1. Introduction

Wood adhesives play a crucial role in wood processing industry. The most widely used wood adhesives are formaldehyde-based resin adhesives, including phenolic resin, urea-formaldehyde resin, and melamine-formaldehyde resin, which account for over 90% of the market share in the industry [

1]. However, formaldehyde-based resin adhesives release free formaldehyde, which poses health risks, with another shortcoming that their production relies on non-renewable petroleum resources. With the tightening of environmental regulations and the increase in consumer environmental awareness, eco-friendly biomass wood adhesives have developed rapidly [

2]. Examples include lignin-based adhesives, tannin-based adhesives, and soy protein-based adhesives.

Lignin is the second largest biomass resource in the world. The total annual production of natural lignin can reach 1.5 × 10¹¹ tons, while the by-products of industrial lignin produced annually in the pulp and paper industries can reach 6 × 10¹⁰ tons [

3]. However, the utilization rate of lignin is currently low, with only a small portion being effectively utilized. Lignin is a high-molecular-weight compound with a three-dimensional polyphenolic network structure, making it the largest biomass alternative to petroleum-based aromatic materials. Additionally, lignin plays a role in plant cell structures by linking cellulose and hemicellulose to support the cell wall, thus imparting certain adhesive properties and strength. Due to its structural characteristics, lignin has great potential as an adhesive [

4]. However, lignin-based adhesives face challenges such as poor water resistance, low bonding strength, and short storage life, which significantly limits their applications. Many researchers are using lignin either partially or entirely as a substitute for fossil-based materials to address the formaldehyde emissions associated with phenol-formaldehyde resins in adhesives. Sarkar et al. [

5] used dealkalized lignin to replace 50% of phenol in phenol-formaldehyde resins, resulting in lignin-modified phenol-formaldehyde resins (LPF) with adhesive performance reaching 78% of pure phenol-formaldehyde resin. Sudan et al. [

6], after alkali-based phenolation modification of lignin extracted from black liquor, were able to replace 60% of phenol, producing high-performance LPF resin. Bornstein et al. [

7] heated lignin extracted from sulfite pulp waste liquor with formaldehyde under alkaline conditions, then added a small amount of melamine to produce a water-resistant wood adhesive. The adhesive contained up to 70% lignosulfonate, and significantly reduced the emission of free formaldehyde. These studies indeed demonstrated the strategy of using lignin to modify formaldehyde-based resin adhesives, which is not only more environmentally friendly and efficient but also established important foundations for the development of new bio-based adhesives. The use of lignin to modify formaldehyde-based adhesives can actually improve the bonding performance and reduce some formaldehyde emissions. However, it still requires the use of formaldehyde and does not fundamentally solve the formaldehyde emission problem. Therefore, many researchers explored the potential use of petroleum-based aldehydes such as propionaldehyde [

8], glutaraldehyde [

9], and glyoxal [

10] to replace formaldehyde. Comparatively, ethylene glycol has lower toxicity[

11]. Also, using some non-toxic, green biomass aldehydes as alternatives to formaldehyde in adhesives preparation helps mitigate the issue of formaldehyde emission currently faced. Some studies focused on the use of lignin to replace a part of the phenol and then completely substituted formaldehyde with ethylene glycol in adhesives preparation. This approach resulted in adhesives exhibiting higher bonding performance than PF resin adhesives [

12,

13]. Furthermore, adding petroleum-based cross-linking agents to lignin-ethylene glycol resin was reported to enhance the adhesive's bonding strength [

7,

8]. There are also studies [

14] on adding hexamethylenetetramine as hardener to lignin-ethylene glycol resin, to cause improving of the adhesives dry shear strength up to 1.40 MPa. However, these cross-linking modifiers are expensive, leading to high production costs and limited economic benefits. Additionally, they still contain toxic substances. To address these issues, many groups opted to use furfural, lignin derivatives (such as hydroxybenzaldehydes, vanillin, syringaldehyde, and eugenol), as well as some non-toxic, green biomass aldehydes like sugar aldehydes, all of which can substitute formaldehyde in adhesive formulations. Zhang [

15] and Dongre [

16], among others, utilized hydrolyzed lignin and hydroxymethyl furfural to prepare lignin-furfural adhesives, achieving a high yield of 85%. Its functional groups and curing mechanism are similar to phenol-formaldehyde resins. Moreover, it showed a larger molecular weight, broader molecular weight distribution, and higher glass transition temperature, storage modulus, and tensile strength compared to phenol-formaldehyde resins. Compared to PF adhesives, the curing of lignin-furfural adhesives required higher curing temperatures and long curing times. Therefore, lignin-furfural adhesives still cannot meet the industrial requirements in relation to the curing speed and temperature. Furthermore, to enhance the lignin activity, phenol pretreatment of lignin is sometimes an option, but this approach does not fully achieve the greenification of adhesives.

Natural green sugar-based materials such as starch, sucrose, glucose, and cellulose are widely utilized for their sustainability and high biodegradability, especially in the bio-materials field, serving as an excellent feed-stock for sugar based aldehydes. In a previous research work belonging to our group, oxidized sucrose-lignin adhesive was prepared by achieving cross-linking between the oxidized sucrose with lignin. After immersing the adhesive-bonded three-layer plywood in hot water at 63 ± 3°C for 3 hours, the shear strength reached 1.42 MPa. In addition, the shear strength of the plywood samples after immersion in boiling water for 3 hours achieved 1.03 MPa. This approach replaces formaldehyde with oxidized sucrose, addressing the issue of toxic formaldehyde emissions while maintaining excellent performance.

Starch is an abundant, inexpensive natural polymer [

17,

18,

19,

20]. However, it has low reactivity and typically requires chemical or physical modification for optimal application. It consists of two main components: amylose and amylopectin [

21]. The ratio of amylose to amylopectin significantly affects the physical and chemical properties of starch and its applications [

22]. Some studies explained that starch with higher amylose content often produces harder gels and more robust films [

23]. Therefore, the current study will focus on utilization of soluble amylose-rich starch as a raw material for preparation of bio-aldehydes.

The high functionalization of starch is related to its abundant hydroxyl groups on the molecular chains of sugar-based backbone, which can be easily chemically modified. Among suggested modifications, oxidation is one of the most common chemical treatments. After oxidation, the hydroxyl groups on starch molecules can directly upgrade to carbonyl or carboxyl groups along the molecular structure on the pretext that the hydroxyl groups at positions C2, C3, and C6 of the molecular structure of sugar-based materials are the most susceptible sites for oxidation agents to attack. Sugar-based materials can undergo oxidation using strong oxidizing agents such as potassium permanganate, potassium dichromate, and nitric acid, to result in aldehyde and carboxylic acid compounds. However, this process can also cause significant structural damage of the sugars [

24,

25]. Persulfates are inexpensive and relatively mild oxidizing agents, which can break the glycosidic bonds in the starch molecular structures [

26], leading to oxidation of the hydroxyl groups at positions 2 and 3 to aldehydes [

18]. Furthermore, under heating conditions, persulfates can easily undergo hydrolysis in aqueous solutions to produce hydrogen peroxide and persulfate ions. They can also degrade the amorphous regions of lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose, thereby facilitating the involvement of lignin macromolecular chains in many reactions. Compared to other oxidizing agents, persulfates offer greater advantages in lignin-based adhesives [

27]. Therefore, in this study, ammonium persulfate (APS) was chosen as the oxidizing agent to oxidize the active hydroxyl groups in starch molecules, aiming to obtain biomass aldehydes; The aldehyde groups can react with the active hydrogen atoms on the phenolic rings of lignin molecules to form lignin-based adhesives with excellent water resistance. Therefore, FT-IR and XPS techniques are employed to confirm the formation of aldehyde groups in the oxidized starch products so that to ensure the liability for potential reactions between the oxidized starch and lignin; Finally, this study also investigates the effects of oxidation time, oxidizing agent dosage, and the starch-to-lignin mass ratio on the adhesive bonding performance of OSTL.

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Materials

Poplar veneer with a moisture content of 8%–10% was sourced from the local wood market. Sodium lignosulfonate was provided by Hefei Gansheng Biotechnology Co., LTD., China. Soluble starch was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., LTD., China. Ammonium persulfate (APS) was supplied from Tianjin Kemi Chemical Reagent Co., LTD., China. Potassium bromide (KBr) was provided from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., LTD., China. Distilled water was prepared in the laboratory.

2.2. Preparation of Biodegradable Aldehyde via Oxidation of Starch

At a temperature of 60°C, a certain mass ratio of starch was added into a three-neck flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer to prepare a 50 wt% aqueous solution of starch. After the starch was fully and evenly homogenized, a certain amount of ammonium persulfate ((NH4)2S2O8) as oxidizing agent was charged and stirred for a certain period of time. After the reaction is complete, filter a portion was exposed to freeze-drying to obtain the oxidized starch (OST) in powder form, while storing the remaining OST liquid in the refrigerator for subsequent analysis and use.

2.3. Preparation of Oxidized Starch-Lignin (OSTL) Adhesive

A certain amount of lignin was added to the OST and stirred thoroughly to ensure that the solid content of the OSTL adhesive reached 50%. Then, the temperature of the water bath was raised to 90°C and the reaction continued for 1 hour. The reaction mixture was then cooled to room temperature to obtain the OSTL adhesive. In order to investigate the effect of other reaction variables, different oxidation times (0 h, 3 h, 6 h, 9 h, 12 h) were employed. Furthermore, different amounts of the oxidizing agent (9%, 11%, 13%, 15%, and 17% based on the starch mass) were made the variable while keeping a reaction time of 6 hours at 60°C constant parameters to check the effect on the properties of the resulting OSTL adhesive. In addition, different mass ratios of the oxidized starch to lignin were set at 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, and 1.2, to explore the effect on the properties of the adhesive.

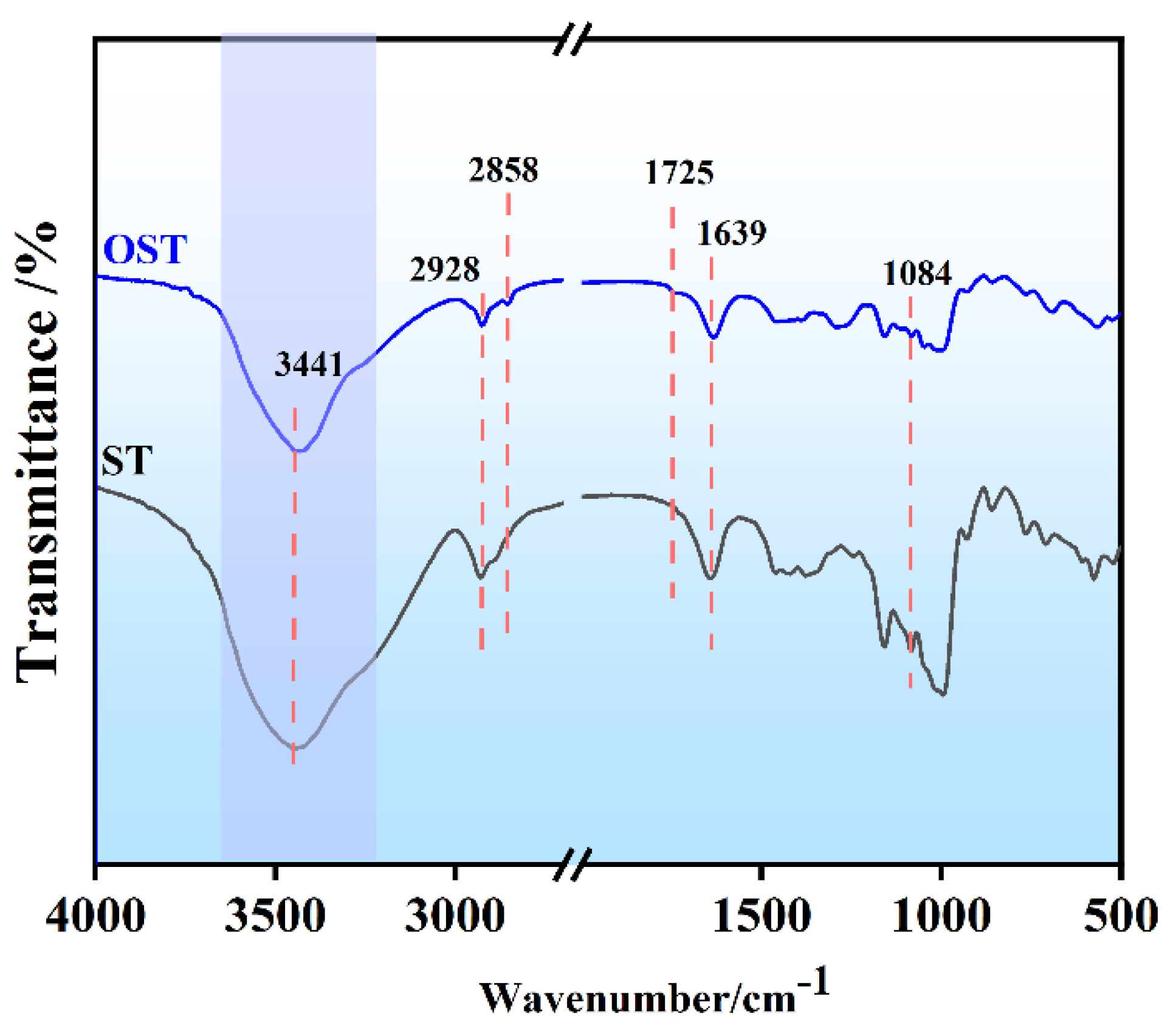

2.4. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy Investigation

The uncured adhesive sample was dried in a freez-dryer while the cured adhesive sample was dried in an oven at 200°C, then each was mixed uniformly with potassium bromide in 1:200 ratio and pressed into pellets. Then, the background interference was removed during scanning the samples using Nicolet 670 spectrometer over the wavenumber range of 4000 cm-1 to 400 cm-1 for a total of 32 scans with a resolution of 4 cm-1.

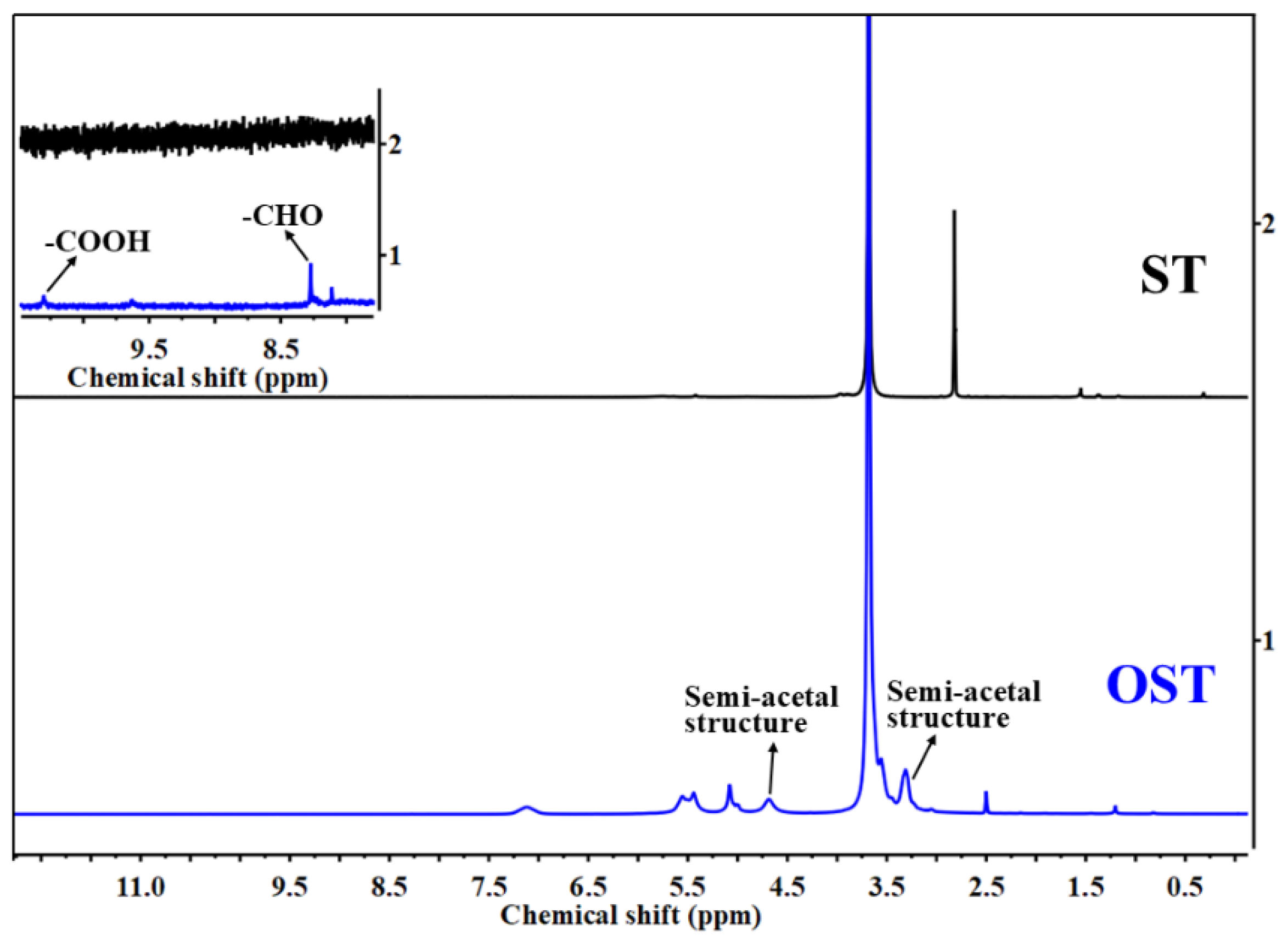

2.5. Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H-NMR) Investigation

The freeze-dried adhesive was dissolved in deuterium oxide (D2O). The proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectrum was collected for the sample using AVANCE NEO 500 spectrometer (Bruker Corporation, Switzerland). The standard "zg3D" Bruker pulse sequence was applied for recording while a frequency of 500 MHz was operated with 65536 data points collected over 16 scans. The relaxation delay was set to 3.28 seconds, and the chemical shifts were referenced relative to the deuterated solvent (D2O).

2.6. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Investigation

Using Al Kα excitation as a radiation source with an excitation energy of 1486.6 eV, the adhesive samples were examined before and after curing using the Thermo Scientific K-alpha XPS spectrometer. Charge correction was applied with respect to the binding energy of C 1s at 284.8 eV.

2.7. Evaluation of Three-Layer Plywood Samples

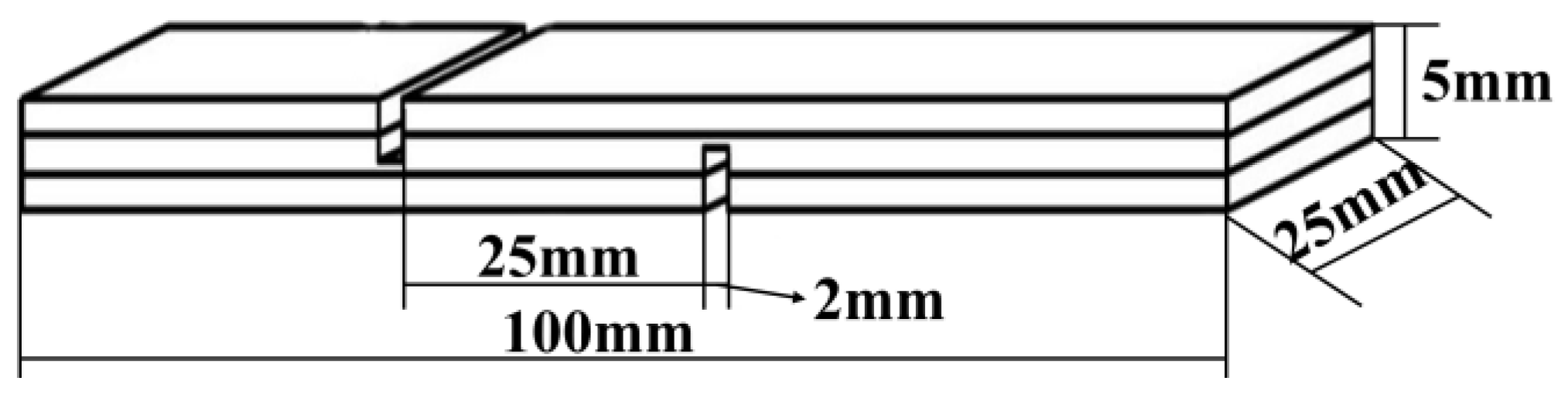

Three-layer plywood was prepared using poplar veneers with dimensions of 180 mm × 110 mm × 2 mm for each layer. The adhesive was applied on the surface of the specimen with a glue amount of 300 g/m², and the pressing time was 10–15 min.. After which, the plywood samples were pressed using a press machine that was purchased from Kunshan Rugong Precision Instrument Co., LTD, China, at different hot-pressing temperatures: 160°C, 170°C, 180°C, 190°C, and 200°C, with a unit pressure of 1 MPa, and a pressing time of 5 minutes. The obtained plywood samples were allowed to acclimate at room temperature for at least 24 hours. Following this, the plywood samples were cut into standard test specimens as shown in

Figure 1 according to the testing requirements specified in the national standard GB/T 17657-2022 for plywood bonding strength. According to the national standard GB/T 17657-2022, the testing for dry shear strength, 24-hours cold water soaking strength (20±3°C), 3-hours hot water soaking strength (63±3°C) was conducted to assess the plywood's resistance to boiling water. Additional 3 hours of testing soaking strength The values for each set of bonding strength evaluation are the averages of 6 measurements.

2.8. Estimation of the Hydrolysis Residue Weight of the Cured Adhesive

After curing of the adhesive samples in a high-temperature oven at 200±3°C, the samples were ground into 100-mesh powder. The adhesive powder was wrapped using a filter paper and immersed in water at 63±3°C. After 3 hours of hydrolysis, it was dried to constant weight in an oven at 120±2°C. The residual ratio of the adhesive based on the mass ratio before and after hydrolysis was calculated according to the following formula:

where

mass of cured adhesive before immersion;

: mass of the cured adhesive after immersion.

2.9. Antifungal Performance of the Adhesive

The antifungal activity was evaluated following a method described in the literature[112], where the starch sample (raw, OST , and OSTL ) was prepared into 50% solution, and each solution was placed in a petri dish at room temperature and 90% humidity. The samples were observed at different time intervals for any sign of fungal growth or degradation.

2.10. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Investigation

Test the adhesive samples were tested using NETZSCH DSC204F1 differential scanning calorimeter under a flowing nitrogen gas from 35°C to 250°C at a heating increment rate of 10°C/min.

2.11. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) Investigation

poplar veneer specimens were cut with the grain into small pieces measuring 50 mm × 10 mm × 2 mm each. The adhesive was applied evenly to one piece of wood, with a glue amount of 300 g/m². Then, another piece of wood was placed on the top and the specimens were allowed to rest for 15 minutes. The specimens were tested in a three-point bending mode at a heating rate of 5 K/min, from 35°C to 300°C, with a frequency of 20 Hz, and dynamic force of 2 N using DMA-242 analyzer, NETZSCH, Germany, and the results were recorded and processed using Proteus analysis software.

2.12. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

The cured OSTL adhesive was subjected to thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) using Netzsch STA 2500 , TA Instruments, Germany. A temperature range from 30°C to 800 °C was scanned at a heating rate of 10 K/min.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram revealing the dimensions used for three-ply plywood preparation for shear strength testing.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram revealing the dimensions used for three-ply plywood preparation for shear strength testing.

Figure 2.

FT-IR spectra of starch (ST) and oxidized starch (OST).

Figure 2.

FT-IR spectra of starch (ST) and oxidized starch (OST).

Figure 3.

1H-NMR spectra of starch (ST) and oxidized starch (OST).

Figure 3.

1H-NMR spectra of starch (ST) and oxidized starch (OST).

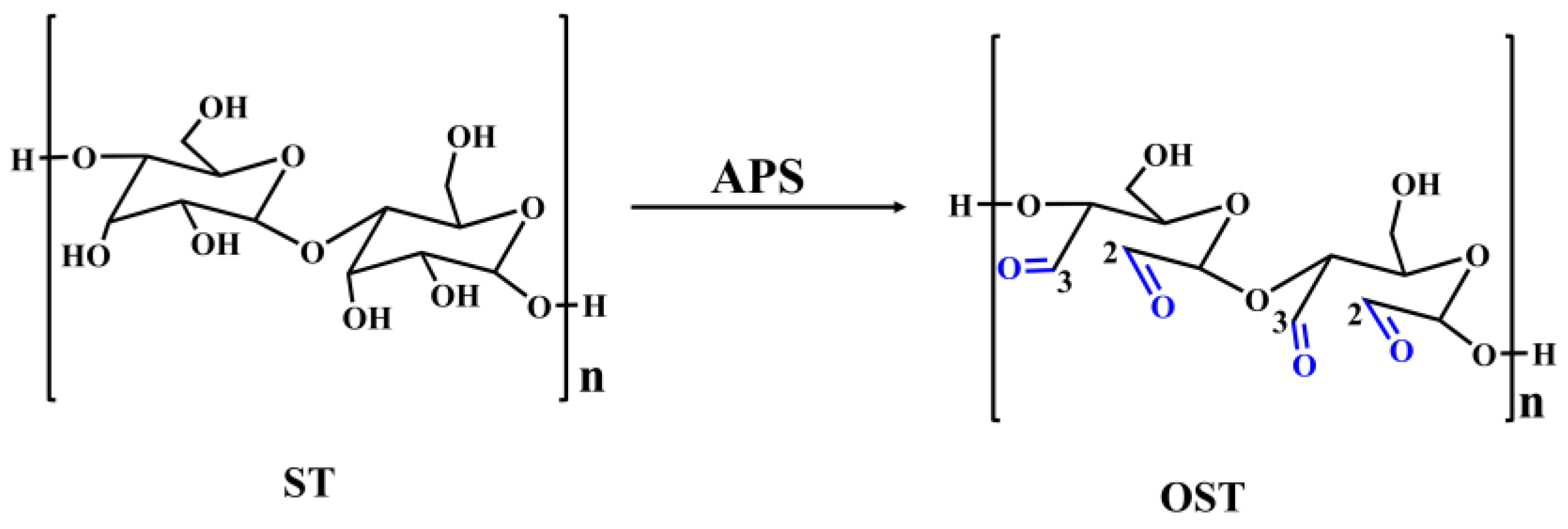

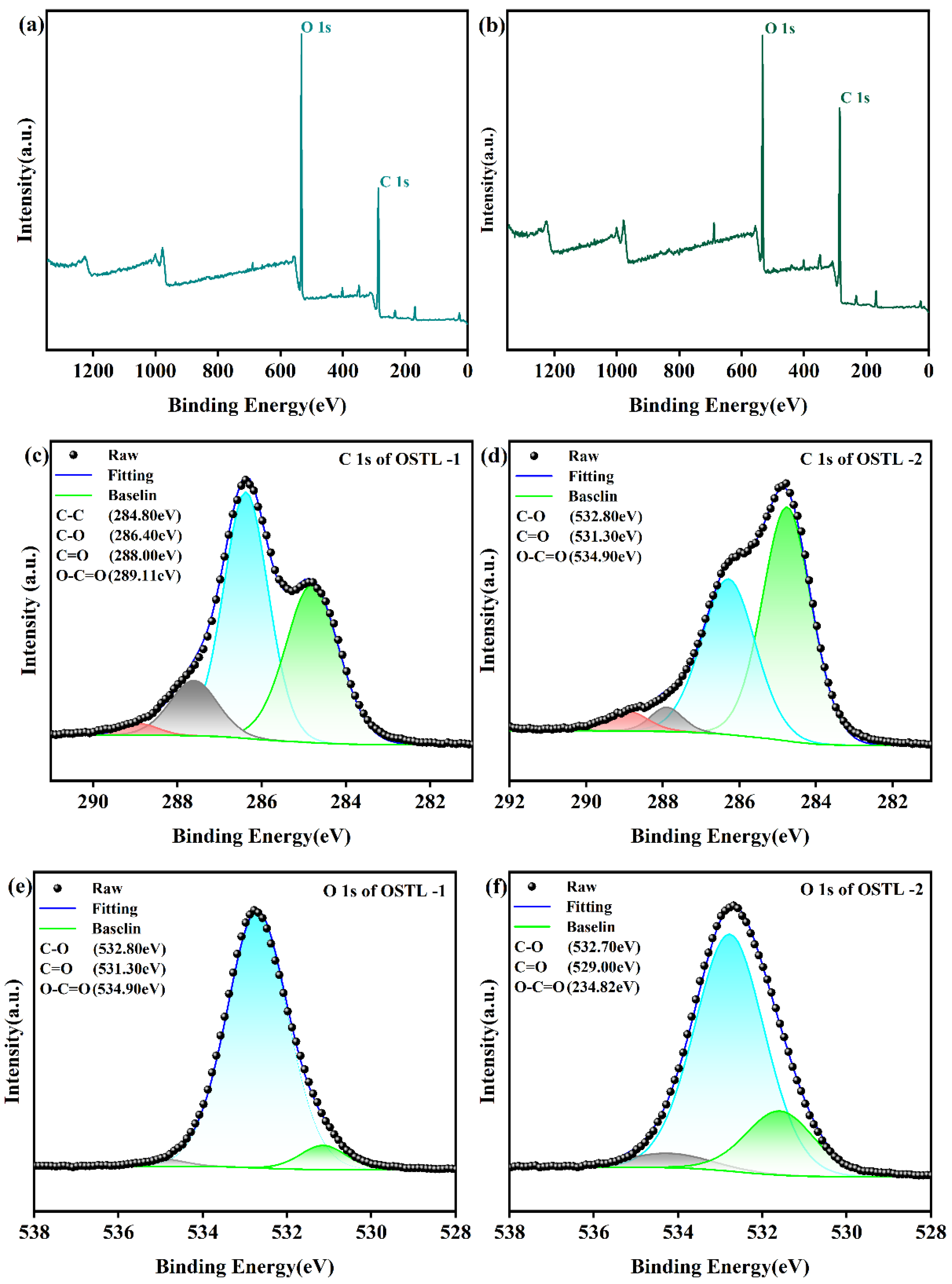

Figure 4.

XPS spectra of ST and OST. (a) XPS full measurement spectra of ST; (b) XPS full measurement spectra of OST; (c) High-resolution C 1s spectrum of ST; (d) High-resolution C 1s spectrum of OST.

Figure 4.

XPS spectra of ST and OST. (a) XPS full measurement spectra of ST; (b) XPS full measurement spectra of OST; (c) High-resolution C 1s spectrum of ST; (d) High-resolution C 1s spectrum of OST.

Figure 5.

The process of oxidizing ST to generate OST using APS as oxidizing agent.

Figure 5.

The process of oxidizing ST to generate OST using APS as oxidizing agent.

Figure 6.

(a) FT-IR spectra of OST, lignin (L), OSTL-1 (uncured resin adhesive), and OSTL-2 (cured resin adhesive).

Figure 6.

(a) FT-IR spectra of OST, lignin (L), OSTL-1 (uncured resin adhesive), and OSTL-2 (cured resin adhesive).

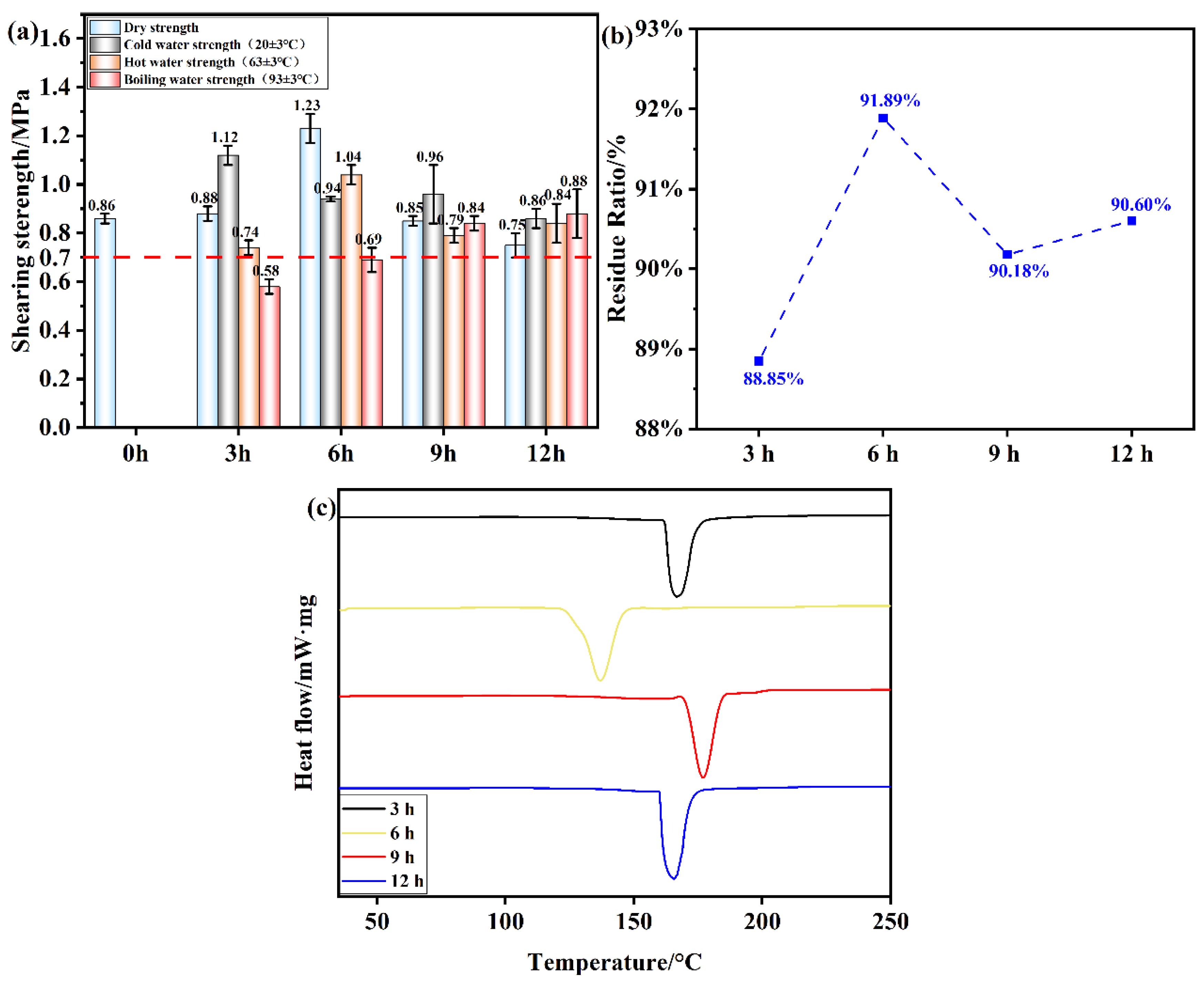

Figure 7.

XPS spectra of OSTL-1 and OSTL-2. (a) XPS full measurement spectra of OSTL-1; (b) XPS full measurement spectra of OSTL-2; (c) High-resolution C 1s spectrum of OSTL-1; (d) High-resolution C 1s spectrum of OSTL-2; (e) High-resolution O 1s spectrum of OSTL-1; and (f) High-resolution O 1s spectrum of OSTL-2.

Figure 7.

XPS spectra of OSTL-1 and OSTL-2. (a) XPS full measurement spectra of OSTL-1; (b) XPS full measurement spectra of OSTL-2; (c) High-resolution C 1s spectrum of OSTL-1; (d) High-resolution C 1s spectrum of OSTL-2; (e) High-resolution O 1s spectrum of OSTL-1; and (f) High-resolution O 1s spectrum of OSTL-2.

Figure 8.

Mold resistance testing of starch (ST), oxidized starch (OST) and OSTL adhesive in liquid form.

Figure 8.

Mold resistance testing of starch (ST), oxidized starch (OST) and OSTL adhesive in liquid form.

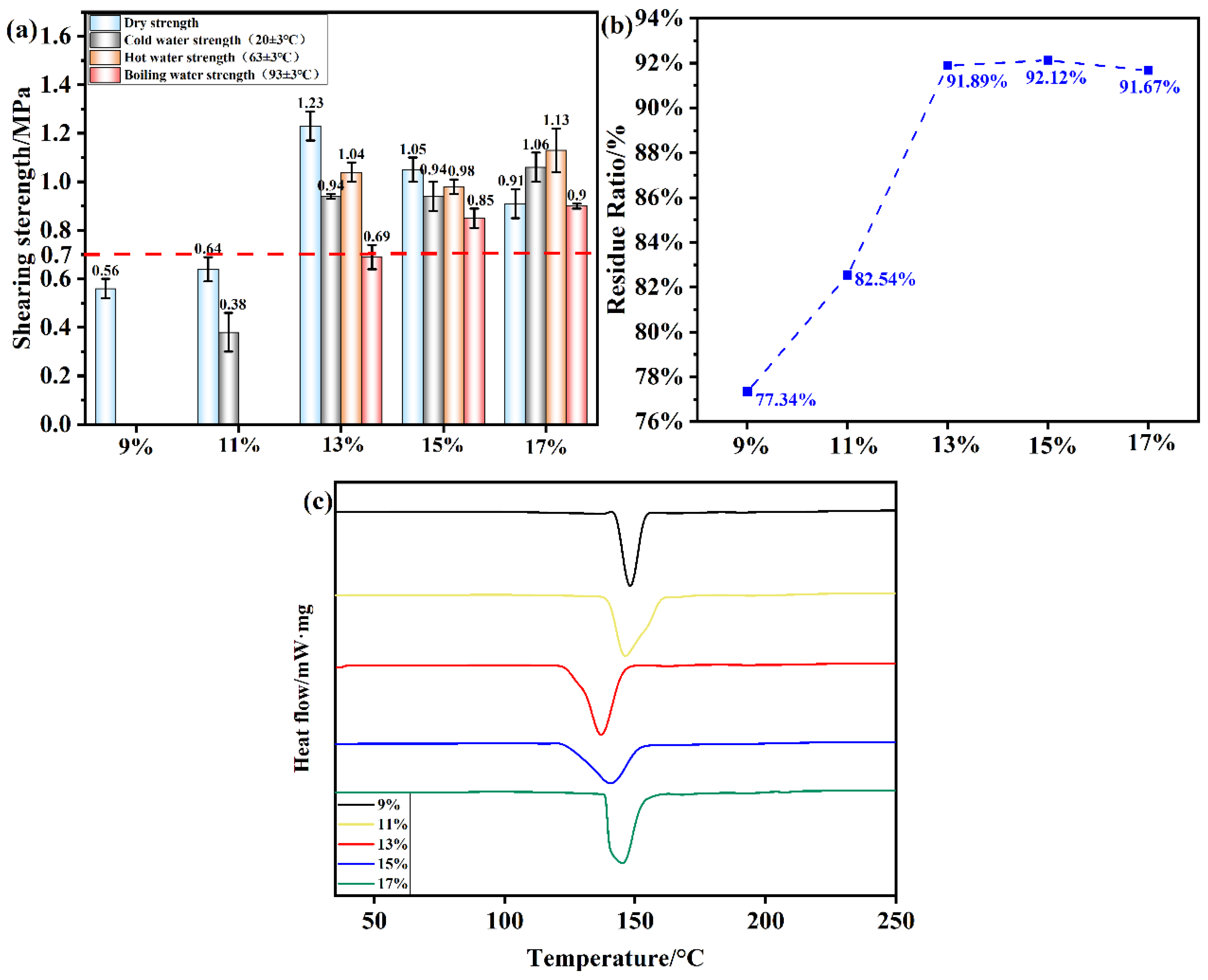

Figure 9.

(a) Shear strength of plywood prepared using OSTL adhesives prepared under different oxidation times of OST as precursor ; (b) Hydrolysis residual rate of OSTL adhesive under different oxidation times of OST as precursor; (c) DSC traces of OSTL adhesives prepared under different oxidation times of OST as precursor.

Figure 9.

(a) Shear strength of plywood prepared using OSTL adhesives prepared under different oxidation times of OST as precursor ; (b) Hydrolysis residual rate of OSTL adhesive under different oxidation times of OST as precursor; (c) DSC traces of OSTL adhesives prepared under different oxidation times of OST as precursor.

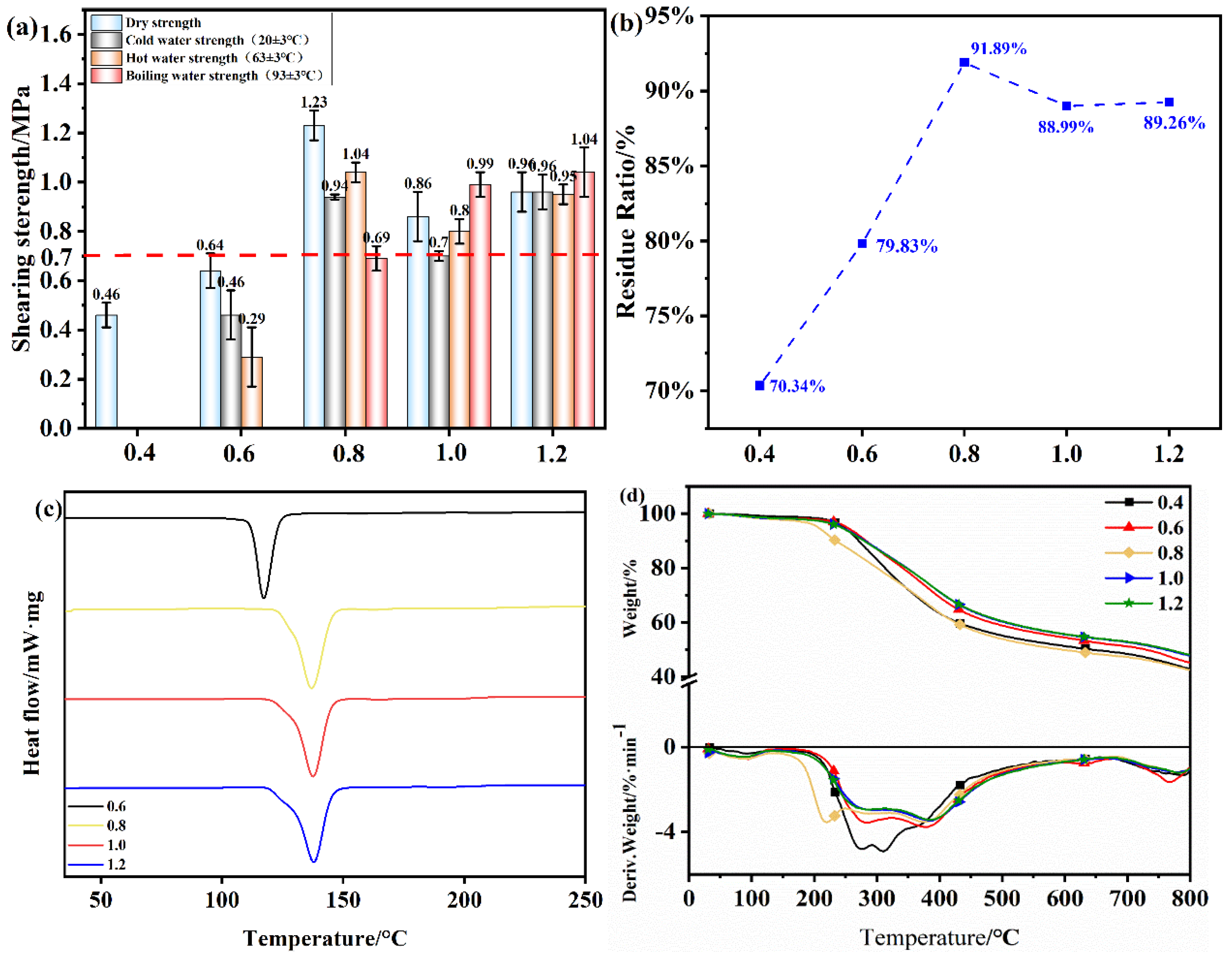

Figure 10.

(a) Shear strength of plywood prepared using OSTL adhesives formulated with OST prepared using different oxidant additions; (b) Hydrolysis residual rate of OSTL adhesives formulated with OST prepared with different oxidant additions; (c) DSC curve of OSTL adhesives formulated with OST prepared using different oxidant additions.

Figure 10.

(a) Shear strength of plywood prepared using OSTL adhesives formulated with OST prepared using different oxidant additions; (b) Hydrolysis residual rate of OSTL adhesives formulated with OST prepared with different oxidant additions; (c) DSC curve of OSTL adhesives formulated with OST prepared using different oxidant additions.

Figure 11.

(a) Shear strength of plywood prepared using OSTL adhesives prepared with different starch to lignin mass ratios; (b) Hydrolysis residual rate of OSTL adhesives prepared with different starch to lignin mass ratios; (c) DSC thermograms of OSTL adhesives prepared with different starch to lignin mass ratios; (d) TGA traces of OSTL adhesives prepared with different starch to lignin mass ratios.

Figure 11.

(a) Shear strength of plywood prepared using OSTL adhesives prepared with different starch to lignin mass ratios; (b) Hydrolysis residual rate of OSTL adhesives prepared with different starch to lignin mass ratios; (c) DSC thermograms of OSTL adhesives prepared with different starch to lignin mass ratios; (d) TGA traces of OSTL adhesives prepared with different starch to lignin mass ratios.

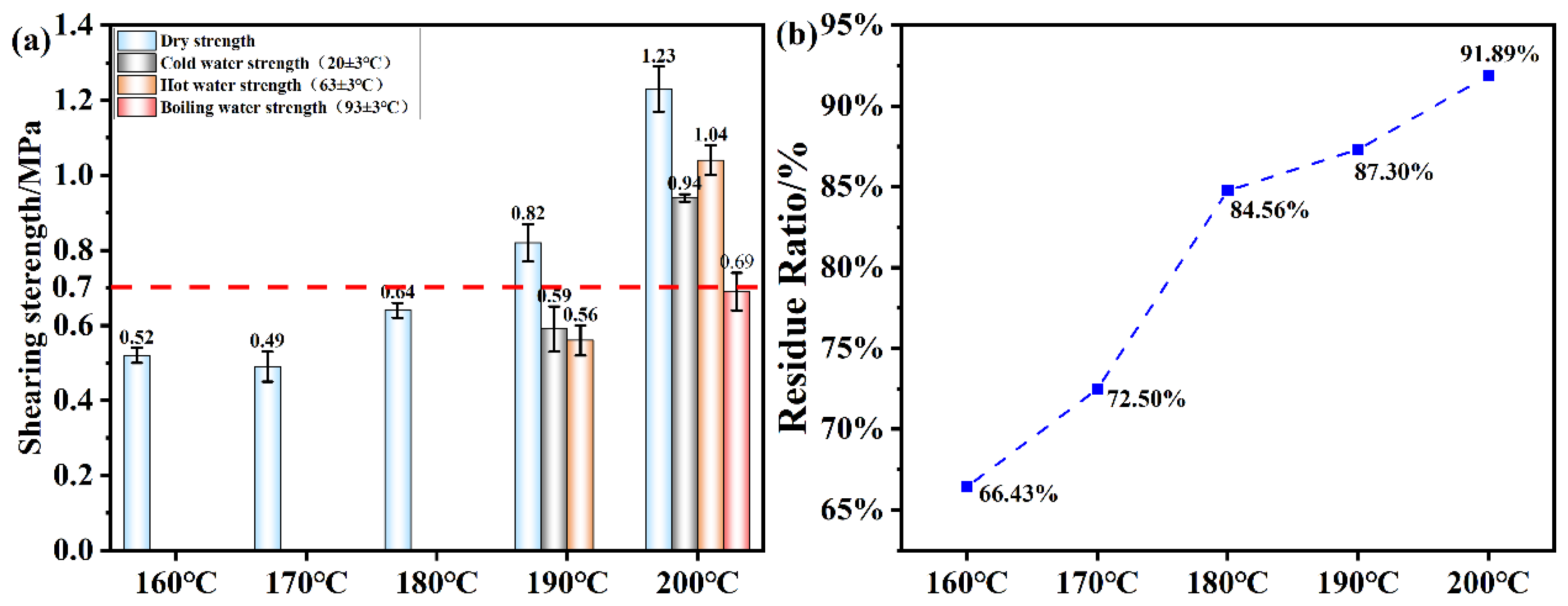

Figure 12.

(a) Shear strength of plywood prepared using OSTL adhesives prepared at different hot-pressing temperatures; (b) Hydrolyzed residual rate of OSTL adhesives prepared at different hot-pressing temperature.

Figure 12.

(a) Shear strength of plywood prepared using OSTL adhesives prepared at different hot-pressing temperatures; (b) Hydrolyzed residual rate of OSTL adhesives prepared at different hot-pressing temperature.

Table 1.

Elemental composition of C 1s in ST.

Table 1.

Elemental composition of C 1s in ST.

| Name |

peak |

FWHM (eV) |

Area(P) CPS. eV |

Atomic (%) |

| C-C |

284.80 |

1.21 |

46384.29 |

35.70 |

| C-O |

286.52 |

1.51 |

69450.80 |

53.45 |

| C-O-C |

288.12 |

1.84 |

14109.65 |

10.86 |

Table 2.

Elemental composition of C 1s in OST.

Table 2.

Elemental composition of C 1s in OST.

| Name |

peak |

FWHM (eV) |

Area(P) CPS. eV |

Atomic (%) |

| C-C |

284.80 |

1.34 |

23135.67 |

16.07 |

| C-O |

286.35 |

1.38 |

98516.11 |

68.44 |

| C=O |

287.76 |

1.21 |

16834.70 |

11.70 |

| O-C=O |

288.60 |

1.48 |

5449.34 |

3.79 |

Table 3.

Elemental composition of O 1s in OSTL-1.

Table 3.

Elemental composition of O 1s in OSTL-1.

| Name |

peak |

FWHM (eV) |

Area(P) CPS. eV |

Atomic (%) |

| C-O |

532.80 |

1.85 |

212974.74 |

93.92 |

| C=O |

531.30 |

1.29 |

13710.86 |

6.05 |

| O-C=O |

534.90 |

1.30 |

86.48 |

0.04 |

Table 4.

Elemental composition of O 1s in OSTL-2.

Table 4.

Elemental composition of O 1s in OSTL-2.

| Name |

peak |

FWHM (eV) |

Area(P) CPS. eV |

Atomic (%) |

| C-O |

532.70 |

2.48 |

158164.89 |

99.62 |

| C=O |

529.00 |

0.54 |

225.13 |

0.14 |

| O-C=O |

534.82 |

0.54 |

373.98 |

0.24 |

Table 5.

Curing characteristics of OSTL adhesives formulated from OST prepared under different oxidation times.

Table 5.

Curing characteristics of OSTL adhesives formulated from OST prepared under different oxidation times.

| Time/h |

Starting

temperature/℃

|

Maximum

exothermic

peak/℃

|

Termination

temperature/℃

|

Enthalpy/ (J.g-1)

|

| 3 |

162.0 |

166.8 |

174.2 |

951.7 |

| 6 |

128.1 |

137.0 |

145.1 |

951.4 |

| 9 |

169.7 |

176.9 |

184.5 |

1156.0 |

| 12 |

159.4 |

165.4 |

172.2 |

1024.0 |

Table 6.

Curing characteristics of OSTL adhesives formulated with OST prepared using different oxidant additions.

Table 6.

Curing characteristics of OSTL adhesives formulated with OST prepared using different oxidant additions.

| Additions /% |

Starting

temperature/℃

|

Maximum

exothermic

peak/℃

|

Termination

temperature/℃

|

Enthalpy/ (J.g-1)

|

| 9 |

142.8 |

148.1 |

153.5 |

666 |

| 11 |

144.0 |

154.8 |

162.1 |

997.4 |

| 13 |

128.1 |

137.0 |

145.1 |

951.4 |

| 15 |

125.5 |

141.1 |

150.1 |

814.2 |

| 17 |

126.3 |

140.5 |

149.8 |

779.8 |

Table 7.

Curing characteristics of OSTL adhesives prepared with different starch to lignin mass ratios.

Table 7.

Curing characteristics of OSTL adhesives prepared with different starch to lignin mass ratios.

| Starch |

Starting

temperature/℃

|

Maximum

exothermic

peak/℃

|

Termination

temperature/℃

|

Enthalpy/ (J.g-1)

|

| 0.6 |

110.5 |

127.5 |

137.9 |

689.2 |

| 0.8 |

128.1 |

137.0 |

145.1 |

988.2 |

| 1.0 |

128.3 |

137.8 |

144.9 |

970.2 |

| 1.2 |

128.7 |

138.1 |

145.1 |

978.0 |