1. Introduction

Emotion recognition is an important aspect of social cognition. Attributing affective states, such as emotions, represents one component of the broader ability to infer mental states to form a theory of mind (the so-called Theory of Mind, hereinafter TOM) (Premack & Woodruff, 1978). The process of such inference is often described as mentalizing (Frith, 1989). Studying TOM and its components is particularly important given their relevance to neurological and psychiatric conditions. Deficits in recognizing emotional states from facial expressions are observed, for example, in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders (Altschuler et al., 2018; Shamay-Tsoory et al., 2007). These impairments are also associated with structural and functional alterations in brain areas that form the functional neuroanatomical human brain system associated with TOM (Quidé, Wilhelmi, & Green, 2020; Vucurovic, Caillies, & Kaladjian, 2020). Therefore, investigating the psychological and neurophysiological basis of TOM is essential due to their potential value in diagnostic, developing rehabilitation methods tailored to specific facets of social cognition, and creating treatment protocols targeting precise neural correlates through neuromodulation. To conduct such research, appropriate instruments and methods are required, ideally adapted and validated for speakers of different languages.

The psychodiagnostics tool widely used in clinical practice and scientific research of the brain bases of affective mentalization is the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET). This test was proposed in 1997 (Simon Baron-Cohen et al., 1999), then modified and corrected in 2001 (Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Hill, Raste, & Plumb, 2001). The standard RMET consists of 36 tasks (stimuli) – photographs depicting eye region, expressing a certain emotion with gaze and facial expressions. The task is to choose the appropriate word that most accurately describes the emotion conveyed by the image. The control condition is the task of determining a person's gender from the same eye’s photographs. This test is a relevant, frequently used and discussed method (for example, (Pavlova & Sokolov, 2022)). RMET has been used to study collective intelligence (Woolley, Aggarwal, & Malone, 2015), physiological response to stress (Tollenaar & Overgaauw, 2020), cognitive aging processes (Castelli et al., 2010; Hartshorne & Germine, 2015) and sex differences (Greenberg et al., 2023) on healthy volunteers. The relevance of RMET is also confirmed by the number of translations and adaptations. Tests with the same target words and the same difficulty as the original version were developed for Asian faces (Adams et al., 2010), Korean faces (Koo et al., 2021), Black faces (Handley, Kubota, Li, & Cloutier, 2019), as well as a multiracial faces (Kim et al., 2024). The Russian-language adaptation of the RMET task was mentioned in earlier works (Rumyantseva, 2013; Sakhibalieva, Proshutinsky, Mershina, & Pechenkova, 2023), however, used stimuli, the procedure and results of their validation were not described. At the same time, fMRI studies using the Russian-language version of the RMET are rare and have an extremely small sample size (in the study (Sakhibalieva, Proshutinsky, Mershina, & Pechenkova, 2023) – 8 people).

In addition to neurophysiological research RMET has been widely used in clinical and psychodiagnostic studies (meta-analysis (Johnson, Kivity, Rosenstein, LeBreton, & Levy, 2022)) including diseases such as autism spectrum disorders (meta-analysis (Peñuelas-Calvo, Sareen, Sevilla-Llewellyn-Jones, & Fernández-Berrocal, 2019)), schizophrenia (meta-analysis (Deng et al., 2024)), clinical depression (Simon et al., 2019), borderline personality disorder (meta-analysis (Bora, 2021)), neurodegenerative diseases (meta-analysis (Stafford et al., 2023)), and eating disorders (meta-analysis (Preti, Siddi, Marzola, & Abbate Daga, 2022)). Neural mechanisms of the RMET-related emotion recognition process were also studied in relation to psychological traits, e.g., empathy and alexithymia (an inability to express, describe, or distinguish among one’s emotions (Nemiah, Freyberger, & Sifneos, 1976)). Previous studies have linked RMET performance to alexithymia scores (Oakley, Brewer, Bird, & Catmur, 2016; Rødgaard, Jensen, & Mottron, 2019), various metrics of empathy (Eddy & Hansen, 2020; Kittel, Olderbak, & Wilhelm, 2022; Valla et al., 2010) or both of them (Demers & Koven, 2015; Lee, Nam, & Hur, 2020; Lyvers, Lsdorf, Edwards, & Thorberg, 2017; Nam, Lee, Lee, & Hur, 2020; Vellante et al., 2013).

However, the version of the test presented by S. Baron-Cohen and colleagues (2001) has at least two limitations. First, the authors of the test did not know the real emotions experienced by people depicted in the photographs (the photographs were not prepared by the authors themselves but chosen from newspapers). Second, this version contains a relatively small number of conditions (36 images). High-quality scientific studies, including neuroimaging (for example, fMRI), often require a higher ratio of observations per participant. For instance, according to (Masharipov, Knyazeva, Korotkov, Cherednichenko, & Kireev, 2024), if an fMRI study aims to assess task-related functional connectivity changes, then, based on special simulation study calculations, RMET task requires at least 80 stimuli per experimental condition. Literature assessment shows that fMRI studies using RMET are characterized by a significant deviation from these requirements (there are significantly fewer stimuli) and therefore have low statistical power. This is a potential reason for the lack of reported experimental findings on changes in brain functional connectivity during RMET.

The aim of the current study was to develop and validate the Russian version of RMET ready to use in neuroimaging research. To overcome abovementioned methodological limitations the modified version of the test was also extended compared to the original version. We first prepared gaze images from a database of facial expressions and translated the verbal definitions of the emotions depicted by the actors. In pilot Study 1, we tested this material to assess how accurately emotions could be identified using the Russian descriptions and selected those items that showed an appropriate level of correspondence between the gaze descriptions and the images. Then, we validated the developed expanded version of the RMET formed from the items selected in Study 1 on a different sample of participants (Study 2). This was done by analyzing the relationship between accuracy on the modified RMET and the results of relevant psychodiagnostic questionnaires: the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-26), which measures alexithymia, and the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), which assesses various aspects of empathy.

2. Study 1

2.1. Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Participants

A total of 276 native Russian speakers who did not report any neurological disorders were recruited to complete a task on the Toloka crowdsourcing platform (toloka.ai). Using standard Toloka quality control parameters, 27 participants with low accuracy (less than 25% in the most recent 32 tasks) and 37 participants with unrealistically fast responses (less than 4 seconds per task in the most recent 36 tasks) were excluded during labeling and were not allowed to continue. Statistical analysis was conducted on the remaining 212 participants (123 females, 89 males; age range = 18–67 years; M = 37.5, SD = 10.3).

Before completing the task, participants were informed about the study’s objectives, voluntary nature, and anonymity. Continued participation—i.e., filling out and submitting a questionnaire without immediate payment—was taken as informed consent according to the information provided to respondents. Participants who completed labeling could receive $3.67 for all tasks ($0.19 for each labeled block), which substantially exceeded the average payment for similar tasks on the platform.

2.1.2. Materials

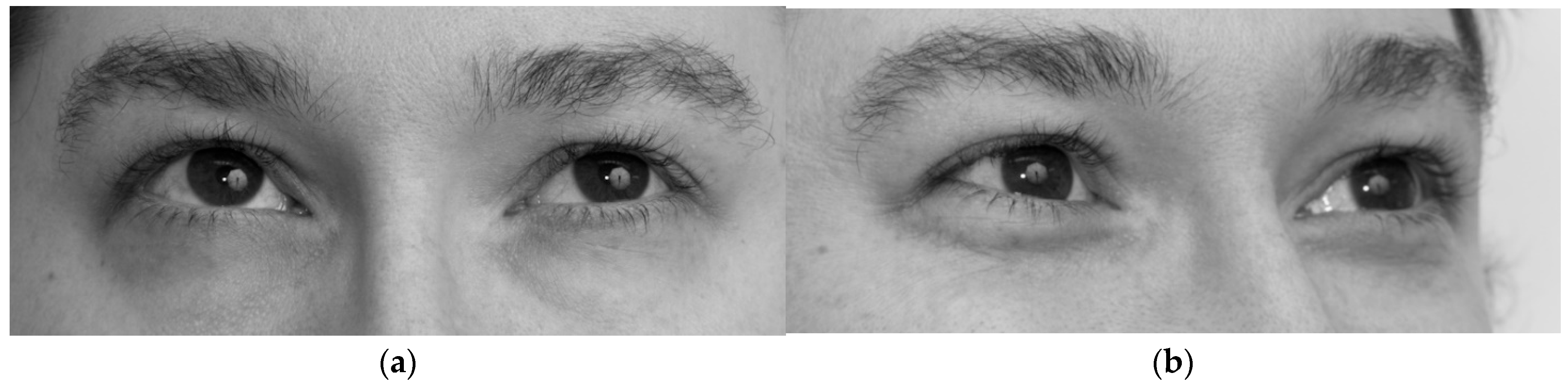

The photographs used for the test were sourced from a stimulus bank collected at McGill University for research on emotion recognition (Schmidtmann, Jennings, Sandra, Pollock, & Gold, 2020), notable for its wide range of emotional states. Two actors (one male, one female) portrayed target emotions, which were known in advance. The full set contained 93 emotions, each described by one adjective (e.g., “irritated” or “terrified”). Each emotion was presented in four versions: male or female face, and full-face or three-quarter view. Following the RMET approach, our test used only gaze regions—cropped, desaturated face images (

Figure 1). To create these stimuli, we repeated the image preparation step described earlier by for 36 images (Schmidtmann, Logan, Carbon, Loong, & Gold, 2020).

Each target emotion description was translated into Russian as a single adjective. Emotions that could not be adequately expressed in one word were excluded. The suitability of each adjective was checked using the Russian National Corpus (ruscorpora.ru; accessed 13 November 2023). Descriptions that never occurred in the corpus when referring to a gaze or eyes were excluded, as were low-frequency descriptors or those replaced with more frequent alternatives.

The final set included 82 gaze descriptions, with five repetitions (vstrevožennyj ‘worried/alarmed’, podavlennyj ‘depressed/dispirited’, dovolʹnyj ‘contented/satisfied’, podozrevajuščij ‘dubious/suspicious’ and nerešitelʹnyj ‘indecisive/tentative’), but the images and alternative options for repeated descriptions were not duplicated. Since our priority was to ensure correspondence between the description and the image—and the adequacy of Russian–English matches could not be pre-assessed—we retained repeated descriptions to identify consistently well-recognized emotions through later validation.

The best-known RMET version (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001) offers four response options, with distractors close in meaning to the target to test recognition of subtle differences of emotional facial expressions. In contrast, the authors of the original stimulus database (Schmidtmann, Jennings, et al., 2020) used fully randomized alternatives to evaluate correlations between emotion labels and images. Our aim was to create a ready-to-use item bank for studying mechanisms of reading emotions from the eyes; thus, alternatives in our test were fixed for each target emotion. We did not control the difficulty of differentiating the alternatives for two reasons: (1) our primary interest was in studying the recognition process itself rather than fine-grained distinctions; and (2) difficulty cannot be established without prior knowledge of how well Russian descriptions match the images. For each of the 82 target emotions, alternative options were randomly selected once and then fixed so that the same four options (one target, three distractors) appeared across all four gaze variants (male/female × full-face/three-quarter view), yielding 328 stimuli in total.

2.1.3. Procedure

Data labeling was conducted online and could be completed using either a personal computer or a mobile device. The 328 trials were organized into 19 blocks, each containing 18 unique combinations of gaze stimuli and response options in randomized order. Each block was presented in its entirety on a single page, with stimuli arranged in pairs in a vertical, scrollable layout. Participants could enlarge images and scroll through the block to make selections. A block could only be submitted once all trials within it had been completed. Upon completion, the next block was presented immediately, with no pause or inter-block interval.

Participants identified the emotion conveyed in each gaze by selecting one of four fixed response options, using any available input method (e.g., mouse, touchpad, or touchscreen). The pre-specified target emotion was considered the correct response. The task was self-paced, and both accuracy and response time were recorded.

2.2. Results

The average participant accuracy was 47.67%, and the average time to complete a task block was 183 seconds. On average, participants completed 10.39 blocks. For each task, an average of 120.46 responses (SD = 4.54) were collected.

For further validation, 144 tasks were selected that were labeled with an accuracy of at least 50% (a total of 145 such combinations were obtained, for the full list of tasks see

Table S1,

Figures S1-S144). Among the selected images, the number of females faces slightly exceeded the number of male faces—74 and 70, respectively. This distribution replicates the results reported in the validation of the image database (Schmidtmann, Jennings, et al., 2020). Emotions on female faces were identified equally well from both viewing angles (37 each), whereas in male images, the direct angle predominated (39 vs. 31). These images corresponded to 64 unique gaze descriptions (ranging from 1 to 5 images per description, with an average of 2.25). Only

dovolʹnyj “contented/satisfied” gaze corresponded to five tasks, as there were two distinct

dovolʹnyj gazes in the set.

Next, the second stage (Study 2) was conducted with two objectives. First, we aimed to replicate the accuracy results obtained in Study 1 using a new participant sample. Second, our goal was to validate the modified RMET by examining potential associations between its performance accuracy and psychometric measures. Based on previous research, we expected to observe a negative relationship with alexithymia scores and a positive relationship with empathy scores (Pavlova & Sokolov, 2022).

3. Study 2

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Participants

A total of 156 native Russian speakers who did not report any neurological disorders and had not participated in Study 1 were recruited to complete psychometric questionnaires and the RMET task on the Toloka crowdsourcing platform (toloka.ai). Using standard Toloka quality control parameters, 3 participants with low accuracy (less than 25% in the most recent 32 tasks) and 14 participants with unrealistically fast responses (less than 4 seconds per task in the most recent 36 tasks) were excluded during labeling and were not allowed to continue. An additional 30 participants were excluded for providing demographic information and completing questionnaires in under 5 minutes. Finally, 9 participants were excluded for repeated or aberrant answer patterns: 7 participants had ≥2 types of responses falling within the 2nd percentile for all participants in that response type, and 2 participants produced anomalously long series of identical answers.

As a result, statistical analysis was conducted on 108 participants (67 females, 41 males; M = 38.0, SD = 10.0). Before starting the task, participants were informed about the study’s objectives, voluntary nature, and anonymity. Continued participation—i.e., completing and submitting the questionnaire without immediate payment—was taken as informed consent according to the information provided. Participants were informed that the maximum reward for the paid portion of the task was $2.35 for approximately 45 minutes of work.

3.1.2. Materials

Two psychodiagnostic questionnaires were used in Study 2. The 26-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-26; (Taylor, Ryan, & Bagby, 1985)) is a clinical instrument designed to measure alexithymia – a construct characterized by difficulty in identifying and describing one's own feelings. It is also sometimes associated with low emotional sensitivity to other people and low emotional involvement in everyday life. The 28-item Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; (Davis, 1980)) assesses both emotional and cognitive components of empathy and is based on a multidimensional approach. The author conceptualized empathy not as a single unipolar construct (i.e. either emotional or cognitive), but as a set of related constructs represented by four subscales: Fantasy, which reflects the tendency to imaginatively transfer oneself into the feelings and actions of fictional characters in books, films, plays, etc.; Perspective Taking, which evaluates the tendency to perceive, understand, consider, and take into account another person’s point of view or experience; Empathic Concern, which evaluates feelings directed towards others (sympathy, compassion or a desire to help etc.); Personal Distress, which measures self-oriented feelings of anxiety and discomfort that arise in tense interpersonal interactions or when observing others’ suffering. Both questionnaires had been previously adapted into Russian, so we used the 26-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale as adapted by Eresko and colleagues (Eresko et al., 2005) and the 28-item Interpersonal Reactivity Index as adapted by Karyagina and colleagues (Karyagina, Budagovskaya, & Dubrovskaya, 2013; Karyagina & Kukhtova, 2016).

The RMET task consisted of 144 stimuli that had been recognized with at least 50% accuracy in Study 1 (for full list of tasks see Supplementary materials).

3.1.3. Procedure

After providing the demographic information and before performing the RMET task, participants completed two psychodiagnostic questionnaires (TAS-26 and IRI). The following procedure was identical to that used in Study 1.

3.1.4. Statistical Analysis

The aim of this analysis was to examine whether RMET performance accuracy is associated with individual differences in psychometric measures of empathy and alexithymia.

We first checked statistical assumptions and computed Pearson correlations between RMET accuracy and the psychometric variables (TAS-26 score and four IRI subscale scores: Fantasy, Perspective Taking, Empathic Concern, and Personal Distress).

Since several scales were intercorrelated, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis to extract independent (orthogonal) factors. This step reduces redundancy between variables and makes it possible to estimate each factor’s contribution to RMET performance without confounding effects from the others. All scales were mean-centered prior to the analysis.

The adequacy of the data for factor analysis was assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) criterion, which compares correlations between variables to partial correlations (i.e., correlations after accounting for the influence of other variables). Higher KMO values indicate that a variable contributes more meaningfully to the factor structure.

The extracted factors were then entered as predictors in a hierarchical Bayesian logistic regression model of RMET trial accuracy. The model included random effects for participants and tasks, and noninformative priors were used. This approach allowed us to assess how each factor influences the probability of a correct or incorrect response while accounting for individual and item-level variability.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. RMET

The average participant accuracy was 71% and the average time to complete a task block was 210 seconds. On average, participants completed 7.37 blocks. Emotion recognition accuracy in Study 2 showed a strong positive correlation with that in Study 1 (rₚ = 0.90), indicating that tasks rated as relatively easy or difficult in the first study tended to elicit similarly high or low accuracy in the second.

3.2.2. Associations Between Psychometric Measures and RMET Accuracy

For each participant, scores were obtained for the TAS-26 and the four IRI subscales (Fantasy, Perspective Taking, Empathic Concern, Personal Distress) (

Table 1).

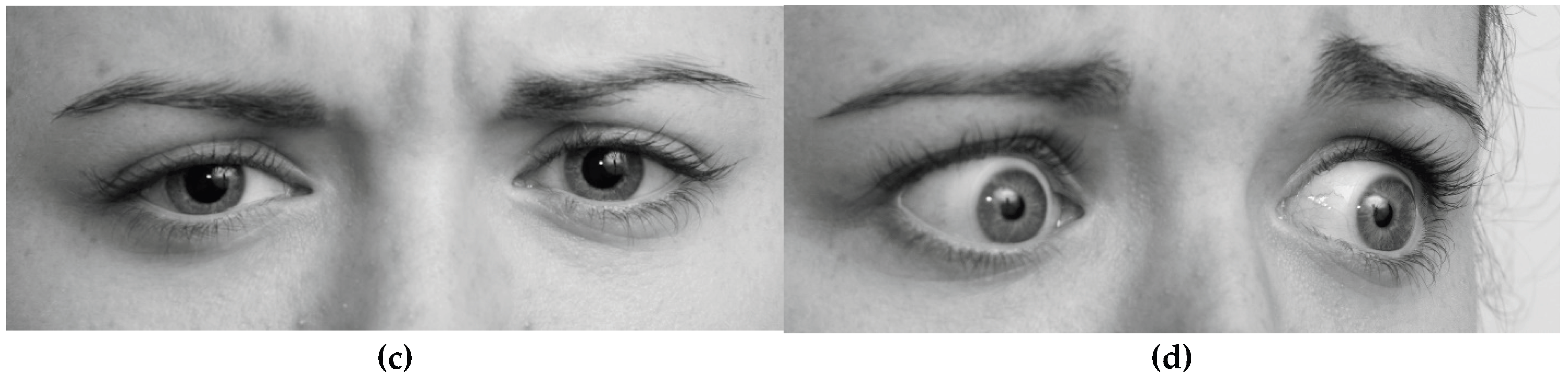

Pearson correlation analysis showed that TAS-26 scores correlated negatively with Perspective Taking and Fantasy subscales and positively with the Personal Distress scale (p < 0.05,

Figure 2).

Factor analysis reduced the five original variables to three orthogonal factors which consist of: Factor 1 – high TAS-26 and Personal Distress scores, Factor 2 – high Empathic Concern and Perspective Taking scores, Factor 3 – high Fantasy scores and low TAS-26 scores. The KMO values were: TAS-26 = 0.58; Empathic Concern = 0.64; Personal Distress = 0.46; Perspective Taking = 0.71; Fantasy = 0.60 (

Table 2).

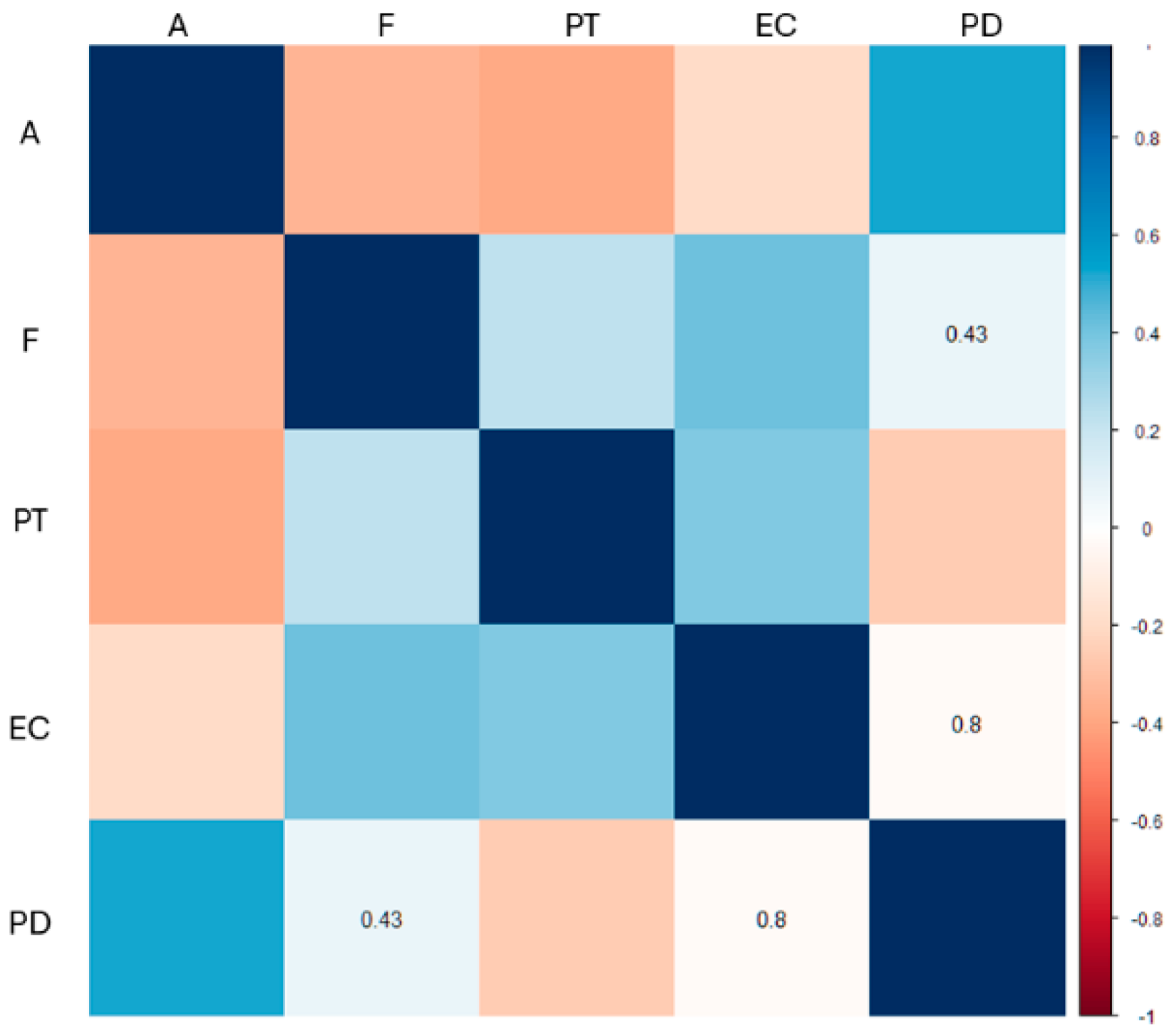

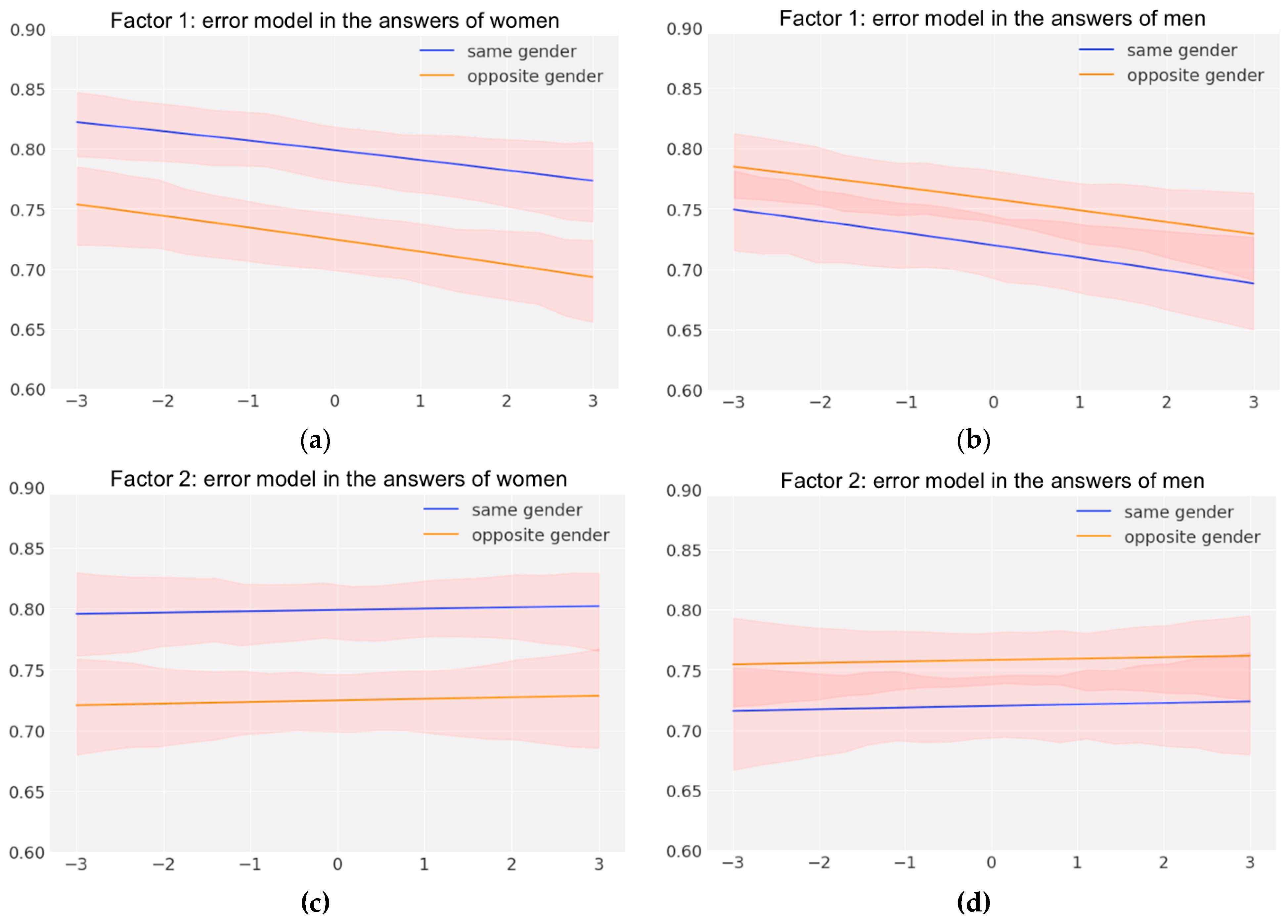

The hierarchical Bayesian logistic regression model indicated that higher scores on Factor 1 were associated with an increased probability of error in RMET performance, whereas low values on both TAS-26 and Personal Distress corresponded to higher accuracy in both male and female participants (

Table 3,

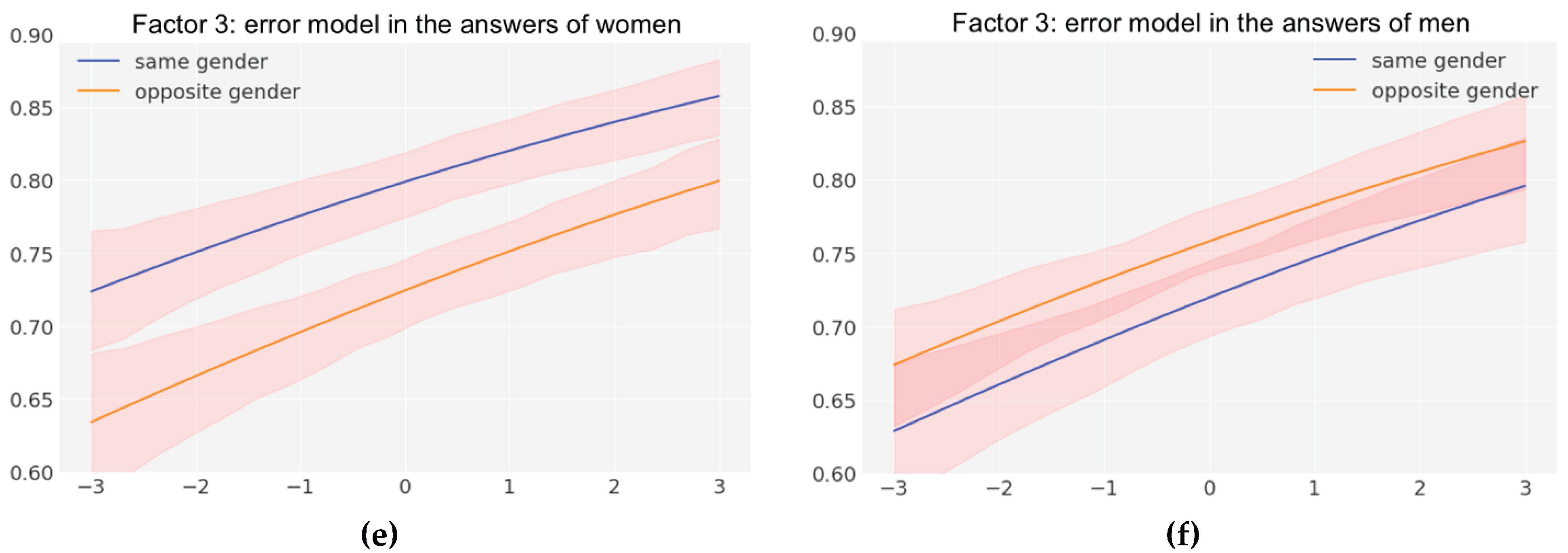

Figure 3a, 3b). In contrast, higher scores on Factor 3, reflecting high Fantasy and low TAS-26 scores, were associated with better accuracy (

Figure 3e, 3f). Factor 2 did not show a notable effect on overall accuracy; however, there was an indication that participants were more successful in recognizing emotions in female faces (

Figure 3c, 3d).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we developed and validated a modified and extended Russian version of the RMET ready to use in psychological and neurophysiological research (see Supplementary materials). The performance accuracy of the modified test is comparable to that of the original RMET and its earlier translations and adaptations. The validity of the test was supported by demonstrating significant relationships between performance accuracy and relevant psychological constructs, such as alexithymia and empathy. Specifically, we confirmed the hypotheses that RMET accuracy is negatively associated with alexithymia scores in TAS-26 and positively associated with the Fantasy subscale of the IRI. In addition, we showed a negative association between RMET accuracy and the Personal Distress subscale of the IRI.

The final stimulus set comprised 144 images, each with a target emotion correctly identified by at least 50% of participants. In a separate validation sample, the mean accuracy for these 144 stimuli was 71%, and a strong correlation was observed between the results in both samples. These findings are consistent with the procedure and outcomes of the original RMET development, in which stimuli were tested by eight raters until at least five raters chose the target word correctly, resulting in an overall accuracy of 78% in a sample of 103 participants (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001). The accuracy of our modified Russian RMET is also comparable to those reported for the Asian RMET (73%; (Adams et al., 2010)), the Korean RMET (71%; (Koo et al., 2021)), the Black RMET (69% for Black participants and 76% for White participants; (Handley et al., 2019)), and the multiracial RMET (63.4%; (Kim et al., 2024)). Moreover, the obtained mean accuracy in our study is close to a midway between perfect and chance performance, which is desirable test performance from a psychometric perspective (Lord & Novick, 2008; Wilmer et al., 2012). For a four-alternative forced-choice format like RMET, this midpoint is 62.5%. We also observed that emotions expressed on female faces were recognized more accurately, a result consistent with prior validation of the stimulus database (Schmidtmann, Jennings, et al., 2020). Overall, the high and stable accuracy rates, comparable to those reported in previous literature, indicate a high degree of correspondence between the selected images and their Russian-language descriptors.

The stimulus set was further validated by examining associations between performance accuracy and psychometric measures, namely TAS-26 scores and two IRI subscales (Personal Distress and Fantasy). We can draw several important conclusions from these results.

Namely, the probability of an error increased with higher TAS-26 scores and decreased with lower scores for both men and women. This finding aligns with previous reports of a negative association between RMET performance and alexithymia severity (Demers & Koven, 2015; Lee et al., 2020; Lyvers et al., 2017; Oakley et al., 2016; Rødgaard et al., 2019; Vellante et al., 2013)and supports evidence that this relationship holds for both sexes, instead of being observed in men only (Vellante et al., 2013). Alexithymia—characterized by inability to express, describe, or distinguish among one’s own emotions—has been suggested to impair recognition of emotions in others (Brewer, Cook, Cardi, Treasure, & Bird, 2015). Given its strong association with RMET performance, some authors have questioned whether the RMET primarily measures emotion recognition rather than TOM. On the one hand, alexithymia, but not autism spectrum disorder (ASD), significantly influenced RMET scores without affecting performance on the Movie for the Assessment of Social Cognition (MASC), an alternative TOM measure (Oakley et al., 2016). Independent contribution was interpreted as evidence that the RMET assesses lower-level emotion recognition rather than higher-level TOM processes. On the other hand, other work has found associations between alexithymia and TOM within the ASD group (Rødgaard et al., 2019). Importantly, the RMET’s creators have stated that it is designed to assess both affective TOM and emotion recognition (S. Baron-Cohen et al., 2015; Vellante et al., 2013). Thus, difficulties in interpreting one’s own emotions, as seen in alexithymia, could hinder recognition of others’ emotions in the RMET.

We also found that higher Personal Distress scores and lower Fantasy scores predicted reduced RMET accuracy in both men and women. High Personal Distress scores reflect greater negative emotionality in the presence of others’ distress, whereas the Fantasy subscale measures the tendency to imagine oneself in fictional scenarios. Our findings are in line with the suggestion that Fantasy scores may specifically predict RMET performance (Eddy & Hansen, 2020). Nevertheless, prior studies have reported mixed evidence regarding which IRI subscales are associated with RMET scores. For example, in one study, TOM as measured by RMET fully mediated the relationship between Perspective Taking IRI subscale assessing the tendency to adopt other people’s points of view and hostile attribution bias (the tendency to interpret the intentions of others as hostile despite the lack of sufficient supporting information in certain situations) (Koo et al., 2022). Conversely, in another study, neither Fantasy nor Perspective Taking was correlated with RMET performance in Korean population (Lee et al., 2020). Other research has reported associations between personality traits themselves. For instance, overall TAS-20 scores have been negatively associated with both RMET accuracy and Empathic Concern subscale of the IRI scores measuring feelings of warmth and consideration towards others (Lyvers et al., 2017). In our sample, alexithymia scores negatively correlated with Perspective Taking and Fantasy, and positively with Personal Distress, a pattern consistent with previous findings (Nam et al., 2020).

In summary, performance accuracy in the modified Russian RMET is linked to the same key constructs—alexithymia and empathy—as the original RMET and its adaptations, providing further evidence for the validity of the test.

5. Conclusions

We developed and validated an open-access Russian-language adaptation of the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET), designed for immediate use in psychological and neurophysiological research. To address methodological constraints in neuroimaging studies, the test was expanded to 144 stimuli, increasing its statistical power compared to the original version. Results from two studies confirmed its construct validity and demonstrated its suitability for investigating emotion recognition processes in Russian-speaking populations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: The list of tasks for the expanded Russian-language adaptation of the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test; Figures S1-S144: pictures of gazes cropped from images in the stimulus set collected at McGill University (Schmidtmann, Jennings, et al., 2020).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K., D.C., A.K., M.Z., K.B., I.K., A.M., and R.M.; investigation, K.B.; formal analysis, K.B. and I.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.B. and M.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.Z., N.M., and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation (Grant No. 23–18-00521).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the N.P. Bechtereva Institute of the Human Brain of the Russian Academy of Sciences (protocol №7 , date of approval 26.10.2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams, R.B.; Rule, N.O.; Franklin, R.G.; Wang, E.; Stevenson, M.T.; Yoshikawa, S.; Nomura, M.; Sato, W.; Kveraga, K.; Ambady, N. Cross-cultural Reading the Mind in the Eyes: An fMRI Investigation. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2010, 22, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschuler, M.; Sideridis, G.; Kala, S.; Warshawsky, M.; Gilbert, R.; Carroll, D.; Burger-Caplan, R.; Faja, S. Measuring Individual Differences in Cognitive, Affective, and Spontaneous Theory of Mind Among School-Aged Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 3945–3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Bowen, D.C.; Holt, R.J.; Allison, C.; Auyeung, B.; Lombardo, M.V.; Smith, P.; Lai, M.-C. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test: Complete Absence of Typical Sex Difference in ~400 Men and Women with Autism. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0136521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Ring, H.A.; Wheelwright, S.; Bullmore, E.T.; Brammer, M.J.; Simmons, A.; Williams, S.C.R. Social intelligence in the normal and autistic brain: an fMRI study. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999, 11, 1891–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S.; Hill, J.; Raste, Y.; Plumb, I. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test Revised Version: A Study with Normal Adults, and Adults with Asperger Syndrome or High-functioning Autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2001, 42, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bora, E. A meta-analysis of theory of mind and ‘mentalization’ in borderline personality disorder: a true neuro-social-cognitive or meta-social-cognitive impairment? Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 2541–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, R.; Cook, R.; Cardi, V.; Treasure, J.; Bird, G. Emotion recognition deficits in eating disorders are explained by co-occurring alexithymia. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2015, 2, 140382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, I.; Baglio, F.; Blasi, V.; Alberoni, M.; Falini, A.; Liverta-Sempio, O.; Nemni, R.; Marchetti, A. Effects of aging on mindreading ability through the eyes: An fMRI study. Neuropsychologia 2010, 48, 2586–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. Retrieved from https://www.uv.es/friasnav/Davis_1980.pdf.

- Demers, L.A.; Koven, N.S. The Relation of Alexithymic Traits to Affective Theory of Mind. Am. J. Psychol. 2015, 128, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Bueber, M.A.; Cao, Y.; Tang, J.; Bai, X.; Cho, Y.; Lee, J.; Lin, Z.; Yang, Q.; Keshavan, M.S.; et al. Assessing social cognition in patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls using the reading the mind in the eyes test (RMET): a systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol. Med. 2024, 54, 847–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, C.M.; Hansen, P.C. Predictors of performance on the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0235529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eresko, D. B., Isurina, G. L., Kaidanovskaya, E. V., Karvasarsky, B. D., Karpova, E. B., Smirnova, T. G., & Shifrin, V. B. (2005). Aleksitimiya i metody ee opredeleniya pri pogranichnykh psikhosomaticheskikh rasstroystvakh [Alexithymia and its assessment methods in borderline psychosomatic disorders]. [in Russian].

- Frith, U. Autism and “Theory of Mind.”. Diagnosis and Treatment of Autism 1989, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, D.M.; Warrier, V.; Abu-Akel, A.; Allison, C.; Gajos, K.Z.; Reinecke, K.; … Baron-Cohen, S. Sex and age differences in “theory of mind” across 57 countries using the English version of the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2023, 120, e2022385119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handley, G.; Kubota, J.T.; Li, T.; Cloutier, J. Black “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” task: The development of a task assessing mentalizing from black faces. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0221867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartshorne, J.K.; Germine, L.T. When Does Cognitive Functioning Peak? The Asynchronous Rise and Fall of Different Cognitive Abilities Across the Life Span. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 26, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, B.N.; Kivity, Y.; Rosenstein, L.K.; LeBreton, J.M.; Levy, K.N. The association between mentalizing and psychopathology: A meta-analysis of the reading the mind in the eyes task across psychiatric disorders. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pr. 2022, 29, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karyagina, T.D.; Budagovskaya, N.A.; Dubrovskaya, S.V. Adaptatsiya mnogofaktornogo oprosnika empatii M. Devisa [Adaptation of the multifactor empathy questionnaire by M. Davis]. Konsultativnaya psikhologiya i psikhoterapiya [Counseling Psychology and Psychotherapy] 2013, 21, 202–227. [Google Scholar]

- Karyagina, T.D.; Kukhtova, N.V. (2016). Test empatii M. Devisa: soderzhatel’naya validnost’ i adaptatsiya v mezhkul’turnom kontekste [The M. Davis empathy test: Content validity and adaptation in an intercultural context]. [in Russian].

- Kim, H.A.; Kaduthodil, J.; Strong, R.W.; Germine, L.T.; Cohan, S.; Wilmer, J.B. Multiracial Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (MRMET): An inclusive version of an influential measure. Behav. Res. Methods 2024, 56, 5900–5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittel, A.F.D.; Olderbak, S.; Wilhelm, O. Sty in the Mind’s Eye: A Meta-Analytic Investigation of the Nomological Network and Internal Consistency of the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test. Assessment 2021, 29, 872–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, S.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Han, J.H.; Seo, E.; Park, H.Y.; Bang, M.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, E.; An, S.K. “Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test”: Translated and Korean Versions. Psychiatry Investig. 2021, 18, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, S.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Seo, E.; Park, H.Y.; Min, J.E.; Bang, M.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, E.; An, S.K. Relationship of neurocognitive ability, perspective taking, and psychoticism with hostile attribution bias in non-clinical participants: Theory of mind as a mediator. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 863763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-R.; Nam, G.; Hur, J.-W. Development and validation of the Korean version of the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0238309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozeboom, W.W.; Lord, F.M.; Novick, M.R.; Birnbaum, A. Statistical Theories of Mental Test Scores. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1969, 6, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyvers, M.; Kohlsdorf, S.M.; Edwards, M.S.; Thorberg, F.A. Alexithymia and Mood: Recognition of Emotion in Self and Others. Am. J. Psychol. 2017, 130, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masharipov, R.; Knyazeva, I.; Korotkov, A.; Cherednichenko, D.; Kireev, M. Comparison of whole-brain task-modulated functional connectivity methods for fMRI task connectomics. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, G.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.-H.; Hur, J.-W. Disguised Emotion in Alexithymia: Subjective Difficulties in Emotion Processing and Increased Empathic Distress. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemiah, J.; Freyberger, H.; Sifneos, P. (1976). Alexithymia: A view of the psychosomatic process. In O. W. Hill (Ed.), Modern trends in psychosomatic medicine (pp. 430–439). Retrieved from https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1571417124951568384.

- Oakley, B.F.M.; Brewer, R.; Bird, G.; Catmur, C. Theory of mind is not theory of emotion: A cautionary note on the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2016, 125, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlova, M.A.; Sokolov, A.A. Reading language of the eyes. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 140, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñuelas-Calvo, I.; Sareen, A.; Sevilla-Llewellyn-Jones, J.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test in Autism-Spectrum Disorders Comparison with Healthy Controls: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 49, 1048–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premack, D.; Woodruff, G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behav. Brain Sci. 1978, 1, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preti, A.; Siddi, S.; Marzola, E.; Daga, G.A. Affective cognition in eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the performance on the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2022, 27, 2291–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quidé, Y.; Wilhelmi, C.; Green, M.J. Structural brain morphometry associated with theory of mind in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. PsyCh J. 2019, 9, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rødgaard, E.-M.; Jensen, K.; Mottron, L. An opposite pattern of cognitive performance in autistic individuals with and without alexithymia. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2019, 128, 735–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumyantseva, E.E. (2013). Metodika otsenki psikhicheskogo sostoyaniya drugogo po vyrazheniyu glaz [Method for assessing another person's mental state by the expression of the eyes]. Psikhiatriya [Psychiatry] 2013, 3, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sakhibalieva, A.; Proshutinsky, E.; Mershina, E.; Pechenkova, E. (2023, December 1–3). Psikhologiya poznaniya [Psychology of cognition]. In Psikhologiya poznaniya [Psychology of cognition], Yaroslavl State University named after P. G. Demidov, Yaroslavl, Russia. OOO “Filigran’”. [in Russian].

- Schmidtmann, G.; Jennings, B.J.; Sandra, D.A.; Pollock, J.; Gold, I. The McGill Face Database: Validation and Insights into the Recognition of Facial Expressions of Complex Mental States. Perception 2020, 49, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidtmann, G.; Logan, A.J.; Carbon, C.-C.; Loong, J.T.; Gold, I. In the Blink of an Eye: Reading Mental States From Briefly Presented Eye Regions. I-Perception 2020, 11, 2041669520961116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamay-Tsoory, S.G.; Shur, S.; Barcai-Goodman, L.; Medlovich, S.; Harari, H.; Levkovitz, Y. Dissociation of cognitive from affective components of theory of mind in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007, 149, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Németh, N.; Gálber, M.; Lakner, E.; Csernela, E.; Tényi, T.; Czéh, B. Childhood Adversity Impairs Theory of Mind Abilities in Adult Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stafford, O.; Gleeson, C.; Egan, C.; Tunney, C.; Rooney, B.; O’keeffe, F.; McDermott, G.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Burke, T. A 20-Year Systematic Review of the ‘Reading the Mind in the Eyes’ Test across Neurodegenerative Conditions. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.J.; Ryan, D.; Bagby, M. Toward the Development of a New Self-Report Alexithymia Scale. Psychother. Psychosom. 1985, 44, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollenaar, M.S.; Overgaauw, S. Empathy and mentalizing abilities in relation to psychosocial stress in healthy adult men and women. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valla, J.M.; Ganzel, B.L.; Yoder, K.J.; Chen, G.M.; Lyman, L.T.; Sidari, A.P.; Keller, A.E.; Maendel, J.W.; Perlman, J.E.; Wong, S.K.; et al. More than maths and mindreading: Sex differences in empathizing/systemizing covariance. Autism Res. 2010, 3, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellante, M.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Melis, M.; Marrone, M.; Petretto, D.R.; Masala, C.; Preti, A. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” test: Systematic review of psychometric properties and a validation study in Italy. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry 2013, 18, 326–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vucurovic, K.; Caillies, S.; Kaladjian, A. Neural correlates of theory of mind and empathy in schizophrenia: An activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 120, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmer, J.B.; Germine, L.; Chabris, C.F.; Chatterjee, G.; Gerbasi, M.; Nakayama, K. Capturing specific abilities as a window into human individuality: The example of face recognition. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2012, 29, 360–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolley, A.W.; Aggarwal, I.; Malone, T.W. Collective Intelligence and Group Performance. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 24, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).