Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Narrative Literature Review

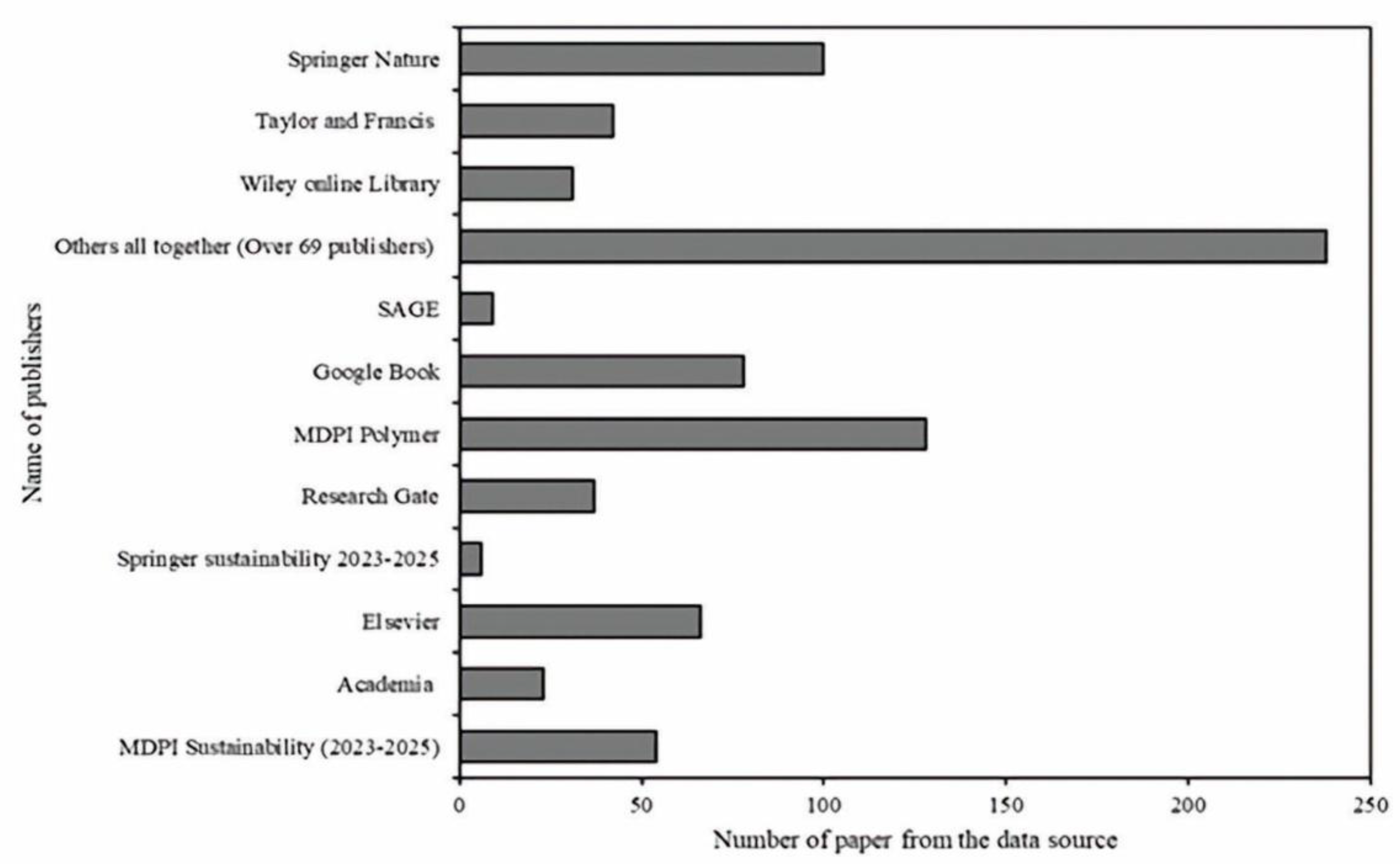

2.2. Systematic Literature Review

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Narrative Literature Review

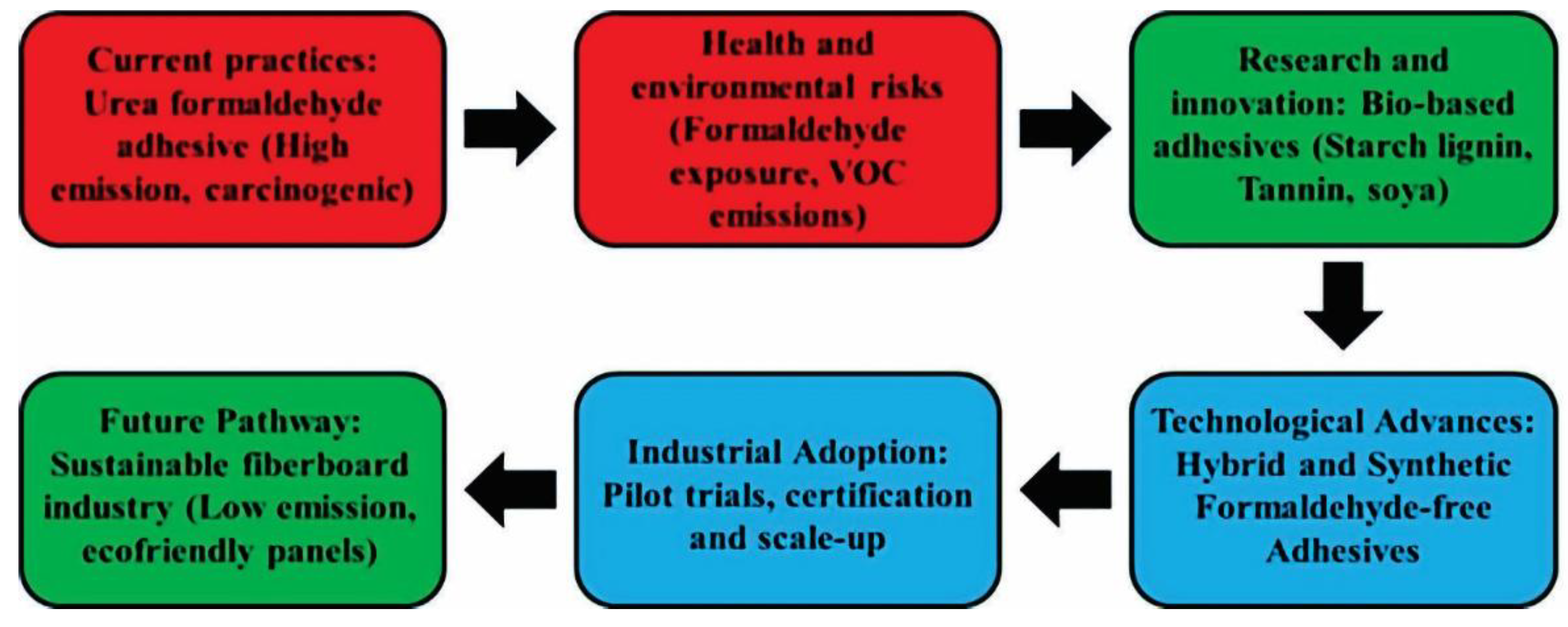

3.1.1. The Paradigm Shift in the Fiberboard Adhesive Industry

- Plant-Derived Protein Sources

- 2.

- Gelatin and animal proteins

3.1.2. Some Performance of Green Adhesives

3.1.3. Industrial Applications and Case Studies

3.1.4. The Urgent Need for a Paradigm Shift in Adhesive Utilization in the Fiberboard Industry

3.2. Systematic Literature Review

3.2.1. Technological Advancements in Green Adhesives for the Fiberboard Industry

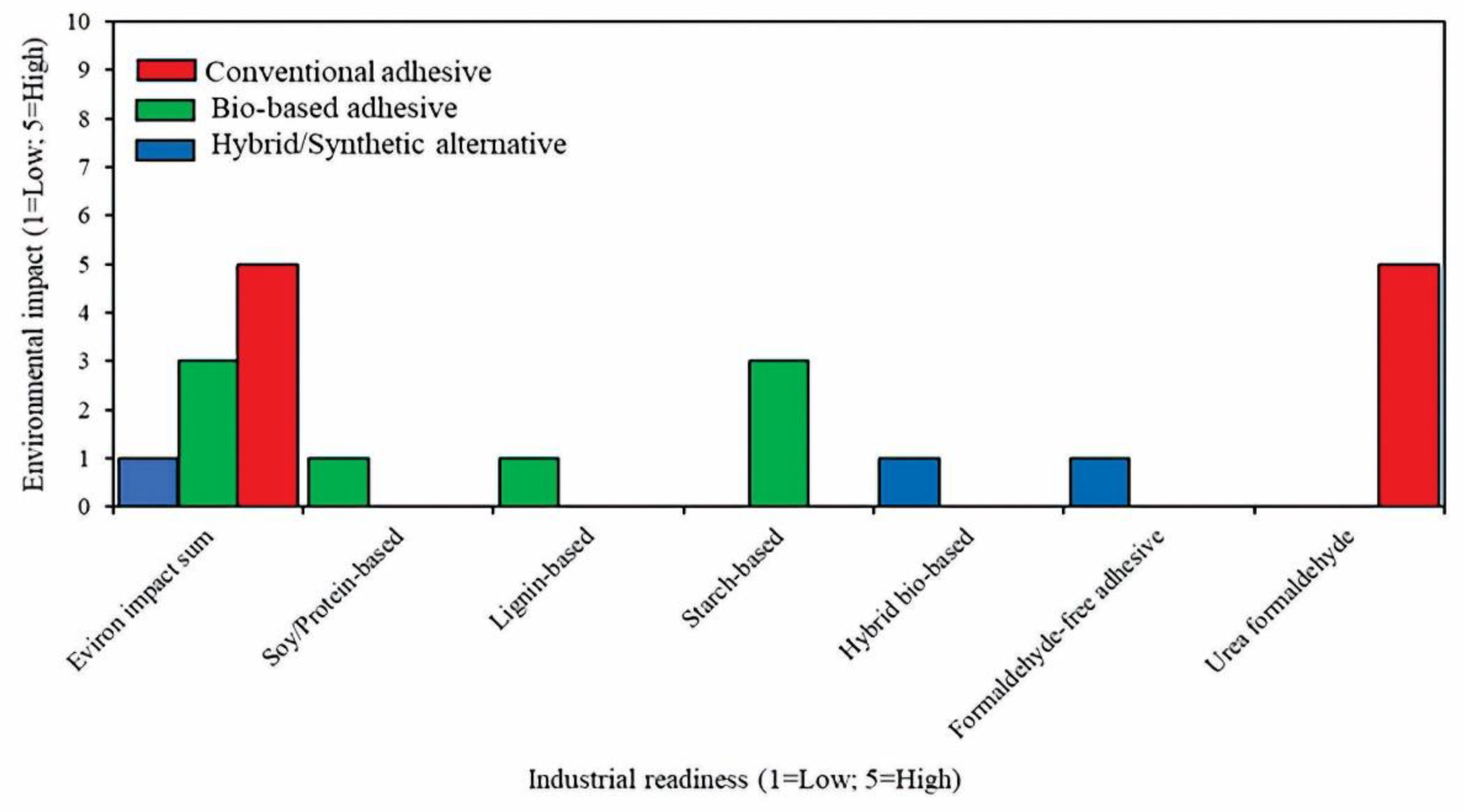

3.2.2. Green Adhesives, the Sustainable Alternatives

3.2.3. Challenges in Adopting Green Adhesives

3.2.3. Future Directions and Research Opportunities

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nielsen, G.D.; Wolkoff, P. Cancer effects of formaldehyde: a proposal for an indoor air guideline value. Arch. Toxicol. 2010, 84, 423–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAS National Academy of Sciences (2023). National Library of Medicine. Review of EPA’s 2023 Draft Formaldehyde Assessment. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 6004.

- ACS (2024). Formaldehyde and Cancer Risk. Cancer Risk and Preventive Navigation. American Cancer Society Medical and Editorial Content Team. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/chemicals/formaldehyde.html?utm_source=chatgpt.

- ACS (2024b). American Cancer Society. Formaldehyde and Cancer Risk. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/chemicals/formaldehyde.html#:~:text=One%20of%20its%20major%20goals,if%20Something%20Is%20a%20Carcinogen.

- Salo, L. (2017). The effects of coatings on the indoor air emissions of wood board. A? Aalto-yliopisto. Insinooritieteiden korkeakoulu. https://aaltodoc.aalto. 8849. [Google Scholar]

- Salthammer, T. , Gu, J., Gunschera, J., & Schieweck, A. (2023). Release of chemical compounds and particulate matter. In Springer Handbook of Wood Science and Technology (pp. 1949-1974). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.D.; Carvalho, L.H.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Ramos, R.M. Wood-Based Panels and Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs): An Overview on Production, Emission Sources and Analysis. Molecules 2025, 30, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, G.D.; Larsen, S.T.; Wolkoff, P. Re-evaluation of the WHO (2010) formaldehyde indoor air quality guideline for cancer risk assessment. Arch. Toxicol. 2016, 91, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elcosh (2010). Medium Density Fiberboard (MDF) Safety for Carpenters. elcosh – Electronic library of Construction Occupational Safety & Health. Mount Sinai School of Medicine. https://www.elcosh.org/document/2098/d001086/Medium%2BDensity%2BFiberboard%2B%28MDF%29%2BSafety%2Bfor%2BCarpenters.html?utm_source=chatgpt.

- Cheung, K.; McLean, D.; Pearce, N.; Douwes, J.; Cheung, K.; McLean, D. & Douwes, J. (2010). Exposures to hazardous airborne substances in the wood conversion sector. https://publichealth.massey.ac.nz/assets/Uploads/ACCwoodconversionreport-with-all-corrections-accepted-DEC-2010-v1.

- H`ng, P.; Lee, S.; Loh, Y.; Lum, W.; Tan, B. Production of Low Formaldehyde Emission Particleboard by Using New Formulated Formaldehyde Based Resin. Asian J. Sci. Res. 2011, 4, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frihart, C.R.; Chaffee, T.L.; Wescott, J.M. Long-Term Formaldehyde Emission Potential from UF- and NAF-Bonded Particleboards. Polymers 2020, 12, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yuan, S.; Jia, T.-T.; Li, M.; Hou, J.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; et al. A novel fluorescent probe for the detection of formaldehyde in real food samples, animal serum samples and gaseous formaldehyde. Food Chem. 2023, 411, 135483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boliandi, A. (2017). Development and characterization of new unsaturated polyester from renewable resources. https://www.politesi.polimi. 1058. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Gonzalez, M.N. (2018). Development and life cycle assessment of polymeric materials from renewable sources. https://hdl.handle. 1058. [Google Scholar]

- George, J.S.; Uthaman, A.; Reghunadhan, A.; Lal, H.M.; Thomas, S.; P, P.V. Bioderived thermosetting polymers and their nanocomposites: current trends and future outlook. Emergent Mater. 2022, 5, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seychal, G. (2025). Developing non-isocyanate polyurethane chemistry for more sustainable structural composites in a circular economy. http://hdl.handle. 1081. [Google Scholar]

- Yeboah, G.O. (2022). Assessing the use of bonded sawdust as a substitute material for carving in Ghana: Case study at Kumasi Metropolis in Ashanti Region (Doctoral dissertation, University of Education Winneba). http://41.74.91. 8080. [Google Scholar]

- Iswanto, A.H.; Lee, S.H.; Hussin, M.H.; Hamidon, T.S.; Hajibeygi, M.; Manurung, H.; Solihat, N.N.; Nurcahyani, P.R.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Antov, P.; et al. A comprehensive review of lignin-reinforced lignocellulosic composites: Enhancing fire resistance and reducing formaldehyde emission. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunky, M. (2021). Wood adhesives based on natural resources: a critical review: Part III. Tannin-and lignin-based adhesives. Progress in adhesion and adhesives, 6, 383-529. [CrossRef]

- Mantanis, G.I.; Athanassiadou, E.T.; Barbu, M.C.; Wijnendaele, K. Adhesive systems used in the European particleboard, MDF and OSB industries. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 13, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Liang, J.; Li, D.; Tu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Gong, F.; Gu, W.; Tang, M.; Ding, X.; Wu, Z.; et al. Fully Bio-Based Adhesive from Tannin and Sucrose for Plywood Manufacturing with High Performances. Materials 2022, 15, 8725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vnučec, D.; Kutnar, A.; Goršek, A. Soy-based adhesives for wood-bonding – a review. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2016, 31, 910–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Song, J. Improve Performance of Soy Flour-Based Adhesive with a Lignin-Based Resin. Polymers 2017, 9, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaiya, N.; Oyekanmi, A.A.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Olugbade, T.; Adeyeri, M.; Olaiya, F. Enzyme-assisted extraction of nanocellulose from textile waste: A review on production technique and applications. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samyn, P.; Meftahi, A.; Geravand, S.A.; Heravi, M.E.M.; Najarzadeh, H.; Sabery, M.S.K.; Barhoum, A. Opportunities for bacterial nanocellulose in biomedical applications: Review on biosynthesis, modification and challenges. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 231, 123316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://sdgs.un.

- Siddaway, A.P.; Wood, A.M.; Hedges, L.V. How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F. Writing a literature review. In the Portable Mentor: Expert Guide to a Successful Career in Psychology 2013, ed. M.J. Prinstein, MD Patterson, pp. 119–32. New York: Springer. 2nd ed.

- Campbell, M.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Sowden, A.; Thomson, H. Lack of transparency in reporting narrative synthesis of quantitative data: a methodological assessment of systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiology 2019, 105, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, S.; Sinha, C. Systematic Literature Review on Narratives in Organizations: Research Issues and Avenues for Future Research. Vision: J. Bus. Perspect. 2016, 20, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saz-Gil, I.; Bretos, I.; Díaz-Foncea, M. Cooperatives and Social Capital: A Narrative Literature Review and Directions for Future Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPPI (2002). Evidence for Policy and Practice Initiative (EPPI). www.eppi.ioe.ac.uk.

- Bennett, J.; Lubben, F.; Hogarth, S.; Campbell, B. Systematic reviews of research in science education: rigour or rigidity? Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2005, 27, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watcharakitti, J.; Win, E.E.; Nimnuan, J.; Smith, S.M. Modified starch-based adhesives: A review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Xue, J.; Wang, J.; Gou, J.; Semple, K.; Dai, C.; Zhang, S. A formaldehyde-free, high-performance soy protein-based adhesive enhanced by hyperbranched sulfuretted polyamidoamine-epichlorohydrin resin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 305, 141252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacem, M.; Dib, M.; Yahyaoui, M.I.; Boussetta, A.; Jamil, M.; Asehraou, A.; Moubarik, A. A new technology for assembling silylated MgAl-Hydrotalcite with a protein derived from shrimp waste to engineer an innovative antimicrobial biocomposite. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Bao, Z.; Li, Z.; Wei, R.; Yang, G.; Qing, Y.; Li, X.; Wu, Y. Develop a novel and multifunctional soy protein adhesive constructed by rosin acid emulsion and TiO2 organic-inorganic hybrid structure. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, Y.; Guo, Q.; Cao, J.; Li, J. Soy Protein Adhesive Enhanced Through Supramolecular Interaction with Tannic Acid Modified Montmorillonite. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2024, 31, e202402718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Xie, W.; Tang, Y.; Yang, F.; Gong, C.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Li, C. Preparation and Characterization of Soybean Protein Adhesives Modified with an Environmental-Friendly Tannin-Based Resin. Polymers 2023, 15, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azeem, B. Stimuli-Responsive Starch-Based Biopolymer Coatings for Smart and Sustainable Fertilizers. Gels 2025, 11, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Arreola, E.; Martin-Torres, G.; Lozada-Ramírez, J.D.; Hernández, L.R.; Bandala-González, E.R.; Bach, H. Biodiesel production and de-oiled seed cake nutritional values of a Mexican edible Jatropha curcas. Renew. Energy 2015, 76, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambarato, B.C.; Carvalho, A.K.F.; De Oliveira, F.; da Silva, S.S.; da Silva, M.L.; Bento, H.B.S. Soy Molasses: A Sustainable Resource for Industrial Biotechnology. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherzadeh, O.; Caro, D. Drivers of water and land use embodied in international soybean trade. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 223, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, L.; Cai, W.; Ding, Q.; Hu, W.; Peng, D.; Li, W.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, X.; Yu, C.; et al. The land footprint of the global food trade: Perspectives from a case study of soybeans. Land Use Policy 2021, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lei, H.; Xi, X.; Li, C.; Hou, D.; Song, J.; Du, G. A sustainable tannin-citric acid wood adhesive with favorable bonding properties and water resistance. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2023, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zou, J.; Yu, M.; Mondal, A.K.; Li, S.; Tang, Z. Physically crosslinked tannic acid-based adhesive for bonding wood. Cellulose 2024, 31, 6945–6954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Islam, N.; Faruk, O.; Ashaduzzaman; Dungani, R. Review on tannins: Extraction processes, applications and possibilities. South Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 135, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, M.H.; Latif, N.H.A.; Hamidon, T.S.; Idris, N.N.; Hashim, R.; Appaturi, J.N.; Brosse, N.; Ziegler-Devin, I.; Chrusiel, L.; Fatriasari, W.; et al. Latest advancements in high-performance bio-based wood adhesives: A critical review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 21, 3909–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristri, M.A.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Iswanto, A.H.; Fatriasari, W.; Sari, R.K.; Antov, P.; Gajtanska, M.; Papadopoulos, A.N.; Pizzi, A. Bio-Based Polyurethane Resins Derived from Tannin: Source, Synthesis, Characterisation, and Application. Forests 2021, 12, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliaro, M.; Albanese, L.; Scurria, A.; Zabini, F.; Meneguzzo, F.; Ciriminna, R. Tannin: a new insight into a key product for the bioeconomy in forest regions. Biofuels, Bioprod. Biorefining 2021, 15, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Ge, Y.; Wang, L. Tannic acid crosslinked chitosan/gelatin/SiO2 biopolymer film with superhydrophobic, antioxidant and UV resistance properties for prematuring fruit packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teymoori, M.; Poorkhalil, A.; Farrokhzad, H.; Tabesh, H. Glucose responsive microneedle patch using a reversible and an irreversible crosslinking agents. Results Eng. 2025, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iswanto, A.H.; Manurung, H.; Sohail, A.; Hua, L.S.; Antov, P.; Nawawi, D.S.; Latifah, S.; Kayla, D.S.; Kusumah, S.S.; Lubis, M.A.R.; et al. Thermo-Mechanical, Physico-Chemical, Morphological, and Fire Characteristics of Eco-Friendly Particleboard Manufactured with Phosphorylated Lignin Addition. J. Renew. Mater. 2024, 12, 1311–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yang, Y.; Yan, L.; Lin, B.; Dai, L.; Huang, Z.; Si, C. Custom-designed polyphenol lignin for the enhancement of poly(vinyl alcohol)-based wood adhesive. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 258, 129132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhamou, A.A.; Abid, L.; Calvez, I.; Cloutier, A.; Nejad, M.; Stevanovic, T.; Landry, V. Advances in Lignin Chemistry, Bonding Performance, and Formaldehyde Emission Reduction in Lignin-Based Urea-Formaldehyde Adhesives: A Review. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202500491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafisah, P.M.; Wibowo, E.S.; Mubarok, M.; Darmawan, W.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Santoso, A.; Kusumah, S.S.; Afif, S.; Park, B.-D. The role of lignin in enhancing adhesion performance and reducing formaldehyde emissions of phenol–resorcinol–formaldehyde resin adhesives. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 323, 147251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bairami Habashi, R. , & Abdollahi, M. Functionalization of Lignin by Phenolation. Springer Nature. Handbook of Lignin 2025, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dona, N.L.K.; Smith, R.C. Tailoring Polymer Properties Through Lignin Addition: A Recent Perspective on Lignin-Derived Polymer Modifications. Molecules 2025, 30, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watumlawar, E. C. , & Park, B. D. (2025). Lignin-Based Wood Adhesives. In Green Lignocellulosic-Based Panels: Manufacturing, Characterization and Applications (pp. 29-65). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, P. The role of lignin in adhesives for lignin-based formaldehyde-based resins: a review. Biomass- Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 16307–16341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladzadabbasabadi, N.; Dheyab, M.A.; Tavassoli, M.; Naebe, M.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Ghasemlou, M.; Ivanova, E.P.; Adhikari, B. Leveraging lignin as mussel-bioinspired adhesives and fillers for sustainable food-packaging applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 318, 145029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, N.R.; Suharmiati, S.; Yaseen, Z.M.; Airlangga, B. Advancements and trends in lignin extraction from wood residue: a bibliometric and comprehensive review. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aro, T.; Fatehi, P. Production and Application of Lignosulfonates and Sulfonated Lignin. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 1861–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Hou, M.; Cao, X.; Jia, W.; Huang, L.; Wu, L.; Wang, B.; Sheng, X.; Guo, Y.; et al. Comparative study on the physicochemical characteristics of lignin via sequential solvent fractionation of ethanol and Kraft lignin derived from poplar and their applications. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, P.; de Melo, R.R.; Mitchual, S.J.; Owusu, F.W.; Mensah, M.A.; Donkoh, M.B.; Paula, E.A.d.O.; Pedrosa, T.D.; Junior, F.R.R.; Rusch, F. Ecological adhesive based on cassava starch: a sustainable alternative to replace urea-formaldehyde (UF) in particleboard manufacture. Mater. De Jan. 2024, 29, e20230373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, P.; de Melo, R.R.; Paula, E.A.d.O.; Pimenta, A.S.; de Moura, J.; Rusch, F. Eco-Friendly Particleboards Produced with Banana Tree (Musa paradisiaca) Pseudostem Fibers Bonded with Cassava Starch and Urea-Formaldehyde Adhesives. J. Renew. Mater. 2025, 13, 1475–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Zhang, C.; Deng, Y.; Xie, P.; Liu, L.; Cheng, J. Research advances in chemical modifications of starch for hydrophobicity and its applications: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 240, 116292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Khan, M.R.; Ahmad, I.; Sadiq, M.B. Recent advances in modified starch based biodegradable food packaging: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashori, A.; Kuzmin, A. Effect of chitosan-epoxy ratio in bio-based adhesive on physical and mechanical properties of medium density fiberboards from mixed hardwood fibers. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, R.L.C.G.; Bezjak, D.; Corrales, T.P.; Kappl, M.; Petri, D.F. Chitosan/vanillin/polydimethylsiloxane scaffolds with tunable stiffness for muscle cell proliferation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 286, 138445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, K.; Ganesan, A.R.; Ezhilarasi, P.; Kondamareddy, K.K.; Rajan, D.K.; Sathishkumar, P.; Rajarajeswaran, J.; Conterno, L. Green and eco-friendly approaches for the extraction of chitin and chitosan: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 287, 119349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, F. , Su, J., Zhong, J., & Qiu, M. (2023). Recent Advancement of Gelatin for Tissue Engineering Applications. In Interaction of Nanomaterials with Living Cells (pp. 821-837). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Pulidori, E.; Duce, C.; Bramanti, E.; Ciccone, L.; Cipolletta, B.; Tani, G.; Ioio, L.D.; Birolo, L.; Bonaduce, I. Characterization of the secondary structure, renaturation and physical ageing of gelatine adhesives. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, X.; Tang, Z.; Li, X.; Morrell, J.J.; Beaugrand, J.; Yao, Y.; Zheng, Q. Antibacterial Films Made of Bacterial Cellulose. Polymers 2022, 14, 3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Zhao, X.-Q.; Li, D.-M.; Wu, Y.-M.; Wahid, F.; Xie, Y.-Y.; Zhong, C. Review on the strategies for enhancing mechanical properties of bacterial cellulose. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 15265–15293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, D.A.; Taylor, C.S.; Fricker, A.T.; Asare, E.; Tetali, S.S.; Haycock, J.W.; Roy, I. Polyhydroxyalkanoates and their advances for biomedical applications. Trends Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madbouly, S.A. Bio-based polyhydroxyalkanoates blends and composites. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, 1107–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Khan, M.T.; Moholkar, V.S. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs): Mechanistic Insights and Contributions to Sustainable Practices. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 1933–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffur, B.N.; Khadoo, P.; Kumar, G.; Surroop, D. Enhanced production, functionalization, and applications of polyhydroxyalkanoates from organic waste: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 302, 140358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, D.L.; Gonçalves, F.G.; Maffioletti, F.D.; Scatolino, M.V.; Soriano, J.; Protásio, T.d.P.; Lopez, Y.M.; Paes, J.B.; Mendes, L.M.; Junior, J.B.G.; et al. Particleboards based on agricultural and agroforestry wastes glued with vegetal polyurethane adhesive: An efficient and eco-friendly alternative. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulana, M.I.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Febrianto, F.; Hua, L.S.; Iswanto, A.H.; Antov, P.; Kristak, L.; Mardawati, E.; Sari, R.K.; Zaini, L.H.; et al. Environmentally Friendly Starch-Based Adhesives for Bonding High-Performance Wood Composites: A Review. Forests 2022, 13, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Lu, X.; Zhou, X.; Chrusciel, L.; Deng, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, S.; Brosse, N. Enhancement of mechanical strength of particleboard using environmentally friendly pine (Pinus pinaster L.) tannin adhesives with cellulose nanofibers. Ann. For. Sci. 2014, 72, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B. , Wu, D., Lin, Y., Xu, X., Xie, S., Zhao, G., & Wang, Y. Advances in Nanocellulose-Based Composites for Sustainable Food Packaging. BioResources 2025, 20.

- Wu, H.; Liao, D.; Chen, X.; Du, G.; Li, T.; Essawy, H.; Pizzi, A.; Zhou, X. Functionalized Natural Tannins For Preparation of a novel non-isocyanate polyurea-based adhesive. Polym. Test. 2022, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ren, B.; Ding, S.; Yan, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Cao, Y.; An, H.; Zeng, X.; Wang, B.; et al. Enhanced adhesion of novel biomass-based biomimetic adhesives using polyaspartamide derivative with lignin. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yammine, P.; El Safadi, A.; Kassab, R.; El-Nakat, H.; Obeid, P.J.; Nasr, Z.; Tannous, T.; Sari-Chmayssem, N.; Mansour, A.; Chmayssem, A. Types of Crosslinkers and Their Applications in Biomaterials and Biomembranes. Chemistry 2025, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.; González-García, S.; González-Rodríguez, S.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T. Cradle-to-gate Life Cycle Assessment of bio-adhesives for the wood panel industry. A comparison with petrochemical alternatives. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 738, 140357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irman, N.; Latif, N.H.A.; Brosse, N.; Gambier, F.; Syamani, F.A.; Hussin, M.H. Preparation and characterization of formaldehyde-free wood adhesive from mangrove bark tannin. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2022, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamidele, M.O.; Bamikale, M.B.; Cárdenas-Hernández, E.; Bamidele, M.A.; Castillo-Olvera, G.; Sandoval-Cortes, J.; Aguilar, C.N. Bioengineering in Solid-State Fermentation for next sustainable food bioprocessing. Next Sustain. 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayalath, P.; Ananthakrishnan, K.; Jeong, S.; Shibu, R.P.; Zhang, M.; Kumar, D.; Yoo, C.G.; Shamshina, J.L.; Therasme, O. Bio-Based Polyurethane Materials: Technical, Environmental, and Economic Insights. Processes 2025, 13, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Xu, P.; Yang, W.; Chu, H.; Wang, W.; Dong, W.; Chen, M.; Bai, H.; Ma, P. Soy protein-based adhesive with superior bonding strength and water resistance by designing densely crosslinking networks. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Patil, P.B.; Pinjari, D. Eco-friendly adhesives for wood panels: advances in lignin, tannin, protein, and rubber-based solutions. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2025, 39, 2628–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, S.; Fabbrizi, G.; Moya, A.J. Lignin from Plant-Based Agro-Industrial Biowastes: From Extraction to Sustainable Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Guillen, E.; Henn, K.A.; Österberg, M.; Dessbesell, L. Lignin’s role in the beginning of the end of the fossil resources era: A panorama of lignin supply, economic and market potential. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2025, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Rahman, F.; Das, A.K.; Hiziroglu, S. An overview of different types and potential of bio-based adhesives used for wood products. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2022, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.R.; May, M.; Panzera, T.H.; Scarpa, F.; Hiermaier, S. Reinforced biobased adhesive for eco-friendly sandwich panels. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2020, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Long, Y.; Huang, B.; Sun, C.; Kang, S.; Wang, Y. Technological innovations review in reducing formaldehyde emissions through adhesives and formaldehyde scavengers for building materials. Environ. Res. 2025, 273, 121242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Qin, C.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Jin, C. Preparation and Properties of Medium-Density Fiberboards Bonded with Vanillin Crosslinked Chitosan. Polymers 2023, 15, 2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawale, P.; Gadhave, S.; Gadhave, R.V. Environmentally Friendly Chitosan-Based Wood/Wood Composite Adhesive: Review. Green Sustain. Chem. 2023, 13, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Peng, Z.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, X.; Dong, Y. Unlocking the role of lignin for preparing the lignin-based wood adhesive: A review. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulana, S.; Wibowo, E.S.; Mardawati, E.; Iswanto, A.H.; Papadopoulos, A.; Lubis, M.A.R. Eco-Friendly and High-Performance Bio-Polyurethane Adhesives from Vegetable Oils: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BPF (2025). Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) - A Complete Guide to LCAs. British Plastic Federation. https://www.bpf.co.uk/sustainable_manufacturing/life-cycle-analysis-lca.aspx#:~:text=An%20LCA%20is%20a%20standardised,service%2C%20or%20the%20material).

- Salleh, K.M.; Hashim, R.; Sulaiman, O.; Hiziroglu, S.; Nadhari, W.N.A.W.; Karim, N.A.; Jumhuri, N.; Ang, L.Z.P. Evaluation of properties of starch-based adhesives and particleboard manufactured from them. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2014, 29, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, C.; Liu, Z.; Shi, S.Q.; Li, J.; Luo, J.; Gao, Q. A water-resistant and mildewproof soy protein adhesive enhanced by epoxidized xylitol. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Ling, J.; Mao, T.; Liu, F.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, G.; Xie, F. Adhesive and Flame-Retardant Properties of Starch/Ca2+ Gels with Different Amylose Contents. Molecules 2023, 28, 4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Cheng, Z.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Chu, F.; Xu, F.; Zhang, D. Fabrication of lignin based renewable dynamic networks and its applications as self-healing, antifungal and conductive adhesives. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahire, J.; Mousavi-Avval, S.; Rajendran, N.; Bergman, R.; Runge, T.; Jiang, C.; Hu, J. Techno-economic and life cycle analyses of bio-adhesives production from isolated soy protein and kraft lignin. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Pan, A.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y. A bio-based soy protein adhesive with high strength, toughness, and mildew resistance. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atamer, Z. Production and Physicochemical Properties of Casein-Based Adhesives. 20, 19. [CrossRef]

- La Torre, G.; Vitello, T.; Cocchiara, R.; Della Rocca, C. Relationship between formaldehyde exposure, respiratory irritant effects and cancers: a review of reviews. Public Heal. 2023, 218, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. DL (2025), U.S. U.S. DL (2025), U.S. Department of Labor. Hair Salons - Formaldehyde in Your Products. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Assessed 25. https://www.osha. 20 July.

- Li, J.; Ren, F.; Liu, X.; Chen, G.; Li, X.; Qing, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, M. Eco-friendly fiberboards with low formaldehyde content and enhanced mechanical properties produced with activated soybean protein isolate modified urea-formaldehyde resin. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savov, V.; Valchev, I.; Antov, P.; Yordanov, I.; Popski, Z. Effect of the Adhesive System on the Properties of Fiberboard Panels Bonded with Hydrolysis Lignin and Phenol-Formaldehyde Resin. Polymers 2022, 14, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanicream, (2025). Formaldehyde Releasers. What are they? https://www.vanicream.

- Salem, M.Z.M.; Böhm, M.; Barcík, Š.; Srba, J. Inter-laboratory comparison of formaldehyde emission from particleboard using ASTM D 6007-02 method. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2012, 70, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassannejad, H.; Shalbafan, A.; Rahmaninia, M. Reduction of formaldehyde emission from medium density fiberboard by chitosan as scavenger. J. Adhes. 2018, 96, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahri, S.; Yang, L.; Du, G.; Park, B.-D. Transition from formaldehyde-based wood adhesives to bio-based alternatives. BioResources 2025, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, D.; Bordado, J.M.; Marques, A.C.; dos Santos, R.G. Non-Formaldehyde, Bio-Based Adhesives for Use in Wood-Based Panel Manufacturing Industry—A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecochain (2023). Cradle-to-Gate in LCA. Definition, methods, Benefits. ISO 9001 and 27001 certified. https://ecochain. %93.

- Latimer, J. , Sengupta, A. & Dash, R. (2023). LCA Stages: The Four Stages of Life Cycle Assessment. VAAYU -Insight. https://www.vaayu.

- Mao, D.; Yang, S.; Ma, L.; Ma, W.; Yu, Z.; Xi, F.; Yu, J. Overview of life cycle assessment of recycling end-of-life photovoltaic panels: A case study of crystalline silicon photovoltaic panels. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvez, I.; Garcia, R.; Koubaa, A.; Landry, V.; Cloutier, A. Recent Advances in Bio-Based Adhesives and Formaldehyde-Free Technologies for Wood-Based Panel Manufacturing. Curr. For. Rep. 2024, 10, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Vázquez, R. Life-cycle assessment in mining and mineral processing: A bibliometric overview. Green Smart Min. Eng. 2025, 2, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tserpes, K.; Tzatzadakis, V. Life-Cycle Analysis and Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of a Bio-Based Structural Adhesive. Aerospace 2022, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peydayesh, M.; Bagnani, M.; Soon, W.L.; Mezzenga, R. Turning Food Protein Waste into Sustainable Technologies. Chem. Rev. 2022, 123, 2112–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnveden, G.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Ekvall, T.; Guinée, J.B.; Heijungs, R.; Hellweg, S.; Koehler, A.; Pennington, D.; Suh, S. Recent developments in Life Cycle Assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EC European Commission. Green Forum- Energy, Climate Change and Environment. Life Cycle Assessment: the scientific foundation of the Environmental Footprint methods. EC Directorate-General for Environment. (Assessed , 2025). https://green-forum.ec.europa. 12 August.

- Eisen, A.; Bussa, M.; Röder, H. A review of environmental assessments of biobased against petrochemical adhesives. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Jeong, B.; Park, B.-D. A Comparison of Adhesion Behavior of Urea-Formaldehyde Resins with Melamine-Urea-Formaldehyde Resins in Bonding Wood. Forests 2021, 12, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umoren, S. A. & Saji, V. S. (2022). Resin Based Polymer. Polymeric Material in Corrosion Inhibition. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/chemical-engineering/urea-formaldehyde-resins#:~:text=The%20most%20important%20amino%20resins%20are%20UF,their%20pure%2C%20modified%2C%20and%20integrated%20forms%20have.

- Ong, H.; Mahlia, T.; Masjuki, H.; Honnery, D. Life cycle cost and sensitivity analysis of palm biodiesel production. Fuel 2012, 98, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Rorrer, N.A.; Nicholson, S.R.; Erickson, E.; DesVeaux, J.S.; Avelino, A.F.; Lamers, P.; Bhatt, A.; Zhang, Y.; Avery, G.; et al. Techno-economic, life-cycle, and socioeconomic impact analysis of enzymatic recycling of poly(ethylene terephthalate). Joule 2021, 5, 2479–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEED (2025). LEED Rating System. LEED-certified green buildings are better buildings. https://www.usgbc.org/leed.

- NODA (2025) Green Premium, Brown Discounts: The Value of Sustainability in Real Estate. https://noda.

- Hiziruglo, S. (2018). Basics of Formaldehyde Emission from Wood Composite Panels. Okstate.edu. OSU Extension. https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/basics-of-formaldehyde-emission-from-wood-composite-panels.html#:~:text=Many%20studies%20were%20carried%20out,ppm%20and%200.

- OECD (2018). Environment Working Paper No. 134. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Economic valuation in formaldehyde regulation by Alistair Hunt and Nick Dale, University of Bath. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2018/06/economic-valuation-in-formaldehyde-regulation_3958877f/c0f8b8e5-en.

- RTI (1984). A Preliminary Assessment of the Benefits of Reducing Formaldehyde Exposures. Research Triangle Park. North Carolina 27709. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2017-09/documents/ee-0106_1-3_acc.

- NIH (1999). National Library of Medicine Toxicological Profile for Formaldehyde. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK597627/?utm_source=chatgpt.

- Smedley, J. Dick, F., Sadhra, S. (2013). OXFORD Handbook of Occupational Health. https://saude.ufpr.br/epmufpr/wp-content/uploads/sites/42/2020/07/Oxford-Handbook-of-Occupational-Health-2nd-Ed-2012.

- Muilu-Mäkelä, R. , Brännström, H., Weckroth, M., Kohl, J., Da Silva Viana, G., Diaz, M.,... & Yli-Hemminki, P. (2024). Valuable biochemicals of the future: The outlook for bio-based value-added chemicals and their growing markets. https://jukuri.luke. 8272. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez-Andrades, J. A. , García-Llamas, P., Taboada, Á., Estévez-Mauriz, L. (2023). Global Challenges for a Sustainable Society. EURECA-PRO. The European University for Responsible Consumption and Production. Springer Proceedings in Earth and Environmental Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Long, C. M. , Sax, S. N., & Lewis, A. S. Potential indoor air exposures and health risks from mercury off-gassing of coal combustion products used in building materials. Coal Combustion and Gasification Products 2012, 4, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Thetkathuek, A.; Yingratanasuk, T.; Ekburanawat, W.; Jaidee, W.; Sa-Ngiamsak, T. The risk factors for occupational contact dermatitis among workers in a medium density fiberboard furniture factory in Eastern Thailand. Arch. Environ. Occup. Heal. 2020, 76, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Lin, Q.; Rao, J.; Zeng, Q. Water resistances and bonding strengths of soy-based adhesives containing different carbohydrates. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 50, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frihart, C.R.; Hunt, C.G. Protein structure and wood adhesives. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2025, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalami, S.; Chen, N.; Borazjani, H.; Nejad, M. Comparative analysis of different lignins as phenol replacement in phenolic adhesive formulations. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018, 125, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeli, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Baniasadi, H.; Abidnejad, R.; Mujtaba, M.; Lipponen, J.; Seppälä, J.; Rojas, O.J. Lignin beyond the status quo: recent and emerging composite applications. Green Chem. 2023, 26, 593–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekhta, P. Recent Developments in Eco-Friendly Wood-Based Composites II. Polymers 2023, 15, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.M.; Harris, K.D.M. Some of tomorrow's catalysts for processing renewable and non-renewable feedstocks, diminishing anthropogenic carbon dioxide and increasing the production of energy. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 687–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intelligence, M. (2019). Global Carotenoid Market—Growth, Trends, and Forecast (2018–2023). Hyderabad, India. Carotenoids Market Growth, Size, Share, Trends and Forecast to 2025 (marketdataforecast.

- FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations F. A. O. (2001). State of the World’s forest. 151 p. FAO, Forestry Department, Rome, Italy. Fiber Futures. (2007). Leftover Straw Gets New Life. Available at http://www.sustainable-future.org/futurefibers/solutions.html#Anchor-Leftove-10496. (Accessed 25). 20 July.

- GWMI (2020). The international wood industry in one information service. Global Wood Markets Information. https://www.globalwoodmarketsinfo.

- FAO (2018). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Global Forest Products. Facts and Figures. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/80da7381-fc20-44bb-b0a0-7e8c35334a80/content#:~:text=Wood%2Dbased%20panel%20and%20sawnwood,and%20408%20million%20m%C2%B3%20respectively.

- IMARC (2019). Particle Board Market: Global Industry Trends, Share, Size, Growth, Opportunity and Forecast 2020-2025. https://www.imarcgroup.

- Mantanis, G. , & Berns, J. (2001, April). Strawboards bonded with urea formaldehyde resins. In 35th International Particleboard/Composite Materials Symposium Proceedings (pp. 137-144). Washington State University: Pullman, WA. http://mantanis.users.uth.gr/IC2001.pdf#:~:text=With%20the%20combined%20extruder%2Drefiner%20technology%2C%20the%20UF,figures%20close%20to%20particleboard%20and%20MDF%20standards.

- Dunky, M. (2017). Adhesives in the wood industry. In Handbook of adhesive technology (pp. 511-574). CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Athanassiadou, E. , Markessini, C. In and Tsiantzi, S. (2010). Producing panels with formaldehyde emission at wood level. In Proceedings of the 7th European Wood-Based Panel Symposium, European Panel Federation and Wilhelm Klauditz Institute, Hannover, Germany, 13–15 October 2010; pp. 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Athanassiadou, E. , Markessini, C. and Tsiantzi, S. (2015). Industrial amino adhesives satisfying stringent formaldehyde limits. In 2015 Melamine Conference, , Dubai, available at: http://www. chimarhellas.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/CHIMAR-HELLASDUBAI.pdf. 15–16 November.

- Tobisch, S. , Dunky, M., Hänsel, A., Krug, D., & Wenderdel, C. (2023). Survey of wood-based materials. In Springer Handbook of Wood Science and Technology (pp. 1211-1282). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, D. (2016). Additives in wood products-today and future development. In Environmental impacts of traditional and innovative forest-based Bioproducts (pp. 105-172). Singapore: Springer Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Andrew, J.J.; Sain, M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Jawaid, M.; Dhakal, H.N. Environmentally friendly fire retardant natural fibre composites: A review. Int. Mater. Rev. 2024, 69, 267–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadhari, W.N.A.W.; Ishak, N.S.; Danish, M.; Atan, S.; Mustapha, A.; Karim, N.A.; Hashim, R.; Sulaiman, O.; Yahaya, A.N.A. Mechanical and physical properties of binderless particleboard made from oil palm empty fruit bunch (OPEFB) with addition of natural binder. Mater. Today: Proc. 2020, 31, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, F.O.; Ahmed, A.; Imam, A.; Hassanin, H. Study on agricultural waste utilization in sustainable particleboard production.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 02007.

- Němec, M.; Prokůpek, L.; Obst, V.; Pipíška, T.; Král, P.; Hýsek, Š. Novel kraft-lignin-based adhesives for the production of particleboards. Compos. Struct. 2024, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, P.J.G.; Calegari, L.; Silva, W.A.d.M.; Gatto, D.A.; Neto, P.N.d.M.; de Melo, R.R.; Bakke, I.A.; Delucis, R.d.A.; Missio, A.L. Tannin-based extracts of Mimosa tenuiflora bark: features and prospecting as wood adhesives. Appl. Adhes. Sci. 2021, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesprini, E.; Causin, V.; De Iseppi, A.; Zanetti, M.; Marangon, M.; Barbu, M.C.; Tondi, G. Renewable Tannin-Based Adhesive from Quebracho Extract and Furfural for Particleboards. Forests 2022, 13, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainability Satellite (2025). Formaldehyde Emissions. Fundamentals. https://lifestyle.sustainability-directory.com/term/formaldehyde-emissions/#:~:text=The%20Lifestyle%20Connection%20%E2%86%92%20Our%20Homes%20as%20Ecosystems&text=The%20widespread%20use%20of%20composite,for%20a%20much%20longer%20period.

- Shasavari, A. , Karimi, A. , Akbari, M., & Alizadeh Noughani, M. Environmental impacts and social cost of non-renewable and renewable energy sources: a comprehensive review. Journal of Renewable Energy and Environment 2024, 11, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Q.; Mao, A.; Li, J. Toughening and Enhancing Melamine–Urea–Formaldehyde Resin Properties via in situ Polymerization of Dialdehyde Starch and Microphase Separation. Polymers 2019, 11, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kliase, S. & Heiderscheit, B. (2023). A sustainable tannin-citric acid wood adhesive with favorable bonding properties and water resistance. Southwest Forest University. SCISPACE. https://scispace.

- Guo, J.; Hu, H.; Zhang, K.; He, Y.; Guo, X. Revealing the Mechanical Properties of Emulsion Polymer Isocyanate Film in Humid Environments. Polymers 2018, 10, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawpan, M. A. (2020). Bio-polyurethane and Others. In Industrial Applications of Biopolymers and their Environmental Impact (pp. 272-291). CRC Press. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10. 1201. [Google Scholar]

- AC (2025). Adhesives Coatings. EPI Glue for Wood. https://www.adhesivesandcoatings.com/adhesives/furniture-and-home/epi-glue-for-wood/#:~:text=Emulsion%20polymer%20isocyanate%2C%20EPI%20glue%20for%20wood,as%20different%20emulsion%20and%20hardener%20combinations%20exist. 20 July.

- Pérez-De-Mora, A.; Madejón, E.; Cabrera, F.; Buegger, F.; Fuβ, R.; Pritsch, K.; Schloter, M. Long-term impact of acid resin waste deposits on soil quality of forest areas I. Contaminants and abiotic properties. Sci. Total. Environ. 2008, 406, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorieh, A.; Khan, A.; Selakjani, P.P.; Pizzi, A.; Hasankhah, A.; Meraj, M.; Pirouzram, O.; Abatari, M.N.; Movahed, S.G. Influence of wood leachate industrial waste as a novel catalyst for the synthesis of UF resins and MDF bonded with them. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2021, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troilo, S.; Besserer, A.; Rose, C.; Saker, S.; Soufflet, L.; Brosse, N. Urea-Formaldehyde Resin Removal in Medium-Density Fiberboards by Steam Explosion: Developing Nondestructive Analytical Tools. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 3603–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thetkathuek, A.; Yingratanasuk, T.; Ekburanawat, W. Respiratory Symptoms due to Occupational Exposure to Formaldehyde and MDF Dust in a MDF Furniture Factory in Eastern Thailand. Adv. Prev. Med. 2016, 2016, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, A.; Aerts, O. Contact allergy to and allergic contact dermatitis from formaldehyde and formaldehyde releasers: A clinical review and update. Contact Dermat. 2022, 87, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhil, U.V.; Radhika, N.; Saleh, B.; Krishna, S.A.; Noble, N.; Rajeshkumar, L. A comprehensive review on plant-based natural fiber reinforced polymer composites: Fabrication, properties, and applications. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 2598–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faheem, M.; Khan, K.A. Harnessing sustainable biocomposites: a review of advances in greener materials and manufacturing strategies. Polym. Bull. 2025, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abtew, M.A.; Atalie, D.; Dejene, B.K. Recycling of cotton textile waste: Technological process, applications, and sustainability within a circular economy. J. Ind. Text. 2025, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.C.; Mocanu, A.; Tomić, N.Z.; Balos, S.; Stammen, E.; Lundevall, A.; Abrahami, S.T.; Günther, R.; de Kok, J.M.M.; de Freitas, S.T. Review on Adhesives and Surface Treatments for Structural Applications: Recent Developments on Sustainability and Implementation for Metal and Composite Substrates. Materials 2020, 13, 5590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasche, C. (2020). Exploring the sustainability potential of an algae-based wood adhesive: Comparative and explorative environmental life cycle assessment of algae-vs. formaldehyde-based adhesives for particleboard production.

- Madrid, M. , Turunen, J., & Seitz, W. (2023). General industrial adhesive applications: Qualification, specification, quality control, and risk mitigation. In Advances in Structural Adhesive Bonding (pp. 849-876). Woodhead Publishing. [CrossRef]

- A Pethrick, R. Design and ageing of adhesives for structural adhesive bonding – A review. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L: J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2014, 229, 349–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, K. M. , Zuber, M., & Ali, M. (Eds.). (2017). Algae based polymers, blends, and composites: chemistry, biotechnology and materials science. Elsevier. https://books.google.com.br/books?

- Rabl, A.; Holland, M. Environmental Assessment Framework for Policy Applications: Life Cycle Assessment, External Costs and Multi-criteria Analysis. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2008, 51, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, S. , Reale, F., Cristobal-Garcia, J., Marelli, L., & Pant, R. Life cycle assessment for the impact assessment of policies. Report EUR 2016, 28380. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Serenella-Sala/publication/312384681_Life_cycle_assessment_for_the_impact_assessment_of_policies/links/587cf57908aed3826aefffd4/Life-cycle-assessment-for-the-impact-assessment-of-policies.

- Shan, C.; Ji, X. Environmental Regulation and Green Technology Innovation: An Analysis of the Government Subsidy Policy's Role in Driving Corporate Green Transformation. Ind. Eng. Innov. Manag. 2024, 7, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, H. H. (2025). Government Initiatives. In Circular Economy Opportunities and Pathways for Manufacturers: Manufacturing Renewed (pp. 33-59). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- Brenton, P.; Edwards-Jones, G.; Jensen, M.F. Carbon Labelling and Low-income Country Exports: A Review of the Development Issues. Dev. Policy Rev. 2009, 27, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, C. , Briner, G., & Karousakis, K. (2010). Low-emission development strategies (LEDS): Technical, institutional and policy lessons. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2010/11/low-emission-development-strategies-leds_g17a22f6/5k451mzrnt37-en.

- Boltze, J.; Wagner, D.-C.; Barthel, H.; Gounis, M.J. Academic-industry Collaborations in Translational Stroke Research. Transl. Stroke Res. 2016, 7, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PB Premium Bond (Assessed , 2025). Best Adhesive for Aluminum Composite Panel; Composite Panel Adhesive. https://premiumbond. 09 June.

- Gibbons, L. (2016). What adhesive types are best for bonding composite? Permabond. Engineering Adhesive. https://permabond.

- Wang, W.; Shen, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, D. CHARACTERIZATION OF AROMATIC FIBERBOARDS. Wood Res. 2021, 66, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirmohammadi, M. , & Leggate, W. (2022). Review of Existing Methods for Evaluating Adhesive Bonds in. Engineered Wood Products for Construction, 141. https://books.google.com.br/books?hl=en&lr=&id=GNJuEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA141&dq=Cyanoacrylate/instant+adhesive+fiberboards&ots=OH-eqHjpFJ&sig=2PvyOSP1gtMbMYT9ZbSpSIii26c&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Taghiyari, H.R.; Karimi, A.; Tahir, P.M. Organo-silane compounds in medium density fiberboard: physical and mechanical properties. J. For. Res. 2015, 26, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuryawan, A.; Sutiawan, J.; Utomo, B.T.; Risnasari, I.; Karolina, R.; Masruchin, N. Panel products made of oil palm trunk bagasse (OPTB) and MMA (Methyl methacrylate)-styrofoam binder. Glob. For. J. 2023, 1, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SGE (2024). Technology that connects-Hybrid adhesives as a key to successful installations. SELENA Global Experience https://selena.com/en/technology-that-connects-hybrid-adhesives-as-a-key-to-successful-installation/#:~:text=Then%20take%20into%20account%20the%20conditions%20that,requirements%20regarding%20curing%20time%20and%20bond%20strength.

- FEICA (2023-2028) European Adhesives & Sealants Market 2023-2028, report prepared by Smithers for FEICA; The European Adhesives & Sealants Market Report 2023-2028 – A quantitative demand analysis and trend forecast : Feica.

- Sánchez-Arreola, E.; Martin-Torres, G.; Lozada-Ramírez, J.D.; Hernández, L.R.; Bandala-González, E.R.; Bach, H. Biodiesel production and de-oiled seed cake nutritional values of a Mexican edible Jatropha curcas. Renew. Energy 2015, 76, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N° | Review phases | Critical activities performed |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identification of the review research question | Consultation with Review Group members to develop and refine the review research question |

| 2 | Developing inclusion/exclusion criteria | Developing inclusion and exclusion criteria to enable decisions to be made about which studies are to be included in the review |

| 3 | Producing the protocol for the review | Producing an overall plan for the review, describing what will happen in each of the phases |

| 4 | Searching | Search of literature for potentially relevant reports of research studies, to include electronic searching, hand searching, and personal contacts |

| 5 | Screening | Applying inclusion and exclusion criteria to potentially relevant studies |

| 6 | Keywording | Applying adhesives in fiberboard production core keywords, and review-specific keywords to include studies to characterize their main contents |

| 7 | Producing the systematic map | Using keywords to generate a systematic map of the area that summarizes the work that has been undertaken |

| 8 | Identifying the in-depth review question | Consultation with Review Group members to identify area(s) of the map to explore in detail, and develop the in-depth research review question |

| 9 | Data extraction | Extracting the key data from studies included in the in-depth review, including reaching judgements about quality |

| 10 | Producing the report | Writing up the research review in a specified format |

| 11 | Dissemination | Publicizing the findings of the review, including the production of summaries by users |

| Adhesive types | Internal bond strength (MPa) | Dimensional stability | Formaldehyde emission |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soy-based | 0.60-0.85 | Moderate | Near zero |

| Tannin-based | 0.68-0.92 | Excellent | Near zero |

| Lignin-based | 0.70-0.95 | Good | Very low |

| Starch-based | 0.65-0.90 | Moderate | Low |

| Urea formaldehyde | 0.75-1.00 | Moderate | High |

| Adhesive type | Source / Composition | Bond strength (Internal bond, MPa) | Water moisture resistance | Formaldehyde emission | Industrial readiness / Application | Key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urea Formaldehyde (UF) | Synthetic adhesive | 0.75-1.00 | Moderate | High | Widely used, standard in fiberboard | Gao et al., [107]; Nadhari et al., [163]. |

| Starch-based | Corn, potato, cassava, wheat, oil palm | 0.65-0.90 | Moderate | Low | Pilot and lab-scale, some commercial MDF applications | Nadhari et al., [163] ; Okeke et al., [164] |

| Lignin-based | Wood or industrial byproducts | 0.70-0.95 | Good | Very low | Pilot and niche commercial applications | Gao et al., [107]; Němec et al., [165] |

| Tannin-based | Quebracho mimosa, Cashew residue extracts. | 0.68-0.92 | Excellent | Near zero | Small-scale commercial particleboards and MDF | Lopes et al., [166] |

| Soya/Protein-based | Soy, casein | 0.60-0.85 | Moderate | Near zero | Limited commercial adoption, ongoing research | Li et al., [113] |

| Hybrid bio-based adhesive | Starch lignin, tannin, furfural blends | 0.70-0.95 | Good-Excellent | Near zero | Pilot industrial trial; scalable potential | Cesprini et al., [167]; Mensah et al., [167] |

| Synthetic formaldehyde-free adhesive | Bio-derived monomers | 0.75-1.00 | Good | Near zero | Ready for industrial adoption; emerging markets | Kumar et al., [93] |

| Adhesive Categories | Characterization | Key references |

|---|---|---|

| Protein-Based Adhesives |

Soy protein is the most extensively studied bio-adhesive. Denaturation and crosslinking enhance internal bonding (IB) strength (0.6-0.9 MPa), but water resistance remains lower than that of UF. Commercial trials (e.g., Columbia Forest Products) demonstrate industrial viability in non-structural panels. Other proteins (blood meal, casein, egg albumin) show promising adhesion but lack scalability. | Li et al., [86]; Zhang et al., [105]; Xu et al., [109] |

| Tannin-Based Adhesives |

Tannin-citric acid (TCA) adhesives achieve IB values >0.8 MPa and reduced WA/TS compared to starch-based adhesives. Pilot studies demonstrate durability comparable to phenol formaldehyde (PF) adhesives, without the use of toxic reagents. Extracted mainly from mimosa and quebracho bark; scalability linked to forestry residues. |

Kumar et al., [93] ; Li et al., [65]; Kliase & Heiderscheit, [171]; |

| Lignin-Based Adhesives |

Lignin substitution for phenol in PF resins has reached up to 50% replacement without significant loss of performance. Modified lignins (phenolated, methylolated) show enhanced reactivity. Challenges: heterogeneity of industrial lignin and higher curing temperatures |

Li et al., [46]; Li et al., [65]; Zhao et al., [61] |

| Polysaccharide-Based Adhesives | Starch-based adhesives remain hydrophilic; however, oxidation or esterification can improve performance. IB ~0.5–0.7 MPa reported, still below UF benchmarks. Chitosan adhesives offer antimicrobial benefits, but are restricted by high costs |

Watcharakitti et al., [35]; Maulana et al., [82]; Liu et al., [106] |

| Hybrid and Low-Emission Synthetic Systems | Emulsion polymer isocyanate (EPI) and bio-polyurethane systems combine bio-based polyols with petrochemicals, achieving high IB values (>1 MPa) and excellent water resistance. However, partial reliance on fossil inputs reduces sustainability. | Guo et al., [172]; Sawpan, [173]; AC, [174]; |

| Adhesives | Characteristics | Utilization | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oil palm starch | highest internal-bonding strength | Bond rubberwood particleboard | Salleh et al., [104] |

| Wheat starch | Good internal bonding strength, but requires additive enhancement. | Bond rubberwood particleboard, rice husks | Salleh et al., [104] |

| Soybean protein | Bonding strengths have exceeded commercial UF adhesives | Production of plywood, blockboard, and engineering flooring substrates | Xu et al., [109] |

| Acrylated epoxidized soybean oil (AESO) | Superior mechanical properties, water resistance, and high-temperature resistance | Bamboo particleboards | Zhang et al. [105] |

| Palm-oil-based dimethacrylate | Superior mechanical properties, water resistance, and high-temperature resistance | Bamboo particleboards | Zhang et al. [105] |

| Gum Arabic | Particleboard is recommended to be used for construction to eliminate the health hazards resulting from high formaldehyde emissions from urea formaldehyde resin-based particleboards | Macadamia nutshells, rice husk, sawdust. | Suleiman et al., [201] |

| melamine-, phenol-, Urea- formaldehyde | Acceptable mechanical and physical properties performance, strong bonding performance | Strawboards and non-wood-based particleboard | Mantanis & Berns, [21] |

| Epoxy | Heat-curable single composite. Provide high-strength bonds to many composite materials | Fiber composite industry | Ashori et al. [70] ; Gibbons, [196] |

| Structural acrylic | Form very high-strength bonds to a composite that has high peel strength, providing gap-filling properties | Ideal for bonding of rough surfaces. High fiber-content composite | Gibbons, [196], Wang et al., [197] |

| Cyanoacrylate/instant adhesive | Create strong bonds very quickly in applications that don’t require high impact or peel resistance | Can be used in place of clamps or jigs to hold the assembly in place while a longer curing two-component adhesive bonds | Gibbons [196]; Shirmohammadi & Leggate, [198] |

| UV curable | Inkjet coating on the substrate surface to bond the composite to clear glass or plastic | They also coat composites, wood-based substrates, and MDF | Zhang et al. [24] ; Henke et al. [206]; |

| MS polymer | Reduce water absorption (WA) and thickness swelling in fiberboards | Wood fibers, Agro-Forest residues, Kenaf fiber | Taghiyari et al. [199] |

| Methyl methacrylate | high strength and water resistance. | Rice straw and natural wood particles, oil palm trunk bagasse | Nuryawan et al., [200]; Mas' Ud et al., [207] |

| Polyurethane | Bond fiber well in exhibiting high-performance properties performance | Wood and other non-wood fibers | Seychal, [17] ; Aristri et al., [50]; Maulana et al., [102]; |

| Urethane | Excellent impact resistance and good adhesion to most plastics | Bonds well to woods, concrete, and rubber with reduced resistance to solvents and high temperatures | 3M A, [204] |

| Cassava starch | Excellent static bending strength, hardness, and internal bond | Bonds banana fiberboard, Ceiba pentandra, Cocoa stem, Elephant grass particleboards | Mensah et al., [66]; Mensah et al., [67] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).