12.36(3) | 0.004 | 0.22 | 20.00 |

| J0857-4424 | 5331775184393659264 | 0.526 | 2.12(3) | - | - | −8.27(3) | 7.74(3) | 0.3 | - | 18.37 |

| J0955-3947 | 5419965878188457984 | 0.003 | 0.27(13) | −9.00(1) | 6.10(1) | −9.03(1) | 6.17(1) | 0.002 | 0.39 | 18.47 |

| J1012+5307 | 851610861391010944 | 0.130 | 1.74(3) | 2.62(3) | −25.49(4) | 2.74(3) | −25.92(3) | 0.005 | 0.61 | 19.59 |

| J1023+0038 | 3831382647922429952 | 0.120 | 0.69(7) | 4.76(3) | −17.34(4) | 4.61(7) | −17.28(8) | 0.002 | 0.20 | 16.23 |

| J1024-0719 | 3775277872387310208 | 0.252 | 0.86(28) | −35.28(5) | −48.23(1) | −35.46(32) | −48.35(36) | 0.005 | - | 19.15 |

| J1036-4353 | 5367876720979404288 | 0.001 | 0.36(33) | −11.6(3) | 2.9(3) | −11.61(2) | 2.88(3) | 0.002 | 0.26 | 19.71 |

| J1036-8317 | 5192229742737133696 | 0.063 | 0.19(14) | −11.35(6) | 2.86(6) | −11.34(2) | 2.76(2) | 0.003 | 0.34 | 18.57 |

| J1048+2339 | 3990037124929068032 | 0.031 | 0.49(44) | −19(3) | −9.4(7) | −15.45(4) | −11.62(3) | 0.005 | 0.25 | 19.59 |

| J1227-4853 | 6128369984328414336 | 0.075 | 0.46(46) | −18.7(2) | 7.39(11) | −18.77(1) | 7.30(1) | 0.002 | 0.29 | 18.07 |

| J1302-6350 | 5862299960127967488 | 0.006 | 0.44(1) | −7.01(3) | −0.53(3) | −7.09(1) | −0.34(1) | 0.048 | 1236.72 | 9.63 |

| J1305-6455 | 5858993350772345984 | 0.302 | 0.13(4) | - | - | −6.57(3) | −0.93(4) | 0.6 | - | 16.04 |

| J1306-4035 | 6140785016794586752 | 0.332 | 0.31(15) | - | - | −6.19(1) | 4.16(1) | 0.002 | 1.10 | 18.09 |

| J1311-3430 | 6179115508262195200 | 0.042 | 1.93(10) | - | - | −6.13(16) | −5.15(7) | 0.003 | 0.07 | 20.44 |

| J1417-4402 | 6096705840454620800 | 0.476 | 0.20(5) | −4.70(1) | −5.1(9) | −4.76(4) | −5.10(5) | 0.003 | 5.37 | 15.77 |

| J1431-4715 | 6098156298150016768 | 0.078 | 0.53(13) | −12.0(4) | −14.5(3) | −11.83(1) | −14.52(2) | 0.002 | 0.45 | 17.73 |

| J1435-6100 | 5878387705005976832 | 0.409 | 0.42(25) | −5.5(2) | −2.4(3) | −5.26(2) | −3.23(2) | 0.009 | 1.35 | 18.90 |

| J1509-6015 | 5876497399692841088 | 0.037 | 0.19(11) | - | - | −5.25(1) | −2.39(1) | 0.339 | - | 17.76 |

| J1542-5133 | 5886184887428050048 | 0.927 | −0.21(27) | - | - | −2.25(3) | −4.86(3) | 1.784 | - | 19.02 |

| J1546-5302 | 5885808648276626304 | 1.294 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.6 | - | 21.09 |

| J1622-0315 | 4358428942492430336 | 0.070 | 0.62(30) | −13.2(4) | 2.3(3) | −13.18(3) | 2.30(2) | 0.004 | 0.16 | 19.21 |

| J1624-4411 | 5992089027071540352 | 0.302 | 0.94(49) | - | - | −3.43(5) | −7.68(4) | 0.2 | - | 19.88 |

| J1624-4721 | 5941843098026132608 | 1.053 | 0.23(98) | - | - | −3.88(13) | −2.46(8) | 0.449 | - | 20.37 |

| J1628-3205 | 6025344817107454464 | 0.125 | 0.68(41) | −6.2(5) | −21.4(4) | −6.19(5) | −21.43(3) | 0.003 | 0.21 | 19.48 |

| J1653-0158 | 4379227476242700928 | 0.011 | 1.77(8) | −19.6(19) | −3.7(12) | −17.30(10) | −3.24(7) | 0.002 | 0.05 | 20.45 |

| J1723-2837 | 4059795674516044800 | 0.434 | 1.07(4) | −11.71(9) | −23.99(7) | −11.73(4) | −24.05(3) | 0.002 | 0.62 | 15.54 |

| J1803-6707 | 6436867623955512064 | 0.002 | 0.18(27) | −8.43(13) | −6.30(10) | −8.43(20) | −6.49(23) | 0.002 | 0.38 | 19.42 |

| J1810+1744 | 4526229058440076288 | 0.042 | 0.65(54) | 7.5(2) | −3.6(4) | 7.54(5) | −4.19(5) | 0.002 | 0.15 | 20.00 |

| J1816+4510 | 2115337192179377792 | 0.012 | 0.22(10) | 5.3(8) | −3.0(10) | −0.06(12) | −4.4(12) | 0.003 | 0.36 | 18.20 |

| J1817-3618 | 4038146565444090240 | 1.410 | 0.17(13) | 19(5) | −16(17) | −3.16(15) | −6.09(11) | 0.4 | - | 17.62 |

| J1839-0905 | 4155609699080401920 | 0.138 | 0.42(6) | - | - | −3.26(6) | −4.60(6) | 0.4 | - | 16.51 |

| J1851+1259 | 4504706118346043392 | 0.285 | 0.96(108) | - | - | −3.56(119) | −7.61(125) | 1.2 | - | 20.50 |

| J1852+0040 | 4266508881354196736 | 0.607 | 2.39(90) | - | - | −1.01(76) | −4.63(66) | 0.105 | - | 20.19 |

| J1903-0258 | 4261581076409458304 | 0.552 | 0.61(26) | - | - | −0.59(35) | 3.78(34) | 0.3 | - | 18.92 |

| J1910-5320 | 6644467032871428992 | 0.004 | −0.42(26) | 1.7(20) | −6.8(20) | 1.71(21) | −6.79(18) | 0.002 | - | 19.12 |

| J1928+1245 | 4316237348443952128 | 0.184 | 0.15(17) | - | - | −0.35(16) | −4.62(16) | 0.003 | 0.14 | 18.23 |

| J1946+2052 | 1825839908094612992 | 0.421 | 1.13(44) | - | - | −2.38(39) | −5.27(38) | 0.02 | 0.08 | 19.85 |

| J1955+2908 | 2028584968839606784 | 0.153 | 0.47(17) | −0.98(5) | −4.05(6) | −3.17(14) | −7.83(17) | 0.006 | 117.35 | 18.67 |

| J1957+2516 | 1834595731470345472 | 0.034 | 2.15(85) | - | - | −4.49(52) | −12.29(101) | 0.004 | 0.24 | 20.28 |

| J1958+2846 | 2030000280820200960 | 1.172 | 0.38(26) | - | - | −3.64(22) | −7.26(28) | 0.3 | - | 19.32 |

| J1959+2048 | 1823773960079216896 | 0.758 | 1.19(136) | −16.0(5) | −25.8(6) | −19.27(124) | −26.56(124) | 0.002 | 0.38 | 20.18 |

| J2027+4557 | 2071054503122390144 | 0.318 | 0.52(3) | - | - | 2.08(34) | −2.12(32) | 1.1 | - | 15.71 |

| J2032+4127 | 2067835682818358400 | 0.028 | 0.57(2) | −2.99(5) | −0.74(6) | −2.88(17) | −0.95(20) | 0.143 | 16800 | 11.28 |

| J2039-5617 | 6469722508861870080 | 0.009 | 0.49(17) | 4.2(30) | −14.9(30) | 3.86(14) | −15.18(12) | 0.003 | 0.23 | 18.52 |

| J2055+1545 | 1763537692275731328 | 0.020 | −0.13(79) | - | - | 3.34(74) | −2.24(65) | 0.002 | - | 20.50 |

| J2108+4516 | 2162555482829978496 | 0.103 | 0.31(1) | −4.29(15) | −4.91(15) | −4.29(15) | −4.91(15) | 0.6 | 269.44 | 10.98 |

| J2129-0429 | 2672030065446134656 | 0.148 | 0.48(7) | 12.30(10) | 10.10(10) | 12.10(7) | 10.19(6) | 0.008 | 0.64 | 16.82 |

| J2215+5135 | 2001168543319218048 | 0.822 | 0.30(23) | 0.3(50) | 1.8(60) | 0.01(24) | 2.24(24) | 0.003 | 0.17 | 19.20 |

| J2333-5526 | 6496325574947304448 | 0.003 | −0.34(53) | 0.6(30) | −3.2(40) | 1.15(46) | −3.30(56) | 0.002 | 0.29 | 20.25 |

| J2339-0533 | 2440660623886405504 | 0.094 | 0.53(18) | 4.2(50) | −10.3(30) | 3.92(20) | −10.28(19) | 0.003 | 0.2 | 18.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).