1. Introduction

Surgical fixation provides accurate reduction and rigid stabilization but is associated with complications such as stress shielding, marrow cavity obstruction, implant fatigue, and implant-related bone resorption [

1,

2,

3]. In slender bones, when the screw diameter exceeds the intramedullary canal, blood flow may be obstructed, impairing the supply of marrow-derived stem cells and predisposing to delayed healing or nonunion [

4,

5,

6]. Furthermore, direct bone healing under plating results in little callus formation, making radiographic assessment of union less objective and reproducible [

7].

Conventional casting, although minimally invasive, has well-recognized limitations. Prolonged immobilization may result in muscle atrophy, osteopenia, and angular deformities of the radius, and stability is often inadequate for displaced complete fractures [

8]. Strict motion restriction is particularly unrealistic in young, active dogs. Thus, there is a demand for a minimally invasive, practical treatment that allows both functional activity and objective evaluation of the healing process.

Bone repair is known to proceed through the inflammatory, reparative, and remodeling phases, coordinated by complex cellular and molecular interactions [

5,

6,

15]. Mechanical stimulation during the reparative phase has been shown to direct mesenchymal stem cell differentiation and enhance endochondral ossification [

9,

10,

11,

12,

15], whereas excessive rigidity or instability can impair this process.

To address these biological and mechanical challenges, we developed a novel three-dimensional (3D) cast therapy strategy integrating both principles. During the inflammatory phase, alignment is restored by closed reduction and rigid temporary immobilization. In the early repair phase, a case-specific 3D cast is applied, permitting ambulation and controlled axial loading. This approach aligns with evidence that moderate mechanical stimulation in the repair phase promotes differentiation of marrow-derived progenitors and induces abundant callus formation [

9,

10,

11,

12,

16,

19]. Moreover, according to Wolff’s law, bone adapts to mechanical stress, and flexible fixation with controlled stability may enhance bone regeneration compared with excessively rigid constructs. In dogs, the radius and ulna are predominantly subjected to axial loading throughout the stance phase [

13], creating an optimal biomechanical environment for this treatment.

By combining these principles, the 3D cast achieves a balance of stability and controlled flexibility, promotes indirect bone healing, and enables sequential radiographic visualization of fracture repair with improved objectivity and reproducibility.

2. Materials and Methods

Since 2018, dogs with complete radial–ulnar fractures have been treated at our hospital using a standardized conservative protocol based on case-specific 3D cast therapy.

After injury, alignment was restored by closed manual reduction using traction, and the affected limb was stabilized with non-elastic tape and a splint. The limb was immobilized from the elbow to the paw, followed by a rest period of approximately one week [

17,

18]. Between 7 and 10 days after injury, a plaster model was created, from which a cylindrical 3D cast was fabricated. The cast incorporated a longitudinal slit with a stepped overlap, allowing both stability and easy removal. Ambulation was permitted immediately after application. Thereafter, the cast was removed weekly for cleansing, and radiographic evaluations were performed every two weeks using four standard projections (craniocaudal, mediolateral, and two oblique views) to monitor healing. The 3D cast was lightweight, durable, and conforming, allowing dogs to walk, trot, and even jump during treatment. Healing was defined radiographically as the presence of bridging callus across the fracture line in these four projections, at which point the cast was removed. No additional immobilization was required after removal. All treatments were performed with informed owner consent.

Materials for Fabrication of the 3D Cast

Splints: JL Carpal Splint (Jorgensen Laboratories Inc., USA); Kishigami-style Plastic Splint (TSUGAWA TRADING, Japan)

Impression material: Alginate (Hygedent, Ci Medical Co., Ltd., Japan)

Spacer material: Acrylic foam tape, 1.1–1.5 mm (Amon Industry Co., Ltd., Japan)

Casting material: 3M™ Scotchcast™ Plus Casting Tape (3M Japan Limited, Japan)

Non-elastic tapes: 3M™ Durapore Surgical Tape; 3M™ Multipore Sports Non-Stretch Tape (3M Japan Limited, Japan)

Elastic adhesive bandage: Yutir, 5 cm × 5 m (Iwatsuki Co., Ltd., Japan)

Plaster for mold: Ci Hard Plaster Yellow (Ci Medical Co., Ltd., Japan)

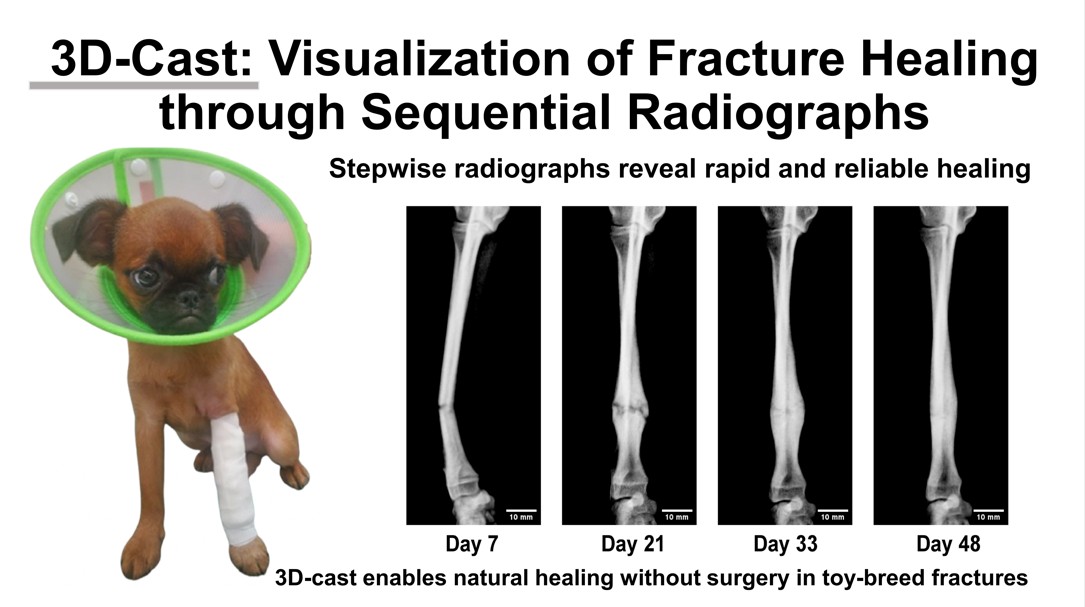

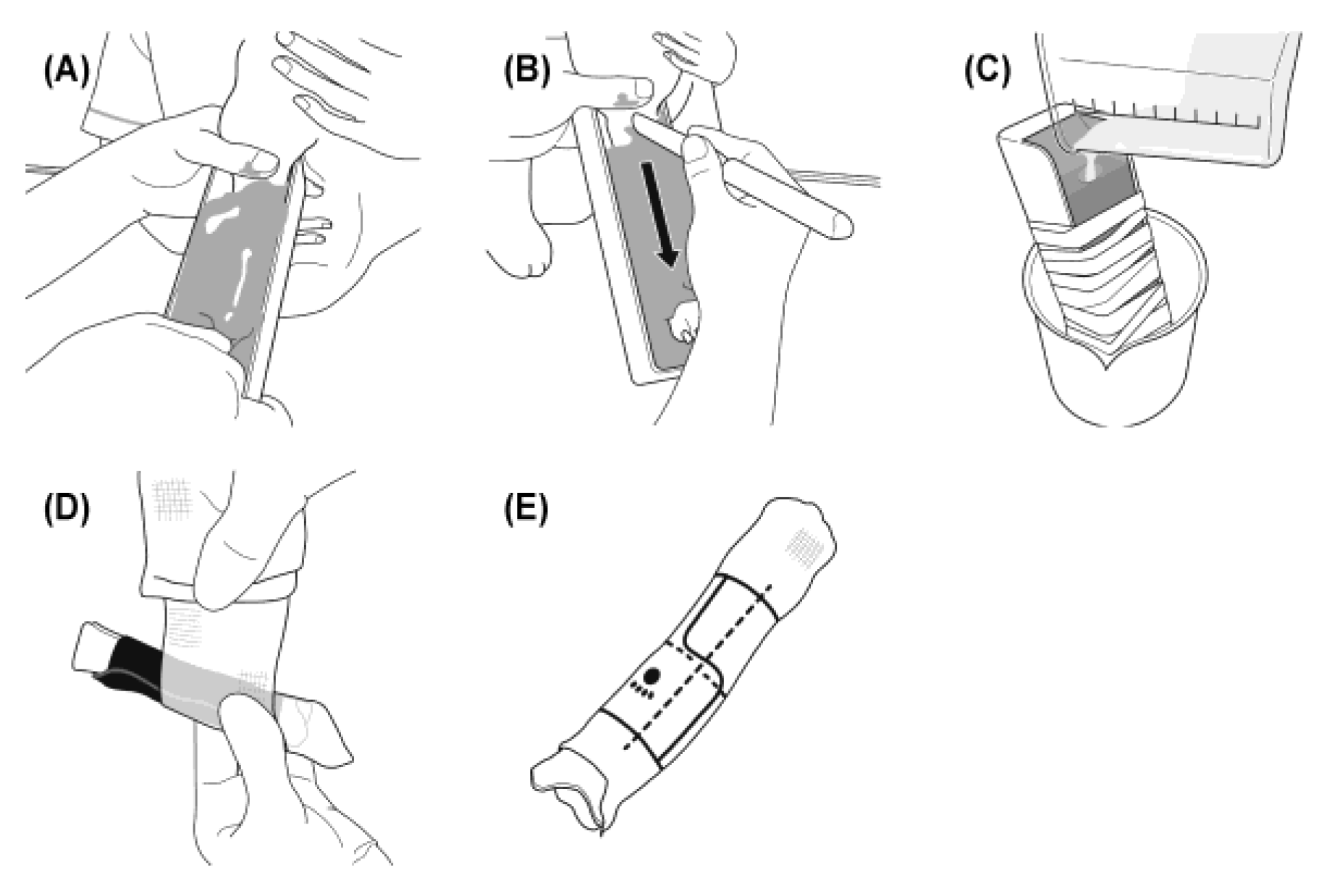

The procedure for complete immobilization applied in the early post-injury phase is illustrated in

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Procedure for initial immobilization after fracture. The distal forelimb was clipped, and the fracture line was identified by palpation. The splint was secured proximally and at the elbow with non-elastic tape. Manual traction was then applied to the paw to restore alignment while fixing the distal limb and splint together. The entire limb was subsequently wrapped with an elastic adhesive bandage to prevent displacement and anchored to the thorax for complete immobilization. (A) The distal forelimb was clipped, and the fracture line is identified and marked by palpation. (B) A 2.5- cm non-elastic tape is used to secure the splint proximally and at the elbow. The proximal fragment was stabilized with one hand, while the distal fragment is manually tractioned with the other to restore alignment, after which the splint is fixed in position with non-elastic tape. (C) The entire limb iwasi then wrapped with an elastic adhesive bandage to prevent splint displacement, and the fixation is further anchored to the thorax.

Figure 1.

Procedure for initial immobilization after fracture. The distal forelimb was clipped, and the fracture line was identified by palpation. The splint was secured proximally and at the elbow with non-elastic tape. Manual traction was then applied to the paw to restore alignment while fixing the distal limb and splint together. The entire limb was subsequently wrapped with an elastic adhesive bandage to prevent displacement and anchored to the thorax for complete immobilization. (A) The distal forelimb was clipped, and the fracture line is identified and marked by palpation. (B) A 2.5- cm non-elastic tape is used to secure the splint proximally and at the elbow. The proximal fragment was stabilized with one hand, while the distal fragment is manually tractioned with the other to restore alignment, after which the splint is fixed in position with non-elastic tape. (C) The entire limb iwasi then wrapped with an elastic adhesive bandage to prevent splint displacement, and the fixation is further anchored to the thorax.

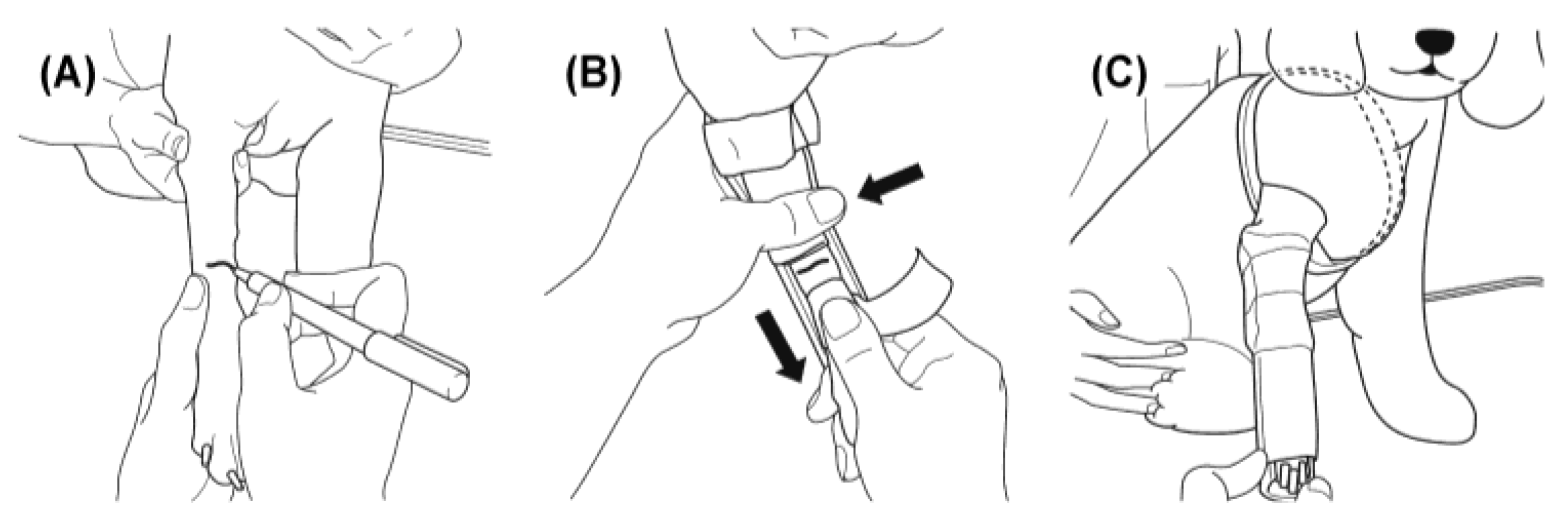

The fabrication process of the case-specific 3D cast is illustrated in

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Procedure for fabrication of the 3D cast. After removal of the temporary splint, the affected limb was molded using alginate impression material to create a negative cast. The mold was filled with plaster to obtain a solid model, around which a 1.1-mm acrylic foam sheet was applied to form the inner layer in contact with the skin. Over this, two spiral layers of resin casting tape (Scotchcast™) were applied as the outer structure. A stepped longitudinal slit was incorporated to ensure both stability and easy removal.(A) After removing the temporary splint, the affected limb is placed in a tray and molded using alginate impression material. (B) Once the alginate has set, a linear incision is made with a spatula, and the limb is withdrawn. (C) The mold is filled with a mixture of water and plaster to create a solid plaster model. (D) A 1.1-mm acrylic foam sheet is wrapped around the plaster model, and resin casting tape is applied in two spiral layers to form the cylindrical cast. (E) For small-breed dogs, the cast length is adjusted to 70–85% of the radial length. The resin cast is positioned vertically in the frontal plane and trimmed at both ends. A longitudinal slit with a step is made centrally, and reference marks (paw print at the distal end, vertical line on the front, and horizontal line at the fracture site) are added for orientation.

Figure 2.

Procedure for fabrication of the 3D cast. After removal of the temporary splint, the affected limb was molded using alginate impression material to create a negative cast. The mold was filled with plaster to obtain a solid model, around which a 1.1-mm acrylic foam sheet was applied to form the inner layer in contact with the skin. Over this, two spiral layers of resin casting tape (Scotchcast™) were applied as the outer structure. A stepped longitudinal slit was incorporated to ensure both stability and easy removal.(A) After removing the temporary splint, the affected limb is placed in a tray and molded using alginate impression material. (B) Once the alginate has set, a linear incision is made with a spatula, and the limb is withdrawn. (C) The mold is filled with a mixture of water and plaster to create a solid plaster model. (D) A 1.1-mm acrylic foam sheet is wrapped around the plaster model, and resin casting tape is applied in two spiral layers to form the cylindrical cast. (E) For small-breed dogs, the cast length is adjusted to 70–85% of the radial length. The resin cast is positioned vertically in the frontal plane and trimmed at both ends. A longitudinal slit with a step is made centrally, and reference marks (paw print at the distal end, vertical line on the front, and horizontal line at the fracture site) are added for orientation.

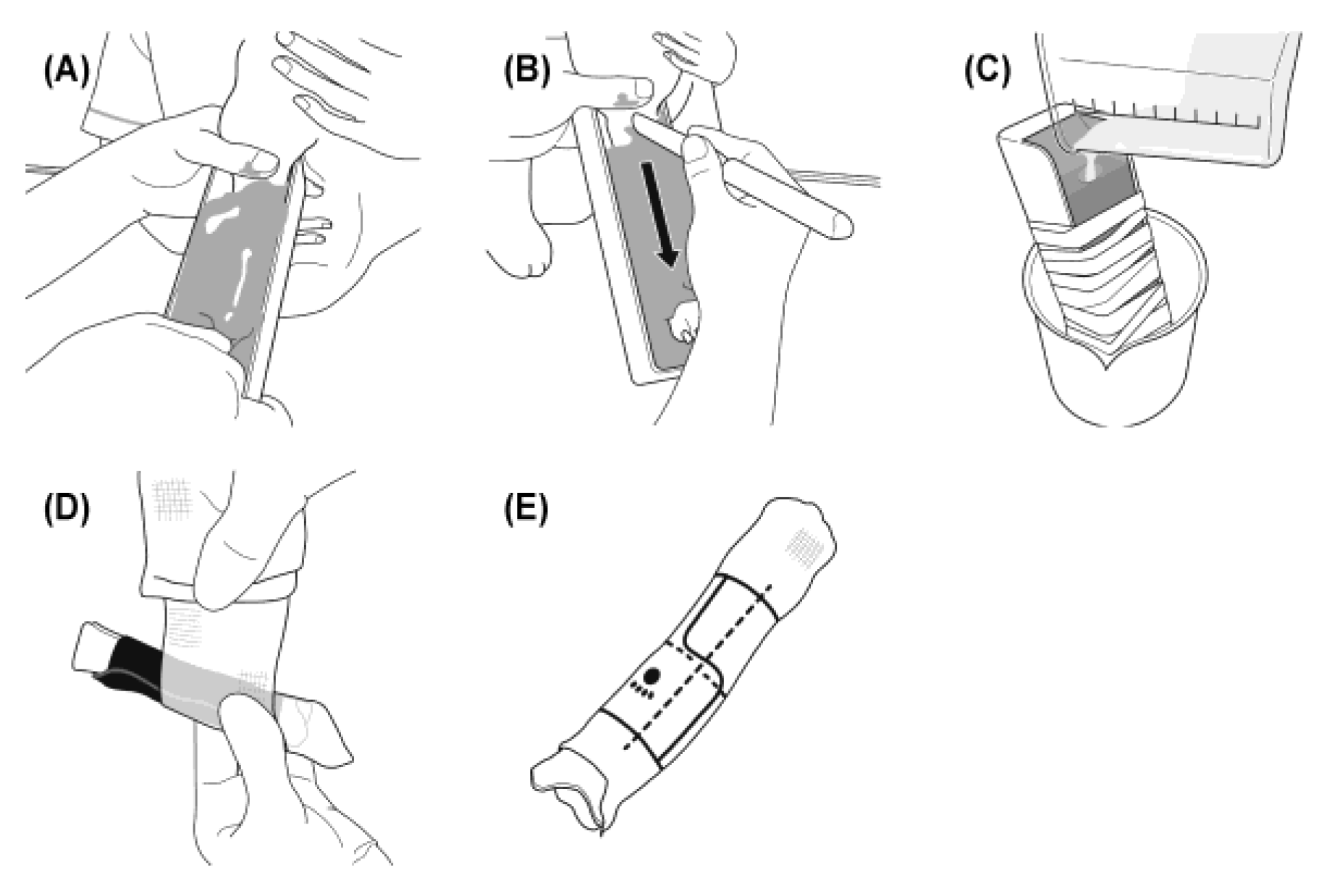

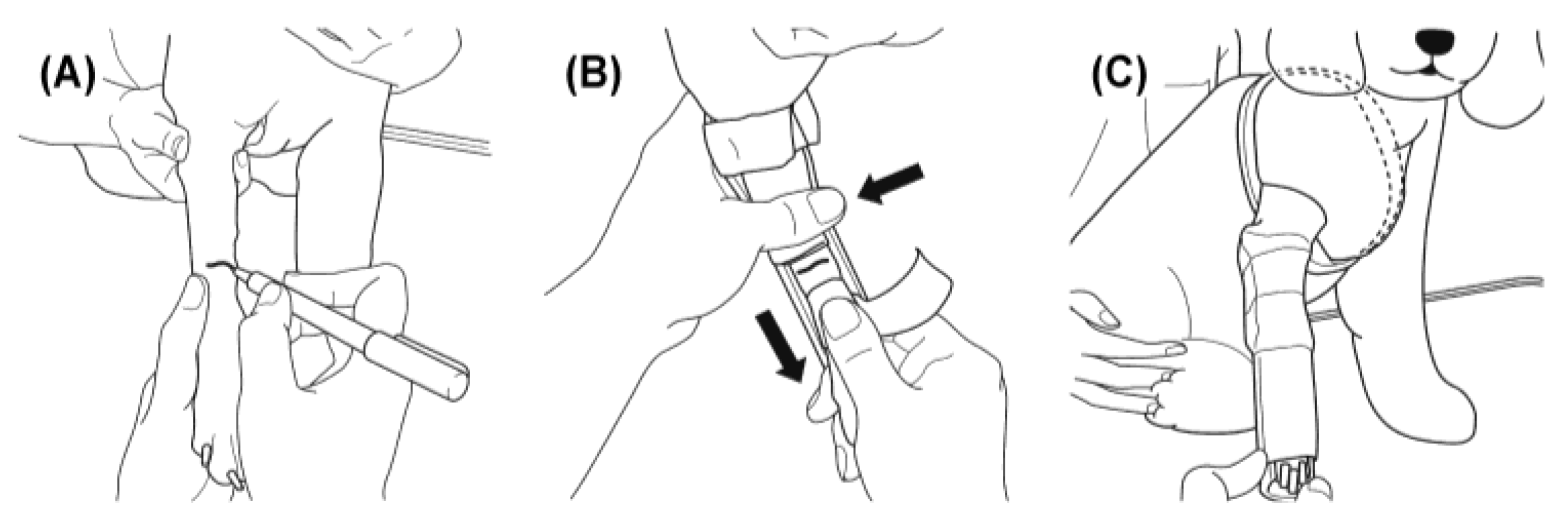

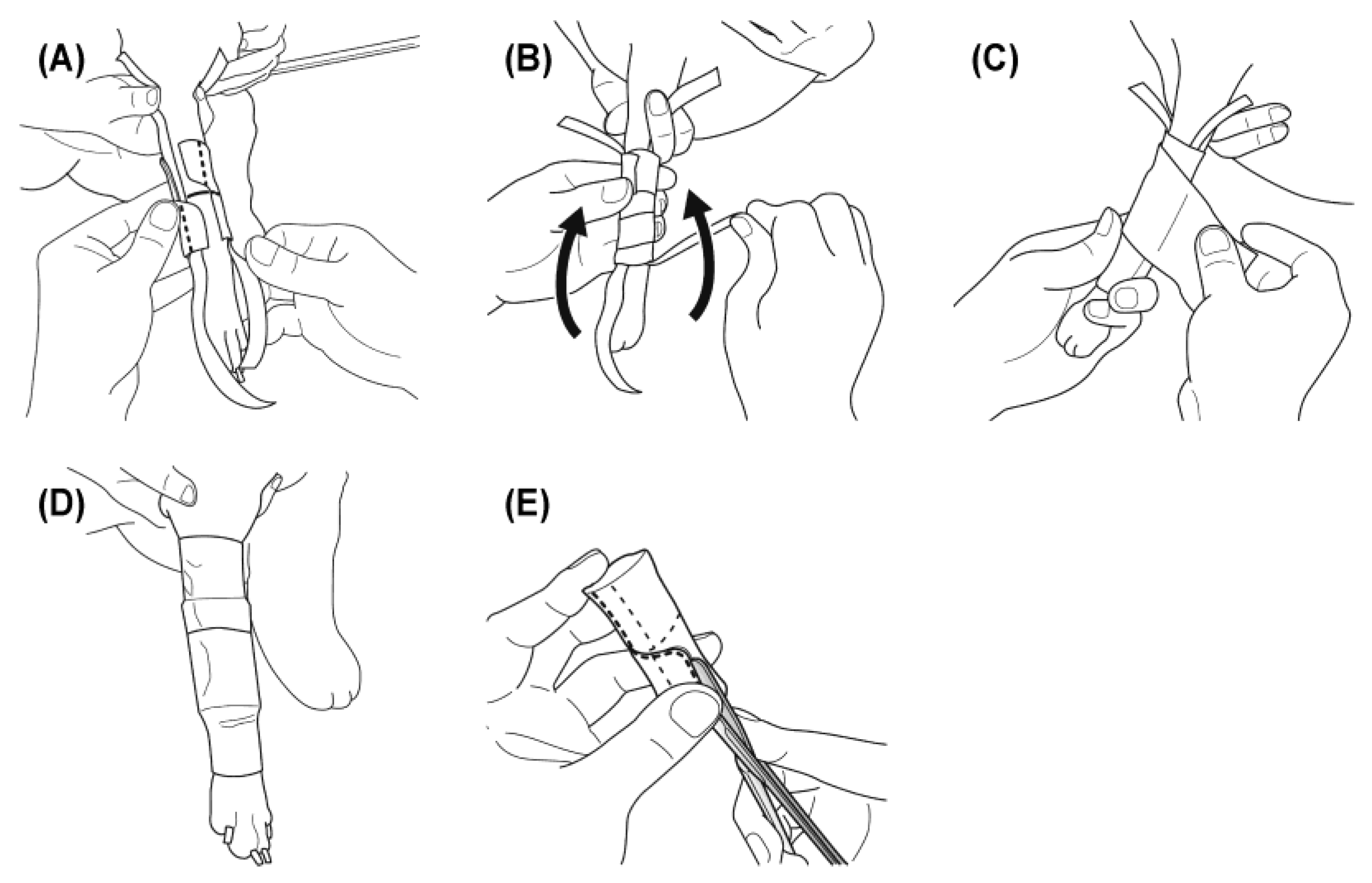

Application and adjustment of the 3D cast are demonstrated in

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Application and adjustment of the 3D cast. To maintain stability during ambulation, two types of non-elastic tape were used. Two longitudinal strips (1.25 cm wide) were placed along the medial and lateral sides of the limb, and the 3D cast was fitted over them. The cast was then secured circumferentially with 2.5 cm non-elastic tape, and the longitudinal strips were folded proximally to reinforce fixation. The entire cast was covered with an elastic adhesive bandage to prevent displacement during movement and to ensure stable immobilization. (A) Two strips of 1.25 cm non-elastic tape are placed longitudinally on the medial and lateral aspects of the limb, and the 3D cast is fitted over them. (B) The cast is secured with 2.5 cm non-elastic tape, and the longitudinal strips are folded proximally to reinforce fixation. (C) The entire cast is covered with an elastic bandage. (D) Final appearance of the applied cast, after which ambulation is permitted. (E) During treatment, if loosening occurs between the limb and the cast, a longitudinal slit is cut to restore close fit and stability.

Figure 3.

Application and adjustment of the 3D cast. To maintain stability during ambulation, two types of non-elastic tape were used. Two longitudinal strips (1.25 cm wide) were placed along the medial and lateral sides of the limb, and the 3D cast was fitted over them. The cast was then secured circumferentially with 2.5 cm non-elastic tape, and the longitudinal strips were folded proximally to reinforce fixation. The entire cast was covered with an elastic adhesive bandage to prevent displacement during movement and to ensure stable immobilization. (A) Two strips of 1.25 cm non-elastic tape are placed longitudinally on the medial and lateral aspects of the limb, and the 3D cast is fitted over them. (B) The cast is secured with 2.5 cm non-elastic tape, and the longitudinal strips are folded proximally to reinforce fixation. (C) The entire cast is covered with an elastic bandage. (D) Final appearance of the applied cast, after which ambulation is permitted. (E) During treatment, if loosening occurs between the limb and the cast, a longitudinal slit is cut to restore close fit and stability.

The length of the 3D cast was set at 70–85% of the radial length in dogs weighing ≤5 kg. Although greater length provides increased stability, dogs such as Italian Greyhounds, those with proximal radial fractures, or those with substantial surrounding musculature were at higher risk of developing compartment syndrome; therefore, cast length was adjusted appropriately according to clinical signs. In cases where distal limb edema was observed, compression with an elastic bandage and local icing were applied to reduce swelling. Throughout the treatment period, dogs were fitted with an Elizabethan collar to prevent self-trauma, and careful monitoring was conducted for dermatitis or edema. Cases were re-examined approximately once weekly to assess cast fit, after which the cast was removed, the skin cleansed, and the cast reapplied.

Case Selection

Four cases were selected because they were considered unsuitable for conventional conservative treatment and would normally require surgical fixation. Specifically:

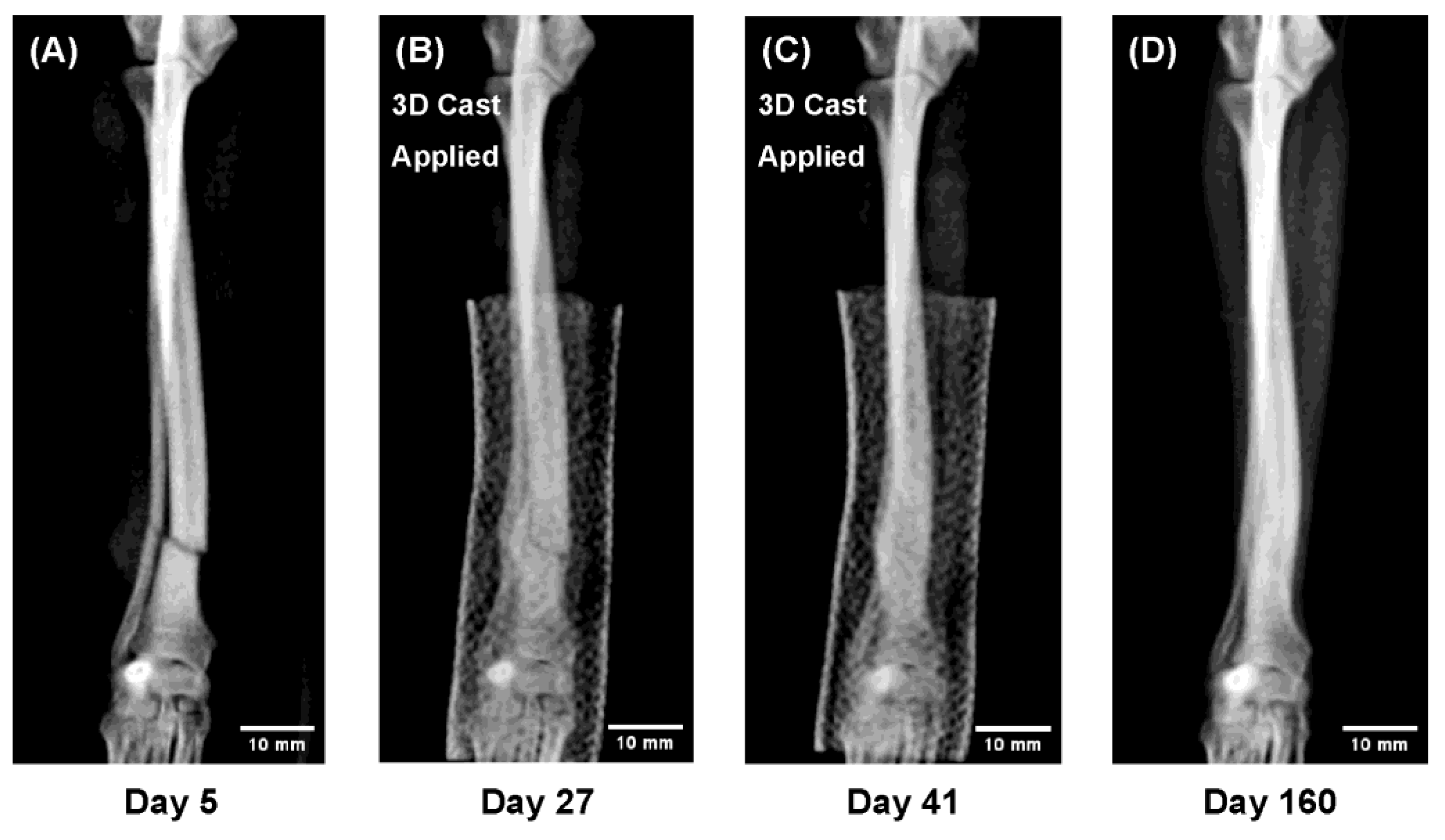

• A distal radial–ulnar fracture in a toy-breed dog with extremely slender bones (

Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sequential radiographs showing radial–ulnar fracture healing under 3D cast treatment in a Pomeranian, 13 months old, 1.9 kg. Both the radius and ulna achieved union while the limb remained immobilized, allowing direct observation of indirect bone healing. The remodeling phase demonstrated trabecular reconstruction and restoration of the medullary cavity. (A) Day 5 after injury (3D cast applied on Day 9). (B) Day 27: callus formation and partial bridging. (C) Day 41: cast removal. (D) Day 160: complete remodeling and recovery of bone morphology.

Figure 4.

Sequential radiographs showing radial–ulnar fracture healing under 3D cast treatment in a Pomeranian, 13 months old, 1.9 kg. Both the radius and ulna achieved union while the limb remained immobilized, allowing direct observation of indirect bone healing. The remodeling phase demonstrated trabecular reconstruction and restoration of the medullary cavity. (A) Day 5 after injury (3D cast applied on Day 9). (B) Day 27: callus formation and partial bridging. (C) Day 41: cast removal. (D) Day 160: complete remodeling and recovery of bone morphology.

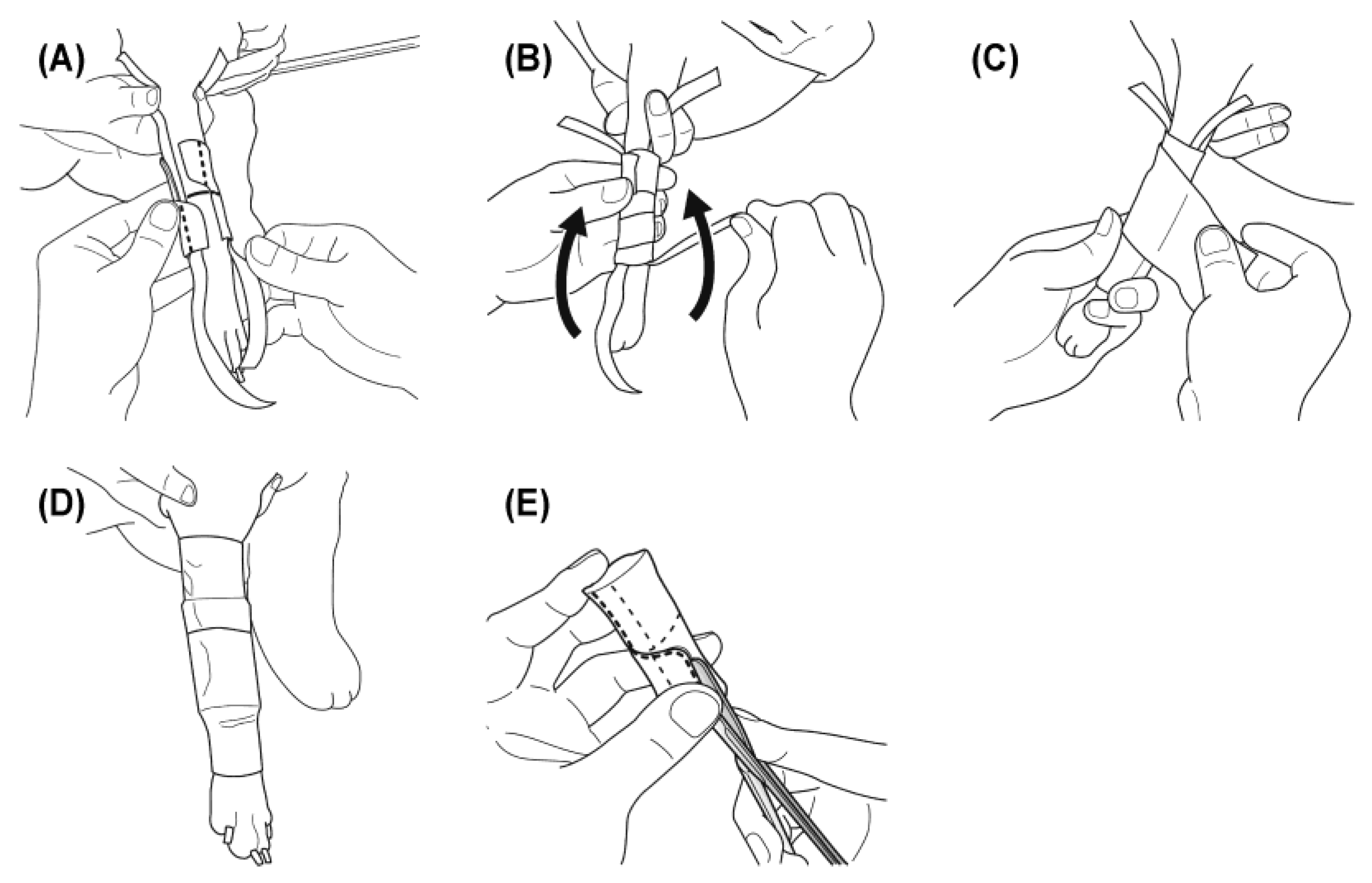

• A juvenile dog with a complete fracture of the radius and ulna (

Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sequential radiographs showing rapid callus formation and remodeling in a juvenile dog (“Super-Healing”). Intensive callus proliferation and early bridging were observed within two weeks, indicating highly active osteogenesis under functional loading. This process reflects the intrinsic regenerative potential of young bone, providing a clinical in vivo model that parallels key concepts of regenerative medicine. (A) Day 7 after injury: fracture line remained distinct. (B) Day 21: marked increase in radial diameter due to callus formation. (C) Day 33: bridging callus confirmed; cast removed. (D) Day 48: remodeling with cortical thinning and increased density.

Figure 5.

Sequential radiographs showing rapid callus formation and remodeling in a juvenile dog (“Super-Healing”). Intensive callus proliferation and early bridging were observed within two weeks, indicating highly active osteogenesis under functional loading. This process reflects the intrinsic regenerative potential of young bone, providing a clinical in vivo model that parallels key concepts of regenerative medicine. (A) Day 7 after injury: fracture line remained distinct. (B) Day 21: marked increase in radial diameter due to callus formation. (C) Day 33: bridging callus confirmed; cast removed. (D) Day 48: remodeling with cortical thinning and increased density.

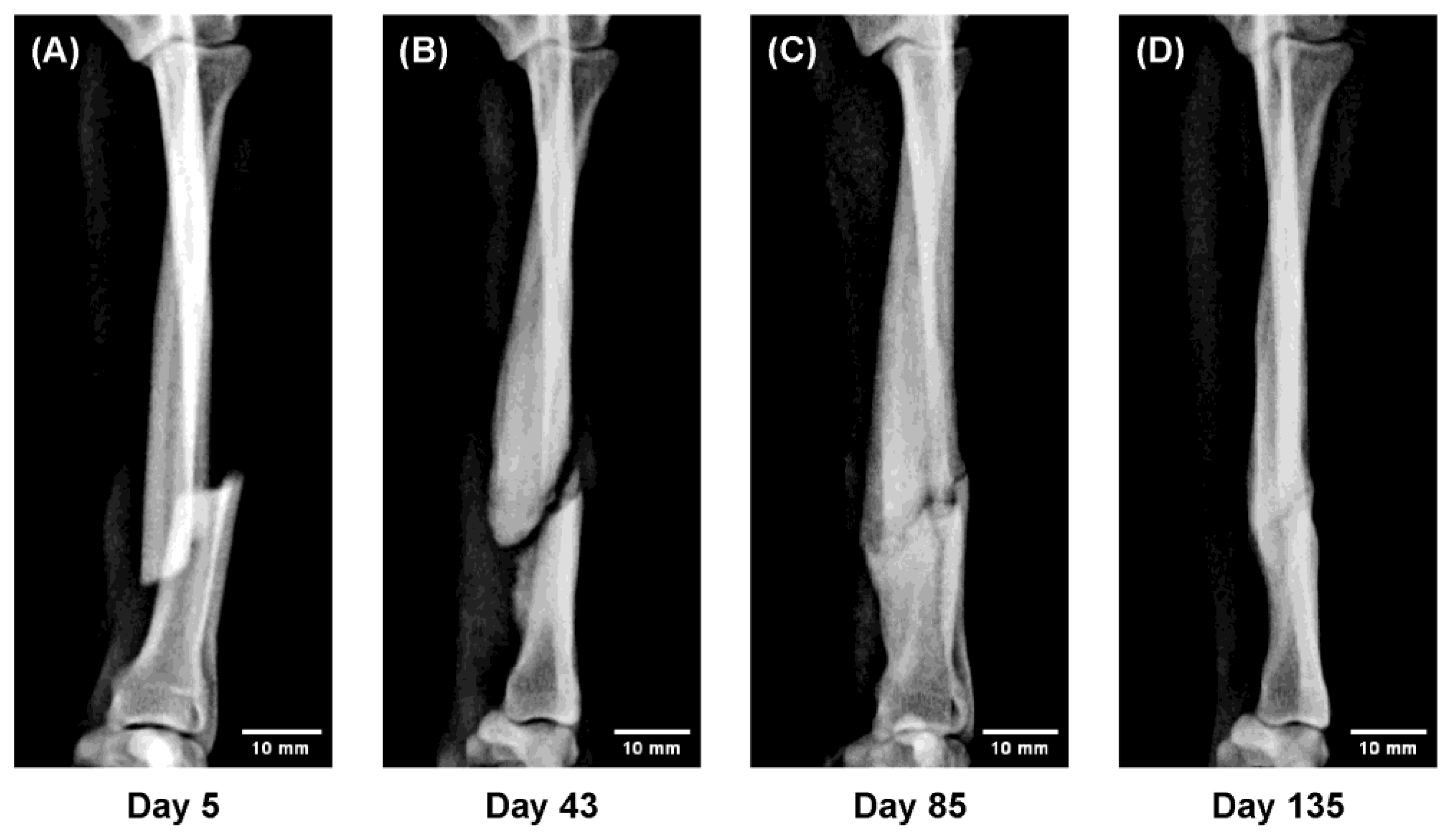

• A fracture with marked displacement (

Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Sequential radiographs showing gradual realignment of displaced fragments under functional loading (“Slide-Healing”). The progressive correction of malalignment through load-guided remodeling demonstrates how physiological mechanical stimuli can direct bone regeneration—a principle central to regenerative medicine. (A) Day 5 after injury; temporary immobilization performed; 3D cast applied on Day 10. (B) Day 43: abundant callus with gradual realignment of fragments. (C) Day 85: bony union confirmed; cast removed on Day 100. (D) Day 135: remodeling with restored alignment and normal bone thickness.

Figure 6.

Sequential radiographs showing gradual realignment of displaced fragments under functional loading (“Slide-Healing”). The progressive correction of malalignment through load-guided remodeling demonstrates how physiological mechanical stimuli can direct bone regeneration—a principle central to regenerative medicine. (A) Day 5 after injury; temporary immobilization performed; 3D cast applied on Day 10. (B) Day 43: abundant callus with gradual realignment of fragments. (C) Day 85: bony union confirmed; cast removed on Day 100. (D) Day 135: remodeling with restored alignment and normal bone thickness.

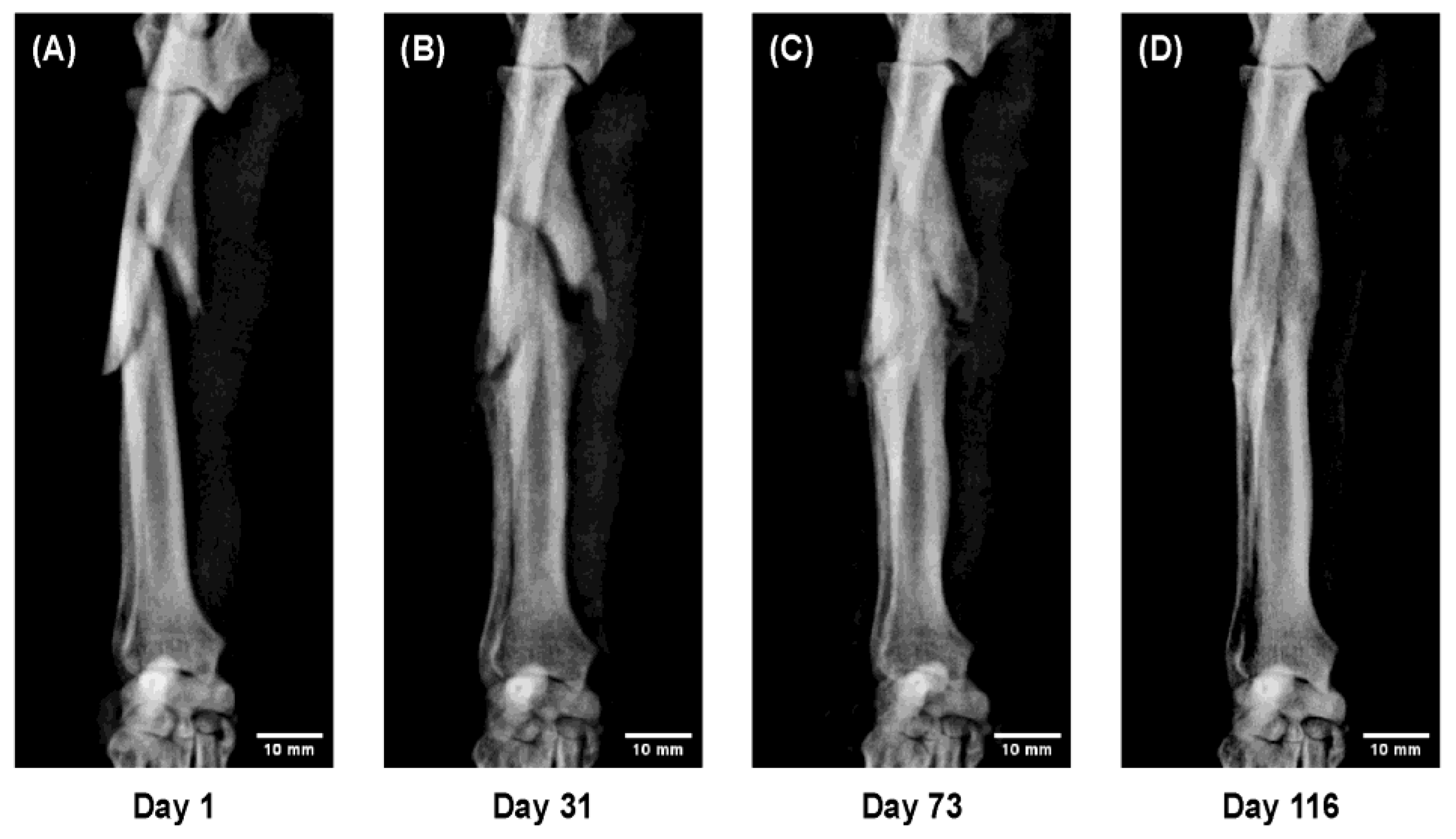

• A comminuted fracture in an elderly dog representing an advanced and complex condition (

Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Sequential radiographs showing a comminuted radial–ulnar fracture in a Toy Poodle, 9 years old, 6.7 kg. Despite severe displacement and fragmentation, successful bone union was obtained with 3D cast therapy, although callus formation was limited. (A) Day 1 after injury; temporary immobilization performed; 3D cast applied on Day 10. (B) Day 31: fragment thickening with maintained alignment. (C) Day 73: progressive callus formation and bony union. (D) Day 116: remodeling with restored bone morphology.

Figure 7.

Sequential radiographs showing a comminuted radial–ulnar fracture in a Toy Poodle, 9 years old, 6.7 kg. Despite severe displacement and fragmentation, successful bone union was obtained with 3D cast therapy, although callus formation was limited. (A) Day 1 after injury; temporary immobilization performed; 3D cast applied on Day 10. (B) Day 31: fragment thickening with maintained alignment. (C) Day 73: progressive callus formation and bony union. (D) Day 116: remodeling with restored bone morphology.

Radiographic Image Processing

Radiographs of left limbs were mirrored for consistent orientation. Brightness and contrast were adjusted uniformly, and images were cropped to focus on the fracture site while preserving key anatomical landmarks. Scale bars were added in Fiji software [

14] based on DICOM metadata. Final images were

exported as 300 dpi uncompressed TIFF files

in accordance with the journal’s submission requirements.

3. Results

Representative Cases

Sequential radiographs of representative cases demonstrated the progression of fracture healing under 3D cast management (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

Figure 4. In a 13 month-old Pomeranian with extremely slender bones, both the radius and ulna achieved complete union despite the low body weight. Continuous radiographi cmonitoring under immobilization revealed the full course of indirect bone healing, including bridging callus formation across both bones, trabecular reconstruction, and re-establishment of the medullary cavity during remodeling.

Figure 5. In a 5 month-old Toy Poodle treated with the 3D cast, active callus formation rapidly bridged the growth plate during the early healing phase. Two weeks after cast application, the bone diameter had increased to more than twice its original size, followed by gradual remodeling toward normal morphology. This markedly accelerated healing response, characterized by vigorous callus proliferation and early structural reconstruction, was defined in this study as “Super-Healing.”

Figure 6. In a 9 month-old Toy Poodle with a markedly displaced fracture, gradual realignment of the fracture fragments was observed under weight-bearing conditions during 3D cast fixation.

Ordinarily, allowing ambulation in such cases results in bending deformity at the fracture site due to axial loading; however, the 3D cast maintained a physiological stress distribution, leading to a self-correcting realignment of the fragments over time. This spontaneous alignment under functional loading, accompanied by abundant callus formation ensuring stability, was defined as “Slide-Healing.”

Figure 7. In a 9 year-old Toy Poodle with a severely comminuted radial–ulnar fracture, complete bone union was achieved despite marked displacement and fragmentation. This case demonstrates that 3D cast therapy can be applied safely even in complex fractures and elderly cases, indicating its broad clinical applicability beyond simple or non-displaced fractures.

Continuous radiographi cmonitoring of these representative cases enabled quantitative and objective visualization of the entire course of fracture healing. As a result, distinct healing patterns were identified, including marked callus proliferation with rapid remodeling in juvenile dogs (“Super-Healing”) and progressive self-correcting realignment of displaced fragments under functional loading (“Slide-Healing”).

These observations indicate that the 3D cast therapy serves as a novel treatment concept that integratively promotes both the biological and mechanical processes of bone repair.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that case-specific three-dimensional (3D) cast therapy effectively addresses radial–ulnar fractures in toy-breed dogs while minimizing activity restrictions. Sequential radiographs objectively visualized indirect bone healing and revealed two load-responsive phenomena: rapid, exuberant callus formation in juveniles (“Super-Healing”) and spontaneous realignment of displaced fragments under functional loading (“Slide-Healing”). These findings indicate that controlled axial loading with stable yet flexible immobilization can harness mechanobiological pathways to accelerate union and restore alignment.

Conventional osteosynthesis provides rigid fixation but is accompanied by well-documented complications, including stress shielding, marrow obstruction, and implant failure. Moreover, direct bone healing typically produces minimal callus and often relies on subjective radiographic assessment [

1,

2,

3,

7]. Traditional casting, although minimally invasive, often fails to provide sufficient stability in displaced fractures and is prone to deformity and disuse-related complications [

8]. In contrast, 3D cast therapy provides stable yet flexible fixation that transmits axial load during gait, thereby stimulating callus formation. This concept is supported by experimental evidence indicating that controlled mechanical loading during the reparative phase enhances bone regeneration [

9,

10,

11,

12,

16], consistent with Wolff’s law of functional adaptation [

13]. Moreover, recent mechanobiological studies have emphasized that interfragmentary strain and load-dependent mechanotransduction are key determinants of tissue differentiation during fracture healing [

15,

19].

The phenomena observed in this study highlight how controlled loading environments can elucidate biological repair mechanisms that have rarely been documented using conventional methods. Furthermore, even in extremely low-weight dogs with thin radial–ulnar cortices and marked displacement—cases that would conventionally require surgical fixation—successful alignment and complete union were achieved with 3D cast therapy (

Supplementary Figure S1). This case exemplifies how controlled functional loading can overcome mechanical limitations of thin bones and enable reliable healing without internal implants.

The robust callus response in juveniles (“Super-Healing”) aligns with the concept that young bone, with its heightened regenerative capacity, reacts strongly to mechanical stimuli [

17,

18].

Meanwhile, gradual realignment of displaced fragments under physiological loading (“Slide-Healing”) illustrates how functional weight-bearing can facilitate correction of malalignment through continuous, load-guided remodeling—a process rarely captured in traditional immobilization or surgical fixation.

These findings collectively illustrate how functional loading contributes to bone repair through mechanobiological adaptation.

Beyond mechanical adaptation, the 3D cast system provides a unique clinical model of physiological bone regeneration. Controlled functional loading allows the intrinsic healing potential of bone tissue to manifest without the biological disruption caused by surgical fixation. This approach mirrors key principles of regenerative medicine, emphasizing the stimulation of the body’s innate repair mechanisms rather than artificial replacement. The continuous radiographic observation of callus evolution under functional conditions demonstrates how appropriate mechanical cues can orchestrate cellular differentiation, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling in vivo. Thus, 3D cast therapy not only serves as a minimally invasive orthopedic treatment but also represents a translational model linking clinical orthopedics with regenerative biology.

Age-related differences in regenerative capacity and healing time were analyzed in detail in a separate large-scale study, which quantitatively supports the biological trends observed in this work. This complementary evidence strengthens the overall validity of the 3D cast therapy concept.

Even in adult dogs, satisfactory bone union can be achieved with 3D cast therapy. However, when presentation is delayed for several days after fracture, the fracture ends may begin to harden due to early callus formation, making manual reduction of alignment more difficult. In juvenile dogs, such displacement can often be corrected gradually through the Slide-Healing process under functional loading, but in adults, diminished regenerative capacity may result in residual curvature. Therefore, early presentation and initiation of treatment are crucial for achieving proper alignment and favorable cosmetic outcomes.

In contrast, in large-breed dogs, the structural limitations of the 3D cast make it difficult to achieve and maintain accurate alignment during the initial treatment stage. Therefore, surgical reduction should be performed first to restore proper alignment, and transition to 3D cast therapy once partial bone union has been established may be a more practical approach.

This staged strategy allows the precision of surgical fixation to be combined with the biological advantages of functional loading provided by the 3D cast, potentially offering a more physiological environment for bone repair.

Future perspectives of this work extend beyond fracture management and toward regenerative medicine. Radiographic visualization of bone healing has opened a new window into the behavior of bone marrow–derived stem cells during repair. The strong regenerative response observed in young dogs suggests that age-dependent variations in stem cell activity may underlie differences in healing capacity. Further studies combining imaging analysis with molecular and cellular investigations could clarify how mechanical stimulation interacts with stem cell–mediated osteogenesis, ultimately bridging clinical orthopedics and regenerative biology.

This therapy has thus far been primarily implemented at our facility, but future efforts should aim to expand its application through multicenter validation and dissemination. Establishing reproducibility across institutions will be essential for broader clinical adoption.

Overall, this study demonstrated that 3D cast therapy represents a minimally invasive and practical treatment option for managing radial–ulnar fractures, and introduced radiographic visualization of the bone healing process into clinical practice.

Future work should focus on standardizing objective parameters—such as callus thickness and bridging scores—based on these visualization data to improve inter-observer reproducibility and further consolidate the scientific foundation of this therapeutic approach.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that case-specific, two-phase three-dimensional (3D) cast therapy offers clear clinical advantages for managing radial–ulnar fractures in toy-breed dogs. By allowing controlled weight-bearing, it maintains stable immobilization while enhancing the case’s quality of life throughout the treatment period. Sequential radiographs enabled radiographic visualization of the entire bone healing process, providing an objective and reproducible means of evaluating fracture union. Beyond its clinical utility, this visualization-based approach provides an in vivo model for studying the biological mechanisms of bone regeneration and highlights the potential of mechanical stimulation as a driver of regenerative processes. Owing to its simplicity, safety, and reproducibility, 3D cast therapy has the potential to complement surgical fixation and—particularly for toy and small-breed dogs—may represent a new standard of care for the management of radial–ulnar fractures.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1. Successful healing of a displaced complete fracture in a low-weight toy breed using 3D cast therapy. A toy poodle (1.4 kg, 11 months old) presented with a completely displaced distal radial–ulnar fracture involving extremely thin bone cortices. Such fractures in low-weight toy breeds are typically considered surgical indications because of the narrow bone diameter, distal location, and risk of instability. Non-surgical management was performed using a patient-specific 3D-printed cast. Sequential radiographs demonstrate gradual correction of displacement, rapid callus formation, and complete bone union within 60 days. This case illustrates that 3D cast therapy can provide sufficient stability for fracture healing even in thin-boned, low-weight dogs, expanding treatment possibilities beyond conventional osteosynthesis. (A) Day 1 after injury: markedly displaced distal fracture in a thin-boned radius and ulna. (B) Day 34: abundant periosteal callus and early bridging under 3D cast treatment. (C) Day 48: continued consolidation of bridging callus. (D) Day 60: complete union with restoration of cortical continuity.

Author Contributions

Shigeo Ishijima performed all aspects of the study, including conceptualization, methodology, data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, because it was based on retrospective analysis of clinical case records.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all owners for the treatment of their animals.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the staff of Ishijima Animal Hospital for their assistance in data collection and case care.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang X, et al. An experimental study on stress-shielding effects of locked compression plates in fixing intact dog femur. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16:97. [CrossRef]

- Mori Y, et al. A review of the impacts of implant stiffness on fracture healing. J Funct Biomater. 2022;13:88. [CrossRef]

- Uhthoff HK, Poitras P, Backman DS. Internal plate fixation of fractures: Short history and recent developments. J Orthop Sci. 2006;11:118–26. [CrossRef]

- Harasen G. Radius and ulna fractures in dogs and cats: a review. Can Vet J. 2003;44:475–6.

- Marsell R, Einhorn TA. The biology of fracture healing. Injury. 2011;42:551–5. [CrossRef]

- Einhorn TA. The cell and molecular biology of fracture healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;355 Suppl:S7–21. [CrossRef]

- Pozzi A, Risselada M, Winter MD. Assessment of fracture healing after minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis or open reduction and internal fixation of coexisting radius and ulna fractures in dogs via ultrasonography and radiography. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012;241:744–53. [CrossRef]

- Keller MA, Montavon PM. Conservative fracture treatment using casts: Indications, principles of closed fracture reduction and stabilization, and cast materials. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2006;19:93–9. [CrossRef]

- Goodship AE, Kenwright J. The influence of induced micromovement upon the healing of experimental tibial fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:650–5. [CrossRef]

- Claes L, Heigele CMagnitudes of local stress and strain along bony surfaces predict the course and type of fracture healing. J Biomech. 1999;32:255–66. [CrossRef]

- Egger EL, et al. Effects of axial dynamization on bone healing. Vet Surg. 1993;22:241–8. [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan ME, Bronk JT, Chao EY, Kelly PJ. Experimental study of the effect of weight bearing on fracture healing in the canine tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;302:273–83. [CrossRef]

- Andrada E, Reinhardt L, Lucas K, Fischer MS. Three-dimensional inverse dynamics of the forelimb of Beagles at a walk and trot. Am J Vet Res. 2017;78:804–17. [CrossRef]

- Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–82. [CrossRef]

- Claes L, Recknagel S, Ignatius A. Fracture healing under healthy and inflammatory conditions. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:133–43. [CrossRef]

- Morgan EF, et al. Mechanobiology of bone healing. J Orthop Res. 2018;36:313–23. [CrossRef]

- Gerstenfeld LC, et al. Age-related changes in fracture healing. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17(Suppl 10):S21–9. [CrossRef]

- Bonnarens F, Einhorn TA. The role of mesenchymal stem cells in fracture healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2677–85. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, et al. Mechanobiology of indirect bone fracture healing under conditions of relative stability. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:942885. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).